TYLER S. ROGERS, MD, MBA, FAAFP, AND BRENDAN LUSHBOUGH, DO, Martin Army Community Hospital, Fort Benning, Georgia

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(2):187-190

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Key Clinical Issue

What are the risks and benefits of less frequent antenatal in-person visits vs. traditional visit schedules and televisits replacing some in-person antenatal appointments?

Evidence-Based Answer

Compared with traditional schedules of antenatal appointments, reducing the number of appointments showed no difference in gestational age at birth (mean difference = 0 days), likelihood of being small for gestational age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.08; 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.66), likelihood of a low Apgar score (mean difference = 0 at one and five minutes), likelihood of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission (OR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.50), maternal anxiety, likelihood of preterm birth (nonsignificant OR), and likelihood of low birth weight (OR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.25). (Strength of Recommendation [SOR]: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence.) Studies comparing hybrid visits (i.e., televisits and in-person) with in-person visits only did not find differences in rates of preterm births (OR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.03; P = .18) or rates of NICU admissions (OR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.28). (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence.) There was insufficient evidence to assess other outcomes. 1

Practice Pointers

Antenatal care is a cornerstone of obstetric practice in the United States, and millions of patients receive counseling, screening, and medical care in these visits. 2 , 3 There is clear evidence supporting the benefits of antenatal care; however, the number of appointments needed and setting of visits is less understood.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends antenatal visits every four weeks until 28 weeks' gestation, every two weeks until 36 weeks' gestation, and weekly thereafter, which typically involves 10 to 12 visits. 4

Expert consensus and past meta-analyses have favored fewer antenatal care visits given similar maternal and neonatal outcomes. In 1989, the U.S. Public Health Service suggested a reduction in the antenatal visit schedule based on a multidisciplinary panel and expert opinion in conjunction with a literature review; however, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has not updated its guidelines, and practices have not changed. 5 A 2010 Cochrane review found no differences in perinatal mortality between patients randomized to higher vs. reduced antenatal care groups in high-income countries, and a 2015 Cochrane review showed no difference in neonatal outcomes for women in high-income countries. 6 , 7

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) review showed moderate- and low-strength evidence and did not find significant differences between traditional and abbreviated schedules when looking at many outcomes, such as gestational age at birth, low birth weight, Apgar scores, NICU admission, preterm birth, and maternal anxiety. The review was limited by a small evidence base with studies that are difficult to compare. The randomized controlled trials that were eligible were adjusted for confounding, whereas the nonrandomized controlled studies were not adjusted and were at high risk for confounding.

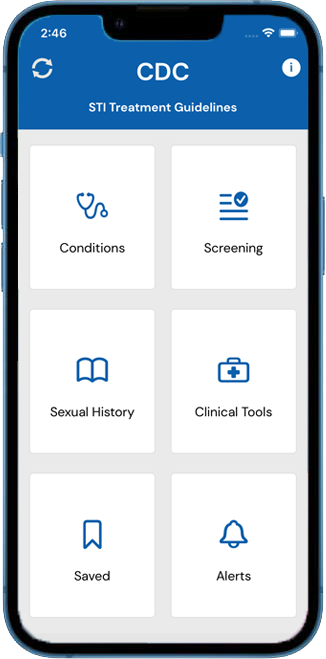

Telemedicine, defined as the use of electronic information and telecommunication to support health care among patients, clinicians, and administrators, is a new option for antenatal care delivery. 8 Televisits, the real-time communication between patients and clinicians via phone or the internet, are the specific interactions that encompass telemedicine. Recent literature suggests that supplementing in-person visits with televisits in low-risk pregnancies resulted in similar clinical outcomes and higher patient satisfaction scores. 9 The AHRQ review found no significant differences between rates of preterm births or NICU admissions for a hybrid model of televisits and in-person visits compared with in-person visits only. The review was limited due to the lack of adjustments for potential confounders in the study. For example, some of the studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which adds multiple confounders and potential for bias.

The AHRQ review offers limited opportunity for conclusions to suggest changes in current practice. The current evidence supports past evidence, suggesting that fewer visits are not associated with neonatal or maternal harm, and televisits may have a role in antenatal care. Many of the other outcomes of interest had insufficient evidence to generate conclusions.

Editor's Note: American Family Physician SOR ratings are different from the AHRQ Strength of Evidence ratings.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

For the full review, go to https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/product/pdf/cer-257-antenatal-care.pdf .

Balk EM, Konnyu KJ, Cao W, et al. Schedule of visits and televisits for routine antenatal care: a systematic review. Comparative effectiveness review no. 257. (Prepared by the Brown Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract no. 75Q80120D00001.) AHRQ publication no. 22-EHC031. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; June 2022. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/related_files/cer-257-antenatal-care-evidence-summary.pdf

Kirkham C, Harris S, Grzybowski S. Evidence-based prenatal care: part I. General prenatal care and counseling issues. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(7):1307-1316.

Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):199-208.

Kriebs JM. Guidelines for perinatal care, sixth edition: by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(2):e37.

Rosen MG, Merkatz IR, Hill JG. Caring for our future: a report by the expert panel on the content of prenatal care. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(5):782-787.

Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(10):CD000934.

Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(7):CD000934.

Fatehi F, Samadbeik M, Kazemi A. What is digital health? Review of definitions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020;275:67-71.

Cantor AG, Jungbauer RM, Totten AM, et al. Telehealth strategies for the delivery of maternal health care: a rapid review. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(9):1285-1297.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducts the Effective Health Care Program as part of its mission to produce evidence to improve health care and to make sure the evidence is understood and used. A key clinical question based on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program systematic review of the literature is presented, followed by an evidence-based answer based on the review. AHRQ’s summary is accompanied by an interpretation by an AFP author that will help guide clinicians in making treatment decisions.

This series is coordinated by Joanna Drowos, DO, MPH, MBA, contributing editor. A collection of Implementing AHRQ Effective Health Care Reviews published in AFP is available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/ahrq .

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2023 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 3rd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 3rd edition.

C antenatal care.

- Always begin with Rapid assessment and management (RAM) B3-B7 . If the woman has no emergency or priority signs and has come for antenatal care, use this section for further care.

- Next use the Pregnancy status and birth plan chart C2 to ask the woman about her present pregnancy status, history of previous pregancies, and check her for general danger signs. Decide on an appropriate place of birth for the woman using this chart and prepare the birth and emergency plan. The birth plan should be reviewed during every follow-up visit.

- Check all women for pre-eclampsia, anaemia, syphilis and HIV status according to the charts C3 - C6 .

- In cases where an abnormal sign is identified (volunteered or observed), use the charts Respond to observed signs or volunteered problems C7 - C11 to classify the condition and identify appropriate treatment(s).

- Give preventive measures due C12 .

- Develop a birth and emergency plan C14-C15 .

- Advise and counsel on nutrition C13 , family planning C16 , labour signs, danger signs C15 , routine and follow-up visits C17 using Information and Counselling sheets M1 -M19 .

- Record all positive findings, birth plan, treatments given and the next scheduled visit in the home-based maternal card/clinic recording form.

- Assess eligibility of ART for HIV-infected woman C19 .

- If the woman is HIV infected, adolescent or has special needs, see G1 - G11 H1 - H4 .

