- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

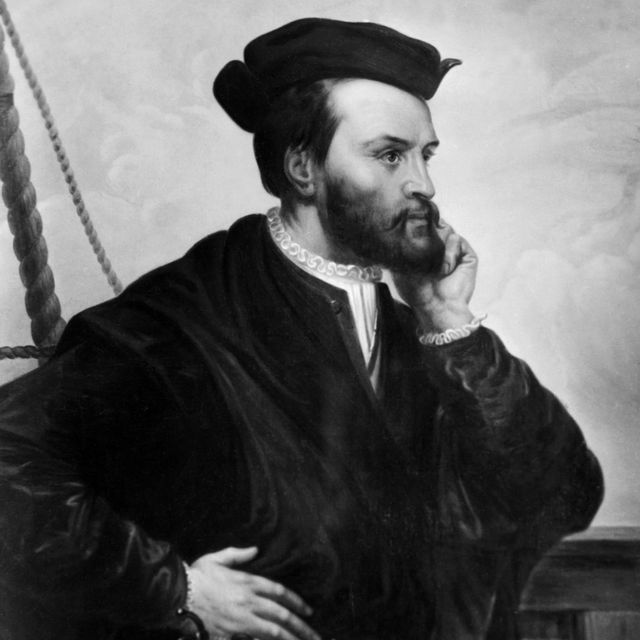

Jacques Cartier

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

In 1534, France’s King Francis I authorized the navigator Jacques Cartier to lead a voyage to the New World in order to seek gold and other riches, as well as a new route to Asia. Cartier’s three expeditions along the St. Lawrence River would later enable France to lay claim to the lands that would become modern-day Canada. He gained a reputation as a skilled navigator prior to making his three famous voyages to North America.

Jacques Cartier’s First North American Voyage

Born December 31, 1491, in Saint-Malo, France, Cartier began sailing as a young man. He was believed to have traveled to Brazil and Newfoundland—possibly accompanying explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano —before 1534.

That year, the government of King Francis I of France commissioned Cartier to lead an expedition to the “northern lands,” as the east coast of North America was then known. The purpose of the voyage was to find a northwest passage to Asia, as well as to collect riches such as gold and spices along the way.

Did you know? In addition to his exploration of the St. Lawrence region, Jacques Cartier is credited with giving Canada its name. He reportedly misused the Iroquois word kanata (meaning village or settlement) to refer to the entire region around what is now Quebec City; it was later extended to the entire country.

Cartier set sail in April 1534 with two ships and 61 men, and arrived 20 days later. During that first expedition, he explored the western coast of Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence as far as today’s Anticosti Island, which Cartier called Assomption. He is also credited with the discovery of what is now known as Prince Edward Island.

Cartier’s Second Voyage

Cartier returned to make his report of the expedition to King Francis, bringing with him two captured Native Americans from the Gaspé Peninsula. The king sent Cartier back across the Atlantic the following year with three ships and 110 men. With the two captives acting as guides, the explorers headed up the St. Lawrence River as far as Quebec, where they established a base camp.

The following winter wrought havoc on the expedition, with 25 of Cartier’s men dying of scurvy and the entire group incurring the anger of the initially friendly Iroquois population. In the spring, the explorers seized several Iroquois chiefs and traveled back to France.

Though he had not been able to explore it himself, Cartier told the king of the Iroquois’ accounts of another great river stretching west, leading to untapped riches and possibly to Asia.

Cartier’s Third and Final Voyage

War in Europe stalled plans for another expedition, which finally went forward in 1541. This time, King Francis charged the nobleman Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval with founding a permanent colony in the northern lands. Cartier sailed a few months ahead of Roberval, and arrived in Quebec in August 1541.

After enduring another harsh winter, Cartier decided not to wait for the colonists to arrive, but sailed for France with a quantity of what he thought were gold and diamonds, which had been found near the Quebec camp.

Along the way, Cartier stopped in Newfoundland and encountered Roberval, who ordered Cartier to return with him to Quebec. Rather than obey this command, Cartier sailed away under cover of night. When he arrived back in France, however, the minerals he brought were found to have no value.

Cartier received no more royal commissions, and would remain at his estate in Saint-Malo, Brittany, for the rest of his life. He died there on September 1, 1557. Meanwhile, Roberval’s colonists abandoned the idea of a permanent settlement after barely a year, and it would be more than 50 years before France again showed interest in its North American claims.

Jacques Cartier. The Mariner’s Museum and Park . The Explorers: Jacques Cartier 1534-1542. Canadian Museum of History .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Jacques Cartier

French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

(1491-1557)

Who Was Jacques Cartier?

French navigator Jacques Cartier was sent by King Francis I to the New World in search of riches and a new route to Asia in 1534. His exploration of the St. Lawrence River allowed France to lay claim to lands that would become Canada. He died in Saint-Malo in 1557.

Early Life and First Major Voyage to North America

Born in Saint-Malo, France on December 31, 1491, Cartier reportedly explored the Americas, particularly Brazil, before making three major North American voyages. In 1534, King Francis I of France sent Cartier — likely because of his previous expeditions — on a new trip to the eastern coast of North America, then called the "northern lands." On a voyage that would add him to the list of famous explorers, Cartier was to search for gold and other riches, spices, and a passage to Asia.

Cartier sailed on April 20, 1534, with two ships and 61 men, and arrived 20 days later. He explored the west coast of Newfoundland, discovered Prince Edward Island and sailed through the Gulf of St. Lawrence, past Anticosti Island.

Second Voyage

Upon returning to France, King Francis was impressed with Cartier’s report of what he had seen, so he sent the explorer back the following year, in May, with three ships and 110 men. Two Indigenous peoples Cartier had captured previously now served as guides, and he and his men navigated the St. Lawrence, as far as Quebec, and established a base.

In September, Cartier sailed to what would become Montreal and was welcomed by the Iroquois who controlled the area, hearing from them that there were other rivers that led farther west, where gold, silver, copper and spices could be found. Before they could continue, though, the harsh winter blew in, rapids made the river impassable, and Cartier and his men managed to anger the Iroquois.

So Cartier waited until spring when the river was free of ice and captured some of the Iroquois chiefs before again returning to France. Because of his hasty escape, Cartier was only able to report to the king that untold riches lay farther west and that a great river, said to be about 2,000 miles long, possibly led to Asia.

Third Voyage

In May 1541, Cartier departed on his third voyage with five ships. He had by now abandoned the idea of finding a passage to the Orient and was sent to establish a permanent settlement along the St. Lawrence River on behalf of France. A group of colonists was a few months behind him this time.

Cartier set up camp again near Quebec, and they found an abundance of what they thought were gold and diamonds. In the spring, not waiting for the colonists to arrive, Cartier abandoned the base and sailed for France. En route, he stopped at Newfoundland, where he encountered the colonists, whose leader ordered Cartier back to Quebec. Cartier, however, had other plans; instead of heading to Quebec, he sneaked away during the night and returned to France.

There, his "gold" and "diamonds" were found to be worthless, and the colonists abandoned plans to found a settlement, returning to France after experiencing their first bitter winter. After these setbacks, France didn’t show any interest in these new lands for half a century, and Cartier’s career as a state-funded explorer came to an end. While credited with the exploration of the St. Lawrence region, Cartier's reputation has been tarnished by his dealings with the Iroquois and abandonment of the incoming colonists as he fled the New World.

