Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space

After working for five months to re-establish communication with the farthest-flung human-made object in existence, NASA announced this week that the Voyager 1 probe had finally phoned home.

For the engineers and scientists who work on NASA’s longest-operating mission in space, it was a moment of joy and intense relief.

“That Saturday morning, we all came in, we’re sitting around boxes of doughnuts and waiting for the data to come back from Voyager,” said Linda Spilker, the project scientist for the Voyager 1 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We knew exactly what time it was going to happen, and it got really quiet and everybody just sat there and they’re looking at the screen.”

When at long last the spacecraft returned the agency’s call, Spilker said the room erupted in celebration.

“There were cheers, people raising their hands,” she said. “And a sense of relief, too — that OK, after all this hard work and going from barely being able to have a signal coming from Voyager to being in communication again, that was a tremendous relief and a great feeling.”

The problem with Voyager 1 was first detected in November . At the time, NASA said it was still in contact with the spacecraft and could see that it was receiving signals from Earth. But what was being relayed back to mission controllers — including science data and information about the health of the probe and its various systems — was garbled and unreadable.

That kicked off a monthslong push to identify what had gone wrong and try to save the Voyager 1 mission.

Spilker said she and her colleagues stayed hopeful and optimistic, but the team faced enormous challenges. For one, engineers were trying to troubleshoot a spacecraft traveling in interstellar space , more than 15 billion miles away — the ultimate long-distance call.

“With Voyager 1, it takes 22 1/2 hours to get the signal up and 22 1/2 hours to get the signal back, so we’d get the commands ready, send them up, and then like two days later, you’d get the answer if it had worked or not,” Spilker said.

The team eventually determined that the issue stemmed from one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers. Spilker said a hardware failure, perhaps as a result of age or because it was hit by radiation, likely messed up a small section of code in the memory of the computer. The glitch meant Voyager 1 was unable to send coherent updates about its health and science observations.

NASA engineers determined that they would not be able to repair the chip where the mangled software is stored. And the bad code was also too large for Voyager 1's computer to store both it and any newly uploaded instructions. Because the technology aboard Voyager 1 dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, the computer’s memory pales in comparison to any modern smartphone. Spilker said it’s roughly equivalent to the amount of memory in an electronic car key.

The team found a workaround, however: They could divide up the code into smaller parts and store them in different areas of the computer’s memory. Then, they could reprogram the section that needed fixing while ensuring that the entire system still worked cohesively.

That was a feat, because the longevity of the Voyager mission means there are no working test beds or simulators here on Earth to test the new bits of code before they are sent to the spacecraft.

“There were three different people looking through line by line of the patch of the code we were going to send up, looking for anything that they had missed,” Spilker said. “And so it was sort of an eyes-only check of the software that we sent up.”

The hard work paid off.

NASA reported the happy development Monday, writing in a post on X : “Sounding a little more like yourself, #Voyager1.” The spacecraft’s own social media account responded , saying, “Hi, it’s me.”

So far, the team has determined that Voyager 1 is healthy and operating normally. Spilker said the probe’s scientific instruments are on and appear to be working, but it will take some time for Voyager 1 to resume sending back science data.

Voyager 1 and its twin, the Voyager 2 probe, each launched in 1977 on missions to study the outer solar system. As it sped through the cosmos, Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, studying the planets’ moons up close and snapping images along the way.

Voyager 2, which is 12.6 billion miles away, had close encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and continues to operate as normal.

In 2012, Voyager 1 ventured beyond the solar system , becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, or the space between stars. Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Spilker, who first began working on the Voyager missions when she graduated college in 1977, said the missions could last into the 2030s. Eventually, though, the probes will run out of power or their components will simply be too old to continue operating.

Spilker said it will be tough to finally close out the missions someday, but Voyager 1 and 2 will live on as “our silent ambassadors.”

Both probes carry time capsules with them — messages on gold-plated copper disks that are collectively known as The Golden Record . The disks contain images and sounds that represent life on Earth and humanity’s culture, including snippets of music, animal sounds, laughter and recorded greetings in different languages. The idea is for the probes to carry the messages until they are possibly found by spacefarers in the distant future.

“Maybe in 40,000 years or so, they will be getting relatively close to another star,” Spilker said, “and they could be found at that point.”

Denise Chow is a reporter for NBC News Science focused on general science and climate change.

Voyager, NASA’s Longest-Lived Mission, Logs 45 Years in Space

This archival image taken at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory on March 23, 1977, shows engineers preparing the Voyager 2 spacecraft ahead of its launch later that year.

Launched in 1977, the twin Voyager probes are NASA’s longest-operating mission and the only spacecraft ever to explore interstellar space.

NASA’s twin Voyager probes have become, in some ways, time capsules of their era: They each carry an eight-track tape player for recording data, they have about 3 million times less memory than modern cellphones, and they transmit data about 38,000 times slower than a 5G internet connection.

Yet the Voyagers remain on the cutting edge of space exploration. Managed and operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, they are the only probes to ever explore interstellar space – the galactic ocean that our Sun and its planets travel through.

The Sun and the planets reside in the heliosphere, a protective bubble created by the Sun’s magnetic field and the outward flow of solar wind (charged particles from the Sun). Researchers – some of them younger than the two distant spacecraft – are combining Voyager’s observations with data from newer missions to get a more complete picture of our Sun and how the heliosphere interacts with interstellar space.

NASA’s Solar System Interactive lets users see where the Voyagers are right now relative to the planets, the Sun, and other spacecraft. View it yourself here . Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“The heliophysics mission fleet provides invaluable insights into our Sun, from understanding the corona or the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere, to examining the Sun’s impacts throughout the solar system, including here on Earth, in our atmosphere, and on into interstellar space,” said Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Over the last 45 years, the Voyager missions have been integral in providing this knowledge and have helped change our understanding of the Sun and its influence in ways no other spacecraft can.”

The Voyagers are also ambassadors, each carrying a golden record containing images of life on Earth, diagrams of basic scientific principles, and audio that includes sounds from nature, greetings in multiple languages, and music. The gold-coated records serve as a cosmic “message in a bottle” for anyone who might encounter the space probes. At the rate gold decays in space and is eroded by cosmic radiation, the records will last more than a billion years.

45 Years of Voyager I and II

Launched in 1977, NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft inspired the world with pioneering visits to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Their journey continues 45 years later as both probes explore interstellar space, the region outside the protective heliosphere created by our Sun. Researchers – some younger than the spacecraft – are now using Voyager data to solve mysteries of our solar system and beyond.

This archival photo shows engineers working on vibration acoustics and pyro shock testing of NASA’s Voyager on Nov. 18, 1976. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Voyager 1 acquired this image of a volcanic explosion on Io on March 4, 1979, about 11 hours before the spacecraft’s closest approach to the moon of Jupiter.

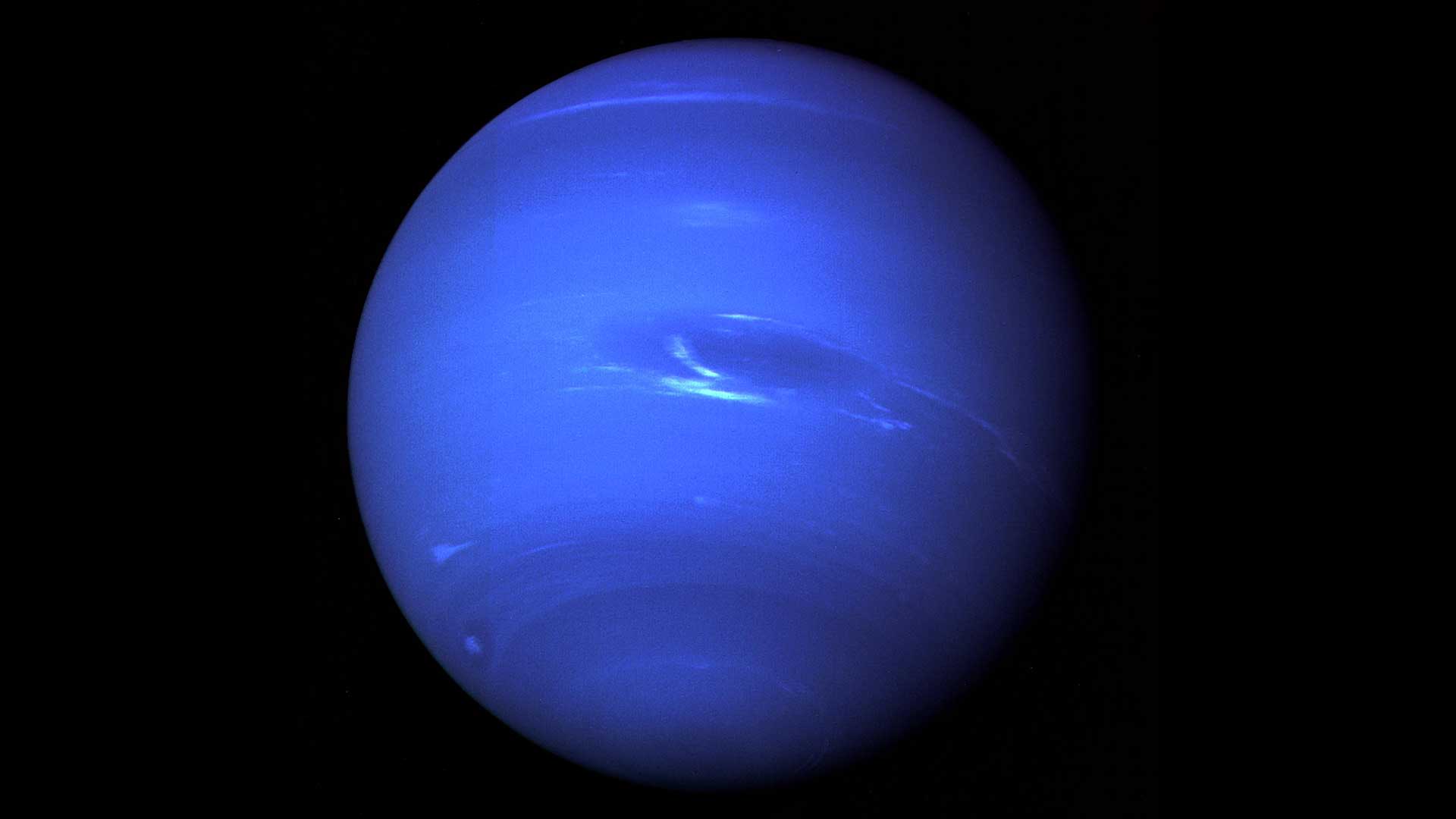

Neptune’s green-blue atmosphere was shown in greater detail than ever before in this image from NASA’s Voyager 2 as the spacecraft rapidly approached its encounter with the giant planet in August 1989.

This updated version of the iconic "Pale Blue Dot" image taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft uses modern image-processing software and techniques to revisit the well-known Voyager view while attempting to respect the original data and intent of those who planned the images.

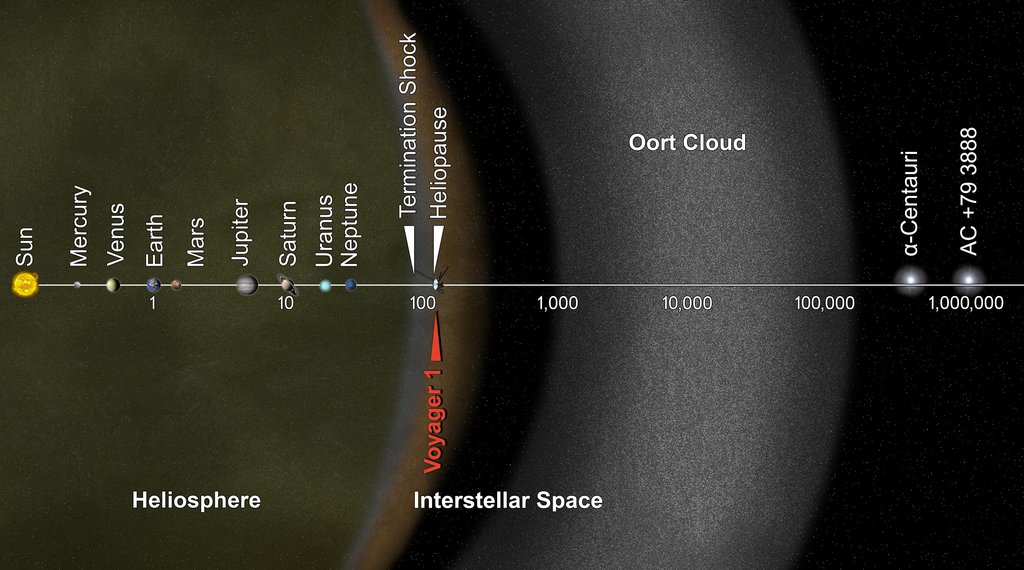

This illustrated graphic was made to mark Voyager 1’s entry into interstellar space in 2012. It puts solar system distances in perspective, with the scale bar in astronomical units and each set distance beyond 1 AU (the average distance between the Sun and Earth) representing 10 times the previous distance.

This graphic highlights some of the Voyager mission’s key accomplishments. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech Full image details

This graphic provides some of the mission’s key statistics from 2018, when NASA’s Voyager 2 probe exited the heliosphere. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech Full image details

Beyond Expectations

Voyager 2 launched on Aug. 20, 1977, quickly followed by Voyager 1 on Sept. 5. Both probes traveled to Jupiter and Saturn, with Voyager 1 moving faster and reaching them first. Together, the probes unveiled much about the solar system’s two largest planets and their moons. Voyager 2 also became the first and only spacecraft to fly close to Uranus (in 1986) and Neptune (in 1989), offering humanity remarkable views of – and insights into – these distant worlds.

While Voyager 2 was conducting these flybys, Voyager 1 headed toward the boundary of the heliosphere. Upon exiting it in 2012 , Voyager 1 discovered that the heliosphere blocks 70% of cosmic rays, or energetic particles created by exploding stars. Voyager 2, after completing its planetary explorations, continued to the heliosphere boundary, exiting in 2018 . The twin spacecraft’s combined data from this region has challenged previous theories about the exact shape of the heliosphere.

Voyager 1 and 2 have accomplished a lot since they launched in 1977. This infographic highlights the mission’s major milestones, including visiting the four outer planets and exiting the heliosphere, or the protective bubble of magnetic fields and particles created by the Sun.

“Today, as both Voyagers explore interstellar space, they are providing humanity with observations of uncharted territory,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager’s deputy project scientist at JPL. “This is the first time we’ve been able to directly study how a star, our Sun, interacts with the particles and magnetic fields outside our heliosphere, helping scientists understand the local neighborhood between the stars, upending some of the theories about this region, and providing key information for future missions.”

The Long Journey

Over the years, the Voyager team has grown accustomed to surmounting challenges that come with operating such mature spacecraft, sometimes calling upon retired colleagues for their expertise or digging through documents written decades ago.

Each Voyager is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator containing plutonium, which gives off heat that is converted to electricity. As the plutonium decays, the heat output decreases and the Voyagers lose electricity. To compensate , the team turned off all nonessential systems and some once considered essential, including heaters that protect the still-operating instruments from the frigid temperatures of space. All five of the instruments that have had their heaters turned off since 2019 are still working, despite being well below the lowest temperatures they were ever tested at.

Get the Latest JPL News

Recently, Voyager 1 began experiencing an issue that caused status information about one of its onboard systems to become garbled. Despite this, the system and spacecraft otherwise continue to operate normally, suggesting the problem is with the production of the status data, not the system itself. The probe is still sending back science observations while the engineering team tries to fix the problem or find a way to work around it.

“The Voyagers have continued to make amazing discoveries, inspiring a new generation of scientists and engineers,” said Suzanne Dodd, project manager for Voyager at JPL. “We don’t know how long the mission will continue, but we can be sure that the spacecraft will provide even more scientific surprises as they travel farther away from the Earth.”

More About the Mission

A division of Caltech in Pasadena, JPL built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/voyager

News Media Contact

Calla Cofield

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

626-808-2469

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft finally phones home after 5 months of no contact

On Saturday, April 5, Voyager 1 finally "phoned home" and updated its NASA operating team about its health.

NASA's interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the Voyager 1 spacecraft still isn't sending valid science data back to Earth, it is now returning usable information about the health and operating status of its onboard engineering systems.

Thirty-five years after its launch in 1977, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system and enter interstellar space . It was followed out of our cosmic quarters by its space-faring sibling, Voyager 2 , six years later in 2018. Voyager 2, thankfully, is still operational and communicating well with Earth.

The two spacecraft remain the only human-made objects exploring space beyond the influence of the sun. However, on Nov. 14, 2023, after 11 years of exploring interstellar space and while sitting a staggering 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, Voyager 1's binary code — computer language composed of 0s and 1s that it uses to communicate with its flight team at NASA — stopped making sense.

Related: We finally know why NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft stopped communicating — scientists are working on a fix

In March, NASA's Voyager 1 operating team sent a digital "poke" to the spacecraft, prompting its flight data subsystem (FDS) to send a full memory readout back home.

This memory dump revealed to scientists and engineers that the "glitch" is the result of a corrupted code contained on a single chip representing around 3% of the FDS memory. The loss of this code rendered Voyager 1's science and engineering data unusable.

The NASA team can't physically repair or replace this chip, of course, but what they can do is remotely place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. Though no single section of the memory is large enough to hold this code entirely, the team can slice it into sections and store these chunks separately. To do this, they will also have to adjust the relevant storage sections to ensure the addition of this corrupted code won't cause those areas to stop operating individually, or working together as a whole. In addition to this, NASA staff will also have to ensure any references to the corrupted code's location are updated.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

— Voyager 2: An iconic spacecraft that's still exploring 45 years on

— NASA's interstellar Voyager probes get software updates beamed from 12 billion miles away

— NASA Voyager 2 spacecraft extends its interstellar science mission for 3 more years

On April 18, 2024, the team began sending the code to its new location in the FDS memory. This was a painstaking process, as a radio signal takes 22.5 hours to traverse the distance between Earth and Voyager 1, and it then takes another 22.5 hours to get a signal back from the craft.

By Saturday (April 20), however, the team confirmed their modification had worked. For the first time in five months, the scientists were able to communicate with Voyager 1 and check its health. Over the next few weeks, the team will work on adjusting the rest of the FDS software and aim to recover the regions of the system that are responsible for packaging and returning vital science data from beyond the limits of the solar system.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

SpaceX launches 20 Starlink satellites on 50th mission of the year (video)

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video)

Huge, solar flare-launching sunspot has rotated away from Earth. But will it return?

- Robb62 'V'ger must contact the creator. Reply

- Holy HannaH! Couldn't help but think that "repair" sounded extremely similar to the mechanics of DNA and the evolution of life. Reply

- Torbjorn Larsson *Applause* indeed, thanks to the Voyager teams for the hard work! Reply

- SpaceSpinner I notice that the article says that it has been in space for 35 years. Either I have gone back in time 10 years, or their AI is off by 10 years. V-*ger has been captured! Reply

Admin said: On Saturday, April 5, Voyager 1 finally "phoned home" and updated its NASA operating team about its health. The interstellar explorer is back in touch after five months of sending back nonsense data. NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft finally phones home after 5 months of no contact : Read more

evw said: I'm incredibly grateful for the persistence and dedication of the Voyagers' teams and for the amazing accomplishments that have kept these two spacecrafts operational so many years beyond their expected lifetimes. V-1 was launched when I was 25 years young; I was nearly delirious with joy. Exploring the physical universe captivated my attention while I was in elementary school and has kept me mesmerized since. I'm very emotional writing this note, thinking about what amounts to a miracle of technology and longevity in my eyes. BRAVO!!! THANK YOU EVERYONE PAST & PRESENT!!!

- EBairead I presume it's Fortran. Well done all. Reply

SpaceSpinner said: I notice that the article says that it has been in space for 35 years. Either I have gone back in time 10 years, or their AI is off by 10 years. V-*ger has been captured!

EBairead said: I presume it's Fortran. Well done all.

- View All 13 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 How do you forecast a solar storm? Space weather experts explain

- 3 Cosmic butterfly or interstellar burger? This planet-forming disk is the largest ever seen

- 4 To better predict volcanic eruptions, you have to dig deep — very deep

- 5 Where did Earth's water come from? This ancient asteroid family may help us find out

- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The eclipse issue.

