9 myths and the truth about Gypsies and Travellers

For starters, only a small number of travellers camp illegally

- 00:01, 25 OCT 2019

- Updated 15:20, 25 OCT 2019

Sign up to our free email newsletter to receive the latest breaking news and daily roundups

We have more newsletters

Travellers and Gypsies are one of the most misunderstood minority groups in the UK.

To combat this the Travellers' Times website has created a guide, which aims to promote positive images of the Traveller and Gypsy community.

It has been written in response to hate crime and racist language directed towards their communities.

Cambridgeshire has seen tensions between the Traveller and settled communities in recent years, with caravans pitching on unauthorised sites across including Fulbourn, Papworth, Cambourne and at Cambridge Business and Research Park.

As well as causing disruption to residential communities, there can often be a hefty clean-up bill as some groups leave behind piles of rubbish.

Cambridge police say they are committed to working with local councils to tackle the problem and has previously used powers under Section 61 of the Crime and Disorder Act to order unlawful encampments to disperse.

But, as the Travellers' Times points out, a only a small number of Travellers camp illegally.

While tensions can run high at times many people hold misconceptions, which Travellers' Times hopes to dispell.

Things you should know about gypsies and travellers according to Travellers' Times

There are nine reoccurring myths and misconceptions about their culture and origins.

1) Who are the UK’s Gypsies and Travellers?

Travellers and Gypsies have a rich and varied history.

Romany Gypsies are the descendants of a migration of peoples from Northern India in the 10-12AD, who spread across Eastern and Western Europe, reaching Great Britain in around the 1600’s.

Irish Travellers – or Pavee – and Scottish Travellers - are the descendants of a nomadic people who have traditionally inhabited Ireland and mainland Britain.

Roma usually refers to the descendants of the migration of various groups of peoples from Northern India in the 10th to 12th century who settled in Eastern and Western Europe.

2) Should we use a capital letter to start ‘gypsy and/or traveller’?

Romany Gypsies, Scottish, Welsh and Irish Travellers are all ethnic minorities, recognised under UK law and the Irish government.

Therefore it is customary to capitalise ‘G’ and ‘T’ for Gypsies and Travellers.

3) Lifestyle, ethnic group or ‘community’?

Research shows Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT) should be seen as ethnic groups rather than ‘lifestyles’.

All the different GRT groups in the UK have a shared language or dialect, some shared cultural practices, most will identify as an ethnic group, and all individuals from all groups are legally recognised as ethnic minorities under the Equalities Act 2010.

4) How many Travellers live in the UK?

In the 2011 Census, 58,000 people identified themselves as Gypsy or Irish Traveller, accounting for just 0.1 per cent of the resident population of England and Wales. However the figure is likely to be much higher.

5) Traveller politics

There is a cross-party parliamentary group called the All Party Parliamentary Group for Gypsies, Roma and Travellers.

This is currently led by the charity Friends, Families and Travellers and the co-Chairs are Kate Green, MP for Stretford and Urmston, and Baroness Janet Whitaker.

6) Where do Travellers live?

The number of Gypsy and Traveller caravans in England and Wales is recorded twice yearly.

The vast majority of Gypsies and Travellers living in caravans stay on permanent public and private sites which have planning permission, waste collection and are subject to rent (unless of course the site is privately owned by the occupier), council tax and utility bills.

7) A small minority pitch on unauthorised land

A small minority of Gypsies and Traveller caravans are classed as unauthorised and staying on land they do not own, such as roadside camps.

This minority, which will include Gypsies and Travellers with no other place to stay and also Gypsies and Travellers moving off authorised sites to go ‘travelling’ during the summer, receives the vast majority of local news coverage.

7) Criminal Justice System

Far too many Gypsies and Travellers are in prison, as many as five per cent of the population according to Government research.

Meanwhile 0.13 per cent of the general UK population are in prision.

The Irish Chaplaincy in Britain works with Gypsies and Travellers in custody. Some prisons have their own GRT Prisoner Groups. The Travellers’ Times Magazine is delivered free to many UK HMP’s and the editor receives many letters from prisoners.

8) Nomadism

Nomadism is a shared heritage of Gypsies and Travellers and not a present reality.

Not all Gypsies and Irish and Scottish Travellers ‘travel’ – or may only ‘travel’ to traditional cultural events like Appleby Horse Fair.

9) Prejudice, oppression and the Holocaust

Many Gypsies, Roma and Travellers face daily prejudice based on negative stereotyping and misunderstanding.

This is because people generalise from the anti-social actions of a few and protect that onto the whole population.

Prejudice against them is longstanding.

In some Eastern and even Western European countries, Roma are segregated and live in camps and slums isolated from the rest of the population.

Alongside the Jewish population Roma were specifically singled out for extermination by Nazi racial policy.

Historians estimate the number murdered by Nazi and axis regimes during the Second World War to be around 500,000, although some historians say it is closer to a million.

- Most Recent

Romani (Gypsy), Roma and Irish Traveller History and Culture

Romani (Gypsy), Roma and Irish Traveller people belong to minority ethnic groups that have contributed to British society for centuries. Their distinctive way of life and traditions manifest themselves in nomadism, the centrality of their extended family, unique languages and entrepreneurial economy. It is reported that there are around 300,000 Travellers in the UK and they are one of the most disadvantaged groups. The real population may be different as some members of these communities do not participate in the census .

The Traveller Movement works predominantly with ethnic Romani (Gypsy), Roma, and Irish Traveller Communities.

Irish Travellers and Romany Gypsies

Irish Travellers

Traditionally, Irish Travellers are a nomadic group of people from Ireland but have a separate identity, heritage and culture to the community in general. An Irish Traveller presence can be traced back to 12th century Ireland, with migrations to Great Britain in the early 19th century. The Irish Traveller community is categorised as an ethnic minority group under the Race Relations Act, 1976 (amended 2000); the Human Rights Act 1998; and the Equality Act 2010. Some Travellers of Irish heritage identify as Pavee or Minceir, which are words from the Irish Traveller language, Shelta.

Romany Gypsies

Romany Gypsies have been in Britain since at least 1515 after migrating from continental Europe during the Roma migration from India. The term Gypsy comes from “Egyptian” which is what the settled population perceived them to be because of their dark complexion. In reality, linguistic analysis of the Romani language proves that Romany Gypsies, like the European Roma, originally came from Northern India, probably around the 12th century. French Manush Gypsies have a similar origin and culture to Romany Gypsies.

There are other groups of Travellers who may travel through Britain, such as Scottish Travellers, Welsh Travellers and English Travellers, many of whom can trace a nomadic heritage back for many generations and who may have married into or outside of more traditional Irish Traveller and Romany Gypsy families. There were already indigenous nomadic people in Britain when the Romany Gypsies first arrived hundreds of years ago and the different cultures/ethnicities have to some extent merged.

Number of Gypsies and Travellers in Britain

This year, the 2021 Census included a “Roma” category for the first time, following in the footsteps of the 2011 Census which included a “Gypsy and Irish Traveller” category. The 2021 Census statistics have not yet been released but the 2011 Census put the combined Gypsy and Irish Traveller population in England and Wales as 57,680. This was recognised by many as an underestimate for various reasons. For instance, it varies greatly with data collected locally such as from the Gypsy Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessments, which total the Traveller population at just over 120,000, according to our research.

Other academic estimates of the combined Gypsy, Irish Traveller and other Traveller population range from 120,000 to 300,000. Ethnic monitoring data of the Gypsy Traveller population is rarely collected by key service providers in health, employment, planning and criminal justice.

Where Gypsies and Travellers Live

Although most Gypsies and Travellers see travelling as part of their identity, they can choose to live in different ways including:

- moving regularly around the country from site to site and being ‘on the road’

- living permanently in caravans or mobile homes, on sites provided by the council, or on private sites

- living in settled accommodation during winter or school term-time, travelling during the summer months

- living in ‘bricks and mortar’ housing, settled together, but still retaining a strong commitment to Gypsy/Traveller culture and traditions

Currently, their nomadic life is being threatened by the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, that is currently being deliberated in Parliament, To find out more or get involved with opposing this bill, please visit here

Although Travellers speak English in most situations, they often speak to each other in their own language; for Irish Travellers this is called Cant or Gammon* and Gypsies speak Romani, which is the only indigenous language in the UK with Indic roots.

*Sometimes referred to as “Shelta” by linguists and academics

New Travellers and Show People

There are also Traveller groups which are known as ‘cultural’ rather than ‘ethnic’ Travellers. These include ‘new’ Travellers and Showmen. Most of the information on this page relates to ethnic Travellers but ‘Showmen’ do share many cultural traits with ethnic Travellers.

Show People are a cultural minority that have owned and operated funfairs and circuses for many generations and their identity is connected to their family businesses. They operate rides and attractions that can be seen throughout the summer months at funfairs. They generally have winter quarters where the family settles to repair the machinery that they operate and prepare for the next travelling season. Most Show People belong to the Showmen’s Guild which is an organisation that provides economic and social regulation and advocacy for Show People. The Showman’s Guild works with both central and local governments to protect the economic interests of its members.