C2. ASSESS THE PREGNANT WOMAN: PREGNANCY STATUS, BIRTH AND EMERGENCY PLAN

Use this chart to assess the pregnant woman at each of the four antenatal care visits. During first antenatal visit, prepare a birth and emergency plan using this chart and review them during following visits. Modify the birth plan if any complications arise.

View in own window

C3. CHECK FOR PRE-ECLAMPSIA

Screen all pregnant women at every visit.

C4. CHECK FOR ANAEMIA

C5. check for syphilis.

Test all pregnant women at first visit. Check status at every visit.

C6. CHECK FOR HIV STATUS

Test and counsel all pregnant women for HIV at the first antenatal visit. Check status at every visit.

If no problem, go to page C12 .

C7-C11. RESPOND TO OBSERVED SIGNS OR VOLUNTEERED PROBLEMS

C12. give preventive measures.

Advise and counsel all pregnant women at every antenatal care visit.

C13. ADVISE AND COUNSEL ON NUTRITION AND SELF-CARE AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Use the information and counselling sheet to support your interaction with the woman, her partner and family.

Counsel on nutrition

- Advise the woman to eat a greater amount and variety of healthy foods, such as meat, fish, oils, nuts, seeds, cereals, beans, vegetables, cheese, milk, to help her feel well and strong (give examples of types of food and how much to eat).

- Spend more time on nutrition counselling with very thin, adolescent and HIV-infected woman.

- Determine if there are important taboos about foods which are nutritionally important for good health. Advise the woman against these taboos.

- Talk to family members such as the partner and mother-in-law, to encourage them to help ensure the woman eats enough and avoids hard physical work.

Advise on self-care during pregnancy

Advise the woman to:

- Take iron tablets F3 .

- Rest and avoid lifting heavy objects.

- Sleep under an insecticide impregnated bednet.

- Counsel on safer sex including use of condoms, if at risk for STI or HIV G2 .

- Avoid alcohol and smoking during pregnancy.

- NOT to take medication unless prescribed at the health centre/hospital.

Counsel on Substance Abuse:

- Avoid tobacco use during pregnancy.

- Avoid exposure to second-hand smoke.

- Do not take any drugs or Nicotine Replacement Therapy for tobacco cessation.

Counsel on alcohol use:

- Avoid alcohol during pregnancy.

Counsel on drug use:

- Avoid use of drugs during pregnancy.

C14-C15. DEVELOP A BIRTH AND EMERGENCY PLAN

Facility delivery.

Explain why birth in a facility is recommended

- Any complication can develop during delivery - they are not always predictable.

- A facility has staff, equipment, supplies and drugs available to provide best care if needed, and a referral system.

- If HIV-infected she will need appropriate ARV treatment for herself and her baby during childbirth.

- Complications are more common in HIV-infected women and their newborns. HIV-infected women should deliver in a facility.

Advise how to prepare

Review the arrangements for delivery:

- How will she get there? Will she have to pay for transport?

- How much will it cost to deliver at the facility? How will she pay?

- Can she start saving straight away?

- Who will go with her for support during labour and delivery?

- Who will help while she is away to care for her home and other children?

Advise when to go

- If the woman lives near the facility, she should go at the first signs of labour.

- If living far from the facility, she should go 2-3 weeks before baby due date and stay either at the maternity waiting home or with family or friends near the facility.

- Advise to ask for help from the community, if needed I2 .

Advise what to bring

- Home-based maternal record.

- Clean cloths for washing, drying and wrapping the baby.

- Additional clean cloths to use as sanitary pads after birth.

- Clothes for mother and baby.

- Food and water for woman and support person.

Home delivery with a skilled attendant

- Review the following with her:

- Who will be the companion during labour and delivery?

- Who will be close by for at least 24 hours after delivery?

- Who will help to care for her home and other children?

- Advise to call the skilled attendant at the first signs of labour.

- Advise to have her home-based maternal record ready.

Explain supplies needed for home delivery

- Warm spot for the birth with a clean surface or a clean cloth.

- Clean cloths of different sizes: for the bed, for drying and wrapping the baby, for cleaning the baby's eyes, for the birth attendant to wash and dry her hands, for use as sanitary pads.

- Buckets of clean water and some way to heat this water.

- Bowls: 2 for washing and 1 for the placenta.

- Plastic for wrapping the placenta.

Advise on labour signs

Advise to go to the facility or contact the skilled birth attendant if any of the following signs:

- a bloody sticky discharge.

- painful contractions every 20 minutes or less.

- waters have broken.

Advise on danger signs

Advise to go to the hospital/health centre immediately, day or night, WITHOUT waiting if any of the following signs:

- vaginal bleeding.

- convulsions.

- severe headaches with blurred vision.

- fever and too weak to get out of bed.

- severe abdominal pain.

- fast or difficult breathing.

- She should go to the health centre as soon as possible if any of the following signs:

- abdominal pain.

- swelling of fingers, face, legs.

Discuss how to prepare for an emergency in pregnancy

where will she go?

how will they get there?

how much it will cost for services and transport?

can she start saving straight away?

who will go with her for support during labour and delivery?

who will care for her home and other children?

- Advise the woman to ask for help from the community, if needed I1 – I3 .

- Advise her to bring her home-based maternal record to the health centre, even for an emergency visit.

C16. ADVISE AND COUNSEL ON FAMILY PLANNING

Counsel on the importance of family planning.

- If appropriate, ask the woman if she would like her partner or another family member to be included in the counselling session.

Ask about plans for having more children. If she (and her partner) want more children, advise that waiting at least 2 years before trying to become pregnant again is good for the mother and for the baby's health.

Information on when to start a method after delivery will vary depending whether a woman is breastfeeding or not.

Make arrangements for the woman to see a family planning counsellor, or counsel her directly (see the Decision-making tool for family planning providers and clients for information on methods and on the counselling process).

- Counsel on safer sex including use of condoms for dual protection from sexually transmitted infections (STI) or HIV and pregnancy. Promote especially if at risk for STI or HIV G4 .

- For HIV-infected women, see G4 for family planning considerations

- Her partner can decide to have a vasectomy (male sterilization) at any time.

Method options for the non-breastfeeding woman

Special considerations for family planning counselling during pregnancy.

Counselling should be given during the third trimester of pregnancy.

can be performed immediately postpartum if no sign of infection (ideally within 7 days, or delay for 6 weeks).

plan for delivery in hospital or health centre where they are trained to carry out the procedure.

ensure counselling and informed consent prior to labour and delivery.

can be inserted immediately postpartum if no sign of infection (up to 48 hours, or delay 4 weeks)

plan for delivery in hospital or health centre where they are trained to insert the IUD.

Method options for the breastfeeding woman

C17. advise on routine and follow-up visits.

Encourage the woman to bring her partner or family member to at least 1 visit.

Routine antenatal care visits

- All pregnant women should have 4 routine antenatal visits.

- First antenatal contact should be as early in pregnancy as possible.

- During the last visit, inform the woman to return if she does not deliver within 2 weeks after the expected date of delivery.

- More frequent visits or different schedules may be required according to national malaria or HIV policies.

- If women is HIV-infected ensure a visit between 26-28 weeks.

Follow-up visits

C18. home delivery without a skilled attendant.

Reinforce the importance of delivery with a skilled birth attendant

Instruct mother and family on clean and safer delivery at home

If the woman has chosen to deliver at home without a skilled attendant, review these simple instructions with the woman and family members.

- Give them a disposable delivery kit and explain how to use it.

