The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Voyager’s Nonstop Around-the-World Adventure

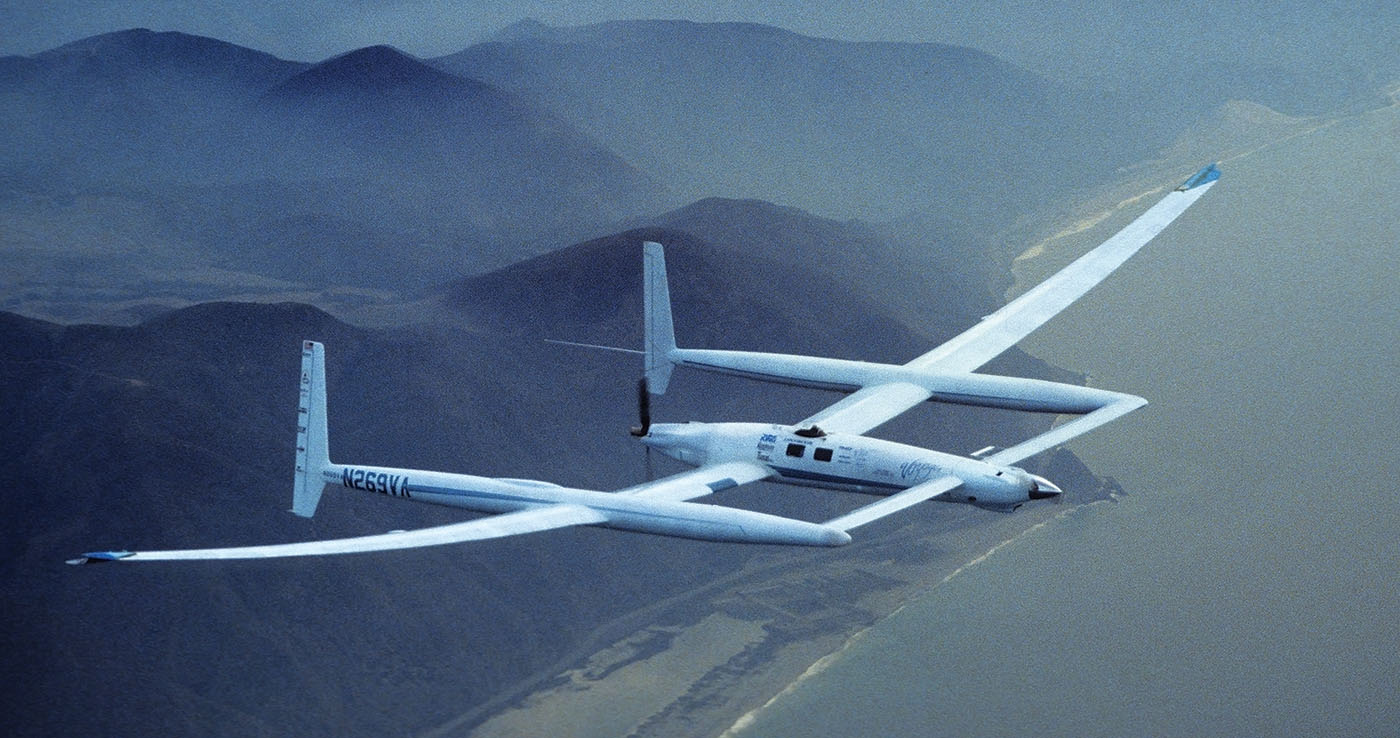

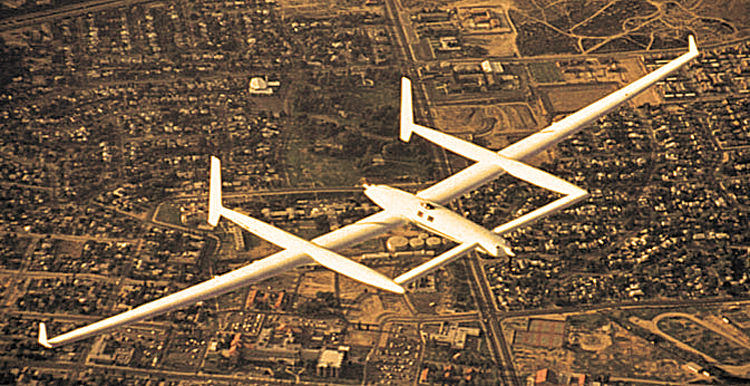

When Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager landed at California’s Edwards Air Force Base in the Rutan Voyager on December 23, 1986, they completed a historic flight that tested the limits of aircraft design and human endurance. The pair had left Edwards on December 14, having spent nine days and three minutes in the air during their nonstop, unrefueled flight around the world—the first of its kind. Along the way they nearly came to grief several times, as they grappled with exhaustion, mechanical problems, severe weather and even political considerations.

Dick’s brother Burt had first sketched Voyager’s design on a paper napkin at a Mojave, Calif., restaurant in 1981. Such an airplane—essentially a flying fuel tank—had been thought impossible.

The challenges Burt Rutan faced were daunting. He had to balance the necessary fuel capacity with the need for increased lift to overcome the fuel weight and higher induced drag. That required additional wing area, which in turn increased drag, compelling Rutan to use a high-aspect-ratio wing—long span and narrow chord—and enormously complicating the structural design.

The wing he needed could not be built without the aid of carbon composites, which boasted a strength-to-weight ratio seven times greater than that of steel. At the time Voyager was the largest composite aircraft ever to fly.

Construction of Voyager in the Rutan hangar at Mojave took two years of day and night work by a team of dedicated volunteers. Over the next three years, the airplane made 67 test flights, revealing serious operational issues. During a three-day flight, Dick and Jeana found the interior noise level generated by the tandem-mounted, push-pull engines almost unendurable, threatening permanent hearing loss, so the team added active-noise-suppression headsets. On another flight the electric propeller pitch-control motor on the front engine shorted out. Before it could be shut down, the engine shook off its mounts and the propeller departed. The only thing that saved Voyager and its crew was a flexible strap holding the engine to the fuselage.

Heading to Oshkosh, Wisc., in 1984 for the Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in, Voyager encountered a rainstorm that reduced lift from its wide canard to the point where the airplane kept losing altitude no matter what Dick tried. “I had a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach,” he said, “as the airplane was coming down, and I couldn’t stop it.” Voyager emerged from the storm and regained lift just in time to avoid the terrain ahead. To fix the problem, team members installed tiny vortex generators on the canard that smoothed the airflow. Solving these and other issues occupied the next two years.

Preparations for the around-the-world flight involved numerous additional tasks, such as securing the many overflight clearances required, studying regional weather patterns and setting up global communications relays. The support team included recognized experts in such fields as meteorology, communications, instrumentation and control engineering.

Burt Rutan’s design was precisely tailored to the mission, but Dick and Jeana learned that with a high fuel load Voyager was barely flyable. The long-span, unusually flexible wings went from a pronounced droop at the start of takeoff to a hawk-like upward curve as they generated lift. The transition from takeoff to climb had to be flown with knife-edge accuracy to avoid dangerous wing oscillations. Designer and pilots knew Voyager was fundamentally unsafe. “This thing flies like a turkey vulture,” Dick said.

In order to save weight, the airplane’s fuel system—16 individual tanks and two pumps (one per side) transferring fuel into a single central tank feeding both the forward and rear engines—was not equipped with automatic valves or individual fuel pumps. Hence keeping Voyager within center-of-gravity limits was a continuous burden, mostly on Jeana, who kept a meticulous fuel transfer record.

To reach its maximum range, Voyager had to maintain a best lift-over-drag attitude, with a specific constant angle of attack for each speed. Burt’s carefully planned vertical profile specified the speed for each successive stage as fuel weight diminished. On a flight lasting over a week, that task required an autopilot.

On the morning of December 14, Voyager was loaded with 7,011.5 pounds of fuel, 15 percent more than on its heaviest previous flight. The aircraft’s gross takeoff weight was 9,694.5 pounds, supported by an airframe that weighed just 939 pounds. The landing gear was designed to handle that one-time load on takeoff, which would be made from Edwards’ 15,000-foot runway.

Team members pumped air into the gear struts to provide a bit more clearance for Voyager’s drooping wings, then added more fuel to the forward tanks. Those actions slightly twisted the wings forward and down, inadvertently setting the stage for a potential disaster. In anticipation of the extra weight, the tires were inflated to a pressure of 3,200 psi, almost twice the rated maximum.

