- Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

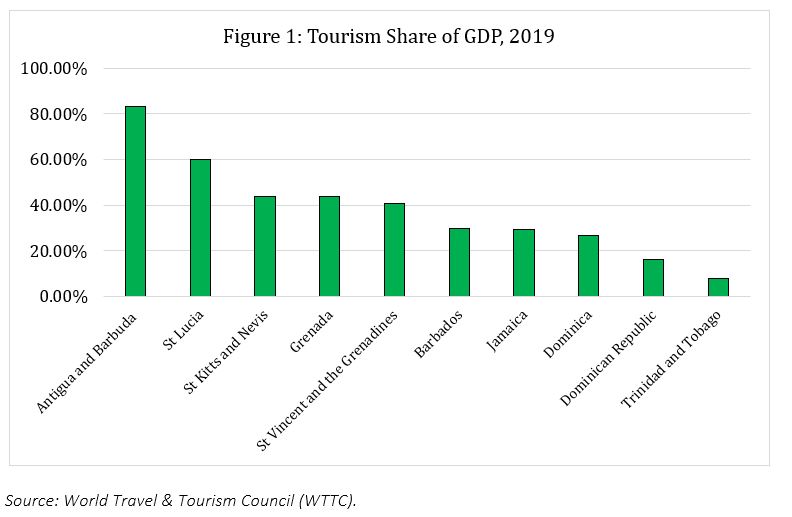

Most tourism-dependent economies in the Caribbean 2022

Caribbean countries or territories with the highest share of gdp generated by travel and tourism in 2022.

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

Report based on data from Oxford Economics, UNWTO, and national sources.

Other statistics on the topic

Accommodation

International visitor arrivals in Finland 2022, by country of origin

Leisure Travel

Visitor arrivals in Helsinki 2022, by country of origin

Number of outbound trips from Finland 2022, by country of destination

Number of arrivals in tourist accommodation in Finland 2012-2022

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Other statistics that may interest you

- Total tourism contribution to GDP in Cuba 2019-2021

- Total contribution of travel and tourism to GDP worldwide 2019-2033

- Domestic and outbound trips by residents in Spain 2010-2022

- International same-day tourist arrivals in Hungary 2009-2023

- International tourist arrivals in Hungary 2009-2023

- British tourism spending in Spain 2010-2022

- International visitor trip expenditure Australia FY 2010-2023

- International tourist expenditure in Latvia 2008-2021

- International tourism receipts in Norway 2019-2033

- Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by traveler origin

- Share of total tourism contribution to GDP in Latin American countries 2022

- Total tourism GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean 2019-2021

- Leading countries in the Americas in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2021

- Share of employment in travel and tourism in the Caribbean 2022, by country

- Inbound tourism spending in Montserrat 2010-2022

- Countries in the Americas with the highest inbound tourism receipts 2019-2022

- Total tourism contribution to GDP in Caribbean countries 2022

- Share of tourism in total employment in the Caribbean countries 2021

- Inbound tourism spending in the Caribbean 2019-2021

- COVID-19 impact on inbound tourism volume in Latin American subregions 2020-2021

- Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

- Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

- Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Change in number of visitors from Mexico to the U.S. 2018-2024

- Annual revenue of China Tourism Group Duty Free 2013-2023

- International tourist arrivals in Europe 2006-2023

- Foreign exchange earnings from tourism in India 2000-2022

- Number of international tourist arrivals in India 2010-2021

- International tourism receipts of India 2011-2022

- Travel and tourism direct contribution to GDP in Hungary 2017, by tourist type

- Inbound tourism spending in Sweden 2015-2020

- Forecasted tourism expenditure UK 2014-2025

- International tourist expenditure in Estonia 2012-2028

- International tourism spending in Croatia 2012-2028

- International tourism spending in Germany 2012-2028

- Opinions about sustainable tourism in Norway 2018

- Impact of tourism on the economy in Poland 2018

- Average trip expenditure of international visitors Australia FY 2010-2020

- Number of travelers in Greenland 2009-2020, by region

- Total tourism GDP in Latin American countries 2021

- French tourists in Spain 2010-2022

- Per capita daily spend of inbound tourists in the Community of Madrid 2010-2022

- Average per capita spend of inbound tourists in the Balearics 2010-2022

- Average length of stay by inbound tourists in the Balearic Islands 2010-2022

- International tourism volume in Catalonia 2000-2022

- Average international tourist spend per trip in Catalonia 2016-2022

- International tourism volume in Andalusia 2000-2022

- Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by destination

- Inbound tourism spending in St. Vincent & the Grenadines 2010-2022

Other statistics that may interest you Statistics on

About the industry

- Basic Statistic Total tourism contribution to GDP in Cuba 2019-2021

- Basic Statistic Total contribution of travel and tourism to GDP worldwide 2019-2033

- Premium Statistic Domestic and outbound trips by residents in Spain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic International same-day tourist arrivals in Hungary 2009-2023

- Basic Statistic International tourist arrivals in Hungary 2009-2023

- Premium Statistic British tourism spending in Spain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic International visitor trip expenditure Australia FY 2010-2023

- Premium Statistic International tourist expenditure in Latvia 2008-2021

- Basic Statistic International tourism receipts in Norway 2019-2033

- Basic Statistic Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by traveler origin

About the region

- Basic Statistic Share of total tourism contribution to GDP in Latin American countries 2022

- Basic Statistic Total tourism GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean 2019-2021

- Premium Statistic Leading countries in the Americas in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2021

- Basic Statistic Share of employment in travel and tourism in the Caribbean 2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism spending in Montserrat 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Countries in the Americas with the highest inbound tourism receipts 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Total tourism contribution to GDP in Caribbean countries 2022

- Basic Statistic Share of tourism in total employment in the Caribbean countries 2021

- Basic Statistic Inbound tourism spending in the Caribbean 2019-2021

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on inbound tourism volume in Latin American subregions 2020-2021

Selected statistics

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest outbound tourism expenditure worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Premium Statistic Change in number of visitors from Mexico to the U.S. 2018-2024

- Premium Statistic Annual revenue of China Tourism Group Duty Free 2013-2023

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals in Europe 2006-2023

- Basic Statistic Foreign exchange earnings from tourism in India 2000-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals in India 2010-2021

- Basic Statistic International tourism receipts of India 2011-2022

Other regions

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism direct contribution to GDP in Hungary 2017, by tourist type

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism spending in Sweden 2015-2020

- Basic Statistic Forecasted tourism expenditure UK 2014-2025

- Basic Statistic International tourist expenditure in Estonia 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic International tourism spending in Croatia 2012-2028

- Basic Statistic International tourism spending in Germany 2012-2028

- Premium Statistic Opinions about sustainable tourism in Norway 2018

- Premium Statistic Impact of tourism on the economy in Poland 2018

- Premium Statistic Average trip expenditure of international visitors Australia FY 2010-2020

- Premium Statistic Number of travelers in Greenland 2009-2020, by region

Related statistics

- Basic Statistic Total tourism GDP in Latin American countries 2021

- Premium Statistic French tourists in Spain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Per capita daily spend of inbound tourists in the Community of Madrid 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Average per capita spend of inbound tourists in the Balearics 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Average length of stay by inbound tourists in the Balearic Islands 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic International tourism volume in Catalonia 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Average international tourist spend per trip in Catalonia 2016-2022

- Premium Statistic International tourism volume in Andalusia 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism spending in St. Vincent & the Grenadines 2010-2022

Further related statistics

- Basic Statistic Contribution of China's travel and tourism industry to GDP 2014-2023

- Premium Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals APAC 2019, by country or region

- Basic Statistic Average price paid for a hotel room at home and away 2014, by country

- Basic Statistic Growth of inbound spending in the U.S. using foreign visa credit cards

- Premium Statistic BayWa's revenue by segment 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic MorphoSys' revenue 2006-2023

- Basic Statistic MorphoSys' research & development expenditure 2006-2023

- Premium Statistic Merck & Co - expenditure on research and development 2006-2023

- Basic Statistic Merck & Co total assets 2009-2023

- Basic Statistic Merck & Co cash dividends declared 2006-2023

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

- Contribution of China's travel and tourism industry to GDP 2014-2023

- Number of international tourist arrivals APAC 2019, by country or region

- Average price paid for a hotel room at home and away 2014, by country

- Growth of inbound spending in the U.S. using foreign visa credit cards

- BayWa's revenue by segment 2010-2022

- MorphoSys' revenue 2006-2023

- MorphoSys' research & development expenditure 2006-2023

- Merck & Co - expenditure on research and development 2006-2023

- Merck & Co total assets 2009-2023

- Merck & Co cash dividends declared 2006-2023

How the 'Tourism-Dependent' Caribbean Bounced Back and How Far the Region Could Still Go

Tourism has potential to drive nearly $100 billion in revenue, more than a million new jobs in caribbean by 2032.

