- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 10

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Battle of Tours

At the Battle of Tours near Poitiers, France, Frankish leader Charles Martel, a Christian, defeats a large army of Spanish Moors, halting the Muslim advance into Western Europe. Abd-ar-Rahman, the Muslim governor of Cordoba, was killed in the fighting, and the Moors retreated from Gaul, never to return in such force.

Charles was the illegitimate son of Pepin, the powerful mayor of the palace of Austrasia and effective ruler of the Frankish kingdom. After Pepin died in 714 (with no surviving legitimate sons), Charles beat out Pepin’s three grandsons in a power struggle and became mayor of the Franks. He expanded the Frankish territory under his control and in 732 repulsed an onslaught by the Muslims.

Victory at Tours ensured the ruling dynasty of Martel’s family, the Carolingians. His son Pepin became the first Carolingian king of the Franks, and his grandson Charlemagne carved out a vast empire that stretched across Europe.

Also on This Day in History October | 10

Malala Yousafzai, 17, wins Nobel Peace Prize

This Day in History Video: What Happened on October 10

Us naval academy opens, vice president agnew resigns, whitesnake’s “here i go again” tops the charts, us navy fighter jets intercept italian cruise ship hijackers.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Colonel George Custer’s funeral is held at West Point

“porgy and bess,” the first great american opera, premieres on broadway, superman christopher reeve dies at age 52, a former postal worker commits mass murder, president dwight d. eisenhower apologizes to african diplomat, william howe named commander in chief of british army, eight hundred children are gassed to death at auschwitz.

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

History Hit Story of England: Making of a Nation

Battle of Tours: Its Significance and Historical Implications

Celeste Neill

01 oct 2018.

On 10 October 732 Frankish General Charles Martel crushed an invading Muslim army at Tours in France , decisively halting the Islamic advance into Europe.

The Islamic advance

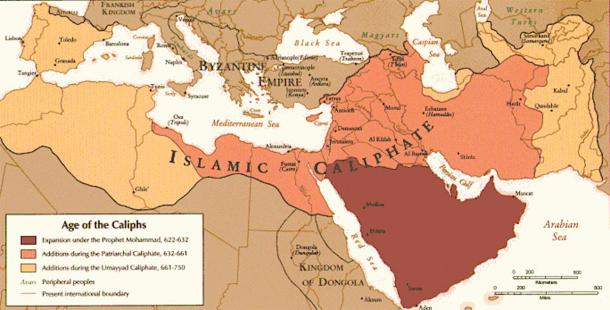

After the death of the Prophet Muhammed in 632 AD the speed of the spread of Islam was extraordinary, and by 711 Islamic armies were poised to invade Spain from North Africa. Defeating the Visigothic kingdom of Spain was a prelude to increasing raids into Gaul, or modern France, and in 725 Islamic armies reached as far north as the Vosgues mountains near the modern border with Germany .

Opposing them was the Merovingian Frankish kingdom , perhaps the foremost power in western Europe. However given the seemingly unstoppable nature of the Islamic advance into the lands of the old Roman Empire further Christian defeats seemed almost inevitable.

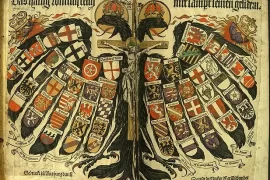

Map of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 AD. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 731 Abd al-Rahman, a Muslim warlord north of the Pyrenees who answered to his distant Sultan in Damascus, received reinforcements from North Africa. The Muslims were preparing for a major campaign into Gaul.

The campaign commenced with an invasion of the southern kingdom of Aquitaine, and after defeating the Aquitanians in battle Abd al-Rahman’s army burned their capital of Bordeaux in June 732. The defeated Aquitanian ruler Eudes fled north to the Frankish kingdom with the remnants of his forces in order to plead for help from a fellow Christian, but old enemy: Charles Martel .

Martel’s name meant “the hammer” and he had already many successful campaigns in the name of his lord Thierry IV, mainly against other Christians such as the unfortunate Eudes, who he met somewhere near Paris . Following this meeting Martel ordered a ban , or general summons, as he prepared the Franks for war.

14th century depiction of Charles Martel (middle). Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Tours

Once his army had gathered, he marched to the fortified city of Tours, on the border with Aquitaine, to await the Muslim advance. After three months of pillaging Aquitaine, al-Rahman obliged.

His army outnumbered that of Martel but the Frank had a solid core of experienced armoured heavy infantry who he could rely upon to withstand a Muslim cavalry charge.

With both armies unwilling to enter the bloody business of a Medieval battle but the Muslims desperate to pillage the rich cathedral outside the walls of Tours, an uneasy standoff prevailed for seven days before the battle finally began. With winter coming al-Rahman knew that he had to attack.

The battle began with thundering cavalry charges from Rahman’s army but, unusually for a Medieval battle, Martel’s excellent infantry weathered the onslaught and retained their formation. Meanwhile, Prince Eudes’ Aquitanian cavalry used superior local knowledge to outflank the Muslim armies and attack their camp from the rear.

Christian sources then claim that this caused many Muslim soldiers to panic and attempt to flee to save their loot from the campaign. This trickle became a full retreat, and the sources of both sides confirm that al-Rahman died fighting bravely whilst trying to rally his men in the fortified camp.

The battle then ceased for the night, but with much of the Muslim army still at large Martel was cautious about a possible feigned retreat to lure him out into being smashed by the Islamic cavalry. However, searching the hastily abandoned camp and surrounding area revealed that the Muslims had fled south with their loot. The Franks had won.

Despite the deaths of al-Rahman and an estimated 25,000 others at Tours, this war was not over. A second equally dangerous raid into Gaul in 735 took four years to repulse, and the reconquest of Christian territories beyond the Pyrenees would not begin until the reign of Martel’s celebrated grandson Charlemagne.

Martel would later found the famous Carolingian dynasty in Frankia, which would one day extend to most of western Europe and spread Christianity into the east.

Tours was a hugely important moment in the history of Europe, for though the battle of itself was perhaps not as seismic as some have claimed, it stemmed the tide of Islamic advance and showed the European heirs of Rome that these foreign invaders could be defeated.

You May Also Like

Why Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel is a Medievalist’s Guilty Pleasure

How Lord of the Rings Prequel Rings of Power Borrows from Ancient History

“When you receive it, your son will be gone” Stalingrad’s Last Letters

How a find in Scotland opens our eyes to an Iranian Empire

Do you know who built Petra?

The Dark History of Bearded Ladies

Did this Document Legitimise the Yorkists Claim to the Throne?

The Strange Sport of Pedestrianism Got Victorians Hooked on Coca

Puzzle Over These Ancient Greek Paradoxes

In Ancient Rome, Gladiators Rarely Fought to the Death

Archaeologists Uncover Two Roman Wells on a British Road

Young Stalin Made His Name as a Bank Robber

The Battle of Tours - 732 AD fr de , en ,

Charles Martel was a ruler of the Carolingian Frankish Empire in the early 8 th century AD. The empire encompassed the territories of much of modern day France, western Germany, Switzerland, as well as Belgium and the Netherlands, and was the dominant Christian power in Western Europe at the time. Having won a civil war between two competing kingdoms in 724, Charles had secured his position as head ruler of the entire Carolingian Empire, but had not yet been granted the title of King.

Although he was constantly repelling Saxon and Bavarian armies, as well as other threats, the empire was for the most part secure. Charles supported St. Boniface and other missionaries in their efforts to convert all remaining German tribes to Christianity as a way of uniting his region. The European continent was slowly becoming more prosperous and stable. But a new threat had begun working its way towards the heart of Western Civilization 100 years prior to Charles’ rule.

Islam Expanding

In the Middle East, the religion of Islam was formed in 622 AD. The region was quickly united under the new religion and then began to conquer more distant lands. By 711 Islamic armies had crossed the Gibraltar Straight and entered into Europe by way of present day Spain. It was from here that they began to set up new kingdoms and seek to conquer other parts of Europe, primarily for plunder of any type of treasure they could find.

The indigenous peoples of Europe referred to the Islamic invaders as the Saracens. From Spain the door stood wide open for the Saracens to enter into France, the conquest of which would have likely been followed by all the rest of Europe, and might have resulted in the banishment of Christianity from the Earth. At this time Christianity was not universally known or practiced, even by those nations which we today regard as the foremost in civilization. Great parts of Britain, Germany, Denmark, and Russia were still pagan and barbarous.