The halfway point on the runway, at 7,500 feet, was the agreed abort point in the event Voyager hadn’t reached the required 83 knots to begin rotation. As Voyager lumbered down the runway just after 8 a.m., it was still four knots short when it reached that point. Over the radio, Burt yelled, “Dick, pull the stick back, dammit!” But knowing he didn’t have adequate speed for liftoff and refusing to abort, Dick left the throttles wide open, staking their lives on that crucial decision. “The airplane was accelerating smoothly,” he later said, “and the end of the runway was still a mile and a half ahead.”

Dick was unaware that the extra fuel weight had caused the wingtips to scrape the runway, and that the outboard wing sections were now generating negative lift. Voyager was at the 11,000-foot point when it reached 83 knots, but still Dick didn’t rotate; a premature attempt at liftoff might fracture the wings between the inner sections generating lift and the outer sections still under downward pressure from negative lift. He held the airplane on the runway until Jeana called “87 knots,” and only then began to ease back on the stick as the assembled crowd screamed “Pull up, pull up!” Voyager finally lifted off 14,200 feet down the runway, a mere 800 feet from the end. “One hundred knots,” Jeana called out, as Voyager reached 100 feet altitude. “We needed the extra lift from ground effect—within our 110-foot wingspan—which I used to boost our airspeed to the climb target,” Dick explained.

The scraped wingtips were damaged to the point where they were soon shed, leaving tattered foam and loose wires exposed at the ends. How close was the wingtip damage to the fuel tanks? Could a leak have been started? Could the exposed wires cause a short during a storm? Nobody knew, so Voyager simply flew westward. Early in the flight, the overburdened airplane burned fuel so fast that a pound of fuel yielded less than two miles of flight distance.

One hour into the flight, Voyager was 7,400 feet above the Pacific. The aircraft’s inherent instability would continue to pose a threat even after it was safe to turn on the autopilot. Dick had to be at the controls in case significant oscillations began that the autopilot couldn’t immediately correct. Although Jeana had a few hundred hours of flying experience, she hadn’t yet learned how to prevent those dangerous oscillations, which could break up the airplane while it was so fuel-heavy. Jeana looked out the cockpit window and exclaimed, “See the wings! They’re almost flapping.”

For the next three days, Dick stayed at the controls. His lack of adequate sleep set the stage for new dangers ahead. Jeana’s neck grew stiff as she lay on her side watching the instruments while Dick catnapped. “He needed the rest,” she said, “so I had to monitor what the airplane was doing, and reach around him to make any adjustments.”

After passing Hawaii, they entered the Intertropical Convergence Zone, with high-altitude westerly winds and low-altitude easterly winds. Voyager stayed at 7,500 feet, along the five-degree north parallel, an area of frequent storm activity. As they approached Guam, the weather guru at Mission Control in Mojave, Len Snellman, warned the crew about a large typhoon just to the southeast. Voyager was able to pick up some tailwind from the typhoon’s counterclockwise circulation by skirting it on the north side. That tailwind would provide an important gain in fuel savings.

From about mid-Pacific all the way to Africa, the crew and Mission Control became increasingly concerned about the rate of fuel consumption indicated by Jeana’s log. For reasons unknown, possibly leaks from the wingtip damage, there might not be enough fuel to complete the mission. They began to actively consider possible emergency landing sites. Dick remembered “a sinking feeling in my stomach; I wanted to cry. We were looking at failure.”

Overflying Sri Lanka, with its 10,000-foot runway, Dick felt so tired he could hardly resist the temptation to land. But his mother’s words, “If you can dream it, you can do it,” ran through his mind, and he knew Jeana wanted to fly on, so they did. Later, Jeana discovered a reverse flow of fuel from the feeder tank back to the selected fuel tank. Dick guessed the amount was insufficient to drain the feeder tank and stop the engine, but there was no way to know for sure.

Voyager approached the African coast well south of Somalia (for which they had no overflight clearance) on a moonless dark night. Jeana was at the controls while Dick slept in the rear compartment. Fuel was still a concern, so she ran the rear engine lean. Their radar revealed a storm ahead, just south of their course. Jeana awakened Dick, and as he got into the cockpit they were at the edge of the storm. They were through the turbulence in a few minutes, about to start across a continent with few airfields and a sky full of storm clouds.

Voyager was over western Kenya, on its planned course, heading for Lake Victoria and cumulus buildups, with mountainous terrain beyond. They were five hours late for an inflight rendezvous with Doug Shane, who had flown by airline to Kenya and rented a Beech Baron in order to observe Voyager up close to see if the wingtip damage had caused fuel leaks requiring a mission abort. Voyager already was climbing to avoid Mt. Kenya and other peaks ahead over 17,000 feet. Shane was nearing the Baron’s ceiling, with only a few minutes to approach Voyager and inspect for fuel leaks in the early morning light. “No ugly blue streaks,” he called. Relieved to know Voyager was not leaking fuel, they climbed to 20,500 feet to clear the mountains ahead.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Dehydration and equally insidious hypoxia threatened their survival. Neither Dick nor Jeana had managed to drink enough fluid to replenish their losses flying so high. Nor were they breathing 100-percent oxygen, required for that altitude, because earlier Dick had dialed it back to conserve their supply. Dick could see Jeana’s reflection in the radar screen; she was curled up like a cat, sleeping soundly—too soundly. Dick called, “Jeana, wake up! Wake up!” while reaching back to shake her. “What, what?” she finally responded, then quickly fell back asleep. Soon after, Dick said, “Jeana, look at this,” shaking her awake again. “Look at the instrument panel! It’s bulging out; it may explode!” “It’s o.k., Dick,” she reassured him, “you’re just tired. I’ll take care of it.” As Voyager descended to 14,000 feet, Dick’s hallucinations stopped. Jeana squeezed past him and took the controls. Her head was pounding with a migraine headache. “My stomach was churning, I started vomiting into my little throw-up bag,” she said. “I just kept flying; Dick was in worse shape.”

Night overtook them as Jeana let Dick sleep longer than planned because of his extreme fatigue. After he was back at the controls, Dick realized they were very late for the course change to avoid Mt. Cameroon. “Why didn’t you wake me?” he yelled. “There’s a mountain out there and we almost ran into it.” “So, why didn’t you remind me of it?” Jeana replied.

Clearing Africa, the two fliers experienced an overwhelming sense of relief. Looking at Dick, “I saw big tears rolling down his cheeks,” Jeana remembered. “I reached over his shoulder and gave him a hug.”

On crossing the South Atlantic, things took a turn for the worse. As Voyager approached the coast of Brazil, Mission Control lacked weather satellite data and could not provide adequate guidance for the location. With bad weather ahead, Dick was forced to thread his way through an area of dense thunderstorms, in the dark. Their radar showed storm cells close ahead, at right, left and center. Turbulence tossed Voyager like a cork, and a cell swallowed the aircraft. One wing was forced high and the other low as the aircraft quickly went into a 90-degree bank. Voyager was about to go inverted. “Well babe, this is it, I think we’ve bought the farm this time,” Dick said. “Look at the attitude indicator. We ain’t gonna make it.” Jeana stayed quiet.

The cell ejected Voyager, but it was still far over on its side—an attitude out of a bad dream. Dick knew the only way to recover was to unload the G-force on the wings and regain airspeed, and only after that gently roll back level while ensuring airspeed didn’t build too rapidly to recover. “We never banked Voyager over 20 degrees before,” Dick noted. “I’d rather go back across Africa than tangle with one of these storms again.” Mission Control was soon getting better weather satellite coverage and helping the crew find the safest way through the remaining storm cells.

After the adrenaline wore off, Dick desperately needed rest. Jeana took over, dodging cumulus clouds for the next three hours. The airplane had by this time consumed most of its fuel and was lighter, so fuel economy increased, allowing them to shut down the forward engine. Over the Caribbean, north of Venezuela, Voyager’s fuel economy climbed to five miles per pound—30 miles per gallon. Nevertheless, the uncertain fuel situation prompted the crew to run the engine very lean. Mission Control warned of cumulus buildups over Panama, and suggested overflying Costa Rica instead.

Later, heading northwest off the Nicaraguan coast, Voyager aimed for home as dawn broke on the flight’s eighth day. Headwinds slowed its ground speed to 65 knots. Dick flew on as Jeana managed the fuel flow. Suddenly the right side fuel pump went into overspeed and failed. Dick had anticipated such a possibility and arranged a bypass of the feeder tank through the engine’s mechanical pump. Now he made the switch and fuel again flowed. But the sight tube had to be checked constantly, to detect the first bubbles of air in the line.

