What's On in Paris

Performances.

- Christmas in Paris

- The Eiffel Tower

Monuments in Paris

Historic churches, history museums.

- The Louvre Museum

- Musée d'Orsay

The Top Paris Museums

Artist museums, more paris museums.

Eiffel Tower Skip-the-Line

The 6 essential day trips, 10 more iconic day tours, what to do in paris, seine river cruises, night in the city of light, paris city tours, walking tours, your own private paris.

- Romantic Dinner Cruises

The Top Left Bank Hotels

The best hotels in paris, boutique & romantic, top hotels near…, preferred 5-star hotels, the palaces of paris, affordable hotels.

Le Marais Food & Wine Tour

Food & wine activities, the foods of paris, memorable paris dining, best paris restaurants, paris restaurant guide.

- Bistros & Brasseries

Top-Rated Restaurants

- Visit the Champagne Region

Paris Attractions

You ask, we answer, visiting burgundy, paris miscellanea, top ten lists, unusual paris sights, paris gardens & parks, the paris explorer.

- What's On When You're Here

Airports & Transfers

Getting around paris, paris travel guide, paris essentials, train travel, paris arrondissements, the paris commune of 1871 – history of a revolution in eight sites.

You say you want a revolution? How about this for a set of circumstances — Your country starts and immediately loses one of the most useless and foolish wars in its history. Your leader and president-for-life abdicates and flees to England. Your city is bombarded, besieged by enemy troops, and starved into submission. Any remnants of a national government flees the capital, leaving its population to fend for themselves.

Discover What's On When You're Here...

Discover what's on when you're here, the franco-russian war.

The Franco-Russian War of 1870 resulted in the dissolution of the empire of Napoleon III and left Paris in a shambolic state. In the resulting political power vacuum a spontaneous radical, socialist, and anti-religious republic was established in the city called the Paris Commune. At odds with the national government (now located in the former royal enclave of Versailles) the short-lived (March 18 to May 28, 1871) Commune resulted in further death and destruction. Let's explore this brief, turbulent chapter in the life of the city by visiting some of the sites of the Paris Commune.

Experience the Splendor Of Versailles

1. montmartre & the cannons affair.

Following the abdication of Napoleon III, Adolphe Thiers became the head of the national government. He was disliked in Paris after he unilaterally surrendered to the Prussians, ceded the French regions of Alsace and Lorraine, and allowed the Prussian army to parade down the Champs-Elysées. The dislike was mutual, and the conservative Thiers was eager to suppress what he viewed as revolutionary elements in Paris.

During the Prussian siege Paris had been defended, not by the French army, but by La Garde Nationale (the National Guard, commonly called the fédéré) , troops who had stuck by Parisians during the Prussian siege. Thiers struck a blow to the city by abolishing the fédéré , ending the pay of its members, thereby depriving many Parisian families of income.

The last straw, though, was the "cannons affair". 227 cannons were seized from the National Guard just before the parade of the Prussians and removed to the hills of Montmartre and Belleville. On the night of March 27, 4,000 French army troops stormed Montmartre to retrieve these guns, but found themselves surrounded by a crowd of Communards and Fédérés . (These two terms were to become interchangeable. The French army troops were referred to as Versaillais .)

Romantic Dinner Cruises In Paris

Two Versaillais generals were seized and shot (despite the intervention of future World War I Prime Minster Georges Clemenceau, then the mayor of the 18th Arrondissement) and across Paris barricades were erected by Communards. Imagine, if you will, Place Blanche and Rue Lepic blocked by barricades. (Actually, you don't have to image it; there's an illustration just above.) Thiers and his government quit Paris for Versailles, the very symbol of royal power.

2. The Vendôme Column

After the departure of the Versaillais , the Paris Communards organized elections and a new city council begin sitting on March 28. It was a very diverse group with mostly republican and socialist tendencies that included thirty-three artisans, twenty-four intellectuals, six workers, and one painter — Gustave Courbet.

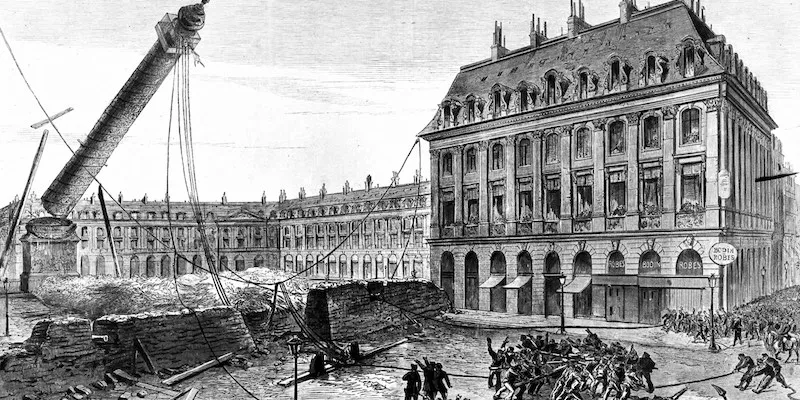

Certain elements of the Fédérés embarked on a mission to eliminate what they considered to be symbols of imperialism and ruling power. One of these was the column in the center of Place Vendôme. Napoleon had created this monument in 1810 to commemorate his victory in the battle of Austerlitz. Its bronze spiral frieze was made from 1,250 canons captured during the battle. And, of course, the perfect way to cap off the monument was with a statue of Bonaparte himself.

In the middle of May 1871 a group of Communards equipped with ropes, pulleys, and scaffolding pulled down the 44-meter-high column, sending the statue of Bonaparte crashing to the pavement of Place Vendôme. Courbet may or may not have been involved in the demolition, but post-Commune he was the one who was blamed. ( Photo portrait of Courbet .) Courbet was later convicted of the destruction and ordered to pay the cost of rebuilding the column. Instead, he fled to Switzerland, where he died a few years later.

Our Most Popular Day Trips from Paris

3. hotel de ville.

Within days of the felling of the Vendôme Column the national government brought the full force of its army down on the city. Versaillais troops started bombarding and invading Paris; the levels of violence and destruction mounted. May 21, 1871 saw the beginning of La Semaine Sanglante (Bloody Week), bringing further death and devastation to the Ville Formerly Known As The City Of Light.

On May 24 the Hotel de Ville was among a passel of buildings torched by the mobs. The fire here and at the Palais de Justice destroyed not just buildings, but centuries of civic records.

Skip the Lines at the Eiffel Tower

4. palais des tuileries.

Catherine de' Medici (1519-1589), queen of Henry II and mother to kings Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III, moved out of the Louvre following her husband's death and began building a palace and gardens next door. The wide, narrow palais faced the Louvre and backed onto the then-new Jardin des Tuileries . Eventually, the palace would be the final residence of the doomed Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette as well as the residence of France's two emperors Napoleon and Napoleon III.

As a sort of royal red flag the Tuileries became a symbol of monarchical oppression, a concept that didn't sit well with the revolutionary Communards. So, it's no surprise that it, too, was torched in May of 1871. The fire lasted forty-eight hours and thoroughly gutted the palace. All that remained was the ceremonial gateway to the palace, the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel.

The Hotel de Ville would be rebuilt to its original splendor, but the Palais des Tuileries was left in ruins until it was razed in 1883. Some of the stone pieces from its courtyard can be seen today in the gardens at Trocadero .

Find Hotel Deals for Your Dates in France

5. palais d'orsay.

Before it was a museum it was a train station. And before it was a train station there was a imposing palais on the site. Like so much about Paris, this project on Quai d'Orsay was started by Napoleon. And, like so many projects, it wasn't completed by him. But, the grand government administrative building known as Palais d'Orsay was finished in about 1840, when the French Conseil d'État (Council of State) moved its offices here. The building was celebrated for frescoes on the main staircase painted by artist Théodore Chassériau, fragments of which are today preserved at the Louvre.

As a government office building Palais d'Orsay became a target for the arsonist Commune mob and it, too, was gutted by fire during Bloody Week. Fortunately, when Theirs moved the government to Versailles the Conseil d'État had gone with him, along with all the documents. The shell of the building sat vacant for more than thirty years until it was chosen as the site for a new gare to serve the visitors who would be arriving for the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle .

6. Rue Saint-Jacques

As the Versaillais troops advanced through Paris the Communards erected more and more barricades in the streets. And, when the national army captured the revolutionaries, improvised war trials were held, where thousands of Parisians were judged, condemned, and immediately shot. There were dozens of sites where barricades were erected and dozens of sites of mass execution. On the Left Bank, for one example, there were sites along Rue Saint-Jacques.

