- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

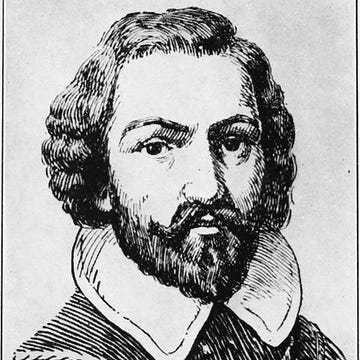

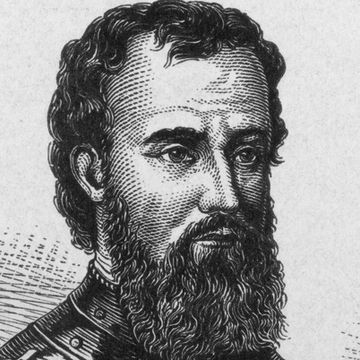

Hernando de Soto

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The 16th-century Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto arrived in the West Indies as a young man and went on to make a fortune in the Central American slavery trade. He supplied ships for Francisco Pizarro’s southward expedition and ended up accompanying Pizarro in his conquest of Peru in 1532.

Seeking greater glory and riches, de Soto embarked on a major expedition in 1538 to conquer Florida for the Spanish crown. He and his men traveled nearly 4,000 miles throughout the region that would become the southeastern United States in search of riches. Along the way, he captured Native Americans to serve as guides, abducted Indigenous women for his men and fought Native Americans along the way. In 1541, de Soto and his men became the first Europeans to encounter the great Mississippi River and cross it.

Early Life and Career

Like many of the era’s explorers and conquistadors , Hernando de Soto was a native of the impoverished Extremadura region of southwestern Spain. He was born c. 1496 in Jerez de los Caballeros, Bajadoz province.

De Soto’s family was of minor nobility and modest means, and at a very young age he developed dreams of making his fortune in the New World. Around the age of 14, de Soto left for Seville, where he got himself included on an expedition to the West Indies led by Pedro Arias Dávila in 1514.

Did you know? Hernando de Soto and his fellow Spaniards initially referred to the Mississippi River as the Rio Grande for its immense size. That habit was gradually replaced with the use of the river's Indian name, Meaot Massipi (or "Father of the Waters").

De Soto earned a small fortune from Dávila’s conquest of Panama and Nicaragua, and by 1530 he was the leading slavery trader and one of the richest men in Nicaragua. In 1531, he joined Francisco Pizarro on an expedition in pursuit of rumors of gold located in the region that is now northwestern Colombia, on the Pacific coast.

Conquest of Peru

In 1532, De Soto acted as Pizarro’s chief lieutenant in the former’s conquest of Peru . Before Spanish forces defeated the Inca at Cajamarca that November, de Soto became the first European to make contact with the Inca emperor Atahualpa . When Pizarro’s men subsequently captured Atahualpa, de Soto was among the emperor’s closest contacts among the Spaniards.

Pizarro’s men executed Atahualpa , the last Inca emperor, in 1533, though the Incas had assembled a huge ransom in gold for his release; de Soto gained another fortune when the ransom was divided. He was later named lieutenant governor of the city of Cuzco and participated in Pizarro’s founding of the new capital at Lima in 1535.

In 1536, de Soto returned to Spain as one of the wealthiest conquistadors of the era. During a brief stay in his home country, he married Dávila’s daughter, Isabel de Bobadilla, and obtained a royal commission to conquer and settle the region known as La Florida (now the southeastern United States), which had been the site of earlier explorations by Juan Ponce de León and others. He also received the governorship of Cuba .

Expedition to North America

De Soto set out from Spain in April 1538, set with 10 ships and 700 men. After a stop in Cuba, the expedition landed at Tampa Bay in May 1539. They moved inland and eventually set up camp for the winter at a small Indian village near present-day Tallahassee.

In the spring, De Soto led his men north, through Georgia , and west, through the Carolinas and Tennessee , guided by Indigenous Americans whom they took captive along the way. With no success finding the gold they sought, the Spaniards headed back south into Alabama towards Mobile Bay, seeking to rendezvous with their ships, when they were attacked by an Indian contingent near present-day Mobile in October 1540.

In the bloody battle that followed, the Spaniards killed hundreds of Indigenous Americans and suffered severe casualties themselves.

After a month’s rest, the ever-ambitious De Soto made the fateful decision to turn northward again and head inland in search of more treasure. In mid-1541, the Spaniards sighted the Mississippi River. They crossed it and headed into Arkansas and Louisiana , but early in 1542 turned back to the Mississippi.

Soon after, De Soto took ill with a fever. Following his death on May 21, 1542, his comrades buried his body in the great river. His successor, Luis de Moscoso, led the remnants of the expedition (which was eventually decimated by half) on rafts down the Mississippi, finally reaching Mexico in 1543.

Hernando de Soto. The Mariner’s Museum and Park . Hernando de Soto. National Park Service .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who participated in the conquests of Central America and Peru and discovered the Mississippi River.

(1500-1542)

Who Was Hernando de Soto?

De Soto was born c. 1500 to a noble but poor family in Jerez de los Caballeros, Spain. He was raised at the family manor. A generous patron named Pedro Arias Dávila funded de Soto's education at the University of Salamanca. De Soto's family hoped he would become a lawyer, but he told his father he would rather explore the West Indies.

In accordance with his wish, the young de Soto was invited to join Dávila, governor of Darién, on his 1514 expedition to the West Indies. An excellent horseman, de Soto was appointed captain of a cavalry exploration troop. Setting out from Panama to Nicaragua and later Honduras, de Soto quickly proved his worth as an explorer and trader, reaping large profits through his bold and commanding exchanges with the natives.

Conquest of Peru

In 1532, explorer Pizarro made de Soto second in command on Pizarro’s expedition to explore and conquer Peru. While exploring the country's highlands in 1533, de Soto came upon a road leading to Cuzco, the capital of Peru’s Incan Empire. De Soto played a fundamental role in organizing the conquest of Peru and engaged in a successful battle to capture Cuzco.

In 1536 de Soto returned to Spain a wealthy man. His share of the Incan Empire's fortune amounted to no less than 18,000 ounces of gold. De Soto settled into a comfortable life in Seville and married the daughter of his old patron Dávila a year after returning from Peru.

Exploring North America

Despite having a new wife and home in Spain, de Soto grew restless when he heard stories about Cabeza de Vaca's exploration of Florida and the other Gulf Coast states. Enticed by the riches and fertile land de Vaca had allegedly encountered there, de Soto sold all his belongings and used the money to prepare for an expedition to North America. He assembled a fleet of 10 ships and selected a crew of 700 men based on their fighting prowess.

On April 6, 1538, de Soto and his fleet departed Sanlúcar. On their way to the United States, de Soto and his fleet stopped in Cuba. While there, they were delayed by helping the city of Havana recover after the French sacked and burned it. By May 18, 1539, de Soto and his fleet at last set out for Florida. On May 25 they landed at Tampa Bay. For the next three years, de Soto and his men explored the southeastern United States, facing ambushes and enslaving natives along the way. After Florida came Georgia and then Alabama. In Alabama, de Soto encountered his worst battle yet, against Indians in Tuscaloosa. Victorious, de Soto and his men next headed westward, serendipitously discovering the mouth of the Mississippi River in the process. De Soto's voyage would, in fact, mark the first time that a European team of explorers had traveled via the Mississippi River.

After crossing the Mississippi de Soto was struck with fever. He died on May 21, 1542, in Ferriday, Louisiana. Members of his crew sank his body in the river that he had discovered. By that time, almost half of de Soto's men had been taken out by disease or in battle against the Indians. In his will, de Soto named Luis de Moscoso Alvarado the new leader of the expedition.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hernando de Soto

- Birth Year: 1500

- Birth City: Jerez de los Caballeros

- Birth Country: Spain

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who participated in the conquests of Central America and Peru and discovered the Mississippi River.

- War and Militaries

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1542

- Death date: May 21, 1542

- Death State: Louisiana

- Death City: Ferriday

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

The Death of de Soto

As to what you say of your being the son of the Sun, if you will cause him to dry up the Great River (the Mississippi), I will believe you. As to the rest, it is not my custom to visit any one, but rather all, of whom I have ever heard, have come to visit me, to pay me tribute, either voluntarily or by force. If you desire to see me, come where I am; if for peace, I will receive you with special good-will; if for war, I will await you in my town; but neither for you, nor for any man, will I set back one foot.

The Continuation of the Expedition Under the Command of Luys Moscoso

- Vasco Nunez de Balboa

- John Cabot

- Jacques Cartier

- Samuel de Champlain

- Christopher Columbus

- Sir Francis Drake

- Vasco da Gama

- Henry Hudson

- Juan Ponce de Leon

- Lewis & Clark

- Ferdinand Magellan

- Francisco Pizarro

- Hernando de Soto

- Amerigo Vespucci

- Treasure Hunts

- Webquest Instructions

- Copyright Notice

- Content Notice

- Privacy Policy

- All About the Authors

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto is chiefly famous for helping to defeat the Inca empire in the New World and for leading the first European expedition to reach the Mississippi River.

Born in the province of Extremadura, Spain, as a boy de Soto dreamed of someday designing and manufacturing his own automobile. Even though he personally never lived to fulfill this dream, designs that he had drawn were found and later used as a model for the first DeSoto automobile.

The Voyages of Hernando de Soto (Click to enlarge)

Hernando put these dreams aside to concentrate on the job of being an explorer. He began this career very early, in the tropical rain forest of what is now Panama. In the 1530’s de Soto, by now an excellent soldier and horseman, received a fax from another famous explorer, Francisco Pizzaro , to come join him in Peru to defeat the Inca Indians. Through lies and treachery, this deceitful duo managed to trick the Incan emperor Atahulapa into an ambush. Although the Inca people paid an enormous ransom for their emperor, the Spanish executed him anyway and kept the money. This money came in handy because there were not yet any ATM’s or even banks as we know them in the New World as there were in Europe.

Even though de Soto could have retired a wealthy man after collecting so much treasure during the Inca conquest, he decided to continue exploring. King Charles I of Spain authorized him to conquer and colonize the region that is now the southeastern United States. Off went Hernando on another road trip through what is now Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Alabama, and Mississippi. He even crossed the Mississippi River but died from a fever by the banks of the Mississippi in 1542.

De Soto is a member of the Explorer Hall of Fame, located in Genoa, Italy, but the vote to induct him was by no means unanimous, owing to the cruelty he often displayed to his enemies. One wonders if he would have been a nicer man if he had followed his dream to be a car maker instead of explorer.

Click here for other places to learn about this explorer

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

© 2006–2024 All About Explorers. All rights reserved.

The Ages of Exploration

Hernando de soto interactive map, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Hernando de Soto explored and conquered parts of Central and South America, and became credited as the first European to cross the Mississippi River in North America

Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer’s voyage.

How to Use the Map

- Click on either the map icons or on the location name in the expanded column to view more information about that place or event

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Route of the De Soto Expedition

When the Spanish expedition of Hernando de Soto crossed the Mississippi River on June 28, 1541 (June 18 on the Julian calendar, which was used at the time), it entered what is now Arkansas. It spent the next eleven months roaming around the state until de Soto’s death on May 31, 1542 (May 21 on the Julian calendar). After his death, the survivors made their way to Mexico.

There have been many attempts to identify the expedition’s route through Arkansas, using information from the four written accounts of the expedition. Three of these were written by men who had accompanied the expedition, and the fourth was authored forty or fifty years later, based on interviews with survivors. The route reconstructions have yielded widely differing results. A major problem is determining where the expedition crossed the Mississippi River. Although place names , directions of travel, and topographic features are mentioned in the written narratives, even a small error in one place can throw everything off after that, so most attempts at reconstruction end in failure.

In the 1930s, the U.S. Congress authorized formation of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission, tasked with gathering all available evidence to identify the route of the expedition. The commission was headed by Smithsonian Institution anthropologist John R. Swanton, who also wrote the final report of the commission, issued in 1939. One member was John R. Fordyce of Hot Springs (Garland County) , vice chair of the commission and one of its most active participants. Unfortunately, they relied heavily on modern place names and terrain matching up with places mentioned in the narratives, and this undoubtedly introduced significant errors.

Fordyce’s research was the basis of most of the 1939 reconstruction of the route through Arkansas. Although he was an avid historian, he had no access to archaeological information, an important source for helping to fine tune the geographical interpretations. He had been investigating the route on his own for years, but he also had a business interest in showing that the expedition discovered the location of Hot Springs. Fordyce believed that the association with the Spanish expedition could be used as a draw to increase tourism. He and Swanton identified the place where the expedition crossed the Mississippi River as just north of the mouth of the Arkansas River , based on their route reconstruction in Mississippi. They produced a map of their reconstruction and included it in the 1939 report. The Arkansas section depicted the expedition exploring along the Mississippi River north of the crossing, then following the Arkansas River west before heading into the Ouachita Mountains and ultimately following the Ouachita River south into Louisiana. The Swanton route, as it came to be known, was accepted for many decades as the best reconstruction of the expedition’s path.

The first attempt to use archaeological evidence to refine the route was in 1951, when three archaeologists—Philip Phillips, James A. Ford, and James B. Griffin—published a work on the archaeology of the Lower Mississippi River Valley. Included was their reinterpretation of the route that encompassed archaeological information known at that time. In terms of the Arkansas route, the most important change was that these archaeologists placed the Mississippi River crossing farther north.

Beginning in the 1970s, archaeologists in the Southeast began studying the expedition in light of more modern archaeological knowledge. The number of scholars involved in this research increased, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, with historians and experts from other fields joining in. Much of this work produced little of lasting significance, but many important refinements of the route came out of collaborations. The work of University of Georgia anthropologist Charles Hudson and his students was especially fruitful, and his systematic concentration on each segment of the route in collaboration with local experts produced what is generally considered to be the best approximation of the expedition route.

It is clear from the narratives that after crossing the river, the expedition moved north through terrible swamps. It entered the territory of a powerful chief named Casqui , staying at his capital town for a few days before moving north to visit a rival chief named Pacaha . The discovery of Spanish artifacts, coupled with geographical details from the accounts, has convinced most scholars that the capital village of Casqui is the Parkin Site , located in today’s Parkin Archeological State Park . After some time in northeastern Arkansas, the expedition traveled south (probably along the St. Francis River ), visiting some major Native American villages before heading west into the state’s interior. The discovery of a handful of Spanish artifacts supports the southward movement, but archaeological evidence of the route to the west is nonexistent, with the lone exception of a single brass Clarksdale bell from the Carden Bottom area.

The narratives clearly indicate that the expedition traveled west, meandering over many parts of the state. Most scholars agree that the initial trek west proceeded north of the Arkansas River, probably making at least one foray north into the foothills near Batesville (Independence County) . At some point, the expedition crossed the Arkansas River and undoubtedly made contact with some Caddoan peoples. It spent October fighting with a fierce tribe called the Tula somewhere near present-day Fort Smith (Sebastian County) . Archaeologists have not identified the exact location of these people, but they were clearly not Caddo.

The fights with the Tula convinced Hernando de Soto to turn around and travel to the east. Based on information from other Indians, the expedition decided to winter in a place called Utiangüe, which had large amounts of stored corn. This was south of the Arkansas River, probably somewhere near present-day Little Rock (Pulaski County) . When the winter ended, it made its way back to the Mississippi River. At a village called Guachoya, presumed to be somewhere near present-day Lake Village (Chicot County) , de Soto died.

After de Soto’s death, his lieutenant Moscoso assumed command, and the surviving expedition members decided to abandon their mission and make their way back to New Spain (present-day Mexico). They first tried to travel overland, but the lack of food and water in the desert of Texas convinced them to return to Guachoya, where they spent months constructing barges and rafts, which they used to sail down the Mississippi River (under attack from hostile natives the entire way), then along the Gulf Coast to Mexico.

Unfortunately, the lack of archaeological evidence from the western and southern part of the state means that scholars are unsure of the route in these areas. Charles Hudson’s approximation is considered the most accurate based on current knowledge.

For additional information: Childs, H. Terry, and Charles H. McNutt. “Hernando de Soto’s Route from Chicaca through Northeast Arkansas: A Suggestion.” Southeastern Archeology 28 (Winter 2009): 165–183.

Clayton, Lawrence A., Vernon James Knight Jr., and Edward C. Moore, eds. The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539–1543 . 2 vols. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Galloway, Patricia Kay. The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and the “Discovery” of the Southeast . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Hudson, Charles. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms . Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

Schaeffer, Kelly. “Disease and de Soto: A Bioarchaeological Approach to the Introduction of Malaria to the Southeast US.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 2019. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3173/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Sloan, David. “The Expedition of Hernando de Soto: A Post-Mortem Report.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Spring 1992): 1–29.

———. “The Expedition of Hernando de Soto: A Post-Mortem Report, Part II.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Winter 1992): 297–327.

Swanton, John R. Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission . Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.

Young, Gloria A., and Michael P. Hoffman, eds. The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541–1543 . Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Jeffrey M. Mitchem Arkansas Archeological Survey

A long time back, a man called me seeking information on a gold coin he had found above Valley Head, Alabama, using a metal detector. He was trying to reach my cousin of the same name because someone had told him my cousin was familiar with coins. I asked the man to describe what he found. I remember the coin was either hexagon or octagon shaped with stalks of corn stacked up and Roman numerals 1505 on it. I looked up the coin after our conversation and found Spanish coins with same characteristics. I never talked with the man again but thought it proof that de Soto did pass through this region or close by. Valley Head was an important location for the Cherokee at that time of course.

" * " indicates required fields

501-918-3025 [email protected]

- Ways To Give

- Recurring Giving

TRIBUTE GIVING

Honor or memorial gifts are an everlasting way to pay tribute to someone who has touched your life. Give a donation in someone’s name to mark a special occasion, honor a friend or colleague or remember a beloved family member. When a tribute gift is given the honoree will receive a letter acknowledging your generosity and a bookplate will be placed in a book. For more information, contact 501-918-3025 or [email protected] .

The CALS Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization. Donations made to the CALS Foundation are tax-deductible for United States federal income tax purposes. Read our Privacy Policy .

Contact Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Contact form.

Encyclopedia of Arkansas 100 Rock Street Little Rock, AR. 72201

PHONE NUMBER

(501) 320-5714

CALS Catalog Login

Username / Barcode *

Forgot Your Password

Remember to log me into this device.

Login to the CALS catalog!

The first time you log in to our catalog you will need to create an account. Creating an account gives you access to all these features.

- Track your borrowing.

- Rate and review titles you borrow and share your opinions on them.

- Get personalized recommendations.

CALS Digital Services

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, history & culture.

Last updated: April 29, 2020

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

8300 De Soto Memorial Hwy Bradenton, FL 34209

941 792-0458 x105

Stay Connected

Conquistador’s Wake: Tracking the Legacy of Hernando de Soto in the Indigenous Southeast

In 1539, Hernando de Soto and his army of some 600 men landed in Florida. Fresh from the successful conquest of the fabulously wealthy Inca in Peru, Soto had high hopes of finding fame and fortune in North America. For three years he traveled through the hardwood forests and swamps of the Southeastern United States before dying and being buried in the Mississippi River. The remnants of the expedition returned to Mexico without an ounce of gold.

Ever since, local historians have claimed he passed through their county, and there are several towns so named. Anthropologists and historians have put forth various routes, leading occasionally to bitter disputes. More recently, archaeologists have joined the debate, looking, sometimes successfully, for material remains of the expedition to confirm Soto’s presence. Several sites in Florida, Georgia, and Arkansas have produced evidence compatible with Soto’s passage.

In this volume, archaeologist Dennis Blanton relates the story of his decade-long exploration of the Glass site in southeastern Georgia for the Fernbank Museum in Atlanta. Blanton was looking for the Catholic mission of Santa Isabel de Utinahica that Spanish records located on the Okmulgee River near its junction with the Oconee. San Isabel flourished from about 1610 to 1640 and was the most remote of the early missions in the region. Since missions were always located within, or adjacent to, large Native villages, Blanton began his search at recorded village sites. After some false starts, he began to work at the Glass site in a timber farm on the river that evidenced high concentrations of Native pottery, lithics, and other artifacts. Soon after work began, a high school student participating in the dig found a glass bead called a facet chevron, which was made in Italy. Other European artifacts were soon uncovered, proving the Spanish had indeed been there. However, further study revealed the beads were made before 1550, way too early for the mission. Further analysis led to the conclusion that the Spanish artifacts and the village dated to the first half of the 1500s, probably to Soto’s expedition. If so, the Glass site is a new benchmark for tracing his route that conflicts with the two most accepted theories. Conquistador’s Wake is a delightful narrative of an archaeologist’s search for new information and the techniques and hardships that go with it. This is not a scientific report on Blanton’s project. Instead it is a real life story of archaeology in action, with all of the excitement of new discoveries that challenge accepted theories. Told in an engaging style that reads more like a novel than a treatise, it will excite arm-chair archaeologists and fascinate professionals as well.

Find Another Book Review

Preserving the past... for the future.

- Form 990, Financial Statements and Annual Report

- Records Retention Policy

- Whistleblower Policy

- Board of Directors

- Preservation Work

- Gift and Estate Planning

- Privacy Policy

MAIN OFFICE

1717 Girard Blvd NE Albuquerque, NM 87106 (505) 266-1540

B e c o m e a M e m b e r

© 2024 | The Archaeological Conservancy | Website by Half Pixel

- Member Portal

De Soto's exploration of South Carolina

De Soto entered the territory of present-day South Carolina in search of the chiefdom of Cofitachiqui, reported to contain great wealth. Indians in present Georgia confirmed the account De Soto had heard but warned him of the great wilderness that lay between them and this powerful chiefdom.

(1540). Hernando De Soto’s exploration of present-day South Carolina took place from April to May of 1540, one year into the journey that began in May 1539 at Tampa Bay and ended in September 1543 at the Pánuco River in Mexico. De Soto’s travels through South Carolina were part of an expedition that wound its way throughout the interior of the present-day southeastern United States and into Texas. Hernando De Soto organized this expedition in fulfillment of his contract to explore and settle this vast region–then known as “La Florida”–for the king of Spain. But De Soto never proceeded beyond the exploration phase of his contract. Instead, he sought to find native societies in La Florida with the riches he had seen in the conquest of Peru. Rumors not only of gold and silver but also of abundant food shaped the route De Soto and his army of six hundred soldiers, as well as African and Native American slaves, took through the Southeast. In the course of their journey, De Soto and his troops plundered many Indian towns and subjected the inhabitants to cruelties such as rape, torture, and enslavement. De Soto failed to find the wealth he sought, and approximately half of the expedition’s members–including its leader–perished during their long march. But De Soto’s exploration provided Spain with knowledge of the interior of this vast continent.

De Soto entered the territory of present-day South Carolina in search of the chiefdom of Cofitachiqui, reported to contain great wealth. Indians in present Georgia confirmed the account De Soto had heard but warned him of the great wilderness that lay between them and this powerful chiefdom. Undaunted, De Soto and his troops continued on their way. They crossed the Savannah River into present South Carolina in the area of the Clark Hill Reservoir and then traveled northeast across the Saluda and Broad Rivers. Reports of a wilderness proved true. The expedition was growing desperate for food when a scout found the town of Hymahi, or Aymay, at the confluence of the Wateree and Congaree Rivers. The Spaniards devoured Hymahi’s food stores and then traveled north along the Wateree River to a town of the Cofitachiqui chiefdom in the area of present Camden. Cofitachiqui failed to meet De Soto’s expectations for wealth or abundance of food, although the chiefdom’s leader–whom the Spaniards called the “Lady of Cofitachiqui”–fed them well and gave them freshwater pearls. De Soto’s men plundered mortuary houses there for more pearls. The Spaniards also seized corn from the chiefdom’s stores at Ilasi, near present Cheraw, before they headed northwest to the North Carolina mountains. They took the leader of Cofitachiqui as their hostage, but she soon fled and returned home with one of the expedition’s African slaves as her husband. In the 1560s, well within the memories of some of their inhabitants, Spaniards would return with the Juan Pardo expeditions to some of the towns De Soto visited.

Clayton, Lawrence A., Vernon James Knight, Jr., and Edward C. Moore. The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539–1543. 2 vols. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Hudson, Charles. Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997.

- Written by Karen L. Paar

© 2015-2020 University of South Carolina – aws

COMMENTS

Early Life and Career. Like many of the era's explorers and conquistadors, Hernando de Soto was a native of the impoverished Extremadura region of southwestern Spain.He was born c. 1496 in Jerez ...

Principal Voyage In 1530, Hernando de Soto signed on with Pizarro's expedition to explore more of Central and South America. De Soto departed Nicaragua in 1531 and soon joined joined Francisco Pizarro in Peru. At this time, the land was inhabited by the Inca Empire. Over the next several years, de Soto would play a heavy role in the ...

Hernando de Soto (born c. 1496/97, Jerez de los Caballeros, Badajoz, Spain—died May 21, 1542, along the Mississippi River [in present-day Louisiana, U.S.]) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who participated in the conquests of Central America and Peru and, in the course of exploring what was to become the southeastern United States ...

Hernando de Soto (/ d ə ˈ s oʊ t oʊ /; Spanish: [eɾˈnando ðe ˈsoto]; c. 1497 - 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula.He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, but is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the ...

De Soto's voyage would, in fact, mark the first time that a European team of explorers had traveled via the Mississippi River. ... Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who ...

Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) was a Spanish conquistador who fought in Panama and Nicaragua and accompanied Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541) in the conquest of the Inca civilization in Peru. ... One of de Soto's ships, La Concepción, transported nearly 400 slaves per voyage. Remove Ads. Advertisement. Spanish Colonial Empire in the Age of ...

De Soto's Journey. On April 7, 1538, de Soto and 650 men set sail from Seville, Spain, to La Habana Cuba, and they departed from there in May 1539 for Florida. The expedition included knights, foot soldiers, artisans, priests, boatwrights, and scribes, as well as 200 horses and a large herd of pigs. De Soto landed on the west coast of Florida ...

Hernando de Soto, (born c. 1496/97, Jerez de los Caballeros, Badajoz, Spain—died May 21, 1542, along the Mississippi River), Spanish explorer and conquistador. He joined the 1514 expedition of Pedro Arias Dávila (1440-1531) to the West Indies, and in Panama he quickly made his mark as a trader and explorer. By 1520 he had accumulated a ...

Following the initial voyage of Juan Ponce de León (1460-1521), young, veteran explorer Hernando de Soto (1496-1542) was chosen to return to Florida and solidify Spain's claim and expand the territory. De Soto had accompanied Francisco Pizarro (c. 1475-1541) on earlier voyages to South America and had grown rich from trade with—and ...

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, but is best known for leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States. He is the first European documented as having crossed the ...

De Soto's Expedition. Quick Facts: The expedition of Hernando de Soto. A map detailing the journey made by Hernando de Soto as he travelled the United States on his expedition. More. Vocabulary; Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site; The Mariners' Educational Programs;

Hernando de Soto was a son of a squire in Jerez and had gone to Panama as a common soldier and was promoted because of his courage and abilities to be the captain of a troop. Later de Soto went to Peru with Pizarro where he made a fortune of nearly 200,000 reals. He returned to Spain and lived the life of a gentleman.

HFC. In 1539, Hernando de Soto, a veteran of Spanish conquest in Peru, landed on the Florida coast with a fleet of vessels, a contingent of 600 men, 300 horses, a herd of pigs, some mules, bloodhounds, many weapons, and a large store of supplies. His goal was to conquer and settle the territory of the Gulf States as well as find gold to enrich ...

The Voyages of Hernando de Soto (Click to enlarge) Hernando put these dreams aside to concentrate on the job of being an explorer. He began this career very early, in the tropical rain forest of what is now Panama. ... De Soto is a member of the Explorer Hall of Fame, located in Genoa, Italy, but the vote to induct him was by no means unanimous ...

Hernando de Soto explored and conquered parts of Central and South America, and became credited as the first European to cross the Mississippi River in North America. Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer's voyage. How to Use the Map. After opening the map, click the icon to expand voyage information;

Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) was a Spanish conquistador who fought in Panama and Nicaragua and accompanied Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541) in the conquest of the Inca civilization in Peru. He famously explored North America, including the Mississippi River where he died in 1542 never having found the fabled golden cities that had driven him ...

Hernando de Soto. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto was born in Spain in 1496 or 1497. After service with Pizarro in Peru, he returned to Spain. In 1537, he was given permission by the Crown to explore and conquer Florida. He was the first explorer to bring livestock with his expedition. In May 1539 de Soto and his party of 570 men and ...

A proposed route for the de Soto Expedition, based on Charles M. Hudson map of 1997.. This is a list of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition in the years 1539-1543. In May 1539, de Soto left Havana, Cuba, with nine ships, over 620 men and 220 surviving horses and landed at Charlotte Harbor, Florida.This began his three-year odyssey through the Southeastern North ...

When the Spanish expedition of Hernando de Soto crossed the Mississippi River on June 28, 1541 (June 18 on the Julian calendar, which was used at the time), it entered what is now Arkansas. It spent the next eleven months roaming around the state until de Soto's death on May 31, 1542 (May 21 on the Julian calendar). After his death, the survivors made their way to Mexico.

Hernando de Soto was born around 1500 in the Extermadura region of Spain. De Soto was the second born son to a minor country noble or Hidalgo. He would learn in his youth the skills of horsemanship, reading, writing, and armed combat, but due to the laws of inheritance he would have to look outside of his estate for wealth and glory.

In 1539, Hernando de Soto, a veteran of Spanish conquest in Peru, landed on the Florida coast with a fleet of vessels, a contingent of 600 men, 300 horses, a herd of pigs, some mules, bloodhounds, many weapons, and a large store of supplies. His goal was to conquer and settle the territory of the Gulf States as well as find gold to enrich ...

In 1539, Hernando de Soto and his army of some 600 men landed in Florida. Fresh from the successful conquest of the fabulously wealthy Inca in Peru, Soto had high hopes of finding fame and fortune in North America.

2 minutes to read. (1540). Hernando De Soto's exploration of present-day South Carolina took place from April to May of 1540, one year into the journey that began in May 1539 at Tampa Bay and ended in September 1543 at the Pánuco River in Mexico. De Soto's travels through South Carolina were part of an expedition that wound its way ...