Tell her/them:

- To ensure a clean delivery surface for the birth.

- To ensure that the attendant should wash her hands with clean water and soap before/after touching mother/baby. She should also keep her nails clean.

- To, after birth, dry and place the baby on the mother's chest with skin-to-skin contact and wipe the baby's eyes using a clean cloth for each eye.

- To cover the mother and the baby.

- To use the ties and razor blade from the disposable delivery kit to tie and cut the cord.The cord is cut when it stops pulsating.

- To wipe baby clean but not bathe the baby until after 6 hours.

- To wait for the placenta to deliver on its own.

- To start breastfeeding when the baby shows signs of readiness, within the first hour after birth.

- To NOT leave the mother alone for the first 24 hours.

- To keep the mother and baby warm.To dress or wrap the baby, including the baby's head.

- To dispose of the placenta in a correct, safe and culturally appropriate manner (burn or bury).

- Advise her/them on danger signs for the mother and the baby and where to go.

Advise to avoid harmful practices

For example:

not to use local medications to hasten labour.

not to wait for waters to stop before going to health facility.

NOT to insert any substances into the vagina during labour or after delivery.

NOT to push on the abdomen during labour or delivery.

NOT to pull on the cord to deliver the placenta.

NOT to put ashes, cow dung or other substance on umbilical cord/stump.

Encourage helpful traditional practices:

If the mother or baby has any of these signs, she/they must go to the health centre immediately, day or night, WITHOUT waiting

- Waters break and not in labour after 6 hours.

- Labour pains/contractions continue for more than 12 hours.

- Heavy bleeding after delivery (pad/cloth soaked in less than 5 minutes).

- Bleeding increases.

- Placenta not expelled 1 hour after birth of the baby.

- Very small.

- Difficulty in breathing.

- Feels cold.

- Not able to feed.

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website ( www.who.int ) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: tni.ohw@sredrokoob ).

Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website ( www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html ).

- Cite this Page Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 3rd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. C, ANTENATAL CARE.

- PDF version of this title (2.6M)

In this Page

- ASSESS THE PREGNANT WOMAN: PREGNANCY STATUS, BIRTH AND EMERGENCY PLAN

- RESPOND TO OBSERVED SIGNS OR VOLUNTEERED PROBLEMS

- GIVE PREVENTIVE MEASURES

- ADVISE AND COUNSEL ON NUTRITION AND SELF-CARE AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- DEVELOP A BIRTH AND EMERGENCY PLAN

- ADVISE AND COUNSEL ON FAMILY PLANNING

- ADVISE ON ROUTINE AND FOLLOW-UP VISITS

- HOME DELIVERY WITHOUT A SKILLED ATTENDANT

Other titles in this collection

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee

Recent Activity

- ANTENATAL CARE - Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care ANTENATAL CARE - Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Status of the WHO recommended timing and frequency of antenatal care visits in Northern Bangladesh

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

Affiliation Maternal and Child Health Division, icddr,b, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft

Roles Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation

Roles Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Public Health, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Professor and Director of Centre of Excellence for Non-Communicable Disease, James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Bidhan Krishna Sarker,

- Musfikur Rahman,

- Tanjina Rahman,

- Tawhidur Rahman,

- Jubaida Jahan Khalil,

- Mehedi Hasan,

- Fariya Rahman,

- Anisuddin Ahmed,

- Dipak Kumar Mitra,

- Published: November 5, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185

- Reader Comments

There is dearth of information on the timeliness of antenatal care (ANC) uptake. This study aimed to determine the timely ANC uptake by a medically trained provider (MTP) as per the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and the country guideline.

Cross-sectional survey was done with 2,731 women having livebirth outcome in last one year in Dinajpur, Nilphamari and Rajshahi districts, Bangladesh from August-November,2016.

About 82%(2,232) women received at least one ANC from a MTP. Overall, 78%(2,142) women received 4 or more ANCs by any provider and 43%(1168) from a MTP. Only 14%(378) women received their first ANC at the 1 st trimester by a MTP. As per 4 schedule visits by the WHO FANC model and the country guideline 8%(203) and 20%(543) women respectively received the first 2 timely ANC by a MTP; where only 1%(32) and 3%(72) received the first 3 visits timely and 0.6%(17) and 1%(29) received all the four timely visits. Factors significantly associated with the first two timely visits are: 10 or above years of schooling of women [adj. OR 2.13 (CI: 1.05, 4.30)] and their husbands [adj. OR 2.40 (CI: 1.31, 4.38)], women’s employment [adj. OR 2.32 (CI: 1.43, 3.76)], urban residential status [adj. OR 3.49 (CI: 2.46, 4.95)] and exposure to mass media [adj. OR 1.58 (CI: 1.07, 2.34)] at 95% confidence interval. According to the 2016 WHO ANC model, only 1.5%(40) women could comply with the first two ANC contacts timely by a MTP and no one could comply with all the timely 8 contacts.

Despite high coverage of ANC utilization, timely ANC visit is low as per both the WHO recommendations and the country guideline. For better understanding, further studies on the timeliness of ANC coverage are required to design feasible intervention for improving maternal and child health.

Citation: Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, Rahman T, Khalil JJ, Hasan M, et al. (2020) Status of the WHO recommended timing and frequency of antenatal care visits in Northern Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0241185. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185

Editor: Kannan Navaneetham, University of Botswana, BOTSWANA

Received: November 19, 2019; Accepted: October 10, 2020; Published: November 5, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Sarker et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding: This study funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The awarded BMGF grant number is OPP1146943. BKS received the funding. URL of funder website is https://www.gatesfoundation.org . The sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish and preparing manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Introduction

Approximately, 300,000 women die annually from pregnancy or childbirth-related complications around the world and almost all of these deaths occur in low-resource settings, and most of these deaths are preventable [ 1 , 2 ]. The South Asian region alone accounts for approximately one-third of the global maternal and child deaths annually [ 3 ]. The global strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health under the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 has set the targets to reduce maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to less than 70 per 100,000 live births, and the neonatal mortality to 12 per 1,000 live births or lower by 2030 [ 4 ].

High coverage of quality Antenatal Care (ANC) can play a crucial role to decrease maternal and child mortality rates and achieve national and global targets related to maternal and child health [ 5 – 7 ]. Studies found ANC received from skilled provider reduces the risk of pregnancy complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as- stillbirths, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm births, low-birth weight, fetal abnormalities and other fetal complications, possibly mediated through health promotion, disease prevention, screening and treatment which increases maternal and newborn survival [ 2 , 8 – 15 ]. The study also emphasized on the timeliness of ANC to ensure healthy pregnancy outcomes [ 13 ].

As per the previous World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended Focused Antenatal Care (FANC) Model; under normal circumstances, a pregnant woman should have at least four ANC visits [ 16 ]. Recently, WHO has issued “the 2016 WHO ANC model” with a new series of recommendations to improve the quality of ANC, which in turn help reducing the risk of stillbirths, complications and ensures a positive pregnancy experience. The new WHO model recommends a minimum of eight contacts. The 2016 WHO ANC Model covers 4+ ANC contacts that support the accomplishment of SDGs, which aims for reducing maternal and child mortality [ 6 , 17 , 18 ]. The 2016 WHO ANC model provides adequate knowledge to get prepared for birth or any complication, and lifesaving information for both mother and child as it reduces the delay of care-seeking for obstetric emergencies that contribute majority of the maternal mortality in a low-income area [ 7 ]. Though the recent 2016 WHO model recommends 8 contacts, the country guideline of Bangladesh still promotes 4 ANCs having slight time differences from the previously WHO recommended FANC model [ 19 , 20 ].

