- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Administration for Children & Families

- Upcoming Events

Physical Health

- Open an Email-sharing interface

- Open to Share on Facebook

- Open to Share on Twitter

- Open to Share on Pinterest

- Open to Share on LinkedIn

Prefill your email content below, and then select your email client to send the message.

Recipient e-mail address:

Send your message using:

The Well-Visit Planner for Families

The Well-Visit Planner is an Internet-based tool (www.wellvisitplanner.org) developed to improve well-child care for children 4 months to 6 years of age. Information in this tool is based on recommendations established by the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd Edition . The tool helps parents and caregivers to customize the well-child visit to their family's needs by helping them identify and prioritize their health risks and concerns before the well-child appointment. This means that parents and health care professionals are better able to communicate and address the family's needs during the well-child visit.

The Well-Visit Planner and Head Start

The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) has worked with the Office of Head Start National Center on Health to expand the Well-Visit Planner through age 6 years and has prepared materials to help Head Start and Early Head Start programs use this tool with the families they serve. Knowing that school readiness begins with health, Head Start and Early Head Start programs are committed to supporting the health and well-being of every child enrolled in a program. The Well-Visit Planner has been tested in several programs, and staff have found it helpful for encouraging parents to complete well-child visits and become familiar with what is expected at each visit. The tool also reinforces the role of parents as the experts for their child's needs—including those related to health.

Using the Well-Visit Planner in Head Start and Early Head Start Programs

In partnership with the National Center on Health, CAHMI has prepared a number of tools and resources to help programs assess their readiness to begin using the Well-Visit Planner as a standard part of their work with parents and children. There is also an implementation toolkit that helps programs with step-by-step implementation of the Well-Visit Planner within the program, including materials to help promote the use of the tool among parents. Materials are also there to help reach out to local health care professionals to help prepare them for the use of the Well-Visit Planner by their patient families.

These materials will be housed on the Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center but are currently available at http://www.cahmi.org/projects/wvp/ , the implementation-portal.

How does the Well-Visit Planner help families?

Completing the tool, which takes about 15 to 20 minutes, will help empower parents and caregivers to identify priorities for a child's upcoming well-child visit; it will also prepare them for what to expect at that visit. The content of the Well-Visit Planner is different based on the age of the child. It is developed to be used before each well-child visit through 6 years of age. The Well-Visit Planner also includes educational materials about topics such as a child's growth and development, language development, and safety. The educational materials address the topics of most importance for each age.

After parents use the Well-Visit Planner, they can save or print a summary or Visit Guide of the needs and priorities for the visit. They will take this summary with them to help prioritize their time with the child's pediatrician or primary health care professional. Parents can print a copy to leave with the physician or send a copy prior to the visit if the child's physician has a secure email address. The summary can also be discussed with the parents, and the family service worker and integrated into the family partnership agreement.

The Well-Visit Planner for Families The Well Visit Planner online tool: http://wellvisitplanner.org/

Resource Type: Article

National Centers: Health, Behavioral Health, and Safety

Audience: Families

Last Updated: November 21, 2023

- Privacy Policy

- Freedom of Information Act

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Viewers & Players

Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- Supporting the Grieving Child and Family

- Childhood Grief More Complicated Due to Pandemic, Marginalization

- When Your Child Needs to Take Medication at School

- American Academy of Pediatrics Updates Guidance on Medication Administration In School

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Materials & Tools

- Clinical Practice

- States & Communities

- Quality Improvement

- Implementation Stories

Bright Futures Resources for Families

The resources below can help you protect and promote your child's health by increasing your knowledge of children's health issues, providing assistance on partnering with health care providers, and linking you to helpful organizations and tools.

The Well-Child Visit: Why Go and What to Expect

Consistent with the Bright Futures Guidelines, tips written in plain language for parents of children and teens of all ages to help prepare them for their well-child visits. This tip sheet is available in English and Spanish .

- HealthyChildren.org is the official American Academy of Pediatrics Web site for parents. Backed by 66,000 pediatricians, HealthyChildren.org offers general information about children's health as well as specific guidance on parenting issues. Parents can find information on their child's ages and stages, healthy living, safety and prevention, family life, and health issues, as well as newsletters and interactive tools like the KidsDoc Symptom Checker , Ask the Pediatrician , and the Physical Developmental Delays: What to Look For Tool .

- The Screening Technical Assistance & Resource (STAR) Center is part of the Screening in Practices Initiative that envisions a system of care in which every child receives the screening, referral, and follow-up needed to foster healthy development. A family video was recently produced to highlight the positive impact that screening, referral, and follow-up can have on a family in need.

- The National Center for Family/Professional Partnerships offers information on how to connect with the Family-to-Family Health Information Center (F2F HIC) in your state. These family-staffed organizations provide support, information, resources, and training to families of children and youth with special health care needs. For example, F2F HICs provide assistance to families and professionals in navigating health care systems; guidance on health programs and policy; and collaboration with other F2F HICs, family groups, and professionals.

- The Well-Visit Planner creates a personalized visit guide for parents or guardians of children ages 4 months to 3 years old who are scheduled to have a well-child visit. Families answer questions about their children's health and pick what they want to talk about at their next visit. The Planner then makes a printable guide that families can bring to the visit and use with the doctor. The tool was developed by the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative and is based on Bright Futures Guidelines, with support from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration.

- Bright Futures Activity Book, 2nd Edition provides a fun, informative, and interactive overview of the 12 Bright Futures themes that can be explored together by children and their parents. It is in English and Spanish.

- Bright Futures at Georgetown * offers family and professional tools and materials including:

- Information on what to expect and when to seek help

- Health record forms

- Nutrition fact sheets *Many of these resources are available in both English and Spanish

- Milestone Tracker Mobile App - Track your child’s milestones from age 2 months to 5 years. Share your child’s summary with your pediatrician, get tips for encouraging your child’s development, and find out what to do if you ever become concerned about how your child is developing.

- Milestones in Action - Check out photos and videos demonstrating milestones from 2 months to 5 years of age. This library was created by CDC to help parents learn about typical developmental milestones.

- Milestone checklist - You can celebrate your child’s milestones by tracking them with a free milestone checklist and sharing it with your child’s doctor.

- How to Help Your Child/How to Talk to the Doctor

- Learn the Signs. Act Early.

