National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Inside the Controversial World of Slum Tourism

People have toured the world’s most marginalized, impoverished districts for over a century.

Hundreds of shanty towns line the riverbanks, train tracks, and garbage dumps in the Filipino capital—the most jammed-packed areas in one of the world’s most densely populated cities. Around a quarter of its 12 million people are considered “informal settlers.”

Manila is starkly representative of a global problem. According to the United Nations , about a quarter of the world’s urban population lives in slums—and this figure is rising fast.

Rich cultural heritage brings visitors to Manila, but some feel compelled to leave the safety of the historic center sites to get a glimpse of the city’s inequality. Tour operators in the Philippines —as well as places like Brazil and India —have responded by offering “slum tours” that take outsiders through their most impoverished, marginalized districts.

Slum tourism sparks considerable debate around an uncomfortable moral dilemma. No matter what you call it—slum tours, reality tours, adventure tourism, poverty tourism—many consider the practice little more than slack-jawed privileged people gawking at those less fortunate. Others argue they raise awareness and provide numerous examples of giving back to the local communities. Should tourists simply keep their eyes shut?

Around a quarter of Manila's 12 million people are considered “informal settlers."

Rich cultural heritage brings visitors to Manila, but some feel compelled to leave the safety of the historic center sites to get a glimpse of the city’s inequality.

Slumming For Centuries

Slum tourism is not a new phenomenon, although much has changed since its beginning. “Slumming” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in the 1860s, meaning “to go into, or frequent, slums for discreditable purposes; to saunter about, with a suspicion, perhaps, of immoral pursuits.” In September 1884, the New York Times published an article about the latest trend in leisure activities that arrived from across the pond, “‘Slumming’ will become a form of fashionable dissipation this winter among our Belles, as our foreign cousins will always be ready to lead the way.”

Usually under the pretense of charity and sometimes with a police escort, rich Londoners began braving the city’s ill-reputed East End beginning around 1840. This new form of amusement arrived to New York City from wealthy British tourists eager to compare slums abroad to those back home. Spreading across the coast to San Francisco, the practice creeped into city guide books. Groups wandered through neighborhoods like the Bowery or Five Points in New York to peer into brothels, saloons, and opium dens.

Visitors could hardly believe their eyes, and justifiably so. “I don’t think an opium den would have welcomed, or allowed access to, slummers to come through if they weren’t there to smoke themselves,” Chad Heap writes in his book Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife , 1885–1940 . Recognizing the business opportunity, outsiders cashed in on the curiosity by hiring actors to play the part of addicts or gang members to stage shoot-’em-ups in the streets. After all, no one wanted the slum tourists to demand a refund or go home disappointed.

Smokey Tours does not allow participants to take photos, but this policy proves difficult to enforce.

The city of San Francisco eventually banned such mockery of the poor, the New York Times reported in 1909: “This is a heavy blow to Chinatown guides, who have collected a fee of two dollars each. The opium smokers, gamblers, blind paupers, singing children, and other curiosities were all hired.”

Tours also brought positive results, as Professor of History Seth Koven highlights in his research of slumming in Victorian London. Oxford and Cambridge Universities opened study centers in the late 19th-century to inform social policy, which was only possible by seeing the underprivileged neighborhoods firsthand.

Popularity waned after World War II with the creation of welfare and social housing—then rose again in the 1980s and 1990s as those state provisions declined and labor demands increased.

Presenting Poverty

Plastic arrives from all over India to the dark alleys and corrugated shacks of Dharavi in Mumbai —the second-largest slum on the continent of Asia (after Orangi Town in Pakistan ) and third-largest slum in the world. Ushered around by the company Reality Tour and Travel , tourists see a thriving recycling industry which employs around ten thousand to melt, reshape, and mould discarded plastic. They stop to watch the dhobiwallahs , or washermen, scrub sheets from the city’s hospitals and hotels in an open-air laundry area.

In a TripAdvisor review, one recent participant from Virginia appreciated the focus on community. “It was great to hear about the economy, education and livelihood of the residents,” she writes. “The tour group doesn't allow photography or shopping which I think is really important. It didn't feel exploitative, it felt educational.”

One traveler from London commented on the extremity of the scene. "Had to stop after about 20 minutes into it due to the overbearing nature of the surroundings. The tour is not for the faint hearted. I would've liked a few more disclaimers on the website to warn us about the nature of it." Another guest from the United Kingdom expressed disappointment over the so-called family meal. “This was in the home of one of the guides and, whilst his mum made lunch a delicious meal that we ate in her house, she didn’t eat with us so it wasn’t really what I had expected from a family lunch (or the photos promoting such on the website).”

Smokey Tours enters the Manila North Cemetery, inhabited by some of Manila's poorest people.

Children jump from grave to grave in the city’s largest cemetery.

Reality Tours hopes to challenge the stereotypical perception of slums as despairing places inhabited by hopeless people. The tour presented slum residents as productive and hardworking, but also content and happy. Analyzing more than 230 reviews of Reality Tour and Travel in her study , Dr. Melissa Nisbett of King’s College London realized that for many Dharavi visitors, poverty was practically invisible. “As the reviews show, poverty was ignored, denied, overlooked and romanticized, but moreover, it was depoliticized.” Without discussing the reason the slum existed, the tour decontextualized the plight of the poor and seemed only to empower the wrong people–the privileged, western, middle class visitors.

With good intentions, the company states that 80 percent of the profits benefit the community through the efforts of its NGO that works to provide access to healthcare, organize educational programs, and more. Co-founder Chris Way spoke to National Geographic after his company surged in popularity from the sleeper hit Slumdog Millionaire . “We do try and be as transparent as possible on our website, which does allay many people’s fears.” Way personally refuses a salary for his work.

No Two Cities Alike

The main question should be: Is poverty the central reason to visit?

Other cities take different approaches to slum tourism. In the early 1990s, when black South Africans began offering tours of their townships—the marginalized, racially-segregated areas where they were forced to live—to help raise global awareness of rampant human rights violations. Rather than exploitation inflicted by outsiders, local communities embraced slum tourism as a vehicle to take matters of their traditionally neglected neighborhoods into their own hands.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

Some free tours of favelas in Rio de Janeiro provided an accessible option to the crowds that infiltrated the city during the World Cup and Summer Olympics, while most companies continue to charge. Tour manager Eduardo Marques of Brazilian Expeditions explains how their authenticity stands out, “We work with some local guides or freelancers, and during the tour we stop in local small business plus [offer] capoeira presentations that [support] the locals in the favela. We do not hide any info from our visitors. The real life is presented to the visitors.”

Smokey Tours in Manila connected tourists with the reality facing inhabitants of a city landfill in Tondo (until 2014 when it closed) to tell their stories. Now the company tours around Baseco near the port, located in the same crowded district and known for its grassroots activism. Locally-based photographer Hannah Reyes Morales documented her experience walking with the group on assignment for National Geographic Travel. “I had permission to photograph this tour from both the operator and community officials, but the tour itself had a no photography policy for the tourists.” With the policy difficult to enforce, some guests secretly snapped photos on their phones. “I observed how differently tourists processed what they were seeing in the tour. There were those who were respectful of their surroundings, and those who were less so.”

All About Intention

Despite sincere attempts by tour operators to mitigate offense and give back to locals, the impact of slum tourism stays isolated. Ghettoized communities remain woven into the fabric of major cities around the world, each with their individual political, historical, and economic concerns that cannot be generalized. Similarly, the motivations behind the tourism inside them are as diverse as the tour participants themselves. For all participants involved, operators or guests, individual intentions matter most.

The Baseco neighborhood is located on the Pasig river near the city port, but lacks access to clean drinking water.

Better connections between cities allow more people to travel than ever before, with numbers of international tourists growing quickly every year. While prosperity and quality of life have increased in many cities, so has inequality. As travelers increasingly seek unique experiences that promise authentic experiences in previously off-limits places, access through tours helps put some areas on the map.