Rue Saint-Jacques is one of the oldest (and longest) streets in Paris. It was the Roman's cardo maximus , that is, the primary road through the settlement and the basis for the grid layout of the rest of the city. On May 24, 1871 a number of Communards were executed in the apse of Église Saint-Sevérin at 10 Rue Saint-Jacques. Further up the hill, at 50 Rue Saint-Jacques (today the entrance to one of the universities of the Sorbonne) barricades were created in an attempt to protect the Pantheon from the Versaillais . (That attempt was unsuccessful and there were executions on the very steps of the Pantheon.) Further along, at number 195 (Institut Océanographique de Paris) troops were able to bypass another barricade and kill all of its defenders.

On Rue d'Haxo in the 20th Arrondissement there was a sort of retaliatory episode where, on May 26, fifty-two people, including eleven priests, were shot by the Communards. And so it went for those seven terrible days.

Two Of The Most Popular Paris Experiences

The most popular paris experience, 7. père lachaise cemetery.

The human toll of La Semaine Sanglante was horrendous. Estimates vary, even among historians of the period, but it seems that between 3,000 and 5,000 Fédéré troops died in the fighting and around 20,000 Communards were massacred.

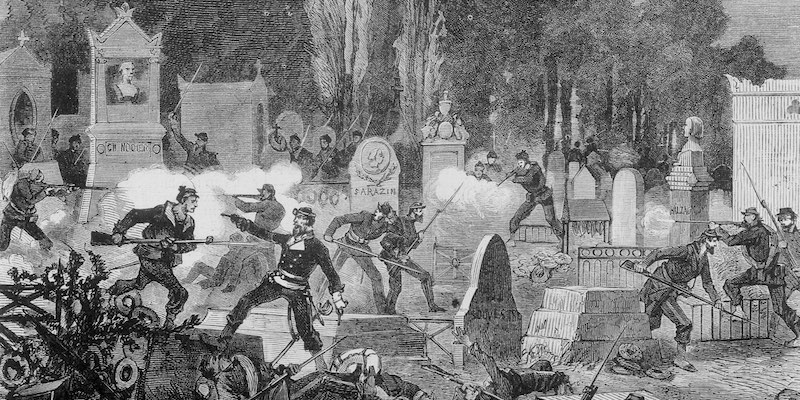

Our last virtual visit to these bloody sites is in the 20th Arrondissement, at Père Lachaise Cemetery. On May 27, when the end of the uprising was near, a battle, fought among the gravestones, between Versaillais troops and Communards armed mainly with knives, resulted in 147 Fédérés shot with their backs to the wall that now bears their name, Mur des Fédérés .

8. Basilique du Sacré Coeur

It's interesting, ironic, and still controversial that the very place where the Paris Commune started, on the hill of Montmartre, would become the site of the city's most visible church. In October 1872, just one year after the Paris Commune was savagely put down, the plot of land on which the battle of the cannons was fought was chosen as the site of a new church to "expiate the crimes of the Commune". The National Assembly passed a law allowing the Archbishop of Paris to acquire the land, if necessary by expropriation, a power normally granted only to public authorities.

The church, which would be the large white domes of Sacré Coeur that any current visitor to Paris can't avoid seeing, was begun in 1875 but not completed until 1923. Even today some consider the basilica to be a symbol of the crushing of the Communard revolution in the very heart of the district where the Paris Commune was born.

Top-Rated Paris Museum Tours

Epilogue. the belle époque.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the disastrous Franco-Prussian War and the devastation of The Commune is that, once over, Paris seemed to simply pick up where it had left off. In the world of painting, Impressionism really hit its stride in the 1870s. A new era of art and design began, one that came to be called the Belle Époque. Palais Garnier , the stunning opera house that had begun in 1861 as part of Baron Haussmann's renovation of Paris, a prime example of Belle Époque sensibility, was completed a few years later in 1875

Other notable works of the Belle Époque include Gare de Lyon and its restaurant Le Train Bleu , Pont Alexandre III, and the grands magasins Printemps & Galeries Lafayette.

Paris Planning Guides

Copyright © 2010-2023 Voconces Culinary Ltd, all rights reserved. Original photos © Mark Craft, all rights reserved.

- • May 2024 in Paris…

- • June 2024 in Paris…

- • July 2024 in Paris…

- • August 2024 in Paris…

- • September 2024 in Paris…

- • October 2024 in Paris…

- Paris Activities Month by Month

- Paris Olympics 2024

- Paris Events Calendar

- Museum Exhibitions Calendar

- Paris Ballet Calendar

- Paris Opera Calendar

- Christmas Day in Paris

- New Years Eve

- New Years Day in Paris

- Easter in Paris

- Valentines Day in Paris

- Bastille Day Celebrations

- Skip-the-Lines at the Eiffel Tower

- Visiting The Eiffel Tower

- Eiffel Tower Information

- See all…

- The Arc de Triomphe

- The Panthéon

- The Bastille

- Notre Dame Cathedral

- La Sainte Chapelle

- Sacre-Coeur Paris

- Chateau de Versailles

- Palais Garnier Opera House

- Hotel de Ville – The City Hall

- Get the Most from Your Visit

- Masterpieces of the Louvre

- Paintings of the Louvre

- Top 10 Van Goghs at d'Orsay

- Musée de l'Orangerie

- Centre Pompidou

- Musée Picasso

- Rodin Museum Paris

- Cluny Museum Paris

- Arts et Metiers

- Guimet Asian Arts Museum

- Galliera Fashion Museum

- Versailles the VIP Way

- Versailles History & Highlights

- D-Day Landing Beaches

- Monet's Gardens at Giverny

- Mont Saint-Michel

- Monet + Van Gogh

- VIP Private Day Trips

- 10 Ways to Skip the Lines

- 9 Most Romantic Things to Do

- 5 Top Activities In The Marais

- Lunch & Brunch Cruises

- Cruises with Extras!

- The 6 Best Evenings In Paris

- Moulin Rouge

- Paris at Night

- Hop-on, Open-Top Buses

- The 6 Best City Tours

- Private Tours of Paris

- Champagne & Shows

- Top 10 Walking Tours

- Mysterious Walking Tours

- Shangri-La Paris

- Hotel George V Paris

- The Royal Monceau

- Le Cinq Codet

- Peninsula Hotel Paris

- Hotel Le Burgundy

- See all …

- 10 Best 4-Star Hotels

- Top 3-Star Hotels

- Best Airport Hotels

- Latin Quarter Hotels

- Left Bank Hotels

- Romantic Paris Hotels

- Best 2-Star Hotels in Paris

- Ibis Hotels

- Les Hotels de Paris

- Best Western Hotels

- Saint-Germain-des-Prés

- Top 10 Food Experiences

- Paris Wine Tastings

- Chocolate Tours

- 10 Best Cheese Shops

- The Best Baguette in Paris

- Food Markets of Paris

- Le Jules Verne

- Jacques Faussat

- Restaurant Le Gabriel

- How to Choose a Restaurant

- The Best Paris Bars

- In the Marais

- On the Left Bank

- Historic Brasseries of Paris

- Michelin 3-Star Restaurants

- 6 Michelin-Star Restaurants

- See All…

- Best Paris Terraces

- Seine Dinner Cruise

- The Top 8 Tourist Attractions

- 5 Paris Itineraries

- Gardens & Parks

- Paris Hotels for Christmas?

- Best Restaurants in the 8th?

- Best Way To Visit Versailles?

- VIP Burgundy Wine Tour

- Burgundy Accommodations

- Napoleon's Paris

- Hemingway's Paris

- Medieval Paris

- 10 Tips For Visiting Paris

- 7 Vestiges of Roman Paris

- 13 Hidden Places In Paris

- Hidden Landmarks

- The Catacombs

- Pere Lachaise Cemetery

- Jardin des Tuileries

- Jardin des Plantes

- Palais Royal

- Rue des Barres in the Marais

- Waterfalls of Paris

- Arcades of Paris

- Airport Transfers

- Paris Airports

- Airport Taxis

- Train Travel From Paris

- Eurostar: London & Paris

- Paris Train Stations

- The Latin Quarter

- Saint-Germain-des-Pres

- Essential Facts for Visitors

- Taxes, Tipping & Etiquette

- What to Wear in Paris

- Maps of Paris

- The Paris Metro

- Paris Metro Tickets

- Paris Taxis

- Seine River Dinner Cruises

- Visiting Versailles

- Essential Day Trips

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Paris Commune of 1871

By: History.com Editors

Published: November 17, 2022

The Paris Commune of 1871 was a short-lived revolutionary government established in the city of Paris after France’s crushing defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Despite lasting only two months, the Paris Commune introduced many concepts now considered commonplace in modern democracies, including women’s rights, worker’s rights and the separation of church and state. The uprising came to an end when troops from the Third Republic reclaimed power following a vicious week of fighting that left at least 10,000 Parisians dead and much of the city destroyed.