Globally, the coverage of early ANC visit within 14 weeks is reported to increase from 40.9% to 58.6% from the year 1990 to 2013 [ 21 ]. However, the uptake rate differs between developed and developing countries. In the year 2013, the rate of ANC uptake in developed and developing countries was 84.8% and 48.1% respectively [ 21 ].

According to the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys (BDHS) the trend of ANC coverage by a medically trained provider (MTP) is increasing [ 16 , 22 – 24 ]. Since 2004 to 2017 (51%-82%) ANC coverage had increased by 31 point percentage [ 16 , 22 – 25 ]. The percentage of pregnant women who made four or more ANC visit by any provider has increased from 17% in 2004 to 47% in 2017 [ 22 – 24 ]. In terms of the ANC coverage, geographical and regional variation exist in Bangladesh where data from BDHS 2017-’18 shows at least one ANC by a MTP is the highest in the South-west region (Khulna division91%) and the lowest in the Northeast region (Sylhet division-71%) [ 24 ]. Besides, the Northern region (Rajshahi-85% and Rangpur-75%) and the Southeast region (Chattogram-83%) also showed a higher prevalence of at least one ANC uptake. However, this regional difference fluctuated quite often since the last decade [ 16 , 22 – 25 ].

Despite having a rise in ANC coverage in Bangladesh, it stands among the top ten countries those are contributing nearly 60% of global maternal mortality [ 26 , 27 ]. Maternal and neonatal mortality remained quite unchanged in the last few years [ 24 , 28 ]. Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey (BMMS) shows the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is 196 per 100,000 live births in 2016 whereas it was 194 per 100,000 live births in 2010. Similar to maternal mortality, BDHS shows that neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births were 28 in 2014 and 30 in 2017–18 [ 16 , 24 , 28 , 29 ]. Bangladesh has the highest proportion of preterm births with 19% of births occurring before gestational weeks 37 [ 30 ]. The stillbirth rate in Bangladesh is 25.4 per 1,000 births [ 31 ]. According to BMMS 2016, the major causes behind the maternal deaths are hemorrhage (31%), eclampsia (24%), abortion (7%), obstructed/prolonged labor (3%), etc. [ 28 ]. To reduce pregnancy-related complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes, timely recommended ANC is imperative.

According to the BDHS-2017-18, less than 18% women received quality ANC care. Quality care is defined as receiving four or more antenatal visits, with at least one visit from a MTP and the components include measurement of weight and blood pressure, testing of blood and urine and receipt the information on potential danger signs during pregnancy [ 24 ]. In addition to the national survey, few other studies conducted in different parts of Bangladesh that also provide information of the total number of ANC visits that a woman receives during her pregnancy period [ 32 – 34 ]. However, none of the surveys showed how many women secured their visits timely as per WHO recommendations as well as a country guideline. So, there is a dearth of information in Bangladesh about the timeliness of ANC visits that a pregnant woman should adhere to WHO recommendations as well as to country guideline. It is essential to look deeper into the real status of the timely ANC uptake which has a greater impact on both mother and child’s odds of survival [ 32 , 35 ]. Therefore, we aimed to explore timely ANC uptake by MTPs as per the WHO recommendations and the country guideline from a cross-sectional survey in Northern Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

Study design and settings.

It was a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in both rural and urban areas. We had two study sites in rural areas and one in urban area from 3 northern districts of Bangladesh. Rural areas were Chirirbandar, a sub-district from Dinajpur and Saidpur, a sub-district from Nilphamari in Rangpur division and the urban area was Rajshahi City Corporation from Rajshahi division. According to the Population and Housing Census, the total population of Chirirbandar was 292,500, of which 146,619 were males, and 145,881 were female [ 36 ]. For Saidpur sub-district, the total population was 264,461, of which 133,737 were males, and 130,724 were females [ 37 ]. On the other hand, for Rajshahi City Corporation the total population was 449,756, of which 232,974 were males, and 216,782 were females [ 38 ]. According to census data, we found the female literacy rate was 42% in Dinajpur, whereas for both Nilphamari and Rajshahi, it was 39% [ 39 ]. In comparison to northern divisions (Rajshahi and Rangpur), southeast (Chattogram) and northeast (Sylhet) divisions had higher Maternal Mortality Ratio (Rajshahi-173/100,000 vs Chattogram-186/100,000 and Sylhet-425/100,000), Similar to maternal mortality, under-5Child Mortality Rate of Northern region (Rajshahi-43/1,000 and Rangpur-39/1,000) is lower than Southeast (Chattogram-50/1,000) and Northeast (Sylhet-67/1,000) regions [ 16 , 29 ].

Sampling and study participants

We applied two stages cluster sampling to select study participants in the study area. We considered some socio-demographic characteristics including age, years of schooling, occupation, religion, gravida and place of residence of study participants in the sampling frame to cover a range of information on similar issues from a variety of study participants. We considered government and non-government ‘Community-Based Health Workers’ (CBHW) catchment area as a cluster. We maintained similar population coverage for cluster selection. In Chirirbandar, we considered government CBHW’s catchment area, and for Saidpur and Rajshahi, we considered non-government CBHW’s areas as our clusters. In the first stage, we randomly selected one sub-district from two rural districts each and 10 wards (lowest administrative unit of city area) from the city corporation area. Then, we randomly selected 6 clusters (CBHW’s catchment area) out of 12 in Chirirbandar of Dinajpur district, 6 clusters out of 12 clusters in Saidpur of Nilphamari district and 6 clusters from 10 clusters in Rajshahi city area.

To recruit study participants, we applied the Expanded Program of Immunization method, which is a popular spatial sampling method named as the EPI method. We selected the starting point to start data collection in the selected cluster using the EPI method. We determined the midpoint of each cluster in consultation with the community people. To ensure the randomization process in interviewing eligible participants, we spun a bottle at the midpoint of each cluster to identify the direction from where we started searching study participants [ 40 , 41 ]. Interviewers visited every household on next door basis according to the direction of the bottle, and eligible participants were identified and interviewed. They collected data until the cluster’s sample size was met. During the household visit, if any eligible woman was absent, then data collectors tried at least two more times to interview her.

In each study area, around 900 women were interviewed, and finally, we completed 2731 interviews from the 3 study areas. Followings were the inclusion criteria for the study enrolment: (1) the woman had a live birth outcome in the last one year prior to interview (2) the woman passed 28 or more days after last delivery (3) the woman could hear, see and speak (4) the woman had permanent residence in the study area.

Data collection

We conducted this survey from August to November 2016. An expert research team from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) was involved in preparing a survey tool based on the research question and objectives of the study. Study investigators trained all the data collectors on the data collection tool. After that, a field test was done as pre-testing to check the feasibility of the survey tool in the real field. We checked the consistency of the survey tool and incorporated the feedback into the final version after pre-testing. The survey was administered through face-to-face interviews with eligible women.

