- Secrets of NYC

- Film Locations

- Architecture

- Arts & Culture

- Food & Drink

- Behind the Scenes

- About Untapped New York

- Jobs and Internships

- Advertise with Us

latest posts

How Old Are These Gas Street Lamps by the BQE?

A Giant Inflatable Dragon and More Outrageous Empire State Building Stunts

Inside a Hidden Basement Bookstore in Brooklyn

Turn Yourself Into a Hologram at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Top 10 Secrets of Rikers Island, NYC’s Main Jail Complex

Rikers Island , New York City’s main jail complex (and the island it sits on), is situated on the East River , between Queens and the Bronx. As one of the largest correctional institutions in the world, the facility is comprised of 10 jails which have a total capacity of nearly 17,000 people – although daily numbers are between 7000 and 9000 .In fact, it has been referred to as the “ World’s Largest Penal Colony .” As a jail however, stays are one year or shorter, with a large portion of detainees who can’t afford bail simply awaiting hearings and trials. 60,000 people men and women return home from Rikers Island each year.

For some time, Rikers Island has peaked our interests; so, in 2010, when someone on the Untapped Cities team officially received access inside , we made sure to document the experience as we learned about its secrets hidden beyond the ID checkpoints and X-ray scanners of the facility.

10. Rikers Island Was Built on top of Landfill Garbage

In 1884, Rikers Island was purchased by the city for $180,000. Although it was originally intended to serve as a work-house, the city eventually expressed a desire to construct a bigger men’s jail on the site . In order to prepare for the facility’s construction, a foundation of garbage , landfill and “street dirt” was dumped on the Island to expand the grounds (and also to save the Street Cleaning Department some effort). In 1924, all barge landfilling operations in New York City was consolidated at Rikers Island, and unlike other city landfills which capped the height of garbage heaps to 10 feet, Rikers Island mounds went higher.

Even after Rikers Island officially opened in 1932, landfill continued to be added to the property until 1943, enlarging the original 90-acre plot of land to its current size of roughly 415 acres. According to Ted Steinberg, author of Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York , 200 acres were also removed from Rikers to help fill in the new North Beach Airport (later renamed LaGuardia Airport ).

Things to Do This Week in NYC: June 12th – 19th

“When Women Ran Fifth Avenue” Reveals the Glamorous Beginning of American Fashion

What to Know When Visiting a Loved One at the Rikers Island Jail

By Kim Kelly

New York City’s notorious Rikers Island jail complex has earned a reputation for brutality, violence , and neglect in its 85 years of existence. As the second-largest facility of its kind in the U.S., Rikers’s very name — an angular switchblade of a word — has long struck fear into the hearts of those sentenced to make that long, lonely trip over the East River to the facility. There are currently about 4,100 people incarcerated in Rikers. Historically, the majority of those held at the facility have not yet been convicted of any crime; they’ve been stuck behind bars while they await trial because they’re unable to post bail — in other words, just because they’re poor.

At one point, 16-year-old Kalief Browder was one of them. The Bronx teen was held on Rikers for three years, without a trial or conviction, for allegedly stealing a backpack — a charge that was eventually dismissed. Much of that time was spent in solitary confinement, a practice that has long been condemned as torture . Shortly after Browder’s release in 2015, he died by suicide. Just last year, Layleen Polanco, a trans woman living with epilepsy, died from complications of the disease after being placed in solitary confinement.

Now, one of my favorite people in the world is in there too. Since October, David Campbell has been locked inside those forbidding walls, doing his best to survive what New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s own lawyer, Alphonso David, has called “a savage and inhumane jail that has ruined the lives of too many New Yorkers.” As a result, I’ve seen firsthand what it’s like to visit a loved one on Rikers Island in 2020.

Following years of campaigning by prison abolitionists and other opponents of mass incarceration, the New York City Council is moving forward with an $8 billion plan to shut down Rikers for good, replacing the massive complex with smaller facilities spread throughout four of the city’s five boroughs. (Activists oppose the construction of those new jails too.) For now, with the shut-down process in its early phases and bogged down by numerous hurdles, Rikers is still standing, and those of us who have friends and family inside its walls must continue to make the arduous journey to visit them. And trust me, it’s arduous . The entire system seems set up to make visitation as difficult as possible, but I’ll explain it, step-by-step, to prepare anyone who finds themself needing to make that trip.

The first time we go visit David, my boyfriend and I leave south Brooklyn at 11:30 a.m. It’s a little after 1 p.m. by the time we get up to 21st Avenue in Queens to catch the special Q100 bus to Rikers. The sign that welcomes you to the island is a gaudy hodgepodge of patriotic symbols, and one big banner declares the prison “ Home of New York City’s Boldest .” We cross the bridge, taking in a panoramic view of the city before the jail complex’s jutting walls and strands of razor wire come into view.

Once the bus stops, a corrections officer comes onboard and reads off a list of items that are considered contraband, telling us to leave any such items on the bus, no questions asked. We go into the first security building, where we are lined up on opposite sides of an invisible line and sniffed at by a hulking police dog. The atmosphere that greets us as soon as we enter the complex suggests that we — the visitors — are on thin ice too, and any wrong move would cost us. It’s nerve-racking.

We file back out into the cold to another building. A guard points us to rows of creaky yellow lockers and tells us to stow our personal possessions — phones, toiletries, purses, Metrocards. We’re ushered into yet another building to go through the first of three rounds of metal detectors. I was especially nervous about this step because of Rikers’s notoriously strict dress code . Clothing is strictly policed , and showing up in anything deemed too tight, revealing, or the wrong color will cost you a visit unless you consent to wear a “cover-up garment” — an oversized neon T-shirt . I was mostly concerned about the restriction on jewelry; only wedding rings and religious necklaces are permitted, and I currently have 13 piercings on my face and body. The day before, I swapped out my metal pieces for glass retainers, and was hoping the guards wouldn’t notice them. Luckily, I make it through, though I am still unsure what threat a nose ring could possibly pose.

We then register with a corrections officer, turning over our IDs, giving our fingerprints (which is apparently optional but I was too nervous to risk gumming up the process), and taking a photo. The officer prints out paper passes with our photo, names, and David’s information and tells us to go wait for another bus. TMZ is blaring on a wall-mounted TV. There’s no indication of when the bus is coming, and no one provides us with any further directions, so we continue to follow along behind more seasoned visitors like anxious ducklings.

The bus to the Robert N. Davoren Center finally shows up, and the drive takes two minutes; we literally just cross a parking lot. We line up outside the door, waiting in below-freezing temperatures. Once inside, we’re ushered into a small room papered with warnings about smuggling in contraband. Eventually, the doors are unlocked and one by one we present our papers again, go through yet another metal detector, have our hands stamped with U.V.-light ink, and enter another waiting room with more lockers where we store our jackets (you’re only allowed to have one layer of clothing in the visiting room).

At this point, I tell one officer that I’m entitled to a two-hour visit because I’m traveling from out of state. He peers at my New Jersey state ID and my Chinatown bus receipt, and denies my request. I remove my belt and shoes a final time to pass through the last metal detector, following a female officer’s request to pull the band of my bra away from my body, pull up my pants legs, and pull down my socks. I pass into the final waiting room, consumed with anxiety as I wait for my boyfriend to join me.

By Kaitlyn McNab

By Versha Sharma

By Kara Nesvig

Inside, a big wall-mounted flat screen is stuck on an empty PowerPoint slide. The other visitors, most of whom are women, stare at the walls. The majority are wearing sweatpants or jeans with plain, neutral-colored shirts. I realize why so many women are wearing Uggs; slip-on shoes would’ve saved us a lot of time. After a few minutes, an officer calls out our friend’s last name. We enter another room and wait.