Science and splendor under the shadow.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

The Voyager missions

Highlights Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched in 1977 and made a grand tour of the solar system's outer planets. They are the only functioning spacecraft in interstellar space, and they are still sending back measurements of the interstellar medium. Each spacecraft carries a copy of the golden record, a missive from Earth to any alien lifeforms that may find the probes in the future.

What are the Voyager missions?

The Voyager program consists of two spacecraft: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Voyager 2 was actually launched first, in August 1977, but Voyager 1 was sent on a faster trajectory when it launched about two weeks later. They are the only two functioning spacecraft currently in interstellar space, beyond the environment controlled by the sun.

Voyager 2’s path took it past Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1981, Uranus in 1985, and Neptune in 1989. It is the only spacecraft to have visited Uranus or Neptune, and has provided much of the information that we use to characterize them now.

Because of its higher speed and more direct trajectory, Voyager 1 overtook Voyager 2 just a few months after they launched. It visited Jupiter in 1979 and Saturn in 1980. It overtook Pioneer 10 — the only other spacecraft in interstellar space thus far — in 1998 and is now the most distant artificial object from Earth.

How the Voyagers work

The two spacecraft are identical, each with a radio dish 3.7 meters (12 feet) across to transmit data back to Earth and a set of 16 thrusters to control their orientations and point their dishes toward Earth. The thrusters run on hydrazine fuel, but the electronic components of each spacecraft are powered by thermoelectric generators that run on plutonium. Each carries 11 scientific instruments, about half of which were designed just for observing planets and have now been shut off. The instruments that are now off include several cameras and spectrometers to examine the planets, as well as two radio-based experiments. Voyager 2 now has five functioning instruments: a magnetometer, a spectrometer designed to investigate plasmas, an instrument to measure low-energy charged particles and one for cosmic rays, and one that measures plasma waves. Voyager 1 only has four of those, as its plasma spectrometer is broken.

Jupiter findings

Over the course of their grand tours of the solar system, the Voyagers took tens of thousands of images and measurements that significantly changed our understanding of the outer planets.

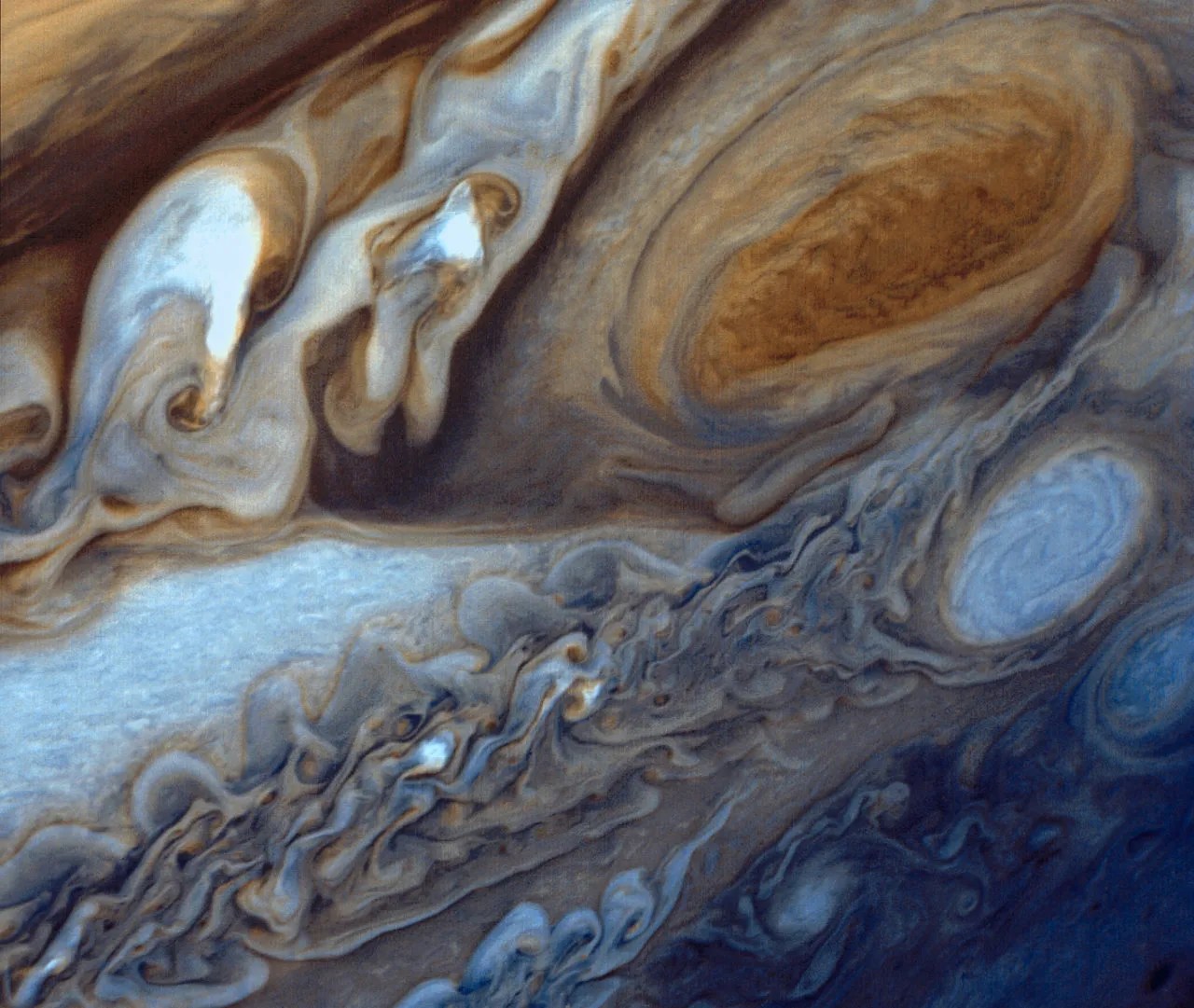

At Jupiter, they gave us our first detailed ideas of how the planet’s atmosphere moves and evolves, showing that the Great Red Spot was a counter-clockwise rotating storm that interacted with other, smaller storms. They were also the first missions to spot a faint, dusty ring around Jupiter. Finally, they observed some of Jupiter’s moons, discovering Io’s volcanism, finding the linear features on Europa that were among the first hints that it might have an ocean beneath its surface, and granting Ganymede the title of largest moon in the solar system, a superlative that was previously thought to belong to Saturn’s moon Titan.

Saturn findings

Next, each spacecraft flew past Saturn, where they measured the composition and structure of Saturn’s atmosphere , and Voyager 1 also peered into Titan’s thick haze. Its observations led to the idea that Titan might have liquid hydrocarbons on its surface, a hypothesis that has since been verified by other missions. When the two missions observed Saturn’s rings, they found the gaps and waves that are well-known today. Voyager 1 also spotted three previously-unknown moons orbiting Saturn: Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora.

Uranus and Neptune findings

After this, Voyager 1 headed out of the solar system, while Voyager 2 headed toward Uranus . There, it found 11 previously-unknown moons and two previously-unknown rings. Many of the phenomena it observed on Uranus remained unexplained, such as its unusual magnetic field and an unexpected lack of major temperature changes at different latitudes.

Voyager 2’s final stop, 12 years after it left Earth, was Neptune. When it arrived , it continued its streak of finding new moons with another haul of 6 small satellites, as well as finding rings around Neptune. As it did at Uranus, it observed the planet’s composition and magnetic field. It also found volcanic vents on Neptune’s huge moon Triton before it joined Voyager 1 on the way to interstellar space.

Interstellar space

Interstellar space begins at the heliopause, where the solar wind – a flow of charged particles released by the sun – is too weak to continue pushing against the interstellar medium, and the pressure from the two balances out. Voyager 1 officially entered interstellar space in August 2012, and Voyager 2 joined it in November 2018.

These exits were instrumental in enabling astronomers to determine where exactly the edge of interstellar space is, something that’s difficult to measure from within the solar system. They showed that interstellar space begins just over 18 billion kilometers (about 11 billion miles) from the sun. The spacecraft continue to send back data on the structure of the interstellar medium.

After its planetary encounters, Voyager 1 took the iconic “Pale Blue Dot” image , showing Earth from about 6 billion kilometers (3.7 billion miles) away. As of 2021 , Voyager 1 is about 155 astronomical units (14.4 billion miles) from Earth, and Voyager 2 is nearly 129 astronomical units (12 billion miles) away.

The golden records

Each Voyager spacecraft has a golden phonograph record affixed to its side, intended as time capsules from Earth to any extraterrestrial life that might find the probes sometime in the distant future. They are inscribed with a message from Jimmy Carter, the U.S. President at the time of launch, which reads: “This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.”

The covers of the records have several images inscribed, including visual instructions on how to play them, a map of our solar system’s location with respect to a set of 14 pulsars, and a drawing of a hydrogen atom. They are plated with uranium – its rate of decay will allow any future discoverers of either of the records to calculate when they were created.

The records’ contents were selected by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan. Each contains 115 images, including scientific diagrams of the solar system and its planets, the flora and fauna of Earth, and examples of human culture. There are natural sounds, including breaking surf and birdsong, spoken greetings in 55 languages, an hour of brainwave recordings, and an eclectic selection of music ranging from Beethoven to Chuck Berry to a variety of folk music.

Learn more Voyager Mission Status Bulletin Archives Experience A Message From Earth - Inspired by the Voyager Golden Record Neptune, planet of wind and ice

Support missions like Voyager 1 and 2

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

The twin Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are exploring where nothing from Earth has flown before. Continuing on their more-than-45-year journey since their 1977 launches, they each are much farther away from Earth and the Sun than Pluto.

Quick Facts

Voyager 2 launched on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard a Titan-Centaur rocket. On September 5, Voyager 1 launched, also from Cape Canaveral aboard a Titan-Centaur rocket.

Between them, Voyager 1 and 2 explored all the giant planets of our outer solar system, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune; 48 of their moons; and the unique system of rings and magnetic fields those planets possess.

