You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Travelers' Diarrhea

Español

Travelers' diarrhea is the most common travel-related illness. It can occur anywhere, but the highest-risk destinations are in Asia (except for Japan and South Korea) as well as the Middle East, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America.

In otherwise healthy adults, diarrhea is rarely serious or life-threatening, but it can make a trip very unpleasant.

You can take steps to avoid travelers’ diarrhea

- Choose food and drinks carefully Eat only foods that are cooked and served hot. Avoid food that has been sitting on a buffet. Eat raw fruits and vegetables only if you have washed them in clean water or peeled them. Only drink beverages from factory-sealed containers, and avoid ice because it may have been made from unclean water.

- Wash your hands Wash your hands often with soap and water, especially after using the bathroom and before eating. If soap and water aren’t available, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer. In general, it’s a good idea to keep your hands away from your mouth.

Learn some ways to treat travelers’ diarrhea

- Drink lots of fluids If you get diarrhea, drink lots of fluids to stay hydrated. In serious cases of travelers’ diarrhea, oral rehydration solution—available online or in pharmacies in developing countries—can be used for fluid replacements.

- Take over-the-counter drugs Several drugs, such as loperamide, can be bought over-the-counter to treat the symptoms of diarrhea. These drugs decrease the frequency and urgency of needing to use the bathroom, and may make it easier for you to ride on a bus or airplane while waiting for an antibiotic to take effect.

- Only take antibiotics if needed Your doctor may give you antibiotics to treat travelers’ diarrhea, but consider using them only for severe cases. If you take antibiotics, take them exactly as your doctor instructs. If severe diarrhea develops soon after you return from your trip, see a doctor and ask for stool tests so you can find out which antibiotic will work for you.

More Information

- Travelers’ Diarrhea- CDC Yellow Book

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

The treatment and prevention of travelers' diarrhea are discussed here. The epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of travelers' diarrhea are discussed separately. (See "Travelers' diarrhea: Epidemiology, microbiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis" .)

Clinical approach — Management of travelers’ diarrhea depends on the severity of illness. Fluid replacement is an essential component of treatment for all cases of travelers’ diarrhea. Most cases are self-limited and resolve on their own within three to five days of treatment with fluid replacement only. Antimotility agents can provide symptomatic relief but should not be used when bloody diarrhea is present. Antimicrobial therapy shortens the disease duration, but the benefit of antibiotics must be weighed against potential risks, including adverse effects and selection for resistant bacteria. These issues are discussed in the sections that follow.

When to seek care — Travelers from resource-rich settings who develop diarrhea while traveling to resource-limited settings generally can treat themselves rather than seek medical advice while traveling. However, medical evaluation may be warranted in patients who develop high fever, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, or vomiting. Otherwise, for most patients while traveling or after returning home, medical consultation is generally not warranted unless symptoms persist for 10 to 14 days.

Fluid replacement — The primary and most important treatment of travelers' (or any other) diarrhea is fluid replacement, since the most significant complication of diarrhea is volume depletion [ 11,12 ]. The approach to fluid replacement depends on the severity of the diarrhea and volume depletion. Travelers can use the amount of urine passed as a general guide to their level of volume depletion. If they are urinating regularly, even if the color is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely mild. If there is a paucity of urine and that small amount is dark yellow, the diarrhea and volume depletion are likely more severe.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

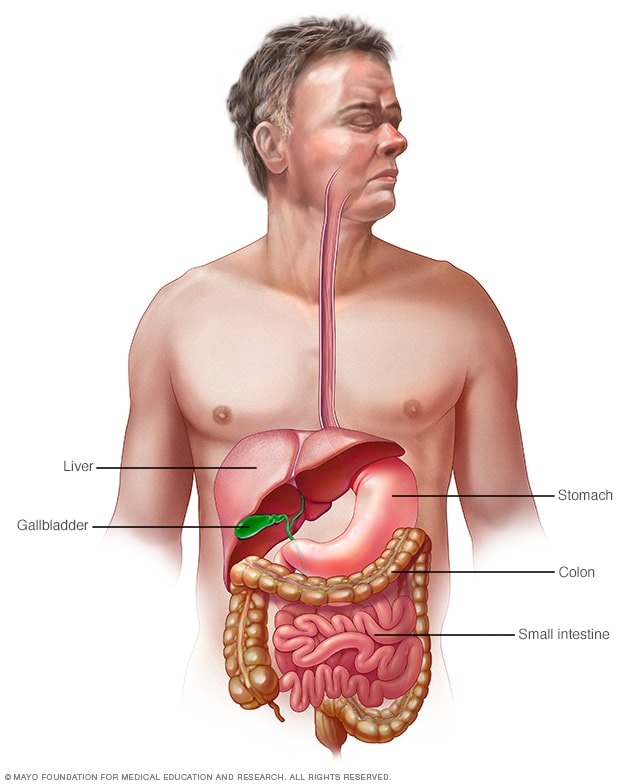

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- GP practice services

- Health advice

- Health research

- Medical professionals

- Health topics

Advice and clinical information on a wide variety of healthcare topics.

All health topics

Latest features

Allergies, blood & immune system

Bones, joints and muscles

Brain and nerves

Chest and lungs

Children's health

Cosmetic surgery

Digestive health

Ear, nose and throat

General health & lifestyle

Heart health and blood vessels

Kidney & urinary tract

Men's health

Mental health

Oral and dental care

Senior health

Sexual health

Signs and symptoms

Skin, nail and hair health

- Travel and vaccinations

Treatment and medication

Women's health

Healthy living

Expert insight and opinion on nutrition, physical and mental health.

Exercise and physical activity

Healthy eating

Healthy relationships

Managing harmful habits

Mental wellbeing

Relaxation and sleep

Managing conditions

From ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, to steroids for eczema, find out what options are available, how they work and the possible side effects.

Featured conditions

ADHD in children

Crohn's disease

Endometriosis

Fibromyalgia

Gastroenteritis

Irritable bowel syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Scarlet fever

Tonsillitis

Vaginal thrush

Health conditions A-Z

Medicine information

Information and fact sheets for patients and professionals. Find out side effects, medicine names, dosages and uses.

All medicines A-Z

Allergy medicines

Analgesics and pain medication

Anti-inflammatory medicines

Breathing treatment and respiratory care

Cancer treatment and drugs

Contraceptive medicines

Diabetes medicines

ENT and mouth care

Eye care medicine

Gastrointestinal treatment

Genitourinary medicine

Heart disease treatment and prevention

Hormonal imbalance treatment

Hormone deficiency treatment

Immunosuppressive drugs

Infection treatment medicine

Kidney conditions treatments

Muscle, bone and joint pain treatment

Nausea medicine and vomiting treatment

Nervous system drugs

Reproductive health

Skin conditions treatments

Substance abuse treatment

Vaccines and immunisation

Vitamin and mineral supplements

Tests & investigations

Information and guidance about tests and an easy, fast and accurate symptom checker.