When the engine coughed a few times, changing tanks brought it back to life. Dick switched to a tank in the canard that he thought had plenty of fuel, but it didn’t and the engine stopped. Voyager had been running at 8,000 feet on the rear engine, to conserve fuel. Now they heard only the wind. Dick lowered the nose, hoping higher airspeed would restart the windmilling engine, to no avail. Without engine power, the mechanical pump couldn’t operate.

Voyager was now down to 5,000 feet. Mike Melvill in Mission Control suggested starting the front engine, but Dick feared that would block the rear engine, with its still windmilling prop, from restarting. They needed both engines to get home. The situation was critical; Voyager was rapidly losing altitude.

Dick and Jeana followed the cold-engine-start checklist. “Elbow flying now,” Dick said, needing both hands for the restart sequence. “Just take it easy, Dick,” Jeana said. “You’re doing fine.” Voyager, heavy on the right side due to the fuel imbalance, continued down. Dick used the avionics backup battery to avoid an instrument-killing current surge from the main battery. Still, the front engine would not start. At 3,500 feet Dick leveled out, allowing the fuel to flow, and the engine finally coughed to life.

Now they had to finish replacing the right-side pump to relieve the imbalance from Voyager’s fuel-heavy right wing. Dick installed the pump while Jeana got the many valves turned correctly. An anxious half-hour passed before enough fuel to get them home flowed slowly into the feeder tank.

Finally Voyager left the ocean behind, and at first light was over California’s San Gabriel Mountains. Chase planes flown by Melvill and Shane joined up while Dick and Jeana kept their focus on precision flying. Voyager appeared over Edwards at 7:32 a.m. Dick did a flyby at 400 feet and a few more with the chase planes. He wanted to do one more flyby, at just 50 feet, but Jeana chimed in, “Dick, time to land, we’re running low on fuel.” Thousands of people were waiting as they carefully landed, taxied to the parking area and shut down the engines that had taken them around the world. When the leftover fuel was drained, little more than 108 pounds (18 gallons) of the original 7,000-plus pounds remained.

Voyager’s world flight remains one of the greatest achievements in aviation history. For their feat, the Rutans, Yeager and the Voyager team were awarded the 1986 Collier Trophy.

Pierre Hartman is a former light-sport pilot who lives in Tehachapi, Calif., 20 miles from Mojave. Further reading: Voyager , by Jeana Yeager and Dick Rutan, with Phil Patton; and Voyager: The World Flight , by Jack Norris.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of Aviation History.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

This Frenchman Tried to Best the Wright Brothers on Their Home Turf

The Wrights won.

The Scandal that Led to Harry S. Truman Becoming President and Marilyn Monroe Getting Married

Did Curtiss-Wright deliberately sell defective engines to the U.S. Army during WWII?

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Dick Rutan, co-pilot of historic round-the-world flight, dies at 85

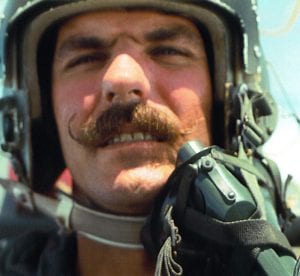

FILE - Co-pilots Dick Rutan, right, and Jeana Yeager, no relationship to test pilot Chuck Yeager, pose for a photo after a test flight over the Mojave Desert, Dec. 19, 1985. Rutan, a decorated Vietnam War pilot, who along with copilot Yeager completed one of the greatest milestones in aviation history: the first round-the-world flight with no stops or refueling, died late Friday, May 3, 2024. He was 85. (AP Photo/Doug Pizac, File)

FILE - Balloonist Dick Rutan talks about the short flight of the Global Hilton balloon at a news conference in Albuquerque, N.M., Friday, Jan. 9, 1998. Rutan, a decorated Vietnam War pilot, who along with copilot Jeana Yeager completed one of the greatest milestones in aviation history: the first round-the-world flight with no stops or refueling, died late Friday, May 3, 2024. He was 85. (AP Photo/Jake Schoellkopf, File)

FILE - Dick Rutan works on disassembling the wings of his Cessna on Buttermere Road in Victorville, Calif., where he made an emergency landing, early Tuesday, Dec. 18, 2007. Rutan, a decorated Vietnam War pilot, who along with copilot Jeana Yeager completed one of the greatest milestones in aviation history: the first round-the-world flight with no stops or refueling, died late Friday, May 3, 2024. He was 85. (Reneh Agha/Daily Press via AP, File)

FILE - Sir Richard Branson, left, shakes hands with record breaking aviator Dick Rutan after Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo space tourism rocket was unveiled, Friday, Feb. 19, 2016, in Mojave, Calif. Rutan, a decorated Vietnam War pilot, who along with copilot Jeana Yeager completed one of the greatest milestones in aviation history: the first round-the-world flight with no stops or refueling, died late Friday, May 3, 2024. He was 85. (AP Photo/Mark J. Terrill, File)

- Copy Link copied

MEREDITH, N.H. (AP) — Burt Rutan was alarmed to see the plane he had designed was so loaded with fuel that the wing tips started dragging along the ground as it taxied down the runway. He grabbed the radio to warn the pilot, his older brother Dick Rutan. But Dick never heard the message.

Nine days and three minutes later, Dick, along with copilot Jeana Yeager, completed one of the greatest milestones in aviation history: the first round-the-world flight with no stops or refueling.

A decorated Vietnam War pilot, Dick Rutan died Friday evening at a hospital in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, with Burt and other loved ones by his side. He was 85. His friend Bill Whittle said he died on his own terms when he decided against enduring a second night on oxygen after suffering a severe lung infection.

“He played an airplane like someone plays a grand piano,” said Burt Rutan of his brother, who was often described as has having a velvet arm because of his smooth flying style.

Burt Rutan said he had always loved designing airplanes and became fascinated with the idea of a craft that could go clear around the world. His brother was equally passionate about flying. The project took six years.

There was plenty to worry Burt during testing of the light graphite plane, Voyager. There were mechanical failures, any one of which would have been disastrous over a distant ocean. When fully laden, the plane couldn’t handle turbulence. And then there was the question of how the pilots could endure such a long flight on so little sleep. But Burt said his brother had an optimism about him that made them all believe.

“Dick never doubted whether my design would actually make it around, with still some gas in the tank,” Burt Rutan said.

Voyager left from Edwards Air Force Base in California just after 8 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1986. Rutan said with all that fuel, the wings had only inches of clearance. Dick couldn’t see when they started dragging on the runway. But at the moment Burt called on the radio, copilot Yeager gave a speed report, drowning out the message.

“And then, the velvet arm really came in,” Burt Rutan said. “And he very slowly brought the stick back and the wings bent way up, some 30 feet at the wingtips, and it lifted off very smoothly.”

They arrived back to a hero’s welcome as thousands gathered to witness the landing. Both Rutan brothers and Yeager were each awarded a Presidential Citizens Medal by President Ronald Reagan, who described how a local official in Thailand at first “refused to believe some cockamamie story” about a plane flying around the world on a single tank of gas.

“We had the freedom to pursue a dream, and that’s important,” Dick Rutan said at the ceremony. “And we should never forget, and those that guard our freedoms, that we should hang on to them very tenaciously and be very careful about some do-gooder that thinks that our safety is more important than our freedom. Because freedom is awful difficult to obtain, and it’s even more difficult to regain it once it’s lost.”

Richard Glenn Rutan was born in Loma Linda, California. He joined the U.S. Air Force as a teenager and flew more than 300 combat missions during the Vietnam War.

He was part of an elite group that would loiter over enemy anti-aircraft positions for hours at a time. The missions had the call sign “Misty,” and Dick was known as “Misty Four-Zero.” Among the many awards Dick received were the Silver Star and the Purple Heart.

He survived having to eject twice from planes, once when his F-100 Super Sabre was hit by enemy fire over Vietnam, and a second time when he was stationed in England and the same type of plane had a mechanical failure. He retired from the Air Force with the rank of lieutenant colonel and went on to work as a test pilot.

Burt Rutan said his brother was always having adventures, like the time he got stranded at the North Pole for a couple of days when the Russian biplane he was in landed and then sank through the ice.

Dick Rutan set another record in 2005 when he flew about 10 miles (16 kilometers) in a rocket-powered plane launched from the ground in Mojave, California. It was also the first time U.S. mail had been carried by such a plane.

Greg Morris, the president of Scaled Composites, a company founded by Burt Rutan, said he first met Dick was when he was about seven and over the years always found him generous and welcoming.

“Bigger than life, in every sense of the word,” Morris said, listing off Rutan’s legacy in the Vietnam War, testing planes and on the Voyager flight. “Any one of those contributions would make a legend in aviation. All of them together, in one person, is just inconceivable.”