In 712 the Saracens entered into France and began pillaging the region for treasure. In 725 Anbessa, the Saracen governor of Spain, personally leads an army across the Pyrenees Mountains into France and takes the strongly fortified town of Carcassone. During the battle he receives a fatal wound, and the Saracen army retires into the nearby town of Narbonne before retreating back to the safety of Spain.

In 732 the Saracens invade France again under the command of Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman. They reach Bordeaux and begin to lay siege to the town when they get word of rich treasures in the Basilica of St. Martin in the city of Tours. They set off towards this area with the intent to plunder it for all it's worth.

Up to this point, the Carolingian Empire, ruled by King Charles, had no need to oppose the Saracens since they had not invaded any of his territories. The area of the Saracens plunder had been Aquitaine, an independent kingdom in southwestern France ruled by King Eude. Having learned of the damage being done to his neighboring kingdom, Charles becomes convinced of the danger presented to his territories. If Aquitaine were to be defeated, his kingdom would surely be next. Charles begins to march an army towards the Saracen invaders to confront them on his own terms.

While Abd al Rahman is advancing towards Tours, he receives intelligence regarding the advance of Charles and his army. He decides to fall back on Poitiers in order to occupy a more advantageous field of battle. Charles, leading an army of such size rarely seen in Europe, crosses the Loire River and joins the remains of the army of Aquitaine.

They come in sight of the Arabs on October 10 th , 732. The enemy spots Charles and his army and at first hesitates. The two armies remain camped, staring each other down, for seven days. Abd al Rahman at last gives the signal to attack. The Saracens rush the Franks with all their might but the Frankish front line holds. The battle rages on until late in the day, when a terrible clamor is heard from behind the Saracen army. It is King Eude, attacking the Saracen camp, stealing all of their ill-gotten plunder. The Saracen army frantically rushes back to protect their possessions.

In this moment of confusion the Franks advance. Abd al Rahman is killed in the chaos. The Saracens regain control of their camp. By this time the sun is beginning to set, and Charles decides to wait until the next day to resume combat, not wanting to risk losing any more troops at night.

The next morning the Franks awake early and assemble their army, expecting to rejoin battle with their enemy. They wait, but no enemy appears. They cautiously approach the Saracen camp and find it completely empty. The Saracens had taken advantage of the night and begun their retreat back towards Spain, leaving most of their plunder behind. As the battlefield was surveyed that day, it was realized that a vast number of Saracen men had been slain. The Franks counted their losses and found that only 1500 of their men had been killed.

Charles is finally proclaimed King of the Carolingian Empire, and for his enormous victory he receives the surname of Martel, "The Hammer". He would later become the grandfather of Charlemagne. The Carolingian Empire becomes the Holy Roman Empire, with Charlemagne proclaimed Emperor by the Pope on Christmas Day, 800 AD. This empire survives for over 1000 years until it is formally dissolved in 1806.

The battle of Tours marks a major turning point in the history of Western Civilization. One where the spread of Islam into Europe was reversed, and Christianity begins to give the people of Europe something more in common with each other. By the year 1000 AD, the continent would be doing fairly well. It would be generally free from foreign attack and steadily creating a more prosperous future.

Do not assume that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. Matthew 10:34

« Previous Post

Johannes Kepler

Next Post »

Sign up for email updates .

Welcome new readers!

In a hope to share any interesting historical stories I come across in the future I will be writing and posting articles whenever I can. Hopefully quite often.

I'll also be keeping you up to date on any good reads I come across in the Recommended section.

Looking for something in particular? Find it more quickly on the Search page.

And here is a complete list of all articles since the beginning.

Recent Articles

The Battle of Lepanto - 1571 God Rest You Merry Gentlemen The Druids The Gartan Mother's Lullaby Earth's Axial Precession Bronze Age Civilization Collapse Winterfylleth (Ƿinterfylleþ) David Livingstone Jettying - Unique Architectural Style Good King Wenceslas The Christmas Star Captain Henry Morgan Indo-European Migration The Siege of Paris - 1870 European Forests

"It is possible to believe that all the past is but the beginning of a beginning, and that all that is and has been is but the twilight of the dawn."

~ H.G. Wells

The Discovery of the Future

Personal Blog | Recipes | Donate

Content copyright 2014-2024 - www.classichistory.net - All rights reserved | Disclaimer

You May Also Like:

Dona Nobis Pacem

Western Civilization prior to World War I

The Ever Increasing Size of the Known Universe

Romantic - The History of a Word

73 - 209 - Thanks for the detailed story of the Battle of Lepanto… as a dedicated lover-of-Venice, I have seen the paintings in the Doges Palace and knew of its significance. Here are the details. As noted, this ranks w/the defense of Vienna in 1683(?); check,as well, the legendary defense of Malta sometime in the late 1400’s; as deep as it gets.

71 - 187 - Thank you so much for this.

71 - 189 - You're welcome. Thank you for reading.

71 - 204 - Too kind :) Thanks for reading Karen.

71 - 203 - Wonderful precise information, Thanks so much !

71 - 217 - Thanks for sharing inspiring rare history on Druids. Even I'm Indonesian..don't know why I like to.learn on old European belief systems such as paganism & druids :)

70 - 223 - I was walking my dog thus morning and as I walked this song came to me. I couldn’t speak English when I started school as we were refugees to Australia after WW2. I learnt this lullaby in Primary School and somehow it stuck. Thank you for all the details. I have often wondered what the meaning of some of those words were. I had a yearning to go to Ireland all my life the. Finally in 2015 I arrived, met by two Irish friends. As I stepped off the plane onto Irish soil and began to walk I “heard” my name clearly stated - not by a human voice, even though I looked around as it was such a surprise. I have a string connection to Ireland and have told the story of St Bride of the Isles and Padraic Column’s ‘King if Ireland’s Son’ to many children over the years.

69 - 177 - Sorry, but I do wish people who write articles mentioning astrology would go to the trouble of actually learning about astrology. The zodiac has nothing whatsoever to do with constellations, apart from the Greeks giving names to the signs from some of the constellations at that time. The zodiac was designed by ancient Babylonians, based on their calendar of 12 (and occasionally 13) lunar months, with 12 equal signs fixed to the March equinox. It has always been about the signs. The Western Tropical Zodiac will always begin with 0 degrees Aries on the March equinox and the stars have no relevance to this at all. The precession of the equinoxes and the alleged astrological ages are a minor oddity which astrologers generally have very little interest in.

69 - 186 - If the stars have no relevance to astrology, what relevance do the planets have? Are the positions of the planets determined in relation to the “signs” as given by astrology, or are their positions determined in relation to their apparent positions relative to the ecliptic and the stars visible in that celestial band.? If we’re to disregard the apparent positions of the stars, why bother to observe the positions of the planets, either?

69 - 199 - This article is about precession, which is obviously tangential to astrology, but the article never mentions the word. I'm not sure what you're going on about. The subject matter, especially in reference to constellations, is absolutely appropriate, as the ancients clearly were concerned about the positions of stars and planets, to think otherwise is absurd. The Egyptians understood the ages beginning and ending with certain star positions, whoever built the lion sphinx statue aimed it at Leo (the Lion CONSTELLATION), which tells us that it was likely built during that zodiacal age. I'm not sure how you can disregard the obvious tie-ins to key moments in history with what's marked out in the sky via constellations.

69 - 218 - Very understandable article , just what I was looking for as I have no background in astronomy. Thanks for your efforts.

67 - 220 - Search and end the answer

67 - 221 - Search and end the answer

66 - 176 - Truly David Livingstone was a greatest missionary and explorer in Africa no one else other than him from Europe has left such a record. He will always be remembered for his great work in Africa.

64 - 128 - Wonderful story. Excellent history. Great Christmas Song too! Especially Luke 6:38

64 - 130 - I enjoyed playing piano recitals of Good King Wenceslas as a child - for the old folks in the nursing homes in our town. Thank you for the history on this beloved King.

64 - 135 - Thank you Teresa for your kindness to the elderly. Nursing homes are filled with lonely souls who sincerely appreciate such acts of generosity.

64 - 210 - I’ve played this for years! even posted a recording on YouTube under “Safe Sax Trio” from December 2020. it has a special connotation as Mi amor,Blanka, is Czech, born and grew up in Prague,Bohemia…St.Wenceslas being the patron Saint of the Czech People.????

61 - 95 - h

60 - 125 - "The Indo-Europeans were a people group originating in the plains of Eastern Europe, north of the Baltic and Caspian Seas in present day Ukraine and southern Russia." Surely you meant the Black sea and not the Baltic....