Cartier died on September 1, 1557, in Saint-Malo, France.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jacques Cartier

- Birth Year: 1491

- Birth date: December 31, 1491

- Birth City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: French explorer Jacques Cartier is known chiefly for exploring the St. Lawrence River and giving Canada its name.

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1557

- Death date: September 1, 1557

- Death City: Saint-Malo, Brittany

- Death Country: France

- If the soil were as good as the harbors, it would be a blessing.

- [T]he land should not be called the New Land, being composed of stones and horrible rugged rocks; for along the whole of the north shore I did not see one cartload of earth and yet I landed in many places.

- Out of 110 that we were, not 10 were well enough to help the others, a thing pitiful to see.

- Today was our first day at sea. The weather was good, no clouds at the horizon and we are praying for a smooth sail.

- We set sail again trying to discover more wonders of this new world.

- Today I did something great for my country. We have taken over the land. Long live the King of France!

- I'm anxious to see what lies ahead. Every day we are getting deeper and deeper inside the continent, which increases my curiosity.

- Today I have completed my second voyage, which I can say had thought me a lot about how different things are in this world and how people start building up communities according to their common beliefs.

- The world is big and still hiding a lot.

- There arose such stormy and raging winds against us that we were constrained to come to the place again from whence we were come.

- I am inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

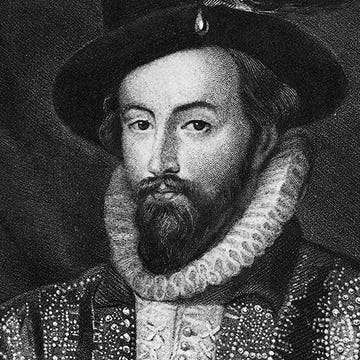

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Allaire, Bernard. "Jacques Cartier". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 July 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier. Accessed 06 June 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 July 2020, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier. Accessed 06 June 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Allaire, B. (2020). Jacques Cartier. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Allaire, Bernard. "Jacques Cartier." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited July 09, 2020.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 29, 2013; Last Edited July 09, 2020." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Jacques Cartier," by Bernard Allaire, Accessed June 06, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Jacques Cartier," by Bernard Allaire, Accessed June 06, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Jacques Cartier

Article by Bernard Allaire

Published Online August 29, 2013

Last Edited July 9, 2020

Jacques Cartier, navigator (born between 7 June and 23 December 1491 in Saint-Malo, France; died 1 September 1557 in Saint-Malo, France). From 1534 to 1542, Cartier led three maritime expeditions to the interior of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River . During these expeditions, he explored, but more importantly accurately mapped for the first time the interior of the river, from the Gulf to Montreal ( see also History of Cartography in Canada ). For this navigational prowess, Cartier is still considered by many as the founder of “Canada.” At the time, however, this term described only the region immediately surrounding Quebec . Cartier’s upstream navigation of the St. Lawrence River in the 16th century ultimately led to France occupying this part of North America.

Voyages to the Americas

Jacques Cartier’s early life is very poorly documented. He was likely employed in business and navigation from a young age. Like his countrymen, Cartier probably sailed along the coast of France, Newfoundland and South America (Brazil), first as a sailor and then as an officer. Following the annexation of Brittany to the kingdom of France, King François 1 chose Cartier to replace the explorer Giovanni da Verrazano . Verrazano had died on his last voyage.

First Voyage (1534)

Jacques Cartier’s orders for his first expedition were to search for a passage to the Pacific Ocean in the area around Newfoundland and possibly find precious metals. He left Saint-Malo on 20 April 1534 with two ships and 61 men. They reached the coast of Newfoundland 20 days later. During his journey, Cartier passed several sites known to European fishers. He renamed these places or noted them on his maps. After skirting the north shore of Newfoundland , Cartier and his ships entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence by the Strait of Belle Isle and travelled south, hugging the coast of the Magdalen Islands on 26 June. Three days later, they reached what are now the provinces of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick . He then navigated towards the west, crossing Chaleur Bay and reaching Gaspé , where he encountered Iroquoian lndigenous people from the region of Quebec . They had come to the area for their annual seal hunt. After planting a cross and engaging in some trading and negotiations, Cartier’s ships left on 25 July. Before leaving, Cartier abducted two of Iroquoian chief Donnacona’s sons. They returned to France by following the coast of Anticosti Island and re-crossing the Strait of Belle Isle.

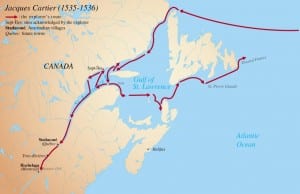

Second Voyage (1535-6)

The expedition of 1535 was more important than the first expedition. It included 110 people and three medium-sized ships. The ships were called the Grande Hermine (the Great Stoat), the Petite Hermine (the Lesser Stoat) and the Émérillon (the Merlin). The Émérillon had been adapted for river navigation. They left Brittany in mid-May 1535 and reached Newfoundland after a long, 50-day crossing. Following the itinerary from the previous year, they entered the Gulf , then travelled the “Canada River” (later named the St. Lawrence River ) upstream. One of chief Donnacona’s sons guided them to the village of Stadacona on the site of what is now the city of Quebec . Given the extent of their planned explorations, the French decided to spend the winter there and settled at the mouth of the St. Charles River. Against the advice of chief Donnacona, Jacques Cartier decided to continue sailing up the river towards Hochelaga , now the city of Montreal . Cartier reached Hochelaga on 2 October 1535. There he met other Iroquoian people, who tantalized Cartier with the prospect of a sea in the middle of the country. By the time Cartier returned to Stadacona (Quebec), relations with the Indigenous people there had deteriorated. Nevertheless, they helped the poorly organized French to survive scurvy thanks to a remedy made from evergreen trees ( see also Indigenous Peoples’ Medicine in Canada ). When spring came, the French decided to return to Europe. This time, Cartier abducted chief Donnacona himself, the two sons, and seven other Iroquoian people. The French never returned Donnacona and his people to North America. ( See also Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada. )

Third Voyage (1541-2)

The war in Europe led to a delay in returning to Canada. In addition, the plans for the voyage were changed. This expedition was to include close to 800 people and involve a major attempt to colonize the region. The explorations were left to Jacques Cartier, but the logistics and colonial management of the expedition were entrusted to Jean-François de La Rocque , sieur de Roberval. Roberval was a senior military officer who was responsible for recruitment, loading weapons onto the ships, and bringing on craftsmen and a number of prisoners. Just as the expedition was to begin, delays in the preparations and the vagaries of the war with Spain meant that only half the personnel (led by Cartier) were sent to Canada in May 1541 by Roberval. Roberval eventually came the following year. Cartier and his men settled the new colony several kilometres upstream from Quebec at the confluence of the Cap Rouge and St. Lawrence rivers. While the colonists and craftsmen built the forts, Cartier decided to sail toward Hochelaga . When he returned, a bloody battle had broken out with the Iroquoian people at Stadacona .

Return to France

In a state of relative siege during the winter, and not expecting the arrival of Jean-François de La Rocque , sieur de Roberval until spring, Jacques Cartier decided to abandon the colony at the end of May. He had filled a dozen barrels with what he believed were precious stones and metal. At a stop in St. John’s , Newfoundland, however, Cartier met Roberval’s fleet and was given the order to return to Cap Rouge. Refusing to obey, Cartier sailed toward France under the cover of darkness. The stones and metal that he brought back turned out to be worthless and Cartier was never reimbursed by the king for the money he had borrowed from the Breton merchants. After this misadventure, he returned to business. Cartier died about 15 years later at his estate at Limoilou near Saint-Malo. He kept his reputation as the first European to have explored and mapped this part of the Americas, which later became the French axis of power in North America.

