- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Controversy Accompanies Historic Papal Visit To U.K.

Sylvia Poggioli

Children arrive for a rehearsal at Glasgow's Bellahouston Park ahead of Thursday's visit by Pope Benedict XVI. The pope will celebrate Mass in the park following his visit to Edinburgh, where he will be met by Queen Elizabeth II. Jeff J. Mitchell/Getty Images hide caption

The first state visit by a pope to Britain comes at a low point in relations between Catholics and Anglicans and under the weight of the clerical sex abuse crisis.

Pope Benedict XVI arrives in Scotland on Thursday morning to spend four days in Britain -- the first visit by a pope in nearly 30 years and the first papal state visit since King Henry VIII broke with Rome in 1534 over a divorce.

The trip includes a meeting with Queen Elizabeth in Scotland, a speech in Westminster Hall, an ecumenical service with the archbishop of Canterbury and the beatification of a 19th century Anglican who converted to Catholicism.

Looming over the visit are 400 years of religious tensions and more contemporary divisions.

Particular Challenges For Benedict

Protests are being planned by gay activists, secularists, advocates of female ordination and militant atheists -- some of whom have called for Benedict’s arrest on charges of covering up sex abuse of minors by priests.

Pope Benedict XVI (right) prays during his weekly general audience Wednesday at the Vatican. Benedict takes his campaign to revive Christianity in an increasingly secular Europe to Britain on Thursday. He faces a daunting task in a nation largely at odds with his policies and where disgust over the church sex abuse scandal runs high. Alessandra Tarantino/AP hide caption

Pope Benedict XVI (right) prays during his weekly general audience Wednesday at the Vatican. Benedict takes his campaign to revive Christianity in an increasingly secular Europe to Britain on Thursday. He faces a daunting task in a nation largely at odds with his policies and where disgust over the church sex abuse scandal runs high.

Vatican spokesman the Rev. Federico Lombardi is unfazed.

“There have always been protests by some groups during papal visits,” he says. “There will be more groups on this trip -- such as atheists and anti-papists."

Lombardi adds, “It’s normal in a pluralistic society like the British one. We are not worried because we believe the media has overblown reality."

But a visit to such a pluralistic society is particularly challenging for a pope who has set as his mission the re-evangelization of Europe.

Robert Mickens, Vatican correspondent for the British Catholic weekly The Tablet, says the pope’s main goal is "to try to help make a space in society for religion, for faiths."

"It is very clear that [the pope] believes that the Catholic Church and Catholics within that church have been too lax in presenting the faith in reasoned, rational, argued terms that can stand up toe to toe in the arena of ideas," Mickens says.

Weekly church attendance among Britain’s 5 million Catholics has been dropping steadily, as it has elsewhere in Europe. In fact, many tickets to papal events -- which unusually carry a price tag -- have gone unsold.

Anglican-Catholic Relations A Key Issue

Just 11 months ago, the Vatican stunned the Church of England when -- without consulting the archbishop of Canterbury -- it offered to take in dissident Anglicans angered over their church’s consecration of female and homosexual bishops.

Anglican critics see it as part of a centuries-old campaign by Rome to annex the Anglican Church.

Vatican analyst Marco Politi says Catholic-Anglican relations are at their lowest point in recent history, as the Vatican tries to woo Anglican conservatives.

“All the issues of modernity which already in the Catholic Church the pope is fighting are just the reasons for which he is embracing this traditionalist part of the Anglicans,” Politi explains.

Benedict has the dubious precedent of having caused offense during several of his foreign travels: his remarks in Germany describing Islam as violent, which outraged Muslims; and his claim on his way to Africa that the use of condoms spreads AIDS.

Some Vatican watchers say Benedict’s decision to beatify Cardinal John Henry Newman, a priest in the Church of England who converted to Catholicism in the 19th century, could further strain relations with Anglicans.

The pope has described the decision as an act of ecumenism. But Politi points out that Benedict has always upheld the primacy of Catholicism -- “that the only real church is the Catholic Church, and that the Protestant churches for him are not real churches but only Christian communities.”

God's Somewhat Surprising 'Rottweiler'

Benedict will not receive the warm welcome given to his charismatic predecessor Pope John Paul II in 1982. Many of the British media have been openly hostile to the papal visit, which is costing British taxpayers some $18 million.

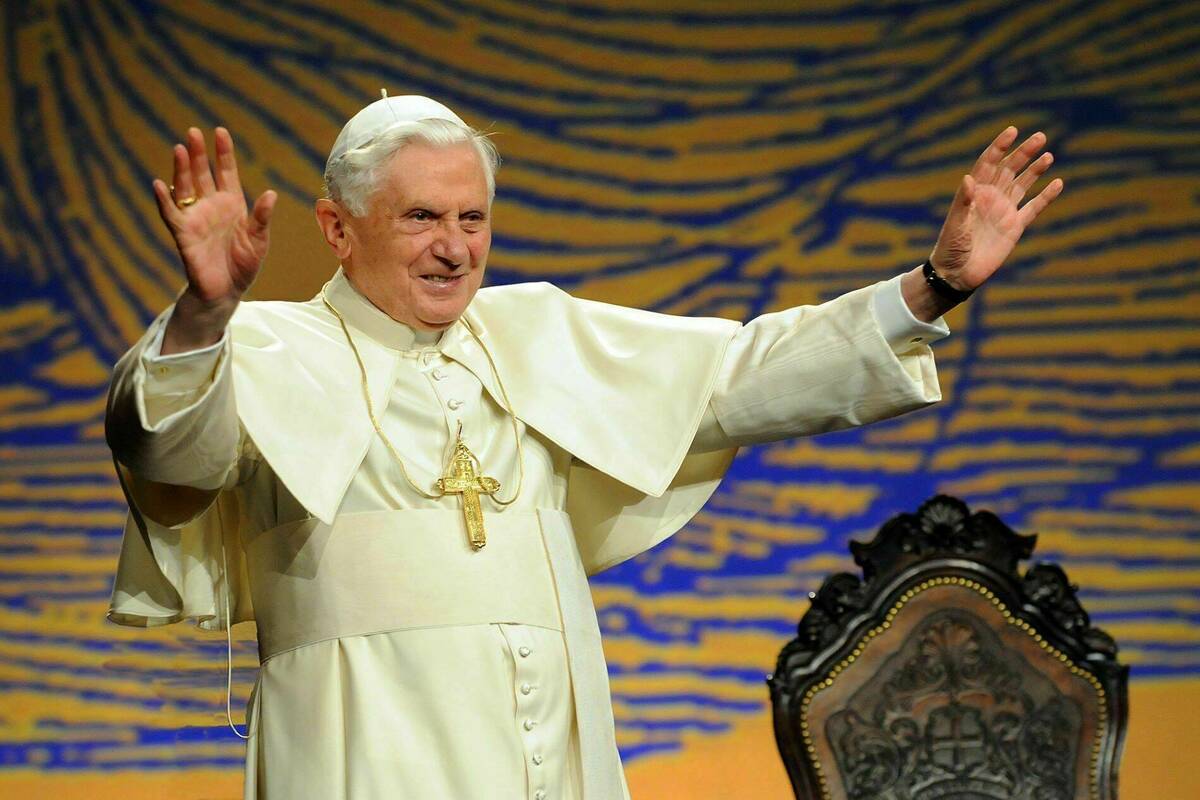

But The Tablet 's correspondent Mickens says Britons may be surprised when they see firsthand the man described as "God’s Rottweiler." “They will see someone who speaks with a lilting voice, soft-spoken, and he’ll look sweet and have white hair," Mickens says.

“But in the end," he adds, "the words will remain and he is going to have to choose his words carefully on this visit, words that are said with great kindness in the voice but really have a sharp bite to them on the page."

Related NPR Stories

The two-way, before state visit, pope benedict xvi aide analogizes u.k. to 'third world country'.

Share this on:

Why is pope benedict xvi visiting britain.

- Pope doesn't travel often; British opinion of him ranges from indifference to hostility

- Pope relishes arguing for religion in such a secular society, says expert

- Expert: Pope wants to reach out to Anglicans

- Benedict often benefits from foreign travel, coming out more popular, says expert

London, England (CNN) -- As the United Kingdom braces to receive one of the best-known and most controversial figures on the planet, Pope Benedict XVI, a question hangs over the state visit: Why is he coming?

