- Buyer’s Guide

- Gear Reviews

- Rides+Events

- Training Guide

- Maintenance

A deep dive into the history of motor doping in cycling

The issue of technological cheating continues to dominate discussions in the sport.

Over the years, rumours of motorized cheating in cycling have abounded. One of the first suspected cases of mechanical doping dates back to the 2010 Tour of Flanders. That was where Fabian Cancellara’s unorthodox seated attack on the steep Kapelmuur led to accusations of an electric motor hidden in his bike .

The controversy resurfaced in the 2014 Vuelta a España. Ryder Hesjedal faced allegations of mechanical doping after a crash on Stage 7. Video footage showed his bicycle’s rear wheel persistently spinning even after it had fallen to the ground.

Afterward, the Canadian vehemently denied the accusation, saying it was simply not possible .

The origins of testing

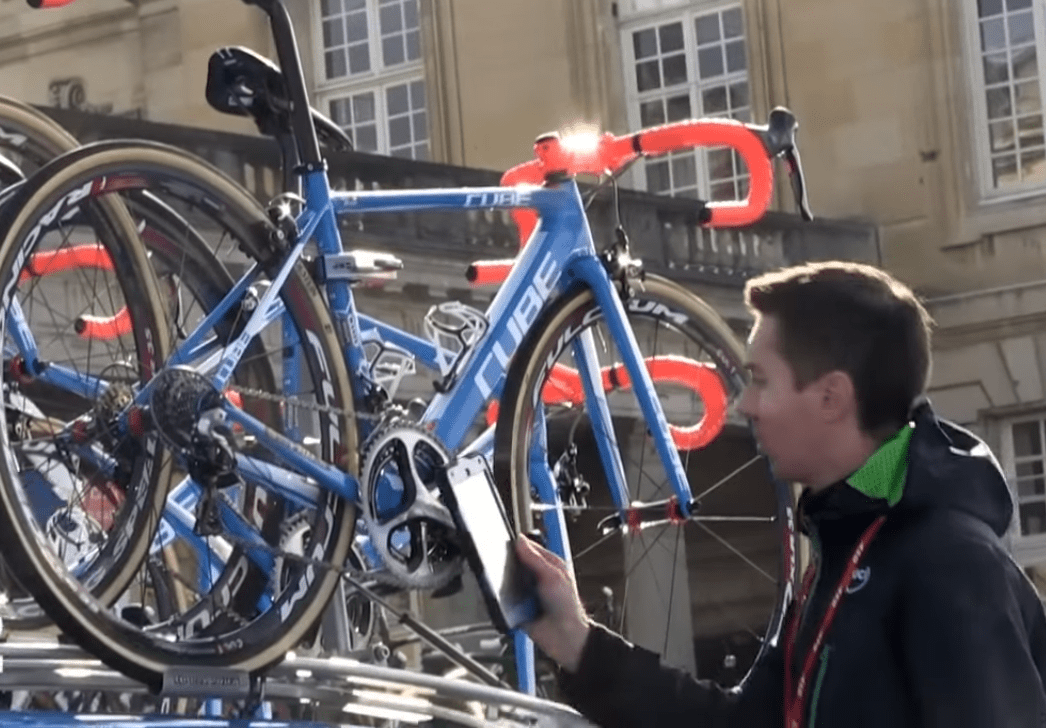

Testing for motors came into focus as the UCI succumbed to public pressure, leading race commissaires to thoroughly inspect the bicycles of Hesjedal’s Garmin–Sharp team the following day. Despite the scrutiny, no motors were found. Subsequently, in the following spring, bike motor inspections became a regular practice at prestigious events such as Paris–Nice, Milan–San Remo, and the Giro d’Italia, using tablets.

The French and Italian exposés in 2016

In 2016, the French television show Stade 2 asserted that the prevalence of mechanical doping was potentially higher than previously thought, and it was going unnoticed by the UCI. Conducting an investigation with a costly thermal camera cleverly disguised as a standard video camera, the program recorded footage during the Strade Bianche and the Coppi e Bartali stage race. In a 20-minute segment, the show presented a persuasive argument, suggesting that they had indeed captured evidence of mechanized doping.

According to a report in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera in the same year, the television program identified seven instances of mechanized doping using the thermal camera. In five cases, heat in the bottom bracket was detected, suggesting a motor assisting the crank. In two other instances, heightened heat was observed in the rear-wheel’s hub or cassette. Consulting a thermal imagery specialist, the program received confirmation that the captured images were suspicious. The footage indicates an abnormal amount of heat in bike areas that shouldn’t generate heat.

There has been speculation over the years that Lance Armstrong might have used a motor in his bike. Observers noted his habit of tugging at the back of his shorts during races. That prompted some to wonder if he was activating a hidden mechanism. Armstrong vehemently denied any involvement in motor doping, stating in a Cycling Weekly article, “In 1999, no one even knew you could put a motor in a bike.” The former pro cyclist explained that at the time he would adjust his shorts such that the chamois was centred on his saddle. He believed it would help his pedalling efficiency.

The Sepp Kuss accusation

In September, former pro Jérôme Pineau spoke out about American Sepp Kuss’s attack on the Tourmalet during the 2023 Vuelta a España: “The international bodies are destroying cycling. They let too many things happen, don’t control anything anymore and do what the big teams want. That is the big danger. So then you can start thinking what you want,” he begins. “We see the pictures…I am not talking about doping, but about something that is even worse.”

“Mechanical doping? Yes, mechanical,” he continued. “If you watch Sepp Kuss’s attack on the Col du Tourmalet, against riders like Juan Ayuso, Cian Uijtdebroeks–-who is a great talent–-and Marc Soler. They’re not so slow on bikes, are they? Kuss rides ten kilometres per hour faster with his attack, then has to slow down because of a spectator and then rides ten kilometres per hour faster after.”

Jumbo-Visma DS claps back about motor doping claims

A few days after the accusation, Kuss said that he was completely against any sort of doping, whether by PED or motor. “I think for me personally, cheating or doping is just out of the question. Because it’s not even sports for me then,” Kuss said to GCN . “Part of sports is losing. Of course you want to win, but if you’re doing something that’s prohibited or cheating, then you’re afraid of losing, which I think is one of the most important things about sports: accepting that sometimes you’re not good enough. That’s just how it is.”

The 2016 cyclocross worlds

Belgian Femke Van den Driessche was caught utilizing motor doping. During the 2016 ‘cross worlds, the UCI discovered a motor in one of her spare bikes . She claimed it was a friend’s bike mistakenly placed there and denied any intention to cheat. “That bike belongs to a friend of mine. He trains with us. He joined my brothers and my father. That friend joined my brother at the reconnaissance, and he placed the bike against the truck, but it’s identical to mine,” she said. Last year he bought it from me. My mechanic cleaned the bike and put it in the truck. They must’ve thought that it was my bike. I don’t know how it happened.”

At the time, by the way, her brother Niels was currently serving a suspension for doping.(He and their father were also accused of stealing expensive parakeets, but that’s a whole other story.)

The pre-testing period

This incident resulted in increased vigilance and regular checks. According to the podcast “Ghost in the Machine,” which focuses on technological fraud, and more specifically, Van den Driessche, there was not a rigorous testing protocol in place for several years prior to this. Brian Cookson was the former president of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), serving from 2013 to 2017.

Motor doping may have happened at UCI WorldTour competitions before 2014: official

Toward the end of his tenure, the issue of motor doping gained prominence. The UCI took measures to address the concerns related to technological fraud in cycling. Brian Cookson, as the head of the UCI, emphasized the importance of tackling motor doping and implementing measures to ensure fair play in the sport. The UCI introduced various technological methods and protocols to detect the presence of hidden motors in bicycles, including thermal imaging and magnetic resonance testing.

Questioning the robustness of the testing

Despite the UCI’s assertions of implementing comprehensive mechanical doping tests at all UCI WorldTour and UCI Women’s WorldTour events, a September investigation by the RadioCycling podcast exposed significant inconsistencies and deficiencies in these efforts . A crucial finding from the report reveals the omission of technological fraud tests during four out of the 21 stages of the recent Giro d’Italia, including the critical time trials on Stages 1 and 10.