- St Lawrence

Further Reading

Marcel Trudel, The Beginnings of New France, 1524-1663 (1973).

External Links

Watch the Heritage Minute about French explorer Jacques Cartier from Historica Canada. See also related online learning resources.

Exploring the Explorers: Jacques Cartier Teacher guide for multidisciplinary student investigations into the life of explorer Jacques Cartier and his role in Canadian history. From the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Indigenous languages in canada, enslavement of indigenous people in canada, indigenous perspectives education guide.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

Jacques Cartier Facts, Biography, Accomplishments, Voyages

Published: Jun 4, 2012 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

Jacques Cartier (December 31, 1491 – September 1, 1557) was the first French Explorer to explore the New World. He explored what is now Canada and set the stage for the great explorer and navigator Samuel de Champlain to begin colonization of Canada.

Cartier was the first European to discover and create a map of the St. Lawrence River. The St. Lawrence River would play an important role in the New World during the French and Indian War, the American Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the colonization of America.

Early Life of Jacques Cartier

First voyage, 1534, second voyage, 1535–1536, third voyage, 1541–1542, later life and death.

- Cartier was born in 1491 in Saint-Malo. During his early childhood, he would hear stories of the great Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and the exploits of the Spanish Conquistadors .

- His homeland, France, was relatively inactive in the exploits of the New World. Instead, it was embroiled in the European wars with the Holy Roman Empire, England, and Spain. Cartier grew and began to study navigation and, over time, became an excellent mariner.

- In a feudal society, talents were often overlooked and superseded by political standing. Cartier did not get the attention he deserved until he married Mary Catherine, who was a daughter in a wealthy and politically influential family.

- In 1534, Jacques Cartier was brought to the court of King Francis I. King Francis I ruled France during the reign of Charles V in the Holy Roman Empire and Henry VIII of England.

- He was a talented Monarch and ambitious for great treasure. 10 years prior to Cartier, he had asked Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the eastern coast of North America but had not formally commissioned him.

- Cartier set sail with a commission from King Francis I in 1534 with hopes of finding a pathway through the New World and into Asia.

- Jacques Cartier sailed across the ocean, landed around Newfoundland, and began exploring the area around the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River. While exploring, he came across two Indian tribes, the Mi'kmaq and the Iroquois. Initially, relations with the Iroquois were positive as he began to establish trade with them. However, Cartier then planted a large cross and claimed the land for the King of France.

- The Iroquois understood the implications and began to change their mood. In response, Cartier kidnapped two of the captain's sons. The Iroquois captain and Cartier agreed that the sons could be taken as long as they were returned with European goods to trade. Cartier then returned to his ships and began his voyage home. He believed that he had found the coast of Asia.

- After his return from his first voyage, Cartier received much praise from Francis I and was granted another voyage, which he left the next year. He left France on May 19 with three ships, 110 men, and the two natives he promised to return to the Iroquois captain.

- This time, when he arrived at the St. Lawrence River, he sailed up the river in what he believed to be a pathway into Asia. He did not reach Asia but instead came into contact with Chief Donnacona, who ruled from the Iroquois capital, Stadacona.

- Cartier continued up the St. Lawrence, believing that it was the Northwest passage to the east. He came across the Iroquois city of Hochelaga and was not able to go much further. The St. Lawrence waters became rapids and were too harsh for ships.

- His expedition left Cartier unable to return to France before the coming of winter. He stayed among the people of Hochelaga and then sailed back to Stadacona around mid-October. He most likely set up winter camp here. During his encampment, scurvy broke out among the Iroquois and soon infected the European explorers. The prognosis was dim until the Iroquois revealed a remedy for scurvy. Bark from a white spruce boiled in water would rid them of the disease.

- Cartier and his men used an entire white spruce to concoct the remedy. The remedy would work and would save the expedition from failure.

- Cartier left Canada for France in May of 1536. Chief Donnacona traveled to France with him to tell King Francis of the great treasures to be found. Jacques Cartier arrived in France on July 15, 1536. His second voyage had made him a wealthy and affluent man.

- Jacques Cartier's third voyage was a debacle. It began with King Francis commissioning Cartier to found a colony and then replacing Cartier with a friend of his, Huguenot explorer Roberval. Cartier was placed as Roberval's chief navigator. Cartier and Roberval left France in 1541.

- Upon reaching the St. Lawrence, Roverval waited for supplies and sent Cartier ahead to begin construction on the settlement. Cartier anchored at Stadacona and once again met with the Iroquois. While they greeted him with much happiness, Cartier did not like how many of them there were and chose to sail down the river a bit more to find a better spot to construct the settlement. He found the spot and began construction and named it Charlesbourg-Royal.

- After fortifying the settlement, Cartier set out to search for Saguenay. His search was again halted by winter, and the rapids of the Ottawa River forced him to return to Charlesbourg-Royal. Upon his arrival, he found out that the Iroquois Indians were no longer friendly to the Europeans. They attacked the settlement and left 35 of the settlers dead. Jacques Cartier believed that he had insufficient manpower to defend the settlement and search for the Saguenay Kingdom. He also believed that he and his men had found diamonds and gold and had stashed them on two ships.

- Cartier set sail for France in June of 1542. Along the way, he located Roberval and his ships along the coast of Newfoundland. Roberval insisted that Cartier stay and continue with him to the settlement and to help find the Kingdom of Saguenay, and Carter pretended to oblige. Cartier waited, and when the perfect night came, he and his ships full of diamonds and gold left Roberval and returned to France. Roberval continued to Charlesbourg-Royal but abandoned it 2 years later after harsh winters, disease, and the hostile Iroquois Indians.

- Upon returning to France, Cartier would learn that the diamonds he believed to have found were nothing more than mineral deposits. This ended the career of Jacques Cartier.

- Jacques Cartier retired to Sain-Malo, where he served as an interpreter of the Portuguese language. A typhus epidemic broke out in 1557 and claimed the life of the great explorer. Cartier died 15 years after his last voyage to the New World.

- While Cartier's missions did not establish a permanent settlement in Canada, it laid the foundation for Samuel de Champlain.

Biography of Jacques Cartier, Early Explorer of Canada

Rischgitz / Stringer/ Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Canadian Government

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.A., Political Science, Carleton University

Jacques Cartier (December 31, 1491–September 1, 1557) was a French navigator sent by French King Francis I to the New World to find gold and diamonds and a new route to Asia. Cartier explored what became known as Newfoundland, the Magdalen Islands, Prince Edward Island, and the Gaspé Peninsula, and was the first explorer to map the St. Lawrence River. He claimed what is now Canada for France.

Fast Facts: Jacques Cartier

- Known For : French explorer who gave Canada its name

- Born : Dec. 31, 1491 in Saint-Malo, Brittany, France

- Died : Sept. 1, 1557 in Saint-Malo

- Spouse : Marie-Catherine des Granches

Jacques Cartier was born on Dec. 31, 1491, in Saint-Malo, a historic French port on the coast of the English Channel. Cartier began to sail as a young man and earned a reputation as a highly-skilled navigator, a talent that would come in handy during his voyages across the Atlantic Ocean.

He apparently made at least one voyage to the New World, exploring Brazil , before he led his three major North American voyages. These voyages—all to the St. Lawrence region of what is now Canada—came in 1534, 1535–1536, and 1541–1542.