The leader of the world's 1 billion-plus Catholics does not particularly like to travel, Benedict biographer David Gibson says.

Since a high-profile visit to Israel and the Palestinian territories nearly a year-and-a-half ago, he's gone only to a handful of small countries not far from Rome -- racking up nothing like the number of air miles logged by his predecessor, Pope John Paul II.

And the United Kingdom is not a Catholic country. On the contrary, Britain's break from Rome in the 16th century echoes, if faintly, to the present day, with laws on the books forbidding the heir to the British throne from marrying a Catholic.

In fact, the country is one of the less religious ones in Europe, home to vociferous critics of religion, like Richard Dawkins, and those who find belief in a higher power simply unnecessary, like Stephen Hawking.

Public opinion on the eve of his visit ranges from indifference to downright hostility. There will be protests from critics who consider him a protector of pedophiles and from liberal Catholics who resent his staunch defense of orthodox doctrine.

And all this will play out in in front of the British media -- one of the world's most aggressive.

So why, aged 83 and happier at home, is the professorial vicar of Christ on earth stepping into the lion's den? It may be the very factors that seem to argue against his coming that impelled him to come, according to two experts.

This pope relishes a challenge, said John Allen, CNN's senior Vatican analyst. His "No. 1 priority is to combat secularism, and in some ways the United Kingdom is the dictionary definition of a post-religious society," Allen said. "He just created a whole new department in the Vatican to reawaken the faith in the West, and this trip is a chance to elaborate a strategy."

Benedict will make what the Vatican is billing as one of the major speeches of his papacy in London on Friday, making the case for religion over a purely secular society. Benedict biographer Gibson said the pope, formerly Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, has a history of rolling up his sleeves and taking on his intellectual opponents.

"He enjoyed it when he was cardinal -- going to various places and venues and presenting controversial views in a polemical tone," said Gibson, the author of "The Rule of Benedict." "Britain is such a redoubt of secularism, he can [try to] slay the dragon in its lair. He can't resist, really," Gibson said.

A close confidant of Benedict made headlines shortly before the visit by likening London's Heathrow Airport to a Third World country, but Cardinal Walter Kasper also very pointedly criticized what many Christians see as enforced secularism in the United Kingdom.

While Benedict is picking a fight with secularism, he also needs to mend bridges with fellow Christians, both experts said. The Catholic Church moved surprisingly forcefully last year to make it easier for disaffected members of the Church of England to switch allegiance to Rome, sparking consternation in a deeply divided Anglican world.

Benedict "cares about relations with the Anglicans, seeing it as the model for relations with all the other Christian churches in the West," CNN's Allen said. Creating "new structures to welcome Anglican converts into the Catholic Church" is seen by many Anglicans "as poaching, so he needs this trip to mend fences."

Allen compared the trip to Britain to one Benedict made to Turkey in 2006 after the pope made controversial comments about Islam. On that trip, the pope appeared with a top Muslim religious leader at Istanbul's famous Blue Mosque. This week he will pray with the head of the Church of England, Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, in London.

Gibson also sees an element of outreach to the Anglican archbishop in the pope's visit -- but also to his flock.

"He doesn't want to have bad relations with Rowan Williams, but he also makes very clear that he wants closer relations with traditional Christians," Gibson said. "He is looking for allies."

Indeed, a leading voice for conservative members of the Church of England, Canon Chris Sugden, said, "Many orthodox Anglicans in England would feel that they share more in common with the pope than with the presiding bishop of the Episcopal church [Rowan Williams]."

That doesn't mean Anglicans see eye-to-eye with the pope on a number of important theological issues, he said, but added, "We welcome the pope's visit because it raises many of the critical challenges to the current elite secularism that is being imposed on us," he said.

And if his religious message proves unpopular in Britain, particularly against the backdrop of the sex abuse scandals enveloping the Catholic Church, Benedict really doesn't mind, Gibson said. "He sees criticism almost as a form of persecution that reinforces the importance and the truth of his message," he said.

"He doesn't care about popularity and in fact revels a bit in drawing protests -- that whole dynamic of being despised proving your faith."

Coming under sufficiently intense criticism could even rebound in Benedict's favor, Gibson said. "British tabloids can be so over-the-top that they can prove his point," he said. "He could become a sympathetic figure."

Visiting the United States three years ago boosted Benedict's popularity there, the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life found. This visit could have a similar effect in the United Kingdom, Allen said.

"My prediction: He'll do better than people expect," he said. "He usually does on the foreign trips."

Most Popular

Fine art from an iphone the best instagram photos from 2014, after ivf shock, mom gives birth to two sets of identical twins, inside north korea: water park, sacred birth site and some minders, 10 top destinations to visit in 2015, what really scares terrorists.

Accessibility Links

Pope Benedict XVI to make first ever official papal visit to Britain

Pope Benedict XVI will come to Britain next year, making the first state visit by a pontiff. He is expected to meet the Queen, the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, and may stay at Buckingham Palace.

The historic event, probably in September, is likely to overshadow even the triumphant pastoral visit of Pope John Paul II in 1982. Unlike John Paul II, whose visit almost did not take place because of the Falklands conflict, the pontiff will meet the Prime Minister in a series of events over three days, which it is hoped will finally consign to the past Britain’s post-Reformation legacy of anti-Catholic prejudice.

Gordon Brown extended an invitation during an audience in February and preparations have been under way for some

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘So noble, so kind’: Pope Francis leads tributes to Benedict XVI

Emmanuel Macron and Rishi Sunak among world leaders offering tributes to the former pope who died aged 95

Pope Francis called former pope Benedict XVI a noble, kind man who was a gift to the church and the world, in his first public comments since the death of his predecessor earlier on Saturday.

Francis spoke in the homily of a previously planned New Year’s Eve vespers of thanksgiving in St Peter’s Basilica.

“It is with emotion that we remember his person, so noble, so kind. And we feel in our heart such gratitude, gratitude to God for having gifted him to the church and the world,” Francis said.

Political and religious leaders around the world paid tribute to Pope Benedict XVI, after his death was announced on Saturday.

President Joe Biden, a devoted Catholic, said the Pope Emeritus, who stunned the Roman Catholic church when he retired almost 10 years ago, would “be remembered as a renowned theologian, with a lifetime of devotion to the church, guided by his principles and faith”.

“May his focus on the ministry of charity continue to be an inspiration to us all,” he added.

Jill and I join Catholics and others around the world in mourning the passing of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. He'll be remembered as a renowned theologian, with a lifetime of devotion to the Church, guided by his principles and faith. May he continue to be an inspiration to all. pic.twitter.com/ufGRsscnZV — President Biden (@POTUS) December 31, 2022

King Charles III praised Benedict’s “constant efforts to promote peace and goodwill to all people” after his death.

The King expressed his “deep sadness” at Benedict’s death in a message to his successor Pope Francis, as the head of the Church of England.

Benedict became the second pontiff in history to visit the UK in 2010 when he met the Queen and made a historic address at Westminster Hall.

Rishi Sunak, the UK prime minister, said he was saddened at the news of Benedict’s death and recalled his visit to Britain in 2010 as “an historic moment for Catholics and non-Catholics throughout our country”.

Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, also said Benedict’s visit had been “historic and joyous”.

Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, said the former pope’s visit to Scotland had been “special”.

Giorgia Meloni, the Italian prime minister, said Benedict was “a giant of faith and reason … A Christian, a pastor, a theologian: a great man whom history will not forget.”

The French president, Emmanuel Macron, said his “thoughts go out to Catholics in France and around the world”. Benedict had “worked with all his soul and intelligence for a more fraternal world”, he added.

Michael D Higgins, the president of Ireland, said that during his tenure Benedict had “sought to highlight both the common purpose of the world’s major religions and his injunctions as to how our individual responsibilities as citizens require the highest standards of ethics in our actions”.

Olaf Scholz, the German chancellor, said: “The world has lost a formative figure of the Catholic church, an argumentative personality and a clever theologian.”

Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, paid tribute to an “outstanding theologian, intellectual and promoter of universal values”.

The UN secretary general, António Guterres, described Benedict as “principled in his faith, tireless in his pursuit of peace, and determined in his defence of human rights”.