Travel connects people that would otherwise not meet, then provides potential to share meaningful stories with others back home. Dr. Fabian Frenzel, who studies tourism of urban poverty at the University of Leicester, points out that one of the key disadvantages of poverty is a lack of recognition and voice. “If you want to tell a story, you need an audience, and tourism provides that audience.” Frenzel argues that even taking the most commodifying tour is better than ignoring that inequality completely.

For the long-term future of these communities, the complex economic, legal, and political issues must be addressed holistically by reorganizing the distribution of resources. While illuminating the issue on a small scale, slum tourism is not a sufficient answer to a growing global problem.

Related Topics

- TRAVEL PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOGRAPHY

You May Also Like

Photo story: wild beauty in eastern Sardinia, from coast to mountains

How I got the shot: Richard James Taylor on capturing Mekong sunset magic in Laos

Free bonus issue.

How I got the shot: Dikpal Thapa on risking it all for one image

How to visit Grand Teton National Park

These are the best travel photos of 2022

How I got the shot: Richard James Taylor on capturing Dubrovnik's golden hour

The Masterclasses 2023: 10 practical tips to help you succeed as a travel photographer

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Pros And Cons Of Slum Tourism: Crass Voyeurism Or Enlightened Travel?

Let me begin by saying I have engaged in slum tourism (a basic definition of slum tourism would be the kind of tourism that takes you to see impoverished communities).

I took an African slum Soweto tour during a long-ago visit to South Africa, to see a place that overflowed with meaning. In 1976, during the Soweto Uprising in which unarmed students were stormed and killed by police for refusing to study in Afrikaans, I was a university student in Political Science, engulfed (at a distance) in liberation movements and revolutions. Soweto was part of that, as well as a major chapter in the bigger South African story of apartheid and discrimination.

It was a place I wanted to see, but the then boycott of South Africa was in full swing and I would have to wait nearly two decades.

Years later as a journalist, I was escorted through some of the most crowded favelas in Rio by a young community nurse who worked with drug addicts and knew everyone. He was respected and we were stopped on every corner for a bit of a chat.

The afternoon I spent in Rocinha gave me a slightly better understanding of the poverty that fuels much of the addiction and crime, something I certainly would not have learned from the back of a bus.

It also showed me a side that surprised me – the regular everyday life of people less fortunate than myself. The streets were dirty and the housing rickety but people came and went, shopped, talked, laughed – and went to work, determined to make things better.

Oddly enough, at least to me, not everyone was poor . Walking around highlighted differing characteristics of slums. Some dwellings were decidedly middle-class, because here as everywhere else, when people succeed they don’t necessarily want to leave their friends and family.

Over the years, visits to poorer urban and slum areas have left me unsettled. Children sniffing glue under a bridge in Brasilia. Mothers scavenging on the world’s biggest scrap heap in Manila. Begging for food near a Nairobi slum. Homeless children in Malawi.

These are scenes that drive home the accident of humanity, of where I happened to be born, of my race and privilege, and how easily it might have been otherwise.

On the one hand, it showed me what is life like in a slum, but on the other, it left me unsure of whether I was engaging in ethical tourism.

So was slum tourism positive or detrimental, and does it hurt or help a slum economy? it still begs to question; “Is slum tourism good or bad?”

WHAT IS A SLUM? AND WHAT IS SLUM TOURISM?

SLUM DEFINITION

• noun: 1 – a squalid and overcrowded urban area inhabited by very poor people. 2 – a house or building unfit for human habitation.

• verb: ( slummed , slumming ) (often slum it) informal voluntarily spend time in uncomfortable conditions or at a lower social level than one’s own.

Source: Compact Oxford English dictionary

Slum tourism has been around since Victorian times , when wealthy Londoners trudged down to the East End for a view. The end of apartheid in South Africa fueled a more politically-oriented type of ‘township tour’ while Rocinha has been receiving tourists for years – some 50,000 a year now.

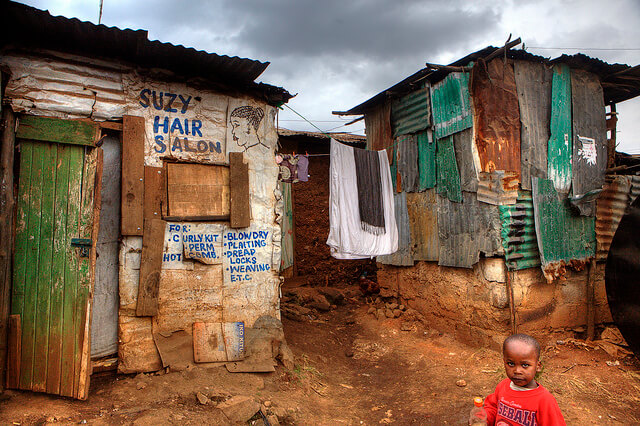

In India, the release of the movie Slumdog Millionnaire created space for even more slums of India tours. In Nairobi, enterprising Kenyans are guiding tourists on Kibera slum tours, one of the better-known urban slums (and one of the world’s bigger slum areas) with a population of one million inhabitants.

The voyeur aspect of slum tourism makes me intensely uneasy.

Imagine a busload of foreign visitors traipsing down your street, peering into your house, taking a selfie in front of your door… Yet that’s exactly what happens on some township tourism slum tours, often labeled poverty tourism, pity tours, ghetto tourism, reality tours or even poorism – there is no dearth of labels.

So is slum tourism ethically acceptable or is it exploitative? What are the advantages and disadvantages of slum tourism? Do our tourist dollars actually help these communities or are we simply paying for a peek into lives we have no intention of ever experiencing for more than a few minutes? What are the impacts of slum development?

SLUM TOURISM PROS AND CONS

Negatives of slum tourism: exploitation and voyeurism.

Why slum tourism is bad (or can be):organized slum visits have come under harsh criticism , particularly as they become more popular.

Much of the criticism revolves around these slum tourism cons:

- Slum tours treat people like animals in a zoo – you stare from the outside but don’t dare get too close.

- Visitors aren’t interested in meaningful interaction; they just want their photo op . Contact with locals is minimal.

- Money rarely trickles down. Instead, operators fill their pockets but the vaunted ‘benefits to the community’ don’t materialize. Slum tourism profits from poverty, which is why it is often called “poverty tourism”.

- People feel degraded by being stared at doing mundane things – washing, cleaning up, preparing food, things that are private. Their rights to privacy may be violated. Imagine yourself at the receiving end: how would you feel?

- Even when they participate as hosts, local people are often underpaid and exploited .

- The image of a country may be tarnished by publicizing slums (this is an actual concern among certain segments of certain populations – usually the more wealthy).

- The tours make poverty exotic , otherworldly, almost glamorizing what to inhabitants is a harsh reality which will remain once the tourists are long gone, which is one of the main slum tourism disadvantages.

How true is this picture?

UN-HABITAT defines a slum household as a group of individuals living under the same roof in an urban area who lack one or more of the following: 1. Durable housing of a permanent nature that protects against extreme climate conditions. 2. Sufficient living space which means not more than three people sharing the same room. 3. Easy access to safe water in sufficient amounts at an affordable price. 4. Access to adequate sanitation in the form of a private or public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people. 5. Security of tenure that prevents forced evictions.

Slum tourism benefits: improving local lives

So are there slum tourism advantages? There may be a flip side. Slum tourism has supporters, many of whom believe tourism will ultimately benefit the favela or the township and help improve the lives of people who live there.

Visitors who take these tours may genuinely care and are interested in knowing more about the people they meet and the places they see.

