Steve Perry

Who Is Steve Perry?

Steve Perry played in several bands before joining Journey in 1977. The band achieved tremendous pop rock success with its 1981 album Escape , which featured the now-classic "Don't Stop Believin'." As the group's lead singer, Perry became one of the era's most famous singers. He also had some hits on his own, including "Oh Sherrie." Perry left Journey in 1987, and except for a brief reunion, he remains a solo artist.

While attending high school in Lemoore, California, Perry played drums in the marching band. He tried college for a while, performing in the choir, but eventually abandoned school for his musical dreams. Hoping to break into the business, he moved to Los Angeles for a time. There, he worked a number of jobs, including singing on commercials and serving as an engineer in a recording studio. All the while, Perry played with a number of different groups as a vocalist and drummer. He seemed to be on the edge of a breakthrough with the group Alien Project, when it suddenly disbanded — tragically, one of its members was killed in a car crash.

Journey: "Oh Sherrie" and "Don't Stop Believin'"

In 1977, Perry caught his big break, landing a gig as the vocalist for Journey, which began performing as a jazz rock group in the early 1970s, in San Francisco. With Perry on board, the band moved more toward mainstream rock, and began to see some chart success with the first album with Perry, 1978's Infinity . The band's ode to San Francisco, "Lights," became a minor hit as did "Wheel in the Sky" and "Anytime."

Journey broken into the Top 20 with "Lovin', Touchin', Squeezin'" on their next album, Evolution (1979). Buoyed by such hits as "Open Arms," "Who's Crying Now" and "Don't Stop Believin'," Escape (1981) became the band's first No. 1 album, selling more than 7 million copies. While the band was hugely popular with music fans, many critics were less than kind.

By the early 1980s, Journey had emerged as one of rock's top acts. Perry proved that while he may have been short in stature, he possessed one of the era's biggest and most versatile voices. He was equally adept at ballads, such as "Open Arms," and at rock anthems, such as "Any Way You Want It." Behind the scenes, Perry helped write these songs and many of the band's other hits. He penned their most enduring song, "Don't Stop Believin'," with guitarist Neal Schon and keyboardist Jonathan Cain.

Journey continued to be one of the era's top-selling acts, with 1983's Frontiers . The album featured such songs as "Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)" and "Faithfully." To support the recording, the band undertook an extensive world tour. Around that time, Journey also became the first band to license their music and likenesses for a video game.

With 1986's Raised on Radio , Journey enjoyed another wave of success. However, Perry was ready to part ways with his bandmates. Perry left the band in 1987 after the album tour. In a statement to People magazine, Perry explained: "I had a job burnout after 10 years in Journey. I had to let my feet hit the ground, and I had to find a passion for singing again." Perry was also struggling with some personal issues at the time; his mother had become very sick, and he spent much of his time caring for her before her death.

Perry reunited with Journey in 1996, for the reunion album Trial By Fire , which reached as high as the No. 3 on the album charts. But health problems soon sidelined the famous singer—a hip condition, which led to hip replacement surgery—and his bandmates decided to continue on without him.

Solo Projects

While still with Journey, Perry released his first solo album, Street Talk (1984). The recording sold more than 2 million copies, helped along by the hit single, "Oh Sherrie." Burnt out after splitting with Journey, Perry took some time out before working on his next project.

Nearly a decade later, Perry re-emerged on the pop-rock scene with 1994's For the Love of Strange Medicine . While the album was well-received—one ballad, "You Better Wait," was a Top 10 hit—Perry failed to reach the same level of success that he had previously enjoyed. In 1998, he provided two songs for the soundtrack of Quest for Camelot , an animated film. Perry also released Greatest Hits + Five Unreleased that same year.

Recent Years

While he has largely stayed out of the spotlight, Perry continues to be heard in movies and on television. His songs are often chosen for soundtracks, and Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'" even played during the closing moments of the hit crime-drama series The Sopranos in 2007. In 2009, a cover version of the song was done for the hit high school musical show Glee , which introduced a new generation to Perry's work.

According to several reports, Perry began working on new material around 2010. He even built a studio in his home, which is located north of San Diego, California. "I'm finishing that room up and I've written a whole bunch of ideas and directions, all over the map, in the last two, three years," Perry told Billboard in 2012.

In 2014, Perry broke from his self-imposed exile from the concert stage. He appeared with the Eels at several of their shows. According to The Hollywood Reporter , Perry explained that "I've done the 20-year hermit thing, and it's overrated." His return to performing "has to do with a lot of changes in my life, including losing my girlfriend a year ago and her wish to hear me sing again" — referring to his romance with Kellie Nash, who died in late 2012 from cancer.

Although Perry and his old bandmates had long since ventured in separate directions, the group did reunite for their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in April 2017.

In the meantime, the singer began recording again. On August 15, 2018, he released his first new song in 20 years, the ballad "No Erasin." The track arrived ahead of his new album, Traces , his first full-length studio recording since For the Love of Strange Medicine in 1994.

Regardless of what the future holds, Perry has already earned a place in rock history. Rolling Stone magazine named him one of music's top 100 singers. According to American Idol judge and former Journey bassist, Randy Jackson, Perry's voice is one of kind. "Other than Robert Plant, there's no singer in rock that even came close to Steve Perry," Jackson said. "The power, the range, the tone—he created his own style. He mixed a little Motown, a little Everly Brothers, a little Zeppelin."

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Steve Perry

- Birth Year: 1949

- Birth date: January 22, 1949

- Birth State: California

- Birth City: Hanford

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Steve Perry was the lead singer of pop rock band Journey from 1977 to 1987. He is known for having a wide vocal range, which can be heard on such popular hits as "Don't Stop Believin'" and "Oh Sherrie."

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Steve Perry Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/musicians/steve-perry

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 23, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous Musicians

Why Amy Winehouse and Her Ex-Husband Didn’t Last

Randy Travis

The Life and Hip-Hop Legacy of DJ Mister Cee

Jon Bon Jovi

How to Score Tickets to Pitbull's Tour

Mick Jagger

Taylor Swift and Joe Alwyn’s Private Relationship

Taylor Swift

How Dickey Betts Wrote “Ramblin’ Man“

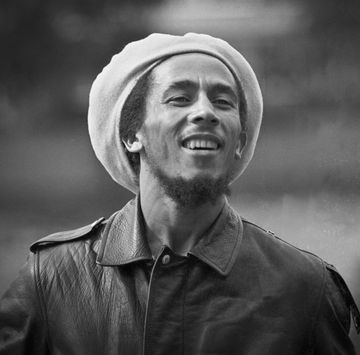

How Did Bob Marley Die?

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Steve Perry Walked Away From Journey. A Promise Finally Ended His Silence.

By Alex Pappademas

- Sept. 5, 2018

MALIBU, Calif. — On the back patio of a Greek restaurant, a white-haired man making his way to the exit paused for a second look at one of his fellow diners, a man with a prominent nose who wore his dark hair in a modest pompadour.

“You look a lot like Steve Perry,” the white-haired man said.

“I used to be Steve Perry,” Steve Perry said.

This is how it goes when you are Steve Perry. Everyone is excited to see you, and no one can quite believe it. Everyone wants to know where you’ve been.

In 1977, an ambitious but middlingly successful San Francisco jazz-rock band called Journey went looking for a new lead singer and found Mr. Perry, then a 28-year-old veteran of many unsigned bands. Mr. Perry and the band’s lead guitarist and co-founder, Neal Schon, began writing concise, uplifting hard rock songs that showcased Mr. Perry’s clean, powerful alto, as operatic an instrument as pop has ever seen. This new incarnation of Journey produced a string of hit singles, released eight multiplatinum albums and toured relentlessly — so relentlessly that in 1987, a road-worn Mr. Perry took a hiatus, effectively dissolving the band he’d helped make famous.

He did not disappear completely — there was a solo album in 1994, followed in 1996 by a Journey reunion album, “Trial by Fire.” But it wasn’t long before Mr. Perry walked away again, from Journey and from the spotlight. With his forthcoming album, “Traces,” due in early October, he’s breaking 20 years of radio silence.

Over the course of a long midafternoon lunch — well-done souvlaki, hold all the starches — Mr. Perry, now 69, explained why he left, and why he’s returned. He spoke of loving, and losing and opening himself to being loved again, including by people he’s never met, who know him only as a voice from the Top 40 past.