By Dana Miller Hotel News Now

CORAL GABLES, Florida — The Caribbean region has emerged from the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic as a top tourism destination and trends point to continued growth in revenue and job creation.

A recent Caribbean impact report by the World Travel and Tourism Council forecasts potential revenue of $96.6 billion and the creation of 1.34 million new jobs by 2032, said Nicola Madden-Greig, president of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association and group director of marketing and sales at the Courtleigh Hospitality Group.

“This is major in terms of the potential for Caribbean tourism,” she said during the first day of the 14th annual Caribbean Hotel & Resort Investment Summit.

However, the region must overcome headwinds to get to that point. Challenges include the need for better air connectivity, investment in technology and relationships with the government, Madden-Greig said.

“The Caribbean was noted as the most tourism-dependent region in the world,” she added. “Probably it was thought that we would be the last one to rebound [from the COVID-19 pandemic]. Ladies and gentlemen, these are the figures … some of our destinations are in double-digit growth. For example, we have the U.S. Virgin Islands, St. Martin, Guadalupe [and] Martinique.”

Remington Hotels CEO Sloan Dean said consumers are not pulling back from spending more of their discretionary income on travel and experiences.

He said the Caribbean specifically is set up nicely to capture demand from travelers who want to blend business and leisure.

“Even myself, personally, I have worked from the Caribbean in the last 12 months for a week or two,” he said. “I think this dynamic of [remote work], blending business travel with personal … all those trends are here to stay.”

Not only is tourism on the rise in the region, interest both from investors and consumers is growing for resorts within the all-inclusive segment, speakers said.

During the “Views From the Boardroom — Round One” session, Playa Hotels & Resorts President and CEO Bruce Wardinksi said the appetite for all-inclusive resorts has been driving change in the hospitality industry for the past 10 years.

“I remember going to the NYU hotel conference probably about 10 years ago and sat on the very first all-inclusive panel. Before that, no one really talked about it. From our standpoint, there’s been a real shift in the types of properties, certainly with the brands coming into all-inclusive. That’s been the biggest change today,” he said.

Despite increasing competition in the all-inclusive space, Rob Smith, divisional vice president of full-service hotels at Aimbridge Hospitality, said finding partners on projects in the Caribbean has not been difficult.

“When you’re running a hotel, and that’s a big part of the economy on the island, local partners want to get involved because you’re bringing customers into the island. You seek those opportunities because the more you bring the local community into the operations of the hotel, the more successful you’re going to be, the more integrated you’re going to be with the island,” he said.

Carolyne Doyon, president and CEO in North America and the Caribbean at Club Med, echoed the importance of local partnerships.

“When we talk about local communities, local partners, we are also becoming an economic driver for the community. So not only for partnership and what they can bring for us, it’s also our responsibility of what we can bring to them. When they believe in the brand, when you’ve been there for a while and they trust you, they grow with you. You allow them to become more profitable and they can expand even more,” she said.

Local partners can also be integral in tackling some of the challenges facing tourism in the region.

Doyon said one issue she's particularly worried about this season is the widespread presence of sargassum. Sargassum is a genus of large brown seaweed that floats in oceans without ever attaching to its floors, and it often has a strong, unpleasant odor.

Caribbean officials have warned that this year's presence of sargassum will be historically strong, she said.

"I will tell you, we see it [near] our properties in the Dominican Republic and also in Mexico. It's a true threat. Today, there is a barrier of 5,000 miles of seaweed moving in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. If you look at weight, it's 13 million tons of seaweed," she said. "There's a cost of operation to remove the sargassum."

Photo of the Day

Data Point of the Day

"Panama is also becoming one of the big hubs for the Caribbean [in terms of air travel], not so much Miami. We're seeing that Miami is down by 50%, while Panama City is up 240%," said Nicola Madden-Greig, president of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association and group director of marketing and sales at The Courtleigh Hospitality Group.

Quote of the Day

"Tourism is the most important economic driver of the Caribbean economies. I think that we have such ample opportunity to make the Caribbean a more prosperous place. It's engagement, it's also responsibility .. and I think the time has come [for tourism operators] to ensure that we build resilience, that we work with our communities." —Karolin Troubetzkoy, executive director of marketing and operations at Anse Chastanet and Jade Mountain Resorts

Read more news on Hotel News Now.

See CoStar In Action

Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts

- First Online: 09 June 2022

Cite this chapter

- David Mc. Arthur Baker 3

289 Accesses

1 Citations

The Caribbean economy is highly dependent on the tourism industry and the protection of the natural and cultural attractions on which it depends is critical. To address this concern, this chapter provides a snapshot of the progress that has been made on sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean region. There is now more demand from the traveling public for industries to be environmentally friendly and in order to continue to use tourism as a means of economic advancement, sustainable practices must be adopted. The evidence suggests that there are great economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts of tourism in the Caribbean region that are both positive and negative. The actions of the accommodations sector are commendable but there is the need for all major stakeholders to better manage the negative impacts of tourism development. The Caribbean Tourism Organization has developed a policy framework which consists of guiding principles and integrated policies regarding sustainable tourism development, The Caribbean Sustainable Tourism Policy and Development Framework. A shock, such as COVID-19, can lead to economic collapse as communities heavily dependent on tourism have no capacity to respond to the loss of their primary revenue source. However, in order to strengthen the resilience of small island tourism development, the Caribbean region is transitioning toward community-driven solutions through innovation, employee training, upgrades, greater digitalization, and environmental sustainability.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdool, A. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of tourism: A comparative study of two Caribbean communities (Doctoral dissertation, Bournemouth University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/76947.pdf

Adrian, S. C. (2017). The impact of tourism on the global economic system. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 17 (1), 384–387.

Google Scholar

Albattat, A. (2017). Current issue in tourism: Diseases transformation as a potential risk for travelers. Global and Stochastic Analysis, 5 (7), 341–350.

Anderson-Fye, E. P. (2004). A “Coca-Cola” shape: Cultural change, body image, and eating disorders in San Andrés, Belize. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 561–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1068-4

Article Google Scholar

Aref, F., Gill, S. S., & Farshid, A. (2010). Tourism development in local communities: As a community development approach. Journal of American Science, 6 , 155–161.

Bakar, N. A., & Rosbi, S. C. (2020). Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science, 7 (4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.74.23

Baker, D. M. A. (2015). Tourism and the health effects of infectious diseases: Are there potential risks for tourists? International Journal Safety and Security of Tourism and Hospitality, 1 (12), 18. https://www.palermo.edu/Archivos_content/2015/economicas/journal-tourism/edicion12/03_Tourism_and_Infectous_Disease.pdf

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2018). Characteristic and intentions of cruise passengers to return to the Caribbean for land-based vacations. Journal Tourism – Revista de Turism, 26, 1–9.

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2021). Understanding residents’ opinions and support towards sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean: The case of Saint Kitts and Nevis. Coastal Business Journal, 18 (1), 1–29.