About tests & investigations

Symptom checker

Blood tests

BMI calculator

Pregnancy due date calculator

General signs and symptoms

Patient health questionnaire

Generalised anxiety disorder assessment

Medical professional hub

Information and tools written by clinicians for medical professionals, and training resources provided by FourteenFish.

Content for medical professionals

FourteenFish training

Professional articles

Evidence-based professional reference pages authored by our clinical team for the use of medical professionals.

View all professional articles A-Z

Actinic keratosis

Bronchiolitis

Molluscum contagiosum

Obesity in adults

Osmolality, osmolarity, and fluid homeostasis

Recurrent abdominal pain in children

Medical tools and resources

Clinical tools for medical professional use.

All medical tools and resources

Traveller's diarrhoea

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP Last updated by Dr Toni Hazell Last updated 10 Feb 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

In this series: Amoebiasis Giardia

Traveller's diarrhoea is diarrhoea that develops during, or shortly after, travel abroad. It is caused by consuming food and water, contaminated by germs (microbes) including bacteria, viruses and parasites. Other symptoms can include high temperature (fever), being sick (vomiting) and tummy (abdominal) pain. In most cases it causes a mild illness and symptoms clear within 3 to 4 days. Specific treatment is not usually needed but it is important to drink plenty of fluids to avoid lack of fluid in the body (dehydration). Always make sure that you get any advice that you need in plenty of time before your journey - some GPs offer travel advice but if yours doesn't then you may need to go to a private travel clinic.

In this article :

What is traveller's diarrhoea, what causes traveller's diarrhoea, are all travellers at risk, what are the symptoms of traveller's diarrhoea, how is traveller's diarrhoea diagnosed, when should i seek medical advice for traveller's diarrhoea, how is traveller's diarrhoea in adults treated, how is traveller's diarrhoea in children treated, side-effects of traveller's diarrhoea, how long does traveller's diarrhoea last, how can i avoid traveller's diarrhoea.

Continue reading below

Traveller's diarrhoea is diarrhoea that develops during, or shortly after, travel abroad. Diarrhoea is defined as: 'loose or watery stools (faeces), usually at least three times in 24 hours.'

Traveller's diarrhoea is caused by eating food, or drinking water, containing certain germs (microbes) or their poisons (toxins). The types of germs which may be the cause include:

Bacteria: these are the most common microbes that cause traveller's diarrhoea. Common types of bacteria involved are:

Escherichia coli

Campylobacter

Viruses: these are the next most common, particularly norovirus and rotavirus.

Parasites: these are less common causes. Giardia, cryptosporidium and Entamoeba histolytica are examples of parasites that may cause traveller's diarrhoea.

Often the exact cause of traveller's diarrhoea is not found and studies have shown that in many people no specific microbe is identified despite testing (for example, of a stool (faeces) specimen).

See the separate leaflets called E. Coli (VTEC O157) , Campylobacter, Salmonella, Cryptosporidium , Amoebiasis (dysentery information), Shigella and Giardia for more specific details on each of the microbes mentioned above.

Note : this leaflet is about traveller's diarrhoea in general and how to help prevent it.

Traveller's diarrhoea most commonly affects people who are travelling from a developed country, such as the UK, to a developing country where sanitation and hygiene measures may not meet the same standards. It can affect as many as 2 to 6 in 10 travellers.

There is a different risk depending on whether you travel to high-risk areas or not:

High-risk areas : South and Southeast Asia, Central America, West and North Africa, South America, East Africa.

Medium-risk areas : Russia, China, Caribbean, South Africa.

Low-risk areas : North America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand.

Sometimes outbreaks of diarrhoea can occur in travellers staying in one hotel or, for example, those staying on a cruise ship. People travelling in more remote areas (for example, trekkers and campers) may also have limited access to medical care if they do become unwell.

By definition, diarrhoea is the main symptom. This can be watery and can sometimes contain blood. Other symptoms may include:

Crampy tummy (abdominal) pains.

Feeling sick (nausea).

Being sick (vomiting).

A high temperature (fever).

Symptoms are usually mild in most people and last for 3 to 4 days but they may last longer. Symptoms may be more severe in the very young, the elderly, and those with other health problems. Those whose immune systems are not working as well as normal are particularly likely to be more unwell. For example, people with untreated HIV infection, those on chemotherapy, those on long-term steroid treatment or those who are taking drugs which suppress their immune system, for example after a transplant or to treat an autoimmune condition

Despite the fact that symptoms are usually fairly mild, they can often mean that your travel itinerary is interrupted or may need to be altered.

Traveller's diarrhoea is usually diagnosed by the typical symptoms. As mentioned above, most people have mild symptoms and do not need to seek medical advice. However, in some cases medical advice is needed (see below).

If you do see a doctor, they may suggest that a sample of your stool (faeces) be tested. This will be sent to the laboratory to look for any microbes that may be causing your symptoms. Sometimes blood tests or other tests may be needed if you have more severe symptoms or develop any complications.

As mentioned above, most people with traveller's diarrhoea have relatively mild symptoms and can manage these themselves by resting and making sure that they drink plenty of fluids. However, you should seek medical advice in any of the following cases, or if any other symptoms occur that you are concerned about:

If you have a high temperature (fever).

If you have blood in your stools (faeces).

If it is difficult to get enough fluid because of severe symptoms: frequent or very watery stools or repeatedly being sick (vomiting).

If the diarrhoea lasts for more than 5-7 days.

If you are elderly or have an underlying health problem such as diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or kidney disease.

If you have a weakened immune system because of, for example, chemotherapy treatment, long-term steroid treatment, or HIV infection.

If you are pregnant.

If an affected child is under the age of 6 months.

If you develop any of the symptoms listed below that suggest you might have lack of fluid in your body (dehydration). If it is your child who is affected, there is a separate list for children.

Symptoms of dehydration in adults

Dizziness or light-headedness.

Muscle cramps.

Sunken eyes.

Passing less urine.

A dry mouth and tongue.

Becoming irritable.

Symptoms of severe dehydration in adults

Profound loss of energy or enthusiasm (apathy).

A fast heart rate

Producing very little urine.

Coma, which may occur.

Note : severe dehydration is a medical emergency and immediate medical attention is needed.

Symptoms of dehydration in children

Passing little urine.

A dry mouth.

A dry tongue and lips.

Fewer tears when crying.

Being irritable.

Having a lack of energy (being lethargic).

Symptoms of severe dehydration in children

Drowsiness.

Pale or mottled skin.

Cold hands or feet.

Very few wet nappies.

Fast (but often shallow) breathing.

