- Introduction

- The Old Poor Law

- The New Poor Law

- 1601 Poor Law Act

- 1662 Settlement Act

- 1723 Knatchbull's Act

- 1782 Gilbert's Act

- 1834 Poor Law Act

- 1838 Irish Act

- 1845 Scottish Act

- Poor Law Unions

- London Corporation

- Quaker Workhouse, Clerkenwell

- Quaker Workhouse, Bristol

- Parish workhouses

- London parishes

- Civic Incorporations

- Rural Incorporations

- Gilbert Unions

- Summary List

- Biggleswade

- Leighton Buzzard

- Easthampstead

- Hungerford (& Ramsbury)

- Reading & Wokingham SD

- Wallingford

- Newport Pagnell

- Caxton & Arrington

- North Witchford

- Great Boughton

- Macclesfield

- St Columb Major

- Alston with Garrigill

- Cockermouth

- Chapel-en-le-Frith

- Chesterfield

- East Stonehouse

- Kingsbridge

- Newton Abbot

- Plympton St Mary

- South Molton

- Stoke Damerel

- Shaftesbury

- Sturminster

- Wareham & Purbeck

- Wimborne & Cranborne

- (Bishop) Auckland

- Chester-le-Street

- Houghton-le-Spring

- South Shields

- Stockton-on-Tees

- Lexden & Winstree

- Saffron Walden

- Barton Regis

- Bristol Incorporation

- Chipping Sodbury

- Cirencester

- Stow-on-the-Wold

- Westbury-on-Severn

- Wheatenhurst

- Aldershot GP

- Alverstoke GP

- Basingstoke

- Bournemouth

- Catherington

- Christchurch

- Farnborough GU

- Farnham & Hartley Wintney SD

- Fordingbridge

- Hartley Wintney

- Isle of Wight

- Petersfield

- Portsea Island

- South Stoneham

- Southampton

- Stockbridge

- New Winchester

- Berkhampstead

- Bishop's Stortford

- Buntingford

- Hemel Hempstead

- Isle of Man

- East Ashford

- Gravesend & Milton

- Hollingbourne

- Isle of Thanet

- Milton Regis

- North Aylesford

- Romney Marsh

- West Ashford

- Ashton-under-Lyne

- Barrow-in-Furness

- Barton-upon-Irwell

- Toxteth Park

- Ashby-de-la-Zouch

- Barrow-upon-Soar

- Loughborough

- Lutterworth

- Market Bosworth

- Market Harborough

- Melton Mowbray

- Gainsborough

- Glanford Brigg

- Bethnal Green (St Matthew)

- Bloomsbury (St Giles & St George)

- Chelsea (St Luke)

- City of London

- City of Westminster

- Clerkenwell (St James & St John)

- East London

- Hammersmith

- Hampstead (St John)

- Islington (St Mary)

- Mile End Old Town

- St George's

- St George in the East

- St George Hanover Square

- St Martin-in-the-Fields

- St Marylebone

- St Sepulchre

- Shoreditch (St Leonard's)

- West London

- Westminster (St James)

- Westminster (St Margaret & St John)

- Westminster Union

- Whitechapel

- Bermondsey (St Mary Magdalen)

- Camberwell (St Giles)

- Lambeth (St Mary)

- Newington (St Mary)

- Rotherhithe (St Mary)

- Southwark (St George the Martyr)

- St Saviour's

- Wandsworth & Clapham

- Brentwood SD

- Central London SD

- Finsbury SD

- Forest Gate SD

- Kensington & Chelsea SD

- North Surrey SD

- South Metropolitan SD

- West London SD

- Central London SAD

- Finsbury SAD

- Kensington SAD

- Newington SAD

- Poplar & Stepney SAD

- Rotherhithe SAD

- Aldborough GU

- Bawdeswell GU

- Brinton and Melton Constable GU

- East & West Flegg

- Freebridge Lynn

- Gimingham GU

- (Great) Yarmouth

- Hackford GU

- King's Lynn

- Loddon & Clavering

- Mitford & Launditch

- Tunstead & Happing (Smallburgh)

- Hardingstone

- Northampton

- Peterborough

- Potterspury

- Wellingborough

- Berwick-upon-Tweed

- Castle Ward

- Haltwhistle

- Newcastle-upon-Tyne

- Northern Counties JC

- East Retford

- Thurgarton Incorporation

- Chipping Norton

- Atcham (& Shrewsbury)

- Church Stretton

- Cleobury Mortimer

- (Market) Drayton

- South-East Shropshire SD

- Long Ashton

- Shepton Mallet

- Alstonfield GU

- Burton Upon Trent

- Newcastle-under-Lyme

- Stoke-upon-Trent

- Walsall & West Bromwich JC

- Walsall & West Bromwich SD

- West Bromwich

- Wolstanton & Burslem

- Wolverhampton

- Bosmere & Claydon

- Bury St Edmunds

- Colneis & Carlford

- Loes and Wilford

- Mutford & Lothingland

- East Grinstead

- East Preston

- Westhampnett

- Bedworth GU

- Shipston-on-Stour

- Stratford-on-Avon

- Alderbury (Salisbury)

- Bradford on Avon

- Cricklade & Wootton Bassett

- Highworth & Swindon

- Marlborough

- Westbury & Whorwellsdown

- Kidderminster

- King's Norton

- Stourbridge

- Upton-upon-Severn

- Bridlington

- Kingston upon Hull

- Pocklington

- Bainbridge GU

- Guisborough

- Kirkby Moorside

- Middlesbrough

- Northallerton

- Scarborough

- Barwick-in-Elmet GU

- Ecclesall Bierlow

- Great Ouseburn

- Great Preston GU

- Huddersfield

- Knaresborough

- North Bierley

- Pateley Bridge

- Saddleworth

- Welsh Workhouse History

- Unions Summary List

- Crickhowell

- Aberystwyth

- Llandilo Fawr

- Newcastle-in-Emlyn

- Bangor & Beaumaris

- Bridgend & Cowbridge

- Merthyr Tydfil

- Abergavenny

- Montgomery & Pool (Forden)

- Machynlleth

- Newtown & Llanidloes

- Haverfordwest

- Irish Workhouse History

- Ballycastle

- Bailieborough

- Ballyvaughan

- Kildysart (Killadysert)

- Castletownbere

- Mitchelstown

- Schull (Skull)

- Ballyshannon

- Letterkenny

- Downpatrick

- Newtownards

- Dublin North

- Dublin South

- Enniskillen

- Lowtherstown

- Ballinasloe

- Mountbellew

- Cahirciveen

- Castlecomer

- Mountmellick

- Carrick-on-Shannon

- Manorhamilton

- Londonderry

- Magherafelt

- Newtown Limavady

- Claremorris

- Dunshaughlin

- Carrickmacross

- Castleblayney

- Parsonstown

- Strokestown

- Dromore West

- Tubbercurry

- Borrisokane

- Carrick-on-Suir

- Kilmacthomas

- Castletowndelvin

- Enniscorthy

- Baltinglass

- Scottish Poorhouse History

- Poorhouse Summary List

- Buchan (Maud)

- Old Machar (Aberdeen)

- Arbroath & St Vigean's

- Campbeltown

- Lorn (Oban)

- Lochgilphead

- Cunninghame (Irvine)

- (parts in Kelso )

- (parts in Stirling )

- Kirkpatrick-Fleming

- Upper Nithsdale

- Kirkintilloch

- East Lothian

- Dunfermline

- Long Island

- Kincardineshire

- Kirkcudbright

- Barony (Glasgow)

- Cambusnethan

- Douglas/Carnwath

- Glasgow City

- Mothwerwell

- New Monkland

- Old Monkland

- North Leith

- South Leith

- St Cuthbert's

- Athole & Breadalbane

- Upper Strathearn

- Abbey (Paisley)

- Renfrewshire

- Black Isle (Fortrose)

- Easter Ross (Tain)

- Lews (Lewis)

- Rhins of Galloway

- Wigtownshire (Stranraer)

- Scottish Almshouses

- Overview Map

- N.W. England

- S.E. England

- S.W. England

- N. Midlands

- S. Midlands

- W. Midlands

- Ireland: Leinster

- Ireland: Munster

- Ireland: Ulster

- Ireland: Connaught

- Overview map

- Lancashire/Yorkshire

- Workhouse Addresses

- Charlestown

- Blackwell's Island

- Entering & Leaving

- Classification

- Inside a workhouse

- Daily routine

- Rules & punishment

- Workhouse food

- Medical care

- Changing times?