60 - 126 - Ha, yes I meant the Black Sea. Thanks Pgolay.

56 - 83 - Wild temperature swings throughout the years!

56 - 84 - Indeed! All the more reason to be thankful for the forests we are enjoying today.

55 - 137 - Interesting article! I'm curious, what were the sources about Hippocrates and his communications with Athens and Persia in regard to the plague?

55 - 138 - Thank you! Hippocrates' own writings on this subject have been translated into English. Wesley D. Smith has some good modern English translations: https://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0674995260 Artaxerxes sends a letter to Hippocrates begging for help: "the renown of whose techne has reached even to me, as much gold as he wants, and anything else that he lacks in abundance, and send him to me" Hippocrates replies: "Tell the King I have sufficient food, clothing, and shelter, and all the necessities that I require for life, and that I have no wish for Persian wealth or to save foreigners from disease, since they are enemies of the Greeks."

55 - 145 - I really like Athens because it is truly a unique place with a rich history and unique distinctive features. Of course, there are a great deal of reasons to fall in love with this city because it’s a true calling card of Greece. After reading your article, I became more convinced that it is an incredible city in which ancient traditions and modernity harmoniously intertwine with each other into a single whole. It is so cool that you mentioned the Temple of Poseidon because I think that it’s such a wonderful way to delve into the history of Athens and feel the atmosphere of ancient times. I think that Athens is the best city in Greece for wine connoisseurs because it seems to me that you can try delicious and rare Greek wines there, getting unforgettable impressions. Art and culture in Athens are so incredible and multifaceted that it can’t leave you indifferent. It is an indisputable fact that the halls of the Museum of Cycladic Art are impressive in their scope and they have very interesting interactive expositions. It is so cool that there are so many incredible things and I think you will always find something to look at.

43 - 14 - Interesting article. An enjoyable read. Thanks

43 - 15 - Glad you enjoyed it!

40 - 149 - I was wondering where that cross at the top of the page is located? It is quite impressive and I stare at it a great deal! If you can help me I would greatly appreciate it! God bless you!!!

40 - 152 - William, The peak is Punta Selassa in the province of Cuneo, Italy. You can hike to the cross starting from the village of Calcinere on the Po River in the valley below. God bless you too!

39 - 81 - IS IT Possible to buy a hybrid checknut IMMUNE TO THE BLIGHT?

39 - 116 - very good information,we have many of these trees in our neighborhood. they were originally planted in the 1930's when the area was a berry farm and orchard. they have now spread over about a 50 acre residential area growing in just about any vacant space and producing huge amounts of nuts. Gig harbor washington.

39 - 180 - god, I had never heard of this. what a tragic story. Those forests must have been a true sight to see.

39 - 181 - I appreciate that you mentioned that chestnut trees are included in our holiday experience. My aunt mentioned last night that she and my mother planned to have information about hybrid chestnut trees for the farm project development they want. She asked if I had any idea what would be the best option to consider. I love this helpful article, I'll tell her she can consult a trusted hybrid chestnut trees service in town as they can provide information about their trees.

39 - 184 - This is incredibly sad. We have lost so much….thank you…anyone who has protected this wonderful, God given tree.

38 - 65 - Wow! That was quite an ordeal.

38 - 124 - Amazing story! Growing up in the Antelope Valley (Edwards AFB's location), we heard of a great number of accidents as really smart and competent test pilots pushed the limits of technology. My dad knew one "sled driver" who flew sailplanes as a hobby!

37 - 61 - The Frost Fair sounds like fun.

37 - 62 - Interesting article. This is the first I've heard of " Frost Fair ".

37 - 63 - I imagine it would be a lot of fun. Spontaneous community events like this always have a unique feeling to them.

37 - 64 - It was definitely a special phenomenon in the history of England.

36 - 11 - Very informative article. I love watching the lady play the organ at church and have always wondered what's under the hood.

36 - 12 - A very interesting and informative article. I have often wondered what the stops were for. The history and description of operation answered many questions.Thankyou.

36 - 13 - Glad it could help Kim. There is certainly quite a bit going on inside of these beautiful machines.

36 - 79 - Very well thought out article. I ran a small organ shop for 40 years that built some major organs around the world - one in Toyota-shi Concert Hall with about 4000 pipes. I am now retired, but want to write a book to pass my thoughts on to future generations of organ builders. Could I borrow some of the historical information you put together as you have said so much with less words and really good. Thanks!

36 - 80 - Thanks for your kind words John. Yes please use whatever you feel would be useful, just reference this website as a source. The goal of this website is to simply pass on our history to future generations. So if I can help with your book at all please reach out to me. Use any of the images or references in this article if you think they would be useful.

36 - 87 - A most helpful article which has answered many questions The organ is fascinating and invaluable. It hasn’t yet replaced orchestras

36 - 88 - A very interesting article, but who squeezed the bellows? Was it done by boys and how many and would they have been building up the air pressure for a time before the organ was to be played?

36 - 89 - In all my research I found that a volunteer from the church would power the smaller organs. For larger organs someone was paid to pump the bellows. These larger ones would have 3 or more bellows.

36 - 96 - Liked it! Very useful

36 - 140 - The article mentions that Roman and Byzantine organs were made of bronze (copper + tin) pipes, but there's nothing mentioned about modern organs. Are they made of brass (copper + zinc)?

36 - 188 - Thanks for this great article

35 - 58 - Such an incredible voyage.

35 - 59 - you should write an article about cook's third voyage

35 - 60 - Its in the works, check back here in a few months. Glad you enjoyed this one.

34 - 54 - This article is a nice little gift for the upcoming Christmas season.

34 - 55 - The song touches my life day by day and I needed musical copy of the same (notation). Thanx

34 - 56 - thanks NOEL! I pick a theme for Christmas each year and this is it for 2019. Christmas is everyday - as Jesus is with us everyday, renewing us with his love! Noel! Maria

34 - 57 - Great choice! True that Jesus is with us every day, not only around Christmas. Merry Christmas Maria

33 - 52 - Nice article!!!

33 - 53 - Thank you! It was a lot of work but I think it turned out not half bad.

31 - 46 - This makes me curious as to why Christianty succeeded spreading predominately westward from its Roman epicenter, yet failed doing the same eastward. Any ideas?

31 - 47 - How does the basilica and its parts like the nav relate to the Christian ceremony?

31 - 48 - Hi! I'm an architecture student and I would like to know what are other examples of Early Christian Churches and also their parts (name of the rooms, space, etc.); I just wanted them as references for my future subjects :D Thanks a lot

31 - 49 - I would have to do some more research on the later years of Christianity, but I would say that Christianity did spread eastward. This was likely halted by the pushback of Islam in the seventh century. Egypt was as much of a Christian stronghold as Rome until the Muslim conquest in the seventh century.

31 - 50 - The Nave is a space specifically reserved for procession of the choir or acolytes from the entrance towards the front of the church. Church goers sit in pews on the outer sides of the nave. Next is the Transept, which is where a priest or minister gives the sermon. Above that and at the front of the sanctuary is the choir loft.

31 - 51 - I spent quite a bit of time researching the churches in this article and these were the oldest ones I could find. If I find more I will certainly add them to the article. See the comment above for a list of the separate rooms of a church. Thanks for reading and good luck to you in architecture school!

31 - 75 - Are there any other examples of early Christians of this time period translating roman civic buildings into their new society?

31 - 76 - Ben, the churches listed in this article are the earliest ones that I could find that were constructed originally for the specific purpose of housing Christian worship services. Other churches exist from this time period that were simply converted from the worship of Roman gods. The Temple d'Auguste et de Livie in France is one such example. So old Roman temples were converted to churches but there is very little evidence that Roman civic buildings were converted to churches.

31 - 90 - Hello, thank you for an intresting article. Would you recommend any online resources or books one could use to explore Christian Architecture space? I will appreciate your feedback.

31 - 91 - Monuments of the Early Church by Walter Lowrie was my main source for this article. You can read it here . Other than this book, there are very few sources available for architecture of the early church, so I had to look at individual churches and compare them to established architectural norms from the rest of society at the time. There are plenty of resources available for church architecture after 1000 AD, such as Britannica.

31 - 97 - hi,this is malar.thank you for your wonderful and helpfull article. i need an article about egptian civilization like this. did you have any idea about preparing it?