Dehydration is more likely to occur in:

Babies under the age of 1 year (and particularly those under 6 months old). This is because babies don't need to lose much fluid to lose a significant proportion of their total body fluid.

Babies under the age of 1 year who were a low birth weight and who have not caught up with their weight.

A breastfed baby who has stopped being breastfed during their illness.

Any baby or child who does not drink much when they have a gut infection (gastroenteritis).

Any baby or child with severe diarrhoea and vomiting. (For example, if they have passed five or more diarrhoeal stools and/or vomited two or more times in the previous 24 hours.)

In most cases, specific treatment of traveller's diarrhoea is not needed. The most important thing is to make sure that you drink plenty of fluids to avoid lack of fluid in your body (dehydration).

Fluid replacement

As a rough guide, drink at least 200 mls after each watery stool (bout of diarrhoea).

This extra fluid is in addition to what you would normally drink. For example, an adult will normally drink about two litres a day but more in hot countries. The above '200 mls after each watery stool' is in addition to this usual amount that you would drink.

If you are sick (vomit), wait 5-10 minutes and then start drinking again but more slowly. For example, a sip every 2-3 minutes but making sure that your total intake is as described above.

You will need to drink even more if you are dehydrated. A doctor will advise on how much to drink if you are dehydrated.

Note : if you suspect that you are becoming dehydrated, you should seek medical advice.

For most adults, fluids drunk to keep hydrated should mainly be water. However, this needs to be safe drinking water - for example, bottled, or boiled and treated water. It is best not to have drinks that contain a lot of sugar, such as fizzy drinks, as they can sometimes make diarrhoea worse. Alcohol should also be avoided.

Rehydration drinks

Rehydration drinks may also be used. They are made from sachets that you can buy from pharmacies and may be a sensible thing to pack in your first aid kit when you travel. You add the contents of the sachet to water.

Home-made salt/sugar mixtures are used in developing countries if rehydration drinks are not available; however, they have to be made carefully, as too much salt can be dangerous. Rehydration drinks are cheap and readily available in the UK, and are the best treatment. Note that safe drinking water should be used to reconstitute oral rehydration salt sachets.

Antidiarrhoeal medication

Antidiarrhoeal medicines are not usually necessary or wise to take when you have traveller's diarrhoea. However you may want to use them if absolutely necessary - for example, if you will be unable to make regular trips to the toilet due to travelling.You can buy antidiarrhoeal medicines from pharmacies before you travel. The safest and most effective is loperamide.

The adult dose of this is two capsules at first. This is followed by one capsule after each time you pass some diarrhoea up to a maximum of eight capsules in 24 hours. It works by slowing down your gut's activity.

You should not take loperamide for longer than two days. You should also not use antidiarrhoeal medicines if you have a high temperature (fever) or bloody diarrhoea.

Eat as normally as possible

It used to be advised to 'starve' for a while if you had diarrhoea. However, now it is advised to eat small, light meals if you can. Be guided by your appetite. You may not feel like food and most adults can do without food for a few days. Eat as soon as you are able but don't stop drinking. If you do feel like eating, avoid fatty, spicy or heavy food. Plain foods such as bread and rice are good foods to try eating.

Antibiotic medicines

Most people with traveller's diarrhoea do not need treatment with antibiotic medicines. However, sometimes antibiotic treatment is advised. This may be because a specific germ (microbe) has been identified after testing of your stool (faeces) sample.

Fluids to prevent dehydration

You should encourage your child to drink plenty of fluids. The aim is to prevent lack of fluid in the body (dehydration). The fluid lost in their sick (vomit) and/or diarrhoea needs to be replaced. Your child should continue with their normal diet and usual drinks. In addition, they should also be encouraged to drink extra fluids. However, avoid fruit juices or fizzy drinks, as these can make diarrhoea worse.

Babies under 6 months old are at increased risk of dehydration. You should seek medical advice if they develop acute diarrhoea. Breast feeds or bottle feeds should be encouraged as normal. You may find that your baby's demand for feeds increases. You may also be advised to give extra fluids (either water or rehydration drinks) in between feeds.

If you are travelling to a destination at high risk for traveller's diarrhoea, you might want to consider buying oral rehydration sachets for children before you travel. These can provide a perfect balance of water, salts and sugar for them and can be used for fluid replacement. Remember that, as mentioned above, safe water is needed to reconstitute the sachets.

If your child vomits, wait 5-10 minutes and then start giving drinks again but more slowly (for example, a spoonful every 2-3 minutes). Use of a syringe can help in younger children who may not be able to take sips.

Note : if you suspect that your child is dehydrated, or is becoming dehydrated, you should seek medical advice urgently.

Fluids to treat dehydration

If your child is mildly dehydrated, this may be treated by giving them rehydration drinks. A doctor will advise about how much to give. This can depend on the age and the weight of your child. If you are breastfeeding, you should continue with this during this time. It is important that your child be rehydrated before they have any solid food.

Sometimes a child may need to be admitted to hospital for treatment if they are dehydrated. Treatment in hospital usually involves giving rehydration solution via a special tube called a 'nasogastric tube'. This tube passes through your child's nose, down their throat and directly into their stomach. An alternative treatment is with fluids given directly into a vein (intravenous fluids).

Eat as normally as possible once any dehydration has been treated

Correcting any dehydration is the first priority. However, if your child is not dehydrated (most cases), or once any dehydration has been corrected, then encourage your child to have their normal diet. Do not 'starve' a child with infectious diarrhoea. This used to be advised but is now known to be wrong. So:

Breastfed babies should continue to be breastfed if they will take it. This will usually be in addition to extra rehydration drinks (described above).

Bottle-fed babies should be fed with their normal full-strength feeds if they will take it. Again, this will usually be in addition to extra rehydration drinks (described above). Do not water down the formula, or make it up with less water than usual. This can make a baby very ill.

Older children - offer them some food every now and then. However, if he or she does not want to eat, that is fine. Drinks are the most important consideration and food can wait until the appetite returns.

Loperamide is not recommended for children with diarrhoea. There are concerns that it may cause a blockage of the gut (intestinal obstruction) in children with diarrhoea.

Most children with traveller's diarrhoea do not need treatment with antibiotics. However, for the same reasons as discussed for adults above, antibiotic treatment may sometimes be advised in certain cases.

Most people have mild illness and complications of traveller's diarrhoea are rare. However, if complications do occur, they can include the following:

Salt (electrolyte) imbalance and dehydration .

This is the most common complication. It occurs if the salts and water that are lost in your stools (faeces), or when you are sick (vomit), are not replaced by you drinking adequate fluids. If you can manage to drink plenty of fluids then dehydration is unlikely to occur, or is only likely to be mild and will soon recover as you drink.

