The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

B.7 – Tourism and Transport

Author: dr. jean-paul rodrigue.

Tourism, as an economic activity, relies on transportation to bring tourists to destinations, and transportation can be part of the touristic experience.

1. The Emergence of the Tourism Industry

Since the 1970s where tourism became increasingly affordable, the number of international tourists has more than doubled . The expansion of international tourism has a large impact on the discipline of transport geography since it links traffic generation, interactions at different scales (from the local to the global), and the related transportation modes and terminals. As of 2016, 1.2 billion international tourist receipts were accounted for, representing more than 10% of the global population. The industry is also a large employer accounting for 10% of all the global employment; 30 tourist visits are usually associated with one job. 30% of the global trade of services is accounted for by tourism. Tourism dominantly takes place in Europe and North America , but geographical diversification is taking place.

Traveling has always been an important feature, but its function has substantially evolved. Historically, travelers were explorers and merchants looking to learn about regions, potential markets and to find goods and resources. The risks and exoticism associated also attracted the elite that could afford the large expenses and the time required to travel to other remote destinations. Many wrote realistic and even imaginary travel accounts. As time moved on and as transportation became more reliable, traveling became a more mundane activity taking place in an organized environment; tourism. In the modern world, traveling is more centered around annual holidays and can be reasonably well predicted.

As an economic activity, tourism is characterized by a high demand level of elasticity. As transport costs are significant for international transportation, cost fluctuations strongly influence demand. Therefore, transport is a key element in the tourism industry. The demand in international and even national transport infrastructures implies a large number of people to be transported in an efficient, fast, and inexpensive manner. It requires heavy investments and complex organization. Well-organized terminals and planned schedules are essential in promoting adequate transportation facilities for tourists, notably since the industry is growing at a fast rate.

Transport is the cause and the effect of the growth of tourism. First, the improved facilities have incited tourism , and the expansion of tourism has prompted the development of transport infrastructure. Accessibility is the main function behind the basics of tourism transport. In order to access sought-after destinations, tourists have a range of transportation modes that are often used in a sequence. Air transport is the primary mode for international tourism, which usually entails travel over long distances. Growth rates of international air traffic are pegged to growth rates of international tourism.

Transport policies and national regulations can influence destinations available to tourists. One dimension concerns the openness to tourism through travel visa restrictions , which vary substantially depending on the countries of origin of tourists. Unsurprisingly, travelers from developed countries, particularly Europe, face the least restrictions, while travelers from developing countries face a much more stringent array of restrictions. Another dimension concerns the provision of infrastructure. If the public sector does not cope with the demand in terms of transport infrastructures, the tourist industry might be impaired in its development. However, land transport networks in various countries are designed to meet the needs of commercial movements that tourism requires.

Tourism usually contributes enough to the local economy that governments are more than willing to improve road networks or airport facilities, especially in locations with limited economic opportunities other than tourism. There are, however, significant differences in the amount of spending per type of mode, namely between cruise and air transport tourism. Cruise shipping tourism provides much less revenue than a tourist brought by air travel. A significant reason is that cruise lines are capturing as much tourism expenses within their ships as possible (food, beverages, entertainment, shopping) and have short port calls, often less than a day. Tourists arriving by air transport usually stay several days at the same location and use local amenities.

2. Means and Modes

Tourism uses all the standard transportation modes since travelers rely on existing passenger transport systems, from local transit systems to global air transportation.

- Car traveling is usually an independent transport conveyance where the traveler decides the route and the length of the trip. It is usually cheaper since road fees are not directly paid and provided as a public. It is the only transportation mode that does not require transfers, in the sense that the whole journey, from door to door can be achieved. Along major highway corridors, service activities such as restaurants, gas stations, and hotels have agglomerated to service the traffic, many of which touristic. Car transport is the dominant mode in world tourism (77% of all journeys), notably because of advantages such as flexibility, price, and independence. Tourists will often rent cars to journey within their destinations, which has triggered an active clustering of car rental companies adjacent to main transport terminals (airports, train stations) and touristic venues.

- Coach traveling uses the same road network as cars. Coaches are well suited for local mass tourism but can be perceived as a nuisance if in too large numbers since they require a large amount of parking space. They can be used for short duration local tours (hours) but also can be set for multi-days journeys where the coach is the conveyance moving tourists from one resort to another.

- Rail travel was the dominant form of passenger transport before the age of the automobile. The railway network usually reflects more the commercial needs of the national economy then holiday tourist flows which can make it a less preferred choice as a traveling mode. The railway systems of several countries, notably in Europe, have seen massive investments for long-distance routes and high-speed services. Due to the scenery or the amenities provided, rail transportation can also be a tourist destination in itself. Several short rail lines that no longer had commercial potential have been converted for tourism.

- Air transport is by far the most effective transport mode. Notably because of prices, only 12.5% of the tourists travel by plane, but for international travel, this share is around 40%. Air transport has revolutionized the geographical aspect of distances; the most remote areas can now be reached any journey around the world can be measured in terms of hours of traveling. Business travelers are among the biggest users of airline facilities, but low-cost air carriers have attracted a significant market segment mainly used for tourism.

- Cruises are mainly providing short sea journeys of about a week. Cruising has become a significant tourist industry. Cruise ships act as floating resorts where guests can enjoy amenities and entertainment while being transported along a chain of port calls. The international market for cruising was about 22.2 million tourists in 2015, which involves an annual growth rate above 7% since 1990. The main cruise markets are the Caribbean and the Mediterranean, with Alaska and Northern Europe fjords also popular during the summer season. This industry is characterized by a high level of market concentration with a few companies, such as Carnival Corporation and Royal Caribbean Cruises who account for about 70% of the market. The impacts of cruising on the local economy are mitigated as the strategy of cruising companies is to retain as much income as possible. This implies that tourists spend most of their money on the cruise ship itself (gift shops, entertainment, casinos, bars, etc.) or on-island facilities owned by cruise shipping companies.

3. Mass Tourism and Mass Transportation

Tourism transport can be divided into two categories:

- Independent means of travel ; controlled by individual tourists who book them on their own. This mainly involves the private automobile, but also mass conveyances that are booked to travel on an individual basis such as regularly scheduled flights, rail connections, ferries, and even cruises.

- Mass travel ; where tourists travel in organized groups. The most common form involves chartered buses and flights used for this single purpose.

When tourism was mainly for the elite, independent means of travel prevailed. However, the emergence of mass tourism and the significant revenue it provides for local economies required the setting of mass transportation systems and specialized firms such as travel agencies organizing travel on behalf of their customers. These firms were able to take advantage of their pricing power being able to negotiate large volumes of passengers for carriers and hotels. Some were even able to become air carriers, such as Thomas Cook Airlines and Air Transat, which are major charterers in their respective markets. Paradoxically, the growth of online travel booking services has favored the re-emergence of independent means of travel since an individual is able to book complex travel services, including transport and hotel accommodations. Thus, the segmentation of the travel industry is linked with the segmentation of the supporting transport systems.

The seasonality of tourism has an important impact on the use and allocation of transportation assets.

- Air transport has a notable seasonality where tourism results in variations in demand, summer being the peak season. Because of this seasonality and the high cost of acquiring additional assets to accommodate peak demand, the airline industry has pricing power during peak touristic demand. This also leads the seasonal charter services to pick up the potential unmet demand. During the winter, charterers focus on subtropical destinations (e.g. Caribbean, Mexico), while during the summer there is more a focus on the European market.

- Cruises also have a seasonality where many cruise lines are repositionning their assets according to variations in the destination preferences. During winter months, the Caribbean is an important destination market, while during the summer, destinations like the Mediterranean, Alaska, and Norway are more prevalent.

4. Covid-19 and its Impacts

Related topics.

- Air Transport

- Airport Terminals

- Transportation and Economic Development

- The Cruise Industry

Bibliography

- Graham, A. and F. Dobruszkes (eds) (2019) Air Transport – A Tourism Perspective, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- World Economic Forum (2017) The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2017, World Economic Forum.