“He was a spiritual guide to millions across the world and one of the leading academic theologians of our time,” he added. “His powerful calls for solidarity with marginalised people everywhere and his urgent appeals to close the widening gap between rich and poor are more relevant than ever.”

after newsletter promotion

In a statement, King Charles paid tribute to Benedict and recalled visiting him at the Vatican in 2009.

He said: “Your Holiness, I received the news of the death of your predecessor, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, with deep sadness.

“I remember with fondness my meeting with His Holiness during my visit to the Vatican in 2009. His visit to the United Kingdom in 2010 was important in strengthening the relations between the Holy See and the United Kingdom.

“I also recall his constant efforts to promote peace and goodwill to all people, and to strengthen the relationship between the global Anglican Communion and the Roman Catholic church.”

Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Westminster and leader of the Catholic church in England and Wales, said Benedict was “one of the great theologians of the 20th century”.

During his visit to the UK in 2010, Nichols said: “We saw his courtesy, his gentleness, the perceptiveness of his mind and the openness of his welcome to everybody that he met. He was through and through a gentleman, through and through a scholar, through and through a pastor, through and through a man of God – close to the Lord and always his humble servant.”

Justin Welby, the Anglican archbishop of Canterbury, described him as “one of the greatest theologians of his age – committed to the faith of the Church and stalwart in its defence”.

Welby added: “In 2013, Pope Benedict took the courageous and humble step to resign the papacy, the first pope to do so since the 15th century. In making this choice freely he acknowledged the human frailty that affects us all.”

Eamon Martin, the archbishop of Armagh and leader of the Catholic church in Ireland, noted Benedict’s “humility and gentleness” and extended “sympathy to Pope Francis, to the family members and carers of the Pope Emeritus, and to all those in his native Germany and around the globe who loved him and will mourn his loss”.

The Catholic Women’s Ordination was more critical. In a statement the group, which seeks to ensure women are equal with men within the church, said: “Pope Benedict sadly represented an exclusive male clerical, hierarchical church that forbade women even to discuss women’s ordination. He went as far as to define the act of seeking women’s ordination, an excommunicable offence during his time as pope, as a grave crime equal to clerical sexual abuse.”

CWO said it would pray for repose for his soul, but that “we pray too for all victims of clerical abuse for whom his death will be a trigger and for those women, throughout the world, whose vocations to the Catholic priesthood continue to be dismissed and blocked”.

- Pope Benedict XVI

- Catholicism

- Christianity

Most viewed

Pope Francis appoints first Catholic bishop with Anglican heritage for UK ordinariate

LONDON (OSV News) -- Catholics in the United Kingdom that are part of the personal ordinariate, a kind of diocese originally set up to receive groups of Anglican Christians into full communion with the Catholic Church, have welcomed Pope Francis’ appointment of their first bishop -- and the first ordinariate bishop to hail from their Anglican heritage.

“Although we’re full Roman Catholics, our ordinariate allows us to preserve something of our Anglican patrimony within the universal church,” Msgr. Keith Newton, the retiring head, or ordinary, of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, told OSV News.

“As a priest, however, I’ve also been one of very few bishops’ conference members not in episcopal orders,” he said. “The Holy See has wanted us to be governed by a bishop, to clarify our ecclesiastical status within the Catholic Church.”

The London-born priest, a married former Anglican bishop with three adult children, spoke with OSV News after the April 29 appointment of his successor, Bishop-designate David Waller, to lead the U.K. ordinariate.

Established by Pope Benedict XVI in 2009, the personal ordinariates function as Catholic dioceses with Anglican traditions that celebrate the Mass, divine office, sacraments and other liturgies in traditional English according to the liturgical books approved by Pope Francis.

Pope Benedict originally conceived these ordinariates as a permanent, pastoral response to whole congregations from the Anglican tradition -- such as Anglicans, Episcopalians and Methodists -- asking to enter the Catholic Church with their traditions as intact groups. In 2019, Pope Francis expanded the ordinariates’ missionary mandate to invite all Protestant Christians into full Catholic communion and enliven the faith of Catholics who had weakened or fallen away from the practice of the faith.

Pope Francis’ decision makes the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham the second of the three existing personal ordinariates to have its very own bishop. Pope Francis appointed Bishop Steven J. Lopes in 2016 as the first ordinariate bishop for the Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, which covers the U.S. and Canada; he also appointed Bishop Anthony Randazzo in 2023 as the temporary apostolic administrator for the Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross, which includes Australia, Guam, the Philippines and Japan.

Unlike Bishops Lopes and Randazzo, Bishop-designate Waller is the first bishop coming from an Anglican background to lead a personal ordinariate.

Msgr. Newton said he had been “generally accepted” as the U.K. ordinariate’s shepherd by the U.K.’s Catholic bishops; but he noted it had also been difficult for other prelates to accept the first “overlapping Western jurisdiction” within their church. Unlike a typical diocese of the Latin Church, which has immediate jurisdiction within a set territorial boundary, a personal ordinariate’s jurisdiction can extend over its Catholic members nationwide or across national boundaries.

Meanwhile, another former Anglican bishop, now a Catholic priest in the U.K. ordinariate, also welcomed Bishop-designate Waller’s nomination, adding that he hoped this added sign of permanence would encourage more individuals and groups of Anglican Christians to seek full communion with the Catholic Church through the ordinariate.

“Without a full bishop, we’ve had to bring someone in for ordinations and other visible sacramental duties, diminishing our own ordinary’s authority,” explained Msgr. Andrew Burnham, who was one of three serving Church of England bishops received into the Catholic Church on Jan. 1, 2011, for the ordinariate and then ordained as Catholic priests two weeks later by now-Cardinal Vincent Nichols of Westminster, England.

As a celibate priest, Bishop-designate Waller is eligible for ordination to the episcopate. Although the Catholic Church has a married priesthood (normative in its Eastern churches but by exception in the Latin Church) alongside a celibate priesthood, the ancient practice of the church -- one shared with the Orthodox churches -- is to only ordain celibate men to the episcopate.

Because he is married, Msgr. Newton could be ordained a Catholic priest, but not ordained a Catholic bishop. His position as a priest-ordinary, similar to the status of a chorbishop in Eastern churches, gave him much of the authority of a bishop but without the full powers of a bishop, such as the ability to ordain new priests.

“Given how many people predicted our ordinariate would fizzle out, it’s amazing it’s still functioning, in some cases flourishing, 13 years later,” Msgr. Burnham said. “The appointment of a bishop will give it a new lease of life, and encourage those wondering if this is the way to go.”

The London-based Ordinariate was created Jan. 15, 2011, by a decree from the Vatican’s Congregation (now Dicastery) for Doctrine of the Faith, and placed under the patronage of St. John Henry Newman (1801-1890), an Anglican who came into full communion with the Catholic Church, became a cardinal and is known as the most influential English-speaking Catholic theologian of the 19th century.

According to its website, the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham has more than 80 priests and 50 pastoral groups across Great Britain and Scotland. The ordinariate also has some synodal forms of governance Benedict XVI mandated: the bishop, or ordinary, governs together with a governing council composed of at least six priests and which has deliberative vote on certain matters. Ordinariate priests vote for half of the governing council’s members. A pastoral council, representing various areas of the ordinariate, is also required by the ordinariate’s apostolic constitution in order “to provide for the consultation of the faithful” and advise the bishop on the ordinariate’s pastoral activity.

In an April 29 statement, Bishop-designate Waller said he looked forward to the ordinariate’s “next chapter,” after serving as chair of its governing council and as vicar general since 2020.

“The past 13 years have been a time of grace and blessing as small and vulnerable communities have grown in confidence, rejoicing to be a full yet distinct part of the Catholic Church,” said Bishop-designate Waller, who had both led three Anglican parishes and served on the Church of England’s governing synod before becoming Catholic through the ordinariate in 2011. Once ordained a Catholic priest, he served both ordinariate and diocesan Catholic communities.

“My experience of these past years is that there is nothing to be feared in responding to the Lord and that Jesus does great things with us despite our inadequacies,” he said.

Msgr. Newton explained it had taken two years of consultation before the Vatican finally confirmed Bishop-designate Waller as the right candidate to succeed him. He added that it was “highly significant” his successor would be the first ordinariate priest from an Anglican background to obtain full episcopal rank in the three existing personal ordinariates.