The Voyager spacecraft are the third and fourth human spacecraft to fly beyond all the planets in our solar system. Pioneers 10 and 11 preceded Voyager in outstripping the gravitational attraction of the Sun.

Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock in December 2004 at about 94 AU from the Sun while Voyager 2 crossed it in August 2007 at about 84 AU.

Both Voyager spacecrafts carry a greeting to any form of life, should that be encountered. The message is carried by a phonograph record - -a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

In August 2012, Voyager 1 made the historic entry into interstellar space, the region between stars, filled with material ejected by the death of nearby stars millions of years ago. Voyager 2 entered interstellar space on November 5, 2018 and scientists hope to learn more about this region. Both spacecraft are still sending scientific information about their surroundings through the Deep Space Network, or DSN.

The primary mission was the exploration of Jupiter and Saturn. After making a string of discoveries there — such as active volcanoes on Jupiter's moon Io and intricacies of Saturn's rings — the mission was extended. Voyager 2 went on to explore Uranus and Neptune, and is still the only spacecraft to have visited those outer planets. The adventurers' current mission, the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM), will explore the outermost edge of the Sun's domain. And beyond.

Learn about Voyagers' mission status: where they are in the space, the time required to communicate with them, and a lot more.

Learn about the five science investigation teams, the four operating instruments on-board and the science data being returned to Earth.

The Voyager spacecraft have been exploring for decades. Dive deep into the journey with this interactive timeline.

Interact in 3D. Take a deeper look at the sophisticated systems and instruments that deliver the stunning science and images.

Interstellar Mission

The mission objective of the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM) is to extend the NASA exploration of the solar system beyond the neighborhood of the outer planets to the outer limits of the Sun's sphere of influence, and possibly beyond.

Planetary Voyage

The twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were launched by NASA in separate months in the summer of 1977 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. As originally designed, the Voyagers were to conduct closeup studies of Jupiter and Saturn, Saturn's rings, and the larger moons of the two planets.

Questions, answers and interviews that explain the Voyager mission.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft is talking nonsense. Its friends on Earth are worried

Nell Greenfieldboyce

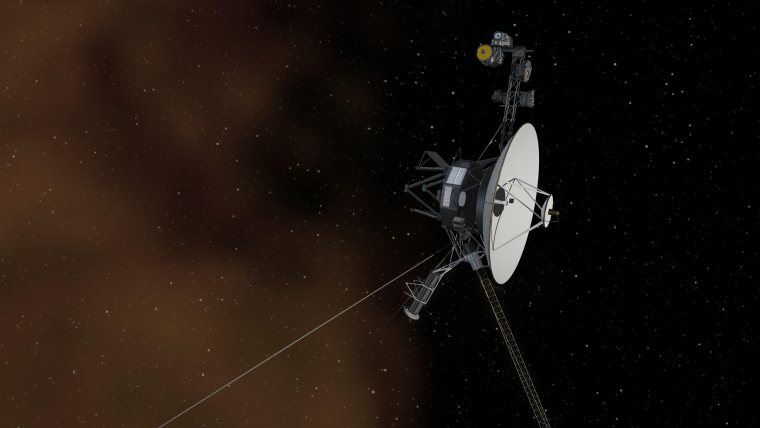

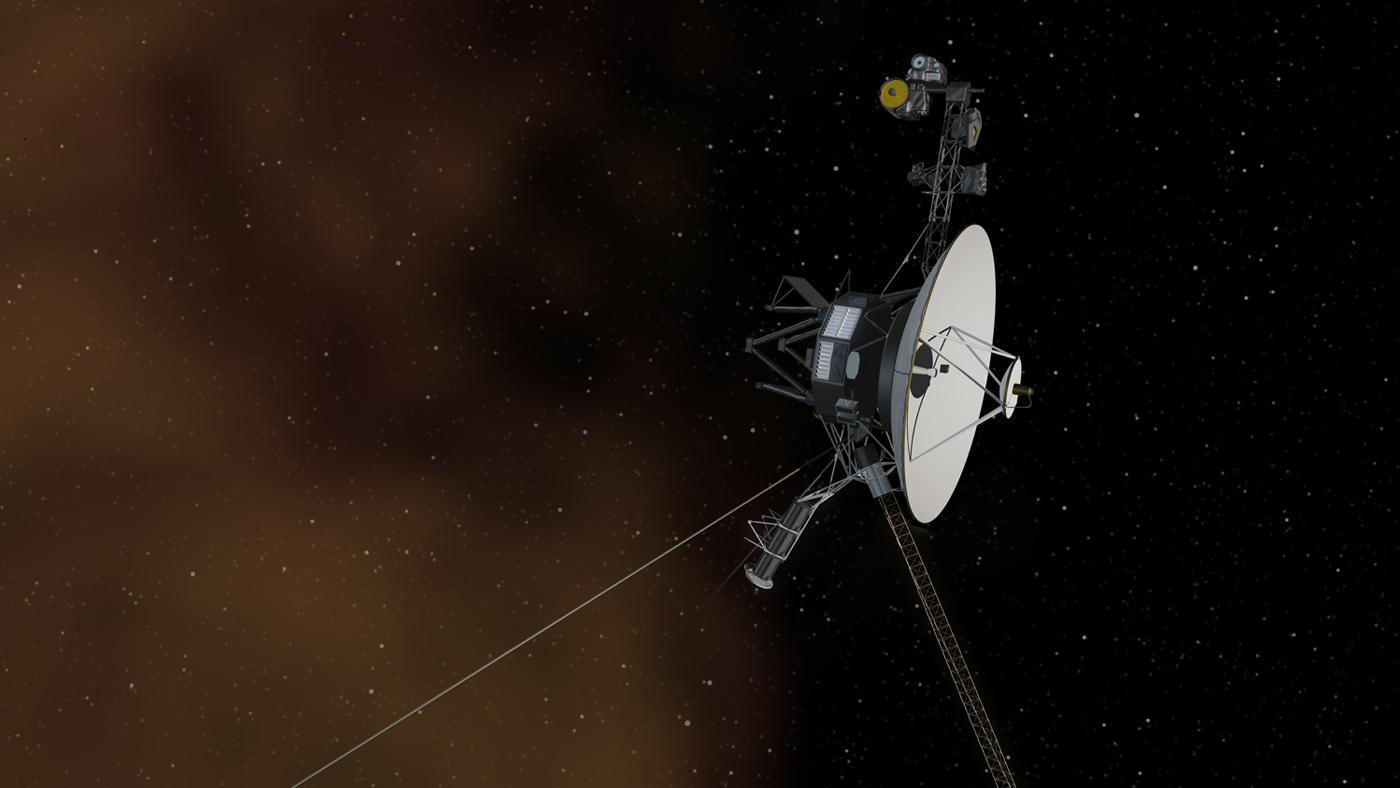

This artist's impression shows one of the Voyager spacecraft moving through the darkness of space. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

This artist's impression shows one of the Voyager spacecraft moving through the darkness of space.

The last time Stamatios "Tom" Krimigis saw the Voyager 1 space probe in person, it was the summer of 1977, just before it launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Now Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles away, beyond what many consider to be the edge of the solar system. Yet the on-board instrument Krimigis is in charge of is still going strong.

"I am the most surprised person in the world," says Krimigis — after all, the spacecraft's original mission to Jupiter and Saturn was only supposed to last about four years.

These days, though, he's also feeling another emotion when he thinks of Voyager 1.

"Frankly, I'm very worried," he says.

Ever since mid-November, the Voyager 1 spacecraft has been sending messages back to Earth that don't make any sense. It's as if the aging spacecraft has suffered some kind of stroke that's interfering with its ability to speak.

"It basically stopped talking to us in a coherent manner," says Suzanne Dodd of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who has been the project manager for the Voyager interstellar mission since 2010. "It's a serious problem."

Instead of sending messages home in binary code, Voyager 1 is now just sending back alternating 1s and 0s. Dodd's team has tried the usual tricks to reset things — with no luck.

It looks like there's a problem with the onboard computer that takes data and packages it up to send back home. All of this computer technology is primitive compared to, say, the key fob that unlocks your car, says Dodd.

"The button you press to open the door of your car, that has more compute power than the Voyager spacecrafts do," she says. "It's remarkable that they keep flying, and that they've flown for 46-plus years."

Each of the Voyager probes carries an American flag and a copy of a golden record that can play greetings in many languages. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

Each of the Voyager probes carries an American flag and a copy of a golden record that can play greetings in many languages.

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, have outlasted many of those who designed and built them. So to try to fix Voyager 1's current woes, the dozen or so people on Dodd's team have had to pore over yellowed documents and old mimeographs.

"They're doing a lot of work to try and get into the heads of the original developers and figure out why they designed something the way they did and what we could possibly try that might give us some answers to what's going wrong with the spacecraft," says Dodd.

She says that they do have a list of possible fixes. As time goes on, they'll likely start sending commands to Voyager 1 that are more bold and risky.

"The things that we will do going forward are probably more challenging in the sense that you can't tell exactly if it's going to execute correctly — or if you're going to maybe do something you didn't want to do, inadvertently," says Dodd.

Linda Spilker , who serves as the Voyager mission's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says that when she comes to work she sees "all of these circuit diagrams up on the wall with sticky notes attached. And these people are just having a great time trying to troubleshoot, you know, the 60's and 70's technology."

"I'm cautiously optimistic," she says. "There's a lot of creativity there."

Still, this is a painstaking process that could take weeks, or even months. Voyager 1 is so distant, it takes almost a whole day for a signal to travel out there, and then a whole day for its response to return.

"We'll keep trying," says Dodd, "and it won't be quick."

In the meantime, Voyager's 1 discombobulation is a bummer for researchers like Stella Ocker , an astronomer with Caltech and the Carnegie Observatories

"We haven't been getting science data since this anomaly started," says Ocker, "and what that means is that we don't know what the environment that the spacecraft is traveling through looks like."

After 35 Years, Voyager Nears Edge Of Solar System

That interstellar environment isn't just empty darkness, she says. It contains stuff like gas, dust, and cosmic rays. Only the twin Voyager probes are far out enough to sample this cosmic stew.

"The science that I'm really interested in doing is actually only possible with Voyager 1," says Ocker, because Voyager 2 — despite being generally healthy for its advanced age — can't take the particular measurements she needs for her research.