- Before 1834

- Poor Law Commission

- Poor Law Board

- Local Govt Board

- Board of Guardians

- Visiting Committee

- Relieving Officer

- District MO

- Schoolteacher

- Medical Officer

- Labour Master

- Other Staff

- Parish Administration

- Bedford 1724

- Greenwich 1732

- Doncaster 1747

- Hackney 1750s

- Gilbert's Act 1782

- Isle of Wight 1792

- Trentham 1810

- Mildenhall 1830

- Walthamstow 1830

- Aylesbury 1831

- Shirley, Massachusetts 1841

- Outdoor Labour Test 1842

- Outdoor Relief Prohibition 1844

- Irish Workhouse Rules 1844

- Consolidated Order 1847

- Scottish Poorhouse Rules 1850

- Bathing Rules c.1910

- Poor Law Institution Order 1913

- Cottage Homes 1921

- Architecture

- Thomas W Aldwinckle

- J & W Atkinson

- William Donthorn

- A & C Harston

- Sampson Kempthorne

- William T Nash

- GG Scott & WB Moffatt

- Henry Saxon Snell

- William Thorold

- George Wilkinson

- Workhouse Gardens

- Workhouse Tour

- Cottage Homes Tour

- District School Tour

- Then and Now

- What are they now?

- Listing a Workhouse

- MAB History

- Ambulances - Land

- Ambulances - River

- Bridge Hospital, Witham

- Brook, Shooter's Hill

- Casual Wards

- Caterham Asylum

- Colindale, Hendon

- Darenth, Kent

- Downs Hospital, Sutton

- E. Hospital, Homerton

- Edmonton Colony

- Fountain Hospital

- Goldie Leigh Homes

- Goliath & Exmouth

- Gore Farm, Dartford

- Grove Hospital, Tooting

- Grove Park Hospital

- High Wood, Brentwood

- Hospital Ships

- Joyce Green, Dartford

- King George V, Godalming

- Laboratories

- Leavesden Asylum

- Long Reach, Dartford

- Mental Deficiency Homes

- Millfield, Rustington

- N. Hospital, Winchmore Hill

- N.E. Hospital, Tottenham

- N.W. Hospital, Hampstead

- Orchard, Dartford

- Park Hospital, Hither Green

- Pinewood, Wokingham

- Princess Mary's, Margate

- Queen Mary's, Carshalton

- Remand Homes

- S. Hospital, Dartford

- St Anne's, Herne Bay

- St George's, Chelsea

- St Luke's, Lowestoft

- St Margaret's, Kentish Town

- S.E. Hospital, Deptford

- S.W. Hospital, Stockwell

- Sheffield Street, WC2

- Tooting Bec Hospital

- W. Hospital, Fulham

- White Oak, Swanley

- Charity Refuges

- Common Lodging Houses

- Salvation Army Shelters

- Labour Colonies

- Aubin's School, Norwood

- Drouet's School, Tooting

- Metropolitan Infirmary for Children

- King's Cross

- Camden Town

- Model Lodging Houses

- Brookwood Cemetery

- Children in the Workhouse

- Workhouse Schools

- Workhouse Teachers

- District (Barrack) Schools

- Industrial Schools

- Apprenticeships

- Training Ships

- Cottage Homes

- Scattered Homes

- Boarding Out

- Certified Schools

- Charity Schools

- Sunday Schools

- Dame Schools

- National Schools

- British Schools

- Ragged Schools

- Church & Board Schools

- The Casual Ward

- Work in the Spike

- The Cellular System

- Social Explorers

- The Vagrant Population

- Tramp Signs & Slang

- Casual Ward Graffiti

- Commong Lodging Houses

- Newington Butts

- Anon ('One of Them')

- John Austin

- Charles Burgess

- Charlie Chaplin

- Will Crooks

- Arthur Crouch

- William Golding

- Beryl Johnson

- Laurie Liddiard

- Len Saunders

- Charles Shaw

- Margaret Wells-Gardner

- Inspections & Visits

- Broadside Ballads

- Humour/Satire

- Periodicals

- Births/baptisms

- Deaths/burials

- Parish records

- Union local records

- UK National Archives

- Census records

- Scottish records

- Other Useful records

- Archives Directory

- Links/Resources

- Workhouse Museums

- Online Museum

- Workhouse in Wartime

- Workhouse Myths

- Workhouse Quiz

- Ghost-hunting

- Citation of content

- Cookie Preferences

- Cookies Policy

- Privacy Policy

The Workhouse

Upton rd, southwell, ng25 0pt.

The Workhouse: Virtual Tour | Virtual Museum Tour

The Workhouse, also known as Greet House, in the town of Southwell, Nottinghamshire, England, is a museum operated by the National Trust. Built in 1824, it was the prototype of the 19th-century workhouse, and was cited by the Royal Commission on the poor law as the best example among the existing workhouses, before the resulting New Poor Law of 1834 led to the construction of workhouses across the country. It was designed by William Adams Nicholson an architect of Southwell and Lincoln, together with the Revd. John T. Becher, a pioneer of workhouse and prison reform. It is described by the National Trust as the best-preserved workhouse in England.

The building remained in use until the early 1990s, when it was used to provide temporary accommodation for mothers and children.

Join the conversation on Twitter: @NTWorkhouse Find out more: nationaltrust.org.uk

Back to The National Trust → More Cultural Spaces→

It’s a hard-knock life in Victorian workhouses

Victorian workhouses were a common institution throughout Britain's history. How much do you know about the controversial buildings?

Mention that you’re visiting a Victorian workhouse in Britain, and people will nod their heads and tell you how awful, cruel, and relentless they were. Still, considering the terrible standard of living among the 19th-century poor, were they really that bad?

We visit Southwell Workhouse to see how people really lived during the 19th century.

Step back to 1601 when the Poor Law charged parishes with providing Outdoor Relief for their own poor. The earliest workhouses provided non-residential paid work, but by the 1770s, the number of workhouses had soared to around 2000, and they had become residential.

The number of claimants exploded between 1795 and 1815, and the welfare bill increased four-fold. A union workhouse concept was put forward as a solution.

- 10 fictional landscapes to explore

- Have you seen this footage of the Royal Family at Windsor?

- The Cornwall of Daphne du Maurier

In 1835 the Poor Law Amendment Act abolished Outdoor Relief for the able-bodied poor. This meant that claimants that weren’t desperate enough to enter a workhouse received no financial assistance from the parish. It was the workhouse or nothing.

Southwell Workhouse in Nottinghamshire was flagged as a model workhouse, run by a union of parishes, and governed by an elected Board of Guardians. The workhouse regime was designed to discourage people from claiming relief, and it was hoped that some of the new workhouses might even turn a profit. From the beginning, free medical care and education were provided to inmates, giving them some advantage over the paupers outside.

Ghosts of residents past inhabit the now-quiet complex at Southwell, Notts: DANA HUNTLEY

Southwell's model workhouse

Today, Southwell Workhouse in Nottinghamshire is the UK’s best-preserved workhouse, providing a fascinating insight into the lifestyle of paupers that endured for more than a century.

The visitor tour begins with an introductory video. Then, you explore the arrivals building, where men, women, and children were separated. Once they’d been admitted, children were only allowed to see their families once a week. You see where inmates showered and changed into the workhouse uniform, before being shown to their dormitory and put to work.

It’s easy to imagine the sense of despair that desperate families must have felt when they were split up, with each individual sent to live in a different wing.

The massive, work-intensive laundry gives testimony to Victorian ideals of cleanliness: SUSIE KEARLEY

Inside the workhouse

The laundry next door houses mangles, scrubbing brushes, drying rails and laundry baskets. The sounds and smells of the laundry room, the wet hands, constant scrubbing, and humidity in the air, would have probably made this room unpleasant.