Data management and quality assurance

An efficient team with an experienced team leader was closely involved with the data collection for ensuring the quality data. The team leader checked the completeness of every interview on the spot after the data collection through day to day supervision. Furthermore, a project research physician (PRP) and a research investigator (RI) coordinated all the data collection teams and team leaders on a daily and weekly basis for ensuring quality data and completeness of the interview. Re-interview was done by the team leaders, PRP and RI in a significant amount to check the accuracy and validity of data. At the same time, a database template was designed by an expert programmer of the Maternal and Child Health Division (MCHD), icddr,b to enter all the data online. Dot net (Version-10) software was used for data template design as appropriate [ 42 ]. The data template was designed in such a way that while entering data, none of the variables could go missing. Skipping options were also maintained strictly and logically to avoid entry mistakes. The expert data management team entered all the data through an online database. During entering data, this team entered both pre-coded and postcoded data simultaneously. For post coding of data, the research team was also closely involved with the data management team.

This study had no more than minimal risk to study participants. We obtained written informed consent from each of the participants prior to the interviews. We received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of icddr,b before data collection in the field. All the participants were married, and there was no need for obtaining consent for the minors from the guardian or parents as per IRB.

All the information given by the mothers were self-reported, however, we found 27% had a pregnancy registration card (also known as ANC card) and we checked their documents for relevance. Rest of the women who did not have a pregnancy registration card, we applied the probing technique to get the actual information from them. We determined the timely ANC coverage with regards to the WHO and the country guidelines. The primary outcome variable was the first two timely ANC visits by a skilled provider as per the WHO FANC model. Our country guideline resembles with the WHO FANC model and did not yet adopt the WHO 2016 model [ 43 ]. We considered the uptake rate of the first two timely ANC visits by MTP as per the WHO FANC guideline. We collected numbers of ANC received by a woman and when as per gestational weeks; and the providers of ANC. To estimate the ANC uptake, we considered women who had received at least one ANC from any provider. If any woman reported that, she had more than one ANC in the same week from different service providers, then ANC by the highest qualified service provider was considered. We followed the criteria of skilled or unskilled provider from the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) and considered qualified doctor, nurse/midwife/paramedic, family welfare visitor (FWV) and community skilled birth attendant (CSBA) as skilled or MTP. We used skilled provider and MTP interchangeably [ 16 ].

To analyze the timely ANC visits, we followed the criteria suggested by the two WHO models and country guideline. According to “the WHO FANC model”, the timely ANC visits refer to the 1st ANC visit between 8–12 weeks of pregnancy, the 2 nd ANC visit between 24–26 weeks, the 3rd ANC visit at 32 nd week, and the 4th ANC Visit between 36–38 weeks of gestation [ 43 ].

The timely ANC visits recommended by “the WHO 2016 ANC model”, refers to 1st contact within 12 weeks, the 2nd contact at 20 th week, the 3rd contact at 26 th week, the 4th at 30 th week, the 5th at 34 th week, the 6th at 36 th week, the 7th at 38 th week and the 8th contact at 40 th week [ 43 ]. Like the WHO FANC model, the country guideline also suggests at least 4 scheduled ANC visits where the timely ANC visits refer to the 1st ANC visit within 16 weeks of pregnancy, the 2 nd ANC visit between 24–28 weeks, the 3rd ANC visit at 32 nd week, and the 4th ANC Visit at 36 th week of gestation [ 20 ].

There is a slight difference among the 2016 WHO ANC Model, the WHO FANC Model and the Bangladesh guideline for recommending the1st timing of ANC. The 2016 WHO ANC Model recommended within 12 weeks of gestation for the 1 st contact whereas the WHO FANC Model recommended the 1 st visit between 8–12 weeks of gestation and the Bangladesh guideline recommended the 1 st visit within 16 weeks of gestation.

All the guidelines mentioned about the exact timing and ranges depending on gestational age. The WHO FANC model suggests timing for 1 st , 2 nd and 4 th visits in ranges and 3 rd visit on the exact time of gestational age. The country guideline suggests timing for 1 st and 2 nd visits in ranges and 3 rd and 4 th visits on the exact time of gestational age. The recent WHO 2016 ANC model suggests only first contact in range of gestational weeks and remaining 7 contacts on the exact timing of gestational weeks.

We considered Anderson and Newman’s framework of health services utilization to select the covariates that are associated with ANC utilization. This framework consists of three individual determinants- i. Predisposing ii. Enabling iii. Illness level [ 44 , 45 ]. We adopted age, sex as demographic and years of schooling, religion, occupation, women’s partner years of schooling and his occupation as social structure from disposing factors. In addition to previous literature and known confounder, we included these socio-demographic characteristics such as age, religion, place of residence, years of schooling status, primary occupation, number of pregnancies and living children [ 32 , 33 , 46 ]. Regarding age and schooling, we considered completed years. Age was categorized into three different groups such as less than or equal to 19 years, 20 to 29 years and greater than or equal to 30 years. Similarly, years of schooling was categorized into four groups as 0 to 4 years, 5 to 7 years, 8 to 9 years and greater or equivalent to 10 years of schooling. If a woman and her husband had multiple occupations, the primary occupation was considered based on their preferences in terms of their income and time spent on that occupation. We took the information about the current occupation of the survey respondents. We ensured their primary occupation by asking “what is your primary occupation?”, “What kind of work do you mainly do?”, “Are you involved in any income generating activities?” during our interview. Point to be noted here, mothers who were on maternity leave their occupation was marked as employed during the period of data collection. The women who were housewives referred to as homemakers for their occupation. By gravida, we meant the total number of confirmed pregnancies that our participant had in her lifetime.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analysis using the statistical software package STATA version 13.1 [ 47 ]. To identify differences between the groups, we used the χ2 (Chi-square) test for categorical data and independent sample t-test for continuous data. We checked the linearity assumption between the predictor and the outcome variable. We found there was a non-linear relationship between the predictors and the outcome variable. Then we transformed the covariate (age and years of schooling) into categories. We estimated both unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio using simple and multiple logistic regression models considering different covariates (age, years of schooling, gravida, occupation and place of residence etc.) to see the effect of covariates on the first two timely visits by MTPs. Bivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the association between the predictor and outcome variables using the Crude Odds Ratio (COR) at a 95% confidence interval (CI). Factors that were significant with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered for further estimation of the multiple logistic regression model. For example, the variable religion showed an insignificant relationship with the first two timely ANC visits and we excluded this variable from the regression analysis. Conventionally, p value of 0.05 is taken to indicate statistical significance. This 5% level is, however, an arbitrary minimum and p values should be much smaller to provide strong evidence. Before fitting the multiple logistic regression model, we did regression for the outcome of the first three and all four timely ANC visits by a medically trained provider, but almost all predictors were crudely insignificant for these two outcome variables separately. Furthermore, the number of observation was very low for the first three and all four timely visits by MTPs. Therefore, we considered the regression model for the first two timely visits by MTP according to the WHO FANC model.