The grim beige walls are painted with inspirational slogans like “loyalty is royalty.” Across the room, couples hold fast to each other, some sneaking kisses when the officers aren’t looking. Most of the other pairs seem to be in romantic relationships, though there are a few kids there visiting family.

Finally, finally, we get to talk to our friend face-to-face. A low row of plexiglass runs down the middle of the bench, separating us from David and making it awkward to hold hands. He says he’s doing as well as he can. We quickly fall back into our normal patterns, and for a minute, it feels like we’re back at the bar or sitting around my kitchen table — just three people laughing and catching up. Then I reach for my phone to show him some dumb meme, and remember it’s locked up. Reality comes rushing back. Nine months to go.

Our allotted hour passes far too quickly. After what feels like no time at all, an officer strides by and barks, “Visiting time is over! Now!” We hug David tight and tell him we’ll be back soon. As we board the bus, Ginuwine’s “Pony” is playing on the radio, which feels both pleasantly bizarre and unspeakably ghoulish. When we get back to the locker room, I turn on my phone to check the time: 4:17 p.m. We’d somehow been in there for three hours.

With hearts both full and empty at the same time, we head back outside to wait for the Q100. Back over the bridge. Back to our subway stop. Back to our freedom. And next month, we’ll be back to do it all again, until the day we can bring him back over the bridge — away from this hopeless island — with us.

Editor’s note: In an email to Teen Vogue , the Department of Corrections said that a visitor handbook with “all visitor-related information” is available online, and that the security protocols are “designed to ensure the safety and security of DOC personnel, people in our custody, and visitors. The DOC also said they’ve tried to “improve the visiting experience” through measures like creating the visitor handbook and providing children visiting their facilities with crayons and drawing books.

Want more from Teen Vogue ? Check this out: What the Prison-Abolition Movement Wants

Stay up-to-date on the 2020 election. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take !

By Fortesa Latifi

By Tori Gantz

By Bahar Mirhosseni

By Sophie Hayssen

- BREAKING NEWS Tracking air quality across the New York City region Full Story

- WEATHER ALERT Heat Advisory Full Story

- ABC7 New York 24/7 Eyewitness News Stream Watch Now

- THE LOOP | NYC Weather and Traffic Cams Watch Now

- 7 on your side investigation

Lawmakers tour Rikers Island, call conditions inside 'inhumane'

RIKERS ISLAND, New York City (WABC) -- More than a dozen local and state lawmakers went on a private tour of Rikers Island Monday morning and used the words "tortuous," "inhumane" and "horrific" to describe the conditions they witnessed inside.

Their tour comes one week after a 7 On Your Side Investigation found an increase in violence taking place inside the jail complex, and some assaulted officers told Eyewitness News they were afraid to go back to work.

"It is a nightmare, a nightmare back there," state Senator Jabari Brisport said.

RELATED | Rikers Island officers 'scared to go back to work' amid spike in violence

One lawmaker said dogs in kennels are treated better than the 6,000 inmates.

"What we saw today was horrific," Assembly member Zohran Mamdani said.

They said some people have been inside the jail intake for more than a week with no access to food, bathrooms and medications and no contact with attorneys.

"The toilets are overflowing onto the floor," Neighborhood Defender Service Managing Director Alice Fonteir said. "They're packed in, 25 people in a cell, without masks, brought off the streets and crammed into here. There are court appearances that have been missed."

The lawmakers and officials pleaded for prosecutors not to send any new inmates to the jail and for Governor Kathy Hochul to sign a new bill that could let up to 1,000 inmates go who are inside on technical and parole violations.

"I just witnessed an attempted suicide," Assembly member Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas said. "Nobody deserves this."

Our 7 On Your Side investigation showed the number of inmates is up, while the amount of officers is down due to retirements and resignations.

As a result, some corrections officers are working up to 25 hours at a time and calling out sick in record numbers.

"Now they want to let all of the criminals out on the street, as if there's not enough crime in the streets," Correction Officers' Benevolent Association President Benny Boscio, Jr., said. "Yes, inmates are suffering. Corrections officers are suffering 25-plus hours working straight, no meal breaks, then they wonder why they're not coming to work."

More 7 On Your Side | Despite Census numbers, COVID pandemic exodus continues in NYC

Most people who toured the complex, along with the union president, called on Mayor Bill de Blasio to take action.

During a press briefing Monday morning, de Blasio said new officers will be hired and the ones who are out sick need to come back to work if they can.

"We, for years and years, have been working to change the situation in a place that's profoundly broken and should've been closed a long time ago and we are closing," de Blasio said.

DO YOU NEED A STORY INVESTIGATED? Dan Krauth and the 7 On Your Side Investigates team at Eyewitness News want to hear from you! Call our confidential tip line 1-877-TIP-NEWS (847-6397) or fill out the form BELOW. You can also contact Dan Krauth directly:

Email your questions, issues, or story ideas to [email protected]

Facebook: DanKrauthReports

Twitter: @ DanKrauthABC7

Instagram: @DanKrauth

Related Topics

- NEW YORK CITY

- RIKERS ISLAND

- 7 ON YOUR SIDE INVESTIGATION

- CORRECTION OFFICER

7 On Your Side Investigation

Emergency response times increase in New York City

New squatter bills proposed to track and charge trespassers

NYPD pursuits up more than 644%, costing city taxpayers millions

Squatter Standoff: Eyewitness to Change

Top stories.

Baseball legend Willie Mays dies at age 93

Suspect charged in rape of 13-year-old in Queens

Justin Timberlake arrested in Sag Harbor on DWI charges

AccuWeather: More heat, humidity and an Air Quality Alert

Live updates: NYC, Tri-State brace for 1st heat wave of summer

MTA stops Second Avenue subway expansion construction

- 2 hours ago

Man steals running car with child inside in Manhattan

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

10 Deaths, Exhausted Guards, Rampant Violence: Why Rikers Is in Crisis

A number of recent deaths have prompted questions about the notorious New York City jail complex. Here are some answers.

By Jonah E. Bromwich and Jan Ransom

New York City’s notorious Rikers Island jail complex has long had a reputation for brutal conditions, but in recent months the situation inside has spun out of control.

Ten people incarcerated at Rikers have died this year, at least five by suicide — the largest death toll at the jail in years. Gangs and other detainees are ushering other incarcerated people to and from their dorms. Relatives of those imprisoned there fear for their loved ones’ lives.

“My kid gets to go to court,” said Penny Wilkinson, the mother of Nicholas Caballero, 25, who is being held on the island as he awaits trial on assault and grand larceny charges. “I don’t want to see my child die in jail.”

The vast majority of people being held on Rikers have not been tried and are presumed innocent.

Here are answers to some of the questions about what is driving the problems at the facility:

When did the crisis start?

Rikers has long been characterized by dysfunction and violence, from its opening in 1935 to the culture of brutality and corruption that led to a sweeping federal investigation into the facility a decade ago.

But the contours of today’s crisis were shaped by the coronavirus, which has infected more than 2,200 employees of the Department of Correction so far, leading to widespread staffing shortages.

“It started during Covid and it’s just spiraled out of control,” said Alice Fontier, the managing director at the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem, of the staffing problems.

With such an enormous number of staff members out sick, the conditions at Rikers degraded. That caused a snowball effect as additional correction officers — who are granted unlimited sick time that was only recently subject to significant restraints — started to call in sick in unusually high numbers, or simply stopped showing up.

About a year after the pandemic began, a federal monitor noted , an “extraordinarily large number of staff were not reporting to work.” At the same time, the population of detainees at Rikers was growing.

More than 1,500 people had been released to help curb the spread of the coronavirus, but the jail population eventually surpassed prepandemic levels — and the rate of self-harm among those incarcerated there began to rise sharply.

By last month, the monitor found, staff shortages had compromised the safety of everyone on the island.

How could understaffing alone have made things so much worse?