- Developmental Milestones

- Essentials for Parenting Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Positive Parenting Tips

- The Medical Home and Head Start Working Together

- Caring Connections Podcast

- Early Childhood Health and Wellness

- Engaging Fathers

- Family Support & Well-being

- Parenting Your Child

- Health Tips for Families

- Parents as Teachers is an evidence-based home visiting model that promotes the optimal early development, learning, and health of children by supporting and engaging parents and caregivers. As part of their resources, Parents as Teachers produced a podcast series called Intentional Partnerships where each episode offers a real-world perspective from people exploring shared values around family engagement

- The QuestionBuilder App from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) helps parents and caregivers prepare for medical appointments and maximize time during the visit. The app is available at no cost through the Apple App store and Google Play . Access a one-page handout about the QuestionBuilder App.

Last Updated

American Academy of Pediatrics

- Professionals

Welcome to your 18-Month Well-Baby Visit Planner ®

We want to make sure you have the best enhanced 18-month well-baby visit possible., prioritize your selected items in order of importance., acknowledgements.

The website will be down for maintenance from 6:00 a.m. to noon CDT on Sunday, June 30.

KATHERINE TURNER, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(6):347-353

Related letter: Well-Child Visits Provide Physicians Opportunity to Deliver Interconception Care to Mothers

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The well-child visit allows for comprehensive assessment of a child and the opportunity for further evaluation if abnormalities are detected. A complete history during the well-child visit includes information about birth history; prior screenings; diet; sleep; dental care; and medical, surgical, family, and social histories. A head-to-toe examination should be performed, including a review of growth. Immunizations should be reviewed and updated as appropriate. Screening for postpartum depression in mothers of infants up to six months of age is recommended. Based on expert opinion, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends developmental surveillance at each visit, with formal developmental screening at nine, 18, and 30 months and autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. Well-child visits provide the opportunity to answer parents' or caregivers' questions and to provide age-appropriate guidance. Car seats should remain rear facing until two years of age or until the height or weight limit for the seat is reached. Fluoride use, limiting or avoiding juice, and weaning to a cup by 12 months of age may improve dental health. A one-time vision screening between three and five years of age is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to detect amblyopia. The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline based on expert opinion recommends that screen time be avoided, with the exception of video chatting, in children younger than 18 months and limited to one hour per day for children two to five years of age. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and transition to solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity. Juice and sugar-sweetened beverages should be avoided before one year of age and provided only in limited quantities for children older than one year.

Well-child visits for infants and young children (up to five years) provide opportunities for physicians to screen for medical problems (including psychosocial concerns), to provide anticipatory guidance, and to promote good health. The visits also allow the family physician to establish a relationship with the parents or caregivers. This article reviews the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for screenings and recommendations for infants and young children. Family physicians should prioritize interventions with the strongest evidence for patient-oriented outcomes, such as immunizations, postpartum depression screening, and vision screening.

Clinical Examination

The history should include a brief review of birth history; prematurity can be associated with complex medical conditions. 1 Evaluate breastfed infants for any feeding problems, 2 and assess formula-fed infants for type and quantity of iron-fortified formula being given. 3 For children eating solid foods, feeding history should include everything the child eats and drinks. Sleep, urination, defecation, nutrition, dental care, and child safety should be reviewed. Medical, surgical, family, and social histories should be reviewed and updated. For newborns, review the results of all newborn screening tests ( Table 1 4 – 7 ) and schedule follow-up visits as necessary. 2

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A comprehensive head-to-toe examination should be completed at each well-child visit. Interval growth should be reviewed by using appropriate age, sex, and gestational age growth charts for height, weight, head circumference, and body mass index if 24 months or older. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-recommended growth charts can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm#The%20WHO%20Growth%20Charts . Percentiles and observations of changes along the chart's curve should be assessed at every visit. Include assessment of parent/caregiver-child interactions and potential signs of abuse such as bruises on uncommonly injured areas, burns, human bite marks, bruises on nonmobile infants, or multiple injuries at different healing stages. 8

The USPSTF and AAP screening recommendations are outlined in Table 2 . 3 , 9 – 27 A summary of AAP recommendations can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf . The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) generally adheres to USPSTF recommendations. 28

MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Prevalence of postpartum depression is around 12%, 22 and its presence can impair infant development. The USPSTF and AAP recommend using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1015/p926.html#afp20101015p926-f1 ) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0115/p139.html#afp20120115p139-t3 ) to screen for maternal depression. The USPSTF does not specify a screening schedule; however, based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends screening mothers at the one-, two-, four-, and six-month well-child visits, with further evaluation for positive results. 23 There are no recommendations to screen other caregivers if the mother is not present at the well-child visit.

PSYCHOSOCIAL

With nearly one-half of children in the United States living at or near the poverty level, assessing home safety, food security, and access to safe drinking water can improve awareness of psychosocial problems, with referrals to appropriate agencies for those with positive results. 29 The prevalence of mental health disorders (i.e., primarily anxiety, depression, behavioral disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in preschool-aged children is around 6%. 30 Risk factors for these disorders include having a lower socioeconomic status, being a member of an ethnic minority, and having a non–English-speaking parent or primary caregiver. 25 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence regarding screening for depression in children up to 11 years of age. 24 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends that physicians consider screening, although screening in young children has not been validated or standardized. 25

DEVELOPMENT AND SURVEILLANCE

Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends early identification of developmental delays 14 and autism 10 ; however, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend formal developmental screening 13 or autism-specific screening 9 if the parents/caregivers or physician have no concerns. If physicians choose to screen, developmental surveillance of language, communication, gross and fine movements, social/emotional development, and cognitive/problem-solving skills should occur at each visit by eliciting parental or caregiver concerns, obtaining interval developmental history, and observing the child. Any area of concern should be evaluated with a formal developmental screening tool, such as Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status-Developmental Milestones, or Survey of Well-Being of Young Children. These tools can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Screening/Pages/Screening-Tools.aspx . If results are abnormal, consider intervention or referral to early intervention services. The AAP recommends completing the previously mentioned formal screening tools at nine-, 18-, and 30-month well-child visits. 14

The AAP also recommends autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months. 10 The USPSTF recommends using the two-step Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) screening tool (available at https://m-chat.org/ ) if a physician chooses to screen a patient for autism. 10 The M-CHAT can be incorporated into the electronic medical record, with the possibility of the parent or caregiver completing the questionnaire through the patient portal before the office visit.

IRON DEFICIENCY

Multiple reports have associated iron deficiency with impaired neurodevelopment. Therefore, it is essential to ensure adequate iron intake. Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends supplements for preterm infants beginning at one month of age and exclusively breastfed term infants at six months of age. 3 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for iron deficiency in infants. 19 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends measuring a child's hemoglobin level at 12 months of age. 3

Lead poisoning and elevated lead blood levels are prevalent in young children. The AAP and CDC recommend a targeted screening approach. The AAP recommends screening for serum lead levels between six months and six years in high-risk children; high-risk children are identified by location-specific risk recommendations, enrollment in Medicaid, being foreign born, or personal screening. 21 The USPSTF does not recommend screening for lead poisoning in children at average risk who are asymptomatic. 20

The USPSTF recommends at least one vision screening to detect amblyopia between three and five years of age. Testing options include visual acuity, ocular alignment test, stereoacuity test, photoscreening, and autorefractors. The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening before three years of age. 26 The AAP, American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the American Academy of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus recommend the use of an instrument-based screening (photoscreening or autorefractors) between 12 months and three years of age and annual visual acuity screening beginning at four years of age. 31

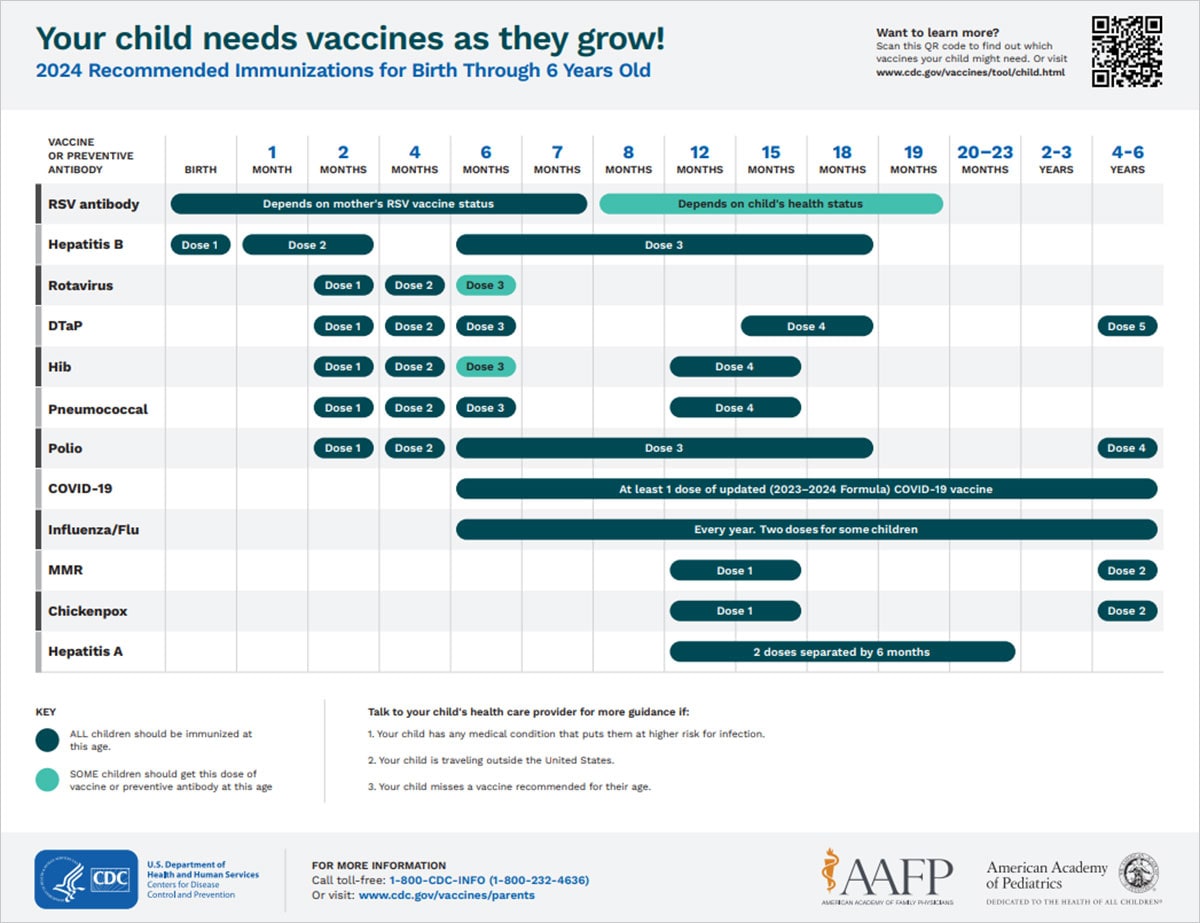

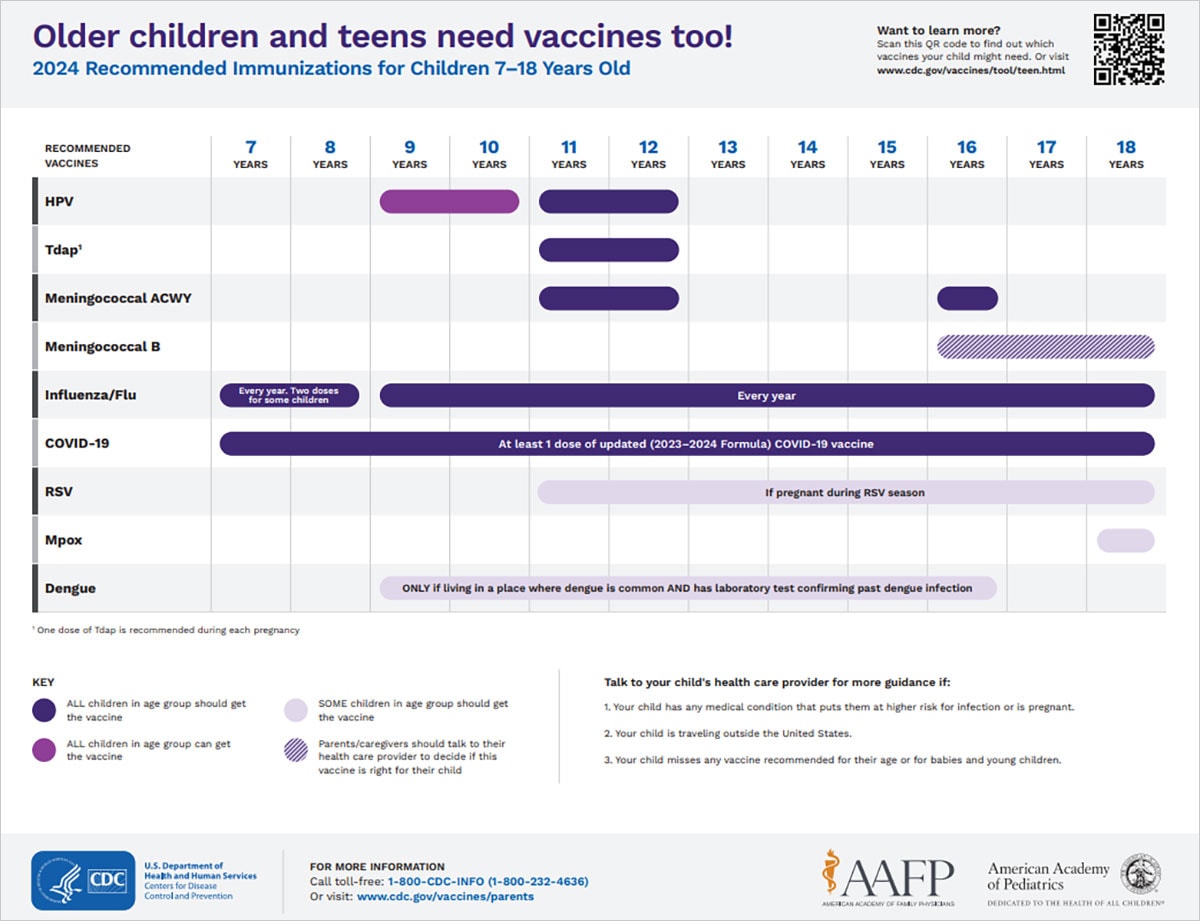

IMMUNIZATIONS

The AAFP recommends that all children be immunized. 32 Recommended vaccination schedules, endorsed by the AAP, the AAFP, and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, are found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season. Additional vaccinations may be necessary based on medical history. 33 Immunization history should be reviewed at each wellness visit.

Anticipatory Guidance

Injuries remain the leading cause of death among children, 34 and the AAP has made several recommendations to decrease the risk of injuries. 35 – 42 Appropriate use of child restraints minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with motor vehicle collisions. Infants need a rear-facing car safety seat until two years of age or until they reach the height or weight limit for the specific car seat. Children should then switch to a forward-facing car seat for as long as the seat allows, usually 65 to 80 lb (30 to 36 kg). 35 Children should never be unsupervised around cars, driveways, and streets. Young children should wear bicycle helmets while riding tricycles or bicycles. 37

Having functioning smoke detectors and an escape plan decreases the risk of fire- and smoke-related deaths. 36 Water heaters should be set to a maximum of 120°F (49°C) to prevent scald burns. 37 Infants and young children should be watched closely around any body of water, including water in bathtubs and toilets, to prevent drowning. Swimming pools and spas should be completely fenced with a self-closing, self-latching gate. 38

Infants should not be left alone on any high surface, and stairs should be secured by gates. 43 Infant walkers should be discouraged because they provide no benefit and they increase falls down stairs, even if stair gates are installed. 39 Window locks, screens, or limited-opening windows decrease injury and death from falling. 40 Parents or caregivers should also anchor furniture to a wall to prevent heavy pieces from toppling over. Firearms should be kept unloaded and locked. 41

Young children should be closely supervised at all times. Small objects are a choking hazard, especially for children younger than three years. Latex balloons, round objects, and food can cause life-threatening airway obstruction. 42 Long strings and cords can strangle children. 37

DENTAL CARE

Infants should never have a bottle in bed, and babies should be weaned to a cup by 12 months of age. 44 Juices should be avoided in infants younger than 12 months. 45 Fluoride use inhibits tooth demineralization and bacterial enzymes and also enhances remineralization. 11 The AAP and USPSTF recommend fluoride supplementation and the application of fluoride varnish for teeth if the water supply is insufficient. 11 , 12 Begin brushing teeth at tooth eruption with parents or caregivers supervising brushing until mastery. Children should visit a dentist regularly, and an assessment of dental health should occur at well-child visits. 44

SCREEN TIME

Hands-on exploration of their environment is essential to development in children younger than two years. Video chatting is acceptable for children younger than 18 months; otherwise digital media should be avoided. Parents and caregivers may use educational programs and applications with children 18 to 24 months of age. If screen time is used for children two to five years of age, the AAP recommends a maximum of one hour per day that occurs at least one hour before bedtime. Longer usage can cause sleep problems and increases the risk of obesity and social-emotional delays. 46

To decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the AAP recommends that infants sleep on their backs on a firm mattress for the first year of life with no blankets or other soft objects in the crib. 45 Breastfeeding, pacifier use, and room sharing without bed sharing protect against SIDS; infant exposure to tobacco, alcohol, drugs, and sleeping in bed with parents or caregivers increases the risk of SIDS. 47

DIET AND ACTIVITY

The USPSTF, AAFP, and AAP all recommend breastfeeding until at least six months of age and ideally for the first 12 months. 48 Vitamin D 400 IU supplementation for the first year of life in exclusively breastfed infants is recommended to prevent vitamin D deficiency and rickets. 49 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends the introduction of certain foods at specific ages. Early transition to solid foods before six months is associated with higher consumption of fatty and sugary foods 50 and an increased risk of atopic disease. 51 Delayed transition to cow's milk until 12 months of age decreases the incidence of iron deficiency. 52 Introduction of highly allergenic foods, such as peanut-based foods and eggs, before one year decreases the likelihood that a child will develop food allergies. 53

With approximately 17% of children being obese, many strategies for obesity prevention have been proposed. 54 The USPSTF does not have a recommendation for screening or interventions to prevent obesity in children younger than six years. 54 The AAP has made several recommendations based on expert opinion to prevent obesity. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and introduction of solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity and are not recommended. 55 Drinking juice should be avoided before one year of age, and, if given to older children, only 100% fruit juice should be provided in limited quantities: 4 ounces per day from one to three years of age and 4 to 6 ounces per day from four to six years of age. Intake of other sugar-sweetened beverages should be discouraged to help prevent obesity. 45 The AAFP and AAP recommend that children participate in at least 60 minutes of active free play per day. 55 , 56

Data Sources: Literature search was performed using the USPSTF published recommendations ( https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations ) and the AAP Periodicity table ( https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf ). PubMed searches were completed using the key terms pediatric, obesity prevention, and allergy prevention with search limits of infant less than 23 months or pediatric less than 18 years. The searches included systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and position statements. Essential Evidence Plus was also reviewed. Search dates: May through October 2017.

Gauer RL, Burket J, Horowitz E. Common questions about outpatient care of premature infants. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):244-251.

American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital stay for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):405-409.

Baker RD, Greer FR Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040-1050.

Mahle WT, Martin GR, Beekman RH, Morrow WR Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Executive Committee. Endorsement of Health and Human Services recommendation for pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):190-192.

American Academy of Pediatrics Newborn Screening Authoring Committee. Newborn screening expands: recommendations for pediatricians and medical homes—implications for the system. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):192-217.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):898-921.

Maisels MJ, Bhutani VK, Bogen D, Newman TB, Stark AR, Watchko JF. Hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant > or = 35 weeks' gestation: an update with clarifications. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1193-1198.

Christian CW Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, American Academy of Pediatrics. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;136(3):583]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1337-e1354.

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for autism spectrum disorder in young children: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(7):691-696.

Johnson CP, Myers SM American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183-1215.

Moyer VA. Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1102-1111.

Clark MB, Slayton RL American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):626-633.

Siu AL. Screening for speech and language delay and disorders in children aged 5 years and younger: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e474-e481.

Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2006;118(4):1808–1809]. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405-420.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(6):625-633.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. October 2012. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/peds_guidelines_full.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018.

Moyer VA. Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):613-619.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2017;140(6):e20173035]. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171904.

Siu AL. Screening for iron deficiency anemia in young children: USPSTF recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):746-752.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in children and pregnant women. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2514-2518.

Screening Young Children for Lead Poisoning: Guidance for State and Local Public Health Officials . Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Public Health Service; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Environmental Health; 1997.

O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and post-partum women: evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388-406.

Earls MF Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032-1039.

Siu AL. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):360-366.

Weitzman C, Wegner L American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Early Childhood; Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting optimal development: screening for behavioral and emotional problems [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;135(5):946]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):384-395.

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(9):836-844.

Donahue SP, Nixon CN Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

Lin KW. What to do at well-child visits: the AAFP's perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6):362-364.

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339.

Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):315-328.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment of infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation. Immunizations. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/immunizations.html . Accessed October 5, 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger, United States, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Accessed May 9, 2018.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2015_1050w740h.gif . Accessed April 24, 2017.

Durbin DR American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Child passenger safety. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):788-793.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Reducing the number of deaths and injuries from residential fires. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1355-1357.

Gardner HG American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Office-based counseling for unintentional injury prevention. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):202-206.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of drowning in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):437-439.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):790-792.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Falls from heights: windows, roofs, and balconies. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1188-1191.

Dowd MD, Sege RD Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee; American Academy of Pediatrics. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416-e1423.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):601-607.

Kendrick D, Young B, Mason-Jones AJ, et al. Home safety education and provision of safety equipment for injury prevention (review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(3):761-939.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1224-1229.

Heyman MB, Abrams SA American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. Fruit juice in infants, children, and adolescents: current recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20170967.

Council on Communications and Media. Media and young minds. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162591.

Moon RY Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841.

Wagner CL, Greer FR American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2009;123(1):197]. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1142-1152.

Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544-e551.

Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition; Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183-191.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The use of whole cow's milk in infancy. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 pt 1):1105-1109.

Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa'ad AH, Pongracic JA. Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):29-36.

Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2417-2426.

Daniels SR, Hassink SG Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e275-e292.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Physical activity in children. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/physical-activity.html . Accessed January 1, 2018.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Using the Well Visit Planner to Support Parents’ Effective Communication with Their Child’s Health Care Provider

Related Resources

The Carolinas Collaborative: How a pediatric residency training program collaborative improved community health and advocacy curricula

This is an abstract published in the 2019 Special Issue of Academic Pediatrics, briefly highlighting the impact of the Carolinas Collaborative…

COVID-19’s Impact on Pediatric Healthcare in South Carolina: Supporting and Strengthening the Sector

For a summarized brief, see the Executive Summary. While the worst direct impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic seem to…

Psychiatric Comorbidities in ASD: Prevalence, Presentation, Treatments, and Barriers

© Copyright 2024 Institute for Child Success Institute for Child Success® — Kids Drive Our Future® Web Design by Beam & Hinge Photos courtesy of the Robin Hood Foundation and iStock

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Catch Up on Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations

Many children missed check-ups and recommended childhood vaccinations over the past few years. CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend children catch up on routine childhood vaccinations and get back on track for school, childcare, and beyond.

Making sure that your child sees their doctor for well-child visits and recommended vaccines is one of the best things you can do to protect your child and community from serious diseases that are easily spread.

Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations Are Essential

Well-child visits and recommended vaccinations are essential and help make sure children stay healthy. Children who are not protected by vaccines are more likely to get diseases like measles and whooping cough . These diseases are extremely contagious and can be very serious, especially for babies and young children. In recent years, there have been outbreaks of these diseases, especially in communities with low vaccination rates.

Well-child visits are essential for many reasons , including:

- Tracking growth and developmental milestones

- Discussing any concerns about your child’s health

- Getting scheduled vaccinations to prevent illnesses like measles and whooping cough (pertussis) and other serious diseases

It’s particularly important for parents to work with their child’s doctor or nurse to make sure they get caught up on missed well-child visits and recommended vaccines.

Routinely Recommended Vaccines for Children and Adolescents

Getting children and adolescents caught up with recommended vaccinations is the best way to protect them from a variety of vaccine-preventable diseases . The schedules below outline the vaccines recommended for each age group.

See which vaccines your child needs from birth through age 6 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

See which vaccines your child needs from ages 7 through 18 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program’s requirements and talk to your child’s doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider. You can also find a VFC provider by calling your state or local health department or seeing if your state has a VFC website.

COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens

Everyone aged 6 months and older can get an updated COVID-19 vaccine to help protect against severe illness, hospitalization and death. Learn more about making sure your child stays up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines .

- Vaccines & Immunizations

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Pastor Robert Morris resigns from Gateway Church after child sex abuse allegation

Robert Morris has resigned as senior pastor at Gateway Church in Southlake, Texas, three days after confessing to engaging in “sexual behavior” with a child over the course of a few years in the 1980s.

The board of elders at Gateway made the announcement Tuesday in a statement to NBC News.

“The elders’ prior understanding was that Morris’s extramarital relationship, which he had discussed many times throughout his ministry, was with ‘a young lady’ and not abuse of a 12-year-old child,” the church leaders said in their statement, noting that they had not known the victim’s age or the length of the alleged abuse. “Even though it occurred many years before Gateway was established, as leaders of the church, we regret that we did not have the information that we now have.”

The megachurch also announced it had hired the law firm Haynes & Boone to conduct an independent review of the allegations to ensure elders had a complete understanding of what happened.

Morris, a former member of President Donald Trump’s spiritual advisory committee, had long told a story to his congregation and church leaders about a “moral failure” involving sexual sin when he was a young minister in his 20s.

Last week, Cindy Clemishire, now 54, revealed in a post on the church watchdog site The Wartburg Watch that she was 12 when Morris first sexually abused her in 1982. The alleged abuse continued for more than four years, Clemishire told NBC News on Monday.

