The future of farm tourism in the Philippines: challenges, strategies and insights

Journal of Tourism Futures

ISSN : 2055-5911

Article publication date: 12 March 2021

Issue publication date: 22 April 2024

This study aims to draw observations on the current status and potentials of the Philippines as a farm tourism destination and identify the underlying factors that inhibit farm tourism development. It intends to gauge the challenges that Filipino farmers face in diversifying farms and operating farm sites and uses these challenges in crafting strategies and policies for relevant stakeholders. It also provides Philippine farm tourism literature to address the limitations of references in the topic.

Design/methodology/approach

The study adopts an exploratory type of inquiry method and secondary data collection from various sources, such as published journal articles, news articles and reports, to gain insights and relevant information on farm tourism. The study also uses a threats, opportunities, weaknesses and strengths analysis approach to develop competitive farm tourism strategies.

The Philippines, with vast agricultural land, has the necessary base for farm tourism, and the enactment of the Farm Tourism Development Act of 2016 bridges this potential. With low agricultural outputs, the country draws relevance for farm tourism as a farm diversification strategy to supplement income in rural communities. While having these potentials, crucial initiatives in physical characteristics, product development, education and training, management and entrepreneurship, marketing and customer relations and government support must be implemented. Farmers' lack of skills, training and capital investment potential to convert their farms into farm tourism sites serves as the major drawback. Thus, developing entrepreneurial and hospitality skills is crucial.

Originality/value

This work presents a historical narrative of initiatives and measures of the Philippine farm tourism sector. It also provides a holistic discussion and in-depth analysis of the current state, potentials, strategies and forward insights for farm tourism development.

- Farm tourism

- Agri-tourism

- TOWS analysis

Yamagishi, K. , Gantalao, C. and Ocampo, L. (2024), "The future of farm tourism in the Philippines: challenges, strategies and insights", Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 87-109. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-06-2020-0101

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Kafferine Yamagishi, Cecil Gantalao and Lanndon Ocampo.

Published in Journal of Tourism Futures . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The Philippines has one of the fastest growing economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region, with an average growth rate of 6.3% (i.e. 2010–2016 coverage) and a 6.7% growth rate in 2017, as reported in the ASEAN Economic Integration Brief (2019) . As an agricultural country, 47% of its land area is intended for agriculture OECD (2017) with a recent reported sectoral growth of 2.87% in the third quarter of 2019 comprising primarily of crops and livestock, poultry and fisheries ( PSA, 2019 ) . As of January of 2018, about 10.9 million Filipinos were employed in the sector, which accounts for 26% of the national employment of the same month. This growth is insignificantly higher than its 25.5% share in January 2017. Unlike in the USA and Israel, where farmers are considered as middle-class citizens due to their high productivity ( Tarriela, 2016 ), which is ten times higher than the productivity of the country at 2.8%, Filipino farmers are still classified poor; thus, the need to provide them with a supplementary source of income. The country's agricultural sector has been underperforming since 1961. Globalization, industrialization and development encroachment are threatening small farms, as it is evident that farmers are forced to sell their lands and work due to industrialization ( Ghatak and Mookherjee, 2014 ). On this note, there is a need for Filipino farmers for the provision of the latest trends and technological advances in the field of farming to be on par with other ASEAN countries. .

In the Philippines, almost half of the population resides in rural areas that depend on agriculture as their primary source of income; among them are the indigenous people, landless farmers and fishermen ( Briones et al. , 2017 ). As an archipelagic country, it has diverse natural resources, rich cultural heritage, abundant agricultural produce and ideal sceneries. The country could access these resources in agriculture and address relevant issues vis-à-vis both the agriculture and tourism sectors. These components constitute an emerging type of tourism in the country, farm tourism – a sub-sector of rural tourism which focuses on providing an experience that endorses the very concept of farming and farm living ( Roberts and Hall, 2001 ). Rural tourism is defined as “a form of tourism that takes place in rural areas and involves the exploitation of natural and anthropogenic tourist resources of the rural area, and the conduct of social and economic activities that generate benefits for local communities” ( Dorobantu and Nistoreanu, 2012 ). It has recently been considered a viable approach to promote the countryside potentially and get the community involved ( Amir et al. , 2015 ). It is especially valuable in areas where traditional agricultural activities are decreasing ( Hoggart and Buller, 1995 ; Cavaco, 1995 ). The tourism and natural resource management literature are starting to take an interest in farm tourism because of its capability to provide potential benefits to local development ( Iorio and Corsale, 2010 ; Mastronardi et al. , 2015 ; Karampela and Kizos, 2018 ), especially with the alarming decline of the agriculture industry ( Kuo and Chiu, 2006 ). Ollenburg and Buckley (2007) pointed out that farm tourism enterprises are formed by the resulting combination of the commercial constraints of regional tourism, the non-financial attributes of family businesses and the inheritance nuances of family farms. Farm tourism paves the way to inclusive and sustainable agricultural and rural development as it opens possibilities for diversification of income for small-scale farmers while promoting sustainable agricultural systems and community involvement and participation (SEARCA, 2017).

The Philippines has enacted a national legislative measure, the Republic Act 10816 (R.A. 10816), popularly known as the Farm Tourism Development Act of 2016, which provides an overarching framework for developing and promoting farm tourism activities in the country. It defines farm tourism as “the practice of attracting visitors and tourists to farm areas for production, educational and recreational purposes”. It includes any agricultural or fishery-based activity for farm visitors, tourists, farmers and fisher folks who want to be educated and trained on farming and its related activities. Also, it provides a venue for outdoor recreation and accessibility to family trips. The country has set standards for the farm tourism industry and formalizes the industry players to boost sectoral growth through the promulgation of R.A. 10816 further. As farm tourism develops under the branch of nature-based tourism, it focuses on low-impact, nature-based and community-based activities involving the locals in ways culturally, socially and economically cultivating. In the Philippines, farm tourism accounts for 20%–30% of the overall tourism market ( Padin, 2016 ).

With the Department of Tourism (DOT) data, the country's tourism policy and implementation arm, more than 170 farm sites were accredited ( Talavera, 2019 ) and are mostly concentrated in the Luzon area, the Philippines' largest island in its northern part. Most travel agencies and tour operators in the country are not offering stand-alone farm tours but merely include one to two farm visits in their usual itinerary. As most of the tourism destination sites in the provinces are sun-sea-sand attractions, the country is less known for its agricultural sites. However, as roughly 40% of the land use is devoted to agriculture ( Talavera, 2019 ), developing and promoting these farm sites could not only generate additional revenue for the tourism sector but could also create some scale economies as crucial components and productive factors for farm tourism already exist, without altering the farm's orientation ( Veeck et al. , 2006 ). As the government is pushing for efforts to develop the farm tourism sector, more opportunities become available for local farmers to augment their income and diversify their lands. Thus, farm tourism does not only offer alternative tourist attractions in the country, but it also promotes agricultural farms and creates an outlet for farmers to sell their produce.