Whittle said Rutan had been courageous in his final hours at the hospital — sharp as a tack, calm and joking with them about what might come next after death.

“He’s the greatest pilot that’s ever lived,” Whittle said.

Dick Rutan is survived by his wife of 25 years Kris Rutan; daughters Holly Hogan and Jill Hoffman; and grandchildren Jack, Sean, Noelle and Haley.

Simple Flying

Rutan voyager: the first plane to circumnavigate the world without refueling or stopping.

The Rutan Voygaer holds the record for the longest flight in the world even today.

The Rutan Voyager Model 76 was the first plane to successfully circumnavigate the globe without making any stops at all. The thin airframe took five years to develop and set off on its journey on December 14th, 1986, landing a full nine days later on December 23rd. Here's a look at this record-breaking aircraft.

From a napkin to the skies

The Voyager was built by Burt Rutan, Dick Rutan, and Jeana Yaeger. Burt reportedly first sketched the design of the plane on a paper napkin in 1981 and started work not long after in Mojave, California under the banner of its aerospace company. Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger were the pilots of the historic flight.

To sustain flight over 216 hours, keeping the weight of the aircraft at a minimum was essential. To do this, Rutan used a combination of composite materials like kevlar and fiberglass to bring the airframe weight to just 426kgs. The engines alone weighed more than this at 594kgs, with two propellers running in the middle section on either end.

At first glance, the Voyager Model 76 is unlike any commercial aircraft design , having no clear tail or fuselage, instead seeing one long wing cutting across three fuselage sections and a parallel connector for the trio. Rutan's design was built to maximize lift to drag ratio, which would be crucial to keeping the plane in the skies for days.

The design process took over five years until the plane was ready to take to the skies in June 1986 for the first time.

Testing to takeoff

Burt Rutan's design proved to be a successful one, with the two pilots using the Model 76 to break the record for the longest flight in the world in testing in July 1986 alone. However, the trio hoped to take the voyager on a journey like no other, circumnavigating the globe without any refueling or technical stops.

After over 60 test flights, the Rutan Voyager set off for its nonstop global flight on December 14th, 1986 from Edwards Air Force Base. However, things did not go too smoothly from the beginning, with the tips of the wings hitting the runway surface and eventually ripping off in the initial stages of the flight. However, the pilots opted to continue given the plane still met its technical range even without the tips.

The pair of pilots flew heroically, avoiding closed airspace, storms, and other weather events to ensure the plane's performance was not hampered significantly. With little space in the cockpit, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger were only able to switch over controls occasionally, with days passing at times.

Stay informed: Sign up for our daily and weekly aviation news digests.

After a fuel pump failure toward the end of the flight, the two pilots managed to complete the voyage successfully at 08:06 AM on 23rd December at Edwards AFB, with a recorded journey time of over 216 hours and circumnavigating the globe. 38 years later, this record remains in place, with no endurance flight even close to beating the Rutan Model 76 Voyager.

Transportation History

Finding the unexpected in the everyday.

No Stopping, No Refueling – A Record-Breaking Flight Around the World

December 14, 1986

The Rutan Model 76 Voyager, the first aircraft to circle around Earth without stopping or refueling, embarked on its historic flight at Edwards Air Force Base in California in the Mojave Desert. This westerly flight of 26,366 statute miles (42,432 kilometers) would end with great success nine days, three minutes, and 44 seconds later.

The Voyager was piloted by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager. Both of them, along with Rutan’s brother Burt, had come up with the idea of the Voyager while they were having lunch one day in 1981. They sketched out the initial design at that time on the back of a napkin. Over the next five years, the actual aircraft was built by a group of volunteers.

The Voyager’s innovative features for flight endurance included front and rear propellers powered by separate engines; the plan was for the rear engine to remain operational throughout the entire flight, while the front engine would provide that extra burst of energy for takeoff and the initial part of the journey. The start of the flight took place along a 15,000-foot (4,600-meter)-long runway at 8:01 a.m. on December 14, 1986. “The Voyager experimental aircraft, its crew undaunted despite damage to its wingtips on take-off, soared out over the Pacific on the last great adventure in aviation,” proclaimed one newspaper account the following day.

For more information on the Rutan Model 76 Voyager and its pioneering round-the-world flight, please check out https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rutan_Voyager .

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Create a website or blog at WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Site Navigation

Rutan voyager, object details, related content.

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Dick Rutan, co-pilot of around-the-world flight, dies at 85

- Oops! Something went wrong. Please try again later. More content below

Even as a young child growing up in the small Central Valley town of Dinuba, Dick Rutan knew that he wanted to be a pilot. Whenever he heard an airplane, he would gaze up and it seemed the sky was beckoning him.

“I wanted to get up there in it,” Rutan recalled. “Those contrails of the big jets overwhelmed me. It was my destiny to fly.”

He started lessons at 15, soloed on his 16th birthday and had a flight instructor’s rating by the time he graduated high school. He would go on to fly more than 300 combat missions in Vietnam, but those were the least of his achievements.

Read more: Dick Rutan, 4 Other Fliers Stuck at North Pole as Plane Sinks; None Hurt

In 1986, the decorated airman co-piloted the experimental aircraft Voyager around the world in nine days, taking off from and landing at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert without stopping or refueling — one of aviation's greatest milestones.

"It's a grand adventure," a wobbly Rutan said, after the nationally televised landing watched by President Reagan.

Rutan died Friday at a hospital in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, after suffering from a lung infection. His brother Burt Rutan , an aerospace engineer who designed the spindly Voyager, was at his bedside. Rutan was 85.

After 20 years in the Air Force, Dick Rutan joined his younger brother's Mojave aircraft company as a production manager and chief test pilot, but resigned to found Voyager Aircraft Co. with a single goal in mind: completing the record-breaking flight.

Read more: THE RETURN OF THE VOYAGER : A Native Californian, Rutan Was Born to Fly

The round-the-world trip was the product of six years of planning, development and testing, supported by grassroots donations when Rutan and his co-pilot, Jeana Yeager, his girlfriend at the time, could not strike a deal for a corporate sponsorship. (Yeager is no relation to famed test pilot Chuck Yeager.)

The twin-engine Voyager was constructed out of a lightweight graphite-honeycomb composite. It had a small cabin and disproportionate wingspan of nearly 111 feet that enabled it to carry more than four times its weight in fuel — 1,500 gallons tipping the scales at nearly 9,000 pounds — making it uncomfortable to sleep in and ungainly to fly.

It took off from Edwards at 8:02 a.m. on Dec. 14, a Sunday, and barely got off the ground, as the tips of its fuel-laden wings scraped the runway. During the trip, Rutan and Yeager traded piloting duties as the other attempted to sleep. Along the way, they battled tropical storms and averted disaster when an engine cut out just 450 miles from home. They were able to restart it.

When they landed 24,986 miles later, thousands cheered, and both pilots were some 10 pounds lighter. They, along with Burt Rutan, would meet the president, who awarded each the Presidential Citizens Medal. The Voyager was chosen by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington for inclusion in its collection of historic aircraft.

“He played an airplane like someone plays a grand piano,” said Burt Rutan of his brother.

Dick Rutan achieved celebrity and was in demand on the speaker circuit but didn't gain the fortune he had expected after scrimping for years to get Voyager aloft. (His brother would go on to design SpaceShipOne, the first privately funded and crewed craft to enter space, launching an entirely new industry.)

In 1992, Rutan ran for Congress against Democratic Rep. George Brown Jr. in California's 42nd Congressional District in the Inland Empire. A surprise winner of the Republican primary, Rutan was beaten in the general election.

The pilot never lost his taste for pushing aviation's limits. In 1998, when he was 59, he and a co-pilot attempted to become the first balloonists to fly nonstop around the world. But the duo had to bail out and parachute to safety when the craft sprang a helium leak shortly after takeoff in New Mexico.

Rutan shrugged it off, noting he had had to bail out of planes twice before, including once in Vietnam when his jet was shot out of the sky. (The global circumnavigation was achieved the next year by a pair of Swiss and British balloonists.)

Not one to turn down an adventure, he got stranded in the North Pole for several days two years later when the Russian biplane carrying him and four others landed and partially sank through the ice. He wasn't seeking a record but just wanted to check out the pole.

Rutan set another aviation record in 2005 when, in his 60s, he flew some 10 miles in a rocket-powered plane launched from the ground.

Greg Morris, president of Scaled Composites, a Mojave aerospace company founded by Burt Rutan, said when he was about 7 he met the aviation pioneer and over the years always found him generous and welcoming.

