More than 100,000 tourists will head to Antarctica this summer. Should we worry about damage to the ice and its ecosystems?

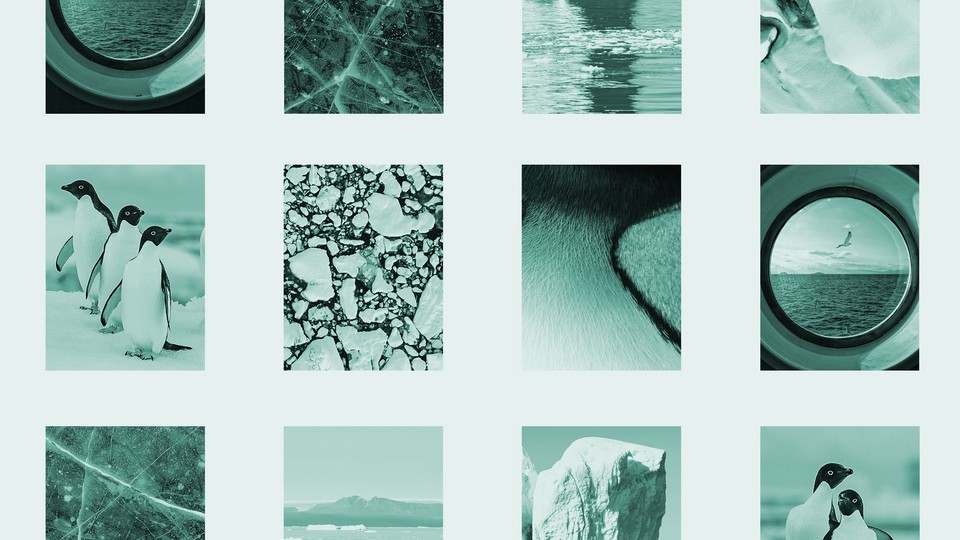

More than 100,000 tourists are heading to Antarctica this summer via cruise ship. Image: Unsplash/James Eades

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Elizabeth Leane

Can seng ooi, carolyn philpott, hanne nielsen.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Antarctica is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Visitor numbers to Antarctica have grown more than 40% since the COVID summer of 2020-21.

- Tourism in Antarctica has environmental impacts, including the release of black carbon from cruise ship funnels and the potential for the introduction of invasive species.

- As Antarctic tourism booms, some advocacy organisations have warned the impact may be unsustainable.

- The Antarctic Treaty System signed by countries with an Antarctic presence or interest ensures tour operators based in those nations have to follow stringent environmental regulations.

As the summer sun finally arrives for people in the Southern Hemisphere, more than 100,000 tourists will head for the ice. Travelling on one of more than 50 cruise ships, they will brave the two-day trip across the notoriously rough Drake Passage below Patagonia, destined for the polar continent of Antarctica.

During the COVID summer of 2020-21, just 15 tourists on two yachts visited Antarctica. But now, tourism is back – and bigger than ever. This season’s visitor numbers are up more than 40% over the largest pre-pandemic year .

So are all those tourists going to damage what is often considered the last untouched wilderness on the planet? Yes and no. The industry is well run. Tourists often return with a new appreciation for wild places. They spend a surprisingly short amount of time actually on the continent or its islands.

But as tourism grows, so will environmental impacts such as black carbon from cruise ship funnels. Tourists can carry in microbes, seed and other invasive species on their boots and clothes – a problem that will only worsen as ice melt creates new patches of bare earth. And cruise ships are hardly emissions misers.

How did Antarctic tourism go mainstream?

In the 1950s, the first tourists hitched rides on Chilean and Argentinian naval vessels heading south to resupply research bases on the South Shetland Islands. From the late 1960s, dedicated icebreaker expedition ships were venturing even further south. In the early 1990s, as ex-Soviet icebreakers became available, the industry began to expand – about a dozen companies offered trips at that time. By the turn of this century, the ice continent was receiving more than 10,000 annual visitors: Antarctic tourism had gone mainstream.

What does it look like today?

Most Antarctic tourists travel on small “expedition-style” vessels, usually heading for the relatively accessible Antarctic Peninsula. Once there, they can take a zodiac boat ride for a closer look at wildlife and icebergs or shore excursions to visit penguin or seal colonies. Visitors can kayak, paddle-board and take the polar plunge – a necessarily brief dip into subzero waters.

For most tourists, accommodation, food and other services are provided aboard ship. Over a third of all visitors never stand on the continent.

Those who do set foot on Antarctica normally make brief visits, rather than taking overnight stays.

For more intrepid tourists, a few operators offer overland journeys into the continent’s interior, making use of temporary seasonal camp sites. There are no permanent hotels, and Antarctic Treaty nations recently adopted a resolution against permanent tourist facilities.

As tourists come in increasing numbers, some operators have moved to offer ever more adventurous options such as mountaineering, heli-skiing, underwater trips in submersibles and scuba diving.

Is Antarctic tourism sustainable?

As Antarctic tourism booms, some advocacy organisations have warned the impact may be unsustainable. For instance, the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition argues cruise tourism could put increased pressure on an environment already under significant strain from climate change.

In areas visited most by tourists, the snow has a higher concentration of black carbon from ship exhaust, which soaks up more heat and leads to snow melt. Ship traffic also risks carrying hitchhiking invasive species into the Southern Ocean’s vulnerable marine ecosystems.

That’s to say nothing of greenhouse gas emissions. Because of the continent’s remoteness, tourists visiting Antarctica have a higher per capita carbon footprint than other cruise-ship travellers.

Of course, these impacts aren’t limited to tourism. Scientific expeditions come with similar environmental costs – and while there are far fewer of them, scientists and support personnel spend far more time on the continent.

Antarctic tourism isn’t going away – so we have to plan for the future

Are sustainable cruises an oxymoron? Many believe so .

Through its sheer size, the cruise industry has created mass tourism in new places and overtourism in others, generating unacceptable levels of crowding, disrupting the lives of residents, repurposing local cultures for “exotic” performances, damaging the environment and adding to emissions from fossil fuels.

In Antarctica, crowding, environmental impact and emissions are the most pressing issues. While 100,000 tourists a year is tiny by global tourism standards – Paris had almost 20 million in 2019 – visits are concentrated in highly sensitive ecological areas for only a few months per year. There are no residents to disturb (other than local wildlife), but by the same token, there’s no host community to protest if visitor numbers get too high.

Even so, strong protections are in place. In accordance with the Antarctic Treaty System – the set of international agreements signed by countries with an Antarctic presence or an interest – tourism operators based in those nations have to apply for permits and follow stringent environmental regulations .

To avoid introducing new species, tourists have to follow rules such as disinfecting their boots and vacuuming their pockets before setting foot on the ice, and keeping a set distance from wildlife.

Almost all Antarctic cruise owners belong to the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators, the peak body that manages Antarctic tourism.

For the first time this year, operators have to report their overall fuel consumption as part of IAATO’s efforts to make the industry more climate-friendly. Some operators are now using hybrid vessels that can run partly on electric propulsion for short periods, reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

Returning from the ice: the ambassador effect

Famed travel writer Pico Iyer recently wrote of his experience in the deep south of the world. The visit, he said, “awakens you to the environmental concerns of the world … you go home with important questions for your conscience as well as radiant memories”.

Iyer isn’t alone. This response is widespread, known in the industry as Antarctic ambassadorship . As you’d expect, this is strongly promoted by tourism operators as a positive.

