Read the May magazine issue on food and climate change

United States nuclear weapons, 2024

By Hans M. Kristensen , Matt Korda , Eliana Johns , Mackenzie Knight | May 7, 2024

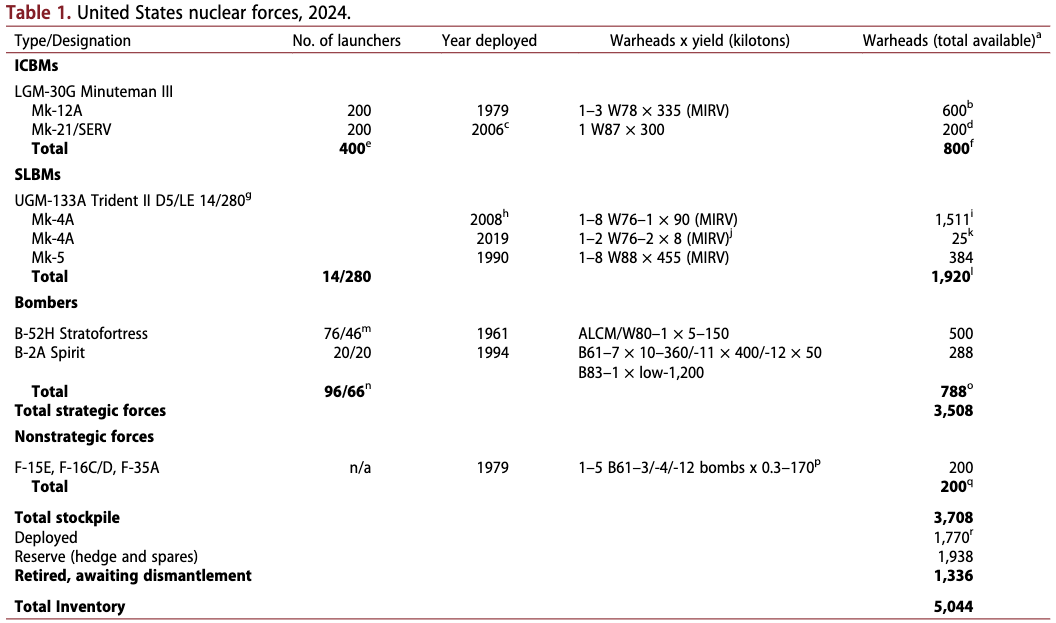

The United States has embarked on a wide-ranging nuclear modernization program that will ultimately see every nuclear delivery system replaced with newer versions over the coming decades. In this issue of the Nuclear Notebook, we estimate that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,708 warheads—an unchanged estimate from the previous year. Of these, only about 1,770 warheads are deployed, while approximately 1,938 are held in reserve. Additionally, approximately 1,336 retired warheads are awaiting dismantlement, giving a total inventory of approximately 5,044 nuclear warheads. Of the approximately 1,770 warheads that are deployed, 400 are on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, roughly 970 are on submarine-launched ballistic missiles, 300 are at bomber bases in the United States, and approximately 100 tactical bombs are at European bases. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, senior research fellow Matt Korda, research associate Eliana Johns, and program associate Mackenzie Knight.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link . To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, United States nuclear weapons, 2024, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , 80:3, 182-208, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2024.2339170

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dating back to 1987, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-notebook/ .

In May 2024, the US Department of Defense maintained an estimated stockpile of approximately 3,708 nuclear warheads for delivery by ballistic missiles and aircraft. Most of the warheads in the stockpile are not deployed but rather stored for potential upload onto missiles and aircraft as necessary. We estimate that approximately 1,770 warheads are currently deployed, of which roughly 1,370 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and another 300 at strategic bomber bases in the United States. An additional 100 tactical bombs are deployed at air bases in Europe. The remaining warheads—approximately 1,938—are in storage as a so-called “hedge” against technical or geopolitical surprises. Several hundred of those warheads are scheduled to be retired before 2030 (see Table 1).

While the majority of the United States’ warheads comprises the Department of Defense’s military stockpile, retired warheads under the custody of the Department of Energy awaiting dismantlement constitute a “significant fraction” of the United States’ total warhead inventory (US Department of Energy 2023b). Dismantlement operations include the disassembly of retired weapons into component parts that are then assigned for reuse, storage, surveillance, or for additional disassembly and subsequent disposition (US Department of Energy 2023b, 2–11). The pace of warhead dismantlement has slowed significantly in recent years: While the United States dismantled on average more than 1,000 warheads per year during the 1990s, in 2020 it dismantled only 184 warheads (US State Department 2021). According to the Department of Energy, “[d]ismantlement rates are affected by many factors, including appropriated program funding, logistics, legislation, policy, directives, weapon system complexity, and the availability of qualified personnel, equipment, and facilities” (US Department of Energy 2022, 2–15). The US Department of Energy stated in April 2023 that it “was on pace to complete the dismantlement of all warheads retired before Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 [Sep. 2008] by the end of FY 2022 [Aug. 2022]” but that the COVID-19 pandemic “delayed the dismantlement of a small number of these retired warheads until after FY 2022 [Aug. 2022]” (US Department of Energy 2023a, 2–12).

Based on these timelines and recent dismantlement rates, we estimate that the United States possesses approximately 1,336 retired—but still intact—warheads awaiting dismantlement, giving a total estimated US inventory of approximately 5,044 warheads.

Between 2010 and 2018, the US government publicly disclosed the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile; however, in 2019 and 2020, the Trump administration rejected requests from the Federation of American Scientists to declassify the latest stockpile numbers (Aftergood 2019; Kristensen 2019a, 2020b). In 2021, the Biden administration restored the United States’ previous transparency levels by declassifying both numbers for the entire history of the US nuclear arsenal until September 2020—including the missing years of the Trump administration. This effort revealed that the United States’ nuclear stockpile consisted of 3,750 warheads in September 2020—only 72 warheads fewer than the last number made available in September 2017 before the Trump administration reduced the US government’s transparency efforts (US State Department 2021). We estimate that the stockpile will continue to decline over the next decade as modernization programs consolidate the remaining warheads.

Following the Biden administration’s initial declassification in 2021, it has since denied successive annual requests from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the stockpile numbers for 2021, 2022, or 2023 (Kristensen 2023d). A decision to no longer declassify these numbers not only contradicts the Biden administration’s own recent practices, but also represents a return to Trump-era levels of nuclear opacity. Such increased nuclear secrecy undermines US calls for Russia and China to increase transparency of their nuclear forces.

The US nuclear weapons are thought to be stored at an estimated 24 geographical locations in 11 US states and five European countries (Kristensen and Korda 2019, 124). The number of locations will increase over the next decade as nuclear storage capacity is added to three bomber bases. The location with the most nuclear weapons by far is the large Kirtland Underground Munitions and Maintenance Storage Complex south of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Most of the weapons in this location are retired weapons awaiting dismantlement at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The state with the second-largest inventory is Washington, which is home to the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific and the ballistic missile submarines at Naval Submarine Base Kitsap. The submarines operating from this base carry more deployed nuclear weapons than any other base in the United States.

Implementing the New START treaty

The United States appears to be in compliance with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) limits. Although Russia “suspended” its participation in New START in February 2023, the United States publicly declared in May 2023 that it had 1,419 warheads attributed to 662 deployed ballistic missiles and heavy bombers as of March 1st, 2023 (US State Department 2023a). The United States initially said that it voluntarily released the numbers “[i]n the interest of transparency and the US commitment to responsible nuclear conduct.” However, the United States did not continue this practice beyond that initial exchange and has not published any aggregate numbers since May 2023 (US State Department 2023a).

The United States contends that Russia’s “suspension” of New START implementation is “legally invalid” (US State Department 2023c). In response, the United States adopted four countermeasures in 2023 that it claimed were fully consistent with international law 1) no longer providing biannual data updates to Russia; 2) withholding from Russia notifications regarding treaty-accountable items (i.e. missiles and launchers) required under the treaty; 3) refraining from facilitating inspection activities on US territory; and 4) not providing Russia with telemetric information on US ICBM and SLBM launches (US State Department 2023c).

The New START warhead numbers reported by the US State Department differ from the estimates presented in this Nuclear Notebook, though there are reasons for this. The New START counting rules artificially attribute one warhead to each deployed bomber, even though US bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances. Also, this Nuclear Notebook counts as deployed all weapons stored at bomber bases that can quickly be loaded onto the aircraft, as well as nonstrategic nuclear weapons at air bases in Europe. This provides a more realistic picture of the status of US deployed nuclear forces than the treaty’s artificial counting rules.

Since the treaty entered into force in February 2011, the biannual aggregate data show the United States has cut its arsenal by a total of 324 strategic launchers, reduced deployed launchers by 220 and the warheads attributed to them by 381 (US State Department 2011). The warhead reduction is modest, only equivalent to about 10 percent of the 3,708 warheads remaining in the US stockpile. The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) stated that “[t]he United States will field and maintain strategic nuclear delivery systems and deployed weapons in compliance with New START Treaty central limits as long as the Treaty remains in force” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20).