“Bigger than life, in every sense of the word,” Morris said, noting Rutan’s legacy with Voyager, as a test pilot and in the military, where he earned a Silver Star, five Distinguished Flying Crosses, 16 Air Medals and a Purple Heart. "Any one of those contributions would make a legend in aviation. All of them together, in one person, is just inconceivable.”

Born July 1, 1938, in Loma Linda, Rutan is survived by his wife of 25 years, Kris Rutan; daughters Holly Hogan and Jill Hoffman, from a previous marriage; and grandchildren Jack, Sean, Noelle and Haley.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times .

Recommended Stories

X is officially making likes (mostly) private for everyone.

In a new tweet, X's Engineering account has revealed that the social network is making likes private for everyone this week.

The U.S. cricket team is sparking hope with an unlikely lineup of 9-to-5ers: 'We've created history already'

The U.S. men's cricket team is winning the hearts of the America — and the world.

Paul Skenes stellar again in scoreless start, draws standing ovation on road from Cardinals fans

Skenes and Miles Mikolas were locked in a pitchers duel at Busch Stadium. The Pirates prevailed, 2-1.

Free Joey Chestnut: A petty corporate decision is depriving America of its beloved hot dog king

Nathan’s is really going to ban 16-time champion Joey Chestnut over a simple sponsorship conflict? That's just un-American.

Engadget Podcast: Recapping WWDC 2024 from Apple Park

In this bonus episode, Cherlynn and Devindra brave the California heat to discuss Apple Intelligence and how it's different than other AI solutions.

Toyota Chairman Akio Toyoda flipped a GR Yaris rally car during testing

Toyota Chairman Akio Toyoda flipped a GR Yaris rally car while testing and displayed the wrecked car at the opening of the Shimoyama R&D center.

Father's Day summer savings event at Dick's Sporting Goods

Save big on Father's Day gifts from Yeti, Blackstone, Nike, adidas, DSG, and more. This limited-time summer sale lasts until June 16.

Hello, Caleb Williams: NFL Network's live preseason schedule includes 3 Bears games

Rookie quarterbacks will be featured often on NFL Network.

Musk withdraws his breach of contract lawsuit against OpenAI

Musk’s suit, which was filed in February, had accused OpenAI co-founders Sam Altman and Greg Brockman of violating the company’s non-profit status and instead prioritizing profits over using AI to help humanity.

Summer cool: These fab, flowy dresses from Anthropologie are up to 70% off

There's nothing like a breezy dress on a hot day, and these are our top picks from Anthropologie's sale section.

A beginner's guide on how to play cricket ahead of the World Cup match between the U.S. and India

Here are the basic rules to cricket to understand before the United States' next match in the World Cup.

Glen Powell's 'Hit Man' is a hit for Netflix with No. 1 debut — why experts, insiders agree he's a bona fide movie star

It's the year of Glen Powell. After the success of "Hit Man," experts and industry insiders break down why the Texas actor's rise to fame is long overdue.

Euro 2024 betting: France is getting the most wagers, while the most money is on England

England hasn't won a major men's soccer tournament since 1966.

One big thing for every AFC team heading into the 2024 season

On today's episode, Jason Fitz and Frank Schwab unpack one big question for every AFC team heading into the 2024 NFL season.

Copa América power rankings: Can anybody top Argentina? Can the USMNT contend?

Here’s how the Copa América field stacks up with kickoff approaching.

'Must-have for outdoor adventures': This solar power bank is over 90% off

This solar-powered charging bank is the 'game changer' you need to keep your devices juiced up even when you're off the grid.

Amari Cooper holding out from Browns minicamp amid spike in WR salaries

Cooper presumably would like to cash in on the rising wide receiver market that's seen multiple contract records set this offseason.

Oilers' Leon Draisaitl to avoid discipline for hit that took Panthers' Aleksander Barkov out of Game 2

Barkov did not play the final 9:28 of Florida's Game 2 win over Edmonton.

Stock market today: S&P 500, Nasdaq notch fresh records with Apple as CPI, Fed decision loom

Investors braced for a Federal Reserve meeting that should signpost the path of interest rates, with a key inflation print also waiting in the wings.

Half of all drivers don't have much trust in their car insurance company

A new J.D. Power survey of U.S. car owners tackles the topic of customer satisfaction and trust when it comes to insurance companies.

- Enshrinement

- Members Area

- Terms and Conditions

- About Overview

- Our Mission & Vision

- Our Leadership and Staff

- The NAHF Documentary

- Plan A Visit

- HHEC Renovations

- 2023 Impact Report

- Learning Overview

- View Our Enshrinees

- For Educators

- For Students

- Membership Overview

- Individual Membership

- Corporate Membership

- Programs Overview

- Annual Crossfield Award

- Spirit of Flight Award

- The Armstrong Award

Around the world, non-stop!

25th anniversary of the most incredible flight ever..

This year marks the 25 th anniversary of the most incredible flight ever by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager. The Rutan Model 76 Voyager was the first aircraft to fly around the world without stopping or refueling. The aircraft was first imagined by Jeana, Dick, and his brother Burt Rutan as they were at lunch in 1981. The initial idea was first sketched out on the back of a napkin. The flight took off from Edwards Air Force Base’s 15,000 foot (4,600 m) runway in the Mojave Desert on December 14, 1986, and ended successfully 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds later, on December 23 with only a few gallons of fuel remaining. Burt Rutan has been enshrined into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1995, as well as his brother Dick Rutan in 2002.

For more information, you may want to visit these links:

- Dick Rutan: NAHF Enshrinee , Wikipedia

- Burt Rutan: NAHF Enshrinee , Wikipedia

- Jeana Yeager: Wikipedia

- Rutan Model 76 Voyager: Wikipedia

Contact NAHF

937-256-0944

[email protected]

1100 Spaatz Street Dayton, Ohio 45433

P.O. Box 31096 Dayton, Ohio 45437

Stay Up To Date

Please enter your name and email address below to sign up for our mailing list.

Copyright © 2024 NAHF. All rights reserved. | Web design by Jetpack

60th Annual Enshrinement Ceremony and Dinner, presented by Garmin

September 14, 2024 at the NMUSAF in Dayton, OH

Tickets Available Now!

Secure Your Spot

- Advertising

- PDF Edition

- Distribution

- Business Directory

- On This Date

- Photo Archive

- Space/Technology

- Digital Edition

- High Desert Hangar

- Special Issue

Remembering Dick Rutan, hero who flew Voyager around the world

LANCASTER, Calif. — One of the last times I saw experimental test pilot Dick Rutan was on a panel I emceed called “Going Downtown: The Air War in Vietnam.”

Aerotech News was a key sponsor of the Los Angeles County Air Show where Rutan shared the story of his last combat mission.

Rutan died May 3, 2024, age 85 in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. With his genius airplane designer brother, Burt, together, they make up the reason the tarmac of Mojave Air and Space Port is named “Rutan Field.”

Dick Rutan is remembered as the pilot who flew the airplane his brother designed, the flimsy looking but epically strong “Voyager” experimental aircraft around the world on a single tank of gas. Rutan flew with Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager) as co-pilot.

That was nearly 40 years ago. Voyager now is proudly displayed in the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum, another testament that Antelope Valley is the “Aerospace Valley and flight test capital of the world.”

The Rutan brothers won the Collier Award trophy for Voyager.

In the many episodes of Dick Rutan’s pilot story, his exploits as a combat pilot show who he was, and what he achieved. On his last mission in Vietnam, his aircraft was hit. His F-100 Super Sabre was on fire, and he nosed it toward the Gulf of Tonkin before ejecting.

“That was the day I joined the Gulf of Tonkin ‘Yacht Club,’” he said, floating in a survival raft until he retrieval by a search-and-rescue helicopter. Lifted by a cable hoist and deposited into the Air-Sea Rescue helicopter, Rutan was relieved, and thanked the air crew on board so they could hear above the rotor din.

“I knew I was going home — that I had made it,” he said.

Curling up on the chopper floor, he said “I wrapped myself in a blanket, and went to sleep.”

That was just another dot on the map of a hero’s journey. The man flew 325 missions in Vietnam. The unit he flew with, Misty FAC, lost more than a quarter of its pilots to enemy fire.

The mission was to fly low to spot enemy anti-aircraft batteries and fly close enough to “paint them” as targets for other aircraft called “Wild Weasels.” Misty FAC denoted “Forward Air Control.”

His combat flight record was valor defined. Rutan was awarded the Silver Star, four awards of Distinguished Flying Cross, with Valor device, 16 awards of the Air Medal for combat aerial operations, and, notably, the Purple Heart.