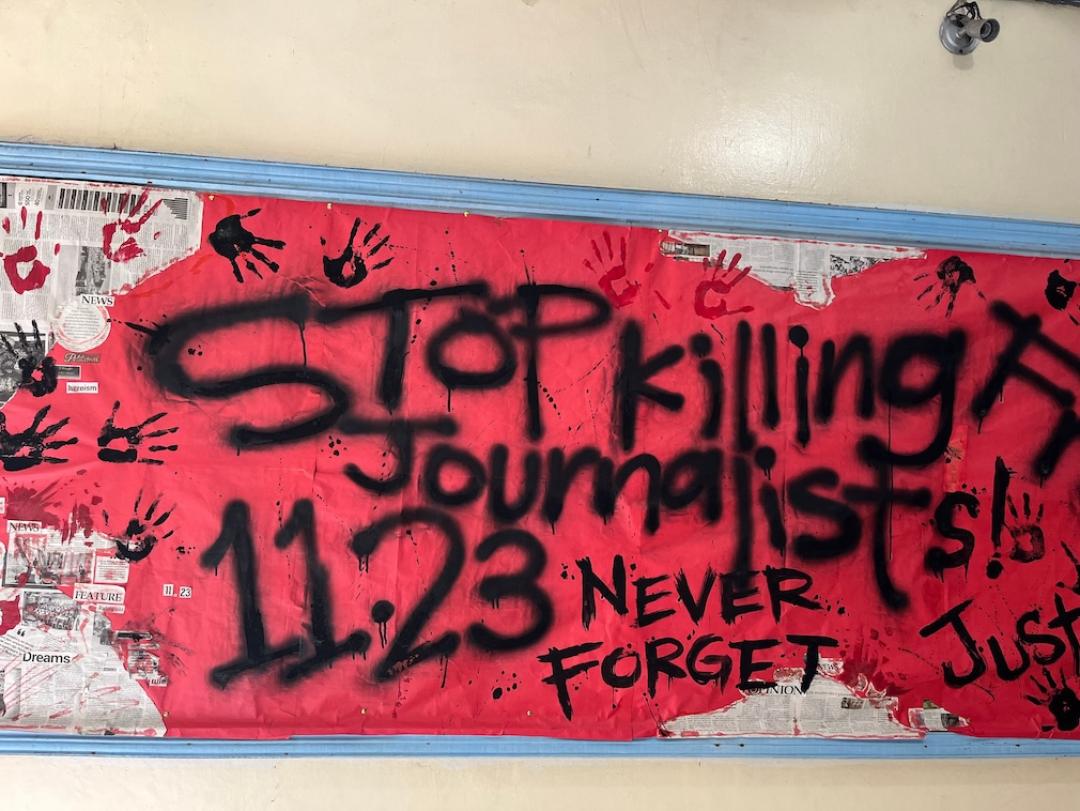

Despite such efforts of the Philippine Government for developing the farm tourism sector, several challenges remain roadblocks to development, and some directions seem to be counterintuitive. For instance, Montefrio and Sin (2019) noted that agritourism (i.e. farm tourism) in the Philippines is driven by a “complex elite network” of state and private entities which, along with uneven power dynamics, allows conditions favoring old and new landed elites while keeping marginalized small farmers at a distance. Addressing these challenges and attempting to offer possible strategies to overcome them require a country-level discussion that thoroughly provides an in-depth inquiry and analysis of the sector's current status and performance, along with managerial and policy insights on ways forward. Initiatives of this kind have been reported in the literature for decades. For instance, Pearce (1990) described the social aspects of farm tourism in New Zealand based on social situations analysis. Davies and Gilbert (1992) reported the development of farm tourism in Wales. From a gender perspective, Caballé (1999) brought insights from farm tourism in Spain. Potočnik-Slavič and Schmitz (2013) analyzed farm tourism development in nine European countries (UK, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Croatia, Slovenia and Ireland) and presented some major observations. Nematpour and Khodadadi (2020) examined the potential socioeconomic development of Iran with farm tourism as the driving force. However, despite such importance of conducting this report, such an initiative in the Philippines is lacking and presenting a rigorous discussion of the country's challenges and possible directions for developing the farm tourism sector becomes an imperative.

a historical narrative of Philippine farm tourism initiatives and measures;

an analysis of the potentials of the country as a farm tourism destination;

an inquiry on the underlying challenges that inhibit the country in developing numerous world-class farm sites in contrast to other sites in leading Asian countries; and

an in-depth investigation and analysis of the possible strategies, initiatives and policy insights of the relevant stakeholders (e.g. the government, farm tourism operators, among others) in addressing the challenges of farm tourism development.

Likewise, this study addresses the limitations of the collection of the relevant literature of Philippine farm tourism and intends to provide a rigorous investigation that will provide a reference work on the topic. Aside from the practical contribution of this work, analyzing the case of farm tourism of the Philippines offers an interesting set of insights to farm tourism as a domain field of study. First, farmers in the Philippines are generally classified as poor, and the agricultural output is relatively low despite having vast agricultural land. Secondly, the output of the tourism industry in the country is relatively low compared to other countries in the ASEAN region despite the presence of diverse natural resources, ideal sceneries, abundant agricultural produce and rich cultural heritage. Finally, the Philippine Government is committed to the development of farm tourism, and investments in various initiatives become evident. The nexus of these current socioeconomic and political conditions, along with various structural challenges, provides an interesting discussion on how farm tourism can be advanced in such an environment.

To address these gaps, this study used content data analysis from various literature, such as published journal articles, news articles and reports in drawing observations. This type of approach is ideal for gaining insights and in-depth information regarding the country's farm tourism. Content data analysis is a process used to describe written, verbal or graphic communications and creates a quantifiable description from qualitative data. Direct content analysis was adopted in sorting out the cases of the examined phenomenon, highlighting data, followed by labeling the highlighted information through predetermined codes. Data that were coded from the existing coding scheme would be given a new code. Direct content analysis foresees the variables of interest or the relation among variables determined through the coding scheme or relation between codes ( Mayring, 2000 ). It also uses the existing theory or prior research by identifying the critical variables in the coding categories ( Potter and Levine-Donnerstein, 1999 ). While we acknowledge the limitations of content analysis pertaining to data and information quality, the use of primary data sourcing methods (e.g. focus group discussion, interviews, surveys) may not be relevant at this point in Philippine farm tourism development as the sector is still relatively young with a limited pool of experts on the topic. The direct content analysis then generated the current status and challenges of the country's farm tourism sector. Some case illustrations in the local regions of the country were utilized to describe better the potential of farm tourism along with its corresponding challenges. This set serves as inputs to the weaknesses–opportunities (WO) analysis – a strategy design tool that is an extension to the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis. The leverage of the WO analysis lies in its capability of designing strategies that access external opportunities while reducing internal weaknesses ( Weihrich, 1982 ). Policy insights were then identified from the strategies generated by the WO analysis. The entire process of this work serves as a platform for developing an in-depth analysis of possible strategies and policy insights for farm tourism in the Philippines.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the background of farm tourism and its comprehensive benefits. Section 3 presents the current status and potentials of the farm tourism sector, as well as its challenges and strategies. Section 4 provides an in-depth “mini-maxi” strategies for addressing the sector's challenges. Policy insights are outlined in Section 5. It ends with a conclusion and discussion of the future work in Section 6.

2. Background of the study

2.1 farm tourism: background, issues and concerns.

With the onset of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agriculture is considered the largest employer globally, which provides the livelihood for 40% of the current global population. Developing countries have barely 30% of the total agricultural production, while high-income economies have 98%, which suggests that enormous opportunities for developing countries like the Philippines are available in agribusiness. One of the targets of the Zero Hunger Goal of the UN SDGs is to double the agricultural productivity and income of small-scale food producers in 2030, particularly women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment. The eighth UN SDG, on the other hand, is to have a Decent Work and Economic Growth, which is targeting in the promotion of development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services. The notion of farm tourism attempts to address these two important goals, as discussed in the current literature ( Iorio and Corsale, 2010 ; Mastronardi et al. , 2015 ; Karampela and Kizos, 2018 ). Like other countries, the Philippines has already made a significant step by promulgating the R.A. 10816, which provides a set of national policy guidelines on the development of farm tourism.

Tourism is a significant economic activity to the rural economies, characterized by low income from farming with defined economic opportunities ( Talbot, 2013 ). Developed economies viewed tourism as a response to employment and livelihood gaps in rural areas ( Sharpley and Vass, 2006 ). Due to the widespread impact of agriculture, in many countries, tourism is currently the focus of farm diversification ( Fisher, 2006 ; Garrod, 2011 ). Governments worldwide have recognized the need to encourage farm enterprises that provide alternative sources of income to address the threat of rural area desertion and agricultural neglect, resulting in farm diversification ( Hjalager, 1996 ). Farm-based tourism has been very successful in many parts of Europe and has increasing popularity in Canada, the USA and New Zealand ( Busby and Rendle, 2000 ). This movement is greatly attributed to the changing policy context of agriculture in developed nations ( Davies and Gilbert, 1992 ; Walford, 2001 ). These agricultural policies have experienced some fundamental changes over the past 50 years ( Sharpley and Vass, 2006 ). Agricultural policy reforms, as well as changes in social, political and economic conditions in Norway, for instance, have encouraged their farmers to diversify their farms to generate additional income ( Haugen and Vik, 2008 ).