Severe dehydration can lead to a drop in your blood pressure. This can cause reduced blood flow to your vital organs. If dehydration is not treated, your kidneys may be damaged . Some people who become severely dehydrated need a 'drip' of fluid directly into a vein. This requires admission to hospital. People who are elderly or pregnant are more at risk of dehydration.

Reactive complications

Rarely, other parts of your body can 'react' to an infection that occurs in your gut. This can cause symptoms such as joint inflammation (arthritis), skin inflammation and eye inflammation (either conjunctivitis or uveitis). Reactive complications are uncommon if you have a virus causing traveller's diarrhoea.

Spread of infection

The infection can spread to other parts of your body such as your bones, joints, or the meninges that surround your brain and spinal cord. This is rare. If it does occur, it is more likely if diarrhoea is caused by salmonella infection.

Irritable bowel syndrome is sometimes triggered by a bout of traveller's diarrhoea.

Lactose intolerance

Lactose intolerance can sometimes occur for a period of time after traveller's diarrhoea. It is known as 'secondary' or 'acquired' lactose intolerance. Your gut (intestinal) lining can be damaged by the episode of diarrhoea. This leads to lack of a substance (enzyme) called lactase that is needed to help your body digest the milk sugar lactose.

Lactose intolerance leads to bloating, tummy (abdominal) pain, wind and watery stools after drinking milk. The condition gets better when the infection is over and the intestinal lining heals. It is more common in children.

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Usually associated with traveller's diarrhoea caused by a certain type of E. coli infection, haemolytic uraemic syndrome is a serious condition where there is anaemia, a low platelet count in the blood and kidney damage. It is more common in children. If recognised and treated, most people recover well.

Guillain-Barré syndrome

This condition may rarely be triggered by campylobacter infection, one of the causes of traveller's diarrhoea. It affects the nerves throughout your body and limbs, causing weakness and sensory problems. See the separate leaflet called Guillain-Barré syndrome for more details.

Reduced effectiveness of some medicines

During an episode of traveller's diarrhoea, certain medicines that you may be taking for other conditions or reasons may not be as effective. This is because the diarrhoea and/or being sick (vomiting) mean that reduced amounts of the medicines are taken up (absorbed) into your body.

Examples of such medicines are those for epilepsy, diabetes and contraception . Speak with your doctor or practice nurse before you travel if you are unsure of what to do if you are taking other medicines and develop diarrhoea.

As mentioned above, symptoms are usually short-lived and the illness is usually mild with most people making a full recovery within in few days. However, a few people with traveller's diarrhoea develop persistent (chronic) diarrhoea that can last for one month or more. It is also possible to have a second 'bout' of traveller's diarrhoea during the same trip. Having it once does not seem to protect you against future infection.

Avoid uncooked meat, shellfish or eggs. Avoid peeled fruit and vegetables (including salads).

Be careful about what you drink. Don't drink tap water, even as ice cubes.

Wash your hands regularly, especially before preparing food or eating.

Be careful where you swim. Contaminated water can cause traveller's diarrhoea.

Regular hand washing

You should ensure that you always wash your hands and dry them thoroughly; teach children to wash and dry theirs:

After going to the toilet (and after changing nappies or helping an older child to go to the toilet).

Before preparing or touching food or drinks.

Before eating.

Some antibacterial hand gel may be a good thing to take with you when you travel in case soap and hot water are not available.

Be careful about what you eat and drink

When travelling to areas with poor sanitation, you should avoid food or drinking water that may contain germs (microbes) or their poisons (toxins). Avoid:

Fruit juices sold by street vendors.

Ice cream (unless it has been made from safe water).

Shellfish (for example, mussels, oysters, clams) and uncooked seafood.

Raw or undercooked meat.

Fruit that has already been peeled or has a damaged skin.

Food that contains raw or uncooked eggs, such as mayonnaise or sauces.

Unpasteurised milk.

Drinking bottled water and fizzy drinks that are in sealed bottles or cans, tea, coffee and alcohol is thought to be safe. However, avoid ice cubes and non-bottled water in alcoholic drinks. Food should be cooked through thoroughly and be piping hot when served.

You should also be careful when eating food from markets, street vendors or buffets if you are uncertain about whether it has been kept hot or kept refrigerated. Fresh bread is usually safe, as is canned food or food in sealed packs.

Be careful where you swim

Swimming in contaminated water can also lead to traveller's diarrhoea. Try to avoid swallowing any water as you swim; teach children to do the same.

Obtain travel health advice before you travel

Always make sure that you visit your GP surgery or private travel clinic for health advice in plenty of time before your journey. Alternatively, the Fit for Travel website (see under Further Reading and References, below) provides travel health information for the public and gives specific information for different countries and high-risk destinations. This includes information about any vaccinations required, advice about food, water and personal hygiene precautions, etc.

There are no vaccines that prevent traveller's diarrhoea as a whole. However, there are some other vaccines that you may need for your travel, such as hepatitis A, typhoid, etc. You may also need to take malaria tablets depending on where you are travelling.

Antibiotics

Taking antibiotic medicines to prevent traveller's diarrhoea (antibiotic prophylaxis) is not generally recommended. This is because for most people, traveller's diarrhoea is mild and self-limiting. Also, antibiotics do not protect against nonbacterial causes of traveller's diarrhoea, such as viruses and parasites. Antibiotics may have side-effects and their unnecessary use may lead to problems with resistance to medicines.

Probiotics have some effect on traveller's diarrhoea and can shorten an attack by about one day. It is not known yet which type of probiotic or which dose, so there are no recommendations about using probiotics to prevent traveller's diarrhoea.

Further reading and references

- Bourgeois AL, Wierzba TF, Walker RI ; Status of vaccine research and development for enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Vaccine. 2016 Mar 15. pii: S0264-410X(16)00287-5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.076.

- Travellers' diarrhoea ; Fitfortravel

- Riddle MS, Connor BA, Beeching NJ, et al ; Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers' diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. J Travel Med. 2017 Apr 1;24(suppl_1):S57-S74. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tax026.

- Giddings SL, Stevens AM, Leung DT ; Traveler's Diarrhea. Med Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;100(2):317-30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.08.017.

- Diarrhoea - prevention and advice for travellers ; NICE CKS, February 2019 (UK access only)

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 9 Feb 2028

10 feb 2023 | latest version.

Last updated by

Peer reviewed by

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Traveler's Diarrhea

What is traveler's diarrhea, what causes traveler's diarrhea.

It’s caused by drinking water or eating food that has bacteria, viruses, or parasites. Most traveler's diarrhea is from bacteria. Diarrhea from viruses and parasites is less common. Food and water can be infected by people:

- Not washing hands after using the bathroom

- Storing food unsafely

- Handling and preparing food unsafely

- Not cleaning surfaces and utensils safely

Who is at risk for traveler's diarrhea?

