- Aviation History

Aviation In The 1920’s – 1930’s

It is unknown when the first passenger aircraft services took place in the United States, but one of the earliest recorded instances was in 1913.

Sular Christofferson transported passengers between San Francisco and Oakland harbours by hydroplane.

Another early instance was in 1914 when passengers were carried from Tampa and St. Petersburg, Florida by a Benoist airboat.

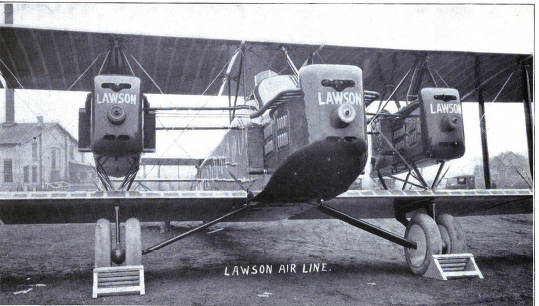

One of the first steps in commercial aviation was the development of the multi-engine airplane by Alfred W. Lawson after WW1.

The Lawson C-2, built in 1919, was created specifically to carry passengers.

Related Article – Instrument Proficiency Check (IPC): 4 Things You Need To Know

The plane was somewhat a failure; the price of military aircraft was much cheaper, so the C-2 was not worth the price to buy.

Lawson went on to build the L-3 and L-4, both larger aircraft that were capable of carrying 34 passengers and up to 6,000 pounds of cargo.

Problems arose once again, this time after the plane crashed on its first flight, causing the development of the L-4 to come to a halt.

In 1920, a Florida entrepreneur by the name of Inglis Uppercu started to offer international flights from Key West, Florida, to Havana, Cuba.

The service was eventually extended to other parts of the country, and there were flights between Miami and the Bahamas, New York and Havana, and the Midwest states of Cleveland, Ohio, and Detroit.

Uppercu’s Aeromarine Airways’ “airborne limousines” were going strong until one crashed off the coast of Florida, resulting in the death of four passengers and the company going out of business in 1924.

One of the big moments in commercial aviation came when mail began to be delivered by air.

In the early 1900s, the common means of transportation for mail was by railroad systems connecting cities in the country.

The first official airmail flight took place in 1918, and it rapidly increased after that.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

By 1925, the U.S. Post Office was delivering 14 million pieces of mail per year by airplane.

This new mailing method was especially popular among those in the financial industry who wanted a quicker way to mail checks and documents.

Airmail was eventually transferred to private companies from the government, and the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925, known as the Kelly Act, was sponsored.

The act was the first big step in creating the private U.S. airline industry.

Soon after the establishment of the Kelly Act, the Post Office began to give out contracts to private companies after they bid on certain routes.

This continued to expand for almost a decade, and the private companies went on to become the major transportation players in commercial aviation.

Henry Ford was awarded the Chicago-Detroit and Cleveland-Detroit routes after obtaining the Stout Metal Airplane Company in 1925.

He went on to establish the Ford Air Transport Service, and he developed the “Tin Goose,” an all-metal Ford Trimotor.

Ford was involved in the mailing industry for a short three years before going back to manufacturing.

The government created a national aviation policy in 1926 after President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board headed by Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan.

Morrow was not supportive of directly subsidizing airlines.

Instead, he wanted the government to fund a national air transportation system, which was taken up and recommended by Congress in the Air Commerce Act of 1926.

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

The act gave a lot of authority to the Secretary of Commerce, who then had a role in the development of air navigation systems, air routes, the licensing of pilots and aircraft, and investigations surrounding accidents.

The Kelly Act was eventually amended by Congress, and the government carriers were paid based on the weight of the mail they were carrying.

These changes played a big role in the financial success of the airlines.

Research and training were also going through changes in the 1920s, especially with the establishment of a foundation by Harry Guggenheim.

His foundation aimed to develop flight instruments and educate aeronautical engineers at universities.

Besides his foundation, Guggenheim was involved in funding the Western Air Express, which included a $180,000 experiment to know if airlines could profit solely from passenger transportation.

The experiment failed after they were not able to make sufficient money without the subsidies.

The Western Air Express experiment was one of many that failed.

This changed in May of 1927 when Charles A. Lindbergh flew solo to Paris.

After the successful flight, investors were excited, and aviation stocks tripled between 1927 and 1929.

This helped propel the commercial aviation industry forward.

Even with all of the developments in commercial aviation, passengers could still get to their destination faster by train in the late 1920s.

There were too many limitations with planes compared to trains, which were able to travel through mountains, could run at night, and did not have to land and refuel like aircraft.

On top of that, trains were more comfortable than planes.

Passengers in the air dealt with loud noises, forcing them to put cotton in their ears, and the cabins were un-pressurized.

Despite all of the uncomfortable and limiting aspects of air travel, air travel grew in popularity.

The number of airline passengers in the United States went from less than 6,000 in 1926 to about 173,000 in 1929.

The passengers mostly consisted of businessmen, who increasingly had their tickets paid by employers.

The Ford Trimotor 5-AT, introduced in 1928 and produced through 1932, was popular among most U.S. airlines.

It carried up to 15 passengers, and there was one still being used all the way up until 1991 in Las Vegas.

The aviation industry continued to grow with the creation of jobs, airports, warehouses, aeronautical schools, and new technology.

The first instrument navigation package was used by U.S. Army lieutenant James Doolittle in September 1929.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

Research at the Full Flight Laboratory, established by Harry Guggenheim, helped create an extremely accurate barometer, a radio direction beacon to help land, and a Sperry artificial horizon and gyroscope.

These allowed Doolittle to fly 15 miles without having to look outside his cockpit, revolutionary for air travel.

Even with all of the advancements and excitement in commercial aviation during the 1920s, the part of the industry dealing with passenger-only routes failed to make a profit.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that these airlines began to make financial gains.

Aviation in the 1920's

4.5 out of 5 (111 ratings), related articles you might be interested in:.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- Publisher’s Message

- Editor’s Notebook

- Airline News

- Airport Community

- Airport Employment News

- Airport Safety & Security

- AOA Reflections

- Company Spotlight

- Ground Services

- New York Aviation History

- Non-Rev Traveler

- Airport & Aviation Events

- Airport Employment

- Latest Issue

Subscribe for Updates

Get the latest local airport and aviation news delivered right into your inbox each week!

By signing up, you agree to the our terms and our Privacy Policy agreement.

News Updates

Aviation Day at CUNY York College

Managing the Risks to Our Fragile Global Supply Chains

Queens Business Expo 2024

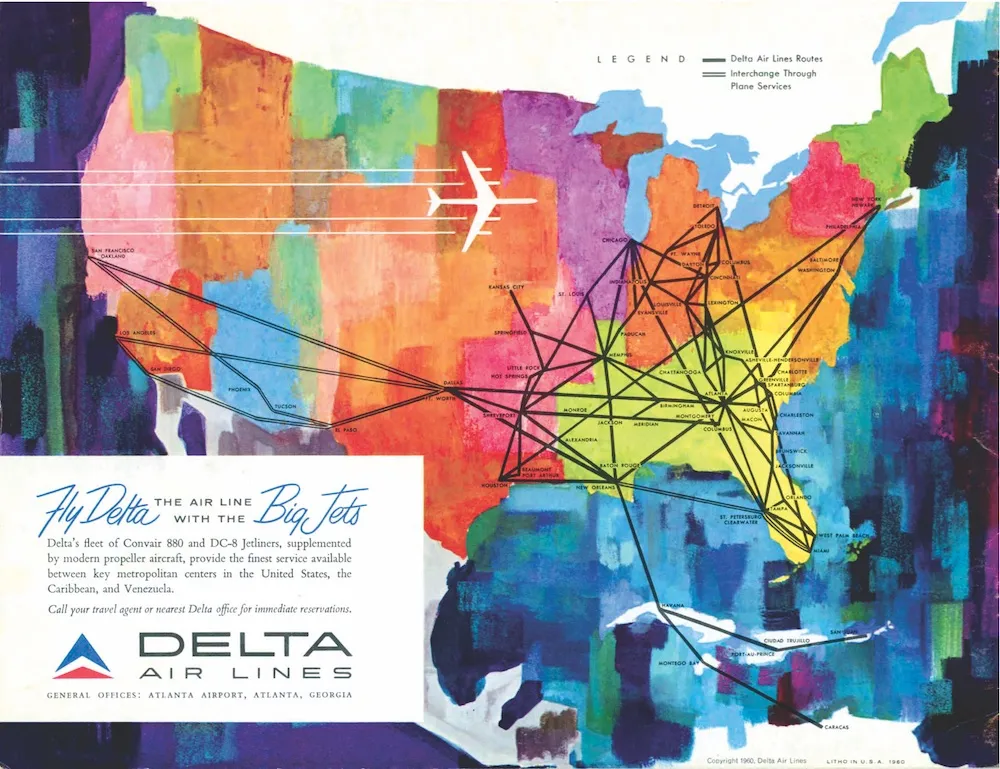

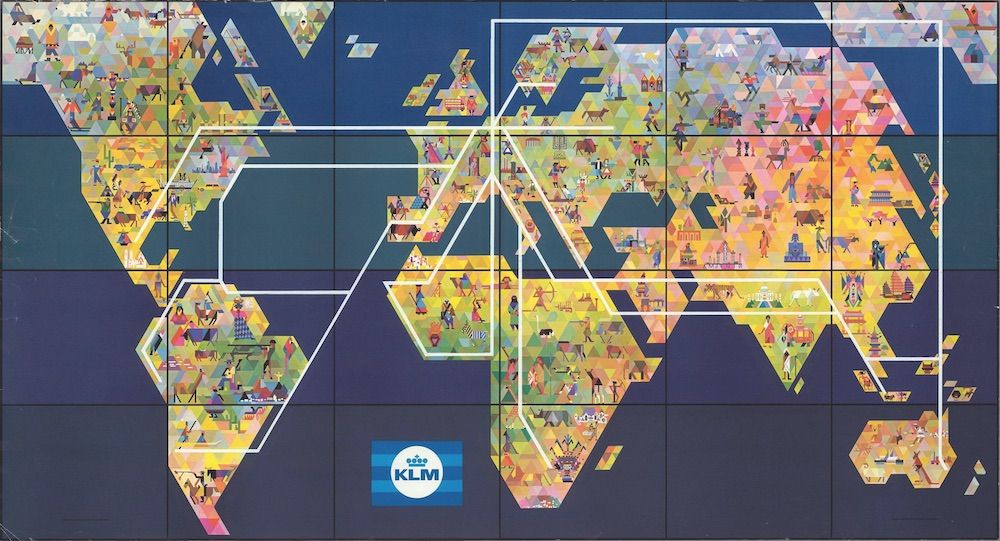

Travel By Air, The Golden Years: 1920s-1960s

The story of commercial air travel, in a heavier-than-air, winged aircraft, began on January 1, 1914, when the world’s first scheduled passenger service took to the skies in a single-engine Benoist flying boat piloted by pioneering aviator Tony Jannus for the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line. That morning, as a crowd of 3,000 gathered at St. Pete’s municipal pier, a ticket for the inaugural round-trip flight to Tampa was auctioned off, and former mayor Abraham Pheil won the honor with a bid of $400. Prior to lifting off from the St. Petersburg waterfront, Pheil climbed aboard the open cockpit biplane and squeezed onto a single wooden seat beside Jannus. Flying no higher than fifty feet over the water, the flight across the bay to Tampa took 23 minutes, as opposed to the two hours it would take by steamship, or the nearly 12 hours by railroad. Henceforth, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line made two flights daily, six days a week, and charged a regular fare of five dollars per passenger. While the Airboat Line only operated for four months, it carried more than 1,200 passengers across the bay, and led the way for regularly scheduled trans-continental flights.