The term New Travellers refers to people sometimes referred to as “New Age Travellers”. They are generally people who have taken to life ‘on the road’ in their own lifetime, though some New Traveller families claim to have been on the road for three consecutive generations. The New Traveller culture grew out of the hippie and free-festival movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Barge Travellers are similar to New Travellers but live on the UK’s 2,200 miles of canals. They form a distinct group in the canal network and many are former ‘new’ Travellers who moved onto the canals after changes to the law made the free festival circuit and a life on the road almost untenable. Many New Travellers have also settled into private sites or rural communes although a few groups are still travelling.

If you are a new age Traveller and require support please contact Friends, Families, and Travellers (FFT) .

Differences and Values

Differences Between Romani (Gypsies), Roma and Irish Travellers.

Romani (Gypsies), Roma and Irish Travellers are often categorised together under the “Roma” definition in Europe and under the acronym “GRT” in Britain. These communities and other nomadic groups, such as Scottish and English Travellers, Show People and New Travellers, share a number of characteristics in common: the importance of family and/or community networks; the nomadic way of life, a tendency toward self-employment, experience of disadvantage and having the poorest health outcomes in the United Kingdom.

The Roma communities also originated from India from around the 10th/ 12th centuries and have historically faced persecution, including slavery and genocide. They are still marginalised and ghettoised in many Eastern European countries (Greece, Bulgaria, Romania etc) where they are often the largest and most visible ethnic minority group, sometimes making up 10% of the total population. However, ‘Roma’ is a political term and a self-identification of many Roma activists. In reality, European Roma populations are made up of various subgroups, some with their own form of Romani, who often identify as that group rather than by the all-encompassing Roma identity.

Travellers and Roma each have very different customs, religion, language and heritage. For instance, Gypsies are said to have originated in India and the Romani language (also spoken by Roma) is considered to consist of at least seven varieties, each a language in their own right.

Values and Culture of GRT Communities

Family, extended family bonds and networks are very important to the Gypsy and Traveller way of life, as is a distinct identity from the settled ‘Gorja’ or ‘country’ population. Family anniversaries, births, weddings and funerals are usually marked by extended family or community gatherings with strong religious ceremonial content. Gypsies and Travellers generally marry young and respect their older generation. Contrary to frequent media depiction, Traveller communities value cleanliness and tidiness.

Many Irish Travellers are practising Catholics, while some Gypsies and Travellers are part of a growing Christian Evangelical movement.

Gypsy and Traveller culture has always adapted to survive and continues to do so today. Rapid economic change, recession and the gradual dismantling of the ‘grey’ economy have driven many Gypsy and Traveller families into hard times. The criminalisation of ‘travelling’ and the dire shortage of authorised private or council sites have added to this. Some Travellers describe the effect that this is having as “a crisis in the community” . A study in Ireland put the suicide rate of Irish Traveller men as 3-5 times higher than the wider population. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the same phenomenon is happening amongst Traveller communities in the UK.

Gypsies and Travellers are also adapting to new ways, as they have always done. Most of the younger generation and some of the older generation use social network platforms to stay in touch and there is a growing recognition that reading and writing are useful tools to have. Many Gypsies and Travellers utilise their often remarkable array of skills and trades as part of the formal economy. Some Gypsies and Travellers, many supported by their families, are entering further and higher education and becoming solicitors, teachers, accountants, journalists and other professionals.

There have always been successful Gypsy and Traveller businesses, some of which are household names within their sectors, although the ethnicity of the owners is often concealed. Gypsies and Travellers have always been represented in the fields of sport and entertainment.

How Gypsies and Travellers Are Disadvantaged

The Romani (Gypsy), Roma and Irish Traveller communities are widely considered to be among the most socially excluded communities in the UK. They have a much lower life expectancy than the general population, with Traveller men and women living 10-12 years less than the wider population.

Travellers have higher rates of infant mortality, maternal death and stillbirths than the general population. They experience racist sentiment in the media and elsewhere, which would be socially unacceptable if directed at any other minority community. Ofsted consider young Travellers to be one of the groups most at risk of low attainment in education.

Government services rarely include Traveller views in the planning and delivery of services.

In recent years, there has been increased political networking between the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller activists and campaign organisations.

Watch this video by Travellers Times made for Gypsy Roma Traveller History Month 2021:

Information and Support

We have a variety of helpful guides to provide you with the support you need

Community Corner

Read all about our news, events, and the upcoming music and artists in your area

Can we store analytics cookies on your device?

Analytics cookies help us understand how our website is being used. They are not used to identify you personally.

You’ve accepted all cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Ethnicity facts and figures homepage Home

Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller ethnicity summary

Updated 29 March 2022

1. About this page

2. the gypsy, roma and traveller group, 3. classifications, 4. improving data availability and quality, 5. population data, 6. education data, 7. economic activity and employment data.

- 8. Home ownership data data

- 9. Health data

This is a summary of statistics about people from the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller ethnic groups living in England and Wales.

It is part of a series of summaries about different ethnic groups .

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) is a term used to describe people from a range of ethnicities who are believed to face similar challenges. These groups are distinct, but are often reported together.

This page includes:

- information about GRT data and its reliability

- some statistics from the 2011 Census

- other statistics on the experiences of people from the GRT groups in topics including education, housing and health

This is an overview based on a selection of data published on Ethnicity facts and figures or analyses of other sources. Some published data (for example, on higher education) is only available for the aggregated White ethnic group, and is not included here.

Through this report, we sometimes make comparisons with national averages. While in other reports we might compare with another ethnic group (usually White British), we have made this decision here because of the relatively small impact the GRT group has on the overall national average.

The term Gypsy, Roma and Traveller has been used to describe a range of ethnic groups or people with nomadic ways of life who are not from a specific ethnicity.

In the UK, it is common in data collections to differentiate between:

- Gypsies (including English Gypsies, Scottish Gypsies or Travellers, Welsh Gypsies and other Romany people)

- Irish Travellers (who have specific Irish roots)

- Roma, understood to be more recent migrants from Central and Eastern Europe

The term Traveller can also encompass groups that travel. This includes, but is not limited to, New Travellers, Boaters, Bargees and Showpeople. (See the House of Commons Committee report on Tackling inequalities faced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities .)

For the first time, the 2011 Census ethnic group question included a tick box for the ethnic group ‘Gypsy or Irish Traveller’. This was not intended for people who identify as Roma because they are a distinct group with different needs to Gypsy or Irish Travellers.

The 2021 Census had a ‘Gypsy or Irish Traveller’ category, and a new ‘Roma’ category.

A 2018 YouGov poll found that 66% of people in the UK wrongly viewed GRT not to be an ethnic group, with many mistaking them as a single group (PDF). It is therefore important that GRT communities are categorised correctly on data forms, using separate tick boxes when possible to reflect this.

The 2011 Census figures used in this report and on Ethnicity facts and figures are based on respondents who chose to identify with the Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group. People who chose to write in Roma as their ethnicity were allocated to the White Other group, and data for them is not included here. Other data, such as that from the Department for Education, includes Roma as a category combined with Gypsy, with Irish Traveller shown separately.

The commentary in this report uses the specific classifications in each dataset. Users should exercise caution when comparing different datasets, for example between education data (which uses Gypsy/Roma, and Irish Traveller in 2 separate categories) and the Census (which uses Gypsy and Irish Traveller together, but excludes data for people who identify as Roma).

Finally, it should be noted that there is also a distinction that the government makes, for the purposes of planning policy, between those who travel and the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller ethnicities. The Department for Communities and Local Government (at the time, now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) planning policy for traveller sites (PDF) defines "gypsies and travellers" as:

"Persons of nomadic habit of life whatever their race or origin, including such persons who on grounds only of their own or their family’s or dependants’ educational or health needs or old age have ceased to travel temporarily, but excluding members of an organised group of travelling showpeople or circus people travelling together as such."

This definition for planning purposes includes any person with a nomadic habit, whether or not they might have identified as Gypsy, Roma or Traveller in a data collection.

The April 2019 House of Commons Women and Equalities Select Committee report on inequalities faced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities noted that there was a lack of data on these groups.

The next section highlights some of the problems associated with collecting data on these groups, and what is available. Some of the points made about surveys, sample sizes and administrative data are generally applicable to any group with a small population.

Improving data for the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller populations, as well as other under-represented groups in the population is part of the recommendations in the Inclusive Data Taskforce report and the key activities described in the ONS response to them. For example, in response to recommendation 3 of the report, ONS, RDU and others will "build on existing work and develop new collaborative initiatives and action plans to improve inclusion of under-represented population groups in UK data in partnership with others across government and more widely".

Also, the ONS response to recommendation 4 notes the development of a range of strategies to improve the UK data infrastructure and fill data gaps to provide more granular data through new or boosted surveys and data linkage. Recommendation 6 notes that research will be undertaken using innovative methods best suited to the research question and prospective participants, to understand more about the lived experiences of several groups under-represented in UK data and evidence, such as people from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller groups.