31 - 98 - Glad you enjoyed it Malar. I have not thought of looking into Egyptian architecture. But it would certainly be interesting to see if the architecture made some kind of progression as the centuries went on. I may look into that in the future, thanks for your suggestion!

31 - 101 - Hi, i enjoyed reading your post. I wanted to know in what period does Paleo-Christian architecture took place?

31 - 103 - Thanks! Paleo-Christian describes the time period before the Byzantine Era. This could be before the dedication of Constantinople in 330, or before the Age of Justinian in the 6th century.

31 - 105 - A roof is arguably the most important aspect of every house - it protects your property and those living in it. As time goes by, the structure or appearance of the roof may be damaged, and need repairs or maintenance. Contact our roofing experts today for a free, no-obligation appointment and estimate. https://www.stgeorgeroofing.com.au/

31 - 117 - Hi, thank you for all the historic information here. Please can you throw more light on how the church started under the trees and haw they transcended to church buildings. Thanks.

31 - 200 - One of the most iconic features of early Christian architecture is the basilica plan, characterized by a rectangular nave, side aisles, and an apse.

30 - 112 - Thank you for the story of 3 amazing musicians

30 - 113 - Thanks for reading David!

30 - 133 - beautiful story! i love her work and im so happy her storys getting told more and more

30 - 178 - I was watching the movie song of Love and I wanted to find out some different questions and this website popped up and I was mesmerized. I love this! Thank you for sharing this

30 - 179 - Thank you for reading! I have never seen that movie, thanks for recommending it.

30 - 190 - Wonderful story, on May 7th I am going to Toronto for the concert in memory of Brahms(it his birthday),very excited !

30 - 191 - That sounds amazing! I hope you enjoy the concert, thanks for reading.

30 - 212 - i first learnt it from my piano teacher,but i love this story,so i decided to search it up.Your web was the first to pop up, so i clicked in and discovered a lot more deeper in their relationship.Overall,i love your informational text!

30 - 213 - i first learnt it from my piano teacher,but i love this story,so i decided to search it up.Your web was the first to pop up, so i clicked in and discovered a lot more deeper in their relationship.Overall,i love your informational text!

30 - 219 - Thank you Sara! I'm happy you enjoyed it.

29 - 44 - What a beautifully written and illustrated article.

29 - 45 - Thanks Paul. Its a lot of fun to put yourself in the shoes of people in the past, and try to see the Universe from their perspective.

29 - 104 - I enjoyed your paper very much. Thank you for writing it.

29 - 201 - Thanks for the wrintings please provide more coz i loved these ones.

28 - 42 - Makes one wonder: without horrific barbarism, would have global civilization expansion been delayed?

28 - 43 - The threat of unexpected attacks probably did motivate people to work together a little more for the purpose of defense. I would say that adversity of any kind betters individuals as well as civilization as a whole.

27 - 40 - Wowzers! I can't wait till the next solar eclipse!!!

27 - 41 - I loved your blog article. Really Cool. dkekkcedkdca

26 - 37 - This website really helped me when doing an assignment on James Cook! Thanks so much for the great information on here

26 - 38 - write an article about his third voyage as well

26 - 39 - Glad it could help Ben! I have an article about Cook's third voyage in the works so check back here in the future. Thanks for reading!

25 - 36 - Thank you Janet! I try to make these articles as short and concise as possible but most of the time they end up being so long because there's just so much to say. Glad to hear I accomplished those goals on this article and I'm glad you enjoyed it!

25 - 35 - Enjoyed your history of personal wealth. Quick, easy to read and understand and interesting! Looking forward to reading the other articles. Thank you for sharing Janet ( In California )

25 - 169 - Very nice… I really like your blog as well as website. Very useful information and worth reading. Thanks.

24 - 71 - Thank you for your summation of the Christmas Truce. I was searching for the hymn, "Dona Nobis", when I came across your article. Now I can share both historical items with my nine-year-old granddaughter who is very interested in what our soldiers have endured and done for us.

24 - 72 - Thank you for reading Susan. I'm happy to hear that younger people are interested in our ancestor's sacrifice for us. Its wonderful that you're taking the time to talk to her about these kinds of things, they are not easy to hear or completely understand. When she is older you could share another article I have regarding The Great War titled Western Civilization prior to World War I .

24 - 93 - I heard about this truce many years ago and just had to try and find the background. I have thought of this for many many years and it pulls at my heart strings every time I hear Silent Night. Nit being directly connected to Military I wonder, “do this truce still happen each year on Christmas Eve?” I sure hope it do. War is such a terrible thing. My wish is for everyone lot live in peace. What a wonderful world it would be.

24 - 214 - very cool article.

24 - 215 - Hi, why this passage

23 - 25 - Years ago we sang with a quire the song Dona Nobis. During that song I had to sing English text. The words were if I rember well If I had word... Do you happen to know where I can find this version of Dona Nobis. Gr, Frans Pennings Cuijk. Holland.

23 - 26 - If this is in reference to the Mozart traditional Dona Nobis Pacem that is commonly featured many times on U Tube etc, The one with 5 verses each of different melody. why can it not be found as a recording, cd or whatever for sale, anywhere. Do you know a source? John P. Thank you.

23 - 27 - lovely

23 - 28 - I live in a retirement village and am aged 80. Eight of us, with the aid of one who was a music teacher, are trying to learn Dona Nobis Pacem to sing at our village's annual variety concert - without an accompanist! Please wish us luck! :)

23 - 29 - 1. Snobbish attitude towards "folk Music) 2. Peace is welcomed all the year round, not only at Christmastime.

23 - 30 - Frans, If you are wanting to download the version on this page you should try this link below. They have three versions of the song there. If you are looking for a version of the text in another language please let me know and I will make a page with the text in that language for you. http://www.westminsterdayton.org/music/listen.html

23 - 31 - More like a distain for what is called "academic." I agree but the point still stands that it is sung more often around Christmastime.

23 - 32 - Good luck Margaret. Our Men's choir in Sydney sang another (non-Mozart) version of Pacem. Halfway through, we froze, and only slowly found our peace.

23 - 33 - Thank you, John. Hope we don't freeze, but then it's warmer up here in Brisbane. :)

23 - 34 - Good luck to you Margaret! Post a link to your performance if at all possible. This is a beautiful song and every rendition is unique.

23 - 92 - no

23 - 121 - I must say I'm really impressed by the nice write-up you have here. You actually did a great job, unlike most bloggers I've seen on the internet talking about this same topic. Just reading the first few paragraphs, I was already locked in the content. Bravo and keep up the good work. If you have the time, I would appreciate it if you could help me rate my blog .

23 - 127 - Thank you for providing this service! My husband and I are doing a concert at a retirement home tomorrow (voice and Ukrainian bandura) with a mixture of Ukrainian and other music,and I couldn't locate the sheet music to check what to say about this song's origins in the introduction. I typed Dona Nobis Pacem into Google, and boom, there was your article with exactly what I needed! 16th-17th century unknown German composer.

23 - 134 - Bach's "Dona Nobis Pacem" in his great B minor mass is as beautiful as music or man can get.

22 - 119 - not good

21 - 22 - Abd al Rahman needed just a little more patience. Islam would take over Europe. Sadly,the pride, heritage and national boundaries of these countries are disappearing.

21 - 23 - Damn i love history i hope i dont die soon so i can see the advancement of modern society.

21 - 24 - That does appear to be the case at the moment. But it is anyone's guess what the next era in history will be like.

21 - 82 - This is a great summary of the Battle of Tours. It amazes me that this great battle is not more known to western society. As you say in the final para "a major turning point in western civilisation" yet very few know it.

21 - 86 - Thanks Peter. I wish we were taught more history in general but especially events like this one. We all have an amazing story.

21 - 85 - If you do then make sure to write your experiences down somehow. People in the future will be very interested in your perspective.

21 - 114 - Tg

21 - 171 - Thanks, I love history and believe that it is important for us all to understand our past so that we can learn from our mistakes. This article gave me heaps of info. Thanks for being willing to take the time to help others learn about our past. It truly is amazing - Anonymous

19 - 18 - Thanks for an astute summary. I am currently reading Barbara Tuchman's book on this period "The Proud Tower". What an amazing era. Such hubris. Such arrogance. Unfortunately, as always those taking the risks and making idiot decisions did not pay the bill. In fact they became more wealthy out of the war. What do you thing the next period in world history will bring? At least today there is no irrational optimism about the future as at the end of the nineteenth century. Maybe that is a start?