You are at risk for this condition if you travel to a country that has poor public sanitation and hygiene. Poor hygiene in local restaurants is also a risk factor. Places that have the highest risk are often in developing countries in:

- Central and South America

- The Middle East

If you travel to a developing country, you are more likely to get this illness if you eat food or have drinks:

- Bought on the street, such as from a food cart

- In someone’s home

- At lodging that provides all meals (all-inclusive)

You’re also at increased risk if you:

- Take some kinds of ulcer medicine

- Have had some kinds of gastrointestinal surgery

What are the symptoms of traveler's diarrhea?

The main symptom is loose stool that occurs suddenly. The stool may be watery. Other symptoms may include:

- Belly (abdominal) pain or cramps

- Blood in the stool

- Trouble waiting to have a bowel movement (urgency)

- Feeling tired

In most cases, symptoms last less than a week.

How is traveler's diarrhea diagnosed?

How is traveler's diarrhea treated, what are possible complications of traveler's diarrhea.

The loss of body fluid from diarrhea and vomiting can lead to dehydration. This can be serious. Contact your healthcare provider if you are not urinating as much as usual.

A small number of people can develop post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. This can cause symptoms such as:

- Long-term diarrhea

- Belly pain and cramping

What can I do to prevent traveler's diarrhea?

You can take steps to prevent traveler's diarrhea.

Only use water that has been boiled or chemically disinfected for:

- Making tea or coffee

- Brushing your teeth

- Washing your face

- Washing your hands (or use alcohol-based gel)

- Washing fruits and vegetables

- Washing food utensils, equipment, or surfaces

- Washing the surfaces of food or drink tins, cans, and bottles

Don't eat foods such as:

- Raw fruits, vegetables, or salad greens

- Unpasteurized milk, cheese, ice cream, or yogurt

- Any fish caught in tropical reefs rather than the open ocean

- Condiments that are left on the table, such as ketchup, mustard, sauces, or dips

Also make sure to:

- Not eat food from unknown sources

- Not put ice in drinks

- Only have drinks that are bottled and sealed

- Use drinking straws instead of drinking directly from glasses or cups

- Only take antibiotic or antidiarrheal medicine if advised by your health care provider (these can make symptoms worse, which can be dangerous)

When should I call my healthcare provider?

Call a healthcare provider if you:

- Have diarrhea that is severe or bloody

- Have belly pain that is getting worse or not going away

- Have a high fever

- Are not getting better within a few days

- Have signs of dehydration, such as urinating less

- Traveler's diarrhea occurs within 10 days of travel to an area with poor public hygiene. It’s the most common illness in travelers.

- It’s caused by drinking water or eating foods that have bacteria, viruses, or parasites.

- It usually goes away without treatment in a few days.

- Dehydration from diarrhea can be serious. You need to replace body fluid that has been lost.

- See a healthcare provider if your symptoms are severe or last for more than a few days.

- You can prevent it by avoiding unsafe water and not eating unsafe foods.

Tips to help you get the most from a visit to your healthcare provider:

- Know the reason for your visit and what you want to happen.

- Before your visit, write down questions you want answered.

- Bring someone with you to help you ask questions and remember what your provider tells you.

- At the visit, write down the name of a new diagnosis, and any new medicines, treatments, or tests. Also write down any new instructions your provider gives you.

- Know why a new medicine or treatment is prescribed, and how it will help you. Also know what the side effects are.

- Ask if your condition can be treated in other ways.

- Know why a test or procedure is recommended and what the results could mean.

- Know what to expect if you do not take the medicine or have the test or procedure.

- If you have a follow-up appointment, write down the date, time, and purpose for that visit.

- Know how you can contact your provider if you have questions.

Find a Doctor

Specializing In:

- Gastroenterology

- Indigestion

- Diarrheal Disease

- Clostridium Difficile

At Another Johns Hopkins Member Hospital:

- Howard County Medical Center

- Sibley Memorial Hospital

- Suburban Hospital

Find a Treatment Center

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Find Additional Treatment Centers at:

Request an Appointment

Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis

Diarrhea in Children

Related Topics

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Best Traveler's Diarrhea Treatments for Symptom Relief

Sources of Bacteria, Prevention, and Medication Types

Complications

Frequently asked questions.

Traveler's diarrhea can turn a trip into a nightmare. Food and water contaminated by germs, also known as pathogens , is not uncommon in certain areas of the world that are popular travel destinations. Consuming even small amounts of these germs can cause loose, watery stool, the main sign of diarrhea , Luckily, treatment options are available.

This article explains the symptoms of traveler's diarrhea, how to treat it, and the best ways to prevent getting infected in the first place.

Luis Alvarez / Getty Images

Symptoms of traveler's diarrhea caused by bacteria or a virus usually appear six to 72 hours after eating or drinking something contaminated. With some types of pathogens, it may take a week or longer for stool to be affected.

Changes in your bowel habits it the main symptoms of diarrhea. At its mildest, diarrhea involves passing loose, watery stool three times a day. You may pass unformed stool 10 or more times a day in severe cases.

Other symptoms vary depending on the type of bacterial or virus you've been exposed to but may include:

- Stomach cramps

- Tenesmus , feeling you need to have a bowel movement even when your bowels are empty

- Mucous in stool

More severe cases of traveler's diarrhea may cause bloody stools .

Should You Go to a Doctor for Traveler's Diarrhea?

See a healthcare provider if your symptoms are accompanied by fever or bloody stools, or they last longer than 48 hours.

Traveler's Diarrhea Causes

The most common cause of traveler's diarrhea is probably poor hygiene (lack of cleanliness) in restaurants. You're most at risk when dining out in areas of Asia, the Middle East, Mexico, Africa, and South and Central America.

Pathogens are usually spread via the fecal-oral route . This means someone with the bacteria or virus excretes the germs in their feces. The feces may not be safely disposed of in a sanitary setting, or the infected person may not properly wash their hands before handling food and beverages. This allows germs to be transmitted to something you put into your mouth.

This cycle of contamination is most common in areas of the world that have specific conditions:

- Warmer climates that promote germ growth

- Poor sanitation (such as open sewage areas)

- Unreliable refrigeration

- Little education on safe food handling.

Common Bacterial Pathogens

The most common cause of traveler's diarrhea is bacteria, which are thought to lead to 80% to 90% of cases. These include:

- Escherichia coli or E-coli

- Campylobacter jejuni

Ingesting these bacterium causes gastroenteritis , which means the stomach and small intestines become inflamed. This leads to diarrhea.

Common Viral Pathogens

Viruses can also be transported via the fecal-oral route. The most common types of viruses that cause diarrhea include:

Viral infections of the digestive system are often referred to as stomach flu . The illness has no connection to respiratory influenza, but like the "flu," it usually lasts a short period.