As of March 2023, the United States had 38 launchers and 131 warheads less than the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons but had 119 deployed launchers more than Russia—a significant gap that is just under the size of an entire US Air Force intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) wing. So far Russia has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers but instead has increased the portion of its missiles that can carry multiple warheads.

The New START treaty has proven useful so far in keeping a lid on both countries’ deployed strategic forces. But it expires in February 2026 and if it is not followed by a new agreement, both the United States and Russia could potentially increase their deployed nuclear arsenals by uploading several hundred of stored reserve warheads onto their launchers. Additionally, if the treaty’s verification and data-exchange arrangements are not replaced, both countries will lose important information about each other’s nuclear forces. Until the treaty’s so-called “suspension,” the United States and Russia had completed a combined 328 on-site inspections and exchanged 25,017 notifications (US State Department 2022).

Nuclear Posture Reviews and nuclear modernization programs

The Biden administration’s 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) was broadly consistent with the Trump administration’s 2018 NPR (albeit with minor adjustments), which in turn followed the broad outlines of the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR to modernize the entire nuclear weapons arsenal. Just like previous NPRs, the Biden administration’s NPR said the United States reserved the right to use nuclear weapons under “extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners” and rejected policies of nuclear “no-first-use” or “sole purpose” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 9). Even so, the 2022 NPR notes that the United States “retain[s] the goal of moving toward a sole purpose declaration and [it] will work with [its] Allies and partners to identify concrete steps that would allow [it] to do so” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 9) (For a detailed analysis of the 2022 NPR, see Kristensen and Korda 2022).

The most significant change between the Biden and Trump NPRs was the walking back of two Trump-era commitments—specifically, canceling the proposed nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) and continuing with the retirement of the B83–1 gravity bomb.

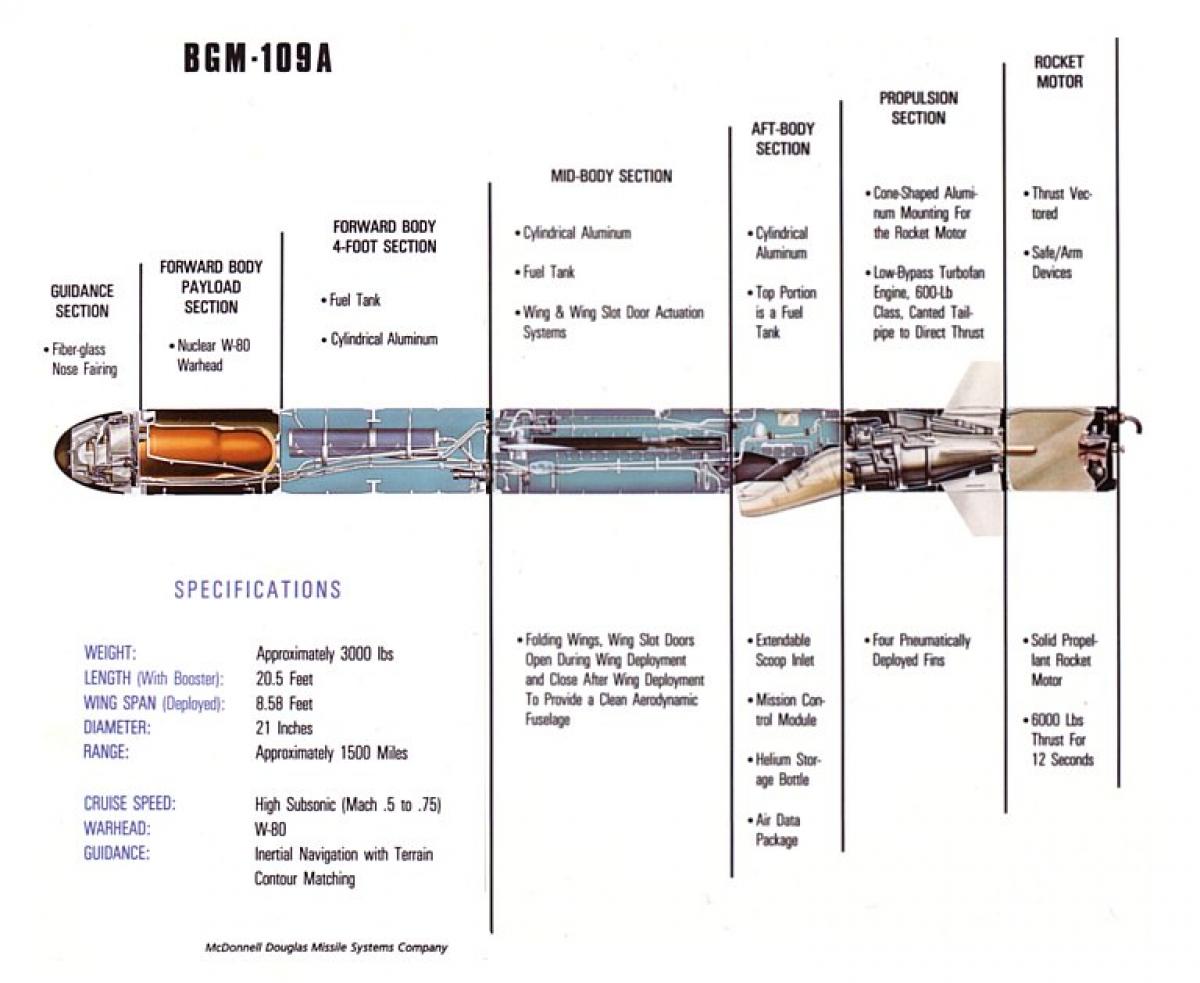

The Trump NPR had asserted that a SLCM-N with low-yield capability “may provide the necessary incentive for Russia to negotiate seriously a reduction of its nonstrategic nuclear weapons, just as the prior Western deployment of Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces [INF] in Europe led to the 1987 INF Treaty” (US Department of Defense 2018, 55). However, this has not proved to be the case. Furthermore, the theory that additional low-yield capabilities would somehow change Russia’s behavior seems flawed because the US arsenal already includes nearly 1,000 gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles, combined, with low-yield warhead options (Kristensen 2017b). Moreover, US Strategic Command has already strengthened strategic bombers’ support of NATO in response to Russia’s more provocative and aggressive behavior (see below): 46 B-52 bombers are currently equipped with the AGM-86B air-launched cruise missile and both the B-52 and the new B-21 bombers will receive the new AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), which will have very similar capabilities to the sea-launched cruise missile proposed by the 2018 NPR.

Furthermore, the US Navy used to have a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (the TLAM-N) but completed retirement of the system by 2013 because it was redundant and no longer needed. All other nonstrategic nuclear weapons—except gravity bombs for fighter-bombers—have also been retired because there was no longer any military need for them, despite Russia’s larger nonstrategic nuclear weapons arsenal. The suggestion that a US sea-launched cruise missile could motivate Russia to return to compliance with the INF Treaty was also flawed because Russia embarked upon its violation of the treaty at a time when the TLAM-N was still in the US arsenal; besides, the Trump administration ultimately withdrew the United States from the INF Treaty anyway. Development of a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile would violate the United States’ pledge made in the 1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiative not to develop any new types of nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (Koch 2012, 40), and could, if deployed in the Pacific, potentially also incite China to increase its regional nuclear capabilities.

One final argument against the sea-launched cruise missile is that nuclear-capable vessels triggered frequent and serious political disputes during the Cold War when they visited foreign ports in countries that did not allow nuclear weapons on their territory. In the case of New Zealand, diplomatic relations have only recently—some 30 years later—recovered from those disputes. And Iceland recently opened its ports to non-nuclear-armed attack submarines for the first time ever. Reconstitution of a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile would reintroduce this foreign relations irritant and needlessly complicate relations with key allied countries in Europe and Northeast Asia.

The Biden administration’s NPR echoed many of these arguments, concluding that the “SLCM-N was no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20). The Biden administration used even stronger language against the SLCM-N in an October 2022 statement suggesting that “the SLCM-N, which would not be delivered before the 2030s anyway, is unnecessary and potentially detrimental to other priorities” (US Office of Management and Budget 2022). In its statement, the administration noted that “[f]urther investment in developing SLCM-N would divert resources and focus from higher modernization priorities for the US nuclear enterprise and infrastructure, which is already stretched to capacity after decades of deferred investments. It would also impose operational challenges on the Navy” (US Office of Management and Budget 2022). This is because to carry nuclear weapons onboard, Navy crews would require specialized training and would need to adopt strict security protocols that could operationally hinder these multipurpose vessels (Woolf 2022). Additionally, deployed nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles would take the place of more flexible conventional munitions for vessels on patrol, thus incurring a substantial opportunity cost (Moulton 2022).

Despite the Biden administration’s conclusions, however, the SLCM-N may ultimately be funded through congressional intervention. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) authorized nominal funding for the system and required the establishment of a program of record for the SLCM-N, even though the Biden administration’s FY 2023 budget request recommended zeroing out the system’s funding entirely (US Congress 2023). The FY 2025 NDAA continued funding of the weapon and the administration accepted it but it remains to be seen whether the SLCM-N will ultimately be fielded given funding constraints and other priorities.