“ Table 1 ” describes the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants living in both urban and rural areas. Result shows that almost two-third of the respondents (62%) belonged to the age group of 20 to 29 years and the majority of the respondents were Muslims (88%). A bit more than half of women (51%) passed grade 8 and higher. Years of schooling with 10 or more were higher among the respondents in the urban area (35%) than the rural area (26%). Overall, 95% of women were homemakers. In terms of the number of pregnancies, more than one-third of women (38%) had single gravida and the 50th percentile of respondents mentioned that they had experienced two pregnancies (median 2). Almost half of women’s husband had completed 8 or more years of schooling. About three-fourth of women (77%) had television exposure and only 11% of women read newspaper or magazine.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t001

Table 2 presents the ANC coverage of study participants by their place of residence. Almost all the women (98%) from both rural and urban sites received at least one ANC from any provider and overall 82% women (90% urban and 77% rural women) received at least one ANC from MTP. More than three-fourths of women (78%) had 4 or more ANCs by any provider while less than half of women (43%) received 4 or more ANC by a MTP. More than half of urban women (58%) and one-third of (35%) rural women reported to have received four or more ANC from MTP. However, about 17% of women received eight or more contacts by any provider and only 4% women received eight or more contacts from MTPs. Urban women (10%) were more likely to receive 8 or more ANC by MTPs than rural women (1%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t002

Fig 1 shows women received their 1 st ANC visit by gestational weeks from a skilled, unskilled and any provider. About one-fifth of the women (21%) received their 1st ANC within 12 weeks from any provider whereas 14% of them received from a skilled provider. The highest number of women (29%) received their 1st ANC between 13–16 weeks by any provider, whereas half of them (16%) received from a skilled provider.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.g001

“ Table 3 ” shows almost two-thirds of the women (63%) made the timely visit 2 between 24–26 weeks from any provider followed by more than one-third of the women (35%) received the visit 4 between 36–38 weeks. Overall, only 1.2% women received all the 4 timely visits and 18% women did not receive any timely ANC visit. There was a significant difference in receiving all the timely ANC visits by any provider depending on the residence.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t003

Fig 2 shows that, only 13% women received visit 1 (between 8–12 weeks) timely, but a higher proportion of women (37%) received visit 2 (between 24–26 weeks) at the recommended time. The figure also presents that only 8% of women received the first 2 timely visits (visit 1 & 2) while less than one percent women (0.6%) received all 4 ANC visits (visit 1, 2, 3 & 4) as per recommended timing of the WHO FANC model.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.g002

“ Table 4 ” describes that the majority women (74%) received ANC visit 2 between 24–28 weeks from any provider and 46% from a skilled provider. Half of the women received ANC visit 1 within 16 weeks from any provider while almost one-third of the women (32%) received from a skilled provider. More than one-third of the women (37%) received the first 2 timely visits (visit 1 & 2) by any provider whereas one-fifth of the women (20%) received by a skilled provider. Only 2% women received all the 4 timely visits (visit 1, 2, 3 & 4) from any provider while 1% women received from a skilled provider. In terms of all the timely ANC visits, more urban women received timely ANC visits than those of rural women. There were significant differences in receiving timely ANC visits by any provider except visit 4 and for all the timely ANC visits by a skilled provider based on place of residence.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t004

“ Table 5 ” presents that less than half of the women (43%) received contact 4 at 30 th week from any provider and near to one-third (27%) from a skilled provider. More than one-third of the women (39%) received contact 3 at 26 th week and contact 5 at 34 th week by any provider whereas one-fourth women received those contacts from a skilled provider. In line with the 2016 WHO ANC model, less than one-fifth of the women (16%) did not have any timely ANC contact from any provider and almost two-thirds of the women (63%) received at least one timing contact from a skilled provider. Only a few women (0.15%) received the timely first five contacts as per the 2016 ANC model from MTP. None of the women received all the 8 timely ANC contact either by a MTP or by any provider. Urban women were more likely to receive timely ANC contacts than those of rural women. There were significant differences in receiving timely contacts by any provider except contact 2 and 6; and by a skilled provider except contact 2 based on place of residence.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t005

“ Table 6 ” shows that the first two timely ANC visits are estimated derived from the WHO FANC model. Results suggest that there is a strong association between the first two timely ANC visits and all the socio-demographic characteristics except religion.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t006

“ Table 7 ” shows that almost all the indicators were crudely associated with a higher prevalence of receiving the first two timely visits. After adjustment, the odds ratio of the first two timely ANC visits for the women and their husbands who had completed 10 or more years of schooling were higher than those who did not pass primary school (0–4 years of schooling). Similarly, the likelihood of receiving the first two timely visits for employed women was more than two times than the women who were homemakers. Women who had exposure to mass media (newspaper/magazine) were more likely to receive the first two timely ANC than who were not exposed. Urban women were more than three times more likely to receive the first two timely ANC from a skilled provider than those of rural women.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.t007

This study shows that almost all the women from both rural and urban sites received at least one ANC and more than three-fourth of the women received 4 or more ANC visits by any provider in their last pregnancy. Less than one-fifth of the women received 8 or more contacts by any provider whereas only 4% women received at least 8 contacts by MTPs. However, this uptake rate significantly differs between urban and rural women.

According to the WHO FANC and the 2016 ANC model, the practice of receiving the 1 st ANC visit within recommended time is mostly delayed. There is very little difference in terms of receiving the timely 1 st ANC visit by both MTPs and any provider between the two WHO models. There is slight difference (13% Vs 14% by MTP and 20% Vs 21% by any provider) between the two models on the 1st ANC uptake and that is due to different recommended timings. The FANC model recommends first ANC between 8–12 weeks while the 2016 ANC model suggests to have the first ANC contact within 12 weeks. Therefore, when ANCs are received before 8 weeks, have been considered in the 2016 ANC model and was excluded in the FANC model. However, as per country guideline, the number of the 1st ANC uptake within 16 weeks of gestation by both MTPs and any provider was two times higher than the both WHO models. As Bangladeshi country guideline recommends an elaborated time range for the initiation of ANC, it kindles curiosity among all on the difference. Similar to our findings, three more studies were done in Bangladesh suggest that the uptake of first ANC is substantially delayed and another study revealed that the reasons could be maternal age, women’s education, residence, wealth index, pregnancy intention status, child’s birth order, and wanting more children [ 24 , 33 , 48 , 49 ]. Though no justification has found from the national guideline but our experience from working with the program in the field, we understand that culturally our women delay to disclose about their pregnancies even to their family members and relatives. They delay to seek 1 st ANC for few weeks thinking that pregnancy may terminate (abortion may occur) at an earlier stage, so they wait until 3 to 4 months of the pregnancy to report or visit healthcare centre. May be considering the cultural context, the national guideline adopted 1 st ANC by 16 weeks. Although there is no evidence, however, we are assuming that socio-cultural factors associated with delayed ANC care seeking might have been reflected on our national guideline and thus on the recommendations of the time ranges.

Though there are differences in timing, according to the WHO FANC model and the country guideline the highest proportion of the women received the timely ANC visit 2 by MTPs. Whereas according to the 2016 WHO ANC model, the highest proportion of the women complied with the contact 4 by MTPs. The country guideline mostly matches with the WHO FANC model but the 2016 WHO ANC model focused on the ANC contacts on exact weeks rather than considering ranges of weeks except ‘contact 1’ thus influences the variation of ANC uptake.

As per the WHO FANC model and the country guideline, coverage of all four timely ANC visits were extremely low and no woman could follow all the 8 timely contacts recommended by the 2016 WHO ANC model regardless of the providers. However, completing the 8 contacts is not applicable if women delivered babies before 38 weeks.

Because of the low observations for the all timely visits in both of the WHO models, the regression analysis of this study was limited to only the first two timely visits by a skilled provider as per the WHO FANC model. The regression analysis shows that women and their husbands with more years of schooling, employment, and living in the urban area were more likely to have the 1st two timely visits by MTPs.

Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics like marriage, family planning, and childbearing, Northern Bangladesh shows some variations with other Northeast and Southeast regions of Bangladesh. Early marriage (marriage before 18 years) among Northern Bangladeshi women (Rajshahi: 70% and Rangpur: 67%) is relatively higher than other parts of Bangladesh; therefore the prevalence of teenage childbearing status is also higher (Rajshahi: 33 and Rangpur: 32 vsSylhet: 14 and Chattogram: 27). However, Total Fertility Rate is lower in Northern part (Rajshahi and Rangpur: 2.1) than Northeast (Sylhet: 2.6) and Southeast (Chattogram: 2.5) regions. Regarding the modern contraceptive usage and unmet need for family planning, Rajshahi (modern method: 55%, unmet need: 10%) and Rangpur (modern method: 59%, unmet need: 8%) stand in better position than Sylhet (modern method: 45%, unmet need: 14%) and Chattogram (modern method: 45%, unmet need: 18%) divisions [ 24 ].

The BDHS 2017–18 data shows that the four or more ANC coverage raised to 47% from 31% in 2014. From the BDHS data for the Northern region, we found almost similar results with our study in terms of any ANC coverage by a MTP (BDHS: Rajshahi-84.5% and Rangpur-74.6% Vs this study-82%). The BDHS does not provide regional variation for number of ANCs, so, we couldn’t compare ANC coverage by numbers with BDHS. In addition to that, BDHS also does not present ANC coverage for 8 contacts [ 24 ]. Our study shows more ANC coverage for at least 8 ANC contacts by any provider compared to Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted in 2019 (17% Vs 5%) [ 50 ]. However, this difference might have induced due to having different sample size, study sites (local vs national), higher engagement of non-government organizations in providing maternal health services; especially in ANC services in our study areas, low human resource gap, access to health care, etc. [ 51 – 53 ].

In terms of four or more ANC coverage by any provider, a noticeable regional variation was observed for several South-Asian countries [ 24 , 54 – 60 ]. A national survey from Afghanistan shows that in 2015 their national ANC uptake rate for four or more ANC by any provider was 18%, likewise for Bhutan- 85% in 2015, India- 51% in 2016, Myanmar- 59% in 2016, Nepal-69% in 2016 and Pakistan-51% in 2017–2018 [ 55 , 58 , 59 ]. Despite sharing geo-economics commonalities, these South-Asian countries exhibit a good range of variation [ 61 ].

Regarding the 1 st ANC uptake by gestational age, this study found that only one-fifth of the women availed their 1 st ANC in the 1 st trimester (within 12 weeks) and more than one-fourth of the women received their 1 st ANC during 13–16 gestational weeks by any provider. Another Bangladeshi study conducted in Netrokona district found ANC uptake by a formal provider (Doctor, midwives, nurse, FWV, CHCP, health assistant, family welfare assistant, community skilled birth attendant and NGO health workers) in the 1 st trimester is 18% [ 32 ]. Although the operational definition of formal provider of that study slightly differ from our definition of any provider and MTP. If we compare it with our study findings, it shows 21% of the women received the 1 st ANC by any provider and 14% received by MTPs [ 32 ]. We assume the difference between the definition of the skilled and unskilled care provider might have influenced the difference. Many studies conducted in different parts of Asia show, there is a huge national and regional difference in terms of the 1 st ANC uptake [ 54 , 56 – 60 ]. Regarding the 1 st ANC uptake in the 1 st trimester, findings from several studies conducted in India showed the regional variation [ 56 , 57 , 60 ]. Indian national data showed, in 2016 more than half of the women received the 1 st ANC in the 1 st trimester, whereas in Andhra Pradesh more than three-fourth of the women and in eight other EAG states (Empowered Action Group) less than one-fifth of the women took the 1 st ANC uptake in the first trimester [ 56 , 57 , 60 ]. However, EAG states are defined as underprivileged and economically backward compared to other states of India and coverage from EAG states quite similar to our study findings [ 62 ].

Though we found Afghanistan’s four or more ANC uptake is lower than our study, but surprisingly; Afghanistan’s 1st ANC uptake in the 1st trimester was a bit higher than that of ours while Pakistan and Nepal showed more than double ANC uptake rate than our findings [ 54 , 58 , 59 ].

Studies show that the utilization of ANC in developing countries depends on many different factors [ 63 – 66 ]. Different studies done in Asian, European and African continents adopting Andersen behavioral model revealed that factors associated with underutilization of the ANC services in these regions are young age of the mothers, fewer years of schooling, lack of a paid job, poor language proficiency, support from a social network and lack of knowledge of the health care system [ 67 ]. Studies conducted in Bangladesh, different parts of India, Nepal, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Ethiopia explored that years of schooling and place of residence have influence over ANC uptake rate [ 32 , 54 , 56 – 60 , 68 – 70 ]. In comparison to this study; findings from the above cited studies share similarity with our findings on the findings about years of schooling and place of residence. Apart from those, geographical setting and socio-economic inequalities, cultural and normative barriers are attributing to this issue [ 71 ].

Similar to other low and middle-income countries (LMIC), Bangladesh is also improving its ANC coverage. The recommended 4 ANC visits was in a view of cost-effective model and result of extensive research, further, WHO recommended 8 ANC contacts in 2016 to expedite the improvement of Maternal and Child Health related status [ 33 , 72 ]. However, Bangladesh is still focusing on ensuring a higher uptake rate of 4 ANC visits with its government and non-government organizational initiatives [ 33 , 34 , 73 ].

Mounting all findings together from this and previous studies, we found that urban women can avail more ANC services than rural women although the ANC services are free of cost in government facilities everywhere in Bangladesh [ 74 , 75 ]. Based on those shreds of evidence, it can be asserted that ANC service inequality exists based on place of residence agreeing to the fact that 78% of people living in rural Bangladesh, while 70% doctors are stationed in urban areas [ 76 ]. In addition to unavailability of skilled provider, rural Bangladeshi women face various types of challenges to access maternal health services such as: poverty, long distance of health facility, waiting time at hospital, lack of female health staff, lack of skilled birth attendant, lack of education [ 77 – 79 ].

Even after conducting our study in high performing areas in terms of ANC coverage, extremely low prevalence of timely ANC uptake was observed maintaining the WHO and country guidelines. We can assume further worst-case scenario for low performing areas. Although we focused to discuss about ANC uptake by skilled provider in our result mostly but we found that many other national and also global studies we discussed in our paper tend to discuss the ANC uptake by any provider and used slightly different definition of skilled provider than country guideline [ 32 , 54 – 59 , 68 – 70 ]. We are assuming that it is due to low ANC uptake by skilled provider in Bangladesh and other Asian and African countries. So, to understand the countrywide situation, further evidence on timely ANC uptake is required.

Strength and limitation

Study team strictly maintained the quality of data collection in the field with close monitoring and supervision. The data derived from participants were rigorously rechecked and re-interviewed by team supervisors including a physician to minimize the scope of inaccuracy. We also checked relevant documents (such as- ANC card, pregnancy registration card, etc.) during our data collection to minimize the errors. Since this study was conducted only in part with higher ANC coverage, findings of this study hence do not represent Bangladesh uniformly. Again, the analysis was done depending on self-reported information without having a robust surveillance system; therefore, the scope of over or under-reporting may exist. Because of self-reported data, number and timing of ANC visits can be varied. According to all three guidelines, there are variations on the timing of ANC visits by exact week (e.g. 30th week) and range of weeks (e.g. 8–12 weeks); and result from range weeks will vary less but results from exact weeks may vary little bit higher. More to add, we did not explore important potential exposure variables such as household income, awareness about maternity care, cost of service, availability of healthcare services and proximity to the health facility which might have served as confounders and affected the result and the interpretation of the findings.