Gateway and Morris responded to Clemishire’s allegation by releasing statements on Friday and Saturday acknowledging that Morris had engaged in “sexual behavior with a young lady” and stating that the “sin was dealt with correctly by confession and repentance.”

Clemishire released a statement Tuesday saying she had “mixed feelings” about Morris’ resignation.

“Though I am grateful that he is no longer a pastor at Gateway, I am disappointed that the Board of Elders allowed him to resign,” she said in the statement. “He should have been terminated.”

Clemishire added that she had repeatedly disclosed the abuse to church leaders and pastors, including at Gateway, but it was not until she spoke publicly that action was taken.

Morris did not respond to a message requesting comment.

Gateway officials did not respond to a message from NBC News on Tuesday asking why church leaders issued a statement referring to Clemishire as a young lady after she’d publicly revealed she was a child when the abuse began.

Morris is known for his efforts to advance conservative Christian morality through government and Republican politics. As news of the allegations against him spread in national media, some of his allies have distanced themselves from him.

A spokesperson for Trump said Morris was not working with the presidential campaign. And Texas state Reps. Nate Schatzline and Giovanni Capriglione, both Republicans representing areas where Gateway has campuses, issued statements condemning Morris’ actions.

“Pastor Morris must be held accountable,” Capriglione wrote shortly before Morris’ resignation was announced. “The pain he has caused cannot be erased, and he should face the consequences of his crimes. I stand with any victims and will continue to fight for their rights and safety.”

In their official statement, Gateway elders expressed remorse over their handling of the situation.

“For the sake of the victim, we are thankful this situation has been exposed,” the statement said. “We know many have been affected by this, we understand that you are hurting, and we are very sorry. It is our prayer that, in time, healing for all those affected can occur.”

Mike Hixenbaugh is a senior investigative reporter for NBC News, based in Maryland, and author of "They Came for the Schools."

- Family Resources

- Provider Info

Are you a health care provider or member of a community organization?

Well Visit Planner

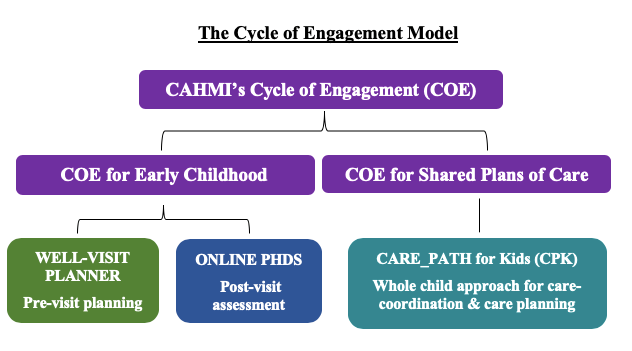

Providers and health care organizations have a responsibility to optimize the health of their patients and their families through partnership and engagement. The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) wishes to support health care organizations and providers in their adoption of family engagement and quality family-centered health care. The CAHMI has developed the guideline-based and easy-to-use Well Visit Planner (WVP) to engage parents and partners to improve the quality of care for children.

Learn more about the WVP from this 2-page Overview and Frequently Asked Questions for Providers

Cycle of Engagement

You may choose to use the WVP with an online, parent-completed quality assessment tool, the Online Promoting Healthy Development Survey (Online PHDS) ( https://www.onlinephds.org ) to complete the Cycle of Engagement (COE) for early childhood. You can also use the COE for care-coordination and care planning with the CARE_PATH for Kids (CPK) model and tools.

The COE is a model for engaging parents in an ongoing, collaborative way to learn about, measure, and improve the quality and outcomes of care for children. The COE uses a personalized and systems-integrated approach based on guidelines and best practices. The model is comprised of pre-visit planning , within-visit engagement and post-visit assessment. Learn more about the COE from this 2-page Overview .

Examples of WVP Use in Community Organizations

If you are a member of a health care or community organization, you can implement the Well Visit Planner to empower families of children between 4 months and 6 years to become partners in the care of their children. Here are a few examples of the WVP being used at a community organization level.

- Family Voices works with CAHMI to ensure that families of children and youth with special health needs (CYSHCN) are at the center of quality measurement and improvement. The organization has worked with diverse family leaders to provide input on materials to help promote the WVP and has created many materials to support its implementation. Click here to learn more.

- CAHMI has in the past, worked with the Office of Head Start National Center on Health to expand the Well Visit Planner through age 6 years and has prepared materials to help Head Start and Early Head Start programs use this tool with the families they serve. Click here to learn more.

- The CAHMI also partnered with the Help Me Grow National Center to utilize the WVP to provide support for HMG affiliate sites to engage families, communities, and child health providers in promoting children’s healthy development. Click here to learn more.

- The WVP has also been implemented in western Mexico with a group of low-income families in 3 communities, who used the tool to learn about child development and identify their needs for group visits.

Get Started

Get oriented to use the WVP by getting this WVP Getting Started Toolkit .

Your provider ID code

If your child’s provider has invited you to use their tailored Well Visit Planner, you can enter their ID code below. This ID code is also the text included after “/” in the WVP URL that your child’s provider shared (i.e. www.wellvisitplanner.org/ providerIDcode ).

Your Customized Well Visit Planner

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Phasellus ut urna ultricies, eleifend tortor ac, sollicitudin tortor. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Nunc convallis mi sed consequat tempor. Praesent rhoncus nibh tellus, in sodales neque pellentesque eu

Well Visit Planner: Voluntary Consent

Your privacy is important to us. Please review our terms and conditions , and consent form , check each box below and click the Continue button below.

VOLUNTARY CONSENT FORM

The purpose of the tool, the Well Visit Planner (WVP), is to enable parents to optimize visit time by focusing on priorities, concerns, and other issues specific to the child and family. The WVP asks parents about their child and family and the kind of topics they want to discuss at their child’s well-child visit. The health care provider can use this information to customize the visit to the needs of the parent and child. Additionally, the tool provides educational information about potential discussion topics based on national recommendations for health care providers.

To use this tool, complete the online Well Visit Planner which should take you about 10 minutes. You will be asked to do the following:

- Agree to the WVP Terms and Conditions.

- You will be asked to voluntarily consent to allow the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative to mine the de-identified information that you provide in order to analyze and improve the WVP tool.

- Provide basic information about your child who has the upcoming well-child visit.

- Answer a series of questions about your child and family that will help you and your child's health care provider know what they may need to focus on during the visit.

- Pick the topics that you want your child's doctor to address and give you information about at the upcoming visit.

- Receive a "Visit Guide" that you may use at your child's well-visit. This guide highlights the topics you may want to discuss and should be brought to the visit.