Is it real? That’s contentious. Studies on links between polar travel and pro-environmental behaviour have yielded mixed results . We are working with two operators to examine the Antarctic tourist experience and consider what factors might feed into a long-lasting ambassador effect.

If you’re one of the tourists going to Antarctica this summer, enjoy the experience – but go with care. Be aware that no trip south comes without environmental cost and use this knowledge to make clear-eyed decisions about your activities both in Antarctica and once you’re safely back home.

Have you read?

Antarctica is now the best-mapped continent on earth, antarctica could reach its climate ‘tipping point’ this century – but we can stop it, the more we learn about antarctica, the greater the urgency to act on climate change, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Industries in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The energy transition could shift the global power centre. This expert explains why

Liam Coleman

June 4, 2024

Top 5 countries leading the sustainable tourism sector

Robot rock stars, pocket forests, and the battle for chips - Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy and Linda Lacina

April 29, 2024

Agritech: Shaping Agriculture in Emerging Economies, Today and Tomorrow

Confused about AI? Here are the podcasts you need on artificial intelligence

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Which technologies will enable a cleaner steel industry?

Daniel Boero Vargas and Mandy Chan

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Tourism in Antarctica: Edging Toward the (Risky) Mainstream

Travel to one of the most remote parts of the planet is booming. What does that mean for the environment and visitor safety?

By Paige McClanahan

In January, the Coral Princess, a ship with 2,000 berths and a crew of nearly 900, plowed through the frigid waters off the Antarctic Peninsula, cruising past icebergs, glaciers and mountains clad in snow. The cruise, which had been advertised at less than $4,000 per person, is remarkably cheaper than most Antarctic expeditions, which often charge guests at least three times that amount for the privilege of visiting one of the wildest parts of the planet. Visitors to the region — and the ships that carry them — are growing in number: Antarctica, once accessible only to well-funded explorers, is now edging toward the mainstream.

But managing tourism is a tricky issue in this distant region where no individual government has the power to set the rules, and the challenge is becoming more complex as Antarctica’s popularity grows. During the current austral summer, which runs from roughly November to March, visitor numbers to Antarctica are expected to rise by nearly 40 percent from the previous season. Some observers warn that such rapid growth risks imperiling visitor safety and adding pressure to this fragile region, which is already straining under the effects of climate change, commercial fishing for krill, toothfish and other species, and even scientific research.

Human activity in Antarctica falls under the governance of the Antarctic Treaty system, a model of international cooperation that dates to the Cold War era. But day-to-day management of tourism is regulated by the tour operators themselves, through a voluntary trade association that sets and enforces rules among its members. Observers agree that this system has worked well since it was set up in the 1990s, but some worry that booming tourist numbers could push the old system to a breaking point. They say that the consultative parties to the Antarctic Treaty system — governments like those of the United States, France, New Zealand, Argentina and some two dozen others — must act more quickly to manage tourism, and protect the region’s value as a wilderness.

“The bottom line for us is that there aren’t a lot of hard rules governing tourism. It’s mostly voluntary,” said Claire Christian, executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), a network of more than 15 conservation groups that serves as an observer to the Antarctic Treaty system. “Right now, there is a lot of good will. But that’s not something you can guarantee.”

A booming industry

Tourism in the Antarctic began with a trickle in the 1950s, but the industry remained exclusive and expensive. Expeditions grew steadily and by the late 1980s, a handful of companies were offering sea- and land-based trips. In 1991, seven private tour operators came together to form the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). Among other things, the group’s aims were to promote “environmentally safe and responsible travel”; improve collaboration among its members; and create — among the operators’ paying clients — a “corps of ambassadors” who could advocate conservation of the Antarctic region after they returned home from their trips.

Visitor figures soon began to creep up, increasing from roughly 6,700 in the 1992-1993 season to nearly 15,000 by the end of that decade, according to IAATO figures. Apart from a dip after the 2008 financial crisis, numbers have risen steadily ever since. More than 56,000 tourists visited Antarctica during the 2018-2019 season. The figure for the current season is expected to rise to more than 78,500, more than double the total from a decade ago. The vast majority of visitors come by cruise ship, setting sail from ports like Ushuaia in Argentina or Punta Arenas in Chile.

Meanwhile, IAATO has been gaining an average of two to five operators every year, according to Lisa Kelley, IAATO’s head of operations. Its members now include 48 tour operators, as well as five provisional members (Princess Cruises among them) and more than 60 associates — travel agents, marketers and others that work in the industry but don’t run their own tours.

“At the end of the day, we’re all a bunch of competitors,” said Bob Simpson, vice president of expedition cruising at the luxury travel company Abercrombie & Kent and a former chair of IAATO’s executive committee. “But it’s in our best interest to work together and cooperate,” he added, “to ensure this extraordinary place is protected for future generations.”

Mr. Simpson said that IAATO has been “remarkably successful” in promoting sustainable travel to the region, noting that, in his view, the education and experiences that they offer their guests outweigh the negative impact of the carbon emissions associated with the trip.

Abercrombie & Kent and other IAATO members agree to abide by the organization’s bylaws and guidelines, as well as the rules set out by the Antarctic Treaty system. These govern things like the number of passengers allowed ashore during site visits, staff-to-visitor ratios, and the amount of experience required of the crew.

The rules also stipulate that vessels — like the Coral Princess — that carry more than 500 people are not allowed to make landings; they can only “cruise” off the coast. Smaller vessel expeditions — offered by companies such as Abercrombie & Kent, Hurtigruten and Lindblad Expeditions, among others — are allowed to make landings, and their passengers might have the opportunity to disembark with guides to walk, kayak, snowshoe, or even camp or ski onshore.

Membership in IAATO remains voluntary, although all Antarctic tour operators must obtain a permit to travel in Antarctica from one of the parties to the Antarctic Treaty. For now, Ms. Kelley said, every passenger ship operating in the Antarctic is either a member or provisional member of IAATO, apart from some private yachts, defined as vessels carrying 12 or fewer passengers. She is confident that the organization is ready to accommodate the surge in tourist numbers.

“We’ve learned our lesson from the previous two big spurts of growth,” Ms. Kelley said in a recent phone interview. “We’ve really looked at our systems carefully and really worked on trying to make them as robust as we possibly can.”

Safety concerns

Other observers are less confident that rising tourist numbers are sustainable. The risks range from possible damage to sites that tourists visit to the potential growth in non-IAATO tour operators to ensuring visitor safety.

Accidents are rare, but not unheard-of. In November 2007, the MS Explorer, a Liberian-flagged vessel carrying about 100 passengers and 50 crew, cracked its hull on submerged ice, then started to take on water and list severely. Those aboard evacuated to lifeboats around 2:30 a.m., then floated in the cold for more than three hours before another ship, the cruise liner Nordnorge, rescued them. No one was killed or injured, but that was in part because of the weather.

“Within two hours after the passengers and crew were aboard the Nordnorge, the weather conditions deteriorated with gale force winds,” according to the official investigative report into the incident, which was conducted by the Liberian Bureau of Maritime Affairs. “If the Nordnorge’s speed to the scene had been reduced due to rough sea conditions, there may have been fatalities from hypothermia.”

The environment didn’t fare as well. The MS Explorer slipped beneath the waves carrying more than 55,000 gallons of oil, lubricant and petrol; two days later, an oil slick spread over an area of nearly two square miles near the site of the wreck. A Chilean naval ship passed through to try to speed up the dispersal of the fuel, but the report noted that the “oil sheen” was still visible more than a year later.

