Advertisement

Ecotourism and sustainable development: a scientometric review of global research trends

- Published: 21 February 2022

- Volume 25 , pages 2977–3003, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Lishan Xu 1 , 2 ,

- Changlin Ao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8826-7356 1 , 3 ,

- Baoqi Liu 1 &

- Zhenyu Cai 1

20k Accesses

21 Citations

Explore all metrics

With the increasing attention and awareness of the ecological environment, ecotourism is becoming ever more popular, but it still brings problems and challenges to the sustainable development of the environment. To solve such challenges, it is necessary to review literature in the field of ecotourism and determine the key research issues and future research directions. This paper uses scientometrics implemented by CiteSpace to conduct an in-depth systematic review of research and development in the field of ecotourism. Two bibliographic datasets were obtained from the Web of Science, including a core dataset and an expanded dataset, containing articles published between 2003 and 2021. Our research shows that ecotourism has been developing rapidly in recent years. The research field of ecotourism spans many disciplines and is a comprehensive interdisciplinary subject. According to the research results, the evolution of ecotourism can be roughly divided into three phases: human disturbance, ecosystem services and sustainable development. It could be concluded that it has entered the third stage of Shneider’s four-stage theory of scientific discipline. The research not only identifies the main clusters and their advance in ecotourism research based on high impact citations and research frontier formed by citations, but also presents readers with new insights through intuitive visual images.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainable land use and management research: a scientometric review

Navigating the landscape of global sustainable livelihood research: past insights and future trajectory

Land quality evaluation for sustainable development goals: a structured review using bibliometric and social network analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ecotourism, which has appeared in academic literature since the late 1980s, is a special form of nature-based tourism that maintains the well-being of the local community while protecting the environment and provides tourists with a satisfying nature experience and enjoyment (Ceballos-Lascuráin, 1996 ; Higgins, 1996 ; Orams, 1995 ). With years of research and development, ecotourism has risen to be a subject of investigation in the field of tourism research (Weaver & Lawton, 2007 ). In 2002, the United Nations declared it the International Year of Ecotourism (IYE), and the professional Journal of Ecotourism was established in the same year.

With the progress and maturity of ecotourism as an academic research field, countless scholars have put forward standards and definitions for ecotourism (Sirakaya et al., 1999 ; Wight, 1993 ). The main objectives of ecotourism emphasize long-term sustainable development (Whitelaw et al., 2014 ), including the conservation of natural resources, the generation of economic income, education, local participation and the promotion of social benefits such as local economic development and infrastructure (Ardoin et al., 2015 ; Coria & Calfucura, 2012 ; Krüger, 2005 ; Oladeji et al., 2021 ; Ross & Wall, 1999 ; Valdivieso et al., 2015 ). It can also boost rural economies and alleviate poverty in developing countries (Snyman, 2017 ; Zhong & Liu, 2017 ).

With unrestricted increasing attention to the ecological environment and the improvement of environmental awareness, ecotourism is becoming ever more prevalent, and the demand for tourism is increasing year by year (CREST, 2019 ). This increase, however, leads to a number of environmental, social and economic challenges in the development of ecotourism. For example, due to the low public awareness of ecotourism, the increase in tourists has brought a series of negative impacts on the local ecological environment, culture and economy, including disrespect for local culture and environmental protection, as well as more infrastructure construction and economic burden to meet the needs of tourists (Ahmad et al., 2018 ; Chiu et al., 2014 ; Shasha et al., 2020 ; Xu et al., 2020 ). Such challenges and contradictions are urgent problems to be tackled by the sustainable development of ecotourism. Especially against the backdrop of the current pandemic, tourism has experienced a severe blow, but climate change and other environmental issues have not been improved (CREST, 2020 ). In this context, facing these challenges and difficulties, it is essential to re-examine the future development path of ecotourism, to explore how government agencies can formulate appropriate management policies while preserving the environment and natural resources to support sustainable tourism development. Accordingly, it is necessary to consult literature in the field of ecotourism to understand the research progress and fundamental research issues, to identify challenges, suitable methods and future research direction of ecotourism.

Some previous reviews of ecotourism offer a preview of research trends in this rapidly developing area. Weaver and Lawton ( 2007 ) provide a comprehensive assessment of the current state and future progress of contemporary ecotourism research, starting with the supply and demand dichotomy of ecotourism, as well as fundamental areas such as quality control, industry, external environment and institutions. Ardoin et al. ( 2015 ) conducted a literature review, analyzing the influence of nature tourism on ecological knowledge, attitudes, behavior and potential research into the future. Niñerola et al. ( 2019 ) used the bibliometric method and VOSviewer to study the papers on sustainable development of tourism in Scopus from 1987 to 2018, including literature landscape and development trends. Shasha et al. ( 2020 ) used bibliometrics and social network analysis to review the research progress of ecotourism from 2001 to 2018 based on the Web of Science database using BibExcel and Gephi and explored the current hot spots and methods of ecotourism research. These reviews have provided useful information for ecotourism research at that time, but cannot reflect the latest research trends and emerging development of ecotourism either of timeliness, data integrity, research themes or methods.

This study aims to reveal the theme pattern, landmark articles and emerging trends in ecotourism knowledge landscape research from macro- to micro-perspectives. Unlike previous literature surveys, from timeliness, our dataset contains articles published between 2003 and 2021, and it will reveal more of the trends that have emerged over the last 3 years. Updating the rapidly developing literature is important as recent discoveries from different areas can fundamentally change collective knowledge (Chen et al., 2012 , 2014a ). To ensure data integrity, two bibliographic datasets were generated from Web of Science, including a core dataset using the topic search and an expanded dataset using the citation expansion method, which is more robust than defining rapidly growing fields using only keyword lists (Chen et al., 2014b ). And from the research theme and method, our review focuses on the area of ecotourism and is instructed by a scientometric method conducted by CiteSpace, an analysis system for visualizing newly developing trends and key changes in scientific literature (Chen et al., 2012 ). Emerging trends are detected based on metrics calculated by CiteSpace, without human intervention or working knowledge of the subject matter (Chen et al., 2012 ). Choosing this approach can cover a more extensive and diverse range of related topics and ensure repeatability of analysis with updated data (Chen et al., 2014b ).

In addition, Shneider’s four-stage theory will be used to interpret the results in this review. According to Shneider’s four-stage theory of scientific discipline (Shneider, 2009 ), the development of a scientific discipline is divided into four stages. Stage I is the conceptualization stage, in which the objects and phenomena of a new discipline or research are established. Stage II is characterized by the development of research techniques and methods that allow researchers to investigate potential phenomena. As a result of methodological advances, there is a further understanding of objects and phenomena in the field of new subjects at this stage. Once the techniques and methods for specific purposes are available, the research enters Stage III, where the investigation is based primarily on the application of the new research method. This stage is productive, in which the research results have considerably enhanced the researchers’ understanding of the research issues and disclosed some unknown phenomena, leading to interdisciplinary convergence or the emergence of new research directions or specialties. The last stage is Stage IV, whose particularity is to transform tacit knowledge into conditional knowledge and generalized knowledge, so as to maintain and transfer the scientific knowledge generated in the first three stages.

The structure of this paper is construed as follows. The second part describes the research methods employed, the scientometric approach and CiteSpace, as well as the data collection. In the third part, the bibliographic landscape of the core dataset is expounded from the macroscopic to the microscopic angle. The fourth part explores the developments and emerging trends in the field of ecotourism based on the expanded dataset and discusses the evolution phase of ecotourism. The final part is the conclusion of this study. Future research of ecotourism is prospected, and the limitations of this study are discussed.

2 Methods and data collection

2.1 scientometric analyses and citespace.

Scientometrics is a branch of informatics that involves quantitative analysis of scientific literature in order to capture emerging trends and knowledge structures in a particular area of study (Chen et al., 2012 ). Science mapping tools generate interactive visual representations of complex structures by feeding a set of scientific literature through scientometrics and visual analysis tools to highlight potentially important patterns and trends for statistical analysis and visualization exploration (Chen, 2017 ). At present, scientometrics is widely used in many fields of research, and there are also many kinds of scientific mapping software widely used by researchers and analysts, such as VosViewer, SCI2, HistCite, SciMAT, Gephi, Pajek and CiteSpace (Chen, 2011 , 2017 ; Chen et al., 2012 ).

Among these tools, CiteSpace is known for its powerful literature co-citation analysis, and its algorithms and features are constantly being refined as it continues to evolve. CiteSpace is a citation visual analysis software developed under the background of scientometrics and data visualization to analyze the basics that are included in scientific analysis (Chen, 2017 ; Chen et al., 2012 ). It is specialized designed to satisfy the need for systematic review in rapidly changing complicated areas, particularly with the ability to identify and explain emerging trends and transition patterns (Chen et al., 2014a ). It supports multiple types of bibliometric research, such as collaborative network analysis, co-word analysis, author co-citation analysis, document co-citation analysis, and temporal and spatial visualization (Chen, 2017 ). Currently, CiteSpace has been extensively used in more than 60 fields, including computer science, information science, management and medicine (Abad-Segura et al., 2019 ; Chen, 2017 ).