Meanwhile, Msgr. Burnham said he had expected a new ordinary to be “appointed from outside,” as in North America and Australia, adding that he was delighted the U.K. ordinariate had found a suitable celibate candidate from its own ranks who could be ordained bishop.

“The ordinariate has tried to attract Anglicans, enabling them to see what full communion with the Catholic Church might be like,” said the priest, who was Anglican Bishop of Ebbsfleet from 2000 to 2010.

The bishops of the other two of the Catholic Church’s ordinariates for the Anglican tradition greeted the selection of Bishop-designate Waller and praised Msgr. Newton for his dedicated leadership in their own statements.

“In many ways, Monsignor Newton has fostered the broad identity and mission of the Ordinariate, especially as this still relatively new entity takes its place in Catholic life and contributes to the evangelical dynamism of the whole Church,” Bishop Lopes said.

Bishop Randazzo joined Bishop Lopes in welcoming Bishop-designate Waller, and extended his “profound gratitude and fellowship in prayer” to Msgr. Newton for shepherding the U.K. ordinariate since 2011.

“His dedication and service have been foundational to the growth and spiritual nourishment of the Ordinariate,” Bishop Randazzo said.

Bishop Lopes said Bishop-designate Waller is “a great choice,” citing not just his service as vicar general and on the governing council, but as “a proven parish priest, leading parishes both in the Ordinariate and in the Diocese of Brentwood.”

“As he begins this transition and takes up his new responsibilities as Bishop, he can count on the prayers, encouragement, and support of all of us in the Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter,” Bishop Lopes said.

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

Church Life Journal

A Journal of the McGrath Institute for Church Life

- Home ›

The Legacy of Benedict XVI

by Cyril O'Regan April 18, 2024

W hen it comes to Benedict XVI we find ourselves in the strange and awkward position that we neither know how to end nor how to start dealing with his legacy. We don’t know how to end insofar as we continue to receive his person and work. Like Vatican II, of whose reception he spoke so often, we live in the midst of discernment and argument concerning who and what he has bequeathed to us. Yet, we are also not quite sure how or where to begin dealing with a life that was constituted at once by unshakeable Christian conviction and deep investigation into truth, characterized by prayer, focused on the Eucharist that equally founded the Church and the Christian, moved by contemplation of the Word (made man) that is the purpose and meaning of all the words of Scripture as well as the stated purpose of his own life, and supported by the still small voice of the Holy Spirit that grounded his faith, his hope, and love, which gave him the courage to speak out from the Church to the world that needs redemption and to a sinful Church that requires unceasing vigilance.

With his work where to start? Where to determine the indelible pattern, given the manifold contributions he made to Catholicism in and through his deep historical studies (e.g. Augustine and Bonaventure); major theological inquiries in the areas of liturgy, eschatology, Church, ecumenism, and the theology of religions; his catechetical works (especially Introduction to Christianity ) in which he clarifies the faith that has been handed on to us both in terms of the beliefs that make up its content and the confession that binds us to these beliefs as ineluctable and inscribes them in our lives and in our deaths, in our intellects and in our flesh; and—working backward—his interventions as Pope, Cardinal, and Bishop in the public space to speak to the challenges faced by Christianity and the Catholic Church in a secular world that has essentially bled off transcendence, assumed that reason and faith are binaries, questioned all authority, laughed off Christianity’s claims to exclusive truth, denied all hierarchy, spoken satirically or juridically (or both) of Church malfeasance, lodged complaints not only about the Church’s collusion with power and power structures, but determined that the sponsoring of violence is intrinsic to its essence (e.g. the argument of the Egyptologist, Jan Assmann); and when not culpable, then useless: entirely incapable of adding anything to the human search for justice and human rights or indemnifying or even contributing meaningfully to the questioning that marks natural science and the historical and human sciences.

Obviously, one cannot speak definitively to a legacy that is as multivalent as it is excessive. Furthermore, it is likely that a real beginning is beyond us. Yet maybe we can begin to begin. With that more modest aim in mind—and suggesting more as a heuristic than a constitutive interpretive framework—perhaps we can simplify the task by looking at Benedict XVI in the mode of a Christian public intellectual who addresses himself to the secular age and who at once engages its critical stances towards Christianity determined to be authoritarian, fundamentally irrational, fanatical, and prone to violence and useless when it comes to contributing to unfettered inquiry, ethics, and modern culture. We could, and perhaps should, pursue this line of investigation in a straightforward way and critically assess what is living and dead in these episodic but recurring interventions on a range of matters in which Benedict either resists particular negative constructions of Christianity or criticizes fundamental aspects of the secular world either because of a stance it takes on fundamental issues that bear upon the understanding of society, culture, and value or its refusal to entertain Christian views that have a more particularist foundation. I propose to do something slightly different, specifically, not to talk at length to recognizable interventions by Benedict, but rather to the overall horizon and ethos of these interventions that identify him as a singularity as much—if not more—than these public interventions themselves.

I would like to suggest that we can begin to begin receiving Benedict XVI in his mode of critic of secular modernity, as well as defender of the faith and the Church under four aspects or auspices, those of voice , vision , witness , and gratitude . By voice I mean the ways in which across his various roles as theological expert, Bishop, Cardinal, and Pope anything that is idiosyncratic in terms of his person and particular and insistently partisan in terms of position is left behind in light of the commitment to the objectivity of truth that can speak for itself. By vision I mean both the telescoping of who God is as read from the immense love affair of God with his creation as this is focused in the drama of salvation and the figure of Christ. By witness I mean the engaged stance taken by Benedict in general and, more specifically, the stance taken on the basis of the fundamental conviction that if it is true that Christian life without beliefs is blind, it is equally true that Christian belief without commitment, risk, courage, and perseverance is empty. By gratitude I mean not only Benedict’s astonished sense of the gift of the Christian tradition and the mystery of Christ who is both its center and horizon, but his recommendation to the secular world that it pay heed to this Christian tradition as an inheritance that accounts for what is best and most substantive in secular thinking on justice, culture, and human dignity. I will speak to these four aspects in turn, and conclude by making some general remarks about their interpenetration.

His voice: not, as it has been so baselessly claimed, the bark of God’s bulldog; not the shout of the screamer with a bullhorn; not the voice of the carnival snake-oil man; but a calm, “kind” voice steadfastly speaking the truth, witnessed to by a two millennia-old tradition of reflection (conversation and argument) that renders the reality (Greek, ousia ) or authority (Greek, exousia ) of the Christ, who unforgettably told the whole truth in life, action, and in words, as he exposed himself to the scorn and violence of those who refused to listen and those who were provoked by his innocence and blamelessness. The voice of Benedict XVI is unmistakable in that it is emptied of its individual substance, desire, and insistence. That this voice or its modulation has to do with Benedict’s understanding of the office of Peter is undeniable: to be pope is to enter a role that takes on the Christological role of absolute service and being for others.

Yet, it has also got to do with his understanding of what it is to be Cardinal, to hold the office of Prefect in the CDF, to be Bishop with the responsibility of teacher, and to be Priest with the responsibility of sharing the Eucharist mystery. Ultimately, and constitutively, it has to do with Benedict’s understanding of what it means to be a Christian as a disciple of Christ, called to be a light to the world. To be a light is to be tasked not only to speak boldly ( parrhesia , 2 Cor 3:12) of the hope that has been given to the Christian, but also when necessary to critique with the same calm confidence as the ruling idols of the moment that press on Christianity not only by relativizing or denying its truths, but by questioning its rights to proclaim them. This prohibition arises from the tyranny of relativism that marks the secular world, the tyranny that would bar such claims on grounds of special pleading, groupthink, exclusion, and thus implicit violence simply awaiting a spark to make it explicit.

A fundamental element in speaking the truth is to expose the systemic inhospitality of the modern secular state towards Christianity that can at inopportune moments verge into open hostility. This is not to say that the secular world is always wrong in its criticisms of the behavior of the Church that has at times been both reprehensible and scandalous (e.g. the sex abuse crisis) and that the secular world has not been justified in pointing to the way in which the Church—similar to most worldly institutions—is too often guided by the instinct of self-preservation and self-reproduction. For Benedict, as for John Paul II, the world can provide moments for Christian self-inspection and ample opportunities for repentance. Still, overall, for Benedict, the “neutrality” of the modern secular world is as a matter of fundamental principle “armed”: it constructs the Catholic Church as irredeemably authoritarian both in its basic structure and in its public performance towards the world; as substituting an irrational faith for reason, which if objectionable in itself becomes more objectionable as it serves to sponsor violence. Further, it constructs the Church as recommending ways of thinking that straightjacket free inquiry (thereby making it incomprehensible how the university came into being under the tutelage of Catholicism) and engender unfree forms of living contrary to genuine human flourishing.