- You have the option of creating your own account on the WVP. You can use your account to plan future visits, complete unfinished WVP visits, add other eligible children, and review previous Visit Guides and educational information.

Although we have made every effort to protect your identity, there is a minimal risk of loss of confidentiality. Additionally, you may find that some questions or topics cause you emotional discomfort. You may choose not to answer some of the questions. The choice is up to you.

You may or may not benefit from using the online Well Visit Planner. However, by completing the online tool, you may improve your child's well-visit and you may receive useful information in partnering with your child's health care provider. Additionally, the answers you provide may help your child's health care provider understand your child and family health so that they can better provide well-child care for you. Finally, your participation may help us learn how to benefit parents and children in the future by providing information to health care providers that will help them improve well-child visits.

Confidentiality

We implement a variety of security measures to maintain the safety of your personal information when you enter or submit answers. We offer the use of a secure server. All supplied sensitive information is housed in our database which is protected through a secure dedicated port which only allows data entry from the tool to our database. The database is protected by having a closed-off port for the SQL Server installation. Only authorized personnel with special access rights to our systems are given access to the data. We are required to keep the information confidential.

The WVP does not collect protected health information or information that can lead to the identification of you or your child. You are asked to provide only two pieces of personally identifiable information: child’s first name (optional) and date of birth. These are not stored in our database. The child’s first name is displayed on the Visit Guide. The date of birth is used to calculate the appropriate upcoming well-visit and present the age-specific questions. That visit (e.g. 4 month or 6 month) is stored in our database rather than the date of birth. If you choose to create an account on the WVP, you have the option to add your child’s first name or nickname to appear on the family dashboard and Visit Guide. This name will be saved on our secure servers.

The email address that you use for registering an account will not be shared with any third parties, nor will your email address be sold or used for purposes other than sharing educational resources or sending updates about the Well Visit Planner. You can unsubscribe if you wish to stop receiving emails from us by sending us an email on [email protected] .

In addition, identifying information connected to your computer (IP address) will not be recorded by the CAHMI at any time. If you choose to download or print your Visit Guide, CAHMI will not be liable for any actions related to your choice to disseminate, distribute or copy the Visit Guide with the name(s) of your child(ren) or any other information contained in the guide.

The Well Visit Planner will store the de-identified information that you provide about your child's health, development, and home environment; along with the priorities you select on a secure server. It will not be possible to link this anonymous information to you or your child. We will use this anonymous information to understand parents' concerns and priorities for their well-child visits. This information may also be combined with other parents’ responses and shared with your child’s provider to help them learn more about families they provide care to and improve well-child care for children and their families.

Access and use the Well Visit Planner is free.

You do not have to use the Well Visit Planner. If you do elect to use the Well Visit Planner, and later change your mind, you may discontinue use at any time. If you do not complete the WVP, there will be no penalty or loss of any benefits to which you are otherwise entitled.

If you have any questions, you may contact us at [email protected]

Session Warning!

Session expired.

We need to put a moratorium on destructive private school vouchers until North Carolina’s public schools are fully funded. Learn more here.

State Government websites value user privacy. To learn more, view our full privacy policy .

Secure websites use HTTPS certificates. A lock icon or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the official website.

Governor Cooper Visits Charlotte Child Care Center, Highlights Urgent Funding Need For Early Childhood Education and Child Care

Today, Governor Roy Cooper visited The Early Learning Center Preschool in Charlotte and visited several classrooms to see strong child care in action as well as learning and growing through engaging activities. The Governor was joined by President and CEO of Child Care Resources Inc. Janet Singerman and local officials as he highlighted the urgent funding need for early childhood education and child care. The Early Learning Center Preschool is a 5-star licensed child care center and NC Pre-K program provider.

“Child care centers like The Early Learning Center Preschool teach children important building blocks and help prepare them for their future," said Governor Cooper. “A lack of access to child care is preventing parents from entering the workforce, meanwhile Republican legislators plan to spend $625 million on taxpayer-funded private school vouchers. We must address the upcoming funding cliff and invest in early childhood education and child care.”

“Increasing the budget for Early Childhood Education is essential for enhancing the quality of care and early education, which directly impacts children's development and future academic success,” said The Early Learning Center Preschool Administrative Assistant Artasia Porter-Harris. “This investment not only supports working parents by offering affordable and reliable childcare options but also stimulates economic growth by enabling parents to participate fully in the workforce. Additionally, well-funded childcare centers can attract and retain qualified staff, ensuring a safe and nurturing environment for children.”

“High-quality child care programs support healthy development and early learning for young children, during the most critical years of children’s development,” said President and CEO of Child Care Resources Inc. Janet Singerman. “Our programs here in Charlotte and across the state need well-trained early childhood teachers. Without adequate compensation and the support to sustain their quality, we are in danger of losing three in ten child care programs and 92,000 child spaces.”

Child Care Resources Inc. works to ensure children have access to quality, affordable early learning opportunities. Child Care Resources Inc. is the administrator for Mecklenburg County’s child care subsidy programs and is the grantee for Early Head Start – Child Care partnerships in Mecklenburg and Burke Counties.

A recent statewide survey shows that nearly a third of North Carolina child care centers are at risk of closing their doors when the Child Care Stabilization Grants that were made possible by federal funding end in June. Without additional investment, survey results show that North Carolina’s child care centers will lose quality teachers, have difficulty hiring, and will have to raise fees on parents.

North Carolina’s nationally-recognized NC Pre-K program is also at risk this year. Instead of providing the investment needed to sustain and grow this celebrated and high-quality program, the legislature has chosen to funnel $625 million in taxpayer-funded private school vouchers to the wealthy.

In April, Governor Cooper released his recommended budget for FY 2024-2025, Securing North Carolina’s Future , that includes an urgently needed $745 million investment to strengthen access to child care and early education for working families. Governor Cooper’s budget provides child care stabilization grants to ensure child care centers stay open and can continue serving children, prioritizes funding to help working families afford childcare, helps qualified educators afford to keep teaching, and makes child care more available, especially in our rural areas.

The Governor’s budget proposal includes:

- $200 million for Child Care Stabilization Grants to keep child care centers open when federal funding ends this summer. These grants support better compensation for the early educator workforce to keep good teachers in our early childhood classrooms.

- $128.5 million for the Child Care Subsidy Program to increase rates that will benefit child care providers and families in rural and lower-wealth communities and $10 million for Smart Start. Investments will help recruit and retain early childhood educators by providing competitive wages, plus help for early childhood teachers to afford child care for their own children.

- $197 million for the NC Pre-K Program to increase rates to cover the full cost for NC Pre-K students, which is needed to shore up the program.