19 - 19 - Very interesting and insightful. Perhaps an article on the Lost Generation would be a good companion piece. I believe WW2 broke out in 1939, not 1940 (unless one counts the Asian-Pacific theater in which hostilities began in 1937).

19 - 20 - The end of any era in history severely challenges a culture's values. If you were to question national pride or absolute duty to your country prior to WWI you would likely have been executed. This shows just how entrenched cultural values can be. That being said, any prediction of what the next era in our history will be would be offensive to just about anyone who read it. I will guess that a civil war in England will be the event at which historians in the future will determine as the marker for the end of the Modern Era. I tend to wish there was more irrational optimism about the future in our time. WWI was a tremendous event matched only by the 30 years war or the Plague in its destructiveness. Maybe quite a bit of our cultural energy was destroyed as a result of the Great War. Thank you for the book recommendation, I'll definitely give it a look.

19 - 21 - Thanks for the suggestion! I will add that to my list of future articles. The great thing about writing these is that in doing the research you find so many ideas for new articles. Fixed the date too, thank you RT.

19 - 136 - Hitler was not good!

19 - 173 - What is a troy a reference to?

18 - 17 - This explanation is an oft-repeated myth. The bedrock is deeper below the surface in the areas below Canal Street than it is in region from the Flatiron district up to 42nd between. See http://observer.com/2012/01/uncanny-valley-the-real-reason-there-are-no-skyscrapers-in-the-middle-of-manhattan/

18 - 198 - Engaging read! This post brilliantly unpacks the geological foundations of NYC, underpinning its architectural prowess. It's the unseen hero of the city's skyline.

17 - 70 - A very interesting piece of history.

17 - 73 - Glad you enjoyed it!

17 - 74 - Love reading history raise of christianity.

17 - 99 - wow! so interesting. helped so much!

17 - 100 - is this site credible?

17 - 102 - It is as credible as the available source material. I list all references on each article. If you have a different perspective please feel free to email me or leave a comment. Thanks for reading!

17 - 107 - Thanks for this information. This helped me a lot! :D

17 - 108 - Thanks for this information. This helped me a lot! :D

17 - 111 - HI

17 - 115 - Very interesting information. How the living religion, Christianity has spread around the world like this miracle is an open proof that JESUS is living and He changes lives and a help in times of helplessness.

17 - 118 - Constantine was a jerk

17 - 120 - thanks

17 - 139 - Very nice article I am a student and this helped me learn a lot in the 6th grade!

17 - 144 - Very Good!

17 - 142 - Very interesting about his conversion to Christianity

17 - 143 - learning heaps

17 - 146 - Interesting

17 - 147 - Constantine is a very interesting bloke. Thanks to all the chaps at Classic History!

17 - 148 - thanks

17 - 156 - This is a great resource of knowledge for my kindergarteners!!!

17 - 158 - Thanks Ian! I'm happy it has helped!

17 - 159 - I love this cite! very credible 10/10 great resource for some fun reading!

17 - 175 - love it !!!

17 - 185 - i dont like this cause it didnt talk about MLK

17 - 206 - ????????????

17 - 205 - stupid

17 - 202 - You are so fake. There is no god. Shut up, just, shut up!

17 - 207 - Very good

17 - 211 - All thanks to Jesus,for his mercy

17 - 216 - this app is so amazing it js makes me want to slap eian

16 - 16 - Meine Mutter war eine geborene Bach.Besteht Event.eine Verbindung zu Johann Sebastian?Ich wurde es unbedingt wissen wollen .Irgend wo ist mir das ubermittelt worden.Bitte helfen Sie mir.Danke im Voraus-

16 - 222 - poah rein in die futterluke

15 - 182 - I'd like to use the above graphic as a sidebar to an upcoming equinox post at EarthSky. My article informs the reader of the intriguing fact that the tip of a shadow stick (gnomon) follows a straight (west-to-east) path on the day of an equinox. If given permission, I plan to credit the graphic to Classic History and to provide a link to this Eratosthenes page. Thank you for your consideration!

15 - 183 - Bruce, Yes please feel free to use anything you want so long as you reference this website as a source. Here is a slightly larger resolution image. Thanks for reading!

13 - 166 - Please include date of publication as I am trying to cite this article for school

12 - 10 - I was intrigued by Origin of Romanticism, how it changed its meaning over in a short span of time. From its lovers escapade into beautiful spots of nature to non- tangent expression of emotion and dramatism. thank you very much for this insight. grateful - sheera Betnag

12 - 69 - And wonder how it might change in the future as well. Glad you enjoyed the article and thank you for reading Sheera.

12 - 150 - This post was truly worthwhile to read. I wanted to say thank you for the key points you have pointed out as they are enlightening.

12 - 208 - As a Chinese, I've got the origin of romance! Thank u a lot.

9 - 0 - test'

5 - 151 - how should i reference this website?

5 - 153 - You could use Source: www.ClassicHistory.net Author: Thomas Acreman

4 - 7 - Keep on writing, great job!

4 - 8 - Congratulations. Agrees with the Welsh versions I was taught at school in the 1930s and 40s and what I read and gathered afterwards. I am now interested in finding out how much effect would 350 year of Roman rule have had on the Britons and why was it that the Romano Britons were so complacent and lax to be overtaken by the pagan immigrant settlers from Saxony in c400B.C.

4 - 9 - Thanks so much! I plan to keep on writing for years. My goal is to write at least one article per month.

4 - 78 - Thanks Gordon. I should have read my own title, where it was named Britain.

4 - 77 - "The island nation currently known as England?!" That's funny; I live here, and we call it Great Britain.

4 - 131 - Misspellings: "every forrest and hillside" (forest) "the furry of battle" (fury) "He employed them all to weather their captivity with bravery and courage, and to be strong men and women" (implored? impelled?) "an ivory thrown" (throne)

4 - 132 - Thanks JD. This is one of the first articles I wrote for this website and I really need to rewrite it.

4 - 167 - This story does, at least, acknowledge that the tale of Julius Caesar conquering Britain is not true! JC was ejected more than once. It was Cartimandua who betrayed Caradoc.. in the time of Claudius. BTW… No celts in Britain which was named for Brutus, grandson of Anaeas of Troy. Anaeas also features in the story of the founding of Rome. I.e., the peoples were related. The Cymry were not ‘primitive’!

3 - 1 - I love visiting the cross but, there's one thing that drives me nuts. Vietnam was not a war it was an armed conflict, not one of the 5 presidents that were in office during this time [1945 to 1972] did NOT declare war on the Viet Cong nor on North Vietnam.

3 - 3 - Are small weddings allowed Infront of the cross ?

3 - 4 - What camera was used here?

3 - 2 - Indeed, but the purpose of the cross is to remember those who answered their call to service and how much better the world is for their sacrifice. To that goal I think the cross does a fine job.

3 - 5 - I am not affiliated with Sewanee in any way but yes, I have seen a wedding there. It looked very peaceful and beautiful. There is a link to their website on this page which would be a good place to look for a contact number for the University.

3 - 6 - I believe I just used an old iPhone 4s for both of these photos.

3 - 109 - Why are those who severed in the Civil War not memorialized as well?

3 - 110 - Because the cross was originally built to memorialize those who served and died in World War I. Plaques were only added for those who served in wars after WWI. It was ultimately decided that the cross would only serve as a memorial for those who served and died in wars during the 20th century. From The University of the South: "Sewanee’s Memorial Cross honors the students and alumni of the University of the South and the Sewanee Military Academy and the citizens of Franklin County who fought and those who lost their lives in service to their country in the wars of the last century."

3 - 161 - Can someone in a wheelchair be able to get to the cross fairly easy?

3 - 162 - Yes, parking is available at the cross and the walkway to the cross is only slightly uphill.

2 - 0 - Nice article. The lake actually rarely freezes and only enough to walk on less than once every 10 years and only for a few days. In 2006 it was 29 days but otherwise it is clear and the ferries run year round.

-1 - 66 - Thanks for sharing your thoughts on History. Regards

-1 - 67 - I enjoyed your article on Charles Martel. Thank you for maintaining this beautiful site!

-1 - 68 - Thank you! I enjoyed researching and writing that one too. Thanks for reading and Merry Christmas.

-1 - 193 - Thanks very much for this mentally engaging, attention-grabbing articles. This content is right up mu intellectual alley, and I'll be a regular frequenter.

-100024 - 106 - test comment!! ©

The Battle of Tours - 732 AD Comments:

Leave a Reply

Your email address is not required and will not be published.

