- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 31, 2023 | Original: February 2, 2018

Babylon was the largest city in the vast Babylonian empire. Founded more than 4,000 years ago as a small port on the Euphrates River, the city’s ruins are located in present-day Iraq. Babylon became one of the most powerful cities of the ancient world under the rule of Hammurabi. Centuries later, a new line of kings established a Neo-Babylonian Empire that spanned from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea. During this period, Babylon became a city of beautiful architecture, including the Hanging Garden of Babylon, the Ishtar Gate and the Tower of Babel.

Where Is Babylon?

The city of Babylon was located about 50 miles south of Baghdad along the Euphrates River in present-day Iraq. It was founded around 2300 B.C. by the ancient Akkadian-speaking people of southern Mesopotamia .

Babylon became a major military power under Amorite king Hammurabi , who ruled from 1792 to 1750 B.C. After Hammurabi conquered neighboring city-states, he brought much of southern and central Mesopotamia under unified Babylonian rule, creating an empire called Babylonia.

Hammurabi turned Babylon into a rich, powerful and influential city. He created one of the world’s earliest and most complete written legal codes. Known as the Code of Hammurabi , it helped Babylon surpass other cities in the region.

Babylonia, however, was short-lived. The empire fell apart after Hammurabi’s death and reverted back to a small kingdom for several centuries.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

A new line of kings established the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which lasted from 626 B.C. to 539 B.C. The Neo-Babylonian Empire became the most powerful state in the world after defeating the Assyrians at Nineveh in 612 B.C.

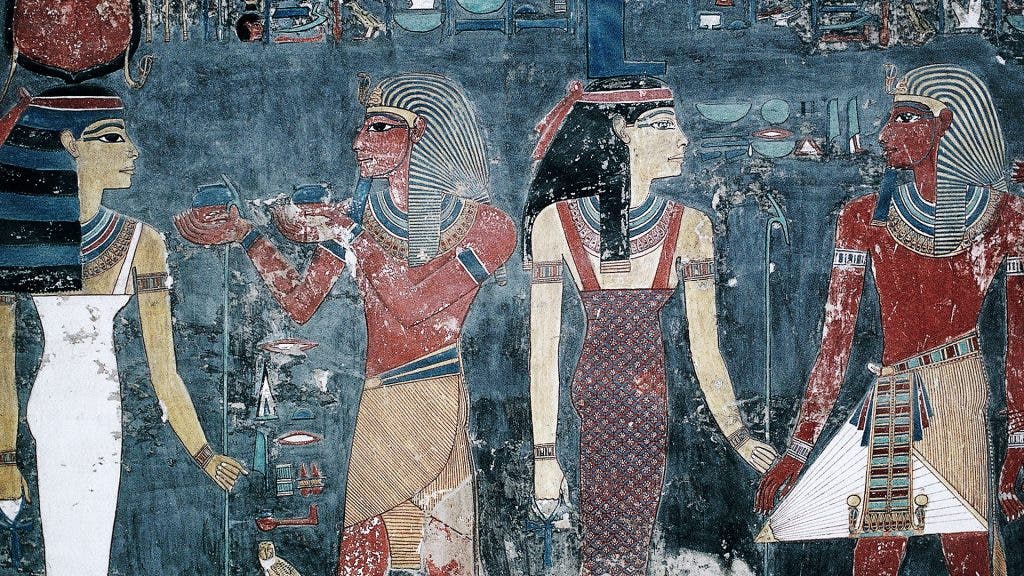

The Neo-Babylonian Empire enjoyed a period of cultural renaissance in the Near East. The Babylonians built many beautiful and lavish buildings and preserved statues and artworks from the earlier Babylonian Empire during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II .

Fall of Babylon

The Neo-Babylonian Empire, like the earlier Babylonia, was short-lived.

In 539 B.C., less than a century after its founding, the legendary Persian king Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. The fall of Babylon was complete when the empire came under Persian control.

Babylon in Jewish History

After the Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah in the sixth century B.C., Nebuchadnezzar II took thousands of Jews from the city of Jerusalem and held them captive in Babylon for more than half a century.

Many Judeans returned to Jerusalem after the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great’s Persian forces. Some stayed, and a Jewish community flourished there for more than 2,000 years. Many relocated to the newly created Jewish state of Israel in the 1950s.

Tower of Babel

The city of Babylon appears in both Hebrew and Christian scriptures. Christian scriptures portray Babylon as a wicked city. Hebrew scriptures tell the story of the Babylonian exile, portraying Nebuchadnezzar as a captor.

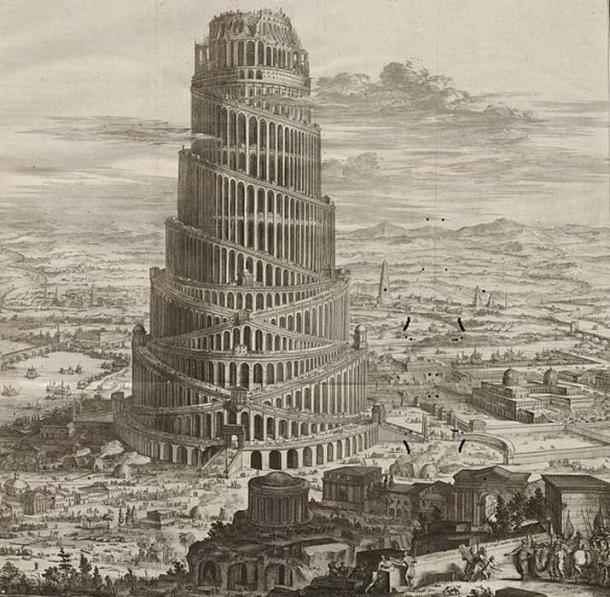

Famous accounts of Babylon in the Bible include the story of the Tower of Babel. According to the Old Testament story, humans tried to build a tower to reach the heavens. When God saw this, he destroyed the tower and scattered mankind across the Earth, making them speak many languages so they could no longer understand each other.

Some scholars believe the legendary Tower of Babel may have been inspired by a real-life ziggurat temple built to honor Marduk, the patron god of Babylon.

Walls of Babylon

Art and architecture flourished throughout the Babylonian Empire, especially in the capital city of Babylon, which is also famous for its impenetrable walls.

Hammurabi first encircled the city with walls. Nebuchadnezzar II further fortified the city with three rings of walls that were 40 feet tall.

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the walls of Babylon were so thick that chariot races were held on top of them. The city inside the walls occupied an area of 200 square miles, roughly the size of Chicago today.

Nebuchadnezzar II built three major palaces, each lavishly decorated with blue and yellow glazed tiles. He also built a number of shrines, the largest of which, called Esagil, was dedicated to Marduk. The shrine stood 280 feet tall, nearly the size of a 26-story office building.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, a colossal maze of terraced trees, shrubs, flowers and manmade waterfalls, are one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World .

Yet archaeologists have turned up scant evidence of the gardens. It’s unclear where they were located or whether they ever existed at all.

Some researchers have uncovered evidence that suggests the hanging gardens existed, but not in Babylon —they may have actually been located in the city of Nineveh in upper Mesopotamia.

Ishtar Gate

The main entrance to the inner city of Babylon was called the Ishtar Gate. The portal was decorated with bright blue glazed bricks adorned with pictures of bulls, dragons and lions.

The Ishtar Gate gave way to the city’s great Processional Way, a half-mile decorated corridor used in religious ritual to celebrate the New Year. In ancient Babylon, the new year started with the spring equinox and marked the beginning of the agricultural season.

German archaeologists excavated the remains of the gate in the early twentieth century and reconstructed it in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum using original bricks.

Babylon Today

Under Saddam Hussein , the Iraqi government excavated Babylonian ruins and attempted to reconstruct certain features of the ancient city, including one of Nebuchadnezzar’s palaces.

After the 2003 invasion of Iraq , United States forces built a military base on the ruins of Babylon. The United Nations cultural heritage agency UNESCO reported the base caused “major damage” to the archaeological site. The site was reopened to tourists in 2009.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Babylon; Metropolitan Museum of Art . Final Report on Damage Assessment in Babylon; UNESCO . Ancient tablets reveal life of Jews in Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon; Reuters . U.S. troops accused of damaging Babylon's ancient wonder; CNN .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Inside Etemenanki: The Real-Life Tower of Babel

- Read Later

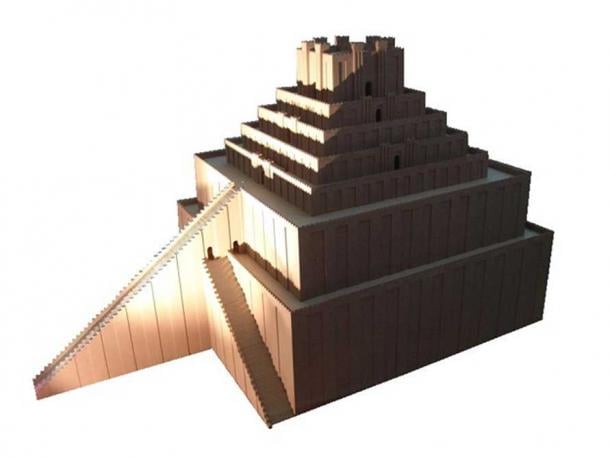

If there was a tower of Babel, it was Etemenanki: a massive, stone ziggurat at the center of Babylon built to be a passageway up to heaven. The Babylonians didn’t see their tower of Babel as a failure. As far as they were concerned, they really had made a stairway that they could walk up to go see the gods – and it really worked.