Other Causes of Diarrhea

In addition to germs in your food and water, you could develop diarrhea from toxins, which cause the common symptoms of food poisoning .

Parasites , or protozoal pathogens, can also cause diarrhea. In these instances, you're more likely to develop symptoms one to two weeks after exposure to the pathogen.

Dehydration is one of the most common complications related to any form of diarrhea. Multiple bowel movements that release a lot of fluid can cause you to have too little water in your body.

Severe dehydration can lead to problems such as:

- Fatigue and muscle weakness or pain

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Increased heart rate and breathing

- Kidney Failure

Dysentery is a serious condition that can develop from exposure to Shigella or parasites. It usually causes bloody stool, fever, and extreme dehydration. It can be fatal if it's left untreated. In addition to being picked up from contaminated food or water, the bacteria or parasites that cause dysentery can be passed from person to person in close contact, or you can get it by swimming in unclean water.

Treatment for Traveler's Diarrhea

Getting sick while far from home is more than just inconvenient. The sudden onset and severity of symptoms can be frightening. Often, symptoms will last a few days and resolve on their own, but you may need to manage the condition and take medication.

Fluid Replacement

To manage dehydration, you want to concentrate on getting enough liquids even if you feel like you don't want to put anything in your stomach.

Drinking any safe fluids can manage mild cases of traveler's diarrhea. Since tap water may be a source of infection, you need to boil non-bottled water and let it cool before you drink it. You can also drink boiled broth or prepackaged (non-citrus) fruit juice. Sports drinks like Gatorade are good, too, but not essential.

For severe dehydration, an oral rehydration solution may be needed. These are mixes or packaged beverages that contain glucose and electrolytes such as potassium and sodium. Pedialyte is an example of an oral rehydration solution for kids.

Sweating can cause dehydration as well. Try to find a cool place out of the sun to rest while you rehydrate.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics may be used for traveler's diarrhea caused by bacterial infections. A stool test should be done to identify which antibiotic might work best.

Quinolone antibiotics such as Cipro (ciprofloxacin) are most often used when antibiotics are needed.

A single dose of 750 milligrams (mg) for adults is the typical treatment. Children may be given 20 to 30 mg per kilogram of weight per day.

In some areas, bacteria are resistant to quinolones, which means the medication won't help. This is especially a problem in Southeast Asia. Another antibiotic, azithromycin , may also be used in this case, although some strains are resistant to it.

Upset Stomach Medication

Pepto-Bismol can provide short-term relief of symptoms. However, it may not be effective in small doses, and high doses put you at risk for a health condition called salicylate toxicity. Additionally, Pepto-Bismol is not recommended for people younger than 18 years because there's a risk of a condition called Reye's syndrome .

Antidiarrheal Agents

It might seem logical to reach for an anti-diarrheal product such as Imodium (loperamide) or Lomotil (diphenoxylate). However, these products should not be used if your diarrhea is related to dysentery or if you see any signs of blood in your stools.

An antidiarrheal agent should only be taken with an antibiotic. When using an antidiarrheal for traveler's diarrhea, it is especially important to keep yourself well-hydrated. Discontinue the product if your symptoms worsen or you still have diarrhea after two days.

How Long Traveler's Diarrhea Lasts

Most cases of traveler's diarrhea last from one to five days. However, symptoms may linger for several weeks.

To help prevent traveler's diarrhea:

- Wash your hands with soap and water after going to the bathroom and before eating.

- At restaurants, only eat foods that are cooked and served hot.

- Drink beverages from factory-sealed bottles or containers.

- Don't get ice in your drink since it may be made with contaminated water.

There is evidence that Pepto-Bismol may protect against traveler's diarrhea. Studies have shown a protection rate of about 60%. However, not everyone should take Pepto-Bismol, including those who are pregnant or are 18 years of age and younger.

Don't take antibiotics or antidiarrheal medicine like Pepto-Bismol as prophylaxis—that is, to prevent traveler's diarrhea— unless it's been recommended to you by your healthcare provider.

Bacteria and viruses can live in water and food. These pathogens (germs) are most common in areas where the climate is warm, refrigeration is unreliable, and there isn't proper hand washing or bathroom sanitation. Infection with these pathogens (bacterial or viral) can cause traveler's diarrhea.

Traveler's diarrhea will often resolve on its own once the bacteria or virus is out of your system. However, you may need antibiotics. You may also need to manage symptoms by staying hydrated and using over-the-counter medications. You should contact your healthcare provider if symptoms last more than a few days.

When traveling to regions that have warm climates and relaxed hygiene practices, be sure to take steps to avoid eating or drinking anything that could have pathogens. Drink pre-packed or boiled water and ensure food is handled properly.

It's important to make sure that your child gets enough fluids. Diarrhea can lead to dehydration more quickly in kids than in adults. Check with your healthcare provider if your child has signs of dehydration such as dry mouth, few or no tears when crying, irritability, reduced urination, and drowsiness.

If you're pregnant, the most important thing to do is to drink enough fluids so you don't get dehydrated. Your doctor may suggest using azithromycin if you need an antibiotic. Don't use Pepto-Bismol (bismuth subsalicylate) when pregnant because of risks to the growing fetus.

Connor BA. Preparing international travelers: Travelers’ diarrhea . In: Brunette GW, ed. CDC Yellow Book 2020: Health information for international travel . Oxford University Press; 2017.

Leung AKC, Leung AAM, Wong AHC, Hon KL. Travelers’ diarrhea: a clinical review . Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov . 2019;13(1):38-48. doi:10.2174/1872213X13666190514105054

Shaheen NA, Alqahtani AA, Assiri H, Alkhodair R, Hussein MA. Public knowledge of dehydration and fluid intake practices: variation by participants' characteristics . BMC Public Health . 2018;18(1):1346. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6252-5

Strachan SR, Morris LF. Management of severe dehydration . Pediatr Crit Care Med . 2017;18(3):251-255. doi:10.1177/1751143717693859

Riddle MS, Connor BA, Beeching NJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report . J Travel Med . 2017;24(suppl_1):S57-S74. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax026

Johns Hopkins Medicine. Traveler's Diarrhea.

Nemours Foundation. KidsHealth. Staying healthy while you travel.

Morof DF, Carroll ID. Family travel: Pregnant travelers . In: Brunette GW, ed. CDC Yellow Book 2020: Health information for international travel . Oxford University Press; 2017.

Wanke, Christine A. " Travelers' Diarrhea ." UpToDate .

By Barbara Bolen, PhD Barbara Bolen, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and health coach. She has written multiple books focused on living with irritable bowel syndrome.

Issues by year

Advertising

Volume 44, Issue 1, January-February 2015

Advising travellers about management of travellers’ diarrhoea

How is td defined.