Equally alarming was the absence of the essential X-ray technology designed for detecting mechanical doping during the opening Grand Tour of the 2023 season. The Tour de France also lacked X-ray tests on Stage 21 in Paris. These lapses were not confined to the Grand Tours alone but extend to other competitions. That included the Volta a Catalunya, the Tour of Scandinavia, and the Tour Down Under. Another concerning aspect highlighted in the investigation is the lack of data sharing. Paris-Nice witnessed the absence of testing on stages 5, 7, and 8, while Milan-San Remo and significant women’s races such as Paris-Roubaix and Flèche Wallonne experienced limited controls due to inadequate testing measures.

UCI still skeptical about usage

In light of these deficiencies, senior UCI officials expressed skepticism about the potential presence of concealed motors within the peloton, raising questions about the credibility of professional cycling. In an attempt to address these concerns, RadioCycling gathered data from 51 men’s and women’s WorldTour races. Surprisingly, only 24 races provided data, 12 confirmed that the UCI had not disclosed any statistics. 15 remained unresponsive.

The UCI defended its program against technological fraud in a statement to RadioCycling: “The UCI’s program against technological fraud has developed steadily over the years and provides a robust system for the detection of any possible propulsion systems hidden within framesets or other bike components,” it read. “In 2023, a total of 4,280 controls were performed. Magnetic tablets were used for 3,777 of the controls and X-ray technology. All tests were negative.”

There have been plenty of cases of amateurs being accused or caught for this form of cheating, it should be noted. And there have been suggestions by Italian media that if any form of motor doping exists, it is not necessarily with a motor in the down tube, but could be using ectromagnetic wheels.

Former Tour de France winner Greg LeMond has often spoken out about his views about motor doping, saying in road.cc in 2017, “I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France.”

2021 allegations about motor doping using wheels

In 2021, an article published in Le Temps suggested some riders had heard “strange noises” coming the bikes of four teams. They: Team UAE-Emirates, Deceuninck-QuickStep, Jumbo-Visma and Bahrain Victorious.

When yellow jersey Tadej Pogačar was asked, he was shocked at the question.

“I don’t know. We don’t hear any noise. in disbelief at what he was being asked. “We don’t use anything illegal. It’s all Campagnolo materials, Bora,” he said. “I don’t know what to say.”

The article said that one of the riders believed the noise was coming from the rear wheels. “A strange metallic noise. Like an incorrectly adjusted chain,” the unnamed cyclist said. I’ve never heard it anywhere.”

“We are no longer talking about a motor in the crankset or an electromagnet system in the rims of the wheels, but a device hidden in the hub,” another unnamed source said . “We are also talking about a recuperator of the wheels. Energy is sent via the brakes. Inertia is stored just as in Formula 1.”

However, to this date, only Van den Driessche has ever been caught for technological fraud.

- Email address: *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

UCI finds no evidence of mechanical doping at the Tour de France

'The objective is to eliminate suspicion' says Lappartient

The Union Cycliste International (UCI) has confirmed it carried out a multitude of tests for mechanical doping at the Tour de France , including 164 X-ray tests of race bikes, with all the tests negative.

Mechanical doping: A brief history

Mechanical doping: Voeckler 'wouldn't be shocked' if Lance Armstrong had used a motor

UCI introduces mobile X-rays and thermal imaging cameras to fight mechanical doping

UCI confirms Chris Froome's bike X-rayed for mechanical doping after Giro d'Italia solo win

X-rays, thermal cameras, bike tags part of fight against mechanical doping at Tour de France

The UCI was forced to step up its fight against mechanical doping after French television raised doubts about the validity of the tablet device that was first introduced by former UCI president Brian Cookson when a rudimentary motor was discovered during the 2016 Cyclo-cross World Championships in a the bike of Belgian U23 racer Femke Van den Driessche. She was later banned for six years. The latest advances in mechanical doping are believed to include electromagnetic wheels.

In March, new UCI president David Lappartient announced the UCI had beefed up its strategy to fight mechanical doping, presenting a special mobile X-ray cabinet in Geneva and promising that thermal imaging cameras will also be used. The UCI also introduced a VAR (Video Assist Referee) that studies all the television images of a race that helps the UCI race judges spot any suspicious bike or wheel changes.

"The Union Cycliste Internationale can today confirm that it carried out rigorous testing during the 2018 Tour de France as part of the fight against technological fraud," the UCI said in a press release on Monday. "The tests were carried out using different technologies – magnetic scanning, X-rays and thermal imaging – before, during and after the stages, throughout the three weeks of competition. Every one of these tests came back negative."

Over the three weeks of racing, 2,852 total tests were carried out - at the start of all 21 stages - using magnetic scanning technology, a method introduced by the UCI for the first time at the Tour de France in 2016.

At the end of stages, 164 tests were carried out using X-ray technology. Between five and 10 bikes were tested at each stage, including those of the stage winner and the yellow jersey holder. Further tests were carried out during the stages using thermal imaging cameras."

Cyclingnews observed the testing during the Tour de France and spoke to new head of UCI Equipment Christophe Péraud, who finished second to Vincenzo Nibali in the 2014 Tour de France. The X-ray testing was done with the UCI's specially created mobile unit parked in the protected anti-doping compound near the finish line. Many of bikes tested belonged to the riders selected for anti-doping controls. A special motorbike carrying a manually operated thermal camera was occasionally seen checking riders for mechanical doping during the racing.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The UCI revealed that it began testing a tracker device that can supposedly detect the magnetic fields created by hidden motors. That programme has been created with the Department of Technological Research at CEA Tech (the French Atomic and Alternative Energies Commission).

The eventual aim is to develop a 'tracker' that can be placed on all bikes in the peloton. The first test phase, carried out at the Tour de France in collaboration with several teams, involved detecting magnetic signals.

"I would like to congratulate my UCI colleagues and the UCI Commissaires for their effort and involvement over the last three weeks, during which time an enormous number of bikes have been tested," Lappartient said.

"The objective is to eliminate suspicion and to show the public and all of cycling's stakeholders, including investors, that our sport is credible. We will continue to work in this regard, to ensure that cycling's positive reputation is guaranteed."

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The current GC standings at the Giro d'Italia

‘If I tried to follow Pogačar I’d blow up’ – Geraint Thomas limits damage at Giro d’Italia

‘I’ll try not to make that mistake again’ – Ben O’Connor pays price for Pogačar pursuit at Giro d’Italia

Most Popular

The UCI reveals its programme to combat doping and technological fraud for the 2023 Tour de France

The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) today reveals its programme to combat anti-doping and technological fraud that it will implement for the upcoming Tour de France (1-23 July).

The comprehensive anti-doping programme deployed at the French Grand Tour will be led by the International Testing Agency (ITA), the body to which the UCI delegated the operational activities of its fight for clean cycling in 2021. After ensuring a level playing field for all participants at the Giro d'Italia last May, the ITA will once again work with all stakeholders, including the French authorities, to protect the integrity of one of the world's most prestigious cycling events.

This will be the third time that the ITA has taken charge of the anti-doping programme at the Tour de France since the UCI delegated its anti-doping activities to the agency. Within this framework, the ITA is in charge of the overall anti-doping strategy, which includes the definition of a precise and targeted testing plan. This plan is applied on the basis of a risk assessment that takes into account a wide variety of relevant factors whilst constantly adapting to current circumstances or new information. The testing plan also considers any relevant information received through the monitoring of the athletes’ Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) or gathered by the ITA’s Intelligence & Investigations Department.

All doping controls at the Tour de France will be targeted and performed at any time throughout the three-week race, not only at the finish line. At every stage, the yellow jersey and stage winner will be tested. Additionally, all athletes will already be tested before the start of the event as part of their medical monitoring. At the end of the race, the ITA will make a selection of samples that will be kept for potential re-analysis over the next 10 years.

Doping controls will mainly be conducted by the ITA’s Doping Control Officers (DCOs) with in-depth cycling experience. The ITA is also in close contact with other relevant French and international actors, for example with authorities, for support and exchange of information.

It should be remembered that 2023 has seen a significant increase in funding for cycling’s anti-doping programme . The UCI, UCI WorldTeams, UCI ProTeams, UCI WorldTour organisers and men’s professional road cyclists decided to further strengthen the capacity of the ITA to protect the integrity of the sport thanks to a progressive 35% budget increase up until the end of 2024. This funding principally reinforces the areas of Intelligence & Investigations, testing, scientific analysis, data analysis, long-term sample storage and sample re-analysis.