Jail officials have reported that on average, 2,000 officers were out sick or unable to work on a single day at certain points this summer. It is unclear how many were actually ill; until last month, corrections officers merely had to supply a doctor’s note within two days of calling out sick.

The commissioner of the Department of Correction, Vincent Schiraldi, said at a hearing Wednesday that he suspected that some officers were using sick days as “an unlimited vacation pool.”

Their unavailability has slowed the basic functions of Rikers to a crawl, starting with the intake process, where people normally spend less than 24 hours receiving clothes, undergoing medical checkups and being assigned to housing units.

In recent months, those hourslong stretches have turned into days and even weeks, with people held in units that do not have beds or enough cells.

Social distancing is all but impossible and incarcerated people are not supplied with masks if they lose theirs or get them dirty, at a time when Covid-19 continues to affect them. Understaffing has led to delays in dispersing food, water and medication. Many people have also experienced delays in receiving urgent medical and mental health care, and getting to court .

According to those who have toured the complex recently, certain areas are covered in garbage and urine, and some people in custody are being held in tiny showers where there is barely enough room to stand.

Who has died at Rikers and how?

The dead include Wilson Diaz-Guzman , 30, who hanged himself in his cell in January, and Javier Velasco, 30, who was found unresponsive in March with a bedsheet wrapped around his neck. On Aug. 10, Brandon Rodriguez, 25, was found hanging in a shower in an intake area at the jail and on Aug. 30, Segundo Guallpa, 57, was found dead in what the Department of Correction described as a suspected suicide.

On Wednesday, the city’s chief medical examiner said that the death of Tomas Carlo Camacho , 48, in March, had also been a suicide. Mr. Camacho was found unresponsive and on his knees with his head through a small opening in the cell door known as a cuffing slot.

At least five more people have died on Rikers Island this year: Thomas Braunson III , 35, Richard Blake , 45, Jose Mejia Martinez , 35, Robert Jackson , 42 and, last week, Esias Johnson, 24.

Mr. Braunson died of an overdose and Mr. Blake of heart disease, according to the city. The causes of death of Mr. Martinez, Mr. Jackson and Mr. Johnson remain undetermined.

Allen Chey King, 51, who is being held at Rikers, said he found Mr. Johnson unresponsive in a dorm at the jail. Mr. Johnson had begged staff for medical attention in the two days leading up to his death, Mr. King said.

Guards tried to help, Mr. King said, but it seemed the clinic was backed up with patients.

“He said he was in great pain. His stomach was hurting,” Mr. King said. “He said he needed to go to clinic.”

Who is responsible for the deteriorating conditions?

Rikers is a city jail, but people are sent there because they are charged with having violated state law. That means that any attempt to solve the crisis there must occur at the tricky intersection of state and city politics.

A group of state lawmakers, city officials and public defenders held a news conference at Rikers on Monday, and called for a slate of actions to be taken by Gov. Kathy Hochul, Mayor Bill de Blasio and prosecutors and judges in New York City, who are bound by state law but can use their discretion to affect outcomes for individual defendants.

The lawmakers described having witnessed a humanitarian crisis during their tour of the facility, where they saw dozens of people without masks packed into cells with overflowing toilets, unable to see their lawyers because they have yet to be booked. In certain intake units, people were being held in showers and relieving themselves in plastic bags.

“It’s a nightmare back there,” said State Senator Jabari Brisport.

What can be done to fix things?

Mr. de Blasio on Tuesday announced a plan designed to improve conditions at Rikers , which included hiring contractors to accelerate repairs and to provide medical care for staff on duty. He also said correction officers who did not show up for work would be suspended without pay.

On Wednesday, 21 officers who were said not to have shown up to work were suspended, according to a union that represents the city’s jail officers.

In a statement, the union’s head, Benny Boscio Jr., said that the mayor could not discipline his way out of the staffing crisis.

“More heavy-handed suspensions will only ensure officers continue to work triple and quadruple shifts with no meals and no rest,” he said.

The mayor also set a goal to speed people through the intake process in 24 hours or less, and announced plans to send some police officers to staff the court buildings, freeing up other correction officers to help at Rikers.

Several of those who visited Rikers this week said that the mayor’s plan was inadequate and would do nothing to improve conditions immediately. The jail officers’ union, which has urged the city to hire thousands more staff members, called on the mayor to resign.

Lawmakers have asked Mr. de Blasio to use his powers to allow for the early release of certain incarcerated people, as he did last spring. And they asked the mayor to visit Rikers, which he has not done since June 2017.

Mr. de Blasio has been reluctant to permit the early release of more incarcerated people, and he has denied a report that said he was considering the release of some 180 people. New York City’s police commissioner has expressed strong opposition to any early release.

Lawmakers also called on Ms. Hochul to sign the Less is More Act, a parole reform bill that would stop people accused of violating parole from being automatically detained in jails, among other things.

On Tuesday, Cyrus R. Vance Jr., the Manhattan district attorney, and Alvin Bragg, his likely successor, also urged Ms. Hochul to sign the bill.

If she were to sign it, and to direct that it be implemented immediately, about 400 people at Rikers would be eligible for release.

Ms. Hochul has said that she is “concerned” about the conditions in city jails and that she would review the bill.

The lawmakers and advocates who visited Rikers on Monday also called for prosecutors and judges to stop sending people there while conditions remain dangerous, in part by ending the use of cash bail.

“Too many prosecutors and district attorneys across New York City are sentencing working-class New Yorkers to the possibility of death,” said Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani.

Jonah E. Bromwich is a courts reporter for the Metro desk. More about Jonah E. Bromwich

Jan Ransom is an investigative reporter on the Metro Desk focusing on criminal justice issues, law enforcement and incarceration in New York. More about Jan Ransom

How Rikers Island Jail In New York City Actually Works

Rikers Island is home to some of the most notorious and violent jails in the world. It is located in the East River in New York City. The majority of its detainees have not yet been convicted of a crime and are either remanded in custody or held on bail.

Vidal Guzman is a former member of the East Coast Bloods. He was incarcerated on Rikers Island when he was 16 and returned when he was 19.

Guzman discusses the conditions inside the New York City jail complex. He mentions corrupt guards, gang-controlled phones, and how illegal goods are smuggled in. He speaks about the history of the US jail system, how Rikers Island came to be, and the need for reform. He also addresses myths about Rikers being a prison and who is incarcerated there.

Guzman is a prominent voice in the Close Rikers campaign and the executive director of America on Trial. He is the founder of the End Qualified Immunity in NY and #FixThe13thNY campaigns. He left the criminal justice system at 24 and started working with the food-truck initiative Drive Change before becoming a criminal justice campaigner.

Check out his website or his Instagram, @iamvidalguzman.

More from How Crime Works

- Main content

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

Reimagining Rikers Island: A Better Alternative to NYC’s Four-Borough Jail Plan

Six months before the Covid-19 epidemic spread across New York City in early March, Mayor Bill de Blasio and the city council approved a plan to spend nearly $9 billion over the next half-decade to build four jails, one each in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The completion of the new jails, in turn, would allow the city to close Rikers Island, home to most existing jail facilities.

The mayor and the council are right in one respect: the jail facilities on Rikers are deficient. One way or another, New York must invest billions to make good on its promise to treat detainees—most of whom have not yet been convicted of any crime—with compassion and dignity.

But there are major flaws in the city’s plan. The construction of four new jails in dense urban neighborhoods, at enormous expense and risk to the city’s fiscal health, does not guarantee inmates the better care that the city has promised. By concentrating on location rather than on deeper-seated problems, the city may simply replicate Rikers’ problems elsewhere. Indeed, should the city fail to successfully execute its borough-based jails plan, it would even fall short of its ultimate, symbolic goal: closing Rikers.

The coronavirus crisis puts these flaws into sharper relief. At present, the city faces the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, billions—if not tens of billions—in tax revenue, and significant uncertainty over when recovery will begin and how strong it will be. As a result, New York simply has far less room for error than it did last fall, when it approved its plan to build new jails.