4.1 Classifications

In some data collections, the option for people to identify as Gypsy, Roma or Traveller is not available. Any data grouped to the 5 aggregated ethnic groups does not show the groups separately. Data based on the 2001 Census does not show them separately as there was no category for people identifying as Gypsy, Roma or Traveller. As part of our Quality Improvement Plan, the Race Disparity Unit (RDU) has committed to working with government departments to maintain a harmonised approach to collecting data about Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people using the GSS harmonised classification. The harmonised classification is currently based on the 2011 Census, and an update is currently being considered by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

In particular, RDU has identified working with DHSC and NHS Digital colleagues as a priority – the NHS classification is based on 2001 Census classifications and does not capture information on any of the GRT groups separately (they were categorised as White Other in the 2001 Census). Some of these issues have been outlined in the quarterly reports on progress to address COVID-19 health inequalities .

Research into how similar or different the aggregate ethnic groups are shows how many datasets are available for the GRT group.

Further information on the importance of harmonisation is also available.

4.2 Census data

A main source of data on the Gypsy and Irish Traveller groups is the 2011 Census. This will be replaced by the 2021 Census when results are published by the ONS. The statistics in this summary use information from Ethnicity facts and figures and the Census section of ONS’s NOMIS website.

4.3 Survey data

It is often difficult to conclude at any one point in time whether a disparity is significant for the GRT population, as the population is so small in comparison to other ethnic groups.

Even a large sample survey like the Annual Population Survey (APS) has a small number of responses from the Gypsy and Irish Traveller ethnic group each year. Analysis of 3 years of combined data for 2016, 2017 and 2018 showed there were 62 people in the sample (out of around 500,000 sampled cases in total over those 3 years) in England and Wales. Another large survey, the Department for Transport’s National Travel Survey, recorded 58 people identifying as Gypsy or Traveller out of 157,000 people surveyed between 2011 and 2019.

Small sample sizes need not be a barrier to presenting data if confidence intervals are provided to help the user. But smaller sample sizes will mean wider confidence intervals, and these will provide limited analytical value. For the 2016 to 2018 APS dataset – and using the standard error approximation method given in the LFS User Guide volume 6 with a fixed design factor of 1.6 (the formula is 1.6 * √p(1 − p)/n where p is the proportion in employment and n is the sample size.) – the employment rate of 35% for working age people in the Gypsy and Traveller group in England and Wales would be between 16% and 54% (based on a 95% confidence interval). This uses the same methodology as the ONS’s Sampling variability estimates for labour market status by ethnicity .

A further reason for smaller sample sizes might be lower response rates. The Women and Select Committee report on the inequalities faced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities noted that people in these groups may be reluctant to self-identify, even where the option is available to them. This is because Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people might mistrust the intent behind data collection.

The RDU recently published a method and quality report on working out significant differences between estimates for small groups using different analytical techniques.

4.4 Administrative data

While administrative data does not suffer from the same issues of sampling variability, small numbers of respondents can mean that data is either disclosive and needs to be suppressed to protect the identity of individuals, or results can fluctuate over time.

An example of this is the measure of students getting 3 A grades or better at A level . In 2019 to 2020, no Irish Traveller students achieved this (there were 6 students in the cohort). In 2017 to 2018, 2 out of 7 Irish Traveller students achieved 3 A grades, or 28.6% – the highest percentage of all ethnic groups.

Aggregating time periods might help with this, although data collected in administrative datasets can change over time to reflect the information that needs to be collected for the administrative process. The data collected would not necessarily be governed by trying to maintain a consistent time series in the same way that data collected through surveys sometimes are.

4.5 Data linkage

Linking datasets together provides a way of producing more robust data for the GRT groups, or in fact, any ethnic group. This might improve the quality of the ethnicity coding in the dataset being analysed if an ethnicity classification that is known to be more reliable is linked from another dataset.

Data linkage does not always increase the sample size or the number of records available in the dataset to be analysed, but it might do if records that have missing ethnicity are replaced by a known ethnicity classification from a linked dataset.

An example is the linking of the Census data to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data and death registrations by the ONS. The ethnicity classifications for GRT groups are not included in the HES data, and are not collected in the death registrations process at the moment. So this data linking gives a way to provide some information for Gypsy and Irish Travellers and other smaller groups. The report with data up to 15 May 2020 noted 16 Gypsy or Irish Traveller deaths from COVID-19.

RDU will be working with ONS and others to explore the potential for using data linking to get more information for the GRT groups.

4.6 Bespoke surveys and sample boosts

A country-wide, or even local authority, boost of a sample survey is unlikely to make estimates for the GRT groups substantially more robust. This is because of the relatively small number in the groups to begin with.

Bespoke surveys can be used to get specific information about these groups. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities list of traveller sites available through their Traveller caravan count statistics can help target sampling for surveys, for example. Bespoke surveys might be limited in geographical coverage, and more suitable for understanding GRT views in a local area and then developing local policy responses. An example of a bespoke survey is the Roma and Travellers in 6 countries survey .

Another method that could be useful is snowball sampling. Snowball sampling (or chain-referral sampling) is a sampling technique in which the respondents have traits that are rare to find. In snowball sampling, existing survey respondents provide referrals to recruit further people for the survey, which helps the survey grow larger.

There are advantages to snowball sampling. It can target hidden or difficult to reach populations. It can be a good way to sample hesitant respondents, as a person might be more likely to participate in a survey if they have been referred by a friend or family member. It can also be quick and cost effective. Snowball sampling may also be facilitated with a GRT community lead or cultural mediator. This would help bridge the gap between the GRT communities and the commissioning department to encourage respondent participation.

However, one statistical disadvantage is that the sampling is non-random. This reduces the knowledge of whether the sample is representative, and can invalidate some of the usual statistical tests for statistical significance, for example.

All data in this section comes from the 2011 Census of England and Wales, unless stated otherwise.

In 2011, there were 57,680 people from the Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group in England and Wales, making up 0.1% of the total population. In terms of population, it is the smallest of the 18 groups used in the 2011 Census.

Further ONS analysis of write-in responses in the Census estimated the Roma population as 730, and 1,712 people as Gypsy/Romany.

Table A: Gypsy, Roma and Traveller write-in ethnicity responses on the 2011 Census

Source: Census - Ethnic group (write-in response) Gypsy, Traveller, Roma, GypsyRomany - national to county (ONS). The figures do not add to the 57,680 classified as White: Gypsy/Traveller because Roma is included as White Other, and some people in the other categories shown will have classified themselves in an ethnic group other than White.

An ONS report in 2014 noted that variations in the definitions used for this ethnic group has made comparisons between estimates difficult. For example, some previous estimates for Gypsy or Irish Travellers have included Roma or have been derived from counts of caravans rather than people's own self-identity. It noted that other sources of data estimate the UK’s Gypsy, Roma and Traveller population to be in the region of 150,000 to 300,000 , or as high as 500,000 (PDF).

5.1 Where Gypsy and Irish Traveller people live

There were 348 local authorities in England and Wales in 2011. The Gypsy or Irish Traveller population was evenly spread throughout them. The 10 local authorities with the largest Gypsy or Irish Traveller populations constituted 11.9% of the total population.

Figure 1: Percentage of the Gypsy or Irish Traveller population of England and Wales living in each local authority area (top 10 areas labelled)

Basildon was home to the largest Gypsy or Irish Traveller population, with 1.5% of all Gypsy or Irish Traveller people living there, followed by Maidstone (also 1.5%, although it had a smaller population).

Table 1: Percentage of the Gypsy or Irish Traveller population of England and Wales living in each local authority area (top 10)

28 local authorities had fewer than 20 Gypsy or Irish Traveller residents each. This is around 1 in 12 of all local authorities.

11.7% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people lived in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods , higher than the national average of 9.9% (England, 2019 Indices of Multiple Deprivation).

81.6% of people from the Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group were born in England, and 6.1% in the other countries of the UK. 3.0% were born in Ireland and 8.3% were born somewhere else in Europe (other than the UK and Ireland). Less than 1.0% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people were born outside of Europe.

5.2 Age profile

The Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group had a younger age profile than the national average in England and Wales in 2011.

People aged under 18 made up over a third (36%) of the Gypsy or Irish Traveller population, higher than the national average of 21%.

18.0% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people were aged 50 and above , lower than the national average of 35.0%.

Figure 2: Age profile of Gypsy or Irish Traveller and the England and Wales average

Table 2: age profile of gypsy or irish traveller and the england and wales average, 5.3 families and households.

20.4% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller households were made up of lone parents with dependent children , compared with 7.2% on average for England and Wales.

Across all household types, 44.9% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller households had dependent children, compared with an average of 29.1%.

8.4% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller households were made up of pensioners (either couples, single pensioners, or other households where everyone was aged 65 and over), compared with 20.9% on average.

All data in this section covers pupil performance in state-funded mainstream schools in England.

At all key stages, Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller pupils’ attainment was below the national average.

Figure 3: Educational attainment among Gypsy, Roma, Irish Traveller and pupils from all ethnic groups

Table 3: educational attainment among gypsy, roma, irish traveller and pupils from all ethnic groups.