Farm tourism is expected to encourage employment in rural communities as well as the vitality and sustainability of these areas ( Davies and Gilbert, 1992 ; Garcia-Ramon et al. , 1995 ; Sharpley and Vass, 2006 ; Forleo et al. , 2017 ) and is considered as part of the shift in their economic base ( Blekesaune et al. , 2010 ). Garcia-Ramon et al. (1995) were optimistic by noting that while farm tourism generates new job opportunities, it contains a multiplier effect that supports other local economic sectors. Additionally, farm tourism is considered a value-adding activity for farmers as it strengthens the resource base of the farm, builds upon the farm and the competency of farmers and on what the farm means in terms of mentality and lifestyle ( Brandth and Haugen, 2011 ). However, tourism on farms is small-scale and economic viability is considered not always good ( Forbord et al. , 2012 ). One of the earliest opposing viewpoints about farm tourism was presented by Maude and Van Rest (1985) , which argued that farm tourism returns are small brought about by rigorous planning regulations. Hjalager (1996) also identified the tendency of farmers to give priority to traditional agriculture as one of the drawbacks. Sharpley and Vass (2006) added that the desire of farmers for the development of farm tourism is rooted in an employment concept, rather than from a diversification motivation. These conditions have changed for the past 30 years, and governments have sorted out some of its challenges. Nevertheless, farm tourism covers a variety of services and products, and the combination of production on agricultural products and tourism can lead to an advantage of increased and efficient use of labor on a farm ( Fleischer and Tchetchik, 2005 ). Additionally, extending the notion of Mastronardi et al. (2015) , farm tourism offers the opportunity to farmers to sell their produce directly to the consumers, thus reducing transactions with commercial intermediaries, which would, in effect, dramatically increase their profit margins. In this scenario of direct interaction, farmers implement direct marketing initiatives and new product introductions with minimal market risk while consumers benefit from direct information exchange, strengthening of social relations and availability of local produce at competitive prices ( Mastronardi et al. , 2015 ). However, it is argued that farm tourism still lacks a comprehensive body of knowledge and a theoretical framework ( Oppermann, 1995 ) since only a handful of studies have conducted rigorous investigations on this area.

As diversification to farm tourism is increasingly considered as a viable development strategy in promoting a more diverse and sustainable rural economy while countering declining farm incomes, one of the major challenges identified in the domain literature is the lack of additional business and entrepreneurial competencies of farmers, who by nature of the agriculture sector, have the dominant productivity-driven mindset ( Busby and Rendle, 2000 ; Haugen and Vik, 2008 ; Phelan and Sharpley, 2012 ). Pesonen et al. (2011) considered these entrepreneurs' roles and skills as fundamental for rural tourism as new products and services must be introduced to meet ever-changing market demands at competitive prices. The transition from farming (or tourism on farms) to farm tourism is considered difficult as farmers are mostly in isolation with tourism, with a lack of knowledge, expertise and training in the field ( Busby and Rendle, 2000 ). Interestingly, some works have pointed out that women have higher motivation for agritourism (or farm tourism) than men ( McGehee et al. , 2007 ; Haugen and Vik, 2008 ). Besides these entrepreneurial skills, other economic variables such as food service, direct selling, public subsidies and other external factors such as proximity to urban or cultural centers are also determinants of farm income performance ( Giaccio et al. , 2018 ). Most recently, Da Liang et al. (2020) highlighted the match between farm image and farm experience activities as contributory to positive tourist response in farm tourism sites. Some current areas of interest in farm tourism have extended to the inclusion of culinary tourism experiences in agri-tourism destinations ( Testa et al. , 2019 ), educational rural farm tourism ( Cornelia et al. , 2017 ), recreation on farms ( Barbieri et al. , 2016 ), the combined recreational-educational rural tourism on farms ( Petroman et al. , 2016 ) and cultural integration on-farm activities ( Prayukvong et al. , 2015 ), among others. Note that this list is not intended to be comprehensive.

2.2 Benefits of farm tourism

The tourism industry perceives farm tourism as a medium for the diffusion of tourists away from the gateway cities ( Ollenburg and Buckley, 2007 ). These areas allow easy access to potential tourists ( Garrod, 2011 ). In Taiwan, Thailand and Japan, tourists gather to farms and partake in activities such as rice planting and vegetable harvesting. The majority of the farms have increased their income, and consequently profit, by adding farm tourism activities in their operations ( Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). Haghiri and Okech (2011) agreed that farm tourism activities in their countryside or province are generally viewed as alternative income sources, usually above the earnings from various on-farm activities. It aims to promote tourism in rural areas and balances development through economic dispersal and providing opportunities in the countryside. Gabor (2016) noted that farm tourism is an excellent example of inclusive growth for the local communities. Some reports from Australia, Taiwan, Thailand, the USA, Costa Rica and some European countries indicated that jobs and revenues are created in local communities through farm tourism activities.

Furthermore, farm tourism conserves and preserves the environment through the notion of sustainability and its nature- and community-based tourism concept. Recio et al. (2014) highlighted that while agriculture maintains the environment, farm tourism, on the other hand, enables the farmers to innovate and diversify their landscape for various purposes, and at the same time, protects the natural resources which would benefit tourism and other sectors. Aside from an environmental point of view, farm tourism also protects and promotes cultural traditions and develops a sense of pride and ownership to the locals while enriching the tourists' authentic cultural experience. At present, tourists yearn to embody the local rural experience and not merely become onlookers in the rural environment ( Cloke and Perkins, 2002 ). Farm tourism encourages visitors to experience firsthand the agricultural life ( Mansor et al. , 2015 ) and can be a catalyst for revival or strengthening rural traditions and culture. In farm tourism sites, tourists may know the differences and dynamics of culture of the locality, even with the tone or the accent of their dialect. This cultural impact of farm tourism and agritourism on a rural community is considered by Amelia et al. (2017) as the most important undertaking as it changes the cultural behavior and thinking of culture in contact with another culture.

Finally, farm tourism provides education about the importance and role of agriculture. The majority of the visitors are families with young children, community organizations and schools that set the significance of farm offerings in educating the public ( Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). It creates a mutual learning experience when farmers share their abilities and affirm their role in the community. This notion was supported by Gabor (2016) by citing that farm tourism represents the business of attracting visitors to farm areas generally for educational and recreational purposes ( Gabor, 2016 ). It encourages the development of a symbiotic relationship between the farmers and the tourists ( Busby and Rendle, 2000 ). If properly planned and managed, farm tourism bridges the gap and creates a harmonious relationship between the rural and urban communities.

3. Findings

3.1 status of the philippine agricultural sector.

The Philippines has roughly 30 million hectares of land, of which 9.7 million are considered agricultural. The agricultural industry portrays an important role in the Philippine economy and the development of the country. However, the country has lagged by neighboring ASEAN countries. As shown in Figure 1 , the productivity rate of the country is lower than Indonesia, with 3.73%, Malaysia 4.10%, Thailand 3.21, Myanmar 3.67 and Vietnam 4.16%. Note that these countries have also invested in farm tourism ( Leh et al. , 2017 ; Ahmad et al. , 2018 ; Nguyen et al. , 2018 ). With exports related to agri-food, the country is also underperforming based on the 2014 data with US$6.7bn earnings in comparison to other ASEAN countries, as shown in Figure 2 . In 2014, the Philippines exported US$6.7bn worth of farm products but imported US$8.6bn for a deficit of US$1.9bn ( Dar, 2017 ). Thailand transported US$38.4bn in farm products the same year abroad and imported US$12.9bn with a surplus of US$25.5bn. Indonesia has US$38.8bn in farm exports and US$17.5bn in agricultural imports for a surplus of US$21.3bn, while Malaysia has US$26.2bn in farm exports and US$18.3bn in agricultural imports for a surplus of US$7.9bn. On the other hand, Vietnam US$24.8bn in farm exports and US$13.4bn in agricultural imports for a surplus of US$11.4bn.

