Journal of Tourism and Development

Subject Area and Category

- Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management

- Geography, Planning and Development

Publication type

16459261, 21821453

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

Evoution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- Articles in Press

- Current Issue

Journal Archive

The qualitative model of health tourism marketing and its effect on tourism attraction in health villages based on grounded theory c.

10.22034/jtd.2023.382998.2731

Forough zekavati; leila Andervazh; SOHEILA ZARINJOYALVAR

- View Article

- PDF 510.88 K

Challenges Of Civil Responsibility Of Tourism Guide And Technical Director Of Tourism Services Office In Iranian Law And A Comparative Study With French Law

Pages 19-32

10.22034/jtd.2023.385092.2739

Ahmad Mir dadashi; Seyyed mahdi Mir dadashi; Alireza Shamshiri

- PDF 378.8 K

Analyzing The Restrictive Factors Of Tourism Development In Karbala Province, Iraq

Pages 33-49

10.22034/jtd.2023.403352.2787

Habibollah Fasihi; Ali Shamai; Mohammad Soleimani Mehnejani; Mousa Kamanroudi Kojouri; Zaid Onaibi

- PDF 786.7 K

Presenting a Model of Organizational Crisis Management in Iran's Tourism Industry (with an Emphasis on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Pages 51-63

10.22034/jtd.2024.410888.2812

Jamileh Ghasemloi Soltanabad; Seyyed Habibollah Mirghafoori; Mir Mohammad Asadi; Hamed Fallah Tafti

Estimating the Economic Value of Tourist Attractions Using the Contingent Valuation Method (Case Study: Dowlatabad Garden, Yazd Province, Iran)

Pages 65-78

10.22034/jtd.2023.392920.2758

Gholamhosein Moradi; Farnaz Dehghan Benadkuki; Sajad Ghanbari; Mostafa Moradi

- PDF 567.18 K

Publication Information

Indexing and abstracting.

Keywords Cloud

Tourism and Sustainable Economic Development: Evidence from Belt and Road Countries

- Published: 22 January 2022

- Volume 14 , pages 503–516, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Uktam Umurzakov 1 ,

- Shakhnoza Tosheva 2 &

- Raufhon Salahodjaev 3 , 4 , 5

1214 Accesses

17 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study is aimed to fill an existing gap in the empirical literature by exploring the effect of tourism on sustainable economic development across Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries. BRI is one of the paramount global partnerships as it covers more than 60 percent of the global population and 30 percent of the world’s GDP. Using data from 57 nations over the period of 2000–2018 and applying two-step generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator, we show that tourism has a positive and significant effect on sustainable development, measured by adjusted net national income. In particular, moving from a country with the lowest to highest number of per capita tourist arrivals leads to a 15.2% increase in adjusted per capita income. The results also remain valid using alternative econometric estimation techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An empirical note on tourism and sustainable development nexus

Perspectives of globalization and tourism as drivers of ecological footprint in top 10 destination economies

Dynamic linkages between tourism, energy, environment, and economic growth: evidence from top 10 tourism-induced countries.

Ahmad, F., Draz, M. U., Su, L., Ozturk, I., & Rauf, A. (2018). Tourism and environmental pollution: Evidence from the one belt one road provinces of Western China. Sustainability, 10 (10), 3520.

Article Google Scholar

Akinboade, O. A., & Braimoh, L. A. (2010). International tourism and economic development in South Africa: A Granger causality test. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12 (2), 149–163.

Alam, K. J., & Sumon, K. K. (2020). Causal relationship between trade openness and economic growth: A panel data analysis of Asian countries. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 10 (1), 118.

Alhowaish, A. K. (2016) Is tourism development a sustainable economic growth strategy in the long run? Evidence from GCC Countries. Sustainability, 8 (7), 605.

Antonakakis, N., Dragouni, M., Eeckels, B., & Filis, G. (2016). Tourism and economic growth: Does democracy matter? Annals of Tourism Research, 61 , 258–264.

Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2020). Foreign direct investment, information technology and economic growth dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy , 44 (1), 101838.

Azam, M. (2021). Governance and economic growth: Evidence from 14 Latin America and Caribbean Countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 1–26.

Balli, E., Sigeze, C., Manga, M., Birdir, S., & Birdir, K. (2019). The relationship between tourism, CO2 emissions and economic growth: A case of Mediterranean countries. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24 (3), 219–232.

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The quarterly journal of economics, 106 (2), 407–443.

Batuo, M., Mlambo, K., & Asongu, S. (2018). Linkages between financial development, financial instability, financial liberalisation and economic growth in Africa. Research in International Business and Finance, 45 , 168–179.

Belloumi, M. (2010). The relationship between tourism receipts, real effective exchange rate and economic growth in Tunisia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12 (5), 550–560.

Beladi, H., Chao, C. C., Ee, M. S., & Hollas, D. (2019). Does medical tourism promote economic growth? A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 58 (1), 121–135.

Bento, J. P. (2016). Tourism and economic growth in Portugal: An empirical investigation of causal links. Tourism & Management Studies, 12 (1), 164–171.

Bilen, M., Yilanci, V., & Eryüzlü, H. (2017). Tourism development and economic growth: A panel Granger causality analysis in the frequency domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 20 (1), 27–32.

Bouzahzah, M., & El Menyari, Y. (2013). International tourism and economic growth: The case of Morocco and Tunisia. The Journal of North African Studies, 18 (4), 592–607.

Brida, J. G., Gómez, D. M., & Segarra, V. (2020). On the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth. Tourism Management , 81 , 104131.

Brida, J. G., & Risso, W. A. (2009). Tourism as a factor of long-run economic growth: An empirical analysis for Chile. European Journal of Tourism Research , 2 (2).

Castro-Nuño, M., Molina-Toucedo, J. A., & Pablo-Romero, M. P. (2013). Tourism and GDP: A meta-analysis of panel data studies. Journal of Travel Research, 52 (6), 745–758.

Chou, M. C. (2013). Does tourism development promote economic growth in transition countries? A panel data analysis. Economic Modelling, 33 , 226–232.

Cole, M. A. (2004). Trade, the pollution haven hypothesis and the environmental Kuznets curve: Examining the linkages. Ecological Economics, 48 (1), 71–81.

Corrie, K., Stoeckl, N., & Chaiechi, T. (2013). Tourism and economic growth in Australia: An empirical investigation of causal links. Tourism Economics, 19 (6), 1317–1344.

Cortés-Jiménez, I., Nowak, J. J., & Sahli, M. (2011). Mass beach tourism and economic growth: Lessons from Tunisia. Tourism Economics, 17 (3), 531–547.

Dogru, T., & Bulut, U. (2018). Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tourism Management, 67 , 425–434.

Dogru, T., Bulut, U., Kocak, E., Isik, C., Suess, C., & Siraka-Turk, E. (2020). The nexus between tourism, economic growth, renewable energy consumption, and carbon dioxide emissions: Contemporary evidence from OECD countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10110-w

Fayissa, B., Nsiah, C., & Tadasse, B. (2008). Impact of tourism on economic growth and development in Africa. Tourism Economics, 14 (4), 807–818.

Fleurbaey, M. (2009). Beyond GDP: The quest for a measure of social welfare. Journal of Economic Literature, 47 (4), 1029–1075.

Fu, X., Ridderstaat, J., & Jia, H. C. (2020). Are all tourism markets equal? Linkages between market-based tourism demand, quality of life, and economic development in Hong Kong. Tourism Management , 77 , 104015.

Ghardallou, W., & Sridi, D. (2020). Democracy and economic growth: A literature review. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11 (3), 982–1002.

Haller, A. P., Butnaru, G. I., Hârșan, G. D. T., & Ştefănică, M. (2021). The relationship between tourism and economic growth in the EU-28. Is there a tendency towards convergence?. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja , 34 (1), 1121–1145.

Helali, K. (2021). Markov Switching-Vector Auto Regression Model Analysis of the economic and growth cycles in Tunisia and its main European partners. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00740-x

Holzner, M. (2011). Tourism and economic development: The beach disease? Tourism Management, 32 (4), 922–933.

Hughes, C. G. (1982). The employment and economic effects of tourism reappraised. Tourism Management, 3 (3), 167–176.

Ighodaro, C. A., & Adegboye, A. C. (2020). Long run analysis of tourism and economic growth in Nigeria. International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 13 (3), 286–301.

Isaeva, A., Salahodjaev, R., Khachaturov, A., & Tosheva, S. (2021). The impact of tourism and financial development on energy consumption and carbon dioxide emission: Evidence from post-communist countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 1–14.

Islam, M. S. (2020). Human capital and per capita income linkage in South Asia: A heterogeneous dynamic panel analysis. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 1–16.

Jin, J. C. (2011). The effects of tourism on economic growth in Hong Kong. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 52 (3), 333–340.

Kadir, N., & Karim, M. Z. A. (2012). Tourism and economic growth in Malaysia: Evidence from tourist arrivals from ASEAN-S countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 25 (4), 1089–1100.

Kaiser, C. F., & Vendrik, M. C. (2019). Different versions of the Easterlin Paradox: New evidence for European countries. In The Economics of Happiness (pp. 27–55). Springer, Cham.

Kapera, I. (2018). Sustainable tourism development efforts by local governments in Poland. Sustainable Cities and Society, 40 , 581–588.

Katircioglu, S. T. (2009). Revisiting the tourism-led-growth hypothesis for Turkey using the bounds test and Johansen approach for cointegration. Tourism Management, 30 (1), 17–20.

Khalil, S., Kakar, M. K., & Malik, A. (2007). Role of tourism in economic growth: Empirical evidence from Pakistan economy [with comments]. The Pakistan Development Review , 985–995.

Kim, H. J., & Chen, M. H. (2006). Tourism expansion and economic development: The case of Taiwan. Tourism Management, 27 (5), 925–933.

Kumar, N., Kumar, R. R., Kumar, R., & Stauvermann, P. J. (2020). Is the tourism–growth relationship asymmetric in the Cook Islands? Evidence from NARDL cointegration and causality tests. Tourism Economics, 26 (4), 658–681.

Lee, J. W., & Brahmasrene, T. (2013). Investigating the influence of tourism on economic growth and carbon emissions: Evidence from panel analysis of the European Union. Tourism Management, 38 , 69–76.

Lee, C. C., & Chang, C. P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tourism Management, 29 (1), 180–192.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8 (6), 522–528.

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., & Asif, M. (2019). The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (19), 3785.

Mishra, P. K., Rout, H. B., & Mohapatra, S. S. (2011). Causality between tourism and economic growth: Empirical evidence from India. European Journal of Social Sciences, 18 (4), 518–527.

Google Scholar

Mrabet, Z., AlSamara, M., & Jarallah, S. H. (2017). The impact of economic development on environmental degradation in Qatar. Environmental and Ecological Statistics, 24 (1), 7–38.

Narayan, P. K., Narayan, S., Prasad, A., & Prasad, B. C. (2010). Tourism and economic growth: A panel data analysis for Pacific Island countries. Tourism Economics, 16 (1), 169–183.

Nkoa, B. E. O., & Song, J. S. (2021). Does institutional quality increase inequalities in Africa?. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 1–32.

Nunkoo, R., Seetanah, B., Jaffur, Z. R. K., Moraghen, P. G. W., & Sannassee, R. V. (2020). Tourism and economic growth: A meta-regression analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 59 (3), 404–423.

Nyasha, S., Odhiambo, N. M., & Asongu, S. A. (2020). The impact of tourism development on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. The European Journal of Development Research , 1–22.

Obydenkova, A., Nazarov, Z., & Salahodjaev, R. (2016). The process of deforestation in weak democracies and the role of intelligence. Environmental Research, 148 , 484–490.

Oh, C. O. (2005). The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Management, 26 (1), 39–44.

Ohlan, R. (2017). The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Business Journal, 3 (1), 9–22.

Pegkas, P. (2020). Interrelationships between tourism, energy, environment and economic growth in Greece. Anatolia, 31 (4), 565–576.

Proença, S., & Soukiazis, E. (2008). Tourism as an economic growth factor: A case study for Southern European countries. Tourism Economics, 14 (4), 791–806.

Rasool, H., Maqbool, S., & Tarique, M. (2021). The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Business Journal, 7 (1), 1–11.

Roudi, S., Arasli, H., & Akadiri, S. S. (2019). New insights into an old issue–Examining the influence of tourism on economic growth: Evidence from selected small island developing states. Current Issues in Tourism, 22 (11), 1280–1300.

Saba, C. S., & Ngepah, N. (2021). ICT Diffusion, industrialisation and economic growth nexus: An international cross-country analysis. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 1–40.

Sağlam, Y., & EGELİ, H. A. (2018). The nexus between tourism and economic growth: Case of Commonwealth of Independent States. Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic Tourism, 3 (2), 45–51.

Sanchez Carrera, E. J., Brida, J. G., & Risso, W. A. (2008). Tourism’s impact on long-run Mexican economic growth. Economics Bulletin, 23 (21), 1–8.

Santamaria, D., & Filis, G. (2019). Tourism demand and economic growth in Spain: New insights based on the yield curve. Tourism Management, 75 , 447–459.

Shaheen, K., Zaman, K., Batool, R., Khurshid, M. A., Aamir, A., Shoukry, A. M., & Gani, S. (2019). Dynamic linkages between tourism, energy, environment, and economic growth: Evidence from top 10 tourism-induced countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26 (30), 31273–31283.

Shahbaz, M., Ferrer, R., Shahzad, S. J. H., & Haouas, I. (2018). Is the tourism–economic growth nexus time-varying? Bootstrap rolling-window causality analysis for the top 10 tourist destinations. Applied Economics, 50 (24), 2677–2697.