If you would like to leave a comment or a reply, please answer this security question:

- Ancient History

Charles Martel and the defense of Europe at the Battle of Tours

What if one man’s decision could change the fate of an entire continent? That is exactly what happened in the eighth century, when Charles Martel, known as 'The Hammer', faced the Muslim forces of the Umayyad Caliphate as they swept across the Iberian Peninsula and into the heart of the Frankish kingdom.

At the subsequent Battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel would define the future of Europe for the next 1000 years.

So, why did this battle matter so much, and how did he defeat an enemy that seemed unstoppable?

Martel’s rise to power among the Franks

Following the fall of the Roman Empire in western Europe, the Germanic tribe known as the Franks took control of the region of modern France, known as Gaul.

The leading Frankish family was known as the Merovingians, and they began a dynasty that ruled over the Franks from around 476.

Historians consider them to be the first kings of France. The dynasty's name came from Merovech, the grandfather of Clovis I, who united the Frankish tribes and expanded their territory across Gaul.

However, over the next two hundred years, the power of Merovingian kings waned, with authority shifting to their key military commanders, known as the ‘mayor of the palace’, who acted as the real rulers of the Frankish realms.

Charles Martel was born around 688 into a powerful Frankish family with deep political connections.

He was the illegitimate son of Pepin of Herstal, the Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia, and his concubine Alpaida.

By this time, the Frankish kingdom was fragmented and in disarray. After Pepin's death in 714, the Frankish kingdom fell into internal strife.

There was a power struggle between Pepin's widow, Plectrude, and various noble factions.

Among this, the young Charles found himself imprisoned by Plectrude in an attempt to secure the throne for her grandson, Theudoald.

However, by 715, he managed to escape and began to gather support from key Austrasian nobles who opposed Plectrude's rule.

Thanks to some canny political maneuvering, Charles Martel gradually consolidated his influence over the Franks.

By 718, after a series of battles, including a decisive victory against the Neustrians at Amblève, he had solidified his position as the Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia.

In contrast to his rivals, Charles pursued a strategy that combined diplomacy with outright military aggression.

He understood that the only path to stability lay in unifying the fractured Frankish territories under his leadership.

By 723, Charles Martel had effectively united Austrasia and Neustria under his rule.

How Charles Martel secured his power

To consolidate his new power, Martel implemented a policy of distributing lands, or benefices, to his most loyal followers, a tactic that ensured their continued support and reinforced the military strength of his rule.

As such, he effectively tied the noble class to his leadership and created a new social order that depended on his authority.

This approach enabled him to build a robust network of allies who would help maintain the stability of his reign.

Also, by 730, he had reorganized the Frankish army, focusing on creating a disciplined and heavily armored cavalry.

This transformation allowed his forces to maneuver quickly and strike decisively against enemies.

In addition, he encouraged the use of stirrups and better armor, which improved the combat effectiveness of his troops.

To strengthen his hold on power, Charles Martel also cultivated key alliances within the Church .

The Frankish Church held significant influence over the populace, and Charles recognized the importance of gaining its support.

He sought the backing of influential bishops and abbots. He secured their loyalty by granting them protection and additional lands.

Through the Church’s support, he gained both moral authority and additional resources to fund his campaigns.

Moreover, Charles strategically placed his own family members in positions of power within the Church.

Additionally, Martel launched campaigns against rebellious regions, such as the Duchy of Aquitaine in 731, which had resisted Frankish control for years.

In his dealings with other European powers, he appears to have balanced aggression with diplomacy.

For instance, his alliance with the Lombards against the Muslims demonstrated his willingness to work with traditional enemies to achieve his strategic goals.

While through a series of campaigns from 718 to 732, he pushed back the Frisians, the Alemanni, and the Bavarians, bringing these territories under Frankish control.

The Battle of Tours (732)

Out of all of the battles that Martel fought, it was the one at Tours in 732 that has become the most famous.

It occurred near the city of Tours, in present-day France, at a time when Islamic expansion threatened to overrun much of Western Europe.

Before the confrontation, the Umayyad Caliphate had rapidly expanded its territory across North Africa and into the Iberian Peninsula, with the intent to continue its push into Frankish lands.

Tensions had been building for years, with Umayyad raiders conducting raids into southern France.

Charles Martel had prepared his forces for a confrontation that would determine the fate of Western Europe.

Charles Martel had chosen a defensive strategy and positioned his forces on a wooded, elevated plateau to protect them from the superior mobility of the Muslim cavalry.

By employing a solid shield wall formation, Martel's infantry absorbed and repelled wave after wave of Umayyad assaults.

When enemy troops withdrew, exhausted, Martel ordered his men to hold their ground rather than pursue.

This apparently confused his opponents, who expected a more conventional battle.

Moreover, Martel capitalized on the element of surprise and patience, waiting until the Umayyad forces grew weary from repeated attacks.

At a crucial moment, Martel launched a counterattack that led to the death of their leader, Abdul Rahman Al-Ghafiqi.

This loss caused disarray among the Muslim ranks, forcing them to retreat from France entirely.

The significance of the Battle of Tours lay in its decisive role in halting the northern advance of Islamic forces.

Had the Umayyad army succeeded, the cultural and religious future of Western Europe could have been irrevocably changed.

Ultimately, the battle prevented the Islamic expansion from gaining a foothold beyond the Pyrenees and preserved the Christian dominance of Western Europe.

In the aftermath of the victory, Charles Martel earned the title ‘The Hammer’, a reflection of his reputation as a relentless defender of Christendom.

For years following the battle, Muslim forces ceased their attempts to advance further into Frankish territory, focusing instead on consolidating their control in the Iberian Peninsula.

Impact on the Franks and the rise of the Carolingians

Charles Martel's military victories and political reforms laid the groundwork for the Carolingian Empire, which would reach its zenith under his grandson, Charlemagne.

By strengthening the central authority of the Frankish state, Martel created a more unified and resilient kingdom.

In addition, Martel’s successes gave the Frankish kingdom a newfound sense of stability and purpose, allowing it to transition from a fragmented collection of tribes into a cohesive and powerful realm.

The political and social changes Charles Martel implemented by redistributing land to his most loyal followers, creating a network of vassals who owed their allegiance directly to him.

This policy of granting benefices ensured that the nobility remained dependent on the king for their wealth and status.

Over time, this practice contributed to the emergence of feudalism , as land became the primary currency of political loyalty and military service.

In particular, Martel’s need to sustain a professional, mounted warrior class, or knights , created a hierarchical structure based on land ownership and personal loyalty.

After Charles Martel’s death in 741his sons, Carloman and Pepin the Short, succeeded him.

Carloman took control of the eastern Frankish lands, while Pepin ruled the western territories.

By 747, Carloman retired to a monastery, leaving Pepin as the sole ruler. In 751, Pepin took a decisive step by deposing the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, and having himself anointed king with the Church’s blessing.

This act marked the formal beginning of the Carolingian Dynasty and demonstrated the successful continuation of Charles Martel’s policies of consolidation and alliance-building.

Under Pepin’s rule, and later that of his son Charlemagne , the Carolingian Empire would reach its height, achieving the political and cultural aspirations set in motion by Charles Martel’s visionary leadership.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Battle of Tours

The Battle of Tours (October 10, 732), often called Battle of Poitiers and also called in Arabic بلاط الشهداء (Balâṭ al-Shuhadâ’) The Court of Martyrs [5] was fought near the city of Tours, close to the border between the Frankish realm and the independent region of Aquitaine. The battle pitted Frankish and Burgundian. [6] [7] forces under Austrasian Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel against an army of the Umayyad Caliphate led by ‘Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, Governor-general of al-Andalus. The Franks were victorious, ‘Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi was killed, and Martel subsequently extended his authority in the south. Ninth-century chroniclers, who interpreted the outcome of the battle as divine judgment in his favor, gave Charles the nickname Martellus ("The Hammer"), possibly recalling Judas Maccabeus ("The Hammerer") of Maccabean revolt . [8] Details of the battle, including its exact location and the exact number of combatants, cannot be determined from accounts that have survived. [9]

As later chroniclers increasingly came to praise Charles Martel as the champion of Christianity , pre-twentieth century historians began to characterize this battle as being the decisive turning point in the struggle against Islam . "Most of the eighteen and nineteenth century historians, like Gibbon , saw Poitiers (Tours), as a landmark battle that marked the high tide of the Muslim advance into Europe." [10] Leopold von Ranke felt that "Poitiers was the turning point of one of the most important epochs in the history of the world." [11]