Here are some of the potential benefits of slum tourism:

- Even if it’s only a little, some money does enter the community , whether through meals at home or the purchase of art or souvenirs. Many say this tourism boosts the local economy. This trickle-down economy is bound to be better for local residents than picking trash off a stinking garbage heap.

- The tours change our perceptions of poverty by putting a face to it and showing visitors that however poor, people are the same everywhere and share similar thoughts and emotions.

- Tourists will visit areas they would never go to otherwise.

- Some operators have made sure part of their profits are recycled into local hands, for example by starting local charities .

- A spotlight on poor areas by foreigners may help governments move more quickly to improve conditions by using tourism as an economic developement tool.

- Even in the poorest areas development and innovation can take place: slum tours can showcase the economic and cultural energies of a neighborhood.

- They can improve our understanding of poverty and of one another – and of the world at large.

- Local people may support them. Locally-run slum tourism examples include Zezinho da Rocinha’s own favela tour (a slum-dweller himself, see below what he has to say on the effects of tourism in his community).

- They can bring us closer and demystify and debunk some of our stereotypes . This excellent video (below) by one of my favorite authors, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, highlights the dangers of what she calls a ‘single story’, or what happens when a single point of view is hammered home, in this case, the ‘single story’ of poverty and pity.

THE SLUM TOURISM DEBATE: SO, IS IT A GOOD THING OR A BAD THING?

There is no such thing as a star system for slum tours, an ethical rating that will tell you how well an operator is performing or what the real economic benefits of tourism in the community really are. So, it’s up to us to find out before booking.

Here are some of the things we should look for:

- Size matters . A huge tour rumbling through a neighborhood in an air-conditioned bus is probably not going to promote much interchange with local residents. Ask how many people will be on your tour.

- Look at the highlights and figure how long you’ll be in each place. If you’re expected to eat in a home, visit a local shebeen and walk through several streets in the space of an hour, chances are you won’t be getting to know your hosts in any significant way. Visitors need and have asked for more time for real exchanges with local people, as real as such unequal exchanges can be. Make sure you have enough time to interact.

- Explore how the tour was designed . Who put it together? Who came up with the itinerary? Why are you visiting one place and not another? Ask the organizers if local people were involved, and double-check once you’re in the community.

- Follow the money. Find out where the profits go and if the tourism economics are more beneficial than harmful. Are some profits returned to the community? What has been achieved – are there more schools, projects, education or jobs as a result? Ask the operators, and double check their answers.

Granted, much of this information will not be easy to find, especially before you book.

But you have the ethical obligation to find out: what are the disadvantages of slum tourism in the area you are visiting? But by asking the right questions, you are showing you care, and are forcing tour operators to tackle these issues .

Once you’re on the tour, you’ll have a better sense of its ethics and if you don’t like what you see, there’s always social media. If a tour is exploitative – well, word gets around fast.

There are many signs slum tourism is changing the future of tourism.

More charities are being set up to spread profits around, local people are becoming increasingly involved, negative stereotypes are being challenged, local artisans are being encouraged to sell their work to tourists at fair prices, and tour operators themselves are beginning to understand that slum tourism is not like mass tourism: they don’t have to cram every possible attraction into the shortest possible time.

While some feel much good can come from properly thought-out slum tours , others believe slum tourism has done more harm than good, with insensitive itineraries pulled together purely for gain.

So which is it: Would visitors be better off staying in a luxury downtown hotel while pretending not to see the slum next door? Or is knowledge and awareness the first step towards understanding?

For more information on slum tourism, these resources may help:

- Slum Dwellers International is a is a network of community-based organizations of the urban poor in 33 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

- Slumtourism.net brings together academics and practitioners working on tourism in slums and poor rural areas.

- The world’s five largest slums .

Both For And Against Slum Tourism

By Zezinho Da Rocinha, Proud Favela Resident In Rio De Janeiro

I certainly understand the controversy about slum tours . I am both FOR and AGAINST them. Let me explain this.

I was born, grew up and still live in Brazil’s largest slum, or favela . Life is dificult yes, but not impossible. I am proud to live here in Rocinha. I will never leave here, I do not want to leave here. This is my home. This is my feeling about this issue of slum/favela tourism .

What I like about the tours is the contact I get from foreigns who come here. This interaction helps me to educate people about my life here in the favela. When foreigners come here I feel like my home or favela has value and is worth to be seen. The Brazilian government mostly ignores us and helps us very little. We want our voice to be heard . I want to feel that somebody on the outside cares about us and recognizes that we exist. Up until about a few years ago favelas did not exist on maps. Why was this?

Many foreigners come to learn how we create and live in our comunity with little or no goverment involvement. Others come because of the art and culture that exist here.

I do not judge why people come, they confirm that we exist.

I started in tourism because I saw the opportunity to show my favela and help create jobs for others here.

We live here, and should be making the tours here. I have heard outsider tour companies exaggerate things or tell outright lies about my favela. They do this because they do not know and do not live here. I am here to share a social experience, not provide some adrenalin tour.

With my work, many visitors return to volunteer with social projects or to start their own programs in the favela. Recently people have contacted me wanting to make projects like a rooftop garden class. Another person wants to help bring solar energy here. These are people who came on visits here in the favela. Is this bad? What I do NOT like about the tours …tours that use jeeps or trucks are the worst because they present us like a zoo. The tourists have no contact with the locals and this reinforces a sense of possible danger. Tours or visits where the guests walk in the favela are more welcome. There is one company that tells their guests not to interact with the locals if they are approached. This is wrong.

The glamorization of violence is another thing that we do not like here. It is as if these companies are trying to capitalize on some kind of excitement. Favelas are not war zones, and people need understand that real, honest hardworking people live there, we just make less money. There are tour companies here who use the community to make money but they give very little or nothing back to the community. This is not right. They should contribute something for the betterment of the favela. There are plenty of social projects here that could use help. I am not ashamed to live in the favela and people should not feel shame to come and visit. All we ask is please do not take photos of us like we are animals, and do not have fear if we say hello to you on the street. If we want to stop or reduce poverty, we need to stop pretending it does not exist. I call it socially responsible tourism. If you chose to tour this type of community, try to give something back, however big or small. I work with an art school and encourage people to bring art supplies, not money. Slums, favelas and shanties are where 1/3 of the population live in all major cities, serving the needs of mostly the rich. Visiting these places may increase your knowledge and awareness at a much deeper level than visiting a museum or art exhibition. Ignoring poverty is not going to make it go away and those who have more, should not feel guilt. Unfortunately, this world will always have this unbalance of wealth. Sad but true. Read more about Zezinho on his blog, Life in Rocinha or book a favela walking tour .

— Originally published on 06 February 2011

PIN THESE PICTURES AND SAVE FOR LATER!

If you liked this post, please share it!

Slumming it: how tourism is putting the world’s poorest places on the map

Lecturer in the Political Economy of Organisation, University of Leicester

Disclosure statement

From 2012-2014 Fabian Frenzel was a Marie-Curie Fellow and has received funding from the European Union to conduct his research on slum tourism.

University of Leicester provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Back in Victorian times, wealthier citizens could sometimes be found wandering among London’s poorer, informal neighbourhoods, distributing charity to the needy. “Slumming” – as it was called – was later dismissed as a morally dubious and voyeuristic pastime. Today, it’s making a comeback; wealthy Westerners are once more making forays into slums – and this time, they’re venturing right across the developing world.

According to estimates by tour operators and researchers , over one million tourists visited a township, favela or slum somewhere in the world in 2014. Most of these visits were made as part of three or four-hour tours in the hotspots of global slum tourism; major cities and towns in Johannesburg, Rio de Janeiro and Mumbai.

There is reason to think that slum tourism is even more common than these numbers suggest. Consider the thousands of international volunteers, who spend anything from a few days to several months in different slums across the world.

The gap year has become a rite of passage for young adults between school and university and, in the UK, volunteering and travel opportunities are often brokered by commercial tourism operators. In Germany and the US, state sponsored programs exist to funnel young people into volunteering jobs abroad.