Ms. Kelley said that measures have been introduced since the Explorer incident, including the International Maritime Organization’s new “ polar code ,” which, she said, imposes “real limits on where and how vessels can operate and how new ships should be built.” Fuel tanks must now be situated away from the vessel’s hull, for example; navigation officers are required to have more experience and environmental rules have been tightened.

But as visitor numbers grow, so, too, does the risk of an accident. And while all tour operators in the Antarctic are currently IAATO members or provisional members, a status that offers them a degree of support, there is no guarantee that companies new to the region will see the value in joining the organization. If they decide to go it alone, there is nothing to stop them.

“There have been incidents, but we have always been quite lucky in the sense that maybe the weather conditions were right or there were other ships around,” said Machiel Lamers, an associate professor at the Environmental Policy Group of Wageningen University in the Netherlands. “Having a couple of thousands of passengers and crew in Antarctic waters is, of course, another thing than having a couple of hundred.”

A fragile environment

Scientists warn that the rise in tourism also increases the risk of disrupting the fragile environment. The introduction of invasive species — nonnative crabs or mussels clinging to the hull of a ship, foreign plant seeds stuck in the lining of a tourist’s parka — remains an important and ever-present threat . There is also evidence that populations of penguins and other wildlife have been disturbed by human activity in some areas. At the popular Hannah Point, there have been two reported instances of elephant seals falling off a cliff because of visitor disturbance. At other sites , historic structures have been marred by graffiti.

The Antarctic Treaty parties have drawn up “ site visitor guidelines ” for 42 of the most popular landing sites; these govern things like where ships are allowed to land, where visitors are allowed to walk, and how many landings are allowed per day. But the IAATO website lists more than 100 landing sites on the Antarctic Peninsula. Those with no guidelines in place may become more popular as tour operators try to avoid the crowds.

Pollution from ships is another concern. Although the International Maritime Organization’s polar code introduced new measures to control pollution, it still allows ships to dump raw sewage into the ocean if they are more than 12 nautical miles, roughly 13.8 miles, away from the nearest ice shelf or “fast ice” — stationary sea ice attached to the continent or grounded icebergs. It also fails to regulate discharges of “graywater,” runoff from ships’ sinks, showers and laundries that has been shown to contain high levels of fecal coliform as well as other pathogens and pollutants. Concerns about pollution are perhaps all the more worrying given the arrival of Princess Cruise Lines, which — alongside its parent company, Carnival Corporation — has been heavily fined for committing serious environmental crimes in other parts of the world.

A spokeswoman for Princess Cruises stressed in an email that the company is “committed to environmental practices that set a high standard for excellence and responsibility to help preserve the marine environment in Antarctica.” Negin Kamali, Princess Cruises’ director of public relations, added that the company meets or exceeds all regulatory requirements for Antarctica.

Fuel pollution, especially carbon emissions — is another concern, although there have been some positive steps. In 2011, the use of heavy fuel oil in the Antarctic was banned under the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). Today, ships in the region generally use less-polluting marine diesel, although some — like the MS Roald Amundsen , run by the Norwegian company Hurtigruten — have gone a step further, supplementing their traditional fuel with battery power. Princess Cruises is currently testing similar technologies, said Ms. Kamali.

In the background, warmer temperatures are making the entire continent more vulnerable to external threats.

“It’s important to understand that all of these impacts — climate change, fishing, tourism — are cumulative,” Cassandra Brooks, an assistant professor in environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, wrote in an email. “Given the sheer carbon footprint of Antarctic tourism, and the rapid growth in the industry, these operations will become increasingly difficult to justify.”

The way forward

Antarctic Treaty parties are aware that tourism growth will require a new approach. But it’s not clear what steps they will take, nor how quickly they will act. And reaching consensus — which is what decision-making within the Antarctic Treaty system requires — can be a slow and arduous process.

In April 2019, the government of the Netherlands hosted an informal meeting to discuss how to manage Antarctic tourism. The participants — including representatives of 17 treaty parties, IAATO and ASOC, the civil society group, as well as other experts — identified “key concerns” related to the predicted growth in ship tourism: pressure on sites where tourists visit, the expansion of tourism to new areas, and the possible rise in tour operators who choose not to join IAATO, among other issues.

The group’s recommendations were presented to the Antarctic Treaty’s Committee for Environmental Protection as well as to the most recent annual meeting of the treaty parties in July. The discussions seemed to go in the right direction, said Ms. Christian, but they are still a long way from implementing major changes.

Stronger regulations could come in many forms, including a prohibition on potentially disruptive activities such as heli-skiing or jet-skiing, both of which are currently allowed; a general strengthening of the Antarctic Treaty system’s existing guidelines for visitors , which already instruct people not to litter, take away souvenirs, or get too close to wildlife, among other things. Parties to the Antarctic Treaty system could also establish protected areas that could be made off limits to tourist vessels, or agree to enact domestic laws to enable authorities to prosecute visitors for Antarctic misbehavior (penguin cuddling, for instance) after they return home.

Or the treaty parties could go even further: They could require all passenger vessels to obtain IAATO membership before being granted a permit, or set a cap on the total number of visitors allowed each season. Most observers agree that both steps would be politically very difficult to enact, mainly because treaty parties have diverging views of what Antarctic tourism should look like.

Tour operators and some academics maintain that tourism in Antarctica is vital because it creates awareness and builds a network of people who will go home to fight for stronger protections in the region. but — as with scientific research, or any human activity in Antarctica — the risks and potential negative impacts of tourism must be weighed against its benefits.

Whatever policy steps might be on the table, self-regulation in the tourism industry is no longer sufficient, said Ms. Brooks, who adds that Antarctica is already straining under its many pressures.

“IAATO is truly amazing in what they have accomplished, but it’s difficult to imagine how they will manage to control this burgeoning industry,” she wrote in an email. “It’s equally difficult to imagine how more than 78,000 people visiting Antarctica as tourists won’t have a negative impact on the region.”

52 PLACES AND MUCH, MUCH MORE Discover the best places to go in 2020, and find more Travel coverage by following us on Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our Travel Dispatch newsletter : Each week you’ll receive tips on traveling smarter, stories on hot destinations and access to photos from all over the world.

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Dipping Their Toes: Younger generations of travelers are venturing onto ships for the first time . Many are saving money.

Cult Cruisers: These devoted cruise fanatics, most of them retirees, have one main goal: to almost never touch dry land .

Invest in news coverage you can trust.

Donate to PBS NewsHour by June 30 !

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

How antarctica’s tourist boom could affect earth’s ‘last great wilderness’.

William Brangham William Brangham

Emily Carpeaux Emily Carpeaux

Mike Fritz Mike Fritz

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-antarcticas-tourist-boom-could-affect-earths-last-great-wilderness

Watch Part 4

Can Antarctica remain a refuge for science and peace?

Antarctica was the last of the seven continents to be discovered, and it wasn’t until the late 1950s that commercial tourism began there. But now, Antarctica has become a popular travel destination, amid growing concerns about the effect that increasing numbers of people could have on its pristine environment. William Brangham reports from Antarctica.

Read the Full Transcript

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

Judy Woodruff:

Now to our continuing series Warnings From Antarctica.

It was the last of the seven continents to be discovered, and it wasn't until the late 1950s that commercial tourism to the region began. But now it's becoming a popular destination.

William Brangham and producers Mike Fritz and Emily Carpeaux traveled there and have this report on how tourism has thus far shown little impact on Antarctica's pristine environment, but why there is growing concern about the influx of more and more people.

