We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

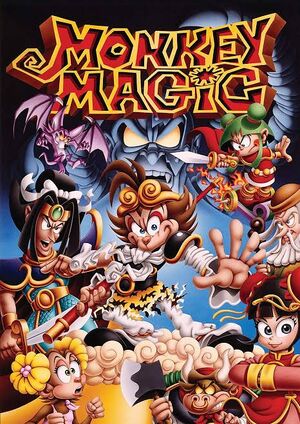

MONKEY MAGIC (1978) EPISODES 1-13

Video item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

43,514 Views

151 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by KiyanShahab on May 2, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Monkey Magic

- View history

Monkey Magi ( モンキーマジック , Monkey Magi ) is a CG-animated television series adaptation of the original Journey to the West novel. It was created by Group TAC which aired on TV Tokyo from December 31, 1999 to March 25, 2000, before its airing in the US on UPN>

Sunsoft produced a PlayStation video game based on the anime.

- 2 Characters

- 3 Episode Guide

- 4 Comparisons from the Original

Long, long ago, in a country far, far away...

From out of the fires of space he was born...Kongo, a monkey made of stone, magically brought to life.

Obsessed with a desire gain knowledge and power, Kongo leaves his family on Flower-Fruit Mountain in search of ancient knowledge and arcane wisdom. Having mastered the magic Jet Cloud as his first trick, he returns to his adopted home just in time to take out the humans laying claim on his territory. Claiming over his first victory, Kongo proclaims himself King of Flower Fruit Mountain.

But it was also a declaration the Gods from above will not accept and launch an attack on Flower Fruit Mountain to teach Kongo a lesson, but unbelievably-it is the gods who learn the lesson- the lesson of defeat!

Seemingly unstoppable, Kongo the Conqueror is invited to the Celestial Heavens where the gods make the mistake of humiliating the monkey and unleashing his full wrath! Before the battle is over, the Celestial Heavens lay in ruin and Kongo has not only gained immortality, but a new, unbeatable weapon as well, stolen from the very heart of the Heavens!

With the Power Rod at his command, can anyone or anything stop Kongo in his quest for universal domination? The universe's only hope lies in The Guardian, the supreme power of the universe, but is it even too late for even it?

Characters [ ]

Episode guide [ ], comparisons from the original [ ].

- The Buddha was named "The Guardian" to avoid religious implications.

- 1 Sun Wukong

- 2 Tang Sanzang

- 3 Ruyi Jingu Bang

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Journey to the West

Sun Wukong the Monkey King, monk Tang Sanzang, humanoid pig Zhu Bajie and river demon Sha Wujing embark on a perilous journey to retrieve holy scriptures from the west, as an act of redempti... Read all Sun Wukong the Monkey King, monk Tang Sanzang, humanoid pig Zhu Bajie and river demon Sha Wujing embark on a perilous journey to retrieve holy scriptures from the west, as an act of redemption for their past sins. On the way, they encounter a host of spirits, monsters and demons ... Read all Sun Wukong the Monkey King, monk Tang Sanzang, humanoid pig Zhu Bajie and river demon Sha Wujing embark on a perilous journey to retrieve holy scriptures from the west, as an act of redemption for their past sins. On the way, they encounter a host of spirits, monsters and demons who threaten their lives and their unity.

- Dicky Cheung

- Yiu-Cheung Lai

- 2 User reviews

Episodes 16

- Monkey King (1996)

- Tang Monk (1996)

- Piggy (1996)

- Sandy (1996)

- Spider Spirit Yan Yan

- Hong Long Meng (1996-1997)

- White Bone Demon (1996)

- Patriarch Subodhi (1996)

- General Tiger

- Centipede Spirit …

- Erlang Shen

- Spider Spirit Mother

- Spider Spirit Si Si

- Weaver Girl

- Jade Emperor

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Connections Remade as The Monkey King (2002)

User reviews 2

- iancestralpubg

- Nov 26, 2021

- How many seasons does Journey to the West have? Powered by Alexa

- November 18, 1996 (Hong Kong)

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

- Runtime 45 minutes

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

‘Journey to the West’: Why the classic Chinese novel’s mischievous monkey – and his very human quest – has inspired centuries of adaptations

Associate Professor of Chinese Studies , College of the Holy Cross

Disclosure statement

Ji Hao does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

College of the Holy Cross provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

One summer afternoon in the late 1980s, my mother and I passed by a tea house on our trip out of town. The crowded building was usually a boisterous place filled with chatter, laughter, and the happy, clacking shuffle of mahjong tiles. At the moment we were passing, however, a great hush came over the teahouse: People were held spellbound by the black-and-white glow of a small TV in a corner, playing an episode of the series “Journey to the West.”

The TV series was adapted from a 16th century Chinese novel with the same title that has undergone numerous adaptations and has captured the imagination of Chinese people to this day. Like many kids in China, I was fascinated by the magic Monkey King, the beloved superhero in the novel, who went through amazing adventures with other pilgrims in their quest for Buddhist scriptures. While I had to quickly walk by the teahouse in order to catch our bus that day, this moment flashed back to me from time to time, making me wonder what made “Journey to the West” so fascinating for people of all ages and backgrounds.

After graduating from college, I embarked on the next chapter of my academic journey in the United States and reconnected with “Journey to the West” from a different perspective. Now, as a scholar with expertise in traditional Chinese literature , I am interested in the development of literary and cultural traditions around the story, including how it has been translated and reimagined by many artists .

While deeply enmeshed in Chinese traditions, the story also resonates with readers from diverse cultures. “Journey to the West” creates shared ground by highlighting the quest for a common humanity, epitomized by its best-loved character, the Monkey King – a symbol of the human mind.

One journey, many stories

Scholars usually trace the beginning of this literary tradition to a Buddhist monk, Xuanzang , who set out on an epic pilgrimage to India in 627 C.E. He was determined to consult and bring back Sanskrit copies of Buddhist scriptures, rather than rely on previous Chinese translations. He did so after nearly 17 years and devoted the rest of his life to translating the scriptures.

The journey has inspired a wide variety of representations in literature, art and religion, making a lasting impact on Chinese culture and society. Legends began to emerge during Xuanzang’s lifetime. Over centuries, they gradually evolved into a distinct tradition of storytelling, often focused on how Xuanzang overcame obstacles with the help of supernatural companions.

This culminated in a 16th century Chinese novel, “Journey to the West.” By this point, the hero of the story had already shifted from Xuanzang to one of his disciples: the Monkey King of Flower-Fruit Mountain, who serves as Xuanzang’s protector. The Monkey King possesses strong magical powers – transforming himself, cloning himself and even performing somersaults that fly him more than 30,000 miles at once.

Despite this novel’s dominance, the broader tradition around “Journey to the West” encompasses a wide variety of stories in diverse forms. The canonic novel itself grew out of this collective effort, and its authorship is still debated – even as it continues to inspire new adaptations.

The deeper journey

Central to all Journey to the West stories is a theme of pilgrimage, which immediately raises a question regarding the nature of the novel: What is the journey really about?

Centuries-long debates about the journey’s deeper message center on the 16th century novel. Traditional commentators in late imperial China adopted a variety of approaches to the novel and underscored its connections with different religious and philosophical doctrines: Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism and syntheses of those teachings.

For example, all these teachings highlight the role of the “xin” – a Chinese word for mind and heart – in self-cultivation. While Confucian readers might see the plot of “Journey to the West” as the quest for a more moral life, Buddhists might decipher it as an inward journey toward enlightenment.

In the early 20th century, Chinese scholar and diplomat Hu Shi criticized traditional allegorical interpretations, which he feared would make the novel seem less approachable for the general public.

His opinion influenced Arthur Waley’s “Monkey ,” an abridged English translation of “Journey to the West” published in 1942, which has contributed to the canonization of the novel abroad . To a considerable extent, “Monkey” turns the pilgrims’ journey into Monkey’s own journey of self-improvement and personal growth.

Recent scholarship has further underlined religious and ritual connotations of the novel from different perspectives, and debates over the issue continue. But few people would deny that one idea plays a crucial role: the Monkey King as a symbol of the mind.

Mind monkey

There has been a long tradition in Chinese culture that associates the image of a simian creature with the human mind. On the one hand, a monkey often symbolizes a restless mind, calling for discipline and cultivation. On the other hand, an active mind also opens up the opportunity to challenge the status quo and even transcend it, progressing to a higher state.

The Monkey King in the novel demonstrates this dual dimension of the mind . He vividly displays adaptability in exploring uncharted territories and adjusting to changing circumstances – and learning to rely on teamwork and self-discipline, not merely his magic powers.