Becken, S. (2014). Water equity-contrasting tourism water use with that of the local community. Water Resources and Industry, 7 (8), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wri.2014.09.002

Becker, A. E. (2004). Television, disordered eating, and young women in Fiji: Negotiating body image and identity during rapid social change. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 533–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1067-5

Becker, A. E., Fay, K., Agnew-Blais, J., Guarnaccia, P. M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Development of a measure of “acculturation” for ethnic Fijians: Methodologic and conceptual considerations for application to eating disorders research. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47 (5), 754–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510382153

Behsudi, A. (2020, December). Wish you were here. Finance & Development . https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/12/pdf/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi.pdf

Bellos, V., Ziakopoulos, A., & Yannis, G. (2020). Investigation of the effect of tourism on road crashes. Journal of Transportation Safety & Security, 12 (6), 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2018.1545715

Bohdanowicz, P., Simanic, B., & Martinac, I. (2004, October 27–29). Sustainable hotels—Eco-certification according to EU Flower, Nordic Swan and the Polish Hotel Association. In Proceedings of the Regional Central and Eastern European Conference on Sustainable Building (SB04) . Warszawa, Poland.

Brewster, R., Sundermann, A., & Boles, C. (2020). Lessons learned for COVID-19 in the cruise ship industry. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 36 (9), 728–735.

Brida, J. G., & Zapata, S. (2010). Cruises tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, 1 (3), 205–226.

Britton, S. (1989). Tourism, dependency, and development: A mode of analysis. Europäische Hochschulschriften 10 (Fremdenverkehr), 11, 93–116.

Bushell, R., & McCool, S. F. (2007). Tourism as a tool for conservation and support of protected areas: Setting the agenda. In R. Bushell & P. F. J. Eagles (Eds.), Tourism and protected areas: Benefits beyond boundaries (pp. 12–26). CABI International.

Butt, N. (2007). The impact of cruise ship generated waste on home ports and ports of call: A case study of Southampton. Marine Policy, 31 (5), 591–598.

Cannonier, C., & Burke, M. G. (2019). The economic growth impact of tourism in small island developing states-evidence from the Caribbean. Tourism Economics, 25 (1), 85–108.

Caribbean Hotel Association. (2014). Advancing sustainable tourism, a regional sustainable tourism situation analysis: Caribbean . https://caribbeanhotelandtourism.com/

Castillo-Manzano, J. I., Castro-Nuño, M., López-Valpuesta, L., & Vassallo, F. V. (2020). An assessment of road traffic accidents in Spain: The role of tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23 (6), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1548581

Castro, C. (2004). Sustainable development: Mainstream and critical perspective. Organization and Environment, 17 (2), 195–225.

Chang, C., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12 (9), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093671

Chappell, K., & Frank, M. (2020). The most tourism-dependent region in the world braces for prolonged Coronavirus recovery . Reuters. https://skift.com/2020/04/20/the-most-tourism-dependent-region-in-the-world-braces-for-prolonged-coronavirus-recovery/

Charles, D. (2013). Sustainable tourism in the Caribbean: The role of the accommodations sector. International Journal of Green Economics, 7 (2), 148–161.

Cheng, T. L., & Conca-Cheng, A. M. (2020). The pandemics of racism and COVID-19: Danger and opportunity. Pediatrics, 146 (5), e2020024836. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-024836

Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27 (6), 1274–1289.

Cole, S. (2014). Tourism and water: From stakeholders to rights holders, and what tourism businesses need to do. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22 (1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.776062

Cook, C. L., Li, Y. J., Newell, S. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Neel, R. (2018). The world is a scary place: Individual differences in belief in a dangerous world predict specific intergroup prejudices. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21 (4), 584–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216670024

Croes, R., & Vanegas, M., Sr. (2008). Cointegration and causality between tourism and poverty reduction. Journal of Travel Research, 47 (1), 94–103.

Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism.” Sustainability, 8 , 475–507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

Darma, I. G. K. I. P., Dewi, M. I. K., & Kristina, N. M. R. (2020). Community movement of waste use to keep the image of tourism industry in GIANYAR. Journal of Indonesian Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 3 (1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.17509/jithor.v3i1.23439

Deloitte. (2012). Sustainability for consumer business operations: A story of growth . https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Consumer-Business/dttl_cb_Sustainability_Global%20CB%20POV.pdf

Farmer, P. (2006). AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame . University of California Press.

Findlater, A., & Bogoch, I. I. (2018). Human mobility and the global spread of infectious diseases: A focus on air travel. Trends in Parasitology, 34 (9), 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.004

Ghadban, S., Shames, M., & Abou Mayaleh, H. (2017). Trash crisis and solid waste management in Lebanon-analyzing hotels’ commitment and guests’ preferences. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality, 6 (3), 1000169. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-8807.1000171

Gössling, S., Peeters, P., Hall, C. M., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Lehmann, L. V., & Scott, D. (2012). Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tourism Management, 33 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.015

Greening, A. (2014). Understanding local perceptions and the role of historical context in ecotourism development: A case study of Saint Kitts (Master’s Thesis, Utah State University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hanafiah, M. H., Harun, M. F., & Jamaluddin, M. R. (2010). Bilateral trade and tourism demand. World Applied Sciences Journal, 10 , 110–114.

Harry-Hernández, S., Park, S. H., Mayer, K. H., Kreski, N., Goedel, W. C., Hambrick, H. R., Brooks, B., Guilamo-Ramos, V., & Duncan, D. T. (2019). Sex tourism, condomless anal intercourse, and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 30 (4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000018

Haukeland, J. V. (2011). Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of national park management in Norway. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19 (2), 133–153.

Haywood, M. K. (2020). A post COVID-19 future—Tourism re-imagined and re-enabled. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762120

Homans, C. G. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63 (6), 597–606.

Hoppe, T. (2018). “Spanish Flu”: When infectious disease names blur origins and stigmatize those infected. American Journal of Public Health, 108 (11), 1462–1464. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645

Hung, C. H., & Wu, M. T. (2017). The influence of tourism dependency on tourism impact and development support attitude. Asian Journal of Business and Management, 5, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.24203/ajbm.v5i2.4594

International Ecotourism Society. (2004). The triple bottom line of sustainable tourism . https://www.coursehero.com/file/81910666/s1pdf/

Jamal, T., & Stronza, A. (2009). Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (2), 169–189.

Johnson, D. (2002). Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: A reality check. Marine Policy, 26 (4), 261–270.

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). The environmental, social and economic impacts of cruising and corporate sustainability strategies. Athens Journal of Tourism, 3 (4), 273–285.

Jordan, E. J. (2014). Host community resident stress and coping with tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Jordan, E. J., Lesar, L., & Spenser, D. M. (2021). Clarifying the interrelations of residents’ perceived tourism-related stress, stressors, and impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 60 (1), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519888287

Jordan, E. J., & Vogt, C. A. (2017). Appraisal and coping responses to tourism development-related stress. Tourism Analysis, 22 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14828625279573

Kaseva, M. E., & Moirana, J. L. (2010). Problems of solid waste management on Mount Kilimanjaro: A challenge to tourism. Waste Management & Research, 28 (8), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X09337655

Klein, R. A. (2011). Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18 (1), 107–118.

Korstanje, M., & George, B. (2020). Demarketing overtourism, the role of educational interventions. In H. Séraphin & A. C. Yallop (Eds.), Overtourism and tourism education (pp. 81–95). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Laville-Wilson, D. P. (2017). The transformation of an agriculture-based economy to a tourism-based economy: Citizens’ perceived impacts of sustainable tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, South Dakota State University). South Dakota State University Open Prairie. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2262/

Li, Y., & Galea, S. (2020). Racism and the COVID-19 epidemic: Recommendations for health care workers. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (7), 956–957. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305698

Lubin, D. A., & Esty, D. C. (2010). The sustainability imperative. Harvard Business Review, 88 (5), 42–50.

Lyneham, S., & Facchini, L. (2019). Benevolent harm: Orphanages, voluntourism and child sexual exploitation in South-East Asia. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 574 . Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/benevolent_harm_orphanages_voluntourism_and_child_sexual_exploitation_in_south-east_asia.pdf

Mackenzie, S., & Goodnow, J. (2020). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing micro-adventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 43 (10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773984

MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tourism Management, 66 , 387–404.