First Voyage

In 1534 King Francis I of France decided to send an expedition to explore the so-called "northern lands" of the New World. Francis was hoping the expedition would find precious metals, jewels, spices, and a passage to Asia. Cartier was selected for the commission.

With two ships and 61 crewmen, Cartier arrived off the barren shores of Newfoundland just 20 days after setting sail. He wrote, "I am rather inclined to believe that this is the land God gave to Cain."

The expedition entered what is today known as the Gulf of St. Lawrence by the Strait of Belle Isle, went south along the Magdalen Islands, and reached what are now the provinces of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. Going north to the Gaspé peninsula, he met several hundred Iroquois from their village of Stadacona (now Quebec City), who were there to fish and hunt for seals. He planted a cross on the peninsula to claim the area for France, although he told Chief Donnacona it was just a landmark.

The expedition captured two of Chief Donnacona's sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, to take along as prisoners. They went through the strait separating Anticosti Island from the north shore but did not discover the St. Lawrence River before returning to France.

Second Voyage

Cartier set out on a larger expedition the next year, with 110 men and three ships adapted for river navigation. Donnacona's sons had told Cartier about the St. Lawrence River and the “Kingdom of the Saguenay” in an effort, no doubt, to get a trip home, and those became the objectives of the second voyage. The two former captives served as guides for this expedition.

After a long sea crossing, the ships entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence and then went up the "Canada River," later named the St. Lawrence River. Guided to Stadacona, the expedition decided to spend the winter there. But before winter set in, they traveled up the river to Hochelaga, the site of present-day Montreal. (The name "Montreal" comes from Mount Royal, a nearby mountain Cartier named for the King of France.)

Returning to Stadacona, they faced deteriorating relations with the natives and a severe winter. Nearly a quarter of the crew died of scurvy, although Domagaya saved many men with a remedy made from evergreen bark and twigs. Tensions grew by spring, however, and the French feared being attacked. They seized 12 hostages, including Donnacona, Domagaya, and Taignoagny, and fled for home.

Third Voyage

Because of his hasty escape, Cartier could only report to the king that untold riches lay farther west and that a great river, said to be 2,000 miles long, possibly led to Asia. These and other reports, including some from the hostages, were so encouraging that King Francis decided on a huge colonizing expedition. He put military officer Jean-François de la Rocque, Sieur de Roberval, in charge of the colonization plans, although the actual exploration was left to Cartier.

War in Europe and the massive logistics for the colonization effort, including the difficulties of recruiting, slowed Roberval. Cartier, with 1,500 men, arrived in Canada a year ahead of him. His party settled at the bottom of the cliffs of Cap-Rouge, where they built forts. Cartier started a second trip to Hochelaga, but he turned back when he found that the route past the Lachine Rapids was too difficult.

On his return, he found the colony under siege from the Stadacona natives. After a difficult winter, Cartier gathered drums filled with what he thought were gold, diamonds, and metal and started to sail for home. But his ships met Roberval's fleet with the colonists, who had just arrived in what is now St. John's, Newfoundland .

Roberval ordered Cartier and his men to return to Cap-Rouge, but Cartier ignored the order and sailed for France with his cargo. When he arrived in France, he found that the load was really iron pyrite—also known as fool's gold—and quartz. Roberval's settlement efforts also failed. He and the colonists returned to France after experiencing one bitter winter.

Death and Legacy

While he was credited with exploring the St. Lawrence region, Cartier's reputation was tarnished by his harsh dealings with the Iroquois and by his abandoning the incoming colonists as he fled the New World. He returned to Saint-Malo but got no new commissions from the king. He died there on Sept. 1, 1557.

Despite his failures, Jacques Cartier is credited as the first European explorer to chart the St. Lawrence River and to explore the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He also discovered Prince Edward Island and built a fort at Stadacona, where Quebec City stands today. And, in addition to providing the name for a mountain that gave birth to "Montreal," he gave Canada its name when he misunderstood or misused the Iroquois word for village, "kanata," as the name of a much broader area.

- " Jacques Cartier Biography ." Biography.com.

- " Jacques Cartier ." History.com.

- " Jacques Cartier: French Explorer ." Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- What Was the Age of Exploration?

- The Story of How Canada Got Its Name

- Capital Cities of Canada

- A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

- Biography of Robert Cavelier de la Salle, French Explorer

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Queen Elizabeth's Royal Visits to Canada

- Captain James Cook

- French and Indian War: Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

- Facts About Canada's Geography, History, and Politics

- Amerigo Vespucci, Italian Explorer and Cartographer

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- The Florida Expeditions of Ponce de Leon

- Prince Edward Island Facts

- American Revolution: Arnold Expedition

- What Was the Canadian Confederation?

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- The Voyages of Jacques Cartier

In this Book

- With an introduction by Ramsay Cook

- Published by: University of Toronto Press

Jacques Cartier's voyages of 1534, 1535, and 1541constitute the first record of European impressions of the St Lawrence region of northeastern North American and its peoples. The Voyages are rich in details about almost every aspect of the region's environment and the people who inhabited it.

In addition to Cartier's Voyages , a slightly amended version of H.P. Biggar's 1924 text, the volume includes a series of letters relating to Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval, who was in command of cartier on the last voyage. Many of these letters appear for the first time in English.

Ramsay Cook's introduction, 'Donnacona Discovers Europe,' rereads the documents in the light of recent scholarship as well as from contemporary perspectives in order to understand better the viewpoints of Cartier and the native people with whom he came into contact.

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright Page

- pp. vii-viii

- Donnacona Discovers Europe: Rereading Jacques Cartier's Voyages

- The Voyages

- Cartier's First Voyage, 1534

- Cartier's Second Voyage, 1535-1536

- Cartier's Third Voyage, 1541

- Roberval's Voyage, 1542-1543

- pp. 107-113

- Documents relating to Jacques Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval

- 1 Grant of Money to Cartier for His First Voyage

- 2 Commission from Admiral Chabot to Cartier

- 3 Choice of Vessels for the Second Voyage

- pp. 119-120

- 4 Payment of Three Thousand Livres to Cartier for His Second Voyage

- 5 Roll of the Crews for Cartier's Second Voyage

- pp. 122-124

- 6 Order from King Francis the First for the Payment to Cartier of Fifty Crowns

- 7 List of Men and Effects for Canada

- pp. 126-129

- 8 Letter from Lagarto to John the Third, King of Portugal

- pp. 130-133

- 9 The Baptism of the Savages from Canada

- 10 Cartier's Commission for His Third Voyage

- pp. 135-138

- 11 Letters Patent from the Duke of Brittany Empowering Cartier to Take Prisoners from the Gaols

- pp. 139-140

- 12 The Emperor to the Cardinal of Toledo

- pp. 141-142

- 13 An Order from King Francis to Inquire into the Hindrances Placed before Cartier

- 14 Roberval's Commission

- pp. 144-151

- 15 Secret Report on Cartier's Expedition

- pp. 152-155

- 16 Cartier's Will

- pp. 156-158

- 17 Examination of Newfoundland Sailors regarding Cartier

- pp. 159-168

- 18 Cartier Takes Part in a 'Noise'

- pp. 169-170

- 19 Statement of Cartier's Account

- pp. 171-176

- 20 Death of Cartier

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

Have Fun With History

10 Jacques Cartier Accomplishments and Achievements

Jacques Cartier was a French explorer born around 1491. He is renowned for his voyages to Canada during the 16th century.