Before being sent on the pilgrimage, the Monkey King’s quest for self-gratification wreaked havoc in heaven and led to his imprisonment by the Buddha. The goddess Guanyin agreed to give him a second chance on the condition that he join the other pilgrims and assist them. His journey is fraught with the tensions between self-discipline and self-reliance, as he learns how to channel his physical and mental powers for good.

The Monkey King’s human qualities, from arrogance to fear, endow him with universal appeal. Readers gradually witness his self-improvement, revealing a common human quest. They may frown upon how the Monkey King is entrapped within his own ego, yet respect his courage in challenging authority and battling adversity. While his mischievous tricks give a good laugh, his loyalty to the monk Xuanzang and his sense of righteousness make a lasting impression.

Reviewing Waley’s “Monkey” in 1943 , Chinese-American writer Helena Kuo commented of the pilgrims: “Humanity would have missed a great deal if they have been exemplary characters.” Indeed, each one depicts humanity’s quest for a better self, particularly the main character. Monkeying around on the path of life, this simian companion captivates readers – and makes them consider their own journey.

- Confucianism

- Chinese culture

- Religion and society

- classic novels

- Ancient texts

- Ancient wisdom

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Biographies

Cast credits, stage team credits.

- Now Playing

- Airing Today

- Popular People

- Discussions

- Leaderboard

- Alternative Titles

- Cast & Crew

- Episode Groups

- Translations

- Backdrops 7

- Login to Add a Video

- Content Issues 1

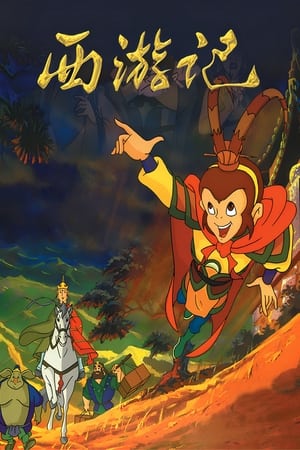

Journey to the West – Legends of the Monkey King (1999)

Login to use TMDB's new rating system.

Welcome to Vibes, TMDB's new rating system! For more information, visit the contribution bible .

Sun Wukong, who was born from a magic stone, has been imprisoned underneath a mountain for five centuries for his mischief in the heavens. One day, the Guanyin told Monkey that the Monk Tang Sanzang will set him free and Monkey will join him on a pilgrimage from China to India. The next day, Tripitaka came and set Monkey free, and the two started their Journey to the West. Along the way, they meet two new friends, Zhu Bajie and the Hermit Sha Wujing, who join them on the journey; together, they face many dangers and evil creatures and sorcerers and learn to get along.

Fang Runnan

Series Cast

Shen Xiaoqian

孙悟空(voice), 孙悟空 (voice)

97 Episodes

52 Episodes

Cheng Yuzhu

猪八戒 (voice)

沙悟净 (voice)

Zhang Hanyu

孙悟空 (voice)

Yan Chongde

太白金星 (voice), 土地 (voice), 金池长老 (voice)

东海龙王 (voice)

Ding Jianhua

观音菩萨 (voice)

Full Cast & Crew

Last Season

1999 • 52 Episodes

Season 1 of Journey to the West – Legends of the Monkey King premiered on July 23, 1999.

View All Seasons

- Discussions 1

Go to Discussions

- Most Popular

Original Name 西游记

Status Ended

Type Scripted

Original Language Chinese

Content Score

Almost there...

Looks like we're missing the following data in en-US or en-US ...

- Created by credit

Top Contributors

35 itianming

21 ronekyng

18 ChboleFO

View Edit History

Popularity Trend

Login to edit

Keyboard Shortcuts

Login to report an issue

You need to be logged in to continue. Click here to login or here to sign up.

Can't find a movie or TV show? Login to create it.

On media pages

On tv season pages, on tv episode pages, on all image pages, on all edit pages, on discussion pages.

Want to rate or add this item to a list?

Not a member?

Sign up and join the community

Letterboxd — Your life in film

Forgotten username or password ?

- Start a new list…

- Add all films to a list…

- Add all films to watchlist

Add to your films…

Press Tab to complete, Enter to create

A moderator has locked this field.

Add to lists

Where to watch

Monkey magic.

2007 ‘西遊記’ Directed by Kensaku Sawada

Journey to the West comes to the big screen like never before in the 2007 film Saiyuuki! Also known as Monkey Magic and Adventures of the Super Monkey, this is the latest in a long line of adaptations of the Wu Cheng'en tome.

Shingo Katori Eri Fukatsu Atsushi Ito Teruyoshi Uchimura Koji Ohkura Asami Mizukawa Takeshi Kaga Goro Kishitani Kumi Koda Tsuyoshi Kusanagi Kiyotaka Nanbara Hiroshi Neko Mikako Tabe

Director Director

Kensaku Sawada

Producer Producer

Juichi Uehara

Writer Writer

Yuji Sakamoto

Cinematography Cinematography

Kosuke Matsushima

Executive Producers Exec. Producers

Chihiro Kameyama Yoshishige Shimatani

Art Direction Art Direction

Takeshi Shimizu

Visual Effects Visual Effects

Atsuki Sato

Composer Composer

Satoshi Takebe

Sound Sound

Osamu Takizawa

Fuji Television Network TOHO J-dream Cine Bazar

Alternative Titles

The Adventures of Super Monkey, Saiyûki, Monkey Magic: The Movie, Saiyuuki the Movie, Journey to the West

Action Fantasy Comedy Adventure

Releases by Date

14 jul 2007, 11 may 2008, releases by country.

- Physical M Released on DVD under the title "Monkey Magic"

116 mins More at IMDb TMDb Report this page

Popular reviews

Review by Maxton Huff ★★★

Best Puddies!

Monkey Magic, also known as the Adventures of Super Monkey, also known as Journey to the West, also known as Saiyûki , is a little-known epic following the adventures of a revolving cast of borderline irrelevant side characters who team up with the Monkey King to take down the Silver King and his less talkative Golden King brother for the sake of some random village he and his crew find on a journey to India. The first half is pretty rough since it equally focuses on each of the side characters while focusing on Goku the Monkey King as a side character. None of the superhuman abilities of any of the characters are shown up until it goes all-in and…

Review by Gavin Zahn ★★★½

This movie really won me over when it started a Mario Kart-esque chase sequence high in the sky on magical, flying cloud scooters.

Review by intruder2k ★½

Another Japanese version of the story, but not a patch on the classic 1970s show.

Review by Hunter Cooke ★★★★

It has been such a long time since I’ve watched this film. Used to watch it all the time.

I will admit nostalgia is the reason I’ve given it a high score.

Review by Mark Boszko ★★★★

I have a real soft spot for legends like these — and a Japanese retelling of a Chinese legend? Sign me up. it's ridiculous and the Monkey King is bombastic and annoying — as he should be. A fun version of the oft-told story.

Review by reton ½ 1

I do not like Japanese movies. Too much anime in their life action movies.

Select your preferred poster

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 November 2023

Reframing the narrative of magic wind in Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West : another look at the abridged translation

- Feng (Robin) Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4825-1151 1 ,

- Keqiang Liu 2 &

- Philippe Humblé 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 876 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1182 Accesses

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

This article examines Arthur Waley’s abridged translation of “Journey to the West”, titled “Monkey”, and its influence on magic wind narrativity using narrative theory and (re)framing concepts. The research categorises the narrative significance of the magical wind in the source text and highlights its powers as destruction, transport and transformation. In contrast, these elements seem subdued in “Monkey”. Waley’s reframing employs strategies, such as (I) temporal and spatial reframing; (II) selective appropriation, emphasising stories of pilgrims saving their lands, while overshadowing important cultural and religious aspects of the original; and (III) modifying specific labelling techniques that include references to the magical wind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reconfiguring a Chinese superhero through the dubbed versions of Monkey King: Hero is Back (2015)

Joseph Campbell’s Oriental mythology in Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Occidental mythology in Ghost in the Shell (2017)

Novels of Vaddey Ratner and Viet Thanh Nguyen—unpacking trauma language, facing ghosts, and killing shadows

Journey to the west and waley’s abridged translation.

The Chinese epic Journey to the West (pinyin: Xi You Ji, hereafter Journey ) is based on a Buddhist pilgrimage undertaken in the seventh century by Monk Tripitaka, who traveled to India for seventeen years in search of Buddhist scriptures. The storyline is a syncretic mix of Chinese mythology, narrative poetry, political satire, allusions to Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, and humorous stories drawn mainly from Tripitaka’s autobiographical notes, Eminent Tang Monk Xuanzang’s Record of Western Territories (pinyin: Da Tang Gao Seng Xi Yu Ji), besides folklore, and vernacular dramas. Monk Tripitaka, accompanied by his three supernatural disciples, Sun Wukong (the Monkey King), Zhu Bajie (Pigsy), and Sha Wujing (Sandy), traverses a magic and mystical land filled with monsters, demons, and cannibals, ultimately bringing Mahayana Buddhist sūtras to Tang China.

According to Yang ( 2012 , p. 151), “No great novel in Chinese literature has beguiled many critics for so long a time like Journey ”. The book’s literary interpretation has long been the subject of debate. Commenting on the narrative density of Journey , Bantly ( 1989 , p. 512) argues: “The narrative richness of the Chinese Ming (1368–1644) novel known as the Hsi-yu chi, or Journey to the West , presents a daunting challenge to the interpreter. The bewildering array of cultural lore—especially from the three major religious traditions of China (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism)—is so diverse and boldly interwoven that it almost appears as “simply furniture thrown in to impress, or mock, the reader” (Plaks, 1977 , p. 181). Thus, any interpretation faces the danger of exaggerating the importance of these cultural and religious elements, only to discover that the author offered them in jest” (Bantly, 1989 , p. 512).

For Western readers, this Chinese classic’s English translation and dissemination have been “an arduous journey”(Škultéty, 2009 , p. 116). Wang et al. ( 2020 ) periodize the retranslation of the Journey into four relatively independent but closely linked phases: fragmentation (1895–1931), distortion (1932–1977), restoration (1978–1986), and new refraction (1987 onwards) characterised by diverse media interpretations, such as anime, film, television and children’s literature.

Whereas Waley’s abridged translation Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China (first published by George Allen and Unwin in 1942, hereafter “ Monkey ”) is labeled as “distortion” (Wang et al. 2020 ) or “adopting a secularized approach” (Wang and Humblé, 2018 , p. 508), this version, among all English renditions, had a profound influence on both popular and academic audiences, becoming a household name in the western world. In their prefaces, Jenner’s (four-volume first edition published between 1982 and 1986 by the Foreign Languages Press) and Yu’s (four-volume first edition published between 1977 and 1983 by the Chicago University Press) complete translations refer to Waley’s version as the impetus for their interest in completing and even correcting their predecessor. In this study, Waley’s Monkey is the research object, and the characteristics of Waley’s translation will be extracted by occasionally comparing it to Jenner’s and Yu’s.

Previous studies have already considered textual and socio-cultural aspects of Waley’s Monkey .A plethora of works has assessed his translation strategies in terms of domestication versus foreignization (Wong, 2013 ), regarding the colloquial style of the prose dialogues (Škultéty, 2009 ), readability (Ji, 2016 ), etc. These textual studies reached the consensus that Waley’s abridgment successfully brought the antique style of a 16th-century Chinese chaptered novel closer to contemporary readers with a high level of readability.Aligning the target text with the source text, recent research has focused on the sociological factors involved in the translation process. Using the actor-network theory, Luo and Zheng ( 2017 ) scrutinize the non-human agents that participated in and influenced the translation and publication of Monkey . This research contributed to the current textual and contextual scholarship on Monkey . While the ways in which Waley’s abridgment alters the narrative richness of the text remains a relatively unexplored topic, an even smaller number of scholars have delved into the cultural mediation and conflict stemming from Waley’s condensation. The narrative inquiry about translated literature is situated at “a meso level of translation studies” with the objective of “bridging translation strategy research with literary study” (Wang et al. 2019 , p. 10).

A narrative account of the Journey and its translation

Narratology is frequently associated with the emergence of structuralism in the 1960s. It encompasses both classical (the structural paradigm regarding what and how a story is told) and postclassical (the social paradigm with a greater emphasis on the hidden ideological concerns in the story) approaches (Puckett, 2016 , p. 2). In other words, a narrative inquiry into an abridged translation goes beyond mapping the different translation methods and strategies employed by the translator and adds to the missing account of how a different story is generated in the target context. It also investigates what intercultural and ideological conflicts exist in the abridgment. Following is an attempt to sketch the current applications of narrative theory to Journey and its translation.

A structuralist narrative paradigm

The primary objective of a structuralist narrative study (narratology) is to define the formal features of literary texts in terms of story and narrative discourse . ‘Story’ refers to “the events, the actions, the agents, and the objects that make up the stuff of a given narrative” (Puckett, 2016 , p.2). Discourse refers to “the shape that those events, actions, agents, and objects take when they are selected, arranged, and represented in one or another medium” (Ibid). These two strands, which represent the content and the structure of a narrative, being complementary, are analyzed in tandem to determine the literary meaning of a story.

Narrative studies of Journey have been closely anchored in the generic features, i.e., the traditional Chinese God and Evil Spirit Novel (神魔小说), in which creative imagination wields immense power “to produce something that has never existed before, a hitherto unperceived version of reality”(Wong, 1996 , p. 39). When the supernatural narrative establishes itself as a genre, it is able to “channel the reader’s inferences, help create intelligibility and coherence, and delimit the scope of interpretation”(Toolan, 2009 , p. 5). For example, the fantastic dens, mountains, and rivers in Journey exude an aura of personalized characteristics: they become perilous and noxious, in tune with the resident demons, and occasionally benevolent as the abode of the immortals. In the narrative, spatial elements serve as flashforwards, foreshadowing events, or acting as prophecies. These elements hint at the identity of forthcoming characters, heightening the reader’s pleasure in unraveling the story (Li, 2017 ; Jia, 2012 ; Lian, 2010 ).

In addition, the protagonist’s story, specifically Monkey’s, is interpreted as a personal development or evolution in response to his Buddhist conversion (Lai, 1994 ; Wang and Humblé, 2018 ). The foes of the pilgrims, particularly the various female demons with a carnal desire for Monk Tripitaka, have attracted narratologists to interpret their metonyms, metaphors, and allusions in light of Taoism’s Five Elements and Yin-Yang doctrines(Bantly, 1989 ; Yuan, 2020 ), feminism(Feng, 2010 ; Zhang, 2004 ; Wang, 2014 ; Zang, 2010 ). Other marginal characters, on the other hand, are not so narratively capricious, but they are named artfully based on their dispositions. For example, “急如火” (literally: Quick Fire) and “快如风” (literally: Fast Wind), are two lesser demons with an impulsive personality who messed up the task their demon king had assigned them. Therefore, on the level of discourse, the first appearance of their names foreshadows what will happen (Li, 2016 ; Wang, 2008 ). These narrative characteristics require the translation to maintain a “literal-and-narrative” faithfulness, equivalent to the figure’s name in the source text without diminishing its narrative significance (Wang et al. 2023 ).

According to our findings, most existing research focuses on the manipulated image of female demons, such as in the Spanish translation of Journey (Mi, 2022 ), or the translation of euphemisms in erotic narratives (Rong, 2017 ). Many other important topics within the scope of structuralist narratology have escaped the scholars’ attention, as in most post-structuralist developments. Except for Feng ( 2014 ), narratologists have not paid much attention to supernatural elements like the wind . We will review their findings in the section “Research design: An eclectic narrative model for translation studies”.

A social narrative paradigm

Unlike the structuralist paradigm, which prioritizes“accuracy of translation in relation to the source text”(Baker, 2010 , p. 347), the social narrative paradigm challenges the goal of “maintaining semantic resemblance to the source text” (ibid, p.347). Following the social narrative paradigm (Somers, 1992 , 1994 ), Baker ( 2019 , p.105) defines the translatorial act of “renegotiating the narrativity of the source text to produce a politically charged narrative” as (re)framing. This paradigm prompts socio-cultural reflections on the neglected subject of “accurate translations, but suspicious frames” (Baker, 2010 ). Due to its capacity to extend beyond individual will to a broader scope of social cognition, the term “frame” is particularly pertinent. The translation is a frame unto itself, providing a set of beliefs and ideologies that enable readers to make sense of the messages and attribute meaning to the world.

The social paradigm has been broadly applied to political conflict situations, including narratives of terrorism (Baker, 2010 ; Boukhaffa, 2018 ; Harding, 2012 ), activism (Baker, 2013 ), WWIIvictims(Kim, 2017 ), among others. In contrast to most social narrative research, which sometimes ignores literary works, examples of ideological conflict and recasting are abundant in literary translation. For example, Liu’s ( 2017 ) analysis of A Mission to Heaven , Timothy Richard’s 1913 Christianization rewrite of Journey to the West , gives an eloquent example of this fact. Liu aligns the narrative elements of A Mission to Heaven with the Baptist missionary translator’s religious identity. She analyzed Timothy’s three key reframing strategies: temporal and spatial (replacing the East’s temporal and spatial terms with Christian ones), selective appropriation (abridgment of the source text), and framing by labeling (westernizing the Chinese couplet chapter titles). The open-ended list of reframing strategies sheds light on the textual and ideological reorganization in Waley’s Monkey , even though Waley abandoned the Christianization replacement for the Buddhist narrative. Using Liu’s ( 2017 ) methodology as a starting point, we can investigate which narrative stories have likely been reframed by Waley. In other words, the question of what information is highlighted or minimized in Monkey is central. This can be addressed using ontological, public, conceptual, and metanarratives (Table 1 ).

Research design: an eclectic narrative model for translation studies

The interface between narrative and translation studies has been fruitfully discussed before (Baker, 2019 ; Brownlie, 2006 ; Van Doorslaer, 2012 ). The structuralist and social camps have reached a broad consensus that translation is a type of narrative derived from the source text. Even if a completely equivalent translation is possible, translators—particularly when influenced by differing social contexts—“resort to various strategies to accentuate, undermine, or modify aspects of the narrative(s) encoded in the source text.” (Baker, 2019 , p. 106). When considering the collaboration with publishers, editors, and other agents, this may also become even more complicated and reveal ideological differences.

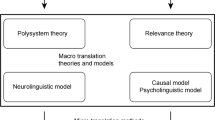

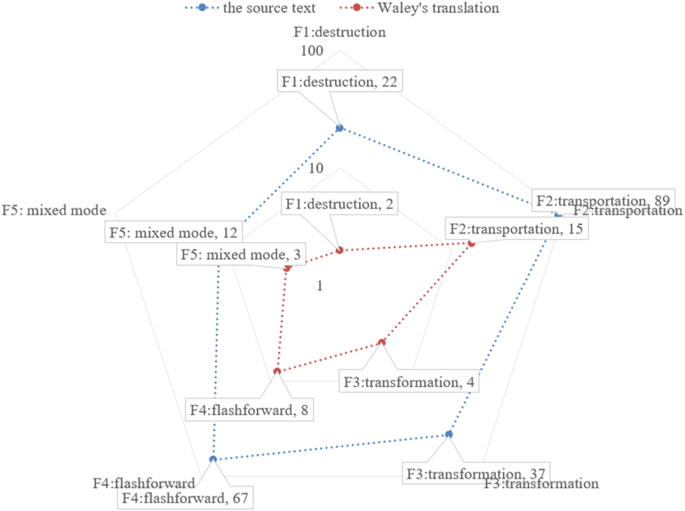

Although some researchers have criticized the structuralist influence in translation studies (Kruger, 2009 , p. 15), this classical paradigm, which emphasizes narrative content and verbal arts, is by no means obsolete. This is precisely what the social paradigm lacks when the object of study is a literary work. On the other hand, the social narrative paradigm excels at revealing reframing strategies and effects, but it “only dwells on the story strand of the narrative”(Baker, 2019 , p. 19) without consideration of the verbal arts, such as flashback, flashforward, and narrator tones. We tend to view these two paradigms as complementary rather than antagonistic, and we therefore propose an eclectic model (Fig. 1 ).

An eclectic model of the narrativity translation.

As Baker ( 2019 , p. 3) emphasizes in her narrative approach originating from social communication theory (Somers, 1992 ) rather than structuralist narratology or linguistics, there is no lack of affinity between these two schools in terms of analyzing causal relationships between events, temporal and spatial position, participants, and others. Due to Journey’s 100-chapter length, it actually encapsulates a rich array of the ontological, public, conceptual, and meta-narratives, which eventually might render our analysis arbitrary. According to Pym ( 2016 ), the neglect of discursive linearity and the absence of valuable narratology-based theoretical concepts directly undermine the testability of Baker’s theory. As a beneficial theoretical amendment, Harding’s revised model of the social narrative paradigm introduced a dual typology of personal and shared or collective narratives. This model was developed through sustained textual analysis to highlight the distinction between personal and other types of narratives, emphasizing the collaborative, consensus-building, and coercive processes involved in constructing collective narratives (Harding, 2009 , 2012 ). Due to the presence of (in)compatible multisource narratives from eyewitnesses, authorities, news agencies, and other sources, this model applies to news translation. Understanding the dynamics of collaboration and coercion involved in the collective construction of these narratives is helpful. However, it is essential to note that this model may not be suitable for analyzing Chinese God and Evil Spirit novels. These frequently explore themes extending beyond personal or collective narratives and beyond ‘daily narration’. They use specific narrative techniques, sarcasm, flashforwards, and flashbacks. Consequently, Harding’s model is too general and inapplicable in this context. To understand the narrative structure and meaning of Chinese God and Evil Spirit Novels, it is necessary to consider the novels’ numerous themes and discourse techniques (Fig. 1 ).

To begin our analysis, we will outline the narrative structure of magic wind in the source text. We aim to investigate reframed narratives and the corresponding reframing strategies while maintaining a manageable focus on discursive linearity. Our analytic model combines structuralist and social paradigms (represented by the red and blue boxes). Our model’s central analytic unit is narrativity, and the primary focus is on examining reframing strategies and their effects (as indicated by the green dotted line). As shown in Fig. 1 , we begin by analyzing the narrativity of the source text (as illustrated by the narrativity of wind in the section “The wind narrativity in the source text”). The second research question concerns Waley’s primary reframing strategies concerning the social narrative paradigm (see section “Reframing the Narrativity of Magic Wind in Monkey ”). The fifth section “Reframing the Narrativity of Magic Wind in Monkey ” also investigates the third research question: how the abridged version produces a distinct narrative style. A structuralist approach (visualization of the results in a radar graph) and a social approach (the changes of ontological, public, conceptual, and meta-narratives) will be used to answer this last question.

The wind narrativity in the source text

At this point, suffice it to say that novelists are adept at using fiction-specific terms or making a particular use of common language terms (Siepmann, 2015 , p. 370).In the case of Journey , a bizarre assortment of demons, monsters, immortals, and celestial beings appear in a fantastic world where even the mundane can be infused with a touch of myth. As mentioned in Section “A narrative account of the Journey and its translation”, Journey’s character and space narratives have aroused growing attention. The supernatural elements contributing to the God and Demon Novel, such as the magic wind in Journey , have not garnered attention.

Why does the narrative of magic wind matter?

The story space of Journey consists primarily of three worlds: (1) the Celestial World, which includes the Thunder Monastery at the Saha Vulture Peak, ruled by the Tathagata Buddha, and Heaven, ruled by the Jade Emperor, the supreme leader of the Taoist pantheon; (2) the Terrestrial World, where immortals, evil spirits, and demons coexist with the majority of mortals; and (3) the Underworld, which holds the souls of the deceased.

Throughout Tripitaka’s pilgrimage, the ostensibly parallel three worlds are frequently interconnected and interwoven. Space prohibits a detailed description of all these magical phenomena. As a recurrent lexical item in Journey , 风 (wind) demonstrates a multidimensional sense of entity due to its directionality (e.g., 东南风 southeast wind), odor (e.g., 香风 a fragrant wind), dermal sensation (e.g., 冷风icy wind), visibility (e.g., 黑风a black wind), audibility (e.g., 风响声a roaring wind). Due to its spatiality and mobility, both wind and wind harnessers are freely permeable across the triple world, which is conducive to the novel’s mythological genre. In this sense, the magic wind narrative in Journey “designates the quality of being narrative, making the narratives more prototypically-narrative like, more immediately identified, processed and interpreted as narratives”(Prince, 2005 ). A simple linguistic alignment with the source text is insufficient for understanding Monkey better if it does not explain how the narrative is altered due to being abbreviated.

Feng’s ( 2014 ) threefold narrativity of the magic wind

Feng ( 2014 ) provided a summary of the magic wind’s threefold narrative role in the source text.

A portent of an impending fantastic event

Example 1: 才然合眼, 见一阵狂风过处, 禅房门外有一朝皇帝, 自言是乌鸡国王No “sooner had I closed my eyes than there cam e a wild gust of wind , and there at the door stood an Emperor, who said he was the King of Crow-Cock” (Waley’s translation, Chapter 37).In this excerpt, the appearance of the Kingis heralded by a furious gust of wind awakening Tripitaka from his doze.

A combination of strength and speed granting supernatural ability

Example 2: 即点本部神兵, 驾鹰牵犬, 搭弩张弓, 纵狂风, 霎时过了东洋大海, 径至花果山 “The brothers were delighted, and they at once marshalled the divinities in their charge.The whole temple set out, falcon on wrist, or leading their dogs, bow in hand, carried by a wild magic wind . In a trice they had crossed the Eastern Ocean and reached the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit” (Waley’s translation, Chapter 6).The magic power of the brothers is demonstrated by the ease with which they can stride across the ocean on a wild magic wind.

A tangible entity accompanied by physical transformation

Example 3: 却将马拴在道旁草头上, 转身拜谢那公公, 那公公遂化作一阵清风, 跨一只朱顶白鹤, 腾空而去“Tripitaka tied up the horse at the path-side and turned to thank the old man, only to discover that he was already rapidly disappearing into the sky , on the back of a white crane” (Waley’s translation, Chapter 13).

Therein resides a cultural script that, due to its invisibility and intangibility, could be the easiest to transform. Wind in Journey typically accompanies supernatural beings during their physical transformation. Additionally, the wind may subtly hint at the rider’s identity. In Example 3, 清风 (literally: pure breeze, which Waley omits in his translation) is driven by a god, whereas the winds driven by spirits, demons, and monsters are typically 狂风 (see Example 1), 黑风 (black wind), and even腥风(stinky wind). As a result, we provide an additional function, namely that the property of magic wind may serve as a flashforward revealing the identity of the wind rider. As shown in Example 1, the self-proclaimed emperor is actually the spirit of the drowned King. The gust of wild wind heralds the arrival of an anomaly. This is extremely important for a narrative-based study on Waley’s abridged translation. After determining the variety and scope of the narrativity of magic wind based on a corpus-based close reading of the source text, we will address this further.

A close reading of the narrativity of magic wind

Feng’s ( 2014 ) typology provides a useful starting point, which, along with other persistent and generically relevant elements, is placed under the umbrella of “functional narrative” by Yang ( 2018 ) to highlight the generic characteristics inherent in the 16th-century novel. Methodologically, these studies rely essentially on selective argumentation without thorough textual scrutiny. To remedy this shortfall, we propose an exhaustive study of the narrativity of magic wind.

First, we identify a total of 996 occurrences of 风 (wind) to 228 occurrences, excluding the narrative of “mortal wind” (Example 4) and idiomatic and metaphorical expressions (Example 5).

Example 4: 刮风有处躲, 下雨好存身“We can hide there from the wind , And shelter from the rain.”(Jenner’s translation, Chapter 1. This sentence is omitted in Waley’s version).

Example 5: 不知马行的快, 行者如风; 马行的迟, 行者慢走 (第37章) “When the horse galloped fast, Monkey ran like the wind ; when it slowed down, Monkey slowed down.” (Chapter 37, Waley’s translation).

This distinction entails a contextual interpretation: narrative discourse contributes to the formation of the story, and the story elucidates the meaning of the narrative discourse, which is especially malleable, as it can alter the chronological order of events. One can vary the presentation of the narrative discourse while essentially telling the same story.

Table 2 summarizes the narrativity of the magic wind in the original story. In the context of narrative discourse, either foreshadowing the arrival of a fantastic event (Example 1) or alluding to the identity of the wind rider (Example 3) constitutes a “flashforward,” which is “an introduction to the narrative material that comes later in the story”(Abbott, 2002 , p. 195). On the story level, our revised model continues to specify how magic wind, as a combination of speed and power, spells supernatural results in terms of destruction (Function 1), transportation (Function 2), and transformation (see Table 2 ).

Given the story-discourse duality of the narrative, there are numerous mixed mode instances of magic wind displaying simultaneously its magical power and the manipulated temporal order.This blending is easily overlooked by readers who are captivated by the plot (at the story level) and fail to notice the flashforward function. As demonstrated by the mixed mode example in Table 1 , 清风 (literally: a puff of pure wind) is inconsistent with the ogre’s identity, as it is typically reserved for the immortal god. At the conclusion of Chapter 17, the ogre’s origin is revealed as the Heavenly River’s former Marshal. To atone for his transgressions, he converts to Buddhism and becomes a disciple of Tripitaka. The initially discordant match between the wind and the rider is essentially a flashforward, similar to Example 1. Waley’s English translation does not adequately convey this peculiarity. The following sections will examine how the magic wind narrative is reframed.

Reframing the Narrativity of Magic Wind in Monkey

Temporal and spatial framing.

Temporal and spatial framing involves deliberately selecting a text from a peculiar temporal and spatial context to invoke an ideological concordance in the recipient context. “This type of embedding requires no further textual intervention, although it does not necessarily rule out such intervention” (Baker, 2019 , p. 112). Waley was evidently aware of his intended temporal and spatial location’s interpretation mechanism. His typescript was not completed until 1941 when London was under Nazi attack. As his wife Alison Waley recalled, Waley’s job, as a government employee during World War II, was to decode East Asian intelligence. However, he would continue his translation whenever the air-raid siren ceased to sound (Wang, 2019 ). The fifth reprint in 1945 and the copyright export to the United States in 1943 indicate that the War and several adversary factors, such as epidemic in 1943 and the lack of printing paper, did not impede the market demand, as evidenced by the fifth reprint in 1945 and the copyright export to America in 1943 (Luo and Zheng, 2017 ; Wang et al. 2020 ). In contrast, the narrative of Monkey’s heroism and optimism in the face of adversity embedded in Waley’s translation met the need of the time and somehow soothed the worries of the UK reader. In order to illustrate this point, we must consider Waley’s selective appropriation of textual material.

Selective appropriation of textual material

Readability and selective appropriation.

Baker ( 2019 , p.115) defines selective appropriation as a deliberate selection and omission within a text, frequently to avoid censorship. This was not the case for Waley, who, in his preface, expressly stated that the balance between readability and accuracy of his translation was his primary concern.

The original book is indeed of immense length and is usually read in abridged forms.The method adopted in these abridgments is to leave the original number of separate episodes, but drastically reduce them in length, mainly by cutting out dialogue.I have, for the most part, adopted the opposite principle, omitting many episodes, but translating those that are retained almost in full, leaving out, however, most of the incidental passages in verse, which go very badly into English (Waley, 1942 ).

Indeed, Waley’s 30-chapter abridgment is consistent with the source text’s narrative structure, preserving the skeleton of the original story: (I) the story of Monkey (Chapters 1-7), (II) the story of Tripitaka and the origin of the pilgrimage (Chapters 8-12), and (IV) the arrival at the Thunder Monastery, taking the Buddhist sūtras to Tang China (Chapters 98-100).Regarding the mainstay (III) of the pilgrimage, Chapters 13-97, he retained the story of the Buddhist conversion of Tripitaka’s followers (The Taming of the Monkey: Chapters 13-14, The Dragon Horse: Chapter 15, Pigsy: Chapters 18-19, Sandy: Chapter 22) and three adventurous episodes (The Lion Demon in the Kingdom of Crow-Cock: Chapters 37-39, The Cart-Slow Kingdom: Chapters 44-46, The River that Leads to Heaven and the Great King of Miracles: Chapters 47-49). Waley’s selective appropriation endows his abridgement work with a remarkable global perspective that resonates with the mythical reality of Western and Indian literature.

For instance, the tale of the Crow-Cock Kingdom contains elements reminiscent of Hamlet: a king ruthlessly slain, a shrewd confidant who seizes both his throne and marital bed, and a displaced prince charged with delivering retribution. In the tale of the Cart-Slow Kingdom, the Buddhist inhabitants endure the same fate as the Israelites during their Egyptian captivity, and Monkey and Pigsy defeat the King’s three Taoist counselors in the same magical manner as Moses and Aaron did with thePharaoh’s priests. As for the monster that rules over the River that Leads to Heaven, his yearly demand for the sacrifice of living children ties him to the Minotaur and Ho-po (河伯) from Western and Chinese mythology, respectively (Hsia, 2016 ). Monkey’s character consistently displays courage and intelligence, overcoming obstacles on the pilgrimage and saving mortals from demon persecution.

Cultural specificity and religious fusion lost in the selective appropriation

As mentioned before, selective appropriation is framed in accordance with its temporal and spatial location. As for the narrative quality of magic wind, the abridged version is by no means a miniature of the source text. Apart from the strategy of “secularization” (Wang et al. 2020 ), the inherent narrative quality of the source text is sacrificed for readability and globality in Waley’s abridgment. Figure 2 compares the distribution of subtypes of magic wind in the source text to that in Waley’s abridged version.

Narrativity of the magic wind in the source text compared to Waley’s translation.

As the radar graph indicates, in Waley’s abridged version, the narratives of magic wind with the power of destruction and transformation appear to be diminished. In Chapters 20 and 21, where pilgrims are hindered by the Yellow Wind Demon (黄风怪) who can blow the Divine Sāmadhi Wind (三昧神风) close enough to Monkey’s eyes to blind him, the destruction of magic wind occupies a prominent position.

Example 6. 那怪害怕, 也使一般本事: 急回头, 望着巽地上把口张了三张, 嘑的一口气, 吹将出去, 忽然间, 一阵黄风, 从空刮起Somewhat alarmed, the monster also resorted to his special talent. He turned to face the ground to the southwest and opened his mouth three times to blow out some air. Suddenly a mighty yellow wind arose in the sky. (Yu’s translation).

Unlike Waley’s selective adaptation, Yu comprehensively addresses potential cultural gaps for English-speaking readers in his 100-chapter translation. Samādhi (三昧) first appears in Chapter 1, as well as in the endnote list.

The Buddhist doctrine of the three Samādhis refers to meditation on three subjects: (1) kong , or emptiness, which purges the mind of all ideas and illusions; (2) wuxiang , or no appearance, which purges the mind of all phenomena and external forms; and (3) wuyuan , or no desire, which purges the mind of all desires (Yu, 2012 , p.507).

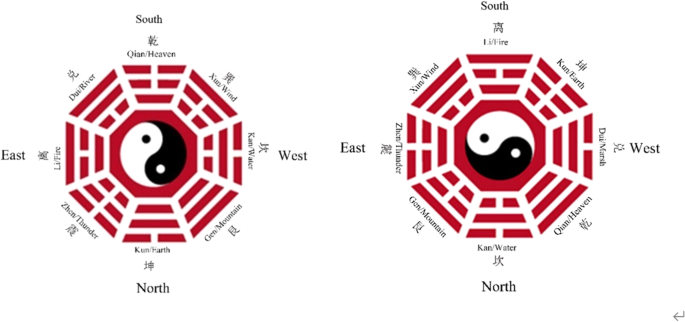

The religious connection of Samādhis functions in part as a flashforward announcing Yellow Wind Demon’s Buddhist origin. At the conclusion of Chapter 21, the voice of Tathāgata reveals the solution to this riddle: “Originally, he was a rodent at the foot of the Spirit Mountain who had acquired the Way. Because he stole some pure oil in the crystal chalice, he fled, fearing that the vajra attendants would seize him”. Another cultural specificity in Example 6 is 巽 (xun), which originates from the Eight Trigrams (八卦) and signifies wind as natural energy as well as the southeast direction (Fig. 3 ). In Taoist cosmology, the Eight Trigrams are frequently employed to obscure the fundamental principles of reality. In accordance with the Early Heaven Eight Trigrams (Fig. 3 ), each pair of opposing trigrams is arranged in opposition due to Yin-Yang’s (阴阳) emphasis on opposing but complementary dynamics.

The Early Heaven Eight Trigrams (left) and the Later Heaven Eight Trigrams (right).

On the other hand, the Eight Trigrams of Later Heaven depict the locational, directional, and cyclical Qi (气) flow of the Five Elements (五行). It depicts the natural cycle of birth, growth, decline, and death.The blending narratives of Samādhi and the Eight Trigrams, found in many other chapters of Journey , point to the meta-narrative, i.e., the convergence of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, their mutual assimilation and prosperity. Along with the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义), the Dream of the Red Mansions (红楼梦), and Outlaws of the Marsh (水浒传), this is one of the reasons why Journey to the West is considered one of the Four Greatest Classical Novels of Chinese literature.

To counteract the destructive force of magic wind, the Wind-Fixing Pellet (定风丹) and Flying Dragon Crutch (飞龙杖) are conceived in the story as a manifestation of the underlying philosophy of “mutual production and conquest” (相生相克). The antagonistic relationship between the pilgrims and the demons is also consistent with the traditional Chinese “Yin-Yang” philosophy, which suggests a combative and dependent circular arrangement (Campany, 1985 , p. 111). In a nutshell, a plethora of traditional Chinese culturally specific elements, such as Yin-Yang, mutual production, conquest, the Eight Trigrams, etc., are encapsulated in the conceptual narrative of the destructive magic wind. The loss of the aforementioned conceptual narratives due to Waley’s selective appropriation is regrettable.

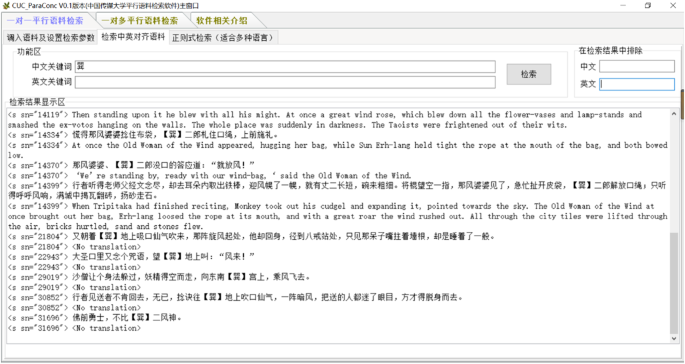

To determine whether Waley’s deculturalization is the rule, we searched all his translations of “巽” in Chinese and Waley’s English translation using CUC ParaConc, a Chinese-English parallel corpus tool developed by the Communication University of China (Fig. 4 ). There are nineteen instances of “巽” in the source text, with nine instances of <No translation> due to selective appropriation, two instances of transliteration without further explanation (Wade-Giles romanization: Sun ), and eight instances of omission (Example 7).

Screenshot of 巽 and Waley’s translations as a parallel corpus.

Example 7. 他就捻起诀来, 念动咒语, 向巽地上吸一口气, 呼的吹将去, 便是一阵风, 飞沙走石He made a magic pass, recited a spell and drew a magic diagram on the ground .He then stood in the middle of it, drew a long breath and expelled it with such force that sand and stones hurtled through the air (Waley’s translation, Chapter 3).

He, therefore, made the magic sign and recited a spell. Facing the ground on the southwest , he took a deep breath and then blew it out. At once, it became a mighty wind, hurtling pebbles and rocks through the air (Yu’s translation, Chapter 3).

He made a magic with his fist and said the words of the spell, sucked in some air from the Southeast , and blew it hard out again. It turned into a terrifying gale carrying sand and stones with it (Jenner’s translation, Chapter 3).

Waley’s omission in Example 7 effectively avoids the conundrum of cultural specificity, while both Yu and Jenner explain the allusion to the wind direction. Yu adheres to the Early Heaven Eight Trigrams, whereas Jenner adheres to the Later Heaven Eight Trigrams (cf. Figure 3 ). We generally agree with Jenner’s decision for two reasons: On the one hand, the Later Heaven Eight Trigrams is widely used for navigation, calculation, etc. On the other hand, Chapter 7 depicts Lao Tzu’s furnace of Eight Trigrams according to the sequence of the Later Heaven Trigrams (see Fig. 3 ): 原来那炉是乾、坎、艮、震、巽、离、坤、兑八卦. Lao Tzu’s furnace consists of the Eight Trigrams: Qian, Kan, Gen, Zhen, Sun, Li, Kun, and Dui (Jenner’s translation, Chapter 7). In view of the above evidence, we can confirm that Waley’s deculturalization-oriented appropriation is a rule and deliberate.

Only four of the magic wind’s 37 occurrences were retained, which is another narrativity flaw (see Fig. 2 ). The four accounts of survival are as follows: A stone egg fertilized by the wind grew into a stone monkey (Chapter 1); Monkey struck the wind into which Pigsy morphed into a flee (Chapter 18); The Dragon King, in the form of a magical whirlwind, rushed to the cauldron to capture the icy dragon (Chapter 46); The Goldfish Monster transformed into a gust of wind and vanished from the river (Chapter 48). Monkey’s participation in the transformation narrativity is less prominent than in the source text. The narrative of loss focuses primarily on the battles, pursuits, and escapes between pilgrims and demons. We find that Waley’s selective appropriation has led to the overshadowing of Monkey’s ontological narrative, particularly his relentless subjugation of demons. In the source text, the transformation of Monkey’s weapon, The Compliant Golden-Hooped Rod (如意金箍棒), occurs up to eleven times, becoming formulaic language. With one exception (Example 8), Waley, in contrast, eliminated all of these narrative elements. The cudgel retains its transformation, but there is no trace of wind.

Example 8. 行者伸手去耳朵里拔出一根绣花针儿, 迎风一幌, 却是一条铁棒, 足有碗来粗细, 拿在手中道: “不要走! 也让老孙打一棍儿试试手! ”

Monkey took his needle from behind his ear, recited a spell that changed it into a huge cudgel, and cried, ‘Hold your ground and let old Monkey try his hand upon you! (Waley’s translation, Chapter 14).

Pilgrim reached into his ear and took out a tiny embroidery needle; one wave of it in the wind and it became an iron rod with the thickness of a rice bowl. He held it in his hands, saying, “Don’t run!Let old Monkey try his hand on you with this rod!” (Yu’s translation, Chapter 14).

Taking the embroidery needle from his ear, Brother Monkey shook it in the wind , at which it became an iron cudgel as thick as a rice bowl. With this in his hand he said, “Stick around while I try my cudgel out.” (Jenner’s translation, Chapter 14).

In contrast to Jenner’s and Yu’s translations, Waley eliminated the wind’s causal emplotment and the rod’s transmutation. Waley’s simplified translation mutilated the narrativity of wind.

Baker ( 2019 , p.122) defines labeling as “any discursive process that involves using a lexical item, term or phrase to identify a person, place, group, event or any other key element in a narrative.” Labeling magic wind provides an interpretive framework for Journey that normalizes the vagarious power of the wind. As previously stated, the magic wind can transform an inanimate rock into a monkey, which is impossible. When a label becomes a receptive frame, it directs and restricts the reader’s responses to the narrative in question. The translated names of the magic wind in Waley’s Monkey are provided in Table 3 . We include Jenner’s and Yu’s translations as a cross-reference to identify better Waley’s reframing. The labels from his untranslated chapters are omitted from Table 3 , as their recasting is subject to selective appropriation.

The magic wind’s labels tend to be generalized in Waley’s translation, as shown in Table 3 . For instance, 赑风is a strong wind capable of melting bones and flesh of both mortals and immortals. Waley used the most common noun, “wind”, whereas Yu used the proper noun, “the Mighty Wind,” to emphasize this supernatural phenomenon. To remove the narrativity of the magic wind, Waley employs another delabelling technique called information compression (Example 9). It is worth noting that the 16th-century Chinese chaptered novel integrates both verse and prose as a defining generic feature. The widespread omission of wind narratives in the verses (Example 10) is another manifestation of Waley’s delabelling.

Example 9. 那怪不能迎敌, 败阵而逃, 依然又化狂风, 径回洞里, 把门紧闭, 再不出头。

At last, the monster could hold his ground no longer, and retreating into the cave bolted the door behind him (Waley’s translation, Chapter 19).

The monster, no longer able to resist his enemy, broke away and fled, turning himself into a hurricane again .He went straight back to his cave, shut the gates behind him, and did not come out (Jenner’s translation, Chapter 19).

Example 10. 行者近前仔细看处, 又见那怪雾愁云漠漠, 妖风怨气纷纷。

Going on a little way and looking closely, he saw that baleful clouds hung round the city and fumes of discontent surrounded it (Waley’s translation, Chapter 37).

Brother Monkey went for a close look and saw thick clouds of demoniacal fog hanging over it, as well as an abundance of evil winds and vapors of injustice (Jenner’s translation, Chapter 37).

In the story of the Kingdom of Crow-Cock, Monkey foresaw the haunting of demons through the ominous atmosphere of 怪雾demoniacal fog, 愁云thick clouds,妖风evil winds and 怨气 vapors of injustice (Example 10). Obviously, Jenner translated every detail, preserving the couplet rhetorically and the flashforward narratively. Waley, on the other hand, may have recognized the intertextual relationship between fog, clouds, wind, and vapors; consequently, he renounced the narrativity of wind while retaining the more palpably menacing clouds. In several couplets, Waley overlooked the narrative elements related to the wind, as seen in Chapters 5 10, and 37. The consistent exclusion of wind from both the couplets and narrative poetry suggests Waley’s aversion to these verses in the original tale, subsequently reducing its archetypal representation in Monkey .

Previous research on Waley’s abridged translation of Journey has primarily focused on the translation strategies at the textual level, with little attention paid to the translator’s ideological mediation and the consequent reframing effect on the translated literature. Given the numerous narratives of the magic wind that contribute to the mythic genre to which Journey belongs, the translator plays a crucial role in (un)selecting, emphasizing, and modifying the narrativity, and consequently, reshaping a Chinese literary canon. In light of the story/discourse distinction, this article proposes an inquiry into the narrativity of the magic wind in the source text. The results indicate that the magic wind is represented in narratives as a supernatural force of destruction, transportation, transformation, and a combination of transportation and flashforward. In Waley’s abridged version, the narratives of magic wind with the power of destruction and transformation are significantly diminished.

These are Waley’s reframing strategies: (I) Spatial and temporal reframing. The act of translation was embedded in the context of the Second World War. The source text’s heroism and optimism were tailored to the needs of the British reader; (II) Selective appropriation. Waley selected three episodes about pilgrims rescuing the country from demons maintaining the source text’s narrative structure. This selection perfectly suits the temporal and spatial context, providing confidence and optimism in the audience. Aligning with the depressed narrativity of magic wind, we observe that the readability and globality of the abridged translation are achieved by omitting the meta-narrative of religious fusion and the conceptual narrative of traditional Chinese scholars, such as Yin-Yang, The Eight Trigrams, Mutual Production, and Conquest, etc. Without these values, the translated Monkey becomes less of a cultural mosaic and more of a set of unusual tales. (III) Designation of reframing. Waley removed the labels of the magic wind from the narrative poetry and couplet sentences, whereas blending verse and prose is a defining characteristic of Journey . In addition to omission, his translation has a propensity for delabelling by substituting hyponyms for the proper nouns in the source text.

While an abridged translation is not expected to be identical to a complete one, narrative inquiry allows us to explore not only what is omitted and exaggerated, but also to investigate the covert ideological agenda. In particular, it sheds light on the intercultural priorities of translators as they decide what content is deemed as important to select and translate.

Data availability

The data are included in a supplementary file.

Abbott PH (2002) The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Google Scholar

Baker M (2010) Narratives of terrorism and security: “accurate” translations, suspicious frames. Critical Studies on Terrorism 3(3):347–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2010.521639

Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar

Baker M (2013) Translation as an alternative space for political action. Soc Mov Stud 12(1):23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.685624

Article Google Scholar

Baker M (2019) Translation and Conflict: A Narrative Account. Routledge, London and New York

Bantly FC (1989) Buddhist allegory in the Journey to the West. J Asian Stud 48(3):512–524

Boukhaffa A (2018) Narrative (re)framing in translating modern Orientalism: a study of the Arabic translation of Lewis’s The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror. Translator 24(2):166–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2018.1448681

Brownlie S (2006) Narrative theory and retranslation theory. Across Languages and Cultures 7(2):145–170. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.7.2006.2.1

Campany R (1985) Demons, gods, and pilgrims: the demonology of the Hsi-yu Chi. Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles. Reviews 7(1):95–115

Feng J (2010) Rebellion or abnormality: on the image of female demons in “Journey to the West.”. J Southwest Agri Univ 5:206–209. /冯俊 (2010) 反叛还是变态——论《西游记》中的女妖形象. 西南农业大学学报 5:206–209

Feng J (2014) The Magic powers of wind in Journey to the West. J Huaihai Insti Technol 6:33–37. /丰竞 (2014)《西游记》“风”的魔幻功能. 淮海工学院学报(人文社会科学版) 12(06):33–37

Harding S (2009) News as Narrative: Reporting and Translating the 2004 Beslan Hostage Disaster. Dissertation, University of Manchester

Harding S (2012) “How do I apply narrative theory?”socio-narrative theory in translation studies. Target 24(2):286–309. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.24.2.04har

Hsia CT (2016) The Classic Chinese Novel. Chinese University Press, Hong Kong, https://doi.org/10.2307/2718839

Kim KH (2017) Reframing the victims of WWII through translation. Target 29(1):87–109. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.29.1.04kim

Kruger JL (2009) The translation of narrative fiction: impostulating the narrative origo. Perspect Studi Transl 17(1):15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09076760902940120

Ji H(2016) A comparative study of two major English translations of The Journey to the West: Monkey and The Monkey and the Monk. J. Chinese Humanit 2(1):77–97. https://doi.org/10.1163/23521341-12340027

Jia H (2012) Characteristics and functions of mountain depictions in supernatural novels: taking “Journey to the West” as a prime example. J Liaocheng Univ 1:45–48. / 贾海建 (2012) 神怪小说中山岳描写的特点及作用——以《西游记》为中心. 聊城大学学报 1:45–48

Lai W (1994) From protean ape to handsome saint: the Monkey King. Asian Folklore Studies 53(1):29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178559

Li L (2017) A Discussion on the river imagery in “Journey to the West.”. J Honghe College 3:41–43. / 李莉 (2017) 浅谈《西游记》中的河流意象. 红河学院学报 3:41–43

Li X (2016) An exploration of the naming principles, methods, and sources of lesser demons in “Journey to the West.”. Chinese Cult Res 1:133–141. /李小龙 (2016). 《西游记》小妖命名原则、体例与来源试探.中国文化研究 1:133–141

Lian Z (2010) “Journey to the West” and Taoist life culture: a perspective on “caves” in “Journey to the West.”. Jiangxi Soc Sci12:179–183. /连振娟 (2010) 《西游记》与道教生命文化——以《西游记》中的”洞穴”为视角. 江西社会科学 12:179–183

Liu Z (2017) A Study on the narrative construction strategies by Richard Timothy’s abridged translation of “Journey to the West.”. J Yanshan U 5:31–36. /刘珍珍 (2017) 《西游记》节译本的叙事建构策略研究. 燕山大学学报 5:31–36

Luo W, Zheng B (2017) Visiting elements thought to be “inactive”: non-human actors in Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West. Asia Pac Translation Intercultural Stud 4(3):1–13

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Mi T (2022) The dilemma of the “other” and the breakthrough of the “self”: a study on the translation of female demon images in “Journey to the West” from the perspective of imageology. Foreign Lang Lit 38(6):122–128. / 宓田 (2022) “他者”的困境与”自我”的突围——形象学视域下《西游记》女妖形象的西译研究. 外国语文 38(6):122–128

Plaks AH (1977) Allegory in Hsi-Yu Chi and Hung-Lou Meng. In Chinese Narrative: Critical and Theoretical Essays. Princeton University Press, Princeton, p 163–202. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400856466.163

Prince G (2005) Narrativity. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory. Routledge, London, p 387–388

Puckett K (2016) Narrative Theory: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315158945-19

Pym A (2016) A spirited defense of a certain empiricism in Translation Studies (and anything else concerning the study of cultures). Translation Spaces 5(2):289–313. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.5.2.07pym

Rong L (2017) Real and fake eroticism in “Journey to the West” and the translation. Dushu (Reading) 5:90–96. / 荣立宇 (2017) 《西游记》中的真假情色及其翻译. 读书 5:90–96

Siepmann D (2015) A corpus-based investigation into key words and key patterns in post-war fiction. Funct Lang 22(3):362–399. https://doi.org/10.1075/fol.22.3.03sie

Škultéty MR (2009) Twentieth-century English renderings of the Xi You Ji: the afterlife of a classical Chinese novel. Translation Quarterly 53/54:116–155

Somers MR (1992) Narrativity, narrative identity, and social action: rethinking English working-class formation. Soc Sci Hist 16(4):591–630. https://doi.org/10.2307/1171314

Somers MR (1994) The narrative constitution of identity: a relational and network approach. Theory Society 23(5):605–649

Toolan M (2009) Narrative Progression in the Short Story. John Benjamins, Asterdam

Van Doorslaer L (2012) Translating, narrating and constructing images in journalism with a test case on representation in flemish TV news. Meta: Journal Des Traducteurs 57(4):1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.7202/1021232ar

Waley A (1942) Preface. In: Monkey. George Allen and Unwin, Orlando, p 9–10

Wang F, Humblé P (2018) Analysis of the Buddhist conversion of Great Sage: a corpus-based investigation of textual evidence from the English translation of the Journey to the West. Chinese Semiot Stud14(4):505–527. https://doi.org/10.1515/css-2018-0028

Wang F, Humblé P, Chen W (2019) A bibliometric analysis of translation studies: a case study on Chinese canon The Journey to the West. SAGE Open 9(4):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019894268

Wang F, Humblé P, Chen J (2020) Towards a socio-cultural account of literary canon’s retranslation and reinterpretation: The case of The Journey to the West. Critical Arts 34(4):117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2020.1753796

Wang F, Liu K, Zhang S (2023) A study on the translation of functional figure’s narratives from the perspective of Translator’s Behavior Criticism: the naming of lesser demons in “Journey to the West”. Foreign Lang Teaching 4:95–100. / 王峰, 刘克强, 张胜捷 (2023) 译者行为批评视域下功能性人物叙事英译研究——以《西游记》小妖称名为例. 外语教学 4:95–100

Wang W (2019) Listening to the voice of a translator: A study on Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West. Shandong Foreign Lang Teaching 40(1):116–124. /王文强 (2019) 倾听译者的心声——阿瑟·韦利的《西游记》英译本研究. 山东外语教学 1:115–124

Wang Y (2008) A discussion on lesser demons in “Journey to the West.”. Contemporary Literature 6:159–160. / 王亚培 (2008) 《西游记》小妖趣谈. 当代文坛 6:159–160

Wang Z (2014) A humanistic portrait of the female characters in “Journey to the West.”. J Huaihai Insti Technol 12:32–34. / 王镇 (2014) 《西游记》的女性人文写真. 淮海工学院学报 12:32–34

Wong L (2013) Seeking the golden mean: Arthur Waley’s English translation of the Xi you ji. Babel. Revue Internationale de La Traduction / International Journal of Translation 59(3):360–380. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.59.3.06won

Wong W (1996) Chinese literature, the creative imagination, and globalization. Macalester Int 3(1):37–60. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol3/iss1/8

Yang V (2012) A masterpiece of dissemblance: a new perspective on Xi You Ji. Monumenta Serica 60(1):151–194. https://doi.org/10.1179/mon.2012.60.1.005

Yang Z (2018) A Study on the Narrative Functions of Ming and Qing Chaptered Novel. Science Press, Beijing, /杨志平 (2018) 明清小说功能性叙事研究. 科学出版社,北京

Yuan X (2020) A metaphorical study of the female images in “Journey to the West.”. J Lanzhou Insti Edu 4:7–8+77. / 袁兴群 (2020) 《西游记》中女性形象的隐喻研究. 兰州教育学院学报 4:7–8+77

Yu AC (2012) The Journey to the West. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, Shanghai, (Transaltor)

Zang H (2010) Women, goddesses, and female demons under the patriarchal discourse: the female figures in “Journey to the West. J Shanxi Norm Univ 6:22–25. /藏慧远 (2010) 男权话语下的女人、女神、女妖——《西游记》女性形象分析. 山西师大学报 6:22–25

Zhang H (2004) Rethinking the absence of female: the characterization of female figures in “Journey to the West.”. Stud Ming-Qing Fiction 2:67–77. /张红霞 (2004) 女性”缺席”的判决: 论《西游记》中的女性形象塑造. 明清小说研究 2:67–77

Download references

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my MA student Wang Dandan from Jilin University, who collected and analyzed data under my supervision. This work is supported by the Project for the Taishan Scholar of Shandong Province (Young Professional Programme Grant Number: 20221105).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Translation Studies, Shandong University, Weihai, China

Feng (Robin) Wang

College of International Studies, Honghe University, Mengzi, China

Keqiang Liu

Department of Applied Linguistics, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

Philippe Humblé

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

F.W. designed the research and wrote the paper; K.L. designed the bilingual corpus and analyzed the data; and P.H. revised and polished the paper. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Keqiang Liu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed content

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

All data underlying the paper, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, F.(., Liu, K. & Humblé, P. Reframing the narrative of magic wind in Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West : another look at the abridged translation. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 876 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02397-0

Download citation

Received : 11 November 2022

Accepted : 16 November 2023

Published : 27 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02397-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Journey to the West Research

A repository for research on the great 16th-century chinese classic, tag monkey magic, archive #39 – journey to the west adaptations.

The Journey to the West Research blog is proud to host an entry by our friend Monkey Ruler ( Twitter and Tumblr ). They have graciously written an essay on the global nature of Journey to the West adaptations, as well as provided a link to their ongoing project recording JTTW media (fig. 1). As of the publishing of this article, it includes a long list of almost 570 movies, 90 TV shows, and 160 video games! – Jim

Fig. 1 – Depictions of Sun Wukong from adaptations produced over 50 years apart: (left) Havoc in Heaven (Danao tiangong, 大鬧天宮 , 1961) and (right) Monkey King: Hero is Back (Xiyouji zhi Dasheng guilai, 西遊記之大聖歸來, lit: “Journey to the West: Return of the Great Sage,” 2015) ( larger version ). Courtesy of Monkey Ruler.

I. Media adaptations