William Brangham:

Welcome to the tourist boom at the bottom of the world. It's a front-row seat to a remarkable show, majestic humpback whales, frolicking fur seals, an army of curious, charming penguins.

All that framed by a backdrop that defies description, nothing but miles of mountains, glaciers and icebergs as far a the eye can see. The icy continent of Antarctica is hot. A record 50,000 people came last year. "GQ" magazine recently said now is the time to go. The New York Times said, forget Times Square. Ring in the new year right here.

David McGonigal:

The main attraction of the area is just, it's a place where people are irrelevant. People just don't count. You're coming here purely as a visitor. You have no other impact.

David McGonigal has led over 120 trips to Antarctica for One Ocean Expeditions, a Canadian tour company promoting environmentally conscious travel.

These are trips where the scenery comes with equal helpings of science and history. This is definitely not budget travel. It's about $12,000 to $20,000 per person for this two-week cruise. That includes kayaking, hiking, and motorboat excursions by day, white tablecloth meals, and lectures from scientists and naturalists by night.

McGonigal's job is to keep the roughly 140 passengers, who have come from around the world, safe and satisfied.

Some people are just down here for the history, and so you have got to find some historical elements to deliver. Some people just want wildlife. Some people are really just down here for the ice. And it's a matter of juggling that all around and then trying to pull together a plan.

The journey starts at the southern tip of South America, and through the infamous Drake Passage, home to some of the roughest seas known to man.

Two days later, the ship finally crosses the Antarctic Circle, one of the southernmost latitudes on Earth.

Hermione Roff:

This sort of place, it deepens your understanding of the world, but also of yourself.

Hermione and Jon Roff made the trip from Northern England. She's a child and family therapist. He's an Anglican priest.

We wanted to come and see it before either it disappeared or we disappeared.

We are probably spending more on this holiday than we have spent on our holidays in our entire lives.

Is that right?

Yes, I think so.

Yusuf Hashim retired almost 20 years ago. He was a marketing director for Shell Oil in Malaysia. He convinced nearly 50 of his friends and family to join him on this trip.

So, what are you doing here on the bottom of the Earth?

Yusuf Hashim:

Spending my children's inheritance.

Do they know that this is what is happening?

Yes, that's one of them over there. So it's bonding time. I have been here four times now, and I will never tire of looking at icebergs and penguins and the scenery. It makes it all worth living.

In addition to all the wildlife, the ship visits historic sites, like this abandoned British scientific base from the 1950s, as well as active bases. Eleven scientists from Ukraine work and live here year-round.

And the tourists can sample the homemade whisky made with glacial ice at one of the southernmost drinking holes in the world. But visiting Antarctica until relatively recently was a trip no human had ever made.

Katie Murray:

It's absolutely incredible that our seventh continent, our newest continent, was discovered less than 200 years ago, changing what we understand about the globe today.

Katie Murray is a polar historian who works for One Ocean, teaching visitors about the earliest Antarctic explorers, like Britain's James Cook, or the ill-fated race to the South Pole in 1911 between Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen, or perhaps the most famous Antarctic adventure story, Ernest Shackleton's dramatic endurance voyage several years later.

We talked with Murray in the ship's movie theater.

It's quite incredible, actually, that 100 years after the Heroic Age, just over 100 years since Scott and the polar party died on their return from the South Pole, and you have got these great stories of endurance and suffering, we can now come to Antarctica effectively for fun.

This record number of tourists coming here has been growing steadily since the 1980s, when just a few thousand made the trip every year.

And when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Soviet fleet of ice-strengthened vessels became available, and people realized they could actually charter those and bring those down. That was what started the whole rush in the 1990s.

Today, more and more tour companies are rolling out new fleets of luxury ice-strengthened ships capable of navigating the icy waters here. But the arrival of more and more visitors to Antarctica is also leading to concerns about their impact on this pristine ecosystem.

Claire Christian:

Antarctica is really the world's last great wilderness. There's no permanent human population there.

It's a continent that is for nature, and I think that's a really important symbol, because so many other places where human civilization has spread to, we have destroyed the environment.

Claire Christian is the executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. She believes tourism has so far been a force for good, galvanizing people to care about a continent that is thousands of miles from their homes.

Right now, tourists only visit the Antarctic Peninsula, because it's the most accessible and most scenic part of the continent, but Christian notes this is also a region stressed by climate change. So, how many more visitors can the region handle?

Right now, there may not — it may not be able to — we may not be able to see a lot of effects. But, if you suddenly have a sharp increase in the number of people who are visiting a small colony every day, that might start to have an impact.

Remember, Antarctica has no government. No nation runs this place. And, currently, all tour groups are governed by a strict, but voluntary set of regulations.

For example, only one ship at a time is allowed at designated sites. There are rules about how many people can go ashore and how close they can get to wildlife. One Ocean Expeditions mandates all tourists vacuum and clean their gear before going ashore, so that no foreign seeds or dirt end up on land. All returning gear gets a similar scrub every day.

But invasive species have already taken hold. This moss is from the Arctic. A trace amount somehow made the 12,000-mile trip. And there are also concerns about wildlife. Two of the three penguin species on the peninsula are in decline. Researchers believe it's being driven in part by a warming environment.

Given that, are all these humans an added stress? You see all that reddish brown material on the ground behind me? That's all penguin guano, or penguin poop. And not only does it make this whole area have a very unique aroma, but scientists have been measuring the stress hormones that are released into guano at places where tourists show up and at places where tourists never go.

And for the penguins so far, at least, it doesn't seem that the presence of tourism is causing them any problems.

Andrea Raya Rey is a conservation biologist based in Ushuaia, Argentina, a city where the bulk of all Antarctic tourism begins.

Raya Rey says that, while tourism is showing little impact thus far, she worries about the estimated 40 percent growth in the industry.

Andrea Raya Rey:

The tourism puts an extra pressure on the ecosystem. One ship, it's OK, two, OK, three. But 10 at the same time pointing at them, it's stressful.

It's also a concern shared by those within the tourism industry.

It's going to be more a matter of just, how do you manage the numbers when there's just nowhere left to go and you have got more ships coming down?

As for visitors like Jon and Hermione Roff, they feel incredibly lucky to have seen the wonders of Antarctica up close. But they admit that they are worried about their own impact.

There is a growth of tourism that does leave a mark. However careful we are, it leaves a mark. And so it's a very difficult balance. I mean, I'm really thrilled that we have come, but I hope not too many more people will come.

For now, though, there is no sign that this tourist boom is slowing.

For the "PBS NewsHour," I'm William Brangham on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Listen to this Segment

Watch the Full Episode

William Brangham is an award-winning correspondent, producer, and substitute anchor for the PBS NewsHour.

Senior Producer, Field Segments

Mike Fritz is the deputy senior producer for field segments at PBS NewsHour.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Support PBS NewsHour:

More Ways to Watch

- PBS iPhone App

- PBS iPad App

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

The Last Place on Earth Any Tourist Should Go

Take Antarctica off your travel bucket list.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

On the southernmost continent, you can see enormous stretches of wind-sculpted ice that seem carved from marble, and others that are smooth and green as emerald. You can see icebergs, whales, emperor penguins. Visitors have described the place as otherworldly, magical, and majestic. The light, Jon Krakauer has said, is so ravishing, “you get drugged by it.”