Mansfield, B. (2009). Sustainability. In N. Castree, D. Demeriff, D. Liverman, & B. Rhoads (Eds.), A companion to environmental geography (pp. 37–49). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305722.ch3

Mansfeld, Y., & Pizam, A. (2006). Tourism, security and safety . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Asif, M., Zia ul Haq, M., & Rehman, H. (2019). The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 16 (19), 37–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193785

Mawby, R. I. (2017). Crime and tourism: What the available statistics do or do not tell us. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 7 (2), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2017.085292

Miller-Perrin, C., & Wurtele, S. K. (2017). Sex trafficking and the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Women & Therapy, 40 (1–2), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2016.1210963

Minooee, A., & Rickman, L. (1999). Infectious diseases on cruise ships. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 29 (4), 737–743.

Murphy, P., & Murphy, A. E. (2004). Strategic management for tourism communities. Channel View Publications.

Nofriya, N. (2018, August 7). Health and safety issues from tourism activities in Bukit Tinggi City, West Sumatra . 13th IEA SEA Meeting and ICPH—SDev. http://conference.fkm.unand.ac.id/index.php/ieasea13/IEA/paper/view/622

Ohlan R., (2017). The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Business Journal, 3 (1), 9–22.

Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16 (5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

Osland, G. E., Mackoy, R., & McCormick, M. (2017). Perceptions of personal risk in tourists’ destination choices: Nature tours in Mexico. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 8 (1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/ejthr-2017-0002

Person, B., Sy, F., Holton, K., Govert, B., Liang, A., Garza, B., Gould, D., Hickson, M., McDonald, M., Meijer, C., Smith, J., Veto, L., Williams, W., & Zauderer, L. (2004). Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal CDC, 10 (2), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030750

Peterson, R. R., Harrill, R., & Dipietro, R. B. (2017). Sustainability and resilience in Caribbean tourism economies: A critical inquiry. Tourism Analysis, 22 (3), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14955605216131

Petkova, A. T., Koteski, C., Jakovlev, Z., & Mitreva, E. (2012). Sustainability and competitiveness of tourism. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44 , 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.023

Qiu, R., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994

Quevedo-Gómez, M. C., Krumeich, A., Abadía-Barrero, C. E., & Van den Borne, H. W. (2020). Social inequalities, sexual tourism and HIV in Cartagena, Colombia: An ethnographic study. BMC Public Health, 20 (1208), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09179-2

Ram, Y. (2021). Me too and tourism: A systematic review. Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1664423

Ramesh, D. (2002). The economic contribution of tourism in Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (3), 862–865.

Richter, L. K. (2003). International tourism and its global public health consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 41 (4), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503041004002

Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30 (3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001

Robinson, M. (1999). Collaboration and cultural consent: Refocusing sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7 (3–4), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589908667345

Rosselló, J., Santana-Gallego, M., & Awan, W. (2017). Infectious disease risk and international tourism demand. Health Policy and Planning, 32 (4), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw177

Ryan, C., & Kinder, R. (1996). Sex, tourism and sex tourism: Fulfilling similar needs? Tourism Management, 17 (7), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00068-4

Schwartz, K. L., & Morris, S. K. (2018). Travel and the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 20 (9), Article 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0634-9

Sheller, M. (2004). Natural hedonism: The invention of Caribbean islands as tropical playgrounds. In S. Courtman (Ed.), Beyond the blood, the beach, and the banana : New perspectives in Caribbean studies (pp. 170–185). Ian Randle.

Sönmez, S., Wiitala, J., & Apostolopoulos, Y. (2019). How complex travel, tourism, and transportation networks influence infectious disease movement in a borderless world. In D. J. Timothy (Ed.), Handbook of globalization and tourism (pp. 76–88). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786431295.00015

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. (2014). Cruise lines: Sustainability accounting standards . http://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/SV0205_Cruise_ProvisionalStandard.pdf

Telfer, D. (2002). The evolution of tourism and development theory. In R. Sharpley & D. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and development: Concepts and issues (pp. 35–78). Channel View.

The Caribbean Tourism Organization [CTO]. (2020). Caribbean sustainable tourism policy and development framework . https://caricom.org/documents/10910-cbbnsustainabletourismpolicyframework.pdf

Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2015). Strengthening community-based tourism in a new resource-based island nation: Why and how? Tourism Management, 48 , 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.12.013

Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27 , 493–504.

UNCTAD. (2020). Coronavirus will cost global tourism at least $1.2 trillion . United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://unctad.org/news/coronavirus-will-cost-global-tourism-least-12-trillion

UNWTO. (2001). Tourism highlights 2001. World Tourism Organization. Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284406845

UNWTO. (2019). United Nations World Tourism Report 2019 . Available at: https://www.eunwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152 . Accessed 24 August 2020.

Walker, L., & Page, S. J. (2004). The contribution of tourists and visitors to road traffic accidents: A preliminary analysis of trends and issues for central Scotland. Current Issues in Tourism, 7 (3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667980

Wallen, B. (2020, November 30). Why some countries are opening back up to tourism during a pandemic. National Geographic . https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/are-economics-driving-countries-to-reopen-to-tourists-coronavirus

Waterman, T. (2009). Assessing public attitudes and behavior toward tourism development in Barbados: Socio-economic and environmental implications . Central Bank of Barbados.

Wilks, J., Stephen, J., & Moore, F. (2013). Managing tourist health and safety in the new millennium . Routledge.

World Conservation Union. (1996, October 13–23). Resolutions and recommendations [Meeting]. World Conservation Congress, Montreal, Canada. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/WCC-1st-002.pdf

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2019). Economic impact reports . https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2020). 100 million jobs recovery plan: Final Proposal (G20 2020 Saudi Arabia Summit). https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2020/100%20Million%20Jobs%20Recovery%20Plan.pdf?ver=2021-02-25-183014-057

Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear.’ Tourism Management, 83, 104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104261

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hospitality & Tourism Management, College of Business, Tennessee State University, Nashville, TN, USA

David Mc. Arthur Baker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Mc. Arthur Baker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Jack C. Massey College of Business, Belmont University, Nashville, TN, USA

Colin Cannonier

Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY, USA

Monica Galloway Burke

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Baker, D.M.A. (2022). Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts. In: Cannonier, C., Galloway Burke, M. (eds) Contemporary Issues Within Caribbean Economies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Published : 09 June 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98864-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98865-4

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Show search

Perspectives

The Caribbean Needs Tourism, and Tourism Needs Healthy Coral Reefs

AI and social media are helping quantify the economic value of coral reefs

January 14, 2019

By Luis A. Solórzano, Former Executive Director, Caribbean Division

The Caribbean region is more dependent on tourism than any other region in the world—the sector accounts for over 15 percent of GDP and 13 percent of jobs in the region. And almost all visitors to the Caribbean take part in some activity that relates to coral reefs—either directly, like snorkeling and scuba diving, or indirectly, like enjoying sandy beaches, eating fresh seafood and swimming in crystal waters. That means the health of the Caribbean’s tourism industry—and thus the whole regional economy—is dependent on the health of its coral reefs.

But just how much value do reefs produce? After all, “what gets measured gets managed and improved.” The Nature Conservancy (TNC) recently released the results of a study that focused on reef-adjacent activities and the value they generate for the tourism industry, island governments and Caribbean communities. This study, which builds on an earlier body of globally focused research produced by TNC, found that reef-adjacent activities alone generate an estimated $5.7 billion per year in the Caribbean from roughly 7.4 million visitors. When combined with reef-dependent tourism activities, they generate $7.9 billion total from roughly 11 million visitors.

In other words, a major draw for people traveling to the Caribbean are activities related to coral reef ecosystems, and both the tourism industry and other aspects of the local economies depend on healthy coral reefs to keep this relationship afloat. This evidence offers a pivotal opportunity for advancing coral conservation initiatives not only in the Caribbean but around the world, as it can catalyze both the tourism industry and local governments and communities to invest in protecting and restoring coral reefs for the benefit of economies and incomes.

We now know that these natural wonders are responsible for generating billions of dollars, sustaining livelihoods and anchoring economies in the Caribbean as well as other tropical destinations across the globe . And that should translate into a major incentive to conserve them.