And when he detailed the personal tragedy that moved him to make music again, he talked about it in language as earnest and emotional as any Journey song:

“I thought I had a pretty good heart,” he said, “but a heart isn’t really complete until it’s completely broken.”

IN ITS ’80S heyday, Journey was a commercial powerhouse and a critical piñata. With Mr. Perry up front, slinging high notes like Frisbees into the stratosphere, Journey quickly became not just big but huge . When few public figures aside from Pac-Man and Donkey Kong had their own video game, Journey had two. The offices of the group’s management company received 600 pieces of Journey fan mail per day.

The group toured hard for nine years. Gradually, that punishing schedule began to take a toll on Journey’s lead singer.

“I never had any nodules or anything, and I never had polyps,” Mr. Perry said, referring to the state of his vocal cords. He looked around for some wood to knock, then settled for his own skull. The pain, he said, was more spiritual than physical.

[ Never miss a pop music story: Sign up for our weekly newsletter, Louder. ]

As a vocalist, Mr. Perry explained, “your instrument is you. It’s not just your throat, it’s you . If you’re burnt out, if you’re depressed, if you’re feeling weary and lost and paranoid, you’re a mess.”

“Frankly,” Mr. Schon said in a phone interview, “I don’t know how he lasted as long as he did without feeling burned out. He was so good, doing things that nobody else could do.”

On Feb. 1, 1987, Mr. Perry performed one last show with Journey, in Anchorage. Then he went home.

Mr. Perry was born in Hanford, Calif., in the San Joaquin Valley, about 45 minutes south of Fresno. His parents, who were both Portuguese immigrants, divorced when he was 8, and Mr. Perry and his mother moved in next door to her parents’. “I became invisible, emotionally,” Mr. Perry said. “And there were places I used to hide, to feel comfortable, to protect myself.”

Sometimes he’d crawl into a corner of his grandparents’ garage with a blanket and a flashlight. But he also found refuge in music. “I could get lost in these 45s that I had,” Mr. Perry said. “It turned on a passion for music in me that saved my life.”

As a teen, Mr. Perry moved to Lemoore, Calif., where he enjoyed an archetypally idyllic West Coast adolescence: “A lot of my writing, to this day, is based on my emotional attachment to Lemoore High School.”

There he discovered the Beatles and the Beach Boys, went on parked-car dates by the San Joaquin Valley’s many irrigation canals, and experienced a feeling of “freedom and teenage emotion and contact with the world” that he’s never forgotten. Even a song like “No Erasin’,” the buoyant lead single from his new LP has that down-by-the-old-canal spirit, Mr. Perry said.

And after he left Journey, it was Lemoore that Mr. Perry returned to, hoping to rediscover the person he’d been before subsuming his identity within an internationally famous rock band. In the beginning, he couldn’t even bear to listen to music on the radio: “A little PTSD, I think.”

Eventually, in 1994, he made that solo album, “For the Love of Strange Medicine,” and sported a windblown near-mullet and a dazed expression on the cover. The reviews were respectful, and the album wasn’t a flop. With alternative rock at its cultural peak, Mr. Perry was a man without a context — which suited him just fine.

“I was glad,” he said, “that I was just allowed to step back and go, O.K. — this is a good time to go ride my Harley.”

JOURNEY STAYED REUNITED after Mr. Perry left for the second time in 1997. Since December 2007, its frontman has been Arnel Pineda, a former cover-band vocalist from Manila, Philippines, who Mr. Schon discovered via YouTube . When Journey was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame last April, Mr. Pineda sang the 1981 anthem “Don’t Stop Believin’,” not Mr. Perry. “I’m not in the band,” he said flatly, adding, “It’s Arnel’s gig — singers have to stick together.”

Around the time Mr. Pineda joined the band, something strange had happened — after being radioactively unhip for decades, Journey had crept back into the zeitgeist. David Chase used “Don’t Stop Believin’” to nerve-racking effect in the last scene of the 2007 series finale of “The Sopranos” ; when Mr. Perry refused to sign off on the show’s use of the song until he was told how it would be used, he briefly became one of the few people in America who knew in advance how the show ended.

“Don’t Stop Believin’” became a kind of pop standard, covered by everyone from the cast of “Glee” to the avant-shred guitarist Marnie Stern . Decades after they’d gone their separate ways, Journey and Mr. Perry found themselves discovering fans they never knew they had.

Mark Oliver Everett, the Los Angeles singer-songwriter who performs with his band Eels under the stage name E, was not one of them, at first.

“When I was young, living in Virginia,” Mr. Everett said, “Journey was always on the radio, and I wasn’t into it.”

So although Mr. Perry became a regular at Eels shows beginning around 2003, it took Mr. Everett five years to invite him backstage. He’d become acquainted with Patty Jenkins, the film director, who’d befriended Mr. Perry after contacting him for permission to use “Don’t Stop Believin’” in her 2003 film “Monster.” (“When he literally showed up on the mixing stage the next day and pulled up a chair next to me, saying, ‘Hey I really love your movie. How can I help you?’ it was the beginning of one of the greatest friendships of my life,” Ms. Jenkins wrote in an email.) Over lunch, Ms. Jenkins lobbied Mr. Everett to meet Mr. Perry.

They hit it off immediately. “At that time,” Mr. Everett said, “we had a very serious Eels croquet game in my backyard every Sunday.” He invited Mr. Perry to attend that week. Before long, Mr. Perry began showing up — uninvited and unannounced, but not unwelcome — at Eels rehearsals.

“They’d always bust my chops,” Mr. Perry said. “Like, ‘Well? Is this the year you come on and sing a couple songs with us?’”

At one point, the Eels guitarist Jeff Lyster managed to bait Mr. Perry into singing Journey’s “Lights” at one of these rehearsals, which Mr. Everett remembers as “this great moment — a guy who’s become like Howard Hughes, and just walked away from it all 25 years ago, and he’s finally doing it again.”

Eventually Mr. Perry decided to sing a few numbers at an Eels show, which would be his first public performance in decades. He made this decision known to the band, Mr. Everett said, not via phone or email but by showing up to tour rehearsals one day carrying his own microphone. “He moves in mysterious ways,” Mr. Everett observed.

For mysterious Steve Perry reasons, Mr. Perry chose to make his long-awaited return to the stage at a 2014 Eels show at the Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul, Minn. During a surprise encore, he sang three songs, including one of his favorite Eels tunes, whose profane title is rendered on an edited album as “It’s a Monstertrucker.”

“I walked out with no anticipation and they knew me and they responded, and it was really a thrill,” Mr. Perry said. “I missed it so much. I couldn’t believe it’d been so long.”

“It’s a Monstertrucker” is a spare song about struggling to get through a lonely Sunday in someone’s absence. For Mr. Perry, it was not an out-of-nowhere choice.

In 2011, Ms. Jenkins directed one segment of “Five,” a Lifetime anthology film about women and breast cancer. Mr. Perry visited her one day in the cutting room while she was at work on a scene featuring real cancer patients as extras. A woman named Kellie Nash caught Mr. Perry’s eye. Instantly smitten, he asked Ms. Jenkins if she would introduce them by email.

“And she says ‘O.K., I’ll send the email,’ ” Mr. Perry said, “but there’s one thing I should tell you first. She was in remission, but it came back, and it’s in her bones and her lungs. She’s fighting for her life.”

“My head said, ‘I don’t know,’ ” Mr. Perry remembered, “but my heart said, ‘Send the email.’”

“That was extremely unlike Steve, as he is just not that guy,” Ms. Jenkins said. “I have never seen him hit on, or even show interest in anyone before. He was always so conservative about opening up to anyone.”

A few weeks later, Ms. Nash and Mr. Perry connected by phone and ended up talking for nearly five hours. Their friendship soon blossomed into romance. Mr. Perry described Ms. Nash as the greatest thing that ever happened to him.

“I was loved by a lot of people, but I didn’t really feel it as much as I did when Kellie said it,” he said. “Because she’s got better things to do than waste her time with those words.”

They were together for a year and a half. They made each other laugh and talked each other to sleep at night.

