ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

The cumberland road.

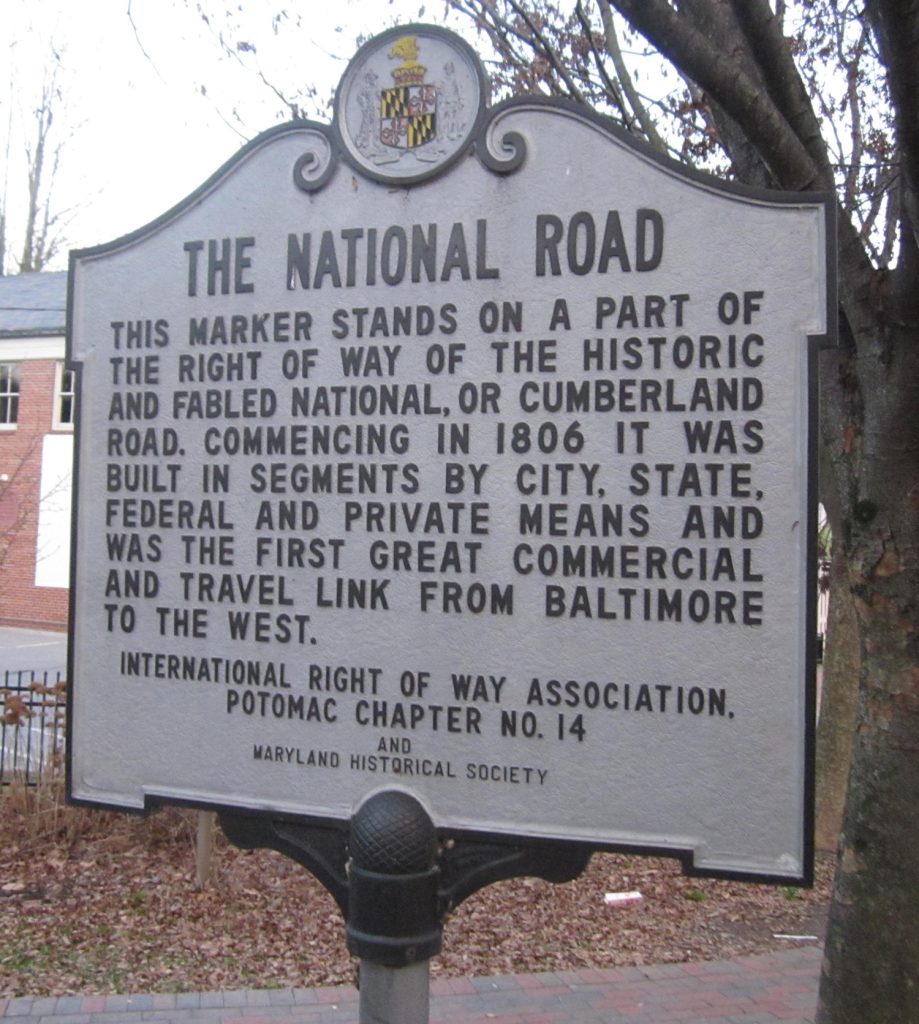

The Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road or National Turnpike, was the first road in U.S. history funded by the federal government. It promoted westward expansion, encouraged commerce between the Atlantic colonies and the West, and paved the way for an interstate highway system.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History

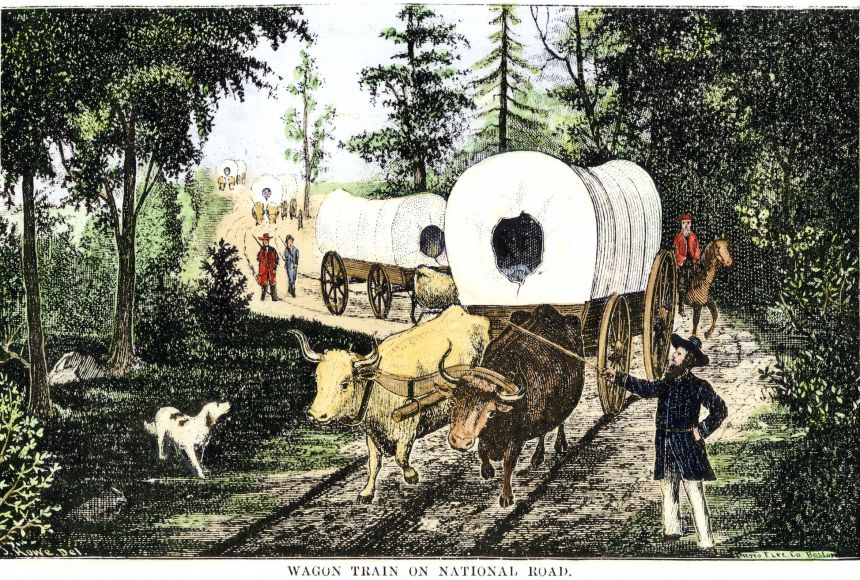

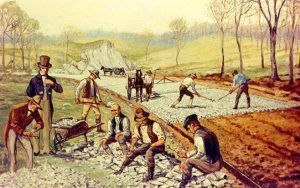

Cumberland Road Wagons

Stretching from Cumberland, Maryland, to St. Louis, Missouri, the Cumberland Road was the first road funded by the U.S. federal government. It was a popular route for commercial trade in the 1840s by Conestoga wagons.