Such low agricultural productivity can be attributed to some of the challenges that the agriculture industry is facing nowadays. At present, there are widespread conversions of prime agricultural land partly due to rapid urbanization and population growth. For instance, there is a growing need for housing projects, residential villas and commercial properties, which have led to the immense conversion of agricultural lands not just in Metro Manila but in key cities across the country ( Cabildo et al. , 2017 ). The development trajectory has been extended to Visayas and Mindanao (i.e. two of the largest group of islands in the country), causing a tremendous shift in land use patterns. The Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR), the Philippine Government agency for the distribution of agrarian land, distinguished Negros Occidental and Misamis Oriental (i.e. provinces in the country) known for vast sugarcane and coconut plantations accordingly were among the top ten provinces with the highest number of land conversions ( Cabildo et al. , 2017 ). With such foregoing conditions, agriculture has been stagnant ( Beus, 2008 ), and farm output has declined due to human and external factors. Due to the complementary nature of farm tourism to agricultural activities, it is recognized as an alternative activity to diversify economic growth ( Tiraieyari and Hamzah, 2012 ). Thus, as part of the diversification efforts of Philippine agriculture, farm tourism is a potentially vital key in sustaining economic and environmental security.

3.2 Farm tourism in the Philippines

Farm tourism started in the country in the 1990s. The DOT, the Philippine Government agency for tourism, has long seen the importance of farm tourism before the promulgation of R.A 10816. In 1991, DOT and United Nations Development Program (UNDP) worked together and developed a Philippine Tourism Master Plan, which aimed to develop tourism in a sustainable manner and farm tourism is on the list. DOT also spearheaded the Philippine Agri-Tourism Program as early as 1999. In 2002, DOT and the Department of Agriculture (DA) issued a joint circular order that identified the ten farm sites in the country. The DOT accreditation has set the minimum standards for all operations and maintenance activities to guarantee tourist satisfaction. Accreditation of farm sites is voluntary and shall be valid for two years. Farm tourism sites in the country are categorized into two: day farms and farm stays. Day farms are usually located near highways, while farm stays offer accommodations and dining experience. The accreditation is based on the minimum standard set by the DOT based on the following requirements: location, facilities and amenities, infrastructure, operation, safety and security and sanitation. Accreditation may be suspended or revoked for any violation of the standards. In 2012, a house bill in the Philippine Congress had been filed to promote farm tourism in the country by providing tax credits to registered activities to offset the expenses in venturing into farm tourism and provide technical assistance to farmers entering the business. In 2016, the bill was signed into law, the R.A 10816, or the Farm Tourism Development Act of 2016, which encourages, develops and promotes farm tourism. Subsequently, some provinces, including Bukidnon, Batangas, Tarlac and Tagaytay, are well recognized for their potential to become a farm tourism destination ( Nawal, 2013 ).

investment promotion and financing;

market research, trends, innovations and information;

accreditation of farm tourism camps;

market promotion and development;

agriculture and fishery research, development and extension;

institutional and human resource development; and

infrastructure support ( Makati Business Club (MBC), 2016 ).

The law also mandates to establish a Farm Tourism Board that shall recommend projects for funding opportunities through the DOT, the DA, the Tourism Infrastructure and Enterprise Zone Authority (TIEZA), the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) and other concerned government agencies concerning farm tourism development. The board is tasked to increase farm tourism awareness through relevant marketing campaigns. In cooperation with DA, DOT is mandated to accredit farm tourist sites that are voluntary and valid for two years. Historically, DOT has been accrediting farm sites since the 1990s under the provision of Executive Order No. 292, following the rules and regulations to govern the accreditation of farm sites. To further strengthen the institutionalization of farm tourism in the country, and to further solve the issues of hunger and poverty, and to sustain food security, the national convergent program was launched in line with R.A 10816. Lazara (2017) , a Philippine senator explaining that the essence of the law is for the government to recognize tourism coupled with agriculture could bring the value of agriculture in the economic and cultural development of the country, serves as catalysts of agricultural and fishery development and provide additional income to the farmers and fisherfolks. It also reiterated that the most important provision of the law is its encouragement to establish at least one farm tourism camp in every province (Lazaro, 2017).

3.3 Potentials of farm tourism

Cebu has a dynamic trade and commerce, particularly in agriculture, since it has a high demand for agri-fishery products driven by the numerous hotels, restaurants, fast-food chains, supermarkets and other corporate buyers Galolo, 2016 ).

The province is in an avian influenza-free region and can sell poultry products anywhere in the country and even abroad ( Galolo, 2016 ).

Cebu has a steady population growth and increases per capita consumption, furthering the demand ( Galolo, 2016 ).

Farm-based tourism is a good diversification strategy if farms are located or close in central districts and located near scenic attractions with several outdoor activities to enjoy ( Walford, 2001 ). Farm-based tourism works best in areas with high scenic and heritage values ( Walford, 2001 ) in which Cebu possessed along with the numerous cultural and natural attractions it is known for. Most vegetation comes from the southern part of the province in the municipality of Carcar City and Dalaguete, which is also known for its tourist attractions ( Lorenciana, 2014 ).

Opportunities are available for agriculture and fishery to flourish further in the province. However, like other provinces in the country, Cebu is not maximizing its full potential in this sector. Cebu is already a well-known tourist destination among local and foreign tourists, and inculcating farming with tourism can potentially alleviate the popularity of farming in the province. Such an approach encourages a sense of gratitude among tourists to the food they are taking in and inspires the youth to be more involved in the agriculture industry. Nevertheless, Cebu needs to manage and strengthen its agricultural and farm resources to reap low-hanging fruits in farm tourism.

3.4 Challenges and strategies of Philippine farm tourism

Amidst the potentials that the farm tourism sector has and the efforts that the Philippine Government has taken, the sector is possibly faced by impediments that are likewise experienced by other farm tourism sectors worldwide. Based on the reports gathered, some factors impede the growth of farm tourism in the country. A thematic presentation is shown here.

3.4.1 Physical characteristics.

The general concern of the farmers in the country is the erratic climate brought about by the possible effects of climate change, which is considered a threat to their crops ( Lorenciana, 2014 ). Furthermore, the country has limited agricultural lands and is worsened by the effects of industrialization through land conversions credited to the high popularity and demand for real properties such as housing and condominium development. Cebu, as a case in point, has mountainous topography that limits agricultural potential. Due to its strategic position, Cebu also has a highly urbanized image. This position curbs further expansion of agricultural development in the province. Most farms are small-family owned, commonly situated in upland slopes, paling compared to the farms in the Luzon area where the topography is generally plain.

3.4.2 Product development.

The DA has a positive outlook on farm tourism as a long-term solution to improve the quality of living of the farmers and fishers ( Villarin and Miasco, 2017 ). However, many farmers lack the necessary resources (i.e. financial, technical and human resources) in diversifying their farms into a farm tourism business ( Moraru et al. , 2016 ). This may be due to the limited and inequitable access of the farmers to the provisions of the government and the private sector for these resources. There is an insufficient number of farm tourism sites and poor consistency in the quality of farm tourism products demonstrated by a few farm tourism operations that are market-ready ( Moraru et al. , 2016 ). The majority of the farm sites in the country cannot compete with those in other Asian countries (e.g. Taiwan and Japan) due to its lack of innovation and marketing. This manifestation is also heightened by the lack of understanding and application of the contextual research of farm tourism supposedly carried out by Philippine universities.

3.4.3 Education and training.

There is an aging populace of farmers in the agricultural sector, and a critical need for succession becomes obvious ( Santiago and Roxas, 2015 ). Only a few people are engaging in agriculture nowadays. Agriculture has been typecasted as a low-level career in the country. The University of the Philippines-Los Banos, College of Agriculture, the top agricultural university in the country, reported that enrollment had declined drastically from 1980 with 51% enrollees down to 43% in 1995 to 4.7% in 2012 ( Cinco, 2012 ). In 2014, official reports highlighted that the average age of Filipino farmers is 57 years old, a few years before retirement ( Casauay, 2014 ). Furthermore, the young generations (i.e. millennials, generation X) witness their parents grow old and poor with farming and do not positively view agriculture as a lucrative career ( Alave, 2011 ). The PSA reported the most recent estimates that the farmers have the highest poverty incidence in the country, with 34.3% in 2015, closely followed by the fishermen at 34% ( PSA, 2017 ). These estimates are corroborated by the latest agricultural wage rate survey in 2018, which highlights that the average daily income of farmers is posted at Php 306 (roughly US$6) or a monthly rate of Php 8,000 (US$157) ( PSA, 2019 ). The positive outlook on agriculture can be bridged by increasing the farmers' per capita income that can be potentially addressed through supplementary income sources such as, including, among others, farm tourism. On this note, excellent education and skills development on farm tourism become crucial in the provision of marketable farm tourism products.

