- Press Releases

- Press Enquiries

- Travel Hub / Blog

- Brand Resources

- Newsletter Sign Up

- Global Summit

- Hosting a Summit

- Upcoming Events

- Previous Events

- Event Photography

- Event Enquiries

- Our Members

- Our Associates Community

- Membership Benefits

- Enquire About Membership

- Sponsors & Partners

- Insights & Publications

- WTTC Research Hub

- Economic Impact

- Knowledge Partners

- Data Enquiries

- Hotel Sustainability Basics

- Community Conscious Travel

- SafeTravels Stamp Application

- SafeTravels: Global Protocols & Stamp

- Security & Travel Facilitation

- Sustainable Growth

- Women Empowerment

- Destination Spotlight - SLO CAL

- Vision For Nature Positive Travel and Tourism

- Governments

- Consumer Travel Blog

- ONEin330Million Campaign

- Reunite Campaign

Economic Impact Research

- In 2023, the Travel & Tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP; an increase of 23.2% from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 level.

- In 2023, there were 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level.

- Domestic visitor spending rose by 18.1% in 2023, surpassing the 2019 level.

- International visitor spending registered a 33.1% jump in 2023 but remained 14.4% below the 2019 total.

Click here for links to the different economy/country and regional reports

Why conduct research?

From the outset, our Members realised that hard economic facts were needed to help governments and policymakers truly understand the potential of Travel & Tourism. Measuring the size and growth of Travel & Tourism and its contribution to society, therefore, plays a vital part in underpinning WTTC’s work.

What research does WTTC carry out?

Each year, WTTC and Oxford Economics produce reports covering the economic contribution of our sector in 185 countries, for 26 economic and geographic regions, and for more than 70 cities. We also benchmark Travel & Tourism against other economic sectors and analyse the impact of government policies affecting the sector such as jobs and visa facilitation.

Visit our Research Hub via the button below to find all our Economic Impact Reports, as well as other reports on Travel and Tourism.

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

- All Regions

- Measuring Employment in the Tourism Industries – Guide with Best Practices

This guide provides some examples of best practices of measuring employment in the tourism industries from countries that have demonstrated capacity to develop a comprehensive set of employment indicators.

This publication is a joint project by the International Labour Organization ( ILO ) and UNWTO.

ISBN : 978-92-844-1615-8

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Related Content

AM NEWS | VOL. 63 April 2024

UN Tourism News 81: Global Tourism Investments Trends a...

UN Tourism News 80: Diversification, Innovation and Sus...

AM NEWS | VOL. 62 March 2023

- Skip to main content

Advancing social justice, promoting decent work

Ilo is a specialized agency of the united nations, employment in the tourism industry to grow significantly.

The travel and tourism industry is one of the largest and most dynamic industries in today’s global economy. It is expected to generate about 9 per cent of total GDP and provide more than 235 million jobs in 2010, representing 8 per cent of global employment. Last November, over 150 government, employer and worker delegates from more than 50 countries, meeting at the ILO’s Global Dialogue Forum on New Developments and Challenges in the Hospitality and Tourism Sector, discussed new developments and challenges in the sector. The Forum was opened by Mr Taleb Rifai, Secretary-General of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and Mr Juan Somavia, Director-General of the ILO.

Compared to other sectors of the global economy, the industry is one of the fastest growing, accounting for more than one-third of the total global services trade. The ILO Forum addressed the high intensity of labour within the industry, making it a significant source of employment and placing it among the world‘s top creators of jobs that require varying degrees of skills and allow for quick entry into the workforce by youth, women and migrant workers.

According to an ILO report 1 prepared for the Forum, international tourism was affected by the global economic and social crisis but is projected to grow significantly over the coming decade. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is expecting the sector‘s global economy to provide 296 million jobs by 2019.

The tourism sector suffered a decline beginning in the second half of 2008 and intensifying in 2009 after several consecutive years of growth. A sharp reduction in tourist flows, length of stay and spending, as well as increased restrictions on business travel expenses, led to a significant contraction of economic activity in the sector worldwide.

Among the most affected during the crisis were international tourist arrivals, decreasing by 4 per cent in 2009, while international tourism revenues were projected to go down 6 per cent by the end of 2009. The regions hit hardest by the decline in worldwide international tourism were the Middle East (–4.9 per cent), Europe (–5.7 per cent), and the Americas (–4.6 per cent). Only Africa showed constant growth (+2.9 per cent), based on a comparatively low travel volume.

Despite the crisis, global employment in the tourism industry increased by about 1 per cent between 2008 and 2009, the report says. But there were significant regional differences with respect to the impact of the crisis on employment in hotels and restaurants. While the Americas suffered a 1.7 per cent decrease in employment, employment in Asia and the Pacific region remained resilient, gaining 4.6 per cent.

A need for more social dialogue

On the second day of the Forum a panel discussed new ideas concerning the huge potential for social dialogue in the sector and sustainable forms of tourism with a strong poverty reduction potential. The panel addressed good practices that could be shared with other developing countries, particularly within the framework of South–South development cooperation.

It was observed that the challenging work environment in the tourism industry also enhances the value of social dialogue in the workplace and, where such processes are formalized, they create real opportunities for constructive collaboration within major companies in the hotel and tourism sector.

At the same time, participants noted that the central role of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) within the sector makes the application of universal and formalized social dialogue difficult to achieve.

“A need for new and creative forms of social dialogue corresponding to the realities in a small company in the sector has become apparent. This could take the form of regular consultation between owners/managers and workforce representatives, as well as surveys of employee satisfaction and attitudes in order to highlight worker concerns,” explains Wolfgang Weinz, ILO Senior Technical Specialist for the Hotels, Catering, Tourism sector of the Sectoral Activities Department.

Training and skills needs

The Forum especially looked at education and vocational training as key requisites for the operational effectiveness of the sector. Its workers tend to have limited professional qualifications, and a need for enhanced training and education, including health-related issues, has become visible.

According to Wolfgang Weinz, “the growing significance of technology and more demanding customers, as well as environmental issues, require a more effective customer/employee relationship. Competitiveness and productivity in the industry depend on skill levels, professionalism, commitment, passion, loyalty and soft skills of the workers.”

Participants agreed that motivated workers are the most talented employees – willing to stay with their company. Some of the soft skills needed, including language and communication skills, courtesy, discipline, conscientiousness, self-confidence, adaptability, creativity and punctuality, can be enhanced through training. Gaps were also noted in the management capabilities – of management within the industry.

“Today we have a shortage of qualified employees. Hotels need to train their employees. It is the only way to improve the quality,” explained Ghassan Aidi, President of the International Hotel and Restaurant Association (IHRA).

The role of governments

The role of government was identified as key to developing the tourism industry. To become an attractive destination for tourists, a location requires a wide range of services including infrastructure and effective destination marketing.

Hotels and restaurants also have a huge potential to reduce poverty in many parts of the world. Partnerships between the private and public sectors should be enhanced to ensure more effective coordination and benefits for local communities.

According to Neb Samouth, Government representative of Cambodia and panellist, “Community-based tourism and ecotourism has benefited over 30 local communities, providing alternative sources of income and employment. Local projects help to protect natural resources and provided a good platform for social dialogue.”

The need to improve working conditions and the important role of social dialogue were stressed by Ron Oswald, General Secretary of the International Union of Food, Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers’ Associations (IUF): “Depending on what kind of tourism and of employment tourism brings to the poorest parts of the world, it can contribute to poverty reduction. Workers in tourism need to be given the ability to raise themselves out of poverty through representation organizations and ultimately, in ILO terms, collective bargaining.”

1 ILO: Developments and challenges in the hospitality and tourism sector (Geneva, 2010).

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

U.S. Department of Commerce

- Fact Sheets

Was this page helpful?

Fact sheet: 2022 national travel and tourism strategy, office of public affairs.

The 2022 National Travel and Tourism Strategy was released on June 6, 2022, by U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina M. Raimondo on behalf of the Tourism Policy Council (TPC). The new strategy focuses the full efforts of the federal government to promote the United States as a premier destination grounded in the breadth and diversity of our communities, and to foster a sector that drives economic growth, creates good jobs, and bolsters conservation and sustainability. Drawing on engagement and capabilities from across the federal government, the strategy aims to support broad-based economic growth in travel and tourism across the United States, its territories, and the District of Columbia.

The federal government will work to implement the strategy under the leadership of the TPC and in partnership with the private sector, aiming toward an ambitious five-year goal of increasing American jobs by attracting and welcoming 90 million international visitors, who we estimate will spend $279 billion, annually by 2027.