Source: England, Key Stage 2 Statistics, 2018/19; Key Stage 4 Statistics, 2019/20; and A Level and other 16 to 18 results, 2020/21. Ethnicity facts and figures and Department for Education (DfE). Figures for Key Stage 2 are rounded to whole numbers by DfE.

6.1 Primary education

In the 2018 to 2019 school year, 19% of White Gypsy or Roma pupils, and 26% of Irish Traveller pupils met the expected standard in key stage 2 reading, writing and maths . These were the 2 lowest percentages out of all ethnic groups.

6.2 Secondary education

In the 2019 to 2020 school year, 8.1% of White Gypsy or Roma pupils in state-funded schools in England got a grade 5 or above in GCSE English and maths, the lowest percentage of all ethnic groups.

Gypsy or Roma (58%) and Irish Traveller (59%) pupils were the least likely to stay in education after GCSEs (and equivalent qualifications). They were the most likely to go into employment (8% and 9% respectively) – however, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about these groups due to the small number of pupils in key stage 4.

6.3 Further education

Gypsy or Roma students were least likely to get at least 3 A grades at A level, with 10.8% of students doing so in the 2020 to 2021 school year. 20.0% of Irish Traveller students achieved at least 3 A grades, compared to the national average of 28.9%. The figures for Gypsy or Roma (61) and Irish Traveller (19) students are based on small numbers, so any generalisations are unreliable.

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the summer exam series was cancelled in 2021, and alternative processes were set up to award grades. In 2020/21 attainment is higher than would be expected in a typical year. This likely reflects the changes to the way A/AS level grades were awarded rather than improvements in student performance.

6.4 School exclusions

In the 2019 to 2020 school year, the suspension rates were 15.28% for Gypsy or Roma pupils, and 10.12% for Irish Traveller pupils – the highest rates out of all ethnic groups.

Also, the highest permanent exclusion rates were among Gypsy or Roma pupils (0.23%, or 23 exclusions for every 10,000 pupils). Irish Traveller pupils were permanently excluded at a rate of 0.14%, or 14 exclusions for every 10,000 pupils.

6.5 School absence

In the autumn term of the 2020 to 2021 school year, 52.6% of Gypsy or Roma pupils, and 56.7% of Irish Traveller pupils were persistently absent from school . Pupils from these ethnic groups had the highest rates of overall absence and persistent absence.

For the 2020 to 2021 school year, not attending in circumstances related to coronavirus (COVID-19) was not counted toward the overall absence rate and persistent absence rates.

Data in this section is from the 2011 Census for England and Wales, and for people aged 16 and over. Economic activity and employment rates might vary from other published figures that are based on people of working age.

47% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people aged 16 and over were economically active, compared to an average of 63% in England and Wales.

Of economically active people, 51% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people were employees, and 26% were self-employed. 20% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people were unemployed, compared to an average for all ethnic groups of 7%.

7.1 Socio-economic group

Figure 4: socio-economic group of gypsy or irish traveller and average for all ethnic groups for people aged 16 and over, table 4: socio-economic group of gypsy or irish traveller and average for all ethnic groups for people aged 16 and over.

Source: 2011 Census

31.2% of people in the Gypsy or Irish Traveller group were in the socio-economic group of ‘never worked or long-term unemployed’. This was the highest percentage of all ethnic groups.

The Gypsy or Irish Traveller group had the smallest percentage of people in the highest socio-economic groups. 2.5% were in the ‘higher, managerial, administrative, professional’ group.

15.1% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller people were small employers and own account workers. These are people who are generally self-employed and have responsibility for a small number of workers.

For Gypsy or Irish Travellers, who were 16 and over and in employment, the largest group worked in elementary occupations (22%). This can include occupations such as farm workers, process plant workers, cleaners, or service staff (for example, bar or cleaning staff).

The second highest occupation group was skilled trades (19%), which can include farmers, electrical and building trades. The Gypsy or Irish Traveller group had the highest percentage of elementary and skilled trade workers out of all ethnic groups.

7.2 Employment gender gap

The gender gap in employment rates for the Gypsy or Irish Traveller group aged 16 and over was nearly twice as large as for all ethnic groups combined. In the Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group, 46% of men and 29% of women were employed, a gap of 17%. For all ethnic groups combined, 64% of men and 54% of women were employed, a gap of 10%.

This is likely to be due to the fact that Gypsy or Irish Traveller women (63%) were about 1.5 times as likely as Gypsy or Irish Traveller men (43%) to be economically inactive, which means they were out of work and not looking for work.

7.3 Economic inactivity

There are a range of reasons why people can be economically inactive. The most common reason for Gypsy or Irish Travellers being economically inactive was looking after the home or family (27%). This is higher than the average for England and Wales (11%). The second most common reason was being long term sick or disabled (26%) – the highest percentage out of all ethnic groups.

8. Home ownership data

Figure 5: home ownership and renting among gypsy or irish traveller households and all households, table 5: home ownership and renting among gypsy or irish traveller households and all households.

Source: England, 2011 Census

In 2011, 34% of Gypsy or Irish Traveller households owned their own home, compared with a national average of 64%. 42% lived in social rented accommodation, compared with a national average of 18%.

In 2016 to 2017, 0.1% of new social housing lettings went to people from Gypsy or Irish Traveller backgrounds (429 lettings).

In 2011, a whole house or bungalow was the most common type of accommodation for Gypsy or Irish Traveller households (61%). This was lower than for all usual residents in England and Wales (84%).

Caravans or other mobile or temporary homes accounted for 24% of Gypsy or Irish Travellers accommodation, a far higher percentage than for the whole of England and Wales (0.3%).

The percentage of people living in a flat, maisonette or apartment was 15% for both Gypsy or Irish Travellers and all usual residents in England and Wales.

In 2011, 14.1% of Gypsy and Irish Traveller people in England and Wales rated their health as bad or very bad, compared with 5.6% on average for all ethnic groups.

In 2016 to 2017, Gypsy or Irish Traveller people aged 65 and over had the lowest health-related quality of life of all ethnic groups (average score of 0.509 out of 1). The quality of life scores for the White Gypsy or Irish Traveller ethnic group are based on a small number of responses (around 35 each year) and are less reliable as a result.

Ethnicity facts and figures has information on satisfaction of different health services for different ethnic groups. For the results presented below, the Gypsy or Irish Traveller figures are based on a relatively small number of respondents, and are less reliable than figures for other ethnic groups.

In 2014 to 2015 (the most recent data available), these groups were the most satisfied with their experience of GP-out-of-hours service , with 75.2% reporting a positive experience.

In 2018 to 2019, they were less satisfied with their experience of GP services than most ethnic groups – 73.0% reported a positive experience.

They were also among the groups that had least success when booking an NHS dentist appointment – 89.0% reported successfully booking an appointment in 2018 to 2019.

The Gypsy or Irish Traveller group were also less satisfied with their access to GP services in 2018 to 2019 – 56.9% reported a positive experience of making a GP appointment, compared to an average of 67.4% for all respondents.

Publication release date: 31 January 2022

Updated: 29 March 2022

29 March 2022: Corrected A-level data in Table 3, and All ethnic groups data in Table 4. Corrected the legend in Figure 1 (map).

31 January 2022: Initial publication.

The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!

Irish Travelers and Roma: Exploring the Differences in Culture, Social Norms, and Economic Status

By Happy Sharer

Introduction

Irish Travelers and Roma are two distinct ethnic groups with a shared history and experience of marginalization in Europe. Although they have faced similar forms of discrimination, there are significant cultural and social differences between them. This article will explore these differences in more detail, as well as examining the impact of discrimination on Irish Travelers and Roma in modern society.

A Historical Perspective on Irish Travelers and Roma

The origins of Irish Travelers and Roma are intertwined. Both groups trace their roots back to 16th century India, where their ancestors were nomadic traders and entertainers. Over time, these groups began to migrate westward, eventually settling in different parts of Europe.

The Irish Travelers primarily settled in Ireland and the United Kingdom, while the Roma spread out across Europe. Despite their different settlement patterns, both groups experienced similar forms of discrimination, often being treated as second-class citizens or even outlaws. This was exacerbated by events such as the Irish Famine and World War II, which caused further displacement and hardship for both communities.

Exploring the Cultural Differences Between Irish Travelers and Roma

The Irish Travelers and Roma have developed distinct cultures over the centuries. Language is one of the most obvious differences between the two groups. The Irish Travelers speak a dialect of English known as Shelta, while the Roma have their own language called Romani.

Clothing and adornment also vary significantly between the two groups. The Irish Travelers tend to dress in bright colors, often wearing skirts and dresses. They also decorate their clothing with intricate embroidery and beading. In contrast, the Roma typically dress in dark colors and favor loose-fitting garments such as trousers or tunics.

Music and dance are important aspects of both cultures, though the styles differ. Irish Travelers are known for their traditional folk songs and jigs, while the Roma are renowned for their lively Gypsy music. Both groups also share a love of storytelling, which is an integral part of their oral traditions.