We now know that coral reefs generate billions of dollars ... and that should translate into an incentive to conserve them.

Equally remarkable is the method by which this information came to light. The study, led by The Nature Conservancy, with support from JetBlue, the World Travel & Tourism Council and Microsoft, merged contemporary culture with modern science by using artificial intelligence to analyze social media content. Social media platforms provide valuable insight into how the general public spends their recreational time and, importantly, their discretionary income. Machine-learning algorithms, a type of artificial intelligence, allow computers to autonomously make determinations based on learned information.

Using algorithms developed by the Microsoft Cognitive Services Computer Vision API, the study analyzed over 86,000 social images and nearly 6.7 million social text posts for visual and language identifiers that indicated reef-adjacent activities, such as white beaches, turquoise waters, reef fish and sea turtles, which were then selected according to geotags indicating proximity to a reef of 30 kilometers or less. The social media metrics derived using artificial intelligence were integrated with traditionally sourced data, like visitor center surveys, tourism business sales figures and government-reported economic data, to produce estimated reef-adjacent economic values for 32 Caribbean countries and territories.

The study produced vital information about the connection of specific islands and the entire region to reef-related tourism. Key findings include:

- The Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico benefit from visitor expenditure of over $1 billion per year directly linked to coral reefs.

- The Bahamas, Cayman Islands and Puerto Rico receive the equivalent of over 1 million visitor trips per year directly linked to coral reefs.

- The top 10 percent highest-value reefs generate over $5.7 million and 7,000 visitors per square kilometer per year. These reefs are scattered in almost every country and territory with the exception of Haiti. Barbados, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands have a large proportion of high-value reefs, each with an average expenditure value of over $3 million per square kilometer per year.

- The countries most dependent on reef-adjacent tourism include many small developing island states like Anguilla, Antigua & Barbuda, Bermuda, St. Kitts & Nevis and St. Martin, where there may be relatively few options for earning income outside of reef-associated tourism.

- Only 35 percent of reefs throughout the Caribbean are not used by the tourism sector, indicating that there are scarce options for movement of reef-associated activities to new areas. Most of those not used for tourism are in remote locations.

The Caribbean needs tourism, and tourism needs healthy coral reefs—and the findings from this study, which shine a spotlight on the pervasive dependence on reefs in almost every corner of the region, suggest that this would hold true for any region in the world that has similar reliance on its natural environments to sustain tourism, livelihoods and economies.

In a world where coral reefs are at grave risk due to climate change, overfishing, pollution and other threats, the tourism sector and the people that depend on it grow more vulnerable. There is urgency, and armed with the information on the economic value of coral reefs revealed in this study, the tourism industry, and governments and communities in tourism-dependent areas, are motivated to invest in the protection and restoration of these essential ecosystems. Understanding this equation and its significance makes us smarter in the global fight to protect and restore nature.

Download the Study

Executive Summary

Executive Summary: Estimating Reef-Adjacent Tourism Value in the Caribbean

Full Report

Full Report: Estimating Reef-Adjacent Tourism Value in the Caribbean

Further reading

From Constellation to Coral Reefs

Taking to the sky—even outer space—with revolutionary technologies to protect habitats beneath the sea.

Insuring Nature to Ensure a Resilient Future

Integrated solutions linking nature and insurance can help to reduce risk and build resilience to the impacts of climate change.

How Tourism Can Be Good for Coral Reefs

Data highlights opportunities for the tourism industry to support better conservation outcomes

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.

Tourism’s Recovery in the Caribbean

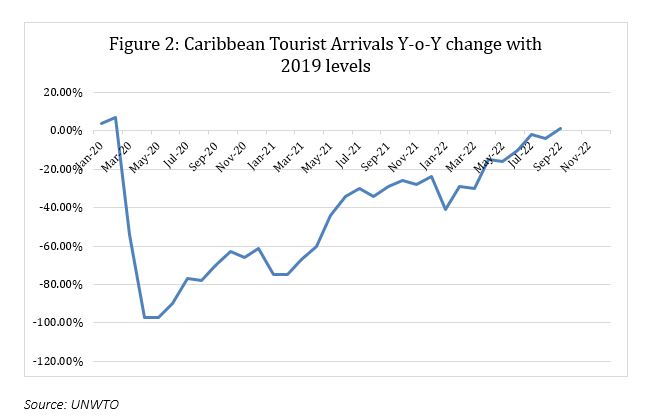

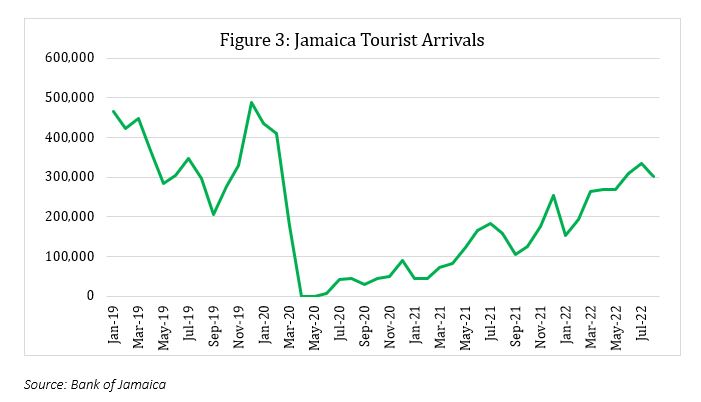

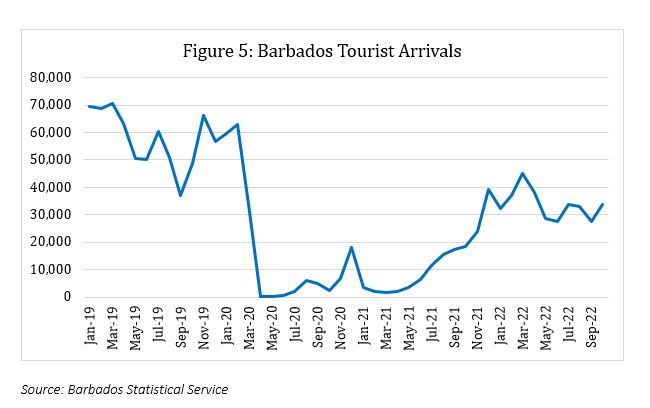

As travelers in the U.S. looked for a pandemic getaway this past holiday season, the Caribbean was a popular destination in mind. Meanwhile, many Caribbean countries saw the season as a chance to make up for lost time and recover much-needed revenue after the pandemic dealt a loss to tourism and their once-thriving economy. Most countries in the Caribbean are incredibly reliant on tourism, which in 2019 accounted for up to 26 percent of total GDP and up to 80 percent of employment in some countries. Even despite major hurricanes that frequently disrupt travel to these islands, the region has economically recovered every time due to tourist demand. However, the pandemic has given the region a new challenge – Caribbean countries cannot rely on tourist demand alone as many people are still reluctant to travel. Governments had hoped that in 2021, widespread coronavirus vaccines and a safe policy for visitors would prevent further spread and make up for lost revenue in the region. While cruises and tourists have slowly returned to the Caribbean, the Omicron surge during the lucrative holiday season hampered the return to form that many had hoped.

The Dominican Republic has tried to adapt by attracting U.S tourists with lower thresholds to entry compared to other Caribbean countries. In 2021, their government’s unorthodox approach emphasized that tourist-facing workers be vaccinated as opposed to visitors, who do not need to be vaccinated nor obtain a negative test. In fact, many guests even chose to not wear masks in the hotels. Despite the burden, this placed on Dominican citizens, the policy brought a major boost to the economy and returned the country to pre-pandemic levels of growth. While the policy was an economic success, Dominicans have seen repercussions due to their lenient policy on visitor vaccinations. Omicron’s untimely surge during the holiday season caused a jump in the island’s number of COVID cases in late December, reaching a peak of about 7,000 per day on January 12. In response to the high volume of cases and overloaded hospitals, healthcare workers are pushing for vaccination requirements for visitors, arguing that the current policy is “discriminatory.” Although the Dominican Republic’s COVID numbers have since declined, the Omicron surge serves as a warning about the dangers of opening up too soon.