Image from the North Wind Picture Archives

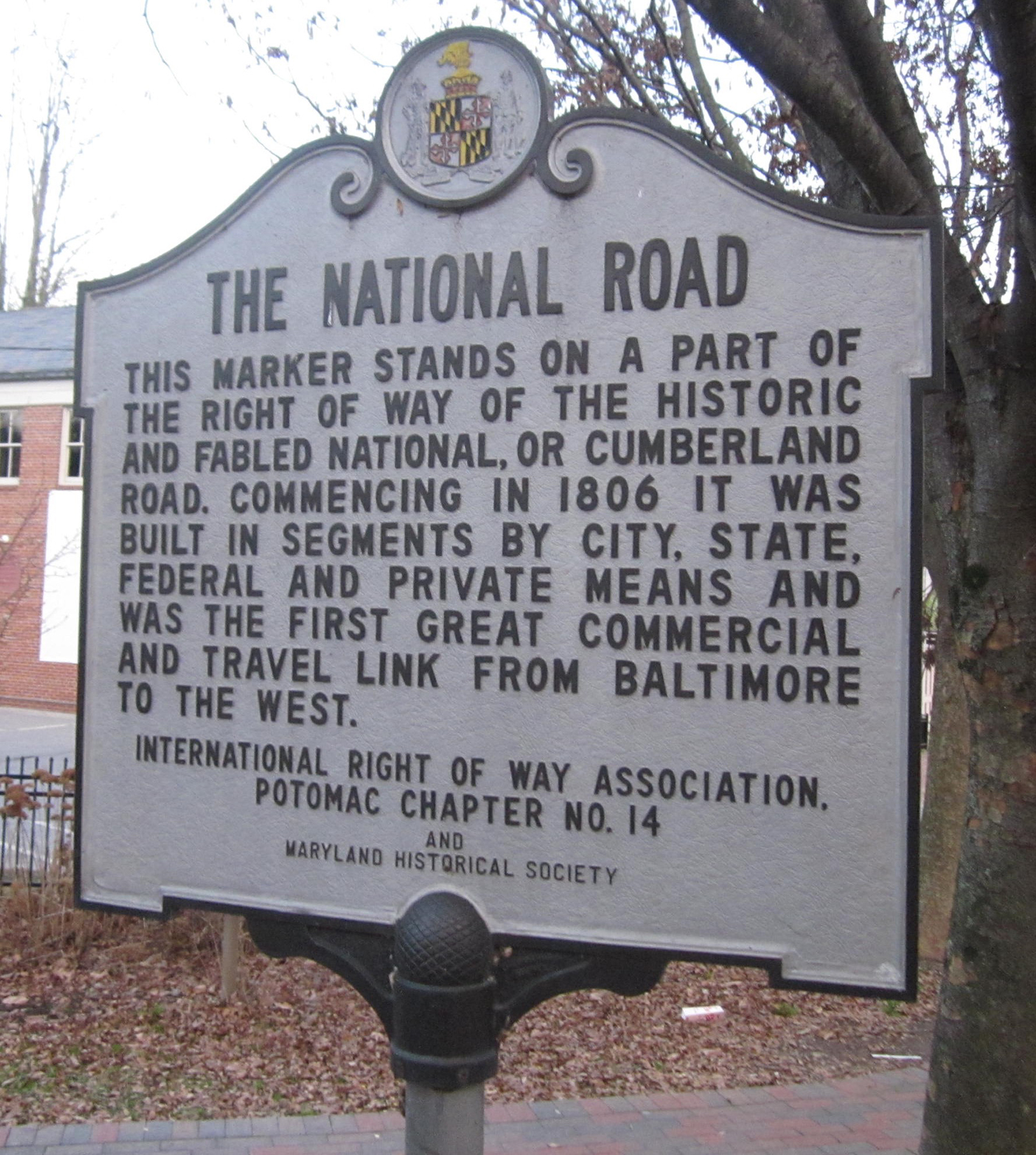

The Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road or National Turnpike , was the first road in the history of the United States funded by the federal government. President Thomas Jefferson promoted the road to support westward expansion and unify the developing nation, and Congress authorized its construction in 1806. By the middle of the century, the United States' first national highway ran from Cumberland, Maryland, to St. Louis, Missouri. It fulfilled Jefferson’s promise to unify the country: It promoted commerce and encouraged travel between the Atlantic colonies and the West. It also laid the foundation for the U.S. federal highway system. The construction of a federal road sparked controversy at the time Congress approved it, however. Many statesmen could not justify the expense, given the fact that, by this time, canals and rivers had proven to be efficient for transport. More significantly, however, people questioned the idea that the federal government should fund a roadway. They questioned whether the Constitution allowed for it. Today, federal highways form the backbone of the country’s infrastructure . In the early 1800s, however, most passageways were funded by the states that housed them and that benefited from their construction. The Erie Canal was an early exception; it was funded by the state of New York despite the fact that it benefited other states. Nevertheless, in 1811, construction of the Cumberland Road began, running through Maryland and West Virginia. The road was built in sections over a series of decades, and became something of a bustling highway . It spawned the development of towns, villages, and roadside establishments. It also provided a model for urban planning and commercial development as roadways became an integral part of the U.S. landscape. The fits and starts that characterized the nation’s first federal road continued throughout its existence, and its popularity at different times reflected the social environment of the country. The popularity of the National Road soared in the 1840s when it became a popular route for Conestoga wagons that encouraged a thriving commercial trade. In the 1870s, with the rise in railroads, the National Road lost its appeal, but by the 1920s it had made a comeback. The development of the automobile revived interest in the road, and federal funds increased to support the growth of the federal roadway system. The interstate highway system grew. The Cumberland Road, once dubbed “the Main Street of America,” became known as “the road that built a nation.” To support the need for improved roads, in 1926, the Cumberland Road was incorporated into Interstate 40, which runs coast to coast.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

September 13, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Significance of the Cumberland Road in the 19th Century: A Key Transportation Route That Shaped America

Welcome to my blog, 19th Century ! In this article, we will explore the significant role of the Cumberland Road during the 19th century . Discover how this remarkable transportation project shaped America’s growth and connected distant regions, forever impacting the nation’s economic development and expansion.

Table of Contents

The Significance of Cumberland Road in 19th Century America

The Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road, was a vital transportation route in 19th century America. It played a significant role in shaping the development of the nation and had profound impacts on various aspects of American society.

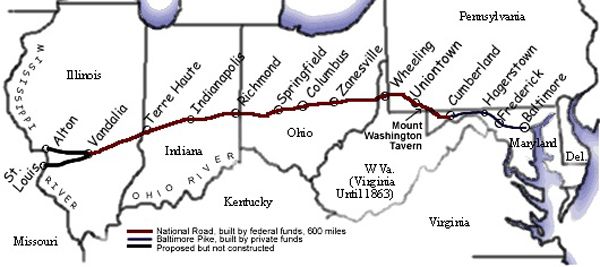

The construction of the Cumberland Road began in 1811 and it extended from Cumberland, Maryland to Vandalia, Illinois. It was the first major highway built by the federal government and served as a key link between the eastern and western parts of the country. By improving transportation and communication, the road fostered economic growth and regional integration.

The Cumberland Road facilitated trade and commerce, allowing goods and services to be transported more efficiently and at a faster pace. This not only boosted local economies along the route but also contributed to the overall expansion of American industries and markets. Additionally, the road facilitated the movement of people and encouraged westward migration, contributing to the settlement of new territories and the westward expansion of the United States.

Furthermore, the Cumberland Road played a crucial role in fostering a sense of national unity and identity during this period of rapid expansion and territorial acquisition. It served as a physical symbol of a growing nation and highlighted the government’s commitment to the development and progress of the country. The road connected states and regions, enabling people from different parts of the country to interact and exchange ideas, goods, and cultural influences.

Moreover, the construction of the Cumberland Road led to advancements in engineering and technology. It paved the way for future infrastructure projects and served as a model for subsequent road-building initiatives across the country. As a result, the road served as a catalyst for the development of an extensive network of roads, canals, and railroads in the following decades, which further enhanced connectivity and industrialization.

The Cumberland Road was a crucial transportation route in 19th century America. Its significance lies in its role in facilitating economic growth, promoting westward expansion, fostering national unity, and paving the way for future infrastructure projects. This iconic road played a pivotal part in shaping the development and progress of the United States during this transformative era.

Only Fans Girl living OFF GRID

Why the us gov reshapes the mississippi river, what significance did the cumberland road hold during the 19th century on quizlet.

The Cumberland Road held significant importance during the 19th century. Also known as the National Road , it was the first major improved highway in the United States. Construction of the road began in 1811 and was completed in the 1850s. The road connected the Potomac River in Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River in Wheeling, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), spanning approximately 620 miles.

The Cumberland Road played a crucial role in westward expansion during this time period. It served as a vital transportation link between the eastern and western parts of the country. The road provided a reliable route for settlers, traders, and merchants to travel from the densely populated East Coast to the expanding frontier regions in the Midwest and beyond.

In addition to facilitating commerce and migration, the Cumberland Road also served military purposes. It was a significant route for moving troops and supplies during times of conflict, such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War.

The construction of the Cumberland Road spurred economic growth along its route. Towns and settlements developed around the road, benefiting from increased trade and traffic. Inns, taverns, and businesses thrived along the road, providing services and accommodations to travelers.

The Cumberland Road also set a precedent for future infrastructure projects in the United States. It highlighted the importance of a national transportation network and paved the way for future investments in roads, canals, and railroads to further connect the growing nation.

