Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 March 2023

The benefits of tourism for rural community development

- Yung-Lun Liu 1 ,

- Jui-Te Chiang 2 &

- Pen-Fa Ko 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 137 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

9 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Development studies

While the main benefits of rural tourism have been studied extensively, most of these studies have focused on the development of sustainable rural tourism. The role of tourism contributions to rural community development remains unexplored. Little is known about what tourism contribution dimensions are available for policy-makers and how these dimensions affect rural tourism contributions. Without a clear picture and indication of what benefits rural tourism can provide for rural communities, policy-makers might not invest limited resources in such projects. The objectives of this study are threefold. First, we outline a rural tourism contribution model that policy-makers can use to support tourism-based rural community development. Second, we address several methodological limitations that undermine current sustainability model development and recommend feasible methodological solutions. Third, we propose a six-step theoretical procedure as a guideline for constructing a valid contribution model. We find four primary attributes of rural tourism contributions to rural community development; economic, sociocultural, environmental, and leisure and educational, and 32 subattributes. Ultimately, we confirm that economic benefits are the most significant contribution. Our findings have several practical and methodological implications and could be used as policy-making guidelines for rural community development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Creativity development of tourism villages in Bandung Regency, Indonesia: co-creating sustainability and urban resilience

Eco-tourism, climate change, and environmental policies: empirical evidence from developing economies

Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research

Introduction.

In many countries, rural areas are less developed than urban areas. They are often perceived as having many problems, such as low productivity, low education, and low income. Other issues include population shifts from rural to urban areas, low economic growth, declining employment opportunities, the loss of farms, impacts on historical and cultural heritage, sharp demographic changes, and low quality of life. These issues indicate that maintaining agricultural activities without change might create deeper social problems in rural regions. Li et al. ( 2019 ) analyzed why some rural areas decline while others do not. They emphasized that it is necessary to improve rural communities’ resilience by developing new tourism activities in response to potential urban demands. In addition, to overcome the inevitability of rural decline, Markey et al. ( 2008 ) pointed out that reversing rural recession requires investment orientation and policy support reform, for example, regarding tourism. Therefore, adopting rural tourism as an alternative development approach has become a preferred strategy in efforts to balance economic, social, cultural, and environmental regeneration.

Why should rural regions devote themselves to tourism-based development? What benefits can rural tourism bring to a rural community, particularly during and after the COVID pandemic? Without a clear picture and answers to these questions, policy-makers might not invest limited resources in such projects. Understanding the contributions of rural tourism to rural community development is critical for helping government and community planners realize whether rural tourism development is beneficial. Policy-makers are aware that reducing rural vulnerability and enhancing rural resilience is a necessary but challenging task; therefore, it is important to consider the equilibrium between rural development and potential negative impacts. For example, economic growth may improve the quality of life and enhance the well-being index. However, it may worsen income inequality, increase the demand for green landscapes, and intensify environmental pollution, and these changes may impede natural preservation in rural regions and make local residents’ lives more stressful. This might lead policy-makers to question whether they should support tourism-based rural development. Thus, the provision of specific information on the contributions of rural tourism is crucial for policy-makers.

Recently, most research has focused on rural sustainable tourism development (Asmelash and Kumar, 2019 ; Polukhina et al., 2021 ), and few studies have considered the contributions of rural tourism. Sustainability refers to the ability of a destination to maintain production over time in the face of long-term constraints and pressures (Altieri et al., 2018 ). In this study, we focus on rural tourism contributions, meaning what rural tourism contributes or does to help produce something or make it better or more successful. More specifically, we focus on rural tourism’s contributions, not its sustainability, as these goals and directions differ. Today, rural tourism has responded to the new demand trends of short-term tourists, directly providing visitors with unique services and opportunities to contact other business channels. The impact on the countryside is multifaceted, but many potential factors have not been explored (Arroyo et al., 2013 ; Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). For example, the demand for remote nature-based destinations has increased due to the fear of COVID-19 infection, the perceived risk of crowding, and a desire for low tourist density. Juschten and Hössinger ( 2020 ) showed that the impact of COVID-19 led to a surge in demand for natural parks, forests, and rural areas. Vaishar and Šťastná ( 2022 ) demonstrated that the countryside is gaining more domestic tourists due to natural, gastronomic, and local attractions. Thus, they contended that the COVID-19 pandemic created rural tourism opportunities.

Following this change in tourism demand, rural regions are no longer associated merely with agricultural commodity production. Instead, they are seen as fruitful locations for stimulating new socioeconomic activities and mitigating public mental health issues (Kabadayi et al., 2020 ). Despite such new opportunities in rural areas, there is still a lack of research that provides policy-makers with information about tourism development in rural communities (Petrovi’c et al., 2018 ; Vaishar and Šťastná, 2022 ). Although there are many novel benefits that tourism can bring to rural communities, these have not been considered in the rural community development literature. For example, Ram et al. ( 2022 ) showed that the presence of people with mental health issues, such as nonclinical depression, is negatively correlated with domestic tourism, such as rural tourism. Yang et al. ( 2021 ) found that the contribution of rural tourism to employment is significant; they indicated that the proportion of nonagricultural jobs had increased by 99.57%, and tourism in rural communities had become the leading industry at their research site in China, with a value ten times higher than that of agricultural output. Therefore, rural tourism is vital in counteracting public mental health issues and can potentially advance regional resilience, identity, and well-being (López-Sanz et al., 2021 ).

Since the government plays a critical role in rural tourism development, providing valuable insights, perspectives, and recommendations to policy-makers to foster sustainable policies and practices in rural destinations is essential (Liu et al., 2020 ). Despite the variables developed over time to address particular aspects of rural tourism development, there is still a lack of specific variables and an overall measurement framework for understanding the contributions of rural tourism. Therefore, more evidence is needed to understand how rural tourism influences rural communities from various structural perspectives and to prompt policy-makers to accept rural tourism as an effective development policy or strategy for rural community development. In this paper, we aim to fill this gap.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: the section “Literature review” presents the literature review. Our methodology is described in the section “Methodology”, and our results are presented in the section “Results”. Our discussion in the section “Discussion/implications” places our findings in perspective by describing their theoretical and practical implications, and we provide concluding remarks in the section “Conclusion”.

Literature review

The role of rural tourism.

The UNWTO ( 2021 ) defined rural tourism as a type of tourism in which a visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activity, agriculture, rural lifestyle/culture, angling, and sightseeing. Rural tourism has been used as a valid developmental strategy in rural areas in many developed and developing countries. This developmental strategy aims to enable a rural community to grow while preserving its traditional culture (Kaptan et al., 2020 ). In rural areas, ongoing encounters and interactions between humans and nature occur, as well as mutual transformations. These phenomena take place across a wide range of practices that are spatially and temporally bound, including agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, farm tourism, cultural heritage preservation, and country life (Hegarty and Przezbórska, 2005 ). To date, rural tourism in many places has become an important new element of the regional rural economy; it is increasing in importance as both a strategic sector and a way to boost the development of rural regions (Polukhina et al., 2021 ). Urban visitors’ demand for short-term leisure activities has increased because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Slater, 2020 ). Furthermore, as tourists shifted their preferences from exotic to local rural tourism amid COVID-19, Marques et al. ( 2022 ) suggested that this trend is a new opportunity that should be seized, as rural development no longer relies on agriculture alone. Instead, other practices, such as rural tourism, have become opportunities for rural areas. Ironically, urbanization has both caused severe problems in rural areas and stimulated rural tourism development as an alternative means of economic revitalization (Lewis and Delisle, 2004 ). Rural tourism provides many unique events and activities that people who live in urban areas are interested in, such as agricultural festivals, crafts, historical buildings, natural preservation, nostalgia, cuisine, and opportunities for family togetherness and relaxation (Christou, 2020 ; Getz, 2008 ). As rural tourism provides visitors from urban areas with various kinds of psychological, educational, social, esthetic, and physical satisfaction, it has brought unprecedented numbers of tourists to rural communities, stimulated economic growth, improved the viability of these communities, and enhanced their living standards (Nicholson and Pearce, 2001 ). For example, rural tourism practitioners have obtained significant economic effects, including more income, more direct sales, better profit margins, and more opportunities to sell agricultural products or craft items (Everett and Slocum, 2013 ). Local residents can participate in the development of rural tourism, and it does not necessarily depend on external resources. Hence, it provides entrepreneurial opportunities (Lee et al., 2006 ). From an environmental perspective, rural tourism is rooted in a contemporary theoretical shift from cherishing local agricultural resources to restoring the balance between people and ecosystems. Thus, rural land is preserved, natural landscapes are maintained, and green consumerism drives farmers to focus on organic products, green chemistry, and value-added products, such as land ethics (Higham and Ritchie, 2001 ). Therefore, the potential contributions of rural tourism are significant and profound (Marques, 2006 ; Phillip et al., 2010 ). Understanding its contributions to rural community development could encourage greater policy-maker investment and resident support (Yang et al., 2010 ).

Contributions of rural tourism to rural community development

Maintaining active local communities while preventing the depopulation and degradation of rural areas requires a holistic approach and processes that support sustainability. What can rural tourism contribute to rural development? In the literature, rural tourism has been shown to bring benefits such as stimulating economic growth (Oh, 2005 ), strengthening rural and regional economies (Lankford, 1994 ), alleviating poverty (Zhao et al., 2007 ), and improving living standards in local communities (Uysal et al., 2016 ). In addition to these economic contributions, what other elements have not been identified and discussed (Su et al., 2020 )? To answer these questions, additional evidence is a prerequisite. Thus, this study examines the following four aspects. (1) The economic perspective: The clustering of activities offered by rural tourism stimulates cooperation and partnerships between local communities and serves as a vehicle for creating various economic benefits. For example, rural tourism improves employment opportunities and stability, local residents’ income, investment, entrepreneurial opportunities, agricultural production value-added, capital formation, economic resilience, business viability, and local tax revenue (Atun et al., 2019 ; Cheng and Zhang, 2020 ; Choi and Sirakaya, 2006 ; Chong and Balasingam, 2019 ; Cunha et al., 2020 ). (2) The sociocultural perspective: Rural tourism no longer refers solely to the benefits of agricultural production; through economic improvement, it represents a greater diversity of activities. It is important to take advantage of the novel social and cultural alternatives offered by rural tourism, which contribute to the countryside. For example, rural tourism can be a vehicle for introducing farmers to potential new markets through more interactions with consumers and other value chain members. Under such circumstances, the sociocultural benefits of rural tourism are multifaceted. These include improved rural area depopulation prevention (López-Sanz et al., 2021 ), cultural and heritage preservation, and enhanced social stability compared to farms that do not engage in the tourism business (Ma et al., 2021 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). Additional benefits are improved quality of life; revitalization of local crafts, customs, and cultures; restoration of historical buildings and community identities; and increased opportunities for social contact and exchange, which enhance community visibility, pride, and cultural integrity (Kelliher et al., 2018 ; López-Sanz et al., 2021 ; Ryu et al., 2020 ; Silva and Leal, 2015 ). (3) The environmental perspective: Many farms in rural areas have been rendered noncompetitive due to a shortage of labor, poor managerial skills, and a lack of financial support (Coria and Calfucura, 2012 ). Although there can be immense pressure to maintain a farm in a family and to continue using land for agriculture, these problems could cause families to sell or abandon their farms or lands (Tew and Barbieri, 2012 ). In addition, unless new income pours into rural areas, farm owners cannot preserve their land and its natural aspects; thus, they tend to allow their land to become derelict or sell it. In the improved economic conditions after farms diversify into rural tourism, rural communities have more money to provide environmental care for their natural scenic areas, pastoral resources, forests, wetlands, biodiversity, pesticide mitigation, and unique landscapes (Theodori, 2001 ; Vail and Hultkrantz, 2000 ). Ultimately, the entire image of a rural community is affected; the community is imbued with vitality, and farms that participate in rural tourism instill more togetherness among families and rural communities. In this study, the environmental benefits induced by rural tourism led to improved natural environmental conservation, biodiversity, environmental awareness, infrastructure, green chemistry, unspoiled land, and family land (Di and Laura, 2021 ; Lane, 1994 ; Ryu et al., 2020 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). (4) The leisure and educational perspective: Rural tourism is a diverse strategy associated with an ongoing flow of development models that commercialize a wide range of farming practices for residents and visitors. Rural territories often present a rich set of unique resources that, if well managed, allow multiple appealing, authentic, and memorable tourist experiences. Tourists frequently comment that the rural tourism experience positively contrasts with the stress and other negatively perceived conditions of daily urban life. This is reflected in opposing, compelling images of home and a visited rural destination (Kastenholz et al., 2012 ). In other words, tourists’ positive experiences result from the attractions and activities of rural tourism destinations that may be deemed sensorially, symbolically, or socially opposed to urban life (Kastenholz et al. 2018 ). These experiences are associated with the “search for authenticity” in the context of the tension between the nostalgic images of an idealized past and the demands of stressful modern times. Although visitors search for the psychological fulfillment of hedonic, self-actualization, challenge, accomplishment, exploration, and discovery goals, some authors have uncovered the effects of rural tourism in a different context. For example, Otto and Ritchie ( 1996 ) revealed that the quality of a rural tourism service provides a tourist experience in four dimensions—hedonic, peace of mind, involvement, and recognition. Quadri-Felitti and Fiore ( 2013 ) identified the relevant impact of education, particularly esthetics, versus memory on satisfaction in wine tourism. At present, an increasing number of people and families are seeking esthetic places for relaxation and family reunions, particularly amid COVID-19. Rural tourism possesses such functions; it remains a novel phenomenon for visitors who live in urban areas and provides leisure and educational benefits when visitors to a rural site contemplate the landscape or participate in an agricultural process for leisure purposes (WTO, 2020 ). Tourists can obtain leisure and educational benefits, including ecological knowledge, information about green consumerism, leisure and recreational opportunities, health and food security, reduced mental health issues, and nostalgia nurturing (Alford and Jones, 2020 ; Ambelu et al., 2018 ; Christou, 2020 ; Lane, 1994 ; Li et al., 2021 ). These four perspectives possess a potential synergy, and their effects could strengthen the relationship between rural families and rural areas and stimulate new regional resilience. Therefore, rural tourism should be understood as an enabler of rural community development that will eventually attract policy-makers and stakeholders to invest more money in developing or advancing it.

Methodology

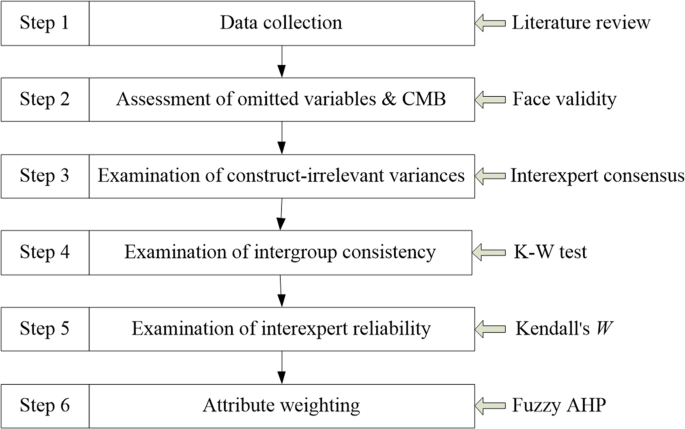

The literature on rural tourism provides no generally accepted method for measuring its contributions or sustainability intensity. Although many statistical methods are available, several limitations remain, particularly in terms of the item generation stage and common method bias (CMB). For example, Marzo-Navar et al. ( 2015 ) used the mean and SD values to obtain their items. However, the use of the mean has been criticized because it is susceptible to extreme values or outliers. In addition, they did not examine omitted variables and CMB. Asmelash and Kumar ( 2019 ) used the Delphi method with a mean value for deleting items. Although they asked experts to suggest the inclusion of any missed variables, they did not discuss these results. Moreover, they did not assess CMB. Islam et al. ( 2021 ) used a sixteen-step process to formulate sustainability indicators but did not consider omitted variables, a source of endogeneity bias. They also did not designate a priority for each indicator. Although a methodologically sound systematic review is commonly used, little attention has been given to reporting interexpert reliability when multiple experts are used to making decisions at various points in the screening and data extraction stages (Belur et al., 2021 ). Due to the limitations of the current methods for assessing sustainable tourism development, we aim to provide new methodological insights. Specifically, we suggest a six-stage procedure, as shown in Fig. 1 .

Steps required in developing the model for analysis after obtaining the data.

Many sources of data collection can be used, including literature reviews, inferences about the theoretical definition of the construct, previous theoretical and empirical research on the focal construct, advice from experts in the field, interviews, and focus groups. In this study, the first step was to retrieve data from a critical literature review. The second step was the assessment of omitted variables to produce items that fully captured all essential aspects of the focal construct domain. In this case, researchers must not omit a necessary measure or fail to include all of the critical dimensions of the construct. In addition, the stimuli of CMB, for example, double-barreled items, items containing ambiguous or unfamiliar terms, and items with a complicated syntax, should be simplified and made specific and concise. That is, researchers should delete items contaminated by CMB. The third step was the examination of construct-irrelevant variance to retain the variances relevant to the construct of interest and minimize the extent to which the items tapped concepts outside the focal construct domain. Variances irrelevant to the targeted construct should be deleted. The fourth step was to examine intergroup consistency to ensure that there was no outlier impact underlying the ratings. The fifth step was to examine interexpert reliability to ensure rating conformity. Finally, we prioritized the importance of each variable with the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (AHP), which is a multicriteria decision-making approach. All methods used in this study are expert-based approaches.

Selection of experts

Because this study explores the contributions of rural tourism to rural community development, it involves phenomena in the postdevelopment stage; therefore, a few characteristics are essential for determining the choice of experts. The elements used to identify the experts in this study were (1) the number of experts, (2) expertise, (3) knowledge, (4) diversity, (5) years working in this field, and 5) commitment to participation. Regarding the number of experts, Murphy-Black et al. ( 1998 ) suggested that the more participants there are, the better, as a higher number reduces the effects of expert attrition and rater bias. Taylor-Powell ( 2002 ) pointed out that the number of participants in an expert-based study depends not only on the purpose of the research but also on the diversity of the target population. Okoli and Pawlowski ( 2004 ) recommended a target number of 10–18 experts for such a purpose. Therefore, we recruited a group of 18 experts based on their stated interest in the topic and asked them to comment on our rationale concerning the rating priorities among the items. We asked them to express a degree of agreement or disagreement with each item we provided. We adopted a heterogeneous and anonymous arrangement to ensure that rater bias did not affect this study. The 18 experts had different backgrounds, which might have made it easier for them to reach a consensus objectively. We divided the eighteen experts into three subgroups: (1) at least six top managers from rural tourism businesses, all of whom had been in the rural tourism business for over 10 years; (2) at least six academics who taught subjects related to tourism at three different universities in Taiwan; and (3) at least six government officials involved in rural development issues in Taiwan.

Generating items to represent the construct

Step 1: data collection.

Data collection provides evidence for investigation and reflects the construct of interest. While there is a need to know what rural tourism contributes, previous studies have provided no evidence for policy-makers to establish a rural community strategy; thus, it is essential to use a second source to achieve this aim. We used a literature review for specific topics; the data we used were based on the findings being presented in papers on rural tourism indexed in the SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index) and SCIE (Science Citation Index Expanded). In this study, we intended to explore the role of rural tourism and its contributions to rural development. Therefore, we explored the secondary literature on the state of the questions of rural development, sustainable development, sustainability indicators, regional resilience, farm tourism, rural tourism, COVID-19, tourist preferences, and ecotourism using terms such as land ethics, ecology, biodiversity, green consumerism, environmentalism, green chemistry, community identity, community integration, community visibility, and development goals in an ad hoc review of previous studies via Google Scholar. Based on the outcomes of this first data collection step, we generated thirty-three subattributes and classified them into four domains.

Step 2: Examine the face validity of omitted variables and CMB

Face validity is defined as assessing whether a measurement scale or questionnaire includes all the necessary items (Dempsey and Dempsey, 1992 ). Based on the first step, we generated data subattributes from our literature review. However, there might have been other valuable attributes or subattributes that were not considered or excluded. Therefore, our purposes for examining face validity were twofold. First, we assessed the omitted variables, defined as the occurrence of crucial aspects or facets that were omitted (Messick, 1995 ). These comprise a threat to construct validity that, if ignored by researchers, might result in unreliable findings. In other words, face validity is used to distinguish whether the researchers have adequately captured the full dimensions of the construct of interest. If not, the evaluation instrument or model is deficient. However, the authors found that most rural tourism studies have not assessed the issue of omitted variables (An and Alarcon, 2020 ; Lin, 2022 ). Second, we mitigated the CMB effect. In a self-report survey, it is necessary to provide a questionnaire without CMB to the targeted respondents, as CMB affects respondent comprehension. Therefore, we assessed item characteristic effects, item context effects, and question response process effects. These three effects are related to the respondents’ understanding, retrieval, mood, affectivity, motivation, judgment, response selection, and response reporting (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). Specifically, items containing flaws from these three groups in a questionnaire can seriously influence an empirical investigation and potentially result in misleading conclusions. We assessed face validity by asking all the experts to scrutinize the content items that we collected from the literature review and the questionnaire that we drafted. The experts could then add any attribute or subattribute they thought was essential that had been omitted. They could also revise the questionnaire if CMB were embedded. We added the new attributes or subattributes identified by the experts to those collected from the literature review.

Step 3: Examine interexpert consensus for construct-irrelevant variances

After examining face validity, we needed to rule out items irrelevant to the construct of interest; otherwise, the findings would be invalid. We examined the interexpert consensus to achieve this aim. The purpose was to estimate the experts’ ratings of each item. In other words, interexpert consensus assesses the extent to which experts make the same ratings (Kozlowski and Hattrup, 1992 ; Northcote et al., 2008 ). In prior studies, descriptive statistics have often been used to capture the variability among individual characteristics, responses, or contributions to the subject group (Landeta, 2006 ; Roberson et al., 2007 ). Many expert-based studies have applied descriptive statistics to determine consensus and quantify its degree (Paraskevas and Saunders, 2012 ; Stewart et al., 2016 ). Two main groups of descriptive statistics, central tendencies (mode, mean, and median) and level of dispersion (standard deviation, interquartile, and coefficient of variation), are commonly used when determining consensus (Mukherjee et al., 2015 ). Choosing the cutoff point of interexpert consensus was critical because we used it as a yardstick for item retention and its value can also be altered by a number on the Likert scale (Förster and von der Gracht, 2014 ). In the case of a 5-point Likert scale, the coefficient of variation (CV) is used to measure interexpert consensus. Hence, CV ≤ 0.3 indicated high consensus (Zinn et al., 2001 ). In addition, based on the feedback obtained from the expert panel, we used standard deviation (SD) as another measurement to assess the variation in our population. Henning and Jordaan ( 2016 ) indicate that SD ≤ 1 represents a high level of consensus, meaning that it can act as a guideline for cutoff points. In addition, following Vergani et al. ( 2022 ), we used the percentage agreement (% AGR) to examine interexpert consensus. If the responses reached ≧ 70% 4 and 5 in the case of a 5-point Likert scale, it indicated that the item had interexpert consensus; thus, we could retain it. Moreover, to avoid the impact of outliers, we used the median instead of the mean as another measurement. Items had a high consensus if their median value was ≥4.00 (Rice, 2009 ). Considering these points, we adopted % AGR, median, SD, and CV to examine interexpert consensus.

Step 4: Examine intergroup consistency

In this expert-based study, the sample size was small. Any rater bias could have caused inconsistency among the subgroups of experts; therefore, we needed to examine the effect of rater bias on intergroup consistency. When the intergroup ratings showed substantially different distributions, the aggregated data were groundless. Dajani et al. ( 1979 ) remarked that interexpert consensus is meaningless if the consistency of responses in a study is not reached, as it means that any rater bias could distort the median, SD, or CV. Most studies have used one-way ANOVA to determine whether there is a significant difference between the expected and observed frequency in three or more categories. However, this method is based on large sample size and normal distribution. In the case of expert-based studies, the expert sample size is small, and the assessment distribution tends to be skewed. Thus, we used the nonparametric test instead of one-way ANOVA for consistency measurement (Potvin and Roff, 1993 ). We used the Kruskal‒Wallis test (K–W) to test the intergroup consistency among the three subgroups of experts. The purpose of the K–W test is to determine whether there are significant differences among three or more subgroups regarding the ratings of the domains (Huck, 2004 ). The judgment criteria in the K-W test depended on the level of significance, and we set the significance level at p < 0.05 (Love and Irani, 2004 ), with no significant differences among groups set at p > 0.05 (Loftus et al., 2000 ; Rice, 2009 ). We used SPSS to conduct the K–W test to assess intergroup consistency in this study.

Step 5: Examine interexpert reliability

Interexpert reliability, on the one hand, is usually defined as the proportion of systematic variance to the total variance in ratings (James et al., 1984 ). On the other hand, interexpert reliability estimation is not concerned with the exact or absolute value of ratings. Rather, it measures the relative ordering or ranking of rated objects. Thus, interexpert reliability estimation concerns the consistency of ratings (Tinsley and Weiss, 1975 ). If an expert-based study did not achieve interexpert reliability, we could not trust its analysis (Singletary, 1994 ). Thus, we examined interexpert reliability in this expert-based study. Many methods are available in the literature for measuring interexpert reliability, but there seems to be little consensus on a standard method. We used Kendall’s W to assess the reliability among the experts for each sample group (Goetz et al., 1994 ) because it was available for any sample size or ordinal number. If W was 1, all the experts were unanimous, and each had assigned the same order to the list of objects or concerns. As Spector et al. ( 2002 ) and Schilling ( 2002 ) suggested, reliabilities well above the recommended value of .70 indicate sufficient internal reliability. In this study, there was a strong consensus when W > 0.7. W > 0.5 represented a moderate consensus; and W < 0.3 indicated weak interexpert agreement (Schmidt et al., 2001 ). To measure Kendall’s W , we used SPSS 23 to assess interexpert reliability.

Step 6: Examine the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process

After examining face validity, interexpert consensus, intergroup consistency, and interexpert reliability, we found that the aggregated items were relevant, authentic, and reliable in relation to the construct of interest. To provide policy-makers with a clear direction regarding which contributions are more or less important, we scored each attribute and subattribute using a multicriteria decision-making technique. Fuzzy AHP is a well-known decision-making tool for modeling unstructured problems. It enables decision-makers to model a complex issue in a hierarchical structure that indicates the relationships between the goal, criteria, and subcriteria on the basis of scores (Park and Yoon, 2011 ). The fuzzy AHP method tolerates vagueness and ambiguity (Mikhailov and Tsvetinov, 2004 ). In other words, fuzzy AHP can capture a human’s appraisal of ambiguity when considering complex, multicriteria decision-making problems (Erensal et al., 2006 ). In this study, we used Power Choice 2.5 software to run fuzzy AHP, determine weights, and develop the impact structure of rural tourism on sustainable rural development.

Face validity

To determine whether we had omitted variables, we asked all 18 experts to scrutinize our list of four attributes and 33 subattributes for omitted variables and determine whether the questionnaire contained any underlying CMB. We explained the meaning of omitted variables, the stimuli of CMB, and the two purposes of examining face validity to all the experts. In their feedback, the eighteen experts added one item as an omitted variable: business viability. The experts suggested no revisions to the questionnaire we had drafted. These results indicated that one omitted variable was revealed and that our prepared questionnaire was clear, straightforward, and understandable. The initially pooled 34 subattributes represented the construct of interest, and all questionnaires used for measurement were defendable in terms of CMB. The biasing effects of method variance did not exist, indicating that the threat of CMB was minor.

Interexpert consensus

In this step, we rejected any items irrelevant to the construct of interest. Consensus measurement played an essential role in aggregating the experts’ judgments. This study measured the AGR, median, SD, and CV. Two items, strategic alliance (AGR = 50%) and carbon neutrality (AGR = 56%) were rated < 70%, and we rejected them accordingly. These results are shown in Table 1 . The AGR, median, SD, and CV values were all greater than the cutoff points, thus indicating that the majority of experts in this study consistently recognized high values and reached a consensus for the rest of the 32 subattributes. Consequently, the four attributes and 32 subattributes remained and were initially identified as determinants for further analysis.

Intergroup consistency and interexpert reliability

In this study, with scores based on a 5-point Likert scale, we conducted the K–W test to assess intergroup differences for each subattribute. Based on the outcomes, the K–W test yielded significant results for all 32 subattributes; all three groups of experts reached consistency at p > 0.05. This result indicated that no outlier or extreme value underlay the ratings, and therefore, intergroup consistency was reached. Finally, we measured interexpert reliability with Kendall’s W . The economic perspective was W = 0.73, the sociocultural perspective was W = 0.71, the environmental perspective was W = 0.71, and the leisure and educational perspective was W = 0.72. These four groups of W were all ≧ 0.7, indicating high reliability for the ranking order and convergence judged by all subgroup experts. These results are shown in Table 2 .

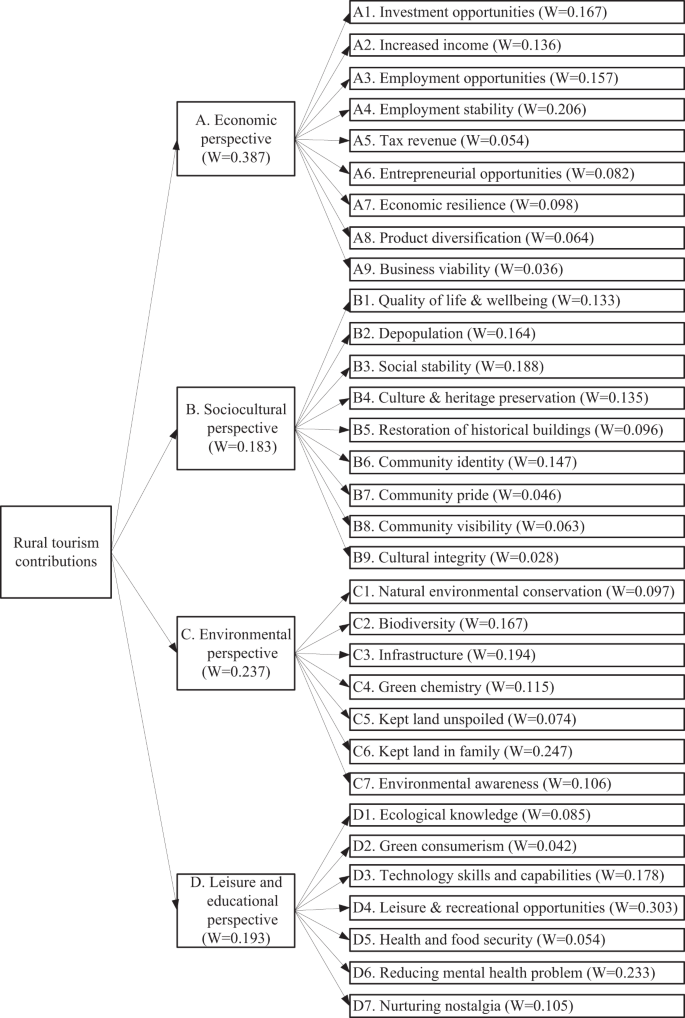

The hierarchical framework

The results of this study indicate that rural tourism contributions to rural community development comprise four attributes and thirty-two subattributes. The economic perspective encompasses nine subattributes and is weighted at w = 0.387. In addition, rural tourism has long been considered a possible means of sociocultural development and regeneration of rural areas, particularly those affected by the decline in traditional rural

activities, agricultural festivals, and historical buildings. According to the desired benefits, the sociocultural perspective encompasses nine subattributes and is weighted at w = 0.183. Moreover, as rural tourism can develop on farms and locally, its contribution to maintaining and enhancing environmental regeneration and protection is significant. Therefore, an environmental perspective can determine rural tourism’s impact on pursuing environmental objectives. Our results indicate that the environmental perspective encompasses seven subattributes and that its weight is w = 0.237. Furthermore, the leisure and educational perspective indicates the attractiveness of rural tourism from visitors’ viewpoint and their perception of a destination’s value and contributions. These results show that this perspective encompasses seven subattributes and is weighted at w = 0.193. This specific contribution model demonstrates a 3-level hierarchical structure, as shown in Fig. 2 . The scores for each criterion could indicate each attribute’s importance and explain the priority order of the groups. Briefly, the critical sequence of each measure in the model at Level 2 is as follows: economic perspective > environmental perspective > leisure and educational perspective > sociocultural perspective. Since scoring and ranking were provided by 18 experts from three different backgrounds and calculated using fuzzy AHP, our rural tourism contribution model is established. It can provide policy-makers with information on the long-term benefits and advantages following the completion of excellent community development in rural areas.

The priority index of each attribute and sub-attribute.

Discussion/Implications

In the era of sustainable rural development, it is vital to consider the role of rural tourism and how research in this area shapes access to knowledge on rural community development. This study provides four findings based on the increasing tendency of policy-makers to use such information to shape their policy-making priorities. It first shows that the demand for rural tourism has soared, particularly during COVID-19. Second, it lists four significant perspectives regarding the specific contributions of rural tourism to rural community development and delineates how these four perspectives affect rural tourism development. Our findings are consistent with those of prior studies. For example, geography has been particularly important in the rural or peripheral tourism literature (Carson, 2018 ). In terms of the local geographical context, two contributions could be made by rural tourism. The first stems from the environmental perspective. When a rural community develops rural tourism, environmental protection awareness is increased, and the responsible utilization of natural resources is promoted. This finding aligns with Lee and Jan ( 2019 ). The second stems from the leisure and educational perspective. The geographical context of a rural community, which provides tourists with geographical uniqueness, advances naturally calming, sensory-rich, and emotion-generating experiences for tourists. These results suggest that rural tourism will likely positively impact tourists’ experience. This finding is consistent with Kastenhoz et al. ( 2020 ). Third, although expert-based approaches have considerable benefits in developing and testing underlying phenomena, evidence derived from interexpert consensus, intergroup consistency, and interexpert reliability has been sparse. This study provides such evidence. Fourth, this research shows that rural tourism makes four main contributions, economic, sociocultural, environmental, leisure, and educational, to rural community development. Our results show four key indicators at Level 2. The economic perspective is strongly regarded as the most important indicator, followed by the environmental perspective, leisure and educational perspective, and sociocultural perspective, which is weighted as the least important. The secondary determinants of contributions have 32 subindicators at Level 3: each was identified and assigned a different weight. These results imply that the attributes or subattributes with high weights have more essential roles in understanding the contributions of rural tourism to rural community development. Policy-makers can use these 32 subindicators to formulate rural tourism development policies or strategies.

This study offers the following five practical implications for policymakers and rural communities:

First, we argue that developing rural tourism within a rural community is an excellent strategy for revitalization and countering the effects of urbanization, depopulation, deforestation, and unemployment.

Second, our analytical results indicate that rural tourism’s postdevelopment contribution is significant from the economic, sociocultural, environmental, leisure, and educational perspectives, which is consistent with Lee and Jan ( 2019 ).

Third, there is an excellent opportunity to build or invest more in rural tourism during COVID-19, not only because of the functions of rural tourism but also because of its timing. Many prior studies have echoed this recommendation. For example, Yang et al. ( 2021 ) defined rural tourism as the leading industry in rural areas, offering an output value ten times higher than that of agriculture in China. In addition, rural tourism has become more attractive to urban tourists amid COVID-19. Vaishar and Šťastná ( 2022 ) suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic created a strong demand for rural tourism, which can mitigate threats to public mental health, such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, isolation, and insomnia. Marques et al. ( 2022 ) showed that tourists’ preference for tourism in rural areas increased substantially during COVID-19.

Fourth, the contributions of this study to policy development are substantial. The more focused rural tourism in rural areas is, the more effective revitalization becomes. This finding highlights the importance of such features in developing rural tourism to enhance rural community development from multiple perspectives. This finding echoes Zawadka et al. ( 2022 ); i.e., policy-makers should develop rural tourism to provide tourists with a safe and relaxed environment and should not ignore the value of this model for rural tourism.

Fifth, our developed model could drive emerging policy issues from a supporting perspective and provide policy-makers with a more comprehensive overview of the development of the rural tourism sector, thus enabling them to create better policies and programs as needed. For example, amid COVID-19, rural tourism created a safe environment for tourists, mainly by reducing their fears of contamination (Dennis et al., 2021 ). This novel contribution that rural tourism destinations can provide to residents and visitors from other places should be considered and built into any rural community development policy.

This study also has the following four methodological implications for researchers:

First, it addresses methodological limitations that still impede tourism sustainability model development. Specifically, we suggest a six-stage procedure as the guideline; it is imperative that rural tourism researchers or model developers follow this procedure. If they do not, their findings tend to be flawed.

Second, to ensure that collected data are without extraneous interference or differences via subgroups of experts, the assessment of intergroup consistency with the K–W test instead of one-way ANOVA is proposed, especially in small samples and distribution-free studies.

Third, providing interexpert reliability evidence within expert-based research is critical; we used Kendall’s W to assess the reliability among experts for each sample group because it applies to any sample size and ordinal number.

Finally, we recommend using fuzzy AHP to establish a model with appropriate indicators for decision-making or selection. This study offers novel methodological insights by estimating a theoretically grounded and empirically validated rural tourism contribution model.