The new National Travel and Tourism Strategy supports growth and competitiveness for an industry that, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, generated $1.9 trillion in economic output and supported 9.5 million American jobs. Also, in 2019, nearly 80 million international travelers visited the United States and contributed nearly $240 billion to the U.S. economy, making the United States the global leader in revenue from international travel and tourism. As the top services export for the United States that year, travel and tourism generated a $53.4 billion trade surplus and supported 1 million jobs in the United States.

The strategy follows a four-point approach:

- Promoting the United States as a Travel Destination Goal : Leverage existing programs and assets to promote the United States to international visitors and broaden marketing efforts to encourage visitation to underserved communities.

- Facilitating Travel to and Within the United States Goal : Reduce barriers to trade in travel services and make it safer and more efficient for visitors to enter and travel within the United States.

- Ensuring Diverse, Inclusive, and Accessible Tourism Experiences Goal : Extend the benefits of travel and tourism by supporting the development of diverse tourism products, focusing on under-served communities and populations. Address the financial and workplace needs of travel and tourism businesses, supporting destination communities as they grow their tourism economies. Deliver world-class experiences and customer service at federal lands and waters that showcase the nation’s assets while protecting them for future generations.

- Fostering Resilient and Sustainable Travel and Tourism Goal : Reduce travel and tourism’s contributions to climate change and build a travel and tourism sector that is resilient to natural disasters, public health threats, and the impacts of climate change. Build a sustainable sector that integrates protecting natural resources, supporting the tourism economy, and ensuring equitable development.

Travel and Tourism Fast Facts

- The travel and tourism industry supported 9.5 million American jobs through $1.9 trillion of economic activity in 2019. In fact, 1 in every 20 jobs in the United States was either directly or indirectly supported by travel and tourism. These jobs can be found in industries like lodging, food services, arts, entertainment, recreation, transportation, and education.

- Travel and tourism was the top services export for the United States in 2019, generating a $53.4 billion trade surplus.

- The travel and tourism industry was one of the U.S. business sectors hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent health and travel restrictions, with travel exports decreasing nearly 65% from 2019 to 2020.

- The decline in travel and tourism contributed heavily to unemployment; leisure and hospitality lost 8.2 million jobs between February and April 2020 alone, accounting for 37% of the decline in overall nonfarm employment during that time.

- By 2021, the rollout of vaccines and lifting of international and domestic restrictions allowed travel and tourism to begin its recovery. International arrivals to the United States grew to 22.1 million in 2021, up from 19.2 million in 2020. Spending by international visitors also grew, reaching $81.0 billion, or 34 percent of 2019’s total.

More about the Tourism Policy Council and the 2022 National Travel and Tourism Strategy

Created by Congress and chaired by Secretary Raimondo, the Tourism Policy Council (TPC) is the interagency council charged with coordinating national policies and programs relating to travel and tourism. At the direction of Secretary Raimondo, the TPC created a new five-year strategy to focus U.S. government efforts in support of the travel and tourism sector which has been deeply and disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read the full strategy here

Share this page

This platform and its APIs have reached their end of life and will be switched-off at the end of May 2024.

Data are not updated anymore. We invite you to use instead our new data dissemination platform OECD Data Explorer.

To find the corresponding OECD Data Explorer dataset, see this Excel file.

- Data by theme

- Popular queries

- Business Demography

- Birth rate of enterprises

- Death rate of enterprises

- Enterprise survival rates

- Employment creation and destruction

- High-Growth enterprises rate (employment definition)

- High-Growth enterprises rate (turnover definition)

- Business Demography Indicators ISIC4

- High-Growth enterprises

- Medium and High-Growth enterprises

- Number of active enterprises

- Share of employer start-ups

- Structural Business Statistics

- All Businesses (SSIS)

- Mining and quarrying (By Size Class)

- Manufacturing (By Size Class)

- Electricity, gas & water (By Size Class)

- Construction (By Size Class)

- Wholesale and retail trade (By Size Class)

- Hotels & restaurants (By Size Class)

- Transport, storage & communications (By Size Class)

- Real estate, renting and business activities (By Size Class)

- Structural Business Statistics - ISIC4

- Employment of SMEs and large firms

- Number of SMEs and large firms

- Production by sector (Total size)

- Productivity of SMEs and large firms

- Total number of enterprises, by sector

- Turnover of SMEs and large firms

- Value added of SMEs and large firms

- I: TEC by Size classes

- II: TEC by Top enterprises

- III: TEC by Partner zones and countries

- IV: TEC by number of partner countries

- V: TEC by commodity groups (CPC)

- I - TEC by sector and size class

- III - TEC by partner zones and countries

- IV - TEC by number of partner countries

- IX - TEC by activity sectors

- V - TEC by commodity groups (CPC)

- VI - TEC by type of trader

- VII - TEC by ownership

- VIII - TEC by exports intensity

- X - TEC by partner countries and size-class

- Employer enterprise demography, Large TL2 and small TL3 regions

- Enterprise Demography (all firms, incl. non employer)

- Establishment Regional Demography

- Indicators of female entrepreneurship

- Timely Indicators of Entrepreneurship (ISIC4)

- New enterprise creations

- Bankruptcies of enterprises

- Exits of enterprises

- Timely Indicators of Entrepreneurship by Enterprise Characteristics

- Number of enterprise entries

- Number of enterprise exits

- Number of enterprise bankruptcies

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Venture capital investments

- Future of Business Survey

- Businesses by sector

- Businesses by size

- Businesses by age

- Businesses by sex, single owner

- Businesses by sex, multiple ownership

- Businesses and international trading

- Share of exporters by export scope

- Sources of business funding

- Outlook on business

- Outlook on job creation

- Positive business status and outlook, by sex

- Production and Sales (MEI)

- Work started

- STAN: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC4 SNA08)

- iSTAN: Indicators for structural analysis

- BTDIxE: Bilateral Trade by Industry and End-use

- TiM 2021: Trade in employment

- TiM 2023: Trade in employment

- TiM 2021: Trade in employment by characteristics

- IOTs 2021: Input-Output Tables

- IOTs 2018: Input-Output Tables

- IOTs 2015: Input-Output Tables

- TeCO2: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- TeCO2: Principal indicators

- Embodied CO2 emissions in trade

- Embodied CO2 emissions in trade: Principal indicators

- TiM 2019: Trade in employment

- ANBERD (R&D by industry)

- 1. TiVA 2018: Principal indicators

- 2. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in gross exports

- 3. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in final demand

- 4. TiVA 2018: Gross exports by origin of value added and final destination

- 5. TiVA 2018: Origin of value added in gross imports

- 1. TiVA 2016: Main indicators

- 2. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in gross exports

- 3. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in final demand

- 4. TiVA 2016: Gross exports by final destination

- 5. TiVA 2016: Origin of value added in gross imports

- TiVA, October 2015

- Trade in Value Added (TiVA): Core Indicators

- TiVA 2015: Origin of Value Added in Gross Exports

- TiVA 2015: Origin of Value Added in Final Demand

- TeCO2 2015: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- OECD Global Value Chains indicators – May 2013

- Indices of the number of production stages

- Participation indices

- TiVA Nowcast Estimates

- TiM 2015: Core Indicators

- BTDIxE 2016

- BTDIxE 2011

- BTDIxE 2012

- TeCO2 2013: CO2 emissions embodied in trade

- STAN 2016: Database for Structural Analysis

- STAN 2011: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC Rev.3 SNA93)

- STAN 2012: Database for Structural Analysis (ISIC Rev.4 SNA93)

- STAN 2005: Database for Structural Analysis

- STAN Indicators 2012

- STAN Indicators 2011 (ISIC3 SNA93)

- Manufacturing share of employment 1970-2009

- Manufacturing share of value-added 1970-2009

- R&D intensity of manufacturing sectors 1995-2009

- STAN Indicators 2009

- STAN Indicators 2005

- STAN I-O Intermediate Import Ratio, March 2012

- STAN Input-Output Total, Domestic and Imports, March 2012

- STAN I-O Imports content of Exports, March 2012

- STAN I-O Inverse Matrix Coefficients (Domestic), March 2012

- STAN I-O Inverse Matrix (Total), March 2012

- ANBERD: business enterprise R&D by industry (ISIC Rev. 3)

- ANBERD: business enterprise R&D by industry (ISIC Rev. 2)

- Services Trade Restrictiveness Index by services sector

- STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

- Digital STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Intra-EEA Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

- Intra-EEA STRI Heterogeneity Indices

- Steelmaking Capacity

- Receipts and expenditure

- Domestic tourism

- Inbound tourism

- Outbound tourism

Enterprises and employment in tourism

- Internal tourism consumption

- Key tourism indicators

- TiVA 2021: Principal Indicators

- Economic Outlook

- Gross domestic product (annual)

- Gross domestic product (quarterly)

- Composite Leading Indicators

- Consumer price indices - inflation

- Health Status

- Labour Market Statistics

- Monthly Monetary and Financial Statistics (MEI)

- Agricultural Outlook

- Bilateral Trade by Industry and End-use (ISIC4)

- Statistics from A to Z

This dataset preview is momentarily unavailable.