The Cumberland Road held great significance during the 19th century as it facilitated westward expansion, promoted economic growth, and served as a crucial transportation link between the eastern and western regions of the United States.

Was the Cumberland Road significant because it was the first road?

The Cumberland Road was indeed significant in the context of the 19th century. It was not the first road in the United States, but it was the first major federally funded transportation project . The construction of the Cumberland Road began in 1811 and it was completed in 1852. It connected Cumberland, Maryland with Vandalia, Illinois, covering a distance of approximately 620 miles.

Why was it significant? The Cumberland Road was a crucial link between the eastern and western parts of the country, providing a reliable transportation route for both people and goods. It played a key role in opening up the western territories and stimulating growth and settlement in those areas. The road facilitated trade, migration, and communication, promoting economic development and national unity.

The Cumberland Road also served as a model for future infrastructure projects in the United States. It demonstrated the effectiveness of federal investment in transportation and led to the development of other important transportation systems such as canals and railways. The road’s construction also sparked discussions and debates about the role of the federal government in improving infrastructure and promoting national development.

While the Cumberland Road was not the first road in the United States, it was significant because it was the first major federally funded transportation project. Its construction and impact on national development paved the way for further transportation advancements in the 19th century .

What was the significance of the Cumberland Road on quizlet?

The Cumberland Road was a major transportation project in the 19th century that played a significant role in the development and expansion of the United States. It was the first federally funded road in the country and served as a crucial link between the eastern states and the western frontier.

One of the main significances of the Cumberland Road was its impact on trade and commerce. The road connected various towns and cities, allowing for easier transportation of goods and facilitating economic growth. It provided a reliable and efficient route for merchants to transport their products to new markets, which stimulated trade and helped to expand the national economy.

The Cumberland Road also had a profound effect on westward expansion and settlement. It opened up new territories for exploration and settlement, serving as a gateway to the vast regions beyond the Appalachian Mountains. The road provided a means for pioneers, settlers, and immigrants to travel westward, leading to the establishment of new communities and facilitating the growth of the nation.

Furthermore, the Cumberland Road played a crucial role in improving communication and transportation. Prior to its construction, travel was often slow and difficult, with poor road conditions and limited infrastructure. The road’s construction and maintenance by the federal government set a precedent for the development of future transportation projects, such as canals and railroads, which further improved connectivity and communication across the country.

In summary, the significance of the Cumberland Road in the 19th century was its contribution to trade, westward expansion, and improved transportation infrastructure. It played a pivotal role in fostering economic growth, facilitating settlement, and paving the way for future advancements in transportation.

What made the Cumberland Road a significant accomplishment of the American system quizlet?

The Cumberland Road was a significant accomplishment of the American system during the 19th century. It was the first federally funded highway in the United States, serving as an important transportation link between the Eastern seaboard and the western frontier. Constructed between 1811 and 1837, the road played a crucial role in opening up the West for settlement and economic development.

The significance of the Cumberland Road can be seen in several aspects:

1. Improved transportation: The construction of the road provided a reliable and efficient means of transportation for people, goods, and ideas across vast distances. It connected towns and settlements, stimulating trade and commerce.

2. National unity: The Cumberland Road became a symbol of national unity as it linked the East and the West, fostering a sense of shared purpose and identity. It helped to bind the growing country together and solidify the concept of Manifest Destiny.

3. Economic growth: The road facilitated the movement of goods and resources, promoting economic growth and development in the regions it passed through. It boosted trade, drove investment, and spurred the growth of industries along its route.

4. Influence on future infrastructure projects: The successful completion of the Cumberland Road set a precedent for future federally funded infrastructure projects, such as canals, railroads, and other roads. It demonstrated the government’s commitment to internal improvements and the role of public works in advancing the nation’s interests.

The Cumberland Road was a significant accomplishment of the American system in the 19th century due to its role in improving transportation, fostering national unity, promoting economic growth, and influencing future infrastructure projects.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the significance of cumberland road in terms of westward expansion during the 19th century.

The Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road, was a significant factor in facilitating westward expansion during the 19th century. It was the first major improved highway funded by the federal government , which played a crucial role in connecting the eastern states with the rapidly growing western territories.

Construction of the Cumberland Road began in 1811 and extended from Cumberland, Maryland to Vandalia, Illinois, covering a distance of approximately 620 miles. The road was designed to provide a reliable transportation route for settlers, merchants, and the military to travel across the Appalachian Mountains and into the western frontier.

One of the main reasons the Cumberland Road was so significant was its impact on trade and commerce . It opened up access to new markets and facilitated the movement of goods and agricultural products between the East and the West. This led to economic growth and development in the regions along the road, as well as increased trade with neighboring states.

Additionally, the Cumberland Road encouraged migration and settlement in the western territories . The improved transportation infrastructure made it easier for settlers to travel westward, leading to the establishment of new towns and communities along the road. This, in turn, contributed to the rapid expansion of the United States and the eventual settlement of the entire continent.

The Cumberland Road also had military significance . It provided a vital route for the movement of troops and supplies, particularly during the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. The federal government recognized that maintaining a reliable transportation network was essential for national defense and security.

However, the significance of the Cumberland Road diminished over time as other forms of transportation, such as canals and railroads, emerged. These newer modes of transportation offered faster and more efficient ways of moving people and goods long distances. Nonetheless, the Cumberland Road’s establishment marked an important milestone in American history and played a crucial role in promoting westward expansion during the 19th century.

How did the construction of Cumberland Road contribute to economic development in the 19th century?

The construction of the Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road, played a significant role in contributing to economic development in the 19th century. The road was the first major improved highway in the United States and became a crucial transportation route, connecting the eastern seaboard with the western frontier.

The Cumberland Road opened up new opportunities for trade and commerce by providing a reliable transportation corridor that stretched across several states. Previously, travel and trade between the eastern and western regions were challenging due to the lack of proper roads and infrastructure. With the completion of the Cumberland Road, it became easier and more efficient for merchants, farmers, and settlers to transport their goods, produce, and livestock.

The road stimulated economic growth along its route , as communities along the way benefited from increased trade and traffic. Towns and settlements developed along the road, creating new markets and opportunities for businesses. The road acted as a catalyst for the growth of industries such as farming, mining, and manufacturing, as access to distant markets became more feasible.

The construction of the road also created jobs and stimulated local economies . Thousands of workers were employed in building and maintaining the road, providing income and employment opportunities for local communities. Additionally, the presence of the road attracted businesses and services such as inns, taverns, and repair shops, which further contributed to local economic development.

The Cumberland Road improved communication and transportation network by linking various regions and promoting the exchange of ideas, information, and technologies. This facilitated the exchange of agricultural practices, technological advancements, and cultural influences, contributing to overall societal development.

The construction of the Cumberland Road had a profound impact on economic development in the 19th century. It facilitated trade, stimulated local economies, created jobs, and improved communication and transportation networks, ultimately contributing to the growth and prosperity of the United States during this period.

In what ways did Cumberland Road facilitate transportation and communication during the 19th century?

The Cumberland Road , also known as the National Road, was a major transportation route extending from Cumberland, Maryland to Vandalia, Illinois in the United States. It was one of the first federally funded roads and played a significant role in facilitating transportation and communication during the 19th century.

Facilitating Transportation: The Cumberland Road provided a direct and reliable transportation link between the eastern seaboard and the western territories. Before its construction, travel across the Appalachian Mountains was difficult and time-consuming. The road significantly improved travel efficiency by providing a solid and well-maintained surface for wagons, stagecoaches, and other vehicles.

Additionally, the Cumberland Road enabled the movement of goods and resources across vast distances. Farmers and merchants could transport their products more easily and efficiently, opening up new markets and opportunities for commerce. This led to economic growth and development in the regions along the road.

Enhancing Communication: Alongside its transportation benefits, the Cumberland Road also enhanced communication during the 19th century. The road was dotted with post offices, taverns, and other establishments that served as meeting points and communication hubs. These locations provided individuals with the opportunity to exchange news, information, and correspondence.

Furthermore, the Cumberland Road facilitated the establishment of telegraph lines. The road provided a clear and accessible path for the laying of telegraph wires, allowing for near-instantaneous long-distance communication. This marked a significant advancement in communication technology during the 19th century.

The Cumberland Road played a crucial role in facilitating transportation and communication during the 19th century. It improved travel efficiency, enabled the movement of goods, and served as a platform for exchanging information and establishing telegraph lines. Its impact on transportation and communication contributed to the growth and development of the United States during this period.

The Cumberland Road played a vital role in shaping the infrastructure and development of the United States during the 19th century. Its significance cannot be understated as it was the first federally funded road project that connected the East Coast to the rapidly expanding western territories. The construction of this road not only facilitated transportation and trade between states but also opened up new opportunities for settlement, commerce, and economic growth.

The Cumberland Road served as a lifeline for towns and cities along its route, stimulating local economies and creating job opportunities for countless individuals. It provided a vital link between the eastern markets and the vast resources of the western frontier, enabling the efficient movement of goods, people, and ideas. This road became a symbol of progress and manifested the growing power and influence of a young nation.

Furthermore, the Cumberland Road laid the foundation for future road-building initiatives in the United States. Its success paved the way for subsequent federally funded projects, signaling a shift towards increased government involvement in infrastructure development. The lessons learned from the construction and maintenance of this road would shape the way transportation networks were built and maintained in the years to come.

Today, the legacy of the Cumberland Road can still be seen in the form of modern highways and interstates that span across the country. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity and determination of the individuals who envisioned and executed such a transformative project during a time of unparalleled expansion and growth.

In retrospect, the Cumberland Road was more than just a road – it was a catalyst for progress, unity, and prosperity. Its impact on the 19th-century America cannot be overstated, as it solidified the notion of a nation connected by infrastructure, fostering economic growth and societal advancement.

To learn more about this topic, we recommend some related articles:

Unveiling the Romantic Era: Exploring 19th Century Love Letters

Industrial Revolution in 19th Century Russia: A Catalyst for Transformation and Modernization

The Traditional Homes of 19th Century Samurai: A Glimpse into the Noble Lifestyle

The Devastating Impact of Syphilis in the 19th Century: Unveiling the Grim Reality

The Revolutionary Contributions of 19th Century Chemists: Pioneering Discoveries That Shaped Modern Science

Unveiling the Timeless Elegance of 19th Century Sinks: A Walkthrough of their Design and Functionality

The National Road, America's First Major Highway

A Road From Maryland to Ohio Helped America Move Westward

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

The National Road was a federal project in early America designed to address a problem which seems quaint today but was extremely serious at the time. The young nation possessed enormous tracts of land to the west. And there was simply no easy way for people to get there.

The roads heading westward at the time were primitive, and in most cases were Indian trails or old military trails dating to the French and Indian War. When the state of Ohio was admitted to the Union in 1803, it was apparent that something had to be done, as the country actually had a state that was difficult to reach.

One of the major routes westward in the late 1700s to present day Kentucky, the Wilderness Road, had been plotted by frontiersman Daniel Boone . That was a private project, funded by land speculators. And while it was successful, members of Congress realized they wouldn't always be able to count on private entrepreneurs to create infrastructure.

The U.S. Congress took up the issue of building what was called the National Road. The idea was to build a road which would lead from the center of the United States at the time, which was Maryland, westward, to Ohio and beyond.

One of the advocates for the National Road was Albert Gallatin, the secretary of the treasury, who would also issue a report calling for the construction of canals in the young nation.

In addition to providing a way for settlers to get to the west, the road was also seen as a boon to business. Farmers and traders could move goods to markets in the east, and the road was thus seen as necessary to the country’s economy.

The Congress passed legislation allocating the sum of $30,000 for the building of the road, stipulating that the President should appoint commissioners who would supervise the surveying and planning. President Thomas Jefferson signed the bill into law on March 29, 1806.

Surveying for the National Road

Several years were spent planning the route of the road. In some parts, the road could follow an older path, known as the Braddock Road, which was named for a British general in the French and Indian War . But when it struck out westward, toward Wheeling, West Virginia (which was then part of Virginia), extensive surveying was required.

The first construction contracts for the National Road were awarded in the spring of 1811. Work began on the first ten miles, which headed west from the town of Cumberland, in western Maryland.

As the road began in Cumberland, it was also called the Cumberland Road.

The National Road Was Built to Last

The biggest problem with most roads 200 years ago was that wagon wheels created ruts, and even the smoothest dirt roads could be rendered nearly impassable. As the National Road was considered vital to the nation, it was to be paved with broken stones.

In the early 1800s a Scottish engineer, John Loudon MacAdam , had pioneered a method of building roads with broken stones, and roads of this type were thus named “macadam” roads. As work proceeded on the National Road, the technique advanced by MacAdam was put to use, giving the new road a very solid foundation that could stand up to considerable wagon traffic.

The work was very difficult in the days before mechanized construction equipment. The stones had to be broken by men with sledgehammers and were put into position with shovels and rakes.

William Cobbett, a British writer who visited a construction site on the National Road in 1817, described the construction method:

"It is covered with a very thick layer of nicely broken stones, or stone, rather, laid on with great exactness both as to depth and width, and then rolled down with an iron roller, which reduces all to one solid mass. This is a road made for ever."

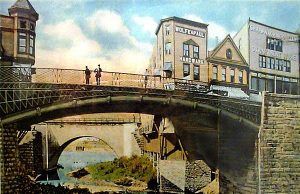

A number of rivers and streams had to be crossed by the National Road, and this naturally led to a surge in bridge building. The Casselman Bridge, a one-arch stone bridge built for the National Road in 1813 near Grantsville, in the northwest corner of Maryland, was the longest stone arch bridge in America when it opened. The bridge, which has an 80-foot arch, has been restored and is the centerpiece of a state park today.

Work on the National Road continued steadily, with crews heading both eastward and westward from the origin point in Cumberland, Maryland. By the summer of 1818, the road's western advance had reached Wheeling, West Virginia.

The National Road slowly continued westward and eventually reached Vandalia, Illinois, in 1839. Plans existed for the road to keep going all the way to St. Louis, Missouri, but as it seemed that railroads would soon supersede roads, funding for the National Road was not renewed.

Importance of the National Road

The National Road played a major role in the westward expansion of the United States, and its importance was comparable to that of the Erie Canal . Travel on the National Road was reliable, and many thousands of settlers going westward in heavily loaded wagons got their start by following its route.

The road itself was eighty feet wide, and distances were marked by iron mile posts. The road could easily accommodate the wagon and stagecoach traffic of the time. Inns, taverns, and other businesses sprang up along its route.

An account published in the late 1800s recalled the glory days of the National Road:

"There were sometimes twenty gaily-painted four-horse coaches each way daily. The cattle and sheep were never out of sight. The canvas-covered wagons were drawn by six or twelve horses. Within a mile of the road the country was a wilderness, but on the highway the traffic was as dense as in the main street of a large town."