At present, the Philippine Government encourages the formation of farm tourism camps or farm schools all over the country to serve as avenues of learning for farmers. The two agencies (i.e. DOT and DA) are tasked under R.A. 10816 to lead in the establishment of at least one farm tourism camp in every province in the country. In 2012, the Philippine Congress enacted into law the R.A. 10618 or the Rural Farm Schools Act that promotes sustainable agricultural productivity and rural development by empowering the human capital in the countryside through access to avenues of learning suitable to the needs of the rural agricultural communities. The rural farm school curriculum is intended to follow the core secondary education curriculum of the Department of Education (DepED) with add-on courses highlighting agri-fishery arts. The last two academic years in the rural farm school educational system is designed to focus on integrative learning across all subject disciplines in the curriculum with an emphasis on farm entrepreneurship theory and practice and its promotion as a tool in cultivating local entrepreneurs, revitalizing rural economies and repopulating rural communities.

3.4.4 Management and entrepreneurship.

Phelan and Sharpley (2012) argued that the current dynamics of the farm tourism business require farmers to possess a certain degree of entrepreneurial skills that remain lacking among them. McNally (2001) and Grande (2011) suggested that farmers have great opportunities to cater to tourists, but they need the necessary skills to diversify their farms and accommodate tourists in a sustainable manner that does not affect their regular farming and create a new business venture. It is widely understood that entrepreneurial skills are among the most important aspects of modern-day farming ( Smit, 2004 ). Farmers are recognized these days as entrepreneurs that require new skills and capabilities to develop to become or remain competitive ( McElwee, 2006 ). In the Philippine context, the DA has taken steps to address the lack of entrepreneurial skills among farmers by encouraging local government units in identifying specific needs of farmers and addressing these needs by conducting seminars and training, which would highlight these required skills in farming ( Lorenciana, 2014 ). The concept of agripreneurship has also been in the limelight of the Philippine Government by incorporating it into the Philippine Agriculture 2020 Plan. Despite these efforts, Santiago and Roxas (2015) remained reserved and noted that one of the leading causes of failure of government efforts in agriculture has been on increasing productivity rather than on entrepreneurial initiatives. Santiago and Roxas (2015) noted that shifting from productivity to entrepreneurial activity would allow more selling on value-added produce than producing more of the same crops.

3.4.5 Marketing and customer relations.

Shifting from the traditional agriculture mindset to diversifying it towards farm tourism requires the necessary skills in marketing and customer relations among farmers. The majority of the farm tourism businesses lacks the training to render useful service, as well as marketing skills to the tourist ( Sharpley, 2002 ). Moraru et al. (2016) added that most farmers and their workers do not possess the skills to ensure success in farm tourism. There is limited relevant information provided to the farmers regarding tourism markets and trends ( Moraru et al. , 2016 ). Consequently, ineffective communication exists among farmers and the market in terms of promoting their farms ( Moraru et al. , 2016 ). There are also inadequate knowledge and skills in customer management ( Haghiri and Okech, 2011 ). These conditions are prevalent in the Philippine context ( ESFIM, 2009 ). At the micro and macro level, among the challenges that the country is facing are the lack of market information and the inability to analyze this information, poor transport infrastructures and poor farm product quality standards ( ESFIM, 2009 ). Most of these challenges are highly associated with the lack of marketing and customer relation skills of the farmers at the micro-level as they are mostly dependent on market intermediaries in selling their products. With the lack of farm to market access, farm tourism can bridge such limitations by providing opening opportunities for direct selling.

3.4.6 Government support.

Moraru et al. (2016) pointed out that government support is crucial to farmers in harnessing their business growth and encouraging and educating the potential tourists about farm tourism. This presents a new challenge to the Philippine Government. The main landmark of the government's efforts on promoting and developing farm tourism is the enactment of the R.A. 10816 or the Farm Tourism Development Act of 2016, which highlights the provisions on creating the Farm Tourism Development Board, investment promotion, financing and incentives, market research and information, accreditation of Farm tourism camps, market promotion and development, agriculture and fishery research, development and extension, institutional and human resource development and infrastructure support. Less than five years after its promulgation, the policy has not been fully implemented down to the micro-level. Currently, DOT has accredited roughly more than 170 farm tourism sites in the country. Despite such efforts, the Philippine Government has not addressed crucial issues such as widespread public awareness of farm tourism and its benefits, poor understanding of farm tourism among relevant government agencies and limited marketing efforts exerted by the local government units, among others. As DOT accreditation is voluntary, operators become hesitant to undergo the accreditation process without enough understanding of its benefits farm tourism. Thus, public awareness is crucial at the outset of any marketing efforts. Furthermore, there is poor coordination of relevant government agencies in the promotion of farm tourism. For instance, the promotion of activities of local government units on farm tourism is often not coordinated with the DOT as a national tourism agency. Additionally, the local tourism offices highly depend on farm tourism operators' individual marketing efforts in promoting their sites.

4. Weaknesses–opportunities (WO) analysis

With the identified benefits in the current literature and the challenges faced by the farm tourism industry in the Philippines, a WO analysis is presented here. WO analysis is one of the distinct strategic groups of the threats, opportunities, weaknesses and strengths (TOWS) matrix developed by Weihrich (1982) . The TOWS matrix is an extension of the widely adopted the SWOT analysis that scans internal factors (strengths and weaknesses) and external environment (opportunities and strengths). The main objective of the TOWS matrix is to provide means in developing strategies based on the logical two-factor combinations of internal and external factors of SWOT. The WO strategies, also termed as a mini-maxi (competitive) strategy, are taking advantage to access external opportunities while reducing internal weaknesses ( Weihrich, 1982 ). Some relevant applications of the TOWS matrix include the Basel norms ( Kapoor and Kaur, 2017 ), strategic marketing ( Proctor, 2000 ), strategic choice ( Kulshrestha and Puri, 2017 ), strategy formulation ( Dyson, 2004 ; Wang and Hong, 2011 ; Dandage et al. , 2019 ) and strategic natural resources management ( Kajanus et al. , 2012 ). TOWS matrix has also been applied specifically in the tourism domain such as formulation of tourism destination development strategies ( Goranczewski and Puciato, 2010 ), strategic marketing planning for tourism ( Wickramasinghe and Takano, 2010 ), ecotourism development ( Hong and Chan, 2010 ; Asadpourian et al. , 2020 ) and strategy identification for a food firm ( Ingaldi and Škůrková, 2014 ), among other applications. Among the four strategic groups, the development of the WO strategies is deemed appropriate for creating development strategies for the farm tourism sector as the sector is mostly dominated by weaknesses but is operating in a favorable environment. Details for the WO strategies for farm tourism are provided in Table 1 .