The Director General of the ITA Benjamin Cohen said: “We are looking forward to delivering the anti-doping programme for this major cycling race for the third time under the responsibility of the ITA and in collaboration with our partners to ensure a level playing field during the event. As the testing operations for this event are already at a vigorous level, the additional resources stemming from the decision of the cycling stakeholders to further protect the sport from doping will allow us to step up in other relevant areas of the clean sport programme for the Tour de France and throughout the year. Most notably, it allows us to invest more in intelligence and investigations, an area that has proven to be very effective and complementary to the testing regime. We are steadfast in our commitment to ensure a clean and fair competition environment for all participants in this highly anticipated event.”

When it comes to the fight against technological fraud at the Tour de France, controls for the presence of any possible propulsion systems hidden in tubes and other bike components will be carried out with the use of three tools: magnetic tablets, mobile X-Ray cabinet and portable devices using backscatter and transmission technologies.

Before each of the 21 stages, a UCI Technical Commissaire will be at the team buses to check all bikes being ridden at the start of that day’s stage. These pre-stage checks will be carried out using magnetic tablets.

After each stage , checks will be carried out on bikes ridden by:

the stage winner

riders wearing a leader’s jersey (yellow, green, polka dot, white)

three to four randomly-selected riders

riders who give rise to suspicion, for example following the pre-stage scan, an abnormally high number of bike changes (in which case the bikes on the team car can also be checked) or other incidents picked up by the UCI Video Commissaire

These post-stage checks will be carried out using either mobile X-Ray technology or devices that use backscatter and transmission technologies. If necessary, the bike in question will be dismantled.

Once the riders have crossed the finish line, the bikes subject to post-stage checks will be quickly tagged, enabling rapid control procedures to be carried out in a matter of minutes. The introduction of RFID tagging (tamper-proof tags using radio frequency identification technology) for all bicycles as part of the UCI Road Equipment Registration Procedure for the 2023 Tour de France and Tour de France Women with Zwift strengthens the UCI's ability to monitor the use of bicycles throughout the stages.

As a reminder, the mobile X-Ray technology, which is safe for users and riders, provides high resolution X-Ray image of a complete bike in just five minutes. Meanwhile the backscatter and transmission technology provides instantaneous high resolution images of the interior of the sections examined that can be transmitted, remotely, directly to the UCI Commissaires.

For road cycling, the UCI carries out bike checks at all UCI WorldTour events, as well as the UCI Road World Championships, UCI Para-cycling Road World Championships, UCI Para-cycling Road World Cup, UCI Women’s WorldTour events and the Olympic Games. Controls are also carried out at UCI World Championships for mountain bike, cyclo-cross and track as well as the UCI Cyclo-cross World Cup.

At last year’s Tour de France, a total of 934 bike checks were carried out and no cases of technological fraud were detected.

UCI Director General Amina Lanaya said: "The UCI continues to take the possibility of technological fraud very seriously. Our range of tools to combat all forms of cheating using a motor enables us to carry out rapid and effective checks. With the introduction of RFID tags on all the bikes, the UCI has the ability to monitor the use of the bikes during the race. This is essential to guarantee the fairness of cycling competitions and to protect the integrity of the sport and its athletes."

Watch CBS News

60 Minutes investigates hidden motors and pro cycling

By Bill Whitaker

January 29, 2017 / 7:04 PM EST / CBS News

The following script is from “Enhancing the Bike,” which aired on Jan. 29, 2017. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent. Michael Rey and Oriana Zill de Granados, producers.

The sport of cycling is notorious for its culture of cheating—made most famous by the rise and fall of Lance Armstrong and his use of performance-enhancing drugs. Now when cycling hopes to be cleansed of the dopers there’s a surprising new twist—riders enhancing the bike’s performance. Some professional racers aren’t putting steroids and blood boosters in their veins they’re hiding motors in their bike frames. We followed a lead to Budapest, Hungary, and met an engineer who said he built the first secret bike motor back in 1998. And he told us motors have been used in the Tour de France. Our story tonight is not about the latest drugs the riders are using to cheat…it’s all about enhancing the bike.

Bill Whitaker: Where is the motor in here?

Stefano Varjas: It’s in here.

In a bike shop in Budapest, Hungary, we met Istvan Varjas. Stefano, as he’s known, is a former cyclist, a businessman and a scientist. His most important invention he placed inside this bike. The frame is fitted with a small motor he designed. Add to it a lithium battery that powers it and a secret button that he installed.

Stefano Varjas: This is first speed.

Bill Whitaker: Uh. Huh.

Stefano Varjas: Try to keep the pace.

Bill Whitaker: Wow!

The sound is mostly the chain and the wheels. He said you can’t hear it on the road and all of his motor designs use brushless motors and military-grade metal alloys.

Bill Whitaker: And how does this work?

This is now the latest version of his hidden motor design.

Bill Whitaker: Unbelievable…

It can be connected to a heart rate monitor by remote control. When a riders heart beat gets too high it sends a signal for the motor to kick in.

We took his hidden motors for some test rides up in the hills above Budapest.

Bill Whitaker: This is like I’m on flat ground.

It was hard to believe it’s real until I put my feet on the pedals. Harder to believe when I took them off the pedals…

Bill Whitaker: “Hello.”

And still beat the local talent. As you can tell it’s not like a moped. There’s no exhaust pipe or revving engine noise. It’s designed to give a short but powerful boost to the rider’s own effort.

Bill Whitaker: So this is a lower gear or a higher gear?

Stefano Varjas sells complete motorized bikes to wealthy recreational riders for about $20,000. But we went to Budapest to find out who else might have bought a silent, hidden motor for a racing bike.

Bill Whitaker: Do you know, are professionals using bikes like these on a professional tour?

Stefano Varjas: This one, no. This on --

Bill Whitaker: But bikes with motors?

Stefano Varjas: Yes. I know-- I know this.

Bill Whitaker: They are?

Stefano Varjas: They use, yes.

Suspicions of hidden motors are fueled by videos of riders crashing in races. This bike seems to move by itself without the rider.

And the first time anyone suspected they were looking at a motor was in 2010 when a famed Swiss racer sped ahead of the pack at unnatural speeds.

These riders all denied they were using motors and no one had ever been caught until last year. Race officials suspended this Belgian rider after they found a motor inside her spare bike.

Jean-Pierre Verdy is the former testing director for the French Anti-Doping Agency who investigated doping in the Tour de France for 20 years.

Bill Whitaker: Have there been motors used in the Tour de France?

Jean-Pierre Verdy: Yes, of course. It’s been the last three to four years when I was told about the use of the motors. And in 2014, they told me there are motors. And they told me, there’s a problem. By 2015, everyone was complaining and I said, something’s got to be done.

Verdy said he’s been disturbed by how fast some riders are going up the mountains. As a doping investigator, he relied for years on informants among the team managers and racers in the peloton, the word for the pack of riders. These people told Jean-Pierre Verdy that about 12 racers used motors in the 2015 Tour de France.

Bill Whitaker: The bikers who use motors, what do you think of them and what they’re doing to cycling?

Jean-Pierre Verdy:They’re hurting their sport. But human nature is like that. Man has always tried to find that magic potion.

He now thinks that magic potion is a motor like the one designed by Stefano Varjas.

Bill Whitaker: Are you selling your motors to pro peloton now?

Stefano Varjas: Never, ever.

Bill Whitaker: Never, ever?

Stefano Varjas: Never, ever. But I don’t know, if a grandfather came and buy a bike and after it’s go to finishing his grandson who is racing, it’s not my problem.

Bill Whitaker: It sounds like plausible deniability, which means my fingerprints aren’t on this when it ends up in the bike of a professional. I just sold it to a client. What the client did with it--

Stefano Varjas: Is their problem.

Bill Whitaker: --I don’t know--

Stefano Varjas: It’s not my problem.

Bill Whitaker: So if someone came to you and said directly, “I wanna use your invention to cheat. I’ll pay you a lot of money for it,” would you sell it to them?

Stefano Varjas: If the money is big, why not?

He said he got his first big money in 1998 when a friend saw his hidden motor prototype and thought he could sell it to a professional racer.

Bill Whitaker: So your friend said, “With all this doping going on, you’re-- you’re crazy not to try to sell your invention--”

Stefano Varjas: Exactly. And--

Bill Whitaker: “--to these professional--”

Stefano Varjas: He proposed me--

Bill Whitaker: “--racers”?

Stefano Varjas: He proposed me, “Give me this bike and I fix it up, your life.” And it’s happened.