Roots of the Paris Commune

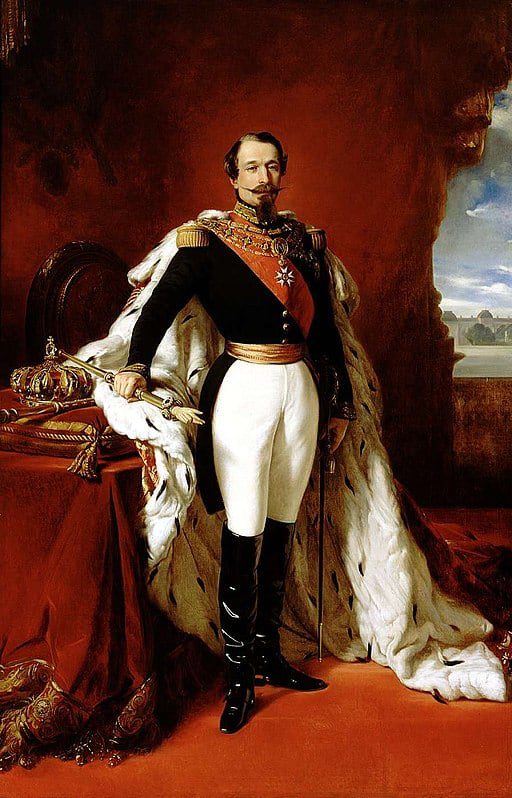

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Prince Otto von Bismarck sought to unify all German states under the control of his native state, Prussia. But the Second Empire of France, ruled by Napoleon III (the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte ), declared war against Prussia to resist their ambitions.

In the months of war that followed, France’s army was consistently routed by the larger and better-prepared German troops. At the Battle of Sedan in September 1870, Napoleon III was captured by German troops, and his wife, Empress Eugénie, fled Paris. Soon, Paris was under a lengthy siege lasting into the winter months, and the French minister of war was forced to escape the surrounded city in a hot-air balloon.

After the French admitted defeat and Napoleon’s Second Empire collapsed, the final 1871 armistice between Germany and France gave billions of francs to Germany, plus the formerly French territories of Alsace and Lorraine, in a humiliating defeat for France.

Resentment over the punitive terms of the armistice roiled France, nowhere more than in Paris, whose starving citizens suffered so miserably during the wintry German siege that the animals in the Paris zoo were eaten, and some Parisians were reduced to eating cats, dogs and rats to survive.

The Third Republic

Following the collapse of France’s Second Empire, the remaining government officials established the Third Republic, formed a new legislative National Assembly and elected Adolphe Thiers, age 74, as leader. Because the government was more conservative than the citizens of Paris would tolerate, and because Paris was still dealing with the effects of the Prussian siege, the former royal palace at Versailles —about 12 miles west of Paris—was chosen as the government’s headquarters.

None of these new developments sat well with Parisians: The Third Republic had many hallmarks of the former monarchy and was supported by the Catholic Church, military leaders and France’s more-conservative rural population. Many Parisians feared the Versailles-based government—which had initiated the disastrous war with Prussia—would be a republic in name only and would soon reestablish the monarchy.

While Paris—at the time, a city of some 2 million residents—was under siege, the city was defended not by the French army, but the local National Guard, often called the f é d é r é , which had almost 400,000 members. When Thiers abolished the f é d é r é , depriving many families of their main source of income, it sparked a furious rebellion that spread throughout the now-radicalized National Guard and across Paris.

The Cannons of Montmartre

By the end of the Franco-Prussian War, Paris had hundreds of bronze cannons scattered across the city. The National Guard, now firmly opposed to the Third Republic and their military leaders ensconced at Versailles, moved many of the cannons to the working-class neighborhoods of Montmartre, Belleville and Buttes-Chaumont and out of the reach of government troops from Versailles (the Versaillais ).

On the morning of March 18, 1871, Versaillais troops arrived at Montmartre to seize the cannons, but they were confronted by National Guardsmen and angry citizens intent on keeping the cannons. As the day continued and tensions ran high, many Versaillais soldiers switched sides and refused to fire on the crowds of citizens and guardsmen in defiance of orders from their leader, General Claude Lecomte.

By the afternoon, Lecomte and another Versaillais general, Jacques Clément-Thomas, had been captured by Versaillais deserters and the National Guard—both generals were soon beaten and shot to death. In response, Thiers ordered all remaining government officials and loyal army troops to immediately decamp to Versailles, where a counterattack was to be planned.

Paris Commune Established

Now that the government of the Third Republic had departed the city, the National Guard and sympathetic citizens of Paris wasted no time in setting up a local government and preparing for an expected battle against troops from Versailles. Within days, the city was militarized, with crude barricades made of cobblestones and other debris blocking roads.

City leaders also held elections to establish a new government for Paris, named after the Paris Commune that governed Paris for six years during the French Revolution . Though the newly elected Paris Commune began working on March 28 in the Hôtel de Ville , the Communards were riddled with internal divisions, and vociferous differences of opinion were commonplace.

Nonetheless, the Paris Commune of 1871 succeeded in establishing many basic rights that are now considered commonplace in modern democracies, such as child labor laws, laborers’ rights , the separation of church and state , no religious teaching in public schools and pensions to the families of National Guardsmen killed in service.

But the leaders of the Paris Commune were not entirely benevolent—their ways of dealing with political opponents could be barbaric. Many of the Communards’ rivals or opponents, especially within the Catholic Church, were imprisoned under the flimsiest of pretexts, and killed without a trial.

Women's Rights

Women played an active part in the Paris Commune, including fighting against the Versaillais and caring for wounded soldiers. Some women reportedly acted as p étroleuses , arsonists paid for throwing flammable petrol into opposition houses and other buildings.

There were also a number of feminist initiatives proposed to the Paris Commune, including equal wages for women, legalization of sex workers, the right to divorce and professional education for women. These proposals had limited success, however, since women were denied the right to vote, and there were no women in leadership positions in the Paris Commune.

Vendôme Column

Many participants in the Paris Commune had a decidedly destructive nature, and anything that smacked of monarchy rule was considered a target. Foremost among these was the Vendôme Column, a towering monument erected to honor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Called a “a monument of barbarism,” the movement to destroy the tower was started by artist Gustave Courbet , an elected member of the Paris Commune governing council. By May 16, the column was reduced to rubble before an enthusiastic crowd. Another target was the Paris residence of Adolphe Thiers, leader of the Third Republic. His home was looted and destroyed by an angry mob.

Paris Under Attack

In April 1871, fearing an impending attack, the leaders of the Paris Commune decided to mount an offensive against the Versaillais . After a couple of failed efforts, their attacks on the palace at Versailles were called off.

Thus emboldened, the Versaillais troops, led by Marshal Patrice Maurice de MacMahon, mounted an attack on the city of Paris, first entering through the unguarded city wall at Point du Jour. By May 22, more than 50,000 troops had moved into the city as far as the Champs Elysées, and the Paris Commune issued a call to arms.

But the city as a whole was unprepared for a massive invasion: Many street barricades were unmanned, and even the fortified hilltop at Montmartre had no stores of ammunition. Communard leaders, now fearful of any enemy, established a Committee of Public Safety, modeled after the notorious committee that carried out the most barbaric cruelties during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror in 1793-94.

Bloody Week

By May 23, the third day of what became known as Semaine Sanglante or “Bloody Week,” Third Republic Versaillais troops had overrun most of Paris, and the slaughter of Communards began in earnest.

As mayhem and terror swept through Paris, shooting and killing of Communards, government soldiers, Catholic clergy and ordinary citizens occurred day and night, often without any real cause, and the streets of Paris were littered with corpses. In one horrific example, more than 300 suspected Communards were massacred inside the Church of Saint-Marie-Madeleine by Versaillais troops.