The Biden administration’s NPR also continued earlier plans to retire the B83-1 gravity bomb—the last nuclear weapon with a megaton-level yield in the US nuclear arsenal—“due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20). The Trump administration had put on hold previous plans to retire the B83–1 (US Department of Defense 2018).

The complete nuclear modernization and maintenance program will continue well beyond 2039 and, based on the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate, will cost $1.2 trillion over the next three decades. Notably, although the estimate accounts for inflation (Congressional Budget Office 2017), other estimates forecast that the total cost will be closer to $1.7 trillion (Arms Control Association 2017). Whatever the actual price tag will be, it is likely to increase over time, resulting in increased competition with conventional modernization programs planned for the same period.

In 2023, multiple governmental advisory commissions published reports intended to influence US nuclear posture. The Congressionally-mandated report on “America’s Strategic Posture,” published in October 2023, included a broad range of recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase the number of deployed warheads, as well as to scale up its production capacity of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warheads (US Strategic Posture Commission 2023). It also called for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal. In contrast, the US State Department’s International Security Advisory Board report on “Deterrence in a World of Nuclear Multipolarity” advised the United States to pursue competition with Russia and China “without accelerating arms race instability or risking runaway competition” (US State Department 2023b). While neither report represents official US government policy, the Strategic Posture Commission report’s status as a bipartisan document has been particularly useful for nuclear advocates to push for additional nuclear weapons (Heritage 2023; Hudson Institute 2023; Thropp 2023).

While additional modernization programs are being discussed, the National Nuclear Security Administration, or NNSA, delivered in 2023 more than 200 modernized nuclear weapons (B61–12 bombs and W88 Alt 370 warheads) to the Department of Defense (US Department of Energy 2024).

Nuclear planning and nuclear exercises

In addition to the Nuclear Posture Review, the nuclear arsenal and the role it plays is shaped by plans and exercises that create the strike plans and practice how to carry them out.

The current strategic nuclear war plan—OPLAN 8010–12—consists of “a family of plans” directed against four identified adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Known as “Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment,” OPLAN 8010–12 first entered into effect in July 2012 in response to operational order Global Citadel. The plan is flexible enough to absorb normal changes to the posture as they emerge, including those flowing from the NPR. Several updates have been made since 2012, but more substantial updates will trigger the publication of what is formally considered a “change.” The April 2019 change refocused the plan toward “great power competition,” incorporated a new cyber plan, and reportedly blurred the line between nuclear and conventional attacks by “fully incorporat[ing] non-nuclear weapons as an equal player” (Arkin and Ambinder 2022a, 2022b).

OPLAN 8010–12 also “emphasizes escalation control designed to end hostilities and resolve the conflict at the lowest practicable level” by developing “readily executable and adaptively planned response options to de-escalate, defend against, or defeat hostile adversary actions” (US Strategic Command 2012). While not new, these passages are notable, not least of which because the Trump administration’s NPR criticized Russia for an alleged willingness to use nuclear weapons in a similar manner, as part of a so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy.

The Nuclear Employment Strategy published by the Trump administration in 2020 reiterates this objective: “If deterrence fails, the United States will strive to end any conflict at the lowest level of damage possible and on the best achievable terms for the United States, and its allies, and partners. One of the means of achieving this is to respond in a manner intended to restore deterrence. To this end, elements of US nuclear forces are intended to provide limited, flexible, and graduated response options. Such options demonstrate the resolve, and the restraint, necessary for changing an adversary’s decision calculus regarding further escalation” (US Department of Defense 2020, 2). This objective is not just directed at nuclear attacks, as the 2018 NPR called for “expanding” US nuclear options against “non-nuclear strategic attacks.” The Biden administration is expected to complete its guidance in 2024.

OPLAN 8010–12 is a whole-of-government plan that includes the full spectrum of national power to affect potential adversaries. This integration of nuclear and conventional kinetic and non-kinetic strategic capabilities into one overall plan is a significant change from the strategic war plan of the Cold War that was almost entirely nuclear. In 2017, former US Strategic Command commander Gen. John Hyten explained the scope of modern strategic planning by saying:

I’ll just say that the plans that we have right now, one of the things that surprised me most when I took command on November 3 was the flexible options that are in all the plans today. So we actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, which is the Attorney General, Secretary of State, and everybody, I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the president on to give him options on what he would want to do …

The last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago, and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing. (Hyten 2017)

The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review and 2023 Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction reaffirm the importance of flexibility, integration, and tailored plans (US Department of Defense 2023f). To practice and fine-tune these plans, the armed forces conducted several nuclear-related exercises in 2023. In October 2023, Air Force Global Strike Command conducted exercise Prairie Vigilance, an annual nuclear bomber exercise at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota, which practiced the 5th Bomb Wing’s B-52 strategic readiness and nuclear generation operations (US Air Force 2023a).

The Vigilance exercises normally lead up to Strategic Command’s annual week-long Global Thunder large-scale exercise toward the end of the year, which “provides training opportunities that exercise all US Strategic Command mission areas, with a specific focus on nuclear readiness” (US Strategic Command 2021a). The exercise was most recently conducted in April 2023 at Minot AFB after being delayed in 2022 (US Air Force 2023d).

These exercises coincide with steadily increasing US bomber operations in Europe since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and again in 2022. Before that, one or two bombers would deploy for an exercise or airshow. But since then, the number of deployments and bombers has increased, and the mission has changed. Very quickly after the Russian annexation of Crimea, the US Strategic Command increased the role of nuclear bombers in support of the US European Command (Breedlove 2015), which, in 2016, put into effect a new standing war plan for the first time since the Cold War (Scapparotti 2017). Before 2018, the bomber operations were called the Bomber Assurance and Deterrence missions but have been redesigned as Bomber Task Force missions to bring a stronger offensive capability to the forward bases. Whereas the mission of Bomber Assurance and Deterrence was to train with allies and have a visible presence to deter Russia, the mission of the Bomber Task Force is to move a fully combat-ready bomber force into the European theater. “It’s no longer just to go partner with our NATO allies or to go over and have a visible presence of American air power,” according to the commander of the 2nd Bomb Wing. “That’s part of it, but we are also there to drop weapons if called to do so” (Wrightsman 2019). These changes are evident in the types of increasingly provocative bomber operations over Europe, in some cases very close to the Russian border (Kristensen 2022a). In October 2023, for example, a B-52 bomber from Barksdale AFB in Louisiana participated in NATO’s annual nuclear exercise Steadfast Noon, and in March 2023 a nuclear-capable B-52 cut south only a few kilometers from the Russian sea border and then flew south near Kaliningrad (Kristensen 2023a; NATO 2023).

These changes are important indications of how US strategy has changed in response to deteriorating East-West relations and the new “great power competition” and “strategic competition” strategy promoted by the Trump and Biden administrations, respectively. They also illustrate a growing integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities, as reflected in the new strategic war plan. B-52 Bomber Task Force deployments typically include a mix of nuclear-capable aircraft and aircraft that have been converted to conventional-only missions. With Sweden joining NATO, US strategic bombers now routinely operate over Swedish territory: In August 2022, for example, two B-52s—one version that is nuclear-capable and one that is de-nuclearized—overflew Sweden, the first overflight since it applied for NATO membership in May 2022 (Kristensen 2022c). On September 21, 2022—the very same day Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to use nuclear weapons to defend newly annexed regions of Ukraine (Faulconbridge 2023)—four B-52s in Europe took off from the RAF Fairford Station in the United Kingdom and returned to the United States, two of them via northern Sweden. At the same time, their wing at Minot AFB in North Dakota was in the middle of the Prairie Vigilance nuclear exercise. Such close integration of nuclear and conventional bombers into the same task force can have significant implications for crisis stability, misunderstandings, and the risk of nuclear escalation because it could result in overreactions and misperceptions about what is being signaled.

Additionally, since 2019, US bombers have been practicing what is known as an “agile combat employment” strategy by which all bombers “hopscotch” to a larger number of widely dispersed smaller airfields—including airfields in Canada—in the event of a crisis. This strategy is intended to increase the number of aimpoints for a potential adversary seeking to destroy the US bomber force, therefore raising the ante for an adversary to attempt such a strike and increasing the force’s survivability if it does (Arkin and Ambinder 2022a).

Land-based ballistic missiles

The US Air Force (USAF) operates 400 silo-based Minuteman III ICBMs and keeps “warm” another 50 silos to load stored missiles if necessary, for a total of 450 silos. Land-based missile silos are divided into three wings: the 90th Missile Wing at F. E. Warren Air Force Base in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming; the 91st Missile Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota; and the 341st Missile Wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. Each wing has three squadrons, each with 50 Minuteman III silos collectively controlled by five launch control centers. We estimate there are up to 800 warheads assigned to the ICBM force, of which about half are deployed (see Table 1).

The 400 deployed Minuteman IIIs carry one warhead each, either a 300-kiloton W87/Mk21 or a 335-kiloton W78/Mk12A. ICBMs equipped with the W78/Mk12A, however, could technically be uploaded to carry two or three independently targetable warheads each, for a total of 800 warheads available for the ICBM force. The USAF occasionally test-launches Minuteman III missiles with unarmed multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) to maintain and signal the capability to reequip the Minuteman III missiles with additional reentry vehicles, if desired. The most recent such test occurred on September 6, 2023, when a Minuteman III equipped with three test reentry vehicles was launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California and flew approximately 4,200 miles to the US ICBM testing ground at the Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands (US Air Force 2023e).