In his autobiography, Chuck Yeager wrote he once was tasked with telling younger Vietnam pilots that they had the best training, best planes, best chow, best liquor, and best girls. So, Vietnam’s air war was where they needed to steel themselves to fly low on course, and hit their targets. Rutan never needed that briefing.

His Air Force career began in 1959 shortly before John F. Kennedy was elected president. A young Rutan served as “radar intercept officer” and also as a flight navigator before he earned his silver Air Force pilot wings a half dozen years into service.

Once he turned fighter pilot, the man was a tiger with ammo strapped on. In Vietnam photos, he sports a non-regulation handlebar Wyatt Earp moustache straight out of “Tombstone.”

During the Vietnam flight panel, he mused aloud what he wanted to share with what was a packed tent of mostly awestruck admirers.

Rutan shared with the audience what he called “a little pseudo psychology” about combat. That mindset, he said, is “Kill, or be killed.” Destroy the enemy’s guns or be destroyed by them.

Adrenaline, Rutan said, is about running away from bears chasing you. Combat is about chasing the bear.

“The epitome of competition is one man against another,” he said. And that spirit is fueled by what Rutan called the “combat gland.”

“The combat gland has an addictive, euphoric effect,” Rutan said. “Every time you shoot, it’s kill or be killed. You want more, and you want more, and you want more.

“If you’ve lived your life without being shot at, you’re missing something,” he said. It is a physical component, particularly, he said, of the “testosterone-charged male.”

Few in that tent filled that description. They were mostly civilian dads and moms and kids, people who loved or worked aviation, people who loved history. Combat veterans, the guys with ball caps, nodded approvingly in their understanding of combat and its addictive quality.

Rutan was on stage with living history. Among the four other combat alphas who joined him was Col. Joe Kittinger, another legend.

At a reception the evening before the tent show, I saw Rutan greet the older man, Kittinger, like a long lost brother. He loved Joe Kittinger. They were two of a kind, Kittinger, portly, and Rutan, rangy. Brothers!

Kittinger had a couple of records. He set records as the first man to free fall from space. In August 1960, when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, Kittinger jumped from a balloon at the edge of space, falling from 103,000 feet above ground level to test pressure suits for the space program.

After four combat tours in Vietnam, Kittinger also fell from the sky when his F-4 Phantom was shot down. He was sent to the notorious “Hanoi Hilton” prison camp for a year before the POW releases started in 1972. He held record as the “oldest new guy” in camp.

Kittinger recalls “I had studied at every survival and escape school there was, and I was going to hit the ground and evade for a year, make my way back.”

Instead, his parachute plopped him in a field filled with rice, and with North Vietnamese farmers. “About 50 of them swarmed my butt.”

They stripped his boots and flight suit, and took his pistol. Wobbling on a wounded left leg, “in my skivvies Ö the first thing an 80-year-old lady waved a knife at my neck, and I jumped back. The next thing, a 14-year-old boy did the same thing.”

Kittinger, like other surviving POWs, survived that parachute landing only because North Vietnamese troops arrived, pushing him into a truck to the prison camp that inspired dread in American pilots.

“It’s just the worst ‘Hilton’ in the world,” Kittinger joked to the tent full of aviation history buffs. “There’s no air conditioning, no room service. The food sucks. Don’t ever stay there.”

Their banter showed these were men who came close to laughing at death, and did laugh about it afterward, in each other’s good company.

First time I met Rutan for an interview at Mojave Airport for Associated Press in 1986 during the buildup of excitement for the Voyager Flight, he made it obvious he did not care for press. He was only putting up with us to help sustain support for the project.

A few weeks later, I stepped out on the tarmac at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., to shake his hand when Voyager completed its globe-girdling flight. Surrounded by a throng of admirers he was even more dismissive. He asked me, half-jokingly, if I was trying to snag his wristwatch.

More than 15 years later, I interviewed him when he was named Grand Marshal of a “Welcome Home Vietnam Veterans” parade in Lancaster. I don’t think he remembered me, but he saw my miniature silver Army paratrooper wings on my coat lapel, and he asked when and where I served. Cold War Europe, I replied, at a place called the Fulda Gap where it was believed the Soviets would invade in World War III.

He warmed up instantly. “There were things about the Cold War that were scary as Vietnam,” he said. “When you fly with a nuke strapped under your cockpit, it gets your heart racing.

“Cold War veterans have always deserved more recognition in my book,” Rutan said. And I agreed.

Our veteran bond cemented a mutual respect. At the Los Angeles County Air Show, he remembered, and his greeting was warm as mine, and I have never forgotten how he closed that afternoon’s event.

Rutan recalled the words of the American warriors’ most beloved leaders, Adm. Jeremiah Denton, the most senior officer of POWs, who was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Stepping off the returning jetliner at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, Denton spoke for the men he led during their captivity.

Rutan recited Denton’s words, saying “Every time I say this, I choke up.”

Quoting Admiral Denton, he recited “I consider it an honor to have had the privilege to serve my country under difficult circumstances.”

Rutan reflected, “I think about the totality of what he said, and I think to myself, ‘Who are these people, such remarkable people?’”

One of those people was Rutan. The other, Kittinger. Both achieved remarkable things, and both considered it a privilege to serve their country wherever their service took them.

Editor’s note: Dennis Anderson is an Army paratrooper veteran who deployed with California National Guard to cover the Iraq war for local and national publications. He serves on the Los Angeles County Veterans Advisory Commission.

More Stories

Legend! Bud Anderson: A great...

‘FlyGirl’ a wonderful fearless inspiration...

Contract Briefs

Headlines — June 10

- Aerotech News: Antelope Valley

- Aerotech News: Edwards AFB

- High Desert Warrior: Ft. Irwin NTC

- Desert Lightning News: Nellis/Creech AFB

- Thunderbolt: Luke AFB

- Desert Lightning News: Davis-Monthan AFB

Aerotech News and Review , published every other Friday, serves the aerospace and defense industry of Southern California, Nevada and Arizona.

News and ad copy deadline is noon on the Tuesday prior to publication. The publisher assumes no responsibility for error in ads other than space used.

- Our Products

- Work With Us

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : December 23

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Voyager completes global flight

After nine days and four minutes in the sky, the experimental aircraft Voyager lands at Edwards Air Force Base in California, completing the first nonstop flight around the globe on one load of fuel. Piloted by Americans Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, Voyager was made mostly of plastic and stiffened paper and carried more than three times its weight in fuel when it took off from Edwards Air Force Base on December 14. By the time it returned, after flying 25,012 miles around the planet, it had just five gallons of fuel left in its remaining operational fuel tank.

Voyager was built by Burt Rutan of the Rutan Aircraft Company without government support and with minimal corporate sponsorship. Dick Rutan, Burt’s brother and a decorated Vietnam War pilot, joined the project early on, as did Dick’s friend Jeanna Yeager (no relation to aviator Chuck Yeager ). Voyager ‘s extremely light yet strong body was made of layers of carbon-fiber tape and paper impregnated with epoxy resin. Its wingspan was 111 feet, and it had its horizontal stabilizer wing on the plane’s nose rather than its rear–a trademark of many of Rutan’s aircraft designs. Essentially a flying fuel tank, every possible area was used for fuel storage and much modern aircraft technology was foregone in the effort to reduce weight.

When Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force at 8:02 a.m. PST on December 14, its wings were so heavy with fuel that their tips scraped along the ground and caused minor damage. The plane made it into the air, however, and headed west. On the second day, Voyager ran into severe turbulence caused by two tropical storms in the Pacific. Dick Rutan had been concerned about flying the aircraft at more than a 15-degree angle, but he soon found the plane could fly on its side at 90 degrees, which occurred when the wind tossed it back and forth.

Rutan and Yeager shared the controls, but Rutan, a more experienced pilot, did most of the flying owing to the long periods of turbulence encountered at various points in the journey. With weak stomachs, they ate only a fraction of the food brought along, and each lost about 10 pounds.

On December 23, when Voyager was flying north along the Baja California coast and just 450 miles short of its goal, the engine it was using went out, and the aircraft plunged from 8,500 to 5,000 feet before an alternate engine was started up.

Almost nine days to the minute after it lifted off, Voyager appeared over Edwards Air Force Base and circled as Yeager turned a primitive crank that lowered the landing gear. Then, to the cheers of 23,000 spectators, the plane landed safely with a few gallons of fuel to spare, completing the first nonstop circumnavigation of the earth by an aircraft that was not refueled in the air.