He told us his friend found a buyer in 1998 and Stefano swears he has no idea who it was. He gave us this bank record that shows that he had about $2 million at the time. We also know that he spent time in jail for not paying a substantial tax bill in Hungary. He said whoever paid him all that money wanted an exclusive deal—he couldn’t work on the motor, sell it or talk about it for 10 years.

Bill Whitaker: And you were OK with that?

Stefano Varjas: For 10 years. $2 millions-- if you are in Hungary, if you live in Hungary, if you-- they offer you $2 million to don’t do nothing--

Bill Whitaker: You couldn’t refuse it?

Stefano Varjas: Can you refuse it? I don’t think.

Bill Whitaker: So you believe that hidden motors have been used by professional cyclists since as far back as 1998?

Stefano Varjas: I think, yes.

In France, where cycling is a religion, the newspaper Le Monde said this past December that the timeline of Stefano’s story might implicate Lance Amstrong. Armstrong won his first of seven Tour de France victories in 1999, just a year after Stefano Varjas’ said he sold his first motor. Armstrong denied to the paper ever meeting Stefano in person or putting a motor in his bike.

We asked Armstrong too through his lawyer and he denied ever using a motor and declined an interview.

We contacted Armstrong’s former teammate Tyler Hamilton who has admitted to being part of all the chemical doping by members of the U.S. Postal team. And Tyler told us he never knew of any motors on the team back then.

In order to demonstrate the motors existed as far back as 1998, Stefano Varjas suggested to us that we find a carbon fiber 1999 U.S. Postal Service team bike, the same bike the U.S. Postal team used in the 1999 Tour de France. We bought this bike off the Internet and he installed a motor based on his first design into the bike. He charged us $12,000, saying that covered his costs for the parts and labor.

We then asked Hamilton to test out the bike.

Bill Whitaker: You could feel the difference?

Tyler Hamilton: Oh yeah, oh, yeah. It’s not super obvious. You know, you-- all of a sudden, you’re just like, “Ah.”

Bill Whitaker: It seems easier?

Tyler Hamilton: It feels a little bit smoother, yeah. Yeah.

Bill Whitaker: So you could see how somebody could get away with it?

Tyler Hamilton: I could see how teams are doing it. Yeah. I could.

The motor gives a limited boost of power for about 20 minutes. Tyler Hamilton said that much motorized assistance during a race on a mountain road could be a game changer for a professional rider.

Bill Whitaker: What kind of benefit could this motor give a cyclist?

Tyler Hamilton: That’s the difference between winning and losing for sure. For sure.

“I guess we shoulda known this was coming, you know? ‘Cause, I mean, there’s more pressure in today’s cycling world than ever to win.” Tyler Hamilton

Few riders know that better than Tyler Hamilton. When he spoke to 60 Minutes in 2011 , he was one of the first to talk openly about chemical doping in the sport. He said riders have always looked for ways to stay ahead of the authorities.

Tyler Hamilton: They’d find-- you know, for a while, they didn’t have an EPO test. EPO increases your red blood cell production. When the new tests came out, you’d figure out new ways around them.

Tyler Hamilton: I guess we shoulda known this was coming, you know? ‘Cause, I mean, there’s more pressure in today’s cycling world than ever to win.

During this car ride in Hungary with Stefano Varjas we listened as he talked on the phone with one of his clients about delivering some new motorized bikes. He said he was speaking to this man, Dr. Michele Ferrari. Ferrari is the man behind the doping programs of Lance Armstrong and other top cyclists. He has been banned from the sport of cycling.

Still Stefano Varjas told us that Ferrari bought bikes with hidden motors in the past three years. We spoke to Dr. Ferrari by phone and he denied buying motorized bikes from Stefano but said he has tested one.

Three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond and his wife Kathy first learned about hidden motors in 2014 when Greg met Stefano Varjas in Paris and took a test ride. Greg was outspoken about chemical doping and now has the same level of concern about the motors.

Greg LeMond: I’ve watched-- last couple years-- and I’m going I know the motor’s still in the sport and--

Bill Whitaker: You know it is still in the sport?

Greg LeMond: Yeah. Yeah. There’s always a few bad apples and-- because it’s a lotta money.

He is so concerned about it that while working as a broadcaster at the Tour de France he and his wife worked secretly with the French police investigating the motors. His best source it turns out was Stefano Varjas.

Kathy LeMond: I asked Stefano if he would please come and talk to the French police.

Bill Whitaker: Did he? Is he cooperating with the police?

Kathy LeMond: Completely.

Stefano said he told the French police that just before the 2015 Tour de France he again sold motorized bikes to an unknown client through a middleman. He said he was directed to deliver the bikes to a locked storage room in the town of Beaulieu Sur Mer, France.

Stefano Varjas told us that in addition to the motors in the bike frames, he’s designed a motor that can be hidden inside the hub of the back wheel seen here in a video he gave us.

Kathy LeMond: Stefano had said, “Weigh the wheels. You’ll find the wheels. The wheels are in the peloton.”

According to Varjas the enhanced wheels weigh about 800 grams—or 1.7 pounds more than normal wheels.

Bill Whitaker: You could detect it by weight?

Greg LeMond: Yeah. Cycling weight is everything. Your body, your bike. If your bike weighs a kilo more, you would never race on it.

“This is curable. This is fixable. I don’t trust it until they figure out how to take the motor out. I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France.” Greg LeMond

In the 2015 Tour de France, bikes in the peloton were weighed before one of the time trial stages. French authorities told us the British Team Sky was the only team with bikes heavier than the rest—each bike weighed about 800 grams more. A spokesman for Team Sky said that during a time trial stage bikes might be heavier to allow for better aerodynamic performance. He said the team has never used mechanical assistance and that the bikes were checked and cleared by the sports governing body.

A heavy bike doesn’t prove anything on its own but to Greg LeMond the weight difference should have set off alarm bells. In this case, sources told us, the sport’s governing body would not allow French investigators to remove the Team Sky wheels and weigh them separately to determine if the wheels were enhanced. LeMond said not enough is being done by the International Cycling Union to prevent cheating with motors.

Greg LeMond: This is curable. This is fixable. I don’t trust it until they figure out how to take the motor out. I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France.

Bill Whitaker is an award-winning journalist and 60 Minutes correspondent who has covered major news stories, domestically and across the globe, for more than four decades with CBS News.

More from CBS News

The inspiration for New Orleans' St. Mary's Academy

Can workers prosper with employee ownership?

Leader Hakeem Jeffries on Israel, House Republicans and the election

Democrat leader Jeffries: "Pro-Putin faction" in GOP delayed Ukraine aid

- off.road.cc

- Dealclincher

- Fantasy Cycling

Support road.cc

Like this site? Help us to make it better.

- Sportive and endurance bikes

- Gravel and adventure bikes

- Urban and hybrid bikes

- Touring bikes

- Cyclocross bikes

- Electric bikes

- Folding bikes

- Fixed & singlespeed bikes

- Children's bikes

- Time trial bikes

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Child seats

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Arm & leg warmers

- Base layers

- Gloves - full finger

- Gloves - mitts

- Jerseys - casual

- Jerseys - long sleeve

- Jerseys - short sleeve

- Shorts & 3/4s

- Tights & longs

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Gear levers & shifters

- Handlebars & extensions

- Inner tubes

- Quick releases & skewers

- Energy & recovery bars

- Energy & recovery drinks

- Energy & recovery gels

- Heart rate monitors

- Hydration products

- Hydration systems

- Indoor trainers

- Power measurement

- Skincare & embrocation

- Training - misc

- Cleaning products

- Lubrication

- Tools - multitools

- Tools - Portable

- Tools - workshop

- Books, Maps & DVDs

- Camping and outdoor equipment

- Gifts & misc

Mechanical doping: “I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France,” says Greg LeMond

Three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond says he does not trust recent results in cycling’s biggest race because he believes riders are cheating by using concealed motors. A Hungarian engineer behind the technology claims that he sold exclusive ten-year rights to his invention for almost $2 million in 1998 – but he has not named the buyer.

Both men were speaking as part of a CBS 60 Minutes documentary that will be screened on primetime television in the United States on Sunday evening.

The show airs on the same weekend as the UCI Cyclo-cross World Championships in Luxembourg and it was at last year’s event in Zolder, Belgium, where a hidden motor was discovered in competition for the first time.