Many countries had to balance putting their citizens’ safety over their own economic health and market share of tourism – losing out on visitors now can mean fewer people will consider visiting in the future– so countries need to adopt different policies for welcoming visitors back. One trend for countries like Mexico and the Bahamas saw a rise in tourists due to their proximity to the United States and relative popularity compared to other destinations, but have also witnessed a parallel rise in cases. Some Caribbean governments have tried to make their islands more appealing to tourists by investing heavily in new hotels, airport terminals, and initiatives for remote-work vacations, hoping visitors will see the islands as “pandemic escapes” in the coming years. But others in the region, like Dominica and the Cayman Islands, are less known and less accessible islands. These islands continue to struggle despite having new connections to U.S airports, as tourists prefer more familiar or safer destinations with greater CO. Many of these countries don’t expect a return to pre-pandemic levels of tourism until 2023 at the earliest.

Policies alone will not allow the region to fully recover. Although U.S. travelers are coming to the islands, visitors from Canada, Europe, and Asia have yet to arrive due to steeper reluctance to travel long distances for a vacation, continued travel restrictions, and steep re-entry restrictions upon returning home, making it hard to plan a vacation to the islands. Additionally, many smaller island nations rely on revenue from cruises, an industry hit hard by the pandemic as cruise companies like Royal Caribbean continue to cancel voyages due to pandemic concerns. Cruises have historically aided in the region’s economic recovery after nearly every hurricane season , bringing in flocks of tourists. But cruise lines have canceled voyages due to COVID outbreaks and generally struggled to recover from the pandemic. Without a robust cruise industry, Caribbean islands are at a loss on how to compensate for this huge loss of income.

One case that highlights the significance of the Caribbean’s current lack of tourists in Cuba. Prior to the pandemic, Cuba was just beginning to open up tourism to the United States, but after flight reductions, heavy entry restrictions for COVID, and economic sanctions, Cuba’s tourism industry completely shut down. As a country increasingly reliant on tourism in recent years, the loss led to an economic crisis like many others in the region, further exacerbated by U.S. sanctions. Instead of focusing on revitalizing its economy first, Cuba focused on pandemic safety and launched an effort to fully vaccinate its citizens. Cuba became one of the fastest countries to vaccinate its citizens, and it waited until a healthy majority was vaccinated before opening up to visitors this last November, one of the last Caribbean countries to do so. The country had hoped that pandemic safety would be a draw compared to many other countries in the region. Though the effects of this policy were not immediate ( projecting a 92 percent loss in tourism ), many Cubans are hopeful that the continued, gradual reopening of the world will bring tourists back to the island in the coming years to support its recovery. Others in the region, like Trinidad, have followed Cuba’s strategy and opened their borders around the same time in late 2021. However, Cuba’s imposed sanctions combined with slow travel pushed them to take the safest reopening approach in the region. Cuba bet on pandemic safety as a tourist draw, but slow travel growth is hindering their recovery strategy and prolonging economic hardships.

Each Caribbean country has taken a unique approach to economic recovery best suited to their situation – but, because of a continued lag in tourism from the pandemic, all of the islands are itching for tourists to return. Despite the pandemic’s setbacks, Jamaica’s tourism minister stated that many countries are “anxious for normality” having witnessed other countries in the region open up. The Caribbean has stood out for its impressive recovery, faster than any other region in the world since 2020. Many countries are optimistic about their recovery or have already returned to pre-pandemic levels of visitors. While these countries are doing the best they can to attract tourists, it is vital that the tourism industry completely recovers in order for the Caribbean to rebound in a post-pandemic world.

MOST RECENT ARTICLE

The Canadian government recently signed an agreement to transfer full control over the northernmost territory of Nunavut to the territory’s Inuit-dominated residents. This is a huge milestone in the movement for indigenous rights, and autonomy for the region will also bring more sustainable resource assessment and the protection of biodiversity. It could also be a stepping stone for increased indigenous autonomy and biodiversity across the Americas.

“There has been a troubling resurgence of antisemitic attitudes across Europe, especially in the Scandinavian countries. Given Scandinavia’s, and the continent as a whole, complex and painful history with its Jewish communities, the latest developments in the Middle East have sparked a wave of hostility in various areas.”

- S&P Dow Jones Indices

- S&P Global Market Intelligence

- S&P Global Mobility

- S&P Global Commodity Insights

- S&P Global Ratings

- S&P Global Sustainable1

- *BRC Ratings – S&P Global

- India-CRISIL

- Taiwan Ratings

- S&P Capital IQ Pro

- Ratings360®

Entity & Insights

Caribbean And North Atlantic Tourism-Dependent Sovereign 2022 Outlook: Rating Risks Are More Balanced As Economies Continue To Turn Around

Islamic Finance 2024-2025: Resilient Growth Anticipated Despite Missed Opportunities

Private Markets Monthly, April 2024: Private Credit Is A Growing Segment Of Nonbank Finance

CreditWeek: How Could Megatrends Influence Credit Materiality?

Instant Insights: Key Takeaways From Our Research

- 27 Jan, 2022 | 19:29

- Sector Governments Sovereigns

We Expect The Economic Rebound Will Be Quicker In The Caribbean Than In Other Tourism-Dependent Regions

Rebounding economies will support improved deficits and debt metrics, from weak levels, over the next two years, supportive institutional structures, or the lack thereof, will remain a determining factor in ratings and resiliency, government management of the economic and fiscal recovery is an important component of our rating outlook triggers, related research.

This report does not constitute a rating action.

Key Takeaways

- After taking multiple negative rating actions on sovereigns across the tourism-dependent Caribbean over the past two years, we expect ratings will stabilize at lower levels over the next 12 months as tourism accelerates and the region moves beyond the pandemic-induced trough.

- A GDP recovery will lessen the need for spending support measures and boost revenue collection, improving deficits and weak debt metrics, while external accounts will likely weaken.

- Rating resiliency will continue to depend on the degree to which institutional support structures are in place, and the way in which the sovereigns manage recovered revenues from a rebounding tourism sector.

S&P Global Ratings anticipates that solid economic growth will contribute to more stable ratings over the next year. Since March 1, 2020, we have taken nine negative rating actions on the tourism-dependent sovereigns in the region, including negative outlook revisions and downgrades. The main drivers of these actions were deteriorating per capita incomes; significantly higher deficits and debt levels; and, in some cases, institutional deterioration.

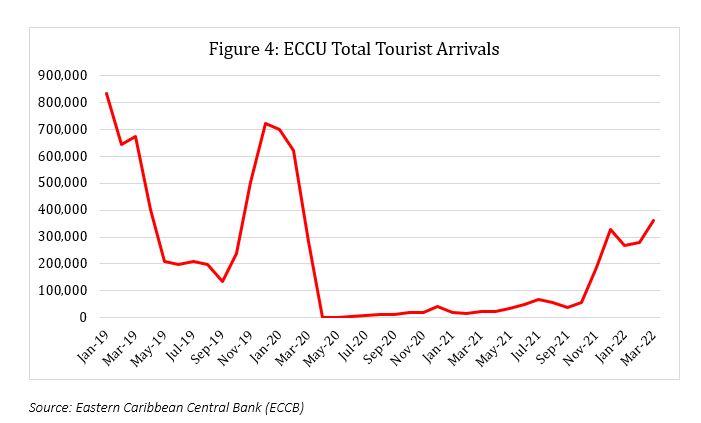

In our view, despite the challenges associated with new COVID-19 variants, the worst of the economic impact of the pandemic has passed in the region, and tourism has begun to rebound at a faster pace than in other areas of the world. The recent rapid spread of the omicron variant highlights the inherent uncertainties of the pandemic but also the importance and benefits of vaccines. While the risk of new, more severe variants displacing omicron and evading existing immunity cannot be ruled out, our base case assumes that existing vaccines can continue to provide significant protection against severe illness. At the same time, the economic impact of the pandemic on the region has waned and economies are proving more adaptable, as many governments, businesses, and households are tailoring policies to limit the adverse economic impact of recurring COVID-19 waves. Although year-end data are not yet available, the World Travel & Tourism Council reports that it expects travel and tourism increased by 47.3% in 2021 in the Caribbean, versus 30.7% for the global economy. At the same time, the United Nations' World Tourism Organization's latest global data as of December 2021 show that the Caribbean had the lowest drop in tourist arrivals year to date compared with any other region in the world, and was more than 50% stronger than overall global arrival statistics (table 1). The region's economy has benefited from greater traveler confidence, more relaxed restrictions compared with other tourism-dependent regions, and relatively rapid vaccination. Proximity to the U.S., where travel rebounded more quickly than in other developed countries, and dependence on U.S. tourists, has also aided the recovery. In addition, constitutional association with the Kingdom of the Netherlands or the U.K. facilitated strong and early vaccine access, as well as fiscal support, in some cases, which helped accelerate growth in some sovereigns in 2021.

