- Understanding Poverty

- Competitiveness

Tourism and Competitiveness

- Publications

The tourism sector provides opportunities for developing countries to create productive and inclusive jobs, grow innovative firms, finance the conservation of natural and cultural assets, and increase economic empowerment, especially for women, who comprise the majority of the tourism sector’s workforce. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was the world’s largest service sector—providing one in ten jobs worldwide, almost seven percent of all international trade and 25 percent of the world’s service exports —a critical foreign exchange generator. In 2019 the sector was valued at more than US$9 trillion and accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP.

Tourism offers opportunities for economic diversification and market-creation. When effectively managed, its deep local value chains can expand demand for existing and new products and services that directly and positively impact the poor and rural/isolated communities. The sector can also be a force for biodiversity conservation, heritage protection, and climate-friendly livelihoods, making up a key pillar of the blue/green economy. This potential is also associated with social and environmental risks, which need to be managed and mitigated to maximize the sector’s net-positive benefits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for tourism service providers, with a loss of 20 percent of all tourism jobs (62 million), and US$1.3 trillion in export revenue, leading to a reduction of 50 percent of its contribution to GDP in 2020 alone. The collapse of demand has severely impacted the livelihoods of tourism-dependent communities, small businesses and women-run enterprises. It has also reduced government tax revenues and constrained the availability of resources for destination management and site conservation.

Naturalist local guide with group of tourist in Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve Ecuador. Photo: Ammit Jack/Shutterstock

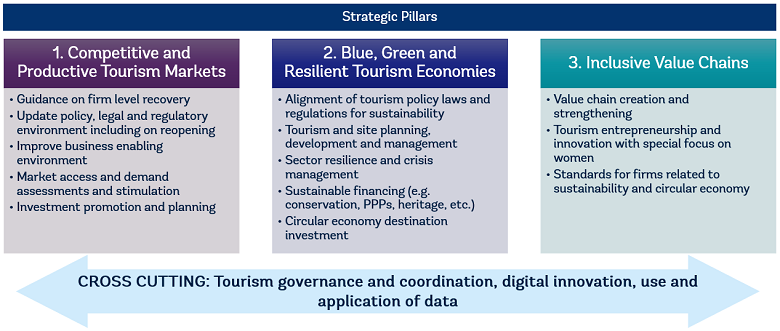

Tourism and Competitiveness Strategic Pillars

Our solutions are integrated across the following areas:

- Competitive and Productive Tourism Markets. We work with government and private sector stakeholders to foster competitive tourism markets that create productive jobs, improve visitor expenditure and impact, and are supportive of high-growth, innovative firms. To do so we offer guidance on firm and destination level recovery, policy and regulatory reforms, demand diversification, investment promotion and market access.

- Blue, Green and Resilient Tourism Economies. We support economic diversification to sustain natural capital and tourism assets, prepare for external and climate-related shocks, and be sustainably managed through strong policy, coordination, and governance improvements. To do so we offer support to align the tourism enabling and policy environment towards sustainability, while improving tourism destination and site planning, development, and management. We work with governments to enhance the sector’s resilience and to foster the development of innovative sustainable financing instruments.

- Inclusive Value Chains. We work with client governments and intermediaries to support Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs), and strengthen value chains that provide equitable livelihoods for communities, women, youth, minorities, and local businesses.

The successful design and implementation of reforms in the tourism space requires the combined effort of diverse line ministries and agencies, and an understanding of the impact of digital technologies in the industry. Accordingly, our teams support cross-cutting issues of tourism governance and coordination, digital innovation and the use and application of data throughout the three focus areas of work.

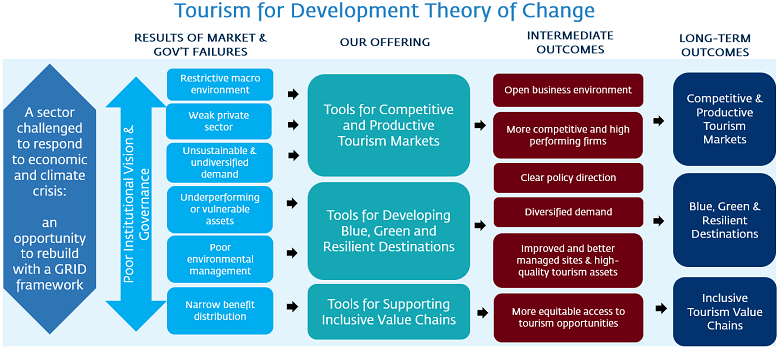

Tourism and Competitiveness Theory of Change

Examples of our projects:

- In Indonesia , a US$955m loan is supporting the Government’s Integrated Infrastructure Development for National Tourism Strategic Areas Project. This project is designed to improve the quality of, and access to, tourism-relevant basic infrastructure and services, strengthen local economy linkages to tourism, and attract private investment in selected tourism destinations. In its initial phases, the project has supported detailed market and demand analyses needed to justify significant public investment, mobilized integrated tourism destination masterplans for each new destination and established essential coordination mechanisms at the national level and at all seventeen of the Project’s participating districts and cities.

- In Madagascar , a series of projects totaling US$450m in lending and IFC Technical Assistance have contributed to the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by enhancing access to enabling infrastructure and services in target regions. Activities under the project focused on providing support to SMEs, capacity building to institutions, and promoting investment and enabling environment reforms. They resulted in the creation of more than 10,000 jobs and the registration of more than 30,000 businesses. As a result of COVID-19, the project provided emergency support both to government institutions (i.e., Ministry of Tourism) and other organizations such as the National Tourism Promotion Board to plan, strategize and implement initiatives to address effects of the pandemic and support the sector’s gradual relaunch, as well as to directly support tourism companies and workers groups most affected by the crisis.

- In Sierra Leone , an Economic Diversification Project has a strong focus on sustainable tourism development. The project is contributing significantly to the COVID-19 recovery, with its focus on the creation of six new tourism destinations, attracting new private investment, and building the capacity of government ministries to successfully manage and market their tourism assets. This project aims to contribute to the development of more circular economy tourism business models, and support the growth of women- run tourism businesses.

- Through the Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness: Tourism Response, Recovery and Resilience to the COVID-19 Crisis initiative and the Tourism for Development Learning Series , we held webinars, published insights and guidance notes as well as formed new partnerships with Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, United Nations Environment Program, United Nations World Tourism Organization, and World Travel and Tourism Council to exchange knowledge on managing tourism throughout the pandemic, planning for recovery and building back better. The initiative’s key Policy Note has been downloaded more than 20,000 times and has been used to inform recovery initiatives in over 30 countries across 6 regions.

- The Global Aviation Dashboard is a platform that visualizes real-time changes in global flight movements, allowing users to generate 2D & 3D visualizations, charts, graphs, and tables; and ranking animations for: flight volume, seat volume, and available seat kilometers. Data is available for domestic, intra-regional, and inter-regional routes across all regions, countries, airports, and airlines on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis from January 2020 until today. The dashboard has been used to track the status and recovery of global travel and inform policy and operational actions.

Traditional Samburu women in Kenya. Photo: hecke61/Shutterstock.