Please try again or select another dataset.

- Country [59 / 61]

- Tourism industry [18 / 18]

- Variable [2 / 2]

- Year [14]

- Table options

- Text file (CSV)

- Developer API

- Related files

Information

Statistics Explained will be under maintenance from 8pm to 11pm.Edition and login will not be available.

- Statistical themes

- Statistics 4 beginners

- Eurostat home

- Education corner

- Regional yearbook

- Sustainable development

- What links here

- Special pages

Tourism industries - employment

Data extracted in January 2022.

Planned article update: 13 May 2024.

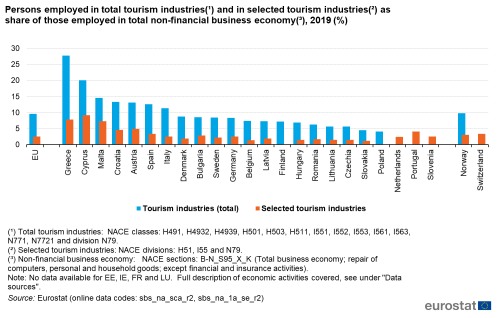

Persons employed in total tourism industries as share of those employed in non-financial business economy, 2019 (%)

- (¹) Total tourism industries: NACE classes: H491, H4932, H4939, H501, H503, H511, I551, I552, I553, I561, I563, N771, N7721 and division N79.

- (³) Non-financial business economy: NACE sections: B-N_S95_X_K (Total business economy; repair of computers, personal and household goods; except financial and insurance activities).

- Note: No data available for EE, IE, FR, LU, NL, PT, SI. Full description of economic activities covered, see under "Data sources".

- Source: Eurostat (online data codes: sbs_na_sca_r2, sbs_na_1a_se_r2)

This article presents recent statistics on employment in the tourism industries in the European Union (EU). Tourism statistics focus on either the accommodation sector (data collected from hotels, campsites, etc.) or on tourism demand (data collected from households), and relate mainly to physical flows (arrivals or nights spent in tourist accommodation or trips made by a country’s residents). However, this analysis of employment in tourism is based on data from other areas of official statistics, in particular structural business statistics (SBS), the labour force survey (LFS), the structure of earnings survey (SES) and the labour cost survey (LCS).

This article analyses the tourism sector with a focus on its contribution to the labour market in the EU and its potential to create jobs for economically less advantaged socio-demographic groups or regions.

Full article

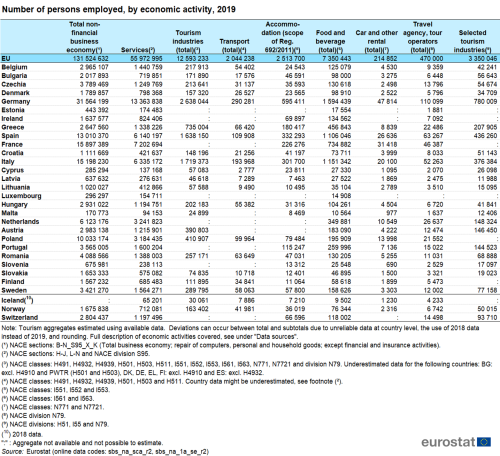

In 2019, the tourism industries employed over 12.5 million people in the eu.

Economic activities related to tourism (but not necessarily relying only on tourism — see the section "Data sources" for further details) employed over 12.5 million people in the European Union (see Table 1). Nearly 7.4 million of these people worked in the food and beverage industry, while 2 million were employed in transport. The accommodation sector (not including real estate) accounted for more than 2.5 million jobs in the EU; travel agencies and tour operators accounted for nearly half a million. The three industries that rely almost entirely on tourism (accommodation, travel agencies/tour operators, air transport) employed nearly 3.4 million people in the EU. These three industries will from now on be referred to as the "selected tourism industries".

In 2019 the tourism industries accounted for more than 22 % of people employed in the services sector. When looking at the total non-financial business economy, the tourism industries accounted for nearly 10 % of people employed. Among the Member States, Greece recorded the highest share (27.8 % or more than one in four people employed) followed by Cyprus and Malta with respectively one in five and more than one in seven people employed working in the tourism sector (see Figure 1).

In absolute terms, Germany had the highest employment in the tourism industries (2.6 million people, not including passenger rail transport interurban), followed by Italy (1.7 million) and Spain (1.6 million, not including taxi operation). These three Member States accounted for nearly half (48 %) of employment in the tourism industries across the EU.

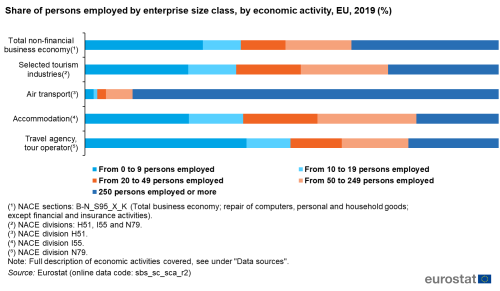

In 2019, one out of four (25 %) people employed in the selected tourism industries, worked in micro-enterprises that employ fewer than 10 people. This share is by four percentage points lower than the 29 % observed for the total non-financial business economy (see Figure 2). Looking at the three selected tourism industries separately, 39 % of employment in travel agencies and tour operators was in micro-enterprises while for the accommodation sector this figure was 25 %. Not surprisingly, small and medium-sized enterprises (< 250 staff) are of minor importance in air transport, with 89 % of people employed in the sector working in companies employing 250 people or more.

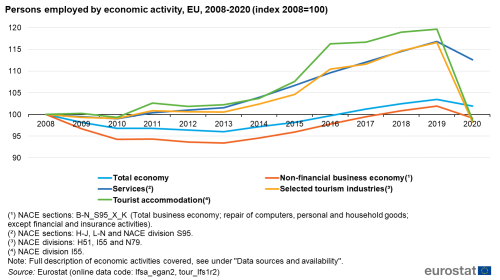

The economic crisis of 2008 led to a fall in total employment which started recovering in 2014 and reached the before crisis levels in 2016 (see Figure 3). However, this was not the case for the services sector, including the selected core tourism industries, which during the period 2008-2016 has had an average annual growth rate of +2.4 %. More specifically, during this period, the selected tourism industries registered an average annual growth of +2.0 %, while the average growth for the tourist accommodation sector was +3.8 %. This shows the tourism industry’s potential as a growth sector, even in times of economic turmoil that significantly affect other sectors of the economy.

The positive trend in employment in the selected core tourism industries continued until 2019 when the number of people employed in the sector reached +17 % compared with 2008.

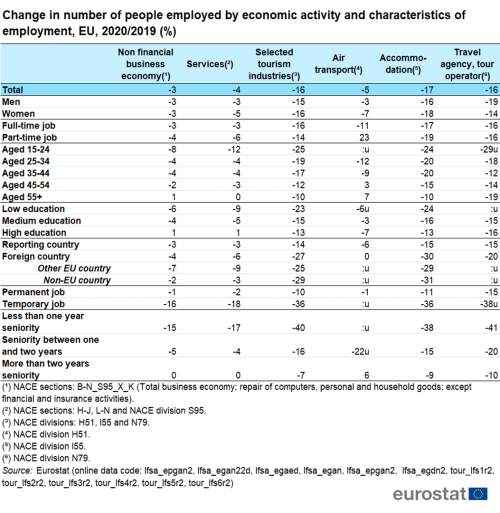

In 2020, COVID-19 pandemic has slowed economic activity and, as a result, the labour market. It clearly had a negative impact on employment but also pushed out people of unemployment by affecting their availability or their job search. Tourism was one of the most affected sectors due to the resulting travel restrictions, health protocols and the drop in demand among tourists. This was reflected to the employment in the selected tourism industries, with a sharp drop by -16 % in 2020 compared with 2019. This drop was significantly higher than the -3 % and -4 % observed for the non-financial business economy and the services sector respectively.