In the fall of 2012, Ms. Nash began experiencing headaches. An MRI revealed that the cancer had spread to her brain. One night not long afterward, Ms. Nash asked Mr. Perry to make her a promise.

“She said, ‘If something were to happen to me, promise me you won’t go back into isolation,’ ” Mr. Perry said, “because that would make this all for naught.”

At this point in the story, Mr. Perry asked for a moment and began to cry.

Ms. Nash died on Dec. 14, 2012, at 40. Two years later, Mr. Perry showed up to Eels rehearsal with his own microphone, ready to make good on a promise.

TIME HAS ADDED a husky edge to Mr. Perry’s angelic voice; on “Traces,” he hits some trembling high notes that bring to mind the otherworldly jazz countertenor “Little” Jimmy Scott. The tone suits the songs, which occasionally rock, but mostly feel close to their origins as solo demos Mr. Perry cut with only loops and click tracks backing him up.

The idea that the album might kick-start a comeback for Mr. Perry is one that its maker inevitably has to hem and haw about.

“I don’t even know if ‘coming back’ is a good word,” he said. “I’m in touch with the honest emotion, the love of the music I’ve just made. And all the neurosis that used to come with it, too. All the fears and joys. I had to put my arms around all of it. And walking back into it has been an experience, of all of the above.”

Find the Right Soundtrack for You

Trying to expand your musical horizons take a listen to something new..

Cass Elliot ’s death spawned a horrible myth. She deserves better.

Listen to the power and beauty of African guitar greats .

What happens next for Kendrick Lamar and Drake?

He sang “What a Fool Believes.” But Michael McDonald is in on the joke.

Hear 9 of the week’s most notable new songs on the Playlist .

- Bach on Skid Row Reunion

- Stones Cover Dylan in Vegas

- Rock's Best Four-Album Runs

- Songs Stones Rarely Play Live

- Snider: Induct Before They Die

- Pat Benatar Kicks Off 2024 Tour

25 Years Ago: Why Steve Perry Left Journey for Good

Journey lost singer Steve Perry for a second time on May 7, 1998. The first time, back in the '80s, Perry's exit had been voluntary – the result of recent solo success and growing indifference toward the band.

Left to their own devices at the time, former bandmates Neal Schon and Jonathan Cain formed Bad English with singer John Waite . (Perry had fired founding bassist Ross Valory and longtime drummer Steve Smith during the sessions for 1986's Raised on Radio .)

A decade mostly gone from bright arena spotlights paved the way for Journey's triumphant mid-'90s reunion. The resulting Top 20 album, 1996's Trial by Fire , swam against the current of the era's reigning alt-rock. Three charting singles, a Grammy nomination and plans for a successful comeback tour made it seem just like the good old days.

Unfortunately, those touring plans were derailed when Perry suffered a hiking accident and refused to undergo the hip surgery necessary to get him back onstage. This opened the door to renewed ill will and undoubtedly dredged up memories of the singer's late-'80s power grab for Journey's fate.

Instead of bending to Perry's whims this time, the other members of Journey banked on their fan base's renewed support and unquenchable hunger for tour dates by recruiting a Perry soundalike Steve Augeri in order to get on with business.

The band's decision appeared to have been vindicated by a successful decade-plus of touring and recording with Augeri and, later, Arnel Pineda. Perry, for his part, maintained a relatively low profile, seemingly satisfied belting out "Don't Stop Believin'" from the bleachers of his hometown San Francisco Giants' baseball stadium, and occasionally showing up as a guest singer. He's only put out one proper solo album since, 2018's Traces . (Perry released a different version of the same LP in 2020, followed by The Season , an album of Christmas standards, in 2021).

Journey joined the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2017 . Before the ceremony, Schon said he hoped Perry would perform with him again. Instead, Perry ended up taking part only in the acceptance speeches, simply commenting : "I am truly grateful that Journey is being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.”

The Best Song From Every Journey Album

See Neal Schon Among Rock’s Forgotten Supergroups

More From Ultimate Classic Rock

Journey's Neal Schon says he and Steve Perry are 'in a good place' before band's 50th anniversary

On the cusp of turning 50, the band that etched “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” and “Faithfully” into lighters-up lore is entering “a cleaned-up chapter of Journey.”

That’s according to Neal Schon, the band’s ace guitarist, lone original constant and de facto CEO.

Despite decades of fluctuating lineups and snarly lawsuits among band members , Journey endures.

On July 8, the band released “Freedom,” its first new album in 11 years that also presents the return of Randy Jackson (as in "American Idol") on bass. The 15-song collection is steeped with vintage-sounding ballads (“Still Believe in Love,” “Live to Love Again”) and soaring melodic rockers (“United We Stand,” “You Got the Best of Me”).

Journey – including longtime keyboardist Jonathan Cain, peppy singer Arnel Pineda , drummer Deen Castronovo and keyboardist Jason Derlatka, adding bassist Todd Jensen for live shows – will hit Resorts World Las Vegas this month for shows backed by a symphony orchestra before rolling through more arena dates this summer and in early 2023, the band’s official 50th year.

Need a break? Play the USA TODAY Daily Crossword Puzzle.

Journey in pop culture: Quarantined family perfectly re-creates 'Separate Ways' music video at home

Regular road warriors who consistently pack arenas and stadiums – their 27 shows this year grossed $28 million, according to Billboard Boxscore – Journey relies on a solid catalog of mega-hits and a devoted fan base that appreciates the familiarity.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Famers also received a boost from Netflix’s ’80s-centered “Stranger Things” when the show used “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)” in the trailer for the just-ended season, launching the song onto Billboard’s Rock Digital Songs chart. The affable Schon, 68, talked with USA TODAY about the band’s complicated legacy, his relationship with former frontman Steve Perry and plans for Journey's golden anniversary.

Santana recovers: Carlos Santana collapsed on stage from heat, dehydration

Question: Are you amazed at how the Journey train keeps rolling after almost 50 years?

Neal Schon: It’s quite an accomplishment and I’m very proud of what we’ve done and how we’ve gotten through emotional and personnel changes and survived. It’s pretty mind-boggling but also a lot of hard work.

Q: Does the title “Freedom” refer to anything specifically?

Schon: Our ex-manager Herbie Herbert wanted to call the (1986) “Raised on Radio” album “Freedom” because he always came up with these one-word titles. Steve (Perry) fought him on that and got his way, so we sat on it for many years. When we got through the lawsuit with the ex-bandmates, we made the new LLC Freedom (JN) and when we were tossing around album titles said, why not just call the whole thing “Freedom?" It's for the times right now.

Q: There’s been a bit of a revolving door in the rhythm section. Deen Castronovo is back for the live shows, but Narada Michael Walden played drums on the album, and Randy Jackson is back in the band, at least on record?

Schon: Deen is singing and playing his butt off. He’s such a musical sponge, this guy. He’s been like my little brother for close to three decades and is such a joy to work with. Randy, he’d been working with me diligently this whole time. He’s so many things beyond being an amazing musician and bass player.

Rock in the rain: Def Leppard, Motley Crue, Poison, Joan Jett combat weather during The Stadium Tour

Q: Will Randy play at any of the upcoming live shows or is Todd Jensen handling those duties?

Schon: Randy is still recovering from some surgery and he stays very busy and Todd fits like a glove. Having said that, I think with our 50th anniversary next year, there’s room for everybody to jump in if they want to participate. We did go through an ugly divorce with (Steve Smith and Ross Valory) with the court proceedings (in 2021, Schon and Cain settled a $10 million trademark lawsuit with the band’s former drummer and bassist). But definitely, if Steve Perry wanted to come on and sing a song, yes. If (original Journey singer) Gregg Rolie wanted to come sing a couple of songs, yes. Randy Jackson (can) come sit in on some of the material – he played on a lot of hits on “Raised on Radio.”

Q: Do you talk much with Steve Perry?

Schon: We are in contact. It’s not about him coming out with us, but we’re speaking on different levels. That’s a start, even if it’s all business. And I’m not having to go through his attorney! We’ve been texting and emailing. He’s a real private guy and he wants to keep it that way. We’re in a good place.

Q: Do you think, after 15 years, that people have accepted Arnel?

Schon: I was diligent in that I wanted to show the massive size of our audience, so I hired photogs to come out every show and shoot the audience and show the size of the crowd to make everybody see, what am I missing? From putting up the different photos every night and the reviews from the fans online, I saw very little of “This is not Journey, man.” I think we just shut everybody up.

