Flight Testing Of Air Force’s New Nuclear-Armed Cruise Missile Well Underway

There have been at least nine flight tests of stealthy Long Range Stand Off missile prototypes, including one with a mock nuclear warhead.

FranticGoat

The U.S. Air Force has conducted at least nine flight tests of prototypes of its future nuclear-tipped AGM-181A Long Range Stand Off cruise missile, or LRSO. This includes a test where a prototype missile successfully flew by itself along a set route while loaded with a special test article designed to act as a surrogate for a live W80-4 nuclear warhead .

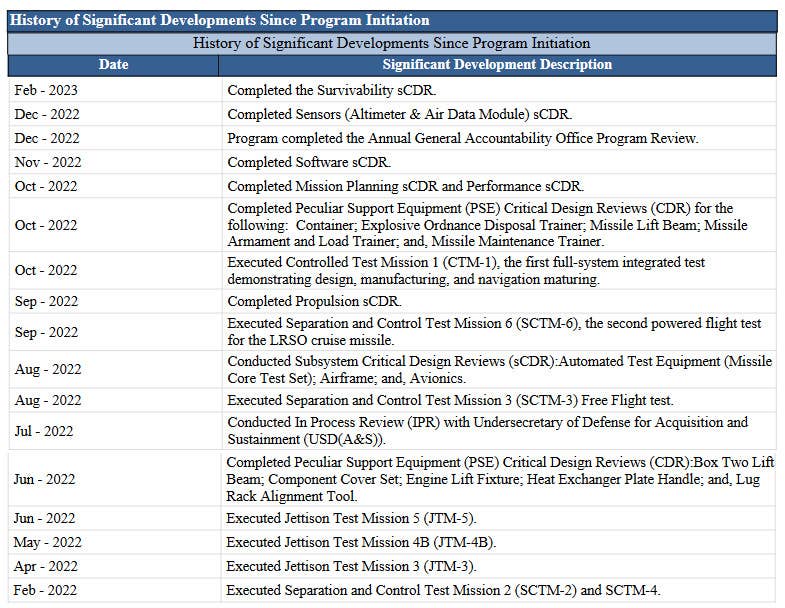

Details about the LRSO flight testing milestones were included in a 2022 Selected Acquisition Report (SAR) for the program, as well as other reports earlier this year. Air & Space Forces Magazine was the first to report on the information from the SAR, which is dated December 2022, but that the Pentagon only released last month.

The Air Force announced in 2020 that it had chosen Raytheon to develop the AGM-181A, which is now set to replace its nuclear-armed AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missiles (ALCM). Details about the LRSO's design remain limited, but it is a member of the larger Long Range Strike (LRS) family of systems that also includes the B-21 Raider stealth bomber. LRSO will be highly survivable, including having a stealthy airframe, and it is possible that its range may be significantly greater than its predecessor. The ability to communicate with the launch platform and other command and control assets, and the ability to sense threats in its environment and avoid them are also real possibilities, existing already on other conventional cruise missiles .

"LRSO conducted nine successful major flight tests demonstrating the LRSO's ability to: 1) safely separate from the B-52H aircraft; 2) Weapon flight surface deployment, engine operations, and flight control actuations; and 3) Capture controlled flight after employment from the B-52H aircraft," according to the SAR. The B-52H is set to be one of the two delivery platforms for the AGM-181A, the other being the future B-21 Raider stealth bomber .

Though the Pentagon's 2022 acquisition report describes all nine of the test events as flight tests, only a portion of them actually involved missiles flying on their own. There were also a number of so-called captive carry sorties, where the missile remained on the aircraft carrying it the whole time. This is done to make sure there are no safety or other problems stemming from just loading it onto its launch platform and flying it in position. There were unpowered release tests, as well, to demonstrate that the missile could separate from the aircraft onto which it was loaded without issue.

"The testing in CY [calendar year] 2022 culminated in four successful powered-flight tests, including a Controlled Test Mission (CTM-1) that demonstrated maturity of the design, associated manufacturing processes, and the navigation system performance," the 2022 SAR for LRSO adds. "CTM-1 demonstrated safe missile separation from the B-52, missile flight control deployment, engine start and extended range operation, warhead-arming flight discrimination events, collection of flight environment and fire-down sequence data for the warhead, and advanced navigation along a mission planned route using an operationally relevant Mission Data File. All test objectives were met."

No mention is made of how many unsuccessful flight tests there may have been.

"Current calculations indicate that when four or more stores are loaded on the rotary launcher [in the B-52's bomb bay], the stores clash with the fuel tank," the report does note. However, the "risk is fully mitigated and closure is pending receipt of final documentation. Projected closure: May 2023."

"Nuclear Safety Cross Check Analysis (NSCCA) must be in place to support timely nuclear certification of LRSO software," it also says. Mitigation plan in place and on track. Projected closure: June 2023."

The CTM-1 flight test, which took place in October 2022, was actually previously disclosed in a report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, back in June. However, GAO did not expressly describe it as a flight test at that time, saying only that "the program tested a system-level integrated prototype in October 2022."

The Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) also disclosed details about LRSO flight testing in its most recent Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan , which was released in April. That report further added the missile involved in one test, very likely CTM-1 based on the accompanying details, was loaded with a special test version of the W80-4 nuclear warhead.

"The LRSO and W80-4 Life Extension Program joint test teams completed the first powered flight test of a LRSO Cruise Missile with W80-4 Warhead released from a B-52 aircraft. The missile successfully released from the aircraft, powered its engine, and executed all in-flight maneuvers," according to NNSA. "A Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) team developed the warhead test asset, an Environmental Test Unit. The Environmental Test Unit successfully executed all pre-arm/pre-release criteria and collected environmental data for the duration of the flight. This is a significant milestone for the joint program and first collection of representative LRSO free flight data, used to populate the W80-4 STS [stockpile-to-target sequence], define environmental specifications, inform design decisions, and validate computational models."

Details about this test unit are scant, but there are no indications that it was a live warhead. "Environmental Test Unit 1" is "an instrumented test asset that provides captive carriage environmental data for warhead qualification," Sandia National Laboratories said previously about a similar-sounding W80-4 test article.

The Air Force's current AGM-86B nuclear cruise missiles are armed with W80-series warheads. Versions of this warhead were also found on the now-retired air-launched AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile (W80-1) and nuclear-armed and the sea-launched BGM-109A Tomahawk Land Attack Missile-Nuclear (TLAM-N; W80-0).

The older W80-0/1 warhead designs are so-called dial-a-yield designs, reportedly with two settings, five kilotons and 150 kilotons. The W80-4 effort is described as a Life Extension Program (LEP) that involves refurbishing and modernizing existing W80-1 variants.

"The W80-4 LEP will... enhance safety, security, and reliability," according to NNSA . "Key design requirements of the W80-4 include use of the existing insensitive high explosive design, incorporation of modern components and safety features, extensive use of non-nuclear component technology developed for other LEPs, and parallel engineering with the USAF on the warhead-missile interface."

The W80-4 warheads are not expected to have different yield options than their predecessors.

As it stands now, the date for when the Air Force expects to achieve initial operational capability with the LRSO is classified. A decision about whether to begin low-rate initial production of the missiles is expected in 2027.

LRSO entering service will be dependent, at least in part, on the availability of W80-4 warheads. For its report in June, DoE told GAO that it did not expect to mature all the relevant technologies for those warheads until Fiscal Year 2025. As of May, NNSA said it expected to deliver the first production W80-4 in 2027. Its April report added that "the W80-4 LEP is on track to support fielding the Air Force’s scheduled LRSO cruise missile initial and final operational capability dates."

The Pentagon acquisition report does peg the estimated LRSO program acquisition cost, as of December 2022 and based on the expected purchase of 1,020 missiles in total, at just over $16 billion. Sustaining the missiles over a 30-year lifespan is expected to cost another $7 billion or so.

What we do know now is that the LRSO flight test program has been very active and successful, putting the Air Force ever closer to fielding its next nuclear-armed cruise missile.

Contact the author: [email protected]

The Air Force’s New Stealth Cruise Missile Is a Go. But Do We Need It?