The Golden Age of Flight

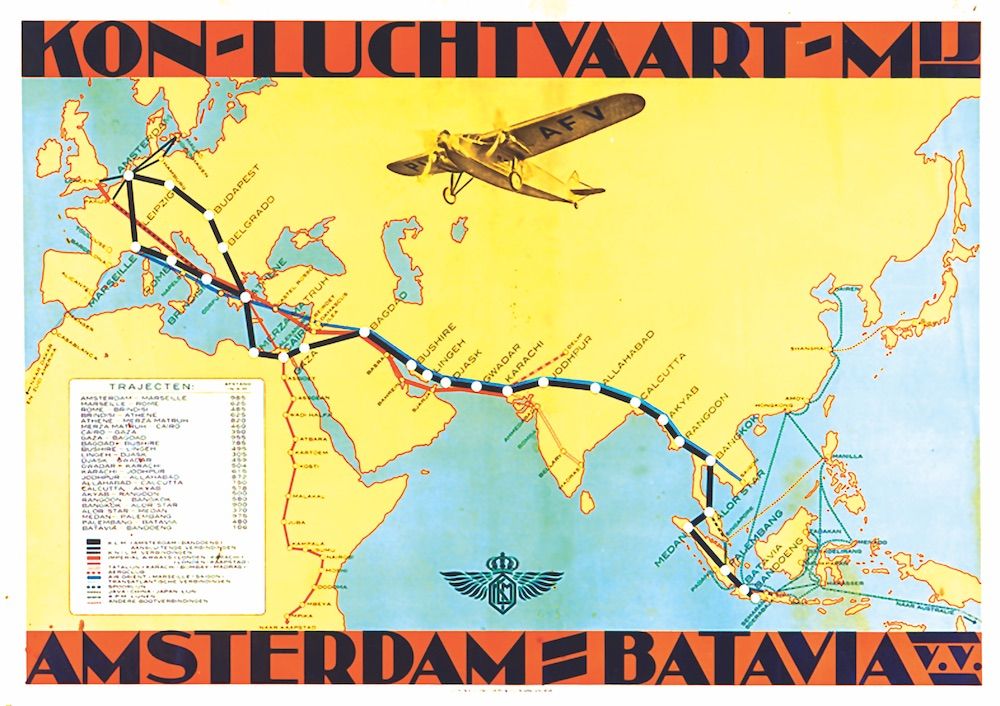

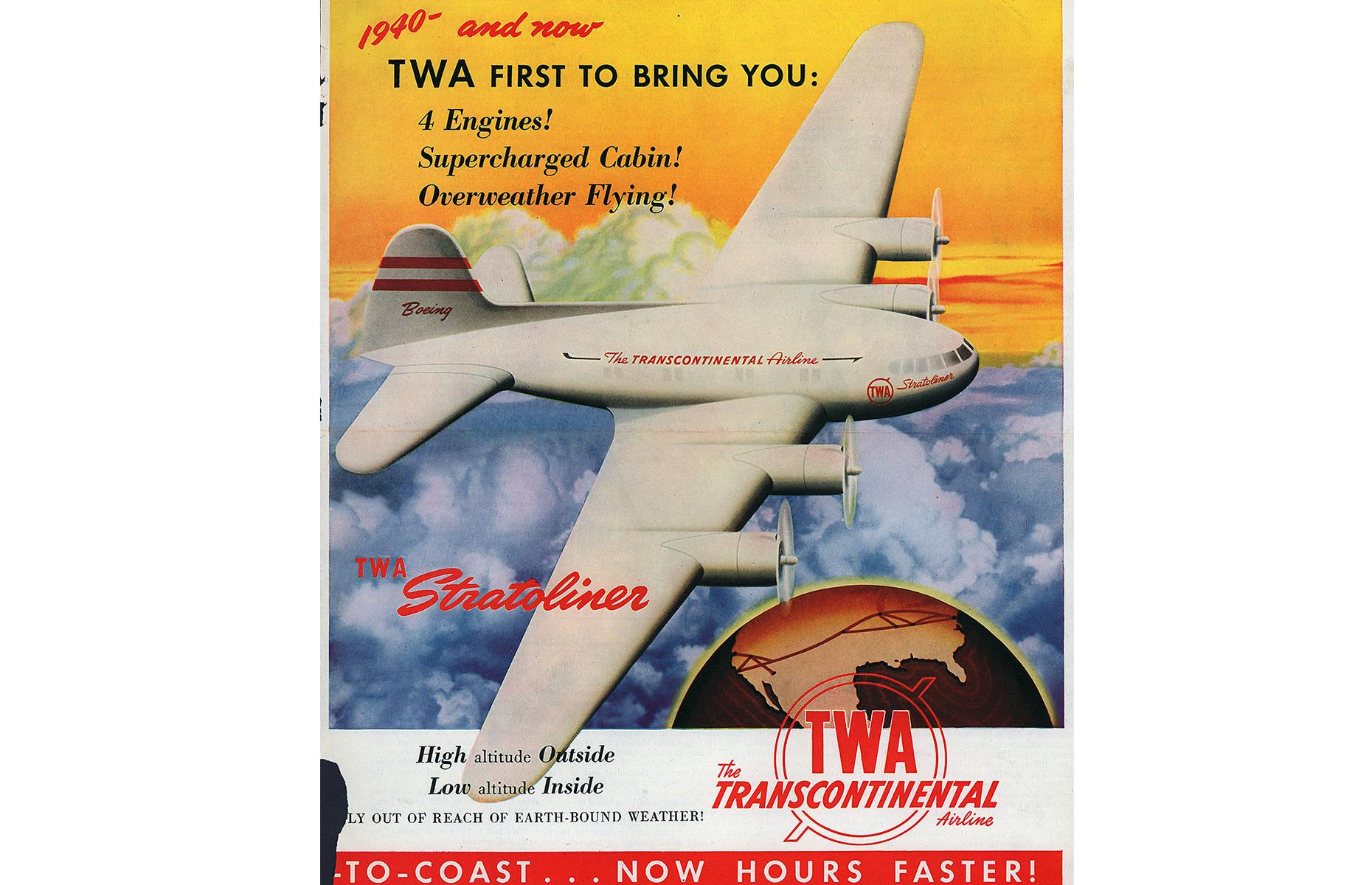

In post-World War I, as the aviation industry grew, several commercial airlines began operations delivering U.S. Airmail, and then carrying passengers. In the 1920s and 1930s, the period between the two World Wars became known as the Golden Age of Flight. Many of the most notable early airlines were founded during this time period; Western Air Express and Ford Air Transport Service in 1925; Pan American Airways in 1927, which flew airmail from Key West to Havana, and Transcontinental & Western Airlines in 1930 (later TWA), when Western Air Express merged with Transcontinental Air Transport.