Differences in Social Norms and Customs of Irish Travelers and Roma

The Irish Travelers and Roma have distinct social customs and norms. Marriage and family structure vary between the two groups. For example, Irish Travelers practice arranged marriage, while the Roma prefer to marry within the same clan. Similarly, the gender roles of Irish Travelers and Roma are distinct. In Irish Traveler culture, women are responsible for domestic duties, while men work outside the home. In contrast, Roma women are expected to contribute to the household income, while men are responsible for protecting the family.

Social interaction is another area where the two groups differ. Irish Travelers tend to be more open and welcoming to outsiders, while the Roma are more guarded and suspicious. This can make it difficult for non-Roma people to gain acceptance into a Roma community.

Impact of Discrimination Against Irish Travelers and Roma in Modern Society

Despite the progress made in recent years, both Irish Travelers and Roma continue to face discrimination in many areas of society. Education is one area where this is particularly evident. Irish Travelers and Roma often experience difficulty in accessing quality education due to poverty and prejudice. This can limit their employment opportunities, leading to higher levels of unemployment.

Discrimination in housing is another issue faced by both communities. Irish Travelers and Roma are often denied access to public housing due to negative stereotypes and prejudice. This can lead to overcrowding and poor living conditions, further exacerbating existing problems.

Examining the Role of Education for Irish Travelers and Roma

Education can play a key role in improving the lives of Irish Travelers and Roma. Access to quality education is essential for both groups, as it can provide valuable skills and knowledge that can help them escape poverty and discrimination. However, there are still many challenges that need to be overcome. These include low levels of literacy, lack of access to resources, and limited teacher training.

It is also important to ensure that educational materials and curricula accurately reflect the experiences of Irish Travelers and Roma. This can help to challenge negative stereotypes and create a more inclusive learning environment. Additionally, providing support and mentorship to young Irish Travelers and Roma can help to nurture their talents and ambitions.

Investigating the Economic Status of Irish Travelers and Roma

The economic status of Irish Travelers and Roma is often precarious. Both groups rely heavily on informal sources of income, such as trading and manual labor. This can make them vulnerable to exploitation, as they are often unable to access mainstream sources of employment due to prejudice and discrimination.

In addition, Irish Travelers and Roma often struggle to obtain credit and loans from banks, making it difficult for them to start businesses or purchase property. This has led to high levels of poverty amongst both communities, which in turn can lead to other issues such as poor health and homelessness.

Exploring the Religious Beliefs and Practices of Irish Travelers and Roma

Religion is an important part of both Irish Traveler and Roma culture. Both groups hold traditional beliefs in addition to Christianity. For example, Irish Travelers believe in fairies and other supernatural beings, while the Roma practice a form of animism that involves venerating nature spirits.

Christianity has had a profound influence on both cultures. Many Irish Travelers and Roma have adopted Christian values and practices, while still retaining elements of their traditional beliefs. This process of syncretism has resulted in a unique blend of religious beliefs and practices.

Irish Travelers and Roma have much in common, yet there are also significant differences between them. These differences can be seen in their cultures, social norms, and economic status. Unfortunately, both communities continue to face discrimination and prejudice in modern society, which has had a detrimental effect on their lives.

Education is one way to address this problem. By ensuring that Irish Travelers and Roma have access to quality education and challenging negative stereotypes, we can create a more inclusive and equitable society. Additionally, providing economic opportunities and support to both communities can help to improve their lives and reduce poverty.

(Note: Is this article not meeting your expectations? Do you have knowledge or insights to share? Unlock new opportunities and expand your reach by joining our authors team. Click Registration to join us and share your expertise with our readers.)

Hi, I'm Happy Sharer and I love sharing interesting and useful knowledge with others. I have a passion for learning and enjoy explaining complex concepts in a simple way.

Related Post

Exploring japan: a comprehensive guide for your memorable journey, your ultimate guide to packing for a perfect trip to hawaii, the ultimate packing checklist: essentials for a week-long work trip, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Expert Guide: Removing Gel Nail Polish at Home Safely

Trading crypto in bull and bear markets: a comprehensive examination of the differences, making croatia travel arrangements, make their day extra special: celebrate with a customized cake.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Picture Show

Daily picture show, documenting the irish travellers: a nomadic culture of yore.

Lauren Rock

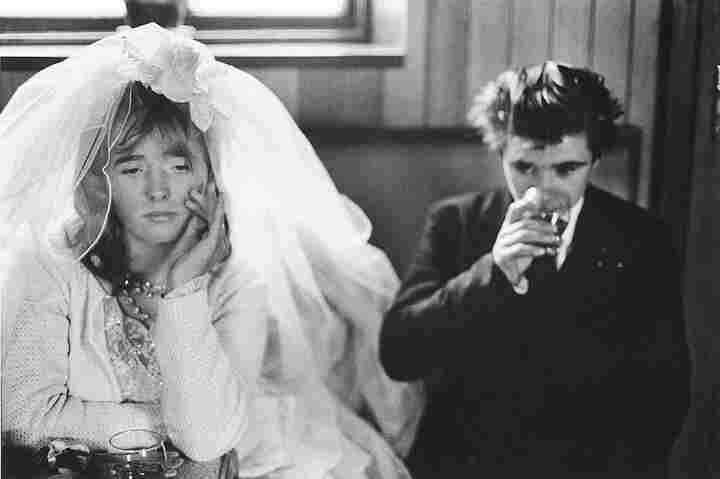

Throughout my life I have regularly traveled to my mother's home city of Dublin. During these trips I would regularly see groups of people living in caravans on the sides of the road, and I always wondered who they were and what their lives were like.

I later found out they belonged to a small ethnic minority called "Travellers" — nomads who spend most of their life, literally on the road. While their history has been hard to document — they have no written records — they are thought to have separated from the settled Irish community at least 1,000 years ago.

The Travellers (until recently also called "tinkers" or "gypsies") often live in ad hoc encampments, in direct contrast to "settled" people in Ireland. They are thought to be descended from a group of nomadic craftsman, with the name "tinker" a reference to the sound of a hammer hitting an anvil. (The reference is now considered derogatory.)

In 1965 Dublin-born photographer Alen MacWeeney stumbled across a Travellers' encampment and became fascinated with their way of life. He spent the next six years making photographs and recording their stories and music. Despite shooting the photos in the late '60s, it wasn't until 2007 that he found a publisher for his work.

Bernie Ward, Cherry Orchard Courtesy of Alen MacWeeney hide caption

Bernie Ward, Cherry Orchard

In his book, Irish Travellers: Tinkers No More — which also comes with a CD of Traveller music recordings — MacWeeny shows us a gritty, intimate portrait of the people he eventually came to call friends. He compares the Travellers to the migrant farmers of the American Depression: "poor, white, and dispossessed."

"Theirs was a bigger way of life than mine, with its daily struggle for survival, compared to my struggle to find images symbolic and representative of that life," he said in his book.

MacWeeney got his start at age 20 as an assistant for Richard Avedon in Paris and has since made a career as a portrait and fashion photographer. But his images of the Travellers reveal a raw and intimate side to his work.

"Traveller families have always been very close-knit, held together in a tight unspoken knot, with lifelong bonds and sometimes varying a lifelong set of troubles," he said.

Today, however, the Traveller lifestyle has changed dramatically from even a few decades ago. Many have embraced modern culture and become "settled," no longer living apart from the mainstream. There is even a reality TV show, My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding , which showcases Traveller girls and their theatrical, over-the-top weddings.

But MacWeeney believes that the Travellers are "reluctant as settled and envy the other life of travelling." His book stands as a document of an era, and a way of life that is slowly fading into the past.

To renew a subscription please login first

- Search for:

- About History Ireland

- Hedge Schools

- World War I

- Revolutionary Period 1912-23

- Devalera & Fianna Fail

- The Emergency

- Troubles in Northern Ireland

- Celtic Tiger

- 20th Century Social Perspectives

- Grattan’s Parliament

- The United Irishmen

- The Act of Union

- Robert Emmet

- Catholic Emancipation

- 1848 Rebellion

- Irish Republican Brotherhood / Fenians

- The Land League

- Parnell & his Party

- Gaelic Revival

- 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives

- The Reformation

- Hugh O’Neill

- Plantation of Ireland

- 1641 Rebellion

- Confederate War and Cromwell

- Williamite Wars

- Early Modern History Social Perspectives

- Gaelic Ireland

- Anglo-Norman Ireland

- Bruce Invasion

- Medieval Social Perspectives

- Pre-history / Archaeology

- Pre-Norman Social Perspectives

- Digital Edition

GYPSIES IN IRELAND—A HIBERNO-ROMANY COMMUNITY

By David Joyce

Above: A mid-nineteenth-century colour plate of ‘Epping Forest Gypsies’, a noted group of Romani who travelled around Britain and began ‘opening’ their campsites to visitors sometime in the early 1860s.

‘Travelling community’ is used as an all-encompassing term in Ireland to describe a traditionally nomadic community that has a significant degree of internal diversity. Encompassed within the term are distinct groups, namely Mincéirí or Pavee and Romani travellers. Mincéirí or Pavee are used interchangeably as a self-descriptive term by Irish Travellers; Romany/Romani is a self-descriptive term used by English Gypsies. What are the origins in Ireland of the small but distinct Hiberno-Romany community?