Although the Minuteman III was initially deployed in 1970, it has been modernized several times, including in 2015, when the missiles completed a multibillion-dollar, decade-long modernization program to extend their service life until 2030. The modernized Minuteman III missiles were referred to by Air Force personnel as “basically new missiles except for the shell” (Pampe 2012).

Part of the ongoing ICBM modernization program involves upgrades to the Mk21 reentry vehicles’ arming, fuzing, and firing system at a total cost of nearly $1 billion (US Department of Defense 2023c, 32). The publicly stated purpose of this refurbishment is to extend the vehicles’ service lives, but the effort appears to also involve adding a “burst height compensation” to enhance the targeting effectiveness of the warheads (Postol 2014). A total of 743 fuze replacements—including all necessary units for the development, qualification, certification, fielding, aging, and replenishment of the fuzes—are planned to be delivered for deployment on the Minuteman IIIs as well as their replacement missile—LGM-35 Sentinel—by the end of FY26 (US Department of Defense 2023a). A cost-projection overrun of the fuze integration program unit cost triggered a breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act in September 2020 but is expected to begin full-rate production in FY 2024 (Reilly 2021; US Department of Defense 2023c). As part of the Mk21A program, Lockheed Martin was awarded a sole source contract in October 2023 amounting to just under $1 billion for the engineering and manufacturing of the new reentry vehicle (US Department of Defense 2023b). These modernization efforts complement a similar fuze upgrade underway to the Navy’s W76–1/Mk4A warhead.

Early acquisition activities for a Next Generation Reentry Vehicle (NGRV) began in FY24. The NGRV will be integrated into the new Sentinel ICBM to bolster its payload suite and will be capable of carrying both current and future warheads (US Air Force 2023f, 589).

The Air Force’s FY24 budget for ICBM Reentry Vehicles Research Development, Test & Evaluation Programs increased significantly from the previous President’s Budget due to changes to the Payload Reentry System requirements, which cost an extra $43.4 million, as well as the need to add another flight test due to a failed flight test in July 2022, which will cost over $48 million. In addition, NGRV funding was accelerated to begin early acquisition activities in FY24, adding $15.5 million to the FY24 budget. The total program cost for ICBM reentry vehicle development in FY24 is just over $475 million and will increase up to $864 million by FY28 (US Air Force 2023f, 589).

While the Air Force insists that “there is no backup plan for Sentinel,” it appears that it would be technically possible to conduct a second life-extension of the Minuteman III missile before it would have to be retired and replaced (Clark 2019; Heckmann 2023). A July 2022 environmental impact assessment revealed that the Air Force did consider such a life extension as well as three other options, including deploying a “[s]mall ICBM […] with lower procurement costs and enhanced accuracy;” working with “a private spacecraft company” to deploy commercial launch vehicles equipped with nuclear-capable reentry vehicles; and converting the existing Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) to be deployed in land-based silos. However, the Air Force ultimately eliminated these options because they did not meet what it called its “selection standards,” which include criteria such as sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure (US Air Force 2022d). Instead, the Air Force opted to purchase a whole new generation of ICBMs known by its programmatic name—the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)—until it was officially named the LGM-35A Sentinel in April 2022 (US Air Force 2022a).

Non-governmental experts, including those conducting Department of Defense-sponsored research, have questioned the Pentagon’s procurement process and lack of transparency regarding its decision to pursue the Sentinel option over other potential deployment and basing options (Dalton et al. 2022, 4). Moreover, it is unclear why an enhancement of ICBM capabilities would be necessary for the United States. For instance, any such enhancements would not mitigate the inherent challenges associated with launch-on-warning, risky territorial overflights, or silo vulnerabilities to environmental catastrophes or conventional counterforce strikes (Korda 2021). Additionally, even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload—not the missile itself. By the time an adversary’s interceptor would be able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would already have shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and be guided solely by its reentry vehicle—which can be independently upgraded as necessary. For this reason, it is not readily apparent why the US Air Force would require its ICBMs to have capabilities beyond the current generation of Minuteman III missiles; the Air Force has yet to publicly explain why.

The development of the Sentinel has also been marked by a series of controversial industry contracts, starting with the awarding of a $13.3 billion sole-source contract to Northrop Grumman in 2020 to complete the engineering and manufacturing development stage (For a more detailed summary of the Sentinel’s procurement timeline, see Korda 2021). There have been warnings about program cost projection overruns for years: It was originally projected to cost between $93.1 billion and $95.8 billion, an increase from a preliminary $85 billion Pentagon estimate in 2016. In July 2023, the US Congressional Budget Office estimated that the cost of acquiring and maintaining the Sentinel would total approximately $118 billion over the 2023–2032 period—approximately $20 billion more than the Congressional Budget Office had previously estimated for the 2019–2028 period, and $36 billion more than the 2021–2030 period (Congressional Budget Office 2019, 2021, 2023). But in early 2024, the Air Force notified Congress of a two-year delay in the schedule and an estimated 37-percent increase from the current cost target to at least $125 billion (Tirpak 2024). These amounts do not include the costs for the new Sentinel warhead—the W87–1—which is projected to cost up to $14.8 billion, or the plutonium pit production that the US Air Force and US Strategic Command say is needed to build the warheads (Government Accountability Office 2020).

The schedule and extreme cost overruns for the Sentinel program incurred a critical breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, which requires the Secretary of Defense to conduct a root-cause analysis and renewed cost assessment before providing a certification to Congress that verifies the necessity and viability of the program no later than 60 days after a Selected Acquisition Report is also submitted to Congress (Knight 2024b). Only if the Secretary of Defense determines that a certification can be issued will the Sentinel program avoid termination. In this case, the Nunn-McCurdy Act then requires the program to be assigned new approval milestones and be restructured to address the causes behind the overrun. It is likely that the Secretary of Defense will justify the need for the Sentinel program. The Air Force asserted that the Sentinel program will continue at all costs and will make any necessary “trades,” which could mean an increased defense budget or a reduction or cancellation of other programs (Decker 2024).

Andrew Hunter, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics clarified that while the cost of the missile itself has increased, challenges with supporting infrastructure is the significant driver of schedule overrun, which also further impacts the overall cost (Tirpak 2024). In addition to an entirely new missile, the Sentinel program includes launch facility replacement and modifications (since the Sentinel may require a larger silo), new missile alert facilities, and new command and control facilities and systems—not to mention new training and curriculum for USAF personnel. Many of these delays are results of staffing shortfalls, clearance delays, IT infrastructure challenges, and trouble with supply chains on the part of Northrop Grumman (Government Accountability Office 2023a, 88).

According to a USAF program report published in 2020, the Air Force must deploy 20 new Sentinel missiles with legacy reentry vehicles and warheads to achieve initial operating capability, scheduled in fiscal year 2029 (Sirota 2020). The plan is to purchase a total of 659 missiles—400 of which would be deployed, while the remainder will be used for test launches and as spares (Capaccio 2020). However, the Air Force announced in early 2024 that the date of the first Sentinel deployment will slide into spring 2030 and may fall even further behind schedule. The Department of Defense has previously indicated that a two-year delay could lower the force structure by at least 30—which raises the question of whether some of the Minuteman III ICBMs will be life-extended anyways or if the US force structure will dip below the congressionally-mandated requirement of 400 deployed ICBMs (Korda and White 2021).

