- Global Locations -

Headquarters

Future Market Insights, Inc.

Christiana Corporate, 200 Continental Drive, Suite 401, Newark, Delaware - 19713, United States

616 Corporate Way, Suite 2-9018, Valley Cottage, NY 10989, United States

Future Market Insights

1602-6 Jumeirah Bay X2 Tower, Plot No: JLT-PH2-X2A, Jumeirah Lakes Towers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

3rd Floor, 207 Regent Street, W1B 3HH London United Kingdom

Asia Pacific

IndiaLand Global Tech Park, Unit UG-1, Behind Grand HighStreet, Phase 1, Hinjawadi, MH, Pune – 411057, India

- Consumer Product

- Food & Beverage

- Chemicals and Materials

- Travel & Tourism

- Process Automation

- Industrial Automation

- Services & Utilities

- Testing Equipment

- Thought Leadership

- Upcoming Reports

- Published Reports

- Contact FMI

Italy Tourism Industry

Italy Tourism Industry Analysis by Domestic and International Tourism Type from 2024 to 2034

La Dolce Vita 2.0, Reinventing the Tourism Experience for the Modern Traveler in Italy

- Report Preview

- Request Methodology

Italy Tourism Industry Analysis from 2024 to 2034

The travel industry in Italy stands as a beacon of cultural richness, historical grandeur, and natural splendor, captivating millions of visitors from around the globe each year. According to an updated research report from Future Market Insights, the Italy tourism industry is poised to reach a valuation of US$ 27.3 billion by 2024.

Further forecasts suggest a subsequent increase to US$ 51.2 billion by 2034, illustrating a consistent growth trajectory. This projected expansion showcases a CAGR of 6.5% over the forecast period, indicating sustained and steady growth within the industry.

Renowned for its iconic landmarks, world class cuisine, and breathtaking landscapes, Italy offers an unparalleled tapestry of experiences that cater to desires of the travelers. From the ancient ruins of Rome to the Renaissance treasures of Florence, from the romantic canals of Venice to the sun kissed shores of the Amalfi Coast, Italy beckons travelers with its irresistible charm and timeless allure.

The industry in Italy is a vibrant ecosystem encompassing a diverse array of offerings, including guided tours, luxury accommodations, adventure experiences, culinary adventures, and cultural immersion programs.

Italy, with its rich cultural heritage, artistic legacy, as well as gastronomic delights, appeals to a wide spectrum of travelers, from history enthusiasts and art aficionados to foodies and nature lovers. Italy, being one of the top tourist destinations in the world, continues to innovate and evolve, embracing sustainable tourism practices, digital technologies, and experiential travel trends.

Don't pay for what you don't need

Customize your report by selecting specific countries or regions and save 30%!

Industry Motivators Enhancing the Growth

- Italian cuisine is renowned around the globe, and culinary tourism is a significant driver of travel to Italy.

- Preservation efforts and cultural events in Italy continue to attract tourists interested in history, art, and architecture.

- High end travelers seeking luxury hotels, yacht charters, as well as personalized services contribute to the growth of luxury tourism.

- The diverse landscapes, from the Alps in the north to the Mediterranean coastline in the south, offer opportunities for outdoor activities.

2019 to 2023 Historical Analysis vs. 2024 to 2034 Industry Forecast Projections

The scope for tourism in Italy was substantial, advancing at a 4.8% CAGR between 2019 and 2023. The industry is achieving heights to grow at a moderate CAGR of 6.5% over the forecast period 2024 to 2034.

The industry witnessed a steady growth during the historical period, owing to cultural heritage, culinary tourism, and luxury travel. Italy implemented various measures during the historical period, including travel restrictions, and health and safety protocols, to support the tourism.

Adoption of digital transformation acceleration such as online booking platforms, and virtual tours changed consumer preferences and safety concerns. Pent up demand for travel and leisure activities will lead to a surge in tourism, as travelers seek to explore new destinations, and fulfil postponed travel plans.

Continued digital innovation will enhance the visitor experience, with advancements in augmented reality, as well as artificial intelligence.

Offering diverse and authentic experiences, including niche tourism offerings will attract a broader range of travelers seeking unique and meaningful experiences. Italy will diversify its tourism offerings to appeal to emerging industry segments, such as wellness tourism, adventure travel, and experiential tourism.

Principal Consultant

Talk to Analyst

Find your sweet spots for generating winning opportunities in this market.

Major Contributors of Italy Tourism Industry

- Digital transformation helps reach a global audience and attract tech savvy travelers.

- Infrastructure development improve accessibility and connectivity within Italy and from international industries.

- Special Interest Tourism attracts a broader range of travelers with specific interests.

- Government initiatives and policies support the growth of the tourism industry, including marketing campaigns.

Factors Hampering Italy Tourism Industry

- Overcrowding and overtourism could detract from the visitor experience and deter future travelers.

- Infrastructure limitations may hinder accessibility to and within tourist destinations in Italy, limiting the growth potential.

- Competition from rival destinations may divert tourist flows away from Italy, challenging the industry share of the country.

- Cultural preservation challenges diminish the appeal of the country to discerning travelers.

Get the data you need at a Fraction of the cost

Personalize your report by choosing insights you need and save 40%!

Comparative View of Adjacent Industries

Future Market Insights has compared two other industries, India outbound tourism market , and travel agency services market . Film tourism drives interest in destinations showcased on screen, augmenting the tourism in those areas.

Increase of experiential travel will create memorable and meaningful travel experiences. Travel agencies provide expertise, logistical support, and customized solutions to meet the diverse needs of travelers.

Italy Tourism Industry:

India Outbound Tourism Market:

Travel Agency Services Market:

Region-wise Insights

Fashion and design will boost the industry growth in north italy.

Milan is renowned as a global fashion capital, hosting prestigious fashion events such as Milan Fashion Week. The luxury boutiques, designer showrooms, and fashion museums appeal to fashion enthusiasts and luxury travelers.

North Italy is home to iconic cultural landmarks and historic cities such as Milan, Venice, Florence, and Verona. The rich cultural heritage, including Renaissance art, Gothic architecture, and UNESCO World Heritage sites, attracts tourists interested in history, art, and architecture.

Rural and Agritourism Will Augment the Demand in Central Italy

The picturesque countryside of Central Italy offers opportunities for rural and agritourism experiences. Visitors can participate in agricultural activities, taste local produce, and immerse themselves in rural life and traditions.

Central Italy is home to UNESCO World Heritage sites, which preserve centuries of history and architectural splendor. Visitors can explore iconic landmarks immerse themselves in the rich cultural legacy of the region.

Natural Beauty Will Create New Avenues for the Industry in South Italy

South Italy offers diverse natural landscapes, including rolling hills, vineyards, olive groves, and rugged coastlines. Outdoor activities such as hiking, cycling, and sailing appeal to nature enthusiasts and adventure travelers seeking to explore the scenic beauty of the region.

South Italy is home to famous wine regions known for producing high quality wines such as Aglianico, Nero d'Avola, and Primitivo. Wine tours, vineyard visits, and wine tastings offer immersive experiences for wine enthusiasts visiting the region.

Scenic Beauty to Stimulate the Growth Prospects in Islands Italy

Islands Italy, including Sicily, Sardinia, Capri, and the Aeolian Islands, offer stunning natural landscapes characterized by pristine beaches. The scenic beauty of islands attracts sun seekers, nature lovers, and photographers from around the world.

Islands Italy offers unique attractions and experiences not found on the mainland. The natural wonders and iconic landmarks draw tourists seeking unforgettable experiences.

Category-wise Insights

The below table highlights how international segment is leading the industry in terms of tourist type, and will account for a share of 44.6% in 2024. Based on age group, the 36 to 45 years segment is gaining heights and will to account for a share of 30.6% in 2024.

International Segment Witnesses High Demand for Tourism in Italy

Based on tourist type, the international segment will dominate the Italy tourism industry. Italy offers a wide range of luxury and boutique accommodations, including historic palaces, boutique hotels, and luxury resorts.