Outside are exercise yards and vegetable gardens, where residents tended to vegetables that went on sale to the public. The proceeds helped to fund the facility. Inside, the rooms are bright and airy, mostly painted cream, reflecting the colors used in the 1800s. On the upper floors, later color schemes include oppressive browns and greens from the 20th century.

Unlike some workhouses, Southwell was kept beautifully clean, and that’s reflected in its condition today. Inmates painted and washed the walls regularly. You can see the schoolroom for children with benches in neat rows. The dormitories contain rows of iron-frame beds, made up with comfortable mattresses, pillows, sheets, and blankets. The kitchen contains a big iron stove with copper pans, and workhouse menus—typically offering bread, gruel, meat, and potatoes. Visit the washrooms, offices, staff quarters, workrooms, and stroll around the kitchen garden, which today is maintained by volunteers.

The boring workhouse regime

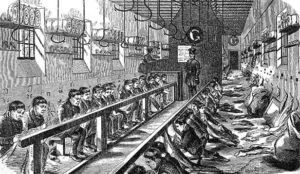

Southwell’s workhouse was designed to accommodate up to 158 residents, but numbers varied depending on the seasonal work available outside. The regime was tough, with inmates rising early to begin their 10-hour working day, seven days a week. They worked on a variety of tasks, including stone breaking for building projects, bone-crushing to make crop fertilizer, and picking oakum (old rope) for reuse in industry.

Much of the work was deliberately demoralizing, repetitive and unfulfilling. This was part of the deterrent. The rope picking task left many with sore hands, and inmates were given pointless tasks to do when the income-generating work ran out. Some inmates left the workhouse in the summer to take seasonal work on the farms, and then returned in the winter.

The vagrants’ dormitories have been demolished, but you can learn about the vagrants, who would travel from workhouse to workhouse; they could stay in one place for two nights only, in every 30 days. They weren’t allowed to stay anywhere permanently, because they didn’t belong to any parish. This policy spread the financial burden across parishes.

There’s an exhibition about William Henry Beveridge, a 20th-century British economist and social reformer, who wanted to eliminate “want squalor, ignorance, disease, and idleness.” It compares the Victorian workhouse to the modern welfare state, looking at what individuals received then, and what welfare claimants receive today. Newspaper reports about 21st-century food banks are on display—with recipients claiming that they can’t afford to eat. This puts the workhouse in a favorable light; in the workhouses, everyone got three square meals a day. The exhibit also poses some interesting modern dilemmas.

Accommodations may have been spartan, but they were far more sanitary than most homes: SUSIE KEARLEY

Demise of the workhouses

The last Victorian workhouses closed following the birth of the NHS in 1948 and the Housing Act of 1949. The old and infirm that had been residing in them were transferred to well-equipped care homes. While those that couldn’t find work were provided with money and accommodation elsewhere. It was the dawn of the modern welfare state. The workhouses became hospitals and care homes, offices and storage depots. Some workhouses were brought back into use by councils in the 1970s, to provide emergency accommodation for the homeless—you can see one made up as a self-contained family apartment today.

The closure of the workhouses marked the end of an era. It’s fortunate that some workhouses have been preserved, enabling new generations to learn about this aspect of our past.

* Originally published in Oct 2015.

BHT newsletter

You may also like.

- Most Recent

Is this the last-known footage o...

On this day in 1819, Queen Victoria was born. This footage of Queen...

Queen Victoria's coffin and the ...

A stern Queen, overcome by grief, who oversaw 63 years as the Monar...

The strict rules King Charles ma...

King Charles is quite particular with his tea...

Queen Elizabeth and David Attenb...

Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning monarch in British history...

Full English, a guide to a prope...

Breakfast: It's Britain's answer to soul food. The art of the prope...

Why King Charles first Trooping ...

June 17th, 2023, marked His Majesty's first Trooping the Colour as ...

Considering the history and heri...

Carlisle is a cathedral city in the North-West of England. Join Sus...

Somerset - the “Land of the Summ...

Take a day-by-day trip with us through Somerset, a county loaded wi...

Royal birth traditions you've ne...

We take a look back at some of the more outlandish royal birth trad...

- Advertise with us

- History Magazine

- History of Britain

The Victorian Workhouse

The workhouse is perhaps the most infamous of all 19th century institutions…

Jessica Brain

The Victorian Workhouse was an institution that was intended to provide work and shelter for poverty stricken people who had no means to support themselves. With the advent of the Poor Law system, Victorian workhouses, designed to deal with the issue of pauperism, in fact became prison systems detaining the most vulnerable in society.

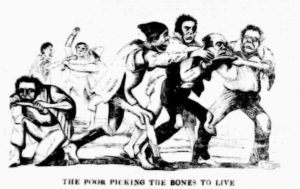

The harsh system of the workhouse became synonymous with the Victorian era, an institution which became known for its terrible conditions, forced child labour, long hours, malnutrition, beatings and neglect. It would become a blight on the social conscience of a generation leading to opposition from the likes of the Charles Dickens .

This famous phrase from Charles Dickens ‘Oliver Twist’ illustrates the very grim realities of a child’s life in the workhouse in this era. Dickens was hoping through his literature to demonstrate the failings of this antiquated system of punishment, forced labour and mistreatment.

The fictional depiction of the character ‘Oliver’ in fact had very real parallels with the official workhouse regulations, with parishes legally forbidding second helpings of food. Dickens thus provided a necessary social commentary in order to shine a light on the unacceptable brutality of the Victorian workhouse.

The exact origins of the workhouse however have a much longer history. They can be traced back to the Poor Law Act of 1388. In the aftermath of the Black Death , labour shortages were a major problem. The movement of workers to other parishes in search of higher paid work was restricted. By enacting laws to deal with vagrancy and prevent social disorder, in reality the laws increased the involvement of the state in its responsibility to the poor.

By the sixteenth century, laws were becoming more distinct and made clear delineations between those who were genuinely unemployed and others who had no intention of working. Furthermore, with King Henry VIII ’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536, the attempts at dealing with the poor and vulnerable were made more difficult as the church had been a major source of relief.

By 1576 the law stipulated in the Poor Relief Act that if a person was able and willing, they needed to work in order to receive support. Furthermore in 1601, a further legal framework would make the parish responsible for enacting the poor relief within its geographic boundaries.

This would be the foundation of the principles of the Victorian workhouse, where the state would provide relief and the legal responsibility fell on the parish. The oldest documented example of the workhouse dates back to 1652, although variations of the institution were thought to have predated it.

People who were able to work were thus given the offer of employment in a house of correction, essentially to serve as a punishment for people who were capable of working but were unwilling. This was a system designed to deal with the “persistent idlers”.

With the advent of the 1601 law, other measures included ideas about the construction of homes for the elderly or infirm. The seventeenth century was the era which witnessed an increase in state involvement in pauperism.

In the following years, further acts were brought in which would help to formalise the structure and practice of the workhouse. By 1776, a government survey was conducted on workhouses, finding that in around 1800 institutions, the total capacity numbered around 90,000 places.

Some of the acts included the 1723 Workhouses Test Act which helped to spur the growth of the system. In essence, the act would oblige anyone looking to receive poor relief to enter the workhouse and proceed to work for a set amount of time, regularly, for no pay, in a system called indoor relief.

Furthermore, in 1782 Thomas Gilbert introduced a new act called Relief of the Poor but more commonly known by his name, which was set up to allow parishes to join together to form unions in order to share the costs. These became known as Gilbert Unions and by creating larger groups it was intended to allow for the maintenance of larger workhouses. In practice, very few unions were created and the issue of funding for authorities led to cost cutting solutions.

When enacting the Poor Laws in some cases, some parishes forced horrendous family situations, for example whereby a husband would sell his wife in order to avoid them becoming a burden which would prove costly to the local authorities. The laws brought in throughout the century would only help to entrench the system of the workhouse further into society.