Featured Data

We-Fi WeTour Women in Tourism Enterprise Surveys (2019)

- Sierra Leone | Ghana

Featured Reports

- Destination Management Handbook: A Guide to the Planning and Implementation of Destination Management (2023)

- Blue Tourism in Islands and Small Tourism-Dependent Coastal States : Tools and Recovery Strategies (2022)

- Resilient Tourism: Competitiveness in the Face of Disasters (2020)

- Tourism and the Sharing Economy: Policy and Potential of Sustainable Peer-to-Peer Accommodation (2018)

- Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

- The Voice of Travelers: Leveraging User-Generated Content for Tourism Development (2018)

- Women and Tourism: Designing for Inclusion (2017)

- Twenty Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development (2017)

- An introduction to tourism concessioning:14 characteristics of successful programs. The World Bank, 2016)

- Getting financed: 9 tips for community joint ventures in tourism . World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and World Bank, (2015)

- Global investment promotion best practices: Winning tourism investment” Investment Climate (2013)

Country-Specific

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia: Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- Demand Analysis for Tourism in African Local Communities (2018)

- Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods . Africa Development Forum (2014)

COVID-19 Response

- Expecting the Unexpected : Tools and Policy Considerations to Support the Recovery and Resilience of the Tourism Sector (2022)

- Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness. Tourism response, recovery and resilience to the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- WBG support for tourism clients and destinations during the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- Tourism for Development: Tourism Diagnostic Toolkit (2019)

- Tourism Theory of Change (2018)

Country -Specific

- COVID Impact Mitigation Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Preparedness for Reopening Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Study (Fiji) (2020) with IFC

Featured Blogs

- Fiona Stewart, Samantha Power & Shaun Mann , Harnessing the power of capital markets to conserve and restore global biodiversity through “Natural Asset Companies” | October 12 th 2021

- Mari Elka Pangestu , Tourism in the post-COVID world: Three steps to build better forward | April 30 th 2021

- Hartwig Schafer , Regional collaboration can help South Asian nations rebuild and strengthen tourism industry | July 23 rd 2020

- Caroline Freund , We can’t travel, but we can take measures to preserve jobs in the tourism industry | March 20 th 2020

Featured Webinars

- Destination Management for Resilient Growth . This webinar looks at emerging destinations at the local level to examine the opportunities, examples, and best tools available. Destination Management Handbook

- Launch of the Future of Pacific Tourism. This webinar goes through the results of the new Future of Pacific Tourism report. It was launched by FCI Regional and Global Managers with Discussants from the Asian Development Bank and Intrepid Group.

- Circular Economy and Tourism . This webinar discusses how new and circular business models are needed to change the way tourism operates and enable businesses and destinations to be sustainable.

- Closing the Gap: Gender in Projects and Analytics . The purpose of this webinar is to raise awareness on integrating gender considerations into projects and provide guidelines for future project design in various sectoral areas.

- WTO Tourism Resilience: Building forward Better. High-level panelists from Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Jordan and Kenya discuss how donors, governments and the private sector can work together most effectively to rebuild the tourism industry and improve its resilience for the future.

- Tourism Watch

- [email protected]

Launch of Blue Tourism Resource Portal

From India to the world: Unleashing the potential of India’s tourists

Boosted by rising economic prosperity and a fast-growing economy, India is set to be an important global source market for leisure travel. India is now the fifth-largest economy, and its population has surpassed China’s to become the largest in the world, at over 1.4 billion people. 1 World Bank national accounts data, GDP (current US$) India, accessed September 2023; World population prospects 2022 , United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2022. And the population is young—the median age is 27.6, more than ten years younger than that of most major economies. 2 World population prospects 2022 . What's more, consumption of goods and services, including leisure and recreation, is forecast to double by 2030. 3 “India’s impending economic boom,” Morgan Stanley, November 8, 2022. Adding a strong postpandemic travel recovery, and a growing appetite for international travel, these factors point to India’s significant potential for outbound tourism.

India is now the fifth-largest economy, and its population has surpassed China’s to become the largest in the world, at over 1.4 billion people.

Through nine charts, this article unpacks trends and opportunities in the Indian travel market. Selected country examples shed light on how destinations can enhance their value propositions to attract and delight Indian travelers.

Indian globetrotters set to soar

Racing ahead: indian wanderlust is taking off, top picks: united arab emirates reigns, new gems discovered, regional flavors; global explorers.

Indian travelers are not a homogenous group; destination preferences vary across regions. For example, travelers from North India constitute a large share of travel to the United States and Canada, while two-thirds of travelers from Kerala prefer destinations in the Middle East. 1 India tourism statistics 2020 , Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, January 2021; MarketIS. Purpose of travel, distribution of the diaspora, and cultural linkages play a role in destination choice.

Destination matchmaking: Five ways to build value

Destinations looking to harness the full potential of the growing Indian market could consider tailoring their value propositions in alignment with one or more of the five key decision points that influence where travelers choose to go. Destinations might ask the following questions to determine which factors align with what Indian travelers look for when planning a trip.

- Research. How attractive and popular is the destination with Indian tourists?

- Accessibility. Is it easy to obtain a travel visa?

- Connectivity. Are there convenient flights that connect India to the destination?

- Booking. Is the destination affordable for Indian travelers, and is there an adequate supply of hotels in the appropriate price range?

- Travel experience. What is the on-the-ground experience like for Indian tourists in terms of weather, attractions, and whether or not the local population is English speaking?

There’s something for everyone in Thailand

Azerbaijan’s visa policy wows indian travelers, vietnam takes off: direct flights skyrocket arrivals.

In 2019, Kolkata was the only city in India with direct connectivity to Vietnam, and three other Indian cities offered sporadic flights. To stand out from Southeast Asia neighbors and gain popularity with Indian travelers, Vietnam improved direct connectivity from India by increasing flight frequency and adding new routes. Indian arrivals are now at an all-time high. 1 Data from Google trends and Diio Mi.

The luxury of Dubai is within reach

In 2022, India was the largest source market for leisure travelers to Dubai. 1 “1.24 million Indian tourists visit Dubai in first 9 months of 2022,” Business Standard , December 10, 2022. The city is known for its luxury offerings and, perhaps surprisingly, also offers a wide range of accommodations, such as 3-star options. And flights from India are affordable when compared with flights of similar distances. Taken together, these factors make the luxury of Dubai accessible to Indian travelers. 2 MarketIS.

Bollywood magic in Switzerland

While only 9 percent of Indian travelers focus on long-haul destinations in Western Europe, Switzerland has been an Indian top-20 destination for over a decade. Switzerland may be popular, as it feels familiar to Indian travelers: many Bollywood hits feature Swiss attractions, there are plenty of Indian restaurants and cultural festivals, and English is widely spoken. 1 “Switzerland and romantic songs of Indian movies,” Solo Backpacker, September 20, 2019; India-Switzerland relations , Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February, 2020; Festival of India in Switzerland and Liechtenstein – Events , Ministry of Culture, Government of India, 2018; Swiss hospitality for Indian guests , a joint report from HotellerieSuisse, Berne and Switzerland Tourism, November, 2019.

Namaste, India!

India is a high-potential, growing source market for leisure travel. Destinations looking to attract Indian leisure travelers could consider targeted marketing, an expanded range of affordable options, and customized on-the-ground hospitality that caters to Indian preferences. Destinations may need to take steps now to build a strong value proposition and distinguish themselves as a preferred location. To do so, they could take action in the following areas:

Destinations looking to attract Indian leisure travelers could consider targeted marketing, an expanded range of affordable options, and customized on-the-ground hospitality.

- Connect. Make travel seamless, for instance, by simplifying visa application processes and providing direct connectivity.

- Entice. Offer affordable packages with a range of choices that appeal to specific groups, such as families, couples, or solo travelers.

- Welcome. Make the experience traveler-friendly, for example, by providing appropriate food and beverage options like vegetarian and Indian cuisine.

- Attract . Design targeted campaigns to showcase experiences that Indian travelers want, and use appropriate channels to get the word out, for example leveraging over-the-air partnerships and social media.