Cartier embarked on three expeditions between 1534 and 1542, exploring and mapping various parts of the Canadian Atlantic coast, including the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, and the St. Lawrence River.

He discovered the entrance to the St. Lawrence River, which would become a vital waterway for European exploration and trade in North America.

Cartier claimed the region of Canada for France, establishing French claims in North America and laying the foundation for French colonization and the subsequent establishment of New France.

His interactions with Indigenous Peoples provided valuable insights into their culture and way of life. Cartier’s reports of valuable resources, including furs, fish, and minerals, sparked interest in European trade and settlement in the region.

He made contributions to navigation, documented the natural history of the areas he explored, and left a lasting legacy in Canadian history. Jacques Cartier’s explorations and discoveries played a significant role in the European colonization and shaping of North America.

Accomplishments of Jacques Cartier

1. explored and mapped canada.

Jacques Cartier embarked on three voyages to Canada between 1534 and 1542. During these expeditions, he ventured into uncharted territories along the Canadian Atlantic coast.

Also Read: Historical Facts About Canada

He meticulously explored and mapped areas such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the island of Newfoundland, and the surrounding regions. Cartier’s exploration efforts significantly expanded European knowledge of the North American continent.

2. Discovered the St. Lawrence River

During his first voyage in 1534, Cartier made a monumental discovery when he found the entrance to the St. Lawrence River. This river served as a crucial waterway for future explorers and became the gateway for French colonization and trade in the region.

Cartier’s exploration of the St. Lawrence River opened up new possibilities for further navigation, exploration, and settlement along its shores.

3. Established French claims in North America

One of the most significant accomplishments of Jacques Cartier was his role in establishing French claims in North America. During his voyages, Cartier claimed the region of Canada (specifically the area around present-day Quebec) for France.

Also Read: Accomplishments of Samuel de Champlain

This act laid the foundation for French colonization and the subsequent establishment of New France, a significant French colonial presence in North America. Cartier’s expeditions paved the way for further French exploration, trade, and settlement in the region, shaping the course of Canadian history.

4. Interacted with Indigenous Peoples

Throughout his voyages, Jacques Cartier had numerous interactions with the Indigenous Peoples of the areas he explored, particularly the Iroquoian-speaking communities of the St. Lawrence region.

These encounters provided Cartier with insights into the culture, customs, and way of life of the native populations. He documented his interactions, learning about their social structures, religious beliefs, and economic practices.

These meetings with Indigenous Peoples contributed to the growing understanding of the diversity of human societies in the Americas and their impact on European perceptions of the New World.

5. Introduced the word “Canada” to Europe

During his second voyage in 1535, Cartier encountered the Iroquoian village of Stadacona, which he referred to as “Canada” in his reports. The name “Canada” derived from the Iroquoian word “Kanata,” meaning village or settlement.

Cartier extended the term “Canada” to refer to the entire region he explored. His use of the word introduced it to Europe and played a crucial role in popularizing the name for the region that would eventually become the country of Canada.

6. Discovered valuable resources

During his expeditions, Jacques Cartier discovered and reported on various valuable resources in the Canadian region. He encountered a thriving fur trade, particularly with the Indigenous Peoples, who prized beaver pelts for their fur.

Cartier’s reports of the abundance of furs in the region sparked interest among European traders and established a foundation for the fur trade that would become a significant economic activity in North America.

Additionally, Cartier observed the abundance of fish, particularly cod, in the waters off Newfoundland. This knowledge contributed to the development of lucrative fishing industries in the area.

Cartier’s explorations also revealed the presence of minerals such as iron ore and copper, indicating potential wealth in the region and stimulating further interest in its resources.

7. Advanced navigational techniques

Jacques Cartier’s voyages contributed to advancements in navigational techniques. He employed various navigational instruments such as the astrolabe and quadrant to determine latitude and longitude, enabling more accurate mapping and exploration.

Cartier’s use of these instruments, along with his meticulous recording of navigational details, improved the understanding of navigation in the challenging waters of the North Atlantic and provided valuable knowledge for future explorers.

8. Promoted further exploration

Cartier’s reports and descriptions of his voyages generated significant interest in further exploration of the North American continent. His accounts of the lands he discovered, the resources he encountered, and the potential for trade and colonization sparked the curiosity of European powers.

Cartier’s expeditions, particularly his exploration of the St. Lawrence River, served as a catalyst for subsequent expeditions by other explorers, including Samuel de Champlain, who founded Quebec City in 1608.

9. Documented natural history

During his voyages, Jacques Cartier took a keen interest in documenting the natural history of the areas he explored. He made detailed observations of the flora, fauna, and ecosystems he encountered.

Cartier’s records and drawings provided valuable insights into the biodiversity of North America, including descriptions of plants, animals, and geographical features. His documentation contributed to expanding knowledge of the New World’s natural history and laid the groundwork for future scientific investigations and studies.

10. Left a lasting legacy in Canadian history

Jacques Cartier’s explorations and achievements left a lasting legacy in Canadian history. His voyages played a pivotal role in establishing French claims to North America, leading to the colonization and eventual formation of New France.

The French presence in Canada, influenced by Cartier’s explorations, had a profound impact on the culture, language, and political landscape of the country. Today, Cartier is recognized as one of the key figures in the early European exploration of Canada and is celebrated as a significant figure in Canadian history.

Second Voyage of Jaques Cartier

Jacques Cartier's second voyage to the New World commenced on May 19, 1535, a little more than a year after his return from his initial expedition. This time, Cartier commanded a flotilla of three ships—the Grande Hermine, the Petite Hermine, and the Émérillon—with a crew totaling around 110 men. His main objective remained the same: to find a westward route to Asia that would allow France to participate in the lucrative spice trade.

Setting sail from St. Malo, France, Cartier and his fleet made their way across the Atlantic Ocean, guided by two Iroquois sons of Chief Donnacona, Domagaya and Taignoagny, who had returned from France for this expedition. Arriving in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cartier followed the St. Lawrence River, a waterway he hoped would serve as a route to Asia. Instead, the river led him deep into the North American continent.

In early September, the expedition reached what is now Quebec City. Cartier then continued to venture upstream and arrived at a native village named Stadacona, near present-day Quebec City. He also made his way to another settlement called Hochelaga, situated at the site of modern-day Montreal. Here, he scaled a hill and named it Mont Royal, providing the inspiration for the city's eventual name.

Despite the warm initial reception from the native people, relations soon deteriorated, particularly with Chief Donnacona. With the harsh winter closing in, Cartier decided to winter at Stadacona. His crew suffered from scurvy, a disease they were unprepared for, and many men died. It was only through the knowledge of the native people, who showed them how to prepare a concoction from a local tree (likely the white cedar), that they managed to combat the illness.

By spring, Cartier realized that the St. Lawrence River was not the passage to Asia he had hoped for. Frustrated and low on supplies, he decided to return to France. Before leaving, Cartier kidnapped Chief Donnacona and several other natives to take back to France as proof of his discoveries. These actions further strained relations between the French and the indigenous populations.

Cartier returned to France in July 1536, his ships laden with what he believed to be gold and diamonds but were later discovered to be iron pyrite and quartz, respectively. Despite failing to find a route to Asia or the wealth he had anticipated, Cartier's voyages laid the foundation for future French claims in North America and contributed to geographical knowledge of the continent.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to "About government"

Language selection

- Français

The second voyage (1535-1536)

Cartier-brébeuf national historic site.