Classic, severe TD is usually defined as at least three unformed bowel movements occurring within a 24-hour period, often accompanied by cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever and/or blood in the stools. 5–7 Moderate TD is defined as one or two unformed bowel movements and other symptoms occurring every 24 hours or as three or more unformed bowel movements without additional symptoms. Mild TD is defined as one or two unformed bowel movements without any additional symptoms and without interference with daily activities. 8,9 TD generally resolves spontaneously, usually after 3–4 days, 8 but, in the interim, frequently leads to disruption of planned activities.

What are the causes of TD?

Approximately 50–80% of TD is caused by bacterial infections; enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is the most common cause overall. Other bacterial causes include enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), Shigella , Campylobacter and Salmonella species. The exact breakdown of organisms varies according to destination, season and other factors. Noroviruses cause 10–20% of TD cases. Protozoal parasites should be considered particularly in those with persistent diarrhoea (illness lasting ≥14 days) or when antibacterial therapy fails to shorten illness. 10

How can TD be prevented?

Methods for preventing TD include avoidance, immunisation, non-antibiotic interventions or antibiotic prophylaxis. 11

What avoidance measures are generally recommended and do they work?

Avoidance of TD has traditionally relied on recommendations regarding careful food and drink choices (avoiding untreated/unboiled tap water, including ice and water used for brushing teeth, and raw foods such as salads, uncooked vegetables or fruits that cannot be peeled). This underpins the saying ‘Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it…. easy to remember, impossible to do’. Additional standard advice is that undercooked or raw meat, fish and shellfish are high-risk foods. However, whether deliberately or inadvertently, most people find it very difficult to adhere to dietary restrictions 12 and over 95% of people disobey the rules of ‘safe’ eating and drinking within a few days of leaving home. Additionally, there is minimal evidence for a correlation between adherence to dietary precautions and a reduced risk of TD, 13 although common sense nevertheless supports care with food selection. 4

Where people eat may be more important than what people eat. Risks are associated, in descending order, with street vendors, restaurants and private homes. Use of antibacterial handwash before eating is also recommended. 14

Which vaccines can be considered?

Immunisation has little practical role in the prevention of TD and the only potentially relevant vaccines are those against rotavirus (infants only) and the oral cholera vaccine.

The cholera vaccine has >90% efficacy for prevention of Vibrio cholera but travellers are rarely at risk of infection with this pathogen. 1 The vaccine contains a recombinant B subunit of the cholera toxin that is antigenically similar to the heat-labile toxin of ETEC; therefore, the cholera vaccine may also reduce ETEC TD. However, it is not licensed for TD prevention in Australia and, although initially thought to offer a 15–20% short-term (3 months) reduction in TD, a recent Cochrane review showed no statistically significant effects on ETEC diarrhoea or all-cause diarrhoea. 15 Overall, there is, therefore, insufficient evidence to support general use of the cholera vaccine for TD protection, but it may still be considered for individuals with increased risk of severe or complicated TD (eg immunosuppressed or underlying inflammatory bowel disease).

Other vaccines directed against organisms spread by the faecal–oral route are the vaccines for typhoid, hepatitis A and polio, but infection with these organisms rarely causes TD. 15

Do non-antibiotic interventions work?

Several probiotic agents have been studied for treatment and prevention of TD, including Lactobacillus and Saccharomyces preparations. However, their effectiveness for TD prevention has been limited, 11,16,17 and a consensus group has recommended against their use. 4 Other over-the-counter agents are also available (eg travelan, which contains bovine colostrum harvested from cows immunised with an ETEC vaccine) but data regarding overall efficacy of reducing all-cause TD are currently lacking.

Should antibiotic prophylaxis against TD be given?

Quinolone antibiotics are highly effective (80–95%) in preventing TD, but antibiotic prophylaxis is rarely indicated. 4 It may result in a false sense of security and hence less caution in dietary choices, it poses risks of side effects, diarrhoea associated with Clostridium difficile , and, more importantly, would lead to a vast amount of antibiotic use, thus predisposing to more rapid development of antibiotic resistance globally. 11 Therefore non-antibiotic options for prevention and a focus instead on empirical self-treatment if needed according to symptoms are the mainstay of management, aligning with the antimicrobial stewardship perspective of minimisation of antimicrobial overuse and reducing promotion of antimicrobial resistance.

In rare circumstances, it may be reasonable to consider short courses of antibiotic prophylaxis in individuals at very high risk of infection (eg severely immunocompromised). 11 Globally, one of the most commonly used agents in this regard is rifaximin, a non-absorbed semisynthetic rifamycin derivative, which has been shown to be effective and is approved for use for TD prevention in some countries, but it is not approved for this indication in Australia. Other options include the antibiotics discussed below for TD self-treatment.

How should self-treatment of TD be managed?

Because of the limitations of TD prevention measures, the pre-travel consultation should be viewed as an opportunity to ‘arm’ travellers with the knowledge and medication needed to appropriately self-treat, should TD occur during their trip.

The first goal of therapy is the prevention and treatment of dehydration, which is of particular concern for young children, pregnant women and the elderly. Commercial packets of oral rehydration salts are readily available in pharmacies and should be purchased before travel. The other element of TD self-treatment is to recommend travellers bring an antimotility agent plus an antibiotic with them. Loperamide is preferred over the diphenoxylate/atropine combination, as the latter agent is generally less effective and associated with a greater potential for adverse effects.

When should loperamide alone versus loperamide plus an antibiotic be taken?

For mild symptoms of watery diarrhoea, self-treatment with oral rehydration plus loperamide is recommended. Loperamide therapy alone has no untoward effects in mild TD 18 but if symptoms worsen, or do not improve after 24 hours, antibiotics should be added. If TD is moderate or severe at onset, then combination therapy with loperamide plus antibiotics should be started immediately, as this optimises the clinical benefit of self-treatment by providing more rapid relief and shortening the symptom duration. 10,19

The recommended dose of loperamide is two tablets (4 mg) stat, then one tablet after each bowel motion to a maximum of eight per 24-hour period until the TD has resolved. Despite warnings regarding the safety of antidiarrhoeal agents with bloody diarrhoea or diarrhoea accompanied by fever, the combination with antibiotics is likely to be safe in the setting of mild febrile dysentery, 18 and a number of studies have shown the combination to be more efficacious than use of either agent alone. 7,18–20 Rapid institution of effective treatment shortens symptoms to 30 hours or less in most people. 12 For example, the duration of diarrhoea was significantly ( P = 0.0002) shorter following treatment with azithromycin plus loperamide (11 h) than with azithromycin alone (34 h). 19

Which antibiotic should be recommended for empirical elf-treatment of TD?