International volunteering is no longer restricted to young people at specific points in their lives. Volunteers today are recruited across a wide range of age groups . Other travellers can be considered slum-tourists: from international activists seeking cross-class encounters to advance global justice, to students and researchers of slums and urban development conducting fieldwork in poor neighbourhoods.

Much modern tourism leads richer people to encounter relatively poorer people and places. But in the diverse practices of slum tourism, this is an intentional and explicit goal: poverty becomes the attraction – it is the reason to go.

Many people will instinctively think that this kind of travel is morally problematic, if not downright wrong. But is it really any better to travel to a country such as India and ignore its huge inequalities?

Mapping inequality

It goes without saying that ours is a world of deep and rigid inequalities. Despite some progress in the battles against absolute poverty, inequality is on the rise globally . Few people will openly disagree that something needs to be done about this – but the question is how? Slum tourism should be read as an attempt to address this question. So, rather than dismissing it outright, we should hold this kind of tourism to account and ask; does it help to reduce global inequality?

My investigation into slum tourism provided some surprising answers to this question. We tend to think of tourism primarily as an economic transaction. But slum tourism actually does very little to directly channel money into slums: this is because the overall numbers of slum tourists and the amount of money they end up spending when visiting slums is insignificant compared with with the resources needed to address global inequality.

But in terms of symbolic value, even small numbers of slum tourists can sometimes significantly alter the dominant perceptions of a place. In Mumbai, 20,000 tourists annually visit the informal neighbourhood of Dharavi , which was featured in Slumdog Millionaire. Visitor numbers there now rival Elephanta Island in Mumbai – a world heritage site.

Likewise, in Johannesburg, most locals consider the inner-city neighbourhood of Hillbrow to be off limits. But tourists rate walking tours of the area so highly that the neighbourhood now features as one of the top attractions of the city on platforms such as Trip Advisor . Tourists’ interest in Rio’s favelas has put them on the map; before, they used to be hidden by city authorities and local elites .

Raising visibility

Despite the global anti-poverty rhetoric, it is clear that today’s widespread poverty does benefit some people. From their perspective, the best way of dealing with poverty is to make it invisible. Invisibility means that residents of poor neighbourhoods find it difficult to make political claims for decent housing, urban infrastructure and welfare. They are available as cheap labour, but deprived of full social and political rights.

Slum tourism has the power to increase the visibility of poor neighbourhoods, which can in turn give residents more social and political recognition. Visibility can’t fix everything, of course. It can be highly selective and misleading, dark and voyeuristic or overly positive while glossing over real problems. This isn’t just true of slum tourism; it can also be seen in the domain of “virtual slumming” – the consumption of images, films and books about slums.

Yet slum tourism has a key advantage over “virtual slumming”: it can actually bring people together. If we want tourism to address global inequality, we should look for where it enables cross-class encounters; where it encourages tourists to support local struggles for recognition and build the connections that can help form global grassroots movements. To live up to this potential, we need to reconsider what is meant by tourism, and rethink what it means to be tourists.

- Volunteering

- Voluntourism

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Inside the Very Real World of 'Slum Tourism'

By Mark Ellwood

Hurricane Katrina left physical and emotional scars on New Orleans, and America, but nowhere was its impact more devastating than the city’s Lower Ninth Ward. Three years after the storm, in October 2008, the district was still pockmarked with half-demolished homes and patches of overgrown grass. It was also dotted with artworks, site-specific installations by the likes of Wangechi Mutu and her Ms Sarah House . Those works formed part of the city’s inaugural art biennial, Prospect New Orleans , bringing tourists to drive and wander through the area in droves. But visitors were caught in an uncomfortable paradox, their art viewing underpinned by the backdrop of one of America’s poorest neighborhoods—or what was left of it.

Locals stood by as various VIPs peered at Mutu’s work. When one of the arterati mustered up courage enough to ask if she minded the influx of gawkers, she shrugged and dodged the question. “It’s nice to have the art here, because it means people are coming to see more than just our ruined homes.” Not everyone reacted to the incomers with such neutrality, though—take one hand-painted sign erected in the neighborhood post-Katrina, that read:

TOURIST Shame On You Driving BY without stopping Paying to see my pain 1,600+ DIED HERE

Both reactions are understandable, and spotlight the uneasy distinction locals in the area might have drawn between being viewed rather than feeling seen. Is it wrong, though, to go beyond the sightseeing mainstays of somewhere like the French Quarter and into a corner of the city that might be blighted or underprivileged as these visitors did? It’s an awkward, but intriguing, question, and one that underpins a nascent niche in travel. It has been nicknamed ‘slum tourism,’ though it’s a broad umbrella term travel that involves visiting underprivileged areas in well-trafficked destinations. Such experiences are complex, since they can seem simultaneously important (bringing much-needed revenues, educating visitors first hand) and inappropriate (a gesture of misunderstanding fitting for a modern-day Marie Antoinette).

Indeed, even those who operate in the field seem to struggle to reconcile those divergent urges. Researching this story, there was resistance, suspicion, and even outright hostility from seasoned slum tourism vets. Deepa Krishnan runs Mumbai Magic , which specializes in tours around the city, home to what’s estimated as Asia’s largest slum; here, about a million people live in ad hoc homes a few miles from Bollywood’s glitz (it’s now best known as home to the hero of Slumdog Millionaire ). "The Spirit of Dharavi" tour takes in this settlement, a two-hour glimpse into everyday life aiming to show that the squalor for which it’s become shorthand is only part of Dharavi story. It’s also a hub of recycling, for example, and home to women’s co-op for papadum-making. Organized as a community project, rather than on a commercial basis, all profits are ploughed back into Dharavi. Yet pressed to talk by phone rather than email, Deepa balked. “I’ve been misquoted too often,” she said.

The organizer of another alt-tourism operation was even more reluctant, and asked not to be quoted, or included here, at all. Its superb premise—the formerly homeless act as guides to help visitors see and understand overlooked corners of a well-trafficked city—seemed smartly to upend tradition. Rather than isolating ‘the other,’ it shows the interconnectedness of so much in a modern city. The fact that both of these firms, whose businesses fall squarely into such non-traditional tours, are so squeamish about the topic is instructive—and reassuring for the rest of us when we’re conflicted about whether or not it’s ethical to treat deprivation as a distraction.

Call it poorism, misery tourism, poverty tourism—it still smacks of exploitation.

The contemporary concept of slum tourism dates back about 30 years, according to Ko Koens, Ph.D., a Dutch academic who specializes in this field and runs slumtourism.net . The South African government began bussing municipal workers into townships like Soweto in the 1980s, he explains, intending to educate them on no-go areas within their fiefdom. “International tourists, mostly activists, who wanted to show their support [for township-dwellers] started doing these tours, too. And after apartheid ended, the operators who were running them for the government realized they could do them commercially.” (It’s now a vital part of the country’s tourism economy, with some estimates that one in four visitors to the country book a Township Tour. )

Simultaneously, tourists were beginning to explore the slums or favelas of Rio de Janeiro. These are the shantytowns that six percent of Brazil’s population calls home. Bolted to the steep hills overlooking the waterfront mansions where wealthy Cariocas chose to live, these higgledy piggledy shacks perch precariously, as if jumbled in the aftermath of an earthquake. From here, the idea of slum tourism began spreading across the world, from Nairobi to the Dominican Republic, and of course, India. Mumbai Magic isn’t alone in operating tours of Bombay’s Dharavi slums—there are countless tours available of areas that now rival the Marine Drive or the Gateway of India as local attractions.