Travelers are drawn to Antarctica for what they can find there—the wildlife, the scenery, the sense of adventure—and for what they can’t: cars, buildings, cell towers. They talk about the overwhelming silence. The Norwegian explorer Erling Kagge called it “the quietest place I have ever been.” All of these attractions are getting harder to find in the rest of the world. They’re disappearing in Antarctica too. The continent is melting; whole chunks are prematurely tumbling into the ocean. And more people than ever are in Antarctica because tourism is on a tear.

Four decades ago, the continent saw only a few hundred visitors each summer. More than 100,000 people traveled there this past season, the majority arriving on cruises. In the context of a land this size, that number may not sound like a lot. It’s roughly the capacity of Michigan Stadium, or about the attendance of the CES tech conference back in January.

But it’s also a record—and a 40 percent jump over 2019–20, the season before the coronavirus pandemic brought Antarctic travel to a near standstill. And although scientists who visit the continent to study its life and demise have a clear place here, many sightseers bring a whiff of “last-chance tourism”—a desire to see a place before it’s gone, even if that means helping hasten its disappearance. Perversely, the climate change that imperils Antarctica is making the continent easier to visit; melting sea ice has extended the cruising season. Travel companies are scrambling to add capacity. Cruise lines have launched several new ships over the past couple of years. Silversea’s ultra-luxurious Silver Endeavour is being used for “fast-track” trips—time-crunched travelers can save a few days by flying directly to Antarctica in business class.

Overtourism isn’t a new story. But Antarctica, designated as a global commons, is different from any other place on Earth. It’s less like a too-crowded national park and more like the moon, or the geographical equivalent of an uncontacted people. It is singular, and in its relative wildness and silence, it is the last of its kind. And because Antarctica is different, we should treat it differently: Let the last relatively untouched landscape stay that way.

Traveling to Antarctica is a carbon-intensive activity. Flights and cruises must cross thousands of miles in extreme conditions, contributing to the climate change that is causing ice loss and threatening whales, seals, and penguins. By one estimate, the carbon footprint for a person’s Antarctic cruise can be roughly equivalent to the average European’s output for a year, because cruise ships are heavy polluters and tourists have to fly so far. Almost all travel presents this problem on some level. But “this kind of tourism involves a larger carbon footprint than other kinds of tourism,” says Yu-Fai Leung, a professor in the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University who has done extensive research on Antarctic travel.

Antarctic tourism also directly imperils an already fragile ecosystem. Soot deposits from ship engines accelerate snow melting. Hikes can damage flora that take well over a decade to regrow in the harsh environment. Humans risk introducing disease and invasive species. Their very presence, North Carolina State scientists have shown, stresses out penguins, and could affect the animals’ breeding. Yet as tourism gets more popular, companies are competing to offer high-contact experiences that are more exciting than gazing at glaciers from the deck of a ship. Last year, for instance, a company named White Desert opened its latest luxury camp in Antarctica. Its sleeping domes, roughly 60 miles from the coast, are perched near an emperor-penguin colony and can be reached only by private jet. Guests, who pay at least $65,000 a stay, are encouraged to explore the continent by plane, Ski-Doos, and Arctic truck before enjoying a gourmet meal whose ingredients are flown in from South Africa.

All of this adds up. A recent study found that less than a third of the continent is still “pristine,” with no record of any human visitation. Those untouched areas don’t include Antarctica’s most biodiverse areas; like wildlife—and often because of wildlife—people prefer to gather in places that aren’t coated in ice. As more tourists arrive, going deeper into the continent to avoid other tourists and engage in a wider range of activities, those virgin areas will inevitably shrink.

The international community has banned mining on the continent, and ships aren’t allowed to use heavy fuel oil in its waters. Yet tourism is still only loosely regulated. “I think it’s fair to say the rules are just not good enough,” Tim Stephens, a professor at the University of Sydney who specializes in international law, told me. There’s no single central source of governance for tourism. The Antarctic Treaty System imposes broad environmental restrictions on the continent. Individual governments have varying laws that regulate operators, ships, and aircraft. The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators has extensive guidelines it requires its members to follow, out of genuine concern and, perhaps, to ward off more rigorous outside regulation.

Gina Greer, IAATO’s executive director, says the organization is proactive about protecting Antarctica. Visitors are asked to keep a distance from wildlife, decontaminate their shoes to keep novel bugs and bacteria at bay, stay on established paths, and more. Because tour operators visit the same sites repeatedly, they can spot changes in the landscape or wildlife populations and notify scientists.

This spring, IAATO added a new slow zone—an area where ships have to reduce their speed to 10 knots because whales have been congregating there in greater numbers—to those implemented in 2019. “It’s amazing to see how members come together and make decisions that may be difficult but are necessary,” Greer told me.

Still, these are all essentially voluntary behaviors. And some operators don’t belong to IAATO.

Accidents also have a way of happening despite the best intentions. In 2007, the MS Explorer, a 250-foot expedition cruise ship, sank near penguin breeding grounds on the South Shetland Islands, leaving behind a wreck and a mile-long oil slick. Most cruise ships are registered in what Stephens calls “flag-convenient countries” that are lax on oversight. “If you have a cruise ship going down in Antarctica, it’s not going to be the same seriousness as the Exxon Valdez,” he said. “But it’s not going to be pretty.”

To reduce crowding and environmental pressure, modern-day tourists have been asked to think twice about visiting a slew of alluring places: Venice, Bali, Big Sur. But the calculus can get complicated—in almost any destination, you have locals who are trying to improve (or just sustain) their lot.

Most of the Maldives, for instance, lies just a meter above sea level. “Climate change is an existential threat,” Aminath Shauna, the minister of environment, climate change, and technology, said in an interview with the IMF in 2021. “There’s no higher ground we can run to.”

Within decades, the decadent overwater bungalows that the islands are known for could be underwater bungalows. But more than a quarter of the country’s GDP comes from tourism. So this year, the Maldives hopes to welcome 1.8 million tourists—all of whom can reach it only by plane or boat rides that indirectly contribute to rising seas.

That conflict doesn’t exist in Antarctica. With no human residents, it’s the rare place that still belongs to nature, as much as that’s possible. It is actually most valuable to us when left wild, so that it can continue to act as a buffer against climate change, a storehouse of the world’s fresh water, and a refuge for birds, whales, seals, fish, and even the krill that the entire marine ecosystem depends on.

Some argue that tourists become ambassadors for the continent—that is, for its protection and for environmental change. That’s laudable, but unsupported by research, which has shown that in many cases Antarctic tourists become ambassadors for more tourism.

Antarctica doesn’t need ambassadors; it needs guardians. Putting this land off-limits would signify how fragile and important—almost sacred—it is. Putting it at risk to give deep-pocketed tourists a sense of awe is simply not worth it.

We have more than a continent—or even our planet—at stake. The treaties that govern Antarctica helped lay the foundation for space agreements. Space is already crowded and junked up with human-made debris. Tourism will only add to the problem; experts are warning that it is intensely polluting and could deplete the ozone layer. If we can’t jointly act to put Antarctica off limits, our view of the moon may eventually be marred. Imagine a SpaceX–branded glamping resort, or a Blue Origin oasis stocked entirely by Amazon’s space-delivery business.

As a species, we’re not very good at self-restraint (see: AI). And these days, few arenas exist where individual decisions make a difference. Antarctica could be one of them. Maybe, despite our deepest impulses to explore, we can leave one place in the world alone.

This story is part of the Atlantic Planet series supported by HHMI’s Science and Educational Media Group.

What is the impact of tourism on Antarctica? Four new projects will investigate

- July 15, 2022

by Emma Meehan

The Dutch Research Council (NWO) has launched four projects to research the impact of tourism on Antarctica. The research programme is the first to focus on how tourism impacts the continent, and the findings will support policy development.