Conclusions

The coverage of ANC visits is quite high but the timeliness of ANC visits is very low as per both WHO models and country guideline. Initiation for the first ANC visit is also highly delayed. Government and non-government maternal health programs should focus on ensuring timely ANC visits. Ensuring at least 4 timely visits may help to make a way forward for Bangladesh endorsing 8 ANC contacts in the near future that is recommended by the recent 2016 ANC model. We suggest policy makers to promote education, women’s employment and health education through mass media as well as to ensure universal maternal healthcare coverage. Understanding the significance of timely ANC visits we further suggest to carry out more parallel studies both in countrywide and regional perspective putting emphasis on the feasibility of 8 contacts. The findings of this study will help the program and policy makers to design interventions to improve antenatal care coverage maintaining timeliness and thus reduce maternal and child mortality across Bangladesh.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.s001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241185.s002

Acknowledgments

icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to its research efforts. We are grateful to our study participants for their spontaneous participation and sincere commitment to fulfill the research endeavor. icddr,b is also grateful to the Government of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK for providing core/ unrestricted support.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 4. General Assembly UN. Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2017 [ https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework_A.RES.71.313%20Annex.pdf .

- 13. Lucas AO, Stoll BJ, Bale JR. Improving birth outcomes: meeting the challenge in the developing world: National Academies Press; 2003.

- 16. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2016.

- 17. WHO, UNICEF, Mathers C. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030). Organization. 2016.

- 18. World Health Organization. World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 19. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Health, Population, Nutrition eToolkit for Field Workers. 2018.

- 20. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). Union Health and Family welfare Center operating manual. 2014.

- 22. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, ORC Macro. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2004. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2005.

- 23. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2013.

- 24. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), ICF. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18: Key Indicators. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2019.

- 25. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2009.

- 27. World Health Organization, Unicef. Trends in maternal Mortality: 1990–2015: Estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. 2015.

- 28. National Institute of Population ResearchTraining, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research Bangladesh, MEASURE Evaluation. Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey 2016: Preliminary Report. 2017.

- 29. National Institute of Population Research Training, MEASURE Evaluation, ICDDR B. Bangladesh maternal mortality and health care survey 2010. NIPORT, MEASURE Evaluation, and icddr, b Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2012.

- 36. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning. Bangladesh Population and Housing Census 2011, Community report, Dinajpur. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning; 2014.

- 37. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning. Population and Housing Census, Community report, Nilphamari. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning; 2013.

- 38. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning. District Statistics 2011, Rajshahi. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning; 2013.

- 39. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning. Population and Housing Census 2011. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) and Ministry of Planning; 2015.

- 41. Myatt M. A short guide to undertaking surveys using the Simple Spatial Survey Method (S3M)2012.

- 42. Dot net framework [ https://dotnet.microsoft.com/download/dotnet-framework .

- 43. World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 47. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX. StataCorp LP; 2013.

- 50. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Key Findings. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS); 2019.

- 51. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning. Bangladesh Population and Housing Census 2011. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning; 2015.

- 52. Human Resource management (HRM), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). HRH Data Sheet 2014. Human Resource management (HRM), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), Bangladesh Secretariat, Dhaka; 2014.

- 53. World Mission Prayer League (LAMB Hospital). LAMB Annual Report 2017. [ https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c72ccf37a1fbd5b042f922c/t/5ca4bebe4e17b61118e6b70f/1554300705648/LAMB+Annual+Report+2017.pdf .

- 54. Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), ICF. Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey 2015. Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Islamabad, Pakistan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF; 2017.

- 55. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (unicef). Antenatal care 2016 [ https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/ .

- 57. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), ICF. India National Family Health Survey NFHS‐4 2015–16. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

- 58. Ministry of Health, Nepal, New ERA, ICF. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Ministry of Health, Kathmandu, Nepal; 2017.

- 59. National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan], ICF. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF; 2019.

- 61. THE WORLD BANK. Low & middle income 2019 [ https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-and-middle-income .

- 68. Chaka EE. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences-International Campus (TUMS-IC), Tehran, Iran. Studies.13(15):20–2.

- 73. National Institute of Population Research Training, Associates for Community Population Research, ICF International. Bangladesh Health Facility Survey 2014. NIPORT, ACPR, and ICF International Dhaka; 2016.

- 75. World Health Organization. Bangladesh health system review: Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2015.

- 76. UNDP Bangladesh. Covid-19: A reality check for Bangladesh’s healthcare system 2020 [10/08/2020]. https://www.bd.undp.org/content/bangladesh/en/home/stories/a-reality-check-for-bangladesh-s-healthcare-system.html .

- 77. Keya K, Rahman MM, Rob U, Bellows B. Barrier of distance and transportation cost to access maternity services in rural Bangladesh. Population Association of Ameria US. 2013.

National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

- Overweight and obesity

- Physical activity

- Chapter 2: Antenatal care

- Immunisation

- Growth failure

- Childhood kidney disease

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- Preventing child maltreatment – Supporting families to optimise child safety and wellbeing

- Social emotional wellbeing

- Unplanned pregnancy

- Illicit drug use

- Osteoporosis

- Visual acuity

- Trachoma and trichiasis

- Chapter 7: Hearing loss

- Chapter 8: Oral and dental health

- Pneumococcal disease prevention

- Influenza prevention

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Bronchiectasis and chronic suppurative lung disease

- Chapter 10: Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease

- Chapter 11: Cardiovascular disease prevention

- Chapter 12: Type 2 diabetes prevention and early detection

- Chapter 13: Chronic kidney disease prevention and management

- Chapter 14: Sexual health and blood-borne viruses

- Prevention and early detection of cervical cancer

- Prevention and early detection of primary liver (hepatocellular) cancer

- Prevention and early detection of breast cancer

- Prevention and early detection of colorectal (bowel) cancer

- Early detection of prostate cancer

- Prevention of lung cancer

- Chapter 16: Family abuse and violence

- Prevention of depression

- Prevention of suicide

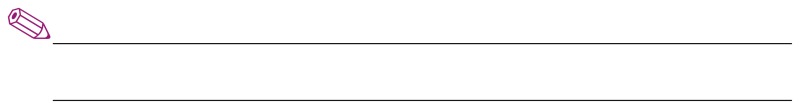

Antenatal care aims to improve health and prevent disease for both the pregnant woman and her baby. While many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have healthy babies, poor maternal health and social disadvantage contribute to higher risks of having problems during pregnancy and an adverse pregnancy outcome. 1,2 The reasons for these adverse outcomes are complex and multifactorial (Figure 1), and together with other measures of health disparity provide an imperative for all involved in caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to ensure they receive the highest quality antenatal care, and, in particular, care that is woman-centred, evidence-based and culturally competent. This chapter reflects recommendations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women from two modules of Australian evidence-based antenatal care guidelines 3,4 and incorporates new evidence published subsequently. For selected antenatal care topics, narrative summaries of evidence relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait women are presented below. These are: