Sales: +1 224 529 4400

Maternity Obstetrical Care Medical Billing & Coding Guide for 2024

Coding and billing for maternity obstetrical care is quite a bit different from other sections of the American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology (CPT).

Maternity care services typically include antepartum care, delivery services, as well as postpartum care. Depending on the patient’s circumstances and insurance carrier, the provider can either:

- Submit all rendered services for the entire nine months of services on one CMS-1500 claim form for full term deliveries for most private payers including Medicare.

- Submit claims based on an itemization of maternity care services. (e.g., most state Medicaid payers require claim submission per visit.)

Let us discuss what you need to know about maternity obstetrical care medical billing.

Maternity Obstetrical Care Medical Billing & Coding Guide for 2024

This article explores the key aspects of maternity obstetrical care medical billing and breaks down the vital information your OB/GYN practice needs to know. We will go over:

- Different types of services rendered

- The global maternity care package: what services are included and excluded?

- The split OB packages

- Complications of pregnancy

- High-risk patients

- CPT definitions

- And much more

Finally, always be aware that individual insurance carriers provide additional information such as modifier use.

We hope that this guide will assist you in maternity obstetrical care medical billing and coding for your practice. For more details on specific services and codes, see below.

Table of Contents

The Global Obstetrical Package

When discussing maternity obstetrical care medical billing, it is crucial to understand the Global Obstetrical Package .

Most insurance carriers like Blue Cross Blue Shield, United Healthcare, and Aetna reimburses providers based on the global maternity codes for services provided during the maternity period for uncomplicated pregnancies.

Currently, global obstetrical care is defined by the AMA CPT as “uncomplicated maternity cases which include antepartum, delivery, and postpartum care.” (Source: AMA CPT codebook 2024, page 450.)

If the services rendered do not meet the requirements for a total obstetric package, the coder is instructed to use appropriate stand-alone codes. These might include individual evaluation and management codes, antepartum care only, delivery only, postpartum care only, delivery and postpartum care, etc.

When billing for the global obstetrical package code, all services must be provided by one obstetrician, one midwife, or the same physician group practice provides all the patient’s routine obstetric care, which includes the antepartum care, delivery, and postpartum care.

Here a “physician group practice” is defined as a clinic or obstetric clinic that is under the same tax ID number . It uses either an electronic health record (EHR) or one hard-copy patient record. Each physician, nurse practitioner, or nurse midwife seeing that patient has access to the same patient record and makes entries into the record as services occur.

Individual Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes should not be billed to report maternity visits unless the patient presents for issues outside the global package for commercial payers.

All prenatal care is considered part of the global reimbursement and is not reimbursed separately. The provider will receive one payment for the entire care based on the CPT code billed

Services Bundled with the Global Obstetrical Package

A key part of maternity obstetrical care medical billing is understanding what is and is not included in the Global Package.

Services provided to patients as part of the Global Package fall in one of three categories. They are:

- Antepartum care: Care given from conception, up to (not including) the delivery of the fetus.

- Intrapartum care: Inpatient care of the passage of the fetus and placenta from the womb.

- Postpartum care: Care of the mother after delivery of the fetus.

Let us look at each category of care in detail.

Antepartum Care

Antepartum care comprises the initial prenatal history and examination, as well as subsequent prenatal history and physical examination. This includes:

- Monthly visits up to 28 weeks of gestation

- Biweekly visits up to 36 weeks of gestation

- Weekly visits from 36 weeks until delivery

- Recording of weight, blood pressures and fetal heart tones

- Routine chemical urinalysis (CPT codes 81000 and 81002)

- Education on breast feeding, lactation and pregnancy (Medicaid patients)

- Exercise consultation or nutrition counseling during pregnancy

IMPORTANT: Any other unrelated visits or services within this time period should be coded separately. Example: patient comes in with the flu for this visit a E/M visit should be used.

Intrapartum Care AKA Labor & Delivery

- Admission to the hospital including history and physical.

- Inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services provided within 24 hours of delivery.

- Management and fetal monitoring of uncomplicated labor

- Administration/induction of intravenous oxytocin (performed by provider not anesthesiologist)

- Insertion of cervical dilator on same date as delivery, placement catheterization or catheter insertion, artificial rupture of membranes

- Removal of cerclage (if removed under anesthesia other than “local” it is a billable procedure)

- Vaginal, cesarean section delivery, delivery of placenta only (the operative report)

Postpartum Care

- Uncomplicated inpatient visits following delivery.

- Repair of first- or second-degree lacerations (for lacerations of the third or fourth degree, see “Services Bundled into Global Obstetrical Package”)

- Simple removal of cerclage (not under anesthesia)

- Routine outpatient E/M services that are provided within 6 weeks of delivery (check insurance guidelines for exact postpartum period)

- Discussion of contraception prior to discharge

- Outpatient postpartum care – Comprehensive office visit

- Educational services, such as breastfeeding, lactation, and basic newborn care

- Uncomplicated treatments and care of nipple problems and/or infection

Services Excluded from the Global Obstetrical Package

Certain maternity obstetrical care procedures are either overly complex and/or not required by every patient. As such, including these procedures in the Global Package would not be appropriate for most patients and providers. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has developed a list of procedures that are excluded from the global package. If the provider performs any of the following procedures during the pregnancy, separate billing should be done as these procedures are not included in the Global Package.

- This confirmatory visit (amenorrhea) would be supported in conjunction with the use of ICD-10-CM diagnosis code Z32.01.

- This is usually done during the first 12 weeks before the ACOG antepartum note is started. Use CPT Category II code 0500F.

- Examples include CBC, liver functions, HIV testing, Blood glucose testing, sexually transmitted disease screening, and antibody screening for Rubella or Hepatitis, etc.

- Maternal or fetal echography procedures

- Depending on the insurance carrier, all subsequent ultrasounds after the first three are considered bundled

- Cerclage, or the insertion of a cervical dilator more than 24 hours from admission.

- External cephalic version (turning of the baby due to malposition)

- Amniocentesis (any method)

- Amnioinfusion

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

- Fetal contraction stress test

- Examples include cardiac problems, neurological problems, diabetes, hypertension, hyperemesis, preterm labor, bronchitis, asthma, and urinary tract infection

- NOTE: These encounters could be office visits, clinic visits, emergency room, or inpatient admission/observation.

- Inpatient E/M services provided more than 24 hours before delivery

- Examples include urinary system, nervous system, cardiovascular, etc.

- Per ACOG coding guidelines, this should be reported using modifier 22 of the CPT code used to bill.

- Contraceptive management services (insertions)

List of CPT Codes

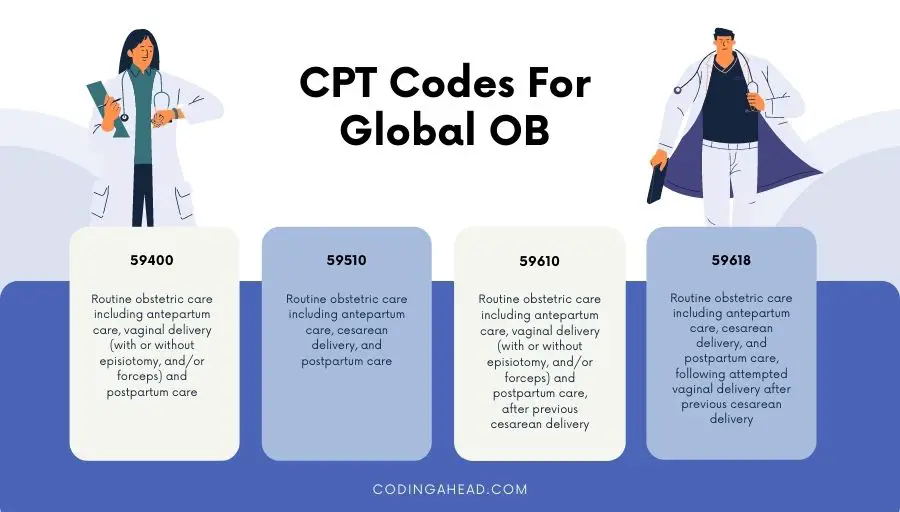

The AMA categorizes Maternity care and delivery CPT codes. The following is a comprehensive list of all CPT codes for full term pregnant women.

IMPORTANT: Complications of pregnancy such as abortion (missed/incomplete) and termination of pregnancy are not included in this list.

The following codes can also be found in the 2024 CPT codebook.

Description

Routine obstetric care including antepartum care, vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy, and/or forceps) and postpartum care, after previous cesarean delivery

Global Package Code Vaginal Delivery

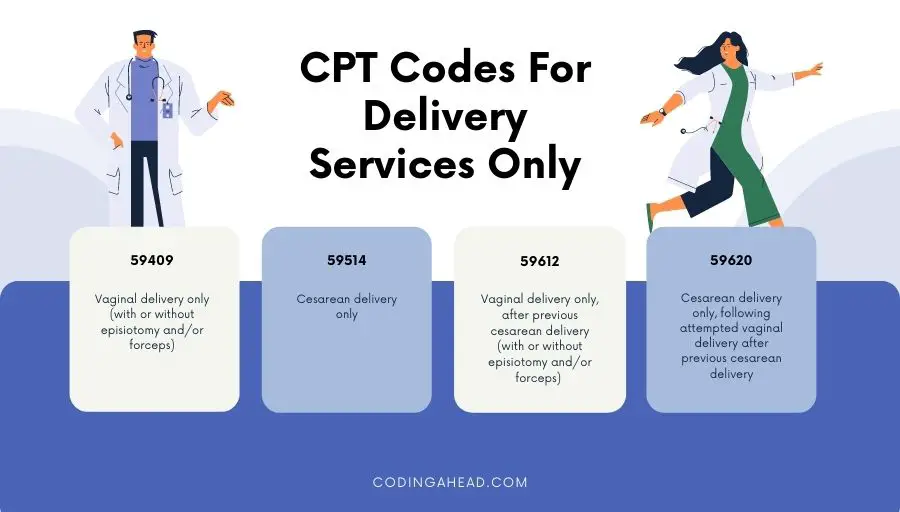

Vaginal delivery only (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps);

Itemization Code

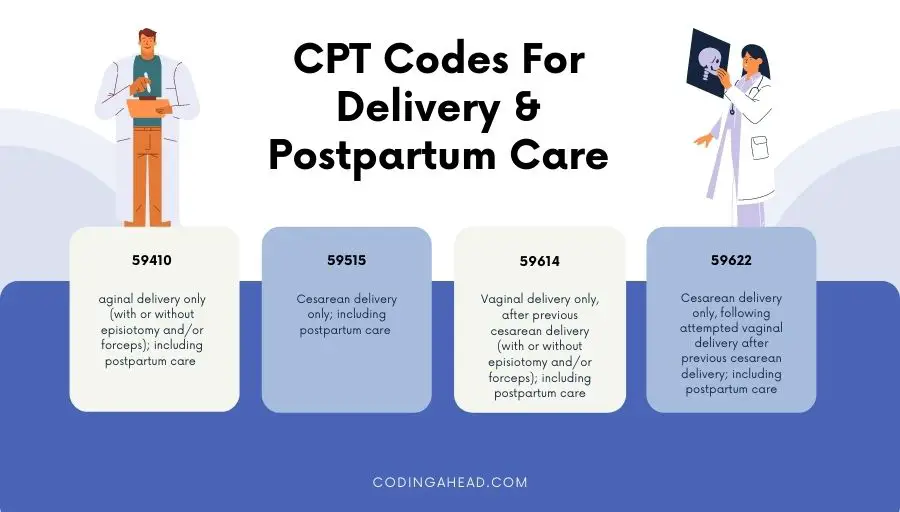

Vaginal delivery only (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps); including postpartum care

Antepartum care only; 1-3 visits

Antepartum care only; 4-6 visits

Antepartum care only; 7 or more visits

Postpartum care only (separate procedure)

Routine obstetric care including antepartum care, cesarean delivery, and postpartum care

Global Package Code C-Section Delivery

Cesarean delivery only;

Cesarean delivery only; including postpartum care

Global Package Code VBAC Delivery

Vaginal delivery only, after previous cesarean delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps);

Vaginal delivery only, after previous cesarean delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps); including postpartum care

Routine obstetric care including antepartum care, cesarean delivery, and postpartum care, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery

Cesarean delivery only, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery;

Cesarean delivery only, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery; including postpartum care

Maternity Obstetrical Care Medical Billing for Twin Delivery/Multiple Gestation

Some pregnant patients who come to your practice may be carrying more than one fetus. In such cases, certain additional CPT codes must be used.

ACOG has provided the following coding guidelines for vaginal, cesarean section, or a combination of vaginal and cesarean section deliveries.

To ensure accurate maternity obstetrical care medical billing and timely reimbursements for work performed, make sure your practice reports the proper CPT codes.

Type of Service/Procedure

Type of twin, cpt codes reported.

Vaginal Delivery of Twins

C-Section Delivery of Twins

Twin A & Twin B

Repeat Cesarean Delivery

Delivery of Twins

VBAC Delivery of Twins

Vaginal & C-Section Delivery of Twins

VBAC + repeat Cesarean Delivery of Twins

If both twins are delivered via cesarean delivery, report code 59510 (routine obstetric care including antepartum care, cesarean delivery, and postpartum care). This is because only one cesarean delivery is performed in this case.

However, if the cesarean delivery is significantly more difficult, append modifier 22 to code 59510. When reporting modifier 22 with 59510, a copy of the operative report should be submitted to the insurance carrier with the claim.

Split Care Performed/Itemization Billing

Some patients may come to your practice late in their pregnancy. Others may elope from your practice before receiving the full maternal care package. In such cases, your practice will have to split the services that were performed and bill them out as is. Examples of situations include:

- The patient has received part of her antenatal care somewhere else (e.g. from another group practice).

- The patient leaves her care with your group practice before the global OB care is complete.

- Patient receives care from a midwife but later requires MD-level care.

- The patient has a change of insurer during her pregnancy.

In these situations, your practice should contact the insurance carrier and notify them of these changes. This will allow reimbursement for services rendered . If the patient has fewer than 13 encounters with the provider, your practice should contact the insurer to find out whether the insurer will honor the global package CPT code. Billings include:

- 59425: Antepartum care only, 4-6 visits

- 59426: Antepartum care only, 7 or more visits; E/M visit if only providing 1-3 visits

- Delivery only: CPT codes 59409, 59514, 59612, and 59620

- Postpartum care only: CPT code 59430

Maternity Obstetrical Care Medical Billing for High-Risk Pregnancies

In the case of a high-risk pregnancy, the mother and/or baby may be at increased risk of health problems before, during, or after delivery. In this case, special monitoring or care throughout pregnancy is needed, which may require more than 13 prenatal visits.

Examples of high-risk pregnancy may include:

- Advanced maternal age: pregnancy risks rise for mothers past the age of 35.

- Maternal health problems: pre-gestation medical complication such as hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, thyroid disease, heart or blood disorders, poorly controlled asthma, and infections can increase pregnancy risk.

- Pregnancy-Related Complications: examples include gestation, diabetes and/or hypertension, poor fetal growth, premature rupture of membrane, abnormal placenta position, etc.

All these conditions require a higher and closer degree of patient care than a patient with an uncomplicated pregnancy.

As such, visits for a high-risk pregnancy are not considered routine. They should be reported in addition to the global OB CPT codes of 59400, 59510, 59610 or 59618.

If medical necessity is met, the provider may report additional E/M codes, along with modifier 25, to indicate that care provided is significant and separate from routine antepartum care. The claim should be submitted with an appropriate high-risk or complicated diagnosis code.

Examples of applicable ICD-10-CM codes:

Supervision of other high-risk pregnancies

Pre-existing hypertensive heart disease complicating pregnancy

Pre-existing hypertension with pre-eclampsia

Gestational [pregnancy-induced] edema and proteinuria without hypertension

Pre-eclampsia

Pre-existing type-1 diabetes mellitus, in pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium

Liver and biliary tract disorders in pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium

Anemia complicating pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium

NOTE: When a patient who is considered high risk during her pregnancy has an uncomplicated delivery with no special monitoring or other activities, it should be coded as a normal delivery according to ICD-10-CM guidelines.

Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) Care

Maternal-fetal medicine specialists, also known as perinatologists , are physicians who subspecialize within the field of obstetrics. They focus on managing the health concerns of the mother and fetus prior to, during, and shortly after pregnancy.

Per ACOG, all services rendered by MFM are outside the global package. Unless the patient sees the provider during their entire pregnancy then a global package is appropriate . An MFM is allowed to bill for E/M services along with any procedures performed (such as ultrasounds, fetal doppler, etc.) with a modifier 25.

Make sure you double check all insurance guidelines to see how MFM services should be reported if the provider and MFM are within the same group practice.

Ultrasound Billing

When reporting ultrasound procedures, it is crucial to adhere closely to maternity obstetrical care medical billing and coding guidelines.

It is necessary to keep a written report from the provider and have images stored on file . As per AMA CPT and ultrasound documentation requirements, image retention is mandatory for all diagnostic and procedure guidance ultrasounds.

Appropriate image(s) and reports demonstrating relevant anatomy/pathology for each procedure coded should be retained and available for review. CPT does not specify how the images should be stored or how many images are required . However, in your documentation the provider should document where to find the images and report.

Modifiers may be applicable if there is more than one fetus and multiple distinct procedures performed at the same encounter. Incorrectly reporting the modifier will cause the claim line to be denied.

The following CPT codes cover ranges of several types of ultrasound recordings that might be performed. Make sure your practice follows correct guidelines for reporting each CPT code.

- 76801–76810: maternal and fetal evaluation (transabdominal approach, by trimester)

- 76811–76812: above and detailed fetal anatomical evaluation

- 76813–76814: fetal nuchal translucency measurement

- 76815: limited trans-abdominal ultrasound study

- 76816: follow-up trans-abdominal ultrasound study

- 76817: trans-vaginal ultrasound study

- 76818–76819: fetal biophysical profile

- 59025: fetal non-stress test

It is essential to read all the parenthetical guidelines that instruct the coder on how to properly bill the service for multiple gestations and more than one type of ultrasound.

Trimesters of Pregnancy

- 1 st trimester: less than 14 weeks 0 days

- 2 nd trimester: 14 weeks 0 days, to less than 28 weeks 0 days

- 3 rd trimester: 28 weeks 0 days, to delivery

NOTE: For ICD-10-CM reporting purposes, an additional code from category Z3A.- (weeks of gestation) should ALWAYS be reported to identify the specific week of pregnancy. (e.g., 15-week gestation is reported by Z3A.15).

Diagnosis Codes for Deliveries and Related Services

- Reporting Routine Prenatal Visits: routine prenatal visits are reported with a code from category Z34.- It should always be the first-listed diagnosis code unless the patient has other medical conditions affecting the pregnancy. Note that Z34.- codes should never be reported with an O code.

- Outcome of Delivery: should be included when a delivery has occurred (ICD-10-CM Z37.-).

- If O80 is not appropriate, the primary diagnosis should reflect the main circumstances or complications of the delivery.

- If the patient is admitted with condition resulting in cesarean, then that is the primary diagnosis.

- If admitted for other reason, the admitting diagnosis is primary for admission and reason for cesarean linked to delivery.

- If multiple conditions prompted the admission, sequence the one most related to the delivery as the principal diagnosis.

- O Codes: An O code from ICD-10-CM Chapter 15 – “Pregnancy, Childbirth & the Puerperium” should always be reported for the delivery when the patient has experienced any current complication in the antepartum period, during the delivery, or in the postpartum period.

- All conditions treated or monitored can be reported (e.g., gestation diabetes, pre-eclampsia, prior C-section, anemia, GBS, etc.)

Who Is Eligible to Provide Patient Care?

The following is a comprehensive list of eligible providers of patient care (with the exception of residents, who are not billable providers):

- Obstetrician, Maternal Fetal Specialist, Fellow

- Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM)

- Nurse Practitioner Midwife (NPM)

- Certified Professional Midwife (CPM)

Depending on your state and insurance carrier (Medicaid), there may be additional modifiers necessary to report depending on the weeks of gestation in which patient delivered. Before completing maternity obstetrical care billing and coding, always make sure that the latest OB guidelines are retrieved from the insurance carrier to avoid denials or short pay.

To ensure proper maternity obstetrical care medical billing, it is critical to look at the entire nine months of work performed to properly assign codes.

Pay special attention to the Global OB Package. The coder should have access to the entire medical record (initial visit, antepartum progress notes, hospital admission note, intrapartum notes, delivery report, and postpartum progress note) to review what should be coded outside the global package and what can be bundled in the Global Package.

The key is to remember to follow the CPT guidelines, correctly append diagnoses, and ensure physician documentation of the antepartum, delivery and postpartum care and amend modifier(s).

At Neolytix , we’re here to support your practice with medical billing services for OBGYN , coding, EMR templates, and more.

Reach out to us anytime for a free consultation by completing the form below.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Coding for Postpartum Services (The Fourth Trimester)

Stanford Children’s Help

- Fetal Ultrasound

- From Antepartum to Postpartum

Get Help with Billing, Credentialing, & Virtual Assistants - Work With A Team of Experts

- Your Name First Last

- Name of the Practice * Practice Name

- Text Message

- By entering your number, you agree to receive mobile messages, Message frequency disclosure, ‘Text HELP for help’, ‘Text STOP to cancel’, Message pricing disclosure and carrier disclosure 'Carriers are not liable for delayed or undelivered messages

- Specialty *

- EHR system being used What EHR are you using to bill claims to Insurance companies, store patient notes.

- <$50,000

- $50,000- $250,000

- $250,000-$1,000,000

- $1,000,000-$5,000,000

- >$5,000,000

- What State(s) do you operate in?

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Popular Posts

Transform Your Financial Strategy with Outsourced Hospital Billing Services

How Automated Claims Processing Speeds Up Reimbursements?

The Impact of RPA on Healthcare Operations with Practical Use Cases

Revolutionizing Healthcare Efficiency: The Benefits and Key Features of Automation in Medical Billing

How Skilled Nursing Facilities Can Thrive After New CMS Regulations

Mastering Downcoding in Medical Billing: Strategies for Healthcare Providers

Posts by category.

- All Posts (157)

- Billing & Coding Guides

- Covid Impact

- Credentialing

- Freelancing

- Healthcare Automation

- Healthcare Recruitment

- Medical Billing

- Medical Licensing

- Medical Virtual Assistant

- Medicare Chronic Care Management

- Press Release

- Remote Patient Monitoring

- Revenue Cycle Management

- Uncategorized

Stay ahead of the curve & join our provider community to get updated on the latest industry trends.

Newsletter (active).

- Why work with us

- Job Openings

- HOSPITALS & HCO'S

- Revenue Transformation

- Value Based Care Programs

- Patient Access

- Coding Audits

- CLINICS & MULTI PROVIDER GROUPS

- Virtual Assistant Services

- Payor Contract Negotiation

- Credentialing & Maintenance

- Website & Marketing

- F&A Services

- Recruitment Outsourcing

- NEWS & RESOURCES

- Neo News Hub

Request A Quote

Get your free intuitive, fast facts for maternity obstetrical care coding flash guide now.

An OB/GYN Coding Cheat Sheet to Make Your Billing Process Easier

Melanie Graham

It seems the world of medical billing gets more complicated every year, doesn’t it? The intricacies of coding can be particularly complex — especially in the obstetrics and gynecology field.

While OB/GYN medical billing may be a lot to manage, having a solid understanding of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes influences one critical piece of your practice: getting paid.

Unfortunately, changes to these codes and their interpretation can be challenging to track. Having an OB/GYN billing cheat sheet (like the one below) and a solid medical billing software partnership can help.

What Is a CPT Code?

A CPT code, or Current Procedural Terminology code , is a number that corresponds with a particular medical service or procedure. CPT codes are a standardized system and a way for payers and insurers to speak the same language about medical services. Providers submit claims with these CPT codes to receive payment from insurers.

In general, OB billing codes range from 56405 to 59899, but you may use other codes outside that range for routine gynecologic care and well-woman visits.

>> Claim Scrubbing: What it Is and Why It’s Important

OB/GYN Coding Cheat Sheet

Keeping track of OB/GYN CPT codes and billing best practices is far from easy. We’ve put together this cheat sheet with a few basics for OB/GYN billing. You can download the full cheat sheet with CPT codes here or check out a short preview below.

OB Billing and Coding Best Practices

OB coding can certainly cause some headaches, but remembering a few key essentials will help you with more accurate claims:

- Make sure you understand the payer’s billing guidelines for deliveries, antepartum care and global codes. Every plan is different. For example, Medicaid HMO plans require you to bill for deliveries with non-standard codes.

- Create an “OB contract” for patients to pay their portion of the delivery claim before delivery. Patients will have a lot of medical bills from the delivery experience. They’ll have a better sense of security and overall experience with price transparency, up-front estimates and the option to make payments before delivery.

- Use global codes for maternity care. Avoid billing separately for services already included in these codes.

- Don’t forget to use separate E/M codes when appropriate. You can use these codes for services that aren’t related to maternity care

Get more best practices in our full OB/GYN Coding Cheat Sheet.

Global Codes for OB/GYN Billing

You’ll notice that we’ve outlined some maternity care global codes in this OB/GYN billing cheat sheet. You can use these codes when the same physician or physician group provides all maternity services for a patient.

OB global codes include 59400, 59510, 59610 and 59618. These include all care from antepartum through delivery and postpartum care.

- 59400 – Routine obstetric care for vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps), including antepartum and postpartum care.

- 59510 – Routine obstetric care for cesarean section delivery, including antepartum and postpartum care.

- 59610 – Routine obstetric care for vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps) after cesarean delivery, including antepartum and postpartum care.

- 59618 – Routine obstetric care for cesarean delivery following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery, including antepartum and postpartum care.

It’s important to note when you use a global code, you can’t bill separate evaluation and management (E/M) codes for individual parts of maternity care. However, you can bill separately if the mother’s insurance coverage changes during the pregnancy or if another physician cares for the mother before you complete all the services in the global code.

You can also separately bill the initial visit to confirm pregnancy.

You can bill E/M codes if the mother seeks care for a problem not related to her pregnancy, such as treatment for a yeast infection or a postpartum discussion about birth control. You will also bill separate codes for most lab tests you do during the pregnancy.

Gynecology Coding Best Practices

If you’re working on the ‘GYN’ side of OB/GYN, there are other best practices you’ll need to keep in mind.

Hysterectomies

A hysterectomy is surgery to remove the uterus. Although this procedure may sound relatively straightforward, there are some unique coding and billing best practices to keep in mind:

- The approach to the surgery will determine the CPT code. There are three main approaches: abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic.

- The weight of the uterus can also influence which CPT code you should use.

- The extent of the surgery (how much of the uterus is removed) may influence which CPT code you should use.

- Some CPT codes factor in additional services or procedures with the hysterectomy.

- Abdominal hysterectomy codes range between 58150 and 58210.

- Vaginal hysterectomy codes range between 58260 and 58291.

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy codes range between 58541 and 58573.

Well-Woman Visits

Well-woman exams are yearly check-ups women have with their OB/GYN. These appointments can include a general health screening as well as cervical cancer screening.

It’s important to remember that you’ll code well-woman exams based on two factors: the age of the patient and whether they are a new or returning patient. New patient codes range from 99385-99387 and existing patient codes range from 99395-99397.

What About Modifiers?

OB/GYN CPT codes often include modifiers on the end. Modifiers are two-digit codes that show you’ve somehow altered the service in the original five-digit CPT code. For example, if a woman delivers twins, you may use the “22” modifier to indicate additional or increased services. For a full list of common OB/GYN modifiers, download our coding cheat sheet.

Find a Partner Who Can Modernize Your OB/GYN Billing Process

Efficient and accurate coding is one piece of healthy revenue cycle management and crucial to the success of your OB/GYN practice. So, why waste resources on an outdated, clunky billing process?

With Gentem’s AI-powered revenue cycle management (RCM) platform , you can:

- Easily manage all your OB patients in one spot. This helps you track all your patients and the services you provide, so you’re not leaving money on the table.

- Catch high-deductible patients so you can optimize when to bill your claim.

- Streamline OB/GYN patient estimates, so you can increase up-front payments and improve the patient experience.

Whether you need complete RCM support or state-of-the-art software to boost your medical billing team, we have you covered. Our platform has helped OB/GYN practices achieve record collections , allowing them to expand staff and care for more patients.

Learn more about our powerful RCM and billing tools by booking a demo today .

Increase Revenue & Collection Rates

Gentem’s tech platform and team of billing experts increase practice revenue by an average of 20%.

WATCH: Revenue Cycle Tips for Staying Independent

Many physicians are leaving private practice due to rising costs, lower reimbursement rates and staffing shortages. But staying independent is possible with a healthy revenue cycle.

Learn how to run a successful private practice with tips from this 20-minute webinar session.

5 Must-Know Metrics To Build A Thriving Medical Practice

With this free guide, you’ll learn the key metrics that inform your practice’s financial performance and how best to optimize them to support practice growth.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Related articles.

What Is Healthcare Revenue Cycle Management (RCM)?

Revenue Cycle KPI Glossary: Definitions and Benchmarks You Should Know

7 Ways to Prevent Medicaid Claim Denials

Eliminate your medical billing headaches today..

Ob/Gyn Coding Guidelines 2023

Obstetrics and Gynaecology / Maternity care services; 1. Antepartum care 2. Delivery services 3. Postpartum care The two types of OB coding & billing guidelines are given below, 1. Global OB Care 2. Non-global OB care or partial services

Global OB Care

The total obstetric care package includes antepartum care, delivery services, and postpartum care. When the same group physician and/or other health care professional provides all components of the OB package, report the Global OB package code.

CPT Codes For Global OB

CPT code 59400 – Routine obstetric care, including antepartum care, vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy, and/or forceps) and postpartum care.

CPT code 59510 – Routine obstetric care, including antepartum care, cesarean delivery , and postpartum care. CPT code 59610 – Routine obstetric care, including antepartum care, vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy and forceps), and postpartum care after previous cesarean delivery. CPT code 59618 – Routine obstetric care, including antepartum care, cesarean delivery, and postpartum care, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery.

OB Global Billing Guidelines

The global maternity allowance is a complete, one-time billing that includes all professional services for routine antepartum care, delivery services, and postpartum care. The fee is reimbursed to one provider for all of the member’s obstetric care. If the member is seen four or more times before delivery for prenatal care and the provider performs the delivery and postpartum care, the provider must bill the Global OB code. Global maternity billing ends with the release of care within 42 days after delivery. Global OB care should be billed after the delivery date/on delivery date.

Services Included In Global Obstetrical Package

- Routine prenatal visits until delivery, after the first three antepartum visits.

- Recording of weight, blood pressure, and fetal heart tones.

- Admission to the hospital, including history and physical.

- Inpatient Evaluation and Management (E/M) service is provided within 24 hours of delivery.

- Management of uncomplicated labor.

- Vaginal or cesarean section delivery.

- Delivery of placenta ( CPT code 59414 ).

- Administration/induction of intravenous oxytocin (CPT code 96365-96367).

- Insertion of a cervical dilator on the same date as delivery ( CPT code 59200 ).

- Repair of first or second-degree lacerations.

- A simple removal of cerclage (not under anesthesia).

- Uncomplicated inpatient visits following delivery

- Routine outpatient E/M services are provided within 42 days following delivery.

- Postpartum care after vaginal or cesarean section delivery ( CPT code 59430 ).

The above services are not reimbursed when reported separately from the global OB code. As per ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) coding guidelines, reporting of third and fourth-degree lacerations should be identified by appending modifier 22 to the global OB code (CPT codes 59400 and 59610) or delivery only code (CPT codes 59409 , 59410 , 59612 and 59614 ).

Claims submitted with modifier 22 must include medical record documentation supporting the modifier’s use.

Services Excluded From The Global Obstetrical Package

The following services are excluded from the global OB package (CPT codes 59400, 59510, 59610, 59618) and may be reported separately.

- First three antepartum E&M visits

- Laboratory tests

- Maternal or fetal echography procedures (CPT codes 76801 , 76802 , 76805 , 76810 , 76811 , 76812 , 76813 , 76814 , 76815 , 76816 , 76817 , 76820 , 76821 , 76825 , 76826 , 76827 and 76828 )

- Amniocentesis, any method (CPT codes 59000 or 59001 )

- Amniofusion ( CPT code 59070 )

- Chorionic villus sampling ( CPT code 59015 )

- Fetal contraction stress test ( CPT code 59020 )

- Fetal non-stress test ( CPT code 59025 )

- External cephalic version ( CPT code 59412 )

- Insertion of cervical dilator (CPT code 59200) more than 24 hours before delivery

- E&M services unrelated to the pregnancy (e.g., UTI , Asthma) during antepartum or postpartum care.

- Additional E/M visits for complications or high-risk monitoring resulted in greater than 13 antepartum visits. However, these E/M services should not be reported until the patient delivers. Append modifier 25 to identify these visits separately from routine antepartum visits.

- Inpatient E/M services are provided more than 24 hours before delivery

- Management of surgical problems arising during pregnancy (e.g., Cholecystectomy , appendicitis, ruptured uterus)

Non-global OB Care, Or Partial Services

Non-global OB care, or partial services, refers to maternity care not managed by a single provider or group practice.

Billing for non-global OB or Partial care may occur if,

- A patient transfers into or out of a physician or group practice

- A patient is referred to another physician during her pregnancy

- A patient has the delivery performed by another physician or other health care professional not associated with her physician or group practice

- A patient terminates or miscarries her pregnancy

- A patient changes insurers during her pregnancy

The physician provides only partial services instead of global OB care To bill for that portion of maternity care only. Use the codes below for billing antepartum-only, postpartum-only, delivery-only, or delivery and postpartum-only services. Only one of the following options should be used, not a combination.

A. Antepartum Care Only

For 1 to 3 visits: Use E/M office visit codes.

For 4 to 6 visits: Use CPT 59425 ; this code must not be billed by the same provider in conjunction with one to three office visits or in conjunction with code 59426.

For seven or more visits: Use CPT 59426 – Complete antepartum care is limited to one beneficiary pregnancy per provider.

Billing Guidelines Of Antepartum Care Only

Suppose the patient is treated for antepartum services only. In that case, the physician should use CPT code 59426 if seven or more visits are provided, CPT code 59427 if 4-6 visits are provided, or each E/M visit if only providing 1-3 visits. As per ACOG and AMA guidelines, The antepartum care only codes 59425 or 59426 should be reported as described below,

A single claim submission of CPT code 59425 or 59426 for the antepartum care only, excluding the confirmatory visit that may be reported and separately reimbursed when the antepartum record has not been initiated.

The units reported should be one.

The dates reported should be the range of time covered,

E.g., If the patient had a total of 4-6 antepartum visits,, the physician should report CPT code 59425 with the from and to dates for which the services occurred.

CPT 59425 and 59426 – These codes must not be billed together by the same provider for the same beneficiary during the same pregnancy.

Pregnancy-related E/M office visits must not be billed with code 59425 or 59426 by the same provider for the same beneficiary during the same pregnancy.

B. Delivery Services Only

The following are the CPT codes for delivery services only: CPT code 59409 – Vaginal delivery only (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps) CPT code 59514 – Cesarean delivery only CPT code 59612 – Vaginal delivery only, after previous cesarean delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps) CPT code 59620 – Cesarean delivery only, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery The delivery-only codes should be reported by the same group physician for a single gestation when,

The same physician or group practice does not provide the total OB package to the patient.

Only the delivery component of the maternity care is provided, and another physician or group of physicians performs the postpartum care.

Services Included In The Delivery Services

As CPT and ACOG guidelines, the following services are included in the delivery services codes and shouldn’t be reported separately.

- Admission to the hospital,

- The admission history and physical examination,

- Management of uncomplicated labor, vaginal delivery (with or without episiotomy, with or without forceps), or cesarean delivery, external and internal fetal monitoring provided by the attending physician

- Intravenous induction of labor via oxytocin (CPT code 96365-96367)

- Delivery of the placenta, any method

- Repair of first or second-degree lacerations

- Insertion of cervical dilator ( CPT 59200 ) to be included if performed on the same delivery date.

Billing Guidelines Of Delivery Services Only

Reporting of third and fourth-degree lacerations should be identified by appending modifier 22 to the global OB code (CPT codes 59400 and 59610) or delivery-only code (CPT codes 59409, 59410, 59612, and 59614) Claims submitted with modifier 22 must include medical record documentation supporting the modifier’s use.

C. Delivery Only, Including Postpartum Care

Suppose the same individual or same group physician provided the delivery care and postpartum care; in these instances, few CPT codes encompass both of these services. In that case, The following are CPT-defined delivery and postpartum care. CPT code 59410 – Vaginal delivery only (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps), including postpartum care CPT code 59515 – Cesarean delivery only; including postpartum care CPT code 59614 – Vaginal delivery only, after previous cesarean delivery (with or without episiotomy and/or forceps); including postpartum care CPT code 59622 – Cesarean delivery only, following attempted vaginal delivery after previous cesarean delivery; including postpartum care

Services Included In The Delivery Only Including Postpartum Care Services

- Hospital visits related to the delivery during the delivery confinement

- Uncomplicated outpatient visits related to the pregnancy

- Discussion of contraception

D. Postpartum Care Only

The following is the CPT-defined postpartum care only, CPT 59430 – Postpartum care only (separate procedure)

Services Included In The Postpartum Care

- Uncomplicated outpatient visits related to the pregnancy

Services Excluded In The Postpartum Care

- E/M of problems or complications related to the pregnancy

Billing Guidelines For Postpartum Care Only

Postpartum care should only be reported by the same group physician who provides the patient with services of postpartum care only. Suppose a physician provides any component of antepartum along with postpartum care but does not perform the delivery. In that case, the services should be itemized using the appropriate counterpart and postpartum care codes.

Similar Posts

Evaluation and Management Documentation Guidelines for Teaching Physicians

For a given encounter, the selection of the appropriate level of E/M services is determined according to the code of definitions in CPT books and any applicable documentation guidelines. CPT books are available from the American Medical Association. When a Teaching Physician bills for E/M services, he or she must personally document at least the…

MEDICAL TERMS

Medical Terms that are commonly found in patient medical recordsAnterior: Situated on the front surface of the body; ventral.Bilateral: On both sides, having two sides.Caudal: Denoting the lower half of the body; inferior.Contraction: A shortening and/or tensioning of muscle tissue.Coronal: Pertaining to an imaginary longitudinal plane at right angle to the medial plane and dividing…

Immediate Recoupment for Fee for Service Claims Overpayments

Effective July 1, 2012, The “immediate recoupment” process implemention allows providers to request that recoupment begin prior to day 41. Providers who elect this option may avoid paying interest if the overpayment is recouped in full prior to day 31. Key to understanding this change is that providers who request an immediate recoupment must realize it is considered…

Primary Care Incentive Payment Program (PCIP)

According to Section 5501(a) of the Affordable Care Act the Primary Care Physicians (PCP) and NPPs who furnish specified primary care services will receive 10 percent of incentive payment for the services rendered on or after January 1, 2011 and continuing through December 31, 2015 Eligibility of New Providers for Payment under PCIP For primary…

Payment for Physician Services in Teaching Settings

Services furnished in teaching settings are paid through the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) if the services are: • Personally furnished by a physician who is not a resident; • Furnished by a resident when a teaching physician is physically present during the critical or key portions of the service; or • Furnished by a…

UHC coverage for Gardasil vaccine

CPT code 90649 – Human Papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine, types 6, 11, 16, 18 (quadrivalent), 3 dose schedule, for intramuscular use HPV4 vaccine is recommended for routine vaccination in males aged 11 or 12 years. ACIP has also recommended vaccination with HPV4 for males aged 13 through 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Newsletters

HCPro, JustCoding Outpatient - 2021 Issue 32 (August)

Outpatient pregnancy primer: coding prenatal care.

August 23rd, 2021

To select the most specific CPT codes for prenatal care, physician coders must have a solid understanding of complex guidelines for reporting pregnancy-related office visits. Lori-Lynne A. Webb, CPC, CCS-P, CCP, CHDA, COBGC , unpacks services included in the global obstetric package and CPT coding for routine prenatal care.

To read the full article, sign in and subscribe to the JustCoding Newsletters.

Thank you for choosing Find-A-Code, please Sign In to remove ads.

Prenatal Care Provided by Primary Care Physicians

- Clinical Policy Bulletins

- Medical Clinical Policy Bulletins

Number: 0047

Table Of Contents

Many family physicians in our network are trained and qualified to provide obstetric care. This policy will assure high-quality prenatal care for Aetna members while allowing family physicians the opportunity to continue their care through the 27th week of pregnancy.

The above policy is based on the following references:

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). AAFP--ACOG joint statement of cooperative practice and hospital privileges. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(1):277-278.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Maternity and gynecologic care. Recommended core educational guidelines for family practice residents. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(1):275-277.

- Mengel MB, Phillips WR. The quality of obstetric care in family practice: Are family physicians as safe as obstetricians? J Fam Pract. 1987;24(2):159-164.

Policy History

Effective: 10/31/1995

Next Review: 01/09/2025

Review History

Definitions

Additional Information

Clinical Policy Bulletin Notes

You are now leaving the Aetna website .

Links to various non-Aetna sites are provided for your convenience only. Aetna Inc. and its subsidiary companies are not responsible or liable for the content, accuracy, or privacy practices of linked sites, or for products or services described on these sites.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Johns Hopkins Health Plans

Ppc - prenatal and postpartum care.

Product Lines: EHP, Priority Partners, and USFHP. Eligible Population: Women who had a live birth(s) on or between 10/8 year prior to the MY and 10/7 of the MY (10/8/2023 -10/7/2024). This includes Value Based Purchasing (VBP) for Priority Partners. Definition: The percentage of live birth deliveries on or between October 8 of the year prior to the measurement year and October 7 of the measurement year. For these women, the measure assesses the following:

- Timeliness of Prenatal Care: A prenatal care visit in the first trimester or within 42 days of enrollment in the health plan.

- Postpartum Care: A postpartum visit on or between 7 and 84 days after delivery.

Provider Specialty: PCP, OB/GYN, Prenatal Care Provider

- Services provided during a telephone visit, e-visit or virtual check-in are acceptable for prenatal and postpartum care.

- Birth is considered a live birth if delivered twin and one was stillborn.

- Can appear twice in the measure if two separate pregnancies during time frame.

Report stratification by race and ethnicity.

Continuous Enrollment:

- 43 days prior to delivery through 60 days after delivery.

Best Practice and Measure Tips

- The system uses the delivery date to calculate the prenatal timeframe and assumes a full term pregnancy. Members who deliver early may not be compliant and may require the EDD to be updated based on an EDD in an ultrasound report. LMP cannot be used to adjust the EDD.

- Provide education to members on importance of prenatal and postpartum care for them and their baby.

- Follow members closely who have or had a substance abuse or mental health diagnosis. Initiate appropriate referrals.

- Identify potential barriers to receiving care when pregnancy is confirmed. Discuss with members ways barriers can be overcome.

- Ensure members are aware of available resources to overcome barriers and any incentives for care.

- Identify members seen in ER with a diagnosis of pregnancy and initiate follow-up.

- For members who do not show or schedule appointments, attempt to engage in a telephone or video visit to close gap.

- Before discharging member from the hospital stay, look at the member’s schedule history for no show or reschedule appointment and if member seems reluctant to schedule an appointment or you suspect they will not show, schedule a telephone or video visit.

- Maintain available appointments for member to be seen during their first trimester or postpartum period.

- When scheduling Postpartum visit, use the discharge day and schedule the member after the 6th day from discharge which begins the postpartum period for the measure (within 7-84 days postpartum).

- Use appropriate and accurate codes on claims.

- CPT Category II helps identify clinical outcomes

- Reduce the need for some chart review

Prenatal Care with visit date and one of the following:

- A diagnosis of pregnancy (this must be included for PCP visits). Such as: visit to confirm pregnancy or pregnancy was diagnosed.

- Standardized prenatal flow sheet, LMP, EDD, gestational age, gravidity and parity, notation of positive pregnancy test result, complete OB history, of prenatal risk assessment and counseling

- A basic physical obstetrical examination with auscultation for fetal heart tone, pelvic exam, obstetric observations, or measurement of fundus height.

- Screening test in the form of an obstetric panel (must include all of the following: hematocrit, differential WBC count, platelet count, hepatitis B surface antigen, rubella antibody, syphilis test, RBC antibody screen, Rh and ABO blood typing), OR

- TORCH antibody panel, OR

- Rubella antibody test/titer with RH incompatibility (ABO/Rh) blood typing, OR

- Ultrasound of a pregnant uterus.

Acceptable :

- May utilize ACOG sheet or a standardized prenatal flow sheet.

- Services provided during a telephone visit, e-visit or virtual check-in.

Not acceptable:

- Ultrasound and lab results not combined with an office visit.

- A visit or documentation with a RN alone. It must be associated with appropriate provider's note.

- A Pap test does not count as a prenatal care visit.

Postpartum with visit date and one of the following:

- Notation of PP care,( including, but not limited to: "postpartum care," "PP care," PP check," 6-week check."(Alone will make member compliant)

- Assessment of breasts or breast feeding, weight, BP check and abdomen (breast feeding is acceptable for evaluation of breasts)

- Perineal or cesarean incision/ wound check

- Screening for depression, anxiety, tobacco use, substance use disorder, or preexisting mental health disorders

- Pelvic exam-A pap test will count toward PP care as a pelvic exam.

- Glucose screening for member with gestational diabetes.

- Infant care / breastfeeding.

- Resumption of intercourse, birth spacing or family planning.

- Sleep or fatigue.

- Resumption of physical activity.

- Attainment of healthy weight.

Not Acceptable:

- Colposcopy alone.

- Care in an acute inpatient setting.

Measure Exclusions

Required Exclusions:

- Members in hospice or using hospice services anytime during the measurement year.

- Members who died any time during the measurement year.

- Pregnancy did not result in a live birth

- Member not pregnant

- Delivery outside of measure date parameters

Measure Codes

- CPT/CPT II: 99500, 0500F - 05002F

- HCPCS: H1000 - H1004

- CPT: 98966, 98967, 98968, 98970, 98971, 98972, 98980, 98981, 99202-99205, 99211-99215, 99241-99245, 99421-99423, 99457, 99458, 99483

- HCPCS: G0071, G0463, G2010, G2012, G2250, G2251, G2252, T1015**

- NOTE : **T1015 HCPCS code which identifies an all-inclusive clinic visit for services rendered at a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC).

- CPT: 59400, 59425, 59426, 59510, 59610, 59618,

- HCPCS: H1005

- CPT/CPT II: 57170, 58300, 59430, 99501, 0503F

- HCPCS: G0101

- ICD-10-CM: Z01.411, Z01.419, Z01.42, Z30.430, Z39.1, Z39.2

- CPT: 59400, 59410, 59510, 59515, 59610, 59614, 59618, 59622

- CPT: 88141-88143, 88147, 88148, 88150, 88152, 88153, 88164-88167, 88174-88175

- HCPCS: G0123, G0124, G0141, G0143, G0145, G0147-48, P3000, P3001, Q0091

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Who is your prenatal care provider? An algorithm to identify the predominant prenatal care provider with claims data

- Songyuan Deng 1 ,

- Samantha Renaud 1 &

- Kevin J. Bennett 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 665 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Using claims data to identify a predominant prenatal care (PNC) provider is not always straightforward, but it is essential for assessing access, cost, and outcomes. Previous algorithms applied plurality (providing the most visits) and majority (providing majority of visits) to identify the predominant provider in primary care setting, but they lacked visit sequence information. This study proposes an algorithm that includes both PNC frequency and sequence information to identify the predominant provider and estimates the percentage of identified predominant providers. Additionally, differences in travel distances to the predominant and nearest provider are compared.

The dataset used for this study consisted of 108,441 live births and 2,155,076 associated South Carolina Medicaid claims from 2015–2018. Analysis focused on patients who were continuously enrolled throughout their pregnancy and had any PNC visit, resulting in 32,609 pregnancies. PNC visits were identified with diagnosis and procedure codes and specialty within the estimated gestational age.

To classify PNC providers, seven subgroups were created based on PNC frequency and sequence information. The algorithm was developed by considering both the frequency and sequence information. Percentage of identified predominant providers was reported. Chi -square tests were conducted to assess whether the probability of being identified as a predominant provider for a specific subgroup differed from that of the reference group (who provided majority of all PNC). Paired t -tests were used to examine differences in travel distance.

Pregnancies in the sample had an average of 7.86 PNC visits. Fewer than 30% of the sample had an exclusive provider. By applying PNC frequency information, a predominant provider can be identified for 81% of pregnancies. After adding sequential information, a predominant provider can be identified for 92% of pregnancies. Distance was significantly longer for pregnant individuals traveling to the identified predominant provider (an average of 5 miles) than to the nearest provider.

Conclusions

Inclusion of PNC sequential information in the algorithm has increased the proportion of identifiable predominant providers by 11%. Applying this algorithm reveals a longer distance for pregnant individuals travelling to their predominant provider than to the nearest provider.

Peer Review reports

Having a usual source of care has a substantial positive impact on patients and outcomes. Such continuity of care (COC), due to the usual source of care [ 1 , 2 ], is associated with reduced avoidable hospitalization and emergency department visits [ 3 , 4 ], cost reduction [ 4 , 5 ], and reduced probability of mortality [ 6 , 7 ]. Thus, being able to identify a patient’s usual source of care or where they predominantly receive care is important for healthcare resource planning for providers and policymakers.

In the 1990s, algorithms were introduced that identified the most frequently visited providers, known as plurality providers (a provider who provides the most visits), and the majority provider (a provider who provides majority of visits), using claims data. The majority provider is a subset of the plurality provider because a majority provider is by definition a plurality provider, but a plurality provider is not necessarily a majority provider [ 8 , 9 ]. These algorithms used the proportion of visit frequency during a period as well as the specialty of a provider. They have been applied to describe what percentage of care was delivered by an identified predominant provider [ 10 ] and as measures of care coordination [ 11 ]. Recently these algorithms, designed to utilize claims data, have been verified via electronic health records. The results showed that in primary care settings, these algorithms identified the predominant providers for 78–84% of primary care physician visits but only 25–56% for all visits. Due to the fact that the majority provider is a subset of the plurality provider, the plurality algorithm identified the predominant providers for 84% of primary care physician visits, but the majority algorithm identified only 78% [ 12 ].

This plurality algorithm has been applied outside of the primary care setting for patients seeking care for dementia [ 13 ] and for those seeking care for HIV [ 14 ]. Based on this literature review, no study was identified that applied this algorithm to identify the predominant provider for prenatal care (PNC), despite pregnancy complications (47%) and the associated cost [ 15 ]. Furthermore, Kotelchuck proposed the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU) Index specifically for PNC, [ 16 ] which has since been widely adopted. The APNCU index integrated the adequacy of initiation of PNC and the adequacy of received services. Therefore, to identify the predominant provider for PNC, an algorithm needs to include both the PNC visit frequency and sequence information, such as the first and last visits. Such visit sequential information was not included in previously proposed algorithms.

Furthermore, previous algorithms could not identify the predominant providers for 16–25% of the studied population [ 12 ]. Public programs aiming to increase prenatal care access /capacity need provider information to tailor interventions to specific areas. By integrating sequence with frequency information, this study aims to identify more predominant providers than previous algorithms. The increased proportion of identifiable predominant providers can provide supportive information for these public programs.

This study constructed a version of the plurality provider algorithm specifically for PNC by including both the visit frequency and sequence information. This algorithm was applied to pregnant individuals to identify their predominant providers. As PNC frequency varies, different patterns were adopted to compare the final percentage of pregnant individuals whose predominant providers were identified. Finally, this study examined the differences between the travel distance to the nearest visited provider and that to the predominant provider because long distance is one of the main factors that limit access to PNC [ 17 ].

Data and sample

This study utilized deidentified Medicaid claims data from the South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs (SCRFA) Office for 2014–2019. Medical claims were acquired for those who had a live birth during the period 2015–2019 in the 12 months prior to delivery. Vital records were used to identify live births with a parent-baby linkage by the SCRFA office. Exemption for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institute due to the secondary analysis using deidentifiable administrative data.

A total of 108,441 live births, with 2,155,076 associated claims, were found during the 2015–2018 period. Full date of birth (DOB) was not released due to privacy concerns. However, as allowed by our data use agreement, and using previously published algorithms as guidance, [ 18 , 19 ] month of birth was estimated by using the dates of service and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) associated with the claims and appended to SC RFA provided year of birth. Samples were delimited to those who had continuous enrollment in Medicaid for the duration of their pregnancies, resulting in 36,848 pregnancies. Among those, only 32,609 included at least one prenatal care claim in the data. Analyses were conducted at the pregnancy level because the purpose is to identify a predominant provider for each pregnancy episode.

Observed prenatal care

This study employed a series of variables to identify PNC visits from these claims. These variables included date of delivery (month/year); date of services (month/year); primary/secondary diagnosis (ICD 9/10 clinical modification (CM), Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT); and provider specialty.

Office claims dataset was linked to Vital Statistics and hospital claims dataset to construct pregnancy episodes [ 19 ]. Delivery date and services date were used to calculate the duration from each claim to delivery, guided by the previously published algorithm [ 19 ]. Claims within the gestational age were kept. PNC services were identified with procedure code, including CPT and HCPCS code, and primary diagnosis code. Details can be found in Appendix Table 1.

Claims were selected by Medicaid provider specialty and type code, including midwife (06), primary care physician (12,14,19,78), Obstetrics and Gynecology specialist (16, 26, 27), organization (50-FQHC, 97-RHC), nurse practitioner (86), others (02, 10, 40, 48, 57, 94, 95, PA, missing). Specialties that were marked as missing and the supervisor’s specialties of PA (physician assistants) were unknown (0.24%). Although they only accounted for 0.05% of visits, specialties with codes of 02, 10, 40, 48, 57, 94 and 95 were kept for three reasons. First, a coded PNC visit to these specialties satisfies the three criteria of COC [ 20 ]. Second, those specialties may serve as a substitute for a traditional PNC provider given the limited access to PNC providers for some populations [ 21 , 22 ]. Finally, pregnancies diagnosed with hemorrhage during early pregnancy may utilize emergency service (code: 02), those diagnosed with diabetes may consult a diabetes educator (code: 94) for advice on diabetes management during pregnancy, and those diagnosed with depression and anxiety may consult a psychiatrist (code: 48) for medication during pregnancy [ 15 ].

This study integrates PNC initiation, frequency of visits, and sequence of visits to inform the algorithm. Visit frequency at the provider level was then used to estimate the PNC fraction, that is, the percentage of PNC visits to a specific provider, given all PNC visits, for a specific pregnancy. Visit sequences were identified using the date of services. The first and last PNC visits were then confirmed with sequential information. PNC initiation refers to the provider that provided the first visit during the pregnancy. The final PNC visit prior to birth plays a particularly important role in ensuring continuity of care during prenatal, delivery, and postpartum care. Some providers may be affiliated with a hospital and capable of providing delivery-related services, while others may not have appropriate training or not be available to provide delivery services and need to refer their patients to a qualified provider [ 23 ]. The provider visited at the last PNC visit is considered the referrer for delivery. Therefore, the initial and last PNC visits were identified for each pregnancy.

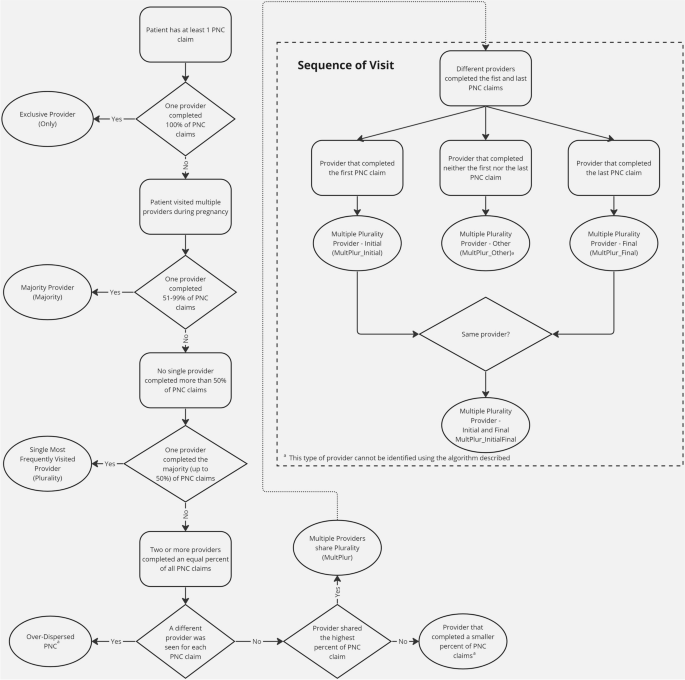

Provider definition

To identify the predominant provider, this study constructed four categories based on the PNC fraction and sequential information: the exclusive provider (Only), the majority provider (Majority), the single most frequently visited (Plurality) providers, and multiple providers sharing plurality (MultPlur). The PNC fraction was used to measure how many visits a provider served for a given pregnancy, calculated by dividing the number of PNC visits from that specific provider by the total number of PNC visits. Only providers are those who are the only visited provider throughout the pregnancy, with a fraction of 100%. Majority providers are those providing more than half of PNC services for a pregnant individual, with a fraction larger than 50%—Majority provider is aligned with the majority algorithm [ 8 ]. Plurality providers are those providing the highest fraction of PNC within all visited provider but less than 50% for a pregnant individual- Plurality provider is aligned with the plurality algorithm [ 9 ]. If there were multiple providers who provided equal fractions of PNC visits to a pregnant individual, they were classified as multiple plurality (MultPlur). Providers who were not classified as any of these categories would not be identified as a predominant provider (Fig. 1 ).

Flowchart of identifying the predominant provider

The data obtained from RFA included a unique provider identifier that may refer to a professional or a provider, whichever is applicable, enabling PNC frequency to be counted at the provider identifier level. Since different professionals may share the same provider identifier, frequency can be more accurately counted by combining specialty with this provider identifier. This study used the specialty-specified provider identifier (SSPI) to denote unique providers and calculate PNC frequency.