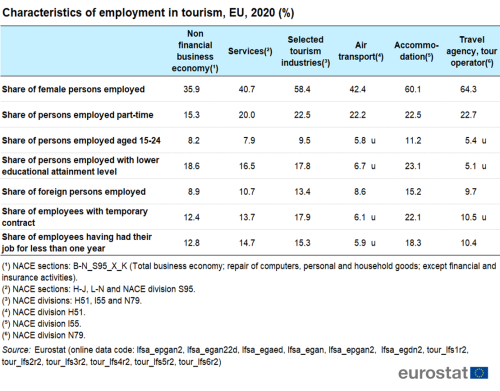

Characteristics of jobs in tourism industries

2020 was a special year due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The measures taken to contain the virus caused a severe economic recession. There was a hiring freeze in almost all the sectors with tourism being one of the most affected. People with less formal education, young people, people on temporary contracts or foreign workers were more likely to lose their job or have difficulties finding a job in tourism (see Table 3).

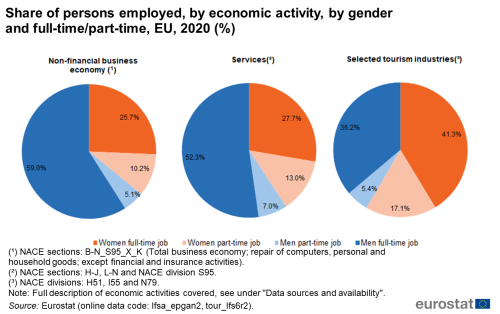

Tourism creates jobs for women

The tourism industry is a major employer of women (see Table 2, Figure 4 and Table 2A in the excel file ). In 2020, compared with the total non-financial business economy where 36 % of people employed were female, the labour force of the tourism industries included more female workers (58 %) than male workers. The highest proportions were seen in travel agencies and tour operators (64 %), followed by the accommodation sector (60 %). Even though nearly three out of ten women working in the tourism industries worked part-time (compared with just over one in ten men), women working full-time still represented the biggest share of employment (41 %, see Figure 4). Female employment accounted for less than half of tourism industry employment in only two Member States (Luxembourg and Malta); for the accommodation sector this was the case only for Malta. In Estonia, Latvia, Romania and Slovakia, more than two out of three people employed in tourism were women.

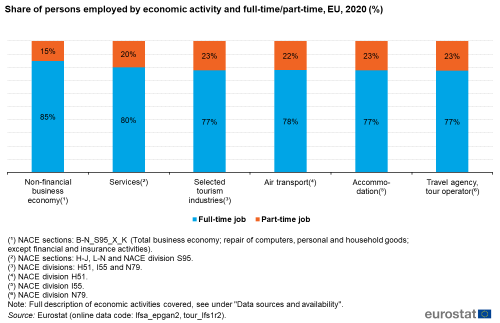

Part-time employment significantly higher in the tourism industries

In 2020, the proportion of part-time employment in the tourism industries (23 %) was significantly higher than in the total non-financial business economy (15 %) and was comparable to the figure for the services sector as a whole (20 %) (see Table 2, Figures 4 and 5, and Table 2B in the excel file ). Within the three selected tourism industries, the proportion of part-time employment in the accommodation sector and in travel agencies and tour operators was 23 %, while in air transport 22 % of staff worked on a part-time basis. In most Member States for which data is available, the tourism industries had a higher proportion of part-time employment than the rest of the economy. This was not the case for the popular tourism destinations of Greece, Spain and Cyprus where the proportion of part-time work in the tourism industries was equal or lower than in the rest of the economy. In Slovenia, the proportion of part-time workers in tourism was more than double compared to the economy as a whole.

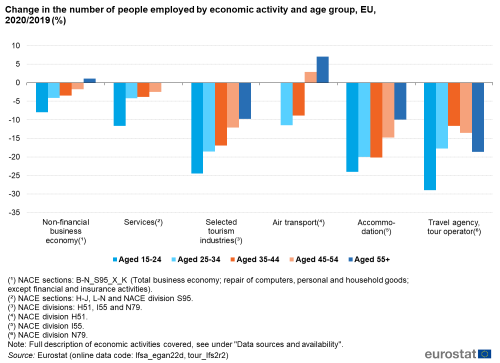

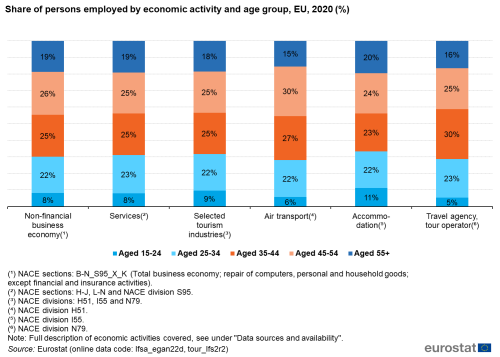

Tourism attracts a young labour force

Traditionally, the tourism industries have a particularly young labour force, as these industries can make it easy to enter the job market. In 2020 however, the COVID-19 crisis has affected labour market of young people aged 15-24 more than the other age groups. With a drop of -25 % compared with 2019, the impact on youth employment in the selected tourism industries was even harder than the impact on this age group in the rest of the non-financial business economy where the drop was -8 % (see Table 3 and Figure 6).

The share of young workers in the selected tourism industries remained however high in 2020, with close to one in ten people (9.5 %) aged 15 to 24, while only 8.2 % of the labour force in the non-financial business economy were young workers. In the big majority of EU countries with available data, the share of young workers in tourism industries was above the proportion seen in the economy as a whole. The highest proportions of employed people aged 15 to 24 were registered in Denmark (21 %), Ireland and the Netherlands (both at 19 %) (see Table 2 and Table 2C in the excel file ). In the subsector of accommodation, 11 % of the people employed were between 15 and 24 years old (see Figure 6a), while in the three above mentioned countries, at least 23 % of persons employed in this sector were aged 15 to 24.

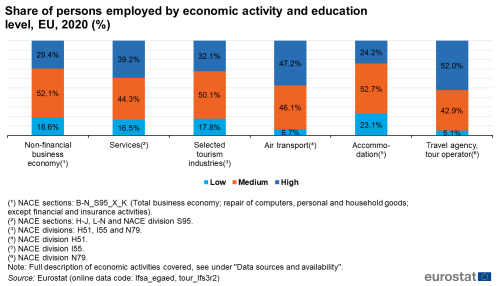

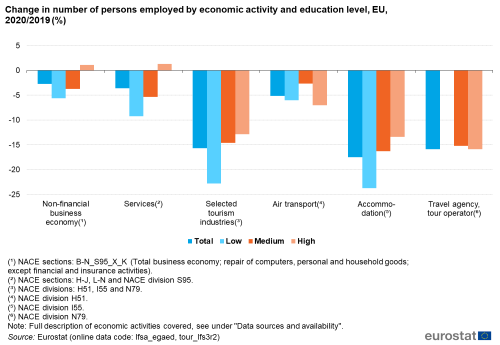

The tourist accommodation sector gives more opportunities to lower educated workers

The previous sections showed that tourism employs more female workers and young workers. In 2020, people with a lower educational level (those who have not finished upper secondary schooling) were more or less equally represented on the labour market as a whole and in the tourism sector (respectively 19 % and 18 %) — see Table 2, Figure 7 and Table 2D in the excel file . However, in the subsector of accommodation, 23 % of people employed had a lower educational level. In Malta and Portugal at least two out of five people employed in tourist accommodation belong to this group. However in these two countries lower educated people are more represented in the whole labour force compared with the rest of EU countries.

In 2020, however, as in the case of youth employment, people with a lower educational level were hit the hardest from the COVID-19 impact on employment. The drop in the employment in the selected tourism industries was -23 % for this group of workers, while it was -6 % in the non-financial business economy (see Table 3 and Figure 7a).

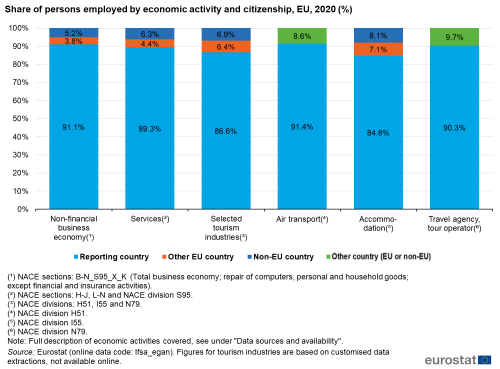

Nearly one in seven people employed in tourism are foreign citizens

Many foreign citizens work in tourism-related industries (see Table 2, Figure 8 and and Table 2E in the excel file ). In 2020, they accounted for 13 % of the labour force in tourism industries (of which 6 % were from other EU Member States and 7 % were from non-EU countries). In the services sector as a whole, the proportion of foreign citizens employed was 11 %, and in the total non-financial business economy it was 9 %. Looking at this in more detail, we see that foreign workers made up 9 % of the workforce in air transport and 10 % in travel agencies or tour operators, but 15% of the workforce in accommodation (i.e. more than one in seven people employed in this sub-sector was a foreign citizen).