The four projects will investigate:

- Decision-making tools for stakeholders on Antarctica’s tourism future

- Incorporating environmental stewardship by tour operators, organisations, and governments

- Understanding the factors that influence tourists becoming ambassadors

- Developing knowledge and tools to minimise the cumulative impacts on biodiversity and wilderness values.

The projects will run from 2022 until 2027.

NWO selects and funds research proposals that have scientific and societal impacts. Through its Dutch Research Agenda’s (NWA) polar programme, a budget of 4 million euros is available in the programme’s first phase.

Protecting Antarctica’s fragile environment

Tourism in Antarctica has been increasing over the past 30 years. As the NWO notes, ships are getting bigger, traveling farther and more frequently, and tourism operators are offering a growing range of activities.

The projects will look at how tourism impacts Antarctica and how it can be carried out in an environmentally and nature-friendly way.

International collaboration is vital for polar research

Researchers from the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, the U.S, Canada, and the U.K, are working on the projects.

In addition to international universities, collaborating partners include:

- British Antarctic Survey , a permanent NWO partner in Antarctica research

- International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators ( IAATO )

- Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research ( SCAR )

- Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition ( ASOC )

- Oceanwide Expeditions , polar expedition company, and LT&C corporate member.

The research projects will support national and international policy development, with the aim to protect the values of the Antarctic Treaty.

LT&C-Example – Completing a ring of Marine Protected Areas around Antarctica

In the LT&C-Example , tourists and tour operators are key players in encouraging decision-makers to complete a network of marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

If these MPAs are created, ASOC points out that 4 million km2 of the ocean would be protected, representing the largest act of ocean protection in history.

This would be a significant achievement and milestone for the 30×30 campaign to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030.

Study Tours & Events:

11th red rocks cultural festival 2023, replicating successful examples of linking tourism and conservation in africa: lt&c’s session at the business of conservation conference, canoeing the great canadian shield – temagami ontario, canada, latest news:, lt&c study tour 2024: “east spitsbergen and bear island”.

To study the LT&C Example “Svalbard”, our founding member and Partner, Oceanwide Expeditions, offers our members a discount on the East Spitsbergen and Bear Island tour in July, 2024.

Less than a year after the “East Atlantic Flyway Week” in April 2023 – exciting book published in German and English

In April 2023, experts from nine countries met on Hallig

Season’s Greetings from Ö.T.E.-LT&C

As we look back on 2023, we continue to be inspired by the dedicated work you are leading in natural areas around the world, advancing sustainable tourism practices in many different ways.

Become a member

Subscribe to newsletter, corporate members:.

© Linking Tourism & Conservation (LT&C) 2019

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy | Sitemap | Admin Login

Make a donation

We are grateful that you support the work and mission of LT&C! We accept donations through Credit Card, PayPal or international bank transfer:

Alternative 1: Donate through Credit Card:

Donate through Credit Card

Alternative 2: Donate through PayPal (amount in Euro):

Please click the Donate button and then choose your PayPal account

Donate via Paypal

Alternative 3: Donate through international bank transfer

Bank details: Cultura Sparebank Pb. 6800, St. Olavs plass N-0130 Oslo

Name: Linking Tourism & Conservation, Account no.: 1254 05 95168 IBAN: NO8712540595168 BIC/SWIFT: CULTNOK1 Routing BIC: DNBANOKK

Please mark payments with your name and/or email address

Sign up now

Sign up for an LT&C membership by filling in the details below.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

Add your lt&c-example.

Would you like your LT&C-Example/Initiative to be listed on our website? Please fill in the form below.

- Would you like your LT&C example/initiative to be listed on our website? Please fill in the form below.

- Name of LT&C example/initiative *

- Short description of LT&C example/initiative

- Please tell us about your LT&C example/initiative and how it fits with Linking Tourism & Conservation (LT&C)

- 1. Why is this case a good example of linking tourism and conservation? Please elaborate on the following topics: a) Political/management support b) Financial support c) Educational support

- 2. Are there plans to further improve this example of tourism supporting conservation in the future?

- 3. How could this example be transferred to another protected area and knowledge be shared?

- 4. How did the Example cope with the pandemic and is prepared for future crises?

- Project website Website with more information on the LT&C example/initiative

- Please leave your contact details so that we can get in touch with you. This information will not be displayed on our website unless you ask us to.

- Name of contact person First Last

- Email of contact person

- Phone of contact person

- I accept LT&C privacy policy

- I accept that LT&C may use this submitted material on the LT&C website (credits or links will be provided)

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

What are the real environmental impacts of Antarctic tourism? Unveiling their importance through a comprehensive meta-analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Grupo de Investigación ECOPOLAR - Biología y Ecología en Ambientes Polares, Departamento de Ecología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, C/Darwin 2, E-28049, Madrid, Spain. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Grupo de Investigación ECOPOLAR - Biología y Ecología en Ambientes Polares, Departamento de Ecología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, C/Darwin 2, E-28049, Madrid, Spain. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Grupo de Investigación ECOPOLAR - Biología y Ecología en Ambientes Polares, Departamento de Ecología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, C/Darwin 2, E-28049, Madrid, Spain; Instituto de Ecología Aplicada ECOLAP-USFQ, Universidad de San Francisco de Quito, P.O. Box 1712841, Diego de Robles y Pampite, Cumbayá, Ecuador. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism Management and Center for Geospatial Analytics, North Carolina State University, 5107 Jordan Hall, Raleigh, NC, 27695, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 Laboratorio de Estudios Métricos de la Información (LEMI), Departamento de Biblioteconomía y Documentación, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, E-28903, Getafe, Spain; Research Institute for Higher Education and Science (INAECU) (UAM-UC3M), E-28903, Getafe, Spain. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Gateway Antarctica, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, 8140, New Zealand. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 35151103

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114634

Human activities in Antarctica were increasing before the COVID-19 pandemic, and tourism was not an exception. The growth and diversification of Antarctic tourism over the last few decades have been extensively studied. However, environmental impacts associated with this activity have received less attention despite an increasing body of scholarship examining environmental issues related to Antarctic tourism. Aside from raising important research questions, the potential negative effects of tourist visits in Antarctica are also an issue discussed by Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties. This study presents the results of a meta-analysis of scholarly publications that synthesizes and updates our current knowledge of environmental impacts resulting from Antarctic tourism. A first publication database containing 233 records that focussed on this topic was compiled and subjected to a general bibliometric and content analysis. Further, an in-depth content analysis was performed on a subset of 75 records, which were focussed on showing specific research on Antarctic tourism impacts. The main topic, methods, management proposals, and research gaps highlighted by the respective authors of these 75 publications were assessed. The range of research topics addressed, the methods used - including the application of established research designs from the field of environmental impact assessment -, and the conclusions reached by the study authors are discussed. Interestingly, almost one third of the studies did not detect a direct relationship between tourism and significant negative effects on the environment. Cumulative impacts of tourism have received little attention, and long-term and comprehensive monitoring programs have been discussed only rarely, leading us to assume that such long-term programs are scarce. More importantly, connections between research and policy or management do not always exist. This analysis highlights the need for a comprehensive strategy to investigate and monitor the environmental impacts of tourism in Antarctica. A first specific research and monitoring programme to stimulate a debate among members of the Antarctic scientific and policy communities is proposed, with the ultimate goal of advancing the regulation and management of Antarctic tourism collaboratively.