- Unlock. Include the MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions) and business tourism segments in marketing efforts to boost interest in leisure travel.

Divya Aggarwal is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Gurugram office, Margaux Constantin is a partner in the Dubai office, and Kanika Kalra is a partner in the Mumbai office, where Neelesh Mundra is a senior partner.

The authors wish to thank Ashu Airan, Steffen Köpke, Richa Kothari, Karthik Krishnan, Kargil Mishra, and Jean Petersen for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

How Blackstone is helping to build India’s next generation of global companies

Opportunities for industry leaders as new travelers take to the skies

"People want to travel": 4 sector leaders say that tourism will change and grow

The global travel and tourism industry's post-pandemic recovery is gaining pace as the world’s pent-up desire for travel rekindles. Image: Unsplash/Anete Lūsiņa

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Anthony Capuano

Shinya katanozaka, gilda perez-alvarado, stephen kaufer.

Listen to the article

- In 2020 alone, the travel and tourism industry lost $4.5 trillion in GDP and 62 million jobs - the road to recovery remains long.

- The World Economic Forum’s latest Travel & Tourism Development Index gives expert insights on how the sector will recover and grow.

- We asked four business leaders in the sector to reflect on the state of its recovery, lessons learned from the pandemic, and the conditions that are critical for the future success of travel and tourism businesses and destinations.

The global travel and tourism sector’s post-pandemic recovery is gaining pace as the world’s pent-up desire for travel rekindles. The difference in international tourist arrivals in January 2021 and a similar period in January 2022 was as much as the growth in all of 2021. However, with $4.5 trillion in GDP and 62 million jobs lost in 2020 alone, the road to recovery remains long.

A few factors will greatly determine how the sector performs. These include travel restrictions, vaccination rates and health security, changing market dynamics and consumer preferences, and the ability of businesses and destinations to adapt. At the same time, the sector will need to prepare for future shocks.

The TTDI benchmarks and measures “the set of factors and policies that enable the sustainable and resilient development of the T&T sector, which in turn contributes to the development of a country”. The TTDI is a direct evolution of the long-running Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI), with the change reflecting the index’s increased coverage of T&T development concepts, including sustainability and resilience impact on T&T growth and is designed to highlight the sector’s role in broader economic and social development as well as the need for T&T stakeholder collaboration to mitigate the impact of the pandemic, bolster the recovery and deal with future challenges and risks. Some of the most notable framework and methodology differences between the TTCI and TTDI include the additions of new pillars, including Non-Leisure Resources, Socioeconomic Resilience and Conditions, and T&T Demand Pressure and Impact. Please see the Technical notes and methodology. section to learn more about the index and the differences between the TTCI and TTDI.

The World Economic Forum's latest Travel & Tourism Development Index highlights many of these aspects, including the opportunity and need to rebuild the travel and tourism sector for the better by making it more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient. This will unleash its potential to drive future economic and social progress.

Within this context, we asked four business leaders in the sector to reflect on the state of its recovery, lessons learned from the pandemic, and the conditions that are critical for the future success of travel and tourism businesses and destinations.

Have you read?

Are you a 'bleisure' traveller, what is a ‘vaccine passport’ and will you need one the next time you travel, a travel boom is looming. but is the industry ready, how to follow davos 2022, “the way we live and work has changed because of the pandemic and the way we travel has changed as well”.

Tony Capuano, CEO, Marriott International

Despite the challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the future looks bright for travel and tourism. Across the globe, people are already getting back on the road. Demand for travel is incredibly resilient and as vaccination rates have risen and restrictions eased, travel has rebounded quickly, often led by leisure.

The way many of us live and work has changed because of the pandemic and the way we travel has changed as well. New categories of travel have emerged. The rise of “bleisure” travel is one example – combining elements of business and leisure travel into a single trip. Newly flexible work arrangements, including the opportunity for many knowledge workers to work remotely, have created opportunities for extended travel, not limited by a Monday to Friday “9 to 5” workweek in the office.

To capitalize on this renewed and growing demand for new travel experiences, industry must join governments and policymakers to ensure that the right conditions are in place to welcome travellers as they prepare to get back on the road again, particularly those who cross international borders. Thus far, much of the recovery has been led by domestic and leisure travel. The incremental recovery of business and international travel, however, will be significant for the broader industry and the millions who make their livelihoods through travel and tourism.

Looking ahead to future challenges to the sector, be they public health conditions, international crises, or climate impacts, global coordination will be the essential component in tackling difficult circumstances head-on. International agreement on common – or at least compatible – standards and decision-making frameworks around global travel is key. Leveraging existing organizations and processes to achieve consensus as challenges emerge will help reduce risk and improve collaboration while keeping borders open.

“The travel and tourism sector will not be able to survive unless it adapts to the virtual market and sustainability conscience travellers”

Shinya Katanozaka, Representative Director, Chairman, ANA Holdings Inc.

At a time when people’s movements are still being restricted by the pandemic, there is a strong, renewed sense that people want to travel and that they want to go places for business and leisure.

In that respect, the biggest change has been in the very concept of “travel.”

A prime example is the rapid expansion of the market for “virtual travel.” This trend has been accelerated not only by advances in digital technologies, but also by the protracted pandemic. The travel and tourism sector will not be able to survive unless it adapts to this new market.

However, this is not as simple as a shift from “real” to “virtual.” Virtual experiences will flow back into a rediscovery of the value of real experiences. And beyond that, to a hunger for real experiences with clearer and more diverse purposes. The hope is that this meeting of virtual and actual will bring balance and synergy the industry.

The pandemic has also seen the emergence of the “sustainability-conscious” traveller, which means that the aviation industry and others are now facing the challenge of adding decarbonization to their value proposition. This trend will force a re-examination of what travel itself should look like and how sustainable practices can be incorporated and communicated. Addressing this challenge will also require stronger collaboration across the entire industry. We believe that this will play an important role in the industry’s revitalization as it recovers from the pandemic.

How is the World Economic Forum promoting sustainable and inclusive mobility systems?

The World Economic Forum’s Platform for Shaping the Future of Mobility works across four industries: aerospace and drones; automotive and new mobility; aviation travel and tourism; and supply chain and transport. It aims to ensure that the future of mobility is safe, clean, and inclusive.

- Through the Clean Skies for Tomorrow Coalition , more than 100 companies are working together to power global aviation with 10% sustainable aviation fuel by 2030.

- In collaboration with UNICEF, the Forum developed a charter with leading shipping, airlines and logistics to support COVAX in delivering more than 1 billion COVID-19 vaccines to vulnerable communities worldwide.

- The Road Freight Zero Project and P4G-Getting to Zero Coalition have led to outcomes demonstrating the rationale, costs and opportunities for accelerating the transition to zero emission freight.

- The Medicine from the Sky initiative is using drones to deliver vaccines and medicine to remote areas in India, completing over 300 successful trials.

- The Forum’s Target True Zero initiative is working to accelerate the deployment and scaling of zero emission aviation, leveraging electric and hydrogen flight technologies.

- In collaboration with the City of Los Angeles, Federal Aviation Administration, and NASA, the Forum developed the Principles of the Urban Sky to help adopt Urban Air Mobility in cities worldwide.

- The Forum led the development of the Space Sustainability Rating to incentivize and promote a more safe and sustainable approach to space mission management and debris mitigation in orbit.

- The Circular Cars Initiative is informing the automotive circularity policy agenda, following the endorsement from European Commission and Zero Emission Vehicle Transition Council countries, and is now invited to support China’s policy roadmap.

- The Moving India network is working with policymakers to advance electric vehicle manufacturing policies, ignite adoption of zero emission road freight vehicles, and finance the transition.

- The Urban Mobility Scorecards initiative – led by the Forum’s Global New Mobility Coalition – is bringing together mobility operators and cities to benchmark the transition to sustainable urban mobility systems.

Contact us for more information on how to get involved.

“The tourism industry must advocate for better protection of small businesses”

Gilda Perez-Alvarado, Global CEO, JLL Hotels & Hospitality

In the next few years, I think sustainability practices will become more prevalent as travellers become both more aware and interested in what countries, destinations and regions are doing in the sustainability space. Both core environmental pieces, such as water and air, and a general approach to sustainability are going to be important.

Additionally, I think conservation becomes more important in terms of how destinations and countries explain what they are doing, as the importance of climate change and natural resources are going to be critical and become top of mind for travellers.

The second part to this is we may see more interest in outdoor events going forward because it creates that sort of natural social distancing, if you will, or that natural safety piece. Doing outdoor activities such as outdoor dining, hiking and festivals may be a more appealing alternative to overcrowded events and spaces.

A lot of lessons were learned over the last few years, but one of the biggest ones was the importance of small business. As an industry, we must protect small business better. We need to have programmes outlined that successfully help small businesses get through challenging times.

Unfortunately, during the pandemic, many small businesses shut down and may never return. Small businesses are important to the travel and tourism sector because they bring uniqueness to destinations. People don’t travel to visit the same places they could visit at home; they prefer unique experiences that are only offered by specific businesses. If you were to remove all the small businesses from a destination, it would be a very different experience.

“Data shows that the majority of travellers want to explore destinations in a more immersive and experiential way”

Steve Kaufer, Co-Founder & CEO, Tripadvisor

We’re on the verge of a travel renaissance. The pandemic might have interrupted the global travel experience, but people are slowly coming out of the bubble. Businesses need to acknowledge the continued desire to feel safe when travelling. A Tripadvisor survey revealed that three-quarters (76%) of travellers will still make destination choices based on low COVID-19 infection rates.

As such, efforts to showcase how businesses care for travellers - be it by deep cleaning their properties or making items like hand sanitizer readily available - need to be ingrained within tourism operations moving forward.

But travel will also evolve in other ways, and as an industry, we need to be prepared to think digitally, and reimagine our use of physical space.

Hotels will become dynamic meeting places for teams to bond in our new hybrid work style. Lodgings near major corporate headquarters will benefit from an influx of bookings from employees convening for longer periods. They will also make way for the “bleisure” traveller who mixes business trips with leisure. Hotels in unique locales will become feasible workspaces. Employers should prepare for their workers to tag on a few extra days to get some rest and relaxation after on-location company gatherings.

Beyond the pandemic, travellers will also want to explore the world differently, see new places and do new things. Our data reveals that the majority want to explore destinations in a more immersive and experiential way, and to feel more connected to the history and culture. While seeing the top of the Empire State building has been a typical excursion for tourists in New York city, visitors will become more drawn to intimate activities like taking a cooking class in Brooklyn with a family of pizza makers who go back generations. This will undoubtedly be a significant area of growth in the travel and tourism industry.

Governments would be smart to plan as well, and to consider an international playbook that helps prepare us for the next public health crisis, inclusive of universal vaccine passports and policies that get us through borders faster.

Understanding these key trends - the ongoing need to feel safe and the growing desire to travel differently - and planning for the next crisis will be essential for governments, destinations, and tourism businesses to succeed in the efforts to keep the world travelling.

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Share this content.

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Tourism’s Importance for Growth Highlighted in World Economic Outlook Report

- All Regions

- 10 Nov 2023

Tourism has again been identified as a key driver of economic recovery and growth in a new report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). With UNWTO data pointing to a return to 95% of pre-pandemic tourist numbers by the end of the year in the best case scenario, the IMF report outlines the positive impact the sector’s rapid recovery will have on certain economies worldwide.

According to the World Economic Outlook (WEO) Report , the global economy will grow an estimated 3.0% in 2023 and 2.9% in 2024. While this is higher than previous forecasts, it is nevertheless below the 3.5% rate of growth recorded in 2022, pointing to the continued impacts of the pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and from the cost-of-living crisis.

Tourism key sector for growth

The WEO report analyses economic growth in every global region, connecting performance with key sectors, including tourism. Notably, those economies with "large travel and tourism sectors" show strong economic resilience and robust levels of economic activity. More specifically, countries where tourism represents a high percentage of GDP have recorded faster recovery from the impacts of the pandemic in comparison to economies where tourism is not a significant sector.

As the report Foreword notes: "Strong demand for services has supported service-oriented economies—including important tourism destinations such as France and Spain".

Looking Ahead

The latest outlook from the IMF comes on the back of UNWTO's most recent analysis of the prospects for tourism, at the global and regional levels. Pending the release of the November 2023 World Tourism Barometer , international tourism is on track to reach 80% to 95% of pre-pandemic levels in 2023. Prospects for September-December 2023 point to continued recovery, driven by the still pent-up demand and increased air connectivity particularly in Asia and the Pacific where recovery is still subdued.

Related links

- Download the News Release on PDF

- UNWTO World Tourism Barometer

- IMF World Economic Outlook

Category tags

Related content, international tourism reached 97% of pre-pandemic level..., international tourism to reach pre-pandemic levels in 2024, international tourism to end 2023 close to 90% of pre-p..., international tourism swiftly overcoming pandemic downturn.

Tourism Potential Index (TPI) – An Assessment of 60 Major Developed and Emerging Countries in the Global Tourism Market, 2023

All the vital news, analysis, and commentary curated by our industry experts.

Published: September 12, 2023 Report Code: GDTT-IR23-07-ST

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Threads

- Share via Email

- Report Overview

Table of Contents

Tourism potential index (tpi) report overview.

GlobalData’s Tourism Potential Index is a quantitative measure of the appeal of tourism in a location. It is determined by considering several characteristics such as tourism activity, macroeconomics, infrastructure and development, attractiveness, and risk associated with a destination.

Tourism Potential Index

Buy Full Report to Know More about the Tourism Potential Index

Download A Free Report Sample

The Tourism Potential Index (TPI) developed by GlobalData offers a comprehensive assessment of the growth prospects in the tourism industries of 60 prominent developed and emerging markets worldwide. This report explores the pillars and indicators used to determine the total potential index in detail.

Pillar 1 – Tourism Activity

The US ranks the highest with full marks in terms of “Market Size-Tourism Demand and Flows”, “Market Size-Tourism Spending Patterns”, “Tourism Construction Projects, and “Foreign Direct Investment” pillars. This makes it a competitive destination market. Furthermore, it is the biggest economic market in the world and a melting pot of different ethnicities and cultures. While Indonesia ranks third in the “Tourism Activity” pillar, India is ranked somewhere in the middle of the overall score. Indonesia is famous among some of the countries in APAC as a budget-friendly destination and India’s cultural diversity, historical heritage, and lively festivals continue to be significant draws for tourists.

Buy the Full Report to Know More about the Pillars of Tourism Potential Index

Pillar 2 - Macroeconomics

The Philippines ranks highest in the macroeconomics pillar. In terms of tourism employment, tourism contribution to GDP, and capital investment in travel and tourism, the Philippines performs well due to its abundant natural and cultural resources, low cost of living, safe and friendly population, improved infrastructure, and strong government backing. Thailand boasts the world’s highest tourism GDP contribution due to its abundant natural and cultural riches, affordability, safe and friendly inhabitants, improved infrastructure, and strong government support. Hence, it ranks fifth in the macroeconomics pillar.

Pillar 3 – Risk

The risk index has six sub-pillars which are macroeconomic risks, political environment, legal environment, demographic & social structure, technology & infrastructure, and environment. Since Denmark, Singapore, and Switzerland excel in all six areas, they register a ‘Very Low Risk’ rating. These countries are politically stable with developed, diverse economies and share a very high standard of living as a key characteristic. This low-risk, high-safety image can be marketed as a positive to tourists, who cite safety as a major concern and influential purchasing factor.

Pillar 4 – Infrastructure and Development

The UK exhibits a superior position in terms of tourism infrastructure and growth owing to its abundant and multifaceted historical and cultural heritage, various landscapes, well-established transit networks, secure and hospitable atmosphere, robust tourism sector, and advancements in technology. Additionally, Singapore’s outstanding transit connections, secure and clean environment, variety of attractions, and hospitable and inviting people help it rank fourth in terms of tourism infrastructure and development. The well-established transportation system in the country makes getting about the city-state simple.

GlobalData’s Tourism Potential Index (TPI) is designed to provide a standardized view of the underlying level of potential for expansion in the tourism sectors of 60 major developed and emerging markets around the world.

Reasons to Buy

- GlobalData’s Tourism Potential Index uses analysis and numerous data sources to provide an aggregated view of the global tourism market.

- The report uses a robust, data-driven methodology to give the reader a clear insight into the potential of 60 key tourist markets.

- Our analysts have analyzed the data to draw out the key findings from the data index model.

Frequently asked questions

Some of the pillars of the Tourism Potential Index are tourism activity, macroeconomics, risk, and infrastructure and development, among others.

Malaysia has secured the top spot (first) in GlobalData’s Tourism Potential Index.

The US ranks the highest with full marks in terms of the tourism activity pillar.

The Philippines ranks highest in the macroeconomics pillar.

- Currency Conversion is for Indicative purpose only. All orders are processed in US Dollars only.

- USD - US Dollar

- AUD — Australian Dollar

- BRL — Brazilian Real

- CNY — Yuan Renminbi

- GBP — Pound Sterling

- INR — Indian Rupee

- JPY — Japanese Yen

- ZAR — South African Rand

- USD — US Dollar

- RUB — Russian Ruble

Can be used by individual purchaser only

Can be shared by unlimited users within one corporate location e.g. a regional office

Can be shared globally by unlimited users within the purchasing corporation e.g. all employees of a single company

Undecided about purchasing this report?

Get in touch to find out about multi-purchase discounts.

[email protected] Tel +44 20 7947 2745

Every customer’s requirement is unique. With over 220,000 construction projects tracked, we can create a tailored dataset for you based on the types of projects you are looking for. Please get in touch with your specific requirements and we can send you a quote.

Sample Report

Tourism Potential Index (TPI) – An Assessment of 60 Major Developed and Emerging Countries in the Global Tourism Market, 2023 was curated by the best experts in the industry and we are confident about its unique quality. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer free sample pages to help you:

- Assess the relevance of the report

- Evaluate the quality of the report

- Justify the cost

Download your copy of the sample report and make an informed decision about whether the full report will provide you with the insights and information you need.

Below is a sample report to understand what you are buying

“The GlobalData platform is our go-to tool for intelligence services. GlobalData provides an easy way to access comprehensive intelligence data around multiple sectors, which essentially makes it a one-for-all intelligence platform, for tendering and approaching customers.

GlobalData is very customer orientated, with a high degree of personalised services, which benefits everyday use. The highly detailed project intelligence and forecast reports can be utilised across multiple departments and workflow scopes, from operational to strategic level, and often support strategic decisions. GlobalData Analytics and visualisation solutions has contributed positively when preparing management presentations and strategic papers.”

“COVID-19 has caused significant interference to our business and the COVID-19 intelligence from GlobalData has helped us reach better decisions around strategy. These two highlights have helped enormously to understand the projections into the future concerning our business units, we also utilise the project database to source new projects for Liebherr-Werk to use as an additional source to pitch for new business.”

Your daily news has saved me a lot of time and keeps me up-to-date with what is happening in the market, I like that you almost always have a link to the source origin. We also use your market data in our Strategic Business Process to support our business decisions. By having everything in one place on the Intelligence Center it has saved me a lot of time versus looking on different sources, the alert function also helps with this.

Having used several other market research companies, I find that GlobalData manages to provide that ‘difficult-to-get’ market data that others can’t, as well as very diverse and complete consumer surveys.

Our experience with GlobalData has been very good, from the platform itself to the people. I find that the analysts and the account team have a high level of customer focus and responsiveness and therefore I can always rely on. The platform is more holistic than other providers. It is convenient and almost like a one stop shop. The pricing suite is highly competitive and value for our organisation.

I like reports that inform new segments such as the analysis on generation Z, millennials, the impact of COVID 19 to our banking customers and their new channel habits. Secondly the specialist insight on affluent sector significantly increases our understanding about this group of customers. The combination of those give us depth and breadth of the evolving market.

I’m in the business of answering and helping people make decisions so with the intelligence center I can do that, effectively and efficiently. I can share quickly key insights that answer and satisfy our country stakeholders by giving them many quality studies and primary research about competitive landscape beyond the outlook of our bank. It helps me be seen as an advisory partner and that makes a big difference. A big benefit of our subscription is that no one holds the whole data and because it allows so many people, so many different parts of our organisation have access, it enables all teams to have the same level of knowledge and decision support.

“I know that I can always rely on Globaldata’s work when I’m searching for the right consumer and market insights. I use Globaldata insights to understand the changing market & consumer landscape and help create better taste & wellbeing solutions for our customers in food, beverage and healthcare industries.

Globaldata has the right data and the reports are of very high quality compared to your competitors. Globaldata not only has overall market sizes & consumer insights on food & beverages but also provides insights at the ingredient & flavour level. That is key for B2B companies like Givaudan. This way we understand our customers’ business and also gain insight to our unique industry”

GlobalData provides a great range of information and reports on various sectors that is highly relevant, timely, easy to access and utilise. The reports and data dashboards help engagement with clients; they provide valuable industry and market insights that can enrich client conversations and can help in the shaping of value propositions. Moreover, using GlobalData products has helped increase my knowledge of the finance sector, the players within it, and the general threats and opportunities.

I find the consumer surveys that are carried out to be extremely beneficial and not something I have seen anywhere else. They provided an insightful view of why and which consumers take (or don’t) particular financial products. This can help shape conversations with clients to ensure they make the right strategic decisions for their business.

One of the challenges I have found is that data in the payments space is often piecemeal. With GD all of the data I need is in one place, but it also comes with additional market reports that provide useful extra context and information. Having the ability to set-up alerts on relevant movements in the industry, be it competitors or customers, and have them emailed directly to me, ensures I get early sight of industry activity and don’t have to search for news.

Related reports

Every Company Report we produce is powered by the GlobalData Intelligence Center.

Subscribing to our intelligence platform means you can monitor developments at Tourism Potential Index (TPI) – An Assessment of 60 Major Developed and Emerging Countries in the Global Tourism Market, 2023 in real time.

- Access a live Tourism Potential Index (TPI) – An Assessment of 60 Major Developed and Emerging Countries in the Global Tourism Market, 2023 dashboard for 12 months, with up-to-the-minute insights.

- Fuel your decision making with real-time deal coverage and media activity.

- Turn insights on financials, deals, products and pipelines into powerful agents of commercial advantage.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture and the Environment

- Case Studies

- Chemistry and Toxicology

- Environment and Human Health

- Environmental Biology

- Environmental Economics

- Environmental Engineering

- Environmental Ethics and Philosophy

- Environmental History

- Environmental Issues and Problems

- Environmental Processes and Systems

- Environmental Sociology and Psychology

- Environments

- Framing Concepts in Environmental Science

- Management and Planning

- Policy, Governance, and Law

- Quantitative Analysis and Tools

- Sustainability and Solutions

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The role of tourism in sustainable development.

- Robert B. Richardson Robert B. Richardson Community Sustainability, Michigan State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.387

- Published online: 25 March 2021

Sustainable development is the foundational principle for enhancing human and economic development while maintaining the functional integrity of ecological and social systems that support regional economies. Tourism has played a critical role in sustainable development in many countries and regions around the world. In developing countries, tourism development has been used as an important strategy for increasing economic growth, alleviating poverty, creating jobs, and improving food security. Many developing countries are in regions that are characterized by high levels of biological diversity, natural resources, and cultural heritage sites that attract international tourists whose local purchases generate income and support employment and economic development. Tourism has been associated with the principles of sustainable development because of its potential to support environmental protection and livelihoods. However, the relationship between tourism and the environment is multifaceted, as some types of tourism have been associated with negative environmental impacts, many of which are borne by host communities.

The concept of sustainable tourism development emerged in contrast to mass tourism, which involves the participation of large numbers of people, often in structured or packaged tours. Mass tourism has been associated with economic leakage and dependence, along with negative environmental and social impacts. Sustainable tourism development has been promoted in various ways as a framing concept in contrast to these economic, environmental, and social impacts. Some literature has acknowledged a vagueness of the concept of sustainable tourism, which has been used to advocate for fundamentally different strategies for tourism development that may exacerbate existing conflicts between conservation and development paradigms. Tourism has played an important role in sustainable development in some countries through the development of alternative tourism models, including ecotourism, community-based tourism, pro-poor tourism, slow tourism, green tourism, and heritage tourism, among others that aim to enhance livelihoods, increase local economic growth, and provide for environmental protection. Although these models have been given significant attention among researchers, the extent of their implementation in tourism planning initiatives has been limited, superficial, or incomplete in many contexts.

The sustainability of tourism as a global system is disputed among scholars. Tourism is dependent on travel, and nearly all forms of transportation require the use of non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels for energy. The burning of fossil fuels for transportation generates emissions of greenhouse gases that contribute to global climate change, which is fundamentally unsustainable. Tourism is also vulnerable to both localized and global shocks. Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to localized shocks include the impacts of natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and civil unrest. Studies of the vulnerability of tourism to global shocks include the impacts of climate change, economic crisis, global public health pandemics, oil price shocks, and acts of terrorism. It is clear that tourism has contributed significantly to economic development globally, but its role in sustainable development is uncertain, debatable, and potentially contradictory.

- conservation

- economic development

- environmental impacts

- sustainable development

- sustainable tourism

- tourism development

Introduction

Sustainable development is the guiding principle for advancing human and economic development while maintaining the integrity of ecosystems and social systems on which the economy depends. It is also the foundation of the leading global framework for international cooperation—the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015 ). The concept of sustainable development is often associated with the publication of Our Common Future (World Commission on Environment and Development [WCED], 1987 , p. 29), which defined it as “paths of human progress that meet the needs and aspirations of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” Concerns about the environmental implications of economic development in lower income countries had been central to debates about development studies since the 1970s (Adams, 2009 ). The principles of sustainable development have come to dominate the development discourse, and the concept has become the primary development paradigm since the 1990s.

Tourism has played an increasingly important role in sustainable development since the 1990s, both globally and in particular countries and regions. For decades, tourism has been promoted as a low-impact, non-extractive option for economic development, particularly for developing countries (Gössling, 2000 ). Many developing countries have managed to increase their participation in the global economy through development of international tourism. Tourism development is increasingly viewed as an important tool in increasing economic growth, alleviating poverty, and improving food security. Tourism enables communities that are poor in material wealth, but rich in history and cultural heritage, to leverage their unique assets for economic development (Honey & Gilpin, 2009 ). More importantly, tourism offers an alternative to large-scale development projects, such as construction of dams, and to extractive industries such as mining and forestry, all of which contribute to emissions of pollutants and threaten biodiversity and the cultural values of Indigenous Peoples.

Environmental quality in destination areas is inextricably linked with tourism, as visiting natural areas and sightseeing are often the primary purpose of many leisure travels. Some forms of tourism, such as ecotourism, can contribute to the conservation of biodiversity and the protection of ecosystem functions in destination areas (Fennell, 2020 ; Gössling, 1999 ). Butler ( 1991 ) suggests that there is a kind of mutual dependence between tourism and the environment that should generate mutual benefits. Many developing countries are in regions that are characterized by high levels of species diversity, natural resources, and protected areas. Such ideas imply that tourism may be well aligned with the tenets of sustainable development.

However, the relationship between tourism and the environment is complex, as some forms of tourism have been associated with negative environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, land use, and food consumption (Butler, 1991 ; Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ; Hunter & Green, 1995 ; Vitousek et al., 1997 ). Assessments of the sustainability of tourism have highlighted several themes, including (a) parks, biodiversity, and conservation; (b) pollution and climate change; (c) prosperity, economic growth, and poverty alleviation; (d) peace, security, and safety; and (e) population stabilization and reduction (Buckley, 2012 ). From a global perspective, tourism contributes to (a) changes in land cover and land use; (b) energy use, (c) biotic exchange and extinction of wild species; (d) exchange and dispersion of diseases; and (e) changes in the perception and understanding of the environment (Gössling, 2002 ).

Research on tourism and the environment spans a wide range of social and natural science disciplines, and key contributions have been disseminated across many interdisciplinary fields, including biodiversity conservation, climate science, economics, and environmental science, among others (Buckley, 2011 ; Butler, 1991 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Lenzen et al., 2018 ). Given the global significance of the tourism sector and its environmental impacts, the role of tourism in sustainable development is an important topic of research in environmental science generally and in environmental economics and management specifically. Reviews of tourism research have highlighted future research priorities for sustainable development, including the role of tourism in the designation and expansion of protected areas; improvement in environmental accounting techniques that quantify environmental impacts; and the effects of individual perceptions of responsibility in addressing climate change (Buckley, 2012 ).

Tourism is one of the world’s largest industries, and it has linkages with many of the prime sectors of the global economy (Fennell, 2020 ). As a global economic sector, tourism represents one of the largest generators of wealth, and it is an important agent of economic growth and development (Garau-Vadell et al., 2018 ). Tourism is a critical industry in many local and national economies, and it represents a large and growing share of world trade (Hunter, 1995 ). Global tourism has had an average annual increase of 6.6% over the past half century, with international tourist arrivals rising sharply from 25.2 million in 1950 to more than 950 million in 2010 . In 2019 , the number of international tourists reached 1.5 billion, up 4% from 2018 (Fennell, 2020 ; United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2020 ). European countries are host to more than half of international tourists, but since 1990 , growth in international arrivals has risen faster than the global average, in both the Middle East and the Asia and Pacific region (UNWTO, 2020 ).

The growth in global tourism has been accompanied by an expansion of travel markets and a diversification of tourism destinations. In 1950 , the top five travel destinations were all countries in Europe and the Americas, and these destinations held 71% of the global travel market (Fennell, 2020 ). By 2002 , these countries represented only 35%, which underscores the emergence of newly accessible travel destinations in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Pacific Rim, including numerous developing countries. Over the past 70 years, global tourism has grown significantly as an economic sector, and it has contributed to the economic development of dozens of nations.