International tourists seeking upscale experiences, personalized service, and exclusive amenities contribute to the growth of luxury tourism in Italy.

Italy is home to historic cities and art capitals that showcase centuries of artistic and architectural achievements. Cities like Rome, Florence, Venice, and Milan are hubs of culture, fashion, and design, attracting tourists interested in exploring museums, galleries, and landmarks associated with renowned artists and architects.

36 to 45 Years Segment to Hold High Demand for Tourism in Italy

In terms of age group, the 36 to 45 years segment will dominate the Italy tourism industry. Many individuals in this age group may have young families or be in the midst of family planning.

Italy offers family friendly destinations and activities, such as historic cities, cultural attractions, amusement parks, and beach resorts, making it an appealing choice for family vacations and multi-generational travel.

Individuals in the 36 to 45 years age group typically have established careers, stable incomes, and greater financial capacity to afford leisure travel. They are more likely to prioritize travel experiences and allocate discretionary income towards vacations, including trips to Italy.

Competitive Landscape

The Italy tourism Industry is dynamic and diverse, shaped by a combination of factors including geographical diversity, cultural heritage, infrastructure development, industry segmentation, and evolving consumer preferences.

Company Portfolio

- Alma Italia specializes in providing customized travel experiences and tours across Italy. Their portfolio includes curated itineraries that showcase the rich cultural heritage, culinary delights, and scenic beauty of Italy.

- Exodus Travels offers a diverse range of adventure and cultural tours in Italy. Their itineraries are designed for adventurous travelers looking to discover Italy off the beaten path.

Key Coverage in the Italy Tourism Industry Report

- Italian travel destinations

- Cultural tourism in Italy

- Italy vacation experiences

- Best places to visit in Italy

- Italy tourism statistics

- Wine and culinary tours Italy

Report Scope

Segmentation analysis of the italy tourism industry, by visit purpose:.

- Business and Professional

- Leisure, Recreation and Holidays

- Religious Travel

By Demographic:

By tourist type:.

- International

By Tour Type:

- Youth Groups

- Single Tourists

By Tourism Type:

- Religious Tourism

- Cultural/Heritage Tourism

- Medical Tourism

- North Italy

- Central Italy

- South Italy

- Islands Italy

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the anticipated value of the italy tourism industry in 2024.

The Italy tourism industry is projected to reach a valuation of US$ 27.3 billion in 2024.

What is the expected CAGR for the Italy Tourism Industry until 2034?

The Italy tourism industry is set to expand by a CAGR of 6.5% through 2034.

How much valuation is projected for the Italy Tourism Industry in 2034?

The Italy tourism industry is forecast to reach US$ 51.2 billion by 2034.

Which is the leading tourist type in the Italy Tourism Industry?

International segment is set to be the top performing tourist type, which will exhibit a share of 44.6% in 2024.

Which is the dominant age group in the Italy Tourism Industry domain?

36 to 45 years segment is preferred, and will account for a share of 30.6% in 2024

Table of Content

List of tables, list of charts.

Recommendations

Travel and Tourism

India Outbound Tourism Market

Published : March 2024

Travel Agency Services Market

Published : June 2023

Italy Casino Tourism Market

Published : October 2022

Italy Culinary Tourism Market

Published : July 2022

Explore Travel and Tourism Insights

Talk To Analyst

Your personal details are safe with us. Privacy Policy*

- Talk To Analyst -

This report can be customized as per your unique requirement

- Get Free Brochure -

Request a free brochure packed with everything you need to know.

- Customize Now -

I need Country Specific Scope ( -30% )

I am searching for Specific Info.

- Download Report Brochure -

You will receive an email from our Business Development Manager. Please be sure to check your SPAM/JUNK folder too.

Winter is here! Check out the winter wonderlands at these 5 amazing winter destinations in Montana

- Travel Destinations

How Much Of Italy’s Economy Is Dependent On Tourism

Published: December 12, 2023

Modified: December 28, 2023

by Kalina Sauceda

- Plan Your Trip

- Travel Guide

Introduction

Italy, known for its rich history, stunning landscapes, and vibrant culture, has long been a top tourist destination. From the ancient ruins of Rome to the picturesque canals of Venice, this country offers a diverse range of attractions that draw millions of visitors each year. But have you ever wondered how much of Italy’s economy is dependent on tourism?

In this article, we will delve into the fascinating world of Italy’s tourism industry and explore its significance to the country’s economy. We will examine the factors that contribute to Italy’s heavy reliance on tourism, the impact it has on different sectors, and the challenges associated with this dependence. Finally, we will discuss potential measures to diversify Italy’s economy and reduce its reliance on tourism.

Italy’s tourism sector plays a crucial role in the country’s overall economic landscape. With its world-renowned monuments, UNESCO World Heritage sites, and rich cultural heritage, Italy has consistently been one of the most-visited countries in the world. In 2019 alone, Italy attracted more than 94 million international tourists, generating an estimated €41 billion in revenue.

The significance of tourism to Italy’s economy cannot be overstated. It accounts for a substantial portion of the country’s GDP and employment. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, travel and tourism directly contributed 13% to Italy’s GDP in 2019. Furthermore, the sector employs approximately 4.4 million people, representing around 16% of the total employment in the country.

Italy’s natural and cultural attractions serve as a magnet for international tourists, driving the growth of the tourism industry. The historical cities, such as Rome, Florence, and Venice, attract history enthusiasts and art lovers, while the beautiful coastal regions like the Amalfi Coast and Cinque Terre entice sun-seeking vacationers. Additionally, Italy’s reputation for excellent cuisine, fashion, and luxury goods adds to its allure as a premier tourist destination.

However, while Italy’s tourism industry has undoubtedly brought significant economic benefits, it also presents potential challenges and risks. The overreliance on tourism leaves the country vulnerable to external shocks, such as global economic downturns, political instability, natural disasters, or pandemics, as demonstrated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

In the following sections, we will delve deeper into Italy’s tourism industry, examining the key factors contributing to its dependence on tourism and the far-reaching consequences it has on the Italian economy. Join us as we explore the multifaceted relationship between Italy and its booming tourism sector.

Overview of Italy’s tourism industry

Italy’s tourism industry is one of the largest and most dynamic in the world. The country offers a wealth of attractions, including historical landmarks, UNESCO World Heritage sites, stunning coastlines, and picturesque countryside. From the iconic Colosseum in Rome to the romantic canals of Venice, there is something for every type of traveler.

Italy’s tourism infrastructure is extensive, catering to the needs of millions of visitors each year. The country boasts a wide range of accommodation options, from luxurious hotels and resorts to budget-friendly hostels and bed and breakfasts. Additionally, transportation within Italy is well-developed, with an extensive network of trains, buses, and domestic flights, making it convenient for tourists to explore different regions.

The tourism industry in Italy is supported by a strong cultural heritage and a rich history, which dates back to ancient times. The country is home to countless archaeological sites, including Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Roman Forum, offering visitors a glimpse into the past. Furthermore, Italy is renowned for its world-class museums, such as the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and the Vatican Museums in Rome, housing priceless works of art.

The natural beauty of Italy is also a major draw for tourists. The country is famous for its stunning coastlines, such as the Amalfi Coast and the Italian Riviera, which offer breathtaking views and idyllic beach towns. Inland, visitors can explore the picturesque countryside of Tuscany, known for its rolling hills, vineyards, and charming villages.

Italy’s cuisine is revered worldwide, and food tourism is another significant aspect of the country’s tourism industry. Italian cuisine is diverse and regionally distinct, with each area offering its own specialties. From Neapolitan pizza to Tuscan pasta and Sicilian cannoli, the culinary delights of Italy are a highlight for many visitors.

In recent years, Italy has also seen a rise in niche tourism segments, such as wine tourism, fashion tourism, and eco-tourism. Wine enthusiasts flock to regions like Tuscany and Piedmont to sample renowned Italian wines, while fashion lovers flock to Milan, the fashion capital of Italy. Eco-tourism is also on the rise, with visitors seeking eco-friendly accommodations and exploring Italy’s national parks and protected areas.