In retaliation, the National Guard responded by looting and burning government buildings citywide. The Tuileries Palace , opulent home of French monarchs since Henry IV in 1594, the Palais d'Orsay , the Richelieu library of the Louvre and dozens of other landmark buildings were burned to the ground by National Guardsmen.

Paris Burns

Indeed, burning buildings were a common sight during Bloody Week, when the skies above Paris were black with smoke. One diarist wrote on May 24: “The night has been dreadful, with reciprocal fury. Shells, shrapnel, cannonade, musketry, all kept on bursting in a frightful concert. The sky itself is red, the flashes of the massacre have set it on fire.”

The Hôtel de Ville, seat of the Paris Commune government, was torched by Communards when they eventually came to realize theirs was a lost cause. The Palais de Justice was also reduced to a smoldering ruin. Both fires destroyed centuries of public records and other irreplaceable historic documents.

Members of the Catholic clergy were often targeted during Bloody Week: Even the Archbishop of Paris, Georges Darboy, was executed on May 24 by the Communards’ Committee of Public Safety, along with three priests and several other people.

Pere Lachaise Cemetery

In one of the most dramatic final episodes of Bloody Week, the Pere Lachaise Cemetery was occupied by hundreds of Communards. But after Versaillais troops used a cannon to blast open the cemetery gates on May 27, they stormed the cemetery and fought a pitched battle against Communards among the gravestones.

As evening fell, the revolutionaries finally succumbed, were lined up against the cemetery wall and shot by a firing squad.

After a hasty trial, prisoners from the nearby Mazas prison were also taken to the Pere Lachaise Cemetery, lined up against the same cemetery wall—now infamous as the Mur des Fé d é r é s or the Communards’ Wall—and shot. Roughly 150 people in total were executed and buried in a mass grave at the foot of the wall as Bloody Week ended.

Aftermath of the Paris Commune

Large sections of Paris were reduced to rubble after the madness and devastation of Bloody Week, which finally ended on May 28, when government forces took control of the city. More than 43,000 Parisians were arrested and held in camps; about half were soon released.

Some leaders of the Paris Commune were able to escape France to live abroad; others were exiled to the French territory of New Caledonia in the South Pacific, and a handful were executed for their role in the uprising. Eventually, many participants in the Paris Commune were granted amnesty.

For generations, researchers have tried to estimate the number of people killed in the Paris Commune, as well as its role in political history. At least 10,000 people were killed—most of those during Bloody Week—and as many as 20,000 deaths may have occurred, according to varying estimates.

Historians, politicians and French citizens continue to debate the significance, and the destructive violence, of the Paris Commune. Vladimir Lenin was favorably impressed by the revolutionary passions of the Communards; other leaders, including Mao Tse-Tung of China, were likewise inspired by the Paris Commune.

The event continues to spark debate: In May 2021—the 150th anniversary of the end of the Paris Commune—a “Martyrs' March” honoring the Catholic clergy killed during Bloody Week was attacked by an angry mob of anti-fascists. One marcher was hospitalized with injuries, and the march was ended early.

Many of the buildings destroyed or partially burned during the downfall of the Paris Commune were eventually rebuilt. All that remained of the Hôtel de Ville was its elegantly arched exterior shell, but it was rebuilt and once again serves as the city hall of Paris.

The ruined Palais d’Orsay is now reconstructed as the Musée d’Orsay , a popular destination for art lovers. Atop Montmartre, the white domes of the Basilica of Sacré Coeur gleam where the Communards’ cannons once stood. And the toppled ornate column was replaced in the Place Vendôme, where a statue of Napoleon once again looks across Paris.

Paris Commune: The revolt dividing France 150 years on. BBC News . The Paris Commune - from the archive, 1871. The Guardian . The Paris Commune: Ruins and Rebuilding. National Gallery of Art . The Paris Commune of 1871 – History of A Revolution In Eight Sites. Paris Insider Guide . Historical timeline: Paris, Montmartre and the Commune 1870 – 71. Montmartre Footsteps . The Fires of Paris. The New Yorker . Paris: a procession in memory of the Catholic martyrs of the Commune attacked by antifa. Le Figaro .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

Why the Paris Commune Still Resonates, 150 Years Later

- Back Issues

“Religion,” our new issue, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition today.

The Paris Commune ended on this day in 1871, after just two months in power. How do we explain, Enzo Traverso asks, the longevity and freshness of the memory of a fleeting revolutionary government?

A barricade in the Paris Commune, March 18, 1871. (Musée Carnavalet / Wikimedia Commons)

There is a paradoxical discrepancy between the meteoric rise and fall of the Paris Commune, whose life did not exceed seventy-two days, and its lasting presence as a central experience in the Left’s historical consciousness.

Viewed through the lens of what some scholars call “world history,” what happened in Paris between March 18 and May 28, 1871, is almost insignificant. Most recent historians of the nineteenth century — think of the acclaimed works of Christopher Bayly and Jürgen Osterhammel — just mention it as a minor detail of the Franco-Prussian War. From the point of view of the takeoff of industrial and financial capitalism, urbanization and modernization, the consolidation of colonial empires, and the persistence of the Old Regime in an already bourgeois continent, the Paris Commune means nothing.

Indeed, the Commune was even marginal in the Franco-Prussian War, since it happened seven months after Napoleon III’s capitulation and the proclamation of the Republic, and two months after signing the armistice that transferred Alsace-Lorraine to German sovereignty. At the beginning of March, the victorious Prussian army had already paraded down the Champs-Élysées.

How to explain, then, the longevity and freshness of the memory of such a fleeting event? The answer lies in that which, from the beginning, everybody realized: the Commune’s extraordinary symbolic dimension. They defended or stigmatized its legacy, but no one could ignore or diminish its impact. Many radical thinkers commemorated its martyrdom and welcomed it as both a sunset and a dawn: the end of the sequence of nineteenth-century democratic upheavals and the beginning of a new era of proletarian revolutions.

Carrying the Torch

Anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin depicted the Commune as the announcement of the future, and Karl Marx emphasized the communist potentialities of the Paris experiment: “It was essentially a working-class government, the product of the struggle of the producing against the appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.”

As a nuanced historian like Georges Haupt pointed out, the Paris Commune quickly became both a symbol and an example : a symbol of socialism as a possible and desirable future, and an example to be integrated into socialist memory and to be critically meditated upon in view of the forthcoming struggles.

In the twentieth century, the legacy of the Paris Commune was largely appropriated and reinterpreted in the light of the Russian Revolution. During the crucial year 1917, and later, during the Russian Civil War, the Paris Commune haunted the Bolsheviks’ mind as — alternatively — a warning and a model. October 1917 had reinforced the symbol: the announcement of a new socialist age was no illusion. But it had also assimilated the lessons of the tragic defeat of 1871: the Bolsheviks should not repeat the delays, hesitations, and weaknesses of the Communards. In Russia, the White Army had been defeated by a stronger and pitiless revolutionary Terror.

In 1891, Friedrich Engels had defined the Paris Commune as a paradigm: it had showed what the “dictatorship of the proletariat” would look like. After 1917, the Commune became a prefiguration of the Bolshevik Revolution — it was relocated into a sequence representing the ascending march of socialism from its infancy in 1789 to its triumph in 1917, passing through 1830, 1848, and, precisely, 1871.

After the Second World War, this image was further reinforced by adding new steps on the irresistible advance toward socialism: China in 1949, Cuba in 1958, etc. The Commune ––a sudden, unexpected and creative break of the historical continuum — had become a landmark in a new linear evolution theorized with the categories of Marxist historicism. The Communards had become heroic precursors.

The Bolshevik attempt at inscribing the Paris Commune into a communist Pantheon is certainly debatable, but it should be critically understood rather than contemptuously rejected. No doubt, the Bolsheviks were obsessed with “the laws of history,” which they believed to have mastered and in which they located the supreme legitimacy of their political choices.

When Leon Trotsky wrote Terrorism and Communism (1920) from his armored train, in the middle of a bloody civil war, Soviet power was struggling for its survival. In his mind, the ghosts of the Paris Commune were not rhetorical figures; they strongly resonated with the present as dramatic warnings. This was neither propaganda nor mythology: it was rather an extraordinary moment of empathy with the vanquished, when the past resurfaced into the present and cried out to be rescued. But it remained a revisitation of the Commune through a purely military prism.