For Benedict, to respond critically to secular modernity is first to avoid being provoked by it; it is to exercise discernment and discriminate between what is hale and harmful in it; what can be sanctioned by reason understood against the backdrop of its full philosophical amplitude and what in it agrees with the Wisdom (reason as both substantive and holistic) that Christianity attempts both to honor and perpetuate. Demonization of secular modernity is reaction-formation, thus hostage to what it would deny as well as betraying a lack of confidence in the ultimate persuasiveness of truth it would proclaim. Benedict understands that the dominant narrative of secular modernity, to the effect that everything valuable concerning the ratification and protection of human rights depends upon reason’s critique of and separation from Christianity, is entirely self-serving, and deliberately ignores the insights bequeathed to it by the Christian tradition.

The omission perpetrated by secular modernity should be named. Nonetheless, dialogue should not—nor cannot—be broken off, for Christian faith is necessarily an encounter with a world yet to undergo transformation. As such, it needs to be listened to, even if not all of it can be taken on board—thus, Benedict’s capacity to speak to such secular eminences as Habermas and Rawls, as illustrated in an essay from his pontificate such as “Science, Technology, and Faith.” If, as he believes, both are tempted towards a procedural rationality in which the end is consensus, it is remarkable, he suggests, that in the end both qualify their positions: on the one hand, Rawls concedes that consensus has to yield to more substantive truths that may or may not be confirmed by the majority, and Habermas finally realizes that his discourse ethic needs to be leavened by a “sensibility to truth.”

The voice of the pope, the voice of the Christian is made ripe and full by listening: listening to the truth that has been spoken by the tradition, the good that has been lived; listening to the words of Scripture that speak the Word who is truth and life, but also consummately the way. Perhaps Benedict provides a synecdoche of listening when he recalls the pericope in 1 Kings: 3:5. There Yahweh asks Solomon who is about to ascend to the throne what he wants as a gift. Eschewing worldly goods and gratifications Solomon requests a “listening heart.” It is this gift that will enable him for “God speech” (Benedict’s notion of conscience) in and through the bustle of contingency and obligation and despite the noise of the world, and in doing so to unveil and show the way. It would be tempting to think in Benedict’s words and writing that the reproof of bluster and violence in speech as fundamentally unchristian represents the unilateral sanction of “civility.”

While given his philosophical temper, his commitment to reason, and the historical memory of fascism in his own country, Benedict has an elective affinity to tempered speech, he is not proposing civility as the answer or the antidote. He is reluctant to do so because he is aware that the “ask” of civility in the secular world often involves more than the request that certain protocols be obeyed in public speech, but effectively proscribes certain views as rationally baseless, as tribal, as atavistic. The calm that attends the speaking of truth for whose profession, but not whose outcome you are responsible, the recognition of the humanity of those whom you address who are vehement—even ferocious—in their disagreement with you, guarantees that something far more substantive than public “good form” is in play. The manner of speech is not an envelope for the content. As in the case of Socrates and the classical philosophical tradition (think: Aquinas), it is its indelible form. And with respect to voice—from which the I and its insistence has been removed—as with respect to any number of other facets of the dialogue between faith and reason in the West, the voice of Socrates is an analogy—perhaps a pale one—of the voice of the true shepherd brimful of love and forgiveness and hope for those who refuse the truth and ridicule those who speak it. The voice of Benedict is immediately recognizable because of its emptying, its exinanition, its absolute humility.

Even more than Introduction to Christianity , Benedict’s first encyclical Deus Caritas Est represents both node and summary of what he understands to be the essence of Christianity . This essence is in the first instance a vision rather than a theory inscribed in a set of doctrines or a set of religious practices and precepts. The vision is focused on who God is as God has expressed Godself in creation, but above all in the incarnation, passion, death, and resurrection of Christ. This vision is not only prime with respect to all other facets of Christianity. This vision is in a quite literal sense an apocalypse ( apocalypsis ) that provides meaning and direction to our lives by focusing on God as the giver of all gifts, and, especially of himself. It is within the brackets of God’s promises and coming through on those promises across a series of incalculable gifts that history happens. Of course, the title of Benedict’s most famous encyclical is taken from 1 John 4:8.

Given the contemporary production of Jesus of Nazareth (3 vols.), it does not seem an exaggeration to claim that this encyclical represents a crystallizing point to Benedict’s conviction that the Fourth Gospel represents the inflection (because reflection) point of the Gospels and the answer to the haunting question of Mark 8, “Who do you say that I am?” A primary purpose of the Church is to remind believers of this vision that has animated the Catholic tradition and that needs to be inculcated in a contemporary Catholic Church that even when its members are open to belief and precept they remain without conviction and direction. Without this vision as a source of meaning and truth, and perhaps above all of galvanizing energy, it is difficult to navigate the challenges of faith in a world jam-packed with questions and even more jam-packed with non-Christian answers. The first task of evangelization is to repair or inculcate vision, which if it is the fruit of Scripture and tradition, also makes sense of both.

Benedict’s vision is Johannine in a second, and more dramatic, sense in that it takes full account of the forces that oppose this vision and the thinking and the living that flow from it. The Gospel of John presents the fundamental diagnosis: it names the opposing force as “world” and implies thereby all that is in thrall to comfort, prestige, ethnic superiority, habit, anger, resentment, and revenge, as well as the thousand peccadillos that make the world go round and round and numb the prospects for transformation. Important also for Benedict is the Book of Revelation—a book that Benedict refuses to disown, despite its numerous misappropriations and misuses—and especially its concentrated focus on the forces of the world. Of course, this book is the revelation of the eternal meaning of Golgotha. The Lamb who is slain before the foundation of the world (Rev 13:8) is Christ in the hidden glory of the Cross. Precisely as such he is rejected and resisted. Whereas the modes of resistance picked out in John’s Gospel are passive and diffuse—darkness automatically rejects the light—the modes of resistance picked out in the book of Revelation are active and suppose the event of Christ as embodying a fundamental challenge to the world that is polarizing and escalates resistance. If the book of Revelation is the book of the martyrs or the book of the “saints,” it is also the book of the lie and the simulacrum. For Benedict, the Book of Revelation is a book that reads history, discerns its patterns, judges its meaning, and adjudicates its value.

To read history faithfully, however, is to see it as an agon in which the forces that resist God and the good are catalyzed in and by their opposition to the truth. If the result is persecution and oppression then and now, the result is also deceit, substituting a more palatable and appealing Christ for the one that hung on the cross to expiate our sins. The counterfeit or simulacrum on offer is that of Christ who will make us feel exalted and justified just as we are and who will waive our need to forgive as we are forgiven. In short, this Christ is one who shares enough attributes with the Christ confessed by Christians over millennia for us to feel that we are in contact with the real thing, though by the same token possessed of enough dissimilar features to convince ourselves that he has been brought up to date. In the Book of Revelation, this figure is the figure of the Anti-Christ. For Benedict, as for Newman in the nineteenth century, this figure can be an actual person, a violent political regime, and a presiding ethos that sucks the life from historical Christianity. The recently canonized saint and the recently deceased pope emeritus both sense that the modern secular ethos fits the bill.

History is a drama, both the drama of our suffering (Christians suffer over the world) and the drama of our choosing between the real Christ and a spurious Christ who is nothing more than an idol. If the drama of choosing is implicit for Benedict in the Book of Revelation, it is explicit in the great temptation scenes in Matthew 4 and Luke 4 in which Christ—and thereby the Church he founded—is asked quite literally to make the devil’s bargain: the price of universal rule is allegiance to a power in love with power. For Benedict, the three temptation scenes in Luke and Matthew are requests for acts of showmanship contributing to success that distort both human beings and God. With regard to the first temptation, to turn stones into bread is not to respond to the poor as Christ responds to them as bearers of inalienable human dignity, but to have decided in contempt that for them their only value is bodily satisfaction. With regard to the second, to consent to expanding the kingdom at the cost of yielding to the prerogatives of naked power is to betray the absoluteness of God and the gift of our indelible relationship with him. If the challenge in the second temptation is power as spectacle (Third Reich and Communism; the great scene in Lord of the Rings of Saruman addressing the orcs), the third temptation has to do with miracle as the suspension of the laws of nature or the apparent suspension of the laws of nature. “Apparent” is the key. As with spectacle, the power of miracle is that it holds hostage human imagination—thus, the rebuttal of this function of miracle and thus its refiguration throughout Luke and Matthew not as contraventions of the laws of nature, but rather signs of God’s compassion and mercy for creatures whom he has loved into existence.