- $24.4 million for summer care and learning programs for students after they complete NC Pre-K and before they enter kindergarten.

- A refundable child and dependent care tax credit worth up to $600 for the average family of four that will further reduce the burden of child care costs for working families.

Governor Cooper declared 2024 as the Year of Public Schools and has been touring public schools and early childhood education programs across the state calling for investments in K-12 education, early childhood education and teacher pay. The Governor has also called for a stop to state spending on vouchers for unaccountable and unregulated private schools until North Carolina’s public schools are fully funded.

Governor Cooper is committed to prioritizing public schools and to hearing from the many communities across the state who know that strong public schools ensure we have strong communities.

Read "The Year of Public Schools" proclamation here .

Read more about the truth of North Carolina's voucher program here .

Related Topics:

- Governor's Office

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Welcome to the Well Visit Planner ® Your Child, Your Well Visit. A quick and free pre-visit planning tool to focus care on your unique needs and goals. Get started now: Covers all 15 age-specific well visits from your child's first week of life to age 6. Enter provider ID code Continue without code. Learn more about creating a family account

The Well Visit Planner® is a family engagement-based approach to improve the quality and positive impact of early childhood health promotion and preventive services for all children and families. The Well Visit Planner® was designed, developed and tested with families and child health professionals between 2008-2016 by the Child and ...

The Well-Visit Planner is an Internet-based tool (www.wellvisitplanner.org) developed to improve well-child care for children 4 months to 6 years of age. Information in this tool is based on recommendations established by the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd Edition.

The Well-Child Visit: Why Go and What to Expect . Consistent with the Bright Futures Guidelines, tips written in plain language for parents of children and teens of all ages to help prepare them for their well-child visits. ... The Well-Visit Planner creates a personalized visit guide for parents or guardians of children ages 4 months to 3 ...

What to expect during your visit. A well-child visit is a chance to get regular updates about your child's health and development. Your health care team will take measurements, conduct a head-to-toe examination, update immunizations, and offer you a chance to talk with your health care professional. Your well-child visit includes 4 specific ...

The Well-Visit Planner (WVP) is an online pre-visit planning tool designed to customize, tailor and improve the quality of well-child care for young children, by engaging parents as proactive partners in planning and conducting well-child care visits. This family-centered quality improvement method guides parents to identify priorities and key ...

Learn more about the Well Visit Planner at https://www.wellvisitplanner.orgThe WVP is a tool created by the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiativ...

The Well Visit Planner was created and evaluated in partnership with families and child health care providers. The free, convenient Well Visit Planner covers all 15 well visits recommended to occur between a child's first week to sixth year of life. When families use the Well Visit Planner they will:

Includes 15 age-specific Well Visit Planner tools tailored for each child (ages: 1-week, 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, 60, and 72 months) Takes 10 minutes to get a personalized Well Visit Guide; Available in English and Spanish; Mobile optimized

The 18-Month Well-Baby Visit Planner content and design is based on the Well Visit Planner® (WVP), which is developed and maintained by the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). CAHMI is a national center at Johns Hopkins University. Its not-for-profit Center for the Advancement of Innovative Health Practice holds the ...

Welcome to the Well Visit Planner Frequently Asked Questions for Families. Download this family friendly handout about the Well Visit Planner®. Get more information about the Well Visit Planner®. Click here to learn more about how child health professionals can customize and use the WVP with the children and families they serve.

quality assessment give voice to families and help child and family care teams: 1. Integrate and streamline family-reported screening and priority setting. 2. Prepare for and optimize time during visits to focus on the family's agenda. 3. Focus on building strengths and coordinating resources and supports. 4.

The Well Visit it work? Planner is mobile-optimized and is available in both English and Spanish! Well Visit Planner (WVP) possible. Covers 11 different ages between 4 months and six years of age. Each visit is different! Thank you for partnering with us to improve your child's well visit care! Your Child, Your Well Visit A project of the ...

about the purpose of well-child visits, 3) allowed them to more fully partner in well-child care visits and 4) would be recommended to other parents. ... Engaging your team in a decision to employ the Well-Visit Planner (WVP) is the first and most important implementation step. Solid buy-in from staff is essential to every aspect of implementation.

Pre-visit planning to personalize care using the Well Visit Planner (WVP) Within-visit engagement that optimizes time spent during Personalized, Connected ... post-visit assessment of the quality of well child services resulting in reports and improvement resources for care teams and providers, with feedback and resources shared with families. ...

Understand what the Well Visit Planner is . 2. Demonstrate the Well Visit Planner Tool . 3. Understand how families will be better prepared for their child's well visits by using the Well Visit Planner . 4. Learn about the variety of tools to help promote the Well Visit Planner . 4

Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season ...

On this page, you can access Family Resource Sheets by child age or well-visit focus area. Family Resource Sheets have information and links to additional resources to support the healthy development of children and the well-being of families. Click on the age or topic below to get a variety of Family Resource Sheets. Get Resource Sheets by Age.

Using the Well Visit Planner to Support Parents' Effective Communication with Their Child's Health Care Provider. Download Resource. Back to Resources. Related Resources. POSITIVE PARENTING TIPS FOR CLINICIANS. HEALTH EQUITY AND SYSTEMS LEADERSHIP.

Welcome to the Well Visit Planner ® Your Child, Your Well Visit. A quick and free pre-visit planning tool to focus care on your unique needs and goals. Get started now: Covers all 15 age-specific well visits from your child's first week of life to age 6. GET STARTED NOW. Learn more about creating a family account

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program's requirements and talk to your child's doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider.

Robert Morris has resigned as senior pastor at Gateway Church in Southlake, Texas, three days after confessing to engaging in "sexual behavior" with a child over the course of a few years in ...

The Well Visit Planner is currently available for each of the 15 well visits recommended to occur between a child's first week through their sixth year of life. The evidence-based Well Visit Planner (WVP) is: A family-completed online, mobile-optimized pre-visit planning tool covering all 15 well visits recommended to occur between the first ...

The CAHMI has developed the guideline-based and easy-to-use Well Visit Planner (WVP) to engage parents and partners to improve the quality of care for children. Learn more about the WVP from this 2-page Overview and Frequently Asked Questions for Providers. Cycle of Engagement. You may choose to use the WVP with an online, parent-completed ...

Today, Governor Roy Cooper visited The Early Learning Center Preschool in Charlotte and visited several classrooms to see strong child care in action as well as learning and growing through engaging activities. The Governor was joined by President and CEO of Child Care Resources Inc. Janet Singerman and local officials as he highlighted the urgent funding need for early childhood education and ...