The following year, his ships filled with provisions for a 15-month expedition, Jacques Cartier explored both shores of the St. Lawrence River beginning from Anticosti Island. He was aided in this endeavour by the two Amerindians he had captured during the previous voyage. On September 7, 1535, he dropped anchor on the north side of Île d'Orléans. Domagaya and Taignoagny, who had become Cartier's guides in these territories, now returned to their homeland and introduced Cartier to the people of Stadacona. The explorer offered the Amerindians presents. This meeting of the two peoples was a cause for numerous celebrations.

Not long after arriving at Île d'Orléans, Jacques Cartier decided to explore the surrounding country for the purpose of finding a suitable location in which to shelter his vessels. He discovered a natural haven at the junction of the Lairet and Saint-Charles Rivers. It was a particularly advantageous setting, as it prevented the ships from being dragged away by tides, and the surrounding hillsides provided shelter from wind. The explorer declared himself satisfied with the location, which was to become the present-day Cartier-Brébeuf National Historic Site, and had his two largest ships, the Grande Hermine and the Petite Hermine, cast anchor for the winter.

Cartier then began laying plans for travel upriver to Hochelaga (present-day Montréal). Domagaya and Taignoagny attempted to dissuade him from this course of action, and then flatly refused to accompany him. They thereby hoped to reserve the benefits of trading with the Europeans for the inhabitants of Stadacona alone. Despite the ruses and threats of the Amerindians, Cartier set out on his expedition aboard the Émérillion on September 19. The inhabitants of Hochelaga provided him a warm welcome. As no interpreters were to be had, the Europeans and the Amerindians had to use sign language. The French navigator developed the impression that there was gold beyond the Lachine rapids. He thus vowed to continue his exploration at some future date.

Jacques Cartier

Why should we read and study cartier, “first encounter with native peoples in chaleur bay” from the first voyage of jacques cartier (july 1534).

- Analysis of “First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay”

Questions and Considerations for Reflection

Strategies for teachers, further reading.

Few explorers have acquired the distinction given to Jacques Cartier, the first explorer to claim what is now Canada for King Francis I of France and giving Canada its name. Born in Saint-Malo, a port-town in Brittany, France, in 1491, Cartier was an accomplished mariner before being commissioned by King Francis I in 1534 to cross the Atlantic Ocean in search of a passage to Asia and lands rich in valuable resources. Over the next eight years he led three expeditions to North America: in 1534, 1535–36, and 1541–42. Cartier never found a passage through the North American continent and, though he returned from his final voyage with what he believed were diamonds and gold, the cargo turned out to be worthless. Unable to establish a permanent colony in North America, he returned to France a failure. If the resources he had brought back to France had been worthless, however, his written accounts of his voyages have since proven invaluable. Published in three volumes, Cartier’s Voyages provide one of the earliest and most comprehensive records of European impressions of North America and its people. Written with a prejudice that might offend modern sensibilities, Cartier’s accounts reveal as much about sixteenth-century European attitudes and beliefs as they do about the First Nations people he encountered on his voyages. Nevertheless, his cartography, his meticulous descriptions of the land and people, and his attempts to establish relations with the First Nations people who inhabited the territory he visited mean that his Voyages are indispensable to anyone studying the history of New Brunswick and Canada.

On most author pages we direct readers to the appropriate entry in The New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia . Though a Cartier entry is in production, it is not yet finalized. Please check the NBLE periodically for updates.

- Though not the earliest description of Canada, Jacques Cartier’s memoirs of his voyages in 1534, 1535, and 1541 are the earliest records of European exploration of the Atlantic region and the area around the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Moreover, they provide the earliest known European description of present-day New Brunswick and the First Nations people who first inhabited the territory.

Cartier’s Voyages reveal a great deal about European attitudes and beliefs, especially with regard to the indigenous peoples Cartier encountered during his expeditions to North America. As such, they provide insight into the way in which European colonizers exploited and manipulated the indigenous peoples they encountered, establishing a history of behaviour that continues today.

Literature & Analysis

And while we were in the said berth we went on Monday, the 6th, after having heard mass, with one of our boats to explore a cape and point of land which lay at seven or eight leagues to the west of us, for to see how the said land trended; and we being a half-league from said point perceived two bands of savages in boats, which crossed from their shore to the other, where they were more than forty or fifty boats, and of which one of the said companies of boats arrived at the said point, from which a great number of people leaped and landed on shore, who made a great noise, and made many signs that we should go ashore, showing us skins upon sticks. And because we had but a single boat we would not go there, and rowed toward the other band, which was on the sea. And they, seeing that we fled, equipped two of their largest boats for to come after us, with which were banded five others of those who came from the sea, and they came until near our said boat, dancing and making many signs of wanting our friendship, saying to us in their language: “Napou tou daman asurtar,” and other words which we did not understand.

Because we had, as was said, only one of our boats, we would not trust to their signs, and we made signs to them that they should withdraw, which they would not do, but rowed with such great fury that they surrounded our said boat with their seven boats. And because for the sign that we made them they would not retire, we fired two volleys over them, and then they fell to to return to the said point, and made a marvelously great noise, after which they began to return toward us as before; and they being very near our said boat, we let go at them two fusees, which passed among them, which astonished them greatly, so much so that they betook themselves to flight in very great haste and came after us no more. [. . .]

Thursday, the 8th of the said month, because the wind was not good to go out with our ships, we fitted out our said boats in order to go and explore the [Chaleur] bay [. . .] [M]aking our way along the coast we saw the said savages on the shore of a pond and low lands where they were making many fires and smokes. We went to the said place and found that it had a sea entrance, which entered into said pond, and we put our said boats to one side of the said entrance. The said savages passed over with one of their boats and fetched us some pieces of seals all cooked, which they put upon pieces of wood and then withdrew, making us a sign that they gave them to us. We sent two men ashore with hatchets and knives, paternosters, and other goods, for which they showed great joy, and forthwith passed in a crowd with their boats to the side where we were, with skins and whatever they had in order to get of our goods. And they were in number, of men, women, and children as well, more than three hundred [. . .]. I judge more than otherwise that these people would be easy to convert to our holy faith. They call a hatchet in their tongue Cochy and a knife Bacan. We named the said bay, Bay Chaleur.

The 24th day of the said month [July] we caused a cross to be made thirty feet in height, which was made before a number of them on the point at the entrance of the said harbor, on the cross-bar of which we put a shield embossed with three fleurs-de-lis, and above where it was an inscription graven in wood in letters of large form, “VIVE LE ROY DE FRANCE” [“LONG LIVE THE KING OF FRANCE”]. And this cross we planted on the said point before them, the which they beheld us make and plant; and after it was raised in the air we all fell on our knees, with hands joined, while adoring it before them, and made them signs, looking up and showing them the sky, that by it was our redemption, for which they showed much admiration, turning and beholding the cross.