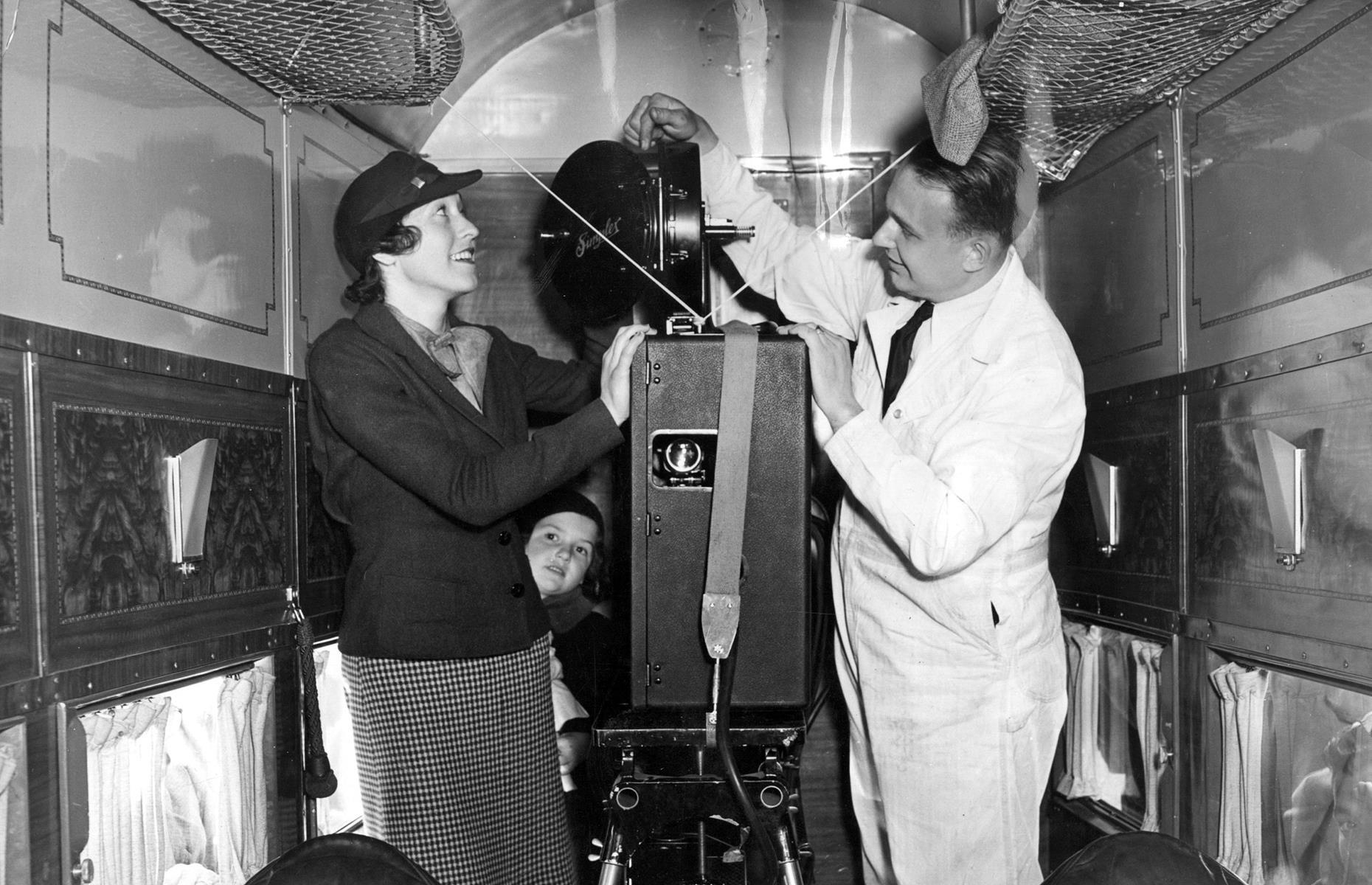

Life aboard a 1920s airliner was quite different from what it is today. Flying was a novel, upscale experience reserved for the wealthiest members of society and business travelers. Airliners carried less than 20 passengers and flew at lower altitudes in unpressurized cabins, frequently landing to refuel. Air travel was noisy and cold, and passengers wore their coats and hats to keep warm. In order to accommodate their every need, uniformed air stewards assisted passengers with their baggage and helped them board the aircraft. Onboard amenities included meals that typically included fruit compotes, cold fried chicken, and elegantly composed sandwiches served on lightweight dishware or wicker baskets. Before the advent of instrument flight in 1929, airplanes could not fly safely at night and had to circumvent mountains. Turbulence, lengthy flight times, airsickness, and other flight-related discomforts often resulted in travel anxiety. In order to keep air travelers at ease, airlines hired nurses to attend to passengers. In 1930, Ellen Church, a nurse and licensed pilot, was hired by Boeing Air Transport (now United Airlines) as the first female stewardess. Despite these discomforts, service evolved quickly in the 1930s. According to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the airline industry expanded from transporting 6,000 passengers in 1930 to over 450,000 by 1934, and 1.2 million by 1938.

The Douglas DC-3 would revolutionize commercial air travel when it had its first flight in 1935. Faster, larger, and more comfortable than its predecessors; the first DC-3, the Douglas Sleeper Transport, was the pinnacle of luxury, with plush seats in four main compartments designed to fold down from the cabin ceiling into sleeping berths. The aircraft could accommodate up to twenty-eight passengers for shorter day flights and fourteen overnight. As a reliable, economical, and profitable airliner, commercial aviation industry giants such as American, United, and TWA ordered the DC-3 for their fleets in 1936 and many other airlines followed suit in the next two years.

The 1930s heralded in many of the earliest commercial trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways was a forerunner, carrying passengers across the Atlantic in their fleet of flying boats, or ‘Clipper’ aircraft. Transatlantic service began in May of 1939, first flying from Port Washington, Long Island, as the new Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia was being built. That same year, Boeing 314s were considered the ultimate ‘Clippers’, carrying up to seventy-four passengers across the Atlantic and entering trans-Pacific service, linking all the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. The B-314 was a long-range flying boat that could land anywhere at sea, providing the destination had a sheltered harbor in which it could taxi to. But transport in the 314 was still reserved for the very wealthy, and a return ticket between Manhasset Bay in Port Washington to Southampton, England cost over $650; the equivalent of over $12,000 today.

Striving to provide the most pleasant flight experience, Pan American Airways set the gold standard of passenger service. The Boeing 314 had a large upper flight deck and a lower passenger cabin divided into five seating compartments. There was a galley kitchen, a baggage compartment, men, and women’s changing and restrooms, as well as a main lounge that converted into a dining room. White-gloved, tuxedo-clad stewards catered to their passenger’s needs. Meals were lavish experiences with gourmet foods and drink served on fine china, and silverware set on white linen tablecloths. Sleeping quarters on the 314 were roomier than earlier Clippers and its aft De Lux Compartment was called the ‘Bridal Suite’.

“I have heard many planes referred to as flying hotels, but none is more worthy of that description than the Pan American Airways Clipper.” A Wright Aeronautical Co. observer on a B-314 survey flight

First flown in 1938, the Boeing 307 Stratoliner was the first four-engine airliner with a pressurized cabin, allowing it to cruise at an altitude of 20,000 feet, well above the clouds and higher than rough weather. Pan American entered the B-307 into scheduled domestic service on July 4, 1940, with routes to Latin America, and from New York to Los Angeles. The nearly 12-foot-wide cabin carried thirty-three passengers in comfort and provided space for comfortable berths for overnight travelers, as well as observation areas for those who bought the more expensive seats. The airplane’s circular fuselage provided maximum space for five crew members and the Stratoliner was the first land-based airliner to have a flight engineer as a member of the crew.

With the onset of the Second World War, commercial air travel came to a virtual halt and was limited only to those serving the war effort. But commercial aviation, along with the aviation industry as a whole, grew substantially during wartime with the development and production of large-scale aircraft and the utilization of ex-military bombers and transports that were easily converted into commercial airliners. In the post-war years, Lockheed C-69 Constellations, used as transports by the U.S. Army Air Forces, were purchased from the government by TWA and converted into civilian airliners for their fleet. After TWA’s first transatlantic demonstration flight in the Constellation, or ‘Connie’ in December of 1945, TWA launched its transatlantic service in the Connie with a flight from New York to Paris on February 6, 1946.

The Golden Age of Air Travel

After 1945, American aircraft technology set the standard for international air operations, and toward the end of the 1940s, major carriers achieved a strong foothold on international travel.

As the decade of the 1940s ended, the era of commercial flight between the 1950s and 1960s was born and became known as the ‘Golden Age of Air Travel’ and the ‘Jet Age’. By 1950, the trans-Atlantic route became the most traveled in the world, and its growing trade produced high profits and intense competition between major international airlines. In the United States, commercial jet service began with the introduction of the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. Larger and more economical than its previous airliners, Pan American began international flights on the B-707 in October of 1958. National Airlines soon began domestic jet service with the 707, and American Airlines opened its own domestic jet service in January of 1959, with a flight from New York to Los Angeles. At the end of the decade, for the first time in history, more people in the United States traveled by air than by railroad.

Despite its immense growth, air travel was still expensive and reserved for the elite – celebrities, and movie stars, who were called the ‘Jet Set,’ a name coined in the early 1950s by journalist Igor Cassini. Since commercial flight was still a unique, awe-inspiring event, passengers often documented their experience on airline postcards and posed for group photos prior to boarding. They dressed in their finest clothes, with women in dresses and heels, and men in tailored suits. First Class was spacious, and ‘economy’ seating provided up to six inches more legroom than today. With an increased market for air travel, airlines competed to outdo each other by offering their passengers extravagant amenities; in-flight entertainment, free-flowing cocktails, and fancy multi-course meals that included soup, salad, carved meats, vegetables, dessert, and even lobster. In a 1952 TWA (Trans World Airlines) ad captioned, ‘’Have dinner tonight with the stars!”, an elegantly dressed couple is depicted sitting before a lavishly set table while being served by a burgundy-coated steward and a perfectly coiffed stewardess in uniform and cap.

As the Golden Age of Air Travel led on, well into the 1960s, those who were fortunate enough to enjoy travel on the newest commercial jetliners featured some of the biggest celebrities of the day, including the Beatles, who arrived at JFK International in New York from London aboard a Pan American Boeing 707, to thousands of screaming fans, and some 200 journalists in February of 1964 ….fifty years after the first scheduled flight in the Benoist flying boat before a crowd of 3,000. And while the principles of flight remain the same, commercial air travel as we know it today may not be as lavish an experience as it once was during its Golden Days, but it certainly has come a very long way.

Experience the Golden Days of Air Travel

Today, the Pan Am Museum Foundation Exhibit at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, Long Island pays tribute to Pan American World Airways as a pioneer in commercial aviation through the preservation of Pan Am artifacts, memorabilia, and images that commemorate the company’s history and the people behind this legendary airline.

Also today, at the TWA Hotel at JFK International Airport, visitors are welcome to view the New York Historical Society’s curated exhibitions celebrating TWA’s history. Located within and throughout the former iconic TWA terminal, designed by Eero Saarinen in 1962, the exhibits allow visitors to experience the Jet Age through authentic artifacts, interactive displays, uniforms, memorabilia, and personal narratives. Both are a must see!

Julia Lauria-Blum earned a degree in the Visual Arts at SUNY New Paltz. An early interest in women aviation pioneers led her to research the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of WW II. In 2001 she curated the permanent WASP exhibit at the American Airpower Museum (AAM) in Farmingdale, NY, and later curated 'Women Who Brought the War Home, Women War Correspondents, WWII’ at the AAM. Julia is the former curatorial assistant at the Cradle of Aviation Museum and is currently an editor for Metropolitan Airport News .

RELATED NEWS & UPDATES

Delta Air Lines Unveils the Team USA-inspired A350

API Selected by SkyWest for Full Suite of Crew Management Solutions

National, the Sunshine Airline

LaGuardia Gateway Partners Welcomes Frontier Airlines to LGA Terminal B

Korean Air to Roll Out Eco-Friendly Uniforms for Maintenance, Aerospace and Cargo Teams

Korean Air Celebrates 45 Years of Serving New York

Such an interesting historical synopsis of commercial aviation! Well done!

In June 1967 I flew out of El Toro Marine Air Base California towards Vietnam. I returned to SF International in September 1968 via another commercial airline. As did thousands of other GIs going to Vietnam but not so many coming home. I highly recommend purchasing the book by BJ Elliott Prior titled Behind My Wings.

Thank you for comments, Robert. I look forward to obtaining a copy of Behind My Wings and reading about the GIs returning home. I have very strong visual memories of the returning veterans, and especially the POWs.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Birth of Aviation

The history of commercial aviation, the birth of commercial aviation.

Commercial aviation has changed the world immeasurably, facilitating world trade and economic growth, bringing people together in a way that was not possible before, and simply making the world a more connected place. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), airlines in 2014 connected 3.3 billion people and 52 million tonnes of cargo over 50,000 routes, supporting 58 million jobs and delivering goods with a value of $6.8 trillion [ 1 ] . But when and where does commercial aviation find its inception?