Looking ahead, although the recovery will be uneven across countries, we expect that the region as a whole will continue to benefit from its proximity to and dependence on the U.S., where we expect strong economic growth in 2022 of 3.9%. Notwithstanding potential downside risks related to new COVID-19 variants and the impact of their spread on travel, we expect the weighted-average real GDP growth rates for the sovereigns listed in chart 1 will be 5.9% in 2022. Sovereigns' vaccination rates, COVID-19 transmission and restrictions, reliance on U.S. tourism, and degree of economic contraction in 2020 will likely contribute to the speed of recovery in 2022.

Following significant deterioration in deficits in 2020, and still-weak levels in 2021, governments across the region will benefit from recovered revenues collected from a rebounding tourism sector, both directly and indirectly, as well as economies that are less subject to containment measures. At the same time, those governments that have implemented income support measures will gradually decrease their spending as the need for such support winds down. All eight tourism-dependent Caribbean sovereigns discussed in this article implemented some sort of income support, wage subsidy, or transfer program during the pandemic. The scope of the programs largely depended on the government's fiscal flexibility and the availability of concessionary funding. Aruba and Curacao, for example, which are both constituent members of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, were able to provide payroll subsidy programs whereby employers were compensated, in some cases for 80% of wage costs. This was possible, in part, due to the 0% interest loans the Netherlands provided to these governments. On the other hand, countries like Jamaica benefited from a surge in remittances, which provided an income cushion to some people. In 2020, remittances in Jamaica represented 21% of GDP, compared with 16% in 2019.

The sizable deficits in the region have led to significant increases in government debt, which we expect will take many years to reverse. Those sovereigns that had greater fiscal flexibility to provide stronger economic packages to their populations, and at the same time were more severely affected by the downturn in tourism and activity restrictions, saw larger increases in their debt burdens. Nevertheless, because these sovereigns also have generally higher credit ratings than those with less fiscal flexibility, and were able to benefit from concessionary, or zero-cost funding and low interest rates, the impact of this increase on the cost of debt is more limited. Looking ahead, the pace of reversing this increase will not only depend on decisions made by governments regarding countercyclical spending as the recovery takes hold, but also on the pace of economic growth.

Although the effect of the pandemic on external accounts in the region has been much more limited than originally anticipated, we expect external balances will weaken slightly over the forecast horizon. During the pandemic, the high import content of the tourism sector meant that imports shrunk considerably as tourism contracted, which significantly offset the reduction in exports, along with lower energy prices during much of 2020 and early 2021. At the same time, the external support many of these sovereigns received through concessional funding or remittances provided a boost to central banks' foreign exchange reserves. As travelers return, the import content of tourism offerings will translate into an increase in imports, while higher energy prices will also negatively affect these sovereigns' balance of payments because all are energy importers.

Status as a Kingdom of the Netherlands member, British overseas territory, multilateral lending institution program participant, or a sovereign that lacks substantial external support structures, will continue to determine vaccine access, level of concessional funding, and ability to provide countercyclical support. In turn, these factors will affect the speed of economic recovery and fiscal and debt sustainability. Of the eight English- or Dutch-speaking tourism-dependent sovereigns in the region rated by S&P Global Ratings, three are British overseas territories, two are constituent members of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and two are either recent graduates, or current program participants of International Monetary Fund (IMF)-supported programs. As constituent members of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Aruba and Curacao benefited from strong and early access to vaccines starting in February 2021, for example, which aided their ability to re-open their economies and the pace of tourism recovery in 2021. Likewise, British overseas territories also received vaccine support from the U.K., which accelerated their growth in 2021. These sovereigns now have higher vaccination rates than others in the region, and even some of the tourist source markets, lowering the risk of future movement restrictions.

We expect most of those sovereigns that were able to access significant grants or concessionary, low-cost funding during the pandemic will continue to receive support in 2022, which will limit the impact of higher debt burdens on their creditworthiness. Both Curacao and Aruba, for example, have benefited from mutual aid and assistance from the Netherlands since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. The Netherlands has provided liquidity support in the form of zero-interest bullet loans for more than $1 billion to the two countries, as well as offering medical support and food aid. This is in addition to the arrangement that Curacao has with the Netherlands, predating the pandemic, under which the Netherlands subscribes to Curacao's debt issuances at the same interest rate at which the Netherlands issues debt.

Those sovereigns that have strong relationships with multilateral funding institutions will also likely benefit from continued access to ample concessionary funding over the next year. For example, Barbados entered into an extended fund facility program with the IMF starting in October 2018, and has since received $425 million in financing over six successful reviews in the program, in addition to about $750 million from the Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank, Caribbean Development Bank, and the Development Bank of Latin America. In addition, as a somewhat recent graduate of a substantial IMF-supported program, and shortly after the onset of the pandemic in 2020, Jamaica obtained $520 million via the IMF's rapid financing instruments (RFI), as a precaution to support balance-of-payments needs. Unlike previous IMF support, the RFI funds are granted without policy conditions. Although we understand that it could be reallocated to budgetary support, to date, the money remains with the Bank of Jamaica to support the country's foreign exchange reserves.

A key issue for our rating outlook triggers in the region over the next two years will be how these sovereigns manage the economic recovery, including how they use and manage the revenues collected from a rebounding tourism sector, which will have implications for deficits and debt sustainability. Following multiple negative rating actions over the past two years, seven out of eight sovereign ratings in the region now have stable outlooks, while one has a negative outlook (table 3). Nevertheless, a common thread in almost all of the ratings' downside and upside scenarios is the ability, or lack thereof, of the respective government to narrow deficits and contribute to a stabilized or lower debt burden, following two years of sizable deficits caused by the pandemic. Although this will, in part, depend on the evolution of the pandemic and the pace of the economic recovery, government fiscal policy and expenditure management will also play a crucial role.

- Global Sovereign Rating Trends 2022: Despite Stabilization, The Pandemic Threatens The Recovery , Jan. 27, 2022

- Global Credit Outlook 2022: Aftershocks, Future Shocks, And Transitions , Nov. 30, 2021

- Barbados , Nov. 25, 2021

- Research Update: The Commonwealth of The Bahamas Ratings Lowered to ‘B+’ From ‘BB-‘ On Continued Deficits, High Debt , Nov. 12, 2021

- Research Update: Jamacia Outlook Revised To Stable From Negative; ‘B+’ Long-Term And ‘B’ Short-Term Ratings Affirmed , Oct. 4, 2021

- Research Update: Turks And Caicos Islands ‘BBB+/A-2’ Sovereign Credit Ratings Affirmed; Outlook Remains Stable , May 26, 2021

- Bermuda , April 28, 2021

- Research Update: Montserrat Sovereign Credit Ratings Affirmed At ‘BBB-/A-3’; Outlook Stable , April 13, 2021

- Research Update: Aruba Long-Term Ratings Lowered to ‘BBB’ from ‘BBB+’ On Weaker Economy And Higher Debt; Outlook Stable , March 15, 2021

- Curacao , Feb. 16, 2021

No content (including ratings, credit-related analyses and data, valuations, model, software, or other application or output therefrom) or any part thereof (Content) may be modified, reverse engineered, reproduced, or distributed in any form by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC or its affiliates (collectively, S&P). The Content shall not be used for any unlawful or unauthorized purposes. S&P and any third-party providers, as well as their directors, officers, shareholders, employees, or agents (collectively S&P Parties) do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, or availability of the Content. S&P Parties are not responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, for the results obtained from the use of the Content, or for the security or maintenance of any data input by the user. The Content is provided on an “as is” basis. S&P PARTIES DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR USE, FREEDOM FROM BUGS, SOFTWARE ERRORS OR DEFECTS, THAT THE CONTENT’S FUNCTIONING WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED, OR THAT THE CONTENT WILL OPERATE WITH ANY SOFTWARE OR HARDWARE CONFIGURATION. In no event shall S&P Parties be liable to any party for any direct, indirect, incidental, exemplary, compensatory, punitive, special or consequential damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including, without limitation, lost income or lost profits and opportunity costs or losses caused by negligence) in connection with any use of the Content even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

Credit-related and other analyses, including ratings, and statements in the Content are statements of opinion as of the date they are expressed and not statements of fact. S&P’s opinions, analyses, and rating acknowledgment decisions (described below) are not recommendations to purchase, hold, or sell any securities or to make any investment decisions, and do not address the suitability of any security. S&P assumes no obligation to update the Content following publication in any form or format. The Content should not be relied on and is not a substitute for the skill, judgment, and experience of the user, its management, employees, advisors, and/or clients when making investment and other business decisions. S&P does not act as a fiduciary or an investment advisor except where registered as such. While S&P has obtained information from sources it believes to be reliable, S&P does not perform an audit and undertakes no duty of due diligence or independent verification of any information it receives. Rating-related publications may be published for a variety of reasons that are not necessarily dependent on action by rating committees, including, but not limited to, the publication of a periodic update on a credit rating and related analyses.

To the extent that regulatory authorities allow a rating agency to acknowledge in one jurisdiction a rating issued in another jurisdiction for certain regulatory purposes, S&P reserves the right to assign, withdraw, or suspend such acknowledgement at any time and in its sole discretion. S&P Parties disclaim any duty whatsoever arising out of the assignment, withdrawal, or suspension of an acknowledgment as well as any liability for any damage alleged to have been suffered on account thereof.

S&P keeps certain activities of its business units separate from each other in order to preserve the independence and objectivity of their respective activities. As a result, certain business units of S&P may have information that is not available to other S&P business units. S&P has established policies and procedures to maintain the confidentiality of certain nonpublic information received in connection with each analytical process.

S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors. S&P reserves the right to disseminate its opinions and analyses. S&P's public ratings and analyses are made available on its Web sites, www.spglobal.com/ratings (free of charge), and www.ratingsdirect.com (subscription), and may be distributed through other means, including via S&P publications and third-party redistributors. Additional information about our ratings fees is available at www.spglobal.com/usratingsfees .

- Governments Sovereigns

Create a free account to unlock the article.

Gain access to exclusive research, events and more.

Already have an account? Sign in

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, post-independence challenges for caribbean tourism development: a solution-driven approach through agenda 2030.

Tourism Review

ISSN : 1660-5373

Article publication date: 10 February 2023

Issue publication date: 7 April 2023

This paper aims to provide a comparative analysis of sustainable tourism development across the Anglophone Caribbean region from the post-independence period of 1962 to the 2020s. The perspective explores the implications of insularity, tourism investment and the pace of technology adoption on the potential realisation of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the islands of Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago and the Eastern Caribbean States.

Design/methodology/approach

The viewpoint uses secondary data from grey literature such as government policy documents, academic literature, newspapers and consultancy reports to explore the central themes and provide a conceptual framework for the paper.

The findings reveal that Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are nearer to the light-green single-sector approach to sustainable tourism development. The overarching findings reveal that the region’s heavy focus on economic priorities results in less attention to competitiveness challenges such as environmental management, social equity and technological innovations.

Research limitations/implications

The research presents a comprehensive overview of the tourism development trajectory of other tourism-dependent island-states. The research offers lessons and cross-learning opportunities that may be useful to decision-makers within SIDS. The main limitation is that the findings may only be transferable and generalised to the extent that other jurisdictions bear similar macroeconomic governance structures and cultural characteristics to Caribbean SIDS.

Practical implications

This paper provides a meaningful discussion and contributes to the body of knowledge on the history of Caribbean tourism development, the challenges and future potential of sustainability and lends itself to opportunities for future research in the Caribbean and other SIDS.

Social implications

The study outlines the social implications for inclusive, responsible and sustainable tourism that can potentially take Caribbean SIDS from slow growth to efficiency in developing the tourism product, including the technological environment. This can reduce inequalities, contribute to socio-economic development and improve the region’s human capital.

Originality/value

This paper provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Caribbean tourism development specific to Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean States. No previous work has been done to compare tourism development within this grouping. Hence, this paper is essential in informing decision-makers and providing the foundation for continuing research in this area.

这篇观点性论文对英语加勒比地区从1962年独立后到本世纪20年代的可持续旅游发展进行了比较分析。该研究前瞻性探讨了牙买加、巴巴多斯、特立尼达和多巴哥以及东加勒比国家的保守性、旅游投资和技术采用速度对潜在实现可持续发展目标的启示。

该研究利用灰色文献中的二手数据, 如政府政策文件、学术文献、报纸和咨询报告, 进行中心主题探索, 并为论文提供概念性框架。

研究结果显示, 加勒比小岛屿发展中国家(SIDS)更接近于以轻绿的单一部门方式实现可持续旅游发展。总体研究结果显示, 该地区过于关注经济优先事项, 导致对环境管理、社会公平和技术创新等竞争力挑战的关注较少。

本研究全面展现了一些依赖旅游发展的岛屿国家的旅游发展路径概览。这项研究为小岛屿发展中国家的决策者提供了可能有用的经验和交叉学习机会。本文研究局限在于, 只有在与加勒比小岛屿发展中国家类似的宏观经济管理结构和文化特征的行政区, 研究结果才可能转移和推广。

这篇论文提供了有意义的讨论, 有助于认知加勒比旅游发展史、可持续发展的挑战和未来潜力, 并为加勒比和其他小岛屿发展中国家的未来研究提供了机会。

该研究概述了包容性、负责任和可持续的旅游发展的社会启示, 这些启示可能使加勒比小岛屿发展中国家从缓慢发展转变为开发旅游产品(包括技术环境)的效率。这有助于减少不平等现象, 促进社会经济发展, 并改善该地区的人力资本。

本文提供了加勒比旅游发展的综合比较分析, 具体到牙买加、特立尼达和多巴哥、巴巴多斯和东加勒比国家。此前没有研究对这些国家的旅游业发展进行比较。因此, 这篇论文为决策者提供必要信息和为这一领域的继续研究建立了基础。

Este trabajo ofrece un análisis comparativo del desarrollo del turismo sostenible en toda la región del Caribe anglófono desde el período posterior a la independencia de 1962 hasta la década de 2020. Se explora las implicaciones de la insularidad, la inversión turística y el ritmo de adopción de la tecnología en la posible realización de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) en las islas de Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad y Tobago y los Estados del Caribe Oriental.

Diseño/metodología/enfoque

El análisis se basa en datos secundarios bibliográficos a partir de documentos de política gubernamental, literatura académica, periódicos e informes de consultoría para explorar los temas centrales y proporcionar un marco conceptual en este documento.

Conclusiones

Las conclusiones revelan que los pequeños estados insulares en desarrollo (Caribbean Small Island Developing States, SIDS) están más próximos del enfoque del turismo como único sector económico o sostenibilidad débil para el desarrollo del turismo sostenible. Las conclusiones generales revelan que la fuerte concentración de la región en las prioridades económicas hace que se preste menos atención a los retos de la competitividad, como la gestión medioambiental, la equidad social y las innovaciones tecnológicas.

Limitaciones/implicaciones de la investigación