We, being returned to our ships, saw the captain clothed with an old black bear’s skin, in a boat with three of his sons and his brother, who approached not so close alongside as was customary, and made to us a long harangue, showing us the said cross and making the sign of the cross with two fingers, and then showed us the country all about us, as if he had wished to say that all the country was his, and that we should not plant the said cross without his leave. And after he had ended his said harangue, we showed him a hatchet, feigning to deliver it to him for his skin, to which he harkened, and little by little drew near the side of our ship, thinking to have the said hatchet. And one of our crew, being in our boat, put his hand on his said boat, and suddenly he with two or three of them leaped into their boat, and made them come into our ship, at which they were greatly astonished. And they, having entered, were assured by the captain that they should not have any harm, by showing them great signs of love, and he made them drink and eat and make great cheer, and then showed them by signs that the said cross had been planted for to make a mark and beacon in order to enter into the harbor, and that we would return very soon and would bring them iron wares and other things, and that we wished to carry two of his sons with us, and then they should return again to the said harbor. And we rigged his said two sons with two shirts, and with liveries and red caps, and to each one his chain of copper for the neck, with which they were greatly contented and delivered their old duds to those who were returning. And then we gave to the three that we sent back, to each one his hatchet and two knives, for which they showed great joy; and they, being returned to the land, told the news to the others.

Analysis of “First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay” from The First Voyage of Jacques Cartier (July 1534)

Cartier set out on his first voyage on 20 April 1534 and arrived near present-day Newfoundland twenty days later. Beginning on 10 May, he explored the coasts of what is now the Atlantic region and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. His initial impression of the land he encountered was an unfavourable one. “I deem rather than otherwise,” wrote Cartier in June of that year, “that it is the land that God gave to Cain” (86). By July, Cartier’s descriptions of the land had become much more positive, but he was no closer to discovering a strait through which he could reach the Pacific.

On 3 July, Cartier approached Chaleur Bay and named the southernmost cape at the entrance to the bay (what is now Point Miscou) “Cap d’Espérance” or “Cape Hope” for the hope that the bay would finally reveal the long-sought passage to the Pacific. It was while exploring Chaleur Bay that Cartier first interacted with the First Nations of New Brunswick. Though they were not the first native peoples he had encountered – he had observed natives on the coasts of what are now Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island – those he met at Chaleur Bay were the first with whom he would interact.

The first of the two passages describes Cartier’s interactions with the natives he met at Chaleur Bay, most likely Mi’kmaq peoples of New Brunswick, on 6–8 July. What becomes immediately clear to the reader of Cartier’s account are his prejudicial beliefs about the native peoples he encounters. Like most Europeans of his time, Cartier considered the Indigenous peoples of North America to be barbaric and subhuman, a belief reflected in his use of the term “savage.” Indeed, the passage demonstrates that even when shown hospitality and goodwill, Cartier remained suspicious and distrustful of the Aboriginals he met. Sailing west into Chaleur Bay, Cartier’s ship is approached by “forty or fifty” canoe loads of Mi’kmaq men “making signs of wanting friendship” and trade. Cartier, however, “would not trust their signs” and when the natives pursue his boats he scares them away with gunfire. This initial exchange, in which Cartier’s response is clearly disproportionate to the behaviour of the native peoples, establishes early on the unequal relationship between the French explorers and the Indigenous peoples of present-day Canada.

This uneven relationship is reinforced when Cartier and his men return to Chaleur Bay two days later. Now willing to engage in trade with the natives, Cartier approaches a group of “more than three hundred.” Once again, the French are shown hospitality by the native peoples who offer them seal meat. Cartier, in turn, sends two men ashore with various tools and cooking utensils. Significant here are Cartier’s motives. Trade with the native peoples appears more of a pretense than a goal. In fact, Cartier appears already to be looking toward the future, determining that “these people would be easy to convert to our holy faith.” As French Catholics, Cartier and his men were not only explorers, but missionaries too whose goal it was to convert Indigenous peoples to Catholicism. Cartier is thus more concerned with how the French can transform and manipulate the native peoples than he is with developing a balanced relationship. The passage ends with Cartier giving the bay a new name, Baie-des-Chaleurs (translated as Bay of Heat), disregarding any claim to the land on the part of the indigenous peoples who had lived there for more than a thousand years.

The second passage, which is dated 24 July 1534, describes Cartier’s contact with the Laurentian Iroquois from Stadacona at present-day Gaspé. In this passage, Cartier performs many of the same gestures and actions he carried out when interacting with the Mi’kmaq in the Bay of Chaleur two weeks earlier, but the motivation of Cartier and his men is made much more explicit. In this passage, the conversion of the Iroquoian peoples to both Catholicism and to the French Empire becomes an obvious incentive, while the acquisition of Iroquoian land leads Cartier to bribe and eventually kidnap the chief’s sons.

Raising a cross to which is attached a shield inscribed with fleurs-de-lis and a sign reading “VIVE LE ROY DE FRANCE” (“LONG LIVE THE KING OF FRANCE”), Cartier and his men enact a show of worship for the natives, kneeling and praying to the cross. While Cartier interprets the show to have inspired “admiration” in the on-looking Iroquois, their chief, Donnacona, is not impressed and approaches Cartier’s ship after the ceremony with his sons. Pretending he will trade a hatchet for the chief’s bear skin, Cartier draws Donnacona nearer his ship. Cartier’s men then capture Donnacona, bringing him and his sons aboard where they give them food and drink. With promises of “iron wares and other goods,” Cartier then explains why the cross had been raised and tells the chief that he would like to take two of his sons back to France. Dressing the sons in clothes and jewellery and giving the other men hatchets and knives, he sends everyone but the sons away.

To many readers today, the passage is a shocking one. With seeming detachment and casualness, Cartier describes the deception and bribery he and his men used to infiltrate Iroquoian land, claim that land for France, and kidnap the sons of Donnacona, the Iroquois chief. The encounter would prove to be a fateful one, for Donnacona’s sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, would be forced to guide the French during their explorations. Cartier would visit the village from which the Iroquois came, Stadacona, on his second and third voyages, and Samuel de Champlain would later found l’Habitation, the start of the settlement of Quebec, on the abandoned site of Stadacona in 1608.

► Though there is a general agreement among history scholars that Cartier authored the accounts that constitute the Voyages , no original manuscript exists for any of the extant texts. As a result, the authenticity of Cartier’s Voyages and the accuracy of the translations we have today are suspect. Furthermore, Cartier’s accounts are subjective, skewed by the prejudice with which he regarded First Nations, and driven by a desire to accomplish the goals he set out to achieve: find a passage to Asia, possibly discover precious minerals and metals along the way, and convert Indigenous peoples to Catholicism and the ways of Empire. The accounts, however, remain foundational to early Canadian history and, as writers like Alfred G. Bailey and John Ralston Saul observe, are deeply imbedded in the Canadian cultural memory. Having said that, Cartier’s records are valuable looking glasses in which we see the emergence of our own colonial attitudes and values. And key questions arise. What do the importance and ambiguity surrounding the Voyages reveal about the writing of history? Whose authority does history reflect? What do Cartier’s accounts reveal about the relationship between history and fiction – are the two as distinct as we are led to believe?

► When Cartier returned to France from his final voyage in 1542, he was considered a failure. He hadn’t found a passage to Asia, the minerals and rocks he had thought were diamonds and jewels turned out to be worthless, and his attempt to establish a permanent settlement in North America had been unsuccessful. In subsequent years, however, Cartier’s reputation was revived and he was often – though mistakenly – considered the founder of New France. Consider the ways in which Cartier’s voyages have been commemorated in Canada during the twentieth century. Two notable examples are commemorative stamps (found here and here ) and the Heritage Minutes commercial aired throughout the 1990s on Canadian television stations. To what extent do these commemorative gestures attempt to legitimize and even glorify European colonization of North America, reflecting a belief, not unlike Cartier’s own, that Cartier and his men had a right to claim and settle the land occupied by Canada’s First Nations?