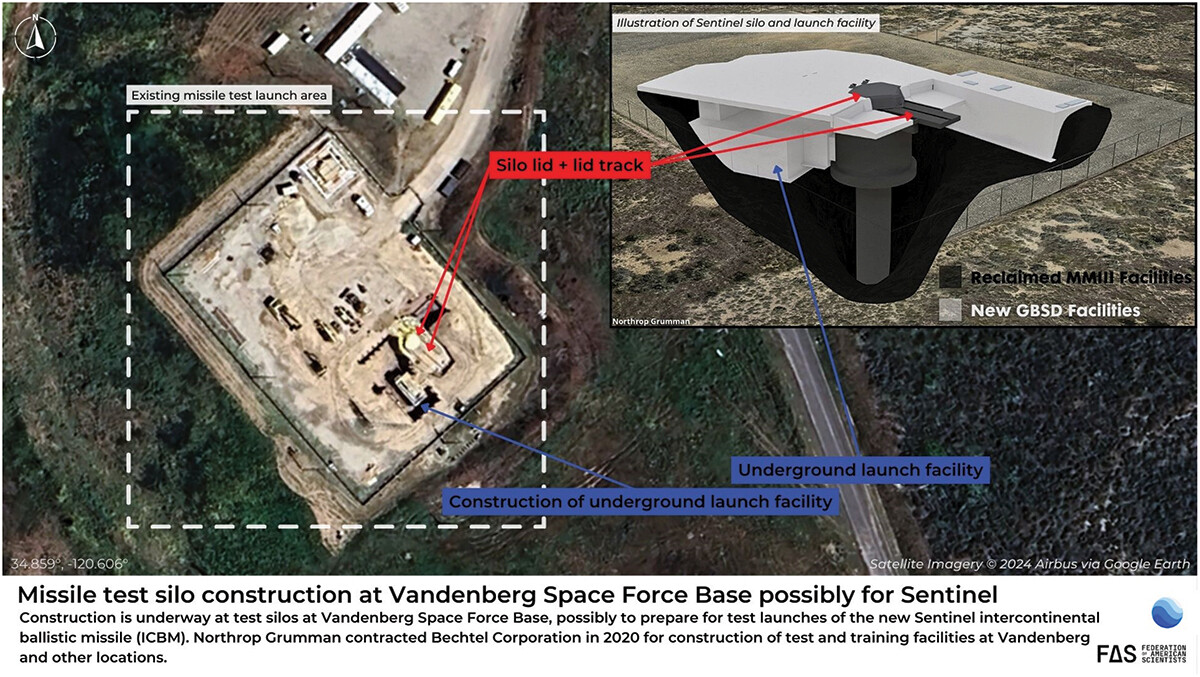

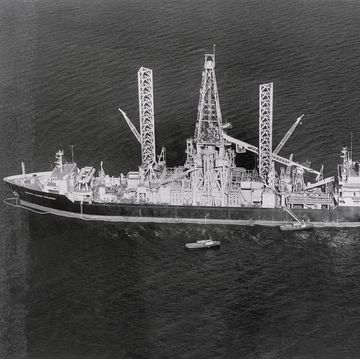

Program officials had originally announced that the first Sentinel prototype would conduct a test flight by the end of 2023, but this schedule has been delayed and is now planned for FY24 (Bartolomei 2021; Government Accountability Office 2023a). The first two in a series of static firing tests were completed in March 2023 and January 2024 to assess the first and second stages of the Sentinel’s three-stage propulsion system (Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center 2023, 2024). Northrop Grumman also conducted a series of “shroud fly-off and missile modal tests” in early 2024 to evaluate the “forward and aft sections” of the Sentinel (Northrop Grumman 2024). Throughout 2023, satellite imagery revealed construction to a test launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base, in a likely effort to upgrade the site to accommodate the Sentinel test flight program (see Figure 1).

According to the US Air Force, the new Sentinel missile will meet existing user requirements but will have the adaptability and flexibility to be upgraded throughout 2075 and will have a greater range than the current Minuteman III (US Air Force 2016). Still, it is unlikely that the Sentinel will have enough range to target countries like China, North Korea, and Iran without over-flying Russia.

The Sentinel missile will be able to carry multiple warheads, possibly up to two per missile. The Air Force initially planned to equip the Sentinel with life-extended versions of the existing W78 (the modified version of which was known as Interoperable Warhead 1) and W87 warheads. However, in 2018, the Air Force and the NNSA canceled the upgrades and instead proposed a Modification Program to replace the W78 and eventually the W87 with a new warhead known as the W87–1/Mk4A. This new warhead will use a W87-like plutonium pit along with “a well-tested IHE [Insensitive High Explosive] primary design” and will be incorporated into the Mk21A, a modified version of the current Mk21 reentry vehicle (US Department of Energy 2018b). The Weapons Development Cost Report for the W87 modernization program lists the total estimated cost to be up to $15.9 million, not including the costs associated with the production of the new plutonium pits (NNSA 2023, 8–31).

As required by the FY18 National Defense Authorization Act, the NNSA has set an ambitious course of action for producing at least 80 plutonium pits per year by 2030 to meet the Sentinel’s planned deployment schedule. However, due to the agency’s consistent inability to meet project deadlines and its lack of a latent large-scale plutonium production capability, the NNSA notified Congress in 2021 of what independent analysts have long predicted—that the agency will not be able to meet the 80-pit requirement (Demarest 2021; Government Accountability Office 2020; Institute for Defense Analyses 2019). To come as close to the annual pit production requirement as possible, the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility has been tasked with producing 50 of the plutonium pits while the other 30 will be produced at Los Alamos National Laboratory. A repurposed, never-completed, Mixed Fuel Oxide Fuel Fabrication facility at the Savannah River Site was originally scheduled to come online in 2030 to support the goal of 50 pits per year, but the date of completion was extended to between 2032 and 2035 (NNSA 2021a).

Despite completing its Weapon Design Cost Report and entering Phase 6.3 for development engineering in FY23, the W87–1 program will continue to face significant delays and will not enter production until the early 2030s (NNSA 2023, ix, 2–8). Therefore, the Sentinel will be initially fielded with a modified version of the existing W87 known as the W87–0 (NNSA 2023, 1–6).

The Air Force is faced with a tight construction schedule for the deployment of the Sentinel. Each launch facility is expected to take 10 months to upgrade, while each missile alert facility will take approximately 16 months (US Air Force 2023c). The Air Force intends to upgrade all 150 launch facilities and eight out of 15 missile alert facilities for each of the three ICBM bases; the remaining seven missile alert facilities at each base will be dismantled (US Air Force 2023c).

Since each missile alert facility is currently responsible for a group of 10 launch facilities, this could indicate that each missile alert facility may eventually be responsible for up to 18 or 19 launch facilities once the Sentinel becomes operational, which would have implications for the future vulnerability of the Sentinel’s command-and-control system (Korda 2020). Once these upgrades begin, potentially in early 2024, the Air Force must complete one launch facility per week for nine years to complete the new missile’s deployment by 2036 (Mehta 2020).

But since it will take more than one week to complete each facility, several will be out of operation at any given time, which means the Air Force will not be able to maintain 400 operational ICBMs during the construction program. As a result, the 2023 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission recommended the Air Force deploy more than one warhead on some of the ICBMs to maintain the current warhead level (US Strategic Posture Commission 2023). It is expected that construction and deployment will take place first at F. E. Warren Air Force Base between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036. While initial construction activities for the Sentinel were approved in May 2023, the schedule may shift as more information becomes available regarding the results from the Sentinel program’s breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act (Miller and Perez 2023).

As the Sentinel missile gets deployed, the Minuteman III missiles will be removed from their silos and temporarily stored at their respective host bases before being transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range, or Camp Navajo in Arizona. The rocket motors will eventually be destroyed at the Utah Test and Training Range, while non-motor components will be decommissioned at Hill Air Force Base. To that end, five and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill Air Force Base and Utah Test and Training Range, respectively (US Air Force 2020b).

The three ICBM bases will also receive new training, storage, and maintenance facilities as well as upgrades to their Weapons Storage Areas. The first base to receive this upgrade is F. E. Warren, where a groundbreaking ceremony for the new underground Weapons Storage and Maintenance Facility (also called the Weapons Generation Facility) was held in May 2019. Substantial construction began in spring 2020 and was scheduled to be completed in September 2022 (Kristensen 2020a; US Air Force 2019d). Commercial satellite imagery indicates that construction has made substantial progress as of February 2024, although completion could not be confirmed. Construction on new tactics-training facilities have also begun at both F. E. Warren and Malmstrom Air Force Bases. The National Defense Authorization Act for FY24 authorized $10.3 million for construction and land acquisition at Malmstrom that will go toward a new fire station bay and storage area (Tester 2023).

The Air Force conducts several Minuteman III flight tests each year. These are long-planned tests, and the Air Force consistently states that they are not scheduled in response to any external events. After postponements of several tests in 2022 due to global tensions, in 2023 the Minuteman III was launched three separate times from Vandenberg Air Force Base to the Reagan Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll in the Western Pacific traveling approximately 4,200 miles with between one to three test reentry vehicles (Air Force Global Strike Command Public Affairs 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). However, a fourth test that took place in November 2023 was “safely terminated” during its flight due to an “anomaly” that occurred during launch (Air Force Global Strike Command Public Affairs 2023d).

Nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines

The US Navy operates a fleet of 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), of which eight operate in the Pacific from their base near Bangor, Washington, and six operate in the Atlantic from their base at Kings Bay, Georgia. In the past, two of the 14 submarines would be in reactor refueling overhaul (a lengthy refitting process typically carried out about midway through their operating lifespan) at any given time. As the last refueling was completed in February 2023, all 14 boats could now potentially be deployed until 2027 when the first Ohio-class submarine is expected to retire (PSNS & IMF Public Affairs 2023; US Navy 2019). But because operational submarines undergo minor repairs at times, the actual number at sea at any given time is usually closer to eight or 10. Four or five of those are thought to be on “hard alert” in their designated patrol areas, while another four or five boats could be brought to full alert status in hours or days.