COMMERCIAL AVIATION HISTORY

From the earliest beginnings, man’s ascent to flight has been one of gradual progress, accented by a handful of dramatic breakthroughs. The Wright Brother’s accomplishment would of course be one such breakthrough. Though several others can claim successful efforts at manned, powered flight prior to Kitty Hawk (see article, “First Human Flying Machines” ), the Wright Brothers hold a special place in history because of the profound and lasting impact of their achievement in relation to modern aircraft design (three-axis control).

Similarly, in the history of commercial aviation there is evidence of gradual evolution – from stunt plane and site seeing passenger flights to flying airboats that flew just a few feet above the water to the first real examples of modern air travel involving regularly-scheduled overland air service using land-based runways. And there are a few critical breakthroughs as well that would play a important role in the birth of a new industry. One of those breakthroughs was spurred on by a group of individuals in the mid-1920s led by the Guggenheims – a family who amassed a great fortune in the mining industry, and then turned their focus towards giving back to society. Together, they shared the vision of making passenger airtravel a sustainable reality, along with the spirit of boldness to make it happen. The elder Daniel Guggenheim would say of aviation at a 1925 groundbreaking ceremony for construction of the nation’s first school of aeronautics at a major American college, “I consider it the greatest road to opportunity which lies before the science and commerce of the civilized countries of the earth today.” [ 2 ]

Harry Guggenheim and Charles Lindberg leaving New Western Air Express plane in 1928. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Western Air Express pilot Jimmy James. [see page for license], via Wikimedia Commons

As such, when Western Airlines became part of Delta in 1986, Delta inherited bragging rights to the oldest ticket sold for passenger airtravel. No U.S. airliner in operation today can say it issued a ticket prior to the one sold in 1926 to Mr Ben Redman of Salt Lake City, Utah.

THE FIRST PASSENGERS

When Western Air Express pilot C.N. “Jimmy” James took off on his regular eight-hour mail delivery flight from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles on May 23, 1926 – almost exactly one year prior to the famous transatlantic flight of Charles Lindberg – he would do so carrying what was proudly referred to by Western Airlines CEO Arthur Kelly in 1961 as the “first commercial airline passenger”. [ 15 ] The recipient of this honor would be then president of the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce Ben F. Redman who, along with his friend (and second passenger) J.A. Tomlinson, sat atop U.S. mail sacks, sported his own parachutes, and relied on a tin cup for the in-flight lavatory.

Source: “Western Airlines Marks Anniversary of S.L. Flight”, Salt Lake City Tribune , April 17, 1944, p.16

Later, Redman and James would appear with Elliot Roosevelt, son of President Roosevelt, as Elliot would receive the honor of being the 100,000th passenger flying from Los Angeles via Western Air Express on that same route. (See below)

Source: “Elliott Roosevelt Inspects Airlines”, Salt Lake City Tribune , September 25, 1933, p.22.

“They took off at 9:30am and five hours later landed at Las Vegas to refuel. Redman and Tomlinson staggered out of the plane to stretch their legs and would have been forgiven if they had refused to reboard; for a good portion of the trip they had flown through a dust storm, and both passengers were pale from fatigue and nervousness. But they also were game, and three hours later climbed more or less jauntily out of the M-2, waving to the crowd of photographers and reporters gathered at Vail Field to record the arrival.” [ 16 ]

Upon completion of the inaugural flight, a certificate signed by the pilot Jimmy James was presented. The certificate (shown below) confirms Redman as the first official passenger , as well as recording details of the flight including maximum altitude reached (12,000 feet), the maximum speed (130 mph), total flying time (8 hours), and Contract Air Mail Route (No. 4).

Certificate confirming Mr. Ben Redman of Salt Lake City, Utah as the first official passenger to fly on Western Air Express. This was presented in a ceremony after WAE’s inauguration of passenger service on May 23, 1926, which represented the first “regularly scheduled passenger flight” in the United States. Part of the BirthofAviation.org Collection. ( see preferred citation )

FIRST TRUE SUCCESS STORY IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION

Perhaps most significant of all regarding Western Air Express’s inauguration of passenger service is that it marked the beginning of the first true success story in U.S. commercial aviation. For as mentioned there were a few early airboat ventures that did sell tickets for airtravel prior to 1926. Yet they would all end in bankruptcy, most going out of business shortly after their inception (see First U.S. Passenger Airlines ). The February 1976 edition of The Vintage Airplane thus declared, “Western Air Lines is the only survivor of airlines that pioneered commercial air transportation in the U.S. in the mid-twenties.” [ 17 ]

Vintage Art Poster shows a Western Air Express plane flying over the location where the Golden Gate Bridge now stands.

Helped by the Guggenheim grant, along with the infrasture and other innovations spawned by the model airline experiment over the next few years, Western would not only avoid bankruptcy but would go on to become an industry giant. After surprising many by posting a profit of $28,674.19 in its first year of operation, [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Western Air Express would the following year, in 1927, become the first airline in history to pay a cash dividend to its stockholders. [ 20 ] In 1928, it would post a profit of approximately $700,000. [ 21 ] And by 1930 it had become the largest airline in the nation by most overall standards of measurement – including fleet size, passengers carried, and route mileage with routes stretching 15,832 miles. [ 22 ] (That same year it would also introduce to the world of commercial aviation what was at the time by far the largest passenger plane in the world, the four-engined 32-passenger Fokker F-32, as shown below). [ 23 ]

Of course, the Guggenheim fund that helped fuel this success was never intended to provide an economic advantage to any one airline in particular, but rather to buoy the entire industry – and that is indeed what it did. The success of the model airline experiment would not only benefit Western but would in effect usher in the beginning of sustainable economic progress for all U.S. airliners through a number of key innovations.

One innovation of lasting impact achieved by the model airline would be the first weather reporting for passenger airplanes. In August 1927, the Daniel Guggenheim Committee on Aeronautical Meteorology was created to make pilots and meteorologists aware of each other’s specialties. The five-person committee, all of whom would achieve prominence in meteorology and two of whom would become chiefs of the Weather Bureau, recommended that the Guggenheim Fund equip a section of the airway system with weather reporting systems to prove the feasibility of such a system. Ultimately, it was decided to carry this out along the Western Air Express model air line route, resulting in an initial twenty-two reporting stations connected via telephone to Los Angeles and San Francisco, and soon later more would be added. These would serve all airmen, not just those of Western Air Express.

This project, involving collaboration from the Department of Commerce and the Weather Bureau, as well as the army, would add great benefit not only in economy of operation but also in safety. Lt. Col. G.C. Brant, at the time commandant of the Army Air Corps base at Crissy Field in San Francisco, would state, “The Guggenheim Experimental Airways Weather Service has done more to raise the morale of the Army Flying Corps than anything else that has happened since I became associated with it. Formerly a pilot did not know what was ahead, now he knows and is prepared.” [ 24 ]

A dazzling Lucille Ball is shown here after a flight on a Western Air Express Fokker F-10, a plane referred to as the “Queen of the Model Airline”.

Even though mail revenues still constituted the majority of income, and profitability solely from passenger service was still a few years away, the public relations impact, the technological advancements, and the lessons learned as a result of the model airline experiment would greatly facilitate eventual realization of profitability in the industry. Though there would be many ups and downs in the years to come, [ N 3 ] Western Air Express and the rest of the budding airline industry in America had positioned themselves on arguably the first path to sound economic success in the world of commercial aviation. Other carriers would soon follow Western Air Express’s lead in providing passenger service across the nation, with increasingly safe and cost effective passenger aircraft. America was officially on its way to emerging as a global leader. Western would even stake its claim not only as a domestic pioneer but as “ the world’s first economically successful venture in airplane transportation ” [ 27 ] . (See this referred to on Western’s First Anniversary Flight Postcard) . One of the reasons Western was able to make this claim is that although commercial aviation in Europe and other places around the globe got off to a quicker start in many areas including number of passengers carried, this didn’t translate to profits. As Tom D. Crouch, senior curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum, writes in Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age , “The pioneering postwar airline ventures in England, France, and Germany enjoyed some early successes. British and French air services carried sixty-five hundred passengers between London and Paris in 1920, with the three British operations carrying perhaps three times as many passengers as their French counterparts. At the same time, actual revenues amounted to only 17 percent of total costs.” [ 28 ] Many of these European ventures would not be long lived as a result of the unsound economics. And even many of those that did survive like KLM (officially the world’s oldest airline) would do so not because of economically successful operations in those days but because they were largely supported by government subsidies, unlike Western Air Express. [ 29 ] [ 30 ] [ N 4 ] As Woolley writes again in Airplane Transportation , “To secure consideration of the airplane as a commercial vehicle required, in Europe, direct financial assistance from government; in the United States, only evidence of its economic worth.” [ 31 ] And in 1936, Col. E.S. Gorrell, then president of the Air Transport Association of America, said of a partnership between five of the major airlines to build a 40-passenger super-airliner, “This contract marks a significant step for advancement of commercial aviation. Unlike every other country, where heavy government subsidies are devoted to the development and advancement of air transport aircraft, private enterprise in the United States, the individual operator, must carry this entire burden.” [ 32 ] [ N 5 ]

EXPONENTIAL GROWTH

When C.G. Grey, the editor of the English aeronautical journal Flight , arrived in New York in January 1925 to gauge the state of aeronautics in the United States. he commented, “The general atmosphere of aviation in America impressed one as being in a state when something is about to happen. Not so much the calm before the storm, but rather the slump before the boom.” [ 33 ] These words would prove to be prophetic as the U.S. airline industry would grow exponentially after 1926. With less than 6,000 airline passengers in the United States recorded in 1926, this would grow to approximately 173,000 in 1929, and a decade later this number would be approximately one million passengers. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ N 6 ] Col. E.S. Gorrell again commented in 1936, “Air passenger traffic has increased at a more rapid rate in the United States than anywhere else in the world, largely due to superior aircraft and operations methods. In the past five years passengers carried on domestic and foreign airlines under the American flag have increased from 385,000 in 1930 to nearly 1,000,000 in 1935.” [ 36 ] Passenger airtravel had become a reality. The U.S. aviation industry would eventually go on to represent the largest single market in the world, accounting today for over one‐third of the world’s total air traffic [ 37 ] (in addition to claiming the world’s largest airline, American Airlines). It may also be said that an even brighter future yet awaits it. In fact, by the year following the upcoming centennial of that inaugural passenger flight of Western Air Express (2027), the FAA projects air travel demand in the U.S. to top 1 billion passengers per year. [ 38 ]

At the same time, the real birth of commercial aviation is not merely a story of a landmark flight or even that of a handful of pioneers and philanthropists. It is the story of a nation. In order to make possible the conditions for success, many pieces needed to come together. And this would involve one of the greatest collaborative efforts in all of human history

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR SUCCESS

During the first decade or so following the Wright Brother’s first flight, America lagged behind Europe with regard to aviation. As C.V. Glines writes in an article published in the the November 1996 edition of Aviation History magazine:

The United States clearly was in the doldrums so far as aviation was concerned. By contrast, a year after the armistice, Britain and France were operating scheduled flights between London and Paris. The Germans had an all-metal transport 10 years before William Stout designed one for Henry Ford. The French had an internal airmail system that far outdistanced the United States’ fledgling airmail service. Italy’s Gianni Caproni had built a 100-passenger, eight-engine flying boat. And even the Russians, as far back as 1913, had a four-engine airliner designed by Igor Sikorsky that boasted an enclosed cockpit and passenger cabin, electric lights and a washroom. [ 39 ]

But even as America itself was founded in a story of “beating the odds”, so too would this generation of Americans rise up to meet the challenge before it – heeding the wisdom of the words spoken by one of the nation’s brightest businessmen and entrepreneurs of the time, Henry Ford: “When everything seems to be going against you, remember that the airplane takes off against the wind, not with it.” A movement would soon take off in America that would change its fortunes – a movement that would find its impetus when the U.S. Government first began experimenting with the use of planes to transport mail.