The Tower of Babel Was Real

The Bible wasn’t lying – the Babylonians really did make a tower “whose top may reach unto heaven”. They called it Etemenanki or the Ziggurat Babel , and it really was meant to be a stairway to heaven.

From the bottom, the Etemenanki would have looked like a staircase climbing up into the clouds. It was a massive, seven-level clay pyramid that climbed up 91 meters (300 feet) into the sky . To put that in perspective, that made it about the same height as New York’s Flatiron skyscraper, which, when it was built in 1902, was one of the tallest buildings on earth.

- By the Rivers of Babylon: Life in Ancient Babylon’s Thriving Jewish Community

- Ancient Babylonian use of the Pythagorean Theorem and its Three Dimensions

- The Babylonian Marriage Market: An Auction of Women in the Ancient World

‘The Tower of Babel’ (1563) by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. ( Public Domain )

But this wasn’t just a big building. Like the tower in the Biblical story, the Etemenanki was built in a deliberate attempt to make a staircase that climbed all the way up to the gods.

The tower was built on a spot that the Babylonians believed was the exact center of the universe. It was here, they believed, that their god Marduk created the world. Here alone, heaven and earth could interconnect… as long as someone could just build a staircase that went up high enough. That’s what the Etemenanki was meant to be – a staircase tall enough that you could climb it up to heaven.

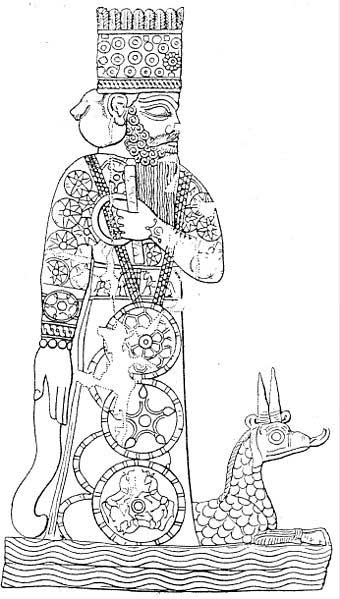

Marduk and his dragon Mušḫuššu, from a Babylonian cylinder seal. ( Public Domain )

Unlike the Bible story, though, the Etemenanki didn’t get knocked over by an angry god. The Babylonians finished building their tower to heaven, and they added a massive flight of stairs that climbed all the way up to the place that, they believed, connected heaven and earth.

They’d climb to the top of that building regularly. And while they were there, if they’re to be believed, they really did meet god.

From Athanasius Kircher. Turris Babel... Amsterdam, 1679. ( Public Domain )

An Inter-celestial Brothel

The top level of the Etemenanki was like a motel room for the gods. The floor was full of luxurious bedrooms, each one with the finest beds and couches they had to offer, bearing the names of the god they believed would spend the night there.

One was for Marduk and his wife Sarpanitum, another for Nabu and his wife Tashmetu. Others were set aside for the gods of water, light, and heaven. These places were decadent, lavishly decorated rooms, and they were left completely empty. They were put aside for the gods, who, as the priests assured the people of Babylon, regularly dropped by for vacations at the holy hotel.

This attendant god was found at the Temple of god Nabu at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. The cuneiform inscription mentions the name of the Assyrian king Adad-nirari III and his mother, Sammuramat. Circa 810-800 BCE. The British Museum, London. (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/ CC BY SA 4.0 )

The strangest part of the tower, though, was even higher up. Above the top level, there was a temple that contained nothing other than a couch and a table made of pure gold. Only one person in all of Babylon was allowed to visit it: a woman, chosen by the god Marduk, to be his lover .

The priests would let one woman in the city know that the god had been checking her out. They would send her up to the top of the tower to wait for Marduk. There, she would lay down on the couch and wait for Marduk to arrive. Nobody knows for sure exactly what really happened up there, but when she came down, she would be completely sure that she’d just made love to god himself.

Model of Etemenanki. Pergamonmuseum (Berlin). ( Public Domain ) The top level contained a temple for a chosen woman to meet Marduk.

The Ritual Murder of Substitute Kings

The tower wasn’t just a motel for the gods, though. It had other uses. Babylonian astronomers would climb up to the top of it to watch the skies – and they learned some incredible things.

Thanks in part to the Etemenanki, Babylon had an unparalleled understanding of the movements of the stars. They had detailed astronomical diaries that tracked their movements. They’d observed Venus as early as the 17th century BC; they’d made stellar catalogs by the 8th century BC; and, by the 7th century BC, they could even predict an eclipse.

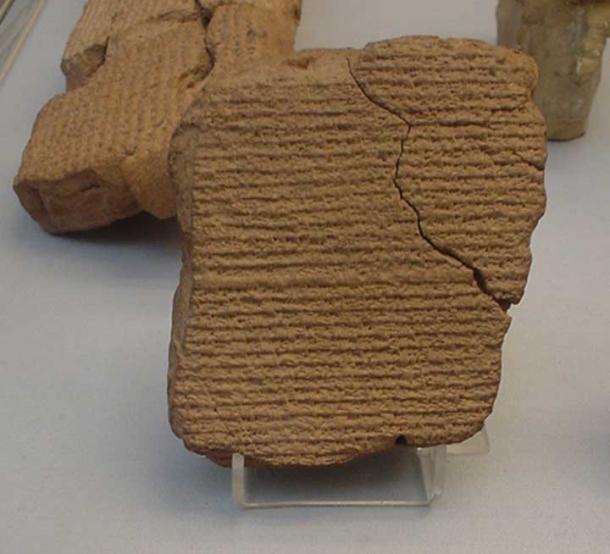

A Babylonian tablet recording Halley's comet during an appearance in 164 BC. At the British Museum in London. ( Public Domain )

That was an important job. In fact, in Babylon, the king’s life depended on it. The Babylonians had long believed that eclipses were the gods’ way of expressing their wrath with mankind. Before they learned how to track them, they were so desperate to appease the wrath of their gods that, if the moon appeared in front of the sun, they would literally murder their king.

That didn’t exactly change when they learned how to predict eclipses. Even though they knew that eclipses came and went at set intervals, they still stubbornly clung to the idea that they were signs of the gods’ anger. Now, though, they could crown a substitute king before an eclipse. They’d let some poor fool call himself king for a few days, then would kill him as soon as the eclipse began.

The real king would lay low until the eclipse was over, and then hop right back onto the throne of Babylon. Thanks to his astronomers at the top of the Etemenanki, he’d be able to cheat his way out of a ritual sacrifice.

Kudurru (stele) of King Melishipak I (1186–1172 BC): the king presents his daughter to the goddess Nannaya. The crescent moon represents the god Sin, the sun the Shamash and the star the goddess Ishtar. Kassite period, taken to Susa in the 12th century BC as war booty. ( Public Domain )

The Destruction of the Tower of Babel

There’s a reason the Israelites thought the Tower of Babel was in ruins. For most of human history, that would have been exactly what it looked like. The Etemenanki was a huge undertaking for an ancient civilization. It’s believed that it took more than a hundred years to build, and, until then, would have been in a state of disrepair.

Even when it was finished, the Etemenanki didn’t stay standing for long. It was torn down multiple times. First, the Assyrian king Sennacherib shattered and desecrated the tower after a particularly vicious war with Babylon. It was rebuilt by Nebuchadnezzar, only to be torn again by the Persian King Xerxes.