Each submarine can carry up to 20 Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), a number reduced from 24 to meet the limits of New START. The 14 SSBNs could potentially carry up to 280 such missiles but the United States has stated that it will not deploy more than 240. Since 2017, the Navy has been replacing the original Trident II D5 with a life-extended and upgraded version known as Trident II D5LE (LE stands for “life-extended”). The upgrade is expected to be completed in 2024. The D5LE, which has a range of more than 12,000 km, is equipped with the new Mk6 guidance system designed to “provide flexibility to support new missions” and make the missile “more accurate,” according to the Navy and Draper Laboratory (Draper Laboratory 2006; Naval Surface Warfare Center 2008). According to FY24 budget documents, the D5LE has also added a hard-target kill capability and increased its payload “to the level permitted by the size of the TRIDENT submarine launch tube, thereby allowing mission capability to be achieved with fewer submarines” (US Department of Defense 2023d). This is to compensate for the fact that the United States will deploy fewer Columbia-class submarines than Ohio-class submarines and each submarine will only carry 16 missiles. (See later paragraphs in this section for more details).

The D5LE upgrade will continue until all boats have been upgraded and will also replace existing Trident SLBMs on British ballistic missile submarines. The D5LE will also arm the new US Columbia-class and British Dreadnought-class ballistic missile submarines when they enter service.

Instead of building a new ballistic missile like the Air Force wants to do with the Sentinel ICBM, the Navy plans to do a second life-extension of the Trident II D5LE to ensure it can operate through 2084 (Eckstein 2019). In 2021, the Director of the Navy’s Strategic Systems Program testified to Congress that the D5LE2, as the second life-extended missile is known, is scheduled to enter service on the ninth Columbia-class SSBN beginning in FY 2039, following which it will be back-fitted to the remaining eight boats (Wolfe 2021b). The Navy also announced in 2021 that it would acquire an additional 108 Trident missiles to be used for deployment and testing (Wolfe 2021a).

Each Trident SLBM can carry up to eight nuclear warheads, but they normally carry an average of four or five warheads, for an average load-out of approximately 90 warheads per submarine. The payloads of the different missiles on a submarine are thought to vary significantly to provide maximum targeting flexibility, but all deployed submarines are thought to carry the same combination. Normally, around 950 warheads are deployed on the operational SSBNs, although the number can be lower due to maintenance of individual submarines. Overall, SSBN-based warheads account for approximately 70 percent of all warheads attributed to the United States’ deployed strategic launchers under New START.

Three warhead types are deployed on US SLBMs: the 90-kiloton enhanced W76–1, the 8-kiloton W76–2, and the 455-kiloton W88. The W76–1 is a refurbished version of the W76–0, which is being retired, apparently with slightly lower yield but with enhanced safety features added. The NNSA completed the massive decade-long production of an estimated 1,600 W76–1 warheads in January 2019 (US Department of Energy 2019). The Mk4A reentry body that carries the W76–1 is equipped with a new arming, fuzing, and firing unit with better targeting effectiveness than the old Mk4/W76 system (Kristensen, McKinzie, and Postol 2017). We estimate there may be up to 1,920 warheads assigned to the SSBN fleet (although the number might be a little lower), of which roughly 950 are deployed (see Table 1).

The higher-yield W88 warhead is currently undergoing a life-extension program that modernizes the arming, fuzing, and firing components, addresses nuclear safety concerns by replacing the conventional high explosives with insensitive high explosives, and will ultimately support future life-extension options (US Department of Energy 2022, 2–12). The first production unit for the W88 Alt 370 was completed on July 1, 2021, half had been delivered by 2023, and production is expected to be completed in FY26 (NNSA 2021b; US Department of Energy 2024).

The W76–2 only uses the warhead fission primary to produce a yield of about 8 kilotons. We estimate that no more than 25 were ultimately produced, and that one or two of the 20 missiles on each SSBN is armed with one or two W76–2 warheads each, while the remainder of the SLBMs will be filled with either the 90-kiloton W76–1 or the 455-kiloton W88 (Arkin and Kristensen 2020). The Biden NPR agreed “that the W76–2 [warhead] currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use”; however, the review left the door open for the weapon to be removed in the future, noting: “Its deterrence value will be re-evaluated as the F-35A [aircraft] and LRSO [air-launched cruise missile] are fielded, and in light of the security environment and plausible deterrence scenarios we could face in the future” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20). This passage suggests that the W76–2 warhead could potentially be removed from service closer to the turn of the decade.

The United States is also planning to build a new SLBM warhead—the W93—which will be housed in the Navy’s proposed Mk7 aeroshell (reentry body). According to the Department of Energy, “all of its key nuclear components will be based on currently deployed and previously tested nuclear designs, as well as extensive stockpile component and materials experience. It will not require additional nuclear explosive testing to be certified” (US Department of Energy 2022, 1–7). The W93 is intended to initially supplement, rather than replace, the W76–1 and W88. Another new warhead is subsequently planned to eventually replace those warheads in the future. The completion of the W93ʹs first production unit is tentatively scheduled for 2034–2036 (US Department of Energy 2022, 2–10). In November 2023, the NNSA projected the W93 program to cost $22.9 billion, which is $8.9 billion more than the NNSA’s cost estimate published in March 2022 (US Department of Energy 2022, 205; 2023b, 201)—a nearly 40-percent difference of two cost projections only a year-and-a-half apart.

The US sea-based nuclear weapons program also supports the United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent. The missiles carried on the Royal Navy ballistic missile submarines are from the same pool of missiles carried on US SSBNs. The warhead uses the Mk4A reentry body and is thought be a slightly modified version of the W76–1 (Kristensen 2011a); the UK government calls it the “Trident Holbrook” (UK Ministry of Defence 2015). The Royal Navy also plans to use the new Mk7 for the replacement warhead it plans to deploy on its new Dreadnought submarines in the future. A 2021 update to Parliament reaffirmed that “[t]he UK warhead will be integrated with the US supplied Mark 7 aeroshell to ensure it remains compatible with the Trident II D5 missile and delivered in parallel with the US W93/Mk7 warhead programme” (Government of the United Kingdom 2021). In 2023, the US Navy Director for Strategic Systems Programs clarified that, “the development of the Mk7 reentry system to support the US W93 warhead program is also critical to the development of a next generation nuclear warhead and reentry system for the UK. The two nations are working separate but parallel warhead programs with collaboration between the two” (Wolfe 2023).

In the past 25 years, deterrence patrol operations have changed significantly, with the annual number having declined by more than half, from 64 patrols in 1999 to between 30 and 36 annual patrols in recent years. Most submarines now conduct what are called “modified alerts,” which mix deterrent patrol with exercises and occasional port visits (Kristensen 2018). While most ballistic missile submarine patrols last 77 days on average, they can be shorter or, occasionally, last significantly longer. In October 2021, for example, the USS Alabama (SSBN-731) completed a 132-day patrol, and in June 2014, the USS Pennsylvania (SSBN-735) returned to its Kitsap Naval Submarine Base in Washington after a 140-day deterrent patrol—the longest patrol ever by an Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine (US Strategic Command 2021b). In the Cold War years, nearly all deterrent patrols took place in the Atlantic Ocean. In contrast, more than 60 percent of deterrent patrols today normally take place in the Pacific, reflecting increased nuclear war planning against China and North Korea (Kristensen 2018).

Ballistic missile submarines normally do not visit foreign ports during patrols, but there are exceptions. The United States conducted routine visits to South Korea in the late 1970s and early 1980s as well as occasional visits to Europe, the Caribbean, and Pacific ports during the 1980s and 1990s (Kristensen 2011b). After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, the US Navy started to conduct one or two foreign port visits per year to send political messages and to make ballistic missile submarines more visible. Port visits by US submarines have continued every year since, except in 2020, to locations including Scotland, Alaska, Guam, and Gibraltar. In October 2022, US Central Command released photos indicating that the USS West Virginia (SSBN-736) was operating at an undisclosed location in international waters in the Arabian Sea—a highly rare public disclosure of a ballistic missile submarine’s operating area and the first Ohio-class SSBN deployment in the Indian Ocean (US Central Command 2022). Notably, in July 2023, the USS Kentucky (SSBN-737) made a port visit to Busan, South Korea following the signing of the Washington Declaration by South Korean President Yoon and President Biden to affirm extended deterrence commitments (Mongilio 2023). This was the first time that nuclear weapons have been in South Korea since the US weapons were removed from their deployment in 1991.

Design of the next generation of ballistic missile submarines, known as the Columbia-class, is well underway. This new class is scheduled to begin replacing the current Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines in the late 2020s. The Columbia-class will be 2,000 tons heavier than the Ohio-class but will be equipped with 16 missile tubes rather than its predecessor’s 20. The Columbia-class submarine program, which is expected to account for approximately one-fifth of the budget of Navy’s entire shipbuilding program from the mid-2020s to the mid-2030s, is projected to cost a little over $112 billion—an increase of $3.4 billion from the Government Accountability Office’s 2021 assessment (Government Accountability Office 2022, 179–180).

The lead boat in a new class is generally budgeted at a significantly higher amount than the rest of the boats, as the Navy has a longstanding practice to incorporate the entire fleet’s design detail and non-recurring engineering costs into the cost of the lead boat. As a result, the Navy’s fiscal 2024 budget submission estimated the procurement cost of the first Columbia-class SSBN—the USS District of Columbia (SSBN-826)—at approximately $15.2 billion, followed by $9.3 billion for the second boat (Congressional Research Service 2024, 9). A $5.1 billion development contract was awarded to General Dynamics Electric Boat in September 2017, and construction of the first boat began on October 1, 2020—the first day of FY 2021. The keel for the lead boat was laid down in June 2022, and procurement of the second boat is expected for FY24 (US Navy 2022).