By the middle of the 19th century, the National Road fell into disuse, as railroad travel was much faster. But when the automobile arrived in the early 20th century the route of the National Road enjoyed a resurgence in popularity, and over time the first federal highway became the route for a portion of US Route 40. It is still possible to travel portions of the National Road today.

Legacy of the National Road

The National Road was the inspiration for other federal roads, some of which were constructed during the time the nation's first highway was still being built.

And the National Road was also enormously important as it was the first large federal public works project, and it was generally seen as a great success. And there was no denying that the nation's economy, and its westward expansion, were greatly helped by the macadamized road that stretched westward toward the wilderness.

- 4 Routes to the West Used by American Settlers

- Henry Clay's American System of Economics

- Albert Gallatin's Report on Roads, Canals, Harbors, and Rivers

- Exploration of the West in the 19th Century

- Coxey's Army: 1894 March of Unemployed Workers

- The Executive Branch of US Government

- 10 of the Most Influential Presidents of the United States

- Biography of Jacob J. Lew, Former Secretary of the Treasury

- Great Depression Pictures

- American History Timeline: 1820-1829

- Timeline from 1810 to 1820

- Life of John Jay, Founding Father and Supreme Court Chief Justice

- Lecompton Constitution

- Great Railroad Strike of 1877

- John Quincy Adams: 6th President of the United States

- What Is the Doctrine of Discovery?

Legends of America

Traveling through american history, destinations & legends since 2003., the national road – first highway in america.

The National Road, built in 1811, makes a path through Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Photo Map courtesy Fort Necessity National Battlefield.

By the early 19th Century, the wilderness of Ohio had given way to settlement. The road that George Washington had cut through the forest many years before called the Braddock Road, was replaced by the National Road.

Cutting an approximately 820-mile-long path through Illinois , Indiana , Maryland , Ohio , Pennsylvania , and West Virginia , it was built between 1811 and 1834 and was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to unify the young country. On March 29, 1806, Congress authorized the construction of the road, and President Thomas Jefferson signed the act establishing what was first called the Cumberland Road that would connect Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River.

Building the National Road.

The contract for the construction of the first section was awarded to Henry McKinley on May 8, 1811, and construction began later that year, with the road reaching Cumberland, Maryland, and Uniontown, Pennsylvania, in 1817. It was completed to the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia, on August 1, 1818, and mail coaches began using the road. Wheeling would remain its western terminus for several years. Eventually, the road was pushed through central Ohio and Indiana, reaching Vandalia, Illinois, in the 1830s. At that time, it became the first road in the U.S. to use the new macadam road surfacing. During that decade, the federal government conveyed part of the road’s responsibility to the states through which it runs. Tollgates and tollhouses were then built by the states. Plans were made to continue the road to St. Louis , Missouri , at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and to Jefferson City upstream on the Missouri River. However, following the panic of 1837, funding ran dry, and construction was stopped, leaving the terminus at Vandalia, Illinois.

The opening of the National Road saw thousands of travelers heading west over the Allegheny Mountains to settle the rich land of the Ohio River Valley. It also became a corridor for moving goods and supplies. Small towns along the National Road’s path began to grow and prosper with the increase in population. Towns such as Cumberland, Maryland; Uniontown, Brownsville, and Washington, Pennsylvania; and Wheeling, West Virginia, evolved into commercial centers of business and industry. Uniontown was the headquarters for three major stagecoach lines , which carried passengers over the National Road. Brownsville was a center for steamboat building and river freight hauling on the Monongahela River. Many small towns and villages along the road contained taverns, blacksmith shops, and livery stables.

Thomas Searight remembered as many as 20 stagecoaches in a line on the road at one time. Another man named Jesse Peirsol, a wagoner, remembers a night at a tavern when 30 six-horse teams were parked in the wagon yard, 100 mules were in a pen, 1,000 hogs were in an enclosure, and as many cattle were in the field.

Mount Washington Tavern, Uniontown, Pennsylvania, 1933.

Taverns were probably the most important and numerous businesses on the National Road. It is estimated there was about one tavern on every mile of the road. There were two classes of taverns, including the stagecoach tavern, which was more expensive and designed for the affluent traveler, and the wagon stand, which was more affordable for most travelers. The Mount Washington Tavern, which still stands in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, as part of Fort Necessity National Battlefield, was a stagecoach tavern. Regardless of class, all taverns offered three basic things: food, drink, and lodging.

During the heyday of the National Road, traffic was heavy throughout the day and into the early evening. Almost every kind of vehicle could be seen on the road. The two most common vehicles were the stagecoach and the Conestoga wagon. Stagecoach travel was designed with speed in mind and would average 60 to 70 miles in one day. The Conestoga wagon was the “tractor-trailer” of the 19th Century. Conestogas were designed to carry heavy freight. They were often brightly painted with red running gears, Prussian blue bodies, and white canvas coverings. A Conestoga wagon, pulled by a team of six draft horses, averaged 15 miles daily.

The height of the National Road’s popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting, and poetry. During the 1840s, popularity soared again as westbound travelers and drovers crowded the inns and taverns. Massive Conestoga wagons hauled produce from frontier farms to the East Coast, returning with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands moved west in covered wagons, and stagecoaches traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In 1848, Robert S. McDowell counted 133 wagons pulled by six-horse teams that passed along the National Road in one day. He took “no notice of as many more teams of one, two, three, four, and five horses.

Sunrise in the Alleghenies, Gibson and Co, 1880.

By the early 1850s, technology was changing the way people traveled. The steam locomotive was being perfected, and soon, railroads would cross the Allegheny Mountains. The people of Southwestern Pennsylvania fought vigorously to keep the railroad out of the area, knowing its impact on the National Road. However, in 1852, the Pennsylvania Railroad was completed to Pittsburgh, and shortly after, the B & O Railroad reached Wheeling, West Virginia. This spelled doom for the National Road, as the traffic quickly declined, and many taverns went out of business.

An article in Harper’s Magazine in November 1879 declared:

“The national turnpike that led over the Alleghenies from the East to the West is a glory departed… Octogenarians who participated in the traffic will tell an enquirer that never before was there such landlords, such taverns, such dinners, such whiskey… or such endless cavalcades of coaches and wagons.”

A poet lamented, “We hear no more the clanging hoof and the stagecoach rattling by, for the steam king rules the traveled world, and the Old Pike is left to die.”

National Old Trails Road in Colorado.

In 1912, the pathway became part of the National Old Trails Road. Just a few years later, just as technology caused the National Road to decline, it also led to its revival with the invention of the automobile in the early 20th Century. As “motor touring” became popular, the need for improved roads grew. Many early wagon and coach roads, such as the National Road, were revived into smoothly paved automobile roads. The Federal Highway Act of 1921 established a program of federal aid to encourage the states to build “an adequate and connected system of highways, interstate in character.” In 1926, the grid system of numbering highways was in place, thus creating U.S. Route 40 out of the ashes of the National Road.

This spurred a generation of new businesses — stage taverns and wagon stands were replaced by hotels, motels, restaurants, and diners. The service station replaced the livery stables and blacksmith shops. With the influx of new businesses, some National Road-era buildings regained new life. Route 40 was a major east-west artery until the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the interstate system. Much of the traffic was diverted away, and interest in the National Road again waned.