By the 1830’s the majority of parishes had at least one workhouse which would operate with prison-like conditions. Surviving in such places proved perilous, as mortality rates were high especially with diseases such as smallpox and measles spreading like wildfire. Conditions were cramped with beds squashed together, hardly any room to move and with little light. When they were not in their sleeping corners, the inmates were expected to work. A factory-style production line which used children was both unsafe and in the age of industrialisation , focused on profit rather than solving issues of pauperism.

By 1834 the cost of providing poor relief looked set to destroy the system designed to deal with the issue and in response to this, the authorities introduced the Poor Law Amendment Act, more commonly referred to as the New Poor Law. The consensus at the time was that the system of relief was being abused and that a new approach had to be adopted.

The New Poor Law brought about the formation of Poor Law Unions which brought together individual parishes, as well as attempting to discourage the provision of relief for anyone not entering the workhouse. This new system hoped to deal with the financial crisis with some authorities hoping to use the workhouses as profitable endeavours.

Whilst many inmates were unskilled they could be used for hard manual tasks such as crushing bone to make fertiliser as well as picking oakum using a large nail called a spike, a term which would later be used as a colloquial reference to the workhouse.

The 1834 Law therefore formally established the Victorian workhouse system which has become so synonymous with the era. This system contributed to the splitting up of families, with people forced to sell what little belongings they had and hoping they could see themselves through this rigorous system.

Now under the new system of Poor Law Unions, the workhouses were run by “Guardians” who were often local businessmen who, as described by Dickens, were merciless administrators who sought profit and delighted in the destitution of others. Whilst of course parishes varied – there were some in the North of England where the “guardians” were said to have adopted a more charitable approach to their guardianship – the inmates of the workhouses across the country would find themselves at the mercy of the characters of their “guardians”.

The conditions were harsh and treatment was cruel with families divided, forcing children to be separated from their parents. Once an individual had entered the workhouse they would be given a uniform to be worn for the entirety of their stay. The inmates were prohibited from talking to one another and were expected to work long hours doing manual labour such as cleaning, cooking and using machinery.

Over time, the workhouse began to evolve once more and instead of the most able-bodied carrying out labour, it became a refuge for the elderly and sick. Moreover, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, people’s attitudes were changing. More and more people were objecting to its cruelty and by 1929 new legislation was introduced which allowed local authorities to take over workhouses as hospitals. The following year, officially workhouses were closed although the volume of people caught up in the system and with no other place to go meant that it would be several years later before the system was totally dismantled.

In 1948 with the introduction of the National Assistance Act the last remnants of the Poor Laws were eradicated and with them, the workhouse institution. Whilst the buildings would be changed, taken over or knocked down, the cultural legacy of the cruel conditions and social savagery would remain an important part of understanding British history.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 8th August 2019.

History in your inbox

Sign up for monthly updates

Advertisement

Next article.

Rise to Power – Victorians

The Victorians and their influence - or how the Victorians put the 'Great' into Great Britain!

Popular searches

- Castle Hotels

- Coastal Cottages

- Cottages with Pools

- Kings and Queens

A Visitor's Guide to Victorian England

Michelle higgs' guide to the weird and wonderful world of victorian england.

THE VICTORIAN WORKHOUSE: THE LAST RESORT

I’ve been interested in workhouses since my university days so if I could take a trip to Victorian England, a workhouse would be on my list of places to visit. The visitors’ books of these institutions show that they were regularly visited by people like journalists, local worthies, guardians from the Board and ladies connected with charities, as well as official inspectors.

There’s a common misconception that all Victorian workhouses were dark, depressing places in which the poor were badly treated. That is, of course, a sweeping generalisation, especially as Queen Victoria’s reign spanned sixty-three and a half years of change. By the end of the nineteenth century, workhouses had altered dramatically and there had been a considerable improvement in conditions, particularly in the larger ones.

They remained the last resort for a large proportion of the poor, although there were still regular ‘ins and outs’ who used the workhouse according to their needs. Right at the end of the Victorian period, a reporter for Living London (1901) visited St Marylebone Workhouse. His article, particularly its accompanying photographs, clearly illustrate the differences between a late Victorian and a mid- Victorian workhouse.

In the women’s ward, gone are the drab, bare walls and the uncomfortable, backless benches. There are now pictures on the walls and vases of flowers on the tables. The old ladies sit on Windsor chairs at long tables, around which they congregate and chat. There’s even a rug in front of the stove.

By 1900, this accommodation was more common in city workhouses. The aged married couples’ quarters at St Marylebone consisted of “ten little tenements for as many Darbies and Joans – one room, one couple – and a general room at the end for meals, the ‘private apartments’ form a sort of miniature model dwelling that overlooks the Paddington Street Recreation Ground. Admirable is the only word for this division. The brightly, painted walls, the pictures, the official furniture including a chest of drawers and a table, the photographs and knick-knacks belonging to the inmates, who are allowed to bring in such property and arrange it as they choose – all this makes a ‘private apartment’ home-like and a delight to the eye. If an old couple must spend their last days in the workhouse, one could wish them no brighter or more healthy quarters.”

Another improvement made from the 1880s onwards (and even earlier in London) was to house the children away from the workhouse. The workhouse unions moved towards boarding out their pauper children within the parish as a better, more humane alternative to keeping them in the workhouse. Children were boarded out with ‘foster parents’ who were vetted by the union and paid to look after them. Other workhouse unions chose to set up ‘scattered’ or cottage homes, or district schools instead. The lack of children in the workhouse, unless they were casual admissions, meant that the inmates were mostly old and infirm. Many of the old men and women were ex-servants who had never had homes of their own. The journalist for Living London commented that in the kitchen there was “a mincing machine, one of the uses of which is artificially masticating the meat supplied to old and toothless paupers”.

In 1900, the Local Government Board ruled that outdoor relief be given to the ‘aged deserving poor.’ If indoor relief was necessary, it was recommended that the elderly be “granted certain privileges which could not be accorded to every inmate of the workhouse”. These privileges were to include “flexible eating and sleeping times, greater visiting rights, and the compulsory provision of tobacco, dry tea (so that they could make a cup whenever they wanted) and sugar”.

More concessions were granted to elderly inmates including the recommendation by the Local Government Board that separate day-rooms should be provided for those who had “previously led moral and respectable lives”. By the end of the nineteenth century, the majority of unions were implementing some kind of segregation on moral grounds, particularly for elderly inmates.

For many elderly inmates, the workhouse really was a godsend, especially if they were seriously ill and needed hospital treatment. However, in spite of the increased comforts offered, becoming an inmate was a bitter pill to swallow for those who had been fiercely independent and had always been able to get by and look after themselves. The fact remained that they were likely to end their days in the workhouse and suffer that most shameful fate – a pauper burial.

Share this:

4 thoughts on “ the victorian workhouse: the last resort ”.

I agree the workhouses have had a bit of a bad reputation although they were set up in a spirit of philanthropy. I have heard that the popular music hall song, My Dear Old Dutch, refers to the practice you mention of splitting up elderly married couples, even when they'd been together for \”forty years\”. Not sure if that's true?

Hi Frances. Thanks for your comment. I'm afraid I don't know if that song 'My Old Dutch' relates to the practice of the workhouse splitting up elderly married couples, but I'm sure someone on Twitter will know!

I've done some research and find the song 'My Old Dutch' was written and performed by Albert Chevalier and made into a silent film in 1915 in which an elderly couple are rescued from the workhouse by their prodigal son. Am now tracking down a print. Thanks for setting me off on this!

Hi Frances. That's fascinating! Thank you for letting me know and please keep me updated.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Victorian Children

Victorian Children and Life in Victorian Times

Victorian Workhouse

The Victorian Workhouse was a place where the poorest of the poor lived and worked. It was an incredibly difficult place to live, with very poor living conditions. The people who lived and worked there were from all walks of life. They might be widows, criminals, orphans, gamblers or people who lost their job. But they all had one thing in common – they were desperately poor.

In this article, we will take a look at the types of people who lived and worked in the Victorian Workhouse, and we will also explore the appalling living conditions that they endured.

Why And When Were The Victorian Workhouses Created?