Certain elements of construction were originally delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but after several years of full-scale construction, the Navy continues to face delays due to challenges with design, materials, and quality of work on the lead submarine (Eckstein 2020; Government Accountability Office 2023b). According to a June 2023 report by the Government Accountability Office, “the program remains behind on producing design products—in particular, work instructions that detail how to build the submarine—because of ongoing challenges using a software-based design tool. These, in turn, contributed to delays in construction of the lead submarine” (Government Accountability Office 2023a, 160). The Navy is working to mitigate additional delays, but these constraints mean that the program is at significant risk of cost overgrowth and is very likely to suffer further setbacks.

The Columbia-class submarines are expected to be significantly quieter than the current Ohio-class fleet. This is because a new electric-drive propulsion train will turn each boat’s propeller with an electric motor instead of louder, mechanical gears. Additionally, the components of an electric-drive propulsion train can be distributed around the boat, increasing the system’s resilience, and lowering the chances that a single weapon could disable the entire drive system (Congressional Research Service 2000, 20). The Navy has never built a nuclear-powered submarine with electric-drive propulsion before, which could create technical delays for a program that is already on a very tight production schedule (Congressional Research Service 2022, 12).

The Navy’s schedule indicates that the Ohio-class boats will begin going offline in fiscal year 2027, around the same time that the first Columbia-class boat is scheduled to be delivered in October 2027. Sea trials are expected to last approximately three years, and the first Columbia deterrence patrol is scheduled for 2031 (Congressional Research Service 2022, 8). Because the Ohio retirement and Columbia production are not completely aligned, the Navy projects that the total number of operational SSBNs will go from 14 boats to 13 in 2027, 12 in 2029, 11 in 2030, and 10 in 2037, before eventually climbing back to 11 in 2041 and the full complement of 12 Columbia-class boats in 2042 (Rucker 2019; US Navy 2019). As noted previously, the lead boat of the new Columbia-class submarine fleet will be designated the USS District of Columbia (SSBN-826)—and the second boat will be designated the USS Wisconsin (SSBN-827). The rest of the Columbia-class submarine fleet has not yet been named.

The last Ohio-class to complete a mid-life multi-year refueling overhaul—the USS Louisiana (SSBN-743)—returned to full operational status in September 2023 when it carried out a Demonstration and Shakedown Operation (DASO) to test the boat’s readiness; the launch marked the 191 st successful test launch of the Trident II system (US Navy 2023).

The Columbia-class SSBNs will not require nuclear refueling; as a result, their midlife maintenance operations will take significantly less time than their Ohio- class predecessors (Congressional Research Service 2022, 5).

Strategic bombers

The US Air Force currently operates a fleet of 20 B-2A bombers (all of which are nuclear-capable) and 76 B-52 H bombers (46 of which are nuclear-capable). A third strategic bomber, the B-1B, is not nuclear-capable. Of these bombers, we estimate that approximately 60 (18 B-2As and 42 B-52Hs) are assigned nuclear missions under US nuclear war plans, although the number of fully operational bombers at any given time is lower. The New START data from September 2022, for example, only counted 43 deployed nuclear bombers (10 B-2As and 33 B-52Hs) (US State Department 2023a). The bombers are organized into nine bomb squadrons in five bomb wings at three bases: Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota, Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, and Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri. The new B-21 bomber program will result in an increase in the number of nuclear bomber bases to five (Kristensen 2017c).

Each B-2 can carry up to 16 nuclear bombs (the B61–7, B61–11, B61–12, and B83–1 gravity bombs), and each B-52 H can carry up to 20 air-launched cruise missiles (the AGM-86B). B-52 H bombers are no longer assigned gravity bombs (Kristensen 2017a). An estimated 788 nuclear weapons, including approximately 500 air-launched cruise missiles, are assigned to the bombers, but only about 300 weapons are thought to be deployed at bomber bases (see Table 1). The estimated remaining 488 bomber weapons are thought to be in central storage at the large Kirtland Underground Munitions Maintenance and Storage Complex outside Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The United States is modernizing its nuclear bomber force by upgrading nuclear command-and-control capabilities on existing bombers, developing enhanced nuclear weapons (the B61–12, B61–13, and the new AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff Weapon or LRSO), and designing a new heavy bomber (the B-21 Raider).

Upgrades to the nuclear command-and-control systems that the bombers use to plan and conduct nuclear strikes include the Global Aircrew Strategic Network Terminal (ASNT). This is a new, high-altitude, electromagnetic pulse-hardened network of fixed and mobile nuclear command-and-control terminals. This network provides wing command posts, task forces, munitions support squadrons, and mobile support teams with survivable ground-based communications to receive launch orders and disseminate them to bomber, tanker, and reconnaissance air crews. First delivery of the Global ASNT, which the Air Force describes as “the largest upgrade to its nuclear command, control and communication systems in more than 30 years,” occurred in January 2022 when Barksdale Air Force Base received the system (US Air Force 2022c). Raytheon, the US defense corporation which was awarded a $134.4 million contract to develop the system, achieved initial operational capability for the system in August 2022 (Airforce Technology 2022).

Another command-and-control upgrade involves a program known as Family of Advanced Beyond Line-of-Sight Terminals (FAB-T), which will replace existing Milstar terminals to connect strategic bombers and reconnaissance aircraft with military satellite constellations operated by the US Space Force. These new, extremely high frequency, nuclear-hardened terminals are designed to communicate with several satellite constellations, including Milstar, advanced extremely high frequency (AEHF), and enhanced polar system (EPS) constellations. The 37 ground stations and nearly 50 airborne terminals of the FAB-T will provide protected high-data rate communication for nuclear and conventional forces, including for what is officially called “presidential national voice conferencing” (US Air Force 2019c). In a February 2023 annual report to Congress on its acquisition programs, the Air Force listed the FAB-T as one of its five lowest-performing programs, reporting that the program has already faced over a decade of schedule delays and other platform issues (US Air Force 2023b). In a June 2023 report accompanying a Defense spending bill, the House Appropriations Committee said it “remains very concerned” about these lowest performing programs and directed the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration to submit to both House and Senate appropriations committees detailed, quarterly updates on “the status of corrective actions” for the programs, including the FAB-T (US House of Representatives 2023). The Air Force announced on June 28, 2023, that it awarded Raytheon Technologies a sole-source, $625 million contract to produce FAB-T (Erwin 2023).

The heavy bombers are also being upgraded with improved nuclear weapons. This effort includes development of the first guided, standoff nuclear gravity bomb, known as the B61–12, which was ultimately intended to replace all existing gravity bombs. The bomb uses a modified version of the warhead used in the current B61–4 gravity bomb. The B61–12 became operational with the B-2 bombers in 2023 (National Nuclear Security Administration 2023). The bomb will later become operational with several fighter-bomber jets (see below).

After several years delay, the First Production Unit prototype of the B61–12 was completed by NNSA on August 25, 2020, at its Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas (NNSA 2020). The actual First Production Unit was completed in November 2021, and NNSA confirmed in October 2022 that full-scale production had begun (NNSA 2022). By 2023, half of the planned B61-12s had been produced (US Department of Energy 2024).

The United States was initially expected to produce approximately 480 B61–12 bombs, but in 2023 it announced that a small number of them instead will be produced as the B61–13, a gravity bomb with a much larger yield (US Department of Defense 2023e) (See below paragraph for more details). The B61–13 will use the warhead from B61-7s but use the B61–12 safety and control features and guided tail kit for improved accuracy. As such, the B61–13 will have the same maximum yield of 360 kilotons, significantly higher than the B61–12’s yield of 50 kilotons. The B61–13 will be designed for the future B-21 bomber and possibly the B-2 until its retirement. The military justification for the new B61–13 gravity bomb is difficult to identify through open sources, although it appears that the bomb will have a mission related to broad area targeting and perhaps holding some underground targets at risk. The bomb’s development may also be related to the ongoing effort to retire the B83–1 (Kristensen and Korda 2023).

The Air Force is also developing a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile known as the AGM-181 LRSO. It will replace the AGM-86B air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) in 2030 and will carry the W80–4 nuclear warhead, a modified version of the W80–1 used in the current ALCM. The NNSA authorized the production engineering phase (Phase 6.4) for the W80–4 in March 2023, and the First Production Unit is scheduled for delivery in September 2027 (US Department of Energy 2023c). Production of the warhead is scheduled to be completed in FY 2031 (Leone 2022).

The LRSO will arm both the 46 nuclear-capable B-52Hs and the new B-21, the first time a US stealth bomber will carry a nuclear cruise missile. A $250 million contract was awarded to Boeing in March 2019 for the Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction phase and Engineering and Manufacturing Development (phase to integrate the future LRSO onto the B-52Hs, a process that is expected to be completed by the beginning of 2025 (Hughes 2019). On January 8, 2024, the Air Force posted a solicitation for sources to develop Carriage Equipment for integration of the LRSO onto the B-52Hs (US Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center 2024). Development and production were initially projected to reach at least $4.6 billion for the missile (US Air Force 2019b) with another $10 billion for the warhead (US Department of Energy 2018a); however, that estimate has since risen to a total acquisition cost of approximately $16 billion (Congressional Budget Office 2023).