Share this:

Tourism Transportation

The transport industry has gained a vital place in the global network system and is one of the most important components of the tourism infrastructure. It now becomes easier for people to travel from one place to another because of the various modes of transportation available.

The earliest forms of transportation in the ancient times were animals on land and sails on the sea. Travel development from the need to survive, to expand and develop trade to far off countries, and the hunger to capture new lands and territories. This was followed by the use of steams and electricity in the nineteenth century followed by internal combustion engines.

Aircraft with the jet engines were introduced in the 1950s . With the development of technology, travel became faster and more and people could travel around the globe.

Since tourism involves the movement of people from their places of residence to the places of tourist attractions, every tourist has to travel to reach the places of interest. Transport is, thus, one of the major components of the tourism industry. To develop any place of tourist attraction there have to be proper, efficient, and safe modes of transportation.

Transportation is vital to tourism. Studies have shown that tourists spend almost 30 to 40 percent of their total holiday expenditure on transportation and the remaining on food, accommodation, and other activities. This aspect once again highlights the importance of transportation.

A tourist can travel by a variety of means. The tourism professional, as well as tourist, should be aware of the various modes of transport available to reach the destination and at the destination.

The various mode of transport can be broadly divided into the following three categories :

- Air transport

- Land transport

- Water transport

Air Transport

Due to the growth of air transport in recent years, long-distance travel has become much simpler and affordable. Distance is now measured in hours and not in kilometers. The world has indeed shrunk and becomes a small village.

The development of air transport mostly occurred after World War I and II. Commercial airlines were created for travelers. Because of increasing air traffic, the commercial sector grows rapidly. Before the World War II, Swissair already was carrying around 14-16 passenger between Zurich to London.

The first commercial service was introduced by KLM, the Dutch Airlines, in 1920 between Amsterdam and London. Commercial air travel grew mostly after World War II. More facilities were introduced and there was more comfort in travel.

Jet flights were inaugurated by Great Britain in the year 1952. In the year 1958 Pan American introduced the Boeing 707 services between Paris and New York. Due to the introduction of jet flights, the year 1959 onward saw a tremendous increase in air traffic. The concept of chartered flights was also introduced during this year.

Jumbo jets have revolutionized travel. A large number of people travel by air because of the speed, comfort, and economy in terms of time saved.

The modern era, thus, is the era of mass air travel. After road transport, air travel is the most popular mode of travel, particularly for international travel. For the business travelers, air transport is more convenient as it saves their precious time and offers a luxurious and hassle-free travel. Many airlines nowadays offer special facilities to the business tourist such as Internet on board.

There two types of airlines . These are following as:

Scheduled airlines operate as regular schedules. Chartered airlines or the non-scheduled airlines operate only when there is a demand, mainly during the tourist seasons. The chartered flights work out cheaper than the scheduled carriers as they are operated only when there is a high load factor. Chartered flights provide cheaper packages to the destination such as Portugal and Spain.

India receives more than 400 chartered flights, especially to Goa. Goa has a maximum number of chartered flights coming in during the months of December to January.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) regulates international air travel. IATA has more than 105 major airlines of the world as its members. IATA regulates the price of tickets on different sectors of travel in the world. The concerned government decides the domestic fares.

The airfares are normally determined on the volume and the air travel demand in an area.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is an intergovernmental organization established in the year 1945. Only the government of the country can become a member. The government has to enter into a bilateral agreement for the frequency of flights for operating commercial airlines between them.

Airlines are classified into two broad categories namely small carrier and large carrier . The small carrier also known as commuter airlines have less than 30 seats . The larger carriers, also known as major airlines fly direct routes between the major cities and seat and seat 100 to 800 passengers .

The recent boom in the aviation technology has certainly bought some new development to airlines industry. There has been a major change in the size of the aircraft.

Every year there are a growing number of new airlines being introduced. Because of the growing number of new private airlines, there is stiff competition among them. This has resulted in a considerable reduction in air fairs and has boosted the growth of air traffic. To woo and attract customers, many airlines offer cheaper promotional fares such as excursion fares, group fares, and apex fares.

Million of tonnes of cargo and mail are also handled by the air transport industry.

Road Transport

Humans travel place to place in search of food in the primitive era. They tamed animals such as the dog, ox, horse, camel, reindeer, elephants, etc. for carrying the load and traveling. After the discovery of the wheel, humans developed the cart, the chariot, and the carriage.

Until the seventeenth century, horses were used for traveling. Later on better roads were constructed and some of these roads developed into trade routes, which linked many countries. One of them is the Silk Route which was used for transporting silk from China to Persia and the Blue Gem road from Iran to Afghanistan and India.

Today, the most popular and widely used mode of road travel is the automobile or the car. Road transport is dominated by the automobile, which provides views of the landscape and the freedom to travel. Tourist often travels with their entire family for holidays.

To promote tourism , the vehicle required are coaches and tourist cars. Tourist coaches or buses are preferred for large tourist groups traveling together on a specified tour itinerary. Many tourists prefer to travel in comfort and privacy and hire cars. Cars of various makes and standards are available on a rental basis.

Tourist also uses their own motorcar when holidaying. Cars and coaches carried long distance by train facility is also available in some countries.

The car rental segment of the tourism industry is in a very advanced stage in foreign countries. The client can book a car, himself or through agents, and make it wait at the desired place at the destination. The client can then drive the car himself /herself on reaching the destination.

Rail Transport

The railway is the most economical, convenient, and popular mode of travel especially for long distance travel all over the world. The railroad was invented in the seventeenth century in Germany with wooden tracks. The first steel rail was developed in the USA during the early 1800s . The railways revolutionized transportation and mass movement of people seen in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The broad gauge lines account for more than 55 percent of the total network and carry 85 percent of total traffic. The steam engines have been replaced by diesel and electric engines which have helped in increasing the speed. Railways have promoted tourism by introducing a special tourist train.

In Europe, the railway systems of six European countries have been clubbed to make rail travel easier for the people of Europe. A rail passenger can buy a ticket in any one country of Europe and travel through six countries. For the foreign tourists, Eurail Passes offer unlimited discounts travel in express trains for periods ranging from a week to three months. In the USA, AMTRAK operates trains.

Water Transport

Humans have been traveling through water since time immemorial and carried good and people from one place to another. The boats progressed from the simple raft with some modifications and improvement and were first used around 6000 BC.

Travel by ship was the only means for traveling overseas until the middle of the twentieth century. The Cunard Steamship Company was formed in 1838 with regular steamship services operating on the North Atlantic. During the World War I, in 1914 the operations of the steamship company had to be suspended. After the World War I, the steamship luxury liners were back to business till World War II.

After the World War II, the large luxury liners again started their operations all over the world and carried passengers and holidaymakers. Some of the linear were very large accommodating up to 1000 passengers and had facilities like swimming pools, cinema halls, shops, casino, etc.

The cruise lines are the new attraction among the tourist. The cruises are booked several months in advance for trips into the tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Hawaii, Caribbean, Mediterranean, etc. Water transport today plays two main roles in travel and tourism namely ferrying and cruising .

Modern vessels such as the wave -piercing, the hydrofoil and the hovercraft are the over the water transport and used for short distance routes.

Water transportation is also used in riverboat travel. The Mississippi River has been a popular tourist river since the first settlers came to the USA. Today, tourists enjoy two or three-day luxury trips along the river. In Europe, the Rhine, winding through the grapes growing areas of Germany, offers similar leisure tourist trips.

Motorized ferries and launches are used over rivers to transport tourists and locals, to transport vehicles, and offer facilities such as car parking, restaurants, viewing decks, etc.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Modes of Transport

Tourist has a wide variety of transport options available today. There are several advantages and disadvantages of all the model of transport. These are following as:

Direct root, high speed, quick service, social and political significance, luxurious travel are the advantages of air transportation.

High cost, jet lag, unsuitable for heavy bulk cargo, accidents always fatal, international rule to be observed are the disadvantages of air transportation.

Flexibility, reliable, door to door service, economical, supplements other modes of transport, quick transit for short distances are the advantages of road transport.

Slow speed, carrying capacity limited, accidents, none- AC coaches not so comfortable, comfort depends upon the conditions of roads are the disadvantages of road transport.

Long distance travel cheaper, carrying capacity large, dependable service, quicker than road transportation, ability to view scenery en route is the advantage of railways.

Inflexible, unfit to hilly regions, difficulties in rural areas, dining car facilities not always available are the disadvantage of railways.

Economical, carrying capacity enormously, develops international and coastal trades are the advantages of water transport.

Transportation As An Attraction

To attract customers as well as take them around an attraction, destination developers have used many forms of transport to move people around. These novel modes of transport ensure that major exhibits are viewed in a certain sequence and ensure that the crowd moves through at a reliable pace.

Overcrowding should be avoided at all costs to prevent untoward incidents and to maintain the beauty of the place. Tourist can cover the entire park in a shorter duration with the help of these modes of transport.

Transportation is the most crucial component of the tourism infrastructure. It is required not only for reaching the destination but also visiting the site and moving about at the destination. Variety in modes of transportation adds color to the overall tourism experience.

Unusual forms of transportation are also an attraction such as the cable cars in hilly terrain, the funicular railway, or jet boating. The choice of mode of transport is vast and tourists can choose a mode to suit their budget. They can opt for scheduled or non-scheduled transport such as the hiring of vehicles, boats, coaches or trains so that they can travel with their group.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2. Transportation

Morgan Westcott

Learning Objectives

- Understand the role of transportation in the tourism industry

- Recognize milestones in the development of the air industry and explain how profitability is measured in this sector

- Report on the historic importance of rail travel and challenges to rail operations today

- Describe water-based transportation segments including cruise travel and passenger ferries

- Recognize the importance of transportation infrastructure in tourism destinations

- Specify elements of sightseeing transportation, and explain current issues regarding rental vehicles and taxis

- Identify and relate industry trends and issues including fuel costs, environmental impacts, and changing weather

The transportation sector is vital to the success of our industry. Put simply, if we can’t move people from place to place — whether by air, sea, or land — we don’t have an industry. This chapter takes a broad approach, covering each segment of the transportation sector globally, nationally, and at home in British Columbia.

Let’s start our review by taking a look at the airline industry.

According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), in 2014, airlines transported 3.3 billion people across a network of almost 50,000 routes generating 58 million jobs and $2.4 trillion in business activity (International Air Transport Association, 2014a).

Spotlight On: International Air Transport Association

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) is the trade association for the world’s airlines, representing around 240 airlines or 84% of total air traffic. It supports many areas of aviation activity and helps formulate industry policy on critical aviation issues (IATA, 2014b). For more information, visit the International Air Transport Association website : http://www.iata.org

The first commercial (paid) passenger flight took place in Florida on New Year’s Day 1914 as a single person was transported across Tampa Bay (IATA 2014a). There have been a number of international aviation milestones since that flight, as illustrated in Table 2.1.

Rules and Regulations

Aviation is a highly regulated industry as it crosses many government jurisdictions. This section explores key airline regulations in more detail.

The term open skies refers to policies that allow national airlines to fly to, and above, other countries. These policies lift restrictions where countries have good relationships, freeing up the travel of passengers and goods.

Take a Closer Look: The 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation

This document contains the original statements from the convention that created the airline industry as we know it, providing a preamble statement as well as detailed articles pertaining to a range of issues from cabotage to pilotless aircraft. Read the 1944 Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation [PDF] : www.icao.int/publications/Documents/7300_orig.pdf

Canada’s approach to open skies is the Blue Sky Policy , first implemented in 2006. The National Airlines Council of Canada (NACC) and Canadian Airports Council (CAC) support the Blue Sky Policy.

While opening up a ir transport agreements (ATAs) with other jurisdictions is important, the Canadian government doesn’t provide blanket arrangements, instead negotiating “when it is in Canada’s overall interest to do so” (Government of Canada, 2014a). Some su ggest the government should be more liberal with air access so more competitors can enter the market, potentially attracting more visitors to the country (Gill and Raynor, 2003).

Taxes and Fees

According to a 2012 Senate study on issues related to the Canadian airline industry, Canadian travellers are being grounded by airline fees, fuel surcharges, security taxes, airport improvement fees, and other additional costs. Airports are charged rental fees by the Canadian government ($4.8 billion from 1992 to 2004), which they pass on to the airlines, who in turn transfer the costs to travellers. Some think eliminating rental fees would make Canadian airports more competitive, and view rental and other fees as the reason 5 million Canadians went south of the border for flights in 2013, where passenger fees are 230% lower than in Canada (Hermiston and Steele, 2014).

Profitability

Running an airline is like having a baby: fun to conceive, but hell to deliver. – C. E. Woolman, principal founder of Delta Air Lines ( The Economist , 2011).

As the quote above suggests, airlines are faced with many challenges. In addition to operating in a strict regulatory environment, airlines yield extremely small profit margins. In 2013 the industry accumulated $10.6 billion worldwide in revenues, although global profit margins were just 1.5% (IATA, 2014a). To put that into perspective, while the average airline earned 1.5%, Apple’s profit margins were almost 14 times that at 20.15% (YCharts, 2014).

Passenger Load Factor

Key to airline profitability is passenger load factor , which relates how efficiently planes are being used. Load factor for a single flight can be determined by dividing the number of passengers by the number of seats.

Passenger load factors in the airline industry reached a record high in 2013, at just under 80%, which was attributed to increased volumes and strong capacity management in key sectors (IATA, 2104a). One way of increasing capacity is by using larger aircraft. For instance, the introduction of the Airbus A380 model has allowed up to 40% more capacity per flight, carrying up to 525 passengers in a three-class configuration, and up to 853 in a single-class configuration (Airbus, 2014).

Low-Cost Carriers

Another key factor in profitability is the airline’s business model. In 1971, Southwest Airlines became the first low-cost carrier (LCC), revolutionizing the industry. The LCC model involved charging for all extras such as reserved seating, baggage, and on-board service, and cutting costs by offering less legroom and using non-unionized workforces. Typically, an LCC has to run with 90% full planes to break even (Owram, 2014). The high-volume, lower-service system is what we have become used to today, but at the time it was introduced, it was groundbreaking.

Ancillary Revenues

The LCC model, combined with tight margins, led to today’s climate where passengers are charged for value-added services such as meals, headsets, blankets, seat selection, and bag checking. These are known in the industry as ancillary revenues . Profits from these extras rose from $36 billion in 2012 to $42 billion in 2013, or more than $13 a passenger. An average net profit of only $3.39 per passenger was retained by airlines (IATA, 2014a).

As you can see, airlines must strive to maintain profitability, despite thin margins, in an environment with heavy government regulation. But at the same time, they must be responsible for the safety of their passengers.

Air Safety and Security

IATA encourages airlines to view safety from a number of points, including reducing operational risks such as plane crashes, by running safety audit programs. They also advocate for improved infrastructure such as runway upgrades and training for pilots and other crew. Finally, they strive to understand emerging safety issues, including the outsourcing of operations to third-party companies (IATA, 2014a).

In terms of security, coordination between programs such as the Interpol Stolen and Lost Travel Documents initiative and other databases is critical (IATA, 2014a). As reservations and management systems become increasingly computerized, cyber-security becomes a top concern for airlines, who must protect IT (information technology) because their databases contain information about flights and passengers’ personal information. Unruly passengers are also a cause of concern, with over 8,000 incidents reported worldwide every year (IATA, 2014a).

Now that we have a better sense of the complexities of the industry, let’s take a closer look at air travel in Canada and the regional air industry.

Canada’s Air Industry

In 1937, Trans-Canada Air Lines (later to become Air Canada) was launched with two passenger planes and one mail plane. By the 1950s, Canadian Pacific Airlines (CP Air) entered the marketplace, and an economic boom led to more affordable tickets. Around this time CP Air (which became Canadian Airlines in 1987) launched flights to Australia, Japan, and South America (Canadian Geographic, 2000). In 2001, Canadian Airlines International was acquired by Air Canada (Aviation Safety Network, 2012).

In 1996, the marketplace changed drastically with the entry of an Alberta-based LCC called WestJet. By 2014, WestJet had grown to become Canada’s second major airline with more than 9,700 staff flying to 88 destinations across domestic and international networks (WestJet, 2014).

As it grew, WestJet began to offer services such as premium economy class and a frequent-flyer program, launched a regional carrier, and introduced transatlantic flights with service to Dublin, Ireland, evolving away from the LCC model (Owram, 2014). With those changes, and in the absence of a true low-cost carrier, in 2014, some other companies, such as Canada Jetlines and JetNaked, sought to raise upward of $50 million to bring their airlines to market.

However, outside of Air Canada and WestJet, airlines in Canada have found it very challenging to survive, and some examples of LCC startups like Harmony Airways and Jetsgo have fallen by the wayside.

Challenges to Canada’s Air Industry

When looking at these failed airlines in Canada, three key challenges to success can be identified (Owram, 2014):

- Canada’s large geographical size and sparse population mean relatively low demand for flights.

- Canada’s higher taxes and fees compared with other jurisdictions (such as the United States) make pricing less competitive.

- Canada’s two dominant airlines are able to price new entrants out of the market.

In addition to these factors, the European debt crisis, a slow US economic recovery, more cautious spending by Canadians, and fuel price increases led to a $900 million industry loss in 2011 (Conference Board of Canada, 2012) prior to the industry returning to profitability in 2013.

Take a Closer Look: One Size Doesn’t Fit All

In 2013, a special report to the Canadian Senate explored the concept that one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to competitiveness in the country’s airline industry. The report contains general observations about the industry as well as a number of recommendations to stakeholders, including airport managers. Read the report: “One Size Doesn’t Fit All: the Future Growth and Competitiveness of Canadian Air Travel” [PDF] : www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/411/trcm/rep/rep08apr13-e.pdf

Today, the Canadian airline industry directly employs roughly 141,000 people and is worth $34.9 billion in gross domestic product. It supports 330 jobs for every 100,000 passengers and contributes over $12 billion to federal and provincial treasuries, including over $7 billion in taxes (Gill and Raynor, 2013).

Let’s now turn our attention to the regional air market, focusing on British Columbia.

Regional Airlines

Transportation in BC has always been difficult: incomplete road systems and rugged terrain historically made travel between communities almost impossible. In 1927, a number of businessmen promised to change all that when they opened British Columbia Airways in Victoria with the purchase of a commercial airliner (Canadian Museum of Flight, 2014).

As commercial flying became more popular, and the province grew, regional airports started to spring up around BC as a means of delivering surveying equipment, forestry supplies, and workers. Many of these airports were legacies of Canada’s strategic position for the military. Fort Nelson’s airport, for instance, was established so the US Air Force could fuel aircraft bound for Russia in World War II (Northern Rockies Regional Airport, 2014).

In 1994, Transport Canada transferred all 150 airports under its control to local authorities under the National Airports Policy (NAP). This policy is considered to have been a turning point in the privatization of the airline industry in Canada. A 2004 study showed that after 10 years, 48% of these airports were not able to cover annual costs of operation, leading to concerns about the viability of small local airports in particular (InterVISTAS, 2005).

In 2012, the BC government released its aviation strategy, entitled Connecting with the World , which acknowledged the economic challenges for airports large and small. These range from Vancouver International Airport (YVR), which supports more than 61,000 jobs and creates more than $11 billion in economic activity each year, through to regional and local airports. The strategy outlined a framework to remove barriers to aviation growth including potentially eliminating the two-cent-per-litre International Aviation Fuel Tax ( British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure , 2012).

Given a highly complex regulatory environment, razor-thin profit margins, and intense competition, the airline industry is constantly changing and evolving at global, national, and regional levels. But one thing is certain: air travel is here to stay.

On the other hand, the rail industry has been faced with significant declines since air travel became accessible to the masses. Let’s learn more about this sector.

In Chapter 1, we looked at the historic significance of railways as they laid the foundation for the modern tourism industry. That’s because in many places, including Canada and British Columbia, trains were an unprecedented way to move people across vast expanses of land. With the Canadian Pacific company opening up hotels in major cities, BC’s hospitality sector was born and a golden age of rail travel emerged.

However, starting in the 1940s and 1950s, the passenger rail industry began to decline sharply. In 1945, Canadian railways carried 55.4 million passengers, but just 10 years later passenger traffic had dropped to 27.2 million. The creation of VIA Rail in 1977 as a Canadian Crown corporation was an attempt by the government to ensure rail travel did not disappear, but in the years since its founding VIA has struggled, relying heavily on federal subsidies in order to continue operations.

Between 1989 and 1990, VIA lost over 45% of its ridership when it cut unprofitable routes, focusing on areas with better potential for revenue and passenger volumes. From there, annual ridership has stabilized at around 3.5 million to 4.0 million passengers per year, slowly increasing throughout the 1990s and 2000s (Dupuis, 2011).

Despite this slight recovery, there are a number of challenges for passenger rail in Canada, which will likely require continued government support to survive. Three key challenges to a successful passenger rail industry are:

- Passenger rail must negotiate with freight for right-of-use of tracks.

- There is limited potential of routes (with the highest volume existing in the Quebec-Windsor corridor).

- Fixed-cost equipment is aging out, requiring replacement or upgrading.

High-speed rail seems like an attractive option, but would be expensive to construct as existing tracks aren’t suitable for the reasons given above. It’s also unlikely to provide high enough returns to private investors (Dupuis, 2011). This means the Canadian government would have to invest heavily in a rapid rail project for it to proceed. As of 2014, no such investment was planned.

Spotlight On: Rocky Mountaineer Rail Tours

Founded in 1990, Rocky Mountaineer offers three train journeys through BC and Alberta to Banff, Lake Louise, Jasper, and Calgary, and one train excursion from Vancouver to Whistler. In 2013, Rocky Mountaineer introduced Coastal Passage, a new route connecting Seattle to the Canadian Rockies that can be added to any two-day or more rail journey (Rocky Mountaineer, 2014). For more information, please visit the Rocky Mountaineer website : http://www.rockymountaineer.com

While the industry overall has been in a decline, touring companies like Rocky Mountaineer have found a financially successful model by shifting the focus from transportation to the sightseeing experience. The company has weathered financial storms by refusing to discount their luxury product, instead focusing on the unique experiences. The long planning cycle for scenic rail packages has helped the company stand their ground in terms of pricing (Cubbon, 2010).

Rail Safety

In Canada, rail safety is governed by the Railway Safety Act , which ensures safe railway operation and amends other laws that relate to rail safety (Government of Canada, 2014b). The Act is overseen by the Minister of Transport. It covers grade crossings, mining and construction near railways, operating certifications, financial penalties for infractions, and safety management.

The Act was revised in late 2014 in response to the massive rail accident in July 2013 in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec. A runaway oil train exploded, killing 47 people, and subsequently MM&A Railway and three employees, including the train’s engineer, were charged with criminal negligence (CBC News, 2014).

In addition to freight management issues, a key rail safety concern is that of crossings. As recently as April 2014, Transport Canada had to issue orders for improved safety measures at crossings in suburban Ottawa after a signal malfunctioned in the area (CTV News, 2014a). According to Operation Lifesaver Canada (2014), in 2011, there were 169 crossing collisions across Canada, with 25 fatalities and 21 serious injuries. In general, however, Canada’s 73,000 kilometres of railway tracks safely transport both people and goods. And while railways in Canada, and elsewhere, are being forced to innovate, companies like Rocky Mountaineer (see Spotlight On above) give the industry glimmers of hope.

The rail industry shares some common history with the cruise sector. Let’s now turn our focus to the water and learn about the evolution of travel on the high seas.

Travel by water is as old as civilization itself. However, the industry as we know it began when Thomas Newcomen invented the steam engine in 1712. The first crossing of the Atlantic by steam engine took place in 1819 aboard the SS Savannah , landing in Liverpool, England, after 29 days at sea. Forty years later, White Star Lines began building ocean liners including the Olympic -class ships (the Olympic, Britannic , and Titanic ), expanding on previously utilitarian models by adding luxurious amenities (Briggs, 2008).

A boom in passenger ship travel toward the end of the 1800s was aided by a growing influx of immigrants from Europe to America, while more affluent passengers travelled by steamship for pleasure or business. The industry grew over time but, like rail travel, began to decline after the arrival of airlines. Shipping companies were forced to change their business model from pure transportation to “an experience,” and the modern cruise industry was born.

The Cruise Sector

We’ve come a long way since the Olympic class of steamship. Today, the world’s largest cruise ship, MS Oasis of the Seas , has an outdoor park with 12,000 plants, an 82-foot zip wire, and a high-diving performance venue. It’s 20 storeys tall and can hold 5,400 passengers and a crew of up to 2,394 (Magrath, 2014). A crew on a cruise ship will include the captain, the chief officer (in charge of training and maintenance), staff captain, chief engineer, chief medical officer, and chief radio officer (communication, radar, and weather monitoring).

Spotlight On: Cruise Lines International Association

Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) is the world’s largest cruise industry trade association with representation in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australasia. CLIA represents the interests of cruise lines and travel agents in the development of policy. CLIA is also engaged in travel agent training, research, and marketing communications (CLIA, 2014). For more information on CLIA, the cruise industry, and member cruise lines and travel agencies, visit the Cruise Lines International Association website : www.cruising.org

Cruising the World

According to CLIA, 21.7 million passengers were expected to travel worldwide on 63 member lines in 2014. Given increased demand, 24 new ships were expected in 2014-15, adding a total capacity of over 37,000 passengers.

Over 55% of the world’s cruise passengers are from North America, and the leading destinations (based on ship deployments), according to CLIA, are:

- The Caribbean (37%)

- The Mediterranean (19%)

- Northern Europe (11%)

- Australia/New Zealand (6%)

- Alaska (5%)

- South America (3%)

River Cruising

While mass cruises to destinations like the Caribbean remain incredibly popular, river cruises are emerging as another strong segment of the industry. The key differences between river cruises and ocean cruises are (Hill, 2013):

- River cruise ships are smaller (400 feet long by 40 feet wide on average) and can navigate narrow passages.

- River cruises carry fewer passengers (about 10% of the average cruise, or 200 passengers total).

- Beer, wine, and high-end cuisine are generally offered in the standard package.

The price point for river cruises is around the same as ocean trips, with the typical cost ranging from $2,000 to $4,000, depending on the itinerary, accommodations, and other amenities.

From 2008 to 2013, river cruises saw a 10% annual passenger increase. Europe leads the subcategory, while emerging destinations include a cruise route along China’s Yangtze River. As the on-board experience differs greatly from a larger cruise (no play areas, water parks, or on-board stage productions), the target demographic for river cruises is 50- to 70-year-olds. According to Torstein Hagen, founder and chairman of Viking, an international river cruising company, “with river cruises, a destination is the destination,” although many river cruises are themed around cultural or historical events (Hill, 2013).

Cruising in Canada

According to a study completed for the North West & Canada Cruise Association (NWCCA) and its partners, in 2012, approximately 1,100 cruise ship calls were made at Canadian cruise ports generating slightly more than 2 million passenger arrivals throughout the six-month cruise season (BREA, 2013). The study found three key cruise itineraries in Canada:

- Canada/New England

- Quebec (between Montreal and Quebec City and US ports)

- Alaska (either departing from, or using, Vancouver or another BC city as a port of call)

These generated $1.16 billion in direct spending. Cruising also generated almost 10,000 full- and part-time jobs paying $397 million in wages and salaries. The international cruise industry also generated an estimated $269 million in indirect business and income taxes in Canada, and the majority of this spending was in British Columbia (BREA, 2013).

Cruising BC

BC’s rail history and cruise history are intertwined. As early as 1887, Canadian Pacific Railway began offering steamship passage to destinations such as Hawaii, Shanghai, Alaska, and Seattle. Ninety-nine years later, Vancouver’s Canada Place was built, with its cruise ship terminals, allowing the province to attract large ships and capture its share of the growing international cruise industry (Cruise BC, 2014).

Spotlight On: Cruise BC

Cruise BC is a partnership between BC port destinations designed to provide a vehicle for cooperative marketing and development of BC’s cruise sector. Their vision is that the West Coast and British Columbia’s coastal communities are recognized and sought out globally by cruise lines and passengers as a destination of choice. For more information, visit the Cruise BC website : http://www.cruisebc.ca

This potential continues to grow as Nanaimo, Prince Rupert, Victoria, and Vancouver accounted for 57% of the Canadian cruise passenger traffic with 1.18 million passengers in 2012 (BREA, 2013).

Cruising isn’t the only way for visitors to experience the waters of BC. In fact, the vast majority of our water travel is done by ferry. Let’s take a closer look at this vital component of BC’s transportation infrastructure.

Ferry service in British Columbia dates back to the mid-1800s when the Hudson’s Bay Company ran ships between Vancouver Island and the Mainland. Later, CP Rail and Black Ball ferries ran a private service, until 1958 when Premier W.A.C. Bennett announced the BC Ferry Authority would consolidate the ferries under a provincial mandate.

The MV Tsawwassen and the MV Sidney began regular service on June 15, 1960, and BC Ferries was officially launched with two terminals and around 200 employees. Today, there are 35 vessels, 47 destinations, and up to 4,700 employees in the summer peak season (BC Ferries, 2014).

BC isn’t the only destination where ferries make up part of the transportation experience. In 2011, Travel + Leisure Magazine profiled several notable ferry journeys in the article, “World’s Most Beautiful Ferry Rides” including:

- An 800-mile ferry voyage through Chile’s Patagonian fjords

- A three-mile trip from the Egyptian Spice Market to Istanbul, Turkey

- Urban ferry rides including Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour, Australia’s Sydney Harbour, and New York City’s Staten Island Ferry

The article also featured the 15-hour trip from Port Hardy to Prince Rupert on British Columbia’s coast (Orcutt, 2011).

While cruising is often a pleasant and relaxing experience, there are a number of safety concerns for vessels of all types.

Cruise and Ferry Safety

One of the major concerns on cruise lines is disease outbreak, specifically the norovirus (a stomach flu), which can spread quickly on cruise ships as passengers are so close together. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) vessel sanitation program (http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/vsp/default.htm) is designed to help the industry prevent and control the outset, and spreading, of these types of illnesses (Briggs, 2008).

Accidents are also a concern. In 2006, the BC Ferries vessel MV Queen of the North crashed and sank in the Inside Passage, leaving two passengers missing and presumed dead. The ship’s navigating officer was charged with criminal negligence causing their deaths (Keller, 2013). More recently, a “hard landing” at Duke Point terminal on Vancouver Island caused over $4 million in damage. BC Ferries launched a suit against a German engineering firm in late 2013, alleging a piece of equipment failed, making a smooth docking impossible. The Transportation Safety Board found that staff aboard the ship didn’t follow proper docking procedures, however, which contributed to the crash (Canadian Press, 2013).

Spotlight On: The Transportation Safety Board

The Transportation Safety Board (TSB) investigates marine, pipeline, rail, and air incidents. It is an independent agency that reviews an average of 3,200 events every year. It does not determine liability; however, coroners and medical examiners may use TSB findings in their investigations. The head office in Quebec manages 220 staff across the country. For more information, visit the Transportation Safety Board website : http://www.bst-tsb.gc.ca/eng/index.asp

We’ve covered the skies, the rails, and the seas. Now let’s round out our investigation of transportation in tourism by delving into travel on land.

While much of this text has placed significance on the emergence of the railways as critical to the development of our industry, BC’s roadways have also played an integral role. Our roads have evolved from First Nations trails, to Fur Trade and Gold Rush routes, to Wagon Roads and Trunk Roads — finally becoming the highway system we know today ( British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Highways , n.d.).

Take a Closer Look: Frontier to Freeway: A Short Illustrated History of the Roads in British Columbia

This short book, available as a PDF, provides an overview of the integral importance of BC’s evolving roadways in our transportation sector. Read this book: Frontier to Freeway: A Short Illustrated History of the Roads in British Columbia [PDF] : http://www.th.gov.bc.ca/publications/frontiertofreeway/frontiertofreeway.pdf

Today, land-based travel is achieved through a complex web of local transit, taxis, rentals, walking, and short-term sightseeing. This section briefly explores these options.

Scenic and Sightseeing Travel

It’s common for visitors to want to explore a community and appreciate the sights. We’ve already learned a little about the rail-based sightseeing company, Rocky Mountaineer. Many destinations also offer short-term, hop-on-hop-off bus and trolley tours. Others feature trams and trolleys. Outside of impromptu excursions, sightseeing tours are often put together by inbound tour operators. You can learn more about tour operators, and the sightseeing sector, in Chapter 7.

Transit and Destination Infrastructure

Vancouver’s Tourism Master Plan acknowledges the importance of transportation infrastructure to the tourism industry. Priorities for future development by the city include (Tourism Vancouver, 2013):

- Improving accessibility for people with disabilities

- Creating a transit loop between downtown attractions

- Supporting ferries in False Creek

- Providing late-night transit

- Investigating and implementing a public bike share

- Developing more transit options along the Broadway corridor

- Working with taxi companies to explore a strategic plan for taxi operations

- Enhancing walkability by implementing recommendations from the Pedestrian Safety Study and Action Plan

These action items were developed in consultation with industry stakeholders as well as residents, and reflect the interrelated elements that make up a destination’s transportation infrastructure.

Rentals and Taxis

Today, when travellers aren’t using their own cars, automobile travel is traditionally split between rental vehicles and taxis (including limousines).

In North America, there are three main brands that represent approximately 85% of the rental car business: Enterprise (includes National and Alamo), Hertz (includes Dollar and Thrifty), and Avis. One of the reasons that brands have consolidated over time is the high fixed cost of operation as vehicles are purchased, maintained, and disposed of. Fierce competition means prices are checked and updated thousands of times a day. The business is also highly seasonal, with high traffic in summer and spring, and so fleet management is critical for profitability. Rental companies tend to use enplanements (the numbers of passengers travelling by air), as a measurement of market trends that influence rental usage (DBRS, 2010).

In BC, taxi licences are issued by the BC Passenger Transportation Board. In Vancouver, the right to operate a taxi is based on a permit system, and each permit costs the original holder $100. But because of the limited number of permits available, those who hold one are able to auction it off for over $800,000 and keep the profit. As a result, passengers in Vancouver paid an average of 73% more for the equivalent trip in Washington, D.C. Drivers from areas outside the city depositing passengers in Vancouver are also not permitted to pick up fares on the return trip, having to drive across their boundaries (Proctor, 2014).

Ridesharing apps like Uber, which allow people to find a ride using their mobile phone, have emerged to exert influence on car travel in key destinations. In San Francisco, these apps have rapidly undercut the taxi industry: according to the city’s transit authority, per month, trips by taxi have plummeted from 1,424 in 2012 to 504 in 2014, even though taxi operators maintain a monopoly over rides from the airport (Kuittinen, 2014). In New York City, however, the price of medallions (similar to Vancouver’s taxi permits) continues to hover above $950,000. In large markets like Manhattan, passengers continue to hail cabs on the street in the moment, with e-hails (electronic taxi hails) at 0.17% of the market (Brustein & Winter, 2014). The City of Vancouver opted to force Uber to roll back after its initial release, and in 2014 placed the app on a six-month moratorium after pressure from taxi operators who cited threats to the values of their licences as well as safety and monitoring concerns (CTV News, 2014b).

As this and other examples illustrate, the transportation sector is vulnerable to regulatory, technological, operational, and business trends. Let’s look at these in more detail.

Trends and Issues

This section explores issues directly relating to transportation today including fuel cost, labour, and environmental impacts. For more information on one of the biggest trends in tourism, online travel agencies (OTAs), and how online bookings impact the transportation sector, please see Chapter 7.

When it comes to moving people, fuel cost is critical. The cost of jet fuel is one of the single highest factors in airline profitability. In 2013, the average cost was around $125 per barrel, which was $5 less than the previous year (IATA, 2014a). Cruise ships consume a lower grade of diesel than do land vehicles, but they consume a lot of it. The QE2 , for example, consumes roughly 380 tonnes of fuel every day if travelling at 28.5 knots (Briggs, 2008).

As in all tourism-related sectors, cyclical labour shortages can significantly impact the transportation industry. In the aviation sector, a forecast found that by 2032 the world’s airlines will need 460,000 additional pilots and 650,000 new maintenance technicians to service current and future aircraft. The drive to find employees also extends to the maritime sector, where the International Maritime Organization (IMO) launched a “Go to sea!” campaign to attract more workers to the field (PWC, 2012).

Environmental Impacts

In addition to fuel and labour costs, and regulations we’ve covered already, the transportation sector has a significant impact on the natural environment.

Air Impacts

According to the David Suzuki Foundation (2014), the aviation industry is responsible for 4% to 9% of climate change impacts, and greenhouse gas emissions from flights have risen 83% since 1990. Airline travel has a greater emissions impact than driving or taking the train per passenger kilometre, which caused a bishop in the UK to famously declare that “Making selfish choices such as flying on holiday [is] a symptom of sin” (Barrow, 2006).

Rail Impacts

Rail travel is widely regarded as one of the most environmentally friendly modes of transportation due to its low carbon dioxide emissions. Railways come under fire outside of the tourism realm, however, as freight shipping can produce hazards to resident health including an increased risk of developing cancer and noise pollution (The Impact Project, 2012).

Cruise Impacts

Cruise ships can generate significant pollution from black water (containing human waste), grey water (runoff from showers, dishwashers, sinks), bilge water (from the lowest compartment of the ship), solid waste (trash), and chemical waste (cleaners, solvents, oil). One ship can create almost a million litres of grey water, over 113,000 litres of black water, and over 140,000 litres of bilge water every day. Depending on the regulations in the operating areas, ships can simply dump this waste directly into the ocean. Ballast tanks, filled to keep the ship afloat, can be contaminated with species which are then transported to other areas, disrupting sensitive ecosystems (Briggs, 2008).

Land Impacts

A recent study found that the impact of travel on land is highly dependent on the number of passengers. Whereas travelling alone in a large SUV can have high emissions per person (as high as flying), increasing the number of passengers, and using a smaller vehicle, can bring the impact down to that of train travel ( Science Daily , 2013).

For more information on the environmental impacts of the transportation sector, and how to mitigate these, read Chapter 10.

As you’ve learned, the transportation sector can have an effect on climate change, and changes in weather have a strong effect on transportation. According to Natural Resources Canada (2013), some of these include:

- More drastic freeze-thaw cycles, destroying pavement and causing ruts in asphalt

- Increased precipitation causing landslides, washing out roads, and derailing trains

- Effects and costs of additional de-icing chemicals deployed on aircraft and runways (over 50 million litres were used worldwide in 2013)

- Delayed flights and sailings due to increased storm activity

- Millions of dollars of infrastructure upgrades required as sea levels increase and flood structures (replacing or relocating bridges, tunnels, ports, docks, dykes, helipads and airports)

The threat of climate change could significantly impact sea-level airports such as YVR, and some 50 additional registered airports across Canada that sit at five metres or less above sea level (Natural Resources Canada, 2013).

For this reason, it’s important that the sector continue to press for innovations and greener transportation choices, if only to ensure future financial costs are kept at bay.

Tourism, freight, and resource industries such as forestry and mining sometimes compete for highways, waterways, and airways. It’s important for governments to engage with various stakeholders and attempt to juggle various economic priorities — and for tourism to be at the table during these discussions.

That’s why in 2015 the BC Ministry of Transportation released its 10-year plan, BC on the Move . Groups like the Tourism Industry Association of BC actively polled their members in order to have their concerns incorporated into the plan. These included highway signage and wayfaring, the future of BC Ferries, and urban infrastructure improvements.

You can view the plan by visiting http://engage.gov.bc.ca/transportationplan/

This chapter has taken a brief look at one of the most complex, and vital, components of our industry. Chapter 3 covers accommodations and is just as essential.

- Ancillary revenues: money earned on non-essential components of the transportation experience including headsets, blankets, and meals

- Blue Sky Policy: Canada’s approach to open skies agreements that govern which countries’ airlines are allowed to fly to, and from, Canadian destinations

- Cruise BC: a multi-stakeholder organization responsible for the development and marketing of British Columbia as a cruise destination

- Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA): the world’s largest cruise industry trade association with representation in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australasia

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) : the trade association for the world’s airlines

- Low-cost carrier (LCC): an airline that competes on price, cutting amenities and striving for volume to achieve a profit

- National Airports Policy (NAP): the 1994 policy that saw transfer of 150 airports from federal control to communities and other local agencies, essentially deregulating the industry

- Open skies: a set of policies that enable commercial airlines to fly in and out of other countries

- Passenger load factor: a way of measuring how efficiently a transportation company uses its vehicles on any given day, calculated for a single flight by dividing the number of passengers by the number of seats

- Railway Safety Act: a 1985 Act to ensure the safe operation of railways in Canada

- Ridesharing apps: applications for mobile devices that allow users to share rides with strangers, undercutting the taxi industry

- Transportation Safety Board (TSB): the national independent agency that investigates an average of 3,200 transportation safety incidents across the country every year

- When did the first paid air passenger take flight? What would you say have been the three biggest milestones in commercial aviation since that date?

- If a flight with 500 available seats carries 300 passengers, what is the passenger load factor?

- Why is it difficult for new airlines to take off in Canada?

- How did some of BC’s regional airports come into existence? What are some of the challenges they face today?

- How much economic activity is generated by YVR every year?

- What are the key differences between river cruises and ocean cruises? Who are the target markets for these cruises?

- Which cities attract more than 50% of the cruise traffic in Canada?

- What are the priorities for transportation infrastructure development as outlined in Vancouver’s Tourism Master Plan? What other transportation components would you include in your community’s tourism plan?

- What are some of the environmental impacts of the transportation sector? Name three. How might these be lessened?

Case Study: Air North

Founded in 1977 by Joseph Sparling and Tom Wood, Air North is a regional airline providing passenger and cargo service between Yukon and destinations including BC, Alberta, and Alaska. In 2012, Air North surpassed one million passengers carried. Employing over 200 people, the airline is owned in significant part by the Vuntut Development Corporation, the economic arm of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation (VGFN). In fact, one in 15 Yukoners owns a stake in the airline (Air North, 2015).

The ownership model has meant that economic returns are not always the priority for shareholders. As stated on its website, “ the maximization of profit is not the number one priority,” as air service is a “lifeline” to the VGFN community. For this reason, service and pricing of flights is extremely important, as are employment opportunities.

Visit the corporate information portion of the Air North website and answer the following questions: http://www.flyairnorth.com/Experience/about-air-north.aspx

- What is the number one priority of Air North? How is the company structured to ensure it can meet its goals in this area?

- What does Air North consider to be its competitive advantage? How does this differ from other airlines?

- Describe the investment portfolio of the Vuntut Development Corporation. What types of companies does it own? Why might they have selected these types of initiatives?

- List at least three groups that have a stake in the airline. What are their interests? Where do their interests line up, and where do they compete?

- In your opinion, would this regional airline model work in your community? Why or why not?

Air North. (2015). Corporate information . Retrieved from www.flyairnorth.com/Experience/Corporate.aspx

Airbus. (2014). A380: Boost your profitability. Retrieved from http://www.airbus.com/aircraftfamilies/passengeraircraft/a380family/

Aviation Safety Network. (2012, March 4). Canadian Airlines International . Retrieved from http://aviation-safety.net/database/operator/airline.php?var=7022

Barrow, Becky. (2006, July 23). Flying on holiday ‘a sin’, says bishop. Daily Mail Online . Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-397228/Flying-holiday-sin-says-bishop.html

BC Ferries. (2014, June 17). BC Ferries proudly celebrates 50 sears of Service . Retrieved from http://www.bcferries.com/about/history/history.html

BREA. (2013, March). The economic contribution of the international cruise industry in Canada 2012 . Prepared for: North West & Canada Cruise Association, St. Lawrence Cruise Association, Atlantic Canada Cruise Association, Cruise BC. Exton, PA: Business Research & Economic Advisors, p. 1-5.

Briggs, Josh. (2008, May 1). How cruise ships work . Retrieved from http://adventure.howstuffworks.com/cruise-ship.htm

British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Highways. (n.d.). Frontier to freeway: A short illustrated history of the roads in British Columbia. [PDF] Retrieved from http://www.th.gov.bc.ca/publications/frontiertofreeway/frontiertofreeway.pdf

British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure. (2012). Connecting with the world: An aviation strategy for British Columbia [PDF] . Retrieved from http://www.th.gov.bc.ca/airports/documents/2012_AviationStrategy.pdf

Brustein, Joshua and Caroline Winter. (2014, February 28). If Uber is killing taxis, what explains the million-dollar medallions. Business Week . Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-02-28/if-uber-is-killing-taxis-what-explains-new-yorks-million-dollar-medallions

Canadian Geographic . (September/October 2000). Canadian aviation history. Retrieved from http://www.canadiangeographic.ca/magazine/so00/aviation_history.asp

Canadian Museum of Flight. (2014). The history of flight in BC . Retrieved from http://www.canadianflight.org/content/history-flight-bc-0

Canadian Press. (2013, December 12). BC Ferries crash lawsuit targets electronics firm. Huffpost British Columbia . Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/12/22/bc-ferries-crash-lawsuit_n_4490818.html

CBC News. (2014, May 12.) MM&A Railway faces charges in Lac-Megantic disaster – Montreal – CBC News . Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/mm-a-railway-faces-charges-in-lac-mégantic-disaster-1.2640654

CLIA. (2014, January 16). The state of the cruise industry in 2014: Global growth in passenger numbers and product offerings . Retrieved from http://www.cruising.org/regulatory/news/press_releases/2014/01/state-cruise-industry-2014-global-growth-passenger-numbers-and-product-o

Conference Board of Canada. (2012, September 13). Canada’s airlines hoping to return to the black in 2013. Retrieved from http://www.conferenceboard.ca/press/newsrelease/12-09-14/canada_s_airlines_hoping_to_return_to_the_black_in_2013.aspx

Cruise BC. (2014). Cruise BC, Canada – Cruise executives . Retrieved from http://www.cruisebc.ca/index.php?page=5

CTV News. (2014a). Feds order Via Rail to address ‘safety’ issues at 6 Ottawa railway crossings . Retrieved from http://www.ctvnews.ca/business/feds-order-via-rail-to-address-safety-issues-at-6-ottawa-railway-crossings-1.1771156

CTV News. (2014b, October 1). Vancouver delays Uber, new cabs for six months. Retrieved from http://bc.ctvnews.ca/vancouver-delays-uber-new-cabs-for-six-months-1.2034892

Cubbon, Paul. (2010, October 22). Rocky economy can’t derail train company. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/small-business/rocky-economy-cant-derail-train-company/article1241050/

David Suzuki Foundation. (2014). Air travel and climate change. Retrieved from http://www.davidsuzuki.org/issues/climate-change/science/climate-change-basics/air-travel-and-climate-change/

DBRS. (2010, May). Rating Canadian rental car securitizations . Retrieved from http://www.dbrs.com/research/232631

Dupuis, Jean. (2011, November 16). VIA Rail Canada Inc. and the future of passenger rail in Canada . Ottawa, ON: Library of Parliament. Retrieved from http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/2011-93-e.htm#a8

Economist, The . (2011, December 22). Business quotations: Our favourite air lines . Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/gulliver/2011/12/business-quotations

Gill, Vijay and R. Neil Raynor. (2013, September). Growing Canada’s economy: A new national air transportation policy . Ottawa, ON: Conference Board of Canada, p. i -4.