Keywords: Adaptive Management; Bibliometric analysis; Cumulative impacts; Monitoring; Natural protected areas; Strategic conservation.

Copyright © 2022 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Meta-Analysis

- Antarctic Regions

- Anthropogenic Effects*

- Environment

Human impacts in Antarctica

We often think of Antarctica as a pristine land untouched by humans, but this is no longer the case.

For a little over 100 years, people have been travelling to Antarctica. In that short time, most parts have been visited and we have left more than just footprints.

Human impacts include:

- harvesting some Antarctic species to the verge of extinction for economic benefit

- killing and disturbing other species

- contaminating the soils

- discharging sewage to the sea

- leaving rubbish, cairns and tracks.

Changing attitudes

There are few unvisited places left on Earth. We have started to realise their enormous value to humanity. The clean air, water and ice of Antarctica are now of global importance to science. They help us understand how the Earth’s environment is changing – both naturally and because of human activity. Tourist operators have tapped into a huge demand to visit the last great wilderness on Earth.

We have also realised that visiting Antarctica can have an environmental impact. Science and tourism both have the potential to damage the very qualities that draws them to Antarctica.

Scales of environmental impacts in Antarctica

Environmental impacts in Antarctica occur at a range of scales. Global warming, ozone depletion and global contamination have planet-wide impacts. These affect Antarctica at the largest scale.

Fishing and hunting have more localised impacts, but still have the potential to cause region-wide effects. Visitors, such as scientists and tourists, have even more localised impacts on the region.

Global impacts show in Antarctica

The Antarctic region is a sensitive indicator of global change. The polar ice cap holds within it a record of past atmospheres that go back hundreds of thousands of years. This record allows us to study the earth’s natural climate cycles. The significance of recent changes in climate can be judged against this record.

Impacts of hunting and fishing

Hunting for whales and seals drew people to the Antarctic in the early years of the 19th century. Within only a few decades, these activities caused major crashes in wildlife populations.

The Antarctic fur seal was at the verge of extinction at many locations by 1830. The seal populations of Macquarie Island have been protected since 1933, by the island’s status as a wildlife sanctuary. The seals of Australia’s sub-Antarctic islands were further protected in 1997 when both Macquarie and the Heard and McDonald Islands were added to the World Heritage list. Exploited seal populations of the Southern Ocean have recovered substantially. They are no longer endangered.

Whaling in the Southern Ocean began in earnest in the early 1900s and grew very quickly. By 1910, the Southern Ocean provided 50% of the world’s catch. The history of whaling is a repeated cycle. Whalers targeted the most profitable species, depleted stocks to unviable commercial levels and then moved on to another species.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) first met in 1949. Blue and humpback whales became fully protected in the 1960s. Protection was extended to fin and sei whales in the 1970s. In 1986 the IWC decided to suspend all commercial whaling. Since that moratorium, whaling has been limited to a handful of nations that harvest whales under the ‘scientific whaling’ provisions. There are indications that whale populations are beginning to recover.

Fishing is the only large-scale commercial resource currently harvested in the Antarctic Treaty area. Major fisheries world-wide have faced over-exploitation. Unless the controls established for Antarctic fisheries are enforced, the Southern Ocean will face the same over-exploitation.

The major negative effects of fisheries are:

- potential for over-fishing of target species

- effects on predator populations dependant on the target species as a food source

- mortality of non-target species caught by fishing equipment

- destruction of habitat.

The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) manages living marine resources in the convention area.

Long-line fishing is a particular risk to albatrosses. CCAMLR has introduced a Conservation Measure to reduce the incidence of seabird mortality during long-lining. The Australian Fisheries Management Authority limits the fishery around Heard and Macquarie Islands to trawling to minimise the impacts on seabirds.

The Australian Antarctic Division has established the Antarctic Marine Living Resources program to provide the scientific basis for ecologically sustainable management of Southern Ocean fisheries.

Introduced species

Biosecurity is an important part of managing the Antarctic environment. The risk of introducing species, including disease-causing species, is of particular concern in Antarctica. Introduced species have caused major environmental problems on every other continent of the world. They have caused significant changes to the ecology of most sub-Antarctic islands.

Australia hosted the first international meeting to consider disease in Antarctic wildlife. Strict biosecurity measures reduce the risk of introduction and spread of diseases to Antarctic wildlife.

Undoing past damage

Environmental management aims to ameliorate past environmental impacts and reduce current and future impacts.

The Australian Antarctic Program is developing procedures for the clean up and remediation of abandoned work sites and disused tip sites. In the early days, waste management included using open tips and pushing waste onto the sea ice.

Commitment to the Madrid Protocol confers the obligation to clean-up abandoned work sites and waste tips so long as the process of clean-up does not cause greater adverse impacts or cause the removal of historic sites or monuments.

Australian scientists are developing new clean up and remediation procedures that will not cause greater impacts.

Photo gallery

- Firstpost Defence Summit

- Entertainment

- Web Stories

- Health Supplement

- First Sports

- Fast and Factual

- Between The Lines

- Firstpost America

Tourism to Antarctica is back and booming: Is it dangerous for ice and its ecosystem?

More than 100,000 tourists are headed to Antarctica. As the number of tourists rise, so will environmental impacts such as black carbon from cruise ship funnels

)

As the summer sun finally arrives for people in the Southern Hemisphere, more than 100,000 tourists will head for the ice.

Travelling on one of more than 50 cruise ships, they will brave the two-day trip across the notoriously rough Drake Passage below Patagonia, destined for the polar continent of Antarctica.

During the COVID summer of 2020-21, just 15 tourists on two yachts visited Antarctica. But now, tourism is back — and bigger than ever. This season’s visitor numbers are up more than 40 per cent over the largest pre-pandemic year .

So, are all those tourists going to damage what is often considered the last untouched wilderness on the planet? Yes and no. The industry is well run. Tourists often return with a new appreciation for wild places. They spend a surprisingly short amount of time actually on the continent or its islands.

But as tourism grows, so will environmental impacts such as black carbon from cruise ship funnels. Tourists can carry in microbes, seed and other invasive species on their boots and clothes — a problem that will only worsen as ice melt creates new patches of bare earth. And cruise ships are hardly emissions misers.

How did Antarctic tourism go mainstream?

In the 1950s, the first tourists hitched rides on Chilean and Argentinian naval vessels heading south to resupply research bases on the South Shetland Islands.

From the late 1960s, dedicated icebreaker expedition ships were venturing even further south. In the early 1990s, as ex-Soviet icebreakers became available, the industry began to expand — about a dozen companies offered trips at that time.

By the turn of this century, the ice continent was receiving more than 10,000 annual visitors: Antarctic tourism had gone mainstream.

What does it look like today?

Most Antarctic tourists travel on small “expedition-style” vessels, usually heading for the relatively accessible Antarctic Peninsula. Once there, they can take a zodiac boat ride for a closer look at wildlife and icebergs or shore excursions to visit penguin or seal colonies. Visitors can kayak, paddle-board and take the polar plunge — a necessarily brief dip into subzero waters.

For most tourists, accommodation, food and other services are provided aboard ship. Over a third of all visitors never stand on the continent.

Those who do set foot on Antarctica normally make brief visits, rather than taking overnight stays.

For more intrepid tourists, a few operators offer overland journeys into the continent’s interior, making use of temporary seasonal camp sites. There are no permanent hotels, and Antarctic Treaty nations recently adopted a resolution against permanent tourist facilities.