In three EU Member States, more than one in three people employed in the selected tourism industries were foreign citizens: Cyprus (34 %), Luxembourg (58 %) and Malta (40 %).

In 2020 compared with 2019, the drop in the number of foreign workers was more significant in the selected tourism industries (-27 %, reaching -30 % in the segment of foreign citizens employed in the accommodation sector) than in the non-financial business economy (-4 %) (see Table 3).

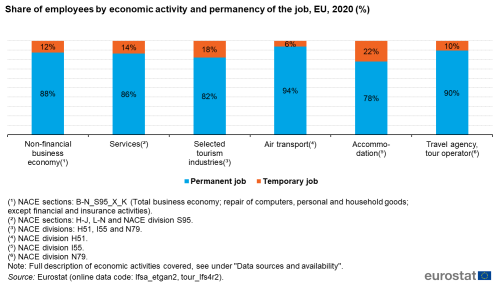

Jobs are less stable in tourism than in the rest of the economy

Since tourism tends to attract a young labour force, often at the start of their professional life (see above, Table 2 and Figure 6), certain key characteristics of employment in this sector are slightly less advantageous than in other sectors of the economy.

The likelihood of occupying a temporary job was significantly higher in tourism than in the total non-financial business economy (18% versus 12 % of people employed) – see Table 2, Figure 9 and Table 2F in the excel file . There are big differences across the European Union (ranging from less than 3 % of temporary contracts in tourism in Estonia, Lithuania and Romania to more than 30 % in Greece, Italy, Cyprus and Poland). In all but five countries (Estonia, Spain, Lithuania, Hungary and Malta), fewer people have a permanent job in tourism than in the economy on average. In Bulgaria, Greece and Cyprus, the proportion of temporary workers was three to four times higher in tourism than in the non-financial business economy as a whole. In the accommodation sector, more than one in five people employed did not have a permanent contract.

In 2020 compared with 2019 however, the drop in the number of people working with a temporary contract was -36 % in the selected tourism industries, significantly higher than the drop in the total non-financial business economy where it was -16 % (see Table 3).

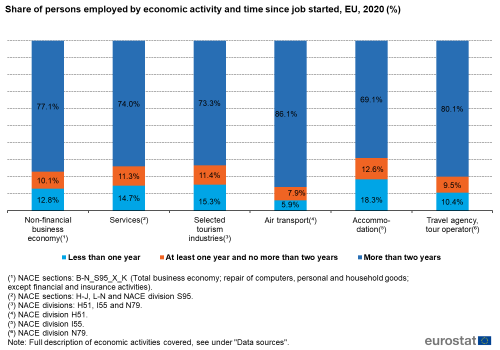

Similarly, the likelihood of an employee holding their current job for less than one year (see Table 2, Figure 10 and Table 2G in the excel file ) was also higher in tourism than in the non-financial business economy as a whole (15 % versus 13 %). In the economy on average, more than three out of four employees (77 %) had worked with the same employer for two years or more, while in tourism this is the case for 73 % of people employed. Air transport tends to offer more stable jobs, with only 6 % of employees having job seniority of less than one year, compared with 18 % in accommodation and 10 % for people employed by travel agencies or tour operators. More than one third of the workforce in the accommodation sector had held their job for less than one year in Greece and Cyprus.

However, as seen in the previous sections, employment in tourism was seriously affected by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with 2019, the drop in the number of people working with a temporary contract was -36 % in the selected tourism industries while in the non-financial business economy this was -16 % (see Table 3).

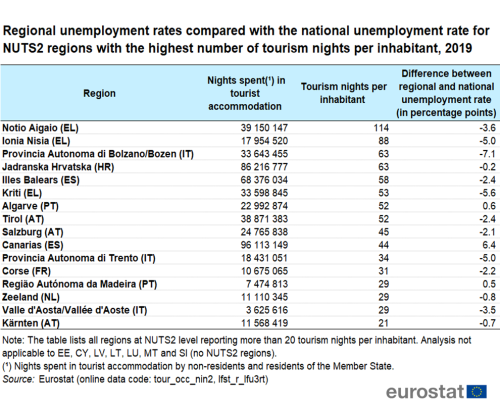

Regional issues in tourism activities

Regions with high tourist activity tend to have lower unemployment rates

Tourist activity can have a negative impact on the quality of life of the local population in popular tourist areas. However, the influx of tourists can also boost the local economy and labour market.

Comparing regional data on tourism intensity (e.g. the annual number of nights spent by tourists per capita of local population) with regional unemployment rates or their deviation from the national average unemployment rate, we see that in 2019, 22 of the 30 regions with the highest tourism intensity had an unemployment rate below the national average.

Table 4 lists the regions with a tourism intensity over 20 (tourism nights per local inhabitant). In all but three of these 20 regions, the unemployment rate lied below the national average. Two of the three regions where this did not hold true, the Canary Islands and Madeira, are island regions relatively remote from the mainland (and the mainland’s economy).

Earnings and labour costs in the tourism industries

Hourly earnings and labour costs in the accommodation sub-sector are below the average for the economy as a whole

Besides employment rates, another important feature of labour market analysis concerns labour costs for employers and earnings for employees. This section takes a look at hourly labour costs and hourly gross earnings, both in the economy as a whole and in the selected tourism industries.

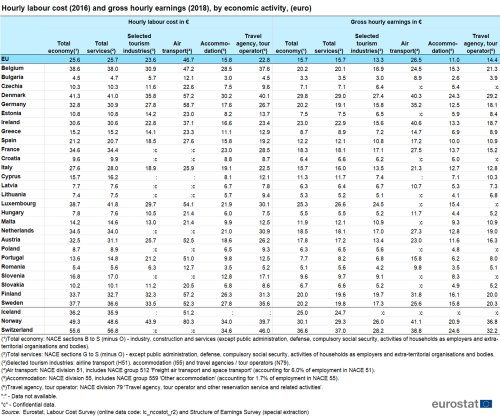

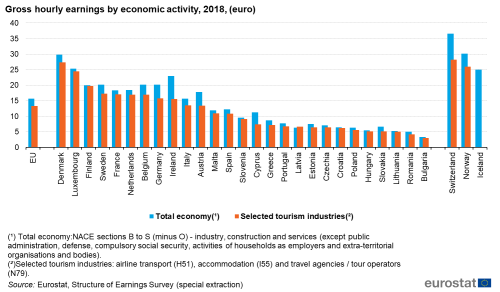

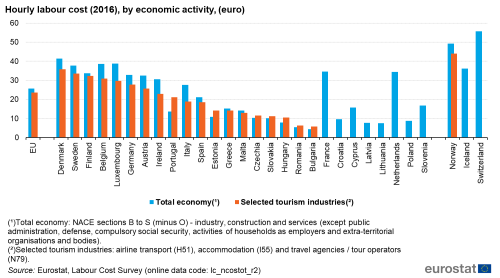

In the EU as a whole, labour costs and earnings tend to be significantly lower in the tourism industries than they are in the total economy. In the economy, the average hourly labour cost was €25.6 in 2016 and average hourly earnings were €15.7 in 2018. In the three selected tourism industries (air transport, accommodation, travel agencies & tour operators) the average hourly labour cost was €23.6 in 2016 and the average gross hourly earnings amounted to €13.3 in 2018 (see Table 5 and Figure 11).

Given the characteristics of tourism jobs outlined above, this observation does not come as a surprise: a relatively young labour force (see Figure 6a) with a higher proportion of temporary contracts (see Figure 9) and lower job seniority (see Figure 10) has a comparative disadvantage on the labour market, which leads to lower labour costs and earnings. For the accommodation sector — which employs more people with a lower educational level and more part-timers — the differences are even higher. In 2018, for people employed in the accommodation sub-sector, gross hourly earnings were €11.0. For air transport, they were €26.5 (well above the average for the economy as a whole), and for travel agencies and tour operators they were €14.4.

Gross hourly earnings in tourism were highest in Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway and Switzerland, but these countries were also among the top ten countries with highest average hourly earnings in the total economy (see Table 5 and Figure 12).

In 2016 only seven EU Member States had higher hourly labour costs in tourism than the total economy: Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia (see Table 5 and Figure 13); for gross hourly earnings, this was the case only for Latvia. Comparing the accommodation subsector with the economy as a whole, both hourly average labour costs and earnings were lower for those employed in accommodation, and this was true across the EU (see Figure 14).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

This article includes data from four different sources:

- Structural business statistics (SBS) .