There are two limitations to this study. First, we examine all subattributes by interexpert consensus to delete construct-irrelevant variances that might receive criticism for their lack of statistical rigor. Future studies can use other rigorous methods, such as AD M( j ) or rWG ( j ) , interexpert agreement indices to assess and eliminate construct-irrelevant variances. Second, we recommend maximizing rural tourism contributions to rural community development by using the general population as a sample to identify any differences. More specifically, we recommend using Cronbach’s alpha, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the overall reliability and validity of the data and results. It is also necessary to provide results for goodness-of-fit measures—e.g., the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), or root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Numerous empirical studies have illustrated how rural tourism can positively and negatively affect the contexts in rural areas where it is present. This study reveals the positive contributions of rural tourism to rural community development. The findings show that using rural tourism as a revitalization strategy is beneficial to nonurban communities in terms of their economic, sociocultural, environmental, and leisure and educational development. The contribution from the economic perspective is particularly important. These findings suggest that national, regional, and local governments or community developers should make tourism a strategic pillar in their policies for rural development and implement tourism-related development projects to gain 32 benefits, as indicated in Fig. 2 . More importantly, rural tourism was advocated and proved effective for tourists and residents to reduce anxiety, depression, or insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic. With this emerging contribution, rural tourism is becoming more critical to tourists from urban areas and residents involved in rural community development. With this model, policy-makers should not hesitate to develop or invest more in rural communities to create additional tourism-based activities and facilities. As they could simultaneously advance rural community development and public mental health, policy-makers should include these activities among their regional resilience considerations and treat them as enablers of sustainable rural development. We conclude that amid COVID-19, developing rural tourism is an excellent strategy for promoting rural community development and an excellent alternative that could counteract the negative impacts of urbanization and provide stakeholders with more positive interests. The proposed rural tourism contribution model also suggests an unfolding research plan.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Alford P, Jones R (2020) The lone digital tourism entrepreneur: Knowledge acquisition and collaborative transfer. Tour Manag 81:104–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104139

Article Google Scholar

Altieri MA, Farrell JG, Hecht SB, Liebman M, Magdoff F et al (2018) The agroecosystem: determinants, resources, processes, and sustainability. Agroecology 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429495465-3

Ambelu G, Lovelock B, Tucker H (2018) Empty bowls: conceptualising the role of tourism in contributing to sustainable rural food security. J Sustain Tour 26(10):1749–1765. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1511719

An W, Alarcon S (2020) How can rural tourism be sustainable? A systematic review. Sustainability 12(18):7758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187758

Arroyo C, Barbieri C, Rich SR (2013) Defining agritourism: a comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour Manag 37:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.007

Asmelash AG, Kumar S (2019) Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour Manag 71:67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.020

Atun RA, Nafa H, Türker ÖO (2019) Envisaging sustainable rural development through ‘context-dependent tourism’: case of Northern Cyprus. Environ Dev Sustain 21:1715–1744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0100-8

Belur J, Tompson L, Thornton A, Simon M (2021) Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociol Methods Res 50(2):837–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799372

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Carson DA (2018) Challenges and opportunities for rural tourism geographies: a view from the ‘boring’ peripheries. Tour Geogr 20(4):737–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/4616688.2018.1477173

Cheng L, Zhang J (2020) Is tourism development a catalyst of economic recovery following natural disaster? An analysis of economic resilience and spatial variability. Curr Issues Tour 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1711029

Choi H-SC, Sirakaya E (2006) Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour Manag 27(6):1274–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.05.018

Chong KY, Balasingam AS (2019) Tourism sustainability: economic benefits and strategies for preservation and conservation of heritage sites in Southeast Asia. Tour Rev 74(2):268–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-11-2017-0182

Christou PA (2020) Tourism experiences as the remedy to nostalgia: conceptualizing the nostalgia and tourism nexus. Curr Issues Tour 23(5):612–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1548582

Coria J, Calfucura E (2012) Ecotourism and the development of indigenous communities: the good, the bad and the ugly. Ecol Econ 73(15):47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.10.024

Cunha C, Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ (2020) Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? J Hosp Tour Manag 44:215–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.06.007

Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK (1979) Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change 13(1):83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-1625(79)90007-6

Dempsey PA, Dempsey AD (1992) Nursing research with basic statistical applications, 3rd edn. Jones and Bartlett, Boston

Google Scholar

Dennis D, Radnitz C, Wheaton MG (2021) A perfect storm? Health anxiety, contamination fears, and COVID-19: lessons learned from past pandemics and current challenges. Int J Cogn Ther 14:497–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-021-00109-7

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Di TF, Laura M (2021) How green possibilities can help in a future sustainable conservation of cultural heritage in Europe. Sustainability 13(7):3609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073609

Erensal YC, ncan TÖ, Demircan ML (2006) Determining key capabilities in technology management using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process: a case study of Turkey. Inf Sci 176(18):2755–2770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2005.11.004

Everett S, Slocum SL (2013) Food and tourism: an effective partnership? A UK-based review. J Sustain Tour 21(6):789–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.741601

Förster B, von der Gracht H (2014) Assessing Delphi panel composition for strategic foresight—a comparison of panels based on company-Internal and external participants. Technol Forecast Soc Change 84:215–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/.techfore.2013.07.012

Getz D (2008) Event tourism: definition, evolution and research. Tour Manag 29(3):403–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.07.017

Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Shale HM, Lang AE, Chernik DA, Chmura TA, Ahlskog JE, Dorflinger EE (1994) Utility of an objective dyskinesia rating scale for Parkinson’s disease: inter- and intrarater reliability assessment. Mov Disord 9(4):390–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.870090403

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hegarty C, Przezborska L (2005) Rural and agri-tourism as a tool for reorganizing rural areas in old and new member states—a comparison study of Ireland and Poland. Int J Tour Res 7(2):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.513

Henning JIF, Jordaan H (2016) Determinants of financial sustainability for farm credit applications—a Delphi study. Sustainability 8(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010077

Higham JES, Ritchie B (2001) The evolution of festivals and other events in rural Southern New Zealand. Event Manag 7(1):39–49. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599501108751461

Huck SW (2004) Reading statistics and research, 4th edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Islam MS, Lovelock B, Coetzee WJL (2021) Liberating sustainability indicators: developing and implementing a community-operated tourism sustainability indicator system in Boga Lake, Bangladesh. J Sustain Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1928147

James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G (1984) Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J Appl Psychol 69(1):322–327. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85

Juschten M, Hössinger R (2020) Out of the city - But how and where? A mode-destination choice model for urban–rural tourism trips in Austria. Curr Issues Tour 24(10):1465–1481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1783645

Kabadayi S, O’Connor G, Tuzovic S (2020) Viewpoint: the impact of coronavirus on service ecosystems as service mega-disruptions. J Serv Mark 34(6):809–817. reurl.cc/oen0lM

Kaptan AÇ, Cengı̇z TT, Özkök F, Tatlı H (2020) Land use suitability analysis of rural tourism activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tour Manag 76:103949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.07.003

Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ, Marques CP, Lima J (2012) Understanding and managing the rural tourism experience—the case of a historical village in Portugal. Tour Manag Perspect 4:207–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.08.009

Kastenholz E, Carneiro M, Marques CP, Loureiro SMC (2018) The dimensions of rural tourism experience: impacts on arousal, memory and satisfaction. J Travel Tour Mark 35(2):189–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1350617

Kastenhoz E, Marques CP, Carneiro MJ (2020) Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. J Destin Mark Manage 17:100455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100455

Kelliher F, Rein L, Johnson TG, Joppe M (2018) The role of trust in building rural tourism micro firm network engagement: a multi-case study. Tour Manag 68:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.014

Kozlowski SW, Hattrup K (1992) A disagreement about within-group agreement: disentangling issues of consistency versus consensus. J Appl Psychol 77(2):161–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.2.161

Landeta J (2006) Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol Forecast Soc Change 73(5):467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002

Lankford SV (1994) Attitudes and perceptions toward tourism and rural regional development. J Travel Res 32(3):35–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759403200306