For Benedict, the appropriate response to the apocalyptic figuration of modernity as crisis—indeed as a bundle of crises, for example, epistemic (truth issue), anthropological (whether or not selves have intrinsic dignity and are essentially relational), ethical (whether ethics is contextual or objective), politics (whether a purely immanentist politics is valid), and metaphysical (whether there is a ground or meaning or not)—is witness. Though they are textually and perhaps even intrinsically related, there are essentially two forms of witnessing in the biblical and Christian tradition, that is, suffering for one’s faith even unto death (martyr) and witness in terms of a perception and embrace of a mission to speak God’s judgment on society and on the Church in a condition of crisis (prophet). Obviously, even if there has been a significant measure of suffering, isolation, and ridicule in Benedict’s life, the mode of witness enacted in his life and writings is more prophetic than martyriological in the strict sense.

As with the biblical prophets, the judgment is directed both outward towards society and inward towards the Church in that there is a porous boundary between outward and inward insofar as that which enjoys political, social, and cultural prestige oftentimes is taken up uncritically by religious believers to the detriment of their faith and its hallowed traditions. Benedict’s theology as a whole is surcharged by the prophetic response “here I am.” He will stand for the prospects of truth and the validity of reason, for the intrinsic dignity of human beings, for the objectivity of ethics, and for God precisely as the ground of meaning and truth. He will make a stand equally against modernity’s elevation of instrumental and critical reason and its diminishing of philosophical reason, against the view that human beings are conditionally valuable depending upon whether they exist in or out of the womb, whether they are physically or cognitively impaired, whether they demand huge amounts of medical resources; against contextualist determinism; against relativistic and casuistical species of ethics; against an immanentist politics whether authoritarian or democratic; and against what he understands to be the pervasive and unacknowledged nihilism of modernity in which the divine is no longer the rivet.

All of these are important, but perhaps it is better to follow Goethe’s injunction of “dare to be finite” in the limited time (or space) that I have. So here I will speak to simply one of these crises with respect to which Benedict takes a stand, that is, the epistemological crisis that manifests itself as the “pathology of reason.” No less in talks he gave as Pope, for example the Regensburg Address and “Science, Technology, and Faith,” throughout his entire career Benedict argued against the reduction of reason in the modern world to instrumental reason (see: his essay on Fides et Ratio ). Instrumental reason is reason that has cut its cloth to the measure of problem-solving, having sidelined or dismissed with prejudice almost all the questions that animated classical philosophy, whether the nature of man, cosmos, God, value, happiness, etc. For him, reason realizes itself fully as a wisdom discourse, that is, a discourse comprehensive in its aim, deeper in what it discloses about reality than instrumental reason that shines a sharp light on a narrow slice of reality, and that does not admit of verification or falsification. For almost all of its history, the wisdom discourse of the West has been philosophy, and it is precisely because of its wisdom orientation and inflection that Christianity has been able in good conscience to fruitfully negotiate with it over the centuries.

Of course, Benedict is fully aware that what is at dispute in modernity is less the fact of this encounter than its validity. The validity of this encounter has in the modern world come to be questioned both from the side of philosophy (Benedict’s essay on Fides et Ratio ) and from the side of Christianity (Regensburg Address). It has been attacked from the side of philosophy on the grounds (a) that philosophy is an autonomous discipline that has only in modernity succeeded in throwing off its shackles from the Church that has consistently proven itself to be uninterested in free inquiry; and (b) that philosophy has no validity as a comprehensive discourse: it is either a problem-solving discourse of a particular type (analytical) or it represents a particular stance on the world (postmodern). It has been attacked from the side of Christianity on the grounds that the historical link between Christianity and philosophy has been ruinous to the integrity of Christianity that undergoes the contamination of “Hellenization” in and through the encounter. Hellenization denotes that Christian discourse, which is biblical discourse, is essentially hijacked by being made the servant of an alien discourse that is more propositional and impersonal.

With regard to the first objection (from the side of philosophy), Benedict is perfectly aware that a fact of history, that is the historically close ties between philosophy and Christianity, does not logically imply its justification. As is obvious from his essay “Science, Technology, and Faith,” Benedict sees philosophy as an independent discipline. Nonetheless, he wants to argue that there was something marvelously right—maybe even providential—about the close historical relations between philosophy and Christianity and philosophy and theology more specifically, given that each presents a comprehensive grasp of reality and its foundation. He is convinced that something like the law of double attraction applies. Even if philosophy and Christianity (also theology) are different in kind, nonetheless, philosophy can be seen to find in Christianity a kind of confirmation of its schematizations. Correlatively, in philosophy Christianity finds a wisdom discourse that would enable it at once to understand more clearly the revelation that it has been given and translate it ( apo-logia ) more effectively in a world that is plural in terms of culture, language, history, assumption, and levels of openness to listen to and appreciate what at first blush might be perceived to be alien to it. The site of the crossing, the chiasmus between philosophy and Christianity, is Christ who as Logos is word, but also intelligibility and truth.

With regard to the second objection (from the side of Christianity), which would separate Christian text and Christian faith from philosophy and keep them free from contamination, Benedict replies that the attempt to keep the biblical text free from the infection of philosophy itself exposes the biblical text to either a kind of hapless fundamentalism that, on the one hand, avoids rather than deals with the challenges of modernity (that is, if it is not a product of it) and, on the other, exposes the biblical text to the historical sciences in which its meaning is reduced either to historical facts or the historical-cultural situation of its production or transmission. With regard to Christian faith and its proposed purity, in the Regensburg Address, as well as any number of other places, Benedict argues that there is a pathology of faith correlative to the pathology of reason. Newman also argues that in addition to fideism’s indissoluble contract with fanaticism, its embrace of a God of sheer will (thus unaccountability) rather than Logos is ground zero for religious violence and its justification.

To embrace tradition—the handing on ( traditio ) of the Church to the individual and the community of what it has not earned—is to suggest that the fundamental disposition of reception is gratitude. For Benedict as Pope, Cardinal, Bishop, Priest, and Christian this extends to the entire Catholica —beliefs, precepts, practices, and forms of the Church’s life of a historical reality, as well as its wide array of theological voices, its saints and its prophets, as well, of course, as scripture and its symphony of voices unified by the Word and the glosses in writing, in prayer and song, and in life that it spurred with its fullness and provoked to sacrifice. Then there is the liturgy, which wears gratitude and memory in each of its gestures and words, and, in the Eucharist, memorializes the passion, death, and resurrection of Christ in whom God—who ever remembers us and counts us for more than we are worth—reconciles the world to himself.

It hardly needs saying that the gratitude enjoined on the Church and individual Christian is determinate in the sense that it is shaped by its object. Yet, when we consider the numerous interventions of Benedict into the public arena as pope, Benedict has noted a monumental shift, that is, theoretically and practically the new hegemony is that of self-rule ( auto-nomos ) that refuses to yield to any other, even the “totally Other.” In this brave new world of autochthony, humility is vice rather than virtue, what enslaves rather than what sets you free. For Benedict, the freedom that would be gained by autonomy is forever a chimera: we cannot completely fashion ourselves. Moreover, we have proven time and again that we cannot bear the load of our own self-creation. Just as importantly, for Benedict, this form of freedom is too low rather than too high, riddled by anxiety that cannot be masked by stipulation, beset by accident and self-loathing. Recognition of our limits and the gracious founder of these limits is what sets us free to love, cherish, mourn, and hope, thereby giving us a form of freedom that is rich and determinate. Above all, it sets us free not merely from but for . Freedom for is concretized in service to others and to the world.