Decades later, however, new generations are finding these older two-lane roads a more relaxing journey and are again enjoying the history. Today, the old pavement is a National Scenic Byway where visitors can experience a physical timeline, including classic inns, tollhouses, diners, and motels that trace 200 years of American history . Cameras capture old buildings, bridges, and stone mile markers along this historic path. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside; some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence, and others stand abandoned.

Numerous sites on the National Road are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A few of these include:

Dunlap’s Creek Bridge, Brownsville, Pennsylvania.

- Casselman River Bridge near Grantsville, Maryland.

- Near Brownsville, Pennsylvania, Dunlap’s Creek Bridge was the first cast-iron arch bridge in the United States, completed in 1839.

- Huddleston Farmhouse Inn in Mount Auburn, Indiana.

- James Whitcomb Riley House in Indiana.

- National Road Corridor Historic District in Wheeling, West Virginia.

- Old Stone Arch, National Road, near Marshall, Illinois.

- Petersburg Tollhouse in Addison, Pennsylvania.

- The Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio, was built in 1837.

- Road Segment of the road in Cambridge, Ohio.

- Searight’s Tollhouse, National Road, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

- S Bridge in Washington County, Pennsylvania, near Washington, Pennsylvania.

- Wheeling Suspension Bridge in Wheeling, West Virginia.

© Kathy Alexander / Legends of America , updated May 2024.

American History Main Page

American Transportation

Byways & Historic Trails

Fort Necessity – Defending Against the French

See Sources .

History Of The Road

There is no Event

“The road to hell is paved with adverbs.” – Stephen King

History of the Road

National History

Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson, developed the concept of the Historic National Road, alternately now known primarily as Route 40. Authorized by Congress in 1806, it became the nation’s first federally funded interstate highway opening up the country and facilitating America’s westward expansion.

In 1811, a contract was awarded to build the first 10 miles of road in compliance with strict requirements regarding the road’s width, surface and elevations. By 1818, the road had crossed Pennsylvania and western Virginia (now West Virginia) reaching as far as the Ohio River at Wheeling.

“There were sometimes twenty gaily painted four-horse coaches each way daily. The cattle and sheep were never out of sight. The canvas-covered wagons were drawn by six or twelve horses. Within a mile of the road the country was a wilderness, but on the highway the traffic was as dense as in the main street of a large town.” –Annual James Shaull Wagon Train Festival

Debate over the constitutionality of internal improvements served to delay extension of the road for several years. By the 1830s, the federal government had conveyed the responsibility for maintenance of the road to the states through which it runs. The Historic National Road soon became a toll road as most of the states erected toll gates and toll houses to collect fees from those using the road.

As work on the Road progressed, a settlement pattern of towns and villages developed that is still visible to travelers today. The Road became Main Street in these early settlements, earning the nickname “The Main Street of America.”

Mile markers were an important component in early Historic National Road travel. These markers lined the road serving to tell travelers how far they were from their destination and became an important icon in early Historic National Road travel.

The 1840s were peak years for travel along the Road. Taverns and inns enjoyed brisk business and the Historic National Road was celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry. Stage lines transported many famous persons along the nation’s “Main Street,” including presidents and future presidents, such as Monroe, Jackson, Polk, Taylor, Harrison, Fillmore, Van Buren, Buchanan and Lincoln, as well as notables such as Lafayette, Albert Gallatin, Henry Clay, Sam Houston, Daniel Webster, Davy Crockett, Chief Blackhawk, Jenny Lind, and P.T. Barnum. Huge Conestoga wagons hauled produce from frontier farms to the East Coast, returning with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements.

By the middle of the 19th Century, a new form of transportation, the railroad, overshadowed the Historic National Road and the prominence and prosperity of the Road was overtaken by the “iron horse.” The Historic National Road experienced a steady decline in use because of the expansion of canal and railroad systems.

Life along the Historic National Road grew quiet for a time but all changed in the early 20th Century with the coming of the automobile and a new wave of touring in motorcars. Tourists driving the road stopped at many waysides to eat, to shop, and to sleep causing a new generation of travel and entertainment facilities to appear on the landscape to meet their needs – gas stations, restaurants, motels and tourist cabins, drive-in restaurants and drive-in theaters.

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, as the first federal highway funding law, established federal aid for highways as a national policy and was instrumental in extending and improving the country’s road system. The Federal Highway Act of 1921 provided for a national highway system of roads that would allow for transcontinental travel. Many roads including the Historic National Road were realigned and incorporated as part of the U.S. Highway System that changed named roads to numbered roads such as designating the Historic National Road as U.S. Route 40.

Now, the new Historic National Road, U.S. Route 40, is the busiest it has been since its heyday of the 1840s. However, instead of Conestoga wagons and stagecoaches, there are tractor-trailer trucks, buses and automobiles. Inns and taverns have been updated as restaurants, motels and hotels. The hustle and bustle of travel has returned to the Road.

The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956 served to create a limited-access interstate system. Interstate Highways 70 and 68 were constructed, and superseded U.S. Route 40 as the primary transportation routes through the region. U.S. Route 40 was bypassed and became a local, secondary, alternate, or, a scenic road.

The Historic National Road was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1976 and a State Heritage Park in 1994. It also earned the designation as a National Scenic Byway and All-American Road in 2002.

Explore the other states

- Pennsylvania

- West Virginia

- Ohio

One For The Road

Join our mailing list so you don’t miss a thing!

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

PO Box 71 Boonsboro, MD 21713

Email the nrhf.

© Copyright 2021 Maryland National Road Association. Funded by the Delaplaine Foundation. Designed by Octavo Designs .

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

The national road.

The National Road was the first highway built entirely with federal funds. The road was authorized by Congress in 1806 during the Jefferson Administration. Construction began in Cumberland, Maryland in 1811. The route closely paralleled the military road opened by George Washington and General Braddock in 1754-55.

By 1818 the road had been completed to the Ohio River at Wheeling, which was then in Virginia. Eventually the road was pushed through central Ohio and Indiana reaching Vandalia, Illinois in the 1830's where construction ceased due to a lack of funds. The National Road opened the Ohio River Valley and the Midwest for settlement and commerce.

The opening of the National Road saw thousands of travelers heading west over the Allegheny Mountains to settle the rich land of the Ohio River Valley. Small towns along the National Road's path began to grow and prosper with the increase in population. Towns such as Cumberland, Uniontown, Brownsville, Washington and Wheeling evolved into commercial centers of business and industry. Uniontown was the headquarters for three major stagecoach lines which carried passengers over the National Road. Brownsville, on the Monongahela River, was a center for steamboat building and river freight hauling. Many small towns and villages along the road contained taverns, blacksmith shops, and livery stables.

Part of a series of articles titled National Road - America's First Federally Funded Highway .

Next: Traveling on the National Road

You Might Also Like

- fort necessity national battlefield

- friendship hill national historic site

- national road

- transportation history

- transportation

- path of progress

Fort Necessity National Battlefield , Friendship Hill National Historic Site

Last updated: June 12, 2022

An official website of the United States government Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

The National Road

By Rickie Longfellow

The National Road, in many places known as Route 40, was built between 1811 and 1834 to reach the western settlements. It was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary for unifying the young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River.

In 1811 the first contract was awarded and the first 10 miles of road built. By 1818 the road was completed to Wheeling and mail coaches began using the road. By the 1830s the federal government conveyed part of the road's responsibility to the states through which it runs. Tollgates and tollhouses were then built by the states, with the federal government taking responsibility for road repairs.