Let's make sense of the controversial Long Range Stand Off.

- The Long Range Stand Off (LRSO) missile will arm Air Force strategic bombers.

- LRSO will have the range to make even B-52s effective nuclear platforms.

The U.S. Air Force has awarded Raytheon a contract to develop the service’s next-generation stealth cruise missile. The Long Range Stand Off (LRSO) missile will arm B-21 Raider and B-52 Stratofortress bombers, allowing them to launch missiles against targets without penetrating enemy airspace.

The Air Force flies two types of nuclear-capable bombers: the B-2 Spirit and B-52H Stratofortress. (The B-1 Lancer is no longer capable of carrying nukes and is now a conventional munitions-only bomber.) The bombers are armed with two kinds of nuclear weapons: the B61 and B83 free-fall gravity bombs, as well as the AGM-86B Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM).

While free-fall bombs typically have large explosive yields (the B83 has a yield of 1,300 kilotons, for example), the bomber must overfly the target. On the plus side, bomber crews can cancel the drop at the last minute. Bombers can launch the ALCM at targets up to 1,500 miles away, but enemies can shoot the cruise missile down. A cruise missile also takes up to 2 hours to reach its target, and it can’t be recalled during that time.

In the 1970s, nuclear bombers were on the verge of extinction. Advances in long-range air defense missiles and high-speed interceptors such as the Soviet MiG-25 made big, lumbering bombers like the B-52 sitting ducks in enemy airspace. But cruise missiles— effectively small, unmanned airplanes powered by turbofan engines, and low-flying to evade radar—allow bombers to launch against enemy targets long before they’re under threat.

A B-52, for example, could fire a salvo of ALCMs far from Soviet airspace, targeting enemy air defense installations. The B-52 could use ALCMs to blast a path to its main target, nuking MiGs on runways, radar sites, and enemy headquarters while remaining safely out of reach. Once the path is clear, the B-52 can then infiltrate enemy airspace and finally drop a high-yield gravity bomb on the target.

Cruise missiles are critical to the usefulness of bombers in a nuclear war. Without them, bombers would probably have to withdraw from the nuclear triad , removing a key capability—the ability to recall or cancel a nuclear strike—from America’s nuclear toolbox.

The Air Force has relied on the AGM-86B Air Launched Cruise Missile since the 1970s. Like any aging technology, the missile is increasingly difficult to maintain. The ALCM also lacks radar-evading stealth technology that would make it more difficult to detect by enemy defenses, increasing its likelihood of reaching its target.

LRSO, then, will be a stealthy missile with about the same range of 1,500 miles. The missile will also use the W80-4 thermonuclear warhead, a refurbished version of the older W80-1 thermonuclear warhead, with a customizable yield of 5 to 150 kilotons .

The new cruise missile is controversial. In 2015, a number of key U.S. Senators asked then-U.S. President Barack Obama to cancel the LRSO , saying the new missile was unnecessary given the development of the B61-12 nuclear gravity bomb and the forthcoming B-21 Raider bomber. Others warn that LRSO is “unnecessary” and “destabilizing.”

So, does the Air Force need its new stealth cruise missile? If it wants to keep the bomber leg of the nuclear triad , then the answer is yes. A B-21 Raider without cruise missiles would have to overfly every target to destroy it, a requirement that would dangerously expose the bomber and potentially add hours to a combat mission.

If such a bomber is tasked with destroying an enemy communications or headquarters site that transmits orders to launch more missiles, it could arrive at the target too late to interrupt the enemy’s plans— if it arrives at all.

In an ideal world, the U.S. could bargain with the other nuclear powers to gradually reduce—and even eliminate—nuclear weapons worldwide. An adversary must, however, recognize that America’s nukes are a threat in order to want to bargain to get rid of them.

Building LRSO isn’t the end of the world ... but using them is. Between those two points, the U.S. can trade nuclear missiles away in exchange for missiles in Russia or China targeting this country.

🎥 Now Watch This:

Kyle Mizokami is a writer on defense and security issues and has been at Popular Mechanics since 2015. If it involves explosions or projectiles, he's generally in favor of it. Kyle’s articles have appeared at The Daily Beast, U.S. Naval Institute News, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, Combat Aircraft Monthly, VICE News , and others. He lives in San Francisco.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} Pop Mech Pro .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

Every Single Cell in Your Body Could Be Conscious

How to Live Forever, or Die Trying

The Army & Navy Working Together Defense Missiles

How Russia Copied America’s Deadliest Missile

North Korea Sends “Poop Balloons” Into South Korea

Plane Flown by 'Ace of Aces' Pilot Finally Found

The F-35 Is Still One of the Safest Planes

The Air Force’s Upcoming “Doomsday Plane” Replacem

Meet the Marines' New Kamikaze Drone

Did Russia Launch a Weapon Near a U.S. Satellite?

A Groundbreaking Discovery For Interstellar Travel

Sunday, June 16, 2024

Official Publication of the Navy League of the United States

- Featured Story

STRATCOM Commander Affirms Need for Sea-Launched Cruise Missile-Nuclear

By Richard R. Burgess, Senior Editor

ARLINGTON, Va.—The operational commander of the nation’s nuclear arsenal has reiterated to Congress the requirement for a sea-based nuclear-tipped cruise missile.

Testifying Feb. 29 before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Air force General Anthony J. Cotton, commander, U.S. Strategic Command called for development and deployment of the Sea-Launched Cruise Missile – Nuclear (SLCM-N), a program called for in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR).

Cotton called for continued modernization of the U.S. nuclear deterrent forces, including the SLCM-N.

“While our legacy systems continue to hold potential adversaries at risk, it is absolutely critical we continue at speed with the modernization of our nuclear triad, including land-based ICBMs [intercontinental ballistic missiles], the B-21 [bomber], the B-52 [bomber], the Columbia-class submarine, the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile, and LRSO [Long-Range Stand-Off weapon],” Cotton said.

The 2018 NPR called for the United States to “pursue a nuclear-armed SLCM, leveraging existing technologies to help ensure its cost effectiveness. SLCM will provide a needed non-strategic regional presence, an assured response capability. It also will provide an arms-control-compliant response to Russia’s non-compliance with the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty, its non-strategic nuclear arsenal, and its other destabilizing behaviors.”

The Biden administration, with support of Democratic representatives in the Congress, has opposed development of the SLCM-N, citing what they said was the cost of the program, the adequacy of the current nuclear deterrent arsenal, and a risk to nuclear stability.

Despite the administration’s opposition, Congress authorized $25 million in the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act for research for the SLCM-N. The administration did not request funding for research for the SLCM-N in its fiscal 2024 budget request, but Congress approved establishing the SLCM-N as a program of record.

The fiscal 2024 NDAA “authorized the Sea-Launched Cruise Missile – Nuclear, or SLCM-N, as part of the program of record with initial operating capability by 2034, said Jill Hruby, National Nuclear Security Administration administrator, speaking Feb. 1 at the 2024 Nuclear Deterrence Summit. “SLCM-N will provide a new low yield at sea nuclear deterrent. NNSA is working closely with the Navy and Office of Secretary of Defense to develop a recommendation for Congress by early March on the details of the SLCM-N program.”

The Navy used to field a nuclear-armed version of the Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile — the TLAN-N — which was retired about 2010.

- Recent Posts

- Q&A: Ashley Johnson, Technical Director, Naval Surface Warfare Center, Indian Head Division - June 5, 2024

- Q&A: Kelly Robertson-Slagle, Director of Development, Charles County, Maryland - June 5, 2024

- Winds Damage Navy TH-73 Training Helicopters at Whiting Field - May 30, 2024

- Air Warfare

- Cyber (Opens in new window)

- C4ISR (Opens in new window)

- Training & Sim

- Asia Pacific

- Mideast Africa

- The Americas

- Top 100 Companies

- Defense News Weekly

- Money Minute

- Whitepapers & eBooks (Opens in new window)

- DSDs & SMRs (Opens in new window)

- Webcasts (Opens in new window)

- Events (Opens in new window)

- Newsletters (Opens in new window)

- Events Calendar

- Early Bird Brief

- Digital Edition (Opens in new window)

Nuclear Arsenal

The us navy’s new nuclear cruise missile starts getting real next year.