With the given WO analysis of farm tourism in the country, strategies are developed to mitigate the weaknesses while advancing farm tourism opportunities. First is the promotion of urban and vertical farming in cities that address the limitation of agricultural land for farm tourism. Urban vertical farming produces food on vertically inclined surfaces and an agricultural technique that involves large food production mostly in high-rise buildings with controlled environmental conditions for fast growth and planned production ( Kalantari et al. , 2018 ). United Nations (2007) reported that the world population would rise to 9 million in 2050, mostly will live in urban areas. Thus, urban vertical farming can potentially aid the country or the locality in meeting the elevating demand for an agricultural product without additional farmlands. Urban vertical farming has been applied in Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, China ( Kalantari et al. , 2018 ), among others. Travel trends are dynamic with the changing market preferences and are paralleled with innovating products to maintain a competitive advantage. Farm tourists are characterized by a high educational level, with an age range belonging to millennials and generation X ( Dubois et al. , 2017 ). In generational marketing, millennials are adventurous and often travel for experiences ( Machado, 2014 ); thus, offering farm tourism as an alternative or additional attraction can benefit both farmers and the government. Therefore, government support for farm tourism is inevitable to harness its economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts that will eventually enhance the performance of Philippine tourism. Traditionally, farms are more inclined to produce agricultural products as factual evidence of their productivity; however, with the diversification direction of farm tourism, these farms must conform to the operational needs of farm tourist sites. This conformity involves acquiring new skills to operate farm sites profitably. Training and seminars shall be initiated and spearheaded by relevant government agencies (e.g. DOT, local tourism offices, LGU) on enhancing the entrepreneurial skills, management and customer relation of the farmers that are projected to have a long-term positive effect on the success of farm tourist sites. These ventures are an ideal venue for information sharing on important data (e.g. market trends, market profile) that will capacitate farm tourism operators in understanding the market trends and tourist interests. Developing skills to novice players in farm tourism would potentially augment tourism performance in the country.

The strategy “research and development, and science and technology intervention to further develop farm sites and farm products” can be implemented by policymakers (i.e. the government) and the farm tourism sector (i.e. operators, NGOs). This strategy aims to address the insufficient number of farm tourism sites, poor consistency in the quality of farm tourism products and farmers' lack of entrepreneurial and marketing skills while accessing two opportunities: growing trend and tourist interest in farm tourism and increasing government support for farm tourism. With the emerging interests of tourists for farm tourism, an increase in tourist influx is expected, and farm operators could respond to such opportunity by establishing close coordination with the government and the academe to develop and implement R&D programs (e.g. research projects, seminar modules, training, workshops, benchmarking visits, among others) to advance the entrepreneurial and marketing skills of farmers. With universities spearheading the R & D programs, product research on enhancing farm tourism products could be implemented along with the farm tourism sector members. The financial and infrastructural requirements to support these activities could be bridged through increasing government spending for farm tourism to support the R.A. 10816. With R&D programs to improve farm tourism site accreditation and increased government support for such activity, there would be an expected increase in the number of farm tourism sites and strengthening public awareness for farm tourism.

Another strategy that the Philippine Government could initiate is to offer financial assistance to small farmers in diversifying their farms with tourism. Such a strategy takes advantage of increased government support for farm tourism and economic development dispersal direction to rural areas while curbing the insufficiency of the number of farm tourism sites and poor consistency in the quality of farm tourism products. Direct financial assistance could be possible in low-interest loans, tax incentives and tax holidays for farm tourism operators. Indirect aid could be in the form of free training and seminars on relevant topics such as technical skills as well as entrepreneurial and marketing skills for farm tourism. The government could also assist in the marketing and promotion of farm tourism sites and support for relevant infrastructure. The current trajectory of development in the Philippines is associated with dispersal to rural areas to decongest traffic and address overpopulation in highly urbanized cities. With financial support to small-scale farmers for farm tourism and the development direction toward rural communities, these farmers could capitalize on the propagation of farm tourism sites and enhance farm tourism products. Finally, creating and promoting farm tours to tourists and educational institutions could capture the opportunity of the growing trend and tourist interest in farm tourism and improved Philippine tourism performance while addressing the insufficiency of the number of farm tourism sites and poor consistency in quality of farm tourism products, and farmers lack entrepreneurial and marketing skills. With increased farm tours, potential farm operators could get attracted to invest in diversifying toward farm tourism, and those current farm operators would be obliged to improve the quality of their farm tourism products and to invest in human resource improvement in their soft skills (i.e. entrepreneurial and marketing skills).

5. Policy insights

This section outlines insights to stakeholders, including the government, farm tourism operators and other relevant tourism offices for policy formulation, resource management, strategic planning, among others. The promotion of urban agriculture through vertical and urban farming could address the issues related to the scarcity of agricultural lands. In 2013, there was a proposed Urban Agriculture bill in the Philippine Congress, which is supposed to institutionalize urban farming in highly urbanized areas to encourage the production, processing and marketing of food crops and livestock. The bill also advocates vertical farming, which involves indoor agriculture. However, it was not yet enacted up until the present. Vertical farming has been successful in Singapore, a small city-state, limiting its agricultural land ( Hui, 2011 ; Yusoff et al. , 2017 ).

To ensure the quality of delivering the farm tourism products and services, DOT accredits farm tourism sites that complied with the minimum standards set by the agency. However, the tourism products could be further enhanced through relevant actions on a macro level: (R&D projects are needed to spearhead farm tourism development, especially farm sites. Several Asian countries have already been very aggressive in their promotion and development of farm tourism, and contributions to economics, social, cultural and environmental have been evident. Tourism Infrastructure Enterprise Zone Authority (TIEZA), the Philippine national government agency under the DOT tasked for the development, promotion and supervision of tourism projects in the country, and the Office of the Undersecretary for Tourism Planning of the DOT must be proactive in initiating research projects that would provide cutting edge information on market trends related to tourism and farm tourism. They also need to spearhead the development of more farm sites to strengthen not just the tourism industry in providing alternative attractions but also the agriculture industry. Close coordination between DOT, local government units and other government offices is vital for the success of farm sites in a local area. This coordination can be implemented through information and resource sharing to facilitate the efficient delivery of services. On the other hand, existing farm sites must address the basic needs of the tourists as required in the accreditation guidelines for farm sites. As small family farms have limited access to resources to invest in farm tourism, the government must support these farms by initiating activities which include offering an agriculturally oriented educational experience suitable for different ages, providing basic services, such as parking, signage and guides, and ensuring safety and security in farm sites.

In generational marketing, the millennials and generation X currently have the highest purchasing power and potential to educate later generations on appreciating farm tourism. These two generations are more inclined in experiential activities of farm tourism which highlights tourist experience, can encourage and enhance the appreciation of these generations to get involved in farming. Consequently, it can address the declining number of enrollments in agriculture academic programs in the country ( Cinco, 2012 ). The current educational system of the country should further impart great appreciation and value to the agricultural industry ( Briones et al. , 2017 ). Farm schools can become more attractive once they become accessible, most notably in rural areas, and if farming is perceived as a good income source. Locals can be taught modern farming techniques, which can uplift their livelihood and sense of satisfaction and make farming a viable option instead of moving to the urban cities for employment ( Torrevillas, 2016 ). Moreover, agriculture needs investment in skills development and training to create a new breed of agriculturists. Many academic and tourism experts are now tapping on the potential of farm tourism to alleviate poverty and promote agriculture courses in schools and universities. For instance, some farm tourism graduates from the Central Bicol State University of Agriculture (CBSUA), a state university in the northern Philippines, are currently involved in research and development efforts and are contributing to the promotion of Laguna farm sites, such as the Costales Nature Farms. Dar (2017) argued that empowerment and capacity development to harness the potential of human capital, such as skills enhancement of farmers and developing relevant educational curriculum and innovative pedagogy for various interest groups, are two crucial directions for the government. The outcome should be a farmer possessing qualities such as efficient producer, team player, scientist/technologist, businessman or entrepreneur and environmentalist. A case in point is the Costales Nature Farms, which is a multi-awarded farm site that has grown from a small family farm advocating organic farming in 2005 to the first farm site in the Philippines accredited by the DOT. The farm is visited for leisure and relaxation or education. Furthermore, the Costales Nature Farms is an accredited private extension service provider of the national government agencies for agriculture and tourism (e.g. Agriculture Training Institute, DA, DAR, DOT). It provides workshops on sustainable organic farming and farm tourism. The farm has partnered with renowned hotels and restaurants and supermarkets, and it became one of the major producers of high-value organic vegetables and herbs in the country.

