Albatrosses are threatened with extinction – and climate change could put their nesting sites at risk

Postdoctoral research fellow, Department of Plant and Soil Science, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement

Mia Momberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

The wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) is the world’s largest flying bird , with a wingspan reaching an incredible 3.5 metres. These birds are oceanic nomads: they spend most of their 60 years of life at sea and only come to land to breed approximately every two years once they have reached sexual maturity.

Their playground is the vast Southern Ocean – the region between the latitude of 60 degrees south and the continent of Antarctica – and the scattered islands within this ocean where they make their nests.

Marion Island and Prince Edward Island , about 2,300km south of South Africa, are some of the only land masses for thousands of kilometres in the Southern Ocean.

Together, these two islands support about half of the entire world’s wandering albatross breeding population, estimated at around 20,000 mature individuals . Every year scientists from South African universities survey Marion Island to locate and record each wandering albatross nest.

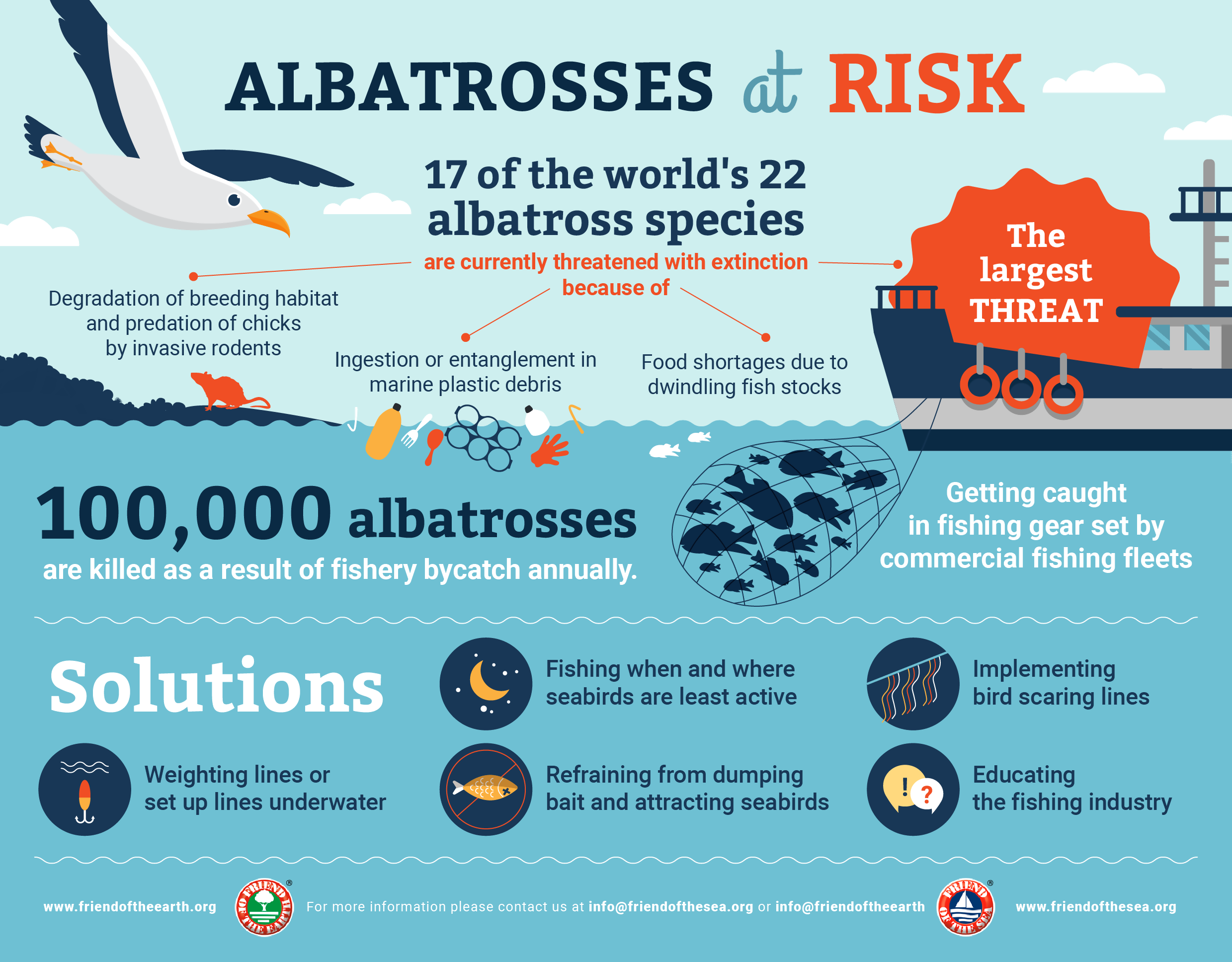

The species, listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature , faces huge risks while in the open ocean, in particular due to bycatch from longline fishing trawlers. This makes it important to understand their breeding ecology to ensure that the population remains stable.

I was part of a study during 2021 to investigate which environmental variables affect the birds’ choice of nest site on Marion Island. The birds make their nests – a mound of soil and vegetation – on the ground. We looked at wind characteristics, vegetation and geological characteristics at nest locations from three breeding seasons.

Elevation turned out to be the most important variable – the albatrosses preferred a low (warmer) site and coastal vegetation. But these preferences also point to dangers for the birds from climate change. The greatest risk to the availability of nesting sites will be a much smaller suitable nesting range in future than at present. This could be devastating to the population.

Variables influencing nest site selection

Marion Island is of volcanic origin and has a rough terrain. Some areas are covered in sharp rock and others are boggy, with very wet vegetation. There is rain and strong wind on most days. Conducting research here requires walking long distances in all weathers – but the island is ideal for studying climate change, because the Southern Ocean is experiencing some of the largest global changes in climate and it is relatively undisturbed by humans.

Using GPS coordinate nest data from the entire breeding population on Marion Island, we aimed to determine which factors affected where the birds breed. With more than 1,900 nests, and 10,000 randomly generated points where nests are not present, we extracted:

elevation (which on this island is also a proxy for temperature)

terrain ruggedness

distance to the coast

vegetation type

wind turbulence

underlying geology.

The variables were ranked according to their influence on the statistical model predicting the likelihood of a nest being present under the conditions found at a certain point.

The most important variable was elevation. The majority of the nests were found close to the coast, where the elevation is lower. These areas are warmer, which means that the chicks would be less exposed to very cold temperatures on their open nests.

The probability of nests being present also declined with distance from the coast, probably because there are more suitable habitats closer to the coast.

Vegetation type was strongly determined by elevation and distance from the coast. This was an important factor, as the birds use vegetation to build their nests. In addition, dead vegetation contributes to the soil formation on the island, which is also used in nest construction.

The probability of encountering nests is lower as the terrain ruggedness increases since these birds need a runway of flat space to use for take-off and landing. During incubation, the adults take turns to remain on the nest. Later they will leave the chick on its own for up to 10 days at a time. They continue to feed the chick for up to 300 days.

Areas with intermediate wind speeds were those most likely to have a nest. At least some wind is needed for flight, but too much wind may cause chicks to blow off the nests or become too cold.

Delicate balance

Changing climates may upset this delicate balance. Human-driven changes will have impacts on temperature, rainfall and wind speeds, which in turn affect vegetation and other species distribution patterns .

By 2003, Marion Island’s temperature had increased by 1.2°C compared to 50 years before. Precipitation had decreased by 25% and cloud cover also decreased, leading to an increase in sunshine hours . The permanent snowline which was present in the 1950s no longer exists . These changes have continued in the 20 years since their initial documentation, and are likely to continue.

Strong vegetation shifts were already documented in the sub-Antarctic years ago. Over 40 years, many species have shifted their ranges to higher elevations where the temperatures remain cooler. Wind speeds have also already increased in the Southern Ocean and are predicted to continue doing so, which may have effects on the size of areas suitable for nesting.

If nesting sites move to higher elevations on Marion Island as temperatures warm, and some areas become unsuitable due to changes in vegetation or wind speeds, it is likely that the suitable nesting area on the island will shrink considerably.

Our study adds to what is known about the elements affecting nest-site selection in birds. Notably, we add knowledge of wind, an underexplored element, influencing nest-site selection in a large oceanic bird. The results could also provide insights that apply to other surface-nesting seabirds.