Overall, Italy’s tourism industry is thriving, attracting millions of visitors from around the globe. The combination of historical sites, cultural heritage, natural beauty, and culinary excellence make Italy a top choice for travelers seeking a unique and enriching experience.

Importance of tourism to Italy’s economy

Tourism is a vital component of Italy’s economy, playing a significant role in driving economic growth, creating jobs, and generating revenue. The sector’s impact is felt across various industries and regions, making it a critical pillar of the Italian economy.

The contribution of tourism to Italy’s gross domestic product (GDP) is substantial. In 2019, the direct contribution of travel and tourism accounted for approximately 5.2% of Italy’s GDP, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council. When considering both direct and indirect impacts, the total contribution rises to around 13%.

Tourism also plays a crucial role in employment generation. The sector provides millions of jobs directly and indirectly, supporting livelihoods in various sectors such as hospitality, transportation, retail, and entertainment. In 2019, the travel and tourism industry employed around 4.4 million people, representing approximately 16% of the total employment in Italy.

The revenue generated from tourism activities contributes significantly to Italy’s balance of payments, as international visitors spend money on accommodation, transportation, food, shopping, and entertainment. In 2019, total international visitor spending reached €41 billion, making tourism one of the leading sources of foreign exchange earnings for the country.

Furthermore, tourism encourages regional development and stimulates economic growth in less economically developed areas of Italy. The presence of popular tourist destinations in regions like Tuscany, Veneto, and Campania attracts investments in infrastructure, accommodation, and services, creating employment opportunities and boosting local businesses.

Italy’s cultural heritage and historical sites are a major draw for tourists, contributing significantly to the country’s economy. The maintenance and preservation of these sites require ongoing investment, and tourism revenue plays a crucial role in financing these efforts. Additionally, revenue generated from entrance fees to museums, archaeological sites, and cultural events directly contribute to the conservation and restoration of Italy’s cultural treasures.

Moreover, the tourism industry generates a multiplier effect, impacting various sectors and supporting related businesses. Accommodation providers, restaurants, souvenir shops, transportation services, tour operators, and other tourism-related businesses all benefit from the influx of tourists. The interdependence between these sectors creates a comprehensive tourism ecosystem that drives economic activity and creates a ripple effect through the supply chain.

Overall, tourism is of utmost importance to Italy’s economy. It not only drives economic growth, but also promotes cultural preservation, regional development, and job creation. However, the overreliance on tourism also presents certain challenges and risks, as we will explore in the following sections.

Factors contributing to Italy’s dependence on tourism

Several factors contribute to Italy’s heavy reliance on tourism as a significant driver of its economy. These factors have shaped the country’s economic landscape and made it highly dependent on the tourism industry.

Historical and Cultural Significance: Italy’s rich history and cultural heritage are major attractions for tourists. The country is home to numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites, ancient ruins, and iconic landmarks that draw visitors from around the world. The historical cities of Rome, Florence, and Venice, with their architectural marvels and artistic treasures, remain perennially popular. The preservation and promotion of these historical and cultural sites have fueled the growth of Italy’s tourism industry.

Geographical Diversity: Italy’s diverse geography is another contributing factor to its dependence on tourism. From the breathtaking coastlines of the Amalfi Coast and the Italian Riviera to the picturesque countryside of Tuscany and the stunning lakes in the north, Italy offers a variety of landscapes that appeal to different types of travelers. The natural beauty of these regions, along with their outdoor activities, such as hiking, sailing, and wine tours, attracts tourists looking for unique experiences.

World-Famous Cuisine: Italian cuisine is celebrated globally, and the country’s gastronomic offerings are a major attraction for tourists. From pizza and pasta to gelato and espresso, Italian culinary traditions are deeply ingrained in the country’s culture. Italy’s vibrant food scene, with its regional specialties and world-class wines, lures food enthusiasts and gourmet travelers, contributing to the growth of food tourism in the country.

Art and Fashion: Italy’s reputation as a hub of art, fashion, and design has also played a significant role in its dependence on tourism. The country is renowned for its centuries-old art masterpieces, with museums like the Uffizi Gallery and the Vatican Museums housing invaluable works of art. Milan, as the fashion capital of Italy, attracts fashion-conscious travelers who visit to explore its boutiques, attend fashion shows, and immerse themselves in Italian style.

Proximity and Connectivity: Italy’s geographical location in the heart of Europe has made it easily accessible to travelers from all over the world. The country benefits from its well-connected transportation infrastructure, with international airports in major cities, extensive rail networks, and a comprehensive highway system. This connectivity has made it convenient for tourists to reach Italy and explore multiple destinations within the country, boosting visitor numbers and tourism revenue.

Government Support: The Italian government has recognized the economic significance of the tourism industry and has implemented policies to support its growth. Investments in infrastructure, promotion of cultural heritage, and development of tourist-friendly initiatives have contributed to Italy’s popularity as a tourist destination. The government’s commitment to preserving historical sites, improving tourism infrastructure, and facilitating visa procedures has further strengthened Italy’s position as a top choice for travelers.

While these factors have undoubtedly contributed to Italy’s dependence on tourism, it is essential to address the challenges associated with this heavy reliance. In the next section, we will explore the impact of tourism on different sectors of the Italian economy and the risks it poses.

Impact of tourism on different sectors of the Italian economy

The tourism industry in Italy has far-reaching effects on various sectors of the country’s economy, creating a significant impact on both direct and indirect beneficiaries. Let’s explore how tourism influences different sectors and contributes to their growth and development.

Hospitality and Accommodation: The hospitality sector is one of the primary beneficiaries of Italy’s booming tourism industry. Hotels, resorts, bed and breakfasts, and vacation rentals cater to the influx of tourists, providing them with a place to stay during their visit. The demand for accommodation drives investment in the construction and maintenance of hotels and accommodations, thereby creating job opportunities and supporting the local economy.

Food and Beverage: Italy’s renowned culinary culture plays a crucial role in attracting tourists. The food and beverage sector benefits from the increased visitor numbers, with tourists eager to indulge in authentic Italian cuisine. Restaurants, cafes, and street food vendors experience higher demand, leading to increased business opportunities and employment in the sector.

Retail and Shopping: Tourism contributes significantly to the retail sector in Italy. Tourists often seek out local crafts, souvenirs, and designer goods, boosting sales in shops and boutiques. Major shopping destinations such as Milan, renowned for its fashion scene, benefit from the influx of tourists who come to explore and purchase Italian-made products. This, in turn, stimulates economic activity and supports the retail sector.

Transportation: Italy’s well-developed transportation infrastructure caters to the needs of millions of tourists. The travel and tourism industry drive demand for domestic and international flights, train travel, rental cars, and public transportation. This sustained demand for transportation services leads to job creation and revenue generation in the transportation sector, benefiting airlines, railway companies, taxi operators, and other transportation service providers.

Heritage and Culture: Italy’s rich cultural heritage is a major draw for tourists, and the preservation and promotion of historical sites and cultural events contribute to the economy. Revenue generated from entrance fees to museums, archaeological sites, and cultural festivals directly support the conservation and maintenance of Italy’s cultural treasures. Investments in the restoration and preservation of historical sites create employment opportunities in the heritage sector.

Tour Operators and Travel Agencies: The tour operator and travel agency sector play a vital role in facilitating tourism in Italy. These businesses provide travel packages, organize tours, and offer guidance and assistance to tourists. Through partnerships with hotels, transportation companies, and local tour guides, these entities generate employment and stimulate economic activity in the tourism ecosystem.

Entertainment and Events: Italy’s vibrant entertainment scene, including music concerts, theater performances, film festivals, and sporting events, also benefits from tourism. Visitors attend these events, leading to increased ticket sales, hotel bookings, and restaurant patronage. The cultural and entertainment sectors thrive due to the support and spending of tourists.