- EU labour force survey (EU-LFS) .

- Labour cost survey (LCS) .

- Structure of earnings survey (SES) .

This data is available at a detailed level of economic activity, which makes it possible to identify and select industries that are part of the tourism sector.

For Eurostat, tourism industries (total) include the following NACE Rev.2 classes:

- H4910 — Passenger rail transport, interurban

- H4932 — Taxi operation

- H4939 — Other passenger land transport n.e.c

- H5010 — Sea and coastal passenger water transport

- H5030 — Inland passenger water transport

- H5110 — Passenger air transport

- I5510 — Hotels and similar accommodation

- I5520 — Holiday and other short-stay accommodation

- I5530 — Camping grounds, recreational vehicle parks and trailer parks

- I5610 — Restaurants and mobile food service activities

- I5630 — Beverage serving activities

- N7710 — Renting and leasing of motor vehicles

- N7721 — Renting and leasing of recreational and sports goods

- NACE division N79 — Travel agency, tour operator reservation service and related activities.

However, many of these activities provide services to both tourists and non-tourists – typical examples include restaurants catering to tourists but also to locals and rail transport being used by tourists as well as by commuters. For this reason, this publication focuses on the following selected tourism industries which rely almost entirely on tourism:

- H51 — Air transport (including H512 ‘Freight air transport’ which accounts for 6.0 % of employment in H51).

- I55 — Accommodation (including I559 ‘Other accommodation’ which accounts for 1.7 % of employment in I55).

- N79 — Travel agency, tour operator reservation service and related activities (including N799 ‘Other reservation service and related activities’ which accounts for 12.9 % of employment in N79).

According to a United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) publication titled " Tourism highlights ", the EU is a major tourist destination, with four of its Member States among the world’s top 10 destinations in 2019. Tourism has the potential to contribute towards employment and economic growth, as well as to development in rural, peripheral or less-developed areas. These characteristics drive the demand for reliable and harmonised statistics within this field, as well as within the wider context of regional policy and sustainable development policy areas.

Tourism can play a significant role in the development of European regions. Infrastructure created for tourism purposes contributes to local development, while jobs that are created or maintained can help counteract industrial or rural decline. Sustainable tourism involves the preservation and enhancement of cultural and natural heritage, ranging from the arts to local gastronomy or the preservation of biodiversity .

In 2006, the European Commission adopted a Communication titled " A renewed EU tourism policy: towards a stronger partnership for European tourism " (COM(2006) 134 final). It addressed a range of challenges that will shape tourism in the coming years, including Europe’s ageing population, growing external competition, consumer demand for more specialised tourism, and the need to develop more sustainable and environmentally-friendly tourism practices. It argued that more competitive tourism supply and sustainable destinations would help raise tourist satisfaction and secure Europe’s position as the world’s leading tourist destination. It was followed in October 2007 by another Communication, titled " Agenda for a sustainable and competitive European tourism " (COM(2007) 621 final), which proposed actions in relation to the sustainable management of destinations, the integration of sustainability concerns by businesses, and the awareness of sustainability issues among tourists.

The Lisbon Treaty acknowledged the importance of tourism — outlining a specific competence for the EU in this field and allowing for decisions to be taken by a qualified majority. An article within the Treaty specifies that the EU "shall complement the action of the Member States in the tourism sector, in particular by promoting the competitiveness of Union undertakings in that sector". " Europe, the world’s No 1 tourist destination — a new political framework for tourism in Europe " (COM(2010) 352 final) was adopted by the European Commission in June 2010. This Communication seeks to encourage a coordinated approach for initiatives linked to tourism and defined a new framework for actions to increase the competitiveness of tourism and its capacity for sustainable growth. It proposed a number of European or multinational initiatives — including a consolidation of the socioeconomic knowledge base for tourism — aimed at achieving these objectives.

Direct access to

- All articles on tourism statistics

- Tourism industries - economic analysis

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (t_employ) , see:

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (employ) , see:

- Structural business statistics (sbs) , see:

- Employment and unemployment (Labour force survey)

- Structural business statistics (SBS)

- Recent Eurostat publications on tourism

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1051/2011 of 20 October 2011 implementing Regulation (EU) No 692/2011 concerning European statistics on tourism, as regards the structure of the quality reports and the transmission of the data.

- Regulation (EU) No 692/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2011 concerning European statistics on tourism and repealing Council Directive 95/57/EC.

- Summaries of EU Legislation: Tourism statistics

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain Tourism , Labour market .

- European Commission – Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs: Tourism

- Industry, trade, and services

- Tourism industries

- Statistical article

- Employment by sector

- ISSN 2443-8219

- This page was last edited on 6 March 2024, at 17:41.

- 1 watching user

- Privacy policy

- Accessibility

- About Statistics Explained

- Disclaimers

- Tourism employment

Related topics

- Innovation and Technology

Employment in tourism data refer to people or jobs. In the case of people, the data refer to employees only or to employees and self-employed people (employed people). Full-time equivalent employment is the number of full-time equivalent jobs, defined as total hours worked divided by average annual hours worked in full-time jobs.

Latest publication

- Industrial production

- Tourism GDP

- Tourism receipts and spending

- Tourism flows

Tourism employment Source: Key tourism indicators

- Selected data only (.csv)

- Full indicator data (.csv)

- Add this view

- Go to pinboard

©OECD · Terms & Conditions

Perspectives

Compare variables

Highlight countries

Find a country by name

Currently highlighted

Select background.

- European Union

latest data available

Definition of Tourism employment

Last published in.

Please cite this indicator as follows:

Related publications

Source database, further indicators related to industry, further publications related to industry.

Your selection for sharing:

- Snapshot of data for a fixed period (data will not change even if updated on the site)

- Latest available data for a fixed period,

- Latest available data,

Sharing options

Permanent url.

Copy the URL to open this chart with all your selections.

Use this code to embed the visualisation into your website.

Width: px Preview Embedding

Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World Research Paper

The increasing cases of unemployment in most countries are alarming. Most governments are trying to create various ways of providing jobs for their residents.

One sector that has potential to offer jobs to many people is the tourism industry. This paper is going to review several literature sources in order to describe the relationship and link between tourism and employment in the present world.

Tourism industry is among the leading and most vibrant industries in the current global economy. Projections in the tourism industry indicate that the industry will cover 9 percent of total GDP and offer over 235 million occupations representing 8 percent of the worldwide employment in a few years from now (ILO News par.3).

Evaluated against other segments of the worldwide economy, the tourism sector is among the fastest growing sectors comprising over a third of the overall global services trade (ILO News par.3).

Most governments rely on the tourism sector for job creation. The South African government recognizes the significance of this sector since at least one job becomes created for each 16 tourists who visit the nation (Brand South Africa par.5).

Zuma, the president of South Africa, is optimistic that the increase in number of tourists is a chief way of dealing with unemployment in the country.

In 2010, the number of tourists visiting South Africa increased by a million, and presently the country is seeking to increase the number of global conferences and sports occasions in an effort to increase tourist arrivals (Brand South Africa par. 5).

Tourists’ consumption expenditures offer direct or indirect employment openings in the tourism industry. Every tourist spending empowers the tourism segment directly as well as other segments which provide input to the tourism industry indirectly to produce employment capacity (ILO News par.2).

Also, tourism has an effect on total employment of a nation through the common impacts of employment on the economy (Onder and Ayse 365).

Service is a fundamental aspect in the tourism segment. Tourism segmnet requires workers to deal with both production and offering services (Onder and Ayse 366). The sector comprises a vast deal of employment areas because of its labor intensive fabrication (ILO News par.6).

The industry has high labor intensity, and this makes the sector a noteworthy source of employment. While there are technological advancements in this industry, such technologies reduce the need for employees modestly because of restricted use of computerization and mechanization in the tourism sector.

Hence, tourism growth has led to generation of numerous job openings both in emerging and developed nations.

Employment in the tourist sector became affected by the global economic crisis. The ILO News revealed that the global economic crisis affected global tourism. (par.3). At the same time, ILO News projected that rampant growth was likely to occur in coming years, thus creating an increased number of jobs (par.3).

As from the second half of 2008, the tourism industry started experiencing a decline, which grew immensely in 2009. Rapid decline in duration of stay and expenditure, tourist travels as well as augmented limitations on business travel expenses caused a momentous reduction of economic activity in the global tourist industry.

However, global employment in the industry rose by 1% between 2008 and 2009 with noteworthy regional disparities with regard to the effect of the crisis on levels of employment (ILO News par.4).