These, of course, are Augustinian sentiments and judgments. Recognizing such would not embarrass Benedict who loves Augustine and regards him and his work as a gift to be received—though, of course, Augustine’s work is a cornucopia of gifts: the gift of understanding that life is confession, the gift of understanding our createdness and creaturehood, the gift of exegesis, the gift of understanding that prayer is a call to God who has already called us, the gift of both understanding the Trinity and being taken up by it, the gift of understanding the Church’s relation to an ambiguous social world, and the gift of comprehending at once the peccable as well as impeccable nature of the Church as corpus permixtum.

There are other theologians who are lauded and serve as theological models both in terms of substance and style, for example, Origen, Bonaventure, Guardini, de Lubac, and Balthasar. The general point here that Benedict strikes as Pope and as Christian is the virtue of humility that runs at the tangent to the modern world. Benedict sees this as clearly as T. S. Eliot. He privileges these other, these previous voices. What T. S. Eliot writes in “Burnt Norton”—the second of the Four Quartets —can be slotted in as if it were Benedict’s own avowal or confession:

And what there is to conquer By strength and submission has already been discovered Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope To emulate—but there is no competition— There is only the fight to recover what has been lost And found again and again.

For Benedict, it is gratitude that determines for a Christian the excess of joy over lamentation, the priority of celebration over the declamation of what we have lost in terms of place, prestige, and audience for what is true, good, beautiful, and wondrous. In gratitude is the inbuilt consolation of the memory of the Word who makes true the off-kilter world and makes bearable its ridicule and comic its machinations and deceptions.

The legacy of Benedict is the gift of his life and work with respect to which we are struggling to appropriate adequately, that is, to remember in a way that does justice to its eloquent and charitable firmness, the insights provided regarding the nature of faith, and especially of its understanding of the Church and its encounter with the modern world. With respect to the last of these, his words are as bracing as they are illuminating, and we continue to discern, discriminate, and sift. Yet, what he has bequeathed to us are insights and telegraphic hints rather than fully complete thoughts, diagnoses, and suggested intellectual and moral therapies. Thus, he has given us work to do, given our thinking a future while providing signposts. We would-be Christian thinkers are invited to pull hard on our oars. Thereby we come to honor Benedict our benefactor in the only way that he would approve, that is, by producing a supplement to the treasure of the Christian tradition, just as he was a supplement.

Acknowledging all of this, here I wanted to do something different, that is, present a horizon for his interventions in the public square as well as his retrieval of the Christian tradition that could serve as prologue or epilogue to the inventory of his manifest contributions and the tasks he set. My aim has been provide a set of categories that would do justice to him and his work as a singularity, as itself unforgettable—and not simply memorable—as the thinkers that prompt him to think and to pray. These categories were four: voice, vision, witness, and gratitude.

Looked at in pairs and then the pairs together, these categories suggest an unmistakable Gestalt . Voice and gratitude form a pair insofar as first, the “emptied” voice of Benedict presents an opening for the gracious receiving of an excessively rich tradition that accesses the excessively rich reality of a God who graciously loved us into being and who is with us to the end. Second, gratitude finds a privileged place not only in Benedict’s explicit affirmation of the entire Catholic tradition, but in his voice which is his own precisely as not his own, a voice emptied of its insistence such that we can hear the echoes of numerous other voices, speaking, praying, worshiping, suffering, healing, loving, and hoping. By the same token vision and witness are two sides of the same coin: the Christian vision of God as love opens up a dramatic narrative space in which one stands or yields, is bold or cowers, is faithful or unfaithful, is loving or unloving, is hopeful or has surrendered to despair and meaninglessness. Correlatively, witness supposes not only the profession of a truth that one will live for or die for, but echoes the Christological pattern of suffering, death, and resurrection inscribed in the world that has the power to refuse it.

Finally, the two pairs also relate positively and intersect. Voice and gratitude are what they are because they are caught in the gravitational pull of vision and witness. The voice would not be the voice full of listening unless it were measured by the self-emptying of the cross and the firmness of witness to the end. Nor would gratitude be so wide and deep and so plural, thus so “catholic.” And Christian vision and witness require a voice that has become a proper receptacle because it has drowned out its conceit, cut off the fat of rhetoric, and found a gratitude ample enough for us speak to, praise, and celebrate the bounty of the one so careless as to create us, make us so essential to his life, and pledge everything on the risky hope that we respond by pledging all that we are back.

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is adapted from the welcome address of the de Nicola Center 's conference: “ Benedict XVI’s Legacy: Unfinished Debates on Faith, Culture, and Politics ” at the University of Notre Dame, April 7—9, 2024.

Featured Image: Taken by © Mazur/www.thepapalvisit.org.uk, distributed by Catholic Church England and Wales The Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI in 2010; Source: Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 .

Cyril O'Regan

Cyril O'Regan is the Catherine F. Huisking Chair in Theology at the University of Notre Dame. His latest book is the first installment of a multi-volume treatment of Hans Urs von Balthasar's response to philosophical modernity. The Anatomy of Misremembering, Volume 1: Hegel .

Read more by Cyril O'Regan

Eschatology: Hell, Purgatory, Heaven

January 10, 2023 | Joseph Ratzinger

Newsletter Sign up

Catholic imprint on six ‘swing states’ may shape the global future

In venice tomorrow, pope will find a church struggling against decline.

St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, Italy. (Credit: Public domain.)

ROME – As Pope Francis makes his way to Venice tomorrow, he’ll not only be visiting one of the most fabled and romanticized cities in the world. He’ll also be confronting one of the leading symbols of the statistical decline of Catholicism in its traditional heartland, in a spot once hailed by another pope as a “hunter’s snare for vocations.”

In the surrounding region of Veneto, which is divided into nine dioceses, fifty years ago there were more than 6,000 priests, both diocesan and religious orders. By the year 2004 that number had dropped to 4,800, and today it stands at 3,700.

In the city of Venice itself, there were 714 priests in 1969, shortly after the close of the Second Vatican Council. According to the most recent county, which dates from 2022, the total now stands at 266.

Emblematic is the case of Casoni, a small town of roughly 2,500 people in the Veneto region. It was once hailed as having the highest percentage of its sons and daughters in religious life of any spot on earth; a local historian told the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera on Saturday that between the 19 th century and today, Casoni produced 71 priests, five religious brothers, 76 nuns, and three consecrated laypersons, in addition to two seminarians who died before they could be ordained.

Today, however, Father Alessandro Piccinelli, the local pastor, said that the last person from Casoni to take vows was six years ago, and that today while the weekly Sunday Mass is still relatively well-attended, it’s overwhelmingly made up of elderly persons.

According to the most recent national survey, only 18.7 percent of the population of the Veneto attends Mass on a regular basis, which is below the national average. Between 1984 and 2013, the percentage of couples in Veneto who elected to marry outside the church rose from 11 percent to 61 percent, according to government statistics. The overall number of marriages each year also has dropped, from roughly 19,000 per year in 2004 to 14,000 today, and one out of four of those marriages is a second marriage.

According to some estimates, almost 30 percent of children born in the Veneto today are not baptized, and the share of school-age children electing to take a voluntary religion course is also falling.

“Our priests are ever more exhausted, stressed and depressed, forced to run from one parish to another and to deal with everything that has to be done there,” said local journalist Andrea Priante.

“At times, the only thing they can do is raise a white flag,” Priante said. “In every diocese of the region, on average two or three priests every year ask to take some time away with a sabbatical period.”

In that context, the hope is that the first-ever visit by a pope to the famed Venice Biennale, an annual cultural festival where the Vatican has hosted its own pavilion since 2013. Overall Francis will be the fourth pope to visit Venice since 1972, following Popes Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Francis’s daylong itinerary is expected to include a Mass in St. Mark’s Square, a meeting with young people and a session with female inmates at the Giudecca island prison where the biennale is being staged.

The outing will mark Pope Francis’s first excursion out of the Vatican in 2024. He’s currently scheduled to make other day trips within Italy, to Verona on May 18 and Trieste on July 7, ahead of a major international trip to Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, East Timor and Singapore in September.

For the cost of a cup of coffee at Starbucks, you can help keep the lights on at Crux.

Tuesdays on

Crux . Anytime . Anywhere .

Today’s top stories delivered straight into your inbox.

- John L. Allen Jr.