Small Businesses and Local Communities: Tourism is often a lifeline for small businesses and local communities. Family-owned restaurants, artisan workshops, wineries, and local producers all benefit from the influx of tourists who seek authentic experiences and products. These small businesses contribute to the unique and authentic character of Italy’s tourism offerings.

Overall, tourism’s impact extends beyond the direct benefits to various sectors of Italy’s economy. The growth and sustenance of these sectors contribute to job creation, economic development, and the preservation of Italy’s cultural heritage.

Challenges and risks associated with Italy’s reliance on tourism

While Italy’s tourism industry brings significant economic benefits, it also exposes the country to certain challenges and risks due to its heavy reliance on this sector. Understanding these challenges is crucial for managing and diversifying the Italian economy effectively. Let’s explore some of the key challenges and risks associated with Italy’s dependence on tourism.

Seasonality and Overcrowding: Italy’s tourism is highly seasonal, with peak periods occurring during the summer months. This seasonality creates challenges for businesses that rely heavily on tourist spending, as they experience fluctuations in revenue throughout the year. Additionally, popular destinations often face issues of overcrowding, leading to strain on infrastructure, long queues at attractions, and adverse impacts on the local environment and residents’ quality of life.

Economic Vulnerability: Italy’s overreliance on tourism makes its economy vulnerable to external shocks. Economic crises, political instability, natural disasters, or pandemics, as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, can severely impact the tourism industry and hamper the country’s overall economic stability. When a significant portion of the economy relies on tourism, any disruption can have a cascading effect across various sectors and lead to widespread consequences.

Environmental Sustainability: The environmental impact of tourism, particularly in popular destinations, poses significant challenges. Uncontrolled mass tourism can put a strain on natural resources, cause pollution, and contribute to the deterioration of fragile ecosystems. Italy’s iconic natural landscapes and protected areas need to be managed sustainably to ensure their preservation for future generations.

Rising Costs and Inflation: The influx of tourists often leads to a rise in prices, particularly in popular destinations. The increased demand for accommodation, transportation, and services can drive up prices, making it more expensive for both tourists and local residents. This can contribute to inflationary pressures and impact the affordability of tourism, potentially deterring travelers or redirecting them to alternative destinations.

Loss of Cultural Identity: Excessive tourism can gradually erode the unique cultural identity of local communities. As businesses cater to the demands of tourists, there is a risk of diminishing traditional practices, local crafts, and authentic experiences. Preserving the essence of local culture while simultaneously catering to tourist expectations is a delicate balance that should be carefully managed.

Dependency and Diversification: Reliance on a single industry for a significant portion of the economy limits diversification opportunities. Overdependence on tourism may hinder the development of other potential sectors and hinder efforts to create a more balanced and resilient economy. Diversification would reduce vulnerability to external shocks and create a more sustainable economic landscape.

Promotion of Sustainable Tourism: Implementing sustainable tourism practices is crucial for mitigating the risks associated with Italy’s dependence on tourism. This includes managing tourist flows, preserving cultural and environmental resources, promoting responsible travel behavior, and supporting local communities. By emphasizing sustainability, Italy can ensure a more resilient and inclusive tourism industry for the future.

Addressing these challenges and risks requires a comprehensive and strategic approach. Italy should focus on diversifying its economic base, investing in infrastructure, promoting off-peak and alternative destinations, and ensuring sustainability in tourism development. By doing so, Italy can reduce its vulnerability and create a more balanced and sustainable economy for the long term.

Measures to diversify Italy’s economy and reduce dependence on tourism

To reduce the country’s heavy reliance on tourism and create a more diversified and resilient economy, Italy can implement several measures. These measures aim to promote the development of other sectors and encourage economic growth that is less dependent on tourism. Let’s explore some strategies that can help diversify Italy’s economy:

Investing in Innovation and Technology: Italy can focus on fostering innovation and technological advancements in key sectors, such as manufacturing, information technology, and biotechnology. Encouraging research and development, providing support to startups and small businesses, and promoting collaboration between academia and industry can drive economic diversification and attract investment in high-tech industries.

Promoting Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs): Supporting the growth of SMEs is crucial for diversifying Italy’s economy. SMEs are the backbone of many sectors and can help stimulate regional development and job creation. By providing access to funding, improving business regulations, and offering mentorship and support programs, Italy can nurture entrepreneurship and foster a vibrant ecosystem of small businesses.

Strengthening the Manufacturing Sector: Italy has a long-standing tradition of excellence in manufacturing, particularly in sectors such as automotive, fashion, furniture, and machinery. Investing in advanced manufacturing technologies, promoting research and development, and fostering collaborations between manufacturers and academia can enhance Italy’s competitiveness in the global market and reduce its reliance on tourism-generated revenue.

Developing Knowledge-Based Industries: Italy can prioritize the development of knowledge-based industries, such as education, research, and creative sectors like design, architecture, and media. By investing in education and research institutions, attracting international talent, and providing support for creative industries, Italy can become a hub for knowledge-intensive activities, promoting economic diversification and long-term growth.

Expanding Export Opportunities: Italy can focus on expanding its export markets and diversifying its export portfolio. Encouraging Italian businesses to explore new markets and sectors, providing support in trade negotiations and export promotion, and fostering international business partnerships can help reduce dependency on domestic consumption and amplify the benefits of global trade.

Developing Rural and Agri-food Sectors: Italy’s agricultural heritage and quality food products offer opportunities for economic diversification. Prioritizing sustainable and high-value agricultural practices, investing in rural infrastructure, promoting organic and local food production, and supporting rural entrepreneurship can revitalize rural areas and create new avenues for economic growth beyond tourism.

Encouraging Cultural and Creative Tourism: Italy can leverage its rich cultural heritage and creative industries to attract a different type of tourist. By promoting cultural and creative tourism, which focuses on authentic experiences, local arts, crafts, and design, Italy can diversify its visitor base and attract tourists interested in cultural immersion and unique experiences that go beyond the traditional tourist hotspots.

Investing in Infrastructure and Connectivity: Enhancing Italy’s infrastructure, particularly in less-developed areas, can unlock new economic potentials. This includes improving transportation networks, expanding broadband internet access, and investing in renewable energy sources. It will create opportunities for businesses, stimulate investment, and reduce regional disparities, ultimately contributing to economic diversification.

Addressing Bureaucratic Barriers: Italy can streamline administrative processes and reduce bureaucratic obstacles to business growth. Simplifying regulations, improving transparency, and enhancing the ease of doing business can encourage investment and entrepreneurship, making Italy a more favorable destination for domestic and foreign businesses.

These measures should be implemented in a well-coordinated and long-term strategy to ensure sustainable economic diversification. By reducing dependence on tourism and fostering a more diverse economic landscape, Italy can build resilience, stimulate job creation, and navigate challenges more effectively, ultimately securing a prosperous future for the country.

Italy’s tourism industry is undeniably a vital pillar of its economy, contributing significantly to GDP, job creation, and foreign exchange earnings. The country’s rich cultural heritage, stunning landscapes, gastronomy, and renowned fashion industry have made it a top global tourist destination. However, while tourism has brought numerous benefits, it also exposes Italy to certain challenges and risks.

Italy’s heavy dependence on tourism makes its economy vulnerable to external shocks, such as economic crises, political instability, and pandemics. Additionally, the seasonality of tourism, overcrowding in popular destinations, rising costs, and potential loss of cultural identity all require careful management to ensure sustainable and responsible tourism practices.

To address these challenges, Italy must explore strategies to diversify its economy and reduce its reliance on tourism. Investing in innovation and technology, promoting SMEs, strengthening the manufacturing sector, and developing knowledge-based industries can spur economic growth and create new employment opportunities. Expanding export markets, supporting rural and agri-food sectors, encouraging cultural and creative tourism, and improving infrastructure and connectivity are additional avenues for economic diversification.