The LRSO missile itself is expected to be entirely new, with significantly improved military capabilities compared with the ALCM, including longer range, greater accuracy, and enhanced stealth (Young 2016). Supporters of the LRSO argue that a nuclear cruise missile is needed to enable bombers to strike targets from well outside the range of current and future air-defense systems of potential adversaries. Proponents also argue that these missiles are needed to provide US leaders with flexible strike options in limited regional scenarios. However, critics argue that conventional cruise missiles, such as the extended-range version of the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile, can currently provide standoff strike capability, and that other nuclear weapons would be sufficient to hold the targets at risk. In fact, the conventional Extended-Range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile is now an integral part of US Strategic Command’s strategic war plan. (Standoff weapons engage targets from a distance where attacking personnel are standing off outside the range of defensive weapons).

After clearing the Air Force’s preliminary design review received in early 2017, the Air Force announced in early-2022 that six B-21 bombers were in production, and the first assembled bomber was taken to conduct its calibration tests in early March 2022 (Tirpak 2022a). The first test flight took place in November 2023 (Copp 2023) and a second test flight occurred on January 17, 2024 (Harpley 2024). Following its first flight, the Pentagon approved the program to enter the low-rate initial production phase. The B-21 is expected to enter service by 2027 to gradually replace the B-1B and B-2 bombers during the 2030s (Marrow 2024b).

It is expected that the Air Force will procure at least 100 (possibly as many as 145) of the B-21, with the latest service costs estimated at approximately $203 billion for the entire 30-year operational program, at an estimated cost of $550 million per plane (Capaccio 2021; Tirpak 2020). The budget and many design details of the B-21 are still secret. The official unveiling ceremony at Northrop Grumman’s production facilities in December 2022 showed a design very similar to the B-2 but slightly smaller with a reduced weapons capability (US Air Force 2022b).

The B-21 will be capable of delivering the B61–12 and B61–13 guided nuclear gravity bombs and the future AGM-181 LRSO, as well as a wide range of non-nuclear weapons, including the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff (JASSM) cruise missile.

The Air Force announced in March 2019 that the B-21 bombers will first be deployed at Ellsworth Air Force Base (South Dakota), followed by Whiteman Air Force Base (Missouri) and Dyess Air Force Base (Texas) “as they become available” (US Air Force 2019a). Construction at Ellsworth AFB began in 2022, and the base’s new Weapons Generation Facility, which will store and maintain nuclear bombs and cruise missiles, is scheduled to be completed by February 2026 (Tirpak 2022b). Ellsworth AFB is currently expected to host two B-21 squadrons (one operational squadron and one training squadron). However, according to South Dakota Sen. Mike Rounds, a second operational squadron might eventually be stationed at Ellsworth Air Force Base as well in the future (News Center 1 2022).

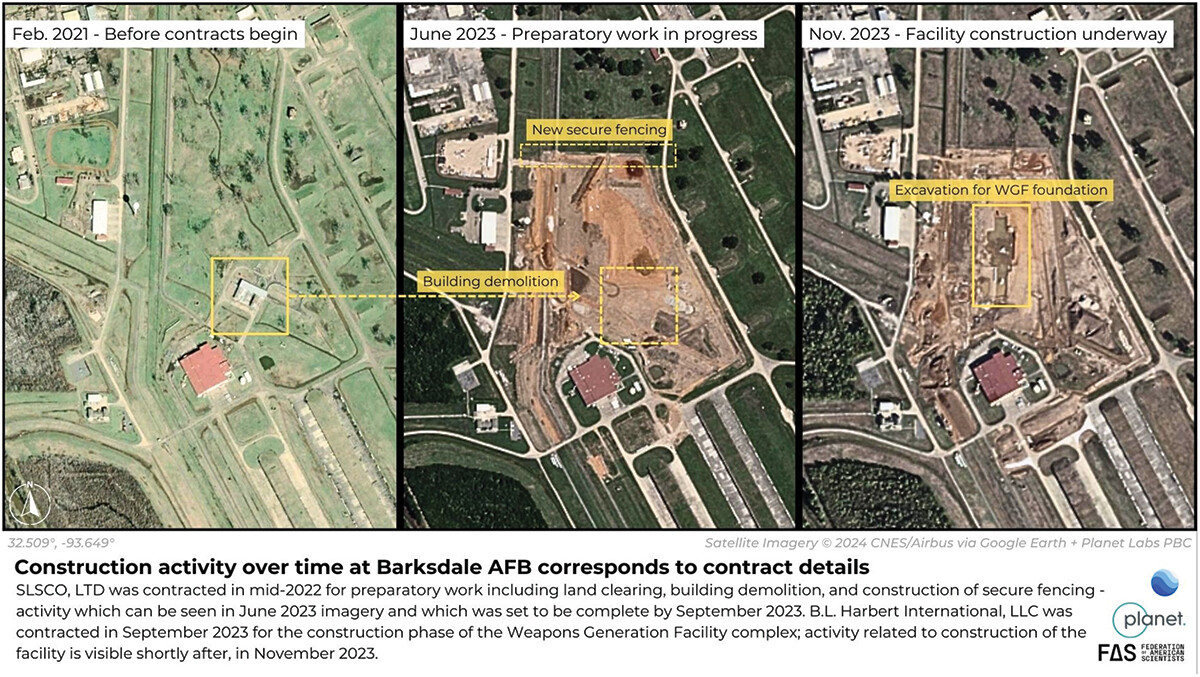

The conversion of the non-nuclear B-1 host bases to receive the nuclear B-21 bomber will increase the overall number of bomber bases with nuclear weapons storage facilities from two bases today (Minot AFB and Whiteman AFB) to five bases by the 2030s (Kristensen 2020b). A new Weapons Generation Facility is also under construction at Barksdale AFB, which will reinstate nuclear storage capability once complete (Knight 2024a) (see Figure 2).

Nonstrategic nuclear weapons

The United States has only one type of nonstrategic nuclear weapon in its stockpile: the B61 gravity bomb. But it exists in several versions: the B61–3 and the B61–4 with yields varying from 0.3 kilotons up to 170 and 50 kilotons, respectively, and the new B61–12 entering the stockpile with a yield of up to 50 kilotons. All other previous versions have been retired. Approximately 200 such tactical B61 bombs are currently stockpiled (see Table 1). About 100 of these (versions −3 and − 4) are thought to be deployed at six bases in five European countries: Aviano and Ghedi in Italy; Büchel in Germany; Incirlik in Turkey; Kleine Brogel in Belgium; and Volkel in the Netherlands. This number has declined since 2009 partly due to reduction of operational storage capacity at Aviano and Incirlik (Kristensen 2015, 2019c). A seventh country—Greece—has a contingency nuclear strike mission and accompanying reserve squadron, but it does not host any nuclear weapons (Kristensen 2022b).

The other 100 B61 bombs are stored in the United States for backup and potential use by US fighter-bombers in support of allies outside Europe, including Northeast Asia. The fighter-bombers include F-15Es from the 391st Fighter Squadron of the 366th Fighter Wing at Mountain Home in Idaho (Carkhuff 2021).

Over the next few years, the new B61–12 will replace all legacy B61 bombs currently deployed in Europe and will be integrated onto US- and allied-operational tactical aircraft (Kristensen 2023b).

The Belgian, Dutch, German, and Italian air forces are currently assigned an active nuclear strike role with US nuclear weapons. Under normal circumstances, the nuclear weapons are kept under the control of US Air Force personnel; their use in war must be authorized by the US president. A 2022 NATO factsheet states that “a nuclear mission can only be undertaken after explicit political approval is given by NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group authorization is received from the US President and UK prime minister” (NATO 2022). However, it is unclear why the UK Prime Minister would have to authorize employment of US nuclear weapons, and unless NATO territory had been attacked with nuclear weapons first, it seems unlikely that the entire Nuclear Planning Group would be able to agree on approving the employment of non-strategic nuclear weapons from bases in Europe.

The Belgian and Dutch air forces currently use the F-16 aircraft for the nuclear missions, although both countries are in the process of obtaining the F-35A Lightning II to eventually replace their F-16s. Lockheed Martin presented the first F-35A for Belgium during a rollout ceremony in December 2023, during which Belgium’s Chief of Defense remarked that “the introduction of the F-35 … will enable us to continue to fulfil all our missions in the coming decades, in cooperation with our allies and partners in NATO, the EU and beyond” (Lockheed Martin 2023). The Italian Air Force uses the PA-200 Tornado for the nuclear mission but is also in the process of acquiring the F-35A. Like the Tornados, the nuclear F-35As will be based at Ghedi Air Base, which is currently being upgraded. Italy’s 6° Stormo (Wing) at Ghedi Air Base received its first F-35A in June 2022 (Cenciotti 2022). Germany also uses the PA-200 Tornado for the nuclear mission; however, it plans to retire its Tornados by 2030 and to replace them with 35 F-35A aircraft to continue the nuclear mission (US Department of Defense 2022b).