Lane B (1994) What is rural tourism? J Sustain Tour 2(1&2):7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510680

Lee TH, Jan FH (2019) Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents perceptions of the sustainability. Tour Manag 70:368–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.09.003

Lee J, Árnason A, Nightingale A, Shucksmith M (2006) Networking: Social capital and identities in European rural development. Sociol Rural 45(4):269–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2005.00305.x

Lewis JB, Delisle L (2004) Tourism as economic self-development in rural Nebraska: a case study. Tour Anal 9(3):153–166. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354204278122

Li Y, Westlund H, Liu Y (2019) Why some rural areas decline while some others not: an overview of rural evolution in the world. J Rural Stud 68:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.003

Li Z, Zhang X, Yang K, Singer R, Cui R (2021) Urban and rural tourism under COVID-19 in China: research on the recovery measures and tourism development. Tour Rev 76(4):718–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2020-0357

Lin CL (2022) Evaluating the urban sustainable development strategies and common suited paths considering various stakeholders. Environ Dev Sustain 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-02021-8

Liu CY, Doub XT, Lia JF, Caib LA (2020) Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: an empirical investigation from China. J Rural Stud 79:177–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.046

Loftus IM, Naylor AR, Goodall SM, Crowther LJ, Bell PRF, Thompson MM (2000) Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in unstable carotid plaques: a potential role in acute plaque disruption. Stroke 31(1):40–47. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.31.1.40

López-Sanz JM, Penelas-Leguía A, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez P, Cuesta-Valiño P (2021) Sustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land 10(9):985. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090985

Love PED, Irani Z (2004) An exploratory study of information technology evaluation and benefits management practices of SMEs in the construction industry. Inf Manag 42(1):227–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.12.011

Ma X, Wang R, Dai M, Ou Y (2021) The influence of culture on the sustainable livelihoods of households in rural tourism destinations. J Sustain Tour 29:1235–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1826497

Markey S, Halseth G, Manson D (2008) Challenging the inevitability of rural decline: advancing the policy of place in northern British Columbia. J Rural Stud 24:409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.03.012

Marques H (2006) Searching for complementarities between agriculture and tourism—the demarcated wine-producing regions of Northern Portugal. Tour Econ 12(1):147–155. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000006776387141

Marques CP, Guedes A, Bento R (2022) Rural tourism recovery between two COVID-19 waves: the case of Portugal. Curr Issues Tour 25(6):857–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1910216

Marzo-Navar M, Pedraja-Iglesia M, Vinzon L (2015) Sustainability indicators of rural tourism from the perspective of the residents. Tour Geogr 17(4):586–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2015.1062909

Messick S (1995) Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol 50(9):741–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.9.741

Mikhailov L, Tsvetinov P (2004) Evaluation of services using a fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Appl Soft Comput 5(1):23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2004.04.001

Mukherjee N, Huge J, Sutherland WJ, McNeill J, Van Opstal M, Dahdouh-Guebas F, Koedam N (2015) The Delphi technique in ecology and biological conservation: applications and guidelines. Methods. Ecol Evol 6(9):1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12387

Murphy-Black T, Lamping D, McKee M, Sanderson C, Askham J, Marteau T (1998) CEM and their use in clinical guideline development—factors which influence the process and outcome of CDMs. Health Technol Assess 2(3):1–88

Nicholson RE, Pearce DG (2001) Why do people attend events: a comparative analysis of visitor motivations at four south island events. J Travel Res 39:449–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750103900412

Northcote J, Lee D, Chok S, Wegner A (2008) An email-based Delphi approach to tourism program evaluation: involving stakeholders in research design. Curr Issues Tour 11(3):269–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802140315

Oh CO (2005) The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tour Manag 26(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.014

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD (2004) The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag 42(1):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

Otto JE, Ritchie JRB (1996) The service experience in tourism. Tour Manag 17(3):165–174

Paraskevas A, Saunders MNK (2012) Beyond consensus: an alternative use of Delphi enquiry in hospitality research. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 24(6):907–924. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211247236

Park DB, Yoon YS (2011) Developing sustainable rural tourism evaluation indicators. Int J Tour Res 13(5):401–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.804

Petrovi´c MD, Vujko A, Gaji´c T, Vukovi´c DB, Radovanovi´c M, Jovanovi´c JM, Vukovi´c N (2018) Tourism as an approach to sustainable rural development in post-socialist countries: a comparative study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 10(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010054

Phillip S, Hunter C, Blackstock K (2010) A typology for defining agritourism. Tour Manag 31(6):754–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.08.001

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY et al. (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Polukhina A, Sheresheva M, Efremova M, Suranova O, Agalakova O, Antonov-Ovseenko A (2021) The concept of sustainable rural tourism development in the face of COVID-19 crisis: evidence from Russia. J Risk Financ Manag 14:38. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14010038

Potvin C, Roff DA (1993) Distribution-free and robust statistical methods: viable alternatives to parametric statistics. Ecology 74(6):1617–1628. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939920

Quadri-Felitti DL, Fiore AM (2013) Destination loyalty: effects of wine tourists’ experiences, memories, and satisfaction on intentions. Tour Hosp Res 13(1):47–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358413510017

Ram Y, Collins-Kreiner N, Gozansky E, Moscona G, Okon-Singer H (2022) Is there a COVID-19 vaccination effect? A three-wave cross-sectional study. Curr Issues Tour 25(3):379–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1960285

Rice K (2009) Priorities in K-12 distance education: a Delphi study examining multiple perspectives on policy, practice, and research. Educ Technol Soc 12(3):163–177

Roberson QM, Sturman MC, Simons TL (2007) Does the measure of dispersion matter in multilevel research? Organ Res Methods 10(4):564–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106294746

Ryu K, Roy PA, Kim H, Ryu H (2020) The resident participation in endogenous rural tourism projects: a case study of Kumbalangi in Kerala, India. J Travel Tour Mark 37(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1687389

Schilling MA (2002) Technology success and failure in winner-take-all markets: the impact of learning orientation, timing, and network externalities. Acad Manag J 45(2):387–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069353

Schmidt R, Lyytinen K, Keil M, Cule P (2001) Identifying software project risks: an international Delphi study. J Manag Inf Syst 17(4):5–36. https://reurl.cc/RrE1qG

Silva L, Leal J (2015) Rural tourism and national identity building in contemporary Europe: evidence from Portugal. J Rural Stud 38:109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.02.005

Singletary M (1994) Mass communication research: contemporary methods and applications. Longman, New York

Slater SJ (2020) Recommendations for keeping parks and green space accessible for mental and physical health during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Prev Chronic Dis https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200204

Spector PE, Cooper CL, Sanchez JI, O’Driscoll M, Sparks K, Bernin P et al. (2002) Locus of control and well-being at work: How generalizable are western findings? Acad Manag J 45(2):453–470. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069359

Stewart BT, Gyedu A, Quansah R, Addo WL, Afoko A, Agbenorku P et al. (2016) District-level hospital trauma care audit filters: Delphi technique for defining context-appropriate indicators for quality improvement initiative evaluation in developing countries. Injury 47(1):211–219. https://reurl.cc/WrMLOk

Su MM, Dong Y, Geoffrey W, Sun Y (2020) A value-based analysis of the tourism use of agricultural heritage systems: Duotian Agrosystem, Jiangsu Province, China. J Sustain Tour 28(12):2136–2155. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1795184

Taylor-Powell E (2002) Quick tips collecting group data: Delphi technique. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Tew C, Barbieri C (2012) The perceived benefits of agritourism: the provider’s perspective. Tour Manag 33(1):215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.005

Theodori GL (2001) Examining the effects of community satisfaction and attachment on individual well-being. Rural Sociol 66(4):618–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2001.tb00087.x