72 Days of Utopia

The Communards, however, did not consider themselves as the actors or forerunners of a communist revolution. It was the Versailles propaganda that, emphasizing the significant presence of the disciples of Louis Auguste Blanqui among its leaders, denounced the Commune as a dangerous form of atheistic, vandalic, and barbarous communism. In its journals and its public debates, as well as in many testimonies of its protagonists, the Commune was usually described as a model of the “universal Republic” or, more pragmatically, as an experience of the “democratic and social Republic.” In fact, with very few exceptions, its actors did not wish to apply ideologies or preestablished measures; they invented a new form of social and political power, maybe even new “forms of life,” in the extraordinary circumstances of war and civil war, in a besieged and impoverished city.

In a retrospective reflection, Élisée Reclus, the anarchist geographer who was one of its actors, described the Commune as:

a new society in which there are no masters by birth, title or wealth, and no slaves by origin, caste or salary. Everywhere the word “commune” was understood in the largest sense, as referring to a new humanity, made up of free and equal companions, oblivious to the existence of old boundaries, helping each other in peace from one end of the world to the other.

Initially, the Commune was a new levée en masse , inspired by the example of 1792, against the German enemy that had invaded the country and against the French government that wished to dismantle the defense of the city: the cannons of Belleville and Montmartre controlled by the National Guard. In other words, this revolutionary patriotism was directed against both an external enemy and the internal threat embodied by Adolphe Thiers and his executive of a conservative and monarchist majority in the newly proclaimed Republic.

The insurgents wished to establish a popular power based on principles of freedom, horizontal democracy, self-government, social justice, and equality, without knowing very well how these goals could be concretely realized. Moreover, they claimed the restoration of municipal liberties and prerogatives confiscated by an authoritarian regime. They called “communalism” this federalist conception of democracy and self-management, a conception to which they were strongly attached (and which will become one of their major weaknesses in the eyes of Vladimir Lenin and Trotsky). Thus, their experience did not consist in applying preexisting models, according to the tradition of French utopian socialism; rather, they sought to invent a new utopia. They created something that did not exist before, brought forward by what Ernst Bloch called the “hot currents” of utopianism.

The Paris Commune did not put into question the principle of property but submitted it to the priorities of collective needs. Instead of being a source of inequalities, property had to be “just and equitable.” It abolished debts at the pawn shops, fixed decent salaries, and established the self-management of the factories abandoned by their owners, when a significant part of the bourgeois class left the insurgent city. It abolished night shifts in the bakeries and introduced everywhere the election of labor representatives. It suspended the payment of rentals and requisitioned vacant housing. It did not take over the Bank of France, which belonged to the entire nation, thus leaving to its enemies a powerful weapon (another symptom of weakness, according to Marx and the Bolsheviks). Paris was as a city — the third-largest city in the world at the time — in which the power had been conquered by the laboring classes.

Among its juridical and political conquests, the Paris Commune established complete separation between the state and the Catholic Church, which had been a pillar of conservatism and Napoleon III’s regime. Secularism was extended to education, where female teachers obtained the same wages as their male colleagues. A reactionary conception of family was laid down by recognizing cohabiting couples and giving equal rights to their members; prostitution was assimilated to a form of slavery and abolished. The Commune did not extend voting rights to women — it is significant that neither Marx nor Lenin mentioned this as one of its limits or mistakes — but it gave them a new position in society.

The presence of women in the Commune was remarkable to the point that it became an obsessive target of Versailles propaganda, which depicted them as the pétroleuses : witches, harpies, nymphomaniacs, hysterical bodies, degenerated females who destroyed their families and all traditional values, abandoned their children and enjoyed the spectacle of fire in rapturous rituals. For decades, this negative myth would haunt conservative imaginaries around the world.

For the seventy-two days the Commune existed, such emancipatory measures were proclaimed and had begun to be applied, but, beyond these formal policy reforms, the entire city seemed captured by an extraordinary effervescence and engaged in a process of social transformation from below. Artists and intellectuals — Paris was then the capital of European literary bohemia — created their own federations. Popular newspapers and graphic arts flourished for two months in a country whose official culture was radically hostile to the lower classes, usually depicting them as a despicable “mob.”

Anti-clericalism and revolutionary iconoclasm frightened the ruling classes of the entire continent. The demolition of the Vendôme Column, described by the Communards as a symbol of militarism, imperialism, “false glory,” and “an insult by the victors to the vanquished,” became evidence of the Commune’s “vandalism,” which Gustave Courbet, the famous painter who led the Federation of Artists, paid for with imprisonment and exile.

Born as an expression of revolutionary patriotism, the Commune was deeply internationalist. It proclaimed that “any city should be authorized to confer citizenship to the foreigners who serve it,” and gave a concrete meaning to its principle of “universal Republic” by integrating thousands of immigrants, exiles, and refugees who lived in the French capital. The archives record 1,725 foreign Communards, and in many cases, they took on important responsibilities: two out of three Commune armies were led by Polish commanders in chief, and the National Guard included an Italian legion. Many foreigners belonged to its board, like Léo Frankel, a Hungarian Jewish member of the International Working Men’s Association, who was appointed minister of labor.

The most indisputable evidence that the Commune had destroyed the bourgeois order lies in its replacement of the state military force with the National Guard, which had been rebuilt during the war as a popular militia. Writing on the spot, just after its final annihilation during the “bloody week” of May, Marx pointed out two distinctive features of the Paris Commune: its rupture with the state repressive machinery and its radical democracy. After conquering power, the working class quickly realized that it could not “simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” The old state military force had to be replaced with “the armed people.”

Similarly, the working class created its own organs of power:

The Commune was formed of the municipal councilors, chosen by universal suffrage in the various wards of the town, responsible and revocable at short terms. The majority of its members were naturally working men, or acknowledged representatives of the working class. The Commune was a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time.

Nobody knows if such a form of radical, direct democracy could work in the long term. In the USSR, it never really worked, except for a few months, because of the breakout of the civil war and the establishment of a party dictatorship. The horizontal character of democracy under the Commune was probably reinforced by the lack of charismatic leaders dominating its assemblies and institutions. There was a plurality of remarkable personalities but no overwhelming figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, Lenin, or Trotsky.

This also depended on a curious coincidence: Bakunin was in Lyon and could not join Paris under siege; Auguste Blanqui had been arrested in southern France one day before the uprising of March 18. Therefore, radical democrats, social republicans, anarchists, Proudhonists, Blanquists, and even Marxists (a few Communards had a regular correspondence with the author of The Communist Manifesto living in London) worked together without struggling for a partisan leadership. In many cases, as during the crucial ballot for creating the Committee of Public Safety, the Blanquists and the members of the International Working Men’s Association did not vote unanimously. This plurality of views was fruitful.

The Commune was simultaneously a “destituent” power that destroyed the old state machinery, and a “constituent” power that established a new sovereignty opposed to the Versailles government. Thus, it was shaped by the tensions and ruptures that characterize any revolutionary process: on the one hand, the enthusiasm for a conquered freedom and the emotional élan of building the future; on the other hand, the necessity of creating new organs of coercion able to resist the inevitable reaction of the old rulers. Democratic communalism coexisted with a latent dictatorship in the middle of a civil war. The authoritarian measures claimed by Raoul Rigault, the Blanquist head of the Commune’s security, echoed the Jacobin Terror and foreshadowed the Soviet Cheka. In the most dramatic moments of its ephemeral existence, the Commune executed its hostages.

Enemies of the Commune

Between the bloody week of May 1871 and the Russian Revolution, the memory of the Commune was censured and exorcised. For a decade, it was silently preserved by the vanquished and critically transmitted by the exiled. In France, the Commune became an unnamable event, always evoked by frightening allegories as a natural catastrophe. Its actors and accomplishments became the objects of a damnatio memoriae that simply erased them from the public sphere. At the top of Montmartre hill, where the uprising had started, the Sacré-Cœur basilica was built “to expiate the crimes of the Commune,” which had executed the archbishop of Paris. Just after the repression, photogravures showing the Communards’ deeds — from the execution of priests and the burning of churches to the destruction of property — inundated the entire country, gathered under the title The Red Sabbat . In the following years, the adjective “red” was banned from official documents.

While attracting socialist, anarchist, bohemian, and nonconformist writers and artists — think of painters such as Courbet, Honoré Daumier, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Édouard Manet, or writers like Jules Vallès and the young poet Arthur Rimbaud — the Commune was condemned by the overwhelming majority of French intellectuals. Gustave Flaubert, Victor Hugo, Edgar Quinet, George Sand, and Émile Zola viewed the Commune as an outburst of blind violence, even if some of them pleaded for amnesty after the bloody week.