The Victorian Workhouse was established in 1834 by Sir Robert Peel, a famous Victorian and arguably one of the best politicians in the Victorian era. Peel privately believed that the government should look after people rather than say “Sir, you are poor; therefore I will not have anything to do with you”, but also believed that assistance should be given for a fee. The New Poor Law Act was introduced in 1834.

These workhouses were designed to make able-bodied people go out and work by offering shelter for wage earners, day workers, and apprentices where there wasn’t any work available locally.

There were strict rules imposed on inmates of these institutes, including no begging or receiving charity money.

Who Lived In The Victorian Workhouses?

The people who lived and worked in the Victorian Workhouse were from all walks of life. They included the very poorest of the poor, as well as criminals, the homeless, unmarried mothers, the elderly, and the mentally ill. The living conditions in the workhouses were awful, but for many it was better than the alternative.

Managing The Workhouse

Workhouses were administered by ‘Unions’ of multiple parishes, each governed by a Board of Guardians. These boards were responsible for overseeing the operation of the workhouses, ensuring they functioned as intended under the Poor Law.

Upon entering a workhouse, inmates were categorized based on age and ability, leading to the strict segregation of families. This meant husbands were separated from wives, and siblings were divided, a practice that was as efficient as it was heart-wrenching.

Uniforms and Personal Belongings

New inmates were issued uniforms made from durable materials like wool and linen. These uniforms replaced their personal clothes, which were disinfected and stored until their departure. This practice not only maintained hygiene but also symbolized the loss of personal identity upon entering the workhouse system.

What Were The Conditions Like Inside The Victorian Workhouse And Punishments?

The conditions inside the Victorian Workhouse were appalling. Inmates lived in total poverty and squalor, and most of them were malnourished and poorly clothed. There was very little food available, and the available food was often low quality. In between meals, they had to earn their food and bed by working hard at the jobs given to them by their guardians.

In addition, the living quarters were extremely cramped and unsanitary. The inmates were also subjected to frequent beatings and other forms of punishment.

What Was The Food Like Inside A Victorian Workhouse?

The typical Victorian food that was available in the Workhouse was often of very low quality and sometimes rotten.

For breakfast, they were served gruel, a kind of porridge made from oats and water. For the main meal of the day, they would have been served a broth or soup made from low-quality meat and whatever vegetables were in season.

What was a typical day like in the workhouse?

The inmates were woken in the morning by a tolling bell, and this same bell called the inmates to breakfast, dinner and supper.

Inmates’ days were strictly scheduled, with specific hours for waking, meals, work, and leisure. Women typically engaged in housekeeping duties, while men undertook more physically demanding tasks like stone breaking and oakum picking.

In 1835, the Poor Law Commissioners laid out the timings of the workhouse day as follows:

What was life like for a child in a Victorian workhouse?

Life for Victorian children in the workhouse was incredibly harsh and often bleak. These institutions, designed as a last resort for the destitute, were intentionally made unpleasant to discourage reliance on state support. For children, this environment was particularly difficult and unforgiving.

Most children in a workhouse were orphans. Everyone slept in large dormitories. It was common for younger children to sleep four to a bed. Workhouses were known for their strict discipline and minimal comfort. Children often lived in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, which led to the spread of diseases.

The workhouse were required by law however, to provide at least three hours of schooling. Education covered basic but valuable skills like reading, writing, and arithmetic, along with religious studies.

Link / Cite this Page

<a href="https://victorianchildren.org/victorian-workhouse/">Victorian Workhouse</a>

Stewart, Suzy. "Victorian Workhouse". Victorian Children . Accessed on April 10, 2024. https://victorianchildren.org/victorian-workhouse/.

Stewart, Suzy. "Victorian Workhouse". Victorian Children , https://victorianchildren.org/victorian-workhouse/. Accessed 10 April, 2024.

Workhouse Museum & Garden

Top ways to experience nearby attractions

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as wait time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

Also popular with travelers

Workhouse Museum & Garden - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

- Sun - Sat 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM

- (0.15 mi) Crescent Lodge

- (0.10 mi) OYO The White Horse

- (0.07 mi) Central townhouse with hot tub jacuzzi bath and 3D TV room

- (0.15 mi) The Unicorn

- (0.14 mi) Box Tree Cottages

- (0.04 mi) The Golden Lion

- (0.07 mi) Realitea

- (0.07 mi) Storehouse Kitchen

- (0.08 mi) Oliver's Pantry

- (0.10 mi) North Street Fisheries

HISTORIC WORKHOUSES YOU CAN VISIT IN THE UK

Britain’s history of poor relief over the last four centuries, while not ideal nor always humane, nevertheless probably saved many from abject poverty and starvation. Few workhouses remain accessible to the public - most were converted to other uses. However, across the UK are a handful which are open to the public who can learn about their bleak past.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF WORKHOUSES IN THE UK

Tudor governments wrestled with problems of a growing population and an increase in hardship and vagabondage. The Elizabethan Poor Laws recognised unemployment as a genuine problem and sought to give help, particularly to the deserving poor, in the form of handouts described as “outdoor relief”.

In the early 18th century workhouses were built to provide “indoor relief” in the form of residential support – but such places had deliberately harsh conditions to deter any idlers from applying.

Poverty continued to be a major concern, particularly after unemployment and poor harvests following the Napoleonic Wars, so in 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act grouped parishes into Unions to provide workhouses, paid for by ratepayers and administered by a Board of Guardians. Outdoor relief was ended so there was no choice for the impoverished other than the workhouse.

Bleak conditions were intentional in an attempt to encourage people to find employment rather than rely on charity. Men and women were separated into different communal wards. The able-bodied had to work for their keep, the women on domestic tasks, the men on physical labour. Orphaned and abandoned children joined the children of adult inmates.

Uniforms were generally compulsory and added to the stigma of being in the workhouse. Food was monotonous and there was very little medical care until the 1880s.

Workhouses were formally ended in 1930 but did not disappear totally until the 1948 National Assistance Act provided support for all those not covered by the new National Insurance schemes.

Today many workhouse buildings remain intact, but have been converted to other uses such as the workhouse in Andover in Hampshire, which is now residential. No 48 Doughty St. in London now houses the Charles Dickens Museum. However, a few have been adapted to show visitors something of the history and conditions of these institutions, once such a familiar part of British towns and cities.

Workhouse Museum, Ripon, Yorkshire

Photograph © Rippon Museums

There has been a workhouse on this site since 1776, the current building being completed in 1855.

In 1832 it had 33 inmates with the able bodied men set to the task of breaking stones. There is much to see on a visit here – the Receiving Ward, Guardians’ Room, Bathing Area, Vagrants’ Cells, kitchen and dining area as well as the Master’s accommodation and a recreation of the original kitchen garden where the women grew the vegetables.

Exhibitions reveal what life was like and include this sad rhyme;

Hush-a-bye baby, on a tree top. When you grow old your wages will stop. When you have spent the little you made, first to the poorhouse and then to the grave.

Over time the institution acquired its own teacher, chaplain and infirmary and even had its own van to transport lunatics to asylums if they became violent. Ripon also has a Prison and Police Museum and a Courthouse Museum to complement a visit to the Workhouse Museum.

Rippon Workhouse Museum website >>

The Workhouse, Southwell, Nottinghamshire

Photograph © DeFacto

Built in 1824, the workhouse here is exceptionally well preserved and is now in the ownership of the National Trust.

The Rev John Becher and George Nicholls developed a system which was copied by other institutions across the country. They believed that the workhouse should be seen as a last resort - a place of work with restricted and regulated conditions meant to deter potential applicants.

However, it should also provide moral improvement, and children and the old and infirm should be cared for. Southwell had up to 158 inmates at any one time. The museum recreates some of the way of life for inmates and also looks at the establishment of the Firbeck Infirmary built in 1871 to serve the sick and infirm.

Southwell Website >>

Gressenhall Farm, Norfolk

Photograph © Gressenhall Farm

One of the best preserved workhouse buildings in the country, much of it dating from 1777, Gressenhall houses a large collection of workhouse objects, images and archives in the UK.