It was found on a bike prepared for Belgian Under-23 rider Femke Van Den Driessche, who has since been banned for six years and fined 20,000 Swiss Francs for what the UCI classifies as “technological fraud.”

Since then, the UCI has stepped up efforts to detect concealed motors, carrying out thousands of tests at races last year using a tablet-based application it has developed that seeks to detect electromagnetic waves.

At the Tour de France last summer, x-ray machines and thermal imaging equipment on loan from the French military were also used to try and detect hidden motors.

LeMond, now aged 55 and winner of the Tour de France in 1986, 1989 and 1990, strongly suspects that concealed motors are still in use in the peloton, however. He told the programme: “This is curable. This is fixable. I don’t trust it until they figure out how to take the motor out.

“I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France,” he added.

Budapest-based engineer Istvan Varjas is likewise convinced that motors concealed within frames similar to those he developed, as well as ones hidden within rear wheels, are being used at the top level of the sport.

He told 60 Minutes that with a friend acting as intermediary, a friend put him in touch with an anonymous prospective purchaser who offered him close to $2 million for exclusive, 10-year rights to the technology.

Varjas, who has previously appeared on French television on the subject of mechanical doping, accepted the money and agreed he would not talk about hidden motors nor engage in developing them until the period of exclusivity had expired.

He sought to distance himself from those who might use the technology to gain an unfair advantage in a race, telling 60 Minutes: “If a grandfather came and buy a bike and after it’s go to his grandson who is racing, it’s not my problem.”

But pressed whether he would supply a concealed motor to someone who revealed he would use it to try and win races, he answered: “If the money is big, why not?”

60 Minutes also spoke to a former testing director of France’s national anti-doping agency, the AFLD, Jean-Pierre Verdy, who revealed that he believes hidden motors are an issue in the professional ranks.

He said: “It’s been the last three to four years when I was told about the use of the motors.

“There’s a problem. By 2015, everyone was complaining and I said, ‘something’s got to be done.’”

Since the seven successive victories between 1999 and 2005 that Lance Armstrong was stripped of five years ago, eight men have won the race, and it’s those victories, presumably, that LeMond is questioning.

Oscar Pereiro and Andy Schleck were awarded the 2006 and 2010 wins respectively after Floyd Landis and Alberto Contador were convicted of doping.

Contador himself won in 2007 and 2009, with Carlos Sastre taking the victory in the intervening year.

The 2011 win went to Cadel Evans, before Team Sky began their domination of the race, with victories for Sir Bradley Wiggins in 2012 and Chris Froome in three of the past four seasons.

In 2014, the yellow jersey was won by Vincenzo Nibali, who joined Contador as the only current riders to have won all three Grand Tours.

However, it was not at the Tour de France but during the Spring Classics in 2010 that the issue of whether professional cyclists might be gaining illegal mechanical assistance first hit the headlines.

That year at the Tour of Flanders, Fabian Cancellara rode away with ease from rival and home favourite Tom Boonen on the Muur van Geraardsbergen, and a week later he also won Paris-Roubaix.

Cancellara has always denied cheating, although shortly afterwards ex-professional cyclist turned television commentator Davide Cassani, now coach to the Italian national team, demonstrated how he believed hidden motors could give riders a race-winning edge.

12 months on from the shock discovery of what remains the only concealed motor to have been found in competition, for many there is a nagging question that remains unanswered; if an Under-23 rider in the notoriously under-funded women’s side of the sport was using one, are we really expected to believe that no male elite rider has done so, given the huge financial stakes involved?

> Find all our coverage of mechanical doping here

Help us to fund our site

We’ve noticed you’re using an ad blocker. If you like road.cc, but you don’t like ads, please consider subscribing to the site to support us directly. As a subscriber you can read road.cc ad-free, from as little as £1.99.

If you don’t want to subscribe, please turn your ad blocker off. The revenue from adverts helps to fund our site.

Help us to bring you the best cycling content

If you’ve enjoyed this article, then please consider subscribing to road.cc from as little as £1.99. Our mission is to bring you all the news that’s relevant to you as a cyclist, independent reviews, impartial buying advice and more. Your subscription will help us to do more.

Simon joined road.cc as news editor in 2009 and is now the site’s community editor, acting as a link between the team producing the content and our readers. A law and languages graduate, published translator and former retail analyst, he has reported on issues as diverse as cycling-related court cases, anti-doping investigations, the latest developments in the bike industry and the sport’s biggest races. Now back in London full-time after 15 years living in Oxford and Cambridge, he loves cycling along the Thames but misses having his former riding buddy, Elodie the miniature schnauzer, in the basket in front of him.

Add new comment

34 comments.

I saw the show about the motors in the US over the weekend.... A couple of things if you didn't:

They said that the motor noise is not detectable when riding.

It's only for assisting for like 20 minutes max i.e. when going up hills.

It can automatically kick in depending on things like cadence, speed.

They showed someone in a race who crashed and the rear bike wheel was still going strong making the bike spin in circles on the ground well after the bike hit the pavement. Hmmmm.

I lost interest in pro biking with the drug scandals which are likely still going on and this is another nail in the coffin for me....

- Log in or register to post comments

Not very difficult to purchase and fit, even for the home mechanic, the Vivax Assist E-bike motor currently costs £2300 via Fat Birds:

http://www.fatbirds.co.uk/1777975/products/vivax-assist---the-e-bike-system.aspx?origin=pla&kwd=¤cy=GBP&gclid=Cj0KEQiAzsvEBRDEluzk96e4rqABEiQAezEOoBdwpffsbpT3WiRH3jCPq7-KllcQx7Rw7RuHhD0AB6AaAuAs8P8HAQ

"As I've said previously, when you can retrieve lost energy through wobble motion and the vibrations through the frame (both known methods for generating electricty) and use carbon fibre as a conduit for such energy and connect to micro motors in the rear hub that are the size and shape of normal 'needle' bearings it is entirely possible and would be virtually impossible to find.

Sure, the really small micro motors won't put much out but then if they're indetectable with the olde worlde tech they are currently using to check and not actually understand that micro motors exist (because they are looking for a relatively large heat source and size of kit then a couple of extra watts that are basically retrieved for free for the entire length of a race is well worth the risk"

I don't see why we wouldn't allow this, it's the riders that are creating the energy, why not put it back through the bike? Easier to amend the rules for something like this than run round trying to detect it...

OH, and this one shows the black bidon but it looks like a bidon. Neutral service maybe? Food?

Here's another photo:

Different bottle. So are we suggesting, as above, that he had it wired up at the team car? There are high res images aplenty so it should be possible to find ONE with a clear picture of the wireing if there is any

if you wanted to use that motor, it would be too obvious to loop the wire through the seat post - better to widen the bolt hole for the bottle cage, which would then leave you with the issue of securing the bottle cage itself - maybe using 3 zip ties? - that's how I'd do it!

"You can bet your bottom dollar that some nobby MAMILS have used the tech to claim their Golds in a sportive but it would never work on the pro tour. Never."

You say that but then again good old Sir Brad has been popping Hayfever and Asthma tablets like no tomorrow and that seems to have done him proud.

"The man was a superb athlete, one of the best cyclists of all time. I would tend to take his words seriously."

Nah he was just bitter that whatever he was on couldn't make him better than arguably the best cyclist of all time.

Yeah I think exposed wires is a canard. I certainly think it's possible motors have been used, even likely, but how widely - who knows?

Few thoughts.. Assuming genuine, who did this Hungarian dude sell his motor to for $2m? Individual rider? Team? Bike manufacturer? Other? Only a few individual riders would have been able to afford that. Would have had to involve others, including engineers? Did they share it with other riders? Hard to keep secret for twenty years. What sort of battery would have ran the motor in 1998? If this motor is so good why have electric bikes taken so long to come out? Everyone in the peleton would have eventually found out, so why was everyone doping?

I wasn't talking about the front what might be a wire but is the cage. The wires I refer to exit the top, runs down the left side of the bottle between the frame and the bottle and then doubles underneath.

Found some pictures of the TdF GoPro camera's... no external batteries visible in their set up. There's some pics of the AbuDabai set up for live race transmission but that is really obvious, not like this and something the organisors were only too happy to show off.

That bottle cage has 3 cable ties holding it on suggesting it needs a bit of bracing.

Not seen anything like this anywhere that didn't have an explanation for it and yet for this there is nothing.