For the French intellectual elite, the Commune did not result from a civil war; it was the awful expression of a collective disease, of a pandemic that threatened the national body and had to be crushed. As Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, the most significant feature of anti-Commune literature was its “social biologism,” which consisted in associating class conflicts with natural pathologies. In his novel devoted to the Franco-Prussian War, La Débâcle (1892), Zola described the Commune as “a growing epidemic” and a “chronic befuddlement” provoked by hunger, alcohol, and syphilis under the conditions of a besieged city. In The Origins of Contemporary France (1878), historian Hippolyte Taine analyzed it as “a pathological germ which, having penetrated the blood of a suffering and seriously sick society, produced fever, delirium, and revolutionary convulsions.”

According to Maxime Du Camp, “virtually all those unfortunates who fought for the Commune were what alienism terms ‘sick.’” Cesare Lombroso, the Italian founder of criminal anthropology, submitted the Commune to the indisputable “scientific” test of anthropometry and, after analyzing the skulls of dozens of Communards, concluded that most of them revealed the typical traits of the “born criminal.” Many commentators privileged the language of zoology, grasping among the Communards the symptoms of bestiality and lycanthropy, a form of “barbaric regression” within a civilized world. In October 1871, Théophile Gautier compared the Communards to zoo animals that had suddenly escaped from their cages and terrorized in the city:

wild beasts, stinking animals, venomous creatures, all the refractory perversities that civilization has been unable to tame, those who love blood, those who are as amused by arson as by fireworks, those for whom theft is a delight, those for whom rape represents love, all those with the hearts of monsters, all those with deformed souls.

Such a demonic portrait was not exclusively French. In the United States, the Chicago Tribune compared the Paris Commune to an uprising of Comanche Indians. In Buenos Aires, La Nación deplored the Communards’ crimes and denounced the inspirer behind their attacks against civilization: Marx, “a true Lucifer,” whose letters from London had been found in the files of the Blanquist Raoul Rigault, the leader of the Committee of Public Safety. The myth of a “cosmopolitan” conspiracy behind the deeds of the Parisian workers focused on the International Workingmen’s Association, which became a sort of Satanic nightmare for European reaction and, in parallel, according to Friedrich Engels, a “moral force” for the labor movement throughout the world.

The colorful rhetoric of the Commune’s enemies belongs to a rich counterrevolutionary tradition. After the Russian Revolution, the language of reaction did not change significantly. Think of the White Guards’ posters portraying Trotsky as a Jewish ogre, or even of Winston Churchill, who depicted the Bolsheviks as a horde of baboons jumping on a hill made of the skulls of their victims.

The bloody week of May 1871 was, at the same time, the sunset of the old counterrevolutions and the dawn of modern state repression. Fought on the barricades, it appeared at first glance as a repetition of June 1848, but this was a misleading facade. Most of the fallen Communards were not killed in the street combats but were executed, after summary trials, through methodic and serialized massacres. The Versailles army was composed neither of fanatic Bonapartists nor of provincial obscurantists who wished to punish a detested capital.

As historian Robert Tombs has convincingly explained, the soldiers who performed this planned, disciplined, organized, and impersonal slaughter did not carry the awareness that they were crushing a political uprising; they rather thought that they were extinguishing a criminal fire and cleansing the city of a dangerous disease. They acted without emotion, accomplishing a biopolitical task in order to sanitize a national body. Whereas General Patrice de MacMahon repeated in May 1871 the gestures of General Louis-Eugène Cavaignac in June 1848, his soldiers perpetrated a massacre that, revisited in the twenty-first century, brings to mind the systematic murder perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen in 1943.

The magnitude of the repression was considerable. Historians are still investigating the number of the dead, with estimates varying from 5,400 to 20,000. This significant discrepancy results from the difficulty of accounting for the dead in the streets, the victims of military executions and the thousands who perished in the following days of untreated wounds. The report established in 1875 by General Raymond Appert of the Versailles army mentioned 38,614 arrests and 50,000 sentences issued by the war council, which resulted in more than 10,000 convictions. A further 3,800 Communards were deported to New Caledonia (where many of them supported the Kanak rebellion in 1878).

Almost 6,000 among those who escaped from capture spent the following decade in exile. Most of them fled to England, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, and Italy, but also to the United States and several Latin American countries. We know the names of many exiled intellectuals (Gustave Courbet, Leó Frankel, Paul Lafargue, Louise Michel, Élie and Élisée Reclus, Jules Vallès), but the great majority of the exiles were craftsmen and manual workers.

Twenty-First-Century Communes

The ghosts of the Commune have resurfaced in the twenty-first century. We heard their echoes in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 2006 , then in 2011, first in Tunisia and Egypt, then in New York, with Occupy Wall Street, and in Puerta del Sol, Madrid, with the 15M. A few years later they came back to France, with the Nuit debout of spring 2017 in Paris and the ZAD (“zones to defend”) of Brittany. The Kurdish fighters of Rojava claimed the Commune’s legacy by creating an incredible experience of armed, egalitarian, feminist, direct democracy in a Middle East devastated by neocolonial, fascist, and fundamentalist wars. To all of them, the Commune was meaningful, the opposite of a dead realm of memory.

Once again, the Commune’s legacy has experienced an unexpected metamorphosis. An eloquent mirror of this change is the afterlife of Louise Michel, one of the most popular figures of the Paris uprising, whose virtuous and sacrificial image of the “red virgin” has been replaced by that of a queer feminist. And a similar shift has occurred with the social dimension of the Commune. Its actors are increasingly recognized as craftsmen, workers, teachers, militiamen of the National Guard, employees, bohemian artists and writers; a minority of them were factory workers, while a great number were seasonal or daily laborers.

The social profile of the average Communard was much closer to that of many contemporary young people — precarious workers, students, and intellectuals — than to that of twentieth-century industrial workers. The heterogeneous internal composition of this largely preindustrial working class is now seen to bear many affinities, despite their different historical contexts, with the postindustrial proletarian layers of neoliberal capitalism. They did and do not believe in linear and gradual progress, but rather express a certain proclivity for radical breaks, as profound as they are ephemeral. Whereas its social and political conquests were quickly destroyed — some of them would be achieved decades later — the Commune has survived throughout a century and a half as, above all, the interruption of the homogeneous and linear time of capitalism and the irruption of a new, qualitative time of self-emancipation. From this point of view, it has not become a “future past” — a bygone nineteenth-century utopia — but remains the representation of a possible future that still reverberates in the present.

Liberated from the historical teleology of twentieth-century communism, the Commune has been extracted from the sequence of defeated twentieth-century revolutions and rediscovered as a moment of singular and irreducible collective freedom. No longer viewed as an immature and ephemeral prefiguration of Bolshevism, its relevance and actuality are grasped precisely in what was usually considered its main limits: its lack of centralism, hierarchies, or hegemonic leadership; its federalism; and its search for new forms of horizontal democracy rather than building an effective dictatorship.

In short, what is rediscovered in the Commune is its communalism , which powerfully resonates with current debates about the “commons”: a collective reappropriation of nature, knowledge, and wealth against the neoliberal process of global privatization. Like the Commune, the recent experiences mentioned above did not aim at applying abstract models; they were creative moments of the invention of the future.

In this way, they fit remarkably the definition of the Commune given by Engels in 1875 in a letter to August Bebel whose relevance has been pertinently pointed out by Kristin Ross. The word “Commune,” Engels explained, does not correspond with “community” or “municipality.” He saw it as the equivalent of the “excellent old German word Gemeinwesen ,” which did not designate a “state” but rather “what exists in common.” In a letter to his friend Ludwig Kugelmann, written in April 1871, Marx defined the Paris Commune with a lyric image, a metaphor borrowed from Homer: “storming heaven.”

Like Titans assaulting Olympus, they had overthrown their own rulers. This is, perhaps, the key to understanding the incredible longevity of those seventy-two Parisian spring days in 1871.

When the Village was Red: Celebrating the Legacy of the Paris Commune in our Neighborhoods

By Lena Rubin

On March 18, 1871, the Paris Commune began — a three-month-long worker-led insurrection in Paris and experiment in self-governance. On that day, workers, anarchists, communists, and artisans took over the city, and began to re-organize it according to the principles of association, self-determination, and justice for all oppressed members of society.