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

Steve Perry of Journey: “Things happened to me as a child. There was nowhere to talk it out, so I sang it out instead”

Journey wrote “Don’t Stop Believin’”, the most downloaded song from the 20th century. When their lead singer quit, the band spent years trying to replace him. Finally out of hibernation, he tells his strange story.

By Kate Mossman

In the small hours of 14 June 2007, the Queen guitarist Brian May sat worrying at his computer. The American rock band Journey had fired another lead singer: 41-year-old Jeff Scott Soto had been erased from the group’s website – shed, Brian observed in his blog, like a used pair of boots.

It wasn’t that Brian didn’t sympathise with the pressures on a middle-aged rock band burdened with touring millions of dollars’ worth of hits when their original frontman was indisposed. He laid out Journey’s options. 1. Throw in the towel. 2. Find a look- and sound-alike. 3. Go out under a different name (“unrewarding”). 4. Find a new frontman who steals a bit of the limelight for himself.

Journey are responsible for “Don’t Stop Believin’”, the most-downloaded song written in the 20th century. They have had five lead singers to date. The single component they’ve spent three decades cyclically seeking to replace is the voice of their frontman, Steve Perry, who came and went, and came and went – then disappeared. Any Journey singer needs to sound exactly like Steve Perry, and that is not easy. He must have a high “tenor altino”, reaching F#2 to A5, with a tone somewhere between Sam Cooke and Aretha Franklin. The first time Perry quit the band was at the height of their fame, in 1987. He’d been nursing his dying mother, and considered retraining as a neurologist.

The second time he left, ten years later, was because the band were pressing him to have a hip operation, and he refused. The girlfriend of keyboard player Jonathan Cain dimly recalled a guy from another group she thought could hit notes as high as Perry could – so founder member Neal Schon tracked him down, and found him working as a maintenance manager for Gap, enjoying the security of his first pension plan.

The new singer, Steve Augeri, became known as “Steve Perry with a perm”. He took Journey’s hits to the arenas of middle America. As he did so, the real Steve Perry – who’d co-written those hits – rode a Harley Davidson through the San Joaquin Valley in California, back to where he was born.

The Saturday Read

Morning call.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

Perry has been a virtual recluse for 20 years. He sits before me in a Whitehall hotel, dissecting a chocolate muffin and carefully dabbing crumbs from his lap. He speaks in metaphorical language: he once said that leaving his band was like “re-entering the earth’s atmosphere with no heat tiles on my face”. The San Joaquin valley reached 110°F in the summer, with fields of almond trees, cotton and alfalfa. The alfalfa became a symbol of his escape. “It holds so much moisture that when you come to an area where there’s an alfalfa field on the left and right, the temperature drops 15 degrees. So I’m out on my motorcycle, and those were the days before ‘helmets’ [he makes quote marks in the air] and the wind is in my hair and all of a sudden, well, I cooled off.”

No one knew what Perry did next. There was a rumour he’d invested in a small bovine insemination business in California’s Central Valley, but it turned out to be a rogue edit on Wikipedia. In what some might call a terrible irony, the band he left behind enjoyed an unexpected, international renaissance without him, attracting a new generation of fans. In the 21st century, “Don’t Stop Believin’” was used on the soundtracks of the Oscar-winning 2003 film Monster , Scrubs, Family Guy, Glee and perhaps most memorably, in the final eerie moments of The Sopranos . It inspired long-read journalism on the magic of song craft, and it even formed the plot of the Broadway hair metal musical Rock of Ages .

Perry banked the cheques – but he missed the shows, because there was a new lead singer in the band who sounded just like him, and this time everyone was talking about it. Arnel Pineda was a Filipino fan who’d spent two years living homeless on the streets of Manila as a child – Neal Schon had found videos of him singing Journey songs on YouTube. Pineda has enjoyed the most successful stint in the job since the man he is imitating. Find a frontman who steals a bit of the limelight for himself, said Brian May, and “the sky’s the limit”.

When not riding his motorbike through the San Joaquin Valley, Perry attended the local fair, which came to his home town in June as it had done in his childhood. “I was drawn to the circus life, because they’d come into town – it was lights, Ferris wheels, it was moving, it was fantasy – and the next thing you know they’re gone,” he says. The circus was, he admits, not unlike a rock band.

“I saw Pinocchio as a child, and there was something evil about this special place where all the children could go. They’d go on the rides, but their ears would grow – and they turned into asses, actually, I guess.”

Rock bands are a ruthless business, but in Journey it’s hard to say who holds the power – the mutable frontman who forced the band in and out of hibernation for a decade, or the founder member who turned the frontman’s voice into a million-dollar franchise. Perry once claimed that he’d never felt part of the group. Schon replied: “How can you ‘not feel part’ of something you’re almost completely controlling?”

They only communicate through their lawyers now. But their songs play in every sports bar and mall in America, instantly and innocently evoking the pain and passion of ordinary human life.

“It’s like your boyfriend saying to you: drop a few pounds, get your nose fixed at the same time. Fuck off!”

Perry has watched his replacements come and go, but once, he was the replacement himself: in 1977, aged 28, having failed in several bands, he’d returned home to work mending coops on his uncle’s turkey ranch when he got the call from Neal Schon, asking him to join a jazz fusion band who couldn’t get a hit. Perry asked his mother, and she advised him to go for it. Schon tried him out by bringing him on the road and telling everyone he was the roadie’s Portuguese cousin. He sang a song at soundcheck when the official singer was away from the stage.

The clichés – “married to music”, “a band is like a family” – are well worn, but for the generation of men who became millionaire rock stars in the seventies and eighties (for it is men, and it is one generation) they are the only way to understand their motivations, not least because it is a language they invented themselves. Solo albums were referred to by Journey’s manager Herbie Herbert as cheating on your wife (both Schon and Perry cheated). Of the hip operation stand-off, Perry says: “When they told me they checked out some new singers, it’s like your boyfriend saying ‘Look, I really love you, but I need to know if we’re getting married or not because I’ve checked out some other chicks.’”

But it was more than that, wasn’t it? They were telling him they’d only take him back if he underwent major surgery.

“OK,” says Perry. “It’s like saying, ‘By the way, drop a few pounds, too. Get your nose fixed at the same time.’ FUCK OFF.” He then asks if we can talk about his new record, Traces , his first in 25 years.

When Perry was 16 years old, he heard “I Need You ” by the Beatles, released on the Help! album, and he felt they could have done better. Why had they done a kind of bossa nova he wondered, when it clearly cried out for R&B? He has reworked the song on his new album, which he wrote and produced on his own – “No one had their foot on my neck saying, ‘Are you done? Are you done?’ FUCK OFF.” he says.

When he was very young, Perry would “mumble hook lines” for potential songs, and it was in Journey that he was able to “apply everything I had ever dreamed of”. Their audience – suddenly full of girls – had a new and emotional relationship to the band via their commercial power ballads.

“You can’t solo for 18 bars,” he recalls telling Neal Schon – who was such a good guitarist that he’d been recruited by Carlos Santana aged 15, in the summer of 1969. “You can have about eight bars. And if it’s going to be eight bars, it has to be something beautiful.”

The first time the pair were put together to write, they finished Perry’s love letter to San Francisco, “Lights ” , in about ten minutes. He describes a song idea as a “sketch” – a framework of chord changes, a couple of melody ideas and a loop for rhythm. “But my problem is, I hear it completed already.”

Songs, he says, should be “like pancakes – stacked high with layers of feeling”. Modern writing is an “industrial assembly line because everyone’s on the grid. There’s 20 people writing these songs – they’re trying to maximise the individual assignments, like when they’re making a film, to increase the opportunity for a hit. But a song should be all about selling a feeling .”

Selling a feeling – is that the essence of power ballads?

“It’s the essence of music,” he says.

“Songs should be like pancakes, stacked high with layers of feeling”

“Don’t Stop Believin’” has had a lot of analysis in recent years, as interest has grown in the industry’s backroom magic. It is a power ballad with a strange minimalism, full of barely-there figures – “strangers waiting” and “streetlight people”. Unable to sleep in a Detroit hotel room, Perry had looked down to the street and noticed the way in which walkers would pop up suddenly in circles of light. The lyric’s “midnight train” was a musical madeleine, designed to take you back to Gladys Knight. The song was self-consciously cinematic, but states that life is a movie that never ends. Its thin but powerful sense of hope was so abstract, it applied to everyone – from the gambler in the lyric, rolling the dice “one last time”, to the real John Doe hearing “Don’t Stop Believin’” in a bar on a Friday night. It started with a refrain written by Jonathan Cain: what Cain heard as a chorus, Perry heard as a “pre-chorus” – suggesting that a “chorus of choruses” should be held off till the very end. It does not appear until three minutes and 20 seconds, delaying the climax. Perry gets a bit antsy discussing it.

“I don’t want to talk about the music because then you won’t listen, and it won’t be yours,” he says. “Your definition – what the song does to you, and the next person – are totally different. You hear music differently based on your life, your experience, what you are. When something resonates with a massive number of people, that is exactly what is happening.”

In 2007, he was approached by HBO for permission to use the track in the final seconds of The Sopranos . He refused to give it over without knowing what scene it would accompany, concerned that the entire Soprano family were going to “get whacked” to the song. For a few weeks, he was one of the only people in the world who knew how the series ended.

Another, equally effective modern-day licensing of the track was in Patty Jenkins’s Monster , when the serial killer Aileen Wuornos, played by Charlize Theron, meets her lover at a roller rink. A jukebox and a skating rink were just the kind of places you heard Journey every day, growing up, reinforcing the sense of their music as part of the wallpaper of American life. Perry, now 69, loved high school, “a magical time, when innocence is running your life.” Its memories are his songwriting metaphors: a concert venue, he says, rather strangely, is “the backseat of a car”.

“Everything I write comes back to high school. I know it sounds funny, but everything. It all comes from the emotions I grew into during my adolescence. Those moments are not to be tossed away.” He becomes emphatic. “If something means something to you, go back and get it and make it part of your life. And anyone who doesn’t understand how important that is, you tell them to FUCK OFF,” he advises, before breaking off to reveal he is desperate for the bathroom.

He was one of the only people in America who knew how The Sopranos ended

Perry was born to Portuguese parents in 1949. His father, Ray, was a singer – a baritone – who had tried to break into the business, and performed in the local theatres of his hometown. What kind of music did he sing?

“‘Pennies from Heaven,’” Perry replies.

His parents eloped because his mother’s father didn’t approve of a singing career. He tells their story as though music were some kind of hereditary condition or family curse, which in the case of Perry, you kind of feel it might be. His parents split when he was eight years old, and he, an only child, moved with his mother to his grandparents’ dairy farm – which might explain the rumours about his subsequent career. As with many rock stars, from Roger Waters to Lennon, the absent father was significant. I ask him why he became a singer.

“People don’t become performers because they don’t have needs,” he says. “Singing, though it can be very lovely, is essentially a primal scream. And I was screaming pretty loudly – and quite big.”

He was an invisible child, he says, but also a silenced one.

“There was a lot going on but nowhere to take it. Things happened to me as a child that I still can’t talk about – nothing to do with my parents, but things did happen. It happened to a lot of kids, as I find out.”

How old was he?

“About nine. But there was nowhere to take that stuff back then. One of my needs to perform was the need to get myself heard. Now, please, do understand, I’m not complaining – but there was nowhere to talk it out, so I got to sing it out instead.”

He spoke to a professional at the age of 63 about what had happened to him at nine. He was advised to do so by the woman he calls the love of his life, Kellie Nash, a psychology PhD candidate. But like everything else that has happened to Perry, theirs was not a conventional story.

During his mysterious, fallow years, Steve Perry seems to have investigated an alternative career in filmmaking. He was “shadowing” Monster director Patty Jenkins: “I love editing, I love directing. So with Patty I watched and learned a lot.” Jenkins was working on a TV film called Five for the Lifetime Network, exploring the impact of breast cancer. Being a methodical director, she surrounded her cast with real patients in remission. One of them – Nash – caught Perry’s eye. Jenkins then told him that Nash’s cancer had returned, was in her bones and lungs, and that she was fighting for her life. He went ahead anyway.

“I’d lost my mother,” he says. “I’d not reconnected with my father – which was another clean-up waiting to happen. I’d lost the grandparents who raised me. And I’d lost this career that I’d wanted so much, because I’d walked away from it.”

Was he so accustomed to losing things that a date with Nash didn’t scare him?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I justified it by telling myself, well, she’s a PhD psychologist, maybe I need another shrink?”

They had a year and a half together before Nash died in 2012. One night she said, “Promise me you won’t go back into isolation, for I feel that would make this all for naught.” He repeats the strange words, wide-eyed: all for naught . It was then that he decided to return to music.

“Life gets undone,” he says. “You try to come up with a plan, but it’s good for ten minutes a day. Some people have an ability to make belief systems work for a lifetime, but I think they’re hard to keep up.”

In 2014, he made world news when he turned up unannounced at a gig by the indie band Eels and performed their song “It’s a Motherfucker ” along with two of his own. He’d not sung live for 19 years but, explained the band’s Mark Everett, “For some reason only known to him, he feels like tonight in St Paul, Minnesota, it feels right.”

Perry, the once-invisible only child, still talks about Journey as a “nucleus” he could never break into. It is fair to say that the band didn’t want him at first – it was only under the orders of their manager that he was hired at all. They came to epitomise corporate rock. “There are still things I don’t like about it,” Neal Schon once said, “but this is the way I make my living.”

You suspect that, creatively, both men might have been better off without the band – the jazz rock boy-wonder, and the hit-writing soul mogul who really wanted to be on his own. But you take whatever route to fame is presented to you – and you follow the money: “I’d rather fail at being what I wanted to be,” Perry says, “than be successful being someone I didn’t.”

“Traces” by Steve Perry is released on 5 October through Hear Music

Content from our partners

Solving the power puzzle

The UK can be a leader in pushing the aerospace sector to a sustainable future

Harnessing Europe’s green power plant

The trauma ward

Why men shouldn’t control artificial intelligence

Germany and its discontents

This article appears in the 26 Sep 2018 issue of the New Statesman, The Tory Brexit crisis

The Real Reason Steve Perry Left Journey

For years, Journey singer Steve Perry used to wear a necklace of a gold musical eighth-note. In 2018, he explained to Rolling Stone it was a gift he received from his mom when he was 12 years old.

"She always believed in me. I wore it for years and years, but hung it up in May of 1998, just after the band and I legally split and I had a complete contractual release from all my obligations to the band and label."

Perry fronted Journey to its greatest commercial success in the '80s, catapulting the band to arena rock stardom through the likes of "Open Arms" and "Don't Stop Believin'." However , by 1987, even with the triumph of Raised by Radio tour, the band was greatly fractured and went on hiatus for nearly ten years.

As time heals all wounds, Perry reunited in the mid-90s with bandmates Jonathan Cain, Ross Valory, and Steve Smith. Now under the management of Irving Azoff, Journey released Trial by Fire. The Recording Industry Association of America certified the album platinum and the Recording Academy nominated one of its hit singles, "When You Love a Woman," for a Grammy.

Through pain, Steve Perry came back to music

Just before tour arrangements could be made, Perry collapsed while on a hike. He learned he needed hip surgery due to a degenerative bone condition. The band could not wait for Perry to heal, and so he was replaced by Steve Augeri and later Arnel Pineda .

For years, Perry's surgery explained his reason for officially leaving Journey. But in 2018, he made a revelation. Ahead of the release of his solo album Traces , Perry admitted his actual motive.

"The truth is, that I thought music had run its course in my heart," Perry said. "I had to be honest with myself, and in my heart, I knew I just wasn't feeling it anymore."

Perry , in soul and spirit, was tired. But like any true rockstar, he could not be away from the limelight too long. Traces allowed Perry to find music again. In a promise to his late girlfriend Kellie Nash, who died in 2012 from breast cancer, this was the moment he stopped isolating himself from the world.

"I found myself with not only just a broken heart but an open heart," Perry told Billboard . "And from that came rock and roll."

“It was a total triumph as a soft rock masterpiece and a deeply personal statement”: how Journey singer Steve Perry’s stepped away from his day job to deliver an AOR classic with Street Talk

Featuring the hit single Oh Sherrie, Steve Perry’s 1984 debut album Street Talk was an AOR landmark released in a year of AOR landmarks

![stephen perry journey Years ago, guitarist Mick Mars read a review of a gig by his band Mötley Crüe that stuck in his mind. It wasn’t what the journalist wrote about the show that stood out, it was what they wrote about him. “It said: ‘Mick Mars comes out to the front of the stage with his little troll body,’” he recalls. Other people might have been offended by that, but not the guitarist. “I thought: ‘Cool!’ It sounded creepy.” He laughs. “I’m the little goblin guy.” What the reviewer didn’t mention, or more likely didn’t know, was that in his twenties Mars had been diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), a genetic condition that over time fuses bones in the body together. “What I have now is bamboo spine,” he says, referring to his spine now effectively being one single bone – something borne out by his rigid posture and the occasional grimaces of discomfort during our chat. Yet despite his physical condition, he’s funny, wry and far more self-deprecating and egoless than any man who spent 42 years as member of Mötley Crüe should be. In many ways, Mars – born Robert Alan Deal in Indiana in 1951 – was an unlikely 80s-metal superstar. He was 29 and had already been around the block several times when his future bandmates responded to an ad he’d placed in local newspaper The Recycler in which he described himself as a “loud, rude and aggressive guitar player”. But it was Mars who helped get the band off the ground, via financial backing from a mysterious benefactor he refers to today only as “Alan”. And it was Mars, hunched and glowering, who brought a malevolent edge to the Crüe’s cartoon glam-metal pirate ride. He can’t talk about last year’s messy departure from the band, amid claims and counter-claims of backing-tape use and general inability to play. This is partly due to impending litigation, but also partly due to an unspoken sense that he’s still hurt by it. Instead his attention is focused on his imminent, and long-gestating debut solo album, The Other Side Of Mars. Co-written with former Winger keyboard player Paul Taylor, it’s a blast of melodic yet surprisingly convincing modern metal. Not that the man behind it is about to toot his own horn. “My number-one rule has always been never, ever believe your own hype,” he says. “That will wreck everything.” When did you decide to make a solo album? A long time ago. When we did the final tour [in 2016, which turned out not to be the final tour] was when I really started dedicating myself to coming up with a solo record. But it kind of got stopped. I didn’t like the direction it was going. I said: “No, it’s gotta be more than that.” It came together a little slow, but it was growing – crunchy songs, cinematic songs. It’s not progressive rock, but it’s progressing me. I’ll never be able to do what Steve Vai or any of those guys do. I’m just me. I play very simple stuff. Who made you want to pick up the guitar in the first place? Way, way, way back, when I was maybe three or four years old and we lived in Huntington, Indiana, we went to a fair. This guy named Skeeter Bond happened to be playing. He had this bright orange suit with sequins and stuff, he was wearing a big white Stetson, the old country-and-western thing. He got up there and did this stuff. I was, like: “Wow, that’s what I wanna do.” When was the first time you played guitar on stage? I had a school band that I did in junior high school, right around the seventh or eighth grade. There was this talent show thing, so I borrowed my cousin’s electric guitar and this teeny-tiny amp, and wrote a surf song called Conflict. Did you win the talent show? Heck no. They couldn’t even hear me. They were sitting five feet away, going [cups ear, mimes straining to listen]. The first band I played a gig with was The Jades. We copied a lot of British Invasion stuff. It was when bands still had ‘The’ in front of their name – The Beatles, The Stones. The Jades… What were the teenage Mick Mars’s ambitions? Were you fixated on becoming a successful musician? I went through surf music and British Invasion, and then I discovered blues and jazz. All the drummers in those days were into jazz, so I thought, okay, I‘ll listen to some jazz. I listened to Wes Montgomery, Miles Davis, all those people, just learning a lot of different ways of doing things and different kinds of music. And stumbling on King Crimson and Gentle Giant was pretty eye-opening for me. When I heard [King Crimson guitarist] Robert Fripp, and the way that he played, I went: “How can you do that and do it so fast?” It was so different. Everybody knows 21st Century Schizoid Man, but when you hear something like Cat Food [from 1970’s In The Wake Of Poseidon] you go, this is really off, but it’s so cool. Did you ever have your own progressive rock phase? I listened to it. I couldn’t grasp it. Well I could grasp it, but I couldn’t do it. I went to see Gentle Giant in California, and you’ve got them lined up across the stage, Kerry Minnear here and Gary Green there, and they’d go: ‘da-da-da-da-da-da’ and it would go straight across the stage – this guy plays three notes, this guy plays four notes, this guy plays one note. My jaw dropped. I was thinking: “How do you do that?” But I loved it because I couldn’t do it. What kind of guy were you then? I did my share of partying, but I’d stay out of trouble and play my guitar instead of being a clown. I was kind of a comedian, but I was never the dominant person in a roomful of people, never a ‘Look at me!’ kind of person. But I liked to laugh and have fun. Everybody does. Well, not everybody, there’s some miserable bastards out there. You had a son with your first girlfriend when you were nineteen. How hard was it to balance a young family with your rock’n’roll ambitions? We were both on a different page. I wanted to do this, she wanted me to work. We didn’t fight, we didn’t get in arguments. We decided we weren’t a match. So I went my way and she went her way. I made my child support payments. Before Mötley Crüe happened, you were the textbook struggling musician, playing in a string of bands in the seventies. How tough did things get? Pretty tough. No money, living on Bennies [Benzedrine, an amphetamine] on the street, sleeping on floors using my guitar case as a pillow. One band I was in, we all lived in the same apartment. I used to sleep behind my Marshalls, using them as a wall. I used to hang out with… I don’t want to say gangs, but biker-type people. I was doing a lot of partying with those guys. A lot of musicians must feel that void: “Is this the way it’s going for be? Am I going to do anything with my life?” What I learned is, if the chance to do something comes up, you gotta take it. You gotta keep at it. That’s what I was thinking all the time. Did you ever come close to quitting? Never. Not once. It was a lesson I needed to learn, I guess. I was being tested: you really want this this bad? Like the blues guys, you gotta pay your dues. What kept you going? Determination. I was obsessed: “I need to do this.” I wanted it so bad. No matter what the conditions were, I’m still doing this. I’d get afraid sometimes. I had a few jobs that were dangerous. I smashed my hand in one place. I was working at an industrial laundromat on the extractor, the ones that wring out the clothing in this six-hundred-pound tub. One day this tub came back and hit me in the left hand. It could have crushed my hand if it had hit a bit harder. It would have been the end of my career. I was like: “That’s it, I’m done,” and I walked out. And that night, at two o’clock in the morning, I played an after-hours show. You were playing on the same circuit as Van Halen in their early days. Did you know Eddie Van Halen back then? I’d known Edward since he was nineteen years old. When I first met them, they’d pretty much just got David [Lee Roth] in the band. I knew they were going to make it the first time I heard them. I was like, man, what a great band. We’d play in places like Gazzarri’s and the Golden West Ballroom. Me and the drummer from White Horse would go: “God, I hope Van Halen’s playing with us tonight, those guys kick ass.” Watching Edward grow into different areas was great. Is it true that you almost joined Sparks before Mötley Crüe got off the ground? What happened with that was that the guy from Sparks with the moustache [Ron Mael] called me from the ad I’d put in The Recycler. I told them straight up that it wasn’t the kind of music I played and they would be disappointed in me. They were more of a glam-rock band – David Bowie, T.Rex. I love that stuff, but I don’t play like that. What would Sparks with Mick Mars on guitar have sounded like? Oh, it would have been a train wreck [laughs]. Another person to answer your ad was Nikki Sixx. What did you make of him the first time you met him? I already had ‘Mötley Crüe’ in my mind as a band name. I’d had it since 1977, maybe 1976. So I went up there and auditioned them. I liked the way Nikki was playing – no amp, just slapping around and stuff. It was pretty cool. He said: “I’ve got a drummer too.” Ironically enough, Tommy Lee had been in a band called Suite 19, and we had a mutual friend named Freddy who gave me his number when I said I was gonna put an original band together. But I lost the number, so I never met him. And now here’s this guy who I was supposed to meet a long time ago, with Nikki. When we started playing it just went ‘Wooof!’ Instant. Kind of like the same story as Cream with Clapton and those guys. The story goes that you wanted to get rid of their original singer, O’Dean Peterson, because he was “a fucking hippie”. What was your problem with hippies? With O’Dean it was just that I didn’t feel he was right. Not that he sang horribly, he just had a more Roger Daltrey-type voice. I told Tommy and Nikki that I wasn’t sold on O’Dean, and they were stumbling around going: “Well, whadda we do?” And I go: “That skinny kid that I saw on stage last night in Rock Candy? Did you see those girls? They were going nuts over him. Sex sells.” And they went: “Oh yeah…” So that’s how we got Vince [Neil]. He fit well. When did Bob Deal become Mick Mars? It was before Mötley. I was calling myself Mick Mars in a cover band called Vendetta. ‘Bob Deal’ didn’t fit. I thought: ‘Mick Mars, that’s me.’ Did you become a different person when you renamed yourself Mick Mars? Nope. I only have one personality. Two names, one personality. I try to be pretty honest about who I am. I’m just a musician. I’m not a “look at me!” kind of person. Listen to me. You don’t have to look at me. You were twenty-nine when Mötley Crüe started. Did it feel like it was your last roll of the dice? No. If Mötley hadn’t panned out the way it did I would have moved on to something else. I’d still move on. I’d become stagnant if I didn’t. What was it like being in Mötley Crüe in the early days? There was electricity. We were feeding off each other like… I dunno, a rat with cheese. One of the first songs that came out when we were first getting together was Live Wire. There were a few that were pretty good, but when we did Live Wire we went: “Oh shit!” It went: ‘Kaboom!’ What do you remember about recording the first Mötley Crüe’s album, Too Fast For Love, in 1981? Working with [engineer and former Accept guitarist] Michael Wagener. I’d met Michael when I was still in my cover band Vendetta. Anyway, we recorded Too Fast For Love with this bonehead who didn’t know how to record anything, and he messed it up. I told the guys about Michael, and he fixed it all up. People loved that record. Michael lives up the street from me. He did the first Mötley Crüe album, and he did this new album. He’s done my first and last records. Were you hanging out on the Sunset Strip in the early days of Mötley Crüe? No. Whenever I would go up to the Strip and hear the bands, I don’t think they’d got away from what was going on. They all just wanted to be Van Halen or something. When we came out, it changed – the sound of the Sunset Strip, the look and the music and the rest of it. It’s like, ‘Oh, there is different music.’ That’s how it see, anyway. Did you hear a lot of bands suddenly sounding like Mötley Crüe? Yeah. Not exactly trying to copy us, but… I’m not saying that Mötley Crüe changed the world, but the sound was taking on an awareness. Mötley did well, and a lot of record companies were searching for that again. When we were going on an incline like this [draws sharp upwards line in the air] they were still like that [draws level line]. There was a lot of [jealously]. What was it like being in the eye of the hurricane? Did it screw with your head? No. It was cool to go: “I’m finally doing it.” And it was climbing and climbing. Seeing all these people going [makes cheering noise] is pretty overwhelming. We played the US Festival in 1983, there were 300,000-plus people there. Going out on that stage and playing was just… wow. The band toured with Ozzy in 1984. What do you remember about that? Not much, ha! I remember Ozzy being in my room. He was pretty high. He goes: “Mick, don’t answer the door if Sharon knocks.” And did she knock? Oh yes. There was no way I was answering it. Mötley Crüe took hedonism to the extreme in the eighties, but it seemed like you didn’t go as all-in as the other three. Is that accurate? Yeah, I did live in my own little world. I’d already done what they were doing. I was a few years ahead. Did I drink? [Laughs] Quite a bit. But then I went: “Hmmm… I don’t think this is for me.” Did you enjoy being in Mötley Crüe in the eighties? It was two-thirds fun. There’s always that part where it’s: “Get away from me, you’re bothering me.” What were the best bits? Playing all these places you never, ever thought you’d play in, things escalating until they seem almost bigger than life. You’re just some guy sitting there, and people are looking at you, going: “Wow, there he is!” I remember in Mexico City being a car with bulletproof glass and there were a few hundred people surrounding it. I don’t think they realised what it was like for us. What about the bits that weren’t so great? Well, sometimes it was younger guys being younger guys and an older being: “I just wanna sleep.” Pouring hairspray on my door and setting it on fire, that wasn’t fun. Though it’s kind of funny now. Tommy running down a corridor naked and all these old women popping their heads out the doors. Looking back it’s funny, but at the time it’s like: “Can you guys be a little bit more mellow?” You were diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis in your twenties, but you started experiencing symptoms even before that. How did it impact on your life? In my early teens my lower back would hurt. I thought it was from sunburn, crazy as that sounds. Later on it felt like somebody had come up and hit me on the back of the neck with a bat. And it really frigging hurt. I’d look around and there’d be nobody there. Gradually it did its thing. As time went on, everything stopped. My head stopped moving, walking stiff… Not too long ago I couldn’t look at any film of myself, I didn’t like the way I was looking. It’s so hideous. You see yourself on film and go: “Oh my god, no.” You can’t help that. Yeah, it’s my body beating me up. How did you cope with the AS? It was a little difficult. I’d drown some pain in alcohol, that sort of stuff. But I ended up getting hooked on opiates. I was so badly hooked on them. I would recommend never going down that street, ever. That was in the early 2000s. How did you end up in that place? We were touring, and I was in a lot of pain. You couldn’t imagine how much pain. If I stood up my whole back would just go into tension, what I call a Charlie horse [a cramp]. How you get it in your leg or on your thigh, my whole body, my whole back would get like that. A lot of times I would just stay in my bed, it was very hard to get up. This particular doctor was giving me Oxycontin, and I was taking way too many, of course. They gave me Vicodin, and this particular opiate called Lortab… I got so addicted to those. I just wanted the pain to stop. That stuff’s brutal. How did you clean up? I went to a bunch of doctors, cos we were going back on tour. The band and the manager was helping me, because I was helpless – I’d be a hundred pounds or something, I couldn’t drive a car, I’m an addict. They came in and helped me get clean cos they needed me. I go to the doctor’s and he says: “He needs a double hip replacement.” I ended up getting one hip replaced. But the time I spent in the hospital, they ended up giving me morphine for the pain. That helped me a lot with getting off that stuff. When I got out of the hospital they gave me something that acted in the same way that a Vicodin would do but wasn’t really addictive. I’d have one, then a half, then a quarter. It took me four months to totally get off of that. It was difficult. Don’t go there. How do you manage it now? Advil. Only four a day. I’m not a youngster any more. You gave forty years of your life to Mötley Crüe. Is there part of you that misses it? It’s a difficult one to answer. I got a little too beat up touring… I wanted to do my solo thing. Do I miss touring? It’s one of those kinds of things that there’s a time to step back, and it was my time to step back. Despite everything that’s happened with Mötley Crüe recently, are you proud of what you achieved with the band? Absolutely. My whole studio is covered with all our albums – quadruple-platinum, hundred-million albums, all our stuff from the US Festival and the Moscow Peace Festival. Do you wish you’d been given more respect as a guitarist? I wouldn’t say so. It’s like this: do you like Coke, or Pepsi? Some people really dig me, some people don’t. It’s all good to me. Do you think you’ll ever play live again? I would say if I don’t get too old first I could do a one-off show easily. I could do a residency easily enough, you just go downstairs and play. If I needed it I could sit on a stool or chair, then go back to my room and relax and watch a monster movie and go to sleep. But the intense travelling, I just can’t do that any more. It’s too much. I guess it was a choice. You can be a guitar player with AS, or a worker with no AS. Do you wish you could go back and swap it? I got the deal I got. There was no choice. The Other Side Of Mars is released on February 23 and will be reviewed next issue.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/2crK9DuhqzV9rWQjCMNNrT-320-80.jpg)

It was a golden year for melodic rock. In January 1984 came the debut album from a young band out of New Jersey named Bon Jovi , and in the months that followed, so many other great albums arrived. Survivor , with new singer Jimi Jamison, hit a new peak with Vital Signs . Bryan Adams released Reckless , the album that would make him a superstar. Pat Benatar’s Tropico was a thing of beauty.

There were also fine albums that somehow flew under the radar or slipped through the cracks, but which later become cult classics – Dakota’s Runaway , and self-titled debuts from Giuffria, White Sister and Boston spin-off Orion The Hunter.

At the other end of the spectrum there were huge hit singles for Night Ranger with Sister Christian and John Waite with Missing You . And at the end of the year came the release of two monumental power ballads, both of which would top the US chart: Foreigner’s I Want To Know What Love Is and REO Speedwagon’s Can’t Fight This Feeling .

For AOR connoisseurs it was the best of times. There was, however, one great record from 1984 that had a sting in the tail: Journey singer Steve Perry’s solo album Street Talk .

Perry wasn’t the only member of Journey who was moonlighting that year; guitarist Neal Schon hooked up with his buddy Sammy Hagar in the brief-lived supergroup HSAS, while drummer Steve Smith busied himself with his jazz project Vital Information. But Perry’s record would have a huge impact on Journey’s career.

Street Talk was heavily influenced by the soul and R&B he had loved since he was a teenager, and after the album hit big – selling two million copies in the US alone – Perry steered Journey in a similar direction on the band’s subsequent album, Raised On Radio . As a result, Schon ended up sidelined in what had always been his band, and the definitive Journey line-up that made the classic albums Escape and Frontiers fractured with the exits of Smith and bassist Ross Valory.

But while Street Talk might have been a problem for Journey, it was a total triumph for the singer – as both a soft-rock masterpiece and a deeply personal statement. The album was written and recorded with a cast of famous and not-so-famous musicians, including guitarist Waddy Wachtel and drummer Craig Krampf, the latter from Perry’s pre-Journey band Alien Project.

Classic Rock Newsletter

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

At the absolute peak of his powers, for Street Talk Steve Perry put everything he had into a series of perfectly crafted songs: Oh Sherrie , written for his then partner Sherrie Swafford, became a massive hit single; Captured By The Moment , a beautiful eulogy for lost heroes such as Martin Luther King and soul legend singer Sam Cooke; Strung Out , a heartbreak song that rounded off the record in a hard-rocking fashion that Neal Schon might have found a little ironic.

In a year so full of amazing music, Steve Perry delivered one of the greatest AOR albums of all time.

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q . He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar . He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”

AC/DC share first photo of new 2024 lineup featuring drummer Matt Laug and bassist Chris Chaney

“You can just see the decline”: The time that Creed bassist Brian Marshall went to war with Pearl Jam

"Ten Years After are still partying like it's 1967 even though it's 1971": Ten Years After discover a glitch in the blues rock matrix on A Space In Time

Most Popular

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

'I believed love could cure cancer': how grief sent Steve Perry on a new Journey

The man behind Don’t Stop Believin’ had abandoned music – until he fell in love with a dying woman, who made him promise to return to performing

S teve Perry is explaining all the ways in which Journey’s Don’t Stop Believin’ can hook a listener. “The quarters on the piano – that intro’s a hook.” He bursts into song, his alto/countertenor still distinctive at 69 years old, and he is so powerful that it is offputting: “‘Just a smalltown girl’ is a hook. ‘Strangers waiting’ is a hook. ‘Up and down the boulevard’ – hook. [His bandmate] Jon Cain thought the ‘streetlights, people’ section was a chorus. Then I turned round and said: ‘Now we need to write the chorus of choruses.’ No one knew what that meant; nor did I. But I knew we had to take it somewhere bigger and never go back to the song again. Because it had done all these things I had mentioned and, in my opinion, it needed to go one more place.”

Don’t Stop Believin’, a monster hit in the US on its release in 1981 and since championed on the TV show Glee, has been so unavoidable in the past few years that you wouldn’t guess Perry has largely been silent for 20 years, since he left Journey once and for all. There were a couple of low-key appearances on other people’s records, the very occasional interview (not a favoured pastime even when he was with Journey) and that was it. But the ubiquity of Don’t Stop Believin’ made it seem as if he was ever-present.

“I would say I was completely burned out, with touring, recording, writing music incessantly,” he says. “I was having an emotional PTSD breakdown in music. I’m not whining, I’m just saying there was a lack of connection to the passion for music I had discovered when I was seven years old. I walked away with no ideas of returning. Then, years later, things started to change.”

Quite how things started to change, leading Perry to record his first album since Journey’s Trial By Fire in 1996, is one of the oddest, saddest stories you will hear a rock star tell.

Perry had never married. “I was too scared of it after what I watched my parents go through,” he says. “And I was around a band that went through several divorces in the course of our success. I saw them lose half of everything multiple times.” He had serious relationships – his 1984 solo hit Oh Sherrie was inspired by his then girlfriend Sherrie Swafford – but he had never been completely swept away by love.

Then, in 2011, his friend Patty Jenkins, the director of Wonder Woman , showed him a cut of her TV film about breast cancer . Perry’s eye was caught by one of the cancer survivors who appeared briefly in the film. The woman was Kellie Nash, a psychologist who had undergone treatment. “I said to Patty: ‘Do you have her email?’ She said: ‘Why?’ Because she knew me. I’m not like that. I said: ‘I don’t know, but there’s something about her smile that’s killing me right now. Would you send her an email saying that your friend Steve would love to take her out to lunch?’ She said: ‘OK, I will, but there’s one thing I should tell you first. She was in remission, but it came back, and it’s in her bones and it’s in her lungs and she’s fighting for her life.’ So I thought: I’m going to forget the whole idea. I thought: you walked away from a career, your mother has passed away, your grandmother and grandfather have gone, your dad’s barely hanging on … Maybe you should just forget the whole thing. But then I thought: bullshit.”

He told Patty to send the email, the pair met for dinner and they ended up together for a year and a half.

Perry entered the relationship knowing that doctors said Nash would die, sooner rather than later. What did he hope to gain from their brief time together? “You want to know the truth? I’ve not said this to anybody yet: I believed our love would cure her cancer. I really did. We sat in our tiny apartment in New York – a very expensive small box – and she said: ‘This might take me, but it’ll never be able to touch our love.’ I never thought about such a truth like that. Not just talking about it, but physically feeling it and emotionally seeing it was new to me.”

Before she died, Nash extracted a commitment from Perry. “She said: ‘Promise me you won’t go back into isolation, because I fear it would make this all for naught.’ I said: ‘OK, I promise.’ I lay in bed thinking about what I’d just promised. She was looking at the arc of her whole life and the possibility that she may not make it had to have some goddamn meaning. She was looking for purpose in all this. I grieved for two years – it was a whole new level of broken heart. It was completely fucking broken. I worked through that and, the next thing I knew, I started writing music.”

Eighteen months after Nash’s death, Perry returned to live performance. He had been a fan of the band Eels , visiting their rehearsals , going to their gigs and joining in with Mark “E” Everett’s weekly croquet game. Finally, Everett asked if Perry might fancy joining Eels on stage. “So, we worked up It’s a Motherfucker – I love singing that – and a couple of Journey songs. And I flew out to St Paul [in Minnesota] when they were at the Fitzgerald theatre in May 2014 and jumped on stage with them . It was really a thrill. I forgot what being in front of people felt like until I went out with the Eels. Looking into the eyes of people and singing for them felt good again.”

Perry had already started writing again before Nash died, but now he started working in earnest: building a studio at his home, fetching co-writers and musicians. “I wasn’t signed to anybody. I had no management. I funded the record entirely out of my own pocket. I built my own studio. I had to have the freedom to suck – nobody was going to put their foot on the back of my neck saying: ‘Is it done yet?’” The result is Traces , an album of slick, album-oriented rock that sounds as if Perry had not taken 20 years off and for which – keeping his promise to Nash – he is putting himself out into the world, doing interviews in numbers he never did with Journey, when he was zealous about guarding his privacy.

So, how does Perry feel about his life now – not only about losing the woman he loved, but also about forcing himself to talk about it to everyone who turns up with a voice recorder? “This has been amazing. Doing this has been cathartic for me. I guess it’s time to talk, it’s time to be open. It’s time to be honest about my feelings. I think I’ve been enjoying it, because it’s been a long time coming.”

Traces is out now on Fantasy

- Pop and rock

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Steve Perry has rerecorded a Journey deep cut with the sons of Steve Lukather and Phil Collins