Shahzad, S. J. H., Shahbaz, M., Ferrer, R., & Kumar, R. R. (2017). Tourism-led growth hypothesis in the top ten tourist destinations: New evidence using the quantile-on-quantile approach. Tourism Management, 60 , 223–232.

Schubert, S. F., Brida, J. G., & Risso, W. A. (2011). The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tourism Management, 32 (2), 377–385.

Seetanah, B. (2011). Assessing the dynamic economic impact of tourism for island economies. Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (1), 291–308.

Siddiqui, A., & Rehman, A. U. (2017). The human capital and economic growth nexus: In East and South Asia. Applied Economics , 49 (28), 2697–2710.

Srinivasan, P., Kumar, P. S., & Ganesh, L. (2012). Tourism and economic growth in Sri Lanka: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Environment and Urbanization Asia, 3 (2), 397–405.

Sokhanvar, A. (2019). Does foreign direct investment accelerate tourism and economic growth within Europe? Tourism Management Perspectives, 29 , 86–96.

Sokhanvar, A., & Jenkins, G. P. (2021). Impact of foreign direct investment and international tourism on long-run economic growth of Estonia. Journal of Economic Studies .

Stauvermann, P. J., Kumar, R. R., Shahzad, S. J. H., & Kumar, N. N. (2018). Effect of tourism on economic growth of Sri Lanka: Accounting for capital per worker, exchange rate and structural breaks. Economic Change and Restructuring, 51 (1), 49–68.

Su, Y., Cherian, J., Sial, M. S., Badulescu, A., Thu, P. A., Badulescu, D., & Samad, S. (2021). Does tourism affect economic growth of China? A Panel Granger Causality Approach. Sustainability, 13 (3), 1349.

Sun, X., Chenggang, Y., Khan, A., Hussain, J., & Bano, S. (2021). The role of tourism, and natural resources in the energy-pollution-growth nexus: An analysis of Belt and Road Initiative countries. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64 (6), 999–1020.

Surugiu, C., & Surugiu, M. R. (2013). Is the tourism sector supportive of economic growth? Empirical evidence on Romanian tourism. Tourism Economics, 19 (1), 115–132.

Tang, C. F., & Abosedra, S. (2014). The impacts of tourism, energy consumption and political instability on economic growth in the MENA countries. Energy Policy, 68 , 458–464.

Tang, C. F. (2021). The threshold effects of educational tourism on economic growth. Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (1), 33–48.

Tecel., A., Katiricioglu, S., Taheri, E., & Bekun, F.V. (2020). Causal interactions among tourism, foreign direct investment, domestic credits, and economic growth: Evidence from selected Mediterranean countries. Portuguese Economic Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-020-00181-5

Tugcu, C. T. (2014). Tourism and economic growth nexus revisited: A panel causality analysis for the case of the Mediterranean Region. Tourism Management, 42 , 207–212.

Wu, T. P., & Wu, H. C. (2019). Tourism and economic growth in Asia: A bootstrap multivariate panel Granger causality. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21 (1), 87–96.

Wu, T. P., Wu, H. C., Wu, Y. Y., Liu, Y. T., & Wu, S. T. (2020). Causality between tourism and economic growth. Journal of China Tourism Research , 1–18.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Tashkent Institute of Irrigation and Agricultural Mechanization Engineers, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Uktam Umurzakov

ERGO Analytics, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Shakhnoza Tosheva

Tashkent State University of Economics, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Raufhon Salahodjaev

AKFA University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Tashkent, Uzbekistan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Raufhon Salahodjaev .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Umurzakov, U., Tosheva, S. & Salahodjaev, R. Tourism and Sustainable Economic Development: Evidence from Belt and Road Countries. J Knowl Econ 14 , 503–516 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00872-0

Download citation

Received : 22 January 2021

Accepted : 01 December 2021

Published : 22 January 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00872-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

- Sustainability

- Belt and Road

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries

- Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1779-392X 1 ,

- Juan Gabriel Brida 2 &

- Verónica Segarra 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1533 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

Having previously analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic growth from distinct perspectives, this paper attempts to fill the void existing in scientific research on the relationship between tourism and economic development, by analyzing the relationship between these variables using a sample of 123 countries between 1995 and 2019. The Dumistrescu and Hurlin adaptation of the Granger causality test was used. This study takes a critical look at causal analysis with heterogeneous panels, given the substantial differences found between the results of the causal analysis with the complete panel as compared to the analysis of homogeneous country groups, in terms of their dynamics of tourism specialization and economic development. On the one hand, a one-way causal relationship exists from tourism to development in countries having low levels of tourism specialization and development. On the other hand, a one-way causal relationship exists by which development contributes to tourism in countries with high levels of development and tourism specialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

The economic commitment of climate change

Entropy, irreversibility and inference at the foundations of statistical physics

Introduction.

Across the world, tourism is one of the most important sectors. It has undergone exponential growth since the mid-1900s and is currently experiencing growth rates that exceed those of other economic sectors (Yazdi, 2019 ).

Today, tourism is a major source of income for countries that specialize in this sector, generating 5.8% of the global GDP (5.8 billion US$) in 2021 (UNWTO, 2022 ) and providing 5.4% of all jobs (289 million) worldwide. Although its relevance is clear, tourism data have declined dramatically due to the recent impact of the Covid-19 health crisis. In 2019, prior to the pandemic (UNWTO, 2020 ), tourism represented 10.3% of the worldwide GDP (9.6 billion US$), with the number of tourism-related jobs reaching 10.2% of the global total (333 million). With the evolution of the pandemic and the regained trust of tourists across the globe, it is estimated that by 2022, approximately 80% of the pre-pandemic figures will be attained, with a full recovery being expected by 2024 (UNWTO, 2022 ).

Given the importance of this economic activity, many countries consider tourism to be a tool enabling economic growth (Corbet et al., 2019 ; Ohlan, 2017 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). Numerous works have analyzed the relationship between increased tourism and economic growth; and some systematic reviews have been carried out on this relationship (Brida et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2020 ), examining the main contributions over the first two decades of this century. These reviews have revealed evidence in this area: in some cases, it has been found that tourism contributes to economic growth while, in other cases, the economic cycle influences tourism expansion. Moreover, other works offer evidence of a bi-directional relationship between these variables.

Distinct international organizations (OECD, 2010 ; UNCTAD, 2011 ) have suggested that not only does tourism promote economic growth, it also contributes to socio-economic advances in the host regions. This may be the real importance of tourism, since the ultimate objective of any government is to improve a country’s socio-economic development (UNDP, 1990 ).