Voyager is on permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Also on This Day in History December | 23

The journal "science" publishes first report on nuclear winter, madam c.j. walker is born, chaminade shocks no. 1 virginia in one of greatest upsets in sports history, pittsburgh steelers' franco harris scores on "immaculate reception" iconic nfl play.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on December 23

“balloon boy” parents sentenced in colorado.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Japanese war criminals hanged in Tokyo

Construction of plymouth settlement begins, vincent van gogh chops off his ear, the execution of eddie slovik is authorized, chuck berry is arrested on mann act charges in st. louis, missouri, woody allen marries soon-yi previn, subway shooter bernhard goetz goes on the lam, crew of uss pueblo released by north korea, chemical contamination prompts evacuation of missouri town.

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

From point a to point a.

Twenty-five years ago, Burt Rutan’s Voyager became the first aircraft to make an around-the-world flight without refueling.

George C. Larson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Moments-Milestones-Voyager-FLASH.jpg)

A little after 8 a.m. on December 14, 1986, a spindly white airplane began a takeoff roll at Edwards Air Force Base in California. A crowd of onlookers was surprised to see that as it was rolling, its wingtips were touching the ground. This unexpected development must also have surprised the airplane’s designer, Burt Rutan, who had built the Voyager expressly for this flight (see “ Design by Rutan ,”). Eventually both wingtips fell off, but that had little effect on the outcome, as pilot Dick Rutan—Burt’s brother—and copilot Jeana Yeager went on to fly around the planet westbound and land nine days later—almost to the minute—on December 23, setting a record and becoming the first aircraft to make an around-the-world flight without refueling.

The flight was unquestionably a test of human endurance, but it also marked a milestone that only someone like Burt Rutan would spend time thinking about. As a designer of experimental and homebuilt airplanes, Rutan had been working for years with modern composite materials of increasing strength and decreasing weight. The design has been attributed to a collaboration of Burt, Dick, and Jeana, but what made the flight—and the airplane—feasible was that the composite materials used to build the aircraft allowed the designer to provide an enormous volume for fuel storage in an airframe light enough to fly with modest power.

The primary material in Voyager is a kind of sandwich: two layers of graphite fiber composite with paper honeycomb in between. Rutan knew that an airplane made of these materials would be light enough to carry the fuel needed to make the round-the-world trip nonstop. Voyager ’s airframe weighs only 939 pounds, but its 17 fuel tanks, located in two fat sponsons and the fuselage, carried 7,011 pounds of gasoline. Add the weight of its two engines and its two pilots and it took off at more than 9,700 pounds. What engineers call its “fuel fraction,” the fuel portion of its total weight, is an astonishingly large 72 percent. For comparison, a B-52 (another airplane with exceptional range that has flown around the world, but with inflight refueling) has a fuel fraction of about 64 percent.

Equally important for Voyager ’s success was its propulsion. Rutan designed the airplane with two engines, one mounted on the nose and the other on the aft fuselage. The rear engine was a Teledyne Continental IOL-200 rated at 110 horsepower. That’s the same size engine that has powered thousands of Cessna 150s and other light aircraft; this one was modified for Voyager to employ liquid cooling rather than air around its cylinders. In a technical paper describing the engine project (SAE 871042), Ron E. Wilkinson, the Continental engineer in charge, wrote that the engine’s unique parallel liquid cooling arrangement provided very favorable uniformity in temperatures, which, combined with a high-turbulence combustion chamber design, resulted in unusually high fuel efficiency. In the nose was an air-cooled O-240 engine, which delivered 130 horsepower for takeoff and climb. The nose engine spent most of the flight shut down with its propeller feathered so the blades were edgewise to the wind, reducing drag.

Burt Rutan is retired, Dick Rutan lectures and consults on experimental aircraft and engines, and Jeana Yeager went home to Texas, but 25 years ago, they and the team that supported the flight won the National Aeronautic Association’s Collier Trophy for the year’s greatest flying achievement in the United States.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

George C. Larson | READ MORE

George C. Larson served as editor of Air & Space from 1985 to 2005. He is currently an inactive pilot, but holds a commercial pilot's license, with instrument and multi-engine ratings. He is between airplanes at this time, but has owned or operated a Grumman American AA-5B Tiger and a Mooney 201. He has been writing about aviation since 1972, when he joined the staff of Flying Magazine.

To view items in this collection, use the Online Finding Aid

On December 23, 1986 the unique Voyager aircraft completed the first nonstop, non-refueled circumnavigation of the globe. Voyager's designer, Burt Rutan, its pilots for the nine-day historic flight, Richard "Dick" Rutan and Jeana Yeager, as well as crew chief Bruce Evans, were all to win the Collier Trophy for their accomplishment of one of aviation's last "firsts."

NASM.2000.0054

Riva, Peter

Peter Riva, Gift, 2000, 2000-0054, unknown

9.89 Cubic feet ((1 letter document box) (8 records center boxes) (2 shoeboxes) (1 flatbox))

National Air and Space Museum Archives

This collection consists of the records kept by project manager Peter Riva and includes legal files, general office files, audio tapes, videotapes, newspaper and magazine accounts of the flight and transcripts of the account that would become the book, Voyager by Jeana Yeager and Dick Rutan with Phil Patton, published by Knopf in 1987.

Material is subject to Smithsonian Terms of Use. Should you wish to use NASM material in any medium, please submit an Application for Permission to Reproduce NASM Material, available at Permissions Requests

See accession file.

Rutan Model 76 Voyager

Aeronautics -- Records

Endurance flights

Aeronautics -- Flights

Aeronautics -- Awards

Aeronautics

Collection descriptions

Archival materials

Transcripts

Business records

Legal documents

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Dick Rutan, Who Flew Around the World Without Refueling, Dies at 85

His nine-day voyage, in a plane designed by his brother that resembled a child’s glider but had wings longer than a Boeing 727’s, made aviation history.

By Trip Gabriel

Dick Rutan, who in 1986 commanded the first aircraft to make a nonstop flight around the world without refueling — an aviation milestone whose ingenuity and daring recalled the heroic do-it-yourself era of early flight — died on Friday in a hospital in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. He was 85.

His brother, Burt, who designed the ultralightweight plane that was flown in that nine-day voyage, said that Mr. Rutan had suffered from long Covid, which in recent weeks required 24-hour assisted breathing, and that he had decided to have his oxygen turned off after enduring a night of great pain.

“Before he made the decision to end it,” Burt Rutan said, “he was talkative.”

In the spirit of technology created by other California tinkerers, the design of the Rutan craft, the Voyager, was first sketched by Burt Rutan on a napkin at a Chinese restaurant in the desert town of Mojave in 1981.

The advent of a new material, composites of carbon fiber, made it possible for the first time to imagine an airplane light enough for a round-the-world flight on a single tank of gas, Burt Rutan told his brother and his brother’s companion at the time, Jeana Yeager.

The plane they built in a hangar in the desert was propeller-driven and resembled a child’s balsa wood glider, but with wings longer than those of a Boeing 727. It was essentially a collection of 17 fuel tanks in a sheath of carbon fiber cloth, epoxy and paper — a skin so fragile that it could be damaged by an elbow poke. Voyager was so heavy with fuel on takeoff that it took nearly three miles of runway to ascend from Edwards Air Force Base in Southern California on Dec. 14, 1986.

Mr. Rutan had flown combat missions for the Air Force in the Vietnam War. But, he said in a memoir he wrote with Ms. Yeager, his co-pilot on the flight, the home-built aircraft with its flexible wings was one plane that truly frightened him.

“I had never gotten used to the flailing wings,” he wrote in the joint memoir, “Voyager” (1987). “I would tell myself that the structures could take that motion, but I wasn’t ever really convinced. It was a gnawing, grinding fear, and it never went away.”

Adding to his anxiety was that his relationship with Ms. Yeager had run its course before the flight began — and that, in his view, she had not prepared enough to be his co-pilot.

“Tensions were developing between us long before we got off the ground,” Ms. Yeager wrote in their memoir. “I would have left if I could, but I had made a commitment.”

Putt-putting at low altitudes, taking catnaps to steal sleep, nearly slamming into a mountain in Africa and almost ditching in the Pacific Ocean, the Voyager and its crew limped home on fumes from empty fuel tanks two days before Christmas.

“The significance of their voyage can be compared to Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 Atlantic crossing,” Michael Collins , a former test pilot and astronaut, wrote in The New York Times in 1987. “Although Voyager was much more of a team effort than Lindbergh’s solo, success in each case resulted from the same combination of vision, luck, skill and guts.”