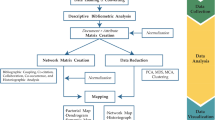

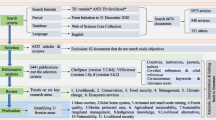

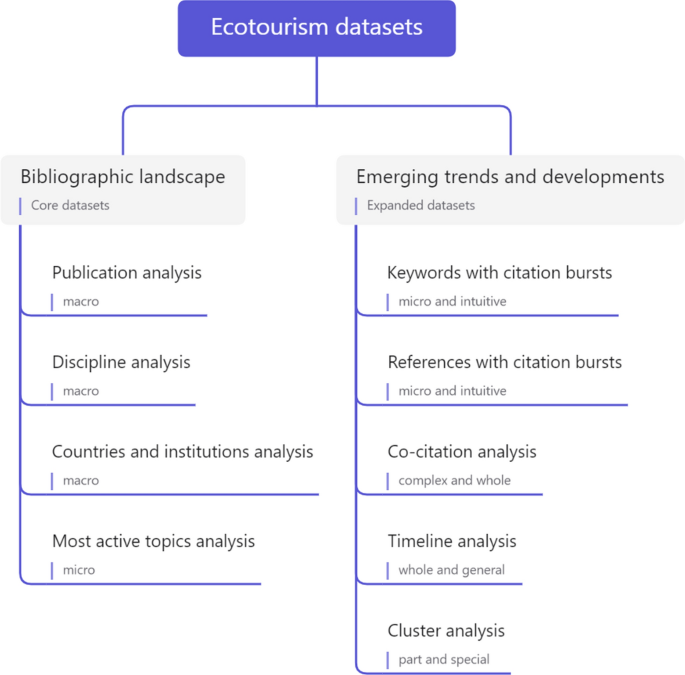

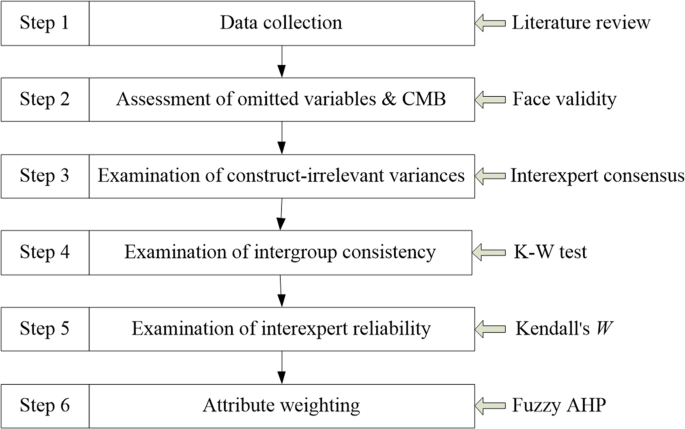

In this paper, we utilize CiteSpace (5.8.R1) to analyze acquired bibliographies of ecotourism to study emerging trends and developments in this field. From macro to micro, from intuitive to complex, from whole to part and from general to special, the writing ideas are adopted. Figure 1 presented the specific research framework of this study.

The research framework of this study

2.2 Data collection

Typical sources of scientific literature are Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Considering the quantity and quality of data, the Web of Science database was expected to provide the original data in this research. In order to comprehend the research status and development trends of ecotourism, this study systematically reviewed the ecotourism literature collected on the Web of Science Core Collection. The Web of Science Core Collection facilitates access to the world’s leading scholarly journals, books and proceedings of conferences in the sciences, social sciences, art, and humanities, as well as access to their entire citation network. It mainly includes Science Citation Index Expanded from 2003 to current and Social Sciences Citation Index from 2004 to present. Therefore, the data obtained in this study are from 2003 and were consulted on June 3, 2021.

In the process of data retrieval, it is frequently confronted with the choice between recall rate and precision rate. To address the problem of low recall rate in keyword or topic retrieval, Chen et al. ( 2014a , b ) expanded the retrieval results through ‘citation expansion’ and ‘comprehensive topic search’ strategies. However, when the recall rate is high, the accuracy rate will decrease correspondingly. In practical standpoint, instead of refining and cleaning up the original search results, a simpler and more efficient way is to cluster or skip these unrelated branches. Priority should be placed on ensuring recall rate, and data integrity is more important than data for accuracy. Therefore, two ecotourism documentation datasets, the core dataset and the expanded dataset, were obtained from the Web of Science by using comprehensive topic search and citation expansion method. The latter approach has been proved more robust than using keyword lists only to define fast-growing areas (Chen et al., 2014b ). A key bibliographic landscape is generated based on the core dataset, followed by more thorough research of the expanded dataset.

2.2.1 The core dataset

The core dataset was derived through comprehensive subject retrieval in Web of Science Core Collection. The literature type was selected as an article or review, and the language was English. The period spans 2003 to 2021. The topic search query is composed of three phrases of ecotourism: ‘ ecotour* ’ OR ‘ eco-tour* ’ OR ‘ ecological NEAR/5 tour* ’. The wildcard * is used to capture related variants of words, for example, ecotour, ecotourism, ecotourist and ecotourists. The related records that are requested include finding these terms in the title, abstract or keywords. The query yielded 2991 original unique records.

2.2.2 The expanded dataset

The expanded dataset includes the core dataset and additional records obtained by reference link association founded on the core dataset. The principle of citation expansion is that if an article cites at least one article in the core dataset, we can infer that it is related to the topic (Garfield, 1955 ). The expanded dataset is comprised of 27,172 unique records, including the core dataset and the articles that cited them. Both datasets were used for the following scientometrics analysis.

3 Bibliographic landscape based on the core dataset

The core dataset consists of a total of 2991 literature from 2003 to 2021. This study utilized the core dataset to conduct an overall understanding of the bibliographic landscape in the field of ecotourism.

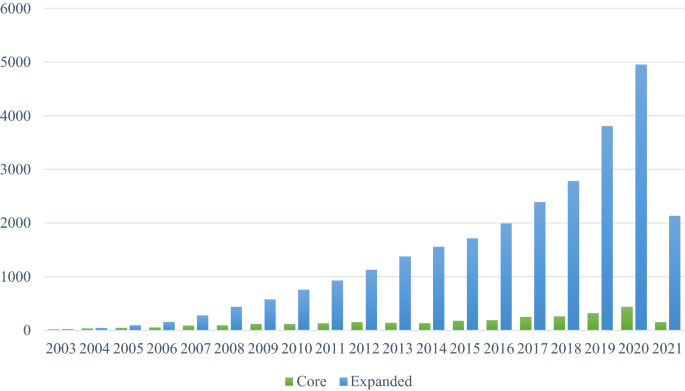

3.1 Landscape views of core dataset

The distribution of the yearly publication of bibliographic records in the core and expanded datasets is presented in Fig. 2 . It can be observed that the overall number of ecotourism-related publications is on the rise, indicating that the scholarly community is increasingly interested in ecotourism. After 2018, the growth rate increased substantially. And in 2020, the number of publications in the expanded dataset is close to 5000, almost double that of 2017 and 5 times that of 2011. This displays the rapid development of research in the field of ecotourism in recent years, particularly after 2018, more and more researchers began to pay attention to this field, which also echoes the trend of global tourism development and environmental protection. With the increase in personal income, tourism has grown very rapidly, and with it, tourism revenue and tourist numbers, especially in developing states. For instance, the number of domestic tourists in China increased from 2.641 billion in 2011 to 6.06 billion in 2019, and tourism revenue increased from 1930.5 billion RMB in 2011 to 5725.1 billion RMB in 2019 (MCT, 2021 ). However, due to the lack of effective management and frequent human activities, the rapid development of tourism has led to various ecological and environmental problems, which require corresponding solutions (Shasha et al., 2020 ). This has played an active role in promoting the development of ecotourism and triggered a lot of related research. In addition, since 2005, the expanded dataset has contained numerous times as many references as the core dataset, demonstrating the importance of using citation expansion for literature retrieval in scientometric review studies.

The distribution of bibliographic records in core and expanded dataset. Note The data were consulted on June 3, 2021

The data were consulted on June 3, 2021

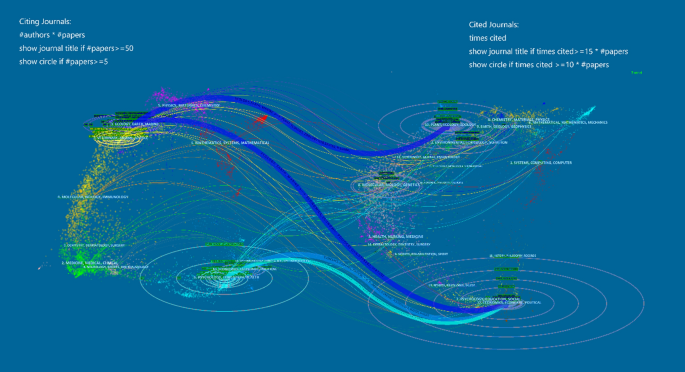

The dual-map overlay of scientific map literature as Fig. 3 shows, against the background of global scientific map from more than 10,000 journals covered by Web of Science, represents the distribution and connections on research bases and application fields across the entire dataset of the research topics (Chen & Leydesdorff, 2014 ). Colored lines are citation links, and numbered headings are cluster labels. On the left side is the journal distribution which cites literature, regarding the field application of ecotourism, mainly covers multiple disciplines such as 3. Ecology, Earth, Marine, 6. Psychology, Education, Health, 7. Veterinary, Animal Science and 10. Economics, Economic and Political. On the right side is the distribution of journals of cited literature, representing the research basis of ecotourism. As can be observed from the figure, ecotourism research is based on at least five disciplines on the right, including 2. Environmental, Toxicology, Nutrition, 7. Psychology, Education, Social, 8. Molecular, Biology, Genetics, 10. Plant, Ecology, Zoology and 12. Economics, Economic, Political. It can be viewed that the research field of ecotourism spans multiple disciplines and is a comprehensive and complex subject. The dual-map overlay provides a global visualization of literature growth of the discipline level.