The most commonly used antibiotics for empirical TD therapy are fluoroquinolones (either norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin) or azithromycin ( Table 1 ). Cotrimoxazole has been used but is no longer recommended because of widespread resistance. For TD caused by ETEC, the fluoroquinolones and azithromycin have similar efficacy; however, in Asia (particularly South and South-East Asia), Campylobacter is a common cause of TD and strains occurring in this part of the world show a high degree of resistance to fluoroquinolones. 10,21 Therefore, azithromycin is preferred for travellers to this region. Azithromycin remains generally efficacious despite emerging resistance, and is also the preferred treatment for diarrhoea with complications of dysentery or high fever, and for use in pregnant women or children under the age of 8 years, in whom avoidance of quinolones is preferred. Moreover, the 24-hour dosing of azithromycin may be preferable to the 12-hourly dosing schedule required with fluoroquinolones.

What is the optimal dosing schedule?

The fluoroquinolones and azithromycin have been administered as a single dose or for 3 days ( Table 1 ). Usually a single dose is adequate and there is no apparent clinically important difference in efficacy with either dosing schedule for TD. 10 However, for bacteria such as Campylobacter and Shigella dysenteriae , single-dose therapy may be inadequate. 11 It is reasonable, therefore, to give travellers a 3-day supply of antibiotics and tell them to continue taking the therapy (either 12- or 24-hourly, depending on which antibiotic is prescribed) only if their TD symptoms persist. If the TD has resolved, no further antibiotics need to be taken and any remaining antibiotic doses can be kept in case of a second bout of TD. It is prudent to specifically highlight that this advice differs from the usual instructions to take all tablets even if symptoms have resolved.

What is the optimal empirical TD management in children?

There are few data on empirical treatment of TD in children and limited options for therapy. The mainstay of therapy is oral rehydration solution, particularly for children <6 years of age. Antimotility agents are contraindicated for children because of the increased risk of adverse effects, especially paralytic ileus, toxic megacolon and drowsiness (narcotic effect) with loperamide. 1 The lower age limit recommended for avoiding loperamide varies by location; US guidelines state that loperamide should not be given to infants <2 years of age, the UK <4 years and Australian guidelines state <12 years. 14 However, most Australian practitioners are prepared to use loperamide in children aged 6 years or older, if needed to control symptoms.

A paediatric (powder) formulation of azithromycin is available and is the most commonly recommended agent for children. The usual dose is 10–25 mg/kg for up to 3 days. A practical tip is to ensure that the pharmacy does not reconstitute the powder into a solution, as once dissolved, the solution lasts only for 10 days. Instead, sterile water should be provided along with instructions on how to reconstitute the powder if needed. Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin 10mg/kg bd) are an alternative option if there are reasons for avoiding azithromycin, with previous concerns regarding potential effects on cartilage not substantiated in recent studies. 14,22

Does starting antibiotics early prevent the chances of developing prolonged symptoms?

Although TD symptoms are short-lived in most cases, 8–15% of affected travellers are symptomatic for more than a week and 2% develop chronic diarrhoea lasting a month or more. 11 Episodes of TD have been shown to be associated with a quintuple risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and post-travel IBS occurs in 3–10% of travellers. However, it is unknown whether IBS can be prevented by starting antimicrobial therapy earlier in the course of enteric infection. 4,18,23

Should tinidazole also be prescribed and, if so, for whom?

Tinidazole can be prescribed as a second antibiotic for empirical self‑treatment as it is effective against the protozoan parasitic enteric pathogen Giardia intestinalis . A dose of 2 g (4 x 500 mg tablets) stat is recommended. However, for most short-term travellers, tinidazole may be unnecessary and the complexity of the additional instructions required may be unwarranted. It is optimally recommended, therefore, for travellers departing on trips of significant duration (>2–3 weeks). If prescribed, the instructions should be to take tinidazole if the TD persists following the 3-day course of antibiotic therapy (fluoroquinolone or azithromycin). This will mean that the TD has lasted for at least 72 hours, thus increasing the likelihood of a parasitic cause.

When should medical care for acute symptoms be recommended?

While most episodes of TD are amenable to self-treatment, if there is a risk of dehydration due to intolerance of oral fluids or comorbidities, as well as in the setting of frank blood in the stool or unremitting fevers (>38.5°C for 48 hours), medical therapy should be sought. 18

How should TD be managed after return?

While a full description of TD management is beyond the scope of this article, for returning travellers with diarrhoea, at least one (preferably three) stool sample(s) should be taken, including specific requests for evaluation of parasites. For patients who are unwell, particularly those with fevers or dysentery, initiation of empirical antibiotic treatment with azithromycin or a quinolone may be needed while awaiting results. For those with prolonged symptoms, tinidazole as empirical therapy for protozoan parasites may be considered. Endoscopic evaluation may also be advisable if no infectious cause is found and symptoms do not resolve.

- Travellers’ diarrhoea continues to affect 20–50% of people undertaking trips to areas with under-developed sanitation and there is minimal evidence for beneficial effects of dietary precautions.

- Evidence for the benefit of cholera vaccine in reducing TD is limited, but it can be considered in people at high risk of infection.

- In 50–80% of TD cases, TD is caused by bacterial infection. Mild diarrhoea can be managed with an antimotility agent (loperamide) alone, but for moderate or severe diarrhoea, early self-treatment with loperamide in conjunction with antibiotics is advised.

- Recommended empirical antibiotics are fluoroquinolones (norfloxacin / ciprofloxacin) or azithromycin for up to 3 days, although in the setting of increasing resistance, the latter is preferred for travellers to South and South-East Asia.

Competing interests: Karin Leader received a consultancy fee from Imuron in relation to the C. difficile vaccine. She is also an ISTM board member and received a consultancy from ISTM to join the GeoSentinel leadership team. She received grants from Sanofi to develop a mobile phone app for splenectomised patients and from GSK to research the use of the HBV vaccine. GSK also paid her to lecture on travel risks at the Asia Pacific Travel Health Conference. She has received support from both GSK and Sanofi to attend travel medicine conferences.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed

- Diemert DJ. Prevention and self-treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Prim Care 2002;29:843–55. Search PubMed

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Travelers’ Diarrhea. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/travelersdiarrhea_g.htm [Accessed 25 November 2014]. Search PubMed

- Paredes-Paredes M, Flores-Figueroa J, Dupont HL. Advances in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2011;13:402–07. Search PubMed

- DuPont HL, Ericsson CD, Farthing MJ, et al. Expert review of the evidence base for prevention of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med 2009;16:149–60. Search PubMed

- Nair D. Travelers’ diarrhea: prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation. J Fam Pract 2013;62:356–61. Search PubMed

- De Bruyn G, Hahn S, Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000:CD002242. Search PubMed

- Riddle MS, Arnold S, Tribble DR. Effect of adjunctive loperamide in combination with antibiotics on treatment outcomes in traveler’s diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1007–14. Search PubMed