- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : July 24

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Lance Armstrong wins seventh Tour de France

On July 24, 2005, American cyclist Lance Armstrong wins a record-setting seventh consecutive Tour de France and retires from the sport. After Armstrong survived testicular cancer, his rise to cycling greatness inspired cancer patients and fans around the world and significantly boosted his sport’s popularity in the United States. However, in 2012, in a dramatic fall from grace, the onetime global cycling icon was stripped of his seven Tour titles after being charged with the systematic use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Born on September 18, 1971, in Plano, Texas , Armstrong started his sports career as a triathlete, competing professionally by the time he was 16. Biking proved to be his strongest event, and at age 17 he was invited to train with the U.S. Olympic cycling developmental team in Colorado . He won the U.S. amateur cycling championship two years later, in 1991, then finished 14th in the road race competition at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Spain. He turned pro later that year but finished last in the Classico San Sebastian, his first race as a professional. In 1993 he bounced back to win 10 titles, including his first major race, the World Road Championships. That same year, he also competed in his first Tour de France, the grueling three-week race that attracts the world’s top cyclists, and won the eighth stage. In 1995 he again won a stage of the Tour de France, as well as the Tour DuPont, a major U.S. cycling event.

Armstrong began 1996 as the number-one-ranked cyclist in the world, but he chose not to race the Tour de France and performed poorly at that year’s Olympics. After experiencing intense pain during a training ride, he was diagnosed in October 1996 with Stage 3 testicular cancer, which had spread to his lungs and brain. He underwent surgery and chemotherapy, then began training again in early 1997. Later that year, he signed with the U.S. Postal Service team. After he quit in the middle of one of his first races back, many thought his career was over. However, after taking some time off from competition, Armstrong came back to finish in the top five at both the Tour of Spain and the World Championships in 1998.

In 1999, to the amazement of the cycling community, Armstrong won his first-ever Tour de France and went on to win the race for the next six consecutive years. In addition to his seven overall wins (a record for both total and consecutive wins), he won 22 individual stages and 11 individual time trials, and led his team to victories in three team time trials between 1999 and 2005. After retiring in 2005, Armstrong made a comeback to pro cycling in 2009, finishing third in that year’s Tour and 23rd in the 2010 Tour. He retired for good from the sport in 2011 at age 39.

Over the years, Armstrong’s intense training regimen and his famed dominance in the difficult and treacherous mountain stages of the Tour de France inspired awe among both fans and opponents. His cycling cadence, which averaged 95 to 100 rotations per minute (rpm) but reached as high as 120 rpm, was considered remarkable, particularly during climbs. In addition to being an exceptionally talented climber, Armstrong performed extremely well in time trials.

Throughout his career, Armstrong, like many other top cyclists of his era, was dogged by accusations of performance-boosting drug use, but he repeatedly and vigorously denied all allegations against him and claimed to have passed hundreds of drug tests. In June 2012 the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), following a two-year investigation, charged the cycling superstar with engaging in doping violations from at least August 1998, and with participating in a conspiracy to cover up his misconduct. After losing a federal appeal to have the USADA charges against him dropped, Armstrong, while continuing to maintain he had done nothing wrong, announced on August 23 that he would stop fighting the charges. The next day, USADA banned Armstrong for life from competitive cycling and disqualified all his competitive results from August 1, 1998, through the present.

On October 10, 2012, USADA released hundreds of pages of evidence, including sworn testimony from 11 of Armstrong’s former teammates, that the agency said demonstrated Armstrong and the U.S. Postal Service team had been involved in the most sophisticated and successful doping program in the history of cycling. A week after the USADA report was made public, Armstrong stepped down as chairman of his Livestrong cancer awareness foundation, and also was fired from many of his endorsement deals. On October 22, Union Cycliste Internationale, the cycling’s world governing body, announced that it accepted the findings of the USADA investigation and officially was erasing Armstrong’s name from the Tour de France record books and upholding his lifetime ban from the sport.

After years of denials, Armstrong finally admitted publicly, in a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey that aired on January 17, 2013, he had doped for much of his cycling career, beginning in the mid-1990s through his Tour de France victory in 2005. He admitted to using a performance-enhancing drug regimen that included testosterone, human growth hormone, the blood booster EPO and cortisone.

READ MORE: 9 Doping Scandals That Changed Sports

Also on This Day in History July | 24

This Day in History Video: What Happened on July 24

Religious pioneers settle salt lake valley, “eye of the tiger” from “rocky iii” tops the u.s. pop charts, mary queen of scots deposed, apollo 11 safely returns to earth, american archeologist encounters machu picchu ruins.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Short story writer O. Henry is released from prison

“saving private ryan” opens in theaters, hundreds drown in eastland disaster, a 9-year-old’s murder puts an innocent man in jail, richard nixon and nikita khrushchev have a “kitchen debate”, john hancock scolds major general philip schuyler, operation gomorrah is launched.

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- La Vuelta ciclista a España

- World Championships

- Amstel Gold Race

- Milano-Sanremo

- Tirreno-Adriatico

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège

- Il Lombardia

- La Flèche Wallonne

- Paris - Nice

- Paris-Roubaix

- Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

- Critérium du Dauphiné

- Tour des Flandres

- Gent-Wevelgem in Flanders Fields

- Clásica Ciclista San Sebastián

- INEOS Grenadiers

- Groupama - FDJ

- EF Education-EasyPost

- Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale Team

- BORA - hansgrohe

- Bahrain - Victorious

- Astana Qazaqstan Team

- Intermarché - Wanty

- Lidl - Trek

- Movistar Team

- Soudal - Quick Step

- Team dsm-firmenich PostNL

- Team Jayco AlUla

- Team Visma | Lease a Bike

- UAE Team Emirates

- Arkéa - B&B Hotels

- Alpecin-Deceuninck

- Grand tours

- Countdown to 3 billion pageviews

- Favorite500

- Profile Score

- Top-3 per edition

- Most starts/finishes

- Youngest/oldest winners

- Most top-10s

- Position race ranking

- Most stage wins

- Youngest winners

- Oldest winners

- Fastest stages

- Statistics - Statistics

- Results - Results

- Stages - Stages

- Teams - Teams

- Nations - Nations

- Route - Route

- Points - Points

- »

- Overview 2024

- Total editions: 111

- Country: France

- First edition: 1903

- www.instagram.com/letourdefrance/

- www.letour.fr

- twitter.com/LeTour

- www.facebook.com/letour

Last winners

- 2023 VINGEGAARD Jonas

- 2022 VINGEGAARD Jonas

- 2021 POGAČAR Tadej

- 2020 POGAČAR Tadej

- 2019 BERNAL Egan

- 2018 THOMAS Geraint

- 2017 FROOME Chris

- 2016 FROOME Chris

- 2015 FROOME Chris

- 2014 NIBALI Vincenzo

Name history

- 1903-2024 Tour de France

Position on calendar

- 1 ARMSTRONG Lance 7 0

- 2 INDURAIN Miguel 5

- 3 HINAULT Bernard 5

- 4 MERCKX Eddy 5

- 5 ANQUETIL Jacques 5

- 6 FROOME Chris 4

- 7 LEMOND Greg 3

- 8 BOBET Louison 3

- 9 THYS Philippe 3

- 10 VINGEGAARD Jonas 2

- 1 CAVENDISH Mark 34

- 2 MERCKX Eddy 34

- 3 HINAULT Bernard 28

- 4 LEDUCQ André 25

- 5 ARMSTRONG Lance 22 2

- 6 DARRIGADE André 22

- 7 FRANTZ Nicolas 20

- 8 FABER François 19

- 9 ALAVOINE Jean 17

- 10 ANQUETIL Jacques 16

Grand Tours

- Vuelta a España

Major Tours

- Volta a Catalunya

- Tour de Romandie

- Tour de Suisse

- Itzulia Basque Country

- Milano-SanRemo

- Ronde van Vlaanderen

Championships

- European championships

Top classics

- Omloop Het Nieuwsblad

- Strade Bianche

- Gent-Wevelgem

- Dwars door Vlaanderen

- Eschborn-Frankfurt

- San Sebastian

- Bretagne Classic

- GP Montréal

Popular riders

- Tadej Pogačar

- Wout van Aert

- Remco Evenepoel

- Jonas Vingegaard

- Mathieu van der Poel

- Mads Pedersen

- Primoz Roglic

- Demi Vollering

- Lotte Kopecky

- Katarzyna Niewiadoma

- PCS ranking

- UCI World Ranking

- Points per age

- Latest injuries

- Youngest riders

- Grand tour statistics

- Monument classics

- Latest transfers

- Favorite 500

- Points scales

- Profile scores

- Reset password

- Cookie consent

About ProCyclingStats

- Cookie policy

- Contributions

- Pageload 0.0582s

Major wins of Lance Armstrong - Results and classifications

Major wins on the tour de france.

- 7 times winner of the Tour de France ( 2005 *, 2004 *, 2003 *, 2002 *, 2001 *, 2000 *, 1999 *)

- 22 stages of the Tour de France (1 in 1993 , 1 in 1995 , 4 in 1999 *, 1 in 2000 *, 4 in 2001 *, 4 in 2002 *, 1 in 2003 *, 5 in 2004 *, 1 in 2005 *)

- 8 top 10 of the Tour de France (3rd in 2009 *, 1st in 2005 *, 1st in 2004 *, 1st in 2003 *, 1st in 2002 *, 1st in 2001 *, 1st in 2000 *, 1st in 1999 *)

Other major wins

- Paris-Nice (2nd in 1996)

- Amstel Gold Race (2nd in 1999*, 2nd in 2001*)

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège (2nd in 1994, 2nd in 1996)

- Critérium du Dauphiné (3rd in 2000*, 1st in 2002*, 1st in 2003*)

- Tour de Suisse (1st in 2001*, 2nd in 2010*)

- La Flèche Wallonne (1st in 1996)

- Clásica de San Sebastián (2nd in 1994, 1st in 1995)

- Championship of Zürich (2nd in 1992, 3rd in 2002)

Top 10 in the stages of the Tour de France

61 Top 10 in the stages of the Tour de France.

*Disqualified

- Championship and cup winners

- Club honours

- World Cup: results of all matches

- Winners of the most important cycling races

- Tour de France winners (yellow jersey)

- Best sprinters (green jersey)

- Best climbers (polka dot jersey)

- Best young riders (white jersey)

- Tour de France: Stage winners

- Australian Open: Men's singles

- Australian Open: Women's singles

- Australian Open: Men's doubles

- Australian Open: Women's doubles

- Australian Open: Mixed doubles

- French Open: Men's singles

- French Open: Women's singles

- French Open: Men's doubles

- French Open: Women's doubles

- French Open: Mixed doubles

- US Open: Men's singles

- US Open: Women's singles

- US Open: Men's doubles

- US Open: Women's doubles

- US Open: Mixed doubles

- Wimbledon: Men's singles

- Wimbledon: Women's singles

- Wimbledon: Men's doubles

- Wimbledon: Women's doubles

- Wimbledon: Mixed doubles

No result found

Collections.

YOUR BAG Item added to your cart-->

An in-depth look: how many tour de france wins does lance armstrong have, an in-depth look: how many tour de france wins does lance..., by jocelyn alano june 18, 2024 12:39.

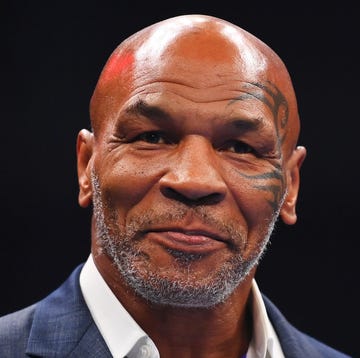

Few names stand out as strongly in cycling - for both positive and negative reasons - as that of Lance Armstrong. The man has had a massive influence on the sport. We explore his legacy alongside his career and achievements and the dark clouds of doping allegations.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Lance Armstrong (@lancearmstrong)

The Triumphs

Lance Armstrong Obvious: Armstrong transitioned from triathlete to pro cyclist, establishing his controversial cycling career. A testicular cancer fight briefly halted his career before his return to the sport in remarkable fashion. He went on to win more consecutive Tours de France than anyone else (seven from 1999 to 2005) in a sign of his dominance as a rider of his generation. It was in 1993, his first big win, World Road Race Championship which confirmed his status as one of the best cyclists. It ended up winning the Tour DuPont not only in 1995 but also in 1996, which further enforced his prowess in the sport of cycling. The Lombard, Illinois, native is the only rider in history to win six straight Tour de France titles - a mark he set overall with his win in 2004 - using a defining performance to claim his seventh and final victory with nearly two minutes of a margin in 2005, his last Tour de France.

The Controversy

Armstrong's feats on the road were legendary, but his rise to glory was overshadowed by the revelation that he used performance-enhancing drugs. In 2012, all seven of his Tour de France titles were stripped after irrefutable evidence emerged that he had doped for the majority of his life as a cyclist. Armstrong, who for years defiantly denied doping, retired in 2013 as one of the sport's most controversial and tarnished figures.

Lance Armstrong is a virtually undeniably polarizing figure at this point in his career, but no one is going to argue with the impact he had on a sport like cycling. But it is his generosity, zeal, and tenacious fight back from cancer, having claimed a record seven Tour de France events which have now faded into time! Moreover, his creation of the Lance Armstrong Foundation, since known as the Livestrong Foundation, to aid cancer patients also marks a societal shift from cycling.

The story of Lance Armstrong is one of victory, redemption, and scandal. His seven wins in the Tour de France have sent his name into the annals of cycling history, as has his fight with cancer. The shadow of doping allegations may never be cast off, but Armstrong's impact on the sport and his dedication to his charity work in support of cancer survivors will always be part of his lasting legacy. There is a poignancy even in that Armstrong is a name that in the world of cycling will now always be associated with both great days and dark days.

Cricket's Incredible Rise in Popularity in the ...

By Jocelyn Alano

Tue, Jun 18, 2024

Is Simone Biles the Greatest Female Olympian of...

Mon, Jun 17, 2024

Bob Beamon: The Journey of an Olympic Legend

By Edcel Panganiban

Who is the Greatest Olympian Track and Field Ru...

What is michael phelps doing now, how did steroids tarnish the legacy of michael ..., one of the greatest olympians of all time: who ....

By Arslan Saleem

The Rise and Fall: What Happened to Olympian La...

The top 10 greatest male gymnasts of all-time.

By Oliver Wiener

Sun, Jun 16, 2024

The Top 10 Greatest Alpine Skiers of All-Time

The top 10 greatest table tennis players of all..., the fastest man of all time: unraveling the leg....

Fri, Jun 14, 2024

Which World Record Is Sydney McLaughlin Most Kn...

The swedish olympian shattering records: who is..., caitlin clark left off the team usa olympic tea....

Thu, Jun 13, 2024

Jerome Avery: The Inspiring Journey of a 4-Time...

Tue, Jun 11, 2024

Gail Devers: The Inspiring Journey of an Americ...

Dwight phillips: the legendary story of an olym..., kellie wells brinkley: a journey of triumph fro..., lolo jones: a remarkable journey in track and f....

Sun, Jun 09, 2024

Noah Lyles's Net Worth in 2024

By Jason Bolton

Tue, Jun 04, 2024

Paralympic Games 2024: Key Athletes and Inspira...

Mon, Jun 03, 2024

The 2024 Paris Olympics: Athletes and Nations G...

Usain bolt's return to the track: a fun what-if....

Tue, May 28, 2024

Sha'Carri Richardson wins 100m at Prefontaine C...

Sat, May 25, 2024

Sebastian Steudtner: Big Wave Surfer Finds Peac...

Thu, May 23, 2024

Chris Birch: From Track Cyclist to NASA Astronaut

The ultimate guide to 2024 paris olympics: venu....

Tue, May 21, 2024

The Impact of the 2024 Paris Olympics on Local ...

By Fan Arch

The Architectural Marvels of the 2024 Paris Oly...

Diversity and inclusion efforts at the 2024 par..., 2024 paris olympics: the significance of the ga..., environmental impact assessment of the 2024 par..., who is faster elaine thompson or sha carri rich....

Fri, May 17, 2024

What was Florence Griffith Joyner's Cause of De...

Why did florence griffith joyner stop running, how did florence griffith joyner change the world, sprinting to success: the legendary career of o..., perfect 10: the unforgettable journey of olympi..., endurance extraordinaire: inside the phenomenal..., flying high: unraveling the remarkable legacy o..., paddling to glory: a deep dive into the olympic..., golden strides: decoding the unmatched success ..., fencing through history: the illustrious journe..., soaring to greatness: the inspiring story of ol..., grace and grit: the inspiring path of olympic c..., rising to new heights: the pole vaulting legacy..., against all odds: the timeless triumph of olymp..., trailblazing victory: the unforgettable legacy ..., fan arch podcast network.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Two-Way

Lance armstrong's seven tour de france titles are effectively gone.

Mark Memmott

Mike Pesca, reporting for the NPR Newcast

Lance Armstrong, wearing the yellow jersey that identifies the leader in the Tour de France, during the race in 2003. He won that year and six other times. Joel Saget/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

Lance Armstrong, wearing the yellow jersey that identifies the leader in the Tour de France, during the race in 2003. He won that year and six other times.

Cycling superstar and cancer survivor Lance Armstrong's seven Tour de France titles are about to be wiped from the record books.

As NPR's Mike Pesca said early Friday on Morning Edition , while it is the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency that announced Thursday it would strip Armstrong of his titles — including the French records — because of the evidence it says it has collected that he was doping throughout his career, "the USADA is associated with the World Anti-Doping Agency." So the American decision will be honored in France, Mike says.

"Greg LeMond is [now] the only American" to have officially won the world's most prestigious bicycle race, he told Morning Edition host Steve Inskeep. LeMond finished first in three Tours ( 1986, 1989 and 1990 ).

Lance Armstrong's Tour de France wins came in:

The USADA's decision also means Armstrong will likely lose his bronze medal from the 2000 Olympics. And he may be banned for life from competitions. Retired from cycling, the 40-year-old Armstrong has recently been competing professionally in triathlons.

It's important to note that Armstrong, in a statement issued Thursday in which he said he would no longer contest the charges being leveled against him, called the USADA's case a "charade" and a "witch hunt." He also asserted that:

"USADA cannot assert control of a professional international sport and attempt to strip my seven Tour de France titles. I know who won those seven Tours, my teammates know who won those seven Tours, and everyone I competed against knows who won those seven Tours."

But John Fahey, head of the World Anti-Doping Agency, said today that Armstrong's Tour de France titles now need to be "obliterated" from the record books, the BBC reports .

Armstrong "had the right to rip up those charges but elected not to," said Fahey, according to the BBC. "Therefore the only interpretation in these circumstances is that there was substance in those charges."

Another way to look at Armstrong's statement, Mike said on Morning Edition , is as something of a "no contest" plea.

Update at 12:10 p.m. ET. U.S. Anti-Doping Agency Takes Official Action.

In a statement on its website , the agency says:

"USADA announced today that Lance Armstrong has chosen not to move forward with the independent arbitration process and as a result has received a lifetime period of ineligibility and disqualification of all competitive results from August 1, 1998 through the present, as the result of his anti-doping rule violations stemming from his involvement in the United States Postal Service (USPS) Cycling Team Doping Conspiracy (USPS Conspiracy)."

And it adds that:

"The anti-doping rule violations for which Mr. Armstrong is being sanctioned are: "(1) Use and/or attempted use of prohibited substances and/or methods including EPO, blood transfusions, testosterone, corticosteroids and masking agents. "(2) Possession of prohibited substances and/or methods including EPO, blood transfusions and related equipment (such as needles, blood bags, storage containers and other transfusion equipment and blood parameters measuring devices), testosterone, corticosteroids and masking agents. "(3) Trafficking of EPO, testosterone, and corticosteroids. "(4) Administration and/or attempted administration to others of EPO, testosterone, and cortisone. "(5) Assisting, encouraging, aiding, abetting, covering up and other complicity involving one or more anti-doping rule violations and/or attempted anti-doping rule violations."

- Lance Armstrong

Lance Armstrong wins seventh consecutive and last Tour de France

Lance Armstrong closed out his amazing career with a seventh consecutive Tour de France victory today — and did it a little earlier than expected.

Share story

PARIS — Lance Armstrong closed out his amazing career with a seventh consecutive Tour de France victory today — and did it a little earlier than expected. Because of wet conditions, race organizers stopped the clock as Armstrong and the main pack entered Paris. Although riders were still racing, with eight laps of the Champs-Elysees to complete, organizers said that Armstrong had officially won. The stage started as it has done for the past six years — with Armstrong celebrating and wearing the race leader’s yellow jersey. One hand on his handlebars, the other holding a flute of champagne, Armstrong toasted his teammates as he pedaled into Paris to collect his crown. He held up seven fingers — one for each win — and a piece of paper with the number 7 on it. When it was over, Armstrong saluted the race he’s made his own. “Vive le Tour, forever,” he said. Armstrong choked up on the victory podium as he stood next to his twin 3-year-old daughters — dressed in bright yellow dresses, appropriately — and his son. His rock star girlfriend Sheryl Crow, wearing a yellow halter top, cried during the ceremony. “This is the way he wanted to finish his career, so it’s very emotional,” she said. Looking gaunt, his cheeks hollow after riding 2,232.7 miles across France and its mountains for three weeks, Armstrong still could smile at the end. He said President Bush called to congratulate him. Armstrong’s new record of seven wins confirmed him as one of the greatest cyclists ever, and capped a career where he came back from cancer to dominate cycling’s most prestigious and taxing race. Standing on the podium, against the backdrop of the Arc de Triomphe, Armstrong managed a rare feat in sports — going out on the top of his game. He previously said that his decision was final and that he was walking away with “absolutely no regrets.” Armstrong mentioned Tiger Woods, Wayne Gretzky, Michael Jordan and Andre Agassi as personal inspirations. “Those are guys that you look up to you, guys that have been at the top of their game for a long time,” he said. As for his accomplishments, he said, “I can’t be in charge of dictating what it says or how you remember it.” “In five, 10, 15, 20 years, we’ll see what the legacy is. But I think we did come along and revolutionize the cycling part, the training part, the equipment part. We’re fanatics.” Alexandre Vinokourov of Kazakhstan eventually won the final stage, with Armstrong finishing safely in the pack to win the Tour by more than 4 minutes, 40 seconds over Ivan Basso of Italy. The 1997 Tour winner, Jan Ullrich, was third, 6:21 back. “It’s up to you guys,” Armstrong said, forecasting the Tour future. Armstrong’s sixth win last year already set a record, putting Armstrong ahead of four other riders — Frenchmen Jacques Anquetil and Bernard Hinault, Belgian Eddy Merckx and Spaniard Miguel Indurain — who all won five Tours. Along the way, he brought unprecedented attention to the sport, and won over many who had dismissed it. “Finally, the last thing I’ll say for the people who don’t believe in cycling — the cynics, the skeptics — I’m sorry for you,” Armstrong said. “I’m sorry you can’t dream big and I’m sorry you don’t believe in miracles. But this is one hell of a race, this is a great sporting event and you should stand around and believe.” Armstrong’s last ride as a professional — the closing 89.8-mile 21st stage into Paris from Corbeil-Essonnes south of the capital — was not without incident. Three of his teammates slipped and crashed on the rain-slicked pavement coming around a bend just before they crossed the River Seine. Armstrong, right behind them, braked and skidded into the fallen riders. Armstrong used his right foot to steady himself, and was able to stay on the bike. His teammates, wearing special shirts with a band of yellow on right shoulder, recovered and led him up the Champs-Elysees at the front of the pack. Organizers then announced that they had stopped the clock because of the slippery conditions with more than 10 miles to go. Vinokourov surged ahead of the main pack to win the last stage. He had been touted as one of Armstrong’s main rivals at the start of the Tour on July 2, but like others was overwhelmed by the 33-year-old Texan. Armstrong’s departure begins a new era for the 102-year-old Tour, with no clear successor. His riding and his inspiring defeat of cancer attracted new fans — especially in the United States — to the race, as much a part of French summers as sun cream, forest fires and traffic jams down to the Cote d’Azur. Millions turned out each year, cheering, picnicking and sipping wine by the side of the road, to watch him flash past in the race leader’s yellow jersey, the famed “maillot jaune.” Cancer survivors, autograph hunters and enamored admirers pushed, shove, and yelled “Lance! Lance!” outside his bus in the mornings for a smile, a signature, or a word from the champion. He had bodyguards to keep the crowds at bay — ruffling feathers of cycling purists who sniffed at his “American” ways. Some spectators would shout obscenities or “dope!” — doper. To some, his comeback from cancer and his uphill bursts of speed that left rivals gasping in the Alps and Pyrenees were too good to be true. Armstrong insisted that he simply trained, worked and prepared harder than anyone. He was drug-tested hundreds of times, in and out of competition, but never found to have committed any infractions. Armstrong came into this Tour saying he had a dual objective — winning the race and the hearts of French fans. He was more relaxed, forthcoming and talkative than last year, when the pressure to be the first six-time winner was on. Some fans hung the Stars and Stripes on barriers that lined the Champs-Elysees on Sunday. Around France, some also urged Armstrong to go for an eighth win next year— holding up placards and daubing their appeals in paint on the road. Armstrong, however, wanted to go out on top — and not let advancing age get the better of him. “At some point you turn 34, or you turn 35, the others make a big step up, and when your age catches up, you take a big step down,” he said Saturday after he won the final time trial. “So next could be the year if I continued that I lose that five minutes. We are never going to know.”

Watch CBS News

Lance Armstrong On Tour De France: I'm Still The Record-Holder For Victories

June 28, 2013 / 12:31 PM EDT / CBS New York

PORTO VECCHIO, Corsica (CBSNewYork/AP) — The dirty past of the Tour de France came back on Friday to haunt the 100th edition of cycling's showcase race, with Lance Armstrong telling a newspaper he couldn't have won without doping.

Armstrong's comments to Le Monde were surprising on many levels, not least because of his long-antagonistic relationship with the respected French daily that first reported in 1999 that corticosteroids were found in the American's urine as he was riding to the first of his seven Tour wins. In response, Armstrong complained he was being persecuted by "vulture journalism, desperate journalism."

Now seemingly prepared to let bygones be bygones, Armstrong told Le Monde he still considers himself the record-holder for Tour victories, even though all seven of his titles were stripped from him last year for doping . He also said his life has been ruined by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency investigation that exposed as lies his years of denials that he and his teammates doped. And Armstrong took another swipe at cycling's top administrators, darkly suggesting they could be brought down by other skeletons in the sport's closet.

The interview was the latest blast from cycling's doping-tainted recent history to rain on the 100th Tour.

Recently, Armstrong's former rival on French roads, 1997 Tour winner Jan Ullrich, confessed to blood-doping for the first time with a Spanish doctor. French media also reported that a Senate investigation into the effectiveness of anti-doping controls pieced together evidence of drug use at the 1998 Tour by Laurent Jalabert, a former star of the race now turned broadcaster.

Not surprising in Armstrong's interview was his claim that it was "impossible" to win the Tour without doping when he was racing. Armstrong already told U.S. television talk show host Oprah Winfrey when he finally confessed in January that doping was just "part of the job" of being a pro cyclist.

"I kept hearing I'm a drug cheat, I'm a cheat, I'm a cheater," Armstrong said in the Winfrey interview. "I went in and just looked up the definition of cheat and the definition of cheat is to gain an advantage on a rival or foe that they don't have. I didn't view it that way. I viewed it as a level playing field."

The banned hormone erythropoietin, or EPO, wasn't detectable by cycling's doping controls until 2001 and so was widely abused because it prompts the body to produce oxygen-carrying red blood cells, giving a big performance boost to endurance athletes.

Armstrong was clearly talking about his own era, rather than the Tour today. Le Monde reported that he was responding to the question: "When you raced, was it possible to perform without doping?"

"That depends on which races you wanted to win. The Tour de France? No. Impossible to win without doping. Because the Tour is a test of endurance where oxygen is decisive," Le Monde quoted Armstrong as saying. It published the interview in French.

Some subsequent media reports about Le Monde's interview concluded that Armstrong was saying doping is still necessary now, rather than when he was winning the Tour from 1999-2005. That suggestion provoked dismay from current riders, race organizers and the sport's governing body, the International Cycling Union or UCI. Five-time champion Bernard Hinault, who works for Tour organizer ASO, said: "We have to stop thinking that all riders are thugs and druggies and all that."

Asked later by The Associated Press to clarify his comments, Armstrong said on Twitter he was talking about the period from 1999-2005. He indicated that doping might not be necessary now.

"Today? I have no idea. I'm hopeful it's possible," Armstrong tweeted.

In a statement issued before that clarification, UCI President Pat McQuaid called the timing of Armstrong's comments "very sad."

"I can tell him categorically that he is wrong. His comments do absolutely nothing to help cycling," McQuaid said in a statement. "The culture within cycling has changed since the Armstrong era and it is now possible to race and win clean.

"Riders and teams owners have been forthright in saying that it is possible to win clean — and I agree with them."

After Armstrong retired for the first time in 2005, cycling pioneered a so-called "biological passport" program, introduced in 2008, that monitors riders' blood readings for tell-tale signs of doping. Riders in the top tier of teams were tested an average of nearly 12 times in 2012. Yet the pre-Tour drip-drip-drip of doping confessions and revelations about the Armstrong era have overshadowed cycling's work to break its culture of drug use.

That, in turn, has led to renewed appeals from some involved in the sport for cycling to have a "truth and reconciliation" process — where all those involved in doping past and present could air what they know and did once and for all, so cycling can then move forward.

"Having it come out in dribs and drabs: You know, Laurent Jalabert this week, this guy (another week) — is ridiculous and painful and unnecessary," Jonathan Vaughters, a former Armstrong teammate and manager of the Garmin-Sharp team, said this week before Le Monde's interview. "I really wish that we could get on with the truth and reconciliation committee. ... Let's just move the sport forward, let's get it out, let's deal with it, let's recognize it, let's own it, let's learn from it."

Armstrong told Le Monde he would be prepared to appear before such a committee.

"The whole story has still not been told," he was quoted as saying. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency investigation that unmasked him as a serial doper "did not paint a faithful picture of cycling from the end of the 1980s to today. It succeeded perfectly in destroying one man's life but did not benefit cycling at all."

He argued that doping would never be eradicated.

"I did not invent doping," Le Monde quoted Armstrong as saying. "And nor did it end with me."

You May Also Be Interested In These Stories

(TM and © Copyright 2013 CBS Radio Inc. and its relevant subsidiaries. CBS RADIO and EYE Logo TM and Copyright 2013 CBS Broadcasting Inc. Used under license. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. The Associated Press contributed to this report.)

- Lance Armstrong

Featured Local Savings

More from cbs news.

Aaron Judge hit by pitch, leaves Yankees' win over Orioles

Mets rally to defeat Rangers for season-high 7th straight win

3 Asian-American candidates battling in District 40 primary in Queens

Mets pound out 22 hits, run winning streak to 6 with rout of Rangers

Lance Armstrong

Who Is Lance Armstrong?

Lance Armstrong became a triathlete before turning to professional cycling. His career was halted by testicular cancer, but Armstrong returned to win a record seven consecutive Tour de France races beginning in 1999. Stripped of those titles in 2012 due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use, Armstrong in 2013 admitted to doping throughout his cycling career, following years of denials.

Early Career

Born on September 18, 1971, in Plano, Texas, Armstrong was raised by his mother, Linda, in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas. Armstrong was athletic from an early age. He began running and swimming at 10 years old, and took up competitive cycling and triathlons at 13. At 16, Armstrong became a professional triathlete—he was the national sprint-course triathlon champion in 1989 and 1990.

Soon after, Armstrong chose to focus on cycling, his strongest event as well as his favorite. During his senior year of high school, the U.S. Olympic development team invited him to train in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Armstrong left high school temporarily to do so, but later took private classes and received his high school diploma in 1989.

The following summer, he qualified for the 1990 junior world team and placed 11th in the World Championship Road Race, with the best time of any American since 1976. That same year, he became the U.S. national amateur champion and beat out many professional cyclists to win two major races, the First Union Grand Prix and the Thrift Drug Classic.

International Cycling Star

In 1991, Armstrong competed in his first Tour DuPont, a long and difficult 12-stage race, covering 1,085 miles over 11 days. Though he finished in the middle of the pack, his performance announced a promising newcomer to the world of international cycling. He went on to win a stage at Italy's Settimana Bergamasca race later that summer.

After finishing second in the U.S. Olympic time trials in 1992, Armstrong was favored to win the road race in Barcelona, Spain. With a surprisingly sluggish performance, however, he came in only 14th. Undeterred, Armstrong turned professional immediately after the Olympics, joining the Motorola cycling team for a respectable yearly salary. Though he came in dead last in his first professional event, the day-long San Sebastian Classic in Spain, he rebounded in two weeks and finished second in a World Cup race in Zurich, Switzerland.

Armstrong had a strong year in 1993, winning cycling's "Triple Crown"—the Thrift Drug Classic, the Kmart West Virginia Classic and the CoreStates Race (the U.S. Professional Championship). That same year, he came in second at the Tour DuPont. He started off well in his first-ever Tour de France, a 21-stage race that is widely considered cycling's most prestigious event. Though he won the eighth stage of the race, he later fell to 62nd place and eventually pulled out.

In August 1993, the 21-year-old Armstrong won his most important race yet: the World Road Race Championship in Oslo, Norway, a one-day event covering 161 miles. As the leader of the Motorola team, he overcame difficult conditions—pouring rain made the roads slick and caused him to crash twice during the race—to become the youngest person and only the second American ever to win that contest.

The following year, he was again the runner-up at the Tour DuPont. Frustrated by his near miss, he trained with a vengeance for the next year's event and went on to finish two minutes ahead of rival Viatcheslav Ekimov of Russia for the win. At the Tour DuPont in 1996, he set several event records, including the largest margin of victory (three minutes, 15 seconds) and the fastest average speed in a time trial (32.9 miles per hour).

Also in 1996, Armstrong rode again for the Olympic team in Atlanta, Georgia. Looking uncharacteristically fatigued, he finished sixth in the time trials and 12th in the road race. Earlier that summer, he had been unable to finish the Tour de France, as he was sick with bronchitis. Despite such setbacks, Armstrong was still riding high by the fall of 1996. Then the seventh-ranked cyclist in the world, he signed a lucrative contract with a new team, France's Team Cofidis.

Battling Testicular Cancer

In October 1996, however, came the shocking announcement that Armstrong had been diagnosed with testicular cancer. Well advanced, the tumors had spread to his abdomen, lungs and lymph nodes. After having a testicle removed, drastically modifying his eating habits and beginning aggressive chemotherapy, Armstrong was given a 65 to 85 percent chance of survival. When doctors found tumors on his brain, however, his odds of survival dropped to 50-50, and then to 40 percent. Fortunately, a subsequent surgery to remove his brain tumors was declared successful, and after more rounds of chemotherapy, Armstrong was declared cancer-free in February 1997.

Throughout his terrifying struggle with the disease, Armstrong continued to maintain that he was going to race competitively again. No one else seemed to believe in him, however, and Cofidis pulled the plug on his contract and $600,000 annual salary. As a free agent, he had a good deal of trouble finding a sponsor, finally signing on to a $200,000-per-year position with the United States Postal Service team.

Tour de France Dominance

At the 1998 Tour of Luxembourg, his first international race since returning from cancer, Armstrong showed he was up for the challenge by winning the opening stage. A little over a year later, he capped his comeback in grand style by becoming the second American, after Greg LeMond, to win the Tour de France. He repeated that feat in July 2000 and followed with a bronze medal at the Summer Olympic Games.

Armstrong bolstered his legacy as his generation's dominant rider by handily winning the Tour in 2001 and 2002. However, notching a fifth victory, tying the record held by Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain, proved his most difficult accomplishment. Stricken by illness before the start of the race, Armstrong fell at one point after snagging a spectator's bag, and barely avoided another crash by swerving across a field. He finished one minute and one second ahead of Germany's Jan Ullrich, the closest of his Tour triumphs.

Armstrong was back in top form to claim his record-breaking sixth Tour win in 2004. He won five individual stages, finishing a comfortable six minutes and 19 seconds ahead of Germany's Andreas Kloden. After capping his astounding run with a seventh consecutive Tour victory in 2005, he retired from racing.

Return to Competition

On September 9, 2008, Armstrong announced that he planned to return to competition and the Tour de France in 2009. A member of Team Astana, he placed third in the race, behind teammate Alberto Contador and Saxo Bank team member Andy Schleck.

After the race, Armstrong told reporters that he intended to compete again in 2010, with a new team endorsed by RadioShack. Slowed by multiple crashes, Armstrong finished 23rd overall in what would be his final Tour de France, and he announced he was retiring for good in February 2011.

Drug Controversy

Despite the inspiring narrative of Armstrong's triumph over cancer, not everyone was convinced it was valid. Irish sportswriter David Walsh, for one, became suspicious of Armstrong's behavior and sought to shed light on the rumors of drug use in the sport. In 2001, he wrote a story linking Armstrong to Italian doctor Michele Ferrari, who was being investigated for supplying performance enhancers to cyclists. Walsh later secured a confession from Armstrong's masseuse, Emma O'Reilly, and laid out his case against the American champion as co-writer of the 2004 book L.A. Confidential.

The plot thickened in 2010, when former U.S. Postal rider Floyd Landis, who had been stripped of his 2006 Tour de France win for drug use, admitted to doping and accused his celebrated teammate of doing the same. That prompted a federal investigation, and in June 2012 the U.S Anti-Doping Agency brought formal charges against Armstrong. The case heated up in July 2012, when some media outlets reported that five of Armstrong's former teammates, George Hincapie, Levi Leipheimer, David Zabriskie and Christian Vande Velde—all of whom participated in the 2012 Tour de France—were planning to testify against Armstrong.

The cycling champion vehemently denied using illegal drugs to boost his performance, and the 2012 USADA charges were no exception: He disparaged the new allegations, calling them "baseless." On August 23, 2012, Armstrong publicly announced that he was giving up his fight with the USADA's recent charges and that he had declined to enter arbitration with the agency because he was tired of dealing with the case, along with the stress the case created for his family.

"There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now," Armstrong said in an online statement around that time. "I have been dealing with claims that I cheated and had an unfair advantage in winning my seven Tours since 1999. The toll this has taken on my family and my work for our foundation and on me leads me to where I am today—finished with this nonsense."

Banned From Cycling

The following day, on August 24, 2012, the USADA announced that Armstrong would be stripped of his seven Tour titles—as well as other honors he received from 1999 to 2005—and banned from cycling for life. The agency concluded in its report that Armstrong had used banned performance-enhancing substances. On October 10, 2012, the USADA released its evidence against Armstrong, which included documents such as laboratory tests, emails and monetary payments. "The evidence shows beyond any doubt that the U.S. Postal Service Pro Cycling Team ran the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that the sport had ever seen," Travis Tygart, chief executive of the USADA, said in a statement.

The USADA evidence against Armstrong also contained testimony from 26 people. Several former members of Armstrong's cycling team were among those who claimed that Armstrong used performance-enhancing drugs and served as a type of a ringleader for the team's doping efforts. According to The New York Times , one teammate told the agency that "Lance called the shots on the team" and "what Lance said went."

Armstrong disputed the USADA's findings. His attorney, Tim Herman, called the USADA's case "a one-sided hatchet job" featuring "old, disproved, unreliable allegations based largely on axe-grinders, serial perjurers, coerced testimony, sweetheart deals and threat-induced stories," according to USA Today .

Shortly after the release of the USADA findings, the International Cycling Union (cycling's governing body) supported the USADA's decision and officially stripped Armstrong of his seven Tour de France victories. The union also banned Armstrong from the sport for life. ICU president Pat McQuaid said in a statement that "Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling."

Admission and Later Events

Of the interview, Winfrey said in a statement, "He did not come clean in the manner I expected. It was surprising to me. I would say that, for myself, my team, all of us in the room, we were mesmerized by some of his answers. I felt he was thorough. He was serious. He certainly prepared himself for this moment. I would say he met the moment. At the end of it, we both were pretty exhausted."

Around the same time that the interview was conducted, it was reported that the U.S. Department of Justice would join a lawsuit already in place against the cyclist, over his alleged fraud against the government. Armstrong's attempts to have the lawsuit dismissed were rejected, and in early 2017 the case was allowed to proceed to trial.

Fraud Settlement

In spring 2018, two weeks before his trial was scheduled to begin, Armstrong agreed to pay the U.S. Postal Service $5 million to settle their claims of being defrauded. According to his legal team, the settlement ended "all litigation against Armstrong related to his 2013 admission" of using performance-enhancing drugs.

"I am particularly glad to have made peace with the Postal Service," said Armstrong said in a statement. "While I believe that their lawsuit against me was without merit and unfair, I have since 2013 tried to take full responsibility for my mistakes, and make amends wherever possible. I rode my heart out for the Postal cycling team, and was always especially proud to wear the red, white and blue eagle on my chest when competing in the Tour de France."

Landis, the whistle-blower in the case, stood to receive $1.1 million of the amount paid to the government. Additionally, Armstrong agreed to shell out $1.65 million to cover his old teammate's legal expenses.

Movie and Documentaries

In 2015, the Armstrong biopic The Program , with Ben Foster portraying the fallen cyclist, premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. Armstrong had little to say about the film, other than criticizing its star for taking performance-enhancing drugs to prepare for the role.

Armstrong was far more receptive to the release of Icarus , a Netflix documentary in which amateur cyclist Bryan Fogel also pumps up on PEDs before uncovering a Russian state-sponsored system created to mask its athletes' use of such drugs. In late 2017, Armstrong tweeted: "After being asked roughly a 1000 times if I’ve seen @IcarusNetflix yet, I finally sat down to check it out. Holy hell. It’s hard to imagine that I could be blown away by much in that realm but I was. Incredible work @bryanfogel!"

It was subsequently announced that on January 6, 2018, the day after Academy Award voters could begin submitting their ballots, Armstrong would co-host a screening and reception for Icarus in New York.

The cyclist returned to the spotlight with the Marina Zenovich-directed documentary Lance , which premiered at the January 2020 Sundance Film Festival before airing on ESPN that May. Along with examining the formative influences that drove him to become such a ruthless competitor, the doc showcased Armstrong's attempts to adapt to public life in the years after he had fallen from his pedestal as one of the world's most admired athletes.

Charity, Personal Life and Children

Armstrong has lived in Austin, Texas, since 1990. In 1996, he founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer, now called LiveStrong, and the Lance Armstrong Junior Race Series to help promote cycling and racing among America's youth. He is the author of two best-selling autobiographies, It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life (2000) and Every Second Counts (2003).

In 2006, Armstrong ran the New York City Marathon, raising $600,000 for his LiveStrong campaign. He stepped down from LiveStrong in October 2012 following the USADA report about his use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Armstrong married Kristin Richard, a public relations executive he met through his cancer foundation, in 1998. The couple had a son, Luke, in October 1999, using sperm frozen before Armstrong began chemotherapy. Twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace, were born in 2001. The couple filed for divorce in 2003. Afterward, he dated rocker Sheryl Crow , fashion designer Tory Burch and actresses Kate Hudson and Ashley Olsen .

In December 2008, Armstrong announced that his girlfriend, Anna Hansen, was pregnant with his child. The couple had been dating since July after meeting through Armstrong's charity work. The baby boy, Maxwell Edward, was born on June 4, 2009. A daughter, Olivia Marie, followed on October 18, 2010.

In July 2013, Armstrong made headlines again when it was reported that he would be competing in The Des Moines Register 's Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, a statewide cycling race sponsored by the newspaper.

"I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great," Armstrong stated shortly after the news broke, according to the Daily Mail . "If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it."

In 2015, Armstrong returned to the Tour de France course to ride in a leukemia charity event one day before the start of the race.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Lance Armstrong

- Birth Year: 1971

- Birth date: September 18, 1971

- Birth State: Texas

- Birth City: Plano

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Lance Armstrong is a cancer survivor and former professional cyclist who was stripped of his seven Tour de France wins due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use.

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Lance Armstrong Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/athletes/lance-armstrong

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 23, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now.

- My ruthless desire to win at all costs served me well on the bike but the level it went to, for whatever reason, is a flaw. That desire, that attitude, that arrogance.

- The biggest challenge of the rest of my life is to not slip up again and not lose sight of what I have to do. I had it but things got too big and too crazy.

- If you're trying to hide something, you wouldn't keep getting away with it for 10 years. Nobody is that clever.

- I know the truth. The truth isn't what was out there. The truth isn't what I said, and now it's gone—this story was so perfect for so long.

- There was more happiness in the process, in the build, in the preparation. The winning was almost phoned in.

- If you're asking me if I want to compete again, the answer is hell yes, I'm a competitor.

- I learned a lesson that day. No more gifts."[On giving Marco Pantani a stage win in the 2000 Tour de France]

- The Look was just one part of a great battle with the Telekom team all day.

- Nobody believed I was able to do that after the crash. But I was a desperate man, and I knew that was my last chance to win the Tour de France.

- I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great. If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it.

- I am deeply flawed ... and I'm paying the price for it, and I think that's okay. I deserve this."[On being stripped of his seven Tour de France titles for doping as a pro cyclist.]

- Two things scare me: The first is getting hurt. But that's not nearly as scary as the second, which is losing.

- Pain is temporary. It may last a minute, or an hour, or a day, or a year, but eventually it will subside and something else will take its place. If I quit, however, it lasts forever.

Famous Athletes

Jerry West Hated the Iconic NBA Logo He Inspired

30 Olympic Athletes On The Red Carpet

Novak Djokovic

Jesse Owens

Naomi Osaka

Brittney Griner Advocates for Other Detainees

Simone Biles

Trinity Rodman

Dorothy Hamill

Lance Armstrong: I'd have won the Tour de France if everyone was clean

'We did what we had to do to win'

Lance Armstrong says he and his teams would have won the Tour de France multiple times if the entire peloton was riding clean during his now-stripped reign of seven victories from 1999 through 2005.

Lance Armstrong: Uber investment 'saved' my family

Lance Armstrong to feature in ESPN film series

Lance Armstrong's $1 million Tour Down Under start money confirmed

Lance Armstrong: I wouldn't change a thing

In a wide-ranging interview with NBC Sports as part of the network’s 2019 Tour de France coverage, journalist Mike Tirico interviewed the 47-year-old whose seven Tour de France victories were taken away after the US Anti-Doping Agency's investigation and 2012 "Reasoned Decision" detailing Armstrong’s guilt.

Although Armstrong told Tirico his decision to dope was a mistake, he also said he wouldn't change a thing in his career, and he was proud of the efforts he and his teams put into the Tour preparation outside of their use of performance enhancing drugs.

"What I wish would have happened, I wish kids from Plano and Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and Brooklyn and Montana, as young Americans, if we'd have gone to Europe and everybody was fighting with their fists, we still win," he said. "I promise you that.

"What did we say? We said we worked the hardest, had the best tactics, best team composition, best director, best equipment, best technology, recon the courses. All the things we said, we did. We left out a part, but we did all that stuff. Because now this one thing is part of the story doesn't erase all that. All that happened," Armstrong said. "If you just had this one thing and did none of that, you get last."

When Tirico asked Armstrong to recall why he and many of his US cohorts decided to use performance enhancing drugs, the Texan said it was their belief that they needed to dope to compete in Europe.

"That wasn't just a feeling, that was a fact," he said. "I don't want to make excuses for myself that everybody did it or we never could have won without it. Those are all true, but the buck stops with me. I'm the one who made the decision to do what I did, and it was ... I didn't want to go home, man. I was gonna stay.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"I told you earlier, I don't lay down. And it was the wrong decision, but laying down would have been giving up, going home.

"I knew there were going to be knives at this fight, not just fists. I knew there would be knives. I had knives, and then one day, people start showing up with guns. That's when you say, 'Do I either fly back to Plano, Texas, and not know what you're going to do? Or do you walk over to the gun store?' I walked to the gun store. I didn't want to go home.

Armstrong pushed back against claims that he was the ring leader who cajoled others into doping.

"There are a few things that are just not true about the story," he said. "I mean, there's a lot true, but this idea that myself or anybody forced or mandated or encouraged anybody else to cross that line, just isn't true. It's not true. Absolutely not true.

"We did what we had to do to win. It wasn’t legal. It probably wasn't the best decision, but look, we wouldn't have won had we not. But I wouldn't change a thing. I've said that three times. I would not change a thing," Armstrong said, pausing briefly between each word for emphasis.

"Most of my memories, my fondest memories – yeah, I could pick a few race highlights – but boy, I can tell you about the eight-hour day in the Pyrenees previewing Haute de Com in the pouring rain – pffft – the best," he said, tearing up as he spoke.

Armstrong also revealed his first encounters with performance enhancing drugs, a line he said he first crossed in 1991.

"I think I do," Armstrong said when Tirico asked if he remembered his first experience. "There are gateway drugs that maybe they weren’t banned, certainly weren’t detectable or tested for. The easiest way to think about it is, if you think it's going to help you, even if it's not detectable or banned, then you've crossed the line.

"It was probably '91, maybe, at an Italian stage race. And again, it's hard to differentiate, because I believe we weren't given anything banned, but the doctor walked in – and I was in the lead of the race, and I wanted to win the race – and he walked in and I said, 'Give me everything in the bag.' And he just laughed.

"But it was just probably some form of cortizone or, Armstrong said and then trailed off, failing to finish his through. "But the first time I took a legitimately banned substance was '93."

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Coros enters cycling industry with Dura GPS computer, boasts huge battery and impressive price

Is this the Visma-Lease a Bike Tour de France squad with Vingegaard and Van Aert?

Bradley Wiggins opens up about his ‘love-hate’ relationship with cycling as new details of financial difficulties emerge

Most Popular

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Entertainment

Where Is Lance Armstrong Now? All About the Former Cyclist's Life After His Doping Scandal

Lance Armstrong won a record seven consecutive Tour de France titles before being stripped of them following doping accusations in 2012

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/emily-krauser-author-bio-52802a232d284c7b87b50996d45a7e42.jpg)

Tom Able-Green /Allsport ; Ezra Shaw/Getty

Lance Armstrong ’s reputation was tarnished by his doping scandal, but he hasn’t stayed out of the spotlight.

The retired athlete was one of the most famous professional athletes of all time, elevating cycling’s international popularity. The height of Armstrong’s career came after he was diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996, when he was 25. After chemotherapy treatment, he founded the nonprofit Livestrong, won a record seven consecutive Tour de France titles between 1999 and 2005, reached A-list levels of celebrity and became known for his philanthropy.

He spent a decade denying that he took performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) before coming clean in a 2013 interview with Oprah Winfrey . During the sit-down, he admitted to using testosterone, human growth hormone and EPO and taking blood transfusions.

"This story was so perfect for so long. It's this myth, this perfect story, and it wasn't true," he told Winfrey. "I viewed this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times, and as you said, it wasn't as if I just said no and I moved off it."

The tell-all came shortly after the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) formally charged him with doping. Armstrong chose not to appeal and was stripped of all his titles since 1998, including the Tour de France wins and his Olympic medal. He also lost endorsement deals and was required to pay a $5 million settlement to the U.S. government in 2018.

In his personal life, the Texas-born athlete divorced his first wife, Kristin Richard — with whom he shares three children, son Luke and twin daughters Grace and Isabelle — in 2003 and soon after began dating Sheryl Crow . They got engaged in October 2005 and split in February 2006. He has since remarried, tying the knot with Anna Hansen Armstrong in August 2022. They have two children, son Max and daughter Olivia.

Armstrong also hasn't left the public eye — he now hosts two podcasts, THEMOVE and The Forward , and competed in the 2023 celebrity reality TV show Stars on Mars .

More than a decade after his doping scandal here’s everything to know about what Lance Armstrong is doing now.

Who is Lance Armstrong?

Doug Pensinger/Getty

Lance Armstrong is a former professional American cyclist.

The athlete was born and raised in Texas, began competing in 1990 and made his Olympic debut in Barcelona in 1992. Four years later, he won his second Tour DuPont and participated in the Olympics in Atlanta. But in October of 1996, his life and career paused when he was diagnosed at age 25 with advanced-stage testicular cancer.

“I will win,” Armstrong said during a news conference about his diagnosis, according to NBC Sports . “I intend to beat this disease, and further, I intend to ride again as a professional cyclist.”

He founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation, later renamed the Livestrong Foundation, in 1997 — the nonprofit became ubiquitous and known for its yellow rubber bracelets. Armstrong was declared cancer-free shortly after, began cycling professionally again in 1998 and won his first Tour de France in 1999.

"I hope it sends out a fantastic message to all survivors around the world. We can return to what we were before — and even better,” Armstrong said at the finish line, according to ESPN .

Mike Powell /Allsport

Between 1999 and 2005, he won the Tour de France a record seven consecutive times. Armstrong rose to fame quickly after his first win and became known as much for his athletic career as his philanthropy. He released an autobiography, It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life , in 2000.

Armstrong initially retired after the 2005 Tour de France but announced a comeback in 2008, saying in a video for Livestrong that he was doing so to raise cancer awareness. He finished third in the 2009 Tour de France and 23rd in 2010, which was his last. The then-pro cyclist announced he was retiring for a second time in 2011.

“I can’t say I have any regrets. It’s been an excellent ride. I really thought I was going to win another Tour,” Armstrong said, per The Associated Press .

What was Lance Armstrong accused of?

Tim De Waele/Getty

Starting as early as 1999, the former professional cyclist was accused multiple times of doping.

In August 2005, one month after Armstrong won his seventh Tour de France title, France’s daily sports newspaper L'Equipe reported that six of his urine samples from 1999 were retested and came back positive for EPO, an endurance-boosting hormone.

"This thing stinks," Armstrong said on Larry King Live at the time. "I've said it for longer than seven years: I have never doped. I can say it again. But I've said it for seven years; it doesn't help. But the fact of the matter is I haven't (doped)."

The allegation prompted an investigation by France's World Anti-Doping Agency, and in 2006, he maintained to NBC’s Ann Curry that he had never doped. The International Cycling Union exonerated him, and he returned to the Tour de France in 2009 and placed third. Armstrong has since said that this return led to his downfall.

“We wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t come back,” he told Winfrey in 2013.

PATRICK KOVARIK/AFP FILES/AFP/Getty

Floyd Landis, Armstrong’s former teammate, filed a complaint in 2010 and admitted to using PEDs while a part of the U.S. Postal Service team, of which Armstrong was the lead cyclist.

In June 2012, the USADA accused Armstrong of using, possessing and trafficking PEDs and covering up doping violations. Armstrong did not appeal. In a statement at the time, the cyclist said he stopped fighting the investigation because “there comes a point in every man’s life when he has to say, ‘Enough is enough.’ For me, that time is now.”

Armstrong was banned from competing professionally again, stripped of all results since 1998, including his seven Tour de France titles and Olympic medal, and required to return all prize money.

The federal government joined the civil lawsuit in 2013, months after his interview with Winfrey. It alleged that Armstrong had violated his contract and committed fraud when he lied to the public and USPS, which sponsored his team from 1996 to 2004 and paid $31 million in sponsor fees.

The lawsuit was settled in 2018 when Armstrong agreed to pay the U.S. government $5 million, according to CNN .

What has Lance Armstrong said about his doping scandal?