- 1.1 The Opponents

- 1.2 Muslim conquests from Hispania

- 1.3 Eudes' appeal to the Franks

- 1.4 Advance toward the Loire

- 2.1 Preparations and maneuver

- 2.2 Engagement

- 2.3 The battle turns

- 2.4 Following day

- 2.5 Contemporary accounts

- 2.6 Strategic analysis

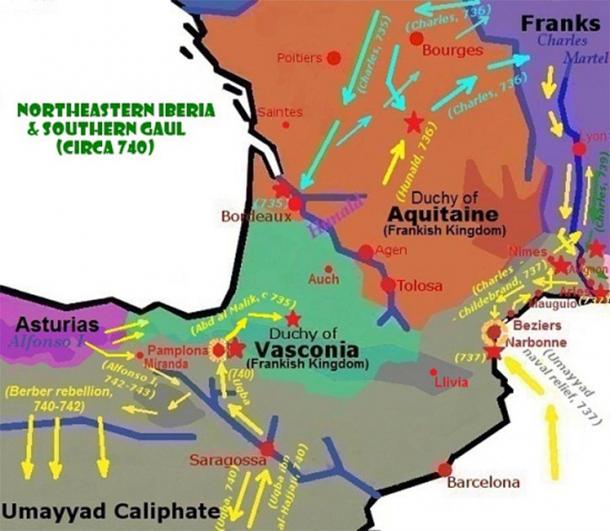

- 3.1 Umayyad retreat and second invasion

- 3.2 Advance to Narbonne

- 3.3 Carolingian Dynasty

- 4 The last Umayyad invasions of Gaul

- 5.1 In Western history

- 5.2 In Muslim history

- 6.1 Supporting the significance of Tours as a world-altering event

- 6.2 Objecting to the significance of Tours as a world-altering event

- 7 Conclusion

- 9 References

- 10 External links

While modern historians are divided as to whether or not the victory was responsible—as Gibbon and his generation of historians claimed—for saving Christianity and halting the conquest of Europe by Islam , the battle helped lay the foundations for the Carolingian Empire , and Frankish domination of Europe for the next century. "The establishment of Frankish power in western Europe shaped that continent's destiny and the Battle of Tours confirmed that power." [12] In myth the battle became defining moment in European history, even though its historical reality may have been more of the nature of a border skirmish. Nevertheless, following the Battle of Tours, Europe to a large extent defined itself—over and against the Muslim world. On the other hand, the formation of the Carolingian Empire a single entity uniting religion and empire may have borrowed from Islam , which upheld that very ideal.

The battle followed 20 years of Umayyads conquests in Europe, beginning with the invasion of the Visigoth Christian Kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula in 711 C.E. and progressing into the Frankish territories of Gaul, former provinces of the Roman Empire . Umayyad military campaigns had reached northward into Aquitaine and Burgundy, including a major battle at Bordeaux and a raid on Autun. Martel's victory is believed by some historians to have stopped the northward advance of Umayyad forces from the Iberian Peninsula, and to have preserved Christianity in Europe during a period when Muslim rule was overrunning the remains of the old Roman and Persian Empires. [13] Others have argued that the battle marked only the defeat of a raid in force and was not a watershed event. [14]

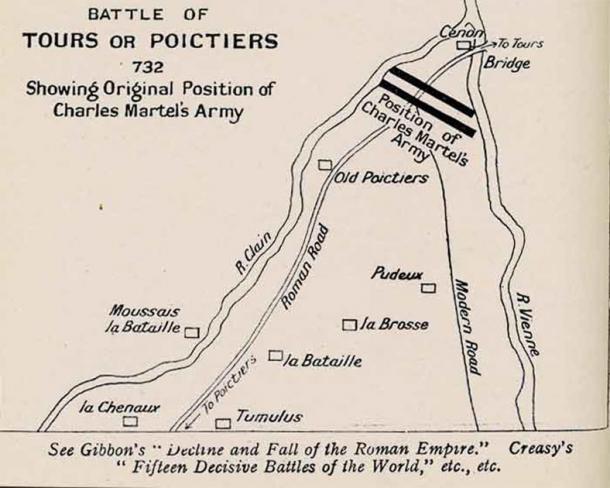

The exact location of the Battle of Tours remains unknown. Surviving contemporary sources, both Muslim and Western, agree on certain details while disputing others. Most historians assume that the two armies met where the rivers Clain and Vienne join between Tours and Poitiers. The number of troops in each army is not known. Drawing on non-contemporary Muslim sources Creasy describes the Umayyad forces as 80,000 strong or more. Writing in 1999, Paul K. Davis estimates the Umayyad forces at 80,000 and the Franks at about 30,000, while noting that modern historians have estimated the strength of the Umayyad army at Tours at between 20–80,000. [15] Edward J. Schoenfeld (rejecting the older figures of 60–400,000 Umayyad and 75,000 Franks) contends that "estimates that the Umayyads had over fifty thousand troops (and the Franks even more) are logistically impossible." [16] Another modern military historian, Victor Davis Hanson, believes both armies were of roughly the same size, about 30,000 men. [17] Modern historians may be more accurate than the medieval sources as the modern figures are based on estimates of the logistical ability of the countryside to support these numbers of men and animals. Both Davis and Hanson point out that both armies had to live off the countryside, neither having a commissary system sufficient to provide supplies for a campaign. Losses during the battle are unknown but chroniclers later claimed that Martel's force lost about 1500 while the Umayyad force was said to have suffered massive casualties of up to 375,000 men. However, these same casualty figures were recorded in the Liber pontificalis for Duke Odo of Aquitaine's victory at the Battle of Toulouse (721). Paul the Deacon, correctly reported in his Historia Langobardorum (written around the year 785) that the Liber pontificalis mentioned these casualty figures in relation to Odo's victory at Toulouse (though he claimed that Charles Martel fought in the battle alongside Odo), but later writers, probably "influenced by the Continuations of Fredegar, attributed the Saracen casualties solely to Charles Martel, and the battle in which they fell became unequivocally that of Poitiers." [18] The Vita Pardulfi, written in the middle of the eighth century, reports that after the battle ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân's forces burned and looted their way through the Limousin on their way back to Al-Andalus, which implies that they were not destroyed to the extent imagined in the Continuations of Fredegar. [19]

The Opponents

The Invasion of Hispania, and then Gaul, was led by the Umayyad Dynasty (Arabic: بنو أمية banū umayya / الأمويون al-umawiyyūn ; also "Umawi," the first dynasty of caliphs of the Islamic empire after the reign of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs ( Abu Bakr , Umar , Uthman , and Ali ) ended. The Umayyad Caliphate, at the time of the Battle of Tours, was perhaps the world’s foremost military power. Great expansion of the Caliphate occurred under the reign of the Umayyads. Muslim armies pushed across North Africa and Persia , through the late 600s, expanding the borders of the empire from the Iberian Peninsula, in the west, to what is today Pakistan , in the east. Forces led by Tariq ibn-Ziyad crossed Gibraltar and established Muslim power in the Iberian peninsula, while other armies established power far away in Sind, in what is now the modern state of Pakistan. The Muslim empire under the Umayyads was now a vast domain that ruled a diverse array of peoples. It had destroyed what were the two former foremost military powers, the Sassanid Empire , which it absorbed completely, and the Byzantine Empire , most of which it had absorbed, including Syria , Armenia and North Africa , although Leo the Isaurian successfully defended Anatolia at the Battle of Akroinon (739) in the final campaign of the Umayyad dynasty. [20]

The Frankish realm under Charles Martel was the foremost military power of Western Europe. It consisted of what is today most of Germany , the low countries, and part of France (Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy). The Frankish realm had begun to progress towards becoming the first real imperial power in Europe since the fall of Rome, as it struggled against the hordes of barbarians on its borders, such as the fierce Saxons, and internal opponents such as Eudes, the Duke of Aquitaine.

Muslim conquests from Hispania

The Umayyad troops, under Al-Samh ibn Malik, the governor-general of al-Andalus , overran Septimania by 719, following their sweep up the Iberian Peninsula. Al-Samh set up his capital from 720 at Narbonne, which the Moors called Arbūna. With the port of Narbonne secure, the Umayyads swiftly subdued the largely unresisting cities of Alet, Béziers, Agde, Lodève, Maguelonne, and Nîmes, still controlled by their Visigoth counts. [21]

The Umayyad campaign into Aquitaine suffered a temporary setback at the Battle of Toulouse (721), when Duke Odo of Aquitaine (also known as Eudes the Great) broke the siege of Toulouse, taking Al-Samh ibn Malik's forces by surprise and mortally wounding the governor-general Al-Samh ibn Malik himself. This defeat did not stop incursions into old Roman Gaul, as Arab forces, soundly based in Narbonne and easily resupplied by sea, struck eastwards in the 720s, penetrating as far as Autun in Burgundy (725).