Italy should also emphasize sustainability and responsible tourism practices to preserve its cultural heritage, manage environmental impacts, and mitigate overcrowding in popular destinations. Promoting off-peak and alternative destinations, diversifying the tourism offering, and engaging local communities are key to creating a more inclusive and sustainable tourism industry.

In conclusion, while tourism remains a critical driver of Italy’s economy, the country must proactively pursue diversification strategies to reduce its vulnerability and build a more resilient economic foundation. By embracing innovation, fostering entrepreneurship, promoting sustainable practices, and investing in sectors beyond tourism, Italy can forge a path towards a prosperous and balanced future.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

No spam. We promise.

Italy Factsheet

Discover the total economic contribution that the Travel & Tourism sector brings to Italy and the world in this data-rich, two-page factsheet.

Discover the direct and total economic contribution that the Travel & Tourism sector brings to the Italy’s economies in this comprehensive report.

Discover the direct and total economic contribution that the Travel & Tourism sector brings to Italy in this comprehensive report.

Create an account for free or login to download

Over the next few weeks we will be releasing the newest Economic Impact Research factsheets for a wide range of economies and regions. If the factsheet you're interested in is not yet available, sign up to be notified via the form on this page .

Factsheet details

This factsheet highlights the importance of Travel & Tourism to Italy across many metrics, and features details such as:

- Contribution of the sector to overall GDP and employment

- Comparisons between 2019 and 2023

- Forecasts for 2024 and 2034

- International and domestic visitor spending

- Proportion of leisure vs business spending

- Top 5 inbound and outbound markets

This latest report reveals the importance of Travel & Tourism to the Italy in granular detail across many metrics. The report’s features include:

- Absolute and relative contributions of Travel & Tourism to GDP and employment, international and domestic spending

- Data on leisure and business spending, capital investment, government spending and outbound spending

- Charts comparing data across every year from 2014 to 2024

- Detailed data tables for the years 2018-2023 plus forecasts for 2024 and the decade to 2034

Purchase of this report also provides access to two supporting papers: Methodology and Data Sources and Estimation Techniques.

This latest report reveals the importance of Travel & Tourism to Italy in granular detail across many metrics. The report’s features include:

This factsheet highlights the importance of T&T to this city across many metrics, and features details such as:

- Contribution of the sector to overall GDP and employment in the city

- Comparisons between 2019, 2020 and 2021, plus 2022 forecast

- Proportion of the T&T at city level towards overall T&T contribution at a country level

- Top 5 inbound source markets

In collaboration with

Supported by.

Tourism in Italy

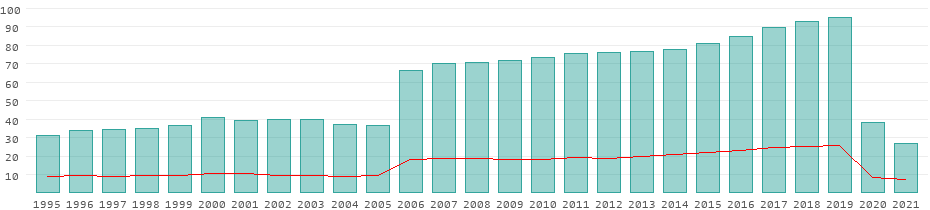

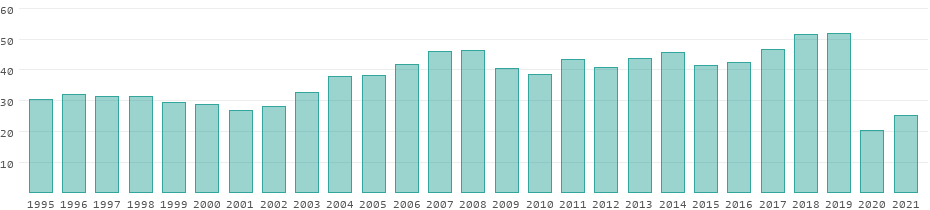

Art and culture as a tourist magnet, most popular travel destinations in italy, development of the tourism sector in italy from 1995 to 2021.

Revenues from tourism

All data for Italy in detail

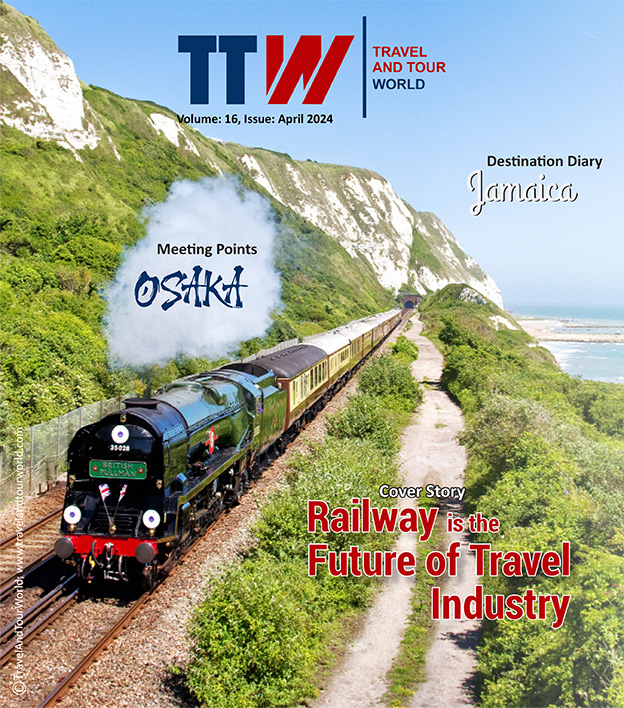

In 2023, Italy tourism is set to break all records

Friday, May 12, 2023 Favorite

In 2023, Italy tourism is set to break all records set before the pandemic, recent information showed the same, highlighting the revival of the sector in Europe ahead of pace in general.

From the beginning of the year, provisional data shows a major development in tourism compared to the same time a year before, from Italy’s National Statistics Institute, Sandro Cruciani told the Parliament.

Cruciani informed the Chamber of Deputies that in January and February, overnight stay tourists went up over 45 per cent compared to same time 2022 with a huge rise in international tourists than local travellers.

Cruciani said that if the information for the upcoming months verifies this trend, probably, there will be possibilities to see a complete revival, exceeding the pre-pandemic numbers as well.

The year 2019, the last full year before COVID was a record year for the tourism of Italy.

The forecast that this year will go beyond the levels of 2019 must push them to do more, intervening to help policies in terms of seasonal change and conquer the occurrence of over-tourism, said Daniela Santanche, Tourism Minister.

To the Italian economy, tourism stands for as a major element in terms of accounting for almost 13 per cent of its GDP in 2019.

The country that year was the third leading tourism market in Europe, just behind France and Spain.

Subscribe to our Newsletters

« Back to Page

Related Posts

- Alpine tunnel closures disrupt Italy’s rail traffic in northern routes

- Italy becomes second destination for 2023 beating France and Spain

- Italy announces special tourist trains and ‘cruise’ rail routes

- Tourists in Italy warn of pickpockets

- Met Office issues heatwave warning to holidaymakers in Spain, Italy or Greece

Tags: Italy Tourism , Tourism

Select Your Language

I want to receive travel news and trade event update from Travel And Tour World. I have read Travel And Tour World's Privacy Notice .

REGIONAL NEWS

Aberdeen International Airport Introduces Next Generation Security Checkpoint Sc

Sunday, April 28, 2024

ABTA Insights from Future Travel Coalition’s Travel Industry Survey to Sha

Britons Receive Urgent Safety Alert After Caribbean Shark Encounter at Tobago

Aviation Alert: Controversial FAA Amendment Threatens Airline Safety and Could D

Middle east.

Dubai Plans Massive $35 Billion Move of Busy International Airport Within 10 Yea

Qatar Airways and UNHCR to Continue Supporting Global Refugee Relief Efforts

IHG to Open “Zero-Energy” Hotel Indigo at Singapore Changi Airport, Featurin

Chennai Airport’s Commitment to Sustainability Shows with More Electric Ca

Upcoming shows.