James Knowler, File/AP

Doping allegations plagued the bulk of Armstrong’s career, but for a decade, he denied them.

After the L'Equipe investigation was published in 2005, the retired athlete noted that he’d dealt with "slimy" French journalists since his first Tour de France but "this is perhaps the worst of it."

"If you consider my situation, a guy who comes back from arguably, you know, a death sentence, why would I then enter into a sport and dope myself up and risk my life again?” Armstrong said on Larry King Live in 2005. “That's crazy. I would never do that. No. No way."

During the interview, he said he did use EPOs as part of his chemotherapy regimen as the drug boosts red blood cell counts but denied using them for competitions.

On his website in 2012, he accused the USADA of wanting to “dredge up discredited allegations,” which he said were “baseless” and “motivated by spite.”

“I have never doped, and, unlike many of my accusers, I have competed as an endurance athlete for 25 years with no spike in performance, passed more than 500 drug tests and never failed one,” he said.

That same year, however, he came clean in a sit-down interview with Winfrey. It was the first time Armstrong publicly admitted to doping.

George Burns/Oprah Winfrey Network/Getty

“This is too late, it’s too late for probably most people. And that’s my fault,” he said, per CNN. “[This was] one big lie, that I repeated a lot of times.”

Describing himself as a “fighter,” “humanitarian” and a “jerk,” he admitted to being “a bully ... in the sense that I tried to control the narrative” and talked about getting lost in his own story of overcoming cancer, a once-happy marriage and his international professional success.

He also noted he let down the fans who had supported him all those years. “They have every right to feel betrayed, and it’s my fault,” he said. “I will spend the rest of my life ... trying to earn back trust and apologize to people.

Armstrong told Stern in 2017 that the now-infamous conversation may have been not only “too soon” but “too detailed and too shocking for a lot of people,” but that “it had to happen.”

“The reason I decided to sit with her is because I had an existing relationship with her and I like Oprah and I trust her, but I knew I was going to get sued. When the report came out and they stripped the titles, I f------ knew they were lining up,” he said, later adding, “I left there feeling wow this is pretty good and the reaction was brutal.”

He was also concerned with how his children would react to the news, noting it was “not a one-time conversation.”

“The older kids were old enough to kind of live it with me and there was that conversation and there was therapy,” he said. “There was work. It’s a process.”

During an interview with Bill Maher on the Club Random podcast in 2023, Armstrong explained how he got away with cheating.

“One of the lines was, ‘I've been tested 500 times. I've never failed a drug test.’ That's not a lie. That is the truth. There was no way around the test,” he said, noting that he did the math to ensure the tests wouldn’t pick up the drugs.

In a March 2024 appearance on The Great Unlearn podcast, Armstrong said that in the years after admitting he had doped, he experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sought intensive one-on-one treatment.

“I went from hero to zero overnight,” he said. “A lot of people applauded that. A lot of people thought that was funny. A lot of people thought that I deserved that. And a lot of that’s right. I didn’t think it was funny, but I certainly deserved it."

Who is Lance Armstrong's wife?

Neilson Barnard/Getty

Armstrong married Anna, a yoga instructor, in a small ceremony at Château la Coste in France in August 2022. The couple got engaged in 2017 after meeting a decade earlier. Their son Max was born in 2009, and they welcomed daughter Olivia in 2010.

“Anna, you have been my absolute rock the past 14 years and let me be clear, I would not have survived them without you,” Armstrong wrote in part on Instagram alongside a photo from their wedding. “I am so proud of the couple we have become - It took us doing the work, the really hard work, and I am so glad that we did.”

Armstrong was previously married to Richard for five years before divorcing in 2003. They share three children — son Luke, born in 1999, and twin daughters Grace and Isabelle, born in 2001.

At the height of his fame, he also dated fellow celebrities, including Sheryl Crow , Kate Hudson and Tory Burch .

Where is Lance Armstrong now?

Lance Armstrong Instagram

Armstrong hasn’t stayed out of the spotlight since his doping scandal but has pivoted into new entertainment spaces.

After 15 years of laying low in Aspen, Colo., with his family, he moved back to Austin where he was based during his cycling career.

The former Olympian now hosts two podcasts: THEMOVE , which focuses on iconic cycling races, and The Forward , which is interview-centric. In 2023, he announced that he was launching a series for the latter that “with an open mind” would “dive into” the debate surrounding transgender athletes. The inaugural episode featured Caitlyn Jenner .

The father of five was the focus of the 2020 documentary Lance , part of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series and appeared in season 1 of Fox’s reality TV show, Stars on Mars in 2023.

Though Armstrong cannot return to cycling professionally, after a years-long break, he took up the sport again .

“For three or four years, I hated cycling because of what my life has looked like for the last four or five years,” he said on The Howard Stern Show in 2017. “Just like with any kind of breakup, there are hard feelings.”

Related Articles

Michael Jordan's Boat Fails To Place In Fishing Tournament

Chiefs' Isaiah Buggs Accused Of Dragging Mother Of His Child Down Stairs Before Arrest

Jake Paul Gets 'Platinum' Mike Perry To Replace Mike Tyson For July 20 Fight

Gisele Bündchen, Joaquim Valente Spend Time With Tom Brady's Kids on Father's Day

Rising Star Athlete Jackson James Rice Dead At 18, Weeks Before Olympic Debut

Lance armstrong competes in grueling race, wins age group, lance armstrong competes in grueling nyc race ... no bike, no problem.

Lance Armstrong retired from cycling more than a decade ago, but the 7x Tour de France champ is still competing, and winning, emerging victorious in his age group in a grueling race in New York City over the weekend!

52-year-old Armstrong competed in HYROX NYC -- a global fitness competition that blends a bunch of different (and really hard) movements/exercises -- including running, rows, burpees, sandbag lunges, sled pulls, and much more.

And, in the near 90-degree NYC heat ... borderline torture! 😄

Lance finished the competition in 1:12:05 ... nearly 4 1/2 minutes in front of the next guy in his age group.

We even got some video of Lance from fellow competitor, Mark D. LoBiondo , from Ironbound Performance gym in Jersey City.

Age groups aside, Armstrong finished in 94th place out of 892 competitors in the men's open division.

With the impressive performance, LA also qualified for the HYROX World Championships -- where the top athletes from events around the world come together to compete.

The first place finisher in the men's pro division was Jake Dearden with a time of 58 minutes and 12 seconds. The world record for the HYROX Men's Open is 50:38 minutes.

- Share on Facebook

related articles

Lance Armstrong Confronted Over 'Disheartening' Trans Remarks on 'Stars on Mars'

Marshawn Lynch, Lance Armstrong Wield Massive Flamethrowers On 'Stars On Mars'

Old news is old news be first.

Is the Surge in American Cycling Talent Signaling the Emergence of a New Era?

With standout performances from Matteo Jorgenson, Sepp Kuss, and Brandon McNulty, we examine the potential for a transformative period in U.S. cycling.

Earlier in the 2023 season, Brandon McNulty , a talent hailing from Phoenix, Arizona, won a stage at the Giro d’Italia, and Neilson Powless —the first Native American to compete in the Tour de France —electrified audiences with his daring performances, including a memorable stint in the polka dot jersey at the French Grand Tour.

Adding to the momentum, Magnus Sheffield , from Pittsford, New York, narrowly missed a victory by sixteen seconds in this year’s Ghent-Wevelgem . And, of course, Matteo Jorgenson , whose audacious attack on the Puy de Dôme during last summer’s Tour de France catapulted him to prominence. He subsequently notched impressive victories at Paris-Nice and Dwars door Vlaanderen this spring and just last week finished in second place at the Critérium du Dauphiné, which immediately forced the question as to whether he (or Kuss) would be Visma-Lease a Bike’s GC man in this summer’s Tour de France.

All of this recent success begs the question: Are we on the precipice of an exciting new era of American cycling?

It certainly feels that way, and much of that feeling has to do with this sudden concentration of success. Sure, Chris Horner won a La Vuelta a España in 2013. But his win came at a time when few other Americans were having success at the sport’s highest level (it was also in the heat of the USADA investigation that arguably changed cycling—and the perception of U.S. cycling—forever).