The museum has concentrated on producing a Voices from the Workhouse project to bring alive to modern generations the conditions for these inmates of the past, including their work, food and living areas. There is also a punishment cell for those unfortunate enough to cross the authorities.

Male inmates here had to do the monotonous task of oakum picking – picking out fibres from old ropes and cable to mix with tar or grease and use as caulking on ships. This did not end until 1925.

Gressenhall Farm Website >>

Red House Museum, Christchurch, Dorset

The building dates from 1764 and was the parish workhouse for Christchurch and Bournemouth until 1886.

The interior has been altered but the kitchen fireplace dates back to the days of the workhouse. Many of the women and children here were employed to make fusee watch chains which was a traditional trade of the town, and there are exhibits and photographs to illustrate these times.

The galleries also show the social and industrial life of Victorian and Edwardian Christchurch as well as looking at more recent history.

Red House Museum Website >>

The Weaver Hall Museum and Workhouse, Northwich, Cheshire

Photograph © West Cheshire Museums

The museum is housed in the Victorian workhouse which was opened in 1839 following the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834.

65 local parishes and townships of mid Cheshire combined to form a single Union and the building was designed following the standard model, with wards for men and women. In 1850 a fever hospital was added, and in 1863 baths were included.

The museum has a short introductory film about its days as a workhouse, an old schoolroom where the children were taught and there are photos and stories about some of the inmates. Other displays record the salt industry of the area and other aspects of Cheshire’s social, cultural and industrial history.

Weaverhall website >>

Vestry House Museum, Walthamstow, London

Photograph © Vestry House Museum

Vestry House was the parish workhouse from 1730 to 1841. A gallery of this museum is dedicated to the lives of the poor and destitute who came here when there was nowhere else to go.

The garden has been recreated as the 18th century workhouse garden, including useful plants like herbs and dyes as well as vegetables. The museum has a police cell and looks at other aspects of life in the Walthamstow Forest through the ages.

Vestry House Museum w ebsite >>

Llanfyllin Workhouse, Powys, Wales

Photograph © Llanfyllin Workhouse

The Llanfyllin Workhouse opened in 1840, remained as an old people’s home and did not finally close until the 1980s.

Since 2004 its history has been thoroughly researched and it now has a dramatised documentary film as an introduction to various displays. There is a detailed look at life in the workhouse including diet and schooling. Children can try picking oakum and dress in a workhouse uniform. There are oral histories from local people who remember the workhouse in its final years.

Llanfyllin Workhouse website >>

The Spike Heritage Centre, Guildford, Surrey

Photograph © The Spike

In 1837 work began to erect a workhouse for the newly created Guildford Union. By 1895 it was seriously overcrowded so work began on a new “casual” ward for the vagrant poor.

The vagrants were considered to be undesirable so were kept away from the main workhouse and made to do hard labour in return for a night’s board and lodging. The ward became known as the Spike, a reference to the tool used by the casuals to pick oakum.

A Tramp Master and Mistress were in charge of the ward, checking people for alcohol, sending their clothes to be disinfected and locking them in separate cells for the night. The original cells remain, three of which have grilles across the windows – vagrants had to push broken rocks through the grille to ensure they were of a small enough size.

The Spike website >>

Related Posts

12 ARTS AND CRAFTS HOUSES YOU CAN VISIT IN ENGLAND

14 UNDERGROUND BUNKER MUSEUMS YOU CAN VISIT IN THE UK

13 PRISON MUSEUMS YOU CAN VISIT IN THE UK

Commentaires

Workhouse History Centre

Attraction information, get in touch, found a problem with this page report it here.

- Children Welcome

- Mobility Accessibility Facilities

- Pets Accepted

Like what you see?

Take a look around, about workhouse history centre, 52.7590027, -3.260361, related stories, visit our unesco world heritage sites in wales.

Find out how to make the most of your visit to each of the four UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Wales.

- UNESCO Heritage

- Amazing places

Instagram-friendly Welsh landmarks

Take a look at these ten must-see Instagrammable coastal landmarks for you and your camera.

- Countryside

Is Wales the castle capital of Europe?

With over 400 castles, wherever you go on holiday in Wales, you won't be too far from one to visit.

- Historic buildings

A Royal Mint experience

Discover the history of coins and how they are made at the Royal Mint Experience in Llantrisant.

Before you start...

This site uses animations - they can be turned off.

Terms and Conditions

By using this site, you confirm you agree to our Terms and Conditions .

We'd Like to Hear From You

By answering a few questions , we'll give you the chance to win £500. By doing so you will also help us improve this website and help with your holiday planning and travel needs.

Good for you. Good for us. Teamwork!

- Discover & learn

Family-friendly places with Victorian history

Take a trip into the past with your family at a place with Victorian history. Whether you're admiring rare trains built in the Victorian era or practising your handwriting on slates, there are plenty of opportunities to experience life as a Victorian.

Enjoy some family fun

Looking for places the whole family will enjoy? Discover family-friendly cycling trails, places to get closer to nature and historic buildings where you can learn about the past.

You might also be interested in

Family-friendly castles to visit

Looking for enchanting family days out? Look no further than these fairy-tale castles, perfect for days out with little knights and dragon-slayers.

Places with First and Second World War connections

From weapons testing sites to homes for evacuees, discover some of the places you can visit to learn about how the First and Second World War impacted all areas of life.

Family-friendly places with Roman history

Unearth ancient Roman history with your family at these places, which are filled with Roman history – from forts and walls to bathhouses and pubs.

Places with Tudor connections

Discover the places we look after that have links to the Tudor period, from prominent figures like Henry VII and key events such as the dissolution of the monasteries. They’ve received royal visitors, hidden Catholic priests and witnessed important events.

How gruelling was the Victorian workhouse?

Peter Higginbotham argues that the Victorian institutions weren’t necessarily the grim hell-holes portrayed by Charles Dickens

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

Listen to this article:

“Tory spending cuts send us back to the misery of the Victorian workhouse,” cried a Mirror headline in 2010. Workhouses were “bleak, grimly austere and oppressive”, wrote the author of a study of one local institution in 2012. Ever since Charles Dickens ’ Oliver Twist began publication in 1837, the establishment he described, and numerous on-screen representations of it, have become the filter through which the institution is invariably viewed. Portrayals of the workhouse habitually take it as read that it was unremittingly horrific, harsh and dehumanising. But was it really that bad?

The Victorian workhouse first came about as a result of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. This act transferred the administration of poor relief from individual parishes to a coordinated national system based on new groupings of parishes, known as Poor Law Unions. Each union, run by a locally elected Board of Guardians, provided a workhouse to serve the whole union area. For the able-bodied destitute and their dependants, the workhouse was intended to be the only help on offer. The operation of the New Poor Law was overseen by a central authority – originally the Poor Law Commission (PLC), later the Poor Law Board (PLB) and then the Local Government Board (LGB).

It’s often assumed that Oliver Twist was set in one of the new union workhouses, or “bastilles”, as critics such as MP and journalist William Cobbett labelled them. However, it is clear that it was actually located in one of the pre-1834 parish-run establishments, where there was no uniformity in matters such as work or diet.

Everyone knows, of course, exactly what workhouse inmates had to eat: gruel. In Oliver’s workhouse, there were “three meals of thin gruel a day, with an onion twice a week, and half a roll on Sundays”. But, in the entire workhouse era, before or after 1834, there was never an establishment with such a diet on offer.

More like this

A typical parish workhouse menu was that at Westminster St Margaret, where breakfast was bread with either broth or gruel, and supper was bread with butter or cheese. Midday dinner could be meat and broth, pease pottage, baked puddings, or hasty pudding – oatmeal boiled in milk. In the 1830s, the lucky inmates of the Brighton workhouse received six meat dinners a week, with no limits on quantity, plus two pints of beer a day for the men or one pint for women and children. The inmates were served at table, with the governor carving for the men and boys, and the matron for the women and girls.