Apr 29 April 29 - May 1 Global Restaurant Investment Forum (GRIF) Find out more » Apr 29 April 29 - May 1 FUTURE HOSPITALITY SUMMIT Find out more » May 01 May 1 - May 2 ABTA: Travel Law Seminar 2024 Find out more » May 01 May 1 - May 2 AHICE Asia Pacific 2024 Find out more »

Privacy Overview

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

- GDP share generated by travel and tourism in Italy 2019-2022

Contribution of travel and tourism to employment in Italy

What are the leading inbound tourism markets in italy, share of travel and tourism's total contribution to gdp in italy in 2019 and 2022.

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

2019 and 2022

figures are in constant 2022 prices and exchange rates as of March 2023

Other statistics on the topic Travel and tourism in Italy

- International tourist arrivals in Italy 2019-2022, by country

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Italy 2019-2022

Leisure Travel

- International tourist arrivals in Italy 2006-2022

Accommodation

- Leading international hotel chain brands in Italy 2022, by number of hotels

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Statistics on " Travel and tourism in Italy "

- Monthly tourism balance in Italy 2019-2024

- Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in Italy 2019-2022, by type

- Distribution of travel and tourism spending in Italy 2019-2022, by tourist type

- Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Italy 2019-2022

- Total number of international tourist arrivals in Italy 2015-2022

- Inbound business travelers in Italy 2015-2022

- Number of inbound tourist overnight stays in Italy 2014-2022, by travel reason

- Average length of stay of international tourists in Italy 2009-2022

- Inbound tourist expenditure in Italy 2007-2022

- Inbound tourist expenditure in Italy 2019-2022, by country

- Number of outbound tourists from Italy 2015-2022, by type

- Number of outbound trips from Italy 2019-2022, by destination

- Number of outbound tourist overnight stays from Italy 2015-2022

- Overnight stays for outbound trips from Italy 2019-2022, by destination

- Expenditure of Italian outbound tourists 2007-2022

- Expenditure of Italian outbound tourists 2019-2022, by destination

- Share of outbound holiday trips taken by Italians 2023, by purpose

- Share of outbound holiday trips taken by Italians 2022, by destination type

- Number of domestic trips in Italy 2014-2022

- Domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by accommodation type

- Overnight stays for domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by region of destination

- Domestic business trips in Italy 2015-2022

- Overnight stays during domestic business trips in Italy 2022, by destination

- Number of same-day domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by purpose

- Domestic tourism spending in Italy 2019-2022

- Number of hotel and non-hotel accommodation in Italy 2019-2022

- Number of hotels in Italy 2012-2022, by rating

- Number of hotels in Italy 2022, by region

- Revenue of the hotels industry in Italy 2019-2028

- Leading domestic hotel chain brands in Italy 2022, by number of hotels

- Number of bed and breakfasts in Italy 2010-2022

- Number of agritourism establishments in Italy 2012-2022

Other statistics that may interest you Travel and tourism in Italy

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP in Italy 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic GDP share generated by travel and tourism in Italy 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Monthly tourism balance in Italy 2019-2024

- Basic Statistic Distribution of travel and tourism expenditure in Italy 2019-2022, by type

- Basic Statistic Distribution of travel and tourism spending in Italy 2019-2022, by tourist type

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism's total contribution to employment in Italy 2019-2022

Inbound tourism

- Premium Statistic Total number of international tourist arrivals in Italy 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals in Italy 2006-2022

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals in Italy 2019-2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Inbound business travelers in Italy 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of inbound tourist overnight stays in Italy 2014-2022, by travel reason

- Premium Statistic Average length of stay of international tourists in Italy 2009-2022

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourist expenditure in Italy 2007-2022

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourist expenditure in Italy 2019-2022, by country

Outbound tourism

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound tourists from Italy 2015-2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound trips from Italy 2019-2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Number of outbound tourist overnight stays from Italy 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Overnight stays for outbound trips from Italy 2019-2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Expenditure of Italian outbound tourists 2007-2022

- Premium Statistic Expenditure of Italian outbound tourists 2019-2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Share of outbound holiday trips taken by Italians 2023, by purpose

- Premium Statistic Share of outbound holiday trips taken by Italians 2022, by destination type

Domestic tourism

- Premium Statistic Number of domestic trips in Italy 2014-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by accommodation type

- Premium Statistic Overnight stays for domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by region of destination

- Premium Statistic Domestic business trips in Italy 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Overnight stays during domestic business trips in Italy 2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Number of same-day domestic trips in Italy 2019-2022, by purpose

- Basic Statistic Domestic tourism spending in Italy 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of hotel and non-hotel accommodation in Italy 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of hotels in Italy 2012-2022, by rating

- Premium Statistic Number of hotels in Italy 2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Revenue of the hotels industry in Italy 2019-2028

- Premium Statistic Leading international hotel chain brands in Italy 2022, by number of hotels

- Premium Statistic Leading domestic hotel chain brands in Italy 2022, by number of hotels

- Premium Statistic Number of bed and breakfasts in Italy 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of agritourism establishments in Italy 2012-2022

Further related statistics

- Premium Statistic Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Premium Statistic Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

- Premium Statistic Italy: overnights of foreign tourists in Florence municipal area, Tuscany 2015-2016

- Premium Statistic Italy: hotels occupation rate in Florence 2016, by hotel rating

- Premium Statistic Sub-Saharan African countries in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2019

- Premium Statistic Italy: average tourists' length of stay Florence municipal area 2015-2016

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism of visitors from India to the Netherlands 2012-2017

- Premium Statistic Tourism consumption expenditure share Australia 2017 by visitor type

- Premium Statistic Italy: number of non-EU tourists in Florence YoY growth, by country 2016

- Premium Statistic Tourism industry employment in Greece 2010-2021

- Premium Statistic Overnight travelers in CAR Philippines 2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Overnight travelers in Central Visayas Philippines 2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Overnight travelers in Ilocos region Philippines 2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Overnight travelers in Eastern Visayas Philippines 2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Overnight travelers in Zamboanga Peninsula Philippines 2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Outbound tourism expenditure as a share of imports of services Thailand 2010-2021

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

- Leading countries in the MEA in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2018

- Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

- Italy: overnights of foreign tourists in Florence municipal area, Tuscany 2015-2016

- Italy: hotels occupation rate in Florence 2016, by hotel rating

- Sub-Saharan African countries in the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2019

- Italy: average tourists' length of stay Florence municipal area 2015-2016

- Inbound tourism of visitors from India to the Netherlands 2012-2017

- Tourism consumption expenditure share Australia 2017 by visitor type

- Italy: number of non-EU tourists in Florence YoY growth, by country 2016

- Tourism industry employment in Greece 2010-2021

- Overnight travelers in CAR Philippines 2022, by type

- Overnight travelers in Central Visayas Philippines 2022, by type

- Overnight travelers in Ilocos region Philippines 2022, by type

- Overnight travelers in Eastern Visayas Philippines 2022, by type

- Overnight travelers in Zamboanga Peninsula Philippines 2022, by type

- Outbound tourism expenditure as a share of imports of services Thailand 2010-2021

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The impact of COVID ‐19 on international tourism flows to Italy: Evidence from mobile phone data

Valerio della corte.

1 Directorate General for Economics, Statistics, and Research, Bank of Italy, Roma Italy

Claudio Doria

Giacomo oddo, associated data.

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, with the only exception of mobile phone data, as they were purchased from a private mobile phone company and cannot be made publicly available due to ownership restrictions. Data from the survey on international tourism in Italy (see Section Data annex in Appendix 1 for details) can be freely downloaded from the official website of the Bank of Italy in the following section: Home/Statistics/External transactions and positions/International tourism/Distribution of microdata.