Romani history in Britain has been widely studied and there is a growing body of study in relation to Mincéirí in Ireland and Britain, but the study of Romani in Ireland has been neglected. When writing about the ‘Travelling community’ in Ireland, many writers repetitively cite limited sources that suggest that Romani never lived or travelled in Ireland until appearing briefly at the outbreak of the First World War, suggesting that they migrated to Ireland to avoid military conscription in Britain. While some families did move to Ireland during the Great War, Romani families had already developed travel circuits within Ireland from the late 1860s. By the early 1940s many of these families had been connected to Ireland for at least two or three generations and began to form a distinct Hiberno-Romany community.

THE ORIGINS OF THE ROMANY COMMUNITY IN IRELAND

The first explicit reference to the presence of Romani in Ireland dates from the early sixteenth century. The Fiants of Henry VIII in 1541 record ‘Safe conduct, for 40 days, for John Naune and his company, Egyptians, driven from Scotland by stress of weather’. ‘Egyptian’ was a term for Romani in the sixteenth century, based on the unfounded belief that the wanderers then arriving in Western Europe were ‘pilgrims’ originating from Egypt. The word ‘Gypsy’ derives from the various spellings used— Egipcian , Egypcian , ’ gypcian . This record of Romani in Ireland in 1541 is contemporaneous with the first records of Romani in Scotland and England in the early sixteenth century and coincides with the introduction of punitive laws designed to deter Gypsies from entering or remaining in Scotland ‘on pain of death’.

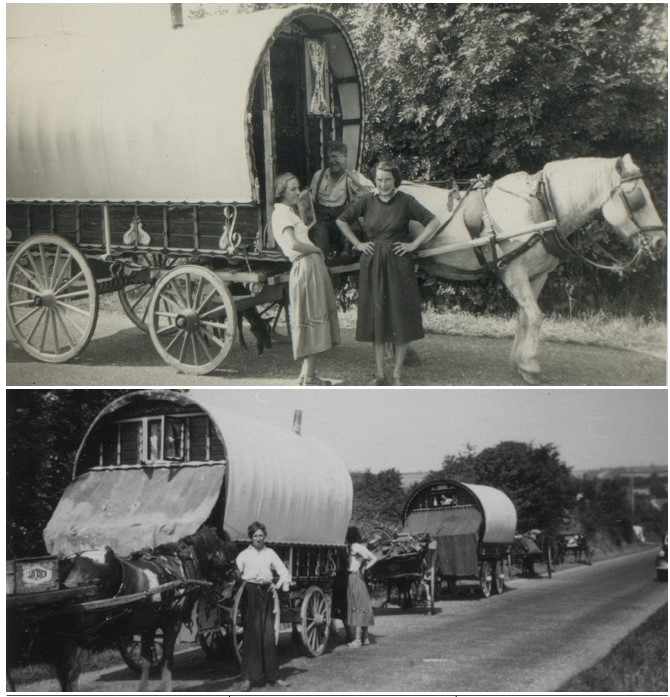

Above: The Gentles—seen here on the road near Kinsale, Co. Cork, in the 1950s—were Welsh Romani who had travelled in Ireland since the 1890s. (University of Liverpool)

It is suggested that the appearance of Romani in Ireland in the 1540s was almost certainly an aberration and they did not establish a permanent presence. There is little reference or evidence of Romani in Ireland in the succeeding centuries. It is not until the nineteenth century that verifiable records of Romani in Ireland appear.

THE ROMANY COMMUNITY IN IRELAND IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

One such record of a transitory family of Romani is from 1866, when a group of families temporarily disembarked from a steamship in Queenstown (Cobh). The ship was bound for the United States but docked in Queenstown for repairs. The families were said to be emigrating because the enclosure of commonage in England made nomadism increasingly difficult. They families stated that ‘the prejudice which is gradually rising against them’ was another reason they were leaving England. Unfortunately, the prejudice experienced in England was repeated in Cork. When they sought to set up a campsite on the outskirts of Cobh, a large crowd of locals prevented them from doing so. It was reported that locals had gathered ‘en masse’ and hunted them for a couple of miles around the countryside, not allowing them to pitch their tents anywhere. The families were forced back into Queenstown, where they slept on the streets until the ship departed.

The first appearance of Romani living in a ‘gypsy caravan or vardo’ dates from 1868 in Belfast. A group of families calling themselves ‘the Original Norwood and Epping Forest Gipsies’ are described as ‘causing a great attraction in the city’. The camp was recorded as having three ‘caravans’ and a number of tents. The same group later moved to Dublin, where their camp at the Rotunda Gardens was open to the public, who were charged sixpence for admission.

The ‘gipsy caravan’, or vardo in the Romani language, as a form of accommodation dates from the early 1840s. The first living vans were large transport wagons that combined storage and living space into one vehicle pulled by a team of horses and used as living accommodation in France in the 1810s by non-Romani circus troupes. By the mid-1800s they had become smaller, pulled by a single horse. In the mid-1840s Romani in Britain started using vardos, adding their own characteristic style of decoration.

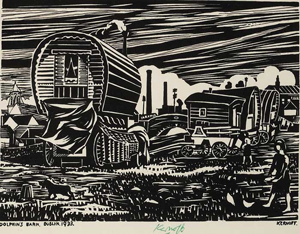

Above: Harry Kernoff’s woodcut ‘Dolphin’s Barn, Dublin, 1933’, a regular Romany campsite.

The Epping Forest Gypsies were a noted group of Romani who travelled around Britain and began ‘opening’ their campsites to visitors sometime in the early 1860s. Many of them were musicians and put on shows and dances as well as engaging in fortune-telling and selling their handmade wickerwork products from their campsites. George ‘Lazzy’ Smith, an entrepreneurial Romany, claimed to have originated the idea of charging members of the public to see inside their tents and attend the dances. When he noticed the interest in the arrival of Romani in towns around England, to ‘the extent that onlookers would not keep out of their tents even at meal-times’ , he decided to profit from this curiosity.

The arrival of the group in Belfast was clearly a ‘commercial operation’ with an element of carnival attached. The Epping families returned to Ireland in March 1870, visiting Cork and Limerick. In a lengthy report in the Freeman’s Journal on the arrival of the group in Dublin in September 1868 entitled ‘The Gipsies in Ireland’, it was stated ‘that we now have a veritable gipsy encampment in Ireland, the first, according to certain statements, that ever visited this kingdom’. The writer questioned the veracity of the claim and drew a comparison between the way of life of Romani and ‘tinkers’, and the article colourfully ponders whether ‘gipsies’ were present in Ireland from an earlier era. The writer stated that an ‘examination of the habits and manners of the tinkers’ then travelling around Ireland as tinsmiths and horse-dealers suggested ‘that the race had, in common with more objectionable ones, made a settlement in our midst. They took kindly to the soil, and learned the use of the blackthorn, adopting also the native patois—Indeed they became what the English call “more Irish than the Irish”.’ The direct comparison between ‘tinkers’ and Romani suggests that Irish Travellers had been living in distinct campsites using tents for many years prior to the arrival of the ‘Gipsies’.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A HIBERNO-ROMANY COMMUNITY, 1870s–1900

Apart from his connections to the Epping Forest group, Lazzy Smith frequently travelled around Ireland as a horse-dealer, and several of his children were born in Ireland. Other Romani families also came to Ireland to pursue economic opportunities. By the late 1860s Romani hawkers and horse-dealers in single families or small family groups with horse-drawn caravans and tents became a presence on the roads of Ireland. Families recorded around that time included Smiths, Lees, Palmers and Reynoldses.

One significant record of Romani hawkers in Ireland comes from a court case in 1874. This case is an early example of Travellers, either Romani or Mincéirí, resorting to the superior courts to assert a legal right. It is also an example of holding Travellers collectively responsible for the actions of an individual from within the community.

The case was taken by William Smith and his mother Eliza against Robert Talbot, a draper from Westport, Co. Mayo. The Smiths were described in court records as ‘English gipsies’. Talbot had the previous November obtained a court order allowing the county sheriff to seize the property of the Smiths in satisfaction of a debt run up by the Smiths’ in-law John Lee. The property consisted of the family’s caravan, tent, cart, harness, horse, clothes and other personal property. The Smiths had been camped at Temple Road, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, when their property was seized. The court heard that William Smith and his mother, together with other family members, had previously been camping in Westport, where John Lee had become indebted to Talbot for £40 for blankets that he had bought to sell on as a hawker. Lee had married William Smith’s sister sometime previously and had been unsuccessful as a horse-dealer. The Lees returned to the Smiths’ camp and were allowed to reside there but had no property in it. The Smiths argued that ‘the transaction between Lee and Talbot was entirely unconnected with them and imposed no liability on the Smiths’. The jury held in favour of the Smiths and the court ordered the return of their property.

In July 1876 possibly the same John Lee was involved in an incident in Portadown, Co. Armagh. Lee, the head of a ‘Gipsy encampment’, was the victim of an assault when five men entered his camp and severely beat him. It appeared that a horse belonging to Lee had somehow torn the coat of one of the men earlier in the day at a nearby water pump; during this incident he exchanged words with Lee, before returning later with four other men. The group were convicted and fined.