A dual-map overlay of ecotourism literature

The total number of papers issued by a country or an institution reflects its academic focus and overall strength, while centrality indicates the degree of academic cooperation with others and the influence of published papers. The top 15 countries and institutions for the number of ecotourism papers published from 2003 to 2021 are provided in Table 1 . Similar to the study of Shasha et al. ( 2020 ), the ranking of the top six countries by the number of publications remains unchanged. As can be seen from the table, the USA ranks first in the world, far ahead in both the number of publications and the centrality. China ranks second in global ecotourism publications, followed by Australia, England, South Africa and Canada. While the latest data show that Taiwan (China), Turkey and South Korea appear on the list. Overall, the top 15 countries with the most publications cover five continents, containing a number of developed and developing, which shows that ecotourism research is receiving global attention. In terms of international academic cooperation and impact of ecotourism, Australia and England share second place, Italy and France share fourth place, followed by South Africa and Spain. China’s centrality is relatively low compared to the number of publications, ranking eighth. Academic cooperation between countries is of great significance. Usually, countries with high academic publishing level cooperate closely due to similar research interests. International academic cooperation has enhanced each other’s research capacity and promoted the development of ecotourism research. Therefore, although some countries have entered this list with the publication number, they should attach importance to increase academic cooperation with other countries and improving the international influence of published papers.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences and its university are the most prolific when it draws to institutions’ performance. It is the most important and influential research institute in China, especially in the field of sustainable development science. Australia has four universities on the list, with Griffith University and James Cook University in second and third place. USA also includes four universities, with the University of Florida in fourth place. South Africa, a developing country, gets three universities, with the University of Cape Town and the University of Johannesburg fifth and sixth, respectively. In comparison with previous studies (Shasha et al., 2020 ), Iran and Mexico each have one university in the ranking, replacing two universities in Greece, which means that the importance and influence of developing countries in the field of ecotourism is gradually rising. Based on the above results, it can be summarized that the USA, China, Australia and South Africa are relatively active countries in the field of ecotourism, and their development is also in a relatively leading position.

3.2 Most active topics

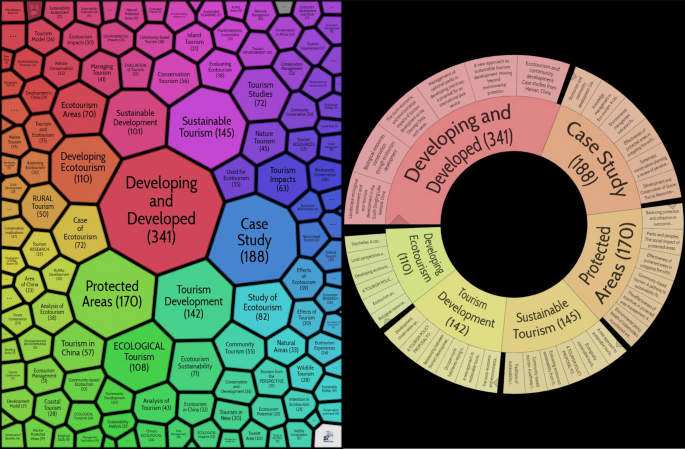

The foam tree map and the pie chart of the focal topics of ecotourism based on the core dataset generated by Carrot2 through the title of each article is illustrated in Fig. 4 . Developing and developed, case study, protected areas, sustainable tourism, tourism development and developing ecotourism are leading topics in the field of ecotourism research, as well as specific articles under the main topics. The lightweight view generated by Carrot2 provides a reference for the research, and then, co-word analysis is employed to more specifically reflect the topics in the research field.

Foam tree map and pie chart of major topics on ecotourism

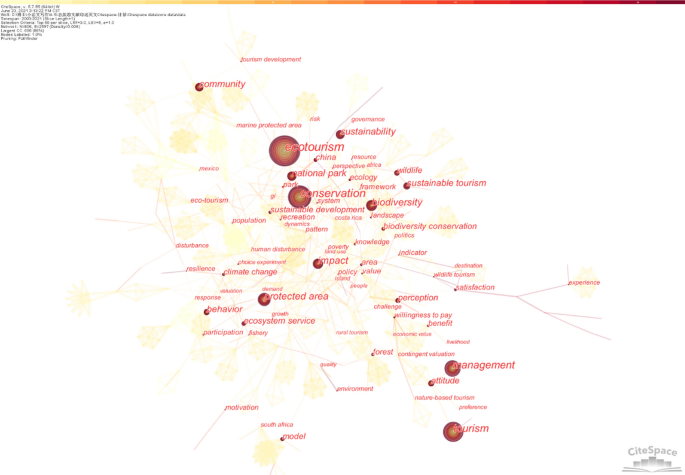

The topics covered by ecotourism could be exposed by the keywords of the articles in the core dataset. Figure 5 displays the keywords analysis results generated based on the core dataset. From the visualization results in the figure, it can infer that ecotourism, conservation, tourism, management, protected area, impact, biodiversity, sustainability, national park and community are the ten most concerned topics. Distinct colors set out at the time of co-citation keywords first appear, and yellow is generated earlier than red. In addition, Fig. 5 can also reflect the development and emerging topics in the research field, such as China, Mexico, South Africa and other hot countries for ecotourism research; ecosystem service, economic value, climate change, wildlife tourism, rural tourism, forest, marine protected area and other specific research directions; valuation, contingent valuation, choice experiment and other research methods; willingness to pay, preference, benefit, perception, attitude, satisfaction, experience, behavior, motivation, risk, recreation and other specific research issues.

A landscape view of keywords based on the core dataset

4 Emerging trends and developments based on the expanded dataset

The expanded dataset, consisting of 27,172 records, is approximately nine times larger than the core dataset. This research applies the expanded dataset to profoundly explore the emerging trends and developments of ecotourism.

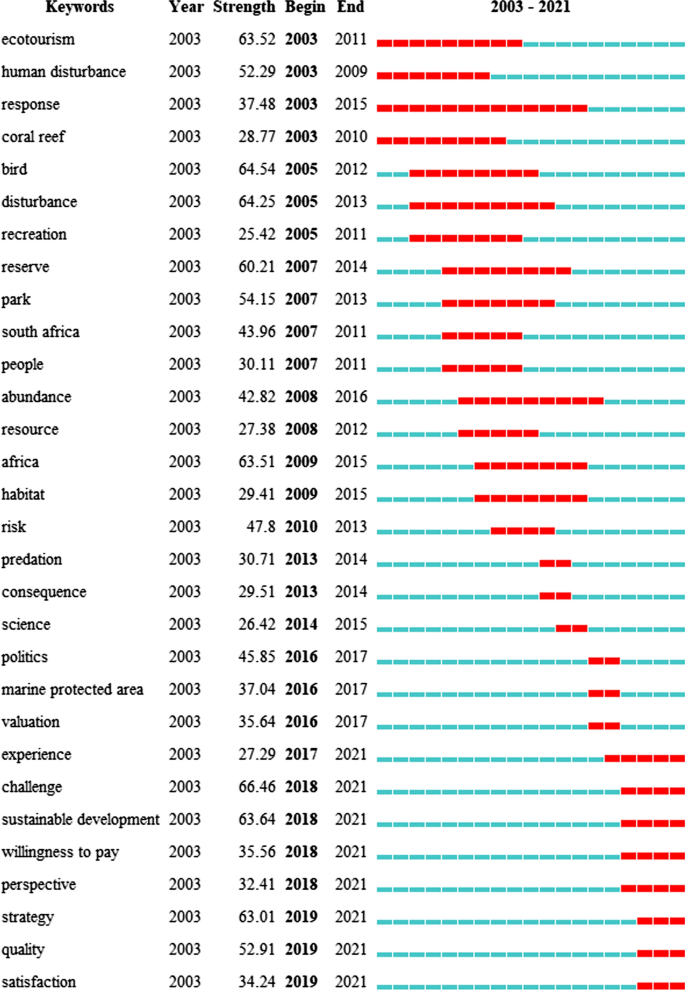

4.1 Keywords with citation bursts

Detection of citation bursts can indicate both the scientific community’s interest in published articles and burst keywords as an indicator of emerging tendencies. Figure 6 displays the top 30 keywords with the strongest citation bursts in the expanded dataset. Since 2003, a large number of keywords have exploded. Among them, the strongest bursts include ecotourism, bird, disturbance, reserve, Africa, challenge, sustainable development and strategy. Keywords with citation burst after 2017 are experience, challenge, sustainable development, willingness to pay, perspective, strategy, quality and satisfaction, which have continued to this day. The results indicate dynamic development and emerging trends in research hotspots in the field of ecotourism.