As work on the road progressed a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages are found along the National Road, many barely touched by the passing of time. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning the nickname "The Main Street of America." The height of the National Road's popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry. During the 1840s popularity soared again. Travelers and drovers, westward bound, crowded the inns and taverns along the route. Huge Conestoga wagons hauled produce from frontier farms to the East Coast, returning with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands moved west in covered wagons and stagecoaches traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In the 1870s, however, the railroads came and some of the excitement faded. In 1912 the road became part of the National Old Trails Road and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal Aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926 the road became part of US 40 as a coast-to-coast highway. As the interstate system has grown throughout America, interest in the National Road again waned. However, now when we want to have a relaxing journey with some history thrown in, we again travel the National Road. Cameras capture old buildings, bridges and old stone mile markers. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside and some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence and others stand abandoned.

Historic stone bridges on the National Road have their own stories to tell as well as reminding us of the craftsmanship of early engineers. The S Bridge, so named because of its design, stands 4 miles east of Old Washington, Ohio. Built in 1828 as part of the National Road, it is a single arch stone structure. This one of four in the state is deteriorated and is now used for only pedestrian traffic. However the owners of the bridge are attempting to obtain funding for its restoration. The stone Casselman River Bridge still stands east of Grantsville, Maryland. A product of the early 19th century federal government improvements program along the National Road, the Casselman River Bridge was constructed in 1813-1814. Its 80-foot span, the largest of its type in America, connected Cumberland to the Ohio River. In 1933 a new steel bridge joined the banks of the Casselman River. The old stone bridge, partially restored by the State of Maryland in the 1950s is now the center of Casselman River Bridge State Park.

Mile markers have been used in Europe for more than 2,000 years and our European ancestors continued that tradition here in America. These markers tell travelers how far they are from their destination and were an important icon in early National Road travel. As children we saw them and asked our parents what they were. As adults we nostalgically seek them out for photographing. A drive through National Road towns usually reveals one of these markers, such as the one standing by the historic Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio.

In the 1960s Interstate 70, leaving many businesses by the wayside, bypassed Route 40 and much of the National Road. The emphasis was on faster cars and quicker arrival time. We scurry along at a hurried pace today, but when we want to relax, take our time and see some sights, we once again travel the National Road. The timeless little villages in quiet hamlets and valleys beckon us to small restaurants for a home cooked meal and a trip back in time when the pace of life was slower and less stressful. As we returned to present day, via the Interstate which often parallels the National Road, we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses to pay silent tribute to the ghostly presence of cattle drives, Conestoga wagons and a relentless quest for the west.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Industrial Transformation in the North, 1800–1850

On the Move: The Transportation Revolution

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the development of improved methods of nineteenth-century domestic transportation

- Identify the ways in which roads, canals, and railroads impacted Americans’ lives in the nineteenth century

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who traveled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about what historians call the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems. People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress and the greatness of the republic. In 1817, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina looked to a future of rapid internal improvements, declaring, “Let us . . . bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established and extensive system of railroads.

ROADS AND CANALS

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road , a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which (as today) charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travelers immense amounts of time and money. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal going around the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward, in this case by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal ( [link] ), which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods (more than $200 million in today’s money) was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

Explore the Erie Canal on ErieCanal.org via an interactive map. Click throughout the map for images of and artifacts from this historic waterway.

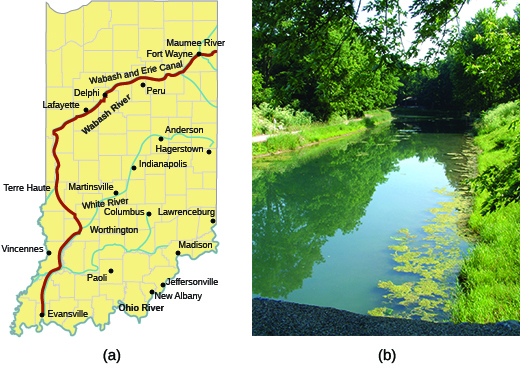

The success of the Erie Canal led to other, similar projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal, which opened in the early 1840s, stretched over 450 miles, making it the longest canal in North America ( [link] ). Canals added immensely to the country’s sense of progress. Indeed, they appeared to be the logical next step in the process of transforming wilderness into civilization.

Visit Southern Indiana Trails to see historic photographs of the Wabash and Erie Canal:

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

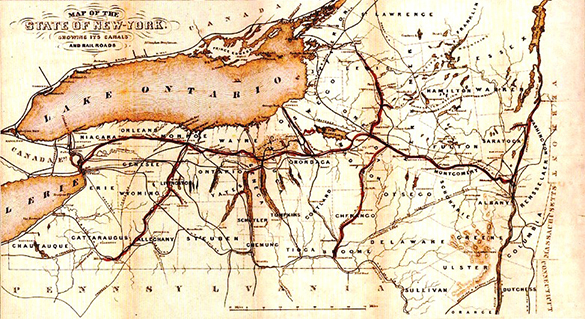

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states ( [link] ), providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

AMERICANS ON THE MOVE

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the market revolution would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution. Traveling circuses, menageries, peddlers, and itinerant painters could now more easily make their way into rural districts, and people in search of work found cities and mill towns within their reach.

Section Summary

A transportation infrastructure rapidly took shape in the 1800s as American investors and the government began building roads, turnpikes, canals, and railroads. The time required to travel shrank vastly, and people marveled at their ability to conquer great distances, enhancing their sense of the steady advance of progress. The transportation revolution also made it possible to ship agricultural and manufactured goods throughout the country and enabled rural people to travel to towns and cities for employment opportunities.

Review Questions

Which of the following was not a factor in the transportation revolution?

What was the significance of the Cumberland Road?

What were the benefits of the transportation revolution?

The Cumberland Road made transportation to the West easier for new settlers. The Erie Canal facilitated trade with the West by connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie. Railroads shortened transportation times throughout the country, making it easier and less expensive to move people and goods.

On the Move: The Transportation Revolution Copyright © 2014 by OpenStaxCollege is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Calendar of Events

- Host Your Event

Explore & Learn / Historic Site / The National Road

The National Road

Description

America’s First Highway Venture: The National Road

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Pike or Cumberland Turnpike) was the first American highway funded by Congress. President George Washington was among those who early on saw the value of a highway, one that would lead from Maryland, the center of the United States at that time, westward to Ohio and beyond. Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, became a strong proponent during the administration of President Thomas Jefferson. Following Congressional action, Jefferson signed an initial $30,000 allocation on March 29, 1806, Henry McKinley received the initial contract on May 8, 1811, and construction began later that year. As originally conceived, its 620-mile path began at the edge of the Potomac River in Cumberland, MD, reached Wheeling, VA (now WV) in 1818, and extended to the Kaskaskia River in Vandalia, IL in 1841.

Although Congress approved an extension to St. Louis on the Mississippi River and then west to Jefferson City, M O on May 15, 1820, the final federal appropriation occurred on May 25, 1838 , and construction short of completion concluded in 1839 . By 1840, Congress voted against completion of the road , consistent with an 1835 federal decision to transfer future construction and maintenance costs to the states through which the highway passed. The states then introduced tolls and tollbooths to cover maintenance costs.

As shown in the map (Figure 2) , d escri ptions of the National Road today show the road beg inning in Baltimore , 1 18 miles to the east of Cumberland . A series of private toll roads (known as the Old National Pike or the Baltimore Pike) offered Improved t ravel between th os e two communities before authorization of the National Road . Over time, the entire highway from Baltimore to Vandalia , IL gained recognition as the National Road.