- The legendary Tower of Babel

- Ancient Babylonian Tablet Provides Compelling Evidence that the Tower of Babel DID Exist

- Gateway to the Heavens: The Assyrian Account to the Tower of Babel

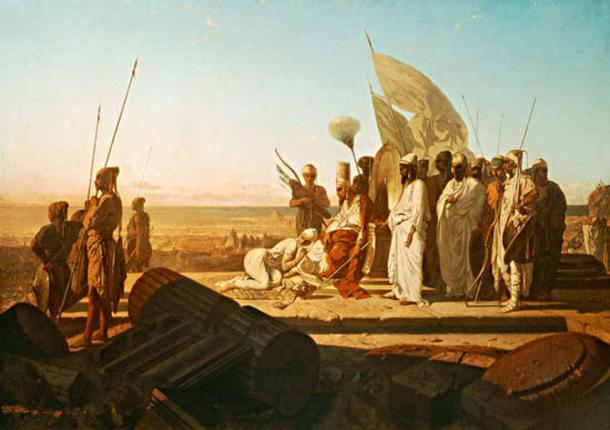

Xerxes at the Hellespont. ( Public Domain)

After Alexander the Great invaded Persia, he promised to rebuild it but, as far as anyone can tell, he never actually got around to doing it. He had his men tear down every last brick, but died before he actually put it back together again. And so, for thousands of years, the Tower of Babel lay in ruins.

It took more than 2000 years before modern archaeologists found it. The Etemenanki, though, really was there. We have found the foundation , stretched out 91 meters wide and 91 meters long at the center of a courtyard half a kilometer wide. It was exactly how the ancients described it.

Today, it’s nothing more than a few clay bricks buried under the dirt. But at one point, thousands of years ago, that clay held up a tower that rose all the way up to heaven.

‘The Tower of Babel’ (1594) by Lucas van Valckenborch. ( Public Domain )

Top Image: ‘The Tower of Babel’ (1595) by Lucas van Valckenborch. Source: Public Domain

By Mark Oliver

“Alexander Restores the Esagila”. Livius.org . 28 October, 2016, Available at: http://www.livius.org/sources/content/oriental-varia/alexander-restores-the-esagila/

“Etemenanki (the ‘Tower of Babel’)”. Livius.org. 12 April, 2018. Available at: http://www.livius.org/articles/place/babylon/etemenanki/

Graff, Sarah. “The Solar Eclipse and the Substitute King”. The MET. 30 August, 2017, Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2017/solar-eclipse-substitute-king

Herodotus. The Histories . Ed. A.D. Godley. Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:abo:tlg,0016,001:1:181

“Kidinnu, the Chaldaeans, and Babylonian Astronomy”. Livius.org. 4 April, 2018. Available at: http://www.livius.org/articles/person/kidinnu-the-chaldaeans-and-babylonian-astronomy/

Porter, Barbara N. Images, Power and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon’s Babylonian Policy. American Philosophical Society, 1993. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=J6toY--R430C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

And where is the proof that they weren't really visited by the gods?

I am a writer, a teacher and a father, with 5 years of experience writing online. I have written for a number of major history parenting and comedy websites. My writing has appeared on the front pages of Yahoo, The Onion,... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

- Corrections

The Tower of Babel in Art and Literature (6 Examples)

Explaining the existence and diversity of languages spoken around the globe, the Tower of Babel is an origin story that resounds throughout history, art, and literature.

The story of the Tower of Babel is told in the Book of Genesis 11:1-9, offering a parabolic, aetiological explanation as to why so many diverse languages are spoken around the world – and why, as a result, speakers of different languages struggle to communicate with each other. Originally, the world was monolingual. As the people migrate eastward, they come to the land of Shinar (southern Mesopotamia), where they resolve to build a city and tower that will reach up to the heavens. Yahweh, however, foils their plans by scattering them across the earth and confounding their language so that they can no longer understand each other and thus cannot continue building the tower. In doing so, a polyglottal humanity is born. It is a powerful origin story that has resonated with writers and artists throughout the ages. Here, we look at six examples of works of art and literature inspired by the Tower of Babel.

1. Folio 17v, The Bedford Hours (c. 1410-30)

Within the Roman Catholic faith, books of prayer for certain canonical times of day are known as books of hours. Manuscript examples from the Middle Ages are often lavishly illuminated , and few more so than The Bedford Hours , which boasts more than 1,200 historiated roundels.

The Bedford Hours was originally created to mark the wedding of Anne of Burgundy and John, Duke of Bedford (which, of course, is where the manuscript’s name is derived) on May 13th, 1423. On Christmas Eve 1430, however, Anne of Burgundy gifted the precious manuscript to the nine-year-old King Henry VI, her nephew.

Within a series of miniatures depicting scenes from the Book of Genesis, on Folio 17v of the Bedford Hours, the concurrent construction and divine demolition of the Tower of Babel is depicted in a full-page miniature. Laborers continue working on the construction of the tower, and Nimrod and his retinue come to survey their work (a scene taken from Flavius Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews , perhaps, rather than the Book of Genesis, in which Nimrod is not mentioned). All the while, however, divine forces are working against them. Thus, the image underlines the warning against greed and megalomania, as stated in the Book of Genesis.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription, 2. james joyce, finnegans wake (1939).

Published in 1939, Finnegans Wake is a monumental work within literary modernism. Deeply experimental and, according to some at least, near impenetrable in its linguistic idiosyncrasies, it is also a self-conscious inheritor of the legacy of the fall of the Tower of Babel: namely, the confusion of tongues. “The word ‘Babel’ is,” according to Jesse Schotter, “referred to at least twenty-one times in the Wake.” James’ preoccupation with the infamous tower is signaled from the very beginning of the novel, as “Finnegan’s fall” echoes “the fall of the Tower of Babel,” or, as Joyce refers to it, the “baubletop” (see Further Reading, Schotter, 89; Joyce, 5).

The confusion of tongues was a concern shared by many others besides Joyce in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was, after all, during this time that so-called “universal languages” were being invented, including Basic English, Novial, Volapuk, Istotype, and, most famously perhaps, Esperanto .

Like these “universal languages,” Joyce incorporates elements of tens of languages into Finnegans Wake – and, in earlier drafts of the novel, he even incorporated some Esperanto . If, however, these “universal languages” were attempts to overcome the confusion of tongues that resulted from the fall of the Tower of Babel, Joyce resists such attempts in his novel, reveling instead in the rich, polyglot cacophony that resulted from the fall of the “turrace of Babbel” (see Further Reading, Joyce, 199).

Joyce was skeptical of attempts to recover or return to a supposedly “pure” language that predated not only the fall of the Tower of Babel but the fall of man, too. In Finnegans Wake , as Schotter observes: “Joyce provides in his own version of a universal language not the solution to the problem of Babel but Babel itself” (see Further Reading, Schotter, 100).

3. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The (Great) Tower of Babel and The (Little) Tower of Babel

That the Tower of Babel exercises a fascination over the cultural imagination is especially true of Pieter Bruegel the Elder . Such was his obsession with the Tower of Babel that he painted it not once, not twice, but three times. The (Great) Tower of Babel and The (Little) Tower of Babel , however, are the only two pieces to survive, as the earliest piece of the three (a miniature painted on ivory) is lost. It has been suggested that Bruegel’s fascination was linked to the Reformation and the resultant rift between the Catholic Church (in which services were in Latin) and Protestantism.

Though The (Little) Tower of Babel is roughly half the size of The (Great) Tower of Babel , at first glance, the two paintings seem compositionally very similar, both depicting the construction of the Tower of Babel, the structure that dominates both paintings.

In addition, the two towers are architecturally very similar, evoking (according to John Malam) the Roman Colosseum. Just as the Colosseum had once seemed to depict the might of the Roman Empire, it now stands as a reminder of the ultimate transience of even once-powerful empires, and so the likeness Bruegel draws between the Colosseum and the Tower of Babel is apt. Both towers are also tilted and therefore unstable: in both paintings, the foundations are shown to be weak and the tower itself crumbling in places.

However, where The (Great) Tower of Babel is set on the edge of a cityscape, The (Little) Tower of Babel is surrounded on three sides by open countryside. Moreover, in The (Great) Tower of Babel, Nimrod and his entourage make an appearance (just as they do in Folio 17v of The Bedford Hours ), while The (Little) Tower of Babel is eerily devoid of human figures.

4. Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel” (1941)

“La Biblioteca de Babel” (The Library of Babel) is a 1941 short story by the acclaimed Argentinian writer and librarian Jorge Luis Borges. The story is set, as Borges’ narrator explains, in a universe that consists of an enormous library “composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries” (see Further Reading, Borges, 78).

Though the vast majority of the books in each room are compositionally formless and incoherent, among the shelves are also all the coherent books ever written. These books, however, are few and far between, and “for every sensible line of straightforward statement, there are leagues of senseless cacophonies, verbal jumbles and incoherences” (see Further Reading, Borges, 80). As for the books that are seemingly incoherent, the narrator suggests that some may only seem incoherent because a language in which they would become legible has yet to be devised.

As things stand, however, this means that the books are useless, much to the despair of the librarians in this universe. While some librarians are driven to destroy incoherent books (though the library is so vast that “any reduction […] is infinitesimal”), one “blasphemous sect” suggests “that all men should juggle letters and symbols until,” by chance, they re-produce the much longed for coherent, canonical books – thus exacerbating the original problem (see Further Reading, Borges, 83). Other librarians, however, seek a book that might provide an index or compendium for the library’s collection, devised by a quasi-messianic librarian (the Man of the Book) who has gone through the library archives.