Top 30 keywords with the strongest citation bursts

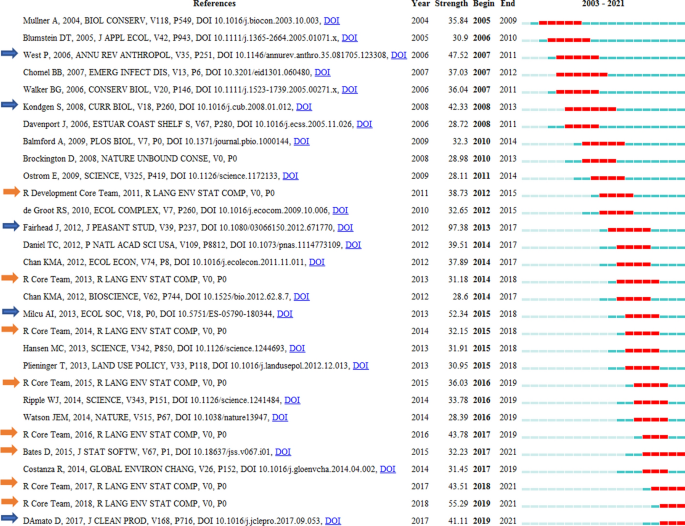

4.2 References with citation bursts

Figure 7 sets out the top 30 references in the expanded dataset with citation bursts. The articles with the fastest growing citations can also contribute to describe the dynamics of a field. References with high values in strength column are important milestones of ecotourism research. The two articles with strong citation bursts prior to 2010 focused on the human impact on the environment and animals. West et al. ( 2006 ) discussed the relationship between parks and human beings and the social impact of protected areas, and Köndgen et al. ( 2008 ) studied the decline of endangered great apes caused by a human pandemic virus. The paper with the strongest citation burst in the entire expanded dataset was released by Fairhead et al. ( 2012 ), which looked at ‘green grabbing,’ the appropriation of land and resources for environmental purposes. Milcu et al. ( 2013 ) conducted a semi-quantitative review of publications dealing with cultural ecosystem services with the second strongest citation burst, which concluded that the improvement of the evaluation method of cultural ecosystem service value, the research on the value of cultural ecosystem service under the background of ecosystem service and the clarification of policy significance were the new themes of cultural ecosystem service research. In addition, many articles with citation burst discussed the evaluation method of ecosystem services value (Costanza et al., 2014 ; Groot et al., 2010 ), the evaluation of cultural ecosystem service value (Plieninger et al., 2013 ) and its role in ecosystem service evaluation (Chan et al., 2012 ; Chan, Guerry, et al., 2012 ; Chan, Satterfield, et al., 2012 ; Chan, Satterfield, et al., 2012 ; Daniel et al., 2012 ). The most fresh literature with strong citation burst is the article of D’Amato et al. ( 2017 ) published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, which compared and analyzed sustainable development avenues such as green, circular and bio economy. In addition, it is worthwhile noting the use of R in ecotourism, with the persuasive citation burst continuing from 2012 to the present, as indicated by the orange arrow in Fig. 7 .

Top 30 references with the strongest citation bursts

4.3 Landscape view of co-citation analysis

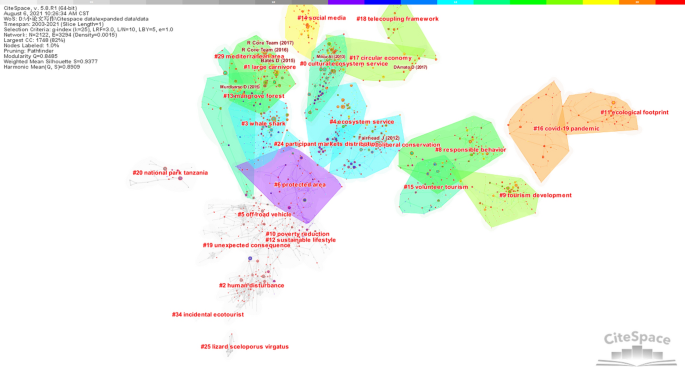

The landscape view of co-citation analysis of Fig. 8 is generated based on the expanded dataset. Using g -index ( k = 25) selection criteria in the latest edition of CiteSpace, an annual citation network was constructed. The final merged network contained 3294 links, 2122 nodes and 262 co-citation clusters. The three largest linked components cover 1748 connected nodes, representing 82% of the entire network. The modularization degree of the synthetic network is 0.8485, which means that co-citation clustering can clearly define each sub-field of ecotourism. Another weighted mean silhouette value of the clustering validity evaluation is 0.9377, indicating that the clustering degree of the network is also very superior. The harmonic mean value amounts to 0.8909.

A landscape view of the co-citation network based on the expanded dataset

In the co-citation network view, the location of clusters and the correlation between clusters can show the intellectual structure in the field of ecotourism, so that readers can obtain an overall understanding of this field. The network falls into 25 co-citation clusters. The tags for each cluster are generated founded on the title, keywords and abstract of the cited article. Color-coded areas represent the time of first appeared co-citation links, with gray indicating earlier and red later. The nodes in the figure with red tree rings are references to citation bursts.

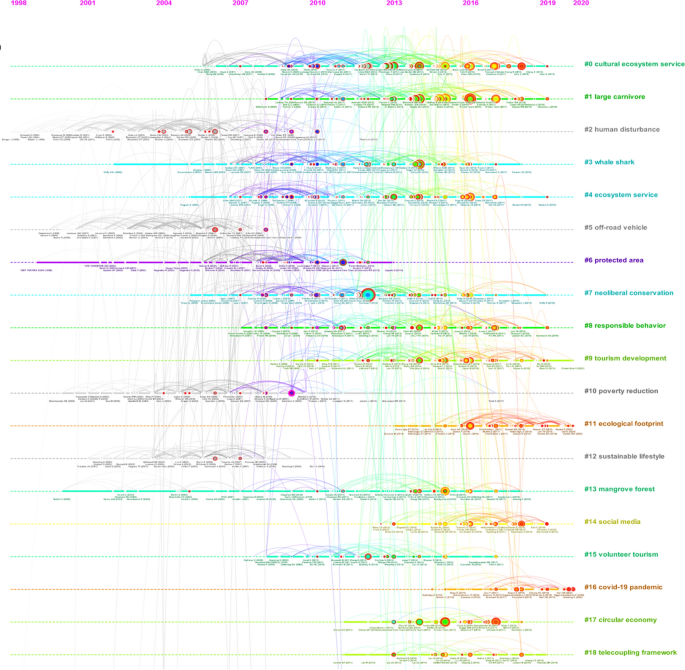

4.4 Timeline view

In order to further understand the time horizon and study process of developing evolution on clusters, after the generation of co-citation cluster map, the Y -axis is cluster number and the year of citation publication is X -axis, so as to obtain the timeline view of the co-citation network, shown as Fig. 9 . Clusters are organized vertically from largest to smallest. The color curve represents co-citation link coupled with corresponding color year, with gray representing earlier and red representing newer. Larger nodes and nodes with red tree rings indicate high citation or citation burst. The three most cited references of the year demonstrate below each node, in vertical order from least to most.

A timeline visualization of the largest clusters

The timeline view provides a reasonably instinctual and insightful reference to understand the evolutionary path of every subdomain. Figure 9 shows 19 clusters ranging from #0 to #18, with #0 being the largest cluster. As can be seen from the figure, the sustainability and activeness of each cluster are contrasting. For example, the largest cluster has been active since 2006, while the gray and purple clusters are no longer active.

4.5 Major clusters

Taking clustering as a unit and analyzing at the level of clustering, specifically selecting large or new type clustering, is the foothold of co-citation analysis, which can help to understand the principal and latest research fields related to ecotourism. Table 2 displays a summary of the foremost 19 clusters, the first nine of which are all over 100 in size. The silhouette score of all clusters is greater than 0.8, indicating that the homogeneity of each cluster is high. The mean year is the average of the publication dates of references in the cluster. By combining the results in Table 2 , Figs. 8 and 9 , it can be observed that the five largest clusters are #0 cultural ecosystem services, #1 large carnivore, #2 human disturbance, #3 whale shark and #4 ecosystem service. A recent topic is cluster #16 COVID-19 pandemic. #11 Ecological footprint and #14 social media are two relatively youthful fields.

The research status of a research field can be demonstrated by its knowledge base and research frontier. The knowledge base consists of a series of scholarly writing cited by the corresponding article, i.e., cited references, while the research frontier is the writing inspired by the knowledge base, i.e., citing articles. Distinct research frontiers may come from the same knowledge base. Consequently, each cluster is analyzed based on cited references and citing articles. The cited references and citing articles of the five largest clusters are shown in Online Appendix A. Fig a) lists the 15 top cited references with the highest Σ (sigma) value in the cluster, where Σ value indicates that the citation is optimal in terms of the comprehensive performance of structural centrality and citation bursts. Fig b) shows the major citing articles of cluster. The citation behavior of these articles determines the grouping of cited literature and thus forms the cluster. The coverage is the proportion of member citations cited by citing articles.

4.6 Phase evolution research

Through the above analysis of the core dataset and the expanded dataset of ecotourism, we can see the development and evolution of the research field of ecotourism. The research process of ecotourism has gone through several stages, and each stage has its strategic research issues. Research starts with thinking about the relationship between humans and nature, moves to study it as a whole ecosystem, and then explores sustainable development. Hence, the evolution of ecotourism can be roughly parted into three phases.