By the 1890s Romani travelling in vardos were a common sight. One of the first fatal accidents involving a vardo is recorded in County Cork in 1897, where the death of teenager Charlotte Jones occurred. Charlotte was the niece of William Gentle, a Welsh Romany who had been travelling with his family in Ireland from around 1890. On the evening of 12 March 1897 they were encamped near Kinsale when strong winds overturned one of the caravans and crushed the unfortunate Charlotte to death. The extended Gentle family were recorded later in 1897 in occupation of three caravans at Rathkeale, Co. Limerick.

THE ROMANY COMMUNITY IN IRELAND, 1900–1960s

Above: Members of the Taylor family in front of their vardo in Gardiner Street in 1952. (Historical Picture Archive)

The Gentles, Smiths, Lees, Wilsons, Webbs, Reis, Boswells and Brasils, among other families, had established routes and stopping places around Ireland by the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of these families are recorded in the 1901 and 1911 censuses. Members of the Webb, Wilson and Smith families were among the few travelling families recorded in occupation of a ‘Gipsy wagon’ or vardo in the 1911 census.

It is widely accepted that Mincéirí did not use horse-drawn wagons as living accommodation until the mid-1910s. Just as the Romani had adapted the wagon from circus folk, it is suggested that Mincéirí adapted the wagon from Romani who had begun travelling with them in Ireland during the Great War. Given, however, that Romani vardos had a presence in Ireland for much of the previous 40 years, it is likely that some Mincéirí, particularly wealthier families, may have been using them from an earlier period.

Irish Travellers almost exclusively opted for the canvas-covered bow-top wagon rather than the square-sided Reading- or Burton-type vardo, a style of van more evocative of the Romani community. The bow-top had a number of advantages over other types of van in terms of cost and weight; in addition, because of its simpler design it was easier to construct than the more elaborate and ornate vardos.

Many of the campsites of Romani, particularly during the wintertime, were in urban areas. Parts of Dublin from Dolphin’s Barn inwards toward the Liberties and stretching across the river to Gardiner Street, Dorset Street and Ballybough were well-known stopping places. One of the better known of these campsites was at Dolphin’s Barn Bridge, where the death of two little Romany girls, Eileen and Kathleen Riley, was recorded in March 1915, when the bender tent they were living in caught fire. The stopping place at Dolphin’s Barn was later depicted by the artist Harry Kernoff in his evocative woodcut ‘Dolphin’s Barn, Dublin, 1933’.

The presence of a significant number of Romany families in Dublin during the 1930s and 1940s was recorded by the Irish Press and Irish Times respectively. In 1936 the Irish Press reported on a number of families in Gardiner Street, where nine caravans were on a campsite. In 1945 the Irish Times met and identified a number of families and campsites, including Taylors, Bolands, Scotts and Dalys on Gardiner Street, O’Neills on Dorset Street, Webbs at Thomas Street, and the Riley and Sturgeon families in Harold’s Cross. It was noted that the Taylor family had been living on the site in Gardiner Street for more than fourteen years.

The stopping places of the Romany families in the environs of Dublin city and other parts of the country are now forgotten, and many of the families who lived and travelled in Ireland from about the 1870s until the 1950s appear to have migrated to Britain during the 1950s and ’60s, a migration in which many Mincéirí also took part. Some, however, married into non-Romany families in the parts of Dublin and other parts of the country in which they lived and became assimilated into those neighbourhoods. A number of families remain in Ireland, north and south, and proudly identify as Irish Romany.

David Joyce is a solicitor and a member of the Irish Traveller community.

Further reading A. Bhreatnach, Becoming conspicuous: Irish Travellers, society and the state 1922–70 (Dublin, 2007). J. Helleiner, Irish Travellers: racism and the politics of culture (Toronto, 2000). M. McCann, S. Ó Síocháin & J. Ruane (eds), Irish Travellers, culture and ethnicity (Belfast, 1994). S. ní Shuinéar, ‘Apocrypha to canon: inventing Irish Traveller history’, History Ireland 12 (4) (2004). G. Power, ‘Gypsies and sixteenth-century Ireland’, Romani Studies 24 (2) (2014).

Personal Histories

On this day.

- 1940 Three women were killed when a German bomb struck a creamery at Campile, Co. Wexford.

September 02

- 1666 The Great Fire of London, which destroyed 400 acres of the city but cost just nine lives, began in a bakehouse in Pudding Lane.

- 1022 Malachy the Great (Máel-Sechnaill), High King of Ireland since c. 980, died on Lough Ennell, Co. Westmeath.

- 1945 Japanese representatives sign the official ‘Instrument of surrender’ on board the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, thus confirming the formal end of the Second World War.

September 13

- 1919 Detective John Hoey, who identified Seán MacDiarmada for the military in 1916, was shot dead outside police HQ in Brunswick Street, Dublin.

- 1819 James Hack Tuke, Quaker, best remembered for his philanthropic work in Ireland during the Great Famine, born in York.

- 1968 The first Merriman Summer School opened in Ennis, Co. Clare.

- 1916 Roald Dahl, novelist, poet and short-story writer, renowned for his darkly comic children’s books, born in Wales to Norwegian parents.

- 1868 Richard Rothwell (67), Athlone-born romantic painter, died in Rome. His funeral and burial beside the poet John Keats in the city’s Protestant Cemetery were arranged by the painter Joseph Severn.

- 1860 John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, leader of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I who was regarded as a mentor by the generation of US generals who led US forces in Europe during World War II, was born in Laclede, Missouri. He was the only person to be promoted in his own lifetime to the highest rank ever held in the United States Army—General of the Armies.

- 1803 County Wexford-born Commodore John Barry, ‘Father of the American Navy’, died in Philadelphia.

- 1803 Death of John Barry in Philadelphia. Born in Wexford in 1745, he had emigrated there and embarked on a career as a merchant and naval mariner that led to his becoming the first commander of the US Navy after its establishment in 1794.

- 1967 Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara (39), Argentine Marxist revolutionary, was captured and summarily executed by CIA-backed Bolivian forces.

- 1966 David Cameron, Conservative MP for Witney since 2001 and prime minister of the United Kingdom (2010–16), born in Marylebone, London, the son of a stockbroker.

- 1958 Pope Pius XII (82), head of the Catholic Church during the Second World War, died.

- 1932 A Cumann na nGaedheal meeting in Kilmallock, Co. Limerick, was attacked by hundreds of republicans who were beaten back by members of the Army Comrades’ Association (Blueshirts).

- 1940 Birth of John Lennon, future Beatle, in Liverpool.

- A Brief History Of Irish...

A Brief History of Irish Travellers, Ireland’s Only Indigenous Minority

After a long battle, Irish Travellers were finally officially recognised as an indigenous ethnic minority by Ireland’s government in early March 2017. Here, Culture Trip takes a look at the origins of the Irish Travelling community and how the historic ruling came about. At the time of the 2011 census , there were around 29,500 Irish Travellers in the Irish Republic , making up 0.6% of the population. The community was found to be unevenly distributed across the country, with the highest number living in County Galway and South Dublin. Although – as the name suggests – Irish Travellers have historically been a nomadic people, the census showed a majority living in private dwellings.

Throughout Irish history, the Travelling community has been markedly separated from the general Irish population, resulting in widespread stereotyping and discrimination. The same year as the census, a survey conducted by Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute found that Irish Travellers suffer widespread ostracism; this and other factors have been shown to contribute to high levels of mental health problems among Irish Travellers. Indeed, the 2010 All Ireland Traveller Health Study found their suicide rate to be six times the national average, accounting for a shocking 11% of Traveller deaths.

Through the 2011 census, members of the Travelling community were also found to have poorer general health, higher rates of disability and significantly lower levels of education as compared to the general population, with seven out of 10 Irish Travellers educated only to primary level or lower.

Because of a lack of written history, the exact origins of the Irish Travelling Community have been difficult to clarify. Although it had been hypothesised, until relatively recently, that Irish Travellers may be linked to the Romani people, a genetic study released in February of this year revealed this connection to be false.

The study found that Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin, but split off from the general population sometime around the mid-1600s – much earlier than had been thought previously. In one widely quoted finding, the DNA comparisons conducted in the course of the research found that while Irish Travellers originated in Ireland, they are genetically different from ‘settled’ Irish people, to the same degree as people from Spain.

The results of the study, conducted by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, University College Dublin, the University of Edinburgh and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, contributed significantly to Irish Travellers being officially designated an ethnic minority, defined as a group within a community with different national or cultural traditions from the main population.

Speaking to RTE on the day of the ruling, former director of the Irish Traveller Movement Brigid Quilligan said, ‘We want every Traveller in Ireland to be proud of who they are and to say that we’re not a failed set of people. We have our own unique identity, and we shouldn’t take on all of the negative aspects of what people think about us. We should be able to be proud and for that to happen our State needed to acknowledge our identity and our ethnicity, and they’re doing that today.’

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to $1,200 on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Guides & Tips

Somewhere wonderful in ireland is waiting.