Holy Land cardinal says U.S. university protests are mistaken approach

- Elise Ann Allen

USCIRF calls on Biden Administration to do more to protect international religious rights

- John Lavenburg

Murder of priest highlights rising violence in South Africa

- Ngala Killian Chimtom

Pope to take part in G7 summit in June to talk Artificial Intelligence

Pope calls for negotiated peace, blasts climate change skeptics in CBS interview

Vatican belatedly weighs in on Italian abortion row

Following Italian lead, Pope creates civil liability for Vatican judges, prosecutors

Augustine Institute president says it’s a ‘crossroads for the renewal’ of the Church

Complaints are made against archbishop in editorial about India elections

- Nirmala Carvalho

Horror and hope lie cheek by jowl in youth prison scandal

Peru farmers meet Lima archbishop amid dispute with Catholic group

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Queen welcomes Pope to UK

Pope Benedict XVI was greeted by the Queen at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, as he arrived in Britain for his historic visit from 16-19 September.

Her Majesty the Queen officially welcomed the His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI to the UK, and spoke of her memories of her own visits to the Vatican and meeting some of his predecessors. She said:

“Much has changed in the world during the nearly thirty years since Pope John Paul’s visit. In this country, we deeply appreciate the involvement of the Holy See in the dramatic improvement in the situation in Northern Ireland. Elsewhere the fall of totalitarian regimes across central and eastern Europe has allowed greater freedom for hundreds of millions of people. The Holy See continues to have an important role in international issues, in support of peace and development and in addressing common problems like poverty and climate change”.

The Pope thanked the Queen for her hospitality, and extended his own greetings to all the people of UK. He spoke of the force for good throughout Britain’s long history, coming from a “respect for truth and justice, for mercy and charity” that benefits Christians and non-Christians alike. Speaking of the UK’s international relations, he said:

“Looking abroad, the United Kingdom remains a key figure politically and economically on the international stage. Your Government and people are the shapers of ideas that still have an impact far beyond the British Isles. This places upon them a particular duty to act wisely for the common good. Similarly, because their opinions reach such a wide audience, the British media have a graver responsibility than most and a greater opportunity to promote the peace of nations, the integral development of peoples and the spread of authentic human rights. May all Britons continue to live by the values of honesty, respect and fair-mindedness that have won them the esteem and admiration of many”.

The Pope also met Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, Foreign Office Minister Henry Bellingham and Scotland’s First Minister Alex Salmond.

After the State welcome and reception at Holyroodhouse, the Pope travelled through Edinburgh in the Popemobile, watched by thousands of wellwishers. This evening, he will lead an open-air Mass in Bellahouston Park, Glasgow.

The trip is the first official Papal visit to the UK, because the Pope has been invited by the Queen rather than the church. It is the first visit to Britain by a Pontiff since John Paul 11 in 1982, which was a purely pastoral visit.

Share this page

The following links open in a new tab

- Share on Facebook (opens in new tab)

- Share on Twitter (opens in new tab)

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

- Asia - Pacific

- Middle East - Africa

- Apologetics

- Benedict XVI

- Catholic Links

- Church Fathers

- Life & Family

- Liturgical Calendar

- Pope Francis

- CNA Newsletter

- Editors Service About Us Advertise Privacy

Pope Francis arrives in Venice, meets with women inmates and artists

By Matthew Santucci

Rome Newsroom, Apr 28, 2024 / 08:00 am

Pope Francis opened his one-day visit to Venice on Sunday morning with a meeting with female inmates where he reaffirmed the importance of fraternity and human dignity, noting that prison can be a place of new beginnings.

“A stay in prison can mark the beginning of something new, through the rediscovery of the unsuspected beauty in us and in others, as symbolized by the artistic event you are hosting and the project to which you actively contribute,” the pope said to the female inmates gathered in the intimate courtyard of the Women’s Prison on the Island of Giudecca.

Pope Francis left the Vatican by helicopter at approximately 6:30 in the morning, arriving in the Floating City by 8 a.m. The pope’s visit, albeit short, holds a deep meaning as Francis is the first pontiff to visit the prestigious Venice Biennale art exhibition, which is marking its 60th iteration. As part of the exhibition the Holy See has erected a pavilion at the women’s prison titled “With My Eyes.” The pope also spoke with artists while he visited the pavilion.

Taking a center seat in the intimate courtyard of the 16th-century former convent, the pope opened his address by saying that he wanted it to be thought not as an “official visit” but an “encounter” centered on “prayer, closeness, and fraternal affection.”

“No one should take away people’s dignity,” Pope Francis said to the inmates, volunteers, and staff, joined by the patriarch of Venice, Archbishop Francesco Moraglia.

Drawing attention to the “harsh reality” of prison, the pope highlighted some of the problems inmates are confronted with, “such as overcrowding, the lack of facilities and resources, and episodes of violence, [which] give rise to a great deal of suffering there.”

But Francis, anchoring his message on hope and mercy, implored the women to “always look at the horizon, always look to the future, with hope.”

The pope continued by noting that prison can also be a place of “moral and material rebirth where the dignity of women and men is not ‘placed in isolation’ but promoted through mutual respect and the nurturing of talents and abilities, perhaps dormant or imprisoned by the vicissitudes of life, but which can reemerge for the good of all and which deserve attention and trust.”

Pope Francis stressed that it is “fundamental” that prisons offer inmates “the tools and room for human, spiritual, cultural and professional growth, creating the conditions for their healthy reintegration. Not to ‘isolate dignity’ but to give new possibilities.”

“Let us not forget that we all have mistakes to be forgiven and wounds to heal and that we can all become the healed who bring healing, the forgiven who bring forgiveness, the reborn who bring rebirth,” the pope added.

At the end of the encounter there was a lighthearted exchange when the pope, after asking the inmates — who responded, in unison, “Of course!” — to pray for him, quipped: “But in my favor, not against.”

At the end of the address, the pope presented an icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary as a gift to the inmates, saying: “Mary has tenderness with all of us, with all of us, she is the mother of tenderness.” In return the female inmates presented the pope with a basket of all-natural toiletries they make through a worker-training program.

Following the encounter with the inmates, the pope made his way to the prison’s chapel, where he spoke to the artists, imploring them to use their craft to envision a world based on fraternity where “no human being is considered a stranger.”

“Art has the status of a ‘city of refuge,’” the pope said to the artists, “a city that disobeys the regime of violence and discrimination in order to create forms of human belonging capable of recognizing, including protecting and embracing everyone.”

- Catholic News ,

- Pope Francis ,

- Vatican news ,

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Our mission is the truth. join us.

Your monthly donation will help our team continue reporting the truth, with fairness, integrity, and fidelity to Jesus Christ and his Church.

You may also like

Pier Giorgio Frassati could be canonized during 2025 Jubilee, cardinal says

Cardinal Marcello Semeraro, the prefect of the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, announced on April 26 that Frassati’s canonization is “on the horizon.”

In May, Vatican to offer special Marian tour of Pope's gardens

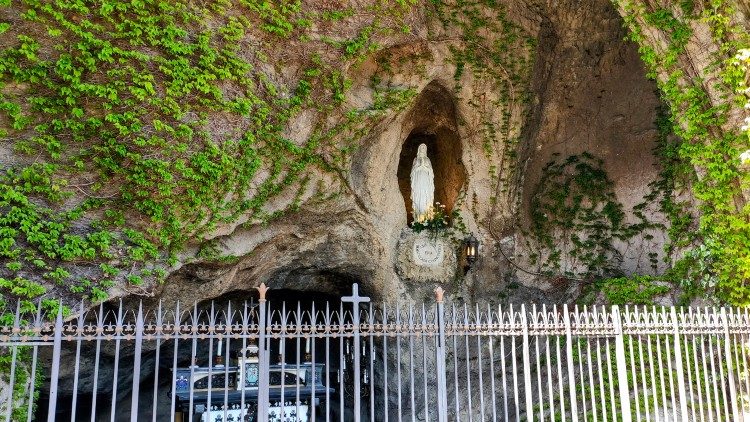

By Paolo Ondarza

"The only way to stop war is through forgiveness!"

The message of the Virgin Mary is both disruptive and clear. Throughout history, she has not failed to indicate to humanity her plan of salvation. At Fatima, for example, appearing to the three shepherd children, she delivered a genuine "peace plan," inviting the world to pray, to return to the Gospel, and to consecrate themselves to her Immaculate Heart.

Prayer for Peace

These words are as relevant as ever when considering the state of the world today.