Even if NASA's experts and consultants somehow come up with a miraculous plan that can get Voyager 1 back to normal, its time is running out.

The two Voyager probes are powered by plutonium, but that power system will eventually run out of juice. Mission managers have turned off heaters and taken other measures to conserve power and extend the Voyager probes' lifespan.

"My motto for a long time was 50 years or bust," says Krimigis with a laugh, "but we're sort of approaching that."

In a couple of years, the ebbing power supply will force managers to start turning off science instruments, one by one. The very last instrument might keep going until around 2030 or so.

When the power runs out and the probes are lifeless, Krimigis says both of these legendary space probes will basically become "space junk."

"It pains me to say that," he says. While Krimigis has participated in space missions to every planet, he says the Voyager program has a special place in his heart.

Spilker points out that each spacecraft will keep moving outward, carrying its copy of a golden record that has recorded greetings in many languages, along with the sounds of Earth.

"The science mission will end. But a part of Voyager and a part of us will continue on in the space between the stars," says Spilker, noting that the golden records "may even outlast humanity as we know it."

Krimigis, though, doubts that any alien will ever stumble across a Voyager probe and have a listen.

"Space is empty," he says, "and the probability of Voyager ever running into a planet is probably slim to none."

It will take about 40,000 years for Voyager 1 to approach another star; it will come within 1.7 light years of what NASA calls "an obscure star in the constellation Ursa Minor" — also known as the Little Dipper.

If NASA greenlights this interstellar mission, it could last 100 years

Knowing that the Voyager probes are running out of time, scientists have been drawing up plans for a new mission that, if funded and launched by NASA, would send another probe even farther out into the space between stars.

"If it happens, it would launch in the 2030s," says Ocker, "and it would reach twice as far as Voyager 1 in just 50 years."

- space exploration

- space science

For IEEE Members

Ieee spectrum, follow ieee spectrum, support ieee spectrum, enjoy more free content and benefits by creating an account, saving articles to read later requires an ieee spectrum account, the institute content is only available for members, downloading full pdf issues is exclusive for ieee members, downloading this e-book is exclusive for ieee members, access to spectrum 's digital edition is exclusive for ieee members, following topics is a feature exclusive for ieee members, adding your response to an article requires an ieee spectrum account, create an account to access more content and features on ieee spectrum , including the ability to save articles to read later, download spectrum collections, and participate in conversations with readers and editors. for more exclusive content and features, consider joining ieee ., join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to all of spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, join the world’s largest professional organization devoted to engineering and applied sciences and get access to this e-book plus all of ieee spectrum’s articles, archives, pdf downloads, and other benefits. learn more →, access thousands of articles — completely free, create an account and get exclusive content and features: save articles, download collections, and talk to tech insiders — all free for full access and benefits, join ieee as a paying member., how nasa is hacking voyager 1 back to life, engineers found space in the geriatric spacecraft’s memory to deal with a stuck bit.

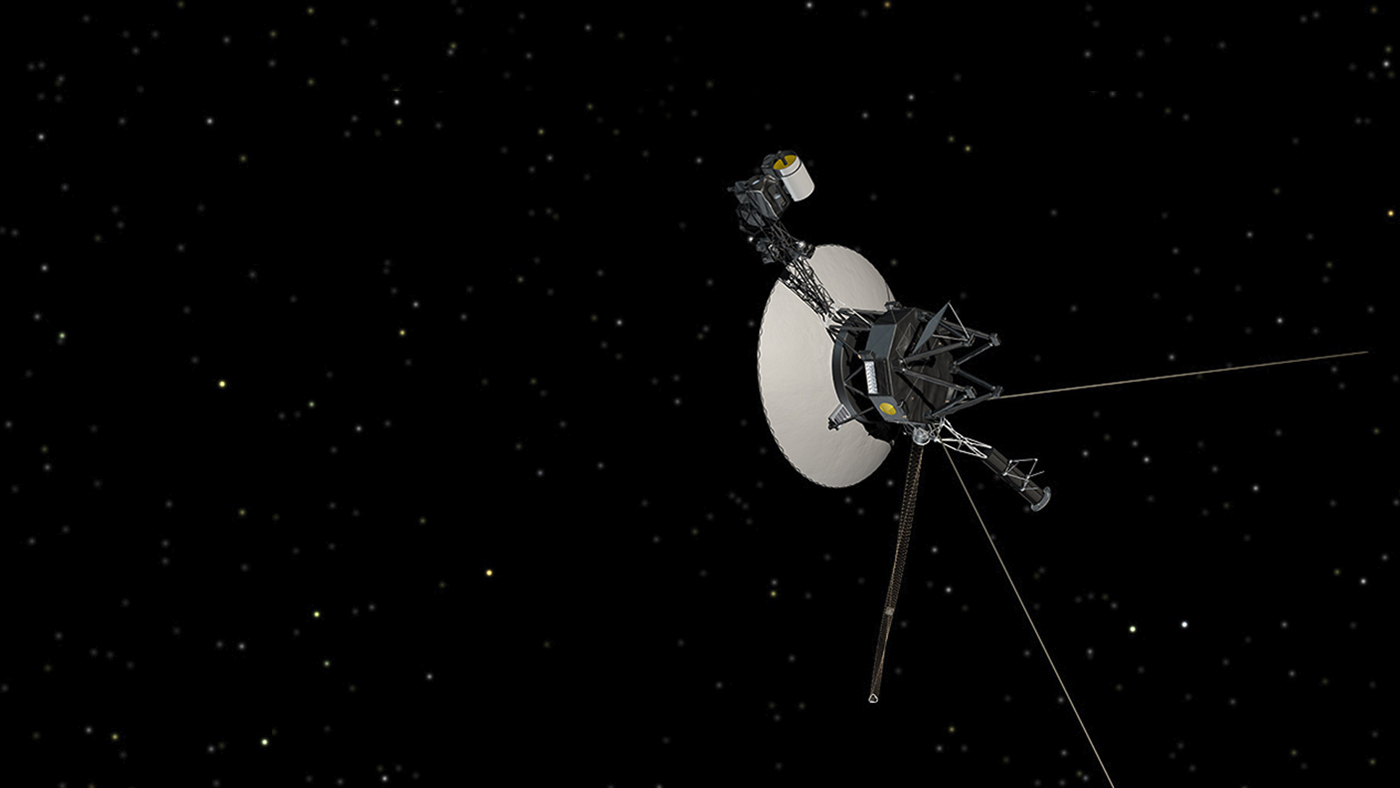

Voyager 1 whizzes through interstellar space at 17 kilometers per second.

On 14 November 2023, NASA’s interstellar space probe Voyager 1 began sending gibberish back to Earth. For five months, the spacecraft transmitted unusable data equivalent to a dial tone.

In March, engineers discovered the cause of the communication snafu: a stuck bit in one of the chips comprising part of Voyager’s onboard memory. The chip contained lines of code used by the flight data subsystem (FDS), one of three computers aboard the spacecraft and the one that is responsible for collecting and packaging data before sending it back to Earth.

JPL engineers sent a command through the Deep Space Network on 18 April to relocate the affected section of code to another part of the spacecraft’s memory, hoping to fix the glitch in the archaic computer system. Roughly 22.5 hours later, the radio signal reached Voyager in interstellar space, and by the following day it was clear the command had worked. Voyager began returning useful data again on 20 April.

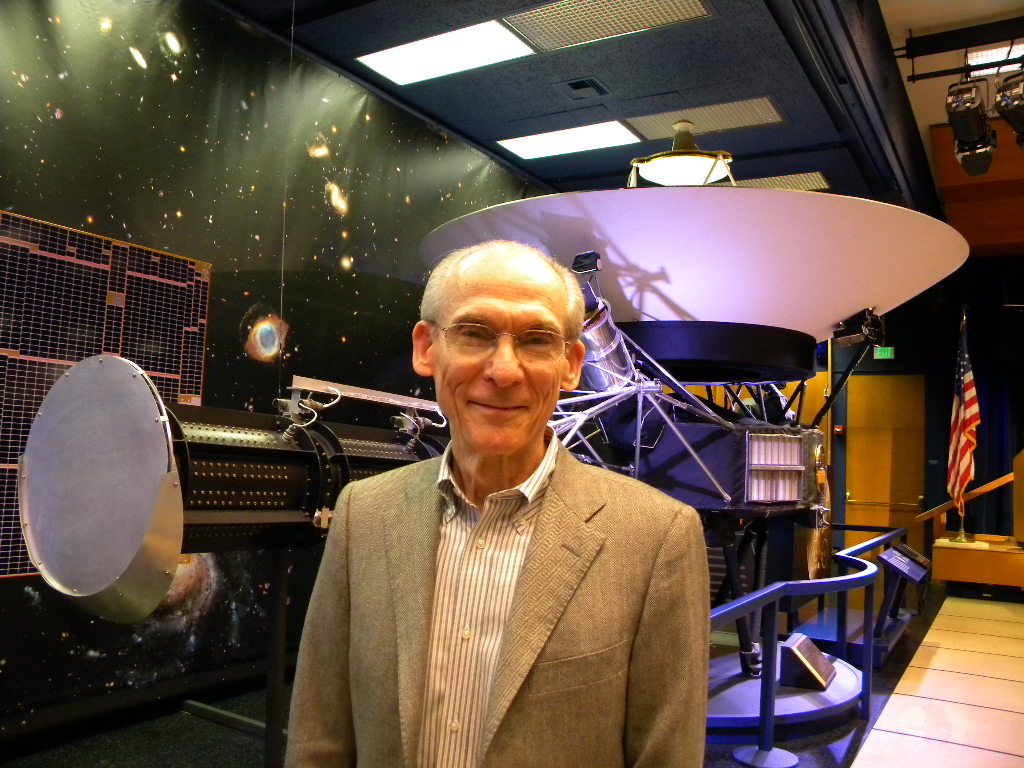

NASA engineers managed to diagnose and repair Voyager 1 from 24 billion kilometers away—all while working within the constraints of the vintage technology. “We had some people left that we could rely on [who] could remember working on bits of the hardware,” says project scientist Linda Spilker . “But a lot of it was going back through old memos, like an archeological dig to try and find information on the best way to proceed.”