While tourism sector has potential to create many jobs, employees in this sector require diverse skills. The ILO News positions tourism as a supreme job creator that needs different levels of skills (par.5). Such skills can be enhanced through vocational training and education.

The ILO News reveals that most workers in the tourism sector have inadequate professional qualifications, and thus there is a need for further training on key issues such as health (par.5).

This can be steered by the growing impact of technology, environmental concerns as well as demanding customers. Besides, efficiency and competitiveness in the sector rely on professionalism, skills and dedication of the employees.

Different nations advocate for skill development programs in order to enhance the process of job creation in the tourism factor. For instance, Shri Subodh Kant Sahai of India has ordered additional efforts on skill development program in his tourism ministry in order to enhance the process of job creation in the tourism sector (Travel trade journal.com par.1).

People trained under this program were gained over into different prominent chains of hotels where they are currently doing extremely well (Travel trade journal.com par.2). An example of a skill development program in India is the Hunar Se Rozgar scheme.

The proprietor of this program plans to extend the program to incorporate new trade courses such as retail marketing, driving, and reception. The idea behind the provision of these courses is that they can promote job creation features in accordance with the industry demand.

Besides, there exists a direct connection between tourism sector and other industries including lodging, transport, management, travel agents, entertainment, health and finance (Travel trade journal.com par.2).

Tourism can generate three employment forms in states and regional markets including indirect employment, direct employment and induced employment (Mathieson and Geoffrey 77).

Indirect employment comprises employment in other industries that never provide directly to touristic clients, although, they obtain revenue from payments done in touristic dealings with other industries that supply input for tourism segment.

Examples of employees who can be included in the category of indirect employment include persons employed in building an extra unit to expand capacity of a housing facility, or workers employed in a production facility, which creates the material to be erected for transaction in this facility.

Direct employment is the employment that becomes offered in tourism facilities like food, housing, food, travel agents and shipping, which subsist in the tourism industry and provide with needs of tourists directly (Mathieson and Geoffrey 77).

Further, induced employment denotes the supplementary employment that occurs due to reutilization of the proceeds obtained through indirect and direct employment ways. People, whose earnings and life standards rise due to their tourism actions generate new employment openings by spending their earnings in other segments of the economy.

Establishing the exact impact of tourism on employment is a complex task. Homafar et al. give some reasons as to why it is difficult to establish the impact of tourism on employment (35). First, most people who work in the tourist sector can barely be differentiated from those that work in identical or comparable positions unrelated to tourism.

For example, official data relates lodging facilities with food facilities such as restaurants. Besides, employment in diverse sectors of the transport industry obtains representation without regarding to the relationship with tourism.

Again, there exist several small firms that offer tourism services, and the proportions of persons who work in self enterprises hardly obtain consideration while computing the total workforce. As a result, employment figures for tourism segment are not likely to demonstrate the real circumstance.

Further, tourists activities increase in some months and the amount of people employed in tourism services vary significantly from time to time. Onder and Ayse explain that the impact of tourism on employment amplifies depending on expansion in tourism and force (367). Tourism generates both employment and revenue.

Tourism can build employment facilities in both tourist sending areas and tourist receiving areas, in dissimilar ratios since different service departments obtain use in sender nations in order to execute some facilities required ahead of travel.

For instance, insurance, cargo and telephone activities must be carried out prior to travel. However, Onder and Ayse acknowledge that a comparison between job creation in tourists receiver states and tourist sending nations demonstrates that receiver countries benefit more in terms of job creations than sending nations (367).

Some issues employees are facing in the tourist sector include low payments, lack of social security and increased cases of personnel transfer. Tourism is a seasonal activity, which makes the industry prone to be influenced by negative advances in politics and economy (Homafar et al. 36). For instance, low economic situation may cause the sector to pay low wages to employees.

There exist many aspects of tourism in regard to employment. First, the seasonal nature of tourism allows underemployment thus making employment in the sector to be a seasonal phenomenon.

Second, the impact of employment in the tourism industry is normally a veiled one because the industry shifts manpower from other segments and nearly all workers in the industry lack insurance.

Third, the fact that skilled workers obtain permanent employment while unskilled employees obtain impermanent employment causes low, work productivity, which weakens economic growth in the tourism industry.

Full employment may be attained during peak seasons, although the decline in employment during low seasons brings many social costs. Efforts to eradicate these costs may include employing interns or related personnel who are usually free during peak seasons.

Fifth, women in the tourism industry comprise a bigger proportion than women in other industries. The last but not least, the sector offers employment chances mainly to people with similar investment quantities because the capital amount that is essential for generating business dimensions for a single person is less than other industries.

In conclusion, studies on tourism and employment demonstrate that tourism has desirable effects on employment. The industry is labor intensive and thus, creates a vast number of employment facilities.

Tourism facilities profit from labor personnel in both manufacturing and distributing tourism products. Tourists’ payments act as a source of wages to employees in the tourism sector. While there are technological advancements in the tourism industry, they reduce the need for employees modestly owing to restricted use of computerization and mechanization in the tourism sector.

Employees in the tourism sector require training and skill development as the industry requires different levels of skills. Finally, decline in the span of stay and expenditure, tourist travels as well as augmented limitations on business travel affect economic activities in the global tourist industry, including employment.

Works Cited

Brand South Africa. 2011 South Africa’s Year of Job Creation: Zuma. 2011. Web.

This article discusses several initiatives proposed by Zuma, the president of South Africa for enhancing job creation. This piece is relevant to this study as it recognizes the value of tourism in job creation.

The president explains that the country seeks to increase the number of global conferences and sports occasions, with the ultimate objective of creating jobs.

Homafar, Fazele, Habib Honari, Akbar Heidary, Taghi Heidary and Afsane Emami. “The Role of Sport Tourism in Employment, Income and Economic Development.” Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism 2.3 (2011): 34-37. Print.

This article is a survey on perceptions of managers and tourism ideas about the role of sports induced tourism in employment creation. This piece of work is significant for this study as it demonstrates the relationship between tourism and employment.

ILO News. Employment in the Tourism Industry to Grow Significantly . 2010. Web.

This article represents a discussion of a global forum held by delegates from different countries in order to discuss challenges facing the tourism industry.

This article is significant for the study as it describes the growth of tourism and employment in the industry through the global crisis. The article also highlights the need for training and education in developing employment in the sector.

Mathieson, Alister and Geoffrey Wall. Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impact . London, Harlow: Pearson Education, 2010. Print.

This book discusses economic, social and physical impacts of tourism. The book is significant for this study as it describes how tourism can generate different forms of employment.

Onder, Kubra and Ayse Durgun 2010, Effects of Tourism Sector on Employment in Turkey: An Econometric Application. Web.

This article discusses the situation of the tourism industry in Turkey, especially after 1980. The article is significant for this study as it uses an empirical approach to demonstrate the relationship between tourism and employment.

Travel trade journal.com. n. d. Ministry of Tourism: Subodh Kant Inaugurates National Workshop on Hunar Se Rozgar . Web.

This article includes the words of Shri Subodh Kant Sahai, who is a tourism minister in India. The article emphasizes on the need for skill development in the tourism sector.

This piece is significant for this research as it demonstrates that equipping young people with new skills facilitates job creation in the tourism industry.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 12). Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/

"Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." IvyPanda , 12 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World'. 12 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

1. IvyPanda . "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Tourism’ and Employment’ Relationship in the Present World." January 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/tourism-and-employment/.

- International Labour Organisation in Australia

- Labor Market: Equality Promotion

- Legislative Changes Need in the Current Uae Labour Law

- Ohio Alliance to End Sexual Violence Seeking Community Safety

- Trade Unions History and Development

- Health and Safety Laws in the Oil and Gas Sector

- Child Labor Controversy and Regulations

- Merger & Acquisition in the Public Service Commission

- Child Labor in Turkish Cotton Industry

- Tourism in a Goa

- Benefits of Tourism

- Eco Tourism and Hospitality Industry

- Socio Economic Impacts of the “Enclave Tourism” Development

- Assessing the future for high street travel agents in the UK

- The tourism sector in the Australia Capital Territory

The Straits Times

- International

- Print Edition

- news with benefits

- SPH Rewards

- STClassifieds

- Berita Harian

- Hardwarezone

- Shin Min Daily News

- SRX Property

- Tamil Murasu

- The Business Times

- The New Paper

- Lianhe Zaobao

- Advertise with us

More Gen Zs look to the hospitality and tourism industry for meaningful jobs

SINGAPORE – Guest relations executive Elaine Chua works 9½-hour shifts five days a week at Swissotel The Stamford. Even though the 24-year-old’s schedule changes weekly, and some days start earlier and end later than others, she finds it easy to be motivated for work.