Yet though it’s a thriving new niche, many travelers remain squeamish about the idea. In part, of course, it’s thanks to the words "slum tourism," yet none of the alternatives seem any less confrontational. Call it poorism, misery tourism, poverty tourism—it still smacks of exploitation. There are also safety concerns, too: After all, Brazil supplied almost half the entries in a recent list of the world’s 50 most dangerous cities , not to mention that the world’s latest health crisis is headquartered in the stagnant waters on which the favela residents rely. The sense of being an interloper, or that such deprivation is Disneyfied into a showcase solely for visitors, is an additional factor—especially when spoofish ideas like Emoya’s Shanty Town hotel , a faux South African slum that offsets discomforts like outdoor toilets with underfloor heating and Wi-Fi, turn out not to be Saturday Night Live skits.

Muddled motivations add to the discomfort; one in-depth study found it was pure curiosity, rather than education, say, or self-actualization, that drove most visitors to book a trip around the Dharavi slums. One first-hand account by a Kenyan who went from the slums of Nairobi to studying at Wesleyan University underlines those awkward findings. “I was 16 when I first saw a slum tour. I was outside my 100-square-foot house washing dishes… “ he wrote. “Suddenly a white woman was taking my picture. I felt like a tiger in a cage. Before I could say anything, she had moved on.” He makes one rule of any such trips all too clear: If you undertake any such tours, focus on memories rather than Instagram posts.

Sarah Enelow-Snyder

Juliana Shallcross

Boutayna Chokrane

Sarah James

Suddenly a white woman was taking my picture. I felt like a tiger in a cage.

The biggest challenge, though, is the lack of accreditation. It's still a frustratingly opaque process, to gauge how profits made will directly improve conditions in that slum, admits Tony Carne, who runs Urban Adventures , a division of socially conscious firm Intrepid Travel. His firm is a moderated marketplace for independent guides—much like an Etsy for travel—and offers a wide range of slum tours around the world. Carne supports some form of regulation to help reassure would-be clients of a slum tour’s ethical credentials. “The entire integrity of our business is sitting on this being the right thing to do,” he says, though he also predicts a shift in the business, likely to make such regulation unnecessary. Many charities have begun suggesting these slum tours to donors keen to see how and where their money is used, outsourced versions of the visits long available to institutional donors. He is already in to co-brand slum tours with several major nonprofits, including Action Aid via its Safe Cities program; Carne hopes that such partnerships will reassure travelers queasy about such tours’ ethics and finances. “Everyone from the U.N. down has said poverty alleviation through tourism can only be a reality if someone does something,” he says. “It will not solve itself by committee. It will solve itself by action.”

Carne’s theory was echoed by my colleague Laura Dannen Redman, who visited the Philippi township in Cape Town under the aegis of a local nonprofit. It was a private tour, but the group hopes to increase awareness to bolster the settlement’s infrastructure. She still vividly recalls what she saw, half a year later. “The homes were corrugated iron, but tidy, exuding a sense of pride with clean curtains in the windows. But there was this one open gutter I can't forget. The water was tinged green, littered with what looked like weeks’ worth of garbage—plastic wrappers and bottles and other detritus. It backed the neighborhood like a gangrenous moat," she says. "They deserve better. It does feel disingenuous, shameful, even if you’re there to learn and want to help. But the end result was motivating. We did feel called to action, to pay more attention to the plight of so many South Africans.” In the end, perhaps, it isn’t what we call it, or even why we do it that matters—it’s whether the slum tourism experience inspires us to try to make a change.

The good, bad and ugly of slum tourism

Share story.

When Marie Antoinette wanted to escape the confines and pressures of courtly life, she retreated to her quaint Petit Hameau, a rustic retreat at Versailles, where she and her companions donned their finest peasant frocks and pretended to be poor.

A century later, fashionable Londoners took that pauper fantasy to a new extreme — nocturnally touring East London’s slums, where they gawked at ladies of the night and coined the phrase “slumming it.” The idiosyncratic pastime eventually made its way across the pond and, before long, New York City socialites were hitting the Bowery in search of opium dens and lowbrow adventure. Back then, slum tourism was sort of a DIY diversion.

Today, it’s an all-inclusive destination vacation. Twenty-first century slum tourism is a far cry from the back -alley excursions of yesteryear. For the right price, discerning travelers can experience firsthand how the poorest of the poor live — some times without ever having to sacrifice first-world conveniences like Wi-Fi, heated floors, and Jacuzzi tubs.

Here are details of some of our (least) favorite poverty-chic getaways, including what a vacation or tour will set you back, where to book — and just how tasteless these options are.

Most Read Life Stories

- Free-range kids are becoming a problem at the airport. What's the solution?

- The Rick Steves guide to life VIEW

- In-N-Out proposes second WA location in east Vancouver

- Owners selling vacation rentals from under guests is a growing problem

- Why a new organic produce shopping guide is helpful, not fearful

1.A 5-star South African shantytown

Bloemfontein, South Africa

Lodging from $82 per night

Tastelessness: Very High

Have you ever wanted to steal away to a cozy tin shack in one of South Africa’s sprawling shantytowns — only to change your mind over concerns about crime, noise and generally poor infrastructure? Emoya, a luxury hotel in Bloemfontein, may be just what you’re looking for: A quaint little shantytown tucked safely away on a game preserve. A mere $82 per night will get you a private shack, made of corrugated tin sheets, so you can experience the charm of living in a post-apartheid shantytown, without ever having to set foot in one. The shantys are child-friendly, and come equipped with heated floors, free Wi-Fi, and spa services.

2.Vacation like a border crosser, in Mexico

Parque EcoAlberto

Hidalgo, Mexico

Lodging from $105 per night;

“Night Walk” tour $19 per person.

Tastelessness: Moderate

In Southern Mexico, an eco-park owned by Hñahñu Indians offers tourists a chance to live out the drama and tension of an illegal border crossing. Called “Night Walk,” the strange excursion lasts about four hours and takes groups on an imaginary journey through the desert and across the Rio Grande. A dozen or so Hñahñus act out different roles: fellow migrants in search of work, as well as police on the lookout for border crossers. The park has many other attractions, too — including hot springs, kayaking and campgrounds — but the Night Walk seems to be the biggest draw.

In Indonesia, an authentic, bare-bones (and sometimes flooded) getaway

Banana Republic Village

Jakarta, Indonesia

Lodging $10 per night

Tastelessness: High

Travelers looking for a more realistic third-world experience may find it at “Banana Republic,” a plantation village just minutes outside of Jakarta. Ten dollars per night will get you a room, a mattress, and a fan within this interconnected complex of shanty homes. Bring your own flashlight if you expect to use the outdoor toilet at night, as well as your own toiletries for the communal shower.

If that’s not authentic enough for you, the Airbnb posting notes that “In December, the floods arrive. Heavy rain causes the river surrounding the village to overflow … The rusty roofs leak and leave the homes damp.” According to the ad, your $10 will go toward unclogging the river and repairing damaged roofs — but not before you get the chance to enjoy both.

4. Tour Rio’s largest favela with some of its very own residents

Favela Tourism Workshop

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

From $30 per person

Tastelessness: Moderate to Mild

A Brazilian company called Exotic Tours was the first to offer sightseeing tours of Rio de Janeiro’s biggest slum, Rocinha. In recent years, it began hiring local favela residents to work as guides, an effort that created a more authentic experience for travelers, and provided some income for members of the community. The company claims that some of the proceeds benefit a local school, so tourists can rest assured that they’re doing their part to help Rio’s urban poor. Be warned, though: Increasing tourism has helped to transform Rocinha from a sprawling shantytown into a semi-developed urban slum, so it’s perhaps less gritty than the average poverty tourist might prefer.

5.Enjoy San Francisco’s grittiest neighborhood alongside its homeless

San Francisco, Calif.

Tour is $20 per person.