The new union workhouses had to adopt one of six standard dietaries issued by the PLC in 1835. Dietary No 1, for example, provided able-bodied men with a daily breakfast of bread and gruel, a dinner of either soup or, on three days a week, meat and potatoes, and a supper of bread and either cheese or broth. The elderly could exchange their gruel for a weekly ration of butter, tea and sugar.

Although this menu compared well to that typically consumed by poor labourers living outside the workhouse, the food was not without shortcomings. Ingredients purchased by workhouses were usually low grade and often suffered from adulteration. A report in 1866 revealed huge variations in the nutritional value of the same dish at different establishments. For instance, a pint of gruel at Scarborough workhouse contained 4 ounces of oatmeal, while at Easingwold it was just 1.5 ounces.

Workhouses could compile their own menu from a list of dishes including Irish stew, pasties, shepherd’s pie and roly-poly pudding

In 1883, in an effort to improve inmates’ health, the LGB suggested that workhouse inmates be given a weekly cooked fish dinner. Although the experiment was successful in some places, such as Bristol, more typical were the reactions at Ludlow, where some inmates claimed that fish “disagreed” with them. In 1897, a trial of dietary improvements at Bethnal Green workhouse hit the headlines after an inmate was said to have died from overeating. From 1901, reflecting the fact that inmates were by then mostly the elderly or sick (and therefore had more limited appetites), workhouses could compile their own weekly menu from a list of approved dishes including treats such as Irish stew, pasties, shepherd’s pie and roly-poly pudding, with an accompanying cookbook to ensure uniformity of ingredients and preparation.

- Listen | From daily routines to whether inmates really ate gruel, Peter Higginbotham responds to listener questions about the workhouse

Vermin-infested rags

Another common misconception is that the poor were “sentenced” to the workhouse. Entering a workhouse was essentially a voluntary decision, though many people’s circumstances left them little option other than to accept the offer of a place. The workhouse admission process included the issuing of workhouse clothing, which has sometimes been viewed as a deliberate strategy of dehumanisation. But for new inmates who arrived with just the clothes they stood in, possibly little more than vermin-infested rags, the provision of two sets of clean and serviceable clothes was a very practical – and often welcome – measure.

The clothing did, however, provide officials with a degree of control. Although inmates could discharge themselves at any time, subject to a few hours’ notice, and have their own clothing returned to them, any unauthorised exit from the premises while wearing workhouse clothing could lead to a charge of stealing union property. For those who did decide to leave, there was no financial or other assistance in finding work or accommodation. Thus, to some degree, the workhouse could be viewed as a poverty trap.

For a group known as the “ins and outs”, though, the workhouse clearly held no fear. Such individuals treated the institution like a free lodging house, staying for a few days or weeks at a time and then discharging themselves. During 1901, 81-year-old Julia Blumsun admitted herself into the City of London workhouse on 163 separate occasions. Other individuals appear to have positively preferred to live in a workhouse, such as the inmate of Leigh workhouse in Lancashire, who in 1922 was discovered to have £500 in the bank.

- Read more on the Victorian war on child poverty

One group for whom the workhouse did attempt to provide a route out of poverty was children. Since Elizabethan times, pauper children had been placed into apprenticeships as part of the poor relief system. Although the impression given by the 1968 film Oliver! is that workhouse boys were “for sale”, this was not the case – in reality, their new masters were paid a premium for taking them on. However, by the late 1830s, there was growing evidence of apprentices being exploited or abused by tradesmen whose only interest was the premium. A report in 1842 found that the boys apprenticed as mine workers by the Dewsbury Board of Guardians included five-year-old Thomas Townend, though he was returned after 16 days.

To replace apprenticeships, James Kay-Shuttleworth, an assistant poor law commissioner, proposed giving such children “a careful training in religion and industry”, with instruction in skills such as carpentry, shoe-making and tailoring or, for girls, domestic work, making them employable in adult life. The training could either be within the workhouse or, ideally, in separate accommodation, to remove children from the “contamination” of adult paupers. A number of unions set up their own separate schools or jointly operated district schools, some housing hundreds of children. In 1850, Charles Dickens visited one such school, at Norwood, and wrote that its inmates might leave the establishment “almost with the certainty of becoming good and prosperous citizens”. However, such institutions began to attract criticism as being impersonal and serving as breeding grounds for disease.

From the 1870s, “cottage homes” developments became popular. These placed children in purpose-built miniature rural villages, complete with a school, chapel, hospital, laundry and workshops, with family-style groups of 10 to 20 children living in each “cottage” under the care of a house mother. From the 1890s, the family-group principle was transplanted to “scattered homes” based in ordinary houses placed around the suburbs of larger towns.

Divided families?

As well as the influence of Oliver Twist , the reputation of the union workhouse in its early years was assaulted by anti-Poor Law sections of the press which publicised any negative story about the institution, no matter how dubious its origins. Opponents of the New Poor Law particularly criticised the separation of husbands and wives and of parents and children required by union workhouses. In 1843, after an infant at Bethnal Green workhouse was reportedly removed from its mother except when being breastfed, Punch published a cartoon titled The “Milk” of Poor Law “Kindness” , showing a baby being torn from its mother’s arms. In fact, workhouse regulations allowed children under seven to reside in the female wards and their mothers to have access to them at all reasonable times. In theory, a parent could request a daily “interview” with their child, although a common arrangement was for parents to have time with their children on Sunday afternoons.

Opponents of the New Poor Law particularly criticised the separation of husbands and wives, and of parents and children

Separation of men and women was said to be enforced for reasons of “discipline”. Since many workhouses had just two live-in staff (the master and matron), the measure no doubt assisted the management of such institutions. Husbands and wives both over 60 could request a separate sleeping apartment, but the provision of such facilities varied widely.

“Unclimbable” fences

Yet inmates still managed to find ways around the restrictions. In 1905, to clamp down on such activities, Steyning workhouse installed “unclimbable” fencing between the men’s and women’s yards. After it became clear that inmates were still somehow managing to arrange secret trysts, an inquiry discovered that the male and female sides of the workhouse were communicating by using the general letter post. On one occasion, some resourceful female inmates at the Ross workhouse dressed themselves in men’s clothing and got into the men’s ward.

Until the 1870s, a workhouse could be an unfortunate place to fall ill. Workhouse infirmaries were often cramped and poorly ventilated, and nursing was mostly carried out by elderly female inmates who, like Mrs Gamp in Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit , were often illiterate and frequently drunk. Such nurses typically received a daily ration of beer and no doubt dipped into items such as brandy and porter that were often prescribed for patients.

There were exceptions, though. After Dickens visited the Liverpool workhouse infirmary in 1860, he recorded that “all the arrangements of the wards were excellent. They could not have been more humane, sympathising, gentle, attentive, or wholesome.” In the 1860s, a major campaign to improve medical facilities in London’s workhouses gradually led to the widespread provision of new infirmary buildings and employment of trained nurses, something in which Florence Nightingale was influential. And from the 1880s, workhouse infirmaries increasingly provided treatment for non-inmates who couldn’t afford to pay for the services of a doctor, effectively becoming local hospitals for the poor.

Taking a long view, the toughest time for workhouse inmates was probably in the first three decades of the New Poor Law, when the focus was on deterring able-bodied men from claiming poor relief. By the 1890s, however, things had changed considerably. Inmates able to work were more likely to be occupied in gardening or chopping firewood, or something related to their own trade, rather than the stone-breaking and oakum picking of earlier times.

Some aged poor now had brightly decorated wards with comfortable furniture, and were even able to keep their own small pets

The elderly often received a weekly ration of smoking tobacco or snuff and were provided with books and newspapers. At Macclesfield workhouse, the “respectable” aged poor now had brightly decorated wards with comfortable furniture. They could wear their own clothes, retain a few of their own possessions, keep small pets, were served afternoon tea, and could go out to visit friends each day. By 1914, the older inmates at the Ross workhouse had mixed dayrooms and individual cubicles in their dormitories. Fixed mealtimes had been abandoned, and inmates even had weekly trips to the cinema.

Despite popular perceptions, the regime and physical conditions in workhouses evolved enormously over the years. For many people, though, that was irrelevant. It was the overwhelming shame and stigma that had become associated with entering the workhouse that meant they would rather die than pass through its doors.