Tinsley HEA, Weiss DJ (1975) Interrater reliability and agreement of subjective judgments. J Couns Psychol 22(4):358–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076640

UNWTO (2021) Rural tourism. https://www.unwto.org/rural-tourism . Accessed 3 Nov 2021

Uysal M, Sirgy MJ, Woo E, Kim H (2016) Quality of Life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour Manag 53:244–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Vail D, Hultkrantz L (2000) Property rights and sustainable nature tourism: adaptation and mal-adaptation in Dalarna (Sweden) and Maine (USA). Ecol Econ 35(2):223–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00190-7

Vaishar A, Šťastná M (2022) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural tourism in Czechia preliminary considerations. Curr Issues Tour 25(2):187–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1839027

Vergani L, Cuniberti M, Zanovello M et al. (2022) Return to play in long-standing adductor-related groin pain: a Delphi study among experts. Sports Med—Open 8:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00400-z

World Tourism Organization (2020) UNWTO recommendations on tourism and rural development—a guide to making tourism an effective tool for rural development. UNWTO, Madrid

Book Google Scholar

Yang Z, Cai J, Sliuzas R (2010) Agro-tourism enterprises as a form of multi-functional urban agriculture for peri-urban development in China. Habitat Int 34(4):374–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.002

Yang J, Yang RX, Chen MH, Su CH, Zhi Y, Xi JC (2021) Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J Hosp Tour Manag 47:35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.02.008

Zawadka J, Jęczmyk A, Wojcieszak-Zbierska MM, Niedbała G, Uglis J, Pietrzak-Zawadka J (2022) Socio-economic factors influencing agritourism farm stays and their safety during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Poland. Sustainability 14:3526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063526

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zhao W, Brent Ritchie JR (2007) Tourism and poverty alleviation: an integrative research framework. Curr Issues Tour 10(2&3):119–143. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit296.0

Zinn J, Zalokowski A, Hunter L (2001) Identifying indicators of laboratory management performance: a multiple constituency approach. Health Care Manag Rev 26(1):40–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44951308

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chienkuo Technology University, Changhua, Taiwan

Yung-Lun Liu

Dayeh University, Changhua, Taiwan

Jui-Te Chiang & Pen-Fa Ko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

We declare all authors involved in the work. The division of labor is stated as follows; Conceptualization: J-TC; Supervision: J-TC; Methodology: Y-LL; Investigation: Y-LL; Data collection, analysis, and curation: J-TC, Y-LL, P-FK; Original draft preparation: J-TC, Y-LL; Review: P-FK; Interpretation and editing: P-FK; Validation: J-TC, Y-LL, P-FK.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jui-Te Chiang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Obtaining ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the authors’ institution for such tourism management in Taiwan is unnecessary. This study was granted an exemption from requiring ethical approval.

Informed consent

To obtain the necessary permissions, prior to the questionnaire survey, we contacted all 18 content experts by telephone and explained the purpose of this study. This research was limited to an anonymous survey with no additional personal information recorded or analyzed beyond that shown to the survey experts. Subsequently, we sent the questionnaire with detailed information to those who confirmed that they wanted to cooperate. We have included all three authors’ contact information and the letter of withdrawal of cooperation for all eighteen experts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Liu, YL., Chiang, JT. & Ko, PF. The benefits of tourism for rural community development. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01610-4

Download citation

Received : 03 July 2022

Accepted : 06 March 2023

Published : 31 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01610-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

Impacts of Tourism Development on Residents’ Quality of Life: Efficacy of Community Capitals in Gateway Communities, Northern Tanzania

- Published: 20 June 2023

- Volume 18 , pages 2511–2539, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Alpha J. Mwongoso ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3508-3742 1 ,

- Agnes Sirima ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0810-6785 2 &

- John T. Mgonja ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8226-9462 2

343 Accesses

Explore all metrics

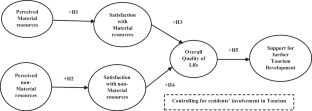

This study examined the structural relationship involving residents’ perception of tourism impacts embedded on material and non-material community capitals, satisfaction, quality of life and whether residents support for further tourism development. Multi method approach was employed to collect data. Focus group discussion with key informants coupled with trend data on wealth, tourism receipts and expenditure complemented the household survey. The hypothesized structural model was empirically tested, involving a randomly selected sample of 408 agro-pastoral residents from three gateway communities; Loliondo, lake Natron and Burrunge in northern Tanzania. It was found that residents support for further tourism development is a function of favourable perceived quality of life, influenced by residents’ satisfaction with both material impacts (i.e. increase in physical and financial capital) and non-material impacts (e.g. devolution of power to community and social-cultural cohesion). However, despite positive tourism impacts observed, residents endure costs in land-use in terms of restricted grazing and cultivation in order to sustain tourism. The study drew conclusion that c ommunity capital framework extends the traditional tripartite tourism impacts (i.e. economic, social and environment) to other aspects such as: political, cultural, human and built-capital, thus, provide a thorough understanding about tourism impacts in predicting residents’ quality of life. Future studies should emphasize on the efficacy of community capitals in the context of tourism development and its impacts on resident’s quality of life.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: a suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism

Being Well Together: Individual Subjective and Community Wellbeing

Reconnecting with nature for sustainability, data availability.

The datasets used for analysis in this study are available from the corresponding author upon special request.

Afenyo, E. A., & Amuquandoh, F. E. (2014). Who benefits from community-based ecotourism development? Insights from Tafi Atome Ghana. Tourism Planning and Development, 11 (2), 179–190

Article Google Scholar

Andereck, K. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2011). Exploring the Nature of Tourism and Quality of Life Perceptions among Residents. Journal of Travel Research, 50 (3), 248–260

Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ Perceptions on Tourism Impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19 (4), 665–690

Arroyo, C. G., Knollenberg, W., & Barbieri, C. (2021). Inputs and outputs of craft beverage tourism: The Destination Resources Acceleration Framework. Annals of Tourism Research, 86 , 10–31

Google Scholar

Ashley, C. (2000). The impacts of tourism on rural livelihoods: Namibia’s experience (p. 31). Overseas Development Institute

Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37 (2), 157–167

Bennett, N., Lemelin, R. H., Koster, R., & Budke, I. (2012). A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tourism Management, 33 (4), 752–766

Bluwstein, J., Homewood, K., Lund, J. F., Nielsen, M. R., Burgess, N., Msuha, M., & Keane, A. (2018). A quasi-experimental study of impacts of Tanzania’s wildlife management areas on rural livelihoods and wealth. Scientific Data, 5 (1), 1–13

Briggs, Xds. (2004). Social capital: Easy beauty or meaningful resource? Journal of the American Planning Association, 70 , 151–158

Brown, T. A. (2015). Methodology in the Social Sciences. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. 220pp

Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area life cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer, 24 (1), 5–12

Butler, R.W. (Ed.). (2006). The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Vol. 2. Conceptual and Theoretical Issues. Channel View Publications

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (3rd ed., pp. 541–554). Routledge

Book Google Scholar

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group

Campón-Cerro, A. M., Folgado-Fernández, J. A., & Hernández-Mogollón, J. M. (2017). Rural destination development based on olive oil tourism: The impact of residents’ community attachment and quality of life on their support for tourism development. Sustainability, 9 (9), 1–24

Daniel, W. W. & Cross, C. L. (2013). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences (10 th eds.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc, Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 53: 1–25

De Boer, D., & Van Dijk, M. P. (2016). Can Sustainable Tourism Achieve Conservation and Local Economic Development? The Experience with Nine Business-Community Wildlife-Tourism Agreements in Northern Tanzania. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure, 5 (4), 1–19