Minuscule Memory

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2—which also remains operational—were launched nearly 50 years ago, in 1977, to tour the solar system. Both spacecraft far surpassed their original missions of visiting Jupiter and Saturn, and in 2012, entered interstellar space .

“That mission literally rewrote the textbooks on the solar system,” says Jim Bell , a planetary scientist at Arizona State University and author of a book recounting 40 years of the mission. “We’ve never sent anything out that far, so every bit of data they send back is new.” The 1960s and 1970s technology, on the other hand, is now ancient.

Decades after the tech went out of vogue, the FDS still uses assembly language and 16-bit words . “These are two positively geriatric spacecraft,” says Todd Barber , a propulsion engineer for Voyager. Working to fix the issues, he says, is “like palliative care.”

To first diagnose the issue, NASA’s engineers first tried turning on and off different instruments, says Spilker. When that proved unsuccessful, they initiated a full memory readout of the FDS. “That’s what led to us finding that piece of hardware that had failed and that 256-bit chunk of memory,” she says. In one chip, the engineers found a stuck bit, fixed at the same binary value. It became clear that the chip was irreparable, so the team had to identify and relocate the affected code.

However, no single location was large enough to accommodate the extra 256 bits. “The size of the memory was the biggest challenge in this anomaly,” says Spilker. Voyager’s computers each have a mere 69.63 kilobytes of memory.

To begin fixing the issue, the team searched for corners of Voyager’s memory to place segments of code that would allow for the return of engineering data, which includes information about the status of science instruments and the spacecraft itself. One way the engineers freed up extra space was by identifying processes no longer used. For example, Voyager was programmed with several data modes—the rate at which data is sent back to Earth—because the spacecraft could transmit data much faster when it was closer to Earth. At Jupiter, the spacecraft transmitted data at 115.2 kilobits per second; now, that rate has slowed to 40 bits per second, and faster modes can be overwritten. However, the engineers have to be careful to ensure they don’t delete code that is used by multiple data modes.

Having successfully returned engineering data, the team is working to relocate the rest of the affected code in the coming weeks. “We’re having to look a little harder to find the space and make some key decisions about what to overwrite,” says Spilker. When their work is completed, the Voyager team hopes to return new science data, though unfortunately, all data from the anomaly period was lost.

Built to Last

The cause of the stuck bit is a mystery, but it’s likely the chip either wore out with age or was hit by a highly energetic particle from a cosmic ray. Having entered interstellar space, “Voyager is out bathed in the cosmic rays,” Spilker says. Luckily, the spacecraft was built to take it, with its electronic components shielded from the large amount of radiation present at Jupiter. “That’s serving us quite well now in the interstellar medium.”

When Voyager was built, the 12-year trip to Uranus and Neptune alone was a “seemingly impossible goal for a 1977 launch,” says Barber. The longevity of Voyager is a testament of its engineering, which accounted for many contingencies and added redundancy. The mission also included several firsts, for example, as the first spacecraft with computers able to hold data temporarily using volatile CMOS memory. (An 8-track digital tape recorder onboard stores data when collected at a high rate.)

Importantly, it was also the first mission with a reprogrammable computer. “We take it for granted now,” Bell says, but before Voyager, it wasn’t possible to adjust software in-flight. This capability proved essential when the mission was extended, as well as when issues arise.

Going forward, the Voyager team expects to encounter additional problems in the aging spacecraft—though they hope to make it to the 50-year anniversary before the next one. “With each anomaly, we just learn more about how to work with the spacecraft and are just amazed at the capabilities that the engineers built into it using that 1960s and ’70s technology,” Spilker says. “It’s just amazing.”

- 50 Years Later, This Apollo-Era Antenna Still Talks to Voyager 2 ›

- Voyager 1 Hasn't Really Left The Solar System, But That's OK ›

- Mission Status - Voyager ›

- Voyager 1 ›

Gwendolyn Rak is a contributor to IEEE Spectrum .

I worked with COSMAC and similar rudimentary processors in the early 70’s so was curious to learn how they solved this problem. The nearest it got was “they initiated a full memory readout of the FDS.” But if the telemetry was faulty how did the get the readout?

"Snake-like" Probe Images Arteries from Within

How to put a data center in a shoebox, mri sheds its shielding and superconducting magnets, related stories, satellite radar sharpens ukraine dam collapse questions, the most hackable handheld ham radio yet, faster, more secure photonic chip boosts ai training.

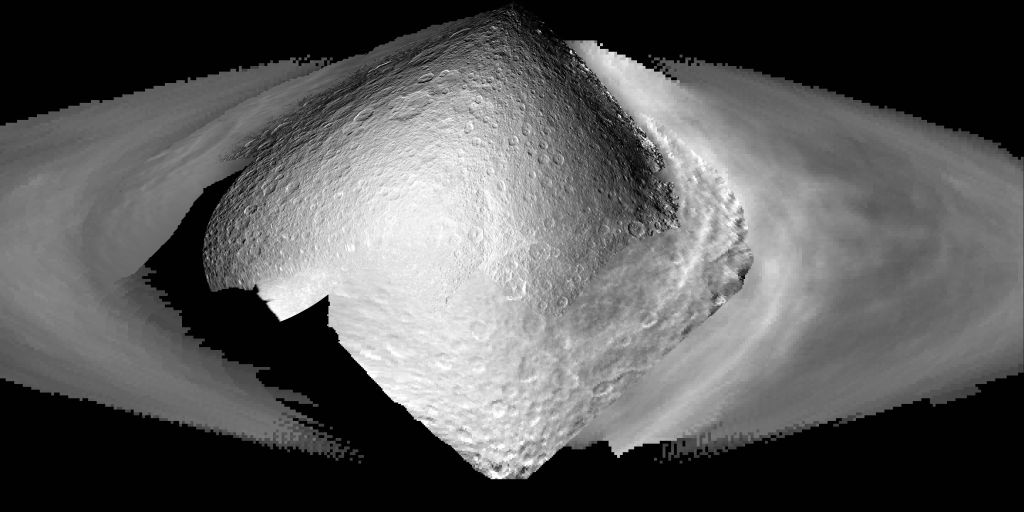

Saturn Voyager Airbrush Global Products

The following products were the first step of cartography planning in support of the Cassini-Huygens mission to the Saturian System. Five of Saturans moons are linked below in a standard cartographic format. This includes mapping information such as latitude and longitude ranges, image resolutions and projection information. The data included in these maps was collected by both Voyager I and Voyager II missions. The Cassini-Huygens spacecraft would target these moons and others during the mission.

Dione Voyager Airbrush Mosaic 610m

This image mosaic is one of several products created as the first step of cartography planning in support of the Cassini-Huygens Mission to Saturn & Titan. The data included in this mosaic

Enceladus Voyager Airbrush Mosaic 273m

This image product reflects a scan of a 1982 airbrush rendition of Enceladus. Reference: U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1982. Preliminary Pictorial map of Enceladus. U.S. Geol. Surv. Misc. Invest. Ser. Map I-1485, scale

Iapetus Voyager Airbrush Global Mosaic 783m

This image mosaic is one of several products created as the first step of cartography planning in support of the Cassini-Huygens Mission to Saturn & Titan. The data included in these mosaics

Mimas Airbrush Shaded Relief

Rhea Voyager Global Mosaic 833m

Product Information: This global digital mosaic uses 25 images from Voyager 1 and is a sinusoidal projection with a resolution of 833 meters per pixel (m). Digital image processing of the Voyager

Tethys Voyager Global Airbrush Mosaic 572m

The data included in this mosaic were collected by both Voyager I and Voyager II missions and then airbrushed for cosmetic purposes.

Related Collections

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

The Voyager Planetary Mission

The twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were launched by NASA in separate months in the summer of 1977 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. As originally designed, the Voyagers were to conduct closeup studies of Jupiter and Saturn, Saturn's rings, and the larger moons of the two planets.

To accomplish their two-planet mission, the spacecraft were built to last five years. But as the mission went on, and with the successful achievement of all its objectives, the additional flybys of the two outermost giant planets, Uranus and Neptune, proved possible -- and irresistible to mission scientists and engineers at the Voyagers' home at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

As the spacecraft flew across the solar system, remote-control reprogramming was used to endow the Voyagers with greater capabilities than they possessed when they left the Earth. Their two-planet mission became four. Their five-year lifetimes stretched to 12 and more.

Eventually, between them, Voyager 1 and 2 would explore all the giant outer planets of our solar system, 48 of their moons, and the unique systems of rings and magnetic fields those planets possess.

Had the Voyager mission ended after the Jupiter and Saturn flybys alone, it still would have provided the material to rewrite astronomy textbooks. But having doubled their already ambitious itineraries, the Voyagers returned to Earth information over the years that has revolutionized the science of planetary astronomy, helping to resolve key questions while raising intriguing new ones about the origin and evolution of the planets in our solar system.

History of the Voyager Mission

The Voyager mission was designed to take advantage of a rare geometric arrangement of the outer planets in the late 1970s and the 1980s which allowed for a four-planet tour for a minimum of propellant and trip time. This layout of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, which occurs about every 175 years, allows a spacecraft on a particular flight path to swing from one planet to the next without the need for large onboard propulsion systems. The flyby of each planet bends the spacecraft's flight path and increases its velocity enough to deliver it to the next destination. Using this "gravity assist" technique, first demonstrated with NASA's Mariner 10 Venus/Mercury mission in 1973-74, the flight time to Neptune was reduced from 30 years to 12.

While the four-planet mission was known to be possible, it was deemed to be too expensive to build a spacecraft that could go the distance, carry the instruments needed and last long enough to accomplish such a long mission. Thus, the Voyagers were funded to conduct intensive flyby studies of Jupiter and Saturn only. More than 10,000 trajectories were studied before choosing the two that would allow close flybys of Jupiter and its large moon Io, and Saturn and its large moon Titan; the chosen flight path for Voyager 2 also preserved the option to continue on to Uranus and Neptune.

From the NASA Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida, Voyager 2 was launched first, on August 20, 1977; Voyager 1 was launched on a faster, shorter trajectory on September 5, 1977. Both spacecraft were delivered to space aboard Titan-Centaur expendable rockets.