Stuart Witt, a former chief executive of the Mojave Air & Space Port, a hub for private spaceflight, said in an interview that the Voyager had demonstrated the potential of composites of carbon fibers and other high-tech materials in airplane frames, which were traditionally made of aluminum and steel. The Rutan brothers “disrupted an entire industry,” he said.

“They brought composite structures into the industry. Now look at what a 787 is made of, what an Airbus 350 is made of,” he added, referring to wide-body aircraft made by Boeing and Airbus.

Burt Rutan, an aeronautical engineer, said that other test pilots who flew the craft in trial runs cut their flying time short; the turbulence the plane experienced wore them out. “They’d end up coming back exhausted,” he said. “None of my other pilots would have been able to do it.”

He also said that Ms. Yeager had never learned to fly the plane alone, relying on autopilot while his brother caught up on sleep.

Ms. Yeager, who is not related to the famous test pilot Chuck Yeager, disputed the notion that she had a secondary role flying Voyager. “Actually, we were both co-pilots,” she said in an interview.

Speaking last year on the YouTube channel SocialFlight , Dick Rutan said that after the Voyager landed, Ms. Yeager “got out of the airplane and went back to Texas, and I’ve never heard from her again.”

He was, he added, speaking metaphorically; the pair later collaborated on their book, and on speaking tours.

“Some very special people came together in this project, and I remember them fondly,” Ms. Yeager added. “I’m sorry that we’re not all together again.”

On Voyager’s final night aloft, Burt Rutan flew up in a chase plane to greet his brother. “The totality of the thing finally hit all of us,” Dick Rutan recalled last year. “We’re literally crying, tears coming down our face. You couldn’t even speak, you were crying so hard.” Thousands of people came out to welcome Voyager home.

The plane is in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum , along with Lindbergh’s Spirt of St. Louis and the Wright brothers’ Flyer.

Richard Glenn Rutan was born on July 1, 1938, in Loma Linda, Calif., the eldest of the three children of Irene (Goforth) Rutan and George Rutan. His father was a farmer who enlisted in the Navy and after World War II, with the help of the G.I. Bill, became a dentist.

His first marriage ended in divorce. In 1999, he married Kristin Cremer, a kindergarten teacher. In addition to his brother, she survives him, as does a sister, Nell Rutan, a retired American Airlines flight attendant who, the family likes to say, has flown more miles than either brother. His survivors also include two daughters, Holly Hogan and Jill Hoffman, and four grandchildren.

“Somebody said when Dick was born, he didn’t have a birth certificate — he had a flight plan,” his brother said.

He earned a pilot’s license on his 16th birthday and enlisted in the Air Force at 19. As a Tactical Air Command fighter pilot, he flew 325 combat missions in Vietnam, according to the National Aviation Hall of Fame. Many of his missions were in a two-seat F-100 as part of a special squadron, nicknamed Misty, that flew fast and low to identify targets on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Mr. Rutan was awarded the Silver Star, the Purple Heart and five Distinguished Flying Crosses before retiring from the Air Force in 1978 as a lieutenant colonel. He then became a test pilot for his brother’s Rutan Aircraft Factory, which designed planes for amateur builders.

Following the epic Voyager flight, Mr. Rutan set his sights on other quests. In 1992, he ran unsuccessfully as a Republican for a congressional seat in San Bernardino County, Calif. He tried to circle the globe in a balloon in 1998, but that voyage ended above Texas after three hours.

In 2001, he became a test pilot for an experimental rocket-powered plane. He told The Los Angeles Times, “I’m pretty much a hero pilot, so they came and asked me to fly their airplane.” The reporter, Glenn Gaslin, wrote that there was no trace of irony in Mr. Rutan, not even when he hiked up the sleeve of his flight suit and rubbed the arm he used to control the plane.

“See this right here?” he said. “This is the velvet arm. It is without equal in the universe.”

Trip Gabriel is a national correspondent. He covered the past two presidential campaigns and has served as the Mid-Atlantic bureau chief and a national education reporter. He formerly edited the Styles sections. He joined The Times in 1994. More about Trip Gabriel

Dick Rutan, co-pilot of around-the-world flight, dies at 85

E ven as a young child growing up in the small Central Valley town of Dinuba, Dick Rutan knew that he wanted to be a pilot. Whenever he heard an airplane, he would gaze up and it seemed the sky was beckoning him.

“I wanted to get up there in it,” Rutan recalled. “Those contrails of the big jets overwhelmed me. It was my destiny to fly.”

He started lessons at 15, soloed on his 16th birthday and had a flight instructor’s rating by the time he graduated high school. He would go on to fly more than 300 combat missions in Vietnam, but those were the least of his achievements.

In 1986, the decorated airman co-piloted the experimental aircraft Voyager around the world in nine days, taking off from and landing at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert without stopping or refueling — one of aviation's greatest milestones.

"It's a grand adventure," a wobbly Rutan said, after the nationally televised landing watched by President Reagan.

Rutan died Friday at a hospital in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, after suffering from a lung infection, said his brother Burt Rutan, an aerospace engineer who designed the spindly Voyager and was at his bedside. Rutan was 85.

After 20 years in the Air Force, Dick Rutan joined his younger brother's Mojave aircraft company as a production manager and chief test pilot, but resigned to found Voyager Aircraft Co. with a single goal in mind: completing the record-breaking flight.

The round-the-world trip was the product of six years of planning, development and testing, supported by grassroots donations when Rutan and his co-pilot, Jeana Yeager, his girlfriend at the time, could not strike a deal for a corporate sponsorship. (Yeager is no relation to famed test pilot Chuck Yeager.)

The twin-engine Voyager was constructed out of a lightweight graphite-honeycomb composite. It had a small cabin and disproportionate wingspan of nearly 111 feet that enabled it to carry more than four times its weight in fuel — 1,500 gallons tipping the scales at nearly 9,000 pounds — making it uncomfortable to sleep in and ungainly to fly.

It took off from Edwards at 8:02 a.m. on Dec. 14, a Sunday, and barely got off the ground, as the tips of its fuel-laden wings scraped the runway. During the trip, Rutan and Yeager traded piloting duties as the other attempted to sleep. Along the way, they battled tropical storms and averted disaster when an engine cut out just 450 miles from home. They were able to restart it.

When they landed 24,986 miles later, thousands cheered, and both pilots were some 10 pounds lighter. They, along with Burt Rutan, would meet the president, who awarded each the Presidential Citizens Medal. The Voyager was chosen by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington for inclusion in its collection of historic aircraft.

“He played an airplane like someone plays a grand piano,” said Burt Rutan of his brother.

Dick Rutan achieved celebrity and was in demand on the speaker circuit but didn't gain the fortune he had expected after scrimping for years to get Voyager aloft. (His brother would go on to design SpaceShipOne, the first privately funded and crewed craft to enter space, launching an entirely new industry.)

In 1992, Rutan ran for Congress against Democratic Rep. George Brown Jr. in California's 42nd Congressional District in the Inland Empire. A surprise winner of the Republican primary, Rutan was beaten in the general election.

The pilot never lost his taste for pushing aviation's limits. In 1998, when he was 59, he and a co-pilot attempted to become the first balloonists to fly nonstop around the world. But the duo had to bail out and parachute to safety when the craft sprang a helium leak shortly after takeoff in New Mexico.

Rutan shrugged it off, noting he had had to bail out of planes twice before, including once in Vietnam when his jet was shot out of the sky. (The global circumnavigation was achieved the next year by a pair of Swiss and British balloonists.)

Not one to turn down an adventure, he got stranded in the North Pole for several days two years later when the Russian biplane carrying him and four others landed and partially sank through the ice. He wasn't seeking a record but just wanted to check out the pole.

Rutan set another aviation record in 2005 when, in his 60s, he flew some 10 miles in a rocket-powered plane launched from the ground.

Greg Morris, president of Scaled Composites, a Mojave aerospace company founded by Burt Rutan, said when he was about 7 he met the aviation pioneer and over the years always found him generous and welcoming.

“Bigger than life, in every sense of the word,” Morris said, noting Rutan’s legacy with Voyager, as a test pilot and in the military, where he earned a Silver Star, five Distinguished Flying Crosses, 16 Air Medals and a Purple Heart. "Any one of those contributions would make a legend in aviation. All of them together, in one person, is just inconceivable.”

Born July 1, 1938, in Loma Linda, Rutan is survived by his wife of 25 years, Kris Rutan; daughters Holly Hogan and Jill Hoffman, from a previous marriage; and grandchildren Jack, Sean, Noelle and Haley.

The Associated Press contributed to this article.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times .

INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS