- Latest News

- Press Releases

Salmon Migration: Interactive Map Illustrates Fantastic Journey in Peril

- Jacqueline Koch

- Feb 22, 2021

Endangered Columbia River Basin Salmon Connect Communities Across Northwest, New Proposal Offers Opportunity to Recover Them

SEATTLE — The release of a media-rich, interactive storymap, Salmon Migration: A journey that connects us all , highlights the iconic wildlife event that brings together diverse Northwest communities, from the Pacific Coast to central Idaho. Columbia River Basin salmon and steelhead are essential for Northwest tribes, local economies, and the region’s way of life — yet they’re running out of time. The Salmon Migration storymap is a timely addition to a national conversation ignited by U.S. Representative Mike Simpson’s (R-Idaho) recent proposal for the Columbia Basin Fund, a jobs and infrastructure framework that offers a strong starting point to save the Northwest’s valuable fisheries and river-dependent communities by restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River.

“The endangered salmon of the Columbia and Snake Rivers sustain a fragile ecosystem, diverse communities and the Northwest’s economic prosperity. The Columbia Basin Fund is a bold step in the right direction, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to launch the greatest river restoration and salmon recovery effort in history,” said Sarah Bates, acting regional executive director for the National Wildlife Federation’s Northern Rockies, Prairies, and Pacific Region.

Traveling across the region, the Salmon Migration storymap weaves together personal stories and insights from communities and generations connected by the Columbia River, from teenage conservationists in Boise, ID, to seasoned commercial fishermen on the Pacific coast. The storymap takes viewers on a journey of discovery and prompts an important question for us all: Can we transform the interconnected challenges of energy, agriculture and salmon into a stronger, more resilient Northwest?

“If we follow the migration of these magnificent fish, we can fully understand why the Northwest needs a comprehensive solution that restores salmon. Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson answered our calls with a blueprint for the largest river and salmon restoration effort in history that also creates jobs and strengthens the energy and agriculture sectors,” said Chris Hager, executive director of Association of Northwest Steelheaders. "We applaud his dedication and look to our regional delegates to engage with Simpson’s proposal to bring urgent innovative solutions to this issue.”

The Salmon Migration storymap is a guide to understanding the many ways Northwest salmon runs have shaped our lives, communities and the region. The Columbia River Basin framework and recent media reports highlight the interconnected challenges—and opportunities—of a region-wide salmon recovery effort:

- Read Rep. Simpson’s Columbia Basin Fund framework

- What would the Columbia Basin Fund do? Watch the video

- A Seattle Times feature by Lynda Mapes outlines a new vision for the Northwest: GOP congressman pitches $34 billion plan to breach Lower Snake River dams in new vision for Northwest

- A New York Times article highlights the urgent need to address warming water temperatures in the Columbia River Basin: How long before these salmon are gone? Maybe 20 years.

- The Seattle Times outlines our best opportunity to make good on treaty obligations and promises to Northwest tribes: Salmon People: A tribe’s decades-long fight to take down the Lower Snake River dams and restore a way of life

View the interactive Salmon Migration story map here to learn more about the salmon that are the lifeforce of the Columbia and Snake River systems.

Read the National Wildlife Federation’s statement on the release of the Rep. Simpson’s Columbia Basin Fund here .

Get Involved

Donate Today

Sign a Petition

Donate Monthly

Nearby Events

Sign Up for Updates

What's Trending

Take the Pledge

Encourage your mayor to take the Mayors' Monarch Pledge and support monarch conservation before April 30!

UNNATURAL DISASTERS

A new storymap connects the dots between extreme weather and climate change and illustrates the harm these disasters inflict on communities and wildlife.

Come Clean for Earth

Take the Clean Earth Challenge and help make the planet a happier, healthier place.

Creating Safe Spaces

Promoting more-inclusive outdoor experiences for all

Where We Work

More than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We're on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.

- ACTION FUND

PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583

800.822.9919

Join Ranger Rick

Inspire a lifelong connection with wildlife and wild places through our children's publications, products, and activities

- Terms & Disclosures

- Privacy Policy

- Community Commitment

National Wildlife Federation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization

You are now leaving nwf.org

In 4 seconds , you'll be redirected to our Action Center at www.nwfactionfund.org.

Animal encyclopedia

Understanding chinook salmon: a comprehensive guide.

Updated on: September 14, 2023

John Brooks

September 14, 2023 / Reading time: 5 minutes

Sophie Hodgson

We adhere to editorial integrity are independent and thus not for sale. The article may contain references to products of our partners. Here's an explanation of how we make money .

Why you can trust us

Wild Explained was founded in 2021 and has a long track record of helping people make smart decisions. We have built this reputation for many years by helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions. We have helped thousands of readers find answers.

Wild Explained follows an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can assume that your interests are our top priority. Our editorial team is composed of qualified professional editors and our articles are edited by subject matter experts who verify that our publications, are objective, independent and trustworthy.

Our content deals with topics that are particularly relevant to you as a recipient - we are always on the lookout for the best comparisons, tips and advice for you.

Editorial integrity

Wild Explained operates according to an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can be sure that your interests are our top priority. The authors of Wild Explained research independent content to help you with everyday problems and make purchasing decisions easier.

Our principles

Your trust is important to us. That is why we work independently. We want to provide our readers with objective information that keeps them fully informed. Therefore, we have set editorial standards based on our experience to ensure our desired quality. Editorial content is vetted by our journalists and editors to ensure our independence. We draw a clear line between our advertisers and editorial staff. Therefore, our specialist editorial team does not receive any direct remuneration from advertisers on our pages.

Editorial independence

You as a reader are the focus of our editorial work. The best advice for you - that is our greatest goal. We want to help you solve everyday problems and make the right decisions. To ensure that our editorial standards are not influenced by advertisers, we have established clear rules. Our authors do not receive any direct remuneration from the advertisers on our pages. You can therefore rely on the independence of our editorial team.

How we earn money

How can we earn money and stay independent, you ask? We'll show you. Our editors and experts have years of experience in researching and writing reader-oriented content. Our primary goal is to provide you, our reader, with added value and to assist you with your everyday questions and purchasing decisions. You are wondering how we make money and stay independent. We have the answers. Our experts, journalists and editors have been helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions for over many years. We constantly strive to provide our readers and consumers with the expert advice and tools they need to succeed throughout their life journey.

Wild Explained follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that our content is honest and independent. Our editors, journalists and reporters create independent and accurate content to help you make the right decisions. The content created by our editorial team is therefore objective, factual and not influenced by our advertisers.

We make it transparent how we can offer you high-quality content, competitive prices and useful tools by explaining how each comparison came about. This gives you the best possible assessment of the criteria used to compile the comparisons and what to look out for when reading them. Our comparisons are created independently of paid advertising.

Wild Explained is an independent, advertising-financed publisher and comparison service. We compare different products with each other based on various independent criteria.

If you click on one of these products and then buy something, for example, we may receive a commission from the respective provider. However, this does not make the product more expensive for you. We also do not receive any personal data from you, as we do not track you at all via cookies. The commission allows us to continue to offer our platform free of charge without having to compromise our independence.

Whether we get money or not has no influence on the order of the products in our comparisons, because we want to offer you the best possible content. Independent and always up to date. Although we strive to provide a wide range of offers, sometimes our products do not contain all information about all products or services available on the market. However, we do our best to improve our content for you every day.

Table of Contents

Chinook salmon, also known as king salmon, are fascinating creatures that play a crucial role in the environment. In this comprehensive guide, we will take an in-depth look at these remarkable fish, from their unique characteristics to their role in the ecosystem. We will also explore the life cycle of Chinook salmon, the threats they face, and the conservation efforts aimed at preserving their populations.

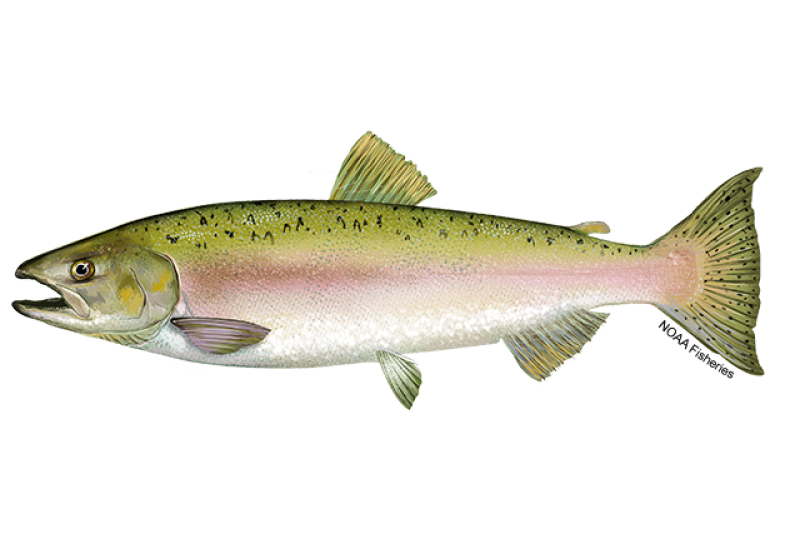

Introduction to Chinook Salmon

As the largest species of Pacific salmon, Chinook salmon are highly prized among anglers and seafood lovers. These majestic fish are known for their silvery bodies, which are often adorned with spots and a pinkish hue. The average adult Chinook salmon can grow anywhere from 24 to 36 inches in length and weigh between 10 and 50 pounds.

Chinook salmon are native to the Pacific Northwest, particularly the coastal regions of North America. They are anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean for most of their lives, and return to their natal streams to spawn. This unique life cycle is essential to the survival of the species and contributes to the overall health and productivity of the ecosystem.

The Unique Characteristics of Chinook Salmon

One of the distinguishing features of Chinook salmon is their powerful and streamlined bodies , which enable them to undertake long and arduous migrations. They are also known for their sharp teeth and strong jaws , allowing them to feed on a diverse diet that includes smaller fish, crustaceans, and insects.

The Habitat of Chinook Salmon

Chinook salmon primarily reside in the cold, clear, and highly oxygenated waters of rivers and streams during their freshwater stages. They require well-oxygenated water with suitable gravelly substrate for spawning. These fish are highly adaptable and can be found in a range of habitats, from small tributaries to large rivers.

The Life Cycle of Chinook Salmon

The life cycle of Chinook salmon is nothing short of remarkable, consisting of several distinct stages. Understanding these stages is crucial for appreciating the complexity of their journey and the challenges they face throughout their lives.

Spawning and Early Life

Chinook salmon begin their lives as eggs laid in gravel nests called redds. Female salmon use their tails to dig these redds in suitable areas of gravel, where they deposit their eggs. After hatching, the young salmon, called fry, spend their early months in freshwater streams, feeding on insects and gaining strength.

As the fry grow, they undergo several physical changes and develop into parr, characterized by their distinct vertical stripes. During this stage, they continue to feed on insects and small aquatic organisms, using their keen senses to locate food and avoid predators.

Migration and Maturation

At a certain point in their development, the parr undergo physiological changes that prepare them for their migration to the ocean. Known as smolting, this process involves the salmon adapting to saltwater environments. The smolts change in coloration, acquire scales, and develop the ability to excrete excess salt through specialized salt glands.

Once they are fully smolted, the Chinook salmon begin their migration to the ocean. This incredible journey can span hundreds or even thousands of miles, as the fish navigate through rivers, estuaries , and the open sea. Along the way, they face numerous predators, such as birds and larger fish, which further highlight their resilience and adaptability.

Return to Freshwater and Reproduction

After spending several years in the ocean, adult Chinook salmon begin their return journey to their natal streams. They navigate upstream, overcoming challenging obstacles such as waterfalls and rapids, fueled by their instinctual drive to reproduce. The journey can be physically taxing, as the fish endure fasting and the energy-consuming process of swimming against strong currents.

Upon reaching their spawning grounds, the males and females engage in an elaborate courtship display . The females deposit their eggs in redds, while the males release their milt to fertilize them. After the reproductive process is complete, the adult salmon often succumb to exhaustion and die, leaving behind a new generation of fry to continue the cycle.

The Role of Chinook Salmon in the Ecosystem

As a keystone species, Chinook salmon have a profound impact on the ecosystem in which they reside. They are a vital source of food for a wide range of predators, including bears, eagles, and other fish species. The nutrients from their decomposed bodies also contribute to the health and fertility of surrounding landscapes.

Impact on Other Species

Chinook salmon play a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of marine and freshwater ecosystems. Their presence supports the abundance of other fish populations, including endangered species such as Southern Resident killer whales . The decline of Chinook salmon populations can have cascading effects throughout the food web, affecting numerous species and the overall stability of the ecosystem.

Threats to Chinook Salmon Populations

Despite their resilience, Chinook salmon face numerous threats that jeopardize their survival. Understanding these threats is crucial for implementing effective conservation measures and ensuring the persistence of these iconic fish.

Climate Change and Its Effects

Climate change poses a significant threat to Chinook salmon populations. Rising water temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and altered stream flows can impact their ability to spawn and successfully complete their life cycle. Additionally, ocean acidification, caused by increased carbon dioxide levels, can affect the availability of prey and disrupt the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Overfishing and Its Consequences

Overfishing has also had a detrimental impact on Chinook salmon populations. The demand for their prized flesh and the accidental capture of juveniles during fishing activities have depleted their numbers in many areas. Responsible fishing practices and the establishment of protected areas are essential for allowing salmon populations to recover and thrive.

Conservation Efforts for Chinook Salmon

In recent years, conservation efforts have been implemented to protect and restore Chinook salmon populations. These initiatives involve a combination of legislation, regulations, and restoration programs aimed at safeguarding the future of these vital fish.

Regulations and Restrictions

Through strict fishing regulations, authorities aim to control the harvest of Chinook salmon and reduce the impact on their populations. These measures include limits on fishing seasons, catch size, and gear types. By implementing these regulations, authorities can ensure sustainable fishing practices that allow for the recovery and preservation of Chinook salmon populations.

Restoration and Recovery Programs

Restoration and recovery programs play a significant role in revitalizing Chinook salmon populations. These initiatives involve habitat restoration, such as removing barriers to migration, improving water quality, and enhancing spawning grounds. Additionally, captive breeding and salmon supplementation programs aim to bolster populations by releasing young salmon into the wild.

In conclusion, understanding Chinook salmon is essential for appreciating their importance in the ecosystem and the challenges they face. From their unique characteristics to their remarkable life cycle, these fish embody resilience and adaptation. By addressing the threats they encounter and implementing effective conservation measures, we can ensure the survival of Chinook salmon, preserving their role as a keystone species and safeguarding the health and vitality of our oceans and rivers.

Related articles

- Fresh Food for Cats – The 15 best products compared

- The Adorable Zuchon: A Guide to This Cute Hybrid Dog

- Exploring the Unique Characteristics of the Zorse

- Meet the Zonkey: A Unique Hybrid Animal

- Uncovering the Secrets of the Zokor: A Comprehensive Overview

- Understanding the Zebu: An Overview of the Ancient Cattle Breed

- Uncovering the Fascinating World of Zebrafish

- Watch Out! The Zebra Spitting Cobra is Here

- The Fascinating Zebra Tarantula: A Guide to Care and Maintenance

- The Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker: A Closer Look

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Zebra Snake

- The Amazing Zebra Pleco: All You Need to Know

- Discovering the Fascinating Zebra Shark

- Understanding the Impact of Zebra Mussels on Freshwater Ecosystems

- Caring for Your Zebra Finch: A Comprehensive Guide

- The Fascinating World of Zebras

- The Adorable Yorkshire Terrier: A Guide to Owning This Lovable Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Poo: A Guide to This Popular Dog Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Bichon: A Perfect Pet for Any Home

- The Adorable Yoranian: A Guide to This Sweet Breed

- Discover the Deliciousness of Yokohama Chicken

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Yeti Crab

- Catching Yellowtail Snapper: A Guide to the Best Fishing Spots

- The Brightly Colored Yellowthroat: A Guide to Identification

- Identifying and Dealing with Yellowjacket Yellow Jackets

- The Yellowish Cuckoo Bumblebee: A Formerly Endangered Species

- The Yellowhammer: A Symbol of Alabama’s Pride

- The Benefits of Eating Yellowfin Tuna

- The Yellow-Faced Bee: An Overview

- The Majestic Yellow-Eyed Penguin

- The Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake: A Fascinating Creature

- The Benefits of Keeping a Yellow Tang in Your Saltwater Aquarium

- The Beautiful Black and Yellow Tanager: A Closer Look at the Yellow Tanager

- The Fascinating Yellow Spotted Lizard

- What You Need to Know About the Yellow Sac Spider

- Catching Yellow Perch: Tips for a Successful Fishing Trip

- The Growing Problem of Yellow Crazy Ants

- The Rare and Beautiful Yellow Cobra

- The Yellow Bullhead Catfish: An Overview

- Caring for a Yellow Belly Ball Python

- The Impact of Yellow Aphids on Agriculture

- Catching Yellow Bass: Tips and Techniques for Success

- The Striking Beauty of the Yellow Anaconda

- Understanding the Yarara: A Guide to This Unique Reptile

- The Yakutian Laika: An Overview of the Ancient Arctic Dog Breed

- The Fascinating World of Yaks: An Introduction

- Everything You Need to Know About Yabbies

- The Xoloitzcuintli: A Unique Breed of Dog

- Uncovering the Mystery of Xiongguanlong: A Newly Discovered Dinosaur Species

- Uncovering the Mysteries of the Xiphactinus Fish

- Camp Kitchen

- Camping Bags

- Camping Coolers

- Camping Tents

- Chair Rockers

- Emergency Sets

- Flashlights & Lanterns

- Grills & Picnic

- Insect Control

- Outdoor Electrical

- Sleeping Bags & Air Beds

- Wagons & Carts

- Beds and furniture

- Bowls and feeders

- Cleaning and repellents

- Collars, harnesses and leashes

- Crates, gates and containment

- Dental care and wellness

- Flea and tick

- Food and treats

- Grooming supplies

- Health and wellness

- Litter and waste disposal

- Toys for cats

- Vitamins and supplements

- Dog apparel

- Dog beds and pads

- Dog collars and leashes

- Dog harnesses

- Dog life jackets

- Dog travel gear

- Small dog gear

- Winter dog gear

© Copyright 2024 | Imprint | Privacy Policy | About us | How we work | Editors | Advertising opportunities

Certain content displayed on this website originates from Amazon. This content is provided "as is" and may be changed or removed at any time. The publisher receives affiliate commissions from Amazon on eligible purchases.

Chinook salmon

Wild Chinook salmon are found all along the west coast of North America, from Monterey Bay in California to the Chukchi Sea in Alaska. Like all salmon species, Chinook are anadromous—that is, they are born in fresh water, migrate to the ocean, then return as mature adults to lay their eggs in the streams where they were born.

The life of a Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon begin their lives as eggs laid by an adult female in a cold, clean, sheltered stream. The eggs hatch in spring. The tiny fish grow larger as they spend about five months in the stream, eating insects and crustaceans.

When they're big enough, they begin their migration to the ocean. They often spend awhile eating heavily in the half-salt and half-fresh water of an estuary to get even bigger. Once they reach the ocean, they spend up to 8 years there, eating fish. An adult Chinook salmon living in the ocean is the largest of all the Pacific salmon species. It often weighs more than 100 pounds and grows up to 5 feet long.

After several years, Chinook journey back to their home stream to "spawn," or lay their eggs. Their sense of smell leads them home. Biologists believe a spawning salmon can smell its home stream in water that has only 1-2 parts of the stream's chemical signature per million. It's like being able to sniff out a single drop of water in 250 gallons!

Once they arrive in the home stream, the female builds a "redd," or nest. She releases her eggs into the redd, and the male fertilizes it. She covers the eggs with loose gravel and they both swim further upstream to do the process all over again. All the while, their bodies are breaking down, and eventually they both die.

Each year, at approximately the same time of year, a number of adult Chinook salmon return to their natal streams to spawn. In our area, they spawn in the Columbia River and its larger tributaries in the fall, "running" in specific areas of the river. The Chinook that come to the lower end of the Columbia are called "Tules." The upriver Chinook are called "Upriver Brights." You can see Chinook from each group in the zoo's Eagle Canyon exhibit.

Living salmon are food for many kinds of wildlife, from bald eagles to killer whales to grizzly bears. After they die, their bodies provide vital food and nutrients to the plants and animals in the stream ecosystem.

Chinook salmon conservation

Salmon need cold, clean water to survive. They struggle with pollution, warming waters and habitat deterioration. Dams block their travel to and from the ocean. Metro is working to protect and restore habitat for salmon and other wildlife in the Portland metropolitan area.

How you can help Chinook salmon

You can help Chinook and other salmon species by conserving water. This leaves more water in the local waterways, and helps preserve stream and river ecosystems.

Chinook salmon at the Oregon Zoo

The zoo's Chinook salmon live in the Eagle Canyon exhibit. They are fed a mixture of krill, brine shrimp, chopped fish and insects.

Join us @OregonZoo

- facebook Facebook

- twitter Twitter

- instagram Instagram

- youtube Youtube

- tiktok TikTok

More Animals

Oregon spotted frog, california condor.

Cephalopods, Crustaceans & Other Shellfish

Corals & Other Invertebrates

Marine Mammals

Marine Science & Ecosystems

Ocean Fishes

Sea Turtles & Reptiles

Sharks & Rays

Marine Life Encyclopedia

Chinook Salmon

Oncorhynchus Tshawytscha

Distribution

Temperate to sub-polar latitudes of the north Pacific Ocean

eCOSYSTEM/HABITAT

Rivers and coastal seas

FEEDING HABITS

Active predator

Order Salmoniformes (salmons and relatives), Family Salmonidae (trouts and salmons)

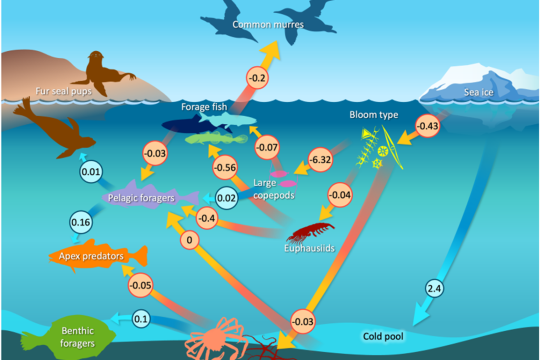

Adult Chinook salmon live in coastal seas and feed on pelagic invertebrates and other fishes. During the oceanic portion of their life cycle, these fish are primarily concerned with growing and storing energy that they will require for successful reproduction. This period can last anywhere between one and eight years. Once they reach reproductive size, they begin a long migration to their preferred spawning ground, fair inland, in freshwater rivers. In some rivers, the preferred spawning areas can be as far as 1900 miles (3000 km) upriver and at elevations of 5000 feet (1500 m) above sea level. Interestingly, though they mix into large populations at sea, each individual Chinook salmon returns to spawn in the river where it hatched. Thousands of individuals migrate to and reach the spawning grounds at the same time. Once they arrive, females dig nests in light gravel and lay their eggs on the river bottom. Males fertilize the eggs externally, and then the females bury the nests. Chinook salmon do not feed during the long trip to spawn, and the difficult task of swimming upriver, jumping up rapids and waterfalls, and digging nests is too much to survive. As soon as they spawn, individuals of this species die. After they hatch, baby Chinook salmon slowly make their way to the ocean, where they feed until they reach maturity and begin the cycle again.

Chinook salmon are important oceanic prey for species such as the steller sea lion and the killer whale . They are also an extremely important source of nutrients and food for species that live near their spawning grounds (where they all die). Those species include bears, predatory and scavenging birds, wolves, and countless other species. In fact, even trees growing along north Pacific rivers likely rely on dead Chinook salmon and other salmons for vital nutrients required for growth. The Chinook salmon is also an important fishery species. In the ocean, large boats target this species in very large numbers. While they migrate toward their spawning grounds, Chinook salmon are targeted by smaller-scale operations of fishers – many from native peoples that have relied on Chinook salmon runs for thousands of years. Unfortunately, overfishing, climate change, and damming of large, coastal rivers all threaten Chinook salmon, and several populations are critically endangered (very highly vulnerable to extinction) or even extinct. Dams that prevent this species from reaching its preferred spawning grounds are probably the most detrimental human impact on Chinook salmon populations.

Though they are native only to the north Pacific Ocean, Chinook salmon have been established, purposefully or accidentally, in several other places in the world – including New Zealand, Chile, and other places. Many of the established populations are a result of escapement from aquaculture facilities. The Chinook salmon is one of the most heavily aquacultured marine species and is the object of a very large market of farmed salmon.

Engage Youth with Sailors for the Sea

Oceana joined forces with Sailors for the Sea, an ocean conservation organization dedicated to educating and engaging the world’s boating community. Sailors for the Sea developed the KELP (Kids Environmental Lesson Plans) program to create the next generation of ocean stewards. Click here or below to download hands-on marine science activities for kids.

Additional Resources:

NOAA Fisheries

Get Involved

Donate Today

Support our work to protect the oceans by giving today.

With the support of more than 1 million activists like you, we have already protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean.

TAKE ACTION NOW

Support policy change for the oceans.

Decision-makers need to hear from ocean lovers like you. Make your voice heard!

VISIT OUR ADOPTION CENTER

Symbolically adopt an animal today.

Visit our online store to see all the ocean animals you can symbolically adopt, either for yourself or as a gift for someone else.

DOWNLOAD OCEAN ACTIVITIES

Help kids discover our blue planet.

Our free KELP (Kids Environmental Lesson Plans) empower children to learn about and protect our oceans!

FEATURED CAMPAIGN

Save the oceans, feed the world.

We are restoring the world’s wild fish populations to serve as a sustainable source of protein for people.

More CAMPAIGNs

Protect Habitat

Oceana International Headquarters 1025 Connecticut Avenue, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 USA

General Inquiries +1(202)-833-3900 [email protected]

Donation Inquiries +1(202)-996-7174 [email protected]

Press Inquiries +1(202)-833-3900 [email protected]

Oceana's Efficiency

Become a Wavemaker

Sign up today to get weekly updates and action alerts from Oceana.

SHOW YOUR SUPPORT WITH A DONATION

We have already protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean and innumerable sea life - but there is still more to be done.

QUICK LINKS:

Press Oceana Store Marine Life Blog Careers Financials Privacy Policy Revisit Consent Terms of Use Contact

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Digg

Latest Earthquakes | Chat Share Social Media

How far do salmon travel?

Salmon first travel from their home stream to the ocean, which can be a distance of hundreds of miles. Once they reach the ocean, they might travel an additional 1,000 miles to reach their feeding grounds.

Learn more: Western Fisheries Research Center - Questions and Answers about Salmon

Related Content

- Publications

Are salmon endangered worldwide?

No, salmon are not endangered worldwide. For example, most populations in Alaska are healthy. Some populations in the Pacific Northwest are much healthier than others. These healthy populations usually occupy protected habitats such as the Hanford Reach on the Columbia River and streams of Olympic National Park. Learn more: Western Fisheries Research Center - Questions and Answers about Salmon

How long do salmon usually live?

Most salmon species live 2 to 7 years (4 to 5 average). Steelhead trout can live up to about 11 years. Learn more: Western Fisheries Research Center - Questions and Answers about Salmon

How do salmon know where their home is when they return from the ocean?

Salmon come back to the stream where they were 'born' because they 'know' it is a good place to spawn; they won't waste time looking for a stream with good habitat and other salmon. Scientists believe that salmon navigate by using the earth’s magnetic field like a compass. When they find the river they came from, they start using smell to find their way back to their home stream. They build their...

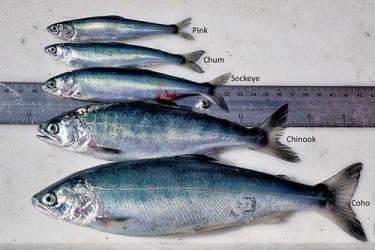

How many species of salmon are there and how large can they get?

There are seven species of Pacific salmon. Five of them occur in North American waters: chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, and pink. Masu and amago salmon occur only in Asia. There is one species of Atlantic salmon. Chinook/King salmon are the largest salmon and get up to 58 inches (1.5 meters) long and 126 pounds (57.2 kg). Pink salmon are the smallest at up to 30 inches (0.8 meters) long and 12...

When can salmon be seen migrating to their spawning area?

Most Pacific salmon can be seen migrating from spring though fall, depending on the species. Most adult Atlantic salmon migrate up the rivers of New England beginning in spring and continuing through the fall as well, with the migration peaking in June. Learn more: Western Fisheries Research Center - Questions and Answers about Salmon

Where are salmon most endangered?

Certain populations of sockeye salmon, coho salmon, chinook salmon, and Atlantic salmon are listed as endangered. Sockeye salmon from the Snake River system are probably the most endangered salmon. Coho salmon in the lower Columbia River may already be extinct. Salmon are not endangered worldwide. For example, most populations in Alaska are healthy. Some populations in the Pacific Northwest are...

Why are there so few salmon left?

There are many reasons for the decline in salmon populations. Logging an area around a stream reduces the shade and nutrients available to the stream and increases the amount of silt or dirt in the water, which can choke out developing eggs. Dams cause fish to die from the shock of going through the turbines and from predators that eat the disoriented fish as they emerge from the dam. Overfishing...

Why do salmon change color and die after they spawn?

Salmon change color to attract a spawning mate. Pacific salmon use all their energy for returning to their home stream, for making eggs, and digging the nest. Most of them stop eating when they return to freshwater and have no energy left for a return trip to the ocean after spawning. After they die, other animals eat them (but people don't) or they decompose, adding nutrients to the stream...

Why do salmon eggs come in different colors?

Salmon eggs (roe) range in color from pale yellowish-orange to dark reddish-orange. The color varies both by species and within species and is determined by water temperature, sediment composition, age, and other factors. The eggs vary in size from the tiny sockeye roe (average ¼ inch or 5.6 mm) to the large chum roe (average almost ½ inch or 8.3 mm). Also, if a salmon egg does not get fertilized...

Where can I find fish consumption advisories for my state?

Most states have set fish (and wildlife) consumption advisories and recommended consumption levels. The state agency responsible for these limits varies. Examples of consumption advisory information can be found at the Environmental Protection Agency's Fish and Shellfish Advisories and Safe Eating Guidelines website.

PubTalk 2/2015 — Undamming Washington's Elwha River

by Amy East USGS Research Geologist

- Hear about river response to the largest dam removal in history.

- Causing disturbance as a means of restoration: how well does it work?

- Will legendary salmon runs return?

A Time to Spawn

Salmon and steelhead migrating through Bonnerville Dam.

Developing fluvial fish species distribution models across the conterminous United States—A framework for management and conservation

By land, air, and water — u.s. geological survey science supporting fish and wildlife migrations throughout north america, juvenile salmonid monitoring in the white salmon river, washington, post-condit dam removal, 2016, behavior and movements of adult spring chinook salmon ( oncorhynchus tshawytscha ) in the chehalis river basin, southwestern washington, 2015, passage and survival probabilities of juvenile chinook salmon at cougar dam, oregon, 2012, behavior and movement of adult summer steelhead following collection and release, lower cowlitz river, washington, 2012--2013, survival and migration route probabilities of juvenile chinook salmon in the sacramento-san joaquin river delta during the winter of 2009-10, summary of migration and survival data from radio-tagged juvenile coho salmon in the trinity river, northern california, 2008, behavior and movement of adult chum salmon in the lower cowlitz river, 2007: final report of research, community flood protection may also help endangered salmon to thrive.

Building a river setback levee to reduce the risk of flood for a community may also help endangered fish species to thrive, according to the results...

Endangered Salmon Population Monitored with eDNA for First Time

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

- Chinook Salmon

Updated June 2021 based on data available through December 2017.

Declining Trend

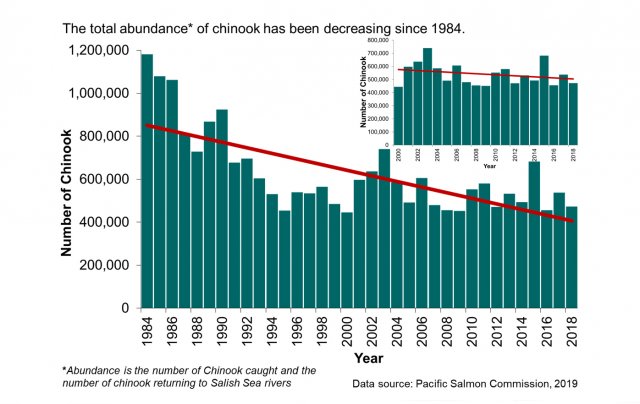

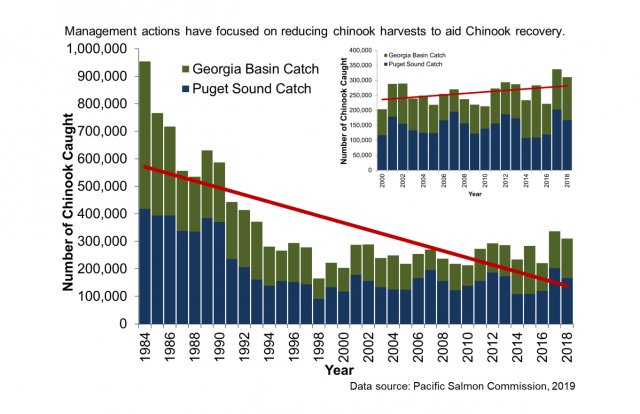

Salish Sea Chinook salmon populations are down 60% since the Pacific Salmon Commission began tracking salmon abundance in 1984.

Between 2000 and 2018, the total number of Chinook returning to the Salish Sea has shown a relatively stable trend. However, during this time period, we also see a modest increase in catch and a modest decrease in fish returning to spawn, particularly over the last few reporting years.

About Chinook Salmon

What's happening, why is it important, why is it happening, what's being done about it, five things you can do to help.

Salmon are an iconic species of the Salish Sea. They play a critical role in supporting and maintaining ecological health, and in the social fabric of First Nations and tribal culture.

Strong commercial and recreational salmon fisheries also make salmon an important economic engine for the region.

Chinook ( Onchorhychus tshawytscha ) are the largest salmon, and are commonly known as "Kings" or "Tyee" (which means "chief" in Chinook jargon).

Ecology and Life History

The Salish Sea is home to nine different species of salmon and trout:

- Chinook salmon ( Oncorhynchus tshawytscha ).

- Coho salmon (also called silver salmon; Oncorhynchus kisutch ).

- Chum salmon (also called dog salmon; Oncorhynchus keta ).

- Sockeye salmon (also called red salmon; Oncorhynchus nerka ).

- Pink salmon (also called humpback salmon; Oncorhynchus gorbuscha ).

- Steelhead trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ).

- Cutthroat trout ( Oncorhynchus clarkii ).

- Bull trout ( Salvelinus confluentus ).

- Dolly Varden trout ( Salvelinus malma ).

Chinook are a particularly important species in the Salish Sea ecosystem because of both their economic and ecological value.

Chinook salmon are born in fresh water, spend much of their life at sea, and then return to fresh water to spawn (this is called anadromous). They die after spawning once (this is called semelparous). Chinook vary from other salmonids in their age at seaward migration, length of residence in freshwater, estuaries and the ocean, distribution and migration in the ocean, and the age, season and length of migration for spawning.

Distinguished by small black spots on both lobes of their tail fin, and black gums in their lower jaw, they are the largest of the salmonids in size – averaging 15 pounds in commercial marine fisheries, 30 pounds in sport marine fisheries and reaching over 75 pounds on the spawning grounds of some populations. Chinook salmon have the longest migration routes from early emergence from their spawning redds (spawning nests) in higher elevation streams and rivers, down long river corridors and then out into the Pacific gyre for years only to return thousands of miles up their same natal rivers to their original spawning areas.

Sustainable Perspectives

First foods ceremonies are one way Coast Salish communities celebrate respect for the earth. In spring, families celebrate the first Chinook salmon caught with First Salmon ceremonies called Thehitem ("looking after the fish.") At the end of the ceremonies the bones of the salmon are returned to the river with a prayer giving thanks to the Creator, Chíchelh Siyá:m, and the salmon people. This is to show that the salmon were well-treated and welcome the following year.

Traditional Names for Chinook Salmon

- Blackmouth (USA)

- K'with'thet (Salish)

- K'wolexw (Salish)

- King salmon (USA, Canada)

- Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Latin)

- Sa aeup (Nuuchahnulth)

- Sa-cin (Nuuchahnulth)

- Schaanexw (Salish)

- Shamet skelex (Salish)

- Shmexwalsh (Salish)

- Sinaech (Salish)

- Sk'wel'eng's schaanexw (Salish)

- Slhop' schaanexw (Salish)

- Spak'ws schaanexw (Salish)

- Spring salmon (USA, Canada, Australia)

- St'thokwi (Salish)

- Su-ha (Nuuchahnulth)

- Tyee salmon (Canada, USA)

Just over 473,000 adult Chinook salmon were estimated by the Pacific Salmon Commission to have passed through the Salish Sea in 2018 (see charts below). This is a 60% reduction in Chinook salmon abundance since the Commission began tracking salmon data in 1984. The current estimate does not include the effect of predators or other sources of Chinook mortality before spawning, so it may overestimate the spawning population size.

Between 2000 and 2018, the total number of Chinook returning to the Salish Sea has shown a relatively stable trend. During this time period, the technical reports also show a small increase in catch and a small decrease in returning spawners, particularly over the last few reporting years.

There has been inter-annual variability in population size since tracking Chinook populations began. Currently for most stocks of Salish Sea Chinook salmon that are monitored by the Pacific Salmon Commission, about the same number of fish return each year to spawn. A few individual stocks have shown recent changes in spawning fish returns, with some stocks showing increases in returning spawner numbers while other stocks have decreasing numbers of returning fish. Research completed in 2018 has suggested that the average age and size of returning Chinook salmon is changing too, with fish maturing and spawning at younger ages. The largest-sized Chinook salmon are less common now compared to 40 years ago.

Taken together, all the monitoring data suggest that no improvement in the overall trend of Chinook salmon abundance has happened since 1999, when Puget Sound Chinook salmon were listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Puget Sound Chinook salmon have not improved according to the 2020 Puget Sound Vital Signs indicator chart for Chinook salmon .

Puget Sound was once home to larger populations of Chinook and other salmon, with a greater diversity of traits than populations existing today. Only 22 of at least 37 historic Chinook salmon populations remain in this ecosystem. The remaining Chinook salmon populations are at as little as 10% of their historic numbers. The decline in salmon is closely associated with harvest rates, decline in the overall health of the Salish Sea and its contributing watersheds, habitat loss, and/or the lowered resilience of these ecosystems to climate change.

The importance of salmon to coastal First Nations and tribes is evident in every coastal archaeological dig in the Salish Sea ecosystem, dating back thousands of years. Salmon have long been a constant and reliable part of the Coast Salish diet and cultural heritage. Reports suggest that harvest rates by the tribes were not enough to depress salmon populations, but rather, that their fishing practices amplified salmon abundance.

Salmon provide food and support broader food-webs for a variety of wildlife, from bald eagles to killer whales to bears, and are a culturally invaluable food source for Puget Sound Tribes, First Nations, and our community as a whole. Chinook salmon in particular are the primary food source of the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKWs). Because salmon die after spawning, their carcasses also provide abundant food and nutrients to plants and animals, including tiny aquatic insects and other invertebrates that in turn provide food for other animals.

During their life cycle, salmon transfer energy and nutrients between the Pacific Ocean and freshwater and land habitats. Since Chinook are the largest salmonid, they contribute the largest amount of biomass (organic matter) per fish to the ecosystem. In fact, in areas that have experienced dramatic declines in salmon, there is a measurable deficit of nutrients to help support the ecosystem.

Economic Impact

Commercial and recreational salmon fisheries in the U.S. state and Canadian province bordering the Salish Sea were worth an average of $1.1 billion annually (GDP) from 2012 to 2015. From 2012 to 2015, this value ranged from $12.6 to $31.5 million (see chart below).

Annual employment in commercial fishing industry is highly seasonal. In British Columbia (B.C.), full-time equivalent (FTE) employment related to commercial salmon fishing was estimated at 2,710 jobs in 2015. FTE employment related to recreational salmon fishing in B.C. was estimated at 6,480 jobs in the same year. In Washington State, FTE employment related to salmon fishing was 2,700 commercial fishing jobs and 3,540 recreational fishing jobs in 2015. The amount of FTE jobs supported by salmon fishing in the Salish Sea region has declined over time with declining salmon populations.

Both commercial and recreational salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea region are highly valued economically. In B.C., all salmon fisheries generated an average of $641 million annually in GDP from 2012 to 2015. In Washington State, all salmon fisheries generated an average of $477 million GDP annually during the same years.

The steep historical decline in Chinook salmon is associated with four main factors:

- Habitat loss and degradation.

- Harvest rates.

- Hatchery influence.

- Dams that impede migrations.

Additional factors increasingly recognized as contributing to declining salmon populations include climate change, ocean conditions, and marine mammal interactions.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Since Chinook salmon habitat spans such a large area - from freshwater to the open ocean - they are more likely to be impacted by changes in habitat that supports a key life cycle. Such changes have been particularly prominent in freshwater habitats as the condition of streams, rivers, lakes and wetlands have been lost or highly degraded through timber harvest, agricultural practices, urbanization, and stormwater pollution that has impacted both the quality and quantity of salmon habitats.

Harvest Rates

Between 1975 and 2018, almost 22 million Chinook were harvested for commercial, sport, or subsistence and ceremonial fisheries. It is difficult to estimate sustainable harvest limits. Harvest rates have remained relatively constant throughout the past decade and harvest rates are drastically lower now prior to the 1990s. This has caused hardship for U.S tribes and First Nations and caused decreased opportunities for both recreational and commercial fishing.

Hatchery Influence

One of the objectives of hatcheries is to preserve remaining depleted salmon populations by raising and then releasing extra Chinook salmon smolts into the wild. However, hatchery salmon can have negative impacts on wild salmon populations, including loss of natural population identity, diminished adaptability, and interference with natural salmon population recovery. Nevertheless, salmon are critical for the livelihoods and cultural identities of the many Coast Salish tribes, and over three quarters of salmon returning to the Puget Sound to spawn came from hatcheries. The increased production of Chinook salmon by hatcheries over the years has allowed the tribes and Southern Resident Killer Whales to continue using them as a food source and has prevented a more devastating population decline of the salmon overall.

Water Infrastructure Impeding Migrations

The control of streams and rivers using infrastructure like culverts, dams, or floodgates can impact all salmonid species, including Chinook populations. This is an issue throughout the Pacific Northwest, including the Salish Sea. Water infrastructure can result in migration passage barriers, water quality impairments, loss of habitat and hydrological changes. For example, in the lower Fraser River, use of floodgates can affect the complexity of upstream habitats and fish communities and the abundance of juvenile salmon populations. In the State of Washington, despite investing billions of dollars on various fish passage structures to direct fish migration around dams in Chinook-bearing rivers, Chinook salmon are still declining overall. Removing key dams in parts of Washington has been proposed as an option to restore Chinook salmon populations in some parts of Washington State.

Climate Change

Forecasted impacts from climate change on Chinook salmon include habitat changes, such as increased winter flooding, decreased summer and fall stream flows, and increased temperatures in streams and estuaries. Even small shifts in water temperature could alter the timing of migration, reduce growth, reduce availability of oxygen in the water, reduce availability of preferred food sources, and increase the susceptibility to toxins, parasites and disease.

Ocean Conditions

Salmon survival during their first few months at sea is linked to ocean conditions such as surface water temperature and salinity (saltiness), particularly in coastal and estuarine environments. Ocean conditions can also affect food supplies, numbers of predators, and migratory patterns for Chinook salmon. Each of these factors affects marine survival of Chinook and their ability to return to their streams to spawn.

Marine Mammal Interactions

Fewer Chinook salmon means that predators that eat salmon may be having a greater overall impact on the remaining populations of Chinook. California sea lions ( Zalophus californianus ), Pacific harbor seals ( Phoca vitulina ) and killer whales ( Orcinus orca ) are known to prey on Chinook in the Salish Sea. Since the mid-1970s, there has been an increase in the seasonal abundance of sea lions and in the year-round abundance of harbor seals. The number of Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKWs) has decreased and Chinook salmon are their preferred food source over other salmonid species. The loss of Chinook abundance is likely a factor in the decreased abundance of SRKWs.

U.S. Treaties signed in the 1850s granted tribes "the right of taking fish from all usual and accustomed grounds and stations… in common with all citizens." The 1974 Supreme Court ruling, known as the Boldt Decision, re-affirmed the tribes' treaty reserved fishing rights. Today, the tribes and Washington State co-manage salmon recovery and habitat protection. In Puget Sound, the Partnership works with the tribes to achieve our shared goals to recover salmon.

The 1985 Pacific Salmon Treaty helped bring a science-based approach to international salmon conservation and harvest sharing.

In 1999, Puget Sound Chinook were listed for protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA), along with several other evolutionarily significant units (ESU) of Pacific salmon. In 2000, the National Marine Fisheries Service issued the salmon ESA 4(d) Rule, establishing take prohibitions for the Puget Sound Chinook and 13 other geographically-based Evolutionary Significant Units (ESU’s) of Chinook.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) is the group responsible for determining the extinction risk of wildlife populations in Canada. It maintains a list of wildlife populations according to their biological vulnerability status. COSEWIC makes recommendations to the Canadian government for updating the official Species At Risk Act (SARA) legal list that provides protection for vulnerable populations.

In 2018, COSEWIC assessed Chinook salmon in southern British Columbia, which includes Salish Sea populations. Only 16 Chinook salmon populations with low or no influence from hatcheries were investigated at the time. COSEWIC will examine hatchery-supported populations in a separate investigation.

The results of the COSEWIC assessment found that only one Southern BC Chinook salmon designatable unit (which is a unit comparable to ESAs from the United States) had no risk of extinction. Two Chinook salmon designatable units (DUs) did not have enough data to assess properly. The remaining 13 Chinook salmon DUs were identified by COSEWIC as Endangered (8 DUs), Threatened (4 DUs) and Special Concern (1 DU). The Canadian process for listing these Southern BC Chinook salmon DUs on SARA is underway and engagement regarding the SARA legal listing process may begin by late 2020.

U.S.-Canada Collaboration

The 1985 Pacific Salmon Treaty set the long-term goals for the benefit of the salmon and the two countries. The Pacific Salmon Commission is the body formed by the governments of Canada and the United States to implement the Pacific Salmon Treaty and in 1999, the United States and Canada reached a comprehensive new agreement, which established two bilateral Restoration and Enhancement funds.

At a management scale, the Salish Sea Marine Survival Project is an example of a research project to improve our understanding about the weak survival rates of juvenile salmon. Managed by Long Live the Kings in Washington and the Pacific Salmon Foundation in British Columbia, the project brings together U.S. and Canadian experts from federal, state and provincial agencies, tribes and First Nations, and academic and nonprofit organizations. The project was started in 2012 to evaluate potential stressors on juvenile salmon survival and to help develop science-based solutions to guide improvements in salmon management. As of January 2019, over 90 studies were initiated by the project, with 25 published in peer-reviewed journals. A final synthesis report for the project is expected in 2020.

Actions in Canada

In 2005, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) released its Wild Salmon Policy to conserve wild salmon and their habitat. The policy aims to safeguard the genetic diversity of wild salmon populations, maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity, and manage fisheries for sustainable benefits.

In 2011, DFO launched a "license retirement" program to reduce harvests of Chinook salmon, including areas within the Canadian portion of the Salish Sea.

In 2019, DFO placed strict restrictions on Fraser River Chinook harvesting to allow more salmon to reach their spawning grounds. Commercial fishing was completely closed until the late summer season. Fishing for ceremonial purposes by First Nations and recreational fishing were allowed in only small amounts.

A natural landslide was discovered along the Fraser River in June 2019 that blocked the path of spawning Chinook and other salmon. A collaboration of DFO, the provincial government of British Columbia, and First Nations governments was formed quickly to plan and take immediate action to assist migrating salmon through the summer and fall of 2019. Work in the area is continuing in the winter of 2019-2020 to clear away fallen rock and improve the site for future migrating Chinook and other salmon species of the Fraser River.

Actions in the U.S.

In 2008, in agreement with NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service, the Puget Sound Partnership (PSP) was designated to serve as Washington State’s regional salmon recovery organization for Puget Sound salmon species, excluding Hood Canal summer chum salmon. The Partnership implements the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Plan to protect and restore habitat, raise public awareness, coordinate on habitat, hatchery, and harvest practices, and develop a monitoring and adaptive management strategy to help track and assess efforts to recover salmon in Puget Sound. The work is accomplished by working with the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council , which consists of local stakeholders and communities, tribes, businesses, and state and federal agencies. The PSP also co-manages the Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration Fund with the Washington State Resource and Conservation Office (RCO), which supports salmon habitat restoration and protection.

In 2009, additional funds were authorized to lessen the impacts of harvest reductions, support the coded wire tag program (for salmon identification), improve analytical models, and implement individual stock-based management fisheries. The National Marine Fisheries Service, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the many tribes in Washington State work together to manage salmon fisheries. In addition to co-managing salmon harvest rates and hatchery influence, these entities work together to restore salmon habitat and monitor wild stock recovery after restoration efforts.

Related Projects

The following links exit the site

- Puget Sound National Estuary Program (NEP) Atlas - An interactive map showing conservation and restoration projects throughout the Puget Sound Basin.

- Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program - Providing funding and technical assistance to organizations working to restore shoreline and nearshore habitats critical to salmon and other species in Puget Sound. The program was established to advance projects using the scientific foundation developed by the Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project.

- Washington Shoreline Master Program Guidelines - The state rules that guide local governments in writing, adopting, and implementing local Shoreline Management Programs . They translate the broad policies of the state Shoreline Management Act into standards for regulating shoreline uses.

- State highways cross streams and rivers in thousands of places in Washington State, which can impede fish migration. The Washington State Department of Transport (WSDOT) has worked for nearly three decades to improve fish passage and reconnect streams to help keep our waterways healthy. WSDOT Fish Barrier Correction is a priority. Visit WSDOT's fish passage page to view the latest Fish Passage Annual Report and video. Also see how tribes, salmon recovery effort coalitions and local volunteers help to identify these problem culverts: Trekking the Backroads Counting Culverts for Salmon .

- Floodplains By Design (FbD) - an ambitious public-private partnership led by the Washington Department of Ecology, the Nature Conservancy, and the Puget Sound Partnership. FbD works to accelerate integrated efforts to reduce flood risks and restore habitat along Washington's major river corridors. Its goal is to improve the resiliency of floodplains in order to protect local communities and the health of the environment.

- British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund is a joint program of the Canadian federal government and the province of BC in place until March 2024, that will provide over $142 million CAD as funding for protection and restoration work for wild fish stocks (including salmon) and support BC’s fish and seafood industry. A list of funded projects , focused on innovation, infrastructure, and science partnerships is posted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and includes: investing in research on climate change threats to Pacific salmonids; promoting environmental farm planning near salmon streams in the BC interior, and investigating infrastructure options for the Cowichan Lake – Cowichan River boundary to ensure river flows sustain salmon populations.

- The Watershed Watch Salmon Society is working to support the recovery of BC’s wild salmon in the lower Fraser River watershed. The organization has identified salmon habitat in BC potentially affected by flood control structures and is supporting a number of community projects to restore salmon habitat.

- Landowners and developers in BC can apply to certify their land as Salmon-Safe . The Fraser Basin Council and the Pacific Salmon Foundation launched the eco-certification program in 2011. The Fraser Basin Council has led the program since 2018. The certification recognizes and verifies when an urban or rural site uses practices that protect salmon habitat and support better water quality. The certification program is also available in the United States, as the Salmon-Safe certification was founded in Oregon but is now established all along the Pacific coast.

Learn more about some of the work our partners are doing to protect Chinook salmon and their habitat.

- Pacific Salmon Commission

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada - Salmonid Enhancement Program

- Pacific Fishery Management Council

- NOAA Fisheries Salmon and Steelhead

- Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

- Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife "SalmonScape" Mapping System

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs - Chinook Salmon

- Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration Fund

- Long Live the Kings

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Species At Risk Act and Pacific Salmon

- Canada’s Species at Risk public registry – Chinook salmon

- Washington Recreation and Conservation Office - Lead entities for salmon recovery

- Keep streams shaded. Trees and native vegetation along shorelines keep the water cool for fish and help stabilize the banks from erosion. Help protect these types of areas in your community and watch for stream restoration projects and opportunities.

- Keep litter and trash out of streams. Trash can pile up on logs, sticks and other debris and block water flow. Summer is the best time for in-stream cleanup to reduce impacts to key salmon life-cycle stages that typically occur in spring and fall.

- Help protect natural shorelines, wetlands and floodplains in your community. These habitats are extremely valuable to both salmon and people.

- Look for sustainably-harvested salmon at your local supermarket or favorite restaurant. When fishing, be aware of relevant local and national regulations that may restrict what species or amounts you can take.

- Get to know your local watershed group and volunteer to get involved.

- Salish Sea Report Home

- Executive Summary

- About This Report

- Air Quality

- Freshwater Quality

- Marine Species at Risk

- Marine Water Quality

- Shellfish Beaches

- Southern Resident Killer Whales

- Stream Flow

- Swimming Beaches

- Toxics in the Food Web

- Acknowledgements

Klamath Chinook Salmon

Chinook salmon are one of seven salmon species native to the Pacific Ocean. Chinook salmon vary in size and age of maturation, with smaller size related to longer distance migration, earlier timing of river entry, and cessation of feeding prior to spawning. Young Chinook, known as fry and fingerlings, are 30-45 mm and 50-120 mm in fork length respectively. Chinook salmon mature at 30 pounds and 36 inches and are the largest of the Pacific salmon species; many adults exceed 40 pounds. As length corresponds to age, two year-old adults tend to be around 40 centimeters long, and six year-old adults often measure one meter in length.

Chinook salmon have a different appearance depending on location and lifecycle. In fresh water, juvenile Chinook are camouflaged by silver flanks with parr marks (darker vertical bars or spots) on the back, dorsal fin, and both lobes of the tail fin. Chinook also have black coloring along the gum line, making the mouth appear black.

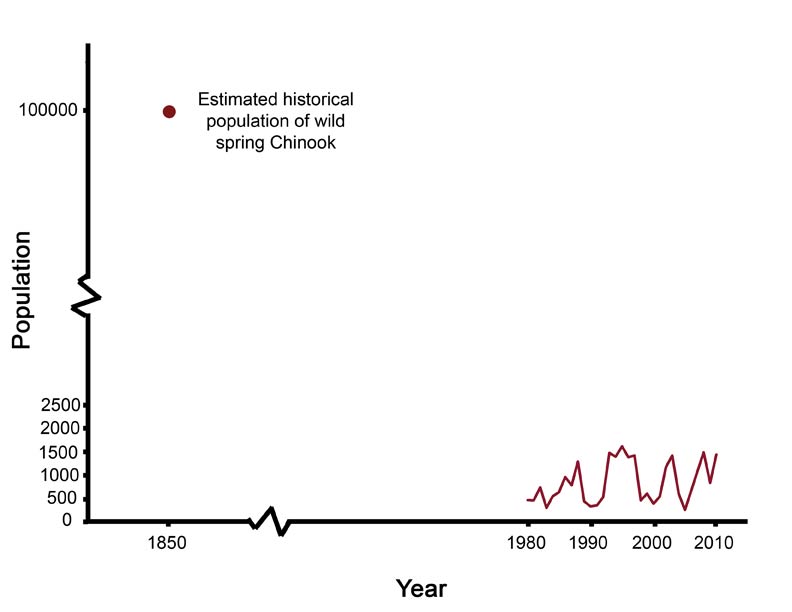

Why does it need our help?

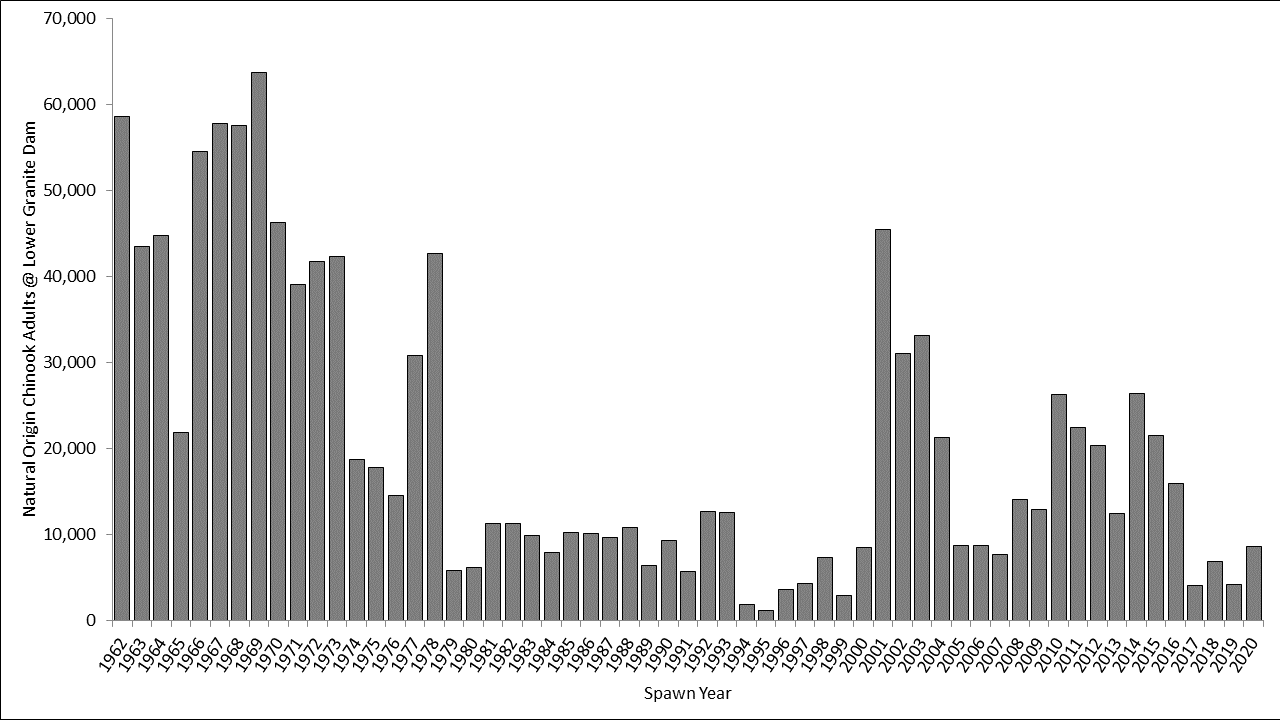

The spring run component of the Upper Klamath-Trinity Rivers ESU has seen dramatic declines from historic levels and is in danger of becoming extinct in the foreseeable future. Most known spring run populations have been extirpated and the few runs that do still exist have undergone severe declines, are small in size and many are overrun by hatchery fish, leaving the spring run at immediate risk of extinction. Several human caused and naturally occurring threats have led to the precarious status of spring run Chinook in the Klamath Basin, necessitating their protection under the Endangered Species Act.

In June 2021 the California Fish and Game Commission announced their unanimous decision to list the Klamath-Trinity River spring chinook salmon as an endangered species under the California Endangered Species Act.

Want regular news on our efforts to protect Oregon's imperiled wildlife, and what you can do to help? Sign up for our monthly Wolves and Wildlife Newsletter!

Did you know?

- Spring chinook salmon in the Klamath Basin once numbered over 100,000 but there are now fewer than a few thousand today (see chart below).

- Another name for chinook salmon is King salmon.

- Hundreds of miles of chinook spawning habitat are blocked by antiquated Klamath River dams.

- In September of 2002, 70,000 chinook salmon were killed in the Klamath River following a disease outbreak caused by excessive water diversions for agriculture. It was the worst fish kill in West Coast history.

Recent News

Hikes & events.

- Board of Directors

- Job Opportunities

- Accomplishments

- Business Partners

- Privacy Policy

- Oregon WildBlog

- E-Newsletter

- Print Newsletter

- Publications

- Join or Renew

- Evergreen Society

- Online Store

- Other Ways to Give

5825 North Greeley, Portland, OR 97217 503.283.6343 | Portland office 541.344.0675 | Eugene office 541.382-2616 | Bend office 541.886.0212 | Enterprise office [email protected]

Photography Credits

Science & Environment

Study: chinook salmon are key to northwest orcas all year, a new study from federal researchers provides the most detailed look yet at what the pacific northwest’s endangered orcas eat.

For more than a decade, Brad Hanson and other researchers have tailed the Pacific Northwest’s endangered killer whales in a hard-sided inflatable boat, leaning over the edge with a standard pool skimmer to collect clues to their diet: bits of orca poop floating on the water, or fish scales sparkling just below the surface.

Their work established years ago that the whales depend heavily on depleted runs of Chinook, the largest and fattiest of Pacific salmon species, when they forage in the summer in the inland waters between Washington state and British Columbia.

But a new paper from Hanson and others at the NOAA Fisheries Northwest Fisheries Science Center provides the first real look at what the whales eat the rest of the year, when they cruise the outer Pacific Coast — data that reaffirms the central importance of Chinook to the whales and the importance of recovering Chinook populations to save the beloved mammals.

By analyzing the DNA of orca feces as well as salmon scales and other remains after the whales have devoured the fish, the researchers demonstrated that the while the whales sometimes eat other species, including halibut, lingcod and steelhead, they depend most on Chinook. And they consumed the big salmon from a wide range of sources — from those that spawn in California's Sacramento River all the way to the Taku River in northern British Columbia.

A young resident killer whale chases a chinook salmon in the Salish Sea near San Juan Island, Washington, in September 2017.

Oregon State University/Flickr

“Having the data in hand that they're taking fish from this huge swath of watershed across western North America was pretty amazing,” Hanson, the study's lead researcher, said Wednesday. “We have to have hard data on what these whales are actually doing.”

There are officially 74 whales in the three groups of endangered orcas, known as the J, K and L pods of the southern resident killer whales. Three calves have been born since September, but those are not yet reflected in the count because only about half of the babies survive their first year.

Facing a dearth of prey, contaminants that accumulate in their blubber, and vessel noise that hinders their hunting, the whales are at their lowest numbers since the 1970s, when hundreds were captured — and more than 50 were kept — for aquarium display. Scientists warn the population is on the brink of extinction.

The paper, published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One, suggests that efforts to make Chinook more abundant off the coast in the non-summer months could especially pay off, and that Columbia River Chinook hatchery stocks are among the most important for the whales. It also suggests that increasing the numbers of non-salmon species could help fill the gaps for the whales when Chinook aren't available in the open ocean.

NOAA has already used some of the data, which has been available internally as scientists awaited the study's publication, in proposing what areas to designate as critical habitat for the whales. Officials could use it in prioritizing certain habitat restoration efforts or in timing hatchery production of salmon to best benefit the whales, said co-author Lynne Barre of the National Marine Fisheries Service's Protected Resource Division.

The information could also be key in setting limits for fisheries; the Pacific Fisheries Management Council has recommended that NOAA curtail fishing if Chinook abundance is forecast to drop below a certain level.

The researchers encountered the whales 156 times from 2004 to 2017, with most of the fecal and prey samples from the outer coast being collected in 2013 and 2015 — when the whales were easier to find because they were satellite tagged. There were big runs of Chinook those years, which might have been reflected in their findings; since then, Chinook numbers have fallen up and down the coast due to drought in California and warmer ocean conditions.

In the summer, when the whales forage in the inland waters of the Salish Sea, their diet is almost entirely Chinook — mostly those that return to spawn in Canada’s Fraser River, the paper said. By September, as coho salmon return to spawn in the region's rivers, they make up about half of the orcas’ diet, with a mix of Chinook, chum and coho providing sustenance through the fall.

In the winter, when the whales spend more time on the outer coast, they turn to non-salmon species, apparently because Chinook are more spread out and harder to find.

Barre said it may be surprising that the orcas focus so much on Chinook when there are so many other fish in the sea, but research has also suggested that the whales might target them because the nutritional value of the big, fatty fish is worth the calories burned catching them.

“It would certainly make our lives easier if they were eating a lot more of the other things that are available,” she said.

OPB’s First Look newsletter

Related stories, another calf born to endangered northwest orcas.

Whale researchers say another calf has been born to the endangered Southern Resident orcas of the Salish Sea

Streaming Now

TED Radio Hour

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, chinook salmon.

Last updated: February 8, 2018

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve PO Box 140 Gustavus, AK 99826

907 697-2230

Stay Connected

- 0 Shopping Cart $ 0.00 -->

Fish as seen in saltwater.

Chinook are the largest Pacific salmon and can weigh over 100 lbs. But on average, Chinook hit the scales at about 30 lbs. They’re long and heavy, in the range of 40 to 60 inches at maturity.

Tipping the Scales

The largest Chinook on record was a 126-pound specimen caught in a fish trap near Petersburg, Alaska in 1949. Sportfishers also caught a 97-pounder in the Kenai River in 1986. They are more abundant in North America than in Asia, and they can be found as far north as Alaska and as far south as Nevada.

Their flesh pigmentation varies widely, from deep pinks and reds to creamy white.

Spotting a Chinook

One of the nicknames for Chinook salmon is “blackmouth”, earned from gumlines that look painted with black pigment. When not spawning, they appear blue-green with silvery sides, and they have black spotting on their backs and dorsal fins and on both lobes of their tail fin.

When they are spawning, their colour goes richer, from deep red to coppery-black.

Habits and Habitat

Chinook often prefer larger river systems for their freshwater stays, but they can also be found in small tributaries and headwaters. They are famous for their strong swimming endurance and for the fantastic leaps they make when migrating. Chinook vary in their migratory habits, with some displaying a strong urge to move oceanward within weeks of hatching. Others are content to remain in freshwater for up to two winters.

Other Facts About Chinook:

- With long lifespans compared to other Pacific salmon, some Chinook remain in the ocean for more than five years before returning to their natal spawning grounds. They can be found in rivers throughout the year, but there is a seasonal peak from May to September.

- Chinook, as adults, vary greatly in size, as they can become mature adults (i.e., able to spawn) anywhere from the time they are two to seven years of age.

Join our Newsletter

First Name *

Last Name *

- State of Salmon

- Contributors

- Annual Report 2022

- Climate Action

- Community Investments

- Marine Science

- Salmon Health

- Salmon Watersheds

- Blog Stories

- Media Releases

- Species & Lifecycle

- Salmon Facts

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Knowledge Exchange Workshop Series

- Document Library

- Ways to Give

- Donate Online

Chinook salmon

The Chinook salmon is the largest of the Pacific salmon species and can reach upwards of 50 pound, though 10 to 25 pounds is more common. It's also known as a king salmon and is Oregon's state fish.

Features: While in the ocean, Chinook salmon often have a purple hue to their backs with silvery sides and bellies, large oblong black spots on the back , and round black spots on both lobes of the tail (note that tail spotting may be obscured in ocean fish by “silver” in the tail) . Upon returning to freshwater to spawn, Chinook darken in color and develop red on their bellies and fins. A key identifier is the black gum line on the lower jaw with dark colors both inside and outside of the gum line . Spawning generally occurs from August to early November for spring Chinook and from October to early March for fall Chinook.

Habitat: Juvenile Chinook will stay in freshwater for the first few months to couple of years of their lives. Afterwards, they will migrate to the Pacific to feed and grow to a size where they can make the trip back inland to spawn in their natal streams. They require clean, well-oxygenated freshwater to spawn. All adults die within two weeks after spawning.

Technique: Chinook can be caught by anglers both on boats and on shore. Using spinners or baiting with shrimp or anchovies is a safe bet in rivers . When fishing the ocean going deep with spoons, imitation squid or a whole herring or anchovy behind an attractor such as a dodger is usually the most productive method.

Check out the Latest Recreation Report

Current conditions and opportunities to fish, hunt and see wildlife. Updated weekly by fish and wildlife biologists throughout the state.

Hail to the King: How to Catch Chinook Salmon

Twenty commercial salmon fishermens' heads turned in unison away from the beach bonfire toward the loud splash like so many dogs hearing a squirrel. The tide had risen steadily up the adjacent creek mouth as we reveled under the midnight sun, and something big had just jumped.

“Was that a seal?” Podge asked.

“I saw it flash red,” Michael responded.

My 8-weight was still strung and leaning against the truck from harassing Dolly Varden earlier. I strolled over, hauled line, and launched a gaudy pink streamer across the outflow. I stripped it back in without interruption. The next cast I let sink a little longer before pulsing the fly. The line came tight in my hand then ripped free. The small crowd of seiner crewmen and women heard my drag shriek and began wandering over to watch the show.

Heavy is the Head that Wears the Crown Of the six species of salmon present in the Pacific Ocean (Chinook/king, coho/silver, dog/chum, sockeye/red, pink/humpback, masu/cherry), Oncorhynchus tshawytscha grows largest by several magnitudes. While chum and coho have been recorded into the mid-30-pound range, that size barely turns heads in many prominent Chinook fisheries. The current Chinook IGFA rod-and-reel record rests at 97 pounds, but fish breaking the 100-pound mark have emerged from commercial gear as well.