Tastelessness: Relatively mild

Most visitors to San Francisco try to avoid the Tenderloin, a downtown neighborhood once notorious for its high crime rate but now better known for its population of vagrants. One man, Milton Aparicio, is trying to change that, by offering tours that highlight the Tenderloin’s unique culture of homeless. “We’ll go to a couple of shelters, day centers for children, soup kitchens, “ he advertises, offering “a guided experience of what it’s like to be homeless from a friendly homeless person.” Like most other examples of slum tourism, it promises an eye-opening experience that will certainly lead to personal growth and enlightenment.

In that respect, contemporary poverty tourism still resembles its 19th century predecessors. While the original London slumming parties were unabashedly voyeuristic and exploitative, they nevertheless revealed an upside: The parting of the veil between rich and poor moved some members of the upper classes to charitable action. “London slumming brought to the notice of the rich much suffering,” The New York Times reported in 1884, “and led to sanitary reforms.”

Modern day slumming, by contrast, is often characterized at the outset as a socially responsible endeavor — often purporting to benefit impoverished communities. That said, it’s still a little creepy to pay for the experience of watching poor people like animals in a zoo.

Catherine Traywick is a fellow at Foreign Policy magazine.

‘We are not wildlife’: Kibera residents slam poverty tourism

Tourism in Nairobi slum is rising but many residents are angry at becoming an attraction for wealthy foreign visitors.

Kibera, Kenya – Sylestine Awino rests on her faded brown couch, covering herself with a striped green shuka, a traditional Maasai fabric.

It’s exactly past noon in a noisy neighbourhood at the heart of Kibera, Kenya ‘s largest slum, and the 34-year-old has just finished her daily chores.

Keep reading

Dubai announces $35bn construction of world’s largest airport terminal, thousands protest against over-tourism in spain’s canary islands, how one mexican beach town saved itself from ‘death by tourism’, photos: tourist numbers up in post-war afghanistan.

Directly opposite Awino, her two daughters are busy studying for an upcoming math exam.

The family will not have lunch today.

“We don’t afford the luxury of having two consecutive meals,” says Awino, a mother of three. “We took breakfast, meaning we will skip lunch and see if we can afford dinner”.

Up until five years ago, Awino made a living selling fresh food in Mombasa, Kenya’s second largest city. There, she interacted with tourists who came to enjoy the sandy beaches of the Indian Ocean.

But in 2013, she decided to move to Kibera, in the capital, Nairobi, aiming for new opportunities – only to meet camera-toting tourists again, this time eager to explore the crowded slum where many are unable to afford basic needs.

“This was strange. I used to see families from Europe and the United States flying to Mombasa to enjoy our oceans and beaches,” says Awino, who is now a housewife – her husband, a truck driver, provides for the family.

“Seeing the same tourists manoeuvring this dusty neighbourhood to see how we survive was shocking,” she adds.

Awino recalls one incident a few months ago when a group of tourists approached her, with one of them trying to take a picture of her.

“I felt like an object,” she says. “I wanted to yell at them, but I was afraid of the tour guides accompanying them”.

![why slum tourism is bad Some residents say tourism in Kibera is morally wrong, while others are taking advantage of the trend by becoming tour guides [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/e88ee18754d04805ba51645d62295887_18.jpeg)

Kibera has seen a sudden rise of tourists over the past decade, with a number of companies offering guided tours showcasing how its residents live.

The slum faces high unemployment and poor sanitation, making living conditions dire for its residents.

According to Kenya’s 2009 census, Kibera is home to about 170,000 people. Other sources, however, estimate its population to be up to two million people.

Because of the high population, housing is inadequate. Many residents are living in tiny, 12ft by 12ft shack rooms, built in some cases with mud walls, a ridged roof and dirt floor. The small structures house up to eight people, with many sleeping on the floor.

Last week, thousands of families were left homeless after the government demolished homes, schools and churches to pave way for a road expansion.

Strolling through the dusty pathways sandwiched by the thin iron-sheet-walled houses, Musa Hussein is angry to see the growing popularity of the guided tours.

“Kibera is not a national park and we are not wildlife,” says the 67-year-old, who was born and raised here.

“The only reason why these tours exist is because [a] few people are making money out of it,” he adds.

The trade of showing a handful of wealthy people how the poor are living, Hussein argues, is morally wrong and tour companies should stop offering this service.

‘We created employment for ourselves’

Kibera Tours is one of the several companies that have been set up to meet the demand.

Established in 2008, the company has between 100 to 150 customers annually. Each client is charged around $30 for a three-hour tour, according to Frederick Otieno, the cofounder of Kibera Tours.

“The idea behind it was to simply show the positive side of Kibera and promote unique projects around the slums,” he says. “By doing this, we created employment for ourselves and the youth around us”.

The tour company employs 15 youths, working in shifts.

Willis Ouma is one of them.

Midmorning on a cloudy Saturday, the 21-year-old is wearing a bright red shirt. Accompanied by a colleague, he stands at one of the slum’s entrances, anxiously waiting to greet a group of four Danish tourists who have registered for the day’s tour.

“I have to impress them because tourists recommend to each other,” he says.

For three years, Ouma has been spending most of his weekends acting as a tour guide for hundreds of visitors.

“They enjoy seeing this place, which makes me want to do more. But some locals do not like it all,” he says, adding that he often has to calm down protesting residents.

Ouma earns $4 for every tour.

“This is my side hustle because it generates some extra cash for my survival,” he says. “I used my earnings to start a business of hawking boiled eggs”.

What would happen to an African like me in Europe or America, touring and taking photos of their poor citizens? by Sylestine Awino, Kibera resident

One of the Danish tourists is 46-year-old Lotte Rasmussen, a Nairobi resident who has toured Kibera more than 30 times, often with friends who visit from abroad.

“I bring friends to see how people live here. The people might not have money like us, but they are happy and that’s why I keep on coming,” she says, carefully bending down to take an image of a smiling Kibera toddler.

The tour includes stops at sites where visitors can buy locally-made craftwork, including ornaments and traditional clothing.

“We support local initiatives like children’s homes and women’s groups hence I do not see a problem with ethical issues,” says Rasmussen.

But Awino remains adamant.

She maintains that it is morally unfair that tourists keep on coming to the place she calls home.

“Think of the vice versa,” she says, “What would happen to an African like me in Europe or America, touring and taking photos of their poor citizens?”

![why slum tourism is bad Sylestine Awino was shocked to see tourists visiting Kibera to see how the residents live [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/63ac4ca0760849c984b0deb85cc852c0_18.jpeg)

Wednesday, 1 May, 2024

Slum Tourism: an ethical choice? A complex dilemma

US travel rebound means $800 million for domestic cleaners

Will it be possible to keep our gym routines in the ‘new reality’?

Elisa Spampinato is a travel writer and a Community Storyteller who has lived and worked in Italy, Brazil, and the UK where she is currently located. Practitioner, researcher, speaker, and consultant for sustainable tourism with years of experience in local development and social projects, and a passionate advocate for ethical and responsible tourism. As a writer, she has collaborated with Tourism Concern , Equality in Tourism, Gender Responsible Tourism – GRT, Travindy and Tourism Watch . She has published a book on Slum Tourism in Rio de Janeiro and she continues telling the stories of tourism encounters in local communities, especially the traditional, rural and indigenous ones. Among other things, she is the Community-Based Tourism specialist and Ambassador for the Transformational Travel Council (TTC) Elisa can be followed on her Blog , Facebook , LinkedIN and Instagram .

Slums are complex realities that present hugely varying scenarios, even within the same city. In a similar way, the term ‘Slum Tourism’ does not refer to a homogeneous phenomenon. Therefore, the answers to our question can differ according to the specific context we are considering. Slum Tourism can be an ethical choice, and yet in some cases it is definitely not.

Although several decades have passed since its first global appearance in Brazil in the 1980s, Slum Tourism continues to be a very controversial phenomenon, while it registers an overall rise in demand. Data about this niche form of experiential tourism is intrinsically limited, although we know that the numbers of visitors are significant, and the favela of Rocinha alone receives an average of 50,000 tourists per year. Therefore, it is crucial – and I dare say even necessary – to understand the key factors determining the potentially positive and innovative impacts, nowadays recorded in an increasing number of cases, that follow a trend seemingly in contrast to the image of the early days, when the term ‘human zoos’ was coined.

It is known that the criticisms of this kind of tourism, where they exist, are fierce and poignant, and with good reason.

The most common accusations raised against Slum Tourism, in fact, are serious ones and are mainly linked to:

- exploitation of poverty,

- reinforcement of cultural stigma,

- disrespect of human privacy and, last but not least,

- commodification of social issues and marginalisation.

However, instances do not necessarily lead to such outcomes, and many grassroots examples prove that more nuances and possibilities need to be added to the picture.

Moreover, there is now a greater variety of actors involved, with motivations that go beyond simple financial interest, which opens space for the conscious design of ethical outcomes.

A closer look at the range of local experiences springing up in many locations, shows us that Slum Tourism can be a force for good and it can even provide long-lasting benefits that improve the local people’s quality of life.

Grassroots positive examples

In India , Reality Tours – founded in 2005, and inspired by the work done in some carioca slums – is active in Mumbai’s biggest slum Dharavi and in Delhi, and has started several educational programmes through its sister organisation Reality Gives , which since 2009 has invested in the future of the local youth by providing training and professional skill-building options. Slum Tourism here is an active tool used towards poverty reduction and social development.

In Brazil , probably due to their longer history, a traditionally more engaged third sector and a consistent level of governmental support during the Olympics in 2016, the slums are sometimes an incredible laboratory of social innovation, and are able to share many positive examples. The MUF – Museu de Favela , for example, an open-air museum that celebrates the history and cultural roots of the community with massive colourful graffiti on the residents’ houses; the Morrinho Project , a twenty-three year old social project that has invested in creativity and imagination as a weapon against the limiting of options open to the local youth; Rocinha Original Tour , the first Community-Based Agency formally created in a Brazilian slum, highly rated on Trip Advisor and with international visibility; Santa Marta collective is a group of twelve certified local tour guides from the same slum – active in local government discussions, it collaborates regularly with academic research centres to strengthen their unity and the rights of the sector and their own community.

Among the positive benefits registered in these and other cases we find the following:

- a rise in self-esteem in the local community members,

- deconstruction of cultural stigma traditionally associated with the favela ,

- a boost to the local economy and potential for sustainable development,

- social inclusion of marginalised segments of society and professional skills building,

- women and youth empowerment.

It seems obvious from these examples that a single narrative story appears to be limiting, partial, and dangerous overall, because it could leave in the shade, and even suppress, experiences that need more visibility to grow and to produce further fruits that are beneficial to the locals in the process.

You may be interested in reading

5 must-visit destinations for chocolate lovers

7 things to do in Santa Barbara

Brazil reintroduces visas for tourists from Australia, Canada and the US

5 places to visit during tulip season in the Netherlands

8 of the most beautiful UK forests

Belgium to open historic Westmalle Castle to public early in 2025

Keukenhof and its tulips are officially back this spring

How to take better travel photos with your smartphone

Slumtourism.net

Home of the slum tourism research network, virtual tourism in rio’s favelas, welcome to lockdown stories.

Lockdown Stories emerged as a response to the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic has impacted communities all around the world and has brought unprecedented challenges. In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro this included the loss of income and visibility from tourism on which community tourism and heritage projects depend. In that context, Lockdown Stories investigated how community tourism providers responded, and what support they needed to transform their projects in the new circumstances. In these times of isolation, Lockdown Stores aims to create new digital connections between communities across the world by sharing ‘Lockdown Stories’ through online virtual tours.

We are inviting you to engage in this new virtual tourism platform and to virtually visit six favelas in Rio de Janeiro: Cantagalo, Chapéu Mangueira, Babilônia, Providência, Rocinha and Santa Marta.

The tours are free but booking is required. All live tours are in Portuguese with English translation provided.

Tours happen through November and December, every Tuesday at 7 pm (UK) / 4 pm (Brazil) Please visit lockdownstories.travel where you can find out more about the project.

This research project is based on collaboration between the University of Leicester, the University of Rio de Janeiro and Bournemouth University and is funded by the University of Leicester QR Global Challenges with Research Fund (Research England).

Touristification Impossible

Call for Papers – Research Workshop

Touristification Impossible:

Tourism development, over-tourism and anti-tourism sentiments in context.

4 th and 5 th June 2019, Leicester UK

TAPAM – Tourism and Placemaking Research Unit – University of Leicester School of Business

Keynotes by Scott McCabe, Johannes Novy, Jillian Rickly and Julie Wilson

Touristification is a curious phenomenon, feared and desired in almost equal measure by policy makers, businesses and cultural producers, residents, social movements and last but not least, tourists themselves. Much current reflection on over-tourism, particularly urban tourism in Europe, where tourism is experienced as an impossible burden on residents and cities, repeats older debates: tourism can be a blessing or blight, it brings economic benefits but costs in almost all other areas. Anti-tourism social movements, residents and some tourists declare ‘touristification impossible’, asking tourists to stay away or pushing policy makers to use their powers to stop it. Such movements have become evident in the last 10 years in cities like Barcelona and Athens and there is a growing reaction against overtourism in several metropolitan cities internationally.

This workshop sets out to re-consider (the impossibility of) touristification. Frequently, it is understood simplistically as a process in which a place, city, region, landscape, heritage or experience becomes an object of tourist consumption. This, of course, assumes an implicit or explicit transformation of a resource into a commodity and carries an inherent notion of decline of value, from ‘authentic’ in its original state to ‘commodified’ after touristification. In other words, touristification is often seen as a process of ‘selling out’. But a change of perspective reveals the complexities involved. While some may hope to make touristification possible, it is sometimes actually very difficult and seemingly impossible: When places are unattractive, repulsive, controversial, difficult and contested, how do they become tourist attractions? Arguably in such cases value is added rather than lost in the process of touristification. These situations require a rethink not just of the meaning of touristification, but the underlying processes in which it occurs. How do places become touristically attractive, how is attractiveness maintained and how is it lost? Which actors initiate, guide and manipulate the process of touristification and what resources are mobilised?

The aim of this two-day workshop is to provide an opportunity to challenge the simplistic and biased understanding of tourism as a force of good and touristification as desirable, so common among destination marketing consulting and mainstream scholarly literature. But it will equally question a simplistic but frequent criticism of touristification as ‘sell-out’ and ‘loss of authenticity’.

We invite scholars, researchers, practitioners and PhD students to submit conceptual and/or empirical work on this important theme. We welcome submissions around all aspects and manifestations of touristification (social, economic, spatial, environmental etc.) and, particularly, explorations of anti-tourism protests and the effects of over-tourism. The workshop is open to all theoretical and methodological approaches. We are delighted to confirm keynote presentations by Scott McCabe, Jillian Rickly, Johannes Novy and Julie Wilson.

The workshop is organised by the Tourism and Placemaking Research Unit (TAPAM) of the School of Business and builds on our first research workshop last year on ‘Troubled Attractions’, which brought together over 30 academics from the UK and beyond.

The workshop format

The research workshop will take place in the University of Leicester School of Business. It will combine invited presentations by established experts with panel discussions and research papers. Participants will have the chance to network and socialize during a social event in the evening of Tuesday 4 th June. There is small fee of £20 for participation. Registration includes workshop materials; lunch on 4 th and 5 th June 2019 and social event on 4 th June.

Guidelines for submissions

We invite submissions of abstracts (about 500 words) by 31 st April 2019 . Abstracts should be sent by email to: Fatos Ozkan Erciyas ( foe2 (at) le.ac.uk ).

Digital Technology, Tourism and Geographies of Inequality at AAG April 2019 in DC

Digital technology, tourism and geographies of inequality.

Tourism is undergoing major changes in the advent of social media networks and other forms of digital technology. This has affected a number of tourism related processes including marketing, destination making, travel experiences and visitor feedback but also various tourism subsectors, like hospitality, transportation and tour operators. Largely overlooked, however, are the effects of these changes on questions concerning inequality. Therefore, the aim of this session is to chart this relatively unexplored territory concerning the influence of technologically enhanced travel and tourism on development and inequality.

In the wake of the digital revolution and its emerging possibilities, early debates in tourism studies have been dominated by a belief that new technologies are able to overcome or at least reduce inequality. These technologies, arguably, have emancipatory potential, inter alia, by increasing the visibility of neglected groups, neighborhoods or areas, by lowering barriers of entry into tourism service provision for low-income groups or by democratizing the designation what is considered valuable heritage. They also, however, may have homogenizing effects, for example by subjecting formerly excluded spaces to global regimes of real estate speculation or by undermining existing labour market regimes and standards in the transport and hospitality industries. These latter effects have played a part in triggering anti-tourism protests in a range of cities across the world.

In this session we aim, specifically, to interrogate these phenomena along two vectors: mobility and inequality.

Sponsor Groups : Recreation, Tourism, and Sport Specialty Group, Digital Geographies Specialty Group, Media and Communication Geography Specialty Group Day: 03.04.2019 Start / End Time: 12:40 / 16:15 Room: Calvert Room, Omni, Lobby Level

All abstracts here:

New Paper: Tourist agency as valorisation: Making Dharavi into a tourist attraction

The full paper is available for free download until mid September 2017

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016073831730110X

Tourist agency is an area of renewed interest in tourism studies. Reflecting on existing scholarship the paper identifies, develops and critically examines three main approaches to tourism agency, namely the Service-dominant logic, the performative turn, and tourist valorisation. Tourist valorisation is proposed as a useful approach to theorise the role of tourists in the making of destinations and more broadly to conceptualise the intentions, modalities and outcomes of tourist agency. The paper contributes to the structuring of current scholarship on tourist agency. Empirically it addresses a knowledge gap concerning the role of tourists in the development of Dharavi, Mumbai into a tourist destination.

Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism

Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism: Current perspectives on urban tourism (Berlin 11/12 May 2017) conference program announced / call for registration

Tourism and other forms of mobility have a stronger influence on the urban everyday life than ever before. Current debates indicate that this development inevitably entails conflicts between the various city users. The diverse discussions basically evolve around the intermingling of two categories traditionally treated as opposing in scientific research: ‘the everyday’ and ‘tourism’. The international conference Touristified everyday life – mundane tourism: Current perspectives on urban tourism addresses the complex and changing entanglement of the city, the everyday and tourism. It is organized by the Urban Research Group ‘New Urban Tourism’ and will be held at the Georg Simmel-Center for Metropolitan Studies in Berlin. May 11, 2017, 4:15 – 5:00pm KEYNOTE – Prof. Dr. Jonas Larsen (Roskilde University): ‚Tourism and the Everyday Practices‘ (KOSMOS-dialog series, admission is free).

May 12, 2017, 9:00am – 6:00pm PANELS – The Extraordinary Mundane, Encounters & Contact Zones, Urban (Tourism) Development (registration required).

See full conference program HERE (pdf)

REGISTRATION

If you are interested in the panels you need to register. An attendance fee of 40 € will be charged to cover the expenses for the event. For students, trainees, unemployed, and the handicapped there is a reduced fee of 20 €.

For registration please fill out the registration form (pdf) and send it back until April 20, 2017 to:

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Georg-Simmel-Zentrum für Metropolenforschung Urban Research Group ’New Urban Tourism’ Natalie Stors & Christoph Sommer Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin You can also send us the form by email.

https://newurbantourism.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/conference-program.pdf

AAG Boston Programm

The slum tourism network presents two sessions at the Association of American Geographer Annual Meeting in Boston on Friday 7 April 2017 :

3230 The complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism

is scheduled on Friday, 4/7/2017, from 10:00 AM – 11:40 AM in Room 310, Hynes, Third Level

3419 The complex geographies of inequality in contemporary slum tourism

is scheduled on Friday, 4/7/2017, from 1:20 PM – 3:00 PM in Room 210, Hynes, Second Level

Stigma to Brand Conference Programme announced

From Stigma to Brand: Commodifying and Aestheticizing Urban Poverty and Violence

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, February 16-18, 2017

The preliminary programme has now been published and can be downloaded here .

For attendance, please register at stigma2brand (at) ethnologie.lmu.d e

Posters presenting on-going research projects related to the conference theme are welcome.

Prof. Dr. Eveline Dürr (LMU Munich, Germany) Prof. Dr. Rivke Jaffe (University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Prof. Dr. Gareth Jones (London School of Economics and Politics, UK)

This conference investigates the motives, processes and effects of the commodification and global representation of urban poverty and violence. Cities have often hidden from view those urban areas and populations stigmatized as poor, dirty and dangerous. However, a growing range of actors actively seek to highlight the existence and appeal of “ghettos”, “slums” and “no-go areas”, in attempts to attract visitors, investors, cultural producers, media and civil society organisations. In cities across the world, processes of place-making and place-marketing increasingly resignify urban poverty and violence to indicate authenticity and creativity. From “slum tourism” to “favela chic” parties and “ghetto fabulous” fashion, these economic and representational practices often approach urban deprivation as a viable brand rather than a mark of shame.

The conference explores how urban misery is transformed into a consumable product. It seeks to understand how the commodification and aestheticization of violent, impoverished urban spaces and their residents affects urban imaginaries, the built environment, local economies and social relations.

What are the consequences for cities and their residents when poverty and violence are turned into fashionable consumer experiences? How is urban space transformed by these processes and how are social relationships reconfigured in these encounters? Who actually benefits when social inequality becomes part of the city’s spatial perception and place promotion? We welcome papers from a range of disciplinary perspectives including anthropology, geography, sociology, and urban studies.

Key note speakers:

- Lisa Ann Richey (Roskilde University)

- Kevin Fox Gotham (Tulane University)

Touring Katutura – New Publication on township tourism in Namibia

A new study on township tourism in Namibia has been published by a team of researchers from Osnabrück University including Malte Steinbrink, Michael Buning, Martin Legant, Berenike Schauwinhold and Tore Süßenguth.

Guided sightseeing tours of the former township of Katutura have been offered in Windhoek since the mid-1990s. City tourism in the Namibian capital had thus become, at quite an early point in time, part of the trend towards utilising poor urban areas for purposes of tourism – a trend that set in at the beginning of the same decade. Frequently referred to as “slum tourism” or “poverty tourism”, the phenomenon of guided tours around places of poverty has not only been causing some media sensation and much public outrage since its emergence; in the past few years, it has developed into a vital field of scientific research, too. “Global Slumming” provides the grounds for a rethinking of the relationship between poverty and tourism in world society. This book is the outcome of a study project of the Institute of Geography at the School of Cultural Studies and Social Science of the University of Osnabrueck, Germany. It represents the first empirical case study on township tourism in Namibia.

It focuses on four aspects: 1. Emergence, development and (market) structure of township tourism in Windhoek 2. Expectations/imaginations, representations as well as perceptions of the township and its inhabitants from the tourist’s perspective 3. Perception and assessment of township tourism from the residents’ perspective 4. Local economic effects and the poverty-alleviating impact of township tourism The aim is to make an empirical contribution to the discussion around the tourism-poverty nexus and to an understanding of the global phenomenon of urban poverty tourism.

Free download of the study from here:

https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/9591