The development of economic and other policies related to the economic scope of tourism, in addition to promoting economic growth, are also intended to improve other non-economic factors such as education, safety, and health. Improvements in these factors lead to a better life for the host population (Lee, 2017 ; Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

Given tourism’s capacity as an instrument of economic development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), distinct institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the United Nations World Tourism Organization and the World Bank, have begun funding projects that consider tourism to be a tool for improved socio-economic development, especially in less advanced countries (Carrillo and Pulido, 2019 ).

This new trend within the scientific literature establishes, firstly, that tourism drives economic growth and, secondly, that thanks to this economic growth, the population’s economic conditions may be improved (Croes et al., 2021 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ). However, to take advantage of the economic growth generated by tourism activity to boost economic development, specific policies should be developed. These policies should determine the initial conditions to be met by host countries committed to tourism as an instrument of economic development. These conditions include regulation, tax system, and infrastructure provision (Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Lejárraga and Walkenhorst, 2013 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ).

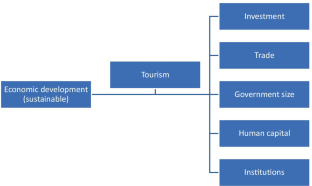

Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, whereby tourism boosts the economy of countries committed to tourism, traditionally measured through an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Alcalá-Ordóñez et al., 2023 ; Brida et al., 2016 ), and the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development, which measures the effect of tourism on other factors (not only economic content but also inequality, education, and health) which, together with economic criteria, serve as the foundation to measure a population’s development (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

However, unlike the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, few empirical studies have examined tourism’s capacity as a tool for development (Bojanic and Lo, 2016 ; Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Croes, 2012 ).

To help fill this gap in the literature analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, this work examines the contribution of tourism to economic development, given that the relationship between tourism and economic growth has been widely analyzed by the scientific literature. Moreover, given that the literature has demonstrated that tourism contributes to economic growth, this work aims to analyze whether it also contributes to economic development, considering development in the broadest possible sense by including economic and socioeconomic variables in the multi-dimensional concept (Wahyuningsih et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, based on the results of this work, it is possible to determine whether the commitment made by many international organizations and institutions in financing tourism projects designed to improve the host population’s socioeconomic conditions, especially in countries with lower development levels, has, in fact, resulted in improved development levels.

It also presents a critical view of causal analyses that rely on heterogeneous panels, examining whether the conclusions reached for a complete panel differ from those obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups within the panel. As seen in the literature review analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, empirical works using panel data from several countries tend to generalize the results obtained to the entire panel, without verifying whether, in fact, they are relevant for all of the analyzed countries or only some of the same. Therefore, this study takes an innovative approach by examining the panel countries separately, analyzing the homogeneous groups distinctly.

Therefore, this article presents an empirical analysis examining whether a causal relationship exists between tourism and economic development, with development being considered to be a multi-dimensional variable including a variety of factors, distinct from economic ones. Panel data from 123 countries during the 1995–2019 period was considered to examine the causal relationship between tourism and economic development. For this, the Granger causality test was performed, applying the adaptation of this test made by Dumistrescu and Hurlin. First, a causal analysis was performed collectively for all of the countries of the panel. Then, a specific analysis was performed for each of the homogeneous groups of countries identified within the panel, formed according to levels of tourism specialization and development.

This article provides information on tourism’s capacity to serve as an instrument of development, helping to fill the gap in scientific research in this area. It critically examines the use of causal analyses based on heterogeneous samples of countries. This work offers the following main novelties as compared to prior works on the same topic: firstly, it examines the relationship between tourism and economic development, while the majority of the existing works only analyze the relationship between tourism and economic growth; secondly, it analyzes a large sample of countries, representing all of the global geographic areas, whereas the literature has only considered works from specific countries or a limited number of nations linked to a specific country in a specific geographical area, and; thirdly, it analyzes the panel both individually and collectively, for each of the homogenous groups of countries identified, permitting the adoption of specific policies for each group of countries according to the identified relationship, as compared to the majority of works that only analyze the complete panel, generalizing these results for all countries in the sample.

Overall, the results suggest that a relationship exists between tourism and development in all of the analyzed countries from the sample. A specific analysis was performed for homogeneous country groups, only finding a causal relationship between tourism and development in certain country groups. This suggests that the use of heterogeneous country samples in causal analyses may give rise to inappropriate conclusions. This may be the case, for example, when finding causality for a broad panel of countries, although, in fact, only a limited number of panel units actually explain this causal relationship.

The remainder of the document is organized as follows: the next section offers a review of the few existing scientific works on the relationship between tourism and economic development; section three describes the data used and briefly explains the methodology carried out; section four details the results obtained from the empirical analysis; and finally, the conclusions section discusses the main implications of the work, also providing some recommendations for economic policy.

Tourism and economic development

Numerous organizations currently recognize the importance of tourism as an instrument of economic development. It was not until the late 20th century, however, when the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), in its Manila Declaration, established that the development of international tourism may “help to eliminate the widening economic gap between developed and developing countries and ensure the steady acceleration of economic and social development and progress, in particular of the developing countries” (UNWTO, 1980 ).

From a theoretical point of view, tourism may be considered an effective activity for economic development. In fact, the theoretical foundations of many works are based on the relationship between tourism and development (Ashley et al., 2007 ; Bolwell and Weinz, 2011 ; Dieke, 2000 ; Sharpley and Telfer, 2015 ; Sindiga, 1999 ).

The link between tourism and economic development may arise from the increase in tourist activity, which promotes economic growth. As a result of this economic growth, policies may be developed to improve the resident population’s level of development (Alcalá-Ordóñez and Segarra, 2023 ).

Therefore, it is essential to identify the key variables permitting the measurement of the level of economic development and, therefore, those variables that serve as a basis for analyzing whether tourism results in improved the socioeconomic conditions of the host population (Croes et al., 2021 ). Since economic development refers not only to economic-based variables, but also to others such as inequality, education, or health (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ), when analyzing the economic development concept, it has been frequently linked to human development (Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ). Thus, we wish to highlight the major advances resulting from the publication of the Human Development Index (HDI) when measuring economic development, since it defines development as a multidimensional variable that combines three dimensions: health, education, and income level (UNDP, 2023 ).

However, despite the importance that many organizations have given to tourism as an instrument of economic development, basing their work on the relationship between these variables, a wide gap continues to exist in the scientific literature for empirical studies that examine the existence of a relationship between tourism and economic development, with very few empirical analyses analyzing this relationship.

First, a group of studies has examined the causal relationship between tourism and economic development, using heterogeneous samples, and without previously grouping the subjects based on homogeneous characteristics. Croes ( 2012 ) analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic development, measured through the HDI, finding that a bidirectional relationship exists for the cases of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Using annual data from 2001 to 2014, Meyer and Meyer ( 2016 ) performed a collective analysis of South African regions, determining that tourism contributes to economic development. For a panel of 63 countries worldwide, and once again relying on the HDI to define economic development, it was determined that tourism contributes to economic development. Kubickova et al. ( 2017 ), using annual data for the 1995–2007 period, analyzed Central America and Caribbean nations, determining the existence of this relationship by which tourism influences the level of economic development and that the level of development conditions the expansion of tourism. Another work examined nine micro-states of America, Europe, and Africa (Fahimi et al., 2018 ); and 21 European countries in which human capital was measured, as well as population density and tourism income, analyzing panel data and determining that tourism results in improved economic development. Finally, within this first group of works, Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ), using a broad panel of destinations, (133 countries from all geographic areas of the globe) determined that there is no relationship between tourism and economic development.