The prime Voyager mission to Jupiter and Saturn brought Voyager 1 to Jupiter on March 5, 1979, and Saturn on November 12, 1980, followed by Voyager 2 to Jupiter on July 9, 1979, and Saturn on August 25, 1981.

Voyager 1's trajectory, designed to send the spacecraft closely past the large moon Titan and behind Saturn's rings, bent the spacecraft's path inexorably northward out of the ecliptic plane -- the plane in which most of the planets orbit the Sun. Voyager 2 was aimed to fly by Saturn at a point that would automatically send the spacecraft in the direction of Uranus.

After Voyager 2's successful Saturn encounter, it was shown that Voyager 2 would likely be able to fly on to Uranus with all instruments operating. NASA provided additional funding to continue operating the two spacecraft and authorized JPL to conduct a Uranus flyby. Subsequently, NASA also authorized the Neptune leg of the mission, which was renamed the Voyager Neptune Interstellar Mission.

Voyager 2 encountered Uranus on January 24, 1986, returning detailed photos and other data on the planet, its moons, magnetic field and dark rings. Voyager 1, meanwhile, continues to press outward, conducting studies of interplanetary space. Eventually, its instruments may be the first of any spacecraft to sense the heliopause -- the boundary between the end of the Sun's magnetic influence and the beginning of interstellar space. (Voyager 1 entered Interstellar Space on August 25, 2012.)

Following Voyager 2's closest approach to Neptune on August 25, 1989, the spacecraft flew southward, below the ecliptic plane and onto a course that will take it, too, to interstellar space. Reflecting the Voyagers' new transplanetary destinations, the project is now known as the Voyager Interstellar Mission.

Voyager 1 is now leaving the solar system, rising above the ecliptic plane at an angle of about 35 degrees at a rate of about 520 million kilometers (about 320 million miles) a year. Voyager 2 is also headed out of the solar system, diving below the ecliptic plane at an angle of about 48 degrees and a rate of about 470 million kilometers (about 290 million miles) a year.

Both spacecraft will continue to study ultraviolet sources among the stars, and the fields and particles instruments aboard the Voyagers will continue to search for the boundary between the Sun's influence and interstellar space. The Voyagers are expected to return valuable data for two or three more decades. Communications will be maintained until the Voyagers' nuclear power sources can no longer supply enough electrical energy to power critical subsystems.

The cost of the Voyager 1 and 2 missions -- including launch, mission operations from launch through the Neptune encounter and the spacecraft's nuclear batteries (provided by the Department of Energy) -- is $865 million. NASA budgeted an additional $30 million to fund the Voyager Interstellar Mission for two years following the Neptune encounter.

Voyagers 1 and 2 are identical spacecraft. Each is equipped with instruments to conduct 10 different experiments. The instruments include television cameras, infrared and ultraviolet sensors, magnetometers, plasma detectors, and cosmic-ray and charged-particle sensors. In addition, the spacecraft radio is used to conduct experiments.

The Voyagers travel too far from the Sun to use solar panels; instead, they were equipped with power sources called radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). These devices, used on other deep space missions, convert the heat produced from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity to power the spacecraft instruments, computers, radio and other systems.

The spacecraft are controlled and their data returned through the Deep Space Network (DSN), a global spacecraft tracking system operated by JPL for NASA. DSN antenna complexes are located in California's Mojave Desert; near Madrid, Spain; and in Tidbinbilla, near Canberra, Australia.

The Voyager project manager for the Interstellar Mission is George P. Textor of JPL. The Voyager project scientist is Dr. Edward C. Stone of the California Institute of Technology. The assistant project scientist for the Jupiter flyby was Dr. Arthur L. Lane, followed by Dr. Ellis D. Miner for the Saturn, Uranus and Neptune encounters. Both are with JPL.

JUPITER Voyager 1 made its closest approach to Jupiter on March 5, 1979, and Voyager 2 followed with its closest approach occurring on July 9, 1979. The first spacecraft flew within 277,400 kilometers (172,368 miles) of the planet's cloud tops, and Voyager 2 came within 650,180 kilometers (404,003 miles).

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system, composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, with small amounts of methane, ammonia, water vapor, traces of other compounds and a core of melted rock and ice. Colorful latitudinal bands and atmospheric clouds and storms illustrate Jupiter's dynamic weather system. The giant planet is now known to possess 16 moons. The planet completes one orbit of the Sun each 11.8 years and its day is 9 hours, 55 minutes.

Although astronomers had studied Jupiter through telescopes on Earth for centuries, scientists were surprised by many of the Voyager findings.

The Great Red Spot was revealed as a complex storm moving in a counterclockwise direction. An array of other smaller storms and eddies were found throughout the banded clouds.

Discovery of active volcanism on the satellite Io was easily the greatest unexpected discovery at Jupiter. It was the first time active volcanoes had been seen on another body in the solar system. Together, the Voyagers observed the eruption of nine volcanoes on Io, and there is evidence that other eruptions occurred between the Voyager encounters.

Plumes from the volcanoes extend to more than 300 kilometers (190 miles) above the surface. The Voyagers observed material ejected at velocities up to a kilometer per second.

Io's volcanoes are apparently due to heating of the satellite by tidal pumping. Io is perturbed in its orbit by Europa and Ganymede, two other large satellites nearby, then pulled back again into its regular orbit by Jupiter. This tug-of-war results in tidal bulging as great as 100 meters (330 feet) on Io's surface, compared with typical tidal bulges on Earth of one meter (three feet).

It appears that volcanism on Io affects the entire jovian system, in that it is the primary source of matter that pervades Jupiter's magnetosphere -- the region of space surrounding the planet influenced by the jovian magnetic field. Sulfur, oxygen and sodium, apparently erupted by Io's many volcanoes and sputtered off the surface by impact of high-energy particles, were detected as far away as the outer edge of the magnetosphere millions of miles from the planet itself.

Europa displayed a large number of intersecting linear features in the low-resolution photos from Voyager 1. At first, scientists believed the features might be deep cracks, caused by crustal rifting or tectonic processes. The closer high-resolution photos from Voyager 2, however, left scientists puzzled: The features were so lacking in topographic relief that as one scientist described them, they "might have been painted on with a felt marker." There is a possibility that Europa may be internally active due to tidal heating at a level one-tenth or less than that of Io. Europa is thought to have a thin crust (less than 30 kilometers or 18 miles thick) of water ice, possibly floating on a 50-kilometer-deep (30-mile) ocean.

Ganymede turned out to be the largest moon in the solar system, with a diameter measuring 5,276 kilometers (3,280 miles). It showed two distinct types of terrain -- cratered and grooved -- suggesting to scientists that Ganymede's entire icy crust has been under tension from global tectonic processes.

Callisto has a very old, heavily cratered crust showing remnant rings of enormous impact craters. The largest craters have apparently been erased by the flow of the icy crust over geologic time. Almost no topographic relief is apparent in the ghost remnants of the immense impact basins, identifiable only by their light color and the surrounding subdued rings of concentric ridges.

A faint, dusty ring of material was found around Jupiter. Its outer edge is 129,000 kilometers (80,000 miles) from the center of the planet, and it extends inward about 30,000 kilometers (18,000 miles).

Two new, small satellites, Adrastea and Metis, were found orbiting just outside the ring. A third new satellite, Thebe, was discovered between the orbits of Amalthea and Io.

Jupiter's rings and moons exist within an intense radiation belt of electrons and ions trapped in the planet's magnetic field. These particles and fields comprise the jovian magnetosphere, or magnetic environment, which extends three to seven million kilometers toward the Sun, and stretches in a windsock shape at least as far as Saturn's orbit -- a distance of 750 million kilometers (460 million miles).

As the magnetosphere rotates with Jupiter, it sweeps past Io and strips away about 1,000 kilograms (one ton) of material per second. The material forms a torus, a doughnut-shaped cloud of ions that glow in the ultraviolet. Some of the torus's heavy ions migrate outward, and their pressure inflates the Jovian magnetosphere, while the more energetic sulfur and oxygen ions fall along the magnetic field into the planet's atmosphere, resulting in auroras.

Io acts as an electrical generator as it moves through Jupiter's magnetic field, developing 400,000 volts across its diameter and generating an electric current of 3 million amperes that flows along the magnetic field to the planet's ionosphere.

SATURN The Voyager 1 and 2 Saturn flybys occurred nine months apart, with the closest approaches falling on November 12 and August 25, 1981. Voyager 1 flew within 64,200 kilometers (40,000 miles) of the cloud tops, while Voyager 2 came within 41,000 kilometers (26,000 miles).

Saturn is the second largest planet in the solar system. It takes 29.5 Earth years to complete one orbit of the Sun, and its day was clocked at 10 hours, 39 minutes. Saturn is known to have at least 17 moons and a complex ring system. Like Jupiter, Saturn is mostly hydrogen and helium. Its hazy yellow hue was found to be marked by broad atmospheric banding similar to but much fainter than that found on Jupiter. Close scrutiny by Voyager's imaging systems revealed long-lived ovals and other atmospheric features generally smaller than those on Jupiter.

Perhaps the greatest surprises and the most puzzles were found by the Voyagers in Saturn's rings. It is thought that the rings formed from larger moons that were shattered by impacts of comets and meteoroids. The resulting dust and boulder- to house-size particles have accumulated in a broad plane around the planet varying in density.

The irregular shapes of Saturn's eight smallest moons indicates that they too are fragments of larger bodies. Unexpected structure such as kinks and spokes were found in addition to thin rings and broad, diffuse rings not observed from Earth. Much of the elaborate structure of some of the rings is due to the gravitational effects of nearby satellites. This phenomenon is most obviously demonstrated by the relationship between the F-ring and two small moons that "shepherd" the ring material. The variation in the separation of the moons from the ring may the ring's kinked appearance. Shepherding moons were also found by Voyager 2 at Uranus.

Radial, spoke-like features in the broad B-ring were found by the Voyagers. The features are believed to be composed of fine, dust-size particles. The spokes were observed to form and dissipate in time-lapse images taken by the Voyagers. While electrostatic charging may create spokes by levitating dust particles above the ring, the exact cause of the formation of the spokes is not well understood.

Winds blow at extremely high speeds on Saturn -- up to 1,800 kilometers per hour (1,100 miles per hour). Their primarily easterly direction indicates that the winds are not confined to the top cloud layer but must extend at least 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) downward into the atmosphere. The characteristic temperature of the atmosphere is 95 kelvins.

Saturn holds a wide assortment of satellites in its orbit, ranging from Phoebe, a small moon that travels in a retrograde orbit and is probably a captured asteroid, to Titan, the planet-sized moon with a thick nitrogen-methane atmosphere. Titan's surface temperature and pressure are 94 kelvins (-292 Fahrenheit) and 1.5 atmospheres. Photochemistry converts some atmospheric methane to other organic molecules, such as ethane, that is thought to accumulate in lakes or oceans. Other more complex hydrocarbons form the haze particles that eventually fall to the surface, coating it with a thick layer of organic matter. The chemistry in Titan's atmosphere may strongly resemble that which occurred on Earth before life evolved.

The most active surface of any moon seen in the Saturn system was that of Enceladus. The bright surface of this moon, marked by faults and valleys, showed evidence of tectonically induced change. Voyager 1 found the moon Mimas scarred with a crater so huge that the impact that caused it nearly broke the satellite apart.

Saturn's magnetic field is smaller than Jupiter's, extending only one or two million kilometers. The axis of the field is almost perfectly aligned with the rotation axis of the planet.

URANUS In its first solo planetary flyby, Voyager 2 made its closest approach to Uranus on January 24, 1986, coming within 81,500 kilometers (50,600 miles) of the planet's cloud tops.

Uranus is the third largest planet in the solar system. It orbits the Sun at a distance of about 2.8 billion kilometers (1.7 billion miles) and completes one orbit every 84 years. The length of a day on Uranus as measured by Voyager 2 is 17 hours, 14 minutes.

Uranus is distinguished by the fact that it is tipped on its side. Its unusual position is thought to be the result of a collision with a planet-sized body early in the solar system's history. Given its odd orientation, with its polar regions exposed to sunlight or darkness for long periods, scientists were not sure what to expect at Uranus.

Voyager 2 found that one of the most striking influences of this sideways position is its effect on the tail of the magnetic field, which is itself tilted 60 degrees from the planet's axis of rotation. The magnetotail was shown to be twisted by the planet's rotation into a long corkscrew shape behind the planet.

The presence of a magnetic field at Uranus was not known until Voyager's arrival. The intensity of the field is roughly comparable to that of Earth's, though it varies much more from point to point because of its large offset from the center of Uranus. The peculiar orientation of the magnetic field suggests that the field is generated at an intermediate depth in the interior where the pressure is high enough for water to become electrically conducting.

Radiation belts at Uranus were found to be of an intensity similar to those at Saturn. The intensity of radiation within the belts is such that irradiation would quickly darken (within 100,000 years) any methane trapped in the icy surfaces of the inner moons and ring particles. This may have contributed to the darkened surfaces of the moons and ring particles, which are almost uniformly gray in color.

A high layer of haze was detected around the sunlit pole, which also was found to radiate large amounts of ultraviolet light, a phenomenon dubbed "dayglow." The average temperature is about 60 kelvins (-350 degrees Fahrenheit). Surprisingly, the illuminated and dark poles, and most of the planet, show nearly the same temperature at the cloud tops.

Voyager found 10 new moons, bringing the total number to 15. Most of the new moons are small, with the largest measuring about 150 kilometers (about 90 miles) in diameter.

The moon Miranda, innermost of the five large moons, was revealed to be one of the strangest bodies yet seen in the solar system. Detailed images from Voyager's flyby of the moon showed huge fault canyons as deep as 20 kilometers (12 miles), terraced layers, and a mixture of old and young surfaces. One theory holds that Miranda may be a reaggregration of material from an earlier time when the moon was fractured by an violent impact.

The five large moons appear to be ice-rock conglomerates like the satellites of Saturn. Titania is marked by huge fault systems and canyons indicating some degree of geologic, probably tectonic, activity in its history. Ariel has the brightest and possibly youngest surface of all the Uranian moons and also appears to have undergone geologic activity that led to many fault valleys and what seem to be extensive flows of icy material. Little geologic activity has occurred on Umbriel or Oberon, judging by their old and dark surfaces.

All nine previously known rings were studied by the spacecraft and showed the Uranian rings to be distinctly different from those at Jupiter and Saturn. The ring system may be relatively young and did not form at the same time as Uranus. Particles that make up the rings may be remnants of a moon that was broken by a high-velocity impact or torn up by gravitational effects.

NEPTUNE When Voyager flew within 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles) of Neptune on August 25, 1989, the planet was the most distant member of the solar system from the Sun. (Pluto once again will become most distant in 1999.)

Neptune orbits the Sun every 165 years. It is the smallest of our solar system's gas giants. Neptune is now known to have eight moons, six of which were found by Voyager. The length of a Neptunian day has been determined to be 16 hours, 6.7 minutes.

Even though Neptune receives only three percent as much sunlight as Jupiter does, it is a dynamic planet and surprisingly showed several large, dark spots reminiscent of Jupiter's hurricane-like storms. The largest spot, dubbed the Great Dark Spot, is about the size of Earth and is similar to the Great Red Spot on Jupiter. A small, irregularly shaped, eastward-moving cloud was observed "scooting" around Neptune every 16 hours or so; this "scooter," as Voyager scientists called it, could be a cloud plume rising above a deeper cloud deck.

Long, bright clouds, similar to cirrus clouds on Earth, were seen high in Neptune's atmosphere. At low northern latitudes, Voyager captured images of cloud streaks casting their shadows on cloud decks below.

The strongest winds on any planet were measured on Neptune. Most of the winds there blow westward, or opposite to the rotation of the planet. Near the Great Dark Spot, winds blow up to 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) an hour.

The magnetic field of Neptune, like that of Uranus, turned out to be highly tilted -- 47 degrees from the rotation axis and offset at least 0.55 radii (about 13,500 kilometers or 8,500 miles) from the physical center. Comparing the magnetic fields of the two planets, scientists think the extreme orientation may be characteristic of flows in the interiors of both Uranus and Neptune -- and not the result in Uranus's case of that planet's sideways orientation, or of any possible field reversals at either planet. Voyager's studies of radio waves caused by the magnetic field revealed the length of a Neptunian day. The spacecraft also detected auroras, but much weaker than those on Earth and other planets.

Triton, the largest of the moons of Neptune, was shown to be not only the most intriguing satellite of the Neptunian system, but one of the most interesting in all the solar system. It shows evidence of a remarkable geologic history, and Voyager 2 images showed active geyser-like eruptions spewing invisible nitrogen gas and dark dust particles several kilometers into the tenuous atmosphere. Triton's relatively high density and retrograde orbit offer strong evidence that Triton is not an original member of Neptune's family but is a captured object. If that is the case, tidal heating could have melted Triton in its originally eccentric orbit, and the moon might even have been liquid for as long as one billion years after its capture by Neptune.

An extremely thin atmosphere extends about 800 kilometer (500 miles) above Triton's surface. Nitrogen ice particles may form thin clouds a few kilometers above the surface. The atmospheric pressure at the surface is about 14 microbars, 1/70,000th the surface pressure on Earth. The surface temperature is about 38 kelvins (-391 degrees Fahrenheit) the coldest temperature of any body known in the solar system.

The new moons found at Neptune by Voyager are all small and remain close to Neptune's equatorial plane. Names for the new moons were selected from mythology's water deities by the International Astronomical Union, they are: Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, Proteus.

Voyager 2 solved many of the questions scientists had about Neptune's rings. Searches for "ring arcs," or partial rings, showed that Neptune's rings actually are complete, but are so diffuse and the material in them so fine that they could not be fully resolved from Earth. From the outermost in, the rings have been designated Adams, Plateau, Le Verrier and Galle.

Interstellar Mission

The spacecraft are continuing to return data about interplanetary space and some of our stellar neighbors near the edges of the Milky Way.

As the Voyagers cruise gracefully in the solar wind, their fields, particles and waves instruments are studying the space around them. In May 1993, scientists concluded that the plasma wave experiment was picking up radio emissions that originate at the heliopause -- the outer edge of our solar system.

The heliopause is the outermost boundary of the solar wind, where the interstellar medium restricts the outward flow of the solar wind and confines it within a magnetic bubble called the heliosphere. The solar wind is made up of electrically charged atomic particles, composed primarily of ionized hydrogen, that stream outward from the Sun.

Exactly where the heliopause is has been one of the great unanswered questions in space physics. By studying the radio emissions, scientists now theorize the heliopause exists some 90 to 120 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. (One AU is equal to 150 million kilometers (93 million miles), or the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

The Voyagers have also become space-based ultraviolet observatories and their unique location in the universe gives astronomers the best vantage point they have ever had for looking at celestial objects that emit ultraviolet radiation.

The Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) is the only experiment on the scan platform that is still functioning. The scan platform is parked at a fixed position and is not being articulated. The Infrared Spectrometer and Radiometer (IRIS) heater was turned off to save power on Voyager 1 on December 7, 2011. On January 21, 2014 the Scan Platform Supplemental Heater was also turned off to conserve power. The IRIS heater and the Scan Platform Heater were used to keep UVS warm. The UVS temperature has dropped to below the measurement limits of the sensor; however, UVS is still operating. The scientist expect to continue to receive data from the UVS until 2016, at which time the instrument will be turned off to save power.

Yet there are several other fields and particle instruments that can continue to send back data as long as the spacecraft stay alive. They include: the cosmic ray subsystem, the low-energy charge particle instrument, the magnetometer, the plasma subsystem, the plasma wave subsystem and the planetary radio astronomy instrument. Barring any catastrophic events, JPL should be able to retrieve this information for at least the next 20 and perhaps even the next 30 years.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have reached "Interstellar space" and each continue their unique journey through the Universe. In the NASA Eyes on the Solar System app, you can see the real spacecraft trajectories of the Voyagers, which are updated every five minutes. Distance and velocities are updated in real-time.

Mission Overview. The twin Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are exploring where nothing from Earth has flown before. Continuing on their more-than-40-year journey since their 1977 launches, they each are much farther away from Earth and the sun than Pluto. In August 2012, Voyager 1 made the historic entry into interstellar space, the region between ...