As tourists come in increasing numbers, some operators have moved to offer ever more adventurous options such as mountaineering, heli-skiing, underwater trips in submersibles and scuba diving.

Is Antarctic tourism sustainable?

As Antarctic tourism booms, some advocacy organisations have warned the impact may be unsustainable. For instance, the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition argues cruise tourism could put increased pressure on an environment already under significant strain from climate change.

In areas visited most by tourists, the snow has a higher concentration of black carbon from ship exhaust, which soaks up more heat and leads to snow melt.

Ship traffic also risks carrying hitchhiking invasive species into the Southern Ocean’s vulnerable marine ecosystems.

That’s to say nothing of greenhouse gas emissions. Because of the continent’s remoteness, tourists visiting Antarctica have a higher per capita carbon footprint than other cruise-ship travellers.

Of course, these impacts aren’t limited to tourism. Scientific expeditions come with similar environmental costs — and while there are far fewer of them, scientists and support personnel spend far more time on the continent.

Antarctic tourism isn’t going away – so there is a need to plan for the future

Are sustainable cruises an oxymoron? Many believe so .

Through its sheer size, the cruise industry has created mass tourism in new places and overtourism in others, generating unacceptable levels of crowding, disrupting the lives of residents, repurposing local cultures for “exotic” performances, damaging the environment and adding to emissions from fossil fuels.

In Antarctica, crowding, environmental impact and emissions are the most pressing issues.

While 100,000 tourists a year is tiny by global tourism standards — Paris had almost 20 million in 2019 — visits are concentrated in highly sensitive ecological areas for only a few months per year.

There are no residents to disturb (other than local wildlife), but by the same token, there’s no host community to protest if visitor numbers get too high.

Even so, strong protections are in place. In accordance with the Antarctic Treaty System — the set of international agreements signed by countries with an Antarctic presence or an interest — tourism operators based in those nations have to apply for permits and follow stringent environmental regulations .

To avoid introducing new species, tourists have to follow rules such as disinfecting their boots and vacuuming their pockets before setting foot on the ice, and keeping a set distance from wildlife.

Almost all Antarctic cruise owners belong to the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators, the peak body that manages Antarctic tourism.

For the first time this year, operators have to report their overall fuel consumption as part of IAATO’s efforts to make the industry more climate-friendly. Some operators are now using hybrid vessels that can run partly on electric propulsion for short periods, reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

Returning from the ice: The ambassador effect

Famed travel writer Pico Iyer recently wrote of his experience in the deep south of the world. The visit, he said, “awakens you to the environmental concerns of the world … you go home with important questions for your conscience as well as radiant memories”.

Iyer isn’t alone. This response is widespread, known in the industry as Antarctic ambassadorship . As you’d expect, this is strongly promoted by tourism operators as a positive.

Is it real? That’s contentious. Studies on links between polar travel and pro-environmental behaviour have yielded mixed results .

Work is on with two operators to examine the Antarctic tourist experience and consider what factors might feed into a long-lasting ambassador effect.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Read all the Latest News , Trending News , Cricket News , Bollywood News , India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

Find us on YouTube

Related Stories

)

Black diamond: Why there is an urgent need to increase India’s investment in R&D in coal technologies

)

Are penguins at risk after deadly bird flu hits Antarctica for first time?

)

Family Planning: How many children are too many?

)

Why has Iran claimed Antarctica? Should the world worry?

)

- Environment

- Road to Net Zero

- Art & Design

- Film & TV

- Music & On-stage

- Pop Culture

- Fashion & Beauty

- Home & Garden

- Things to do

- Combat Sports

- Horse Racing

- Beyond the Headlines

- Trending Middle East

- Business Extra

- Culture Bites

- Year of Elections

- Pocketful of Dirhams

- Books of My Life

- Iraq: 20 Years On

Will Antarctica be the next victim of overtourism as visitor numbers continue to climb?

Balance between travel and preservation in world’s most remote wilderness is a fragile one.

As more travellers flock to Antarctica, the world's most protected wilderness faces an increasing conservation risk. Unsplash / Cassie Matias

Last year, for the first time, more than 100,000 tourists visited Antarctica. That figure is expected to increase in 2024.

It is in stark contrast to visitor numbers during the global pandemic when only two ships and 15 people ventured to the southern wilderness in the name of tourism .

Leslie Hsu, a freelance journalist and award-winning photographer, understands why. She had one of her most memorable holidays in the region.

She recounts a story of camping on the Kerr Point of Ronge Island, where she could hear the iceberg-laden waters of the Errera Channel lapping against the shore.

“I make my way towards the shoreline until I can hear waves striking rocks,” she tells The National . “Turning off my headlamp, I am engulfed in darkness, barely able to see my fingers in front of my face. At first, I feel exposed, vulnerable – unusual for someone who grew up camping, hiking, spelunking, climbing mountains and crossing rivers. Someone who came to Antarctica precisely to be alone with the coldest , driest, windiest, most hostile place on Earth.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Leslie Hsu Oh | Writer + Photographer + Editor (@lesliehsuoh)

“A series of glaciers calving, one after another like dominoes, ripples towards me. I feel the ground trembling. Water rushes towards me and I cringe, expecting to be swept away into the channel. After things settle down, I sit down on the soft snow. Surprisingly, I don’t feel cold at all, cosy in my wind and water-resistant parka and boots. I doze. I listen. I breathe. Out of the darkness, blacks brighten to greys. There is no sunrise, just a gradual increase in contrast.

“I hear a whale surface for air. Kelp gulls tweet a morning greeting. And just when I start to worry that maybe I shouldn't be sitting out here by myself, I see six Gentoo Penguins take form not a stone’s throw away. They are all sleeping with their necks tucked into their backs, perfectly camouflaged in the austere black and white landscape.”

It's precisely this type of once-in-a-lifetime experience that has so many travellers flocking to Antarctica.

Unique journeys across the White Continent

This polar region is roughly twice the size of Australia and 98 per cent covered in ice. It is the largest wilderness on Earth unaffected by large-scale human activities and, as the only continent without an indigenous population, it is also one of the most protected places on the planet.

Winter in Antarctica is from March until October, and when daylight hours disappear, temperatures plunge to minus 30-60°C and the physically remote destination becomes even more inhospitable. But by autumn, as the country’s unique wildlife begins to emerge from hibernation, so too do the zealous tourists.

Antarctica is also the only continent with no terrestrial mammals, but it does have millions of penguins, thousands of seals and eight different species of whale. The allure of seeing these creatures in the wild is one of the main reasons people keep coming to the remote land.

Google data comparing search traffic from 2019 to 2022 showed a 51 per cent rise in interest around Antarctica cruises, and a 47 per cent rise in interest for Arctic cruises. Other trips are on the rise, too. These include luxury travel company Black Tomato’s nine-night Antarctic adventure that sailed to the White Continent at the same time the region witnessed a rare solar phenomenon. Or Elite Expeditions' new voyage that will see travellers conquer the glacial beauty of Antarctica's Vinson Massif.

While the pause in tourism during the pandemic allowed wildlife to thrive, the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators estimates that 106,000 visitors travelled to the region in the 2022-2023 tourist season, meaning those who work to protect the White Continent and its environment are wary of this increasing interest.

A wilderness that belongs to no nation

Seven countries – New Zealand, Australia, France, Norway, the UK, Chile, and Argentina – have all laid claim to different parts of Antarctica, but the destination is governed by an international partnership to which more than 56 countries have acceded, making it a wilderness that belongs to no nation.