In 1917 Congress, acting on a recommendation from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) which would later become NASA, appropriated $100,000 for the creation of an experimental airmail service. This would include involvement from both the Army and the Post Office. One of the contributions from the Army was providing pilots to fly the mail planes – a particularly dangerous job. In fact, during the period the Post Office operated the air mail, the life expectancy of a Mail Service pilot was only four years, and thirty one of the first forty pilots were killed in action. [ 40 ]

The Army also assisted with the initial deployment of rotating beacons that would make it possible to fly the routes at night. The Post Office would take over soon afterwards, expanding the guidance system the following year to make transcontinental air service possible. By 1923, mail could be delivered from one coast to the other in two days less time than by train.

Once the basic infrastructure was in place for airmail to work, the U.S. Government sought to transfer this service to private companies. As described in The Airline Handbook from Airlines for America (America’s oldest and largest airline trade association):

“Once the feasibility of airmail was firmly established and airline facilities were in place, the government moved to transfer airmail service to the private sector by way of competitive bids. The legislative authority for the move was granted by the Contract Air Mail Act of 1925, commonly referred to as the Kelly Act after its chief sponsor, Rep. Clyde Kelly of Pennsylvania. This was the first major step toward the creation of a private U.S. airline industry. [emphasis added]” [ 41 ]

Through a balance of government and private industry very much in harmony with the spirit of America, the stage was set for the dawning era in the history of aviation. The U.S. government through its numerous efforts to facilitate aviation nationwide would provide essentially a “hand up” to private enterprise, then largely get out of the way – even though it would step in once again though the Air Commerce Act of 1926 in order to provide needed coordination as well as a set of essential checks and balances. [ N 7 ] As described again in The Airline Handbook :

“The same year Congress passed the Contract Air Mail Act, President Calvin Coolidge appointed a board to recommend a national aviation policy (a much-sought-after goal of then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover). Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in J.P. Morgan’s bank, and later the father-in-law of Charles Lindbergh, was named chairman. The board, popularly known as the Morrow Board, heard testimony from 99 people and, on Nov. 30, 1925, submitted its report to President Coolidge. The report was wide-ranging, but its key recommendation was that the government should set standards for civil aviation and that the standards should be set outside of the military. “Congress adopted the recommendations of the Morrow Board almost to the letter in the Air Commerce Act of 1926. The legislation authorized the Secretary of Commerce to designate air routes, to develop air navigation systems, to license pilots and aircraft and to investigate accidents. The act brought the government into commercial aviation as regulator of the private airlines that the Kelly Act of the previous year had spawned.” [ 42 ]

Through these acts of Congress in 1925 and 1926, the essential framework had been established, and the ground was ripe for the birth of a new industry. In fact, the initial Contract Air Mail (CAM) service carriers selected through this process would in time and through mergers and acquisitions go on to become key players in the airline industry, including American Airlines, United Airlines, Western Airlines (which as mentioned would eventually be acquired by Delta Airlines, who was also a CAM carrier beginning in 1934), Boeing, Pan Am, Trans World Airlines (TWA), Northwest Airlines, Braniff, Continental, and Eastern Airlines. These would also greatly influence the advancement of technology and infrastructure that would allow passenger airtravel to survive and prosper in the decades to follow.

Initial Contract Air Mail (CAM) Routes

Starting with an initial group of five, a total of 34 Contract Air Mail routes would eventually be established in the U.S. between February 15, 1926, and October 25, 1930.

The “first five” CAM contractors would include:

1926 – A WATERSHED YEAR FOR COMMERCIAL AVIATION

The aforementioned book Airplane Transportation by James Woolley was used as a textbook at the University of Southern California and several other schools. With contributing works from famed meteorologist Carl-Gustav Rossby and William P. MacCracken, Jr., the first federal regulator of commercial aviation appointed in 1926, its emphasis was to teach the business elements of the arising “new industry” to all those eager to acquire “knowledge of the airplane and its potentialities as an agency of commerce”. [ 43 ] In the opening of the first chapter, Woolley describes the state of commercial aviation in the eyes of the nation at the time:

“Within the past two years America has awakened to the presence of a new and vital agency in transportation; a medium, which, although at present only slightly understood, holds promise of development beyond grasp of the most vivid imagination. True, the airplane as a vehicle has been known to us for more than one-quarter century but its adaptation to commerce dates only from the termination of the World War and its economic worth had not been definitely established previously to 1926.” [ 44 ]

1926 was a watershed year for commercial aviation. It would be one of many key milestones, and one that would see the first economic successes.

As mentioned, 1926 would be the year of what has been referred to as the first true commercial passenger flight in the United States. Additionally, the Federal Aviation Association’s most recently published chronology dates back to that year (FAA Historical Chronology, 1926-1996), beginning with the Air Commerce Act. And in 1976 – coinciding with the nation’s bicentennial – the U.S. Post Office would issue the Commercial Aviation Commemorative Stamp marking the “golden anniversary of commercial aviation in the United States” with the description “Commercial Aviation, 1926-1976″ ( See the first day of issue cover for this stamp ).

The Commercial Aviation Commemorative Stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1976

1926 being the year the “CAM” carriers would began carrying U.S. Air Mail under contract, the planes shown on the 1976 stamp were the first two to do so: the Ford-Stout AT-2 (upper) and Laird Swallow (lower).

Other groups, such as the Aviation Historical Society, would also honor 1926 as the true beginning of U.S. commercial aviation (as shown below).

An enveloper cover from the Aviation Historical Society Honoring the 50th Anniversary of U.S. Commercial Aviation

In addition to numerous legislative and general infrastructure advancements, there were other factors as well that led to the growth of passenger airtravel in the United States beginning in the mid-1920s. One of those can be attributed to the contributions of automobile pioneer Henry Ford. In 1925, Ford began a commercial cargo airlines called the Ford Air Transport Service and would be awarded the CAM6 and CAM7 airmail routes. Although not receiving one of the initial five routes, he would actually be the first of the carriers to begin operation in 1926, staking the company’s claim as “the world’s first regularly scheduled commercial cargo airline.” [ 45 ] He would soon abandon that venture however in favor of focusing on airplane manufacturing, selling its routes to Stout Air Services (which was eventually acquired by National Air Transport (NAT) who in turn became part of United Airlines).

It was in two primary areas that Ford would help shape the history of commercial aviation. The first of those was in airplane technology, through the introduction of the Ford Trimotor – the first all-metal, multi-engine transport in the United States and the first plane designed primarily to carry passengers rather than mail (having room for 12 passengers and cabins with high ceilings that didn’t require stooping).

The Trimotor’s three-engine design made for significant improvements in relation to speed and altitude – ultimately enabling it to become the first plane to be used for transcontinental passenger service, as well as the first plane to fly over the South Pole. Dubbed the “Tin Goose”, a total of 199 Ford Trimotors were built between 1926 and 1933. And its impact on commercial aviation was immediate, with the design helping to make passenger airtravel potentially profitable for the first time. It would be labeled as the “first successful American airliner” and said to represent a “quantum leap over other airliners.”

Ultimately, the Great Depression ended Henry Ford’s short career as a major figure in American aviation. He would pass the baton to companies like Boeing, who introduced the Boeing 247 in 1933, and the Douglas Aircraft Company whose DC-3 would revolutionize air transportation for the next decades (along with Wright Aeronautical and Pratt and Whitney who would dominate the engine market for years to come). In the meantime, however, United Aircraft and Transport Corporation took over the Ford airmail routes in 1929 and the Ford Airplane Manufacturing Division closed for good in 1933. Though similar to the way Ford’s durable Trimotor planes seemed to last forever (One Trimotor 5-AT, built in 1929, was still being used in Las Vegas for sightseeing in 1991), [ 46 ] so was Ford’s impact on commercial aviation long lasting. Not only did the advancements in plane construction help move the industry forward, but Ford was also instrumental in a second important breakthrough: gaining the American public’s trust when it came to flying.

When the public saw that Ford had its name on airplanes used for passenger service, it gave an entirely new level of legitimacy to the idea of safe and reliable passenger airtravel. As famous 1920s and 1930s actor Will Rodgers would comment, “Now you know that Ford wouldn’t leave the ground and take to the air unless things looked pretty good to him up there.” [ 47 ]

Ford’s involvement in airplane manufacturing, coupled with the government legislation of 1925-1926, provided a stamp of approval in the eyes of the public and for the first time ever passenger flight began to be seen not as merely a novel and risky venture, but as a new and trustworthy way of travel. In fact, just as Ford traveled around the country through his “Reliability tours” to promote the idea that the automobile had come of age in America, so did he do the same for the airplane – in part through the aerial version of his Reliability Tours, the Ford National Reliability Air Tour.

CHARLES LINDBERG

The Airline Handbook describes the bold and revolutionary accomplishment:

“In planning his transatlantic voyage, Lindbergh daringly decided to fly by himself, without a navigator, so he could carry more fuel. His plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, was slightly less than 28 feet in length, with a wingspan of 46 feet. It carried 450 gallons of gasoline, which constituted half its takeoff weight. There was too little room in the cramped cockpit for navigating by the stars, so Lindbergh flew by dead reckoning. He divided maps from his local library into thirty-three 100-mile segments, noting the heading he would follow as he flew each segment. When he first caught sight of the coast of Ireland, he was almost exactly on the route he had plotted, and he landed several hours later, with 80 gallons of fuel to spare. Lindbergh’s greatest enemy on his journey was fatigue. The trip took an exhausting 33 hours, 29 minutes and 30 seconds, but he managed to remain awake by sticking his head out of the window to inhale cold air, by holding his eyelids open, and by constantly reminding himself that if he fell asleep he would perish. In addition, he had a slight instability built into his airplane, which helped keep him focused and awake. Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Field, outside of Paris, at 10:24 p.m. Paris time on May 21. Word of his flight preceded him and a large crowd of Parisians rushed out to the airfield to see him and his little plane. There was no question about the magnitude of what he had accomplished. The age of aviation had arrived.” [ 48 ]

As a young U.S. Air Mail pilot hired in 1925 by the Robertson Aircraft company (that would later become American Airlines) to fly the CAM-2 mail route between St. Louis and Chicago, Lindbergh was suddenly thrust into the spotlight as an American hero, as well as the first person to ever be in New York one day and Paris the next. It captured the imagination of the public in relation to the capabilities of modern airtravel, as well as the imagination of investors. Though many in years past had invested in aviation ventures that had failed, suddenly there was a rush to Wall Street to invest in aviation, with investments in aviation stocks tripling between 1927 and 1929.

After his legendary feat, Lindbergh was faced with enthusiastic crowds wherever he went. He gave numerous speeches, participated in parades, and received many awards, including the Distinguished Flying Cross medal from President Calvin Coolidge, using his status as an American icon and international celebrity to further aviation along with other noble causes.

THE GUGGENHEIMS

As mentioned, the Guggenheim family also served as an important catalyst in the rise of commercial aviation. And this involved far more than generous financial contributions. The philanthropic efforts of the Guggenheims were far reaching and brought together some of the brightest minds in the nation. Tom Crouch writes again in Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age :

“Daniel Guggenheim began to discuss the possibility of expanding his involvement, spending several million dollars on the creation of a fund that would support civil aviation. Father and son, the Guggenheims discussed the idea with everyone from Orville Wright to Secretary of Commerce Hoover and President Coolidge. The decision to forge ahead had been made by January 1926. The Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics would support aeronautical education; fund research in “aviation science”;promote the development of commercial aircraft and equipment; and “further the application of aircraft in business, industry and other economic and social activities of the nation.” Running it would be a blue-ribbon panel of leading figures from aviation, business, finance, and science, including the inventor of the airplane and a Nobel laureate in physics.” [ 49 ]

The fund would go on to create schools of aeronautics at major universities, including Stanford, MIT, and Harvard, among several others. The impact would be far reaching with respect to the research conducted, the technological discoveries made, and perhaps most importantly the development of the graduates – from pilots to engineers to meteorologists.

One of those graduates was Herbert Hoover, Jr., son of 31st President of the United States Herbert Hoover and eventual Secretary of State under President Eisenhower. Hoover won a fellowship from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund to study aviation economics at the Harvard Business School, and would focus on the economics of radio in the aviation sector. He would use that education to help Western Air Express, in cooperation with Thorpe Hiscock of Boeing, to develop the first ever air-to-ground radio while serving as Western’s communication chief.

Under his guidance, Western would also establish a system capable of guiding radio-equipped aircraft along 15,000 miles of airways across the Western U.S. And in 1930 he would be elected president of Aeronautical Radio Inc. – a non-profit alliance between Western Air Express, Boeing and American Airways that represented the airline industry’s single licensee and coordinator of radio communication outside of the government. This selection led to Time Magazine putting Hoover on the cover of its July 14, 1930 edition.

Herbert Hoover Jr (middle) with Western Air Express pilots Jimmie James (left) and Fred Kelly (right)

Even beyond education, the Guggenheim fund would make major contributions to the aviation industry. An example was its revolutionary breakthroughs in relation to “blind flight”, addressing the problems faced by pilots in three main areas: point-to-point navigation while in fog or above clouds, maintaining straight and level flight via instrument readings, the usage of ground facilities for take off or landing assistance in poor visibility conditions.

In September 1929, a young U.S. Army lieutenant named James Doolittle took off from Mitchell Field in New York on a 15-minute test flight. When his wheels touched down, he had reached a major milestone in aviation history, being the first plane in history to take off, fly a precise flight path, and land, with its pilot not using any visual cues outside of his cockpit instruments. The instruments that made this possible included a very accurate barometer, an artificial horizon and gyroscope, and a radio direction beacon – all developed through research at the Guggenheim Full Flight Laboratory. Within the next decade, instrument flying would become routine for all airlines. One of the congratulatory telegrams sent to Harry Guggenheim upon this achievement came from famed explorer Robert E. Byrd, who sent the message from his camp on the Antactic ice cap. At the end, he added “I know of nothing that has done as much for the progress of aviation as your organization.” [ 50 ] The Guggenheim Fund would end in 1930, concluding very much in the same spirit of the U.S. government’s previous involvement in helping aviation to forge ahead. Daniel Guggenheim would state, “With commercial aircraft companies assured of public support and aeronautical science equally assured of continual research, the further development of aviation in this country can best be fulfilled in the typically American manner of private business enterprise.” [ 51 ]

Though the fund would cease, however, its impact would live on – as would the Guggenheim’s work through other avenues. The Guggenheim foundation for example established such entities as the Cornell-Guggenheim Aviation Safety Center at Cornell University where important research took place in relation to collision avoidance, crash fire protection, and other aspects of safety improvement. The Guggenheim Medal fund would be awarded annually to individuals making exceptional contributions to aviation, with the first going to Orville Wright. And the Guggenheims sponsored much of the research of Dr. Robert J. Goddard, upon which all modern developments of rockets and jet propulsion was based.

Arguably though, the greatest impact of the Guggenheim legacy remains that of the decision to provide funding to a courageous group of aviation trailblazers and the establishment of the world’s first “model airline”. Together, the Guggenheims and Western Air Express would pioneer the first semblences of airtravel as we know it today – year round, regularly scheduled, overland service using landplanes – and pave the way for the first truly self sustaining and economically successful model in commercial aviation.

The legacy and impact of the Guggenheim Fund would live on many years past the end of the model airline experiment, as would that of Western which would go on to establish many industry firsts [ N 8 ] . In fact, Western would eventually take on the label of “America’s senior air carrier” as well as the “oldest continuously operating airline in the US” [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ N 9 ] at the time of its acquisition by Delta in 1986. Even as it became part of the Delta family, the innovations and progress of Western, much of which was derived from its earliest years, [ N 10 ] would carry on not only in spirit but in everyday business operations. To this day, for instance, Delta continues Western’s Salt Lake City hub operations, which is the same location from where that first passenger flight of Western Air Express took place in 1926 – an event that would set in motion the first true success story in commercial aviation.

When history is remembered, what generally emerges to the forefront are not necessarily the “firsts”, but the events, discoveries. and individuals that had the most powerful influence in shaping the future.

Christopher Columbus was not the first to discover America. Yet the fact that his name looms larger in history than many of those who proceeded him – including the Vikings led by Leif Erickson, the waves of Carribean explorers like the Taino tribe, and potentially even Monks like St. Brendan who it is believed made the journey in the sixth century – is because of the unparalleled impact of his explorations. Christopher Columbus opened up a new continent to Spain and, ultimately, all of Europe. His discovery had a profound and lasting impact on the trade routes of the day. And his voyages would ultimately reshape the known world.

Similarly, Henry Ford did not invent the automobile and yet his name is synonymous with it. For it is he who changed the landscape of a nation, and world, by making the automobile an affordable reality to the average person. Through use of the assembly line technique of mass production, and by lowering costs as opposed to pocketing profits from the resulting cost savings, Ford’s company would go on to lead the American industry to produce three quarters of all automobiles in the world by 1950.

Taking transportation to the next level would be the Wright Brothers, even though technically they were not the first to fly manned aircraft. In addition to those lifted by hot air balloon and airships such as Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier who flew the first manned free balloon flight on November 21, 1783, there are others who flew heavier-than-air crafts in the rough form of the modern day airplane beginning in the early 1800s. And while many of the pioneers who did so would make significant contributions to the science and eventual realization of powered flight (which the Wright Brothers themselves would even rely upon), the Wright Brothers hold a special place in history because of the unique impact they had on airplane design. While other early inventors experimented with the shifting of a persons weight to control or steer the plane, for instance, the Wright Brother’s revolutionary invention of “three-axis control” would make fixed-wing powered flight truly possible for the first time ever and would be adopted universally in aircraft design moving forward. Tom D. Crouch, who as mentioned holds the position of senior curator of aeronautics at the National Air and Space Museum, described why the invention of the Wright Brothers is given precedence as first to achieve “powered, heavier-that-air flight” over the work of competing inventor Augustus Moore Herring, saying “Herring’s 1898 motorized machine represented nothing more than the culmination of the hang-gliding tradition. Having made his brief powered hops, he found himself at a technological dead end.” [ 54 ]

In a similar way, there were various early attempts to launch the world of commercial aviation, ranging from paid sightseeing flights on crop dusters to a handful of failed airboat ventures. But perhaps the most significant breakthrough came via a great American success story – that of the Guggenheims and Western Air Express, and of the movement of the mid-1920s that involved one of the greatest collaborations in human history. From the legislation that laid the early groundwork to the humble beginnings of a two-passenger inaugural flight in an open cockpit atop mail sacks to the investments made by many, this is a story of American ingenuity, of the unique American balance between government and private enterprise, and of the spirit of the American West.

These truths are emphasized not merely in the spirit of American patriotism, but more so in the spirit of the model airline experiment – that the success of one might benefit many (also an American principle). For the hope is that the blueprint discovered here might lead others to greater successes, whether nations or groups of individuals or other generations of Americans. After all, it is poetic that the movement which brought forth the kind of advancements that would connect the world as never before, was done through such a great collaboration of people. The profound words found on the website for the Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company seem most fitting in this regard, describing one of the true motivations that drove the two brothers to pursue their dream of building their flying machine: “Seen from above, the artificial boundaries that divide us disappear. Distances shrink, the horizon stretches. The world seems grander and more interconnected.” [ 55 ] And Western Air Express pilot Al DeGarmo said of his friend and famed Hollywood actor Will Rogers, “He believed air travel was key to this country’s growth. Air travel was something everyone would be doing one day, he said, and it would help break down differences that divided nations.” [ 56 ]

Today the Wright Brothers are recognized as among the greatest of the pioneers of flight – though it wasn’t until after they died that they were finally credited over such men as Samuel Pierpont Langley as being the first to build a heavier-than-air craft capable of manned powered flight. It sometimes takes time for the truest heroes of history to be appropriately honored. Hopefully this story of the beginning of commercial aviation will be told with greater attention paid to these great men and women who took the baton from the Wright Brothers and brought aviation to the next stage of development. For while the Wright Brother’s sought and achieved sustainable (and controlled) flight, these pioneers of the mid-1920s sought and achieved sustainable economic growth that would make it possible to take the innovations of the Wright Brothers and turn them into the means of forever changing the world of global transportation.

- ^ It is worth noting that the Guggenheims didn’t expect to be paid back for this loan and in fact told Western Air Express founder Harris Hanshue this was more in the nature of a grant. However, Hanshue refused to accept the money as a gift and insisted on inserting a clause into their agreement that stipulated Western was to repay the loan within eighteen months at 5% interest. Hanshue also put up some $100,000 in public-utilities securities to guarantee the loan.

- ^ Robert Serling writes on pages 6-7 of The Only Way to Fly: The Story of Western Airlines America’s Senior Air Carrier , “…there is one thing to be noted about all these early airline efforts [prior to 1926] – every one involved the use of flying boats, not landplanes. Airfields throughout the United States, with few exceptions, were too primitive, inadequate, and actually dangerous to warrant confidence on the part of the public or airmen themselves. Not until the government – prodded by the growing demand for regular air mail service-established lighted airways and modest airport improvements did scheduled air transportation become feasible between inland cities.”

- ^ It should be noted that the road to prosperity for Western and the industry in general was not only filled with successes, but involved setbacks as well. One particularly dark chapter in the history of the commercial aviation industry occurred during the 1930s, though the Air Mail Act of 1930 that consolidated all of the air mail routes to only three companies (United Airlines, TWA, and American Airlines) and the resulting investigation of a 1930 meeting (the so-called Spoils Conference) involving postmaster general Walter Brown and representatives of the three airlines to whom he would later award the air mail routes. This would be referred to as the Air Mail Scandal and Air Mail Fiasco by the American Press as the actions under the new legislation were accused by many of being a corrupt effort of conspiracy to monopolize the air mail. Though allegations relating to this were never proven, there was enough room for suspicion to convince President Franklin D. Roosevelt to cancel the contracts altogether and have the Army Air Corps take over the service. This would not only negatively impact the airline industry in general, but would have disastrous results in many ways since Air Corps’ airplanes could not meet the demands of night flight, let alone bad weather. There were many deadly crashes and lost lives, until finally later the same year Congress passed the Air Mail Act of 1934, which returned most air mail routes to the major airlines as well as gave some routes to smaller airlines.

- ^ While Western Air Express greatly benefitted from infrastructure improvements and other provisions of the government, it was able to attain profitability without any direct government subsidies. It also received a low interest 5% loan of $155,000 to be paid back over 2 years courtesy of the Guggenheim Fund in 1927, which enabled it to purchase three Fokker passenger planes. Even after the first of its two annual loan payments was made to the Guggenheims in 1928, WAE was still able to report a net profit of nearly $700,000 on $1.4 million in total revenue (most of this though still coming from mail revenue at the time).

- ^ This cooperative agreement between five competing airlines marked the first time in the history of aviation that major airlines combined their experience and finances for the development of an experimental plane to meet future needs. And the joint effort was a giant success. It is estimated that had each of the five airlines carried out development efforts separately, it would have cost them approximately $2,000,000 more, the equivalent of four additional experimental planes.

- ^ US Department of Commerce statistics report 1,176,858 passengers flew on US commercial airliners in the year 1938. American operated scheduled air carriers would also set all-time records that year for the number of miles flown and passengers and express carried, according to reports received by the Civil Aeronautics Authority (as cited in Popular Aviation , September 1939. p.26).

- ^ Some of this power given to government would be rescinded in 1978 through the Airline Deregulation Act passed by the U.S. Congress which removed government control over fares, routes and market entry (of new airlines) from commercial aviation. While this regulatory control was probably needed in the early years of US aviation, deregulation in 1978 had a positive impact of driving airfare to more affordable rates, and consequently dramatic growth in passengers flown. As Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer pointed out in 2011, “In 1974 the cheapest round-trip New York-Los Angeles flight (in inflation-adjusted dollars) that regulators would allow: $1,442. Today one can fly that same route for $268.”

- ^ Western Airlines was the first to develop and use air-to-ground radio (1929), the first to have weather reporting stations (1927), first to fly 10 years without injury to a passenger (1926-1936), the world’s first profitable air transportation system (1926), the first airline in history to pay a cash dividend to its stockholders (1927), the first “regularly scheduled, year-round, overland passenger service” in the U.S. (1926), the first to offer in-flight meals (1928), the first to have flight attendants in U.S. domestic service (1928), the first to introduce commercial four-engine transports, the first to feature airborne television, the first to offer limousine service, and the first to provide log books for passengers.

- ^ At the time of Western’s merger with Delta, there was some controversy between Western and United Airlines over which was officially the oldest. United was originally formed by United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, a partnership between Boeing Airplane Company and Pratt & Whitney. The larger corporation officially established an operating division known as United Air Lines on July 1, 1931. That same year, however, it would purchase Varney Airlines. While Western preceded Varney in relation to the introduction of passenger service, Varney beat out Western (by a margin of 11 days) in flying “fixed routes” with respect to airmail delivery.

- ^ Many of the learnings and advancements of the Model Airline experiment became an ongoing part of Western’s business operations moving forward. As Robert J. Serling writes in The Only Way to Fly , “The so-called Model Airway experiment never really ended; rather, it gradually was absorbed into Western’s normal operations, and the lessons learned were incorporated into the airlines procedures and policies.”

- ^ A Global Mindset for Commercial Aviation’s Next Century . Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ^ Daniel Guggenheim quoted in C.V. Glines, “The Guggenheims: Aviation Visionaries,” Aviation History 6 (November 1996)(as cited in Tom D. Crouch, Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age , (New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition (November 17, 2004)), p.238).

- ^ Richard O. Hallion, Legacy of Flight: The Guggenheim Contribution to American Aviation , University of Washington Press. 1977. p. 88.

- ^ The National Aviation Hall of Fame: Harry Guggenheim , Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Robert E. Dallos, “Pioneer Western Pilot Recalls Day It All Began : Airline Has Come a Long Way Since 1st Flight in 1926”, Los Angeles Times , April 06, 1986

- ^ Beating the Odds: The First Sixty Years of Western Airlines , Western Airlines, 1985

- ^ Delta Flight Museum: Western Historical Timeline , Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Hallion, p. 87.

- ^ “Western Airlines Marks Anniversary of S.L. Flight”, Salt Lake City Tribune , April 17, 1944, p.16.

- ^ “S.L. Will Commemorate First Commercial Flight”, Salt Lake City Tribune , December 12, 1934, p.36.

- ^ Nevada Aerospace Hall of Fame: Harris M. Hanshue . Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- ^ “Officials, Public Laud ‘Unique’ Air Terminal”, Salt Lake City Tribune , June 18, 1961, p.14.

- ^ Robert J. Serling, The Only Way to Fly: The Story of Western Airlines America’s Senior Air Carrier , (Garden City, New York:Doubleday & Company, 1976), p.40.

- ^ Claude Gray, “The Old West”, The Vintage Airplane , February 1976, p.12.

- ^ Serling, p.76.

- ^ Ibid, p.94.

- ^ Grant quote from Bowie, “Weather and The Airplane,” p.17 (as cited in Hallion, p. 97).

- ^ James G. Woolley and Earl W. Hill, Airplane Transportation (Hollywood, Calif.:Hartwell, 1929), p.45.

- ^ Ibid., 69.

- ^ Ibid., foreward.

- ^ League of Nations, Inquiries into the Economic Administration and Legal Situation of International Aerial Navigation (geneva: League of nations, 1930), p.8; Ronald Miller and David Sawer, The Technical Development of Modern Aviation (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1968) p.13 (as cited in Tom D. Crouch, Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age , (New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition (November 17, 2004)), p.209).

- ^ Crouch, p.209-210

- ^ Carlos A. Schwantes, Going Places: Transportation Redefines the Twentieth-century West, (Indiana University Press, 2003), p. 8.

- ^ Woolley, p.21.

- ^ “Five Airlines Unite to Finance Super-Ship” , Berkeley Daily Gazette , March 19, 1936, p.8

- ^ Nick Komons, Bonfires to Beacons: Federal Civil Aviation Policy under the Air Commerce Act, 1826-1938 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, 1978), 66 (as cited in Crouch, p.239.).

- ^ Andrew R. Thomas, Soft Landing: Airline Industry Strategy, Service, and Safety , Apress. 2011, p.22.

- ^ Popular Aviation , September 1939. p.26

- ^ Global Airline Industry Program: Airline Industry Overview , Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Airlines For America . Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Charles Perrow, Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies (Princeton University Press 1999), p.125

- ^ Airline Handbook Chapter 1: Brief History of Aviation . Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Woolley, foreward.

- ^ Ibid., 1.

- ^ Henry Ford, Ford Motor Company Founder And Aviation Pioneer”

- ^ Century of Flight: Commercial Aviation 1920 to 1930 . Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Nick Komons, Bonfires to Beacons: Federal Civil Aviation Policy under the Air Commerce Act, 1826-1938 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Transportation, 1978), 67 (as cited in Crouch, p.249.).

- ^ Crouch, p.237.

- ^ Telegram, Byrd to HFC, Sept. 27, 1929, DGF Papers, box 2 (as cited in Hallion, p. 124).

- ^ Delta Flight Museum: Family Tree . Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- ^ Crouch, p.220 (as cited in First in Flight? Americanscientist.com retrieved 7-4-14)

- ^ The Wright Story , Wright Brothers Aeroplane Co. retrieved 7-4-14.

- ^ Beating the Odds: The First Sixty Years of Western Airlines , Western Airlines , 1985, p.5.

The History of Commercial Flight: How Global Travel Took off

This is how commercial flights went from being exclusively for the wealthy to the mainstream and affordable option they are today.

DALLAS - Flying has become the transport of choice for business travelers and holidaymakers across the globe and is now considered one of the fastest, most convenient, and safest forms of long-distance travel.

But how did commercial flights go from being exclusively for the wealthy to the mainstream and affordable option they are today? Artemis Aerospace guides us through the different decades of air travel and how it has shaped modern-day living.

Listen to this article:

The First Commercial Flight

The first ever passenger flight took off in May 1908 when Wilbur Wright carried Charles Furnas just 2000 feet across the beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Just one year later, the first airline in the world, the German airship company DELAG, was founded.

In 1914, the world’s first scheduled passenger service, an airboat piloted by Tony Jannus, set off from St. Petersburg, Florida, and landed at Tampa, around 17 miles away. The service only ran for four months, but it had unlocked the appetite of those keen to tap into the novelty of air transport.

A New Era of Aviation

However, it wasn’t until the 1920s that commercial flights carrying paying passengers started to become commonplace with the introduction of the multi-engine airplane, the Lawson C-2, which was specifically built to carry passengers.

During this time, more and more start-up airline carriers were being established, some of which are still in operation today. These include KLM in the Netherlands (1919), Colombia’s Avianca (1919), Qantas in Australia (1920), and Czech Airlines (1923).

Aircraft from this period would land frequently to refuel and fly at lower altitudes due to unpressurized cabins. This made traveling by plane noisy, cold, and expensive. Flying times were lengthy, and turbulence was frequent. Passengers regularly experienced air sickness, and many airlines hired nurses to reduce anxiety and tend to those affected.

In 1935, one of the world’s oldest airlines, Qantas, operated its first international passenger flight, traveling from Brisbane to Singapore. From there, British-owned Imperial Airways connected this flight to the UK. This was to set the wheels in motion for creating a regular travel route between Australia and the UK in the coming decades.

Despite flying being incredibly dangerous and extremely expensive during this period, it was still a fashionable way to travel for the rich. According to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the number of airline passengers grew from just 6,000 in 1930 to nearly half a million by 1934; the aviation industry was well on its way to becoming hugely important to the global economy.

Innovation That Revolutionized Air Travel

The introduction of the Douglas DC-3 in 1935 also had a big impact on the future of commercial flight. The propeller-driven airliner was a larger and much improved aircraft compared to its predecessors. Faster and more reliable, it could carry up to 32 passengers and had a cruising speed of 207 mph with a range of 1500 miles. This made it popular with well-established airlines, including Delta, TWA, American, and United, who soon added the aircraft to their fleets.

During the 1940s, the onset of WWII meant commercial aviation developments slowed considerably. However, by the end of the decade, the industry was heading towards a new era as Pan Am began operating its fleet of Boeing 307s, which featured the first-ever pressurized cabin.

This transformed air travel for passengers, allowing them to enjoy a comfortable experience at an altitude of 20,000 feet. Major airlines were now ramping up their advertising spending and offering travelers smooth journeys to far-flung destinations and business hubs, including Pan Am’s iconic New York-London route.

The Golden Age of Air Travel

The 1950s and 1960s heralded the age of jet engine aircraft, and with it came an upsurge in commercial flights, airline carriers, and international flying routes.

Commercial air travel was booming, and major airlines were fiercely competitive, offering passengers more and more inflight perks, including lavish silver-service meals and fine wines.

Pan Am was a front-runner in pioneering and marketing the very best air travel had to offer. It was the first airline to fly worldwide and introduced ground-breaking changes to the industry, such as adding jet aircraft to their fleets and utilizing computerized reservation systems.

In the 1960s, work began on creating the world’s first supersonic aircraft and what would eventually become an iconic symbol of commercial flight, the Concorde. Offering transatlantic flights in just 3.5 hours, the aircraft was a hit with business travelers and royalty alike. However, tickets were extremely expensive and only a privileged few could afford to travel via Concorde.

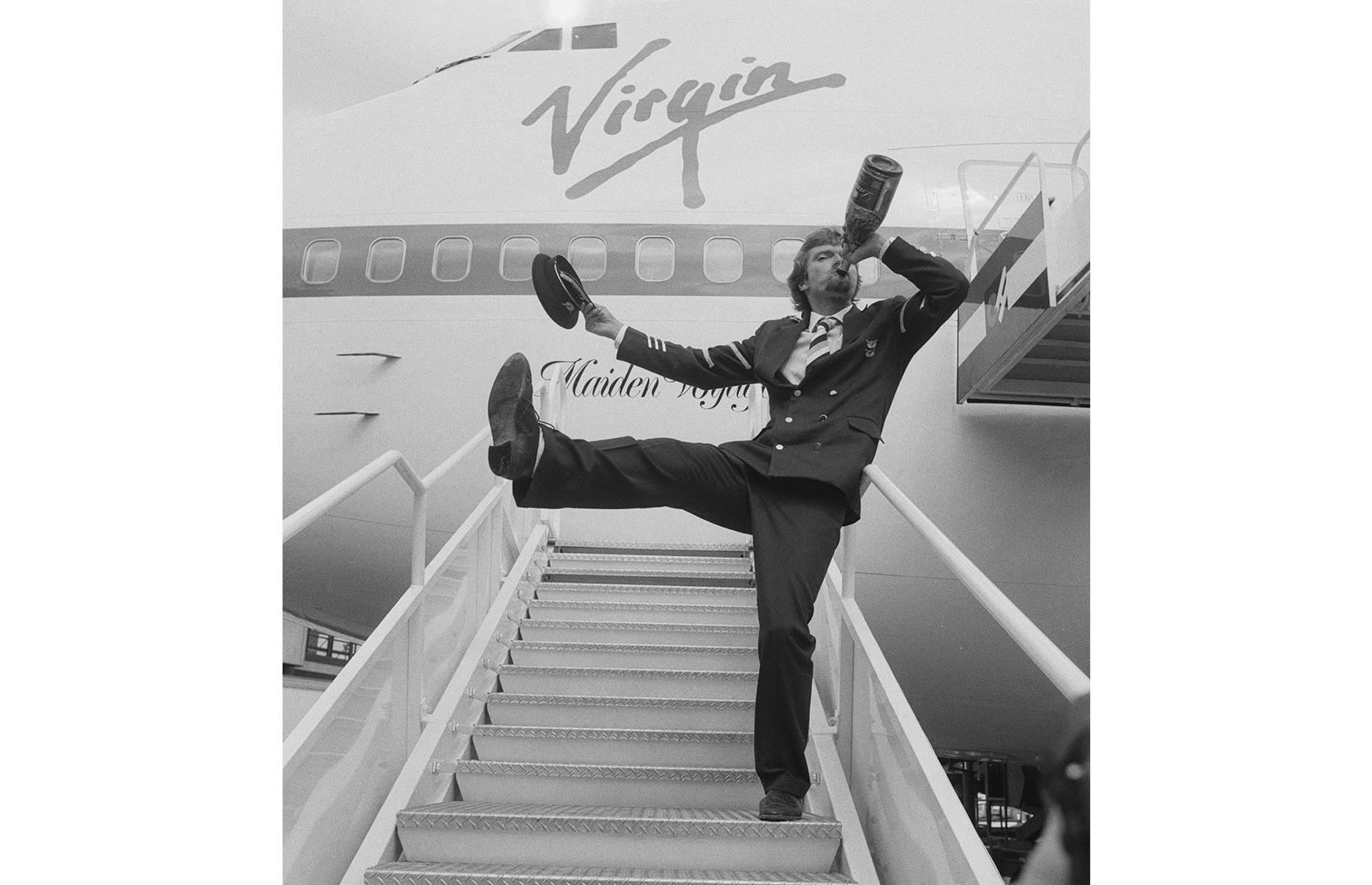

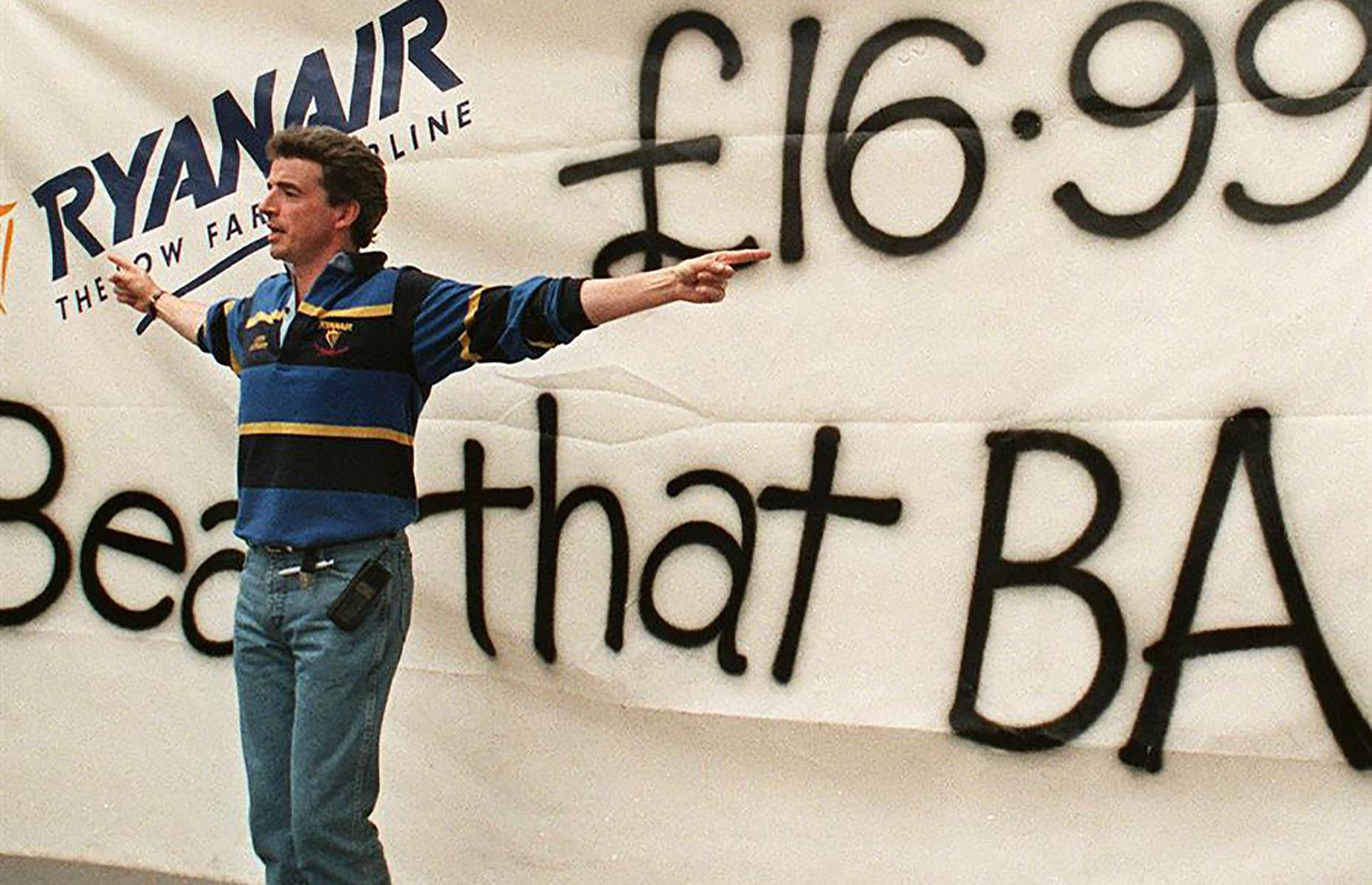

The Rise of the No-frills Airline