There is a better alternative: rebuild Rikers. This 400-acre island is an optimal location for multiple, welldesigned, low- to mid-rise jail facilities. Rikers is also New York’s only remaining open space near enough to the courthouses in all five boroughs to be a practical location for housing inmates in a sprawling setting—but far away enough from the general population to serve as a secure location. Figure 1 is a sketch of what a rebuilt Rikers Island might look like.

New York could turn Rikers’ fabled isolation into an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. The island’s geography presents an opportunity to experiment with giving inmates more freedom and flexibility than they could hope to experience in four new high-rise borough jails.

DOWNLOAD PDF

The Borough-Based Jails Plan: A Brief Overview

The ultimate goal of the new “borough-based jails plan,” according to the city, is “modern,” “humane” jails that are “smaller, safer, and fairer.”[ 1 ] Before Covid-19 spread, New York City’s jails, the majority of them on Rikers Island, were the home, at any given time, to nearly 6,000 daily inmates.[ 2 ] Most inmates are awaiting trial; that is, they are charged with, but not convicted of, a crime, and they cannot make bail or are not eligible for bail.

Rikers has long been a symbol of poor incarceration practices. Many of the island’s collection of nine low-rise jail facilities are outdated and poorly maintained. They lack basic provisions for personal hygiene and public health, forcing inmates to share toilets, for example. They also lack modern temperature controls, endangering the health and lives of inmates sensitive to heat or cold.[ 3 ] Such public-health deficiencies are even more urgent in the current pandemic, as corrections workers and inmates have tested positive for Covid-19. Indeed, the city has released nearly one thousand older and unhealthy inmates to protect their health.[ 4 ]

There are other problems. Cells and hallways are noisy and smelly.[ 5 ] Violence is prevalent: between 2008 and 2017, the city’s Department of Correction reported a doubling of inmate injuries, from 15,620 to 31,368, even as the inmate population declined 32%.[ 6 ] Deteriorating facilities and violence go together, as inmates are reported to have chipped off pieces of the decaying infrastructure to create weapons. Visitors have a difficult time coming to see inmates, as public transportation to the island is scarce. Once on the island, visitors must endure multiple security checks and additional bus rides from a central intake area to each jail facility, requiring more waiting.

To address the many long-standing deficiencies of Rikers Island, the mayor and the city council, in October 2019, approved a plan to build four new jails across New York City by 2026.[ 7 ] If all goes as planned, the city’s jail population would have fallen by more than half, making jails “smaller.” A better design would discourage violence, making jails “safer.” Jails would be located nearer to inmates’ homes, families, and friends, facilitating easier visits. Jails would also be closer to courts, helping to speed up the process between arraignment and trial outcome. The jails would offer outdoor space, natural sunlight, superior medical and mental-health care, and education, thus making the jails “fairer.”

The basic specifications for each jail[ 8 ] are as follows, although these deadlines are already subject to change as the city grapples with its coronavirus response.[ 9 ]

Financial Risks of the Jails Plan: At What Cost to the City’s Capital Budget?

Since mid-March, the state and city have mandated public-health closures of entire swaths of the city’s economy, including most retail, restaurant, and personal- services businesses. These closures will soon cause a steep falloff in tax revenues, likely far worse than what New York experienced after 9/11 or the 2007–08 financial crisis. Safeguarding the city’s capital budget for critical infrastructure that can support its fragile tax base has thus become paramount. Building four new jails, however, is the single biggest capital-construction project that the city government has embarked upon in more than a half-century—and the project is supposed to be finished on an aggressive schedule of six and a half years from mid-2020. The city estimates that the four borough jails will cost $8.7 billion in total.[ 10 ]

Even if the city builds the jails on time and on budget, $8.7 billion is a significant portion of the city’s 10-year capital budget—that is, the city’s schedule for long-term investments in infrastructure such as bridge repairs and restorations, bus and bike lanes, sanitation facilities, school buildings, and subsidized housing. Money that goes to the four-borough jail program is money that could have gone to other critical needs, including rebuilding the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway or repairing the New York City Housing Authority properties.

A comparison between the mayor’s January 2019 capital- budget proposal for the next decade,[ 11 ] which did not include funding for the four borough jails, and the mayor’s April 2019 proposal,[ 12 ] which did include such funding, illustrates this point. In January 2019, the projected capital (infrastructure) budget for the city’s justice system was $5.2 billion. By April, the justice system’s projected capital budget was $13.7 billion, driven by an increase in the corrections budget from $1.8 billion to $10 billion. The justice system now accounts for 12% of the overall $117 billion capital budget over the next 10 years, up from 5%.

For as long as the city’s economy continued to grow, committing $8.7 billion to borough jails did not cut the total amount of money that the city has to pay for other long-term needs. With the pandemic, the city must inevitably rethink its capital-budget priorities so that one experimental project does not overwhelm the rest of the scarcer money available for critical infrastructure.

Construction Risks: Can the City Build the Jails on Time and on Budget?

Overseeing the design and construction of four new complex high-rise buildings in dense urban neighborhoods simultaneously in little more than half a decade is an extraordinary undertaking, especially for a city government unaccustomed to overseeing projects of such scope. It is also the city’s largest complex infrastructure project in modern history.

The schedule is even more aggressive than originally intended. In April 2019, the city moved the timeline for the completion of the jails by one year, from 2027 to 2026, without explaining why the scope of the plan supported such compression.[ 13 ]

New York’s underground Third Water Tunnel is the closest rival to the jails plan. It costs $6 billion but spans five decades.[ 14 ] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s $11.1 billion East Side Access project will bring Long Island Rail Road trains below Grand Central Station. It is now a nearly two-decades-long undertaking.[ 15 ]

The jails plan is similar in scope to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s rebuilding of the World Trade Center—also a project involving complex highrise buildings with specific security needs. It took well more than a decade and cost $15 billion.[ 16 ] The East Side Access and World Trade Center projects, moreover, encountered significant cost and schedule overruns, despite their governing agencies’ greater experience in managing large-scale infrastructure projects.

New York City’s government regularly oversees contracts to rebuild roads and repair bridges, construct schools, and build sanitation and environmental-protection facilities. But it has little experience in overseeing the design and construction of four complex high-rise buildings in such a short time. As the city puts it, the project involves “complex construction on … severely constrained project site[s].”[ 17 ] Each jail must have a 100% reliable power source; three of the four facilities must include secure bridges or tunnels to adjacent or nearby court facilities in lower Manhattan, central Brooklyn, and central Queens.

New York City’s Department of Design and Construction, which will oversee the jails plan, has no experience in such a large-scale project and has performed poorly on smaller projects. The department, for instance, spent $41 million and a decade—well over the initial $30 million budget and 2017 deadline—to build a modest library in Queens’ Long Island City. Yet the facility has been sued for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act, the federal handicapped-accessibility law.[ 18 ]

“Design-build,” the framework through which the city will award contracts to build the four jails, theoretically reduces the risk of cost overruns to city taxpayers by holding winning bidders responsible for design and construction, thus alleviating discrepancies between the two. Yet in its initial bid documents, the city notes to potential bidders that it will “mitigat[e] the risk to the design-builder by providing for appropriate allowances, potential economic price adjustment provisions, and mitigating unknown subsurface conditions.” Agreeing to shoulder the cost of “economic price adjustment[s]” leaves the taxpayer open to unknown cost overruns.

Three of the jails will require extensive work just to prepare the sites. In Manhattan, the winning bidder must first demolish two existing nine- and 11-storey towers comprising more than half a million square feet. The demolition, in turn, requires asbestos mitigation. The Brooklyn and Queens sites require similar demolition and remediation. In the Bronx, the city must first determine where to relocate the NYPD’s existing “tow pound”—where hundreds of impounded vehicles are kept—before a contractor can begin construction.