MINOT AIR FORCE BASE, N.D. — The Pentagon intends to create a program of record for a new nuclear-armed, submarine-launched cruise missile in its next budget request, with the goal of deploying the weapon in 7-10 years, according to a senior defense official.

Speaking on condition of anonymity during a visit to Minot Air Force Base this week, the official noted that the department is going through an analysis of alternatives, or AOA, process for the weapon, which was first announced during the rollout of the Nuclear Posture Review .

“We requested $5 million in FY20, which Congress gave us. There’s nothing in the ‘21 budget because we’ll just continue to use the $5 million to do the AOA,” the official explained. “But in FY22, I hope that you’ll see a budget request that will begin the program of record for the sea-launched cruise missile.”

“You put these on submarines, the Russians won’t know where they are,” the official added. “They’ll hate it. They’ll absolutely hate it.”

As part of the Nuclear Posture Review, rolled out in early 2018, the Trump administration said it would seek two new nuclear capabilities: a low-yield warhead for the submarine-launched ballistic missile, and a sea-launched nuclear-capable cruise missile. The first goal is complete, with the warhead, known as the W76-2, deployed for the first time in late 2019.

The official said the department is still sorting how much money the program might cost, but pointed to the estimated price tag for the Long Range Standoff Weapon — or LRSO, a new air-launched cruise missile — as a rough estimate. That weapon is projected to cost the Defense Department about $8 billion to $9 billion and a similar amount for the National Nuclear Security Administration, which is charged with developing the warhead, the official said.

“Do you put it on a surface ship? Do you put it on a submarine? Do you use a new missile or an existing missile? How far does it have to travel? We’re looking at all of this. And then you also have to look at the concept of operations. How you want them to operate? Do you store the weapons on the sub all the time, or do you bring them into port and bring them in a crisis?” the official said.

Strategically, adding the cruise missile would allow the nuclear-armed Navy to go from 12 ships to 20 or 30, which would be “huge” in changing the strategic calculus for China and Russia, the official noted.

The official emphasized that the weapon doesn’t need to be a brand-new design, saying: “It doesn’t have [to] be a big deal” to design and procure.

“The SLCM [submarine-launched cruise missile] doesn’t have to be a big deal. Could be the same warhead. We’re going to look into that,” the official added.

A conventional Tomahawk weapon has a rough range of 1,250–2,500 kilometers, and the range on the new SLCM would likely be longer, as a nuclear warhead weighs less than a conventional payload. The Navy is already investing in its Next Generation Land Attack Weapon, which could provide a more updated system on which to base the SLCM. The warhead could be a modification of the W80-4, the warhead from NNSA that will be paired with the LRSO.

Critics of the idea argue that another nuclear weapon adds little to the arsenal, while eating into a naval budget that is already under strain.

“A new SLCM would be a costly hedge on a hedge,” said Kingston Reif of the Arms Control Association. “The United States is already planning to invest scores of billions of dollars in the B-21 [bomber], LRSO and F-35A [fighter jet] to address the [area-access/area denial] challenge. The Navy is unlikely to be pleased with the additional operational and financial burdens that would come with re-nuclearizing the surface or attack submarine fleet.”

Additionally, “arming attack submarines with nuclear SLCMs would also reduce the number of conventional Tomahawk SLCMs each submarine could carry,” Reif said.

Regardless of the details for the weapon, the official expects the Pentagon is 7-10 years away from deploying the new SLCM — and that’s if Congress backs the plan. Democrats have raised objections to the Trump administration’s plans for new nuclear weapons before, but ultimately did not block the W76-2 project from moving forward.

“I don’t know if Congress is going to make a big deal about it or not because there’s really no money involved” in fiscal 2021, the official said. “But it is a new weapon system, and unlike the W76-2, where you’re replacing a large warhead for a small warhead, here you’re actually introducing more deployed capabilities. But again, it’s 7-10 years.”

When the Nuclear Posture Review was rolled out, officials emphasized that the SLCM could be used as a bargaining chip in arms control negotiations with Russia. Despite a number of arms control agreements being on the ropes, the official this week again argued that the SLCM could “give us some leverage to bring [Russia] back to the arms control table.”

Aaron Mehta was deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent for Defense News, covering policy, strategy and acquisition at the highest levels of the Defense Department and its international partners.

More In Nuclear Arsenal

Missile Defense Agency satellites track first hypersonic launch

The flight the satellites tracked was the first for mda’s hypersonic testbed — a platform for various hypersonic experiments and advanced components..

Space Force picks three firms to compete for $5.6B in launch contracts

The national security space launch contracts open competition for the space force’s launch enterprise, which to date has been dominated by spacex and ula..

Space Force’s Resilient GPS program draws skepticism from lawmakers

Lawmakers say the space force's plan to use proliferation to boost gps resiliency may be flawed..

Air Force, Space Force unveil tool for AI experimentation

The services want to use the tool to better understand how ai could improve access to information and to gauge whether there’s demand within the force..

House bill funds new tranche of Philippines, Taiwan military aid

The house's fy25 state department funding bill shows that the u.s. has a continued interest in keeping china at bay in the indo-pacific., featured video, "young men don't lose brothers well." vietnam recon veterans recall those who didn't come home.

What Type of Savings Accounts Are Out There? — Money Minute

Real world conflicts inform military leaders on the future of electronic warfare

The future of electronic warfare and cyber threats | Defense News Weekly Full Episode 6.8.24

Trending now, no 30-year-old drone wingmen: us air force eyes regular cca overhauls, will russia’s navy get the 50 ships it expects this year, eyes on ukraine, demand for tanks is bubbling up in eastern europe, romania’s second patriot system operational after drone-destroying drill.

A Nuclear Sea-Launched Cruise Missile Sooner, Rather than Later

By Eli Glickman

“The current situation in Ukraine and China’s nuclear trajectory have further convinced me that a deterrence and assurance gap exists,” argued Admiral Charles Richard–then Commander of U.S. Strategic Command–in 2022 when he endorsed a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile capability (SLCM-N) as “necessary to enhance deterrence and assurance.”

After conducting its Nuclear Posture Review, the Biden Administration cut the SLCM-N. Congress, however, has continued to fund SLCM-N, and House Republicans led a push during the markup process for the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act to formally make SLCM-N a program of record.

The program, however, is likely to cost too much and come too late. Admiral Michael Gilday, then Chief of Naval Operations, estimated that the warheads for SLCM-N would cost $31 billion alone. Furthermore, when it was originally scrapped by the Biden Administration, senior Department of Defense officials estimated that, even if the program was fully funded, SLCM-N could not be delivered until 2035, much too late to deter Chinese nuclear escalation in a potential invasion of Taiwan that could occur before the end of the decade. Given the rigidity of defense procurement timelines, Congress should direct the Department of Defense to explore alternative capabilities to stand-in for SLCM-N in the near-term.

Luckily, the pieces are already there. As of 2022, the U.S. Navy had a stockpile of 4,000 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs)—long range cruise missiles fired from surface ships and submarines. Open-source estimates indicate that the U.S. also has roughly 1,900 nuclear warheads kept in reserve. The United States could therefore constitute a SLCM-N capability by modifying a portion of these warheads to decrease their explosive yields and fitting them onto existing TLAMs. This is very likely to be technically feasible, as the Navy used to have nuclear-tipped TLAMs, which were retired in 2013.

A reconstituted nuclear-tipped TLAM would check all the boxes for deterrence and assurance that SLCM-N might check. Kyle Balzer of the American Enterprise Institute argued that SLCM-N, if deployed on nuclear-powered fast-attack submarines, would be deployable across the world, highly survivable, and be capable of penetrating China’s anti-access/area denial perimeter in the Indo-Pacific. A nuclear TLAM deployed on a fast-attack submarine would deliver the same capability. Moreover, a tactical nuclear weapon delivered by a cruise missile would be an inherently more credible deterrent than larger, ballistic-launched strategic nuclear weapons because it would be easier to use without inviting devastating retaliation. A TLAM is a suitable delivery platform for meeting these needs in the near-term, although a more advanced cruise missile might be necessary farther in the future.

Opponents of a SLCM-N contend that it would exacerbate escalation risks and could make nuclear weapons ‘more usable.’ This claim, counterintuitively, helps explain why tactical nuclear weapons are important tools. Simply put, a weapon that is more usable is a more credible deterrent because America’s adversaries would be more likely to believe the U.S. would actually use it. Brad Roberts, the director of the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, has argued that Chinese and Russian theories of victory consider nuclear weapons to be “instruments of coercion, blackmail, and brinksmanship” which could be used in a limited fashion to signal resolve and “persuade the United States and/or its allies to back down.” Given its credibility advantage, SLCM-N—or a nuclear-armed TLAM—would signal to China and Russia that neither country could gain an advantage from executing a coercive limited nuclear strike. A nuclear-tipped TLAM is therefore a credible deterrent and an effective near-term stand-in for SLCM-N.

Opponents also argue that deploying SLCM-N would reduce the availability of vertical launch tubes for conventional TLAMs on fast-attack submarines. That concern notwithstanding, Admiral Gilday expressed his confidence in the Navy’s ability to certify and deploy SLCM-N on its vessels. Moreover, it would be very difficult for U.S. adversaries to know whether a given Virginia-class submarine had nuclear TLAMs on it, so the Navy could deploy a relatively limited number while still achieving the desired deterrent effect. Indeed, despite the opportunity cost associated with conventional cruise missiles, General Mark Milley, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, testified that he supported SLCM-N, as did Admiral Christopher Grady, the current Vice Chairman.

Congress should take the lead on investigating the utility of a nuclear-armed TLAM. Each year’s National Defense Authorization Act typically includes Committee Reports—prepared by the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, respectively—in which members of Congress can include directive items of special interest which direct defense officials to take certain actions. In this year’s Committee Reports, members of Congress should include items of special interest directing the relevant Department of Defense and National Nuclear Security Administration authorities to determine whether a nuclear-armed TLAM is technically feasible in the near-term and capable of filling existing deterrence requirements. Specifically, Congress should direct items of special interest on this matter to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Matters, the Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, the Secretary of the Navy, and the directors of each of the three Department of Energy weapons labs—Los Alamos, Lawrence Livermore, and Sandia.

Armed with information about the technical feasibility and military utility of a nuclear-tipped TLAM, Congress can move quickly to authorize and appropriate funds for the development, procurement, and deployment of this capability. Time is of the essence, and a nuclear-armed TLAM may be the United States’ optimal weapon for filling existing deterrence and assurance gaps.

Eli Glickman is a rising senior at the University of California, Berkeley, where he studies political science and public policy.

The views expressed in this piece are the sole opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Center for Maritime Strategy or other institutions listed.

- Force Design

- Industry & Innovation

- Strategy & Doctrine

Donate to the Center for Maritime Strategy

Your investment in the center for maritime strategy supports the u.s. sea services by empowering policy-driven maritime security research, advocacy, and education..

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

- My View My View

- Following Following

- Saved Saved

US attack sub, Canada navy patrol ship arrive in Cuba on heels of Russian warships

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Dave Sherwood; Additional reporting by Marc Frank; Editing by Frances Kerry and Cynthia Osterman

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

Iran rebukes G7 statement over its nuclear programme escalation

Iran called upon the Group of Seven on Sunday to distance itself from "destructive policies of the past", the Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Nasser Kanaani said, referring to a G7 statement condemning Iran's recent nuclear programme escalation.

- Election Integrity

- Immigration

Political Thought

- American History

- Conservatism

- Progressivism

International

- Global Politics

- Middle East

Government Spending

- Budget and Spending

Energy & Environment

- Environment

Legal and Judicial

- Crime and Justice

- Second Amendment

- The Constitution

National Security

- Cybersecurity

Domestic Policy

- Government Regulation

- Health Care Reform

- Marriage and Family

- Religious Liberty

- International Economies

- Markets and Finance

The Nuclear Sea-Launched Cruise Missile: Worth the Investment for Deterrence

Patty-Jane Geller

Former Senior Policy Analyst, Center for National Defense

Key Takeaways

The SLCM-N would provide a regionally present, sea-based, survivable option needed to fill a gap in U.S. nuclear deterrence capabilities.

While air-based nuclear weapons remain a critical part of U.S. strategy, a sea-based regional nuclear missile can bolster these existing regional capabilities.

Because nuclear deterrence is both the Navy and DOD’s number one mission, resourcing the SLCM-N should take priority.

INTRODUCTION

As part of the United States’ effort to modernize its nuclear forces to confront the growing nuclear threat, the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) recommended restoring the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM). The United States previously deployed a nuclear SLCM (or SLCM-N), called the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile-Nuclear (TLAM-N) during the Cold War, but has since retired the capability. The NPR proposed the SLCM-N to adjust U.S. posture in response to Russia and China’s ongoing buildups of their regional, nonstrategic nuclear capabilities. The SLCM-N would provide a regionally present, sea-based, survivable option needed to fill a gap in U.S. nuclear deterrence capabilities. It would also improve allied assurance of U.S. extended deterrence commitments and add stability to an imbalance of regional nuclear forces that exists in both the European and Indo-Pacific theaters. Fielding the SLCM-N would require overcoming practical hurdles, including redeploying nuclear weapons on forward-deployed Navy ships, reallocating limited naval resources, and added costs. But ultimately, solving these challenges is feasible given the Navy’s previous experience deploying these weapon systems. Considering the immediacy of the nuclear threat and increased potential for limited nuclear use, investing in the SLCM-N is worth overcoming any practical difficulties

The SLCM-N is a theater-range cruise missile armed with a nuclear warhead that can be launched from surface ships or submarines. During the Cold War, the United States deployed the TLAM-N on surface ships and submarines from 1983 to 1991 as part of its strategy to deter a Soviet attack on Europe. In particular, the TLAM-N supported the strategy of deploying nonstrategic nuclear weapons to link conventional forces in Europe with the U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal. Because they were deployed in theater on submarines and surface ships, they helped assure allies that the United States’ extended nuclear umbrella would hold in the event of a Soviet attack. Additionally, the TLAM-N played an important role in deterring Soviet conventional or nuclear attack at a “middle rung” on the escalation ladder. While the United States deployed strategic systems to deter major strategic attacks and tactical systems such as nuclear artillery to deter conflict at the lowest rung of the escalation ladder, the TLAM-N helped fill this middle level, especially after the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty banned intermediate-range ground-launched missiles. Due to their survivability on stealthy attack submarines, the TLAM-N helped convince the Soviets that initiating conflict at this middle level of the escalation ladder would be met with an equivalent assured response.

After the Cold War ended, President George H.W. Bush withdrew the TLAM-N from service. It was kept in storage until 2010 when President Barack Obama’s NPR officially retired the capability. This decision was based on an assessment of the strategic environment at the time to be far more benign than the threats facing the United States today. But since then, the strategic environment has drastically shifted. While the United States dismantled its nonstrategic nuclear capabilities, Russia and China expanded them. Currently, Russia maintains at least 2,000 tactical nuclear weapons that are integrated into its doctrine of escalating conflict to compel its adversaries to back down. China is also advancing its theater-range missiles and rapidly growing its nuclear stockpile.

Rather than maintain the same nuclear posture meant for the previous strategic environment, the 2018 NPR recognized that U.S. posture must adapt to reflect the changed threat and proposed the development of two supplemental capabilities to increase the diversity and flexibility of U.S. nuclear forces. The first capability is a low-yield warhead for submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM), the W76-2, which was deployed in early 2020. The second, long-term supplemental capability is to restore the SLCM-N within 10 years. The 2018 NPR required the Navy to conduct an Analysis of Alternatives for development of the SLCM-N. The AoA will answer questions on SLCM-N development and concept of operations, including the platforms on which SLCM-N will be deployed, the number of missiles to acquire, and whether the SLCM-N will utilize old TLAMs, technology from the LongRange Standoff Weapon program (LRSO), or new technology. To advance the discussion, this paper will assume that the SLCM-N can be deployed on attack submarines such as the Virginia-class and surface ships such as Zumwalt-class destroyers, as suggested by then commander of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) General John Hyten in 2018.