The story can be read in light of Borges’ 1939 essay “La Biblioteca Total” (The Total Library). Here, Borges makes an explicit reference to Borel’s infinite monkey theorem, to which he only obliquely alludes in “The Library of Babel.”

5. Lucas van Valckenborch, La Tour de Babel, 1594

Lucas van Valckenborch the Elder was a contemporary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and, like Bruegel, he painted the Tower of Babel more than once. Before his 1594 painting, he also produced a painting of the Tower of Babel in 1568 and then went on to produce another in 1595. All three seem to be influenced by Bruegel’s works, though this is especially true of the 1568 and 1594 paintings. Also, like Bruegel, van Valckenborch drew inspiration from the Roman Colosseum in constructing his own Tower of Babel.

It is perhaps little wonder, however, that van Valckenborch was drawn to painting the Tower of Babel just as Bruegel was. As a contemporary of Bruegel, he was responding to many of the same historical events, including the fallout of the Reformation. Against this backdrop of religious strife within Western Christianity, the Catholic Church was also embarking on a series of major construction projects, including St. Peter’s Basilica.

If van Valckenborch sought to draw a parallel between the Catholic Church’s construction projects and the Tower of Babel in his paintings, the parallel would imply an indictment of the Catholic Church. And, as van Valckenborch and his brother and fellow artist Marten fled Antwerp (just as the figures in the foreground of his 1594 painting appear to be fleeing Babylon before the fire spreads) in the wake of the Beeldenstorm of 1566 before eventually taking refuge in Germany, it is thought that he was in all likelihood a Protestant .

6. A.S. Byatt, Babel Tower (1996)

Published in 1996, A.S. Byatt’s Babel Tower is her third novel focusing on the life of Frederica Potter. When Nigel, Frederica’s affluent and sadistic husband, attacks her with an axe, she flees their marital home with their young son, Leo, and moves to London. She finds employment as a teacher in an art school and mixes with poets, painters, and Jude Mason, a novelist whose latest work is being put on trial. When Nigel files for divorce, the two legal battles play out in tandem.

At the heart of Babel Tower is the question of language and the ways in which it can both facilitate and frustrate communication. During her divorce proceedings, Frederica’s literary tastes are weaponized against her, as her husband’s lawyers seek to convince the jury that a reading woman cannot a good mother make. Nor does the jury believe that Nigel attacked her with an axe. In this way, Byatt flags up the wiliness of the language of the law court.

Meanwhile, Jude’s novel, Babbletower, is on trial for obscenity. The suffering of the heroine of Babbletower , Lady Roseace, mirrors that of Frederica. Yet where the Jury seem inclined to view Frederica’s trauma as fiction, they view Jude’s fiction as pornography .

As the above examples attest, the story of the Tower of Babel has had a lasting hold on our collective cultural imagination. On a broader scale, it speaks to our sense of global fragmentation, and, within our private lives and personal relationships, it reminds us of the treachery of language, which is at once our primary means of communication and yet fraught with the latent danger of miscommunication. As such, it seems more than likely that the Tower of Babel will maintain its firm grip on the cultural imagination for many years to come.

Further Reading:

Borges, Jorge Luis, “The Library of Babel,” trans. by James E. Irby, Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings , ed. by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby (London: Penguin, 2000), pp. 78-86.

Byatt, A.S., Babel Tower (London: Vintage, 1997).

Joyce, James, Finnegans Wake (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Malam, John, Pieter Bruegel (Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books, 1999).

Schotter, Jesse, “Verbivocovisuals: James Joyce and the Problem of Babel,” James Joyce Quarterly , 48, 1 (2010), 89-109.

6 Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts That Will Amaze You

By Catherine Dent MA 20th and 21st Century Literary Studies, BA English Literature Catherine holds a first-class BA from Durham University and an MA with distinction, also from Durham, where she specialized in the representation of glass objects in the work of Virginia Woolf. In her spare time, she enjoys writing fiction, reading, and spending time with her rescue dog, Finn.

Frequently Read Together

What Is an Illuminated Manuscript?

4 Key Works by James Joyce You Need to Read

J.R.R. Tolkien: The Beloved Father of Fantasy

John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications

JOHN H. WALTON

MOODY BIBLE INSTITUTE

This paper investigates the history of ziggurats and brick making as well as the settlement patterns and development of urbanization in southern Mesopotamia . Gen 11:1-9 is interpreted in light of this information, and the conclusion reached is that tile tower, as a ziggurat , embodied the concepts of pagan polytheism as it developed in the early stages of urbanization. Yahweh took offense at this distorted concept of deity and put a stop to the project. The account is seen against the backdrop of the latter part of the fourth millennium in the late Uruk phase.

Key Words: ziggurat, Tower of Babel, Mesopotamia, Gen. 11:1-9

The familiar story of the building of the Tower and City of Babel is found in Gen 11:1-9. From the initial setting given for the account, on the plain of Shinar , to the final lines where the city is identified with Babel, it is clear that the events recorded took place in southern Mesopotamia.1 It is this southern Mesopotamian backdrop that provides the basis for studying the account in light of what is known of the culture and history of Mesopotamia. One of the immediate results of that perspective is firm conviction that the tower that figures predominantly in the narrative is to be identified as a ziggurat. This is easily concluded from the importance that the ziggurat had in the civilizations of southern Mesopotamia from the earliest development of urbanized life to the high political reaches of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. It is common for the ziggurat to be of central importance in city planning. The frequent objection that the Hebrew term lR:g]mi (migdal) is used primarily in military contexts or as a watch tower, but never used of a ziggurat, is easily addressed on three fronts.

1. We do not expect to see the term lR:g]m (migdal) used of ziggurats in Hebrew because the Israelites did not have ziggurats. 2. We do not expect the Israelites to have a ready term for ziggurats because ziggurats were not a part of the Israelite culture. 3. Given the absence of a term in Hebrew, we would expect them to either borrow the word if they had to talk about them, use a suitable existing term, or devise a word. To call the ziggurat a tower is not inaccurate, and as a matter of fact, the term they used is derived from the Hebrew term lrg (to be large), which is somewhat parallel to the etymological root of the

1 Whether Shinar = Sumer is now open to question in light of the analysis of Ran Zadok, “The Origin of the Name Shinar,” ZA 74 (1984) 240-44, but there is no doubt that it refers to southern Mesopotamia. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

Akkadian word, ziqqurat (zaqaru, to be high). Despite the fact then that the Hebrew term is used primarily in military senses or as watch towers, the context here and the known background of the narrative prevent us from being limited to that semantic range. A possible nonmilitary function of a mgdl may occur in Ugaritic as a place of sacrifice.2

Nearly thirty ziggurats in the area of Mesopotamia have been discovered by archaeologists.3 In location, they stretch from Man and Tell-Brak in the northwest and Dur-Sharrukin in the north, to Ur and Eridu in the south, and to Susa and Choga Zambil in the east. In time, the span begins perhaps as early as the Ubaid temples at Eridu (end of the 5th millennium BC) and extends through the restorations and additions made even in Seleucid times (3d c. BC). Architectural styles feature stairs in some, ramps in others, and combinations of the two in still others. Ziggurats are of varying sizes with bases ranging from 20 meters on a side to over 90 meters on a side. Frequently the ziggurat is dedicated to the city’s patron god or goddess, but cities were not limited to one ziggurat ( Kish had three).

The issues most likely to be of importance in the study of Genesis 11 are the origin and function of ziggurats. We may expect that by the study of these we may be able, to some degree, to delineate the role and significance of the ziggurat in Genesis 11.

Origin. The structure at Eridu, the earliest structure that some designate a ziggurat, is dated in its earliest level to the Ubaid period (4300-3500). There are sixteen levels of temples beneath the Ur III period ziggurat constructed by Amar- Sin (2046-2038) that crowns the mound. At which of these levels the structure may be first designated a ziggurat is a matter of uncertainty. Oates comments,

Convention clearly demanded that the ruins of one shrine should be preserved beneath the foundations of its successor, a practice that probably explains the appearance of the high terraces on which some of the latest prehistoric temples stood, and which may be forerunners of later times.4

This same phenomenon occurs with the so-called White Temple of Uruk dated to the Jamdet Nasr period (3100-2900). M. Mallowan remarks,

The so-called ziggurat or temple tower on which it [the white temple] was set had risen gradually in the course of more than a millennium, for in fact beneath the White Temple the tower incorporated within it a series of much earlier sanctuaries which after serving

2 Keret IV:166-72. 3 For the best analysis of these, see Andre Parrot, Ziggurats et Tour de Babel (London: SCM, 1955). 4 David and Joan Oates, The Rise of Civilization (New York: Elsevier Phaidon 1976) 132. We would suggest that “convention” is less responsible for this practice than the belief that the location and orientation of the temple had been ordained by the gods and was therefore not to be abandoned. It may also be overstatement to say that the previous shrine was preserved. While not totally demolished, it was filled with brick or rubble so as to serve as a suitable foundation for its successor. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

their time had been filled solid with brickwork and became terraces for later constructions.5

It is difficult to determine what should be called a ziggurat and what should not. The criteria used by the ancients is unknown to us. For our purposes, we will define a ziggurat as a staged tower for which the stages were consciously constructed. That seems to be what is taking place in Genesis 11. Therefore, even though the temples on accumulated ruins were probably the forerunners of the staged towers, the “stages” (made up of accumulated ruins) were not constructed for the tower. It is only when builders construct stages (possibly modeled after the piled up ruins) that we will acknowledge the designation ziggurat. This also rules out the oval terraces.

The Early Dynastic period (2900-2350) is the most likely candidate for the origin of the ziggurat so defined. H. Crawford concedes that “there can now be little doubt that some sort of staged tower does go back to the Early Dynastic period, although there is no evidence for an earlier occurrence.”6 The clearest evidence of this is at Ur. There, “the Early Dynastic ziggurat is completely engulfed by that of Ur-Nammu, but its existence can be safely deduced from the remains of the period in the surrounding courtyard area.”7 Man also has a firmly established Early Dynastic ziggurat. At Nippur , superimposed ziggurats built by Ur-Nammu (2112-2095) and Naram-Sin (2254-2218)

[p.158] have been confirmed, and it seems likely that a pre-Sargonic ziggurat serves as a foundation.8

Function. There have been many different suggestions concerning the function of a ziggurat, and the issue is far from settled. Brevard S. Childs presents a brief summary of some of the major opinions:

The older view that the ziggurat was a representation of a mountain, brought from the mountainous homeland of the Sumerians to Babylon , has been shown as only a secondary motif by recent investigation. Busink has demonstrated from Eridu that the original ziggurat had nothing to do with a mountain. However, in that the Babylonians later on compared the ziggurat to a mountain, this may well be at the best a secondary motif acquired during its later development. Then again, Dombart’s attempt to find in the ziggurat a throne concept has found little acceptance. Andrae advanced in 1928 the view that the temple-tower must be seen as a unity, the former being the dwelling place of the god, the latter his place of appearing. But in 1939 he retracted this view in favor of one in which the temple-tower provided the holy place for the resting of the divine spirit. Both Schott and Vincent have defended the idea that the tower was the entrance door through which the god passed to the lower temple. Lenzen, however, has attacked this theory, defending that the primary significance is that of an altar. Finally, Busink concludes that a development must have taken place in the long history of the ziggurat as to its meaning.

5 Max Mallowan, Early Mesopotamia and Iran (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965) 41. 6 Harriot Crawford, The Architecture of Iraq in the Third Millennium B.C. (Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, 1977) 27. 7 Ibid. 8 Parrot, Ziggurats, 154. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

He feels that originally perhaps the practical necessity of protecting the temple against flood and plunder was primary, but admits also that religious motives must have played an important role in its development.9

One of the earliest interpretations understood the ziggurat as the tomb of a king or a god,10 although this was not necessarily considered the sole function. There were two major supporting arguments for this view. The first was the obvious similarity in shape to the early Egyptian pyramids. The second is connection in the inscriptional literature between the term ziggurat and gigunu, which was rendered “tomb” by Hilprecht.11

In regard to the former, the earliest pyramid, the so-called step-pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, bears the closest resemblance to the ziggurat form. It has been demonstrated that the architectural form

[p.159] of the Egyptian pyramids began as a simple mastaba and was built up in several stages.12 The step-pyramid was a product of the third dynasty in Egypt (mid-3d millennium BC), which was contemporaneous with the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia. Although the extant evidence seems to indicate that the architectural form of the ziggurat became fully developed by that period, the development had begun perhaps a millennium earlier. Thus the ziggurat form can in no way be seen as dependent on the pyramids. Furthermore, no literary or artifactual evidence has produced any indication that the ziggurat functioned as a tomb.

With regard to the latter argument, the gigunu is no longer understood as a tomb, but rather as a sanctuary at the top of the ziggurat,13 though the precise meaning of the word remains uncertain.

One approach to examining the function of a ziggurat—and in my opinion, the only approach that can give objective data, given our present state of knowledge—is to analyze the names given to the ziggurats in the various cities where they were built. Rather than attempting to use our own standard to judge what is a ziggurat and what is not, we will use a list of designated ziggurats from a Neo-Babylonian bilingual geographical list of 23 entries.14 Following is my translation of the list:

1. Temple of the Foundation of Babylon Heaven and Earth 2. Temple of the Wielder of the 7 Decrees of Borsippa

9 B. S. Childs, “A Study of Myth in Genesis I-XI” (Unpublished dissertation, Heidelberg: 1955) 99-100. The assertion that Busink demonstrated that the ziggurat had nothing to do with a mountain is perhaps overzealous. While Busink’s evidence suggested other formative elements as more likely, the mountain motif cannot be entirely discarded. 10 Hermann Hilprecht, Explorations in Bible Lands (Philadelphia: Holman, 1903) 469. 11 Ibid, 462. 12 I. E. S. Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1946) 46ff. 13 CAD G, 67-70. 14 II Rawlinson 50:1-23 a, b. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

Heaven and Earth15 3. [. . .] gigir Nippur 4. Temple of the Mountain Breeze Nippur 5. Temple of Mystery Nippur 6. ? Kurigalzu 7. Temple of the Stairway to Pure Heaven16 Sippar

8. Temple of the god Dadia Akkad 9. ? Dumuzi (?) 10. Temple of the Admirable Throne/Sanctuary Dumuzi (?) 11. Temple of the Ziggurat, Kish Exalted Dwelling Place 12. Temple of the Exalted Mountain Ehursagkalamma 13. Temple of Exalted Splendor Enlil (at Kish?) 14. Temple of the god Nanna Kutha 15. Temple of the Foundation of Dilbat Heaven and Earth17 16. ? Marad 17. ? Ur 18. Temple which Links Heaven and Earth Larsa 19. Temple of the Giparu Uruk 20. Temple of the Ziggurat Eridu 21. ? Enegi 22. ? Enegi

We may now attempt to categorize the names with the hope of finding some clues about the function of ziggurats.

1. Two of the ziggurats are named for the god (8, 14; probably also 2). 2. Three names seem to involve general praise (13, 21, 22).18 3. Two names make reference to the structure or parts of the structure (19, 20).

15 This name is reconstructed, although there is little doubt of the reading. The transliteration is presented as [ É .UR4.ME].IMIN.AN. KI . The name of the ziggurat of Nabu in Borsippa is well-known. ME is a variable in the name, so it may or may not have occurred in this tablet. The meaning traditionally suggested is “Temple of the seven masters of heaven and earth.” This would be logical, it is argued, if each of the seven levels of the ziggurat were (as Rawlinson postulated) dedicated to one of the seven major heavenly bodies (cf. RLA 1:422). This view, however, does not enjoy a consensus and fails to give adequate explanation of the ME variant. I have posited the present translation based on the role ascribed to manna in Inanna ’s Descent to the Netherworld (cf. Falkenstein, AfO 14 [1942] 115:14-15; W. W. Hallo and J. van Dijk, The Exaltation of Inanna [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968] lines 5-8.). 16 This reading follows the generally accepted emendation. Cf. ŠL 2:2 , 568#84 and CAD Z, 130-31. 17 The signs on this as they stand would be read É.DU.BA.AN.K1 and this is retained by Deimel. I have read SUHUŠ(!) (=išdu) which appears as a combination of DU + BA. The meaning of DU.BA is obscure, although DU alone is a variant of SUHUŠ for išdu. 18 In #21 the name is restored as É.U6.D1.GAL.[AN.NA], where U6.DI + tabratu, “praise.” #22 is read É.ARATTA2.KI.KI.SÁR.RA. If ARATTA = Akk. kabtu, “honorable” (cf. ŠL 3:1, 19, though somewhat dubious) praise would be intended. KI.ŠAR.RA = kiššatu and expresses totality. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

4. Two names feature mountain terminology (4, 12). 5. Six names seem to address the role or function of the ziggurat (1, 7, 10, 11, 15, 18).