Notably, among the so-called Communards who participated in the uprising, many were women. The Versailles press wrote that such women were “seduced by the theories of socialism developed in clubs and public reunions, thinking that a new era was going to open itself… they are throwing themselves wholeheartedly into the revolutionary movement…”

As scholar David P. Jordan wrote, “unopposed and swept along by a ‘human torrent,’ workers occupied all the administrative offices and government buildings… the mayor, Jules Ferry, fled the Hôtel de Ville [the site of executive governmental power in Paris at the time]. Paris was in the hands of the commune.”

While in power, the communal government advocated for womens’ rights, universal free education, established a radical artists collective called Le Féderation des Artistes, and much more.

The Commune only lasted for seventy-two days before it was brutally crushed by the Versailles government, in what is now known as Le Sémaine Sanglante (or, the Bloody Week). Communards were executed en masse, and many were deported to the French territory of New Caledonia or found themselves in exile elsewhere. Due in part to the many who fled retribution or were forced to leave after the Commune was crushed, its ideas spread far and wide in the decades that followed. Many scholars write on what is called the “afterlives” or “reactivations” of the Paris Commune — from the worker-led Mexican Zapatista revolution, to the urban insurrection of Occupy Wall Street and associated Occupy movements. As Kristin Ross author of the wonderful study of the Commune entitled Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune , states, “the shockwaves of [the Bloody Week] propelled the hard-pressed Communard exiles and refugees into far-reaching new political networks and ways of living… creating networks and pathways of survival, reinvention and political transmission.”

One of the most prominent places in which the Communards created new communities, and ways to survive, was in our very own Greenwich Village — in the area just south of Washington Square, which was once known as New York’s “French Quarter.”

By the later 19th century, this area was already considered to be the center of New York’s “bohemia,” and was teeming with multicultural communities. Other waves of immigration had created ethnic enclaves downtown, including the German community of Kleindeutschland and the Irish neighborhood of Five Points. In the “Quartier Français,” cafés and restaurants nurtured ever-growing communities of French artists, writers, and leftists activists in the wake of the Commune.

About eight years after the destruction of the Commune and the execution and deportation of the Communards, a journalist in Scribner’s Monthly wrote:

“I CONFESS to finding no little pleasure in lazy explorations of the region that lies west of Broadway, south of Washington Square, and north of Grand street. This is the Quartier Francais of New York… The commonplace, heterogeneous style of the buildings, and the unswerving rectangular course of the streets are American, but the people are nearly all French. French, too, is the language of the signs over the doors and in the windows; and the population is of the lowest and poorest class. The Commune has its emissaries and exiles here….There are secret meetings in obscure little cafés, into which strangers seldom enter; where the last movements of the Nihilists are discussed… over draughts of absinthe and more innocent beer.”

The writer also describes the manual labor trades taken on by these French immigrants: “Mademoiselle Berthe, with her little sisters, fabricates roses and violets out of muslin and wax in the high attics of the tenement houses. Madame Lange, with her arms and neck exposed, may be seen ironing snowy linen in front of an open window. Here is Triquet, le charcutier; Roux, le bottier; Malvaison, le marchand de vin; Givac, le charcutier Alsacien, and innumerable basement restaurants, where dinner vin compris, may be had for the veriest trifle.”

From the 1870s to the 1890s, approximately 20,000 French immigrants lived and worked in this area, according to the blog Ephemeral New York. “Bakeries, butchers, cafés, shops, and ‘innumerable basement restaurants,’ occupied the short buildings and tenements of this expat enclave.”

The broader community may have categorized the Parisian exiles as “political refugees of dangerous proclivities,” or as “having a share in the blazing terrors of the Commune… in all their wanderings they had carried the spirit of revolution with them and spouted death to despots over their glasses of absinthe in cellar cafés.” Another Scribners article notes that at the Taverne Alsacienne on Greene Street, ex-Communards “gathered around the tables… most of them without coats, the shabbiness of their other garments lighted up by a brilliant red bandana kerchief or a crimson over-shirt.” (Wearing red accents or accessories was a common practice of Communards during March-May 1871, as a way of demonstrating one’s commitment to socialist revolution.) The community was boisterous, its members frequently drinking “wine, vermouth, and greenish opaline draughts of absinthe… their eyes brighten and their tongues are loosened.”

One of the most notable sites of the “old Bohemia of the French Quarter” south of Washington Square was the Restaurant du Grand Vatel on Bleecker Street, where Parisian exiles mingled with American artists and authors. In fact, an eighth anniversary celebration of the bloody revolution of March 18, 1871 was held here. The celebratory scene, which involved, “grand festival, banquet, ball, and artistic tombola,” led the Scribners journalist to conclude, “the Restaurant du Grand Vatel has some queer patrons.”

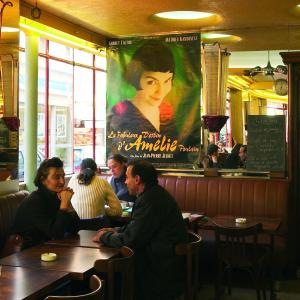

Another important echo of the Communard’s legacy in our neighborhoods was the Paris Commune bistro at 99 Bank Street. The restaurant originally opened on Bleecker Street in 1979 and relocated to Bank Street after a forced eviction—eventually closing in the early 2000s. It was a thriving and well-loved neighborhood gathering spot in the 1980s and 1990s and early 2000s, run by the French chef Hugo Uys; the New York Times called it a “quintessential old West Village restaurant.” Its red interior accents and festive, communal atmosphere carried on the legacy of both 1871 Paris and the nineteenth-century French Quarter.

Interested in learning more about the afterlives of the Paris Commune in our neighborhoods? Be sure to check out our upcoming event on April 7th, with the scholar J. Michelle Coghlan, When the Village Was Red: Radical New York & the Paris Commune on its 150th Anniversary!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Paris Commune - from the archive, 1871

On 28 May 1871, French soldiers crushed the Paris Commune, a socialist government that had ruled the city for two months. See how the Guardian and Observer reported the insurrection

The Paris Commune was a radical, popular led government that ruled Paris from 18 March to 28 May, 1871. It occurred in the wake of France’s defeat in the Franco-German war and the collapse of Napoleon III’s Second Empire (1852–70). Parisians united to overthrow the existing French regime which had failed to protect them from the Prussian siege. The elected council of the Commune passed socialist policies and oversaw city functions but was eventually overthrown when the French army retook the city. About 20,000 insurrectionists were killed, 38,000 arrested and more than 7,000 deported.

Editorial: the capitulation of Paris

3 March 1871

Victor Hugo, in the Misérables, describes the 18th of June, 1815, as “the most mournful day in the history of France;” but he himself probably will now be the first to transfer the title to this sad pre-eminence to the 1st of March, 1871. On Wednesday last France was doubly humiliated; Prussian troops entered Paris for the third time this century and on the same day the French National Assembly, compelled to meet far away in a provincial city, ratified a treaty of peace which proclaims in every line the utterly prostrate and helpless state of the nation.

The state of Paris

From an occasional correspondent 3 April 1871

Paris is again a besieged city. The Government has interrupted the mails, and none of the trains are running. There is a report that the army is concentrating at Courbevoie and Puteaux to march upon Paris to-morrow. The Commune is strengthening all its positions. The Place Vendôme bristles with bayonets; every foot of ground is covered with armed men. The Grand Hotel has been occupied by the National Guards, and all the windows looking on the Rue de la Paix and the adjacent streets were barricaded with sand bags, loopholes being left for Musketeers.300,000 francs have been requisitioned from the railways.

The Bank of France has taken a large printing office for the purpose of printing 10-franc notes for the Commune. The notes will be issued under duress and protest. The Bank is still open and transacts business as usual.

There are no obstructions yet on the bridges. All the public buildings near the old Hotel Dieu, and the Hotel itself, have been turned into fortresses by the Commune. [Adolphe] Assi and the other members of the Comnune ride about in state, preceded by outriders and followed by a motley staff.

The spies of the Government at Versailles report that the Commune has 156,000 men under arms. The secret societies here reckon they have 120,000 men. Both these figures are exaggerated. The paper strength of all their battalions is 120,000 men, but not half their battalions number more than 80 men who will serve.

It is now said at Versailles, that Marshal MacMahon will command the army. General Chanzy did not give his parole to take no part in the operations against the insurgents. When the decree remitting house rent was published it was received in several model lodging-houses amid prolonged shouts of “Vive la Republique démocratique et sociale.”