Studies performed with large country samples that attempt to determine the causal relationship between tourism and economic development by analyzing countries that do not necessarily share homogeneous characteristics, may lead to erroneous conclusions, establishing causality (or not) for panel sets even when this situation is actually explained by a small number of panel units.

Second, another group of studies have analyzed the causal relationship between tourism and economic development, considering the previous limitation, and has grouped the subjects based on their homogeneous characteristics. Cárdenas-García et al. ( 2015 ) used annual data from 1990–2010, in a collective analysis of 144 countries, making a joint panel analysis and then examining two homogeneous groups of countries based on their level of economic development. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development, but only in the most developed group of countries. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development, both for the total sample and for the homogeneous groups analyzed. Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ), using annual data for the 1993–2017 period, performed a joint analysis of 143 countries, followed by a specific analysis for three groups of countries sharing homogeneous characteristics in terms of tourism growth and development level. They determined that tourism contributes to economic development and that development level conditions tourism growth in the most developed countries.

Finally, another group of studies has analyzed the causal relationship between tourism and economic development in specific cases examined on an individual basis. In a specific analysis by Aruba et al. ( 2016 ), it was determined that tourism contributes to human development. Analyzing Malaysia, Tan et al. ( 2019 ) determined that tourism contributes to development, but only over the short term, and that level of development does not influence tourism growth. Similar results were obtained by Boonyasana and Chinnakum ( 2020 ) in an analysis carried out in Thailand. In this case of Thailand (Boonyasana and Chinnakum, 2020 ), which relied on the HDI, the relationship with economic growth was also analyzed, finding that an increase in tourism resulted in improved economic development. Finally, Croes et al. ( 2021 ), in a specific analysis of Poland, determined that tourism does not contribute to development.

As seen from the analysis of the most relevant publications detailed in Table 1 , few empirical works have considered the relationship between tourism and economic development, in contrast to the numerous works from the scientific literature that have examined the relationship between tourism and economic growth. Most of the works that have empirically analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic development have determined that tourism positively influences the improved economic development in host destinations. To a lesser extent, some studies have found a bidirectional relationship between these variables (Croes, 2012 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ) while others have found no relationship between tourism and economic development (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022 ; Croes et al., 2021 ).

Furthermore, in empirical works relying on panel data, the results have tended to be generalized to the entire panel, suggesting that tourism improves economic development in all countries that are part of the panel. This has been the case in all of the examined works, with the exception of two studies that analyzed the panel separately (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ).

Thus, it may be suggested that the use of very large country panels and, therefore, including very heterogeneous destinations, as was the case in the works of Biagi et al. ( 2017 ) using a panel of 63 countries, as well as that of Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ) working with a panel of 133 countries, may lead to error, given that this relationship may only arise in certain destinations of the panel, although it is generalized to the entire panel.

This work serves to fill this gap in the literature by analyzing the panel both collectively and separately, for each of the homogenous groups of countries that have been previously identified.

The lack of relevant works on the relationship between tourism and development, and of studies using causal analyses to examine these variables based on heterogeneous panels, may lead to the creation of rash generalizations regarding the entirety of the analyzed countries. Thus, conclusions may be reached that are actually based on only specific panel units. Therefore, we believe that this study is justified.

Methodological approach

Given the objective of this study, to determine whether a causal relationship exists between tourism and socio-economic development, it is first necessary to identify the variables necessary to measure tourism activity and development level. Thus, the indicators are highly relevant, given that the choice of indicator may result in distinct results (Rosselló-Nadal and He, 2020 ; Song and Wu, 2021 ).

Table 2 details the measurement variables used in this work. Specifically, the following indicators have been used in this paper to measure tourism and economic development:

Measurement of tourist activity. In this work, we decided to consider tourism specialization, examining the number of international tourists received by a country with regard to its population size as the measurement variable.

This information on international tourists at a national level has been provided annually by the United Nations World Tourism Organization since 1995 (UNWTO, 2023 ). This variable has been relativized based on the country’s population, according to information provided by the World Bank on the residents of each country (WB, 2023 ).

Tourism specialization is considered to be the level of tourism activity, specifically, the arrival of tourists, relativized based on the resident population, which allows for comparisons to be made between countries. It accurately measures whether or not a country is specialized in this economic activity. If the variable is used in absolute values, for example, the United States receives more tourists than Malta, so based on this variable it may be that the first country is more touristic than the second. However, in reality, just the opposite happens, Malta is a country in which tourist activity is more important for its economy than it is in the United States, so the use of tourist specialization as a measurement variable classifies, correctly, both Malta as a country with high tourism specialization and to the United States as a country with low tourism specialization.

Therefore, most of the scientific literature establishes the need to use the total number of tourists relativized per capita, given that this allows for the determination of the level of tourism specialization of a tourism destination (Dritsakis, 2012 ; Tang and Abosedra, 2016 ); furthermore, this indicator has been used in works analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development (for example, Biagi et al., 2017 ; Boonyasana and Chinnakum; 2020 ; Croes et al., 2021 ; Fahimi et al., 2018 ).

Although some works have used other variables to measure tourism, such as tourism income, exports, or tourist spending, these variables are not available for all of the countries making up the panel, so the sample would have been significantly reduced. Furthermore, the data available for these alternative variables do not come from homogeneous databases, and therefore cannot be compared.

Measurement of economic development. In this work, the Human Development Index has been used to measure development.

This information is provided by the United Nations Development Program, which has been publishing it annually at the country level since 1990 (UNDP, 2023 ).

The selection of this indicator to measure economic development is in line with other works that have defended its use to measure the impact on development level (for example, Jalil and Kamaruddin, 2018 ; Sajith and Malathi, 2020 ); this indicator has also been used in works analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development (for example, Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ; Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García, 2021 ).

Although some works have used other variables, such as poverty or inequality, to measure development, these variables are not available for all of the countries forming the panel. Therefore the sample would have been considerably reduced and the data available for these alternative variables do not come from homogenous databases, and therefore comparisons cannot be made.

These indicators are available for a total of 123 countries, across the globe. Thus, these countries form part of the sample analyzed in this study.

As for the time frame considered in this work, two main issues were relevant when determining this period: on the one hand, there is an initial time restriction for the analyzed series, given that information on the arrival of international tourists is only available as of 1995, the first year when this information was provided by the UNWTO. On the other hand, it was necessary to consider the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting tourism sector crisis, which also affected the global economy as a whole. Therefore, our time series ended as of 2019, with the overall time frame including data from 1995 to 2019, a 25-year period.