Proponents outside and within Congress believed that a National Road warranted federal funding for two principal reasons — population growth and economic development. The US Census for the decades beginning from 1790 to 1800 and then to 1810 showed increases in population exceeding 33% in each decade. In addition, Americans were rapidly moving west. Ohio was admitted to the Union in 1803, followed by Indiana (1816) and Illinois (1818). Economically, there was an ever-growing need for goods produced or imported by the major cities of Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York to reach and meet the necessities of those living on the western frontier. Equally strongly, the goods generated in the newly developed western farms and towns needed to reach those living along the Atlantic coast.

The route of the National Road initially followed paths and trade routes extending as far back as the French and Indian War (1753-1763). Named for British General Edward Braddock, the so-called Braddock Road led from Fort Cumberland in Maryland to Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh, PA) during that period. Additional surveying led to route modifications and improvements throughout the life of the National Road.

At the time of planning for the National Road, the great difficulty of all travel routes west was their lack of hard surfaces. The result was constant deep and troublesome ruts from the wheels of heavily loaded wagons and stagecoaches. The National Road builders introduced new techniques to avoid those problems. (Figure 5) The road was wide enough to permit wagons and coaches to pass each other from opposite directions and banked so that water would easily drain to the sides. Stone markers recorded distances to the east and west. More significantly, the builders introduced a new construction method, borrowing the thinking of British engineer, John Louden MacAdam. William Cobbett, a British writer who visited a construction site on the National Road in 1817, described the construction method:

“It is covered with a very thick layer of nicely broken stones, or stone, rather, laid on with great exactness both as to depth and width, and then rolled down with an iron roller, which reduces all to one solid mass. This is a road made for ever.”

T raveling on the National Road was primarily by stagecoach and lumbering Conestoga wagons. Stages were for speedy passenger travel and might average 60 to 70 miles per day. Conestoga wagons were the “tractor trailers” of the 19 th century and averaged fifteen miles per day. (Figure 6 & 7)

Serving travelers, wagoneers, coachmen and their vehicles and horses were the taverns providing lodging, food, and beverages. Some have suggested that there was a tavern for every mile of the road. “Stagecoach taverns” served the more affluent travelers; others found the more affordable “wagon stands” to be satisfactory. (Figure 8)

The National Road reached its height in popularity by 1825 and continued as the principal means of reaching the western frontier in to the 1840’s. However, b y the early 1850’s, use of the National Road diminish ed because of the westward growth of the steam powered B altimore & O hio and Pennsylvania Railroads which moved people and goods much faster than horse- drawn vehicles.

“An account published in the late 1800’s recalled the glory days of the National Road

There were sometimes twenty gaily painted four-horse coaches each way daily. The cattle and sheep were never out of sight. The canvas-covered wagons were drawn by six or twelve horses. Within a mile of the road the country was a wilderness, but on the highway the traffic was as dense as in the main street of a large town.” 1

“An article in Harper’s Magazine in 1879 declared

The national turnpike that led over the Alleghenies from the East to the West is a glory departed . . . Octogenarians who participated in the traffic will tell an enquirer that never before were there such landlords, such taverns, such dinners, such whiskey . . . or such endless cavalcades of coaches and wagons” 2

“A poet lamented,

We hear no more the clanging hoof and the stagecoach rattling by, for the steam king rules the traveled world, and the Old Pike is left to die” 3

Many miles of the route, bridges and sites associated with this first nationally funded interstate highway remain today. After declining in use due to the innovative technology of the railroad, it regained a place in American history with the still later technology of the automobile. Autos led to the growing interest of Americans in “motor touring” to historic sites and national parks for vacations.

In response to this growing interest in auto travel, the US established the first national highway numbering system in 1926. Much of the eastern portion of the National Road extending from Baltimore into Ohio became the new US Route 40. A year later, the National Old Trails Road described an early cross-country route extending from New York City to Los Angeles. It also followed a portion of the path of the old National Road.

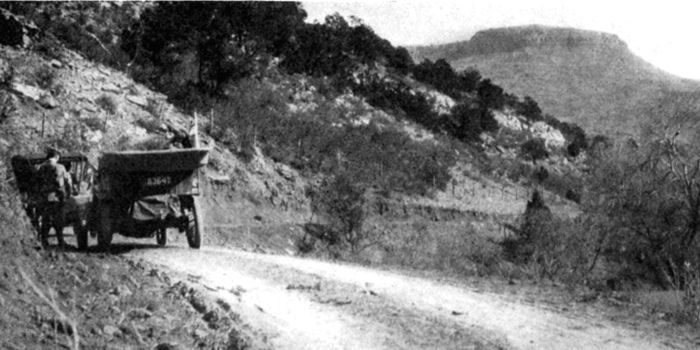

These photographs (Figure 9-11) show 1920 Americans traveling east and west on US Route 40 through the hills and valleys of Maryland. They were following the familiar, “Happy Motoring” slogan of Esso Oil.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Road https://nationalrdfoundation.org/ https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/back0103.cfm https://www.nps.gov/fone/learn/historyculture/nationalroad.htm https://www.nps.gov/articles/national-road.htm https://www.google.com/search?source=univ&tbm=isch&q=National+Road&client=firefox-b-1-d&fir=jpyz35k4BWugEM%25252CJOT49t https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-nationalroad/ https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cumberland-road https://study.com/academy/lesson/national-road-definition-history.htm l https://www.thoughtco.com/the-national-road-1774053

John Geist, Archives Volunteer, and Anna Kresmer, Archivist, December 2022

Can't Get Enough?

There’s even more to explore. Check out this and other unique pieces from our collection.

Did You Know?

Andrew Jackson, in 1833, rode on the B&O Railroad, becoming the first US president to ride a train.

This was an amazing museum to visit! A must see in Baltimore. Starting with the ease of parking...Right onsite and FREE!

Industrial Transformation in the North: 1800–1850

On the move: the transportation revolution, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the development of improved methods of nineteenth-century domestic transportation

- Identify the ways in which roads, canals, and railroads impacted Americans’ lives in the nineteenth century

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who traveled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about what historians call the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems. People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress and the greatness of the republic. In 1817, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina looked to a future of rapid internal improvements, declaring, “Let us . . . bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established and extensive system of railroads.

ROADS AND CANALS

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road , a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which (as today) charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travelers immense amounts of time and money. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal going around the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward, in this case by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal , which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

Although the Erie Canal was primarily used for commerce and trade, in Pittsford on the Erie Canal (1837), George Harvey portrays it in a pastoral, natural setting. Why do you think the painter chose to portray the canal this way?

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods (more than $200 million in today’s money) was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

The success of the Erie Canal led to other, similar projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal, which opened in the early 1840s, stretched over 450 miles, making it the longest canal in North America. Canals added immensely to the country’s sense of progress. Indeed, they appeared to be the logical next step in the process of transforming wilderness into civilization.

This map (a) shows the route taken by the Wabash and Erie Canal through the state of Indiana. The canal began operation in 1843 and boats operated on it until the 1870s. Sections have since been restored, as shown in this 2007 photo (b) from Delphi, Indiana.

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

This 1853 map of the “Empire State” shows the extent of New York’s canal and railroad networks. The entire country’s transportation infrastructure grew dramatically during the first half of the nineteenth century.

AMERICANS ON THE MOVE

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.