>>> The Nuclear Posture Review Must Account for a Growing Chinese Nuclear Threat

For fiscal year (FY) 2022, Congress fulfilled President Joe Biden’s budget request of $5.2 million for the Navy to begin SLCM-N research and development efforts and $10 million for the National Nuclear Security Administration to begin work on an accompanying warhead, which will be an alteration of the W80-4 warhead currently being life-extended for the LRSO.7 The SLCM-N will likely take 7 to 10 years to deploy. While the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the SLCM-N might cost about $9 billion over 10 years, this assessment is very preliminary, and a more accurate cost will depend on the results of the AoA.9 The 2018 NPR called for reducing costs by taking advantage of existing technologies, so the extent to which SLCM-N utilizes technology from the LRSO currently under development or the Tomahawk missile has the potential to drive down costs.

STRATEGIC CONTEXT

The 2018 NPR proposed the SLCM-N to address the threat environment, which has changed dramatically over the past decade. The 2010 NPR claimed Russia to be no longer an adversary, and at that time there was still hope for China to rise peacefully. The 2010 NPR also established nuclear force modernization plans in line with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) that the Department of Defense (DOD) is in the early stages of pursuing today. This current force structure reflects the more benign strategic environment of 2010, but Russia and China have significantly built up their nuclear forces since then. As STRATCOM commander Admiral Charles Richard recently noted , “For the first time in our history, the nation is on a trajectory to face two nuclear-capable, strategic peer adversaries at the same time, who must be deterred differently.” In addition, North Korea continues to improve its nuclear capabilities despite denuclearization efforts. Deterrence at a nonstrategic or regional level is becoming particularly challenging as Russia and China develop their nonstrategic nuclear capabilities while unconstrained by New START and North Korea bolsters its nuclear arsenal. While adversaries grow and advance their nuclear forces, U.S. nuclear posture remains static, as modernization plans consist of replacing existing systems on a one-to-one basis. Additionally, compared to adversaries’ nonstrategic arsenals, the United States only deploys a couple hundred B61 gravity bombs overseas that are not counted under New START.

To compensate for a perceived inferiority of conventional forces, Russia has sought to build a “deterrence ladder” that would enable it to employ nonstrategic nuclear weapons should the United States or NATO inflict unacceptable damage to its conventional forces. The 2018 NPR Russia maintains a diverse arsenal of delivery systems capable of carrying these nonstrategic weapons, ranging from short-range missiles to anti-ship cruise missiles, torpedoes, artillery, and potentially the defensive S-400 system.

China is also undertaking what Admiral Richard described as “a breathtaking expansion” of its nuclear forces. While China is completing a strategic nuclear triad accompanied by an assured second-strike capability, its advancement of regional nuclear forces means, as Richard noted , “they can do any plausible nuclear employment strategy regionally.” The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force deploys several road- and rail-mobile ballistic missiles with medium and intermediate ranges that can strike an array of targets across the Indo-Pacific with precision. Most missiles are dual-capable, and the DF-17 missile might be able to carry a nuclear-capable hypersonic weapon. Additionally, China’s H-6K bomber can carry nuclear weapons, and China’s sea-based capabilities will improve with the development of the JL-3 SLBMs. These forces enable the Chinese to backstop their conventional forces in the region. For instance, should China decide to forcefully take Taiwan, it can use its regional nuclear forces to coerce the United States and constrain U.S. response options.

North Korea’s advancing nuclear capabilities will also increase the challenge of deterring nuclear use at the regional level. Despite diplomatic efforts, the Kim regime continues to produce fissile material to build more nuclear weapons. It maintains an arsenal of short- and medium-range ballistic missiles that can strike a range of targets in the Indo-Pacific. The presence of two nuclear-armed states increasingly hostile to the United States in the Indo-Pacific presents an increasingly complex strategic deterrence challenge to the United States.

THE CASE FOR THE NUCLEAR SLCM

The nuclear threat to the United States is unprecedented. Russia and China’s nuclear buildups indicate that they believe they can gain an advantage over the United States. So long as Russia and China continue to advance their regional nuclear forces and the United States simply maintains the same force posture designed for a different threat environment, this imbalance in regional nuclear forces will persist. As a result, the United States must take action to respond to this change in threat environment—doing nothing will jeopardize U.S. deterrence. The rest of this paper analyzes the 2018 NPR’s proposal to develop the SLCM-N in response to this change in threat, which the 2018 NPR states will provide a “needed nonstrategic regional presence” that will “strengthen the effectiveness of the sea-based nuclear deterrent force.”

What matters in determining a sufficient nuclear deterrent is the perceptions of adversaries of U.S. willingness to use nuclear force, not what the United States believes is necessary to deter. The argument for the SLCM-N is not necessarily that current U.S. forces are incapable of deterring Russian, Chinese, and North Korean regional nuclear threats, as it is impossible to know exactly why adversaries decide not to take certain actions. But because there is evidence that adversaries may believe they can gain an advantage by growing their nuclear forces or even employ their regional nuclear forces to compel the United States to back down in an ensuing conflict, more is needed to ensure certainty in the minds of adversaries that the United States can and will retaliate to even limited nuclear use. The SLCM-N has several unique attributes that would contribute to the credibility and flexibility of U.S. deterrence and allied assurance.

First, the SLCM-N can be deployed to the European or Indo-Pacific regions, increasing flexibility by providing the president with a proportional, credible response option. The SLCM-N will be deployed on sea-based platforms—likely destroyers or submarines—that can operate in theaters of conflict as opposed to U.S. strategic nuclear forces such as intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) located in the U.S. homeland or SLBMs deployed from nuclear ballistic missile submarines further out at sea. Russian and Chinese nonstrategic or regional nuclear buildups and strategies indicate that they may incorrectly perceive the United States to be reluctant to retaliate against a limited strike using a strategic nuclear weapon, which may disproportionally escalate the conflict further, and instead back down.24 While the United States may be confident in its ability to respond using strategic systems, what matters for deterrence is what adversaries perceive. Deploying a regional nuclear system that can more proportionally respond to limited nuclear employment can convince adversaries with more certainty of U.S. willingness and capability to respond to even a limited nuclear attack.

The need for a regional nuclear capability is especially acute in the Indo-Pacific theater, where the United States does not forward deploy any nuclear weapons. To respond to nuclear employment at the lower rungs of the escalation ladder in the Indo-Pacific, the United States would need to respond with a strategic nuclear weapon or relocate tactical weapons to the theater. While one cannot definitively say whether adversaries will view U.S. ICBMs, SLBMs, and strategic bombers as a credible deterrent against their tactical nuclear weapons, Russia and China’s massive regional nuclear force buildups indicate that they believe they can gain an advantage over the United States—an advantage that the United States must seek to limit. As the threat of regional nuclear forces grows, the SLCM-N can convince an adversary with more certainty that any nuclear use will be met with a proportionate U.S. response. The key is affecting threat perceptions in an enemy’s mind that the United States has viable options all along the escalation ladder that it can employ, not a quantitative matching of warheads.

Critics argue that the existing nuclear triad suffices to deter the growth in China and Russia’s nuclear capabilities, especially since the United States deployed the W76-2 low-yield SLBM in 2020. However, keeping U.S. force posture “as is” will allow this imbalance to persist in regional nuclear forces—which is profoundly destabilizing. The SLCM-N provides a unique capability to deter this growth in threat because it is nonstrategic, not limited to New START’s numeric caps, and can be forward deployed to directly deter adversary regional systems. The W76-2 provided a limited capability to have an option for a more proportional response to low-yield nuclear use in the short term, but more is needed to address the ongoing numeric growth in Chinese and Russian nuclear arsenals. Since it is not treaty-constrained, the SLCM-N enables the United States to add more deployed nuclear systems in the longer term to ensure the United States maintains sufficient capacity to deter the growing threat. Additionally, while the W76-2 provides a useful option to respond with a low-yield weapon, a regionally present system may be a more appropriate response for many limited-use scenarios than a launch from a strategic SLBM.

Second, because the SLCM-N will be deployed on a sea-based platform, it adds a more survivable option to U.S. capabilities below the strategic nuclear threshold. Currently, the United States’ only systems that can be forward deployed are air-based. In Europe, the United States forward deploys a couple hundred B61 tactical nuclear gravity bombs that can be deployed on either U.S. fighters or NATO dual-capable aircraft. However, the storage locations of these bombs are known and therefore vulnerable to Russian attack. Without enough warning time during a crisis, Russia can destroy those bombs, leaving the United States without this option. In the Indo-Pacific, the United States does not forward deploy any nuclear weapons to counter the growing Chinese nuclear threat. The United States can send nuclear-capable bombers to both regions during a crisis, but doing so requires long flight times and avoiding advancing air defenses. In fact, advancing adversary anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) environments indicates that adversaries may find U.S. air-based capabilities to lack credibility. According to a DOD report:

Given the major investment both Russia and China have made in A2/AD capabilities (especially advanced integrated air defense systems), each may come to believe it can effectively impede U.S. regional nuclear capabilities in executing their deterrence missions and thereby secure an exploitable coercive advantage. Dual-capable aircraft may be vulnerable, or perceived as vulnerable, to advanced defensive systems despite enhancements to their stealth and standoff features.

While air-based nuclear weapons remain a critical part of U.S. strategy, a sea-based regional nuclear missile can bolster these existing regional capabilities by more effectively operating against Russian and Chinese air defense systems. Sea-based, survivable submarines or even destroyers can operate in an extensive area and are difficult to find and destroy. Submarines are difficult to detect, and even Navy destroyers dispersed throughout the waters can make targeting difficult, especially if they have low observable characteristics, such as the Zumwalt-class. They can also operate in regional seas during both peacetime and crisis; they do not require long periods of time to deploy. As bombers, fighters, and their bases remain vulnerable to improving enemy A2/AD capabilities, the United States needs an additional regional nuclear option that is sea-based. The argument is not that the SLCM-N on sea-based platforms would be impervious to detection and attack compared to air-based nuclear forces, but rather that expanding options would improve the U.S. deterrence posture by making an adversary’s attack calculus more complicated.

Third, a SLCM-N’s cruise missile trajectory contributes to the U.S. ability to effectively hold targets at risk and complements ballistic missile options. For deterrence to be effective, the United States must ensure it can credibly hold targets at risk. Sea-launched cruise missiles fly at low altitudes, making them much more difficult to detect and intercept by adversary air defenses. The SLCM-N missile itself may incorporate advanced stealth capabilities if it is designed similarly to the LRSO. Ships can also launch multiple cruise missiles from multiple platforms simultaneously at independent targets, which complicates adversary air defenses and strengthens deterrence . This capability is similar to the ALCM, which also flies on a cruise missile trajectory, but is complementary, rather than redundant , especially considering adversary efforts to make airspace for bombers and fighters increasingly prohibitive. Additionally, unlike bombers that cannot remain in the same position for a long period of time without risk of being shot down, sea-based platforms can loiter close to targets. This attribute makes SLCMs particularly effective for striking time-sensitive targets. For instance, Russia, China, and North Korea all rely on the use of transporter erector launchers (TELs) to load and launch their mobile ballistic missiles. The SLCM-N can strike these targets promptly.

Therefore, the SLCM-N complements U.S. ballistic missiles—and the W76-2 low yield weapon in particular—by forcing the adversary to contend with missiles flying on both trajectories, in addition to missiles launched from both air and sea. This is not to argue that the United States cannot target time-sensitive targets such as TELs with other nuclear capabilities today or that a cruise missile would perform better than other capabilities. Rather, the SLCM-N increases the uncertainty and risk in adversaries’ behavior, as having to deal with both kinds of threats increases the demands on their advancing defense systems. Additionally, given the rapidly advancing threat and the time it takes to deploy new capabilities, commencing efforts now to increase the clarity in U.S. capability and will to respond is essential. Fielding the SLCM-N sends a strong signal that the United States will not tolerate regional aggression.

A regional, sea-based, cruise missile option would play an important role in both the European and Indo-Pacific theaters by convincing adversaries that attempts to escalate conflict will bring unacceptable risk. During the Cold War, the TLAM-N limited Soviet options for destroying U.S. forces deployed in Europe because even if the Soviets destroyed all the U.S. intermediate-range nuclear missiles, they could never be sure they could locate and destroy TLAM-Ns. In fact, the former commander of the U.S. Sixth Fleet, Vice Admiral J. D. Williams, recalled Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev remarking in a meeting with U.S. president George H.W. Bush that: “We have read every one of your submarine messages for ten years and have been unable to find or kill even one of them. We quit.” Now, the United States does not even deploy nuclear missiles to Europe—only B61 bombs, of which Russia knows the locations. With more survivable SLCM-Ns lurking in regional waters, Russia would have to think twice before escalating conflict to the point where it believes it can employ nuclear weapons and win.

The SLCM-N may play a more critical role in the Indo-Pacific theater. The dual-capable nature of China’s theater-range ballistic missiles combined with its advancing early-warning and command and control capabilities indicate that its nuclear forces could backstop a strategy to take Taiwan and compel the United States to back down during a crisis. China’s growing regional nuclear forces can constrain U.S. response options if the United States cannot effectively deter nuclear use at the lower end of the escalation ladder. According to Admiral Richard , “We’ll be the ones that are getting deterred if I don’t have the capability to similarly deter them.” It is important to note that effective deterrence depends on the successful completion of the modernization of the entire U.S. nuclear enterprise—including warheads, delivery platforms, and command and control systems—but as a part of that effort, the deployment of SLCM-Ns would fill an important gap that exists today.

SLCM-N AND ALLIED ASSURANCE

Allies may question the credibility of a U.S. response to limited employment of nuclear weapons in Europe or the Indo-Pacific using its high-yield, strategic nuclear forces. They may also question U.S. assurance commitments in general should the United States ignore the growing disparity with Russia and China. A nuclear capability that can be deployed in allies’ own regions can help reinforce that the United States is committed to the extension of its nuclear umbrella. Additionally, because it is sea-based, the SLCM-N can provide this benefit without the need for additional basing requirements. For this reason, NATO and Pacific allies would likely support the SLCM-N because it would improve deterrence of their aggressive neighbors without provoking domestic protests against nuclear weapons basing.

Maintaining allied confidence in the U.S. nuclear umbrella is critical as allies in Europe, and even more so the Indo-Pacific, become increasingly threatened by Russian and Chinese aggression. For instance, former commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson predicts that China could invade Taiwan within the next six years. At the same time, allies have reason to doubt U.S. commitments to extended deterrence, as the United States has sought to minimize its role in the world over the course of recent administrations. If the United States cannot modernize and maintain force levels of its own nuclear forces, allies will likely question the U.S. commitment to maintaining a nuclear force capable of deterring attacks against allies as well. Especially as allies such as Japan and South Korea have the technical capabilities to produce their own nuclear weapons, the United States must ensure its extended deterrence commitment remains credible. Developing the SLCM-N would aid in this effort.

SLCM-N AND STABILITY

Critics of nuclear deterrence argue that the SLCM-N will negatively impact stability with U.S. adversaries or start an arms race. China and Russia’s nuclear buildups threaten strategic stability. Their expanding and diversifying arsenals may provide both nations options to escalate conflicts in novel ways to which the current U.S. nuclear posture would be challenged to respond. This trend erodes deterrence; China and Russia may be more willing to take risks or even strike first as the credibility and efficacy of a U.S. response diminish. Adding the SLCM-N to the U.S. arsenal is therefore stabilizing because it would begin to rectify this imbalance.

The SLCM-N would also not start an arms race. Both Russia and China are already expanding their nuclear forces, as well as developing new and novel nuclear systems. The SLCM-N is a modest response to these significant expansions—and would not be the cause of them. Senior military leaders have also consistently emphasized that the United States does not intend to match either nation system for system; however, doing nothing means ceding an advantage to adversaries and reducing the United States’ ability to deter nuclear use. Russia and China will of course seek to disparage the SLCM-N effort as destabilizing. Doing so is in their interest since the SLCM-N would help close in on the advantages they seek—not because it would disrupt any existing strategic stability that Russia and China have already been acting to squander.