4.6.1 Phase I: Human disturbance research stage (2003–2010)

This phase of research concentrates on the influence of human activities such as ecotourism on the environment and animals. Representative keywords of this period include ecotourism, human disturbance, response, coral reef, bird, disturbance, recreation, reserve, park, South Africa and people. Representative articles are those published by West et al. ( 2006 ) and Köndgen et al. ( 2008 ) of human impact on the environment and animals. The representative clustering is #2 human disturbance, which is the third largest one, consisting of 130 cited references from 1998 to 2012 with the average year of 2004. This cluster has citation bursts between 2002 and 2010 and has been inactive since then. As showed in Fig S3 a) and b), the research base and frontier are mainly around the impact of human disturbances such as ecotourism on biology and the environment (McClung et al., 2004 ). And as showed in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 , clusters closely related to #2 belong to this phase and are also no longer active, such as #5 off-road vehicle, #6 protected area, #10 poverty reduction and #12 sustainable lifestyle.

4.6.2 Phase II: Ecosystem services research stage (2011–2015)

In this stage, the content of ecotourism research is diversified and exploded. The research is not confined to the relationship between humans and nature, but begins to investigate it as an entire ecosystem. In addition, some specific or extended areas began to receive attention. Typical keywords are abundance, resource, Africa, risk, predation, consequence and science. The most illustrative papers in this stage are Fairhead et al. ( 2012 )’s discussion on green grabbing and Milcu et al. ( 2013 )’s review on cultural ecosystem services. Other representative papers in this period focused on the evaluation methods of ecosystem service value and the role of cultural ecosystem service in the evaluation of ecosystem service value. Most of the larger clusters in the survey erupted at this stage, including #0 cultural ecosystem services, #1 large carnivore, #3 whale shark, #4 ecosystem services. Some related clusters also belong to this stage, such as #7 neoliberal conservation, #8 responsible behavior, #9 tourism development, #13 mangrove forest, #15 volunteer tourism, #17 circular economy and #18 telecoupling framework.

Cluster #0 cultural ecosystem services are the largest cluster in ecotourism research field, containing 157 cited references from 2006 to 2019, with the mean year being 2012. It commenced to have the citation burst in 2009, with high cited continuing until 2019. Cultural ecosystem services are an essential component of ecosystem services, including spiritual, entertainment and cultural benefits. Thus, in Fig. 8 , the overlap with #4 ecosystem services can obviously be seen. In Cluster #0, many highly cited references have discussed the trade-offs between natural and cultural ecosystem services in ecosystem services (Nelson et al., 2009 ; Raudsepp-Hearne et al., 2010 ) and the important role of cultural ecosystem services in the evaluation of ecosystem services value (Burkhard et al., 2012 ; Chan, Guerry, et al., 2012 ; Chan, Satterfield, et al., 2012 ; Fisher et al., 2009 ; Groot et al., 2010 ). As non-market value, how to evaluate and quantify cultural ecosystem services is also an important issue (Hernández-Morcillo et al., 2012 ; Milcu et al., 2013 ; Plieninger et al., 2013 ). Besides, the exploration of the relationship among biodiversity, human beings and ecosystem services is also the focus of this cluster research (Bennett et al., 2015 ; Cardinale et al., 2012 ; Díaz et al., 2015 ; Mace et al., 2012 ). The citing articles of #0 indicate the continued exploration of the connotation of cultural ecosystem services and their value evaluation methods (Dickinson & Hobbs, 2017 ). It is noteworthy that some articles have introduced spatial geographic models (Havinga et al., 2020 ; Hirons et al., 2016 ) and social media methods (Calcagni et al., 2019 ) as novel methods to examine cultural ecosystem services. In addition, the link and overlap between #0 cultural ecosystem service and #17 circular economy cannot be overlooked.

Ecosystem services relate to all the benefits that humans receive from ecosystems, including supply services, regulatory services, cultural services and support services. Research on cultural ecosystem services is based on the research of ecosystem services. It can be viewed in Fig. 9 that the research and citation burst in #4 was all slightly earlier than #0. Cluster #4 includes 118 references from 2005 to 2019, with an average year of 2011. In its research and development, how to integrate ecosystem services into the market and the payment scheme to protect the natural environment is a significant research topic (Gómez-Baggethun et al., 2010 ). In Cluster #4, the most influential literature provides an overview of the payment of ecosystem services (PES) from theory to practice by Engel et al. ( 2008 ). Many highly cited references have discussed PES (Kosoy & Corbera, 2010 ; Muradian et al., 2010 ), including the effectiveness of evaluation (Naeem et al., 2015 ), social equity matters (Pascual et al., 2014 ), the suitability and challenge (Muradian et al., 2013 ), and how to contribute to saving nature (Redford & Adams, 2009 ). The cluster also includes studies on impact assessment of protected areas (Oldekop et al., 2016 ), protected areas and poverty (Brockington & Wilkie, 2015 ; Ferraro & Hanauer, 2014 ), public perceptions (Bennett, 2016 ; Bennett & Dearden, 2014 ) and forest ecosystem services (Hansen et al., 2013 ). The foremost citing articles confirm the dominant theme of ecosystem services, especially the in-depth study and discussion of PES (Muniz & Cruz, 2015 ). In addition, #4 is highly correlated with #7 neoliberal protection, and Fairhead et al. ( 2012 ), a representative article of this stage, belongs to this cluster.

As the second largest cluster, Cluster #1 contains 131 references from 2008 to 2019, with the median year of 2014. As Fig S2 a) shows, the highly cited literature has mainly studied the status and protection of large carnivores (Mace, 2014 ; Ripple et al., 2014 ), including the situation of reduction (Craigie et al., 2010 ), downgrade (Estes et al., 2011 ) and even extinction (Dirzo et al., 2014 ; Pimm et al., 2014 ), and the reasons for such results, such as tourist visits (Balmford et al., 2015 ; Geffroy et al., 2015 ) and the increase in population at the edge of the protected areas (Wittemyer et al., 2008 ). The conservation effects of protected areas on wildlife biodiversity (Watson et al., 2014 ) and the implications of tourist preference heterogeneity for conservation and management (Minin et al., 2013 ) have also received attention. It is worth noting that the high citation rate of a paper using R to estimate the linear mixed-effects model (Bates et al., 2015 ) and the use of R in this cluster. The relationship between biodiversity and ecotourism is highlighted by the representative citing articles in research frontier of this cluster (Chung et al., 2018 ).

Cluster #3 refers to marine predator, and as shown in Fig. 8 , which has a strong correlation with #1. A total of 125 references were cited from 2002 to 2018, with an average year of 2011. References with high citation in #3 mainly studied the extinction and protection of marine life such as sharks (Dulvy et al., 2014 ), as well as the economic value and ecological impact of shark ecotourism (Clua et al., 2010 ; Gallagher & Hammerschlag, 2011 ; Gallagher et al., 2015 ). The paper published by Gallagher et al. ( 2015 ) is both the highly cited reference and main citing article, mainly focusing on the impact of shark ecotourism. It is also noteworthy that #6 protected area, #13 mangrove forest and #29 Mediterranean areas are highly correlated with these two clusters (Fig. 8 ).

Moreover, some clusters are not highly correlated with other clusters, but cannot be neglected at this stage of research. Cluster #8 responsible behavior includes 107 citations with the average year 2013, and mainly studied environmentally responsible behaviors in ecotourism (Chiu et al., 2014 ). Cluster #9 tourism development contains 97 cited references with mean year of 2015, focusing on the impact of such factors as residents’ perception on tourism development (Sharpley, 2014 ). Cluster #15 volunteer tourism consists of 52 citations, with an average year of 2011, which mainly considers the role of volunteer tourism in tourism development and sustainable tourism (Wearing & McGehee, 2013 ). Cluster #18 telecoupling framework has 26 cited references with the mean year being 2015, and the application of the new integrated framework of telecoupling Footnote 1 in ecotourism can be seen (Liu et al., 2015 ).

At this stage, it can be seen that the research field of ecotourism begins to develop in the direction of diversification, including the value evaluation and related research of ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services, as well as the exploration of wild animals and plants, marine animals and plants and biodiversity. Neoliberal conservation, tourists’ responsible behavior, tourism development, volunteer tourism and circular economy are all explored. Some new research methods have also brought fresh air to this field, such as the introduction of spatial geographic models and social media methods, the discussion of economic value evaluation methods, the widespread use of R and the exploration of telecoupling framework. Therefore, from this stage, research in the field of ecotourism has entered the second stage of scientific discipline development (Shneider, 2009 ), featured by the use and evolution of research tools that can be used to investigate potential phenomena.

4.6.3 Phase III: Sustainable development research stage (2016 to present)

This stage of research continues to explore a series of topics of the preceding phase and further extends the research field on this basis. The keywords at this stage are politics, marine protected area and valuation. Some other keywords are still very active today, such as experience, challenge, sustainable development, willingness to pay, perspective, strategy, quality and satisfaction. The representative article is about sustainable development published by D'Amato et al. ( 2017 ), as shown in Fig. 8 belonging to #17 circular economy. The emerging clusters in this period are #11 ecological footprint, #14 social media and #16 COVID-19 pandemic. Cluster #11 contains 70 cited references from 2013 to 2020 with the mean year 2017. This clustering study mainly used the ecological footprint as an environmental indicator and socioeconomic indicators such as tourism to investigate the hypothesis of environmental Kuznets curve (Ozturk et al., 2016 ; Ulucak & Bilgili, 2018 ). Cluster #14 includes 52 cited references, with an average year of 2016. It can be seen that the introduction of social media data has added new color to research in the field of ecotourism, such as using social media data to quantify landscape value (Zanten et al., 2016 ) and to understand tourists’ preferences for the experience of protected areas (Hausmann et al., 2018 ), as well as from a spatial perspective using social media geo-tagged photos as indicators for evaluating cultural ecosystem services (Richards & Friess, 2015 ). As the latest and most concerned topic, cluster #16 contains 48 cited references, with mean year of 2018. This cluster mainly cites research on over-tourism (Seraphin et al., 2018 ) and sustainable tourism (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2018 ) and explores the impact of pandemics such as COVID-19 on global tourism (Gössling et al., 2021 ).

These emerging clusters at this phase bring fresh thinking to the research of ecotourism. First of all, the analysis of ecological footprint provides a tool for measuring the degree of sustainability and helps to monitor the effectiveness of sustainable programs (Kharrazi et al., 2014 ). Research and exploration of ecological footprint in ecotourism expresses the idea of sustainable development and puts forward reasonable planning and suggestions by comparing the demand of ecological footprint with the carrying capacity of natural ecosystem. Secondly, the use of social media data brings a new perspective of data acquisition to ecotourism research. Such large-scale data acquisition can make up for the limitations of sample size and data sampling bias faced by survey data users and provide a new way to understand and explore tourist behavior and market (Li et al., 2018 ). Finally, the sudden impact of COVID-19 in 2020 and its long-term sustainability has dealt a huge blow to the tourism industry. COVID-19 has highlighted the great need and value of tourism, while fundamentally changing the way destinations, business and visitors plan, manage and experience tourism (CREST, 2020 ). However, the stagnation of tourism caused by the pandemic is not enough to meet the challenges posed by the environment and the climate crisis. Therefore, how to sustain the development of tourism in this context to meet the challenges of the environment and climate change remains an important issue in the coming period of time. These emerging clusters are pushing the boundaries of ecotourism research and the exploration of sustainable development in terms of research methods, data collection and emerging topics.

Despite the fact that the research topics in this stage are richer and more diversified, the core goal of research is still committed to the sustainable development of ecotourism. The introduction of new technologies and the productive results have led to a much-improved understanding of research issues. All this commemorates the entrance of research into the third stage of the development of scientific disciplines (Shneider, 2009 ). In addition to continuing the current research topics, the future development of the field of ecotourism will continue to focus on the goal of sustainable development and will be more diversified and interdisciplinary.

5 Conclusion

This paper uses scientometrics to make a comprehensive visual domain analysis of ecotourism. The aim is to take advantage of this method to conduct an in-depth systematic review of research and development in the field of ecotourism. We have enriched the process of systematic reviews of knowledge domains with features from the latest CiteSpace software. Compared with previous studies, this study not only updated the database, but also extended the dataset with citation expansion, so as to more comprehensively identify the rapidly developing research field. The research not only identifies the main clusters and their advance in ecotourism research based on high impact citations and research frontiers formed by citations, but also presents readers with new insights through intuitive visual images. Through this study, readers can swiftly understand the progress of ecotourism, and on the basis of this study, they can use this method to conduct in-depth analysis of the field they are interested in.

Our research shows that ecotourism has developed rapidly in recent years, with the number of published articles increasing year by year, and this trend has become more pronounced after 2018. The research field of ecotourism spans many disciplines and is a comprehensive interdisciplinary subject. Ecotourism also attracts the attention of numerous developed and developing countries and institutions. The USA, China, Australia and South Africa are in a relatively leading position in the research and development of ecotourism. Foam tree map and pie chart of major topics, and the landscape view of keywords provide the hotspot issues of the research field. The development trend of ecotourism is preliminarily understood by detecting the citation bursts of the keywords and published articles. Co-citation analysis generates the main clusters of ecotourism research, and the timeline visualization of these clusters provides a clearer view for understanding the development dynamics of the research field. Building on all the above results, the research and development of ecotourism can be roughly divided into three stages: human disturbance, ecosystem services and sustainable development. Through the study of keywords, representative literature and main clusters in each stage, the development characteristics and context of each stage are clarified. From the current research results, we can catch sight that the application of methods and software in ecotourism research and the development of cross-field. Supported by the Shneider’s four-stage theory of scientific discipline (Shneider, 2009 ), it can be thought that ecotourism is in the third stage. Research tools and methods have become more potent and convenient, and research perspectives have become more diverse.

Based on the overall situation, research hotspots and development tendency of ecotourism research, it can be seen that the sustainable development of ecotourism is the core issue of current ecotourism research and also an important goal for future development. In the context of the current pandemic, the tourism industry is in crisis, but crisis often breeds innovation, and we must take time to reconsider the way forward. As we look forward to the future of tourism, we must adopt the rigor and dedication required to adapt to the pandemic, adhering to the principles of sustainable development while emphasizing economic reliability, environmental suitability and cultural acceptance. Post-COVID, the competitive landscape of travel and tourism will change profoundly, with preventive and effective risk management, adaptation and resilience, and decarbonization laying the foundation for future competitiveness and relevance (CREST, 2020 ).

In addition, as can be seen from the research and development of ecotourism, the exploration of sustainable development increasingly needs to absorb research methods from diverse fields to guide the formulation of policy. First of all, how to evaluate and quantify ecotourism reasonably and scientifically is an essential problem to be solved in the development of ecotourism. Some scholars choose contingent valuation method (CVM) and choice experiment (CE) in environmental economics to evaluate the economic value of ecotourism, especially non-market value. In addition, the introduction of spatial econometrics and the use of geographic information system (GIS) provide spatial scale analysis methods and results presentation for the sustainable development of ecotourism. The use of social media data implies the application of big data technology in the field of ecotourism, where machine learning methods such as artificial neural networks (ANN) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) are increasingly being applied (Talebi et al., 2021 ). The measurement of ecological footprint and the use of telecoupling framework provide a reliable way to measure sustainable development and the interaction between multiple systems. These approaches all have expanded the methodological boundaries of ecotourism research. It is worth noting that R, as an open source and powerful software, is favored by scholars in the field of ecotourism. This programming language for statistical computation is now widely used in statistical analysis, data mining, data processing and mapping of ecotourism research.

The scientometrics method used in this study is mainly guided by the citation model in the literature retrieval dataset. The range of data retrieval exercises restraint by the source of retrieval and the query method utilized. While current methods can meet the requirements, iterative query optimization can also serve to advance in the quality of the data. To achieve higher data accuracy, the concept tree function in the new version of CiteSpace can also serve to clarify the research content of each clustering (Chen, 2017 ). In addition, the structural variation analysis in the new edition is also an interesting study, which can show the citation footprints of typical high-yielding authors and judge the influence of the author on the variability of network structure through the analysis of the citation footprints (Chen, 2017 ).

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Web of Science.

Telecoupling, an integrated concept proposed by Liu et al. ( 2013 ), encompasses both socioeconomic and environmental interactions among coupled human and natural systems over distances. Liu et al. ( 2013 ) also constructed an integrated framework for telecoupling research, which is used to comprehensively study and explain multiple human-nature coupling systems at multiple spatial–temporal scales to promote the sustainable development of global society, economy and environment, and has been applied to ecotourism, land change science, species invasion, payments for ecosystem services programs, conservation, food trade, forest products, energy and virtual water, etc. (Liu et al., 2015 ).

Liu, J., Hull, V., Batistella, M., DeFries, R., Dietz, T., Fu, F.,... Zhu, C. (2013). Framing Sustainability in a Telecoupled World. Ecology and Society , 18 (2), 26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05873-180226

Abad-Segura, E., Cortés-García, F. J., & Belmonte-Ureña, L. J. (2019). The sustainable approach to corporate social responsibility: A global analysis and future trends. Sustainability, 11 (19), 5382. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195382

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad, F., Draz, M. U., Su, L., Ozturk, I., & Rauf, A. (2018). Tourism and environmental pollution: Evidence from the one belt one road (OBOR) provinces of Western China. Sustainability, 10 (10), 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103520

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ardoin, N. M., Wheaton, M., Bowers, A. W., Hunt, C. A., & Durham, W. H. (2015). Nature-based tourism’s impact on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior: A review and analysis of the literature and potential future research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23 (6), 838–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1024258

Balmford, A., Green, J. M. H., Anderson, M., Beresford, J., Huang, C., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., & Manica, A. (2015). Walk on the wild side: Estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biology, 13 (2), e1002074. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002074

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67 (1), 132904.

Bennett, N. J. (2016). Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology, 30 (3), 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12681

Bennett, E. M., Cramer, W., Begossi, A., Cundill, G., Díaz, S., Egoh, B. N., Geijzendorffer, I. R., Krug, C. B., Lavorel, S., Lazos, E., Lebel, L., Martín-López, B., Meyfroidt, P., Mooney, H. A., Nel, J. L., Pascual, U., Payet, K., Harguindeguy, N. P., Peterson, G. D., … White, G. W. (2015). Linking biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being: Three challenges for designing research for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14 , 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.03.007

Bennett, N. J., & Dearden, P. (2014). Why local people do not support conservation: Community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Marine Policy, 44 , 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.017

Brockington, D., & Wilkie, D. (2015). Protected areas and poverty. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 370 (1681), 20140271. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0271

Burkhard, B., Kroll, F., Nedkov, S., & Müller, F. (2012). Mapping ecosystem service supply, demand and budgets. Ecological Indicators, 21 , 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.06.019

Calcagni, F., Maia, A. T. A., Connolly, J. J. T., & Langemeyer, J. (2019). Digital co-construction of relational values: Understanding the role of social media for sustainability. Sustainability Science, 14 , 1309–1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00672-1

Cardinale, B. J., Emmett Duffy, J., Gonzalez, A., Hooper, D. U., Perrings, C., Venail, P., Narwani, A., Mace, G. M., Tilman, D., Wardle, D. A., Kinzig, A. P., Daily, G. C., Loreau, M., Grace, J. B., Larigauderie, A., Srivastava, D. S., & Naeem, S. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486 , 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148

Ceballos-Lascuráin, H. C. (1996). Tourism, ecotourism, and protected areas: The state of nature-based tourism around the world and guidelines for its development. World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, 4th, Caracas.

Chan, K. M. A., Guerry, A. D., Balvanera, P., Klain, Sarah, Satterfield, T., Basurto, X., Bostrom, A., Chuenpagdee, R., Gould, R., Halpern, B. S., Hannahs, N., Levine, J., Norton, B., Ruckelshaus, M., Russell, R., Tam, J., & Woodside, U. (2012). Where are cultural and social in ecosystem services? A framework for constructive engagement. BioScience, 62 (8), 744–756.

Google Scholar

Chan, K. M. A., Satterfield, T., & Goldstein, J. (2012b). Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecological Economics, 74 , 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.011

Chen, C. (2011). Predictive effects of structural variation on citation counts. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63 (3), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21694

Chen, C. (2017). Science mapping: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Data and Information Science, 2 (2), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/jdis-2017-0006

Chen, C., Dubin, R., & Kim, M. C. (2014a). Emerging trends and new developments in regenerative medicine a scientometric update (2000–2014). Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 14 (9), 1295–1317. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2014.920813

Chen, C., Dubin, R., & Kim, M. C. (2014b). Orphan drugs and rare diseases: A scientometric review (2000–2014). Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 2 (7), 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1517/21678707.2014.920251

Chen, C., Hu, Z., Liu, S., & Tseng, H. (2012). Emerging trends in regenerative medicine a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 12 (5), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Chen, C., & Leydesdorff, L. (2014). Patterns of connections and movements in dual-map overlays: A new method of publication portfolio analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science, 65 (2), 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22968

Chiu, Y.-T.H., Lee, W.-I., & Chen, T.-H. (2014). Environmentally responsible behavior in ecotourism: Antecedents and implications. Tourism Management, 40 , 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.013

Chung, M. G., Dietz, T., & Liu, J. (2018). Global relationships between biodiversity and nature-based tourism in protected areas. Ecosystem Services, 34 , 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.09.004

Clua, E., Buray, N., Legendre, P., Mourier, J., & Planes, S. (2010). Behavioural response of sicklefin lemon sharks Negaprion acutidens to underwater feeding for ecotourism purposes. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 414 , 257–266. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08746

Coria, J., & Calfucura, E. (2012). Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Ecological Economics, 73 , 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.10.024

Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., Kubiszewski, I., Stephen Farber, R., & Turner, K. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 26 , 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002

Craigie, I. D., Baillie, J. E. M., Balmford, A., Carbone, C., Collen, B., Greena, R. E., & Hutton, J. M. (2010). Large mammal population declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biological Conservation, 143 (9), 2221–2228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.06.007

CREST. (2019). The Case for Responsible Travel: Trends & statistics 2019 . https://www.responsibletravel.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/213/2021/03/trends-and-statistics-2019.pdf

CREST. (2020). The Case for Responsible Travel: Trends & statistics 2020 . https://www.responsibletravel.org/docs/trendsStats2020.pdf

D’Amato, D., Droste, N., Allen, B., Kettunen, M., Lähtinen, K., Korhonen, J., Leskinen, P., Matthies, B. D., & Toppinen, A. (2017). Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. Journal of Cleaner Production, 168 , 716–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.053

Daniel, T. C., Muhar, A., Arnberger, A., Aznar, O., Boyd, J. W., Chan, K. M. A., Costanza, R., Elmqvist, T., Flint, C. G., Gobster, P. H., Gret-Regamey, A., Lave, R., Muhar, S., Penker, M., Ribe, R. G., Schauppenlehner, T., Sikor, T., Soloviy, I., Spierenburg, M., … von der Dunk, A. (2012). Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. PNAS, 109 (23), 8812–8819. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114773109

Díaz, S., Demissew, S., Carabias, J., Joly, C., Lonsdale, Mark, Ash, N., Larigauderie, A., Adhikari, J. R., Arico, S., Báldi, A., Bartuska, A., Baste, I. A., Bilgin, A., Brondizio, E., Chan, K. M. A., Figueroa, V. E., Duraiappah, A., Fischer, M., Hill, R., … Zlatanova, D. (2015). The IPBES conceptual framework-connecting nature and people. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14 , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002

Dickinson, D. C., & Hobbs, R. J. (2017). Cultural ecosystem services: Characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban green space research. Ecosystem Services, 25 , 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.04.014

Dirzo, R., Young, H. S., Galetti, M., Ceballos, G., Isaac, N. J. B., & Collen, B. (2014). Defaunation in the anthropocene. Science, 345 (6159), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251817

Dulvy, N. K., Fowler, S. L., Musick, J. A., Cavanagh, R. D., Kyne, P. M., Harrison, L. R., Carlson, J. K., Davidson, L. N., Fordham, S. V., Francis, M. P., Pollock, C. M., Simpfendorfer, C. A., Burgess, G. H., Carpenter, K. E., Compagno, L. J., Ebert, D. A., Gibson, C., Heupel, M. R., Livingstone, S. R., … White, W. T. (2014). Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. Life, 3 , e00590. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.00590.001

Engel, S., Pagiola, S., & Wunder, S. (2008). Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecological Economics, 65 (4), 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.03.011

Estes, J. A., Terborgh, J., Brashares, J. S., Power, M. E., Berger, J., Bond, W. J., Carpenter, S. R., Essington, T. E., Holt, R. D., Jackson, J. B. C., Marquis, R. J., Oksanen, L., Oksanen, T., Paine, R. T., Pikitch, E. K., Ripple, W. J., Sandin, S. A., Scheffer, M., Schoener, T. W., … Wardle, D. A. (2011). Trophic downgrading of planet earth. Science, 333 (6064), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1205106

Fairhead, J., Leach, M., & Scoones, I. (2012). Green Grabbing: A new appropriation of nature? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39 (2), 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671770

Ferraro, P. J., & Hanauer, M. M. (2014). Quantifying causal mechanisms to determine how protected areas affect poverty through changes in ecosystem services and infrastructure. PNAS, 111 (11), 4332–4337. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1307712111

Fisher, B., Turner, R. K., & Morling, P. (2009). Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecological Economics, 68 (3), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.014

Gallagher, A. J., & Hammerschlag, N. (2011). Global shark currency: The distribution, frequency, and economic value of shark ecotourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 14 (8), 797–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.585227

Gallagher, A. J., Vianna, G. M. S., Papastamatiou, Y. P., Macdonald, C., Guttridgeg, T. L., & Hammerschlag, N. (2015). Biological effects, conservation potential, and research priorities of shark diving tourism. Biological Conservation, 184 , 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.02.007

Garfield, E. (1955). Citation indexes for science: A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. Science, 122 (3159), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.122.3159.108

Geffroy, B., Samia, D. S. M., Bessa, E., & Blumstein, D. T. (2015). How nature-based tourism might increase prey vulnerability to predators. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30 (12), 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.010

Gómez-Baggethun, E., de Groot, R., Lomas, P. L., & Montes, C. (2010). The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: From early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecological Economics, 69 (6), 1209–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.007

Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

de Groot, R. S., Alkemade, R., Braat, L., Hein, L., & Willemen, L. (2010). Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecological Complexity, 7 (3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecocom.2009.10.006

Hansen, M. C., Potapov, P. V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S. A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S. V., Goetz, S. J., Loveland, T. R., Kommareddy, A., Egorov, A., Chini, L., Justice, C. O., & Townshend, J. R. G. (2013). High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science, 342 (6160), 850–853. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

Hausmann, A., Toivonen, T., Slotow, R., Tenkanen, H., Moilanen, A., Heikinheimo, V., & Minin, E. D. (2018). Social media data can be used to understand tourists’ preferences for nature-based experiences in protected areas. Conservation Letters, 11 (1), e12343. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12343

Havinga, I., Bogaart, P. W., Hein, L., & Tuia, D. (2020). Defining and spatially modelling cultural ecosystem services using crowdsourced data. Ecosystem Services, 43 , 101091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101091

Hernández-Morcillo, M., Plieninger, T., & Bieling, C. (2012). An empirical review of cultural ecosystem service indicators. Ecological Indicators, 29 , 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.01.013

Higgins, B. R. (1996). The Global structure of the nature tourism industry: Ecotourists, tour operators, and local businesses. Journal of Travel Research, 35 (2), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759603500203