► From the exercise above, readers might also benefit from considering the ways that colonial dramas between settler and First Nations communities play out today. What are the similarities, for example, between Cartier’s interventions in 1534–36 and the presumably benign commemorative events today? Whose community and what power structures benefit from such commemorations? Also, what are the similarities being replayed in both communities today (2017) over the Energy East pipeline project and shale gas development? In more profound ways, what are societies to do with inconvenient and unsettling aspects of their history? And, as importantly, what allowances are we willing to give to historical figures whose ideas and actions reflected the values of their own societies? Are we prepared to be judged as harshly for enacting our own social values as we now judge Cartier for enacting his? These are difficult questions that challenge us to examine our own views about history and knowledge.

Strategy 1: Heritage Minute Critique (“First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay”)

After students have had the opportunity to read and discuss the passage, show the Jacques Cartier Heritage Minute (link available above, or search YouTube). Presented below are multiple ideas for classroom activities; each may stand on its own, or several could be combined.

Historica Canada, the creator of these minutes, also releases accompanying lesson plans . In its Jacques Cartier plan is the statement, “Misunderstanding between people is often just a problem of language.” Ask students to apply this statement to both the Heritage Minute and the Cartier passage. If everyone spoke the same language, would the misunderstandings in the Heritage Minute disappear? Can students find evidence in the Cartier passage that the misunderstandings/conflict go much deeper than language?

In small groups, have students choose three words to describe the Cartier that is the author of “First Encounter,” and three words to describe the Cartier that appears in the Heritage Minute. Compile a master list on the board. Do any words appear on both lists? If students were to portray Cartier, how would reading the primary source affect their portrayal?

Ask students to speak about other Heritage Minutes they have seen. What kinds of Canadian stories does Historica Canada promote? What kinds of stories are not told? For a lighthearted prompt, you might show one of the many Heritage Minute parodies that tackle the “not told” question, such as those that appeared on the Rick Mercer Report . Why might Historica consider “Kanata” a good subject for a Heritage Minute, as opposed to, say, Cartier’s first encounter with Mi’kmaq people?

Individually or in small groups, have students storyboard a script for a Heritage Minute based on some portion of “First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay.” Storyboards might include narration and/or dialogue. Students could consider how music and film techniques could be used to establish a tone appropriate for their subject matter and message.

Key Stage Curriculum Outcomes:

Reading and Viewing: Examine how texts work to reveal and produce ideologies, identities, and positions

Reading and Viewing: Note the relationship of specific elements of a particular text to elements of other texts

Writing and Representing: Demonstrate an understanding of the ways in which the construction of texts can create, enhance, and control meaning

Strategy 2: Place Names (“First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay”)

Despite the presence of an existing population, visitor Cartier declares, “We named the said bay, Bay Chaleur.” That name continues to this day. Have students consider the origin of place names (towns, rivers, etc.) in their local area. Maps would be helpful, as would reference to William B. Hamilton’s Place Names of Atlantic Canada (1996). Are students aware of any other or past names for these places? If there are multiple names for a place, how might one name come to be the dominant one that appears on maps? To explore further, students could investigate a passionate naming dispute, such as the 2015 battle over Denali/Mount McKinley in the U.S. Why is the power to name, and have your name widely accepted, so important to people?

- Speaking and Listening: Articulate, advocate, and justify positions on an issue or text in a convincing manner, showing an understanding of a range of viewpoints

Strategy 3: Presentism (“First Encounter with Native Peoples in Chaleur Bay”)

When reading the literature of the past, particularly controversial material such as Cartier’s account, it is tempting to interpret it in terms of modern-day values. Lynn Hunt (2002) writes about the disadvantages of such an approach: “Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation. Interpreting the past in terms of present concerns usually leads us to find ourselves morally superior; the Greeks had slavery, even David Hume was a racist, and European women endorsed imperial ventures. Our forbears constantly fail to measure up to our present-day standards.” Ask students to consider how presentism affected their reading of Cartier’s words. Can students think of any benefits to a presentist approach to literature? Does rereading with a different approach yield any new insights about Cartier’s worldview?

Reading and Viewing: Articulate their own processes and strategies in exploring, interpreting, and reflecting on sophisticated texts and tasks

Cook, Ramsay, ed. Introduction [“Donnacona Discovers Europe: Rereading Jacques Cartier’s Voyages”]. The Voyages of Jacques Cartier . By Jacques Cartier. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1993.

Gordon, Allan. Hero and the Historians: Historiography and the Uses of Jacques Cartier . Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2010.

Hamilton, William B. Place Names of Atlantic Canada . Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1996.

Hunt, Lynn. “Against Presentism.” Perspectives 40.5 (2002): 7-9.

Trigger, Bruce. Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s “Heroic Age” Reconsidered . Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1986.

Welton, Michael R. “First Encounters: New Worlds and Old Maps.” The Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education 21.2 (March 2009): 67-79.

The translated and edited memoirs of Jacques Cartier from which the above excerpts have been taken are in the Canadian public domain. As such, they are no longer protected by copyright in Canada. However, they may still be under copyright in some countries. Readers outside Canada must comply with the respective copyright laws of the country in which they live.

The two Cartier passages above were taken from pp. 103-107 and pp. 112-113 of Cartier, Jacques. A Memoir of Jacques Cartier: Sieur de Limoilou, His Voyages to the St. Lawrence, a Bibliography and a Facsimile of the Manuscript of 1534 . Ed. and trans. James P. Baxter. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1906. 24 June 2015 < https://archive.org/stream/amemoirjacquesc00alfogoog#page/n17/mode/2up >.

All contents except for poetry and fiction copyright © Tony Tremblay, James W. Johnson, and Alexandra Cogswell.

The Ages of Exploration

Jacques cartier interactive map, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Jacques Cartier’s voyages across the Atlantic Ocean brought him to northern North America which he claimed for France and named “Canada, and explored much of the St. Lawrence River

Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer’s voyage.

How to Use the Map

- Click on either the map icons or on the location name in the expanded column to view more information about that place or event

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Jacques Cartier and his four voyages to Canada : an essay, with historical, explanatory and philological notes

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Page 61-62 is damaged, illustration and blank tissue pages are not numbered and there are lots of notes in pencil throughout.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Download options.

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on December 11, 2009

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

On The Site

The voyages of jacques cartier.

Preparing your PDF for download...

There was a problem with your download, please contact the server administrator.

- Recommend to Library

Download Flyer

Edited by Ramsay Cook

Ebook - ePub

Ebook - PDF

Published: April 1993

Product Details

Imprint: University of Toronto Press

Series: Series: Heritage

Page Count: 177 Pages

Dimensions: 6.00 x 8.90

World Rights

177 Pages , 6.00 x 8.90 x 0.50 in

ISBN: 9780802060006

Shipping Location

Shipping Updated

This item has rights restrictions. We are unable to ship/sell this item to your location.

There are no exam or desk copies available for this title. If you have any questions, please email us at [email protected].

- Description

Jacques Cartier's voyages of 1534, 1535, and 1541constitute the first record of European impressions of the St Lawrence region of northeastern North American and its peoples. The Voyages are rich in details about almost every aspect of the region's environment and the people who inhabited it.

In addition to Cartier's Voyages , a slightly amended version of H.P. Biggar's 1924 text, the volume includes a series of letters relating to Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval, who was in command of cartier on the last voyage. Many of these letters appear for the first time in English.