Given the growth of international tourism and its emergence as one of the world’s largest export sectors, the question of its impact on economic growth for the host countries has been a topic of great interest in the tourism literature. Two hypotheses have emerged regarding the role of tourism in the economic growth process (Apergis & Payne, 2012 ). First, tourism-led growth hypothesis relies on the assumption that tourism is an engine of growth that generates spillovers and positive externalities through economic linkages that will impact the overall economy. Second, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis emphasizes policies oriented toward well-defined and enforceable property rights, stable political institutions, and adequate investment in both physical and human capital to facilitate the development of the tourism sector. Studies have concluded with support for both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (e.g., Durbarry, 2004 ; Katircioglu, 2010 ) and the economic-led growth hypothesis (e.g., Katircioglu, 2009 ; Oh, 2005 ), whereas other studies have found support for a bidirectional causality for tourism and economic growth (e.g., Apergis & Payne, 2012 ; Lee & Chang, 2008 ).

The growth of tourism has been marked by an increase in the competition for tourist expenditures, making it difficult for destinations to maintain their share of the international tourism market (Butler, 1991 ). Tourism development is cyclical and subject to short-term cycles and overconsumption of resources. Butler ( 1980 ) developed a tourist-area cycle of evolution that depicts the number of tourists rising sharply over time through periods of exploration, involvement, and development, before eventual consolidation and stagnation. When tourism growth exceeds the carrying capacity of the area, resource degradation can lead to the decline of tourism unless specific steps are taken to promote rejuvenation (Butler, 1980 , 1991 ).

The potential of tourism development as a tool to contribute to environmental conservation, economic growth, and poverty reduction is derived from several unique characteristics of the tourism system (UNWTO, 2002 ). First, tourism represents an opportunity for economic diversification, particularly in marginal areas with few other export options. Tourists are attracted to remote areas with high values of cultural, wildlife, and landscape assets. The cultural and natural heritage of developing countries is frequently based on such assets, and tourism represents an opportunity for income generation through the preservation of heritage values. Tourism is the only export sector where the consumer travels to the exporting country, which provides opportunities for lower-income households to become exporters through the sale of goods and services to foreign tourists. Tourism is also labor intensive; it provides small-scale employment opportunities, which also helps to promote gender equity. Finally, there are numerous indirect benefits of tourism for people living in poverty, including increased market access for remote areas through the development of roads, infrastructure, and communication networks. Nevertheless, travel is highly income elastic and carbon intensive, which has significant implications for the sustainability of the tourism sector (Lenzen et al., 2018 ).

Concerns about environmental issues appeared in tourism research just as global awareness of the environmental impacts of human activities was expanding. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm in 1972 , the same year as the publication of The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al., 1972 ), which highlighted the concerns about the implications of exponential economic and population growth in a world of finite resources. This was the same year that the famous Blue Marble photograph of Earth was taken by the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft (Höhler, 2015 , p. 10), and the image captured the planet cloaked in the darkness of space and became a symbol of Earth’s fragility and vulnerability. As noted by Buckley ( 2012 ), tourism researchers turned their attention to social and environmental issues around the same time (Cohen, 1978 ; Farrell & McLellan, 1987 ; Turner & Ash, 1975 ; Young, 1973 ).

The notion of sustainable development is often associated with the publication of Our Common Future , the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, also known as the Brundtland Commission (WCED, 1987 ). The report characterized sustainable development in terms of meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987 , p. 43). Four basic principles are fundamental to the concept of sustainability: (a) the idea of holistic planning and strategy making; (b) the importance of preserving essential ecological processes; (c) the need to protect both human heritage and biodiversity; and (d) the need to develop in such a way that productivity can be sustained over the long term for future generations (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ). In addition to achieving balance between economic growth and the conservation of natural resources, there should be a balance of fairness and opportunity between the nations of the world.

Although the modern concept of sustainable development emerged with the publication of Our Common Future , sustainable development has its roots in ideas about sustainable forest management that were developed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries (Blewitt, 2015 ; Grober, 2007 ). Sustainable forest management is concerned with the stewardship and use of forests in a way that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, and regeneration capacity as well as their potential to fulfill society’s demands for forest products and benefits. Building on these ideas, Daly ( 1990 ) offered two operational principles of sustainable development. First, sustainable development implies that harvest rates should be no greater than rates of regeneration; this concept is known as maximum sustainable yield. Second, waste emission rates should not exceed the natural assimilative capacities of the ecosystems into which the wastes are emitted. Regenerative and assimilative capacities are characterized as natural capital, and a failure to maintain these capacities is not sustainable.

Shortly after the emergence of the concept of sustainable development in academic and policy discourse, tourism researchers began referring to the notion of sustainable tourism (May, 1991 ; Nash & Butler, 1990 ), which soon became the dominant paradigm of tourism development. The concept of sustainable tourism, as with the role of tourism in sustainable development, has been interpreted in different ways, and there is a lack of consensus concerning its meaning, objectives, and indicators (Sharpley, 2000 ). Growing interest in the subject inspired the creation of a new academic journal, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , which was launched in 1993 and has become a leading tourism journal. It is described as “an international journal that publishes research on tourism and sustainable development, including economic, social, cultural and political aspects.”

The notion of sustainable tourism development emerged in contrast to mass tourism, which is characterized by the participation of large numbers of people, often provided as structured or packaged tours. Mass tourism has risen sharply in the last half century. International arrivals alone have increased by an average annual rate of more than 25% since 1950 , and many of those trips involved mass tourism activities (Fennell, 2020 ; UNWTO, 2020 ). Some examples of mass tourism include beach resorts, cruise ship tourism, gaming casinos, golf resorts, group tours, ski resorts, theme parks, and wildlife safari tourism, among others. Little data exist regarding the volume of domestic mass tourism, but nevertheless mass tourism activities dominate the global tourism sector. Mass tourism has been shown to generate benefits to host countries, such as income and employment generation, although it has also been associated with economic leakage (where revenue generated by tourism is lost to other countries’ economies) and economic dependency (where developing countries are dependent on wealthier countries for tourists, imports, and foreign investment) (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Khan, 1997 ; Peeters, 2012 ). Mass tourism has been associated with numerous negative environmental impacts and social impacts (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Fennell, 2020 ; Ghimire, 2013 ; Gursoy et al., 2010 ; Liu, 2003 ; Peeters, 2012 ; Wheeller, 2007 ). Sustainable tourism development has been promoted in various ways as a framing concept in contrast to many of these economic, environmental, and social impacts.

Much of the early research on sustainable tourism focused on defining the concept, which has been the subject of vigorous debate (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Inskeep, 1991 ; Liu, 2003 ; Sharpley, 2000 ). Early definitions of sustainable tourism development seemed to fall in one of two categories (Sharpley, 2000 ). First, the “tourism-centric” paradigm of sustainable tourism development focuses on sustaining tourism as an economic activity (Hunter, 1995 ). Second, alternative paradigms have situated sustainable tourism in the context of wider sustainable development policies (Butler, 1991 ). One of the most comprehensive definitions of sustainable tourism echoes some of the language of the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainable development (WCED, 1987 ), emphasizing opportunities for the future while also integrating social and environmental concerns:

Sustainable tourism can be thought of as meeting the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunity for the future. Sustainable tourism development is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that we can fulfill economic, social and aesthetic needs while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems. (Inskeep, 1991 , p. 461)

Hunter argued that over the short and long terms, sustainable tourism development should

“meet the needs and wants of the local host community in terms of improved living standards and quality of life;

satisfy the demands of tourists and the tourism industry, and continue to attract them in order to meet the first aim; and

safeguard the environmental resource base for tourism, encompassing natural, built and cultural components, in order to achieve both of the preceding aims.” (Hunter, 1995 , p. 156)

Numerous other definitions have been documented, and the term itself has been subject to widespread critique (Buckley, 2012 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ). Nevertheless, there have been numerous calls to move beyond debate about a definition and to consider how it may best be implemented in practice (Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Liu, 2003 ). Cater ( 1993 ) identified three key criteria for sustainable tourism: (a) meeting the needs of the host population in terms of improved living standards both in the short and long terms; (b) satisfying the demands of a growing number of tourists; and (c) safeguarding the natural environment in order to achieve both of the preceding aims.