The government should start conducting infomercials or information commercials about the value of agriculture. For instance, the government must pass a measure that would mandate all broadcasting and online media to allocate a certain portion of time a day to broadcast public service announcements and infomercials regarding laws, social welfare, public safety, procedures and other matters of national interest that could be an effective medium to disseminate information about agriculture. Although the government is offering undergraduate and graduate scholarships, this has been less appealing to the intended public due to the negative perception of a career in agriculture. However, if enhanced information dissemination on the diverse opportunities an agriculture career can offer is proactively undertaken, then the negative perception of the public about agriculture as a low income and low skilled career venture may be eradicated ( Whitmell, 2012 ). Changing perceptions through marketing and packaging agriculture to make it more appealing to the young generation would become necessary to the government. It is not just an issue in the country but other countries as well. Possible directions could be undertaken to increase the interest of the youth towards agriculture. The first is to have a social media existence. For instance, a Facebook page that aims to inspire the youth to be involved in agriculture can be developed, serving as a social forum and building agricultural networks. It may include inspirational stories of farmers to empower the youth. Second is through blogs, which are discussion or informational websites that can serve as a platform for information dissemination. A training, capacity building and promotion program can be catalyzed by sharing thoughts about agriculture. The third is having good public relations. There should be a good farming public relation by projecting more inspiring stories, personal satisfaction and incentives that can be gained from farming. The government should create an agriculture personality, such as employing celebrity ambassadors that embody the ideals of the farmers and serves as a role model.

The government has put forward comprehensive assistance programs for the farmers, such as training, initiatives and financial support, to convince the farmers and their children to stay in agriculture. This is possibly done by projecting that farming is a profitable enterprise. A relevant and emerging concept is advocating social entrepreneurship that pursues innovative ideas with the potential to solve a community problem. One successful social entrepreneurship case in the Philippines is the Gawad Kalinga Enchanted Farms (GKEF). Social entrepreneurs in GKEF adopted the concept to develop more agricultural projects and help curb the declining number of farmers. This movement has already attracted people worldwide and should be considered as a good benchmark for farm tourism. Additionally, as millennials and generation X are highly technology-oriented, to obtain more traction from these generations, the farm tourism sector must embrace the emerging trend of technological innovation. Approaches may include the incorporation of virtual reality in farm sites, development and selling of online packages (e.g. klook), increased digital visibility, among others.

The shift from the traditional agricultural productivity focus to entrepreneurial and service orientation in farm tourism further complicates the agricultural business processes of the farmers. This complexity requires assistance from the government sector in terms of soft skills, among others. Most farmers are well-equipped with farming skills and possess innate hospitality, mainly credited to the Filipino culture; however, they lack marketing and entrepreneurial skills. To address this gap, the following insights could be considered. First, R&D activities on the market are crucial to the success of the farm sites. The DOT and the DA must carry out initiatives to make this information on market trends and innovations in agriculture available to compete with other ASEAN countries offering farm tourism. Second, an inter-agency government collaboration may conduct training for the local farmers in customer relations management to better off their interaction with the tourists and ensure their safety and high-quality experience. Finally, the DOT may encourage travel agents and tour operators to create stand-alone farm packages, conduct farm tours and promote farm visits. Further encouragement of farm visits to universities to gain firsthand experience and learn the value of agriculture is an appropriate direction forward.

Lastly, proper mechanisms of integrating initiatives at the national level and local government units must be implemented to increase coordination for farm tourism activities. With the onset of the R.A. 10816, it is deemed appropriate that the country has an excellent national policy involving agriculture and tourism. However, the effectiveness of such a national measure is highly dependent on its implementation. Short- and long-term plans and controls must be developed to ensure that the goals and objectives of the measure are satisfied and the intended benefits to the general public are achieved. The local government units must also consider creating some initiatives and strive for linkages in their locality. Through the government-academe-industry linkages, knowledge transfers and collective to and from the academe to the industry are flourished, and more significant results (e.g. livelihood in the countryside, increased per capita income of farmers, sustainability, among others) may become visible in the long-term.

6. Conclusions and future work

Farm tourism is considered one of the drivers of Philippine tourism's growth with R.A 10816 along with the DOT farm site accreditation standards to ensure quality farm sites in the country. Intergovernmental collaboration and coordination are mandated in the said policy in developing, promoting and strategizing farm tourism in the country. With the current government initiatives, an increasing number of farm sites and farm tourists is projected. The research literature on farm tourism has been prevalent in developed countries and is undoubtedly scarce in developing countries. There are hardly any fundamental works on farm tourism in the Philippine context, such as the works of McDaniels and Trousdale (1999) , Recio et al. (2014) , Tuzon et al. (2014) and Lago (2017). This limitation about literature may have instigated the gradual growth of farm tourism amidst the vast agricultural land in the country. As such, this study provides relevant data on the potential of the Philippines as a farm tourism destination and the challenges that inhibit the country from developing profitable farm sites. The challenges highlight the physical characteristics, product development, education and training, management and entrepreneurship, marketing and customer relations and government support. This information is vital in mapping strategies through WO analysis (mini-maxi) as a competitive strategy of the TOWS matrix that intends to address the weaknesses while targeting the opportunities that could potentially enhance farm tourism status in the country.

Philippine agriculture plays a significant role in the Philippine economy, yet its performance is deemed low compared to other neighboring ASEAN countries as to its production rate, import rate and export earnings. The low productivity of agriculture is credited to the challenges faced by the industry. These challenges include rural areas are now slowly urbanized due to these developments credited to the growing population and demand for industrialization; farming has become stagnant with depleting farm product output as younger generations have perceived agriculture as an unremunerative career option; the climatic conditions, as possible effects of climate change, are considered as threats to farmlands; and the farmers have limited government and non-government access and provision to needed resources (i.e. financial, technical and human resources) to diversify farms into farm sites. As such, farms can improve economic performance by diversifying farms and offering alternative farm tourism activities. These limitations can result in poor consistency and quality and innovativeness of the farm sites. Farmers also entail acquiring skills other than entrepreneurial (e.g. customer relations, marketing). With this, the Philippine Government initiated the development of farm tourism camps or farm schools in the country as a venue for farmers to gain new insights. For instance, the DA and DOT have encouraged the local government units to identify the farmers' needs and be addressed through seminars and training. However, the unavailability of the market information and inability to analyze this information, as well as the poor transport infrastructures in most rural areas, contribute to the poor farm tourism quality. With this, the support of the government is crucial in honing the farmers to the improvement of farm tourism. The R.A 10816 is an aggressive move towards developing and promoting farm tourism in the country; however, the policy has not been fully implemented down to the micro-level since it was enacted in 2016. In summary, the main contribution of this study is the identification of challenges of the farm tourism sector in the Philippines and the corresponding strategies and insights to address these challenges. The findings contribute to the future of farm tourism in bridging the negative social outlook on employment associated with agriculture, at least in the Philippines. The promotion, development and education of farm tourism to the present and future generations could generate a proactive outlook on farming as an economic and social driver in advancing tourism and agricultural performance. The insights of this work can address the limited literature of farm tourism in the Philippine context. This work could catalyze farm tourism development research and foster talents in developing farm tourism.

The study has an exploratory approach and the findings of the study must be interpreted with limitations. Despite the limitations of the study, it yields strategies and policy insights that are valuable in the early stage of farm tourism. The study is qualitative research in nature and has used secondary data. The findings of the study have focused on the Philippine context and may possess the same conditions as other farm tourism sites in developing countries. This work is limited in providing a historical narrative and collection of relevant literature specific to the Philippine setting. Hence, future works in farm tourism in the Philippine context are encouraged to improve further the quality of farm tourism offerings in the country and other relevant countries. Quantitative research can be undertaken for primary relevant data that can be obtained. Future works may include identifying the challenges, strategies and insights to farm sites utilizing primary data generated from a case study, focus group discussion, interviews and surveys. Thus work must be continuously undertaken in the context of evaluating farm capacity for tourism and determining the willingness of farmers to engage in it. Finally, a comparative study on the farm tourism sectors in the ASEAN may be undertaken to identify the hotspots, benchmarks and areas for possible improvements.

2014 Agriculture productivity rate in some countries of the ASEAN

2014 Agri-related export product (in US$ billion)

WO Analysis with recommending strategies

Ahmad , H. , Huda , M.M.I. , Julianto , Y.A. and Januar , M. ( 2018 ), “ The projection of the development of folks’ farm as the concept of agro-tourism as an effort to increase economic benefits of small-scale livestock business ”, UNEJ e-Proceeding , pp. 79 - 82 .