Songs, semolina and Santa Claus: Two previous inmates reflected on their time in the workhouse as children

“we made our own fun”, “we were regimented like the army”.

Peter Higginbotham is the author of The Workhouse Encyclopedia (The History Press, 2014). He has also appeared on our podcast, as an expert on workhouses for our Everything You Wanted to Know series

This content first appeared in the September 2021 issue of BBC History Magazine

Receive a hardback and signed copy of a book of your choice when when you subscribe for £24.99 every 6 issues.

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

Subscriber today and get your Summer Read

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership & 15% Chalke History Tickets

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

Victorian Workhouses (KS2): Everything You Need To Know

Why And When Were The Victorian Workhouses Created?

Who lived in the victorian workhouses, what were the conditions like inside the victorian workhouse and punishments, what was the food like inside a victorian workhouse.

Image © Bill Lowe via Facebook.

Victorian Workhouses were not only essential for Victorian England but are also a key part of the KS2 curriculum and this handy guide is here to explain the ins and outs!

As places that seem so foreign nowadays, workhouses were extremely common in Victorian society, serving as a place where poor people would be sent if they had nowhere to live or no job to earn their keep by working.

Both children, orphans and adults were sent to workhouses and the living conditions, general treatment of people and the workhouse system was extremely harsh.

Plus, to brush up on more KS2 Victorian knowledge before you get to grips with these Victorian workhouse facts, check out our nasty guide to Victorian Crime and Punishment or step back in time and have a read of our guide to Victorian Toys and Games.

Prior to 1834, those that were poorer within Victorian society were looked after by the money collected from wealthier individuals, such as landowners. These people would provide the money for both children and adults so they could get adequate clothing and food.

However, this shortly changed after The Poor Law Amendment Act, also known as the New Poor Law Act, was introduced later on in 1834.

This cruel law was passed and it ensured that no able-bodied person could get poor relief. The idea was that poor people were meant to support and provide for themselves but, in turn, this meant that a lot of people, including children, were left with no income to purchase basic food and clothing.

Instead, they were to be sent to workhouses, which were essentially large houses, where they could earn their keep (which means money) by doing mundane jobs.

The Victorian Workhouses provided people with a place to live, a place to work and earn money, free medical care which was super important during the Victorian era, food, clothes, free education for children and training for a job.

Plus, most amenities were provided on-site including a dining-hall for eating, dormitories for sleeping, kitchen, school-rooms, nurseries, rooms for the sick, a chapel, a mortuary and more.

Image © Hammersmith Palais Old Skool via Facebook

The Victorian Workhouse was feared by most people, including the poor and the elderly.

As part of the government’s plan to avoid encouraging ‘idlers’, meaning lazy people, Victorian Workhouses was an extreme threat to the elderly, who are sometimes unable to perform the same manual labour/work as those younger than them, as well as poorer people, who perhaps cannot access the necessary resources to have a job.

As well as the people being sent to the workhouse, including children, there was also a whole host of staff who would operate at the workhouses daily. For example, typically, there was a Master, a Matron, a Medical Officer, a Chaplain, a porter and normally a school-teacher.

Additionally, orphaned (children with no parents) and abandoned children, the physically and mentally sick, the disabled, the elderly and unmarried mothers could also be found in the workhouse.

Plus, it was extremely common for families that were sent to the workhouse to be split up; women, children and men all had different living and working areas in the workhouse and therefore it was normal for them to be separated. And if that wasn’t bad enough, families could be punished for attempting to speak to one another!

Image © Audrey Nye via Facebook

As far as looks go Victorian Workhouses typically consisted of stark, undecorated, prison-like structures, with no curves, just sharp corners.

High walls surrounded the entire workhouse making it impossible to catch a glimpse of the outside world, the windows were a whopping six feet from the floor, and a further 'refinement' meant that some of the window sills were on a downward slope, so as to prevent the inmates from resting or sitting on them.

In the workhouses in the Victorian era, inmates were made to wear uniforms, making it impossibly hard to distinguish people as well as demonstrating their ‘identity’ to those in the outside Victorian world.

For women, this consisted of a shapeless dress, made of striped (convict-style) fabric and for men, a striped shirt, ill-fitting trousers, as well as a thick vest and a coarse jacket.

All inmates wore hob-nailed boots that were extremely durable.

Punishments inside of Victorian Workhouses ranged from food being withheld from inmates so they would starve, being locked up for 24 hours on just bread and water to more harsh punishment including being whipped, being sent to prison and meals stopped altogether.

Image © Sara-K Creates via Facebook

One the whole workhouse food would be largely tasteless and a key part of the diet for those inside a Victorian Workhouse was bread. For larger workhouses inmates were forced to sit in rows, all facing the same way, in some cases with separate dining halls for men and women.

At breakfast in the workhouse, typically, gruel or porridge was served, both made from water and oatmeal, and at dinner, it was normally workhouse broth which consisted of the dinner meat water, as well as a few vegetables mixed in.

The mid-day dinner was the meal that contained the most variation with some days being meat and potatoes - the meat was typically cheap cuts of beef or mutton and the potatoes were likely to be grown in the workhouses own garden - and other days being soup - which would typically be a broth with some vegetables added and occasionally thickened with barley, oatmeal or rice - no room for fussy eaters here!

Plus, you might be surprised to learn that tea was actually served in the workhouse but not as we know it. Tea was often served without milk, for the elderly and infirm at breakfast.

Not to mention the pudding, which was typically a form of pudding, for example, suet pudding which might have been served with sultanas or gravy, especially if it was being consumed by children or infirm.

We Want Your Photos!

More for you, 36 illinois facts: history, geography, and more, 55 enlightening factory farming facts and their uses.

Bachelor of Arts specializing in English

Ellie Sylvester Bachelor of Arts specializing in English

As a passionate Londoner, Ellie enjoys exploring the city's theaters and food markets with her younger siblings. She has a Bachelor's degree in English from the University of Nottingham. She's particularly fond of Primrose Hill and the Natural History Museum, as well as the constantly changing Spitalfields Market. In addition to her love of theater, Ellie also enjoys trying new foods and dabbling in musical theater.

1) Kidadl is independent and to make our service free to you the reader we are supported by advertising. We hope you love our recommendations for products and services! What we suggest is selected independently by the Kidadl team. If you purchase using the Buy Now button we may earn a small commission. This does not influence our choices. Prices are correct and items are available at the time the article was published but we cannot guarantee that on the time of reading. Please note that Kidadl is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. We also link to other websites, but are not responsible for their content.

2) At Kidadl, we strive to recommend the very best activities and events. We will always aim to give you accurate information at the date of publication - however, information does change, so it’s important you do your own research, double-check and make the decision that is right for your family. We recognise that not all activities and ideas are appropriate for all children and families or in all circumstances. Our recommended activities are based on age but these are a guide. We recommend that these ideas are used as inspiration, that ideas are undertaken with appropriate adult supervision, and that each adult uses their own discretion and knowledge of their children to consider the safety and suitability. Kidadl cannot accept liability for the execution of these ideas, and parental supervision is advised at all times, as safety is paramount. Anyone using the information provided by Kidadl does so at their own risk and we can not accept liability if things go wrong.

3) Because we are an educational resource, we have quotes and facts about a range of historical and modern figures. We do not endorse the actions of or rhetoric of all the people included in these collections, but we think they are important for growing minds to learn about under the guidance of parents or guardians.

google form TBD

- Preplanned tours

- Daytrips out of Moscow

- Themed tours

- Customized tours

- St. Petersburg

Moscow Metro

The Moscow Metro Tour is included in most guided tours’ itineraries. Opened in 1935, under Stalin’s regime, the metro was not only meant to solve transport problems, but also was hailed as “a people’s palace”. Every station you will see during your Moscow metro tour looks like a palace room. There are bright paintings, mosaics, stained glass, bronze statues… Our Moscow metro tour includes the most impressive stations best architects and designers worked at - Ploshchad Revolutsii, Mayakovskaya, Komsomolskaya, Kievskaya, Novoslobodskaya and some others.