Previous considerations

Caution should be taken when considering causality tests to determine the relationships between two variables, especially in cases in which large heterogeneous samples are used. This is due to the fact that generalized conclusions may be reached when, in fact, the causality is only produced by some of the subjects of the analyzed sample. This study is based on this premise. While heterogeneity in a sample is clearly a very relevant aspect, in some cases, it may lead to conclusions that are less than appropriate.

In this work, a collective causal analysis has been performed on all of the countries of the panel, which consists of 123 countries. However, given that it is a broad sample including countries having major differences in terms of size, region, development level, or tourism performance, the conclusions obtained from this analysis may lead to the generalization of certain conclusions for the entire sample set, when in fact, these relationships may only be the case for a very small portion of the sample. This has been the case in other works that have made generalized conclusions from relatively large samples in which the sample’s homogeneity regarding certain patterns was not previously verified (Badulescu et al., 2021 ; Ömer et al., 2018 ; Gedikli et al., 2022 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ; Xia et al., 2021 ).

Therefore, after performing a collective analysis of the entire panel, the causal relationship between tourism and development was then determined for homogeneous groups of countries that share common patterns of tourism performance and economic development level, to analyze whether the generalized conclusions obtained in the previous section differ from those made for the individual groups. This was in line with strategies that have been used in other works that have grouped countries based on tourism performance (Min et al., 2016 ) or economic development level (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), prior to engaging in causal analyses. To classify the countries into homogeneous groups based on tourism performance and development level, a previous work was used (Brida et al., 2023 ) which considered the same sample of 123 countries, relying on the same data to measure tourism and development level and the same time frame. This guarantees the coherence of the results obtained in this work.

From the entire panel of 123 countries, a total of six country groups were identified as having a similar dynamic of tourism and development, based on qualitative dynamic behavior. In addition, an “outlier” group of countries was found. These outlier countries do not fit into any of the groups (Brida et al., 2023 ). The three main groups of countries were considered, discarding three other groups due to their small size. Table 3 presents the group of countries sharing similar dynamics in terms of tourism performance and economic development level.

Applied methodology

As indicated above, this work uses the Tourist Specialization Rate (TIR) and the Human Development Index (HDI) to measure tourism and economic development, respectively. In both cases, we work with the natural logarithm (l.TIR and l.HDI) as well as the first differences between the variables (d.l.TIR and d.l.HDI), which measure the growth of these variables.

A complete panel of countries is used, consisting of 123 countries. The three main groups indicated in the previous section are also considered (the first of the groups contains 36 countries, the second contains 29 and the last group contains 43).

The Granger causality test ( 1969 ) is used to analyze the relationships between tourism specialization and development level; this test shows if one variable predicts the other, but this should not be confused with a cause-effect relationship.

In the context of panel data, different tests may be used to analyze causality. Most of these tests differ with regard to the assumptions of homogeneity of the panel unit coefficients. While the standard form of the Granger causality test for panels assumes that all of the coefficients are equal between the countries forming part of the panel, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012) considers that the coefficients are different between the countries forming part of the panel. Therefore, in this work, Granger’s causality is analyzed using the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012). In this test, the null hypothesis is of no homogeneous causality; in other words, according to the null hypothesis, causality does not exist for any of the countries of the analyzed sample whereas, according to the alternative hypothesis, in which the regression model may be different in the distinct countries, causality is verified for at least some countries. The approach used by Dumitrescu and Hurlin ( 2012 ) is more flexible in its assumptions since although the coefficients of the regressions proposed in the tests are constant over time, the possibility that they may differ for each of the panel elements is accepted. This approach has more realistic assumptions, given that countries exhibit different behaviors. One relevant aspect of this type of tests is that they offer no information on which countries lead to the rejection of the lack of causality.

Given the specific characteristics of this type of tests, the presence of very heterogeneous samples may lead to inappropriate conclusions. For example, causality may be assumed for a panel of countries, when only a few of the panel’s units actually explain this relationship. Therefore, this analysis attempts to offer novel information on this issue, revealing that the conclusions obtained for the complete set of 123 countries are not necessarily the same as those obtained for each homogeneous group of countries when analyzed individually.

Given the nature of the variables considered in this work, specifically, regarding tourism, it is expected that a shock taking place in one country may be transmitted to other countries. Therefore, we first analyze the dependency between countries, since this may lead to biases (Pesaran, 2006 ). The Pesaran cross-sectional dependence test (2004) is used for the total sample and for each of the three groups individually.

First, a dependence analysis is performed for the countries of the sample, verifying the existence of dependence between the panel subjects. A cross-sectional dependence test (Pesaran, 2004 ) is used, first for the overall set of countries in the sample and second, for each of the groups of countries sharing homogeneous characteristics.

The results are presented in Table 4 , indicating that the test is statistically significant for the two variables, both for all of the countries in the sample and for each of the homogeneous country clusters, for the variables taken in logarithms as well as their first differences.

Upon rejecting the null hypothesis of non-cross-sectional dependence, it is assumed that a shock occurs in a country that may be transmitted to other countries in the sample. In fact, the lack of dependence between the variables, both tourism and development, is natural in this type of variables, given the economic cycle through the globalization of the economic activity, common regions visited by tourists, the spillover effect, etc.

Second, the stationary nature of the series is tested, given that cross-sectional dependence has been detected between the variables. First-generation tests may present certain biases in the rejection of the null hypothesis since first-generation unit root tests do not permit the inclusion of dependence between countries (Pesaran, 2007 ). On the other hand, second-generation tests permit the inclusion of dependence and heterogeneity. Therefore, for this analysis, the augmented IPS test (CIPS) proposed by Pesaran ( 2007 ) is used. This second-generation unit root test is the most appropriate for this case, given the cross-sectional dependence.

The results are presented in Table 5 , showing the statistics of the CIPS test for both the overall set of countries in the sample and in each of the homogeneous clusters of countries. The results are presented for models with 1, 2, and 3 delays, considering both the variables in the logarithm and their first differences.

As observed, the null hypothesis of unit root is not rejected for the variables in levels, but it is rejected for the first differences. This result is found in all of the cases, for both the total sample and for each of the homogeneous groups, with a significance of 1%. Therefore, the variables are stationary in their first differences, that is, the variables are integrated at order 1. Given that the causality test requires stationary variables, in this work it is used with the variation or growth rate of the variables, that is, the variable at t minus the variable at t−1.

Finally, to analyze Granger’s causality, the test by Dumitrescu and Hurlin ( 2012 ) is used. This test is used to analyze the causal relationship in both directions; that is, whether tourism contributes to economic development and whether the economic development level conditions tourism specialization. Statistics are calculated considering models with 1, 2, and 3 delays. Considering that cross-sectional dependence exists, the p-values are corrected using bootstrap techniques (making 500 replications). Given that the test requires stationary variables, primary differences of both variables were considered.