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25 , 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017

Hirons, M., Comberti, C., & Dunford, R. (2016). Valuing cultural ecosystem services. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41 , 545–574. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085831

Kharrazi, A., Kraines, S., Hoang, L., & Yarime, M. (2014). Advancing quantification methods of sustainability: A critical examination emergy, exergy, ecological footprint, and ecological information-based approaches [Review]. Ecological Indicators, 37 , 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.10.003

Köndgen, S., Kühl, H., N’Goran, P. K., Walsh, P. D., Schenk, S., Ernst, N., Biek, R., Formenty, P., Mätz-Rensing, K., Schweiger, B., Junglen, S., Ellerbrok, H., Nitsche, A., Thomas Briese, W., Lipkin, I., Pauli, G., Boesch, C., & Leendertz, F. H. (2008). Pandemic human viruses cause decline of endangered great apes. Current Biology, 18 (4), 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.012

Kosoy, N., & Corbera, E. (2010). Payments for ecosystem services as commodity fetishism. Ecological Economics, 69 (6), 1228–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.002

Krüger, O. (2005). The role of ecotourism in conservation: Panacea or Pandora’s box? Biodiversity & Conservation, 14 , 579–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-3917-4

Li, J., Xu, L., Tang, L., Wang, S., & Li, L. (2018). Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tourism Management, 68 , 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.009

Liu, J., Hull, V., Batistella, M., DeFries, R., Dietz, T., Fu, F., & Zhu, C. (2013). Framing sustainability in a telecoupled world. Ecology and Society, 18 (2), 26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05873-180226

Liu, J., Hull, V., Junyan Luo, W., Yang, W. L., Viña, A., Vogt, C., Zhenci, Xu., Yang, H., Zhang, J., An, Li., Chen, X., Li, S., Ouyang, Z., Weihua, X., & Zhang, H. (2015). Multiple telecouplings and their complex interrelationships. Ecology and Society, 20 (3), 44. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07868-200344

Mace, G. M. (2014). Whose conservation? Science, 345 (6204), 1558–1560. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254704

Mace, G. M., Norris, K., & Fitter, A. H. (2012). Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 27 (1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.08.006

McClung, M. R., Seddon, P. J., Massaro, M., & Setiawan, A. N. (2004). Nature-based tourism impacts on yellow-eyed penguins Megadyptes antipodes: Does unregulated visitor access affect fledging weight and juvenile survival? Biological Conservation, 119 (2), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2003.11.012

MCT. (2021). Statistical Bulletin on Culture and Tourism Development 2020 . Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-07/05/content_5622568.htm

Milcu, A. I., Hanspach, J., Abson, D., & Fischer, J. (2013). Cultural ecosystem services: A literature review and prospects for future research. Ecology and Society, 18 (3), 44. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05790-180344

Minin, E. D., Fraser, I., Slotow, R., & MacMillan, D. C. (2013). Understanding heterogeneous preference of tourists for big game species: Implications for conservation and management. Animal Conservation, 16 (3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2012.00595.x

Muniz, R., & Cruz, M. J. (2015). Making nature valuable, not profitable: Are payments for ecosystem services suitable for degrowth? Sustainability, 7 (8), 10895–10921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810895

Muradian, R., Arsel, M., Pellegrini, L., Adaman, F., Aguilar, B., Agarwal, B., Corbera, E., Ezzine de Blas, D., Farley, J., Froger, G., Garcia-Frapolli, E., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gowdy, J., Kosoy, N., Le Coq, J. F., Leroy, P., May, P., Méral, P., Mibielli, P., … Urama, K. (2013). Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conservation Letters, 6 (4), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00309.x

Muradian, R., Corbera, E., Pascual, U., Kosoy, N., & May, P. H. (2010). Reconciling theory and practice: An alternative conceptual framework for understanding payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics, 69 (6), 1202–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.11.006

Naeem, S., Ingram, J. C., Varga, A., Agardy, T., Barten, P., Bennett, G., Bloomgarden, E., Bremer, L. L., Burkill, P., Cattau, M., Ching, C., Colby, M., Cook, D. C., Costanza, R., DeClerck, F., Freund, C., Gartner, T., Goldman-Benner, R., Gunderson, J., … Wunder, S. (2015). Get the science right when paying for nature’s services. Science, 347 (6227), 1206–1207. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1403

Nelson, E., Mendoza, G., Regetz, J., Polasky, S., Tallis, H., Cameron, D., Chan, K. M. A., Daily, G. C., Goldstein, J., Kareiva, P. M., Lonsdorf, E., Naidoo, R., Ricketts, T. H., & Shaw, M. (2009). Modeling multiple ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, commodity production, and tradeoffs at landscape scales. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7 (1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1890/080023

Niñerola, A., Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V., & Hernández-Lara, A.-B. (2019). Tourism research on sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 11 (5), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051377

Oladeji, S. O., Awolala, D. O., & Alabi, O. I. (2021). Evaluation of sustainable ecotourism practices in Oke-Idanre Hills, Ondo-State, Nigeria [Article; Early Access]. Environment Development and Sustainability . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01550-6

Oldekop, J. A., Holmes, G., Harris, W. E., & Evans, K. L. (2016). A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conservation Biology, 30 (1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12568

Orams, M. B. (1995). Towards a more desirable form of ecotourism. Tourism Management, 16 (1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(94)00001-Q

Ozturk, I., Al-Mulali, U., & Saboori, B. (2016). Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: The role of tourism and ecological footprint. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23 , 1916–1928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-5447-x

Pascual, U., Phelps, J., Garmendia, E., Brown, K., Corbera, E., Martin, A., Gomez-Baggethun, E., & Muradian, R. (2014). Social equity matters in payments for ecosystem services. BioScience, 64 (11), 1027–1036. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu146

Pimm, S. L., Jenkins, C. N., Abell, R., Brooks, T. M., Gittleman, J. L., Joppa, L. N., Raven, P. H., Roberts, C. M., & Sexton, J. O. (2014). The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science, 344 (6187), 1246752. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246752

Plieninger, T., Dijks, S., Oteros-Rozas, E., & Bieling, C. (2013). Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy, 33 , 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.12.013

Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Peterson, G. D., & Bennett, E. M. (2010). Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. PNAS, 107 (11), 5242–5247. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0907284107

Redford, K. H., & Adams, W. M. (2009). Payment for ecosystem services and the challenge of saving nature. Conservation Biology, 23 (4), 785–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01271.x

Richards, D. R., & Friess, D. A. (2015). A rapid indicator of cultural ecosystem service usage at a fine spatial scale: Content analysis of social media photographs. Ecological Indicators, 53 , 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.01.034

Ripple, W. J., Estes, J. A., Beschta, R. L., Wilmers, C. C., Ritchie, E. G., Hebblewhite, M., Berger, J., Elmhagen, B., Letnic, M., Nelson, M. P., Schmitz, O. J., Smith, D. W., Wallach, A. D., & Wirsing, A. J. (2014). Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science, 343 (6167), 1241484. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241484

Ross, S., & Wall, G. (1999). Ecotourism: Towards congruence between theory and practice. Tourism Management, 20 (1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00098-3

Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9 , 374–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.01.011

Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42 , 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

Shasha, Z. T., Geng, Y., Sun, H.-P., Musakwa, W., & Sun, L. (2020). Past, current, and future perspectives on eco-tourism: A bibliometric review between 2001 and 2018. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27 , 23514–23528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08584-9

Shneider, A. M. (2009). Four stages of a scientific discipline; four types of scientist. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 34 (5), 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.02.002

Sirakaya, E., Sasidharan, V., & Sönmez, S. (1999). Redefining ecotourism: The need for a supply-side view. Journal of Travel Research, 38 (2), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800210

Snyman, S. (2017). The role of private sector ecotourism in local socio-economic development in southern Africa. Journal of Ecotourism, 16 (3), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1226318

Talebi, M., Majnounian, B., Makhdoum, M., Abdi, E., & Omid, M. (2021). Predicting areas with ecotourism capability using artificial neural networks and linear discriminant analysis (case study: Arasbaran Protected Area, Iran). Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23 , 8272–8287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00964-y

Ulucak, R., & Bilgili, F. (2018). A reinvestigation of EKC model by ecological footprint measurement for high, middle and low income countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 188 , 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.191

Valdivieso, J. C., Eagles, P. F. J., & Gil, J. C. (2015). Efficient management capacity evaluation of tourism in protected areas. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58 (9), 1544–1561. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.937479

Watson, J. E. M., Dudley, N., Segan, D. B., & Hockings, M. (2014). The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature, 515 , 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13947

Wearing, S., & McGehee, N. G. (2013). Volunteer tourism: A review. Tourism Management, 38 , 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.002

Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2007). Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tourism Management, 28 (5), 1168–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.004

West, P., Igoe, J., & Brockington, D. (2006). Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35 , 251–277.

Whitelaw, P. A., King, B. E. M., & Tolkach, D. (2014). Protected areas, conservation and tourism-financing the sustainable dream. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22 (4), 584–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.873445

Wight, P. (1993). Ecotourism: Ethics or eco-sell. Journal of Travel Research, 31 (3), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759303100301

Wittemyer, G., Elsen, P., Bean, W. T., Burton, A. C. O., & Brashares, J. S. (2008). Accelerated human population growth at protected area edges. Science, 321 (5885), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158900