Government of Canada. (2014a, June 5). The Blue Sky Policy: Made in Canada, for Canada – Transport Canada . Retrieved from http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/policy/air-bluesky-menu-2989.htm

Government of Canada. (2014b, September 3). Railway Safety Act (1985, c. 32 (4th Supp.)) – Transport Canada . Retrieved from https://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/acts-regulations/acts-1985s4-32.htm

Hermiston, Sandra and Lynda Steele (2014, August 5). Why it costs so much more to fly in Canada. CTV Vancouver News . Retrieved from http://bc.ctvnews.ca/why-it-costs-so-much-more-to-fly-in-canada-1.1733387

Hill, Catey. (2013, February 1). W hat’s behind the river-cruise boom. Marketwatch . Retrieved from http://www.marketwatch.com/story/whats-behind-the-river-cruise-boom-2013-02-01

IATA. (2014a, June). IATA annual review 2014. Retrieved from http://www.iata.org/2014-review/reader.html?r=29/569#

IATA. (2014b). IATA-About us. Retrieved from http://www.iata.org/about/pages/index.aspx

Impact Project. (2012, January 20). Tracking harm: Health and environmental impacts of rail yards. The Impact Project Policy Brief Series. [PDF] Retrieved from http://hydra.usc.edu/scehsc/pdfs/Rail%20issue%20brief.%20January%202012.pdf

InterVISTAS. (2005, April). BC regional airports: A policy guide to viability . [PDF] Prepared for AIM/Council of Tourism Associations, Vancouver, BC. Retrieved from http://www.intervistas.com/downloads/BC_Regional_Airports.pdf

Keller, James. (2013, April 22). Karl Lilgert, Queen of the North officer, explains how ferry crashed. Huffpost British Columbia . Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/04/22/karl-lilgert-queen-of-the-north_n_3134177.html

Kuittinen, Tero. (2014, September 19). Mobile apps are absolutely murdering San Francisco’s taxi industry. BGR . Retrieved from http://bgr.com/2014/09/19/uber-vs-lyft-vs-taxis/

Magrath, A. (2014, October 15). Longer than the shard and wider than a Boeing 747 wingspan: The world’s largest cruise ship sails into the UK for the first time. Mail Online . Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/travel_news/article-2793859/oasis-seas-world-s-largest-cruise-ship-sails-uk-time.html

Natural Resources Canada. (2013, May 15). Impacts on transportation infrastructure . Retrieved from http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/environment/resources/publications/impacts-adaptation/reports/assessments/2004/ch8/10217

Northern Rockies Regional Airport. (2014). History . Retrieved from http://www.flynorthernrockies.ca/history

Operation Lifesaver Canada. (2014). Train safety FAQ. Retrieved from http://www.operationlifesaver.ca/facts-and-stats/train-safety-faq/

Orcutt, April. (2011, November). World’s most beautiful rerry Rides.” Travel + Leisure . Retrieved from http://www.travelandleisure.com/articles/worlds-most-beautiful-ferry-rides

Owram, Kristine. (2014, July 5). Unfriendly skies await proposed low-cost airlines Canada jetlines, jet naked. The Financial Post . Retrieved from http://business.financialpost.com/2014/07/05/unfriendly-skies-await-proposed-low-cost-airlines-canada-jetlines-jet-naked/#__federated=1

Proctor, Benn. (2014, June 3). Opinion: Time to reform Vancouver’s antiquated taxi industry . The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://www.vancouversun.com/Opinion+Time+reform+Vancouver+antiquated+taxi+industry/9900418/story.html

PWC. (2012). Transportation & Logistics 2030, volume 5: Winning the talent race. [PDF] Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/transportation-logistics/pdf/pwc-tl-2030-volume-5.pdf

Rocky Mountaineer. (2014). Canadian train travel, trips, rail journeys, vacations, holidays. Rocky Mountaineer . Retrieved from http://www.rockymountaineer.com/en_CA_BC/

Science Daily. (2013, June 17). Planes, trains, or automobiles: Travel choices for a smaller carbon footprint. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/06/130617111345.htm

Tourism Vancouver. (2013, June). Vancouver Tourism master plan. [PDF] Retrieved from http://www.ticketstonight.ca/includes/content/images/media/docs/TMP-Final-doc1.pdf

WestJet. (2014). About WestJet . Retrieved from https://www.westjet.com/guest/en/about/

YCharts. (2014, September). Apple Profit Margin (Quarterly). Retrieved from http://ycharts.com/companies/AAPL/profit_margin

Attributions

Figure 2.1 Sky Jet by Jez is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 2.2 Airbus 380-800 by Ponte112 is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 2.3 airplane 036 by MamaMia05 is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

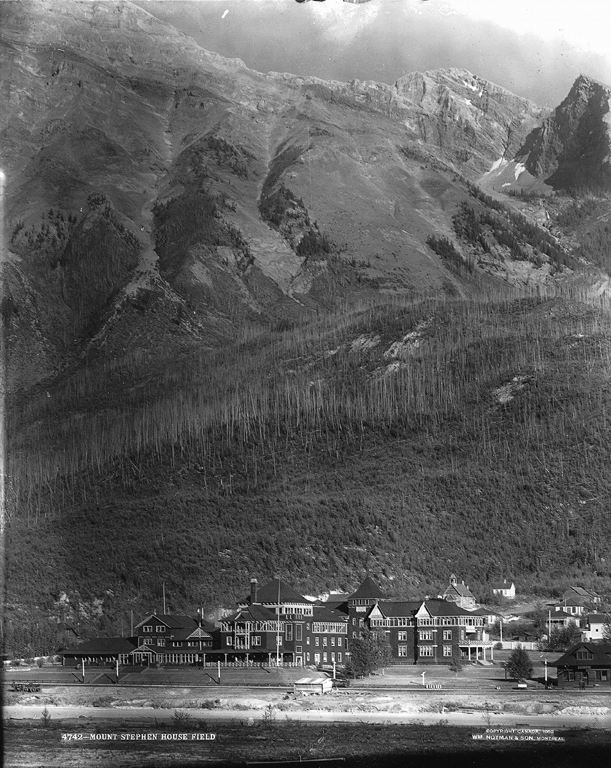

Figure 2.4 C.P.R. Mount Stephen House, Field, BC, 1909 by Musee McCord Museum has No known copyright restrictions .

Figure 2.5 Sunset Cruise by Evan Leeson is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 2.6 Uniworld River Cruises River Beatrice in Passau Germany by Gary Bembridge is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 2.7 BC Ferry by David Lewis is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 2.8 Lincoln Town Car by Nathan is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 2.9 Baltimore Airport by Lee Ruk is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

Introduction to Tourism and Hospitality in BC Copyright © 2015 by Morgan Westcott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Sustainable Transport and Tourism Destinations: Volume 13

Table of contents

Introduction.