This paper analyses the response to the COVID‐19 pandemic of inbound tourism to Italy looking at variation across countries and provinces. To this end, it uses weekly data on the number of foreign visitors in Italy from January 2019 until February 2021, as provided by a primary mobile telephony operator. We document a very robust negative relation at the province level between the local epidemic situation and the inflow of foreign travellers. Moreover, provinces with a historically higher share in art‐tourism, and those that used to be ‘hotel intensive’ were hit the most during the pandemic, while provinces with a more prevalent orientation to business tourism proved to be more resilient. Entry restrictions with varying degrees of strictness played a key role in explaining cross‐country patterns. After controlling for these restrictions, we observed that the number of travellers that could arrive by private means of transportation decreased proportionally less. Overall, this evidence emphasises that contagion risk considerations played a significant role in shaping international tourism patterns during the pandemic.

1. INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the early months of 2020 caused unprecedented disruption to tourism flows. 1 According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in 2020 international arrivals worldwide dropped by 74% (1 billion arrivals less than the previous year). Italy, a country for which the tourism industry is very important, 2 was among the first EU countries to be hit by the pandemic: between February and April 2020, positive cases rapidly rose from a few hundreds to over a hundred thousand, with a surge in the number of patients needing intensive care and in the number of deaths. 3

Fear of contagion and containment measures (including travel bans) resulted in tourism flows dropping to near‐zero levels since the end of March 2020. During the second quarter of 2020 conditions improved, allowing for the lifting of travel restrictions at the EU level in the summer. Italy, among other southern European countries (Spain, Portugal and Greece), benefited from the recovery of cross‐border tourism, although flows remained at around a half of pre‐pandemic levels. The second wave of the pandemic that hit Italy after the end of the summer halted again tourism flows. Overall, in 2020 foreign travellers' expenditure in Italy fell by about three fifths compared with previous year (from €44 to 17 billion), and the travel surplus of the balance of payments was halved to 0.5 per cent of GDP (from 1.0 per cent in 2019).

In this context, the adequate design and evaluation of policy responses clearly requires a thorough understanding of how inbound tourism is affected by contagion risk and to containment measures of different intensity. In particular, two main questions deserve closer investigation to inform policy decisions. The first is to what extent the fall in foreign arrivals reflects not only regulatory restrictions and containment measures (travel bans, quarantines, etc.) but also fears of contagion that spontaneously lead travellers to stay away from destinations with a locally higher epidemiological risk. Answering this question is highly relevant from a policy perspective: lifting restrictions while the epidemic is still not under control might not be sufficient to revamp tourism flows if travellers' behaviour actively responds to the risk of contagion. In fact, it may affect tourists decision in the future period.

The second related question is how travel preferences changed in reaction to the pandemic, looking at characteristics that were indirectly related to contagion risk, such as transport means, type of accommodation and amenities at the destination. A proper understanding of these factors is needed to formulate reasonable predictions about which destinations are going to record a larger drop in tourism inflows, so that adequate policy responses can be prepared. Understanding how tourists react to travel restrictions of varying intensity (from quarantine requirements to screening tests) would also be useful for the same purpose.

This paper uses a unique combination of weekly mobile phone data and survey data for Italy to provide answers to the above questions, through an overarching analysis of international tourism flows during the pandemic. The high frequency of mobile phone data on the number of foreign visitors by nationality and province allows us to identify precisely the impact of changing patterns in the epidemics and of the adopted policy measures. We estimate reduced‐form models (consistent with a gravity framework) where the number of foreign travellers in a given location is related to the risk of contagion in the province of stay as well as in the source country, controlling for an extensive set of fixed effects. We also look at how structural characteristics of destinations shaped the dynamics of tourism flows in interaction with the contagion dynamics. We provide compelling evidence that travellers paid a lot of attention to contagion risk during the second wave of contagion—when travel restrictions were looser—avoiding local Italian destinations with a higher number of COVID‐19 cases. Furthermore, destinations that were perceived as ‘less risky’ by tourists (for instance because they were reachable by private means of transport or had a larger share of private accommodations), were hit less, all other things being equal.

This paper is at the intersection of two strands of literature. The first and larger strand is about the adverse effects that infectious diseases cast on the economy, and on tourism in particular. It received an important boost in the 2000s, after the outbreak of the SARS and the ‘aviary flu’ in Asia (Chou et al., 2004 ; Hanna & Huang, 2004 ; McKercher & Chon, 2004 ), followed by studies on MERS (Joo et al., 2019 ) and the H1N1 influenza (Rassy & Smith 2013 ). All of these studies show that the tourism sector was hit the hardest, finding a negative relationship between contagion dynamics and foreign arrivals. In particular, Hanna and Huang ( 2004 ) find that the impact was higher in regions characterised by higher population density, higher mobility of people, and where public health infrastructure was less developed. Chou et al. ( 2004 ) conclude that a failure in disclosing the actual number of SARS cases can deliver additional GDP loss in the longer run, pointing to the fact that not only international travellers but also foreign investors need accurate information on the dynamic of the epidemic. More recently, Cevik ( 2020 ) compares the impact of different kind of diseases on bilateral tourism flows, showing that the impact on tourism is due more to the contagiousness of the disease than to its severity, and that negative effects are stronger for developing countries.

With the outbreak of COVID‐19, the first truly global pandemic after the 1918–1919 influenza (so‐called ‘Spanish flu’), a large and growing bulk of papers was added to this workstream. Given the pervasiveness of the shock and the strictness of countermeasures that were adopted worldwide, studies have analysed the impact not only on tourism but also on trade of goods (Bas et al., 2022 ; Berthou & Stumpner, 2022 ; Liu et al., 2021 ) and services in general (Ando & Hayakawa, 2022 ; Minondo, 2021 ). 4 The present crisis is in fact characterised by quick and wider developments, impacting all countries across the globe. As regards impact of COVID‐19 on tourism, existing studies are largely descriptive (MacDonald et al., 2020 ; Metaxas & Folinas, 2020 ; Uğur & Akbıyık, 2020 ; see Sigala, 2020 for a preliminary survey) or focus on specific segments of the tourism industry, such as short‐term rental: Hu and Lee ( 2020 ) quantify the impact of lockdown on global AirBnB bookings. Focusing on the European short‐term rental market, Guglielminetti et al. ( 2021 ) find that the epidemic reduced markedly both the supply of apartments available for rents and the consumers' demand. Our paper contributes to this literature with a rich econometric analysis of the effects of COVID‐19 on foreign arrivals in Italy. We believe that Italy is an ideal setting for this analysis, for three reasons. First, it is one of the largest exporters of tourism services (Italian tourism exports rank sixth in the world, according to UNWTO), so it is a very relevant case study. Second, it is endowed with a well‐diversified range of destinations associated with different travel purposes (business trips, art visits, beach or mountain holidays, etc.), and it attracts visitors from a very diverse set of departure countries, which allows to study the interaction between characteristics of both local destinations and countries of departure. Third, the significant heterogeneity in the spread of contagion across the country allows a quite neat identification of the response of tourism to the differential level of the epidemic among local destinations, while controlling for developments at the country level. This allows us to draw several conclusions on the response of international tourism to the pandemic which are potentially useful for policymaking purposes.

The second strand of literature this study is related to is the growing number of research papers using location data derived from mobile phone networks for the analysis of mobility and consumer behaviour (Hu et al., 2009 ; Tucker & Yu, 2020 ). Mobile phone data have been used in behavioural studies for almost two decades (Spinney, 2003 ) and the use of this data for tourism analysis is not entirely new. 5 The availability of such data accelerated when smartphones massively replaced first‐generation mobile phones. As this paper confirms, this type of data has become a very valuable complement to more conventional data sources (e.g. survey data), especially for tourism analysis.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides descriptive evidence on the changes that occurred in incoming tourism flows after the pandemic along various dimensions, paving the way for the subsequent econometric analysis. Section 3 presents the database and the empirical model adopted to measure the impact of the pandemic on the incoming tourism flows and its interaction with variables at the province and the country of departure level. In Section 4 , we present and discuss estimation results, robustness evaluations and economic interpretation of regression coefficients. Finally, Section 5 summarises our findings and draws concluding remarks.