Alave , K.L. ( 2011 ), “ Philippines is running out of farmers. Inquirer ”, available at: http://business.inquirer.net/18611/philippines-is-running-out-of-farmers

Amelia , M. , Cornelia , P. and Diana , M. ( 2017 ), “ Study regarding the impact of farm tourism and agrotourism on rural area ”, Agricultural Management/Lucrari Stiintifice Seria I, Management Agricol , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 125 - 128 .

Amir , A.F. , Ghapar , A.A. , Jamal , S.A. and Ahmad , K.N. ( 2015 ), “ Sustainable tourism development: a study on community resilience for rural tourism in Malaysia ”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 168 , pp. 116 - 122 .

Asadpourian , Z. , Rahimian , M. and Gholamrezai , S. ( 2020 ), “ SWOT-AHP-TOWS analysis for sustainable ecotourism development in the best area in Lorestan province ”, Social Indicators Research , Vol. 152 No. 1 , pp. 289 - 315 .

ASEAN Economic Integration Brief ( 2019 ), “ Associations of Southeast Asian nations ”, available at: https://asean.org/asean-economic-community/aec-monitoring/asean-economic-integration-brief/

Barbieri , C. , Xu , S. , Gil-Arroyo , C. , Rich , S.R. ( 2016 ), “ Agritourism, farm visit, or…? a branding assessment for recreation on farms ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 55 No. 8 , pp. 1094 - 1108 .

Beus , C.E. ( 2008 ), Agritourism: Cultivating Tourists on the Farm , Washington, DC State University Extension .

Blekesaune , A. , Brandth , B. and Haugen , M.S. ( 2010 ), “ Visitors to farm tourism enterprises in Norway ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 54 - 73 .

Brandth , B. and Haugen , M.S. ( 2011 ), “ Farm diversification into tourism–implications for social identity? ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 44 .

Briones , Z.B.H. , Yusay , R.M.S. and Valdez , S. ( 2017 ), “ Enhancing community based tourism programs of Gawad Kalinga enchanted farm towards sustainable tourism development ”, Journal of Economic Development, Management, IT, Finance, and Marketing , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 60 .

Busby , G. and Rendle , S. ( 2000 ), “ The transition from tourism on farms to farm tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 21 No. 6 , pp. 635 - 642 .

Caballé , A. ( 1999 ), “ Farm tourism in Spain: a gender perspective ”, GeoJournal , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 245 - 252 .

Cabildo , J. Subingsubing , K. and Reysio-Cruz , M. ( 2017 ), “ March 1). many farms lost to land conversion. Inquirer ”, available at: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/876377/many-farms-lost-to-land-conversion

Casauay , A. ( 2014 ), “ PH farmers endangered species. Rappler ”, available at: www.rappler.com/business/special-report/world-economic-forum/2014/58607-ph-farmers-endangered-species-pangilinan

Cavaco , C. ( 1995 ), “ Rural tourism: the creation of new tourist spaces ”, in Armando , M. and Allan , W. (Eds), European Tourism: Regions, Spaces and Restructuring , John Wiley and Sons , Chichester and New York, NY , 127 - 149 .

Cinco , M. ( 2012 ), “ Farmlands are also for tourists. Inquirer.net ”, available at: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/223629/farmlands-are-also-for-tourists

Cloke , P. and Perkins , H.C. ( 2002 ), “ Commodification and adventure in New Zealand tourism ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 5 No. 6 , pp. 521 - 549 .

Cornelia , P. , Aurelian , C. , Ioan , P. , Iasmina , I. and Diana , M. ( 2017 ), “ Types of farm activities specific to educational rural tourism ”, Agricultural Management/Lucrari Stiintifice Seria I, Management Agricol , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 181 - 184 .

Da Liang , A.R. , Nie , Y.Y. , Chen , D.J. and Chen , P.J. ( 2020 ), “ Case studies on co-branding and farm tourism: best match between farm image and experience activities ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , Vol. 42 , pp. 107 - 118 .

Dandage , R.V. , Mantha , S.S. and Rane , S.B. ( 2019 ), “ Strategy development using TOWS matrix for international project risk management based on prioritization of risk categories ”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 12 No. 4 , pp. 1003 - 1029 .

Dar , W. ( 2017 ), “ The shift to inclusive agribusiness for prosperity ”, available at: www.manilatimes.net/shift-inclusive-agribusiness-prosperity-2/327959/

Davies , E.T. and Gilbert , D.C. ( 1992 ), “ A case study of the development of farm tourism in Wales ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 13 No. 1 , pp. 56 - 63 .

Dorobantu , M.R. and Nistoreanu , P. ( 2012 ), “ Rural tourism and ecotourism–the main priorities in sustainable development orientations of rural local communities in Romania ”, Economy Transdisciplinarity Cognition , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 259 - 266 .

Dubois , C. , Cawley , M. and Schmitz , S. ( 2017 ), “ The tourist on the farm: a ‘muddled’ image ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 59 , pp. 298 - 311 .

Dyson , R.G. ( 2004 ), “ Strategic development and SWOT analysis at the university of Warwick ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 152 No. 3 , pp. 631 - 640 .

Empowering smallholder farmer in markets (ESFIM) ( 2009 ), available at: www.esfim.org/esfim-philippines-documents/

Fisher , D. ( 2006 ), “ The potential for rural heritage tourism in the Clarence valley of Northern New South Wales ”, Australian Geographer , Vol. 37 No. 3 , pp. 411 - 424 .

Fleischer , A. and Tchetchik , A. ( 2005 ), “ Does rural tourism benefit from agriculture? ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 493 - 501 .

Forbord , M. , Schermer , M. and Grießmair , K. ( 2012 ), “ Stability and variety–products, organization and institutionalization in farm tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 895 - 909 .

Forleo , M.B. , Giaccio , V. , Giannelli , A. , Mastronardi , L. and Palmieri , N. ( 2017 ), “ Socio-economic drivers, land cover changes and the dynamics of rural settlements: mt. Matese area (Italy) ”, European Countryside , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 435 - 457 .

Gabor , M.T. ( 2016 ), “ Why farm tourism ”, available at: https://businessmirror.com.ph/why-farm-tourism/

Galolo , J.O. ( 2016 ), “ DA 7: Cebu agriculture output low for its demand. Sunstar Cebu ”, available at: www.sunstar.com.ph/cebu/business/2016/07/01/da-7-cebu-agriculture-output-low-its-demand-482849

Garcia-Ramon , M.D. , Canoves , G. and Valdovinos , N. ( 1995 ), “ Farm tourism, gender and the environment in Spain ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 267 - 282 .

Garrod , B. ( 2011 ), “ Diversification into farm tourism: Case studies from Wales ”, Case Study and Student Material. Contemporary Cases Online , Goodfellow Publishers Limited , Woodeaton, Oxford , Retrieved May 28, 2013 .

Ghatak , M. and Mookherjee , D. ( 2014 ), “ Land acquisition for industrialization and compensation of displaced farmers ”, Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 110 , pp. 303 - 312 .

Giaccio , V. , Giannelli , A. and Mastronardi , L. ( 2018 ), “ Explaining determinants of Agri-tourism income: evidence from Italy ”, Tourism Review , Vol. 73 No. 2 , pp. 216 - 229 .

Goranczewski , B. and Puciato , D. ( 2010 ), “ SWOT analysis in the formulation of tourism development strategies for destinations ”, Tourism , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 45 - 53 .

Grande , J. ( 2011 ), “ New venture creation in the farm sector–critical resources and capabilities ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 27 No. 2 , pp. 220 - 233 .

Haghiri , M. and Okech , R.N. ( 2011 ), “ The role of the agritourism management in developing the economy of rural regions ”, Book of Proceedings Vol. I-International Conference on Tourism and Management Studies , pp. 99 - 105 .

Haugen , M.S. and Vik , J. ( 2008 ), “ Farmers as entrepreneurs: the case of farm-based tourism ”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 321 - 336 .

Hjalager , A.-M. ( 1996 ), “ Agricultural diversification into tourism: evidence of a European community development programme ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 103 - 111 .