Of the six names that seem to address the function of the ziggurat, two indicate a cultic function, that is, that the ziggurat in some way housed the deity (10, 11; this, of course may also be conveyed by the names in category 1). The other four may indicate a cosmological function, that is, they may indicate that the ziggurat symbolized the connecting link between heaven and earth, or between heaven and the netherworld. The ziggurat at Sippar, temple of the stairway (simmiltu) to pure heaven, is particularly indicative of such a function because of the occurrence of the simmiltu in the myth of Nergal and

Ereshkigal.19 In this tale, the stairway is used by Namtar, the messenger of Ereshkigal, to journey from the netherworld to the gate of the gods Anu , Enlil, and Ea.20 It serves as the link between the nether-world and heaven.21 That the simmiltu occurs in the name of one ziggurat and that another means the “Temple which links heaven and earth” (18) may indicate that the ziggurat was intended to supply a connection between heaven and earth—not for mortal use, but for divine use. This is supported to some degree by the total absence of the ziggurats in the cultic rituals. S. Paths remarks,

Anyone who has perused the whole of the material is struck by the remarkable fact that Etemenanki [the fabulous ziggurat of Babylon] is nowhere mentioned in the description of the course of the [akitu] festival though numerous other sacred localities in Babylon are referred to. Nor do we meet with any reference to ceremonies performed here. Indeed, I believe I may add that beyond the constant reference to the building of Etemenanki or “its head” in the inscriptions of the Neo-Babylonian kings, and the frequent mention of it in hymns where it is referred to or invoked in conjunction with Esagila , Ekur and other temples, we find nothing about Etemenanki or its religious uses in the entire Assyro- Babylonian literature.22

19 O. Gurney, “The Sultantepe Tablets: The Myth of Nergal and Ereshkigal,” Anatolian Studies 10 (1960) 123:13-14; 125:42-43. 20 Akkadian simmiltu has cognates in many Semitic languages . B. Landsberger, “Lexicalisches Archiv,” ZA 41 (1933) 230-31 lists the following: “neusyr. simelta; mand. sumbilta; altsyr. sebbelta; hebr., jud.-aram., arab. mit Metathese, sullam.” Cf. AHW 1045. The Hebrew sullam is used only in the story known as “Jacob’s Ladder” in Gen 28:12. In Jacob’s dream the sullam is set up with its head reaching toward the heavens. Messengers of God (cf. Namtar in Nergal and Ereshkigal) were going up and down it. This certainly does not indicate a procession, but rather indicates that messengers to earth were using this stairway/ladder to set out on and return from their missions. Upon awaking, Jacob comments concerning the house of God as well as the “gate of the heavens”— thereby conforming quite closely to general ancient Near Eastern perceptions. For discussion of this see A. R. Millard, “The Celestial Ladder and the Gate of Heaven” ET 78 (1966) 86-87; C. Houtman, “What did Jacob See in His Dream at Bethel?” VT 27 (1977) 337-51; and H. R. Cohen, Biblical Hapax Legomena in the Light of Akkadian and Ugaritic (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1978) 34. 21 The ziggurat name ending AN.KI could be translated “heaven and nether-world” rather than “heaven and earth” in that ers?e tim can refer to either (CAD E). The Hittite texts which speak of a ritual ladder being lowered into pits for the spirits of the dead also use the symbol KUN(5) for the ladder. See H. Hoffner, “Second Millennium Antecedents to the Hebrew -‘ôb,” JBL 86 (1967) 385-401. 22 Svend Pallis, The Babylonian Akitu Festival (Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1926) 103-4. A survey of occurrences of ziqquratu in CAD further confirms the lack of references to the cultic use of the ziggurat. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

It cannot, of course, be concluded that the ziggurat was not used in the rituals. We can only say that whatever its use may have been, if it had one, it is unknown to us. While Paths is addressing the

[p.162] situation with regard to the ziggurat of Babylon, we would add that the same is true of all of the ziggurats known from the ancient Near East. If the known literature were our only guide, we would have to conclude that people did not use the ziggurat for any purpose.23

The mountain terminology used in some of the names is also of interest. In ancient mythologies certain mountains were often considered to be the place where deity descended or dwelt. The Bible likewise implies such a connection. YHWH comes down on a mountain (Sinai, Exod 19) and sacrifice is made on a mountain (Moriah, Gen 22; Carmel, 1 Kgs 18). Moses , Aaron, and Elijah, three of the most central figures in Israelite religion, all go up into a mountain for the meeting with YHWH at the end of their lives. In the Ugaritic Baal-Anat cycle, the temple of Baal is built on the summit of Mount Zaphon. The motif is likewise present in Greek mythology , Mount Olympus being the home of the gods.

Although the function of the ziggurat cannot be identified with certainty, our study of the names, the use of the simmiltu in mythology, the use of mountain terminology, and the hack of reference to a function in the cultic practice of the people, leads us to put forth tentatively, as a working hypothesis, the following suggested function:

The ziggurat was a structure that was built to support the stairway (siminiltu), which was believed to be used by the gods to travel from one realm to the other. It was solely for the convenience of the gods and was maintained in order to provide the deity with the amenities that would refresh him along the way (food, a place to lie and rest, etc.). The stairway led at the top to the gate of the gods, the entrance to the divine abode.

Before we move on to consider the implications of this function of the ziggurat for the narrative of Genesis 11, we need to look at a few more elements that can be further explained in light of the narrative’s Mesopotamian background.

Building Materials

Discussion of the building materials occupies the whole of Gen 11:3. The first half of the verse indicates that burnt bricks are being used and the second half the verse contains an explanation by the author to those who might be unaware of the details of this “foreign” practice.

23 By this I mean in general worship. Certainly the fertility rituals where a high-priestess cohabited with deity would have taken place in the deity’s chamber on top of the ziggarat. It has also been thought that astrological observation was made from the top of the ziggarat, though I have been unable to confirm any such references to this sort of use prior to the Neo-Babylonian period. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

Our current knowledge of ancient architecture and industry confirms the statement made by the author. In Palestine, mud bricks (sun-dried) are first found in levels designated pre-pottery Neolithic A (8th-9th millennium BC).24 This is the only type of brick found in Palestine. Kiln- fired brick is unattested. The practice was rather to use stone for the foundations and sun-dried brick for the superstructure.25

Sun-dried bricks first appear in Mesopotamia at Samarran sites Sawwan and Choga Mami (mid-6th millennium BC).26 Kiln-fired bricks are first noted during the late Uruk period and become more common in the Jamdet Nasr period toward the end of the fourth millennium.27 Bitumen is the usual mortar used with kiln-fired bricks.28 The building technology of Palestine used a mud mortar (as indicated in our narrative). Bitumen of any grade was an expensive item,29 as Singer notes:

Being expensive, it was seldom used for walls of sun-dried bricks... except to make the walls and floors of such buildings impervious to water.... It was, however, widely used in baked brick buildings. These, again because of the cost of fuel, were expensive, and were normally used only for palaces, temples, and other official buildings. The low firing temperature of the bricks (550-600 degrees C.) resulted in a high porosity; thus the mastic was freely absorbed and gave such strength that the walls made of it are stronger than rock and any kind of iron.30

Not only is the description of the building materials an accurate reflection of a true distinction between Israelite and Mesopotamian building methods, but it also gives us some important information. Whole cities were not generally built of these materials. Even ziggurats themselves only used burnt brick and bitumen for the outer layers while using regular sun- dried mud brick for the inner layers. The core was then filled with dirt.31 The mention of the expensive

[p.164] building materials would thus suggest that the discussion is focusing on public buildings.

Public buildings were frequently of either religious or administrative importance and were often grouped together in one section of the settlement. They became the focal point for the centralization of wealth and for the preservation of many aspects of the individual culture. It

24 Kathleen Kenyon, Archaeology in the Holy Land (4th ed.; New York: Norton, 1979) 26. 25 Ibid. 46, 87, 91, 164, etc. 26 David and Joan Oates, The Rise of Civilization (New York: Elsevier Phaidon, 1976) 104. 27 Jack Finegan, Archaeological History of the Ancient Near East (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1979) 8; and C. Singer, The History of Technology (vol. 1; Oxford: Clarendon, 1954) 462. Cf. Arnias Salonen, Die Ziegeleien im alten Mesopotamien (Annales Academiac Scientiarum Fennicae 171; Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia 1972) 72ff. 28 Cf. Leonard Woolley, Ur Excavations: The Ziggurat and Its Surroundings (New York: British Museum and University Museum of Pennsylvania, 1939) 99. 29 R. J. Forbes. Studies in Ancient Technology (vol. 1; Leiden: Brill, 1955) 4-22. 30 C. Singer, The History of Technology, 1, 250-54. 31 I am, grateful to Prof. D. J. Wiseman for this information. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175. was the public sector of the city that was fortified and contained the stores of grain. Thus Hilprecht notes,

The temple complex of Nippur, with the dwellings of numerous officials, embraced the whole eastern half of the city, an area of almost eighty acres. The so-called inner and outer walls of Nippur cannot refer to the whole city, as one would have supposed from the inscriptions, but in accordance with the topographical evidence must be limited to the Temple of Bel (even to the exclusion of the temple library).32

Although it is possible that the author wants to make the point that this endeavor was attempting to build an entire city of the most expensive materials, I find it more plausible that the public sector of the city is intended. In the end, this is probably a difference without a distinction, for the earliest “cities” were simply the administrative buildings. Thus, when the people in Genesis 11 speak of building a city, they are most likely not referring to building of a residential settlement, but would have in mind the building of public buildings, which in ancient Mesopotamia would be largely represented by the temple complex. C. J. Gadd, writing of Early Dynastic times, observes that “the distinction of city and temple becomes dim, for one was only an agglomeration of the other.”33 The focus of any major temple complex would have been the ziggurat, which leads us into the next section.

The Importance of the City and the Tower

We cannot say that the building project described in Genesis 11 was exclusively a temple complex, but a temple complex certainly was included and is the focus of the story This is confirmed by the nature of the building materials, the nature of the ancient city, and the role of the ziggurat in the narrative. This ziggurat was the dominant building of the complex, so we are not surprised that that draws the attention of the narrator. Although we have already examined the function of the ziggurat, the role of the temple complex as a whole in Mesopotamian society may now be of some significance to our study.

Reference has been frequently made in the past to the administration of the so-called temple economy, which was deduced by Deimel and Falkenstein mainly from the Early Dynastic texts from Lagash and Shuruppak.34 The main feature of the temple economy was purported to be the exclusive or almost exclusive temple ownership of land. Falkenstein added that the temple had at its disposal not only the labor resources of the temple personnel, but the labor force of the entire city-state for tasks concerning the temple.35 Although this theory has been largely overturned in more recent analyses,36 the temple complex was likely the center of the earliest efforts of urbanization, a process that is characterized by public buildings, specialized labor, and some publicly owned land. Jacobsen comments:

32 Hermann Hilprecht, In the Temple of Bel at Nippur (Philadelphia: Holman, 1904) 14-15. 33 CAH3 1:2, 128. 34 For the limitations of the evidence, see CAH3 1:2, 126. 35 Falkenstein, The Sumerian Temple City (Los Angeles: Undena, 1974) 19-20. 36 Benjamin Foster, “A New Look at the Sumerian Temple State,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 24 (1981) 225-41. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

The centralization of authority which this new political pattern made possible may have been responsible, along with other factors, for the emergence of a truly monumental architecture in Mesopotamia. Imposing temples now began to rise in the plain, often built on gigantic artificial mountains of sun-dried bricks, the famous ziggurats. Works of such proportions clearly presuppose a high degree of organization and direction in the community which achieved them.37

So we find that the develepment of ziggurats and the urbanization process go hand in hand.38 The ziggurat was the architectural focus of the temple complex, which in turn functioned as the central organ in the economic, political, and cultural spheres of early communities in Mesopotamia. The interrelationship of architecture, city planning, and religion has been observed in the interpretation of the finds in ancient Uruk. Hans Nissen says,

We can deduce from the completely different layout of the two shrines in the Late Uruk period that there must have been greater differences here than can be expressed merely by the assumption that we are dealing with different divinities. While in the western area, a terrace that was a good ten meters high, on which stood a high building visible from afar, the precinct of Eanna was completely differently organized. All the buildings were erected upon flat ground without the slightest elevation. Whereas in the western area it was already impossible, from the point of view of the building, for there to be more than one cult building, the layout of Eanna does not exclude the possibility that

several such cult buildings were in use simultaneously. This difference in external organization can definitely be traced back to differences in the organization of the cult and can thus also clearly be traced back to different basic religious concepts.39

The connections between Genesis 11 and the early stages of urbanization in Mesopotamia are further confirmed by the statement of the builders in Gen 11:4 that they desired not to be scattered abroad. Although this statement has often been interpreted as an indication of disobedience on the part of the builders, such a view cannot be warranted.40 First, the disobedience that is attributed to the builders is generally explained by reference to the blessings of Gen 1:28 and Gen 9:1, 7 where God says to be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. But a correlation here cannot be sustained. The passages that speak of being fruitful and multiplying are better read as blessings granting permission, rather than commands; privileges, rather than obligations.41 Further, it is clear that even if filling was seen as an obligation, it would be carried out by reproducing, not by putting geographical distance between oneself and one’s family. Scattering is not to be equated with filling.

The second point against the disobedience interpretation is the existence of a much more plausible alternative for understanding the statement. If the builders desired to prevent

37 Th. Jacobsen, Before Philosophy (ed. Henri Frankfort; Baltimore: Penguin, 1946) 141. 38 Cf. Falkenstein, “The development of civilization is most closely connected with the temples of the country” (Sumerian Temple City, 5). 39 Hans Nissen, The Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000-2000 BC (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988) 101; Cf. also pp. 102-3. 40 This interpretation is as early as Josephus (Ant. 1.4) and persists in many commentaries today. 41 On the permissive function of the imperative see GKC 110.b. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175. scattering, then we must assume that something was forcing them to scatter. The Old Testa- ment does witness to a pressure to scatter that arises from internal conditions. Gen 13:6-9 records a situation that arose between Abraham and Lot in which they would no longer remain together because of conflict between their men. This would have involved competition for prime grazing land and for campsites nearer to water sources. The constant need for the patriarchs to travel to Egypt in time of famine (i.e., when there is not enough food to meet subsistence level requirements) likewise demonstrates what to them was a fact of life: the number of people that can reside in any given area is directly related to the climatic conditions and land fertility. Cooperation among residents (as initially practiced by Abraham and Lot) can increase the ratio, but eventually the growth in numbers will necessitate dispersion. Perhaps more frequently, the cooperative effort will fail. Both reasons are mentioned in Genesis 13—their possessions became too great, and their men fought.42

Scattering, then, is not being avoided by disobedience. It is rather a fact of life in nomadic and seminomadic societies that is counterproductive to cultural continuity. It is natural that the builders would want to counteract the need to scatter. The solution to this is the development of a cooperative society, which by pooling their efforts and working together can greatly increase production. In a word—the solution is urbanization.

Living together in such close quarters meant that conflicts had, rather, to be actively controlled, leading to the setting up of rules for resolving conflicts. As we have already seen, situations where people lived together in close proximity could only arise in the intensively cultivated irrigation areas. Thus it was also the inhabitants of these areas—that is, especially of Babylonia —who found themselves confronted by these challenges and had to find answers to them. The need to establish rules enabling people or communities to live together is far more important in encouraging the higher development of civilizations than the need to create purely administrative structures.43

From every angle, then, the narrative, taken against its historical and cultural background, continually points us to the early period of urbanization in southern Mesopotamia. But how does this relate to YHWH’s response to the builders’ efforts? Are we to conclude that ur- banization is somehow contrary to YHWH’s plan? While some have taken this route, it seems a difficult one to maintain given YHWH’s choice of a city, Jerusalem, for the dwelling place of his presence. It is more likely that there would be something that was characteristic of the urbanization process within Mesopotamia that would be identifiable as the problem. Again, our knowledge of Mesopotamian backgrounds can provide some possible explanations.

The administration of the early cities was in the hands of a general assembly.44 This form of government lasted only briefly as the need for decisive action led to the evolution of the

42 Cf. Gen 36:7. 43 Nissen, Early History of the Ancient Near East, 60-61. 44 Jacobsen refers to this system of government as “Primitive Democracy.” The aptness of this designation is disputed, but the role of the assembly is not. Edzard views the process less a democracy and more a “public sounding board” (cf. The Near East: The Early Civilizations, ed. Bottero, Cassin, and Vercoutter; New York: Delacorte, 1967] 80). Jacobsen suggests that the structure can be seen on a larger scale in the role of Nippur and John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175. institution of kingship. Although its period of operation was relatively brief, the general assembly format of government left a permanent impression on Mesopotamian society in that this was the form of government that mythology depicted as used by the gods. As the urbanized state

[p.168] began to function, the universe came to be considered a state ruled by the gods.45 Details concerning the pantheon and its operation prior to this shift are few and often obscure. Jacobsen has presented the view that the earlier picture of the gods was one in which each god, or numinous power, was seen as bound up by a particular natural phenomenon through which he was made manifest. The god was seen to be the power behind the phenomenon, and the phenomenon circumscribed the power of the god and was the god’s only form.46

As the situation developed, however, a change took place. Rather than continuing to emphasize the powerful uncontrolled manifestation of deity in natural phenomena, the view of the cosmos as a state emerged, with the now humanized gods as citizens and rulers. Mesopotamian theology that is reflected in most of the mythology of Babylon and Assyria has an urbanized society as its foundation. This theological perspective arose sometime early in the urbanization process, for even the Early Dynastic literature reflects that point of view. One indicator of this shift is the sudden popularity of the practice of setting up statues in temples that were intended to pray for the life of the benefactor. Nissen observes,

We can assume that it is highly probable that the custom of setting up statues in temples with this intention began in the Early Dynastic Period. This observation is of interest insofar as it certainly reflects a change in religious ideas. A notion of a god that makes it conceivable that the god can be influenced in this way differs fundamentally from the one that sees in the god only what is spiritually elevated. It is a humanization of the divine image such as we have already seen as a precondition for the theological speculations about a pantheon in which the ranking order of the gods among themselves was expressed in the form of family relationships.47

The ziggurat and the temple complex provide the link between urbanization, of which they are the central organ, and Mesopotamian religion which they typify. The ziggurat and the temple complex were representative of the very nature of Mesopotamian religion as it developed its characteristic forms. The essence of this new perspective, represented by the ziggurat and temple complex, is highlighted by Lambert.

The theology of the Sumerians as reflected in what seem to be the older myths presents an accurate reflection of the world from which they spring. The forces of nature can be brutal and indiscriminate; so

Enlil in Early Dynastic I. He refers to this as the Kengir League (Toward the Image of Tammuz [ed. W. Moran; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970] 137- 41, 157-72). 45 Jacobsen, Before Philosophy, 142. 46 Jacobsen, “Formative Tendencies In Sumerian Religion,” Toward the Image of Tammuz, 2. 47 Nissen, The Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000-2000 BC, 155. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

were the gods. Nature knows no modesty; nor did the gods.... In contrast the Babylonians grappled with facts and tried to reduce the conflicting elements in the universe to parts of a harmonious whole. No longer using the analogy of natural forces, they imagined the gods in their own image.48

Jacobsen further comments:

Particularly powerful and concrete in the new anthropomorphic view was the symbol of the temple, the god’s house. Towering over the flat roofs of the surrounding town, it gave the townsmen visible assurance that the god was present among them.49

The development in Mesopotamian religion that took place with the development of urbanization, was that men began to envision their gods in conformity with the image of man. Man was no longer attempting to be like God, but more insidiously, was trying to bring deity down to the level of man. The gods of the Babylonians were not only understood to interact with each other and operate their affairs as humans do, but they also behaved like humans, or worse. Finkelstein observes,

The Babylonian gods ... although not themselves BOUND by moral or ethical principles, nevertheless appreciated them and expected man to live by them. The Babylonians, it would seem, fashioned their gods in their own image more faithfully than the Israelites did theirs.50

This is what is represented by the ziggurat. The function of the ziggurat that was suggested earlier as a result of our study of the names further supports this. The needs and nature of the deities who would make use of such a stairway reflect the weakness of deity brought about by the Babylonian anthropomorphization of the gods. It is this system of religion that was an outgrowth of the urbanization process as it unfolded in Mesopotamia, and it was this system that had as its chief symbol the towering ziggurat. The danger of the action of the builders then has nothing to do with architecture or with urbanization. Nothing was wrong with towers or with cities. The danger is found in what this building project stood for in the minds of the builders. To the Israelites, this would be considered the ultimate act of religious hubris , making God in the image of man. This goes beyond mere idolatry; it degrades the nature of god.

One could perhaps object to this interpretation on the grounds that it requires the ziggurat or the temple complex in Genesis 11 to be a “silent” symbol of the Mesopotamian religious system. In fact, it

[p.170] is no more silent a symbol than the courtyard of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican Square. The editor’s own presentation of the material demonstrates their understanding of the symbol. In Gen 11:6, YHWH says this is only the beginning of what men will do. What is the end result?

48 W. Lambert, Babylonian Wisdom Literature (Oxford: Clarendon, 1960) 7. 49 Jacobsen, Toward the Image of Tammuz, 13. 50 J. J. Finkelstein, “Bible and Babel,” Commentary 26 (1958) 440. John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

The editor’s answer to that question is given by means of a rhetorical device: “Therefore its name was called Babel” (Gen 11:9). It was the Babylonians who eventually committed the offense.51 This offense lay not in the building of buildings, nor in the architectural structure itself, nor in the effort that achieved it. In the eyes of the editor, the intentions of the builders were innocent enough, but now, behold what their ziggurat had come to represent! The hubris was committed by those who carried on from that innocent yet auspicious beginning and brought to fruition the very evil that YHWH had foreseen—the degradation of deity. As the modern poet has voiced it:

The more the gods become like men, the easier it is for men to believe the gods. When both have only human appetites, then rogues may worship rogues.52

Unlike the modern interpretations, which suggest that there was no offense and that YHWH, acting in grace, prevented offense from occurring, we would suggest that the offense was not prevented, but rather delayed and isolated by YHWH’s action. By confusing the languages, God made cooperation impossible; therefore, scattering could no longer be prevented. Thus the urbanization process was delayed.

We cannot deny the possibility that this account was understood by the Israelites as being pregnant with political implications. Its main intent, though, we would argue, would seem to be not political polemic, nor even the account of yet another offense. Rather, the account demonstrates the need for God to reveal himself to the world. The concept of God had been corrupted and distorted; this would require an extensive program of reeducation to correct. So it was that God chose Abraham and his family and made a covenant with them.

The covenant would serve as the mechanism by which God would reveal himself to the world through Israel.

The Historical Setting of the Tower of Babel

As is evident from the above, I believe that the account of Genesis 11 has a solid historical foundation in early Mesopotamia. The details are authentic and realistic. The identification of the urbanization process and the accompanying development of the ziggurat with fundamental changes in the religious perspectives of the people demonstrates the keen analytical insight of the biblical author. Is it possible to suggest a particular historical period as the background of the event recounted in this narrative? First, a review of the pertinent information:

51 Though it is possible that this building project was attempted at Babylon, current evidence suggests that the city is not that ancient. I would allow that the name Babel is used here as identification of the contemporary example of what was wrought in that initial incident. 52 Calvin Miller, The Song (Downers Grove: Inter Varsity, 1977) 32. Cf. C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: chiefly on Prayer (New York: Macmillan, 1964) 68: “On the one hand, the man who does not regard God as other than himself cannot be said to have a religion at all. On the other hand, if I think God other than myself in the same way in which my fellowmen, and objects in general, are other than myself, I am beginning to make Him an idol. I am daring to treat His existence as somehow parallel to my own.” John H. Walton, “The Mesopotamian Background of the Tower of Babel Account and Its Implications,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-175.

1. Development of baked brick technology: Jamdet Nasr, ca. 3100 BC 2. Development of Ziggurat: Early Dynastic Period, ca. 2500 BC (earlier prototypes go back to the Late Uruk phase, ca. 3200 BC) 3. Development of Urbanization: Early Dynastic Period, ca. 2800 BC 4. Government by Ruling Assembly: Early Dynastic I, ca. 2900 BC

When considering the impact of this information, two caveats must be identified. First, in the biblical account the tower of Babel is presented as a failed prototype. The result of God’s action against the builders was to delay the development of urbanization in Mesopotamia. Consequently, it would be logical to infer that the event recorded in Genesis 11 occurred perhaps centuries prior to the actual development of urbanization as attested by archaeological records. Second, development of institutions may have taken place prior to the Early Dynastic period, but written records are not available to inform us of those developments. Writing developed in the Late Uruk period, but is limited to basic economical use for some time.

Besides the archaeological information that has been discussed, we must also consider that the account must have support from our understanding of the history of linguistic development and from settlement patterns in Mesopotamia. Taking all of this information into account, the Ubaid period (5000-3500) is most intriguing. Ubaid is a site in southern Mesopotamia just northwest of Ur. The Ubaid period witnesses the first settlements in southern Mesopotamia, with many of the sites being built on virgin soil.53 The sites in the northern section of Mesopotamia that attest the earlier settlements (e.g., Jarmo, Hassuna, Samarra, Halaf) appear not to continue into this period, though Ubaid cultures are attested in the north as well as the south. This pattern suggests that the Ubaid period witnessed the initial

[p.172] migration from the north into southern Mesopotamia, in notable agreement with Gen 11:2. Nissen has described the developments of this period in southern Mesopotamia and suggested a cause for the events:

A prolonged period in which only very scattered individual settlements existed was suddenly followed by a phase in which the land was clearly so densely settled that nothing like it had been seen even in the Susiana of the previous period. With the help of information from the Meteor research project, an explanation for this development in Babylonia is now possible. The land, which had been unsuitable for settlement owing to the high sea level in the Gulf or the large amount of water in the rivers, had at first supported only a few island sites, but from the moment the waters began to recede it was open to much more extensive habitation.54

The results of studies of the ancient climate and of the changes in the amount of water in the Mesopotamian river system and in the Gulf ... now present us with a clearer picture of the developments in southern Babylonia. The climatic changes documented for the middle