Legal uncertainty puts additional pressure on the city’s already aggressive bidding and construction schedule. Community groups in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens,[ 19 ] for example, have filed suits in state court against the proposed jails for each of their respective boroughs, claiming that the city did not follow the proper procedure for approval of a change in land use. Even short-term delays caused by these legal proceedings will put additional pressure on the city to do more work in a shorter time frame, thus pushing up costs as contractors add extra shifts and overtime.

Operational Risks: Would Borough-Based Jails Solve Rikers’ Problems?

Even if the city completes the four jails on a reasonable schedule and budget, it may not solve Rikers’ existing problems. Success depends, above all else, on the city achieving a highly challenging feat: ensuring that the inmate population does not exceed the facilities’ significantly reduced capacity. The city must reduce inmate populations below today’s record-low levels, or the jails will not function as designed. If the city cannot reduce the jail population, operating close to, at, or above capacity would imperil its ability to safeguard inmates’ health.

As of late 2019, the average daily population in the city’s jails was 7,365 inmates; by early 2020, the population had fallen to 5,721, the first time it had fallen below 6,000 in decades. (In addition to Rikers, the city has two smaller jails in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and a floating jail barge near the Bronx; all three would close as part of the four-borough jail plan, and the inmates would be transferred to the new facilities in Brooklyn and Manhattan.)[ 20 ] The four new jails will have a cumulative capacity of just 3,544 beds.

The city arrived at this number politically. The mayor’s office needed the city council member in each neighborhood to vote for a new jail and had to repeatedly reduce the number of beds to get each council member to sign on.[ 21 ] In 2017, however, when the city began to explore reducing its jail capacity, the report that it commissioned concluded “that it is possible to reduce the jail population to less than 5,000 people over the next decade.”[ 22 ]

But the city has never explained how it abruptly arrived at a maximum figure of 3,544 inmates rather than 5,000. To keep inmates below this new capacity, the city must reduce the current average daily number of inmates to its projected goal of 3,300 inmates[ 23 ] within seven years, a 42% decrease.

New York City’s jail population has declined from a high of nearly 22,000 inmates on an average day in 1991.[ 24 ] And over the past seven years, from 2012 to 2019, the jail population declined by 45%. New York today has a low rate of incarceration: 97 inmates per 100,000 adults, compared with 241 in Los Angeles and 450 in Philadelphia.[ 25 ]

Unless crime falls significantly from today’s near record-low levels, the city will have a difficult time achieving its far more aggressive goal without endangering public safety. Of the city’s mid-2019 average daily population in jail, 3,261 people were there awaiting trial for a violent felony, and another 901 were serving a short sentence. Even under pressure to allow nonviolent inmates to leave jail in order to reduce the risk of spreading coronavirus, New York could come up with only 1,500 of candidates, not thousands, leaving the population just below 4,000, or above the planned capacity of the new jails, and only by making dubious decisions such as releasing an inmate awaiting trial for allegedly murdering his girlfriend.[ 26 ] Reducing the population, then, even to today’s population of the most violent of the alleged offenders, and people already sentenced, would still leave the new jails above capacity.[ 27 ]

If the city cannot safely reduce the inmate population to match the capacity of its new jails, it will face two unpalatable options: running overcrowded jails or keeping obsolete facilities on Rikers open. Overcrowded jails would endanger the city’s stated goal of creating a more humane environment; it would, for example, endanger the city’s goal to reduce violence among inmates. In short, falling back on Rikers in 2026 would represent a failure to deliver on its multibillion-dollar promise. Yet the city has quietly left itself this option; the city council has not yet rezoned Rikers to prohibit jails there.[ 28 ]

There are other operational risks to the promises that the new high-rise jails will be safer and fairer. For instance, the government has never explained how it would evacuate hundreds of inmates onto crowded New York City streets in a fire or other emergency. As for the danger that inmates pose to one another (and to guards): though the city has projected operational savings from its potential reduction in inmates, having to secure each floor of a high-rise jail—rather than one large, open space across a horizontal corridor—likely will require more corrections officers per inmate, not fewer.

The city’s conception for new jails is that of small, apartment-style housing units (one inmate per unit, with a private bathroom and shower) surrounding a common area on each floor, a big contrast from today’s communal cells, where up to dozens of people can share a toilet.[ 29 ] Yet the city has never explained how guards might respond quickly to a disturbance on any one floor, or how guards might transport inmates by elevator from one floor to another without the risk that inmates might encounter fellow inmates from rival gangs. Even in modern jails, efforts at privacy and dignity may require more supervision, not less. A private bathroom and shower may be a noble goal, but a guard must be on hand to ensure that no inmate is spending a potentially dangerous amount of time by himself in such a private space.

In light of the problems revealed by the current pandemic, New York must also consider the heightened public-health implications of dispersed jails in dense neighborhoods. Corrections officers who interact with an institutional population that is, by definition, at greater risk of infection would be going to and from work in populous areas, possibly by public transit, rather than driving to and from a secured island.

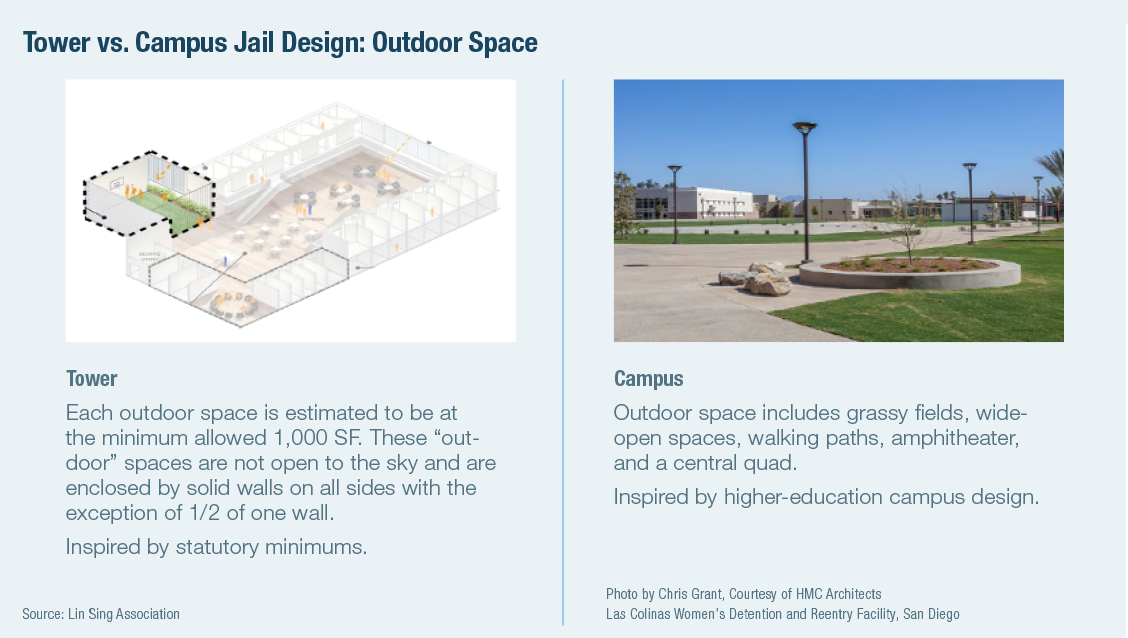

The city also faces significant challenges in being able to offer ample recreational, outdoor, therapeutic, and medical spaces within high-rise configurations. The existing Rikers Island jails offer supervised inmate access to a modest outdoor farm. It will be hard to re-create such an opportunity on the roof of a high-rise building, especially with security and power needs competing for space on that roof.

The New Borough Jails: Transportation

Rikers Island has two transportation problems: moving inmates to and from court; and encouraging family members and friends to visit inmates. Four-borough jails do not automatically solve either of these problems.

One motive behind the four-borough jail plan is to locate jails nearer courts, ensuring easier travel time from Rikers to the rest of the criminal-justice system. The new Bronx jail, however, will be two miles from the Bronx Criminal Court. At the other three jails, there is no guarantee that any given inmate will find himself incarcerated near the court that is relevant to his case. The four jails divide inmate capacity equally, but the distribution of inmates jailed before trial is not equal by borough. A recent survey of inmates found that 32.1% of the average daily population had been arraigned in Manhattan, for example. Only 15.1% were arraigned in the Bronx ( Figure 2 ).

Dividing the inmate population equally by borough ignores another issue: crime and incarceration rates are not distributed equally by borough, nor do offenders necessarily commit a crime in their home borough. The Bronx, for example, has the highest incarceration rate, proportionate to population, among the five boroughs.[ 31 ] An inmate from the Bronx who had allegedly committed a crime in Brooklyn could find himself detained in Queens, making it difficult for family and friends to visit.

Another Way: A Reimagined Rikers

As the city notes, its new jails must be a successful example of an “enduring design that supports justice reform for many decades to come.”[ 32 ] In that spirit— and before committing irrevocably to spending billions of dollars in taxpayer money on a flawed plan—the city council and mayor should pause the current bid process and consider an alternative: rebuilding Rikers as a modern jail.

To be sure, the city should demolish Rikers’ existing jail buildings. But it can do so one by one, taking advantage of the fact that Rikers is at only 60% of its capacity. The city can rebuild a jail campus in place and transfer inmates from old to new facilities as each new facility opens, thus avoiding a high-pressure deadline.

By rebuilding Rikers, New York can avoid significant risks posed by the borough jails plan:

- the risk that the cost of four new jails will overwhelm the rest of the city’s capital-investment priorities after the coronavirus pandemic;

- the risk that the city cannot complete the project on time, on budget, and to stated specifications; and

- the risk that the jails will not have enough capacity for the inmate population.

Finally, New York can avoid the most significant risk of all: that shortfalls in achieving the goals of the borough jails would force the city to return to Rikers’ current outdated, deficient buildings to house an overflow of inmates. Indeed, as coronavirus hit Rikers, the city was forced to reopen a previously shuttered jail on the island to keep inmates spaced farther apart.[ 33 ]

Bill Bialosky, a New York City architect, suggests a rough prototype. Working in collaboration with the Lin Sing Association, a Chinese-American advocacy group in lower Manhattan (which opposes a nearby neighborhood jail), Bialosky has concluded that a revamped Rikers would be far superior to four high-rise jails because the “campus” model for jails, just as it is for schools, is far superior to the “tower” model ( Figure 3 ). He has drawn up a preliminary sketch (Figure 1) to illustrate the possibilities for Rikers as well. In fact, the jails and prisons that city officials visited as models for New York’s borough-based plans are campus-style jails, not high-rises.[ 34 ]

Examples of successful, modern, low- to mid-rise jails, by contrast, include the Van Cise–Simonet Detention Center in Denver (completed in 2010) and San Diego’s Las Colinas Women’s Detention and Reentry Facility (completed in 2014).

At Van Cise ( Figure 4 ), inmates stay in dormitory-style housing that features natural lighting and spontaneous recreation opportunities.[ 35 ] Inmates can walk to decentralized medical clinics as well as therapeutic and recreational activities.

At Las Colinas ( Figure 5 ), separate facilities house different functions, from sleeping to eating to recreation and education, with inmates getting outdoor exercise as guards escort them among facilities. The jail’s architects and designers paid attention to light and acoustics to create an environment to soothe, not agitate, detained individuals.[ 36 ]

Yet both these facilities are low-rise; the taller of the two, Van Cise, is five storeys.

For safety, new jails on Rikers would also offer better options than high-rise towers in dense urban neighborhoods, such as a need for evacuation to secure refuge points in the case of fire or other danger. Similarly, visitors to new jails would have ample room and time to go through well-staffed security entrances equipped with modern contraband-detection machines. As for fairness: new jails could offer far more natural outdoor space for recreation and therapy, including farming and animal husbandry, than can indoor high-rise spaces.

Finally, though the city’s goal to reduce its inmate population is noble, it could rebuild a new Rikers Island with extra capacity, ensuring that new jails are not overcrowded and not harming inmates’ quality of life and public-health outlook.

A Reimagined Rikers: Financial Benefits

Rebuilding Rikers Island could achieve significant cost savings compared with building four separate new jails. Material and labor costs will be the same. However, the city could save on the logistical costs of setting up four separate construction sites in four separate dense urban neighborhoods—which makes everything from pouring concrete to accepting delivery of rebar more difficult.[ 37 ] These overhead costs generally constitute 20% of a large project, or nearly $2 billion; saving 20% on this portion of the project, in turn, would yield savings of over $300 million. Moreover, in building on Rikers, the city would have more deadline flexibility. It could simply transfer inmates from an older facility to a newer one as each building opens, without having to scramble to meet the current drop-dead symbolic goal of closing Rikers.

In addition, eventually, the city could sell the Manhattan and Brooklyn jail sites to developers for midrise market-rate housing, earning a profit that it could invest in a rebuilt Rikers. The Queens and Bronx sites are good candidates for below-market, working-class and middle-class housing, though such projects would likely require subsidy. In fact, the city had once considered the Bronx site for such “affordable” housing.[ 38 ]

A Reimagined Rikers: What About the Drawbacks?

Rebuilding Rikers requires upgrading the inadequate transportation services for visitors. It also requires environmental remediation. Neither hurdle is insurmountable— and the city must address them, anyway, in whatever it decides to build at Rikers when it no longer uses the island for jails.

There are two ways to solve the current challenges faced by visitors to Rikers. First, to supplement the MTA bus, which provides service from Queens every 12 minutes,[ 39 ] the city can provide more frequent free shuttle service from Harlem and Brooklyn, increasing the service from its current 45–60-minute waits.[ 40 ] The existing bus service to Rikers costs the city $1.6 million annually; expanding this service would be a negligible expense, compared with building four borough jails.[ 41 ]

More ambitiously, the city could integrate Rikers Island into its five-borough fast-ferry system. As architect Bialosky points out, ferries to Rikers from Astoria in Queens and Soundview in the Bronx would provide far faster access than does current mass transportation. The city currently spends $60 million annually to subsidize its existing six-route ferry system; adding a limited route to Rikers likely would cost in the low tens of millions of dollars annually, including the cost of debt on the initial construction of a pier.[ 42 ]

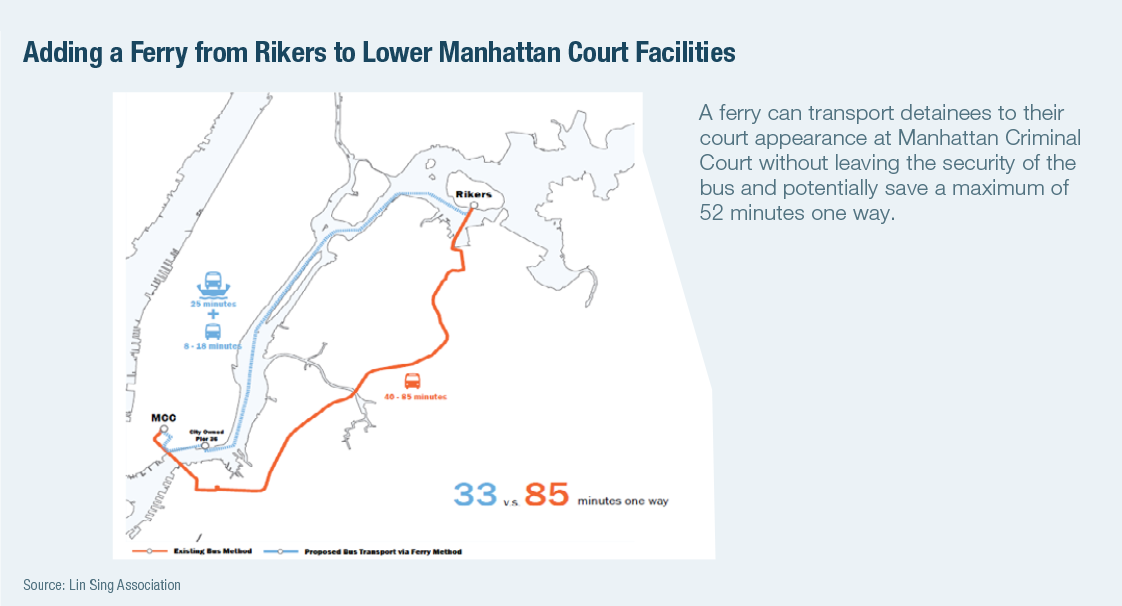

Ferries could also provide the city with a better way to transport inmates to and from Manhattan Criminal Court ( Figure 6 ). A ferry from Rikers to lower Manhattan court facilities could “transport detainees to their court appearance[s],” says Bialosky, “without leaving the security of the bus.” He adds that it might save “52 minutes one way.” Similar ferry service to Rikers from Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx could cut inmate-commute trips, as well.

Further, as the city remakes its street space to provide priority access to MTA buses, it can integrate buses to and from Rikers in bus-only lanes along major thoroughfares across the boroughs.

The second major hurdle that the city faces in reimagining Rikers is environmental remediation. Rikers is built on landfill, which emits noxious methane gas.[ 43 ] The island also requires flood protection. The city has never comprehensively cataloged Rikers’ environmental challenges, or estimated the cost required to address them. Yet environmental remediation and flood protection are likely prerequisites for many other future uses of Rikers Island and, here again, the costs are likely less than those associated with borough-based jails.

New York’s four-borough jails plan would require significant taxpayer investment and government competence to execute on time and on budget. Yet executing this plan exactly as laid out may not even pay off, in terms of helping the city achieve its goals of smaller, safer, and fairer jails. There is no guarantee that smaller jails in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens, built in constricted highrise environments, can successfully provide ample outdoor space or ample therapeutic space. There is no guarantee that high-rise jails can provide visitors with a better, faster experience in overcoming transportation and security hurdles. Should the jails ever exceed their 3,300-inmate capacity on a sustained basis, overcrowding would make it even harder to achieve the goals of safety and fairness.

No one disputes that the existing Rikers facilities need razing. Before awarding multibillion-dollar designand- build contracts that put the city on a path of no return, though, the mayor and city council should halt this process. It is not too late. The city’s Department of Design and Construction does not anticipate awarding a contract for the first two jails, in Manhattan and the Bronx, until September and November 2021, respectively.[ 44 ] The city should use this time to invite architects and developers to propose their own visions of what a reimagined Rikers could look like.

Opening these new jails would, in turn, allow the city to achieve another stated aim: the closure of all existing, obsolete jails on Rikers Island. Rikers, for more than eight decades the site of most of the city’s incarceration facilities, is now shorthand for failure. “Obviously, we’re going to get off Rikers Island,” the mayor said last year, in response to the news that an inmate there had attempted to hang himself. “We get out of Rikers, and we get into the kind of facilities that are modern.”[ 45 ] But why not stay on Rikers, and accomplish the same goal, transforming Rikers from failure to success?

See endnotes in PDF.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Further Reading

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Public Safety

- Publications

- Research Integrity

- Press & Media

EIN #13-2912529

- Facilities Locations

Facilities Overview

The Department provides for the care and custody of people ordered held by the courts and awaiting trial or who are convicted and sentenced to one year or less of jail time.

For more information on the city’s Borough Based Jails plan, please visit the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice website, HERE .

Facility Locations

Active Rikers Island Facilities

Eric M. Taylor Center (EMTC) Built in 1964 and expanded in 1973, EMTC previously housed males in custody sentenced to terms of one year or less. Most of its housing was dormitory-style. The facility, previously designated the Correctional Institution for Men, was renamed on July 14, 2000, in honor of retired Chief of Department Eric M. Taylor. EMTC closed in March 2020, and almost immediately reopened in March 2020 for new intakes showing symptoms and people in custody who had tested positive for COVID-19.

George R. Vierno Center (GRVC) Opened in 1991 and was named after a former Chief of Department and Acting Commissioner. GRVC was expanded in 1993. The facility houses detained and sentenced male adults.

North Infirmary Command (NIC) Consists of two separate buildings one of them the original Rikers Island Hospital built in 1932. It houses people in custody with acute medical conditions and require infirmary care, or have a disability that requires housing that is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. NIC also houses some general population detainees.

Otis Bantum Correctional Center (OBCC) Opened in June 1985, it was completed in less than 15 months using modern design and construction methods. OBCC has dormitory and cell housing. The jail was named for its second Warden. OBCC houses detained male adults.

Robert N. Davoren Center (RNDC) Opened in 1972, the jail was formally dedicated the Robert N. Davoren Center in May 2006 in honor of a former Chief of Department. RNDC primarily houses detained and sentenced males and young adults.

Rose M. Singer Center (RMSC) Opened in June 1988, RMSC is a 800-bed facility for female detainees and sentenced women in custody. Subsequent additional modular housing was added. In 1985, the Department’s first nursery was born, featuring a 25-bed baby nursery. RMSC was named after an original member of the New York City Board of Correction.

West Facility – Communicable Disease Unit (WF) Opened in the fall of 1991, WF was constructed of ‘Sprungs’ - rigid aluminum-framed structures covered by a heavy-duty plastic fabric. The facility includes single-cell units, some of which make up the Department's Communicable Disease Unit (CDU). Other cells house detainees separate and apart from the CDU.

Hospital Units

The Department maintains secure facilities in City hospitals: Elmhurst Hospital Prison Ward (EHPW), Queens - for female detainees.

Other Rikers Island Facilities - (Does not house people in custody)

George Motchan Detention Center (GMDC)

Originally opened in 1971 as the Correctional Institution for Women, the jail became a male detention center with the 1988 opening of the Rose M. Singer Center for women and was renamed in memory of a 17-year veteran Correction Officer fatally shot in the line of duty. GMDC closed in 2018 and is no longer used to house people in custody. GMDC is currently used as a Training Academy annex and its former visit house as a wellness center for DOC staff.

Benjamin Ward Visit Center

The Benjamin Ward Visit Center serves the various jail facilities on Riker's Island. All visitors must coordinate their visits through the Benjamin Ward Visit Center. The Visit Center is located at 18-31 Hazen St. East Elmhurst, NY 11370.

Closed DOC Facilities

James A. Thomas Center (JATC) Formerly the House of Detention for Men, this 1,200-bed, all-cell jail was renamed in honor of the Department's first African-American warden. Built in the early 1930s as Rikers Island's first permanent jail, the landmark structure is no longer in use.

Brooklyn Detention Complex (BKDC) Built on Atlantic Avenue in 1957, the facility housed male detainees most of whom were undergoing the intake process or awaiting trial in Kings County (Brooklyn) and Richmond County (Staten Island) courts. BKDC closed in December 2020.

Manhattan Detention Complex (MDC) This lower Manhattan facility consists of two buildings designated the North and South Towers, connected by a bridge. The North Tower was opened in 1990. The South Tower, formerly the Manhattan House of Detention, or the "Tombs," was opened in 1983, after a complete remodeling. The complex houses detainee and sentenced males, most of them undergoing the intake process or facing trial in New York County (Manhattan).

Queens Detention Complex (QDC) The Queens Detention Complex (QDC) is not a working jail and does not house people in custody. QDC includes court facilities, where people in custody await court appearances and for the intake process. Portions are also used as a space for television/movie production filming.

Vernon C. Bain Center (VCBC) A five-story jail barge built in New Orleans to DOC specifications, the facility houses detained male adults. Opened in the Fall of 1992, it is named in memory of a former Warden who died in a car accident. It serves as the intake facility for the Bronx.

Anna M. Kross Center (AMKC) Completed in 1978, and named for DOC's second female commissioner, AMKC houses detained and sentenced male adults in a facility spread over 40 acres. AMKC is the largest facility on Rikers Island.

Rikers Island opens new kid-friendly visitation room at the George R. Vierno Center

In may, a similar visitation room opened in the area housing women..

News 12 Staff

Jun 17, 2024, 11:41 AM

Updated yesterday

More Stories

HEAT ALERT: Very warm and humid conditions to kick off summer season

3 Hudson Valley school districts hold revised budget votes

Inaugural Black Legacy Awards and Juneteenth Awards Dinner held in Hempstead

Long Beach City Council unanimously approves starting beach season earlier

Voters in Sachem and West Babylon school districts approve budgets

HEAT ALERT: Scorching high temperatures remain in place across New Jersey

More from news 12.

US Department of Education resolves discrimination complaints at CUNY

$375K grant to subsidize child care costs for women working 'nontraditional' jobs

Police: Justin Timberlake charged with DWI in Sag Harbor

Half a million immigrants could eventually get US citizenship under a new plan from Biden

Retired Bay Shore elementary school teacher accused of sexually abusing students faces child porn charges

NJ Transit rail service into and out of NY Penn Station delayed up to 90 minutes due to disabled train

Walt Kane discusses KIYC documentary on New Jersey’s treatment of sex assault survivors

NYC officials: Avoid the outdoors, stay cool during oppressive heat in the Bronx

Two Trumbull softball players awarded scholarships for academics and community service

Some NJ schools announce early dismissals as state braces for heat wave

Crews to begin repairing sinkhole that ripped through Hoboken waterfront walkway

MTA announces new bus lane camera enforcement on 14 NYC routes

Attorney claims NYC's 'Operation Padlock to Protect' cannabis campaign is unconstitutional

Inwood residents voice safety concerns after deadly triple shooting

Bronx mother claims daughter assaulted at school, proper action wasn't taken

Man sentenced to up to 21 years in prison for crash that killed married couple in Laurel Hollow

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Beginning May 10, 2023: In-person visits are offered on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays. To have an in-person visit, visitors must arrive at Rikers Island Central Visits or VCBC during the registration hours. Please see registration hours below: Wednesday and Thursday: 2:00 PM - 6:00 PM. Saturday and Sunday: 8:00 AM - 12:00 PM.

Even after Rikers Island officially opened in 1932, landfill continued to be added to the property until 1943, enlarging the original 90-acre plot of land to its current size of roughly 415 acres.

Visiting Schedule - DOC. Inmate Visit Schedule - June 2021. As of June 25, 2021, In-Person Visits are only available on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Televisits are offered on Saturdays and Sundays. A-L = Visits open to inmates whose last name begins with any letter between A and L, inclusive. M-Z = Visits open to inmates whose last name ...

Visiting the notorious Rikers jail complex is an involved process that includes multiple bus trips, physical screenings, and ID checks. New York City's notorious Rikers Island jail complex has ...

at 3rd Avenue. Brooklyn - Jay Street, between Fulton Street and Willoughby Street. All persons 16 years of age and older must present valid current identification. Rikers Visit buses are ADA compliant and staffed by drivers with Vision Zero training. In-Person Visits are available on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays. The typical one ...

De Blasio and Johnson agreed to close the jail complex by 2026 and open four new jails at a total cost of $8.7 billion. A week later, the City Council approved the deal. August 2020. Gothamist acquired planning documents that showed delays would stretch the closing of Rikers Island well into 2027. October 2020.

7 Rikers Island Shuttle to and from Jail Facility 8 10.. Jail Facility Remember to Bring: Identification (ID) 2 quarters for lockers. You will get both quarters back. Shuttle corresponds to the jail you are visiting and leaves every 20-30 minutes. 1. Take the Q100 over the bridge to Rikers Island 2.

Rikers Island is a 413-acre (167.14-hectare) [1] [2] prison island in the East River in the Bronx [3] that contains New York City 's largest jail. [4] [5] Named after Abraham Rycken, who took possession of the island in 1664, the island was originally under 100 acres (40 ha) in size, but has since grown to more than 400 acres (160 ha).

Inside Rikers Island, there's an increase in violence, and it's not just attacks amongst inmates. Assaults against corrections officers are up by 23%. One lawmaker said dogs in kennels are treated ...

Published Sept. 15, 2021 Updated Nov. 8, 2021. New York City's notorious Rikers Island jail complex has long had a reputation for brutal conditions, but in recent months the situation inside has ...

Dylan Brzezinski and Ju Shardlow. Dec 28, 2023. Rikers Island is home to some of the most notorious and violent jails in the world. It is located in the East River in New York City. The majority ...

How to get there. There's only one way on and off Rikers Island: the Rikers Island Bridge. This helps to keep the prison secure, but it can also give visitors fits. The New York City Department of Correction recommends that you take the bus to Rikers: the Q101 from Manhattan, which delivers you directly to the Rikers Island entrance at Hazen ...

Richards' tour comes as the future of Rikers Island hangs in the balance. The population of the jail has steadily increased since Mayor Eric Adams took office, threatening the feasibility of the city's legally mandated closure plan, which involves opening four borough-based jail facilities throughout the city to replace Rikers Island ...

FOX 5's Lisa Evers gets an exclusive look inside the notorious Rikers Island jail complex with Louis Molina, the new commissioner of the department of correc...

August 29, 2022 at 12:23 PM PDT. Listen. 2:19. An improvement in staffing levels at New York's troubled Rikers Island jail complex has had a positive effect on the conditions there, a delegation ...

The ultimate goal of the new "borough-based jails plan," according to the city, is "modern," "humane" jails that are "smaller, safer, and fairer."[] Before Covid-19 spread, New York City's jails, the majority of them on Rikers Island, were the home, at any given time, to nearly 6,000 daily inmates.[] Most inmates are awaiting trial; that is, they are charged with, but not ...

Hell. Inhumane. Disgusting. These are some of the words used to describe Rikers Island, New York's massive jail complex, by Benji Lozano, who spent five mont...

Today, Rikers is the Department of Corrections' main base of operation and the primary jail complex for New York City, holding about 11,000 inmates on any given day. Most are offenders serving ...

Other Rikers Island Facilities - (Does not house people in custody) George Motchan Detention Center (GMDC) Originally opened in 1971 as the Correctional Institution for Women, the jail became a male detention center with the 1988 opening of the Rose M. Singer Center for women and was renamed in memory of a 17-year veteran Correction Officer ...

13 reviews. 16 helpful votes. 2. Re: visiting sing sing or Rikers Island. 16 years ago. Perhaps Nessa has been misinformed. Rikers/Sing Sing, while famous, are not like visiting the historic closed prison of Alcatraz in San Francisco. They are currently open, working prisons and in the US you cannot visit as a tourist.

Rikers Island consists mainly of men's jail facilities that house around 6,000 people. Child-friendly exhibits will be added to those facilities over the next year, the museum said in a statement.

It was February 1, 1957 and Northeast Airlines Flight 823 would remain airborne for about one minute before plunging from the sky and crashing onto Rikers Island, New York's 400 acre prison complex.

17m ago. Rikers Island is opening a new kid-friendly visitation room Monday at the George R. Vierno Center, which houses male inmates. The Children's Museum of Manhattan helped design the room with the goal to allow kids and grandkids to focus on imaginative play rather than the fact that they are inside a jail complex visiting their dad or ...