- Climate change

- Southern ocean

- Natural world

Program Manager, Teaching & Learning Initiatives

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Wandering Albatross: Is This Animal Endangered?

By: Author Our Endangered World

Posted on Last updated: September 26, 2023

Wandering albatross populations have been declining because of human activities; we need to make sure we protect them so that Wandering Albatrosses can continue to wander. These seabirds are large seabirds native to the Southern Hemisphere.

- Status: Vulnerable

- Known as : Wandering Albatross, White-winged albatross, snowy albatross.

- Estimated numbers left in the wild: 20,000 adults.

- Fun fact: Wandering albatrosses can eat to such excess at times that they are unable to fly and have to rest helplessly on the water.

Wandering albatross populations have been declining because of human activities, and Wandering albatrosses need our help in order for them to continue their migration patterns. The wandering albatross is a vulnerable species that need protection from humans in order to survive.

Table of Contents

Description

Vast and graceful, the wandering albatross spreads its wings towards the south like the biblical hawk, cruising the southern hemisphere’s skies on pinions that spread up to 3.5 meters, the largest wingspan found in any living bird .

Wandering albatrosses like albatross can migrate for thousands of miles, depending on which hemisphere Wandering Albatross is in.

Their chicks are very vulnerable until they grow their adult feathers, and Wandering Albatross adults are often captured by long-line fishing every year, which is harmful to the albatross populations.

- They migrate for thousands of miles to spend winter months in Antarctica and summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

This albatross species are very rare, with only 50 estimated left in the world.

The seabird faces many threats such as pollution, disturbance due to man-made sources like fishing boats and wind turbines, and predation by invasive species.

Anatomy and Appearance

These albatrosses measure 1.1 meters long and can weigh 10 kilograms. Their snowy white feathers and black and white wings give them a handsome appearance, especially contrasted with the ocean’s deep blue, while their beaks are long, sturdy, and yellowish, adapted for snapping up prey. They have the longest wingspan and shallow dives.

The albatross is superbly adapted for soaring flight despite its large size and can glide for hours before it needs to beat its wings to regain height.

When not breeding, these birds spend all their time at sea, far from even the island’s limited land . They sleep on the water’s surface and spend days gliding and flying in search of food.

See Related : Andean Flamingo

The Wandering albatross is found over the oceans of the southern hemisphere. Airborne for much of their lives, these huge birds also rest on the sea’s surface.

They travel to a handful of remote islands outside the Antarctic Circle to breed, including Prince Edward Island, Crozet Island, South Georgia Island, and Macquarie Island.

Its living range covers 65 million square kilometers, and its breeding area is confined to just under 2,000 square kilometers.

Wandering Albatross Habitat

Wandering albatrosses live in the Southern Hemisphere and mainly Antarctica. This seabird flies very long distances to migrate every year, making them one of the most well-traveling birds in the world.

They tend to stay in their typical coastal habitat which is around the sea and land with enough food for them to survive.

Wandering Albatrosses are not just found in one area of the world, they are all over the southern half of the world.

The bird commonly breed on islands off South America, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and island territories of the United Kingdom near Antarctica.

Wandering Albatross Diet and Nutrition

Wandering Albatrosses are opportunistic feeders and will consume a variety of prey items. Their diet consists of cephalopods, fish, crustaceans, and marine mammals. They have also been known to eat seabirds, including penguins.

The birds are night feeders. Squid and fish schools are their favored feeding areas, though they also follow fishing boats to gobble up refuse – and thus possibly run afoul of long-line fishing lines.

They are prodigious wanderers and can travel up to 6,000 kilometers in twelve days. Patagonian toothfish is a favorite food, but any squid or fish that can be seized at the surface in the bird’s powerful beak will do.

These birds catch their prey with their bills and feet, but will also snatch at prey off the water’s surface. They can swallow small prey whole and regurgitate indigestible parts such as bones, scales, and fins.

Wandering Albatross Mating Habits

Wandering Albatrosses are known for their elaborate mating rituals. The males and females perform a dance together, and the male will offer the female a gift of food.

If the female accepts the gift, the two birds will mate. They are monogamous throughout their lives. The seabird is found in the Southern Hemisphere, but they migrate for thousands of miles to spend winter months in Antarctica and summer months in the Northern Hemisphere.

Many Wandering Albatrosses lay one egg, but breeding albatrosses have been reported to lay up to three eggs. These seabird species are monogamous and mate for life.

Wandering Albatrosses have a courtship ritual that involves circling the mate before copulation. The Wandering Albatross is a very long-lived bird with a lifespan of 60-70 years in the wild.

Albatrosses mate for life and nest in colonies on remote southern islands close to the Antarctic circle. They build large nests out of moss and other vegetation and lay a single elongated, 10-centimeter egg, which is cared for alternately by both parents.

The young albatross takes about nine months to fledge, during which time its parents feed it. If they do not run afoul of fishing lines or die from ingested plastic garbage , albatrosses can live for up to half a century in the wild.

See Related : Most Interesting Birds in the World

Wandering Albatross and Human Relationship

Wandering Albatrosses are well known to have a strong, though not always successful, relationship with humans.

They often mistake boats and wind turbines as resting spots. This is because Wandering Albatrosses often imitate other albatrosses who are sitting on these structures.

The seabird is also threatened by invasive species that humans introduce o their habitats such as rats, pigs, cats, and dogs which prey on their chicks or kill adult Albatrosses by stealing their food caches.

Role in the Ecosystems

Wandering Albatrosses play a very important role in the ecosystem. They are considered “charismatic megafauna”, meaning they are large, easily identifiable animals that are popular with the public.

Their popularity draws attention to the conservation issues that they face and helps to raise awareness about the dangers they face.

They are important in the ecosystem because these birds are large seabirds that mainly feed on crustaceans. They can form massive breeding colonies on coasts and islands occurring at more than one hundred sites, where they nest or lay their eggs.

Wandering Albatross Facts

Here are the interesting facts you need to know about this species.

- The Wandering Albatross is a large seabird and the only member of the genus Diomedea.

- They can be found around almost all of the Southern Ocean.

- The seabirds nest on many sub-Antarctic islands where they are threatened by many invasive species.

- They are the largest seabird in the world.

- They have a wingspan of up to 11 feet and can weigh up to 30 pounds.

- The albatross eat fish and squid and they hunt at night while gliding over the ocean.

See Related: These Are 13 of the Longest Living Animals on Earth

Conservation Status

The Wandering Albatross is currently listed as a vulnerable species This is because the bird’s population has declined by more than 50% in the past three generations. There are many threats that face albatrosses, and conservationists are working hard to protect these animals.

Their colonies are also jeopardized due to human encroachment on nesting areas without proper conservation efforts.

The wandering albatross is relatively well protected, both by its remote location and by-laws. However, its population is still slowly declining for slightly mysterious reasons.

The most likely culprits are long-line fishing fatalities, as the birds become hooked and drown, and plastics’ ingestion can kill both chicks and adults.

The birds were once hunted for feathers for women’s hats, but this practice is long gone thanks to changing fashion. Kerguelen Island is infested with feral cats, which have wiped out entire broods of chicks.

See Related : Causes of Extinction You Should Know About

Conservation efforts

The islands where the wandering albatross nests are thoroughly protected as nature reserves and, in one case, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Improved long-line fishing regulations have dramatically reduced the by-catch of these beautiful animals, and more measures are being developed.

Cats have been exterminated from another island they colonized, and further extirpation efforts are being carried out or are planned.

Albatrosses and Petrels Conservation

In 2001, the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels was formed to help better protect these creatures. The agreement is a collaborative effort between 24 different nations, including the United States of America.

The main goals of the agreement are to:

- reduce bycatch and mortality of albatrosses and petrels;

- identify and mitigate threats to albatrosses and petrels, including climate change ; promote effective management of albatrosses and petrels; and

- increase public awareness of the importance of albatrosses and petrels.

Captive Breeding

One way that researchers are trying to save seabird is by captive breeding. Captive breeding is when animals are bred in controlled settings, such as zoos or wildlife sanctuaries. This is done in an effort to increase the population size of a species and reduce the risk of extinction.

So far, captive breeding has been successful for these sea bird species. The albatross captive population or breeding population added to the total population that has increased to about 1100 individuals since captive breeding was started in 2004.