2. AGGREGATE PATTERNS OF FOREIGN TOURISM FLOWS IN ITALY

This section of the paper presents the main aggregate patterns in foreign tourism to Italy in 2020, highlighting the heterogeneous impact of the pandemic. This evidence guides us in the selection of relevant variables for the empirical model presented in Section 3 .

The COVID‐19 disease started to spread in Italy in the second half of February 2020. The lockdown was applied initially in selected Northern provinces and, since March 9, in the entire country. It included a stay‐at‐home order, the shutdown of all non‐essential economic activities and restrictions to both internal and international mobility. In this phase, the outbreak remained concentrated in Northern Italy. These restrictions were lifted during the month of May 2020. The strong containment measures proved to be effective in halting the spread of the disease, and Italy benefited of near‐zero rate of new COVID‐19 cases throughout the summer. In early June travel restrictions between EU member countries, Schengen Area countries and United Kingdom were lifted, and inbound tourism gradually resumed. New case rates started picking up again at the end of August, and in the fall a second wave of contagion hit Italy throughout the country, with virtually no province spared from a rise in infections.

According to official statistics, in 2020 foreign visitors in Italy (i.e. including those who did not stay in Italy overnight) were 39 million overall, about 60% less than the previous year. 6 The drop in inbound tourism was sharp from all countries of origin, but particularly severe from farther countries (Table 1 and Figure 1 ): the number of arrivals from Europe (both EU and non‐EU) decreased by 56.2% with respect to 2019; those from the Americas and Asia fell by 87% and 81% respectively.

Changes in the number of foreign travellers in Italy.

Source : BISIT data. Changes refer to 2020 with respect to 2019.

Changes in the number of foreign arrivals by area of origin and new COVID‐19 cases. Lines represent monthly foreign arrivals in 2020 vis‐à‐vis the corresponding months in 2019 in percentage terms (scale on the left‐hand axis). Histograms (scale on the right‐hand side axis) represent the number of new COVID‐19 cases occurred in Italy in each month.

These patterns were likely affected by the travel bans adopted in many countries throughout the world (including Italy), but they may also reflect a preference by foreign tourists for destinations closer to home that can be reached by private means of transport. Indeed, the drop of arrivals in regions closer to Italian borders (such as Veneto and Lombardy) was relatively smaller than in the other regions.

The pandemic also induced changes along the dimension of the travel's motive, as suggested by the correlation between the ex ante shares of various travel purposes in each Italian province (which capture their ‘touristic specialisation’) and the change in arrivals between 2019 and 2020 (Figure 2 ). 7 Arrivals dropped systematically more in provinces specialised in cultural tourism purposes, while this correlation is weaker for ‘sea and nature’ holidays. The correlation is instead positive in the case of business tourism, meaning that the provinces that used to have a relatively higher share of tourism related to business reasons suffered much less in terms of decline in foreign arrivals.

Correlation between change in arrivals and travel purpose shares at province level. Each dot represents an Italian province. In all graphs, vertical axis reports the drop in arrivals between 2019 and 2020 in % terms, while horizontal axis reports the share of travellers that used to visit the province before 2020 for the specified travel purpose.

Finally, another relevant change was observed along a third dimension of interest: the type of accommodation chosen by visitors during their sojourn in Italy. As shown in Table 2 , comparing 2020 data with the pre‐COVID‐19 three‐year period (2017–2019), shares of ‘traditional’ accommodations (hotel, B&B, tourist resort) decreased significantly (for over 14 percentage points), mainly to the advantage of independent non‐shared accommodations (rented houses or own properties) or other less common accommodations (campers, tents, caravans, etc.). The share of visitors who stayed at home with relatives or friends during their sojourn also grew significantly.

Accommodation choices pre‐ and post‐COVID‐19.

Note : ‘Other accommodations’ includes also camping, caravans and farmhouses.

Source : BISIT data. All values are shares. Values for 2017–2019 are averages.

3. THE HETEROGENEOUS IMPACT OF COVID ‐19 ON TOURISM: DATA AND EMPIRICAL MODEL

3.1. data sources and variables definition.

We combine various sources of information about tourism, epidemiological patterns and policy measures, to build a comprehensive and detailed dataset for our empirical exercise. The dataset covers the period from January 2019 to February 2021.

Two main sources are used for tourism data, to quantify the number of foreign tourists and to gather information on tourism characteristics. The first source of data comes from a primary Italian mobile phone operator. It provides the total number of foreign phone SIM cards on the Italian territory, by province and by issuer country. We use the former as information about the province of destination and the latter as a proxy for the country of origin of the traveller. Mobile phone data are available at a daily frequency (we aggregate them into weekly data). This source provides several important advantages. First, the data cover also the months in which the Bank of Italy Survey on International Travel was discontinued because of the restrictions against the spread of the pandemic. Second, the higher (weekly) data frequency allows to assess the impact that the contagion dynamics and the policy responses had on tourism patterns in a much more precise way than what could be done with monthly data: for instance, we can match the increase in cases occurred in a given week with the tourism flows observed in subsequent weeks, while controlling for the travel restriction in place in that specific week of the year. Finally, the extensive coverage provided by mobile phone data allows to look at combinations of ‘country of origin – province – time’ that in BISIT data may be subject to significant measurement error (e.g. for smaller countries and provinces). One limitation however is that the number of foreign tourists derived from mobile phone data may be distorted by the presence of communities of foreign residents in Italy. To avoid this potential bias, in our analysis we considered the first 40 countries, in terms of the number of tourists in 2017–2019, excluding those having large communities of residents in Italy. The selected countries account for about 94 per cent of the total inbound tourism flows to Italy (over the period 2017–2019); half of them belong to the European Union. 8

The second source of tourism data is the Bank of Italy Survey on International Tourism (BISIT). The survey questionnaire asks the interviewed traveller to provide information about the kind of transportation used to reach the destination, the purpose of the trip and the type of accommodation used during the trip (if any). We use data for the period 2017–2019 to construct indicators before the pandemic outbreak: for each province and origin, we quantify the shares of travellers by travel purpose, accommodation type and means of transport.

The epidemiological data regarding the spread of the contagion in Italy are sourced from the Italian Civil Protection Department. 9 At province level, the only available information is the cumulative number of positive COVID‐19 cases, at a daily frequency. From this, we compute the number of new cases of COVID‐19 (gross of recovered patients) over a period of 14 days, per 1000 inhabitants. The resident population in the province at the end of 2019 is retrieved from ISTAT, the Italian national statistical institute.

The corresponding information on the evolution of COVID‐19 in the foreign countries of origin was obtained from the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), which provides harmonised and comparable data on the rate of contagion in all European countries and in all other non‐European countries considered in our analysis.

As for the containment measures adopted by foreign countries, we used the Oxford Stringency Index (Hale et al., 2021 ), which reflects restrictions to different aspects of economic and social life, such as mandatory closure of schools and offices to remote functioning, shops and restaurants closures, restrictions on public transportation and international travel bans. To control for the different intensity of the restrictions by Italian regions enforced since November 2020, we relied on the index developed for Italy by Conteduca ( 2021 ). 10

We also constructed a set of dummies related to the intensity of bilateral travel restrictions enforced by the Italian Government. This information was collected from the legislation acts adopted throughout the period, also relying on the website ‘ reopen.europa.eu ’, and on the website of Italy's Foreign affairs Ministry ‘ www.viaggiaresicuri.it ’.

Finally, variables on bilateral distance were retrieved from the CEPII data warehouse (Mayer & Zignago, 2011 ).

3.2. The empirical strategy

Our empirical exercise aims at explaining the heterogeneous impact of COVID‐19 on international tourism to Italy disentangling the contribution of various factors at the province and the country‐of‐origin level. In practice, the empirical strategy relies on two mirror‐like reduced‐form models for inbound tourism to Italy that are in line with a gravity framework. We estimate those models using the Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood estimator on weekly data from January 2019 to February 2021. 11