MamilMan wrote: I wasn't talking about the front what might be a wire but is the cage. The wires I refer to exit the top, runs down the left side of the bottle between the frame and the bottle and then doubles underneath. Found some pictures of the TdF GoPro camera's... no external batteries visible in their set up. There's some pics of the AbuDabai set up for live race transmission but that is really obvious, not like this and something the organisors were only too happy to show off. That bottle cage has 3 cable ties holding it on suggesting it needs a bit of bracing. Not seen anything like this anywhere that didn't have an explanation for it and yet for this there is nothing.

You go to all that trouble to have a secret motor, then leave the cables exposed for all to see.....?

MamilMan wrote: That bottle cage has 3 cable ties holding it on suggesting it needs a bit of bracing.

whats in these bidon batteries then, uranium?

I think you are desperate to see something that's just not there.

In the 2016 Tour De France there was a day (stage 14) when Jeremy Roy (128) of FDJ was part of a break. He was filmed towards the end of his stint on this break with another rider. There was an electrical wire sticking out of his rear water bottle (which was a different bottle from the front one). It was visible for only a few seconds on the footage.

You could say that this could have been to power one of many devices on the bike but his groupset was powered from another visible battery on the down tube. A battery the size of a bidon would power his groupset for an entire season.

MamilMan wrote: In the 2016 Tour De France there was a day (stage 14) when Jeremy Roy (128) of FDJ was part of a break. He was filmed towards the end of his stint on this break with another rider. There was an electrical wire sticking out of his rear water bottle (which was a different bottle from the front one). It was visible for only a few seconds on the footage. You could say that this could have been to power one of many devices on the bike but his groupset was powered from another visible battery on the down tube. A battery the size of a bidon would power his groupset for an entire season.

There are also plenty of images from that stage where Roy has a completely different bidon in his rear cage, as well as plenty of video. He goes back to the team car for a chat and returns to the group with 107.1km to go.

Presumably the dropping back was so he could have this "battery bidon" plugged in in your view? Also worth mentioning that he did have GoPro on his bike, and that the "wire" looks more like, er, a bottle cage.

SC1990 wrote: ... the "wire" looks more like, er, a bottle cage.

Exactly what I thought when I saw that pic: if that's a wire, what's holding his bottle?

How ridiculous would it be to plug in a battery bottle that doesnt look like a water bottle mid race? It must be for the go pros.

I love Lemond but there's no way that a pro tour team is using motors. How many people would need to be in on the conspiracy?

Yes a small outfit like the cross girl could try it but not a big team. Just isn't going to happen. You can bet your bottom dollar that some nobby MAMILS have used the tech to claim their Golds in a sportive but it would never work on the pro tour. Never.

Poor old Greg. Always ready to jump on a conspiracy. Not that he was wrong about Lance but just seems happy to jump on anything that will keep him in the public eye. Demostrating the technology exists isn't the same as having proof of misuse in the pro peloton.

The 'hidden motor' in the heat map pic could be a Di2 battery, it's possible?

What is rarely mentioned in these articles, but stands out in my mind, is that any motor which has been tested and reported on has been very noisy, and so probably noticeable in use. Have there been any tests or reports of quiet motors?

There is no plausible deniability if caught using one. At the top level of the sport I do not think it will be an issue. However, further down the pecking order I wouldn't be surprised that certain sad sacks just couldn't resist a bit of extra assistance in an amateur sportive or triathlon event.

Mungecrundle wrote: There is no plausible deniability if caught using one. At the top level of the sport I do not think it will be an issue. However, further down the pecking order I wouldn't be surprised that certain sad sacks just couldn't resist a bit of extra assistance in an amateur sportive or triathlon event.

At top sport, I tend to agree. Given the recent revelations re Armstrong, various missed doping tests (e.g. Armitstead) and the TUEs fiasco (Wiggins et al), pro cycling in general is under the spotlight as never before and I can't imagine a pro team would risk such a black and white scenario.

Having said that, Armstrong DID manage to cover it up for a long time, as we've since found.

Given that amateur sportives/triathlons/etc are almost completely unregulated, so what if people are using motors? Rhetorical question. There's already a form of mechanical "doping" going on in the range of bikes being used - my Sunday best bike is going to give me a huge advantage over some other rider on a clapped out mountain bike, for a start. You'd have to be pretty desperate to beat your mates to spend £3k on a motor on top of the price of your bike, though, unless you really are challenging for the top few places.

I think where it really will be called into question will be the high-profile endurance records.

It beggars belief that professional teams would risk everything for this.

With PEDs, there may always be some doubt.

If a motor is found in a bike with a particular rider's name on, in the vicinity of the restricted area, there can be no defence.

It may have been done in the past, before all the headlines. Now there is awareness and screening, would any rider, mechanic, etc risk EVERYTHING for such an advantage?

dottigirl wrote: Now there is awareness and screening, would any rider, mechanic, etc risk EVERYTHING for such an advantage?

Why would Lemond be saying this....without suspicion? It beggars belief to imagine recent winners doing this. In the words of Victor Meldrew: "I Don't beliieeeve it!!"

Disappointed to hear LeMond speaking out like this - he's always seemed more balanced and less prone to hysteria than many.

So we know that the technology exists but so far they've found one hidden motor in a CX race. Does he honestly think that recent Tour winners have been using them?

jasecd wrote: Disappointed to hear LeMond speaking out like this - he's always seemed more balanced and less prone to hysteria than many. So we know that the technology exists but so far they've found one hidden motor in a CX race. Does he honestly think that recent Tour winners have been using them?

And yet Lemond was one of the most vocal against renowned cheats like Lance Armstrong, when every man and his dog was slagging him off for doing so. And to the detriment of his own bicycle company.

The man was a superb athlete, one of the best cyclists of all time. I would tend to take his words seriously.

Peowpeowpeowlasers wrote: jasecd wrote: Disappointed to hear LeMond speaking out like this - he's always seemed more balanced and less prone to hysteria than many. So we know that the technology exists but so far they've found one hidden motor in a CX race. Does he honestly think that recent Tour winners have been using them?

I fully agree with you - he was one of the best riders ever and I do take his words seriously, which is why I'm disappointed to hear him making what feels like a bit of an implausible statement.

I hope he's wrong and I don't look back in twenty years and realise how naive I was. If that's the case then my only interest in cycling will be riding my bike and not following the sport.

so where would one get a concealed motor of this standard.....asking for a friend

Latest Comments

As a motorbiker as well as cyclist, that side nod is how I greet other riders

I use Newton meters (sorry, US based) a lot at work, and I usually use the dot to make it clearer, N·m. I'll use N-m if I'm in a hurry. Otherwise...

Done the hammer experiment yet? How did it work out for you?

Boatsie, is that you?

£52 of sale price is so impressive, when you see some companies giving small %age of profits from sales to similar initiatives. Well done Galibier!

If drivers routinely get away with this then how the hell do MPs like this expect it to work for bikes?...

When was the submission? I have been informed by the Met that although they have to send an NIP within fourteen days they then have up to six...

While I agree, not all bike fitters are equal. I found their know-how varies enormously—some are considerably more expert than others.

Now on my PC it says again that I don't have a subscription. I ask you to indicate what should be done to avoid this situation.

Like Hawkinspeter, I am a bit of a tool squirrel. I bought one of these. It is really neat and well made, but I've found it rather confusing to use...

Most Popular News

Are Tour de France Racers Cheating With Secret Motors?

An engineer's testimony in an upcoming '60 Minutes' segment suggests long-running fraud

According to promotional materials from CBS, a central allegation in the story is Varjas’s claim that in 1998, he sold a motor and exclusive use rights for a decade to an unnamed buyer for $2 million, and that he believes the system was then used in pro cycling . While the promo material, at least, does not explicitly name Lance Armstrong as that user, multiple sources say that is the implication in the story, and that viewers might infer that Armstrong was the user. When contacted by Bicycling , Armstrong acknowledged that 60 Minutes had contacted him for comment.

RELATED: How Does Mechanical Doping Work?

If true, it would be an extraordinary revelation in two ways. First, it would constitute a massive fraud in addition to the doping that helped Armstrong become cycling’s winningest Tour de France rider and spurred him to fame and wealth before the United States Anti-Doping Agency’s investigation brought him down.” And most sensational, it implies that fraud lay entirely hidden for almost two decades, even as Armstrong’s doping was the subject of widespread rumor and accusation almost since his first Tour win before he finally admitted it.