Some literature has acknowledged a vagueness of the concept of sustainable tourism, which has been used to advocate for fundamentally different strategies for tourism development that may exacerbate existing conflicts between conservation and development paradigms (Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ; McKercher, 1993b ). Similar criticisms have been leveled at the concept of sustainable development, which has been described as an oxymoron with a wide range of meanings (Adams, 2009 ; Daly, 1990 ) and “defined in such a way as to be either morally repugnant or logically redundant” (Beckerman, 1994 , p. 192). Sharpley ( 2000 ) suggests that in the tourism literature, there has been “a consistent and fundamental failure to build a theoretical link between sustainable tourism and its parental paradigm,” sustainable development (p. 2). Hunter ( 1995 ) suggests that practical measures designed to operationalize sustainable tourism fail to address many of the critical issues that are central to the concept of sustainable development generally and may even actually counteract the fundamental requirements of sustainable development. He suggests that mainstream sustainable tourism development is concerned with protecting the immediate resource base that will sustain tourism development while ignoring concerns for the status of the wider tourism resource base, such as potential problems associated with air pollution, congestion, introduction of invasive species, and declining oil reserves. The dominant paradigm of sustainable tourism development has been described as introverted, tourism-centric, and in competition with other sectors for scarce resources (McKercher, 1993a ). Hunter ( 1995 , p. 156) proposes an alternative, “extraparochial” paradigm where sustainable tourism development is reconceptualized in terms of its contribution to overall sustainable development. Such a paradigm would reconsider the scope, scale, and sectoral context of tourism-related resource utilization issues.

“Sustainability,” “sustainable tourism,” and “sustainable development” are all well-established terms that have often been used loosely and interchangeably in the tourism literature (Liu, 2003 ). Nevertheless, the subject of sustainable tourism has been given considerable attention and has been the focus of numerous academic compilations and textbooks (Coccossis & Nijkamp, 1995 ; Hall & Lew, 1998 ; Stabler, 1997 ; Swarbrooke, 1999 ), and it calls for new approaches to sustainable tourism development (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Garrod & Fyall, 1998 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Sharpley, 2000 ). The notion of sustainable tourism has been reconceptualized in the literature by several authors who provided alternative frameworks for tourism development (Buckley, 2012 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Hunter, 1995 ; Liu, 2003 ; McKercher, 1993b ; Sharpley, 2000 ).

Early research in sustainable tourism focused on the local environmental impacts of tourism, including energy use, water use, food consumption, and change in land use (Buckley, 2012 ; Butler, 1991 ; Gössling, 2002 ; Hunter & Green, 1995 ). Subsequent research has emphasized the global environmental impacts of tourism, such as greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity losses (Gössling, 2002 ; Gössling & Peeters, 2015 ; Lenzen et al., 2018 ). Additional research has emphasized the impacts of environmental change on tourism itself, including the impacts of climate change on tourist behavior (Gössling et al., 2012 ; Richardson & Loomis, 2004 ; Scott et al., 2012 ; Viner, 2006 ). Countries that are dependent on tourism for economic growth may be particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (Richardson & Witkoswki, 2010 ).

The early focus on environmental issues in sustainable tourism has been broadened to include economic, social, and cultural issues as well as questions of power and equity in society (Bramwell & Lane, 1993 ; Sharpley, 2014 ), and some of these frameworks have integrated notions of social equity, prosperity, and cultural heritage values. Sustainable tourism is dependent on critical long-term considerations of the impacts; notions of equity; an appreciation of the importance of linkages (i.e., economic, social, and environmental); and the facilitation of cooperation and collaboration between different stakeholders (Elliott & Neirotti, 2008 ).

McKercher ( 1993b ) notes that tourism resources are typically part of the public domain or are intrinsically linked to the social fabric of the host community. As a result, many commonplace tourist activities such as sightseeing may be perceived as invasive by members of the host community. Many social impacts of tourism can be linked to the overuse of the resource base, increases in traffic congestion, rising land prices, urban sprawl, and changes in the social structure of host communities. Given the importance of tourist–resident interaction, sustainable tourism development depends in part on the support of the host community (Garau-Vadell et al., 2018 ).

Tourism planning involves the dual objectives of optimizing the well-being of local residents in host communities and minimizing the costs of tourism development (Sharpley, 2014 ). Tourism researchers have paid significant attention to examining the social impacts of tourism in general and to understanding host communities’ perceptions of tourism in particular. Studies of the social impacts of tourism development have examined the perceptions of local residents and the effects of tourism on social cohesion, traditional lifestyles, and the erosion of cultural heritage, particularly among Indigenous Peoples (Butler & Hinch, 2007 ; Deery et al., 2012 ; Mathieson & Wall, 1982 ; Sharpley, 2014 ; Whitford & Ruhanen, 2016 ).

Alternative Tourism and Sustainable Development

A wide body of published research is related to the role of tourism in sustainable development, and much of the literature involves case studies of particular types of tourism. Many such studies contrast types of alternative tourism with those of mass tourism, which has received sustained criticism for decades and is widely considered to be unsustainable (Cater, 1993 ; Conway & Timms, 2010 ; Fennell, 2020 ; Gursoy et al., 2010 ; Liu, 2003 ; Peeters, 2012 ; Zapata et al., 2011 ). Still, some tourism researchers have taken issue with the conclusion that mass tourism is inherently unsustainable (Sharpley, 2000 ; Weaver, 2007 ), and some have argued for developing pathways to “sustainable mass tourism” as “the desired and impending outcome for most destinations” (Weaver, 2012 , p. 1030). In integrating an ethical component to mass tourism development, Weaver ( 2014 , p. 131) suggests that the desirable outcome is “enlightened mass tourism.” Such suggestions have been contested in the literature and criticized for dubious assumptions about emergent norms of sustainability and support for growth, which are widely seen as contradictory (Peeters, 2012 ; Wheeller, 2007 ).

Models of responsible or alternative tourism development include ecotourism, community-based tourism, pro-poor tourism, slow tourism, green tourism, and heritage tourism, among others. Most models of alternative tourism development emphasize themes that aim to counteract the perceived negative impacts of conventional or mass tourism. As such, the objectives of these models of tourism development tend to focus on minimizing environmental impacts, supporting biodiversity conservation, empowering local communities, alleviating poverty, and engendering pleasant relationships between tourists and residents.

Approaches to alternative tourism development tend to overlap with themes of responsible tourism, and the two terms are frequently used interchangeably. Responsible tourism has been characterized in terms of numerous elements, including

ensuring that communities are involved in and benefit from tourism;

respecting local, natural, and cultural environments;

involving the local community in planning and decision-making;

using local resources sustainably;

behaving in ways that are sensitive to the host culture;