Beyond working the check-in counters, she also supports the teams handling foreign airline crew stays and assists with operations in the executive lounge. Part and parcel of the job is resolving guest complaints and offering service recovery options such as discounts or complimentary upgrades to keep customers happy, which can be stressful.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Read the full story and more at $9.90/month

Get exclusive reports and insights with more than 500 subscriber-only articles every month

ST One Digital

$9.90 $9.90/month.

No contract

ST app access on 1 mobile device

Subscribe now

Unlock these benefits

All subscriber-only content on ST app and straitstimes.com

Easy access any time via ST app on 1 mobile device

E-paper with 2-week archive so you won't miss out on content that matters to you

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

- Hospitality

- Travel and leisure

Read 3 articles and stand to win rewards

Spin the wheel now

Impacts of tourism and the generation of employment in Mexico

Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Análisis Turístico

ISSN : 2254-0644

Article publication date: 26 September 2019

Issue publication date: 26 September 2019

This paper aims to study the relationship between employment and tourism activities as well as economic variables for the 32 states of Mexico for the period 1999-2014.

Design/methodology/approach

To study the case of Mexico, the authors use panel data and cointegration panel data. They also use geographic information systems to observe changes over time between the variables, which is useful in the empirical evidence.

The main results obtained by the models are as following: domestic tourism is the variable with the greatest impact on the generation of direct employment in the tourism sector, a finding supported by both methodologies; economic growth (measured by state gross domestic product) also directly impacts the generation of employment; and the cointegration of the panels causes a long-term equilibrium among the states and some variables.

Research limitations/implications

The model used leaves out other variables that may influence the performance of the tourist activity. In addition, given the availability of official and homogeneous information, it only covers what has been documented up to 2014.

Social implications

The aim is to measure the impact of tourism on the variables at the state level, where the economic activities could be based on public policies, as well as the importance of tourism activities in generating employment. In this sense, the impact would be in channeling efforts to support the main economic activities and could serve as a starting point for the evaluation of programs to promote domestic tourism.

Originality/value

This paper reviews the relationship that exists between tourism activity and its effect on other variables, especially employment. It is the first time that these topics are studied for the Mexican economy.

- Cointegration panel data

Gómez López, C.S. and Barrón Arreola, K.S. (2019), "Impacts of tourism and the generation of employment in Mexico", Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Análisis Turístico , Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 94-114. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTA-10-2018-0029

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Claudia Susana Gómez López and Karla Susana Barrón Arreola.

Published in Journal of Tourism Analysis: Revista de Análisis Turístico . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

The rapid advance of tourism and its potential for growth has accelerated even further in recent years, particularly in developing countries, as is the case with Mexico. Tourism activities, in the widest sense of the term, are considered a key variable in local, regional, national and international economic growth, due to the fact that they are based on foreign currency income, as well as generating employment and creating services and related activities.

According to the United Nations’ World Tourism Organization ( UNWTO, 2013 ), tourism has undergone continuous expansion and diversification, becoming an important and growing economic sector on a global level. On an international level, in 2012, it contributed 9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), creating, on average, one out of every eleven jobs and generating income that represented around 6 per cent of world exports. In real terms, in the same year, income grew by 4 per cent, reaching a record US$1tn 75bn. In terms of this indicator, this growth is similar to the 4 per cent increase in visits by international tourists, making evident the strong correlation between the two indicators. The most recent data indicates that this activity contributes 10 per cent of global GDP, generating one out of 10 jobs and US$1.6tn in exports, which represents 7 per cent of global exports and 30 per cent of services ( United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2017 ).

According to the Economic Census conducted in Mexico in 2014, the tourism sector represented 11.7 per cent of the economic units of the national total, generated approximately 6.5 per cent of GDP, comprised 12.7 per cent of formal national employment, and provided 7.9 per cent of the national total for wages (National Institute for Statistics, Geography and Information, INEGI, 2017 ). Moreover, in 2016, the tourism sector represented 8.7 per cent of GDP, employing approximately 10 million people ( De la Madrid, 2017a ). In fact, in the first half of 2017, approximately 19.2 million international tourists visited Mexico, generating an income of US$11,104bn for this period ( De la Madrid, 2017b ). According to the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017[ 1 ] [ World Economic Forum (WEF), 2017 ], Mexico had risen eight positions from its 22nd place in the 2015 rankings. According to this report, emerging economies, of which Mexico is one, are gaining on advanced economies.

In some countries, international tourism has acquired ever-greater importance, representing, in Mexico, at least the third largest source of international income, behind income from petroleum and remittances sent home by Mexican migrants. Furthermore, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2017) has documented that, in Mexico, national tourism contributed 88 of every 100 pesos spent in the sector, having a direct impact on host communities. Compared to the flow of international tourists, which is concentrated in destinations such as Cancun or Los Cabos, national tourism is distributed across the entire national territory.

The positive evolution of tourism and its potential for growth have increased over recent years, establishing tourism as a source of growth ( tourism-led growth hypothesis ), especially in developing economies, as is the case with Mexico.

In general, it is thought that, like exports, the growth of tourism contributes positively to economic growth. However, despite the robust verification of the hypothesis postulating exports as a motor of growth, many studies have not found that exports contribute definitively to a country’s capacity to produce goods and services ( Darrat, 1986 ; Dodaro, 1993 ; Hsiao, 1987 ). Given that tourism may play a similar role in the economy of every country, the question has been asked for years as to the contribution of national tourism to economic growth.

This relationship is important as it enables the private and public sectors to plan and manage tourism activities with the objective of maximizing the benefits they provide. The general thesis is that tourist areas will generate a sufficient flow of visitors to drive economic growth at a regional, state and, therefore, national level.

Highlighted among the effects considered for measuring the impact of tourist destinations are the increase in foreign currency income, the generation of sources of local income with the externality effects of driving increased activity in other economic sectors, and the growth in direct and indirect employment. In terms of this last effect, however, other studies have established that tourism activities have no effect on formal employment, given their seasonality.

the question as to whether annual data are sufficient for representing the long-term relationship between both variables;

the inability of the annual data to eliminate the problems of short-term fluctuations due to economic cycles and structural changes; and

the inability to delineate economies with special characteristics in terms of distinct causal relationships.

An important advantage of tourism is its generally high level of income elasticity given the demand for tourist services ( Baretje and Defert, 1972 ). A recognized disadvantage is that the concentration of tourist activities could lead to a more vulnerable economic structure, given the natural absence of relationships with the industrial and/or productive sector in general.

In terms of public policy, the promotion of balanced economic development requires a detailed analysis of the determinants and effects of tourism activity. Highlighted among the important variables to consider in the development of tourism at a national level are the growing demand for associated services and the affinity with the geographical, natural and cultural characteristics of the regions in which it is based. While it is certain that a high number of tourists represents a considerable source of income at a local level, negative impacts on natural capital and cultural resources are also often observed.

In both the short and long term, tourism (both local and domestic) may make a significant contribution to a nation’s economic growth, while its potential generation of income and employment may be limited by its ability to offer the goods and services demanded by tourists. This may result, for example, from the fact that intermediate imports are commonly brought in from their countries of origin to meet tourists’ consumption habits. Despite this, given the offer of tourism and the infrastructure available, the income from tourists has a considerable effect on well-being and economic activity in the host countries. At an international level, tourist exports, in terms of people, services and foreign currency, result from increased levels of income in the countries of origin, local labor policy, and the reduced cost of international, principally air, transport. Moreover, it is important to note that the attraction of international currency improves balance of payments indicators and contributes to generating stability in the exchange rate system.

It should also be noted that, to a great extent, the majority of the organizations operating in the tourism sector correspond to micro, small and, in some cases, medium-sized enterprises. Furthermore, in terms of factors of production, the sector is work intensive, absorbing labor in the primary and service sectors and, thus, in some senses, reducing the indicators associated with local unemployment.

The relationship between human capital and productivity in tourism activity has been analyzed in developing economies, particularly the elements associated with the scarcity of personnel trained for work in this sector. The importance of personal services in this industry, in which national and foreign tourists interact constantly with staff from this sector, requires the consideration of variables, such as the educational level of tourism workers and the quality of the services and/or products. The difficulties of delimiting the tourism sector complicate the study of human capital and the extant abilities required by this economic sector. Some of the most relevant questions relating to human capital in this sector refer to the contribution of labor, either vocationally or academically trained, to the productivity of the sector and the generation of related public policy, among others.