Another concern is that because the United States also deploys conventionally armed cruise missiles, Russia or China will confuse a U.S. conventional cruise missile with a nuclear one and launch a nuclear attack in response. However, the logic that a state can characterize a warhead based on missile trajectory is fundamentally flawed when it is technically possible to put a nuclear payload on any type of delivery system. This problem is also not unique to the SLCM-N, as countries have deployed dual-capable weapons for years and this mistaken escalation has never occurred . In an escalating conventional conflict, a Russian or Chinese preemptive nuclear strike after a U.S. cruise missile launch is implausible. Because Russia and China have clear assured second-strike options available after a U.S. missile launch, preemptively launching nuclear weapons and risking nuclear retaliation when a chance exists that the U.S. missile launch was conventional would not be a rational response.

SLCM-N AND ARMS CONTROL

Developing the SLCM-N may also play a useful role in future arms control negotiations. The NPR states that the SLCM-N “may provide the necessary incentive for Russia to negotiate seriously a reduction of its non-strategic nuclear weapons.” Russia has historically refused to even discuss its growing nonstrategic nuclear stockpile, much less negotiate on numbers and types. The Trump administration reached an agreement in principle for Russia to freeze all nuclear warhead growth in exchange for a short-term New START extension, but Russia reneged on that agreement after the U.S. 2020 election. Just as the U.S. deployment of Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Europe led to the INF Treaty in 1987, SLCM-N deployment—or even mere development—might compel Russia to the negotiating table. Deploying the SLCM-N may have a similar impact on China, which has thus far refused to participate in arms control discussions. Moreover, failing to respond to either nation’s nuclear buildups would likely decrease adversaries’ incentives for meaningful arms control by reinforcing their views that expanding their nuclear forces provides them a military advantage.

To be clear, the SLCM-N ought not be developed solely for the purpose of eventually being negotiated away. Given Russia and China’s regional nuclear force buildups, the United States should pursue the SLCM-N to help deter these threats. As General John Hyten testified when he was STRATCOM commander in 2018, “That [SLCM] capability is against the threat. However, that capability also gives our negotiators something to talk about. If you do not have something to talk about, it is very hard to sit down and negotiate. But it is not a bargaining chip because it is to counter the threat.”

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS TO ADDRESS

The case for the SLCM-N’s contribution to deterrence and national security is clear, as initially made by the 2018 NPR. The more important questions and concerns lie in the practical and feasibility implications of acquiring the SLCM-N. DOD will have to decide on which platforms it will deploy the SLCM-Ns, where any outcome would likely impact critical conventional naval missions. The Navy will also need to fit the SLCM-N into an already-constrained budget. While decisions such as platform, number of missiles, missile technology, and concept of operations have been examined in the AoA, this paper discusses potential options and outcomes to inform future policymaking. Ultimately, while developing the SLCM-N will require trade-offs, its development would provide a significant operational impact and is possible at a low cost.

The SLCM-N will likely be deployed on surface ships, attack submarines, or a combination of the two. In 2018, General Hyten specified that DOD would examine deploying SLCM-Ns on different types of submarines and the Zumwalt-class destroyer. While the Ohio-class, or future Columbia-class SSBNs, will likely not be an option, the Virginia-class attack submarines (SSNs) would be the likeliest candidate for submarine deployment. The U.S. Navy currently maintains 19 Virginia-class boats and will continue procuring about two more per year as the older Los Angeles-class SSNs retire. The Virginia-class has both vertical launch tubes and torpedo tubes that can carry the conventional TLAMs. Most Virginia-class boats being procured now and in subsequent years will carry the new Virginia Payload Module (VPM), an 84-foot-long section that can carry additional missile tubes, increasing capacity for missiles by about 76 percent. Given the Cold War experience of deploying SLCM-Ns, it is very plausible that new versions of this weapon could approximate the size of TLAMs and presumably fit in the VPMs or torpedo tubes of the Navy’s submarines.

As hinted by General Hyten, the Zumwalt-class destroyer (DDG-1000) could also deploy SLCM-Ns. The Navy owns three Zumwalt-class ships, with no plan for further procurement. The mission of the Zumwalt-class has recently expanded to include both surface warfare and land-attack capabilities. It carries the 80-cell Vertical Launch System capable of carrying TLAMs, making it a strong candidate for carrying SLCM-Ns. Surface ships can be seen and tracked, which would increase their vulnerability during conflict, but they can provide a powerful deterrence signal to U.S. adversaries. If deployed to the Indo-Pacific, announced in April 2021 that one of the Zumwalt-class ships would carry the Navy’s Common Hypersonic Glide Body, which would require missile tube alterations to fit the larger hypersonic missiles. Acquiring the hypersonic mission would not rule out the SLCM-N mission—if anything, carrying both systems would fit the Zumwalt’s new mission of blue-water strike. However, limited space on the Zumwalt-class may require trade-offs in the number of hypersonic versus nuclear cruise missiles it can hold. While this trade-off may be offset by future deployment of hypersonic missiles on the VPMs, policymakers will need to consider capacity limits.

Indeed, policymakers have already expressed concern with the SLCM-N detracting from core naval missions, “such as tracking enemy submarines, protecting United States carrier groups, and conducting conventional strikes on priority land targets,” according to introduced legislation . The Navy will also lose missile tubes when the Ohio-class guided-missile submarines (SSGNs) retire in the FY 2026 to FY 2028 timeframe. While the VPMs are intended to make up for lost space provided by the large SSGNs, the Navy’s total missile capacity will still decrease.

Deploying nuclear weapons on conventionally armed platforms brings several issues because DOD manages nuclear weapons differently than conventional weapons. Nuclear and conventional weapons use different fire control systems, requiring the Navy to add fire control stations to conventional ships that would deploy SLCM-Ns. Nuclear weapons management also requires separate personnel training and special security measures. Adding nuclear weapons to conventional ships is not as simple as inserting the missiles into tubes—doing so involves additional, hidden costs.

While these challenges are significant, the Navy can consider potential arrangements to find an amenable concept of operations, as it did during the Cold War. To avoid nuclear certification complications, the Navy could retrofit a block of submarines as dedicated SLCM-N carriers. But that could constrain those submarines from conducting their existing conventional missions. Instead, the Navy might retrofit a portion of its attack submarines to carry SLCM-Ns in addition to conventional weapons, allowing those boats to continue their conventional missions. During the Cold War, the deployment of TLAM-Ns on ships along with conventional missiles did not change the ships’ general mission to implement the Navy’s maritime strategy. One advantage of this option is that U.S. adversaries would not know which boats carried nuclear weapons, increasing uncertainty and deterrence. Indeed, much of the SLCM-N’s contribution to deterrence may be achieved with a relatively modest deployment, creating another opportunity to manage trade-offs.

>>> Traditional Victory Over Russia Is Unlikely. Instead, Expect To Manage Competition for the Long Haul

While delivery platform selection and nuclear certification processes may be complex and create additional costs, development of the missile itself may be simpler. Because the SLCM-N is not a new capability, the Navy can exploit existing technology and know-how to build the SLCM-N. As former secretary of defense James Mattis stated , “[B]y going back to a weapon that we had before, there is a fair amount of already sunk technology costs that we will not have to redo, will not have to come back up and ask for again.” The $9 billion cost estimated by the Congressional Budget Office is based on an assumption that the SLCM-N would be similar to the LRSO. However, the Navy has the option to simplify the SLCM-N development even further by just updating the TLAM-N. Even if the Navy does opt to build a brand-new missile, it could minimize costs by leveraging the technologies used to build the LRSO. In fact, the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2020 required that DOD report on opportunities to do just that.57 The decision to alter the W80-4 Life Extension Program (the warhead being developed for the LRSO) to fit the SLCM-N could also help minimize costs and simplify the effort. While deploying SLCM-Ns on ships may require additional burdens and costs, the Navy does not need to reinvent the wheel to develop the SLCM-N itself.

Ultimately, while issues with nuclear certification, personnel training, and resource allocation present valid challenges, they are not insurmountable and are worth resolving, considering the SLCM-N’s role in deterring the advancing global nuclear threat. Evidence is growing that nuclear war is likeliest to begin at the lower levels of the nuclear escalation ladder in either the European or Indo-Pacific theaters. Regional nuclear forces could also be used to coerce and constrain U.S. response options. This rising threat must serve as the prime driver for U.S. deterrence strategy. Because the SLCM-N can be deployed on a sea-based platform to the theater of conflict and provide a survivable cruise missile option, it can help convince both U.S. adversaries and allies of the United States’ will and capability to respond to a limited, regional nuclear strike. In this sense, it would increase stability among peers by helping to offset an imbalance between U.S. and adversary regional nuclear forces.

Practical considerations such as cost and resource allocation should not preclude the execution of this threat-driven strategy. While indeed challenging, concepts of operations for SLCM-N deployment exist that could lessen the burden on the Navy. The Navy has deployed SLCM-Ns before and can do so again. Even if future budgets remain constrained, the Navy can prioritize SLCM-N development at the lowest cost possible. Because nuclear deterrence is both the Navy and DOD’s number one mission, resourcing the SLCM-N should take priority. Ultimately, the United States must adjust its force posture in some way to respond to the change in nuclear threat, and the modest addition of the SLCM-N could have a significant impact on U.S. national security.

This piece originally appeared in On the Horizon

Our armed forces must be ready to act anywhere in the world where vital national interests are threatened. This can be achieved by ensuring the military has the resources and skilled personnel it needs to keep us safe and maintain freedom.

Index of U.S. Military Strength

To receive periodic updates of defense reports and events, please subscribe here .

FACTSHEET 10 min read

BACKGROUNDER 24 min read

BACKGROUNDER 20 min read

Subscribe to email updates

© 2024, The Heritage Foundation

Mystery as Russia Abruptly Flips Nuclear Drill Scenario

R ussia abruptly changed its nuclear drill scenario on Wednesday, moving it closer to NATO borders, a day after Moscow and its ally Belarus launched joint drills aimed at training their troops in tactical nuclear weapons.

Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered the military drills in May in response to what the Kremlin has described as provocative statements and threats from the West.

The Russian Defense Ministry said on May 21 that the first stage of the drills had started involving the "practical testing of the preparation and use of nonstrategic nuclear weapons" in the country's Southern Military District.

Moscow's second stage of drills began on Tuesday alongside Belarusian troops .

In a statement shared on Telegram on Wednesday, Russia's defense ministry said the country's newly formed Leningrad Military District—stationed close to Finland and the Baltic States—had also joined the nuclear maneuvers. The district was announced in February in response to Finland joining the NATO alliance.

"As part of the second stage of the exercises of nonstrategic nuclear forces, personnel of the missile formation of the Leningrad Military District are practicing combat training tasks of obtaining special training ammunition for the Iskander-M operational-tactical missile system, equipping launch vehicles with them and covertly advancing to the designated position area for training for missile launches," the ministry announced.

It also said the Russian navy would be involved, and that crew members will be equipping "sea-based cruise missiles with training special warheads" and entering designated patrol areas.

Newsweek has approached NATO for comment.

After Putin in February signed new military decrees formally reestablishing the Moscow and Leningrad Military Districts, the Institute for the Study of War ( ISW ), a U.S.-based think tank, assessed that the move indicated he is preparing for a potential large-scale war with NATO in the future.

The ISW assessed at the time that the re-creation of the Moscow Military District and Leningrad Military District "supports the parallel objectives of consolidating control over Russian operations in Ukraine in the short-to-medium term and preparing for a potential future large-scale conventional war against NATO in the long term."

The Leningrad Military District is a key component of the Russian armed forces that oversees parts of the nation's defense strategy in Russia's western region. The district's involvement in Russia's nuclear drills comes amid rising tensions between Russia and the West over Putin's ongoing war in neighboring Ukraine.

Russia has warned that actions by the West could force it to amend its nuclear doctrine, which lays out the conditions under which it can use such weapons.

On June 7, Putin said at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum that his country's nuclear doctrine is "a living instrument" that can be changed.

Russia is "carefully watching what is happening in the world around us and do not exclude making some changes to this doctrine," Putin said.

Do you have a tip on a world news story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about the Russia-Ukraine war? Let us know via [email protected].

Related Articles

- Russia Protest Demands Nuclear Weapons Be Aimed at US Cities

Start your unlimited Newsweek trial

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com.

https://www.barrons.com/news/russian-nuclear-powered-submarine-arrives-in-cuba-3b672983

- FROM AFP NEWS

Russian Nuclear-powered Submarine Arrives In Cuba

- Order Reprints

- Print Article

Russian Marines stand guard on top of the Russian nuclear-powered submarine Kazan, part of the Russian naval detachment visiting Cuba

ADDS Pentagon comments

A Russian nuclear-powered submarine and other naval vessels arrived in Cuba Wednesday for a five-day visit to the communist island off Florida's coast in a show of force amid spiraling US-Russian tensions.

The submarine Kazan, which Cuba says is not carrying nuclear weapons, was accompanied by the frigate Admiral Gorshkov, as well as an oil tanker and a salvage tug.

Russia's defense ministry said in a statement that prior to entering the Havana port, the fleet "completed an exercise on the use of high-precision missile weapons."

The unusual deployment of the Russian military so close to the United States -- particularly the powerful submarine -- comes amid major tensions over the war in Ukraine, where the Western-backed government is fighting a Russian invasion.

"We of course take it seriously, but these exercises don't pose a threat to the United States," Deputy Pentagon Press Secretary Sabrina Singh told journalists.

The port call coincided on Wednesday with a meeting in Moscow between Cuba's Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez and his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov, as the two former Cold War allies further tighten their links.

During the meeting, Rodriguez expressed his government's "rejection of the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) towards the Russian border," which he said "led to the current conflict in Europe, and especially between Moscow and Kyiv," according to a Cuban foreign ministry statement.

People draped in Russian flags look at the Russian nuclear-powered submarine Kazan, part of the Russian naval detachment visiting Cuba

He also called for "a diplomatic, constructive and realistic solution" to the crisis.

The Kazan and Admiral Gorshkov, which is one of Russia's most modern warships, could be seen just off Havana, which is about 90 miles (145 kilometers) from the tip of Florida.

The tanker Pashin and the tug, flying the white, blue and red tricolor of Russia, entered the harbor early Wednesday morning, an AFP reporter said.

"In the coming days, the crews of the ships and support vessels will take part in a number of protocol events," Russia's defense ministry said in a statement published by the Interfax news agency.

Cuba's military said the visit by the naval detachment "strictly complies with international regulations" and is a nod to "the historic relations of friendship" between Havana and Moscow.

Pentagon press secretary Singh said port calls of this nature are "routine naval visits that we've seen under different administrations."

"We're always constantly going to monitor any foreign vessels operating near US territorial waters."

The Russian nuclear-powered submarine Kazan and the frigate Admiral Gorshkov, part of the Russian naval detachment visiting Cuba, arrive at Havana's harbor on June 12, 2024

Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel met with Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin last month for the annual May 9 military parade on Red Square outside the Kremlin.

He wished Russia "success" in its Ukraine offensive and condemned "the geopolitical manipulation" of the United States, in comments reported by Russia's TASS news agency.

During the Cold War, Cuba was an important client state for the Soviet Union. The deployment of Soviet nuclear missile sites on the island triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when Washington and Moscow came close to war.

Relations between Russia and Cuba have become closer since a 2022 meeting between Diaz-Canel and Putin.

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This article has been sent to

- Cryptocurrencies

- Stock Picks

- Barron's Live

- Barron's Stock Screen

- Personal Finance

- Advisor Directory

Memberships

- Subscribe to Barron's

- Saved Articles

- Newsletters

- Video Center

Customer Service

- Customer Center

- The Wall Street Journal

- MarketWatch

- Investor's Business Daily

- Mansion Global

- Financial News London