But did it really happen? And if motors were used almost two decades ago, are they still being used today?

It’s easy to see why a motor would be attractive to a pro cyclist, if you could use one without being caught. A motor could completely evade anti-doping detection while offering a similar performance boost. That’s vital in a sport where the differences between first and 10th—or even 20th place—can be minuscule.

Take Laurens ten Dam, a Dutch pro who’s raced at the sport’s top level for 15 years, and an early adopter of publishing power output data from races on his Strava account, a signal of transparency to fans about his natural abilities. On the crucial summit finish of Stage 18 of the 2014 Tour de France, ten Dam averaged 370 watts on the 37-minute final ascent to Hautacam, preserving a top-10 overall finish.

If augmented by even a modest 30 watts of power from a motor and battery small enough to hide in a frame, that would boost ten Dam’s own exceptional, human-powered output by eight percent—roughly the same increase that some studies have shown to be possible from powerful drugs like EPO. If he’d had that kind of motor assistance for a few crucial stages like the Hautacam ascent?

“I would have won the Tour instead of finishing ninth,” he said.

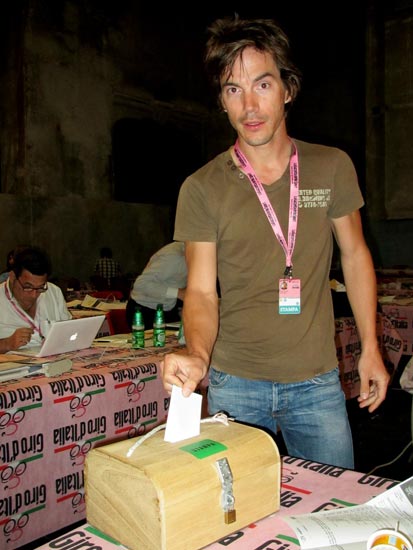

What is striking about Varjas’s claims to CBS and other media outlets is that they predate the first known accusation of this kind by more than a decade. In 2010, Swiss time trial and classics specialist Fabian Cancellara came under scrutiny when, at the Tour of Flanders, he took a curiously timed bike change and then went on to win by accelerating away from his competitors with disconcerting ease. A video investigation by an independent Italian journalist not long after focused on what were claimed to be suspicious hand movements, like hitting a start button for a motor. Cancellara has consistently denied ever cheating with a motor. But the accusation, and the circumstantial evidence, stuck with the sport.

In later years, other riders stood accused as well, often on similar bases. A 23-second YouTube clip from the 2014 Vuelta Espana, for example, shows Canadian pro Ryder Hesjedal crashing in a roundabout:

As his bike comes to a stop, the rear wheel appears to keep spinning, turning the bike in a lazy circle. It’s been viewed over 550,000 times online. Hesjedal also denied using a motor.

Circumstantial evidence aside, cycling’s governing body, the UCI , was concerned enough to start sporadically x-raying riders’ bikes in 2010. In 2016, it added a more sophisticated test : a tablet-based app that checks for the magnetic fields a motor produces, even when it’s off. The result has been a kind of motor mania among devoted fans of the sport, where every rider is under suspicion and every race live stream is scrutinized for evidence of hidden motors. The media has jumped in as well, with RAI Sport, Stade 2, and other outlets conducting investigations, interviewing figures like Varjas, or filming races with thermal imaging cameras that detect suspicious heat blooms from riders’ bike frames. To date, however, the UCI has only caught a single cheater : a young Belgian cyclocross racer named Femke van den Driessche, almost exactly one year to the day before the 60 Minutes report.

“The shame of a WorldTour rider getting caught? I think it’d be mindblowing if anything like that happened; they’d be shunned.”

There are several types of hidden motors said to be in existence. Of them, the bottom-bracket mounted systems shown in a 60 Minutes promotional video released January 27 are most widely known. But when contacted by Bicycling , Varjas also said he makes even smaller motors that are entirely concealed inside a bicycle’s rear hub. “Motor, battery, electronics, etc. are invisible,” he wrote in a brief email response to our questions. “There is no wire from the bike, and you get 60-200 watts of assistance.” The price? Between 50,000 and 200,000 Euro. Varjas even claims to make the sophisticated electromagnetic motor systems that are rumored to exist.

But installing a hidden motor in a bicycle is no easy feat. There are significant technical restrictions. Some commercially available systems, like those from Vivax, require a minimum seat tube size (31.6mm) which is larger than those of frames from many bicycle brands. To hide battery packs, frames may have to be modified with sophisticated carbon-fiber repair techniques. “You could do that; it wouldn’t be too hard,” said Craig Calfee , a pioneer of carbon-fiber frames who also runs a frame repair service. (Calfee adds he’s never been asked to help a rider cheat.) But it would require a skilled composites expert like Calfee or his staff to ensure the structural integrity of a modified frame.

By contrast, hub motor systems could be used on any frame, but would require even finer concealment inside relatively small hub shells already packed with axles, cartridge bearings, and freehub clutches; none have ever been publicly demonstrated. Most exotic are the electromagnetic systems. It is literally child’s play to build a simple electromagnetic, or homopolar, motor with a magnet and a battery. But getting that technology powerful enough to propel a bicycle, and then conceal it? To date, just one company has managed to do this publicly: German wheelmaker Lightweight and parent company CarboFibreTec, which showed a city bike with a functional prototype electromagnetic drive at Eurobike in 2014. It cost the company 2.5 million Euros to develop (about $2,674,625), said engineer Simon Thanner, who doubts that fully concealed systems exist. “In our opinion, it’s not possible to minimize the motor components to be invisible,” he said. “To make it so small that it can’t be seen on a road bike, the costs would explode, and it still wouldn’t work.”

Weight would be another concern. Even with the UCI’s mandatory minimum-weight limit of 14.99 pounds offering some help, some of the lighter team-issue race bikes today aren’t much less than 14 pounds ( mechanics add weight back in various forms). Even the smallest motor system would likely add at least a pound. In Armstrong’s day, bikes were routinely above the weight limit. According to longtime US Postal Service team mechanic Geoff Brown, Armstrong’s 1999 Trek OCLV road bike weighed about 16.5 pounds. Even in 2002, with lighter parts and a new 5900 Superlight model with a special blend of carbon fiber, the bike barely approached 15 pounds. If there’s one thing racers hate, it’s carrying an ounce more weight than necessary.

To install and maintain a motor would require a team effort: a rider might purchase a motor through a middleman to conceal its end use, but he’d need carbon-fiber repair specialists to install and conceal it, and team mechanics to maintain the bike; even coaches and team directors might know about its use.

In other words, you’d need a conspiracy. And a man like Varjas would be essential.

When asked about his background , Varjas told Bicycling he won a youth physicist competition in Hungary several times, but claimed no formal training as an engineer or physicist. “I did my own research and study as an autodidact,” he wrote, adding that we would “learn his real history soon.” But he has thin ties to cycling. None of the current professional riders we spoke to knew of him, or even knew of Sandro Lerici, an associate who’s listed as a contact on the site where Varjas advertises his systems under the EPowers name. (Lerici is an Italian former pro who had several short stints as a team director, most recently at Lampre-Merida from 2011-2013; he also sells natural pet food.)

In an online interview published last February, Varjas said he was inspired to make his motor to help people ride bikes again who’d been disabled, particularly in wars. But he did not respond to Bicycling's question about why the system would then need to be hidden: Why not just make a normal e-bike ? He’s not yet demonstrated his claimed hub or electromagnetic systems—while props of a wheel system appear in the 60 Minutes story’s promotional video, and Varjas claims French TV will soon demonstrate his hub system, it’s unclear if 60 Minutes will show working versions of either—and his EPowers company only advertises crank-based systems. Varjas holds several European patents on motor systems for bicycles (some for such elements as dual-battery systems for more power), but the oldest of them dates back to 2013, some 15 years after his claimed first sale and a full five years after the supposed 10-year exclusive license expired.

In short, there are a lot of holes in Varjas’s story. When asked if he could show Bicycling documentary proof that his motor existed in 1998, he deflected the question, reassuring us that he had provided it to 60 Minutes and that he needed to remain quiet due to the CBS show and a pending book deal in France.

“They collected all the proof,” he wrote of CBS. “Don’t worry. They would be stupid to publish if not true.”