Threatened by both the Umayyads in the south and by the Franks in the north, in 730 Eudes allied himself with the Berber emir Uthman ibn Naissa, called "Munuza" by the Franks, the deputy governor of what would later become Catalonia . As a gage, Uthman was given Eudes's daughter Lampade in marriage to seal the alliance, and Arab raids across the Pyrenees , Eudes's southern border, ceased. [22]

However, the next year, Uthman rebelled against the governor of al-Andalus , ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân, who quickly crushed the revolt and directed his attention against Eudes. ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân had brought a huge force of Arab heavy cavalry and Berber light cavalry, plus troops from all provinces of the Caliphate, in the Umayyad attempt at a conquest of Europe north of the Pyrenees. According to one unidentified Arab , "That army went through all places like a desolating storm." Duke Eudes (called "King" by some), collected his army at Bordeaux, but was defeated, and Bordeaux was plundered. The slaughter of Christians at the Battle of the River Garonne was evidently horrific; the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 [23] commented, " solus Deus numerum morientium vel pereuntium recognoscat ," ("God alone knows the number of the slain"). [24] The Umayyad horsemen then utterly devastated that portion of Gaul, their own histories saying the "faithful pierced through the mountains, trampled over rough and level ground, plundered far into the country of the Franks, and smote all with the sword , insomuch that when Eudo came to battle with them at the River Garonne, he fled."

Sir Edward Creasy said, (incorporating verses from Robert Southey 's poem " Roderick, the Last of the Goths "):

And so, after smashing Eudes and laying waste in the south, the Umayyad cavalry advanced north, pursuing the fleeing Eudes, and looting, and destroying all before them.

Eudes' appeal to the Franks

Eudes appealed to the Franks for assistance, which Charles Martel only granted after Eudes agreed to submit to Frankish authority.

It appears as if the Umayyads were not aware of the true strength of the Franks. The Umayyad forces were not particularly concerned about any of the Germanic tribes, including the Franks, and the Arab Chronicles, the history of that age, show that awareness of the Franks as a growing military power only came after the Battle of Tours.

Further, the Umayyads appear not to have scouted northward for potential foes, for if they had, they surely would have noted Charles Martel as a force to be reckoned with in his own account, due to his thorough domination of Europe from 717: this might have alerted the Umayyads that a real power led by a gifted general was rising in the ashes of the Western Roman Empire.

Advance toward the Loire

In 732, the Umayyad advance force was proceeding north toward the River Loire having outpaced their supply train and a large part of their army. Essentially, having easily destroyed all resistance in that part of Gaul, the invading army had split off into several raiding parties, while the main body advanced more slowly.

The Umayyad attack was likely so late in the year because many men and horses needed to live off the land as they advanced; thus they had to wait until the area's wheat harvest was ready and then until a reasonable amount of the harvest was threshed (slowly by hand with flails) and stored. The further north, the later the harvest is, and while the men could kill farm livestock for food, horses cannot eat meat and needed grain as food. Letting them graze each day would take too long, and interrogating natives to find where food stores were kept would not work where the two sides had no common language.

A military explanation for why Eudes was defeated so easily at Bordeaux and at the Battle of the River Garonne after having won 11 years earlier at the Battle of Toulouse is simple. At Toulouse, Eudes managed a basic surprise attack against an overconfident and unprepared foe, all of whose defensive works were aimed inward, while he attacked from the outside. The Umayyad cavalry never got a chance to mobilize and meet him in open battle. As Herman de Carinthia wrote in one of his translations of a history of al-Andalus, Eudes managed a highly successful encircling envelopment which took the attackers totally by surprise — and the result was a chaotic slaughter of the Muslim cavalry.

At Bordeaux, and again at the Battle of the River Garonne, the Umayyad cavalry were not taken by surprise, and given a chance to mass for battle, this led to the devastation of Eudes's army, almost all of whom were killed with minimal losses to the Muslims. Eudes's forces, like other European troops of that era, lacked stirrups, and therefore had no armored cavalry. Virtually all of their troops were infantry. The Umayyad heavy cavalry broke the Christian infantry in their first charge, and then slaughtered them at will as they broke and ran.

The invading force went on to devastate southern Gaul. A possible motive, according to the second continuator of Fredegar, was the riches of the Abbey of Saint Martin of Tours, the most prestigious and holiest shrine in Western Europe at the time. [25] Upon hearing this, Austrasia's Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, collected his army and marched south, avoiding the old Roman roads and hoping to take the Muslims by surprise. Because he intended to use a phalanx, it was essential for him to choose the battlefield. His plan — to find a high wooded plain, form his men and force the Muslims to come to him — depended on the element of surprise.

Preparations and maneuver

From all accounts, the invading forces were caught entirely off guard to find a large force, well disposed and prepared for battle, with high ground, directly opposing their attack on Tours. Charles had achieved the total surprise he hoped for. He then chose to begin the battle in a defensive, phalanx-like formation. According to the Arabian sources the Franks drew up in a large square, with the trees and upward slope to break any cavalry charge.

For seven days, the two armies watched each other with minor skirmishes. The Umayyads waited for their full strength to arrive, which it did, but they were still uneasy. A good general never likes to let his opponent pick the ground and the conditions for battle. 'Abd-al-Raḥmân, despite being a good commander, had managed to let Martel do both. Furthermore, it was difficult for the Umayyads to judge the size of the army opposing them, since Martel had used the trees and forest to make his force appear larger than it probably was. Thus, 'Abd-al-Raḥmân recalled all his troops, which did give him an even larger army - but it also gave Martel time for more of his veteran infantry to arrive from the outposts of his Empire. These infantry were all the hope for victory he had. Seasoned and battle hardened, most of them had fought with him for years, some as far back as 717. Further, he also had levies of militia arrive, but the militia was virtually worthless except for gathering food, and harassing the Muslims. (Most historians through the centuries have believed the Franks were badly outnumbered at the onset of battle by at least 2-1) Martel gambled everything that ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân would in the end feel compelled to battle, and to go on and loot Tours. Neither of them wanted to attack - but Abd-al-Raḥmân felt in the end obligated to sack Tours, which meant literally going through the Frankish army on the hill in front of him. Martel's decision to wait in the end proved crucial, as it forced the Umayyads to rush uphill, against the grade and the woods, which in and of themselves negated a large part of the natural advantages of a cavalry charge.

Martel had been preparing for this confrontation since Toulouse a decade before. He was well aware that if he failed, no other Christian force remained able to defend western Christianity. But Gibbon believes, as do most pre and modern historians, that Martel had made the best of a bad situation. Though outnumbered and depending on infantry, without stirrups in wide use, Martel had a tough, battle hardened heavy infantry who believed in him implicitly. Martel had the element of surprise, and had been allowed to pick the ground.

The Franks in their wolf and bear pelts were well dressed for the cold, and had the terrain advantage. The Arabs were not as prepared for the intense cold of an oncoming northern European winter, despite having tents, which the Franks did not, but did not want to attack a Frankish army they believed may have been numerically superior—according to most historians it was not. Essentially, the Umayyads wanted the Franks to come out in the open, while the Franks, formed in a tightly packed defensive formation, wanted them to come uphill, into the trees, diminishing at once the advantages of their cavalry. It was a waiting game which Martel won: The fight began on the seventh day, as Abd er Rahman did not want to postpone the battle indefinitely with winter approaching.

‘Abd-al-Raḥmân trusted the tactical superiority of his cavalry, and had them charge repeatedly. This time the faith the Umayyads had in their cavalry, armed with their long lances and swords which had brought them victory in previous battles, was not justified. The Franks, without stirrups in wide use, had to depend on unarmoured foot soldiers.

In one of the instances where medieval infantry stood up against cavalry charges, the disciplined Frankish soldiers withstood the assaults, though according to Arab sources, the Arab cavalry several times broke into the interior of the Frankish square. "The Moslem horsemen dashed fierce and frequent forward against the battalions of the Franks, who resisted manfully, and many fell dead on either side." [26]