Organizations

Do you know of or are you a part of an organization that works to conserve the Amsterdam Albatross ? Then please contact us to have it featured on Our Endangered World .

See Related : Fascinating Facts About Conservation

Final Thoughts

Wandering Albatrosses are large seabirds that migrate to spend the winter in Antarctica and summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

They face many threats such as pollution, disturbance due to man-made sources like fishing boats and wind turbines, predation by invasive species such as rats, pigs, cats, and dogs. The bird is currently listed as a vulnerable species This is because its population has declined by more than 50% in 3 generations.

There are many conservation efforts being undertaken for this animal including improved long-line fishing regulations which have reduced the bycatch of these birds dramatically.

Also eradicating feral cats from one island they had colonized with plans for further extirpations underway. With so much work being done for this animal, Wandering Albatrosses will hopefully become less vulnerable.

What is Wandering Albatross?

Wandering Albatross are large seabirds that have a wingspan of 6.6 ft and are larger than the wingspan of any bird– it is the largest living member of the family Diomedeidae.

Wanderers can be found in subtropical regions throughout Southern Hemisphere, nesting on isolated islands and coastal cliffs. Wanderers typically migrate for thousands of miles to spend winter months in Antarctica and summer in the Southern Hemisphere.

Where is the wandering albatross found?

Wandering albatrosses migrate for thousands of kilometers each year to spend the winter in Antarctica and summer in the southern oceans.

How many Wandering Albatrosses are left in the world?

It’s not easy to count Wandering Albatross populations. The species is present in five continents and its population is being evaluated everywhere it is found.

It’s 11,000 of this species according to Guinness World Records 2004 edition. World Wildlife Fund estimates that there are 12,000 today globally, but noted many surveys still need to be done before a reliable estimate can be obtained.

Why is Wandering Albatrosses threatened?

Wandering Albatrosses are threatened by the erosion of their nesting site, habitat destruction caused by people settling around the albatross’s breeding grounds and roosting sites, and predation of the seabird’s chicks.

Many dangers endanger the subterranean world, including pollution, human activity, and other man-made factors such as boats and wind turbines. Rat predation is one of the most common threats to these creatures.

Are wandering albatross still alive?

The wandering albatross is still alive! They migrate for vast distances. These albatross is a vulnerable species because they face many different environmental factors that threaten their survival.

How long can a wandering albatross fly nonstop?

Wandering Albatross is not able to fly nonstop due to its large size. They are able to glide for two hours without needing a break but cannot refuel in flight, and may require months of food and water when they land at breeding sites.

The sea bird often lands on ships and buildings in search of food and water because natural sources like seals, penguins, plankton, krill, or squid can no longer support them without threats from pollution or other man-made properties such as boats or wind turbines.

Other Species Profile

- Great White Shark

- African Lion

- Crowned Eagle

Related Resources

- Famous Environmental Leaders

- Important Pros and Cons of Culling Animals

- Animals that Starts with Letter X

Read These Other Guide

- Vole vs Shrew: Size, Color, and Habitat Comparison

- 22 Different Types of Wolves in the World

- Are Deer Salt Licks Illegal? Understanding Wildlife Regulations and State Laws

- Are There Alligators in Europe? Here’s What to Know

- Are Deer Friendly? Understanding Deer Behavior Towards Humans and Other Wildlife

- 18 Most Hardworking Animals on the Planet

The Amazing Albatrosses

They fly 50 miles per hour. Go years without touching land. Predict the weather. And they’re among the world’s most endangered birds

Kennedy Warne

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/alba_main_388.jpg)

Through the fog steamed our yacht, Mahalia , sliding down gray ocean swells. The gale that had kept us in port for three days in the Chatham Islands, east of New Zealand, had blown itself out, and banks of sea mist lolled in its wake. A fogbow formed on the horizon, and through its bright arch albatrosses rose and fell in an endless roller-coaster glide. Ahead, the mist thinned to reveal a fang of rock rearing 570 feet out of the sea: the Pyramid, the sole breeding site of the Chatham albatross. Around its shrouded summit the regal birds wheeled by the hundreds, their plangent wails and strange kazoo-like cackles echoing off the black volcanic slopes.

The Mahalia 's skipper lowered an inflatable dinghy and ran me ashore. Fur seals roused themselves to watch our approach, then, taking fright, tobogganed into the sea. The skipper positioned the craft against a barnacled rock face—no mean feat in the six-foot swells—and I jumped, gripping rubbery stalks of bull kelp and pulling myself up to a jumble of boulders. Sidestepping the fetid pools where seals had been lying, I scrambled up to the only level part of the island, an area about the size of a tennis court, where Paul Scofield, an ornithologist and expert on the Chatham albatross, and his assistant Filipe Moniz had pitched tents, anchoring them with three-inch-long fishhooks wedged into crevices in the rock.

A few feet away a partly fledged Chatham albatross chick stood up on its pedestal nest, yawned and shook its shaggy wings. Then it flumped down with the stoical look one might expect from a creature that had sat on a nest for three months and had another month or two to go.

Around the Pyramid colony adult albatrosses were landing with a whoosh, bringing meals of slurrified seafood to their perpetually hungry offspring. When one alighted near the tents, Scofield and Moniz each picked up a shepherd's crook and crept toward it. The bird tried to take off, its wings stretching some six feet as it ran from Moniz. A swipe with the crook, a bleat of protest, and the albatross was apprehended, snagged by the neck.

Moniz cradled the bird, keeping a tight grip on its devilishly hooked bill, while Scofield taped a popsicle-size GPS logger—a tracking device—between its shoulders, spray-painted its snowy chest with a slash of blue for ease of recognition, and released it. "One down, 11 to go," Scofield said. He and Moniz were planning to stay three weeks on the Pyramid, and they hoped to deploy the devices on a dozen breeding adults to track their movements at sea.

Scofield, of New Zealand's Canterbury Museum and co-author of Albatrosses, Petrels and Shearwaters of the World , has been studying albatrosses for more than 20 years. To research these birds is to commit oneself to months at a time on the isolated, storm-lashed but utterly spectacular specks of land on which they breed: from the Crozet Islands in the Indian Ocean, to South Georgia in the South Atlantic, to Campbell Island and the Snares Islands in New Zealand. Scofield has visited most of them.

Studying albatrosses is also not without risks. In 1985, the yacht taking Scofield to Marion Island in the South Indian Ocean was rolled twice and dismasted, 700 miles south of South Africa. Jury-rigged, the yacht limped to its destination. Scofield and the crew stayed on Marion with other albatross researchers for five months (they had planned on only two days) while waiting for a ship to pick them up. Another time, during a ferocious storm in the Chathams, Scofield and his colleagues had to wear safety harnesses bolted to the rock as they slept in their tents, in case a wave washed over their campsite. Albatross eggs and even adult birds were bowled off their nests by the wind, and Scofield observed more than one parent try to push an egg back onto the nest with its bill—a challenge analogous to rolling a football up a flight of steps with your nose.

Scofield and other albatross researchers return year after year to their field studies knowing that albatrosses are one of the most threatened families of birds on earth. All but 2 of the 21 albatross species recognized by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature are described as vulnerable, endangered or, in the case of the Amsterdam and Chatham albatrosses, critically endangered. The scientists hope that the data they gather may save some species from extinction.

Albatrosses are among the largest seabirds. The "great albatrosses," the wandering and royal albatrosses, have the widest wingspans—ten feet or more—of any living bird. These are the birds of legend: the souls of drowned sailors, the harbinger of fair breezes and the metaphor for penance in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner: "Ah! well a-day! what evil looks / Had I from old and young! / Instead of the cross, the Albatross / About my neck was hung."

A wandering albatross is a "regal, feathery thing of unspotted whiteness," wrote Herman Melville. They look white in flight, but even the wanderers have a few darker feathers on their wings, and many of the smaller species have varying combinations of black, white, brown and gray plumage.

Albatrosses are masters of soaring flight, able to glide over vast tracts of ocean without flapping their wings. So fully have they adapted to their oceanic existence that they spend the first six or more years of their long lives (which last upwards of 50 years) without ever touching land. Most live in the Southern Hemisphere, the exceptions being the black-footed albatross of the Hawaiian archipelago and a few nearby islands; the short-tailed albatross, which breeds near Japan; the waved albatross of equatorial Galápagos; and the Laysan albatross of the North Pacific.

Everything about albatrosses underscores the difficulty of eking out an existence in their environment. Unlike penguins, which can hunt for extended periods underwater and dive to great depths, albatrosses can plunge into only the top few feet of the ocean, for squid and fish. The lengthy albatross "chickhood" is an adaptation to a patchy food supply: a slow-maturing chick needs food less often than a fast-maturing one. (Similarly, the prolonged adolescence—around 12 years in wandering albatrosses—is an extended education during which birds prospect the oceans, learning where and when to find food.) The chick's nutritional needs cannot be met by a single parent. Mate selection, therefore, is a critical decision, and is all about choosing a partner that can bring home the squid.

Jean-Claude Stahl of the Museum of New Zealand has studied courtship and pairing in southern Buller's albatrosses, which breed on the Snares Islands—a naturalist's El Dorado where penguins patter along forest paths, sea lions sleep in shady glades and myriad shearwaters blacken the evening sky. In Buller's albatrosses the search for a partner takes several years. It begins when adolescent birds are in their second year ashore, at about age 8. They spend time with potential mates in groups known as gams, the albatross equivalent of singles bars. In their third year ashore, males stake a claim to a nest site and females shop around, inspecting the various territory-holding males. "Females do the choosing, and their main criterion seems to be the number of days a male can spend ashore—presumably a sign of foraging ability," says Stahl.

Pairs finally form in the fourth year ashore. Albatross fidelity is legendary; in southern Buller's albatrosses, only 4 percent will choose new partners. In the fifth year, a pair may make its first breeding attempt. Breeding is a two-stage affair. "Females have to reach a sufficiently fat state to trigger the breeding feeling and return to the colony," says Paul Sagar of New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. "When they are back, the local food supply determines whether or not an egg is produced."

The breeding pair returns to the same nest year after year, adding a fresh layer of peat and vegetation until the pedestal becomes as tall as a top hat.

Because it takes so long for the birds to produce a chick, albatross populations are keenly vulnerable to threats on their breeding islands. Introduced predators such as rodents and feral cats—the islands have no native land mammals—pose a danger, especially to defenseless chicks, which are left alone for long periods while their parents shuttle back and forth from distant feeding grounds. In one of the most extreme examples of seabird predation, mice on Gough Island, in the South Atlantic, are decimating the populations of petrels and albatrosses that breed there, killing an estimated 1,000 Tristan albatross chicks a year.

Natural disasters also cause heavy losses. In 1985, storm surges washed over two royal albatross breeding islands in the Chathams, killing chicks and, even more problematic, removing much of the islands' scant soil and vegetation. With the albatrosses lacking nesting material in subsequent years, the breeding success rate dropped from 50 percent to 3 percent: the birds laid their eggs on bare rock, and most eggs were broken during incubation.

Yet the most pernicious threats to albatrosses today are not to chicks but to adult birds. Along with other seabirds, they are locked in a competitive battle with humankind for the food resources of the sea—and the birds are losing. This is not just because of the efficiency of modern fishing practices but because fishing equipment—hooks, nets and trawl wires—inflict a heavy toll of injury and death.

John Croxall, a seabird scientist with the British Antarctic Survey, has described the decrease in numbers in some albatross species as "catastrophic." Given the role of fisheries in their decline, he says, knowledge of the birds' distribution at sea and their foraging patterns is "critical to their conservation."

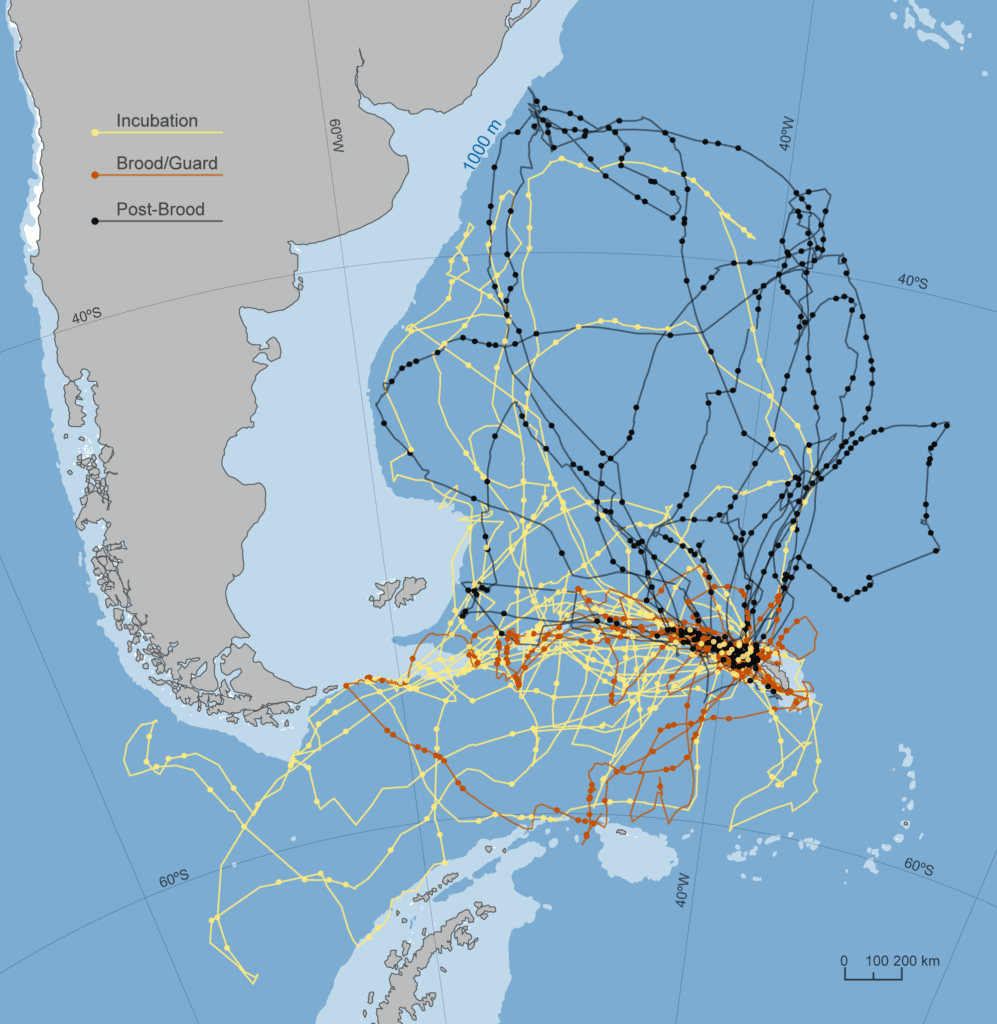

Over the past two decades, high-tech tracking devices such as the GPS loggers used by Scofield on the Pyramid have begun to fill in gaps in our knowledge about where albatrosses roam and where they are coming into lethal contact with fishing operations. Previously, when an albatross flew away from its breeding island, it virtually disappeared, its activities and whereabouts unknown. But now the lives of these birds are being revealed in all their unimagined complexity, stunning accomplishment and tragic vulnerability.

GPS loggers can give a bird's position to within a few yards. Some loggers also have temperature sensors. By attaching them to the legs of their study birds, scientists can tell when the birds are flying and when they are resting or feeding on the sea, because the water is generally cooler than the air.

As nifty as GPS loggers are, there is a snag: you have to get them back—an outcome by no means guaranteed. Among the larger albatrosses, chick-feeding forays can last ten days or more and encompass thousands of square miles of ocean. Lots of things can go wrong on these outings, particularly in and around commercial fishing grounds, where birds die by the thousands, done in by hooks, nets and the lines that haul them. And because albatrosses have to struggle to take flight in the absence of a breeze, birds may be becalmed on the sea.

On the Pyramid, Scofield was reasonably confident of retrieving his GPS devices. The Chatham albatrosses' feeding forays tend to be relatively short—only a few days—and there was little chance of his birds becoming becalmed in the windy latitudes they inhabit, meridians known to mariners as the Roaring Forties, Furious Fifties and Screaming Sixties. More worrisome to Scofield was the knowledge that the area adjacent to the Chatham Islands—known as the Chatham Rise—is one of New Zealand's richest commercial fishing grounds, replete with orange roughy and several other deep water species. Albatrosses, too, know where fish are found, and the birds sample the most productive fishing areas much as human shoppers make the rounds of favorite stores.

And what expeditions these birds make! From mollymawks, as the smaller species are known, to the great albatrosses, these super-soarers cover tens of thousands of miles in their oceanic forays. Individuals of some species circumnavigate the globe, covering 500 miles a day at sustained speeds of 50 miles per hour.

And then they somehow find their way home—even when home is an outpost in the ocean like the Pyramid, not much bigger than an aircraft carrier. At the start of their breeding season, albatrosses have been tracked making almost ruler-straight trips from distant foraging areas to their nests. Because the birds maintain their course day and night, in cloudy weather and clear, scientists believe they use some kind of magnetic reckoning to fix their position relative to the earth's magnetic field.

The birds also seem able to predict the weather. Southern Buller's albatrosses were found to fly northwest if a low-pressure system, which produces westerly winds, was imminent, and northeast if an easterly wind-producing high-pressure system prevailed. The birds typically chose their direction 24 hours prior to the arrival of the system, suggesting they can respond to barometric cues.

In his autopsy room in Wellington, ornithologist Christopher Robertson slit open a plastic bag containing a white-capped albatross. The swan-sized carcass had been thawing for several days. Along with dozens of other seabirds in Robertson's freezers, this one had been collected at sea for the government's fisheries science program.

Robertson carefully unfolded the bird's wings—wings that would have carried it halfway around the world, between its breeding grounds in New Zealand's Auckland Islands and its feeding grounds in South African seas.

The albatross bore a raw wound at the elbow. Its feathers and skin had been rasped down to bare bone, presumably by the thick steel wires—called warps—that pull a trawl net. Of the 4,000 albatrosses and other seabirds Robertson's group has autopsied over nine years, nearly half have been killed by trawl fisheries, which use giant sock-shaped nets towed at depths of a quarter mile to capture 40 tons of fish in a single haul. (Albatrosses and other large, soaring birds tend to die as a result of collisions with the warps, while smaller, more agile fliers such as petrels and shearwaters are more likely to get ensnared in nets—to be crushed or drowned—while feeding.) The finding has surprised the fishing industry and conservation groups, which have considered longline fishing—in which thousands of baited hooks are fed out behind the fishing vessel—a greater threat to seabirds.

There are no reliable figures for the number of birds killed per year through contact with commercial fishing operations, but estimates for the Southern Ocean are in the tens of thousands. Vessels in well-regulated fisheries are required to minimize their impact on seabirds and report any accidental deaths, but there is a large shadow fleet of illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) vessels operating outside the regulations, answering to no one.

Many New Zealand fishers have adopted ingenious methods to reduce injuring and killing seabirds—or attracting them to boats in the first place (see sidebar, opposite). However, there is some evidence to suggest that fisheries may benefit albatross populations: a ready supply of discarded fish reduces competition for food between and within albatross species and provides an alternative food source to predatory birds such as skua, which often attack albatross chicks. Sagar and Stahl's research in the Snares Islands suggests that the free lunch boosts the number of chicks that fledge in a given year. They found that 70 percent of feedings brought by adult birds to their chicks contained discards from nearby fisheries.

Does this mean that fishing is a net benefit to seabird populations? Should the industry be given "a conservation award for the thousands of seabirds it supports," as one fisheries consultant gamely suggested to me?

Not at all, says Stahl. In albatrosses—long-lived, slow-maturing species that produce a single chick every one to two years—the long-term negative impact of adult death far outweighs the short-term benefit of chick survival. It may take three, four or even five successful chick rearings to compensate for the death of just one parent, says Stahl. He calculates that "even small increases in adult mortality can wipe out the benefit of tons of discards fed to chicks."

Although Scofield's tracking of Chatham albatrosses shows that they, too, frequent the same fishing grounds as deep-sea trawlers, not enough work has been done to compare the benefits of chick survival with the costs of adult deaths from fishing vessels. "We don't know the degree to which we're propping them up," says Scofield.

One albatross population that has unashamedly been propped up is the colony of endangered northern royal albatrosses at Taiaroa Head, near the city of Dunedin, on New Zealand's South Island. Taiaroa Head is one of the only places in the world where a visitor can get close to great albatrosses. The colony is tiny, with only 140 individuals, and the breeding effort is managed assiduously—"lovingly" would not be too strong a word.

Royal albatross chicks are nest-bound for nine months. Providing meals for these chicks is so demanding that the parents take a year off before breeding again. Lyndon Perriman, the senior ranger, described to me some of the ingenious techniques used to maximize reproductive success.

"If a bird has been sitting on an egg for 10 days and has not been relieved by its partner, we put the egg in an incubator and give the bird a fiberglass replica to sit on," he said. "If the partner hasn't returned by day 15, we start to supplementary-feed the sitting bird, giving it salmon smolts. But we prefer not to interfere. It could simply be that the partner has hit a patch of calm weather somewhere and is struggling to get back. But at day 20 it's pretty clear the partner isn't coming back, and a chick with only one parent won't survive, so we take the fiberglass egg away, and the bird figures out that breeding for that year is over."

"We also take the egg away from first-time breeders, because they tend to be clumsy with their big webbed feet and are likely to break the egg," Perriman said. "We'll either give the real egg to a pair that's sitting on a dud—broken or infertile or whatever—or keep it in the incubator until it hatches." Breeding success is 72 percent, compared with an estimated 33 percent had humans not assisted.

Adult birds at Taiaroa have died of heat exhaustion, so rangers turn on sprinklers during hot, still days. There was no danger of the birds overheating when I visited, with raindrops spattering the tinted windows of the observatory. I picked up a toy albatross, a life-size replica of a fully grown chick. It was surprisingly heavy, weighted to match the real thing: 20 pounds. Fledglings of most albatross species weigh 50 percent more than adults. They need the extra fat to tide them over when they are learning to feed themselves.

A tour group crowded against the observatory's viewing window. A few yards away an albatross was hunkered down on its nest, protecting its chick from a gale then whipping the hillside. A voice exclaimed: "Look! There she goes!" A chorus of admiring gasps and sighs followed as the bird spread its "vast archangel wings"—Melville's majestic description in Moby-Dick —and soared past the lighthouse on its way out to sea.

Coleridge never saw an albatross, but his Rime introduced a legend. Redemption for the poem's woebegone mariner comes when he embraces all life, no matter how lowly. The moral of the tale, says the mariner to his listener, is this: "He prayeth well, who loveth well / Both man, and bird, and beast." It is a message still worth heeding.

Kennedy Warne, a writer and photographer from Auckland, New Zealand, wrote about Carl Linnaeus in the May 2007 issue.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Albatross: Lifetime at Sea

When hearing the word albatross , some might think of a really good round of golf (three under par). Like scoring an albatross in golf, sighting a long-lived master of flight in the Albatross family is a special treat. Chances are you haven’t seen one in person, but to put a name to this special type of seabird opens the door to their world.

Masters of Efficient Flight

There are 22 species of albatross that share the gift of efficient long-distance gliding flight. They are famously recognized by their lengthy wingspans with the Wandering Albatross holding the record at nearly 12 feet. These remarkable wingspans are vital for a lifetime at sea. With the help of air currents and temperature changes, these wings are able to provide enormous amounts of lift; albatross can spend hours in flight without rest or a single flap. Their flying abilities allow albatross to journey thousands of miles across open oceans.

Many people view their elders and put some thought into what those eyes have seen over a lifetime; what experiences that person has had, or wisdom and knowledge they’ve picked up through the years. These same thoughts could be applied when looking into the eyes of an albatross. Albatross can live decades and spend most of their long lives at sea. When an albatross encounters a fishing vessel or is counted on the breeding grounds, these birds may be decades older than the people studying these magnificent gliders. It could be safe to assume that an adult albatross knows their way around the seas better than the career fisherman or woman they are following.

Throughout history, humans have shared the seas with these seabirds. Many sailors recognize that albatross will follow their vessels, looking for an easy meal. Interactions, intentional or accidental, have resulted in the near-extinction of some species of albatross. Conservation efforts have been put in place by multi-nation partnerships, which have contributed to success in rising numbers of albatross seen in the Pacific Ocean.

Albatrosses in Alaska

Alaska is within the range of Short-tailed, Laysan and Black-footed Albatross which are commonly seen at-sea. These birds take to land to breed on ocean islands, including the world’s largest albatross colony on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge .

Short-tailed Albatrosses

This endangered species breeds primarily on two remote islands in the western Pacific with the majority (~85%) breeding on Torishima, Japan (an active volcano in the Izu Island Group, northwest of Taiwan). From 2008 to 2012 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Japanese partners at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology worked together to establish a third breeding colony by translocating chicks from Torishima to a historic breeding location on the island of Mukojima. Recently, short-tailed albatrosses have also successfully bred on Midway Atoll.

Short-tailed Albatrosses generally head toward their feeding grounds around April and May, but have been known to make the long journey into Alaskan waters just to feed and return to their nest. They have been seen feeding along shelf breaks in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, along the Aleutian Islands, and southeast Alaska. They also occur along the Pacific coasts of Canada and the United States including waters along Washington, Oregon, and California.

Short-tailed Albatross follow fishing vessels and are sometimes hooked or entangled in longline fishing gear and drowned. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been working with the commercial fishing industry, Washington Sea Grant, and National Marine Fisheries Service to minimize take of this endangered seabird. Through this collaborative conservation effort, a type of seabird avoidance technology called “streamerlines” was developed to reduce the bycatch of albatrosses.

Streamerlines create a visual barrier that keeps seabirds away from the baited hooks. In Alaska, streamerlines deployed on fishing vessels has led to a major reduction in the bycatch of albatrosses. Fishermen who have used streamerlines to ward off seabirds say there is also a financial benefit: the streamer lines keep seabirds from swiping their bait, saving them money in the long run.

From near extinction at the turn of the 20th century, to being listed as endangered throughout its range in 2000, the population of short-tailed albatross continues to grow with a current estimate of 7,365 individuals and a population growth rate of 8.9%. This is something to celebrate.

Black-footed Albatross

Unlike the Short-Tailed Albatross, the Black-footed Albatross is not currently listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Black-Footed Albatross are only found in the Pacific Ocean with breeding populations located on the Hawaiian and Japanese islands. Breeding occurs from late fall to mid-summer and involves a colorful display of head bobs, wing flaps, and foot stomps. If you have not witnessed a Black-Footed Albatross mating dance, that should be your next internet search as it is a sight to see. Black-footed Albatross, like other albatross species, are thought to mate for life but will find a new mate if their partner disappears or passes away.

After breeding these seabirds can be seen in the North Pacific where they feed on fish, squid, and crustaceans. Like other albatross species, these birds can also be seen tailing ships for easy meals and have sometimes become victims to accidental entanglement into fishing equipment at sea. They too have benefited from Short-tailed Albatross conservation efforts via reduced accidental bycatch.

Laysan Albatross

One of the easier identifiable albatross seen in the seas surrounding Alaska is the Layson Albatross. These seabirds are generally smaller in size when compared to other albatross sharing its range, but is most noticeably different by its white belly and head that is often referred to as “gull-like”. Add in a gray-brown wings with white undersides and a dark tail and you’ve got yourself a Laysan Albatross.

Laysan Albatross are more commonly seen out at sea away from North American shores. 97.7% of the population call the northwestern Hawaiian Islands home during the breeding season (late fall to mid-summer) before moving north through the Pacific eventually making their way to Alaskan fishing regions. For those of you traveling through the southwest, don’t be too surprised to see one of these seabirds overhead, they’ve been known to wander inland during their migration north.

These seabird’s have a diet consisting of squid, fish, crustaceans and flying fish eggs. They primarily feed at night. In regards to fishing bycatch, this could be beneficial or negative depending on fishing operation times and the effectiveness and use of mitigating equipment such as streamers at night. Like other albatross, Laysan Albatross sometimes fall victim to fishing equipment such as baited lines and driftnets. They have also benefited from conservation efforts to reduce seabird bycatch during fishing operations. Fishing bycatch, however, is not the only issue that Laysans and other sea life must face, plastics and debris scattered through the world’s oceans are also part of this seabird’s diet, which in many cases can prove to be fatal.

A note on plastic pollution: Be Part of the Solution

Like many birds, albatross can fall victim to plastic pollution that makes its way to sea. Because they feed along the surface on squid, krill, fish eggs and other items, albatrosses often accidentally swallow floating plastic. This becomes a problem when their stomach becomes impacted and full of plastic resulting in lack of nutrition from natural prey. On the breeding grounds, baby albatrosses suffer from a diet of this plastic trash brought in by their parents from the ocean. Parents feed their chicks by regurgitating what they’ve found out at sea. It’s estimated that adult albatrosses unwittingly bring back thousands of pounds of marine debris back to places like Midway atoll every year. Dead chicks that have starved due to plastic ingestion can be found on the breeding grounds and are testament to this global problem.One way you can make a small difference is picking up plastic trash before it makes its way into rivers and eventually to sea.

You can help albatross and all seabirds by recycling as much or your plastic as possible, saying ‘no’ to single use plastic, using a re-usable water bottle, bringing re-usable bags to the grocery store. We can all do our part to help make the oceans safe for all birds and ensure that the graceful flight of the albatross can be witnessed by generations to come.

In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it. Compiled by Kristopher Pacheco, Alaska Digital Media Assistant for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, with Katrina Liebich and staff from Migratory Birds Management and Ecological Services. For this article and others, follow us on Medium .

Recreational Activities

Related stories.

Latest Stories

You are exiting the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website

You are being directed to

We do not guarantee that the websites we link to comply with Section 508 (Accessibility Requirements) of the Rehabilitation Act. Links also do not constitute endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Text account

- Data table and detailed info

- Distribution map

- Reference and further resources

Family: Diomedeidae (Albatrosses) Family: Diomedeidae (Albatrosses) -->

Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

Recommended citation BirdLife International (2024) Species factsheet: Diomedea exulans . Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/wandering-albatross-diomedea-exulans on 28/04/2024. Recommended citation for factsheets for more than one species: BirdLife International (2024) IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org on 28/04/2024.

Animal Diversity Web

- About Animal Names

- Educational Resources

- Special Collections

- Browse Animalia

More Information

Additional information.

- Encyclopedia of Life

Diomedea exulans wandering albatross

Geographic Range

Wandering albatrosses are found almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere, although occasional sightings just north of the Equator have been reported. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

There is some disagreement over how many subspecies of wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) there are, and whether they should be considered separate species. Most subspecies of Diomedea exulans are difficult to tell apart, especially as juveniles, but DNA analyses have shown that significant differences exist. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Diomedea exulans exulans breeds on South Georgia, Prince Edward, Marion, Crozet, Kerguelen, and Macquarie islands. Diomedea exulans dabbenena occurs on Gough and Inaccessible islands, ranging over the Atlantic Ocean to western coastal Africa. Diomedea exulans antipodensis is found primarily on the Antipodes of New Zealand, and ranges at sea from Chile to eastern Australia. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is found only on Amsterdam Island and the surrounding seas. Other subspecies names that have become obsolete include Diomedea exulans gibsoni , now commonly considered part of D. e. antipodensis , and Diomedea exulans chionoptera , considered part of D. e. exulans . ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Biogeographic Regions

Wandering albatrosses breed on several subantarctic islands, which are characterized by peat soils, tussock grass, sedges, mosses, and shrubs. Wandering albatrosses nest in sheltered areas on plateaus, ridges, plains, or valleys.

Outside of the breeding season, wandering albatrosses are found only in the open ocean, where food is abundant. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Habitat Regions

- terrestrial

- saltwater or marine

- Terrestrial Biomes

- savanna or grassland

- Aquatic Biomes

Physical Description

All subspecies of wandering albatrosses have extremely long wingspans (averaging just over 3 meters), white underwing coverts, and pink bills. Adult body plumage ranges from pure white to dark brown, and the wings range from being entirely blackish to a combination of black with white coverts and scapulars. They are distinguished from the closely related royal albatross by their white eyelids, pink bill color, lack of black on the maxilla, and head and body shape. On average, males have longer bills, tarsi, tails, and wings than females. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Juveniles of all subspecies are very much alike; they have chocolate-brown plumage with a white face and black wings. As individuals age, most become progressively whiter with each molt, starting with the back. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

D. e. exulans averages larger than other recognized subspecies, and is the only taxon that achieves fully white body plumage, and this only in males. Although females do not become pure white, they can still be distinguished from other subspecies by color alone. Adults also have mostly white coverts, with black only on the primaries and secondaries. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. amsterdamensis have dark brown plumage with white faces and black crowns, and are distinguished from juveniles by their white bellies and throats. In addition to their black tails, they also have a black stripe along the cutting edge of the maxilla, a character otherwise found in D. epomophora but not other forms of D. exulans . Males and females are similar in plumage. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. antipodensis display sexual dimorphism in plumage, with older males appearing white with some brown splotching, while adult females have mostly brown underparts and a white face. Both sexes also have a brown breast band. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

With age, D. e. dabbenena gradually attains white plumage, although it never becomes as white as male D. e. exulans . The wing coverts also appear mostly black, although there may be white patches. Females have more brown splotches than males, and have less white in their wing coverts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Other Physical Features

- endothermic

- homoiothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- sexes alike

- male larger

- sexes colored or patterned differently

- Average mass 8130 g 286.52 oz AnAge

- Range length 1.1 to 1.35 m 3.61 to 4.43 ft

- Range wingspan 2.5 to 3.5 m 8.20 to 11.48 ft

- Average wingspan 3.1 m 10.17 ft

- Average basal metabolic rate 20.3649 W AnAge

Reproduction

Wandering albatrosses have a biennial breeding cycle, and pairs with chicks from the previous season co-exist in colonies with mating and incubating pairs. Pairs unsuccessful in one year may try to mate again in the same year or the next one, but their chances of successfully rearing young are low. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After foraging at sea, males arrive first at the same breeding site every year within days of each other. They locate and reuse old nests or sometimes create new ones. Females arrive later, over the course of a few weeks. Wandering albatrosses have a monogamous mating strategy, forming pair bonds for life. Females may bond temporarily with other males if their partner and nest are not readily visible. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Mating System

Copulation occurs in the austral summer, usually around December (February for D. e. amsterdamensis ). Rape and extra-pair copulations are frequent, despite their monogamous mating strategy. Pairs nest on slopes or valleys, usually in the cover of grasses or shrubs. Nests are depressions lined with grass, twigs, and soil. A single egg is laid and, if incubation or rearing fails, pairs usually wait until the following year to try again. Both parents incubate eggs, which takes about 78 days on average. Although females take the first shift, males are eager to take over incubation and may forcefully push females off the egg. Untended eggs are in danger of predation by skuas ( Stercorarius ) and sheathbills ( Chionis ). ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After the chick hatches, they are brooded for about 4 to 6 weeks until they can be left alone at the nest. Males and females alternate foraging at sea. Following the brooding period, both parents leave the chick by itself while they forage. The chicks are entirely dependent on their parents for food for 9 to 10 months, and may wait weeks for them to return. Chicks are entirely independent once they fledge. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Some individuals may reach sexual maturity by age 6. Immature, non-breeding individuals will return to the breeding site. Group displays are common among non-breeding adults, but most breeding adults do not participate. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- Breeding interval Breeding occurs biennially, possibly annually if the previous season's attempt fails.

- Breeding season Breeding occurs from December through March.

- Average eggs per season 1

- Range time to hatching 74 to 85 days

- Range fledging age 7 to 10 months

- Range time to independence 7 to 10 months

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 10 years

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 10 years

Males choose the nesting territory, and stay at the nest site more than females before incubation. Parents alternate during incubation, and later during brooding and feeding once the chick is old enough to be left alone at the nest. Although there is generally equal parental investment, males will tend to invest more as the chick nears fledging. Occasionally, a single parent may successfully rear its chick. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Parental Investment

- provisioning

Lifespan/Longevity

Wandering albatrosses are long-lived. An individual nicknamed "Grandma" was recorded to live over 60 years in New Zealand. Due to the late onset of maturity, with the average age at first breeding about 10 years, such longevity is not unexpected. However, there is fairly high chick mortality, ranging from 30 to 75%. Their slow breeding cycle and late onset of maturity make wandering albatrosses highly susceptible to population declines when adults are caught as bycatch in fishing nets. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Range lifespan Status: wild 60 (high) years

- Average lifespan Status: wild 415 months Bird Banding Laboratory

While foraging at sea, wandering albatrosses travel in small groups. Large feeding frenzies may occur around fishing boats. Individuals may travel thousands of kilometers away from their breeding grounds, even occasionally crossing the equator.

During the breeding season, Wandering albatrosses are gregarious and displays are common (see “Communication and Perception” section, below). Vocalizations and displays occur during mating or territorial defense. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Behaviors

- territorial

- Average territory size 1 m^2

Wandering albatrosses defend small nesting territories, otherwise the range within which they travel is many thousands of square kilometers. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Communication and Perception

Displays and vocalizations are common when defending territory or mating. They include croaks, bill-clapping, bill-touching, skypointing, trumpeting, head-shaking, the "ecstatic" gesture, and "the gawky-look". Individuals may also vocalize when fighting over food. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Communication Channels

- Perception Channels

Food Habits

Wandering albatrosses primarily eat fish, such as toothfish ( Dissostichus ), squids, other cephalopods, and occasional crustaceans. The primary method of foraging is by surface-seizing, but they have the ability to plunge and dive up to 1 meter. They will sometimes follow fishing boats and feed on catches with other Procellariiformes , which they usually outcompete because of their size. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Primary Diet

- molluscivore

- Animal Foods

- aquatic crustaceans

Although humans formerly hunted wandering albatrosses as food, adults currently have no predators. Their large size, sharp bill, and occasionally aggressive behavior make them undesirable opponents. However, some are inadvertently caught during large-scale fishing operations.

Chicks and eggs, on the other hand, are susceptible to predation from skuas and sheathbills, and formerly were harvested by humans as well. Eggs that fall out of nests or are unattended are quickly preyed upon. Nests are frequently sheltered with plant material to make them less conspicuous. Small chicks that are still in the brooding stage are easy targets for large carnivorous seabirds. Introduced predators, including mice, pigs, cats, rats, and goats are also known to eat eggs and chicks. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- skuas ( Stercorariidae )

- sheathbills ( Chionis )

- domestic cats ( Felis silvestris )

- introduced pigs ( Sus scrofa )

- introduced goats ( Capra hircus )

- introduced rats ( Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus )

- introduced mice ( Mus musculus )

Ecosystem Roles

Wandering albatrosses are predators, feeding on fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. They are known for their ability to compete with other seabirds for food, particularly near fishing boats. Although adult birds, their eggs, and their chicks were formerly a source of food to humans, such practices have been stopped. ( IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Wandering albatrosses have extraordinary morphology, with perhaps the longest wingspan of any bird. Their enormous size also makes them popular in ecotourism excursions, especially for birders. Declining population numbers also mean increased conservation efforts. Their relative tameness towards humans makes them ideal for research and study. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Positive Impacts

- research and education

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Wandering albatrosses, along with other seabirds, follow fishing boats to take advantage of helpless fish and are reputed to reduce economic output from these fisheries. Albatrosses also become incidental bycatch, hampering conservation efforts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Conservation Status

Diomedea exulans exulans and Diomedea exulans antipodensis are listed by the IUCN Red list and Birdlife International as being vulnerable; Diomedea exulans dabbenena is listed as endangered, and Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered.

All subspecies of Diomedea exulans are highly vulnerable to becoming bycatch of commercial fisheries, and population declines are mostly attributed to this. Introduced predators such as feral cats , pigs , goats , and rats on various islands leads to high mortality rates of chicks and eggs. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered due to introduced predators, risk of becoming bycatch, small population size, threat of chick mortality by disease, and loss of habitat to cattle farming.

Some conservation measures that have been taken include removal of introduced predators from islands, listing breeding habitats as World Heritage Sites, fishery relocation, and population monitoring. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- IUCN Red List Vulnerable More information

- US Migratory Bird Act No special status

- US Federal List No special status

- CITES No special status

Contributors

Tanya Dewey (editor), Animal Diversity Web.

Lauren Scopel (author), Michigan State University, Pamela Rasmussen (editor, instructor), Michigan State University.

the body of water between Africa, Europe, the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), and the western hemisphere. It is the second largest ocean in the world after the Pacific Ocean.

body of water between the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), Australia, Asia, and the western hemisphere. This is the world's largest ocean, covering about 28% of the world's surface.

uses sound to communicate

young are born in a relatively underdeveloped state; they are unable to feed or care for themselves or locomote independently for a period of time after birth/hatching. In birds, naked and helpless after hatching.

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

an animal that mainly eats meat

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

the nearshore aquatic habitats near a coast, or shoreline.

used loosely to describe any group of organisms living together or in close proximity to each other - for example nesting shorebirds that live in large colonies. More specifically refers to a group of organisms in which members act as specialized subunits (a continuous, modular society) - as in clonal organisms.

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

humans benefit economically by promoting tourism that focuses on the appreciation of natural areas or animals. Ecotourism implies that there are existing programs that profit from the appreciation of natural areas or animals.

animals that use metabolically generated heat to regulate body temperature independently of ambient temperature. Endothermy is a synapomorphy of the Mammalia, although it may have arisen in a (now extinct) synapsid ancestor; the fossil record does not distinguish these possibilities. Convergent in birds.

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

eats mollusks, members of Phylum Mollusca

Having one mate at a time.

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

generally wanders from place to place, usually within a well-defined range.

islands that are not part of continental shelf areas, they are not, and have never been, connected to a continental land mass, most typically these are volcanic islands.

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

An aquatic biome consisting of the open ocean, far from land, does not include sea bottom (benthic zone).

an animal that mainly eats fish

the regions of the earth that surround the north and south poles, from the north pole to 60 degrees north and from the south pole to 60 degrees south.

mainly lives in oceans, seas, or other bodies of salt water.

breeding is confined to a particular season

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

associates with others of its species; forms social groups.

uses touch to communicate

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

Living on the ground.

defends an area within the home range, occupied by a single animals or group of animals of the same species and held through overt defense, display, or advertisement

A terrestrial biome. Savannas are grasslands with scattered individual trees that do not form a closed canopy. Extensive savannas are found in parts of subtropical and tropical Africa and South America, and in Australia.

A grassland with scattered trees or scattered clumps of trees, a type of community intermediate between grassland and forest. See also Tropical savanna and grassland biome.

A terrestrial biome found in temperate latitudes (>23.5° N or S latitude). Vegetation is made up mostly of grasses, the height and species diversity of which depend largely on the amount of moisture available. Fire and grazing are important in the long-term maintenance of grasslands.

uses sight to communicate

Birdlife International, 2006. "Species factsheets" (On-line). Accessed November 07, 2006 at http://www.birdlife.org .

IUCN, 2006. "2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species" (On-line). Accessed November 06, 2006 at http://www.iucnredlist.org .

Shirihai, H. 2002. The Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife . New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tickell, W. 1968. Biology of Great Albatrosses. Pp. 1-53 in Antarctic Bird Studies . Baltimore: Horn-Schafer.

The Animal Diversity Web team is excited to announce ADW Pocket Guides!

Read more...

Search in feature Taxon Information Contributor Galleries Topics Classification

- Explore Data @ Quaardvark

- Search Guide

Navigation Links

Classification.

- Kingdom Animalia animals Animalia: information (1) Animalia: pictures (22861) Animalia: specimens (7109) Animalia: sounds (722) Animalia: maps (42)

- Phylum Chordata chordates Chordata: information (1) Chordata: pictures (15213) Chordata: specimens (6829) Chordata: sounds (709)

- Subphylum Vertebrata vertebrates Vertebrata: information (1) Vertebrata: pictures (15168) Vertebrata: specimens (6827) Vertebrata: sounds (709)

- Class Aves birds Aves: information (1) Aves: pictures (7311) Aves: specimens (153) Aves: sounds (676)

- Order Procellariiformes tube-nosed seabirds Procellariiformes: pictures (48) Procellariiformes: specimens (15)

- Family Diomedeidae albatrosses Diomedeidae: pictures (27) Diomedeidae: specimens (6)

- Genus Diomedea royal and wandering albatrosses Diomedea: pictures (5) Diomedea: specimens (4)

- Species Diomedea exulans wandering albatross Diomedea exulans: information (1) Diomedea exulans: pictures (3)

To cite this page: Scopel, L. 2007. "Diomedea exulans" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 28, 2024 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Diomedea_exulans/

Disclaimer: The Animal Diversity Web is an educational resource written largely by and for college students . ADW doesn't cover all species in the world, nor does it include all the latest scientific information about organisms we describe. Though we edit our accounts for accuracy, we cannot guarantee all information in those accounts. While ADW staff and contributors provide references to books and websites that we believe are reputable, we cannot necessarily endorse the contents of references beyond our control.

- U-M Gateway | U-M Museum of Zoology

- U-M Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

- © 2020 Regents of the University of Michigan

- Report Error / Comment

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Grants DRL 0089283, DRL 0628151, DUE 0633095, DRL 0918590, and DUE 1122742. Additional support has come from the Marisla Foundation, UM College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, Museum of Zoology, and Information and Technology Services.

The ADW Team gratefully acknowledges their support.

Fact Animal

Facts About Animals

Wandering Albatross Facts

Wandering albatross profile.

In 1961, Dion and the Del Satins had a song from the perspective of an albatross. It wasn’t accurate on many counts, but it did get one thing right: they get around.

The Diomedea exulans, more commonly known as the wandering albatross is perhaps the most accomplished wanderer of any animal, with routine voyages of hundreds of kilometres per day on record-breaking wings.

They are a large seabird with a circumpolar range in the Southern Ocean, and sometimes known as snowy albatross, white-winged albatross or goonie.

Wandering Albatross Facts Overview

The wandering albatross breeds on islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, such as South Georgia Island, Crozet Islands, Prince Edward Island and others.

They spend most of their life in flight , and land only to breed and feed.

These are phenomenal birds, capable of surviving some of the harshest weather conditions even at the most vulnerable stages of their development.

They are slow to reproduce, spending extra time to develop into one of the biggest and most specialised animals in the air.

Sadly, this is what makes them vulnerable to population declines, and longline fishing vessels are responsible for many adult deaths.

Interesting Wandering Albatross Facts

1. they can travel 120k km (75k) miles in a year.

The Wandering albatross might be the most wide-ranging of all foraging sea birds, and maybe of all animals. They’ve been tracked over 15,000 km in a single foraging trip, capable of speeds of up to 80 kmph and distances of over 900 km per day. 1

2. They’re monogamous (mostly)

This goes against the entire theme of the Del Satins song and is probably why it’s no longer used as a learning aid in the zoological curriculum.

Contrary to the promiscuous subject of the ‘60s hit, the Wandering Albatrosses mate for life and are (on average) monogamous.

When breeding, they take on incubation shifts, and it’s during these periods when the wanderer goes out on their epic voyages to return with food for their family.

Still, there’s an element of personal preference when it comes to breeding.

Most females will take a year or two off after the long and arduous task of reproduction. During this time the parents will go their separate ways, only to reunite when the time is right.

In these periods, some females will take on a temporary mate, so they can squeeze out one more chick before reuniting with their permanent nesting partner. 2

3. Wandering albatross are active in moonlight

When on these journeys, the albatross is almost constantly active. During the day they spend the entire time in the air, and while they don’t cover much distance at night, they were still recorded almost constantly moving – never stopping for more than 1.6h in the dark.

They appear to travel more on moonlit nights than on darker ones.

All of this data comes from satellite trackers attached to some birds, which are always going to skew the results.

Flying birds are optimised for weight, and trackers add to this weight, so there’s necessarily a negative effect on the individual’s fitness when lumbering them with a tracker.

Still, these subjects were able to outlast the trackers’ batteries on many occasions, and it’s safe to assume they’re capable of even more than we can realistically measure!

4. They have the largest wingspan of any bird in the world

One advantage that an albatross has over, say, a pigeon, when it comes to carrying a researcher’s hardware, is that it doesn’t need to flap much.

The albatross is the bird with the longest wingspan of any flying animal – growing up to 3.2 m (10.5 ft), and these wings are meticulously adapted for soaring.

The Guiness Book of Records claims the largest wingspan of any living species of bird was a wandering albatross with a wingspan of 3.63m (11 ft 11) caught in 1965 by scientists on the Antarctic research ship USNS Eltanin in the Tasman Sea.

Research has suggested that these wings function best against slight headwinds, and act like the sails of a boat, allowing the bird to cover more ground by “tacking”, like a sailboat: zig-zagging across the angle of the wind to make forward progress into it. 3

5. Fat chicks

As mentioned, these voyages are usually a result of foraging trips for their chicks.