Different patterns

This algorithm first counted the PNC frequency at both the pregnancy and provider levels for each pregnancy. The number of PNC providers was also counted for each pregnancy. Every PNC provider was then classified into one of five categories: Only, Majority, Plurality, Multiple Plurality and others. The predominant provider was identified initially as Only through MultPlur providers as shown in Fig. 1 . In the initial pattern, the Only providers were identified as the predominant provider. Both Only and Majority providers were identified as the predominant provider in the second pattern. Beyond Only and Majority providers, Plurality providers were identified as the predominant provider in the third pattern. The multiple plurality providers were further included as the predominant provider in the fourth, fifth and sixth patterns. (see Appendix Table 2) The final group of others, including those provide some but not the largest fraction of PNC and MultPlur providers who provide neither the first nor the last PNC.

As pregnant individuals may utilize additional providers that differ from the initial provider accessed during their pregnancy [ 24 ], different providers may cover different gestation periods for different individuals. For example, some of the most visited providers may serve the early pregnancy period, while others may serve later terms. In the early visit (fourth) pattern, the MultPlur provider which conducts the initial visit is defined as MultPlur_Initial. In the late visit (fifth) pattern, the MultPlur provider that conducts the final visit is defined as MultPlur_Final. In the hybrid (sixth) pattern, the MultPlur provides the initial or the final visits (Fig. 1 ). Therefore, MultPlur providers in different patterns may provide care for different needs. The MultPlur_Initial in the early patternmay be associated with PNC initiation, while the MultPlur_Final in the late scenario may be associated with actual delivery. The MultPlur in the hybrid patternmay be associated with either or both needs. If there is a tie between MultPlur_Initial and MultPlur_Final, this algorithm gave priority to MultPlur_Initial because APNCU listed PNC initiation as one major measurement [ 16 ]. The algorithm developed here will include all three patterns for the MultPlur providers. The percentage of pregnant individuals with a predominant provider was reported for all six patterns.

The percentage of pregnancies with identifiable predominant prenatal care providers by prenatal care frequency were then summarized. Chi-square tests were applied to examine whether there is a difference between each category of providers and Majority providers in being identified as a predominant provider, given the total number of PNC visits.

A special case occurs when a pregnant person visits a different provider at each PNC visit. That means that the number of total visits equals the number of providers. This group is defined as over-dispersed (Fig. 1 ). The dispersed nature of all visits makes the first and last visits contain no meaningful sequential information. The predominant provider cannot be reasonably identified under such a situation. Predominant providers could not be identified for those pregnancies.

Application example with travel distance

The results of this algorithm were then applied to examine travel distance differences between the nearest PNC provider and the identified predominant PNC provider. For simplicity, this was delimited to visits that occurred within the state boundaries. Any provider who delivered at least one PNC service in this study was included in the analysis. Distance was estimated using Google Maps, which calculated the distance from the pregnant person’s zip-code of residence to the provider’s billing zip-code, measured as centroid to centroid. This study conducted crossworking of zip codes to ZCTAs (Zip Code Tabulation Area). In cases where the zip-codes were the same, the radius of the zip-code area was estimated using the formula area = π r 2 , where the zip-code area was acquired from the 2010 census. A provider with the shortest distance for each patient was identified as the nearest provider. A paired t test was used to compare the travel distances between the two provider types. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) at a significance level of 95%.

Table 1 summarizes the total number of PNC visits for 32,609 pregnancies, and PNC visits at 1,922 providers, resulting a total number of 93,712 pregnancy-provider records. The average total number of PNC visits for all included samples was 7.86. At the pregnancy-provider level, the average number of PNC visits was 2.73. The number of total PNC visits was divided into four categories based on expected PNC frequencies and those with only one PNC visit. Of all pregnancies, 4.62% had more than 14 visits, 40.22% had 9–14 visits, 48.99% had 2–8 visits, and 6.18% had only one visit. At the provider level, however, most providers provided less than 9 times of PNC (8 ≥ PNC: 94.93%).

Table 2 summarizes the number of PNC providers of different definitions at various levels. The average number of providers per person was 2.87, with slightly more than 7% of pregnant individuals experiencing extremely over-dispersed PNC visits (Fig. 1 ). Less than 30% of all pregnant individuals in this sample exclusively visited an Only provider. Another 20% of all pregnant individuals had more than half of their visits with a Majority provider. Additionally, one-third of all pregnant individuals had most of their visits with a Plurality provider. For 7.35% of pregnant individuals, the MultPlur_Initial provided the first PNC visit; for 8.31% of pregnant individuals, the MultPlur_Final provided the last PNC visit; and for 1.43% of pregnant individuals, a single MultPlur_InitialFinal provided both the first and the last PNC visits.

Table 3 presents the percentage of predominant PNC providers, subset by PNC frequency. For all pregnant individuals, the predominant provider was identified mostly as the order of Plurality, Only, Majority, MultPlur_Initial, and MultPlur_Final. Compared with a Majority provider, pregnant individuals who received 2 ~ 8 times PNC were more likely to be identified with a MultPlur_Initial or no identifiable predominant provider (both p < 0.001) and less likely to be with a Only ( p < 0.001) or MultPlur_Final ( p = 0.014). Compared with a Majority provider, pregnant individuals who received 9 ~ 14 times PNC were more likely to be identified with a MultPlur_Final ( p = 0.001) and less likely to be with a Only provider, MultPlur_Initial, or no identifiable predominant provider (all p < 0.001). Compared with a Majority provider, pregnant individuals who received more than 14 times PNC were more likely to be identified with a MultPlur_Initial ( p < 0.001) and less likely to be with a Only provider ( p = 0.004) or no identifiable predominant provider ( p < 0.001). Table 4 summarizes the final percentage of predominant PNC providers in different patterns based on the results from Table 3 . The final percentage ranged between 28.4% and 81.4%, with only frequency information. After integrating sequential information, the percentage ranged between 88.5% and 91.8%.

This algorithm was then applied to measure the travel distance from pregnant individuals to providers using the sixth pattern. The travel distances were compared within the South Carolina boundary, and the sample size was reduced to 29,763 (91.3%). The distance was significantly shorter (19.3 vs. 24.2 miles) for pregnant individuals traveling to the nearest visited PNC provider than to the predominant PNC provider (mean difference:—4.8 miles, 95% Confidence interval:—4.6—-5.1 miles, p < 0.0001).

This study developed a practical algorithm to identify the predominant PNC provider based on guidelines and utilization patterns. The final percentages of identifiable predominant PNC providers were reported based on various patterns. Applying prior algorithms, this study only identified approximately 81% of pregnancies with a predominant provider. After adding sequential information, approximately 92% of pregnancies can now be identified. Except for 7% of over-dispersed cases, only 1% of included pregnancies could not be identified with a predominant provider using this algorithm. Applying this algorithm revealed that pregnant individuals travel a longer distance to their predominant PNC provider than to the nearest visited PNC provider.

The implications for this algorithm are threefold. First, the algorithm integrates visit frequency and sequence information, rather than relying solely on frequency as in previous algorithms [ 8 , 9 ]. A recent study applied three different criteria when both plurality and majority algorithms fail. If two providers were equally eligible to be listed as the predominant provider, the study used sequence (the last visit), expenditure and duration to exclude one of them, resulting in one predominant provider [ 12 ]. In this study, the well-accepted APNCU was utilized [ 16 ] as a justification for including sequence information into the proposed algorithm. Therefore, the percentage of identified predominant providers increased from 81% in the third pattern to 88% in the fifth pattern and to 92% in the sixth pattern.

In addition, this algorithm incorporates dispersion information as a supplement. In this study, those with over-dispersed visits, defined as no identifiable COC provider, were mostly (99.7%) classified as having fewer than 9 times of PNC, with an average and median number of PNC visits of 3. A previous study demonstrated that dispersion increases as the number of chronic conditions increases [ 10 ]. If that is also the case for this study, then these persons represent a high-risk group. However, the proposed algorithm in this study, as well as previous algorithms, failed to identify the predominant provider for them. Future studies may explore alternative rules to identify the predominant provider for this group.

Second, the identified predominant providers can be applied to better understand how patients seek PNC, particularly for pregnancy complications. In this study, pregnant individuals bypassed the nearest provider and traveled on average 5 miles further to their predominant provider. Understanding why patients might choose to receive care that creates a larger travel burden is important, as these burdens negatively impact access [ 22 ]. It is also important to understand why pregnant individuals sought care from such a large variety of providers for their PNC.