Top Tips for Travelling in Ireland

Places to Stay

The best hotels to book in killarney, ireland, for every traveller.

These Are the Places You Need to Go on St Patrick’s Day

History and Culture on an Ireland Road Trip

The Best Cheap Hotels to Book in Killarney, Ireland

The Best Hotels to Book in Ireland

Tourism Ireland Promotion Terms & Conditions Culture Trip Ltd (Culture Trip)

Food & Drink

Combining ireland’s finest whiskey with sustainable forestry.

See & Do

24 hours in ireland’s second cities.

The Best Coastal Walks in the World

The Best Private Trips to Book For Your English Class

Culture Trip Summer Sale

Save up to $1,200 on our unique small-group trips! Limited spots.

- Post ID: 1176219

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Schools & departments

Gene study reveals Irish Travellers' ancestry

Irish Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin and have no particular genetic ties to European Roma groups, a DNA study has found.

The research offers the first estimates of when the community split from the settled Irish population, giving a rare glimpse into their history and heritage.

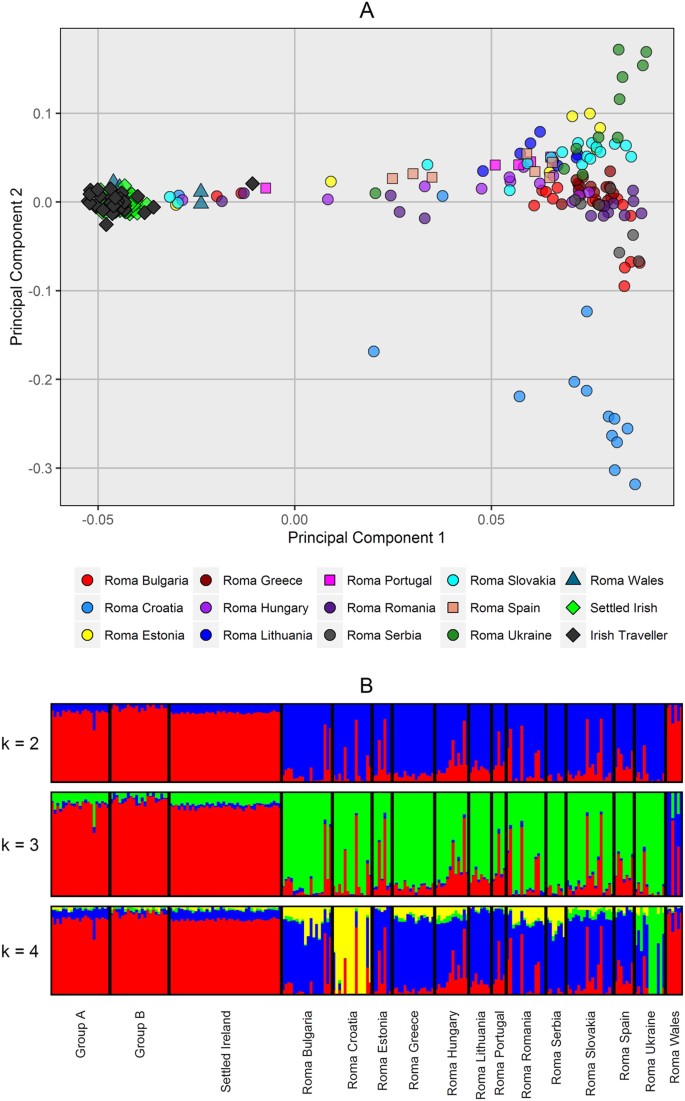

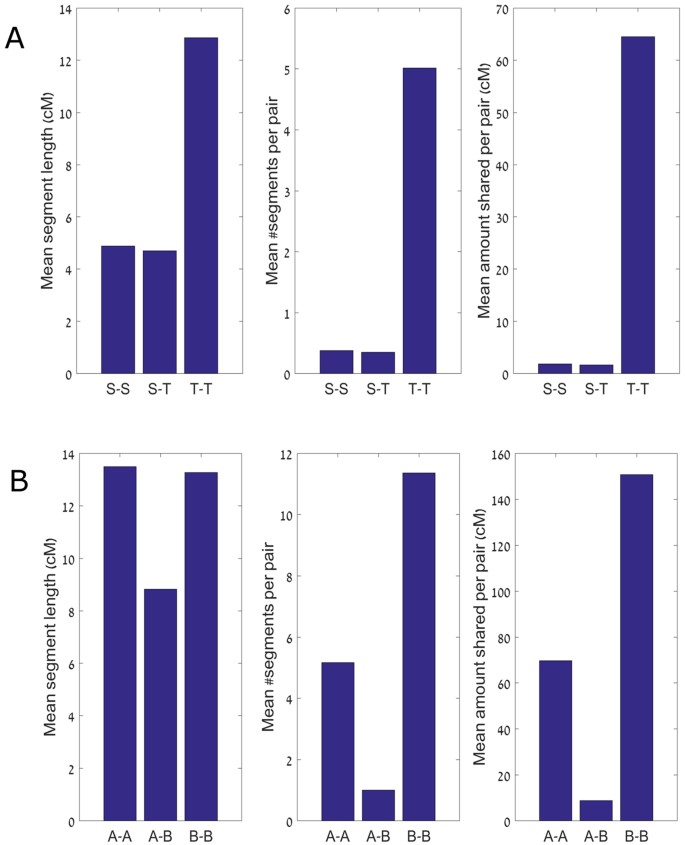

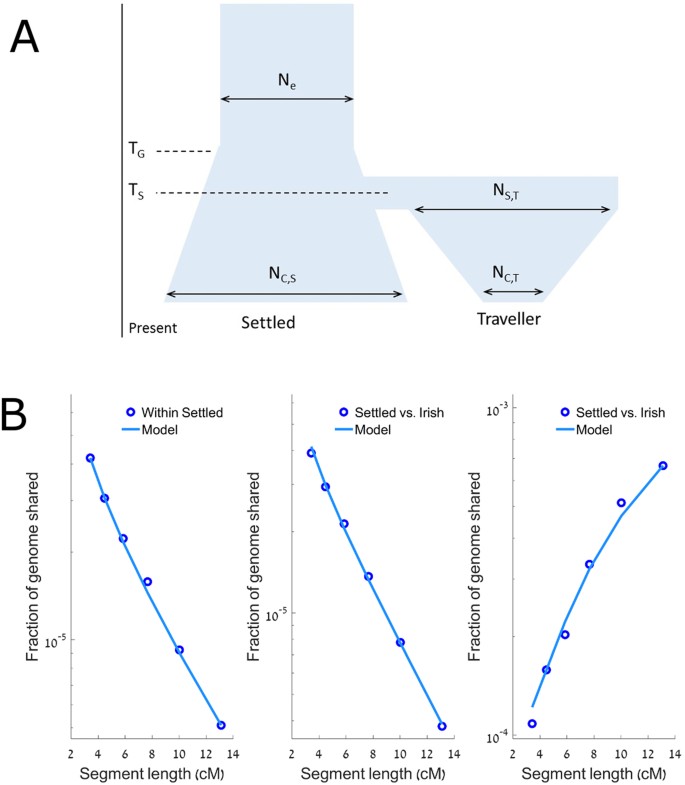

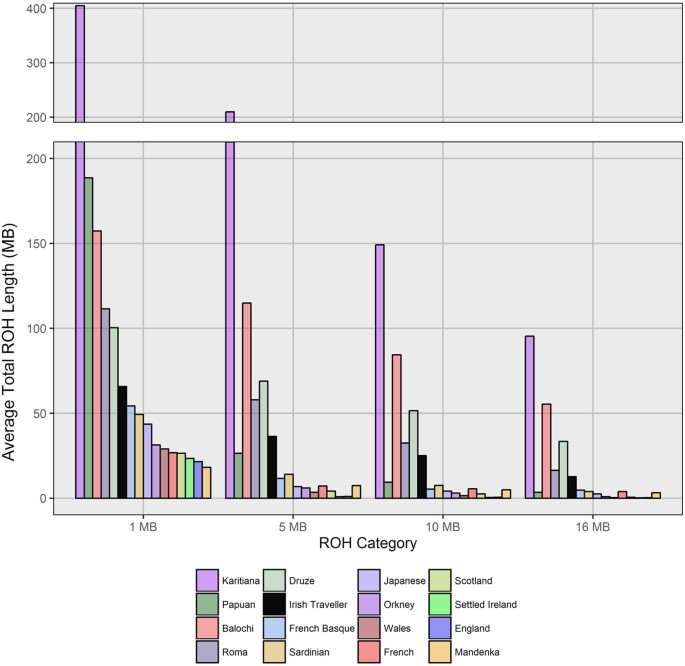

Researchers led by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) and the University of Edinburgh analysed genetic information from 42 people who identified as Irish Travellers.

The team compared variations in their DNA code with that of 143 European Roma, 2,232 settled Irish, 2,039 British and 6,255 European or worldwide individuals.

Irish ancestry

They found that Travellers are of Irish ancestral origin but have significant differences in their genetic make-up compared with the settled community.