Table 6 presents the result of the Granger causality analysis using the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012), considering the null hypothesis that tourism does not condition development level, either for all of the countries or for each homogeneous country cluster.

For the entire sample of countries, the results suggest that the null hypothesis of no causality from tourism to development was rejected when considering 3 delays (in other works analyzing the relationship between tourism and development, the null hypothesis was rejected with a similar level of delay: Rivera ( 2017 ) when considering 3–4 delays or Ulrich et al. ( 2018 ) when considering 3 delays). This suggests that for the entire panel, one-way causality exists whereby tourism influences economic development, demonstrating that tourism specialization contributes positively to improving the economic development of countries opting for tourism development. This is in line with the results of Meyer and Meyer ( 2016 ), Ridderstaat et al. ( 2016 ); Biagi et al. ( 2017 ); Fahimi et al. ( 2018 ); Tan et al. ( 2019 ), or Boonyasana and Chinnakum ( 2020 ).

However, the previous conclusion is very general, given that it is based on a very large sample of countries. Therefore, it may be erroneous to generalize that tourism is a tool for development. In fact, the results indicate that, when analyzing causality by homogeneous groups of countries, sharing similar dynamics in both tourism and development, the null hypothesis of no causality from tourism to development is only rejected for the group C countries, when considering three delays. Therefore, the development of generalized policies to expand tourism in order to improve the socioeconomic conditions of any destination type should consider that this relationship between tourism and economic development does not occur in all cases. Thus, it should first be determined if the countries opting for this activity have certain characteristics that will permit a positive relationship between said variables.

In other words, it may be a mistake to generalize that tourism contributes to economic development for all countries, even though a causal relationship exists for the entire panel. Instead, it should be understood that tourism permits an improvement in the level of development only in certain countries, in line with the results of Cárdenas-García et al. ( 2015 ) or Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ). In this specific work, this positive relationship between tourism and development only occurs in countries from group C, which are characterized by a low level of tourism specialization and a low level of development. Some works have found similar results for countries from group C. For example, Sharma et al. ( 2020 ) found the same relationship for India, while Nonthapot ( 2014 ) had similar findings for certain countries in Asia and the Pacific, which also made up group C. Some recent works have analyzed the relationship between tourism specialization and economic growth, finding similar results. This has been the case with Albaladejo et al. ( 2023 ), who found a relationship from tourism to economic growth only for countries where income is low, and the tourism sector is not yet developed.

These countries have certain limitations since even when tourism contributes to improved economic development, their low levels of tourism specialization do not allow them to reach adequate host population socioeconomic conditions. Therefore, investments in tourism are necessary there in order to increase tourism specialization levels. This increase in tourism may allow these countries to achieve development levels that are similar to other countries having better population conditions.

Therefore, in this group, consisting of 43 countries, a causal relationship exists, given that these countries are characterized by a low level of tourism specialization. However, the weakness of this activity, due to its low relevance in the country, prevents it from increasing the level of economic development. In these countries (details of these countries can be found in Table 3 , specifically, the countries included in Group C), policymakers have to develop policies to improve tourism infrastructure as a prior step to improving their levels of development.

On the other hand, in Table 7 , the results of Granger’s causal analysis based on the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test (2012) are presented, considering the null hypothesis that development level does not condition an increase in tourism, both in the overall sample set and in each of the homogeneous country clusters.

The results indicate that, for the entire country sample, the null hypothesis of no causality from development to tourism is not rejected, for any type of delay. This suggests that, for the entire panel, one-way causality does not exist, with level of development influencing the level of tourism specialization. This is in line with the results of Croes et al. ( 2021 ) in a specific analysis in Poland.

Once again, this conclusion is quite general, given that it has been based on a very broad sample of countries. Therefore, it may be erroneous to generalize that the development level does not condition tourism specialization. Past studies using a large panel of countries, such as the work of Chattopadhyay et al. ( 2022 ) analyzing panel data from 133 countries, have been generalized to all of the analyzed countries, suggesting that economic development level does not condition the arrival of tourists to the destination, although, in fact, this relationship may only exist in specific countries within the analyzed panel.

In fact, the results indicate that, when analyzing causality by homogeneous country groups sharing a similar dynamic, for both tourism and development, the null hypothesis of no causality from development to tourism is only rejected for country group A when considering 2–3 delays. Although the statistics of the test differ, when the sample’s time frame is small, as in this case, the Z-bar tilde statistic is more appropriate.

Thus, development level influences tourism growth in Group A countries, which are characterized by a high level of development and tourism specialization, in accordance with the prior results of Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García ( 2021 ).

These results, suggesting that tourism is affected by economic development level, but only in the most developed countries, imply that the existence of better socioeconomic conditions in these countries, which tend to have better healthcare systems, infrastructures, levels of human resource training, and security, results in an increase in tourist arrivals to these countries. In fact, when traveling to a specific tourist destination, if this destination offers attractive factors and a higher level of economic development, an increase in tourist flows was fully expected.

In this group, consisting of 36 countries, the high development level, that is, the proper provision of socio-economic factors in their economic foundations (training, infrastructures, safety, health, etc.) has led to the attraction of a large number of tourists to their region, making their countries having high tourism specialization.

Although international organizations have recognized the importance of tourism as an instrument of economic development, based on the theoretical relationship between these two variables, few empirical studies have considered the consequences of the relationship between tourism and development.

Furthermore, some hasty generalizations have been made regarding the analysis of this relationship and the analysis of the relationship of tourism with other economic variables. Oftentimes, conclusions have been based on heterogeneous panels containing large numbers of subjects. This may lead to erroneous results interpretation, basing these results on the entire panel when, in fact, they only result from specific panel units.

Given this gap in the scientific literature, this work attempts to analyze the relationship between tourism and economic development, considering the panel data in a complete and separate manner for each of the previously identified country groups.

The results highlight the need to adopt economic policies that consider the uniqueness of each of the countries that use tourism as an instrument to improve their socioeconomic conditions, given that the results differ according to the specific characteristics of the analyzed country groups.

This work provides precise results regarding the need for policymakers to develop public policies to ensure that tourism contributes to the improvement of economic development, based on the category of the country using this economic activity to achieve greater levels of economic development.

Specifically, this work has determined that tourism contributes to economic development, but only in countries that previously had a lower level of tourism specialization and were less developed. This highlights the need to invest in tourism to attract more tourists to these countries to increase their economic development levels. Countries having major natural attraction resources or factors, such as the Dominican Republic, Egypt, India, Morocco, and Vietnam, need to improve their positioning in the international markets in order to attain a higher level of tourism specialization, which will lead to improved development levels.

Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that a greater past economic development level of a country will help attract more tourists to these countries, highlighting the need to invest in security, infrastructures, and health in order for these destinations to be considered attractive and increase tourist arrival. In fact, given their increased levels of development, countries such as Spain, Greece, Italy, Qatar, and Uruguay have become attractive to tourists, with soaring numbers of visitors and high levels of tourism specialization.

Therefore, the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development should focus on the differentiated treatment of countries in terms of their specific characteristics, since working with panel data with large samples and heterogenous characteristics may lead to incorrect results generalizations to all of the analyzed destinations, even though the obtained relationship in fact only takes place in certain countries of the sample.

Conclusions and policy implications

Within this context, the objective of this study is twofold: on the one hand, it aims to contribute to the lack of empirical works analyzing the causal relationship between tourism and economic development using Granger’s causality analysis for a broad sample of countries from across the globe. On the other hand, it critically examines the use of causality analysis in heterogeneous samples, by verifying that the results for the panel set differ from the results obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups in terms of tourism specialization and development level.

In fact, upon analyzing the causal relationship from tourism to development, and the causal relationship from development to tourism, the results from the entire panel, consisting of 123 countries, differ from those obtained when analyzing causality by homogeneous country groups, in terms of tourism specialization and economic development dynamics of these countries.

On the one hand, a one-way causality relationship is found to exist, whereby tourism influences economic development for the entire sample of countries, although this conclusion cannot be generalized, since this relationship is only explained by countries belonging to Group C (countries with low levels of tourism specialization and low development levels). This indicates that, although a causal relationship exists by which tourism contributes to economic development in these countries, the low level of tourism specialization does not permit growth to appropriate development levels.

The existence of a causal relationship whereby the increase in tourism precedes the improvement of economic development in this group of countries having a low level of tourism specialization and economic development, suggests the appropriateness of the focus by distinct international organizations, such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development or the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, on funding tourism projects (through the provision of tourism infrastructure, the stimulation of tourism supply, or positioning in international markets) in countries with low economic development levels. This work has demonstrated that investment in tourism results in the attracting of a greater flow of tourists, which will contribute to improved economic development levels.

Therefore, both international organizations financing projects and public administrations in these countries should increase the funding of projects linked to tourism development, in order to increase the flow of tourism to these destinations. This, given that an increase in tourism specialization suggests an increased level of development due to the demonstrated existence of a one-way causal relationship from tourism to development in these countries, many of which form part of the group of so-called “least developed” countries. However, according to the results obtained in this work, this relationship is not instantaneous, but rather, a certain delay exists in order for economic development to improve as a result of the increase in tourism. Therefore, public managers must adopt a medium and long-term vision of tourism activity as an instrument of development, moving away from short-term policies seeking immediate results, since this link only occurs over a broad time horizon.

On the other hand, this study reveals that a one-way causal relationship does not exist, by which the level of development influences tourism specialization level for the entire sample of countries. However, this conclusion, once again, cannot be generalized given that in countries belonging to Group A (countries with a high development level and a high tourism specialization level), a high level of economic development determines a higher level of tourism specialization. This is because the socio-economic structure of these countries (infrastructures, training or education, health, safety, etc.) permits their shaping as attractive tourist destinations, thereby increasing the number of tourists visiting them.

Therefore, investments made by public administrations to improve these factors in other countries that currently do not display this causal relationship implies the creation of the necessary foundations to increase their tourism specialization and, therefore, as shown in other works, tourism growth will permit economic growth, with all of the associated benefits for these countries.

Therefore, to attract tourist flows, it is not only important for a country to have attractive factors or resources, but also to have an adequate level of prior development. In other words, the tourists should perceive an adequate level of security in the destination; they should be able to use different infrastructures such as roads, airports, or the Internet; and they should receive suitable services at the destination from personnel having an appropriate level of training. The most developed countries, which are the destinations having the greatest endowment of these resources, are the ones that currently receive the most tourist flows thanks to the existence of these factors.

Therefore, less developed countries that are committed to tourism as an instrument to improve economic development should first commit to the provision of these resources if they hope to increase tourist flows. If this increase in tourism takes place in these countries, their economic development levels have been demonstrated to improve. However, since these countries are characterized by low levels of resources, cooperation by organizations financing the necessary investments is key to providing them with these resources.

Thus, a critical perspective is necessary when considering the relationship between tourism and economic development based on global causal analysis using heterogeneous samples with numerous subjects. As in this case, carrying out analyses on homogeneous groups may offer interesting results for policymakers attempting to suitably manage population development improvements due to tourism growth and tourism increases resulting from higher development levels.

One limitation of this work is its national scope since evidence suggests that tourism is a regional and local activity. Therefore, it may be interesting to apply this same approach on a regional level, using previously identified homogeneous groups.

And given that the existence of a causal relationship (in either direction) between tourism and development has only been determined for a specific set of countries, future works could consider other country-specific factors that may determine this causal relationship, in addition to the dynamics of tourism specialization and development level.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ahmad N, Menegaki AN, Al-Muharrami S (2020) Systematic literature review of tourism growth nexus: An overview of the literature and a content analysis of 100 most influential papers. J Econ Surv 34(5):1068–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12386

Article Google Scholar

Albaladejo I, Brida G, González M y Segarra V (2023) A new look to the tourism and economic growth nexus: a clustering and panel causality analysis. World Econ https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13459

Alcalá-Ordóñez A, Brida JG, Cárdenas-García PJ (2023) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been confirmed? Evidence from an updated literature review. Curr Issues Tour https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2023.2272730

Alcalá-Ordóñez A, Segarra V (2023) Tourism and economic development: a literature review to highlight main empirical findings. Tour Econom https://doi.org/10.1177/13548166231219638

Ashley C, De Brine P, Lehr A, Wilde H (2007) The role of the tourism sector in expanding economic opportunity. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge MA

Google Scholar

Biagi B, Ladu MG, Royuela V (2017) Human development and tourism specialization. Evidence from a panel of developed and developing countries. Int J Tour Res 19(2):160–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2094

Badulescu D, Simut R, Mester I, Dzitac S, Sehleanu M, Bac DP, Badulescu A (2021) Do economic growth and environment quality contribute to tourism development in EU countries? A panel data analysis. Technol Econom Dev Econ 27(6):1509–1538. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2021.15781

Bojanic DC, Lo M (2016) A comparison of the moderating effect of tourism reliance on the economic development for islands and other countries. Tour Manag 53:207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.10.00

Bolwell D, Weinz W (2011) Poverty reduction through tourism. International Labour Office, Geneva

Boonyasana P, Chinnakum W (2020) Linkages among tourism demand, human development, and CO 2 emissions in Thailand. Abac J 40(3):78–98

Brida JG, Cárdenas-García PJ, Segarra V (2023) Turismo y Desarrollo Económico: una Exploración Empírica. Red Nacional de Investigadores en Economía (RedNIE), Working Papers, 283

Brida JG, Cortes-Jimenez I, Pulina M (2016) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr Issues Tour 19(5):394–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.868414