The dissensions in the Commune are great, but the Head Committee of six remain of one mind and control everything. The number of regular soldiers of all arms now in Paris is amazing. They swarm in every street. It is positively known that 33 men have been put to death by the Central Committee or their myrmidons since the 18th of March. This number does not include those killed in the Rue de la Paix. They were executed on the most frivolous pretexts. Three of them were shot by National Guards at Belleville because the latter did not admire the way they were dressed. As I close my dispatch, I hear the Government will begin to throw its troops across the river at midnight to-night.

Paris in flames as communards vanquished

From our own correspondent 25 May 1871

A terrible fire is raging in the chief centre of Paris. The Versailles batteries are firing furiously against the quarters which still hold out. By the aid of the telescope the horrible fact is disclosed of numerous dead and wounded being left lying about the streets without any succour whatever.

Massacres in Paris as army takes control

1 June 1871

Civil government is temporarily suspended in Paris. the city is divided into four districts, under Generals Ladmirault, Cissey, Douay, and Vinoy. “All powers of the civil authorities for the maintenance of order are transferred to the military.” Summary executions continue, and military deserters, incendiaries, and members of the Commune are shot without mercy.

Paris after the conflagration

From our special correspondent The Observer, 4 June 1871

I doubt whether anyone out of Paris can quite realise the horror of the situation during the latter days of last week. For at least four days and nights every inmate of each one of the countless apartments in the city was in perpetual dread of death by fire. The inflammable shells of the insurgents were being sown broadcast over the town from the batteries of Montmartre and Belleville, and all about the city there were agents or emissaries of the Commune crouching about and trying to set fire to any house into whose apertures they could pour petroleum. I am quite willing to admit that there has been immense exaggeration about the number and the activity of these agents. In times of panic like the present there is no story too monstrous to be credited for the moment. Only yesterday I was speaking to a shopkeeper whom I have known for years, and was congratulating him on it all being over. “Ah. Monsieur,” he answered, “who can say it is over yet? I cannot shut my eyes without seeing the flames. I cannot sleep at night without dreaming the house is on fire.” And if, as I believe, this saying represents the feeling to-day of vast numbers of Parisians, one can realise what their agony must have been when the air was filled with smoke, and when on every side you could see nothing but flames.

There is no counsellor so cruel as fear, and I cannot doubt that the reprisals committed by the French troops have been often brutally, savagely cruel.

A woman’s diary during the Paris Commune

From a correspondent 26 July 1872

The Commune has had its military and its political historians, both friendly and unfriendly, the optimist account of these being as unworthy of credit as the pessimist account. A book which might adopt for its own the epigraph which precedes Montaigne’s essays, ‘ C’est icy un livre de bonne foi, lecteur ,’ was still a desideratum till Madame Blanchecotte published her Tablettes d’une Femme pendant la Commune . This lady is the authoress of two works on moral philosophy, crowned by the French Academy, and served in the ambulances during the Prussian siege. During that terrible period she had become accustomed to the smell of powder, and insensible of the horrid din of artillery. This rude apprenticeship, therefore, had fitted her to be a calm, though reflective, and feeling, spectator of the terrible civil war which broke out on the 18th March, 1871.

Tuesday, April 15 The people are greedy of strong emotions; they take pleasure in seeing the burials of slain insurgents pass; they are delighted if any ferocious exhibition of unrecognised dead gives them the spectacle of open coffins. I have heard pretty shop girls, with sweet eyes, complaisantly communicate these cemetery impressions. Young mothers take their children there; the little ones are glad; they have seen corpses, and they tell it with pride to the others.”

April 29 As I was going home in the ‘bus this afternoon, I could not help looking continually at the face of a growing lad, so naif , so good-humoured, so young, and so communicative beneath his military equipment of sword and gun, that I asked, “Why, my child, how old are:you?” “Seventeen, madame. I am a volunteer; for do you see, I belong to the people. My grandfather was killed in the insurrection of June, 1848; my father died of grief; and my mother said to me, ‘Avenge them.’ It’s not to say we shall win; we never do win. We are sheep, and we shall always be shorn.”

Wednesday, May 24 The night has been dreadful, with reciprocal fury. Shells, shrapnel, cannonade, musketry, all kept on bursting in a frightful concert. The sky itself is red, the flashes of the massacre have set it on fire; the action is quite near, at the Luxembourg; we can see the fire and smoke of the combat; they are firing from every part, from the roofs, the windows, the cellars.

3 am: Ambulance carts are passing red with blood; under blankets that are too short; dead bodies are jostled; they are picking them up by cartfuls at a time. Our barricade has at last become ‘serious,’ it is a model. They have made loopholes; a mitrailleur is already is position, and an enormous cannon is waiting to take its place. A young artilleryman bestrides it with fixed gaze and folded arms. He scarcely replies to those who speak to him. More and more powder passes by unceasingly to increase the frightful reserve of the Pantheon. It is the aged insurgents who have guarded the barricades during the night. They are shivering in the morning air.

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

- From the Guardian archive

Most viewed

The Paris Commune, 150 years on – from the siege of the capital to ‘Bloody Week’

The Paris Commune began an insurrection on March 18, 1871, when the largely left-wing, radical National Guard refused to accept the authority of the French government, killed two generals and took control of Paris – initiating the Communards’ febrile two-month rule over the City of Light. FRANCE 24 looks back at this seminal moment in French history, 150 years on.

Issued on: 18/03/2021 - 09:38

The catalyst for the Paris Commune was France ’s crushing defeat in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War – “La Débâcle”, as Émile Zola christened it in his renowned 1892 novel. France’s Emperor Napoleon III was captured in September 1870, the same month the Prussians besieged Paris. The 1.7 million Parisians spent 135 days under siege, increasingly starved of resources. The City of Light surrendered in January 1871.

The same month, the French government signed the Armistice of Versailles with Otto von Bismarck, Prussian leader and soon-to-be chancellor of a united Germany. Bismarck agreed that Prussian troops would not occupy Paris. Instead, France’s National Guard would keep order in the capital , where socialist movements such as the First International had burgeoned over the preceding years .

France’s largely Catholic, conservative electorate voted in a right-wing majority in February’s parliamentary elections. The left-wing radicals in the National Guard controlling Paris did not accept this result – setting the stage for the Commune’s emergence the following month.

“The sight of ruins is nothing compared to the great Parisian insanity,” one giant of French literature, Gustave Flaubert, wrote to another, George Sand, after visiting Paris following the Commune’s bloody defeat in May 1871. “One half of the population longs to hang the other half, which returns the compliment,” Flaubert continued, having opposed the Commune from the start.

FRANCE 24 discussed the Paris Commune with British historian Jonathan Fenby, author of "The History of Modern France".

What caused the inception of the Paris Commune in March 1871?

One can trace the long-term causes behind the Commune to the Revolution of 1789. France had gone through a series of revolutions, 1789, 1830, 1848, and each one had emerged from a big push from the left and had ended up – with Napoleon, with King Louis-Philippe and then with Napoleon III. Revolutionary sentiment had gestated during that time in Paris.

When in 1870 France lost the Franco-Prussian War, that led to the siege of Paris and then the peace treaty at the beginning of 1871, which a lot of the radicals in Paris refused to accept. They thought the war could go on, should go on, and when national elections in France returned a right-wing majority in the National Assembly, the radicals of Paris wanted to go their own way.

The parliamentary majority was very conservative and had a strong monarchist group within it. So there was a definite division between France as a whole and Paris, where the radicals were much stronger.

How did the Communards take control of Paris?

Hostilities broke out between the National Guard, which was the military force within Paris itself, left over from the siege, and the national government of Adolphe Thiers over who should take control of several hundred old cannon guns in various parts of Paris. The National Guard refused to give way, and was supported by many sympathetic Parisians. Two generals were killed, and Thiers and the government left for Versailles – at which point what was to become the Commune took over in Paris.

The National Guard was the dominant force within Paris itself because the French army had largely been disarmed, either through being defeated by the Prussians during the war or through the subsequent peace treaty. The National Guard was left in Paris and was meant to keep control there, but it turned out to be a much more radical force than either Thiers or the Prussians had expected.

What was life like for Parisians under the Commune during its two-month reign over the City of Light?

As well as a divide between Paris and the rest of France, there was a divide within Paris itself – between the more radical parts of the city and the more bourgeois sections of Paris which had grown under Napoleon III, especially with Baron Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris.

When there were elections for the 92-member council running the Commune at the end of March, there were very high abstention rates in the bourgeois areas of Paris. Quite a lot of their inhabitants left the city at some point or other during the Commune.

Life was very disjointed during the Commune period. Each district council ran itself; there was no single leader. Leadership decisions were often very confused.