RELATED: The Most Memorable Doping Excuses in Cycling

Hidden motors do exist; that is undeniable. And the sources we spoke with acknowledged that it was technologically feasible to create one as far back as the mid-1990s. But feasible is not the same as proof it happened. And for modern pros, none of the ones we spoke with think that motors are being widely used, if they’re used at all.

“As we’ve seen, where there’s a will there’s a way,” said Brent Bookwalter, a longtime pro on BMC Racing. “I have a hard time saying adamantly without doubt that no one has ever used a motor. But I’ve also never seen anything that would lead me to believe that they have.” Phil Gaimon , who raced two years on the WorldTour with Garmin and Cannondale-Drapac, said he suspects Cancellara used a motor “for a few select races” in 2010, but said he’s skeptical of more recent accusations. “Once [the UCI] is searching for it, you can’t do it anymore,” he said.

If there are sources who can confirm Varjas’s claims, they haven’t stepped forward yet. (It's not yet known if 60 Minutes has that confirmation.) But it’s worth remembering that even the earliest whispers of Armstrong’s doping began not long after his 1999 win, and came from multiple sources associated with him. Bicycling contacted two team mechanics who worked for Armstrong’s US Postal Service and Discovery Channel teams: Brown (1997-2007) and Dave Lettieri (2000 Tour only). Neither said they saw any suspicious signs on the bikes. “I handled various Lance bikes from 1993 through 2005 on a consistent basis, and never saw anything or was involved in anything suspicious,” Brown said. When Armstrong began winning Tours, Brown recalled that sponsor equipment began to flow in. “There was no need to economize parts,” he said. “If the bottom bracket wasn’t worn out after three days of racing, it didn’t matter; we replaced it anyway.” Brown said it “was impossible someone would be able to put a motor in a bike without anyone noticing.”

Bicycling contacted three former teammates—Jonathan Vaughters, Frankie Andreu , and Christian Vande Velde—who were variously present during Armstrong’s first three Tour wins. None recalled Armstrong discussing motors, or had any suspicion that anything was amiss. “It’s not something I was ever concerned about as a rider or manager,” said Vaughters of the motor rumors. Vande Velde answered, succinctly, “No, not remotely,” when asked in an email if he’d ever noticed or suspected in his 17-year career that a rider used a motor in a race. All three riders testified against Armstrong in the USADA anti-doping case; Vaughters and Andreu in particular have for years had strained relationships with their former teammate. Vande Velde, at least, is friendly again with Armstrong; the two will race on a team together at the upcoming 24 Hours of the Old Pueblo mountain bike race. Floyd Landis and Tyler Hamilton did not respond to requests for comment.

Contacted by Bicycling , Armstrong denied ever having used a motor in a race, and said that his legal representatives had recently spoken with Varjas. “He confirmed to us that he never sold that technology to me, to anyone on the team or to anyone associated with me,” Armstrong said, and asserted that such information had been provided to 60 Minutes . Michael Rey, one of the two producers on the 60 Minutes piece, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

If Armstrong—or anyone—did use a motor prior to 2015, the prospect for punishment is unclear. Race results could be stripped by the UCI, but it wasn’t until the 2015 season that the organization specifically addressed what it calls technological fraud in its rules on discipline.

Those new penalties are extremely harsh, and not only for the rider. Van den Driessche, the Belgian cyclocrosser, elected not to contest the charges and was banned for six years . But unlike doping, where typically only the rider in question can be punished, whole teams can be sanctioned for motors. Any team with a rider caught using a motor can be fined as much as one million Swiss francs (roughly $1,000,800), and banned from competition for a minimum of six months. Pro team finances are already perilous, with short-term sponsor contracts that have clear moral turpitude clauses. That kind of penalty could easily be a death sentence for a pro team.

Past that, the reaction from riders themselves would likely be swift and harsh. For decades, doping was endemic to the sport of cycling, which created a kind of omertà, or code of silence. A rider caught doping was rarely criticized by his peers, because most of them were also doping.

But if motors are or have been used in the sport, the challenge and complexity of pulling off suggests that it’s been rare. So the riders themselves would also see it as cheating, and condemn it as such. “The general idea is that it’s so morally wrong to do that that nobody believes it’s happened,” said ten Dam. Gaimon agreed: “The shame of a WorldTour rider getting caught?” he said. “I think it’d be mindblowing if anything like that happened; they’d be shunned.”

RELATED: You Can Buy Mechanically Doped Bikes

Van den Driessche was caught the very first time the UCI deployed its magnetic field detection system. Since then, not a single motor has been found despite many checks—3,773 at last year’s Tour de France, for example. So either the approach is working and no one today is using a motor, or they still are, and the method is flawed. The UCI has said thermal imaging of the type used in media investigations is not a reliable detection method, but.it started using the technique some in 2016.

If the UCI seriously believes that motor use is a problem, and it seems it does, then stopping it is not rocket science. In addition to its magnetic detection efforts, the UCI could continue to conduct physical bike inspections at the finish like it did to Alberto Contador’s bike at the 2015 Giro d’Italia, much like how riders are randomly selected for post-race anti-doping measures. Crankarms and seatposts can be removed in seconds for visual inspection. Weight can be a clue as well: As part of their marketing efforts, bike and component manufacturers often list detailed weights for their products; media and retailers tend to do the same. That information could be databased to perform a quick comparison when weighing bikes and wheels at the finish line. Deviations of more than a handful of grams would send a bike on for further inspection—essentially confiscating the item for disassembly.

Traditional doping has always been extremely difficult to root out, in part because it mostly took place in training, rather than at races, and the physical evidence sometimes came down to a biochemist’s judgment call on whether a level of a natural substance in a doping sample is suspicious.

Technological fraud is not like that; either there is a motor in a rider’s bike at a race, or there is not. If they are there, finding them is only a matter of looking hard enough.

Keep up with the biggest stories in cycling by subscribing to the Bicycling newsletter.

.css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#F8D811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} Racing

2024 Giro d’Italia Results

2024 Giro d’Italia Riders to Watch

6 Must-Watch Stages of the 2024 Giro d’Italia

A Comprehensive Guide to the 2024 Giro d’Italia

Is the Giro d’Italia the Tougher Grand Tour?

Giro d’Italia’s Jersey Colors: What They Mean

Luke Lamperti Gears Up for Giro d’Italia Debut

2024 Giro d’Italia | Geraint Thomas to Lead Ineos

Highlights & Lessons From the 2024 Spring Classics

Wout van Aert Is Back to Outdoor Training

How to Watch La Vuelta Femenina 2024

CURRENT PRICES END MAY 12

Outside Festival feat. Thundercat and Fleet Foxes.

FROM JUST $44

Powered by Outside

Tour de France: UCI says no infractions following 720 inspections for ‘motor doping’

New detection methods for 'technological fraud' will be rolled out at the tokyo olympic games for track, road and mountain bike disciplines..

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

ANDORRA (VN) — There are no motors in the Tour de France peloton, at least that’s according to the UCI.

Cycling’s governing body carried out 720 controls in the opening two weeks of racing, and the UCI said “all tests have come back negative.”

The UCI said it used magnetic scanning tablets on 606 bikes before the start of stages, and put 114 bikes through its mobile X-ray lab after stages.

The UCI continues to work to push back against the idea that illicit motors and other banned mechanized assistance might be taking place during the Tour.

- The UCI kicks out rider for tossing bottle at Tour of Flanders

- The UCI bans super-tuck as it rolls out new safety rules

In a press note Monday, the UCI outlined its testing protocol, saying that each day’s winner, as well as the GC leader, have their bikes X-rayed after each stage, along with other random controls throughout the race.

“The remainder of the post-stage testing pool is decided on a two-pronged approach: bikes selected by the UCI based on its information and intelligence, and bikes ridden by athletes selected for targeted anti-doping controls by the International Testing Agency (ITA), the independent body in charge of the UCI’s anti-doping activities,” a press release stated.

The UCI rolled out its scanning tablets in 2016, designed to detect batteries hidden inside of a frame, as well as X-rays in 2018.

- Jumbo-Visma director kicked out of Tour de France after X-ray row

- How the UCI plans to combat ‘technological fraud’

The UCI said new devices to better control technological fraud will be introduced for the Tokyo Olympic Games next month at the road, mountain bike, and track cycling events.

“A new backscatter technology will be used to test bikes at the Tokyo Olympic Games,” a statement read. “This relatively compact and light hand-held device provides instant images of